Shipshape

HAVEN

HAVEN

HAVEN

HAVEN

Haven Harbour Yacht Services employs 30 in-house specialists at two leading Chesapeake Bay locations. Our unrivaled expertise will transform your vessel's preseason list from to-do, to done. Learn more at HAVENHARBOUR.COM.

Coordination is key to reaching their shared goal MacDuff Perkins

The Bay’s oldest and largest wooden boat gets the love she needs— Jefferson Holland

Winter is a great time to cozy up at a waterfront inn Susan Moynihan

It’s a new era for Chesapeake Bay Magazine Jefferson Holland

A Baltimore sailor plots a solo roundthe-world sprint— MacDuff Perkins

Fishboat meets dayboat in the Boston Whaler 360 Outrage— Capt. John Page Williams

O’Brien’s Oyster Bar & Seafood Tavern has tasty surprises in store— Krista Pfunder

The watershed’s rivers tell a story as old as time Capt. John Page Williams

1 Havre de Grace, Md., p. 35

2 Chesapeake City, Md., p. 42

3 Baltimore, Md., p. 6 & 26

4 Elk Ridge, Md., p. 35

5 Annapolis, Md., p. 18

6 Georgetown, D.C., p. 35

7 Washington, D.C., p. 42

8 Stevensville, Md., p. 42

9 Skipton Creek, Md., p. 40

10 Fredericksburg, Va., p. 35

11 Ridge, Md. p. 52

12 Richmond, Va. p. 35 13 Port Waywood, Va., p. 42

You’ve passed by Marine Mart a thousand times Angus Phillips

Hush Puppies & Crab Balls with Remoulade Sauce from POV Restaurant, Ridge, Md— Susan Moynihan

Valentine Dog— Jefferson Holland

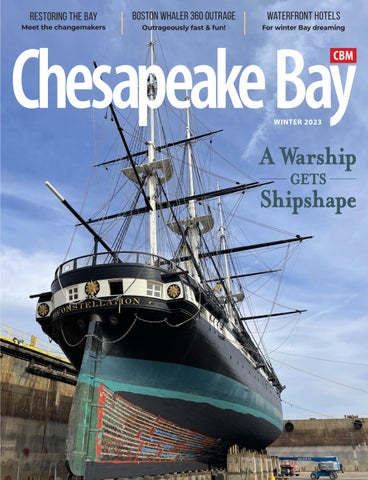

COVER

USS Constellation in drydock at Sparrow’s Point near Baltimore this past December (see p. 26).

Photo: Jefferson Holland

ABOVE

A photographer’s homage to the joys of winter frostbite racing.

Photo: Mark Hergan

PUBLISHER John Stefancik

EDITOR

Jefferson Holland

CRUISING EDITOR: Jody Argo Schroath

MULTIMEDIA JOURNALIST: Cheryl Costello

CONTRIBUTING EDITOR: Susan Moynihan

EDITORS-AT-LARGE: Ann Levelle, John Page Williams

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: Rafael Alvarez, Ann Eichenmuller, Robert Gustafson, Mark Hendricks, Marty LeGrand, Kate Livie, MacDuff Perkins, Angus Phillips, Nancy Taylor Robson, Charlie Youngmann

ART DIRECTOR Nancy Lambrides

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Meg Walburn Viviano

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS: Jim Burger, Dan Duffy, Jay Fleming, Mark Hendricks, Mark Hergan, Jill Jasuta, Caroline J. Phillips

GENERAL MANAGER Krista Pfunder

ADVERTISING

ADVERTISING ACCOUNT EXECUTIVE

Rick Marsalek • 410-627-8350 rick@ChesapeakeBayMagazine.com

PUBLISHER EMERITUS

Richard J. Royer

CIRCULATION

Theresa Sise • 410-263-2662 office@ChesapeakeBayMagazine.com

CHESAPEAKE BAY MEDIA, LLC

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER, John Martino EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, Tara Davis 410 Severn Avenue, Suite 314, Annapolis, MD 21403 410-263-2662

ChesapeakeBayMagazine.com

EDITORIAL: editor@ChesapeakeBayMagazine.com

CIRCULATION: circ@ChesapeakeBayMagazine.com

BILLING: billing@ChesapeakeBayMagazine.com

by Jefferson Holland

by Jefferson Holland

For more than 50 years now, this magazine has been devoted to bringing our readers insight into how to best appreciate life on one of America’s most treasured resources. We’ve enlisted the best writers, illustrators and photographers to introduce you to our unique historical, cultural and natural wonders that form our ethos and define our collective character—who we are and why we’re here.

In this coming year, you’ll find our devotion to presenting the people, places and perspective that celebrate living, working and playing on this Bay has redoubled. This year, our talented team at Chesapeake Bay Media will be doubling its digital content, providing news updates and exciting Bay happenings twice each week.

In addition to our wildly popular Bay Bulletin that is delivered every Wednesday, we will be adding a second weekly email featuring the best of the Chesapeake Bay lifestyle. It’s content Chesapeake-minded readers care about: Bay Boating, Bay Living, Bay Places and Bay People. Think destinations, boat and gear reviews, D.I.Y. how-tos from our experts, curated events and a spotlight on the people who make up the heart of the Chesapeake.

Meanwhile, Chesapeake Bay Magazine will continue to produce articles of timeless quality in print, just as readers have come to expect over the past half-century. Each of our six editions will be overflowing with great writing and illustrated with stunning visuals. These bimonthly issues will be real keepers. We’ll reimagine our popular “Weekends on the Water” edition in time to plan your excursions, as well as offer a special boating edition to augment the fall boat shows. We’ll be publishing an anticipated new edition of our Guide to Cruising the Chesapeake Bay, complete with constantly updated info online.

In CBM ’s new era, you’ll still get the timeless stories to browse through at your leisure in the tried-and-true traditional print medium, and on top of that, you’ll also get timely updates delivered straight to your smartphone. Fewer pieces of paper; far more useful and entertaining information.

In the Winter 2023 edition you’re about to read, you’ll meet five dynamic women who are leading some of the most important organizations intent on restoring the health of

the Chesapeake Bay (page 18). We’ll introduce you to young Black men who are earning their freedom from incarceration by learning the trade of caulking the seams of the hull of an ancient tall ship, the same trade that Frederick Douglass plied in the shipyards of Fells Point before escaping to freedom from slavery (page 26). You’ll meet a groundbreaking sailor who’s preparing to beat the speed record for a solo circumnavigation on a trimaran. He only has to sail an average of 17 knots to make it (page 6).

Our naturalist guru John Page Williams takes us on a tour of the Chesapeake’s fall line starting on page 35, then switches hats and gives a glowing review of Boston Whaler’s new 360 Outrage on page 10. While your boat may be under wraps for the winter, Contributing Editor Susan Moynihan notes that you can still get your nautical fix by enjoying a stay at one of the Bay’s choice waterfront hotels, while enjoying off-season rates. And you’ve passed this one place a thousand times driving to Ocean City, but Angus Phillips took the time to stop at the Marine Mart on Skipton Creek. You’ll be delighted at what he discovered. Oh, and you’ll get a little Valentine’s Day message at the end that I hope will warm your cockles.

I’m a storyteller at heart, and as such, I’m delighted to be part of this dynamic team that provides you with engaging, entertaining and fun stories for you to treasure. Be sure to tap into the dynamic resource that the new Chesapeake Bay Media provides, and thanks for being a loyal reader of CBM.

by MacDuff Perkins

by MacDuff Perkins

The first recorded circumnavigation of the globe was completed in 1522 by Ferdinand Magellan. The fleet, which sailed under the Spanish flag, originally consisted of five ships and roughly 270 sailors. The journey took three years, in which time four of the five ships sank and 90 percent of the sailors perished. Magellan himself was killed in battle in the Philippines.

In the centuries since, things have changed considerably. The circumnavigation record has slipped to just over 40 days, a feat performed by Frenchman Francis Joyon in 2017. Joyon sailed with a crew of five. That year another Frenchman, Francois Gabart, completed the goal in just over 42 days, and Gabart was solo for his journey.

Today, another sailor is gearing up to attempt his own record. Captain Donald Lawson is a professional sailor out of Baltimore, Md., with over 20 years of experience in both racing and passagemaking. When the Ocean Racing Multihull Association-class trimaran Groupama 2 became available, Lawson decided to get serious about the endeavor.

“We have a very fast boat,” Lawson says of the trimaran, which he renamed Defiant. “She does not need to be pushed. She is meant to take off right from anchor.” Most recently, Defiant acted as a training platform for the 33rd America’s Cup and set a record for the 2017 Transpac Race between California and Hawaii. She also holds the record for the Transat Jacque Vabre race, which covers the historical coffee trade route between Brazil and France. The boat will need to average 17 knots in order to beat this record.

No matter the season, Talbot County is the Eastern Shore’s culinary hotspot. Explore our coastal towns, fabulous restaurants, and elegant inns. Or bike, kayak, and sail the Chesapeake Bay.

4 tbsp. butter

1 large onion, finely diced

1 large Idaho potato, diced & blanched

1 stalk celery, diced & blanched

2 tbsp. ginger, peeled & micro-diced

4 oz. lemongrass, chopped

2 cloves garlic, micro-diced

½ tsp. Old Bay seasoning

1 tsp. salt

½ tsp. ground white pepper

2 c. whole milk

2 c. heavy cream

2 c. clam or oyster juice

1 tsp. parsley

1 tsp. lemon zest

½ tsp. ground mustard

1 tsp. Worcestershire sauce

16 oz. smoked oysters, undrained

Heat butter over medium heat in heavy bottom 3-quart saucepan. Add diced onion and sauté until tender, about 5 minutes. Add potato, celery, ginger and lemongrass, garlic, continue to sauté for another 1–2 minutes, being watchful to not burn garlic.

Add Old Bay, salt, white pepper, mustard and Worcestershire sauce. Reduce heat to low, add milk, cream and oyster liqueur.

Cook over low heat until mixture is hot and beginning to steam, and bubbles just start to appear around the edge. Do NOT allow to come to a boil. Salt and pepper to taste.

Add oysters and continue to cook over low heat until oysters begin to curl on edges. Finish with lemon zest and parsley.

The big difference between Defiant’s past record-breaking passages and the one Lawson is currently charting is that Lawson will be singlehanding the boat. But is he nervous about screaming around the world on a boat that can cruise at 28 knots in high seas? Not particularly. “I look forward to having the chance to just go, do my thing,” he says. “When I’m by myself, I’m very calm. This is an

opportunity for me to show what I can do on the water.”

That Lawson is comfortable sailing by himself is an unfortunate consequence of his sailing background. As an African American man, he frequently did not see anyone who looked like him out on the water. “When I first started sailing, I didn’t have any sailing friends,” he says. “If I wanted to go sailing, I went by myself.”

Lawson found a community within Baltimore’s Downtown Sailing Center, which was more inclusive than many of the yacht clubs in the area. He received his captain’s license and started delivering boats as well as racing. “A lot of the sailing I did at an early age was focused on technical topics and passagemaking,” he says. “Those skills translated into making boats go fast, and far.”

Lawson and Defiant are currently in San Diego, Calif., where he is completing final training runs and learning the boat. Lawson’s wife, Tori, helms the boat on training runs so that Lawson can study polar angles and adjust rigging. They take notes and collect video footage from the runs, anticipating scenarios in the Southern Ocean when Lawson will be working alone.

“I’m not doing a fun cruise around the world,” he says about the endeavor. “I can’t stop and play tourist in fun countries. This is a sporting event, and no other sporting event pushes you this hard.”

Lawson’s chosen field is in fact so demanding that only five sailors have attempted a trimaran record. And Lawson will not only be the first African American to attempt it, but also the first American sailor. “There’s a lot of pressure and responsibility,” he says. “People look at you, see the boat you have, the records you’re going for, and the level of scrutiny is so intense.”

Lawson thrives under this pressure because he knows it means he’s doing something right. “My father once compared it to being in the military,” he says. “When you choose to be in the forefront, it means that you’ll be shot at first. When you’re in the lead, trying to do something that hasn’t been done yet, everyone comes at you first.”

A significant aspect of Lawson’s mission is to bring representation to the sport so that other sailors do not experience the same exclusion that he felt. As a chairperson on U.S. Sailing’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusivity committee, he works with the U.S. Sailing board of directors to implement change within the sport. U.S. Sailing is the national governing body for the sport of sailing. “When I started sailing, I didn’t see anyone who looked like me. I don’t have any role models,” he says. “My goal is to ensure that’s not the case when I retire.”

Lawson and Defiant will be returning to the Chesapeake in early spring of 2023 to gear up for the solo attempt in October. Defiant will be sailing along the Eastern Seaboard on a tour aimed at bringing awareness to diversity in sailing. Schools, businesses and organizations are encouraged to connect with Lawson about partnerships and educational opportunities before he sets off for his record attempt.

“This passage is a dream of mine,” he says. We have no doubt it will soon be a reality.

For more information, visit captaindonaldlawson.com.

Transom Deadrise: 23 degrees

Bridge Clearance: 9'11" (w/ radar, 15' w/ upper station)

Persons Cap: 14

For more information, visit bostonwhaler.com or one of the company’s three Chesapeake dealers: Chesapeake Whalertowne, Grasonville, Md., whalertowne.com; Chesapeake Boat Basin, Kilmarnock, Va., chesapeakeboatbasin.com; and Lynnhaven Marine, Virginia Beach, Va., lynnhavenmarine.com

600-hp Mercury Verado outboards with dual, contrarotating propellers and two-speed gearcases. The big engines sat on rigid, vibration-damping mounts, with only the gearcases rotating for steering.

These engines turn dual-mode 48V/12V alternators to feed Navico’s integrated, digital Fathom e-power auxiliary management system, including lithium-iron-phosphate batteries and an inverter (120V), allowing features that

would otherwise require a generator. The Fathom system drives digital steering and controls (including a joystick), air-conditioning for the cabin and helm, a Seakeeper gyro stabilizer, lighting and plumbing, a pressurized freshwater system (45 gallons, 6 hot), a refrigerator/freezer, an optional electric grill on the transom, a stereo system with satellite radio, a bow thruster and an anchor windlass. A monitoring system at the helm keeps track of everything through a

complex wiring harness based on a marinized version of the electronic cables that undergird our cars and trucks. It’s housed in twin Simrad electronic displays (16" or 19") connected to a GPS, detailed digital charts, a VHF radio with Automatic Identification System (AIS), highpower sonar with down-scan and 3D display, digital radar, thermal night vision and a theft deterrent system. Our test boat also included a full upper helm with steering, joystick,

controls and a single Simrad display. Optimum cruising speed for this boat/ engine combination is 30 knots with top speed over 50. With a fuel capacity of 415 gallons, cruising range at 30 knots is over 300 miles, assuming a 10% safety margin.

Our sea trial showed this highpowered, big water beast is civilized enough to excel at simpler angling challenges. Rick Boulay, Jr., of Chesapeake Whalertowne and I took our tester up to the Eastern Stonepile at the Bay Bridge off Annapolis and up the Severn River. Jigging for rockfish and big white perch at the former requires maneuvering carefully through the eddies formed by powerful currents and holding position to keep anglers’ lines vertical in that deep water. For that job, the 360 was a sweetheart, with the huge but silky-smooth Mercs idling quietly, shifting in and out of gear smoothly. She was even maneuverable enough to position for an angler in the bow to cast and swim a bucktail precisely along the underwater ledges of the

bridge pilings. Up in the Severn, she held perfectly over corners and patches of fish on the river’s restoration oyster reefs in 12–25' of water.

Yes, we throttled her up to run from place to place, and the 600 Verados are remarkable. They’re amazingly quiet and smooth, thanks to Mercury’s dedicated Noise/ Vibration/Harshness (NVH) engineering laboratory. The torque from the big-block V12 powerheads and the dual propellers comes on immediately, thanks to the low first gear in the two-speed transmission. As the boat accelerates, the transmission shifts imperceptibly to the higher gear, as smoothly as the best modern automotive transmissions. We’ll take it on faith that they’ll push this 20,000lb. rig over 50 knots, since we were happy cruising in the 3200–4000 rpm range (15–30 knots), where Mercury’s Active Trim system kept the hull cleanly on plane. The 360 Outrage clearly showed a wide range of efficient speeds that will allow her skipper to adjust to any sea conditions she should be out in.

Base price for the 360 Outrage with twin Mercury 600-hp, V12 Verado outboards is $700,956. Adding options mentioned in this review like the Seakeeper ($77,737), the upper station with controls and Simrad display ($56,657), the Fathom e-power auxiliary management system ($40,084), twin 19" Simrad displays and related sensors at the lower helm ($18,918), cockpit sunshades ($16,482), thermal night vision ($18,043), and smaller items like the bow table ($4,315) plus destination charge ($16,979) bring the price of a fully optioned new boat to around $990,000.

by Krista Pfunder

by Krista Pfunder

On a cold and rainy afternoon at the Chesapeake Bay Media offices in Eastport, I found publisher John Stefancik scrounging around in the kitchen looking for sustenance. I was in need myself, so we headed over the bridge to downtown Annapolis to O’Brien’s Oyster Bar and Seafood Tavern to grab lunch.

We were quickly seated and our server, Markia, greeted us and took our drink order. I was thrilled to see a Greg Norman wine on the menu—I’m a fan of their blends and cabernet sauvignon—and ordered a glass of the shiraz ($12). It was a great choice, featuring bright aromas, black cherry and cloves. John opted for a black and tan, a combo of Yuengling lager and Guinness stout ($7), which he was happy with.

We decided to split an order of oysters Rockefeller ($17.95) as an appetizer. I love oysters, but oysters Rockefeller is not at the top of my list of preparation choices. That changed

after thoroughly enjoying the version at O’Brien’s.

Broiled local oysters were topped with creamed spinach, Pernod, Parmesan cheese and hollandaise sauce. John and I agreed that it was the best version of oysters Rockefeller we’ve both tried. The best way to describe the dish is “crave-able.” The creamed spinach was good enough to be a side dish in its own right.

Markia was very knowledgeable about the menu and was able to answer all questions we had regarding ingredients, level of spiciness, etc. We both took note of the friendliness of the staff and how happy they all seemed to be part of the team at O’Brien’s, which made the afternoon that much more enjoyable.

Based on Markia’s recommendation, John chose the spicy Cajun seafood pasta ($31.95). Penne is tossed with shrimp and scallops in a spicy Cajun cream sauce. John has been spending a good amount of time

in New Orleans lately so he's been on a spice kick. He declared this a great dish, with the perfect level of spice. “The scallops are juicy; the pasta is cooked perfectly and there’s a hint of pepper—which I love,” he said.

I opted for the crabcake sandwich ($24.95). Jumbo lump crab is topped with lettuce and tomato and served on a toasted potato roll with fries. The crabcake was large and consisted of chunks of lump and very little filler— just enough to bind. It came with both tartar and cocktail sauce, but I used tartar. The potato roll was perfectly toasted and the fries were a goodsized portion.

We were too stuffed to try dessert, but we did decide to explore upstairs—we both realized that despite growing up in Annapolis, we’d never ventured to the second floor. We were surprised to discover a wine bar,

a banquet room and what used to be a cigar lounge, now used for fantasy league draft nights (email events@ obriensoysterbar.com if you’re interested in booking).

As we headed back out into the cold and rain, I glanced back at the bar and realized a perfect evening would be splitting oysters Rockefeller over wine with a date.

A few other things not to miss are 99-cent oyster nights Monday through Thursday 3 p.m. to 7 p.m. and all day Wednesdays; happy hour 2 p.m. to 7 p.m. Monday through Friday, and

O’Brien’s “Fast Lunch Specials”

Monday through Thursday from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Editor’s Note: Nearly 30 years into concerted efforts to restore the Bay, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) established a Clean Water Act provision in 2010 called the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load, which provides science-based, enforceable limits on the amount of pollution entering the Chesapeake in order to remove the Bay from the federal "dirty waters" list. The six states in the Bay watershed—Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York, Virginia, West Virginia and Delaware, along with the District of Columbia—agreed to develop individual plans and milestones to achieve those limits by 2025, which will lead to the "fishable, swimmable" waters promised by the Clean Water Act of 1972.

As the 40-year deadline for the Chesapeake Bay Agreement looms, it’s possible to be simultaneously frustrated with the past and optimistic for the future. While most of the Agreement’s own goals will not be met, improvements in sediment runoff, water quality and habitat recovery all show signs of changes being made in the right direction. Gone are the days of rampantly reeking rivers; instead, we look forward to more otter and dolphin sightings as the Bay rebounds. After all, if the goal is to make the Bay “fishable and swimmable,” we can look at the presence of otters and dolphins fishing and swimming in the Bay as affirmations.

Perhaps the one goal that has been successful is the establishment of specific organizations to address concerns identified in the

Agreement. The Chesapeake Bay is now one of the most studied bodies of water in the country, thanks to the work of organizations committed to longterm restoration efforts. And just as the Bay has changed over the last 40 years, so have the collective workings of these groups. The dialogue between policy makers, scientists, farmers and activists has reached a level of collective action unseen in the last 40 years.

The current leaders of some of the most effective restoration efforts happen to be women, several of whom were not even born when the Agreement was put into place. They are bringing expertise and a spirit of camaraderie that is giving new hope to the Bay restoration movement. We spoke to them about the personal experiences that make them so eager to usher in a new wave on the watershed.

This regional partnership was founded in 1983 to meet the goals of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement. The program’s Chesapeake Executive Council consists of the governors of the six watershed states (Maryland, Virginia, Delaware, West Virginia, Pennsylvania and New York), the mayor of the District of Columbia, the chair of the Chesapeake Bay Commission (Maryland Senator Sarah Elfreth) and the administrator from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (Kandis Boyd). The office is based in Annapolis, where their staff—comprised of employees from federal and state agencies, nonprofits and academia— works to achieve their vision: “an environmentally and economically sustainable Chesapeake Bay watershed with clean water, abundant life, conserved lands and access to the water, a vibrant cultural heritage, and a diversity of engaged stakeholders.”

Learn more and find ways to help their work at chesapeakebay.net.

Dr. Kandis Boyd joined the EPA in 2022 after a 30-year career with the National Science Foundation and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Her career path was not a foregone conclusion, however. As the first African American woman to receive an undergraduate degree in meteorology from Iowa State University, Dr. Boyd was ready to be a storm chaser for Midwestern television stations. But when a television producer told her she “didn’t fit the demographic” for her audience, she moved into a role where her work would be valued for its merit. She has a double masters degree in meteorology and water resources as well as a doctorate in public administration.

As a meteorologist, her scientific understanding of the impact of climate change brings science to the

Port Isobel Island. I jumped on a boat worked on projects such as the Choose

solve the challenges for wildlife, we’re actually solving them for people as well. We need to consider people and nature in the same space.”

Whether it’s moving mountain lions in California or focusing on farms in Pennsylvania, Falk is focused on engaging people rather than enforcing policy. “We have to meet people where they are,” she says. “When we work with farmers, we focus on what will benefit them directly. What benefits the health of the soil will benefit the health of the herd. And when those two things occur, we’ll see improvement in the health of a local river or stream. By looking to improve peoples’ lives, we can connect the dots all the way down to a clean Chesapeake Bay.”

To create this engagement, Falk commits herself to listening to voices other than her own. “Over the years, I watched phenomenal leaders who were collaborative and empowering,” she says. “I wanted to be that leader. I feel responsible for making space at the table within the CBF and the broader community, because I know that the more voices we bring to the table, the better the outcome for the Bay will be.”

The largest independent organization devoted to saving the Bay, CBF was founded in Annapolis in 1967. They bring a four-pronged approach to their mission: education, via working with schools; advocacy, by advising and being a watchdog on policy decisions at every level; restoration, through handson work rebuilding natural filters from oyster reefs to shorelines; and litigation, as relates to the Bay. (You may have heard about their recent big win, with the Maryland Court of Appeals vacating the Conowingo Dam license due to sidestepping water quality certification.) Learn more and find ways to help their work at cbf.org

The Chesapeake Bay Trust is a nonprofit, grant-making organization that works to source and distribute assets along three core goals: environmental education in K–12 schools, and hands-on restoration and community engagement via a diverse network of community groups and nonprofits. One of the highestprofile campaigns is the Bay Plate license plate program, where a $20 donation lets you show you support every time you drive your car. CB Trust also administers popular programs like the Chesapeake Conservation Corps, which gives young adults onsite training in conservation work, and the Maryland Outdoor and Recreation Clean Water Fund, tailored towards anglers and boaters. Their website has a great interactive map where you can see the projects they support, all around the Bay.

Learn more and find ways to help at cbtrust.org.

One of the biggest challenges in Bay cleanup efforts is funding. A 2014 report by CBF estimated the economic benefit of a healthy Bay could be within the range of $120–$130 billion annually across the states of New York, Delaware, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia. But to get there, Bay stewards would need roughly $5 billion annually.

“The things that we have to do cost a lot of money,” says Dr. Jana Davis of the Chesapeake Bay Trust. “The government will be a huge part of the solution, but most of the land in the watershed is privately owned. It’s important for us to look for what communities want to do, and then help them raise money.”

Davis is an ideal networker for this specific purpose. A marine ecologist by training, she approaches her work with a focus on the intersection

between science and policy. This eye for both sides of the problem is both helpful and challenging. “I often worry that people will lose patience before we can make a difference, or that we aren’t being as cost-effective as we can be.”

This creates an opportunity for Davis. The Trust works to provide grants for residents and organizations aimed at improving local communities, which will in turn positively impact the Bay. The projects are creative and innovative, and often surprising. “In 2021, we funded a project within Patapsco Valley State Park,” she says. “The group retrofitted some campsites to be accessible to disabled veterans, and I love that because it helped bring in people who need nature. If we don’t provide access to resources, we can’t expect people to want to protect them.”

One of the Trust’s bigger challenges is the fact that many of the communities who would benefit most are not applying for funding. “If there’s a particular population who isn’t applying to our grant program, we’ll sometimes look further into it,” she says. “Not everyone has a grant writer on staff, so we’ll use connector groups to identify who we’re missing from the story and help them put proposals together.”

The Trust’s greatest source of funding is the Bay plate, which sells for $20. The money from these license plates has provided more than $130 million to over 14,000 grant recipients since 1985. The Bay plate is one of the easiest ways to support restoration and bring awareness.

“People always ask, ‘What’s one thing we can do to make a difference?’ And we always say that planting native plants is a good one,” she says. “If you can’t plant anything, buy a license plate. We’ll invest that money in places where the work can happen.”

In 1971, a group of local business owners came together from various fields to address the declining state of the Bay and the lack of political willingness to address the problems. Their idea was to use their professional backgrounds to create a coordinated approach to restoration efforts. The Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay was formed, and Frances Flanagan was their leader.

Almost 50 years later, in 2017, another woman was chosen to helm the organization. Kate Fritz was a biologist and environmental scientist working as a riverkeeper at the time. She had experience monitoring watersheds and creating land use policies as well as higher degrees in environmental management and leadership in sustainability. She was passionate about hunting and fishing. She had also lived in five of the Bay’s jurisdictions and knew the Chesapeake like the back of her hand. She was the ideal leader for the Alliance’s next 50 years, and still holds the position today.

“I feel honored to follow in Frances’s footsteps,” she says. “Her leadership was unprecedented for the 1970s. Collaboration and inclusivity are values that she brought to the table, and I hope to extend that in my time as well.”

Fritz grew up in a military household and moved around often. These experiences have created the backbone of her leadership style.

“Moving around so much as a kid has led me to be a humanist,” she says.

“I’ve moved around a lot within my career, as well. I’ve worked in the private and public sectors, and now with an NGO. I tell people that I know ‘a little about a lot,’ and that general knowledge has helped me evolve flexibly. Now, I’m able to leverage that at the Alliance.”

Fritz needed that flexibility as the pandemic changed her workflow in early 2020. “When I started at the Alliance, my vision was focused on building an organization for the next 50 years. The pandemic brought a new world of work, however, with greater flexibility and work-life balance. We looked at our personnel and our practices with an eye for building those for the future.”

This cultural shift allowed Fritz’s Alliance to change the way they approached their work. They adapted schedules to prioritize families over work. They created space for personnel to feel appreciated and able to separate their work lives from their personal lives.

One other shift that occurred was the Alliance’s consideration of partnerships. When Fritz assumed her position, she held social justice as a priority for the organization. “Since 2017, we’ve been working internally to dismantle unjust systems that disproportionately impact racially diverse communities,” she says. Together with her Board of Directors, Fritz established a resolution to build a culture of diversity and inclusion within the workplace. Resources and trainings followed. Her work within the social justice space provided an example for other organizations to follow.

Starting in 2020, Kate began cultivating relationships with groups such as Bowie State students and Eco Latinos and put the Alliance’s support behind their efforts. “I’ve always intellectually known that representation matters,” Fritz says. “But when we’re asking students what kind of speakers they want, and they say, ‘We want a naturalist of color to lead this bird walk,’ I understand it on a much deeper level.”

The ACB is a multi-state, citizen-led alliance born in 1971 to bring together communities, companies and conservationists from all around the Chesapeake Bay watershed to make real change around the Bay. With offices in Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia and Washington D.C., the ACB focuses on collaborative efforts in the areas of forestry, agriculture, green infrastructure and sustainable stewardship of our natural resources.

Learn more and find ways to help their work at allianceforthebay.org

Despite her success at the Alliance and the ripple effect her work has created, Fritz fears that it’s not enough. “I ask myself, ‘how do we maintain the urgency to keep doing what we’ve been doing?’ How can we come together, work more efficiently, work more collectively? We can’t wait anymore. We can always leave the conversation with an ‘and.’ We might not know what that is yet, and it could be someone else’s ‘and.’ But it’s continuously building it up, not shutting it down.”

The Chesapeake Bay Commission was created in the early 1980s as a tri-state legislative assembly representing Maryland, Pennsylvania and Virginia, whose goal is to coordinate policy in the restoration of the Chesapeake Bay watershed. The Commission’s leadership covers a full spectrum of Bay issues, from managing living resources and conserving land to protecting water quality.

Learn more and find ways to help their work at chesbay.us

Sarah Elfreth, Maryland State Senator and Chair of the Chesapeake Bay Commission

Sarah Elfreth, Maryland State Senator and Chair of the Chesapeake Bay Commission

The Bay restoration movement has benefitted from elected officials who are dedicated to the cause. But this is often a challenging role to assume.

“People want to hear that we’re going to sue Pennsylvania, that we’re going to throw the book at them,” says Sarah Elfreth, who, in 2018 at age 30 became the youngest woman elected to the Maryland Senate. “In terms of

effective change, though, I’m not sure that’s going to create it.”

Elfreth is now embarking upon her second term as a Maryland State Senator, where she is an effective strategist and communicator between people, states and governmental bodies. One of her greatest roles is Chair of the Chesapeake Bay Commission, which is comprised of legislators representing Pennsylvania and Maryland.

“When I go to see my colleagues in Pennsylvania, we don’t talk about the health of the Bay. They don’t have Bay waterfront, so our issues are not as visceral or visual there as they are here.” Instead of pitching the importance of crabs to Pennsylvania farmers, Elfreth meets them where they are. There are more cows in Lancaster County than there are in the entire state of Maryland, and while Pennsylvania has the greatest stream density in the country, half of their streams are impaired. So she talks about farms and streams.

“We have 157 municipalities in Maryland,” she says. “But in Pennsylvania, there are 2,560. That’s more than 2,500 town councils, mayors who might be part time. Maybe they have engineers on staff in those towns, or a designated stormwater person. But all those towns are making land-use policy that affects what happens downstream. By providing technical assistance to farms and support to municipalities, we’ll have the most impact on water quality in Maryland.”

Elfreth knows that her middle way approach isn’t going to make her flashy as a politician. “It’s a long answer,” she says of her approach. “And that’s a death knell in politics,

where we’re supposed to have quick, 10-second answers. But we are seeing progress.”

That progress is challenging to quantify. Elfreth recognizes that within the last 40 years of the movement, the area has suffered the loss of forests and wetlands while its population has tripled. But time does have its benefits. “Our science is far superior to what it was back when the Bay movement began,” she says. “And we have more grassroots organizations operating on the ground. Almost every stream has a group advocating for it. For the first time, we’re sending money upstream to Pennsylvania and helping them pay for their efforts. And this seems to be working.”

The work of creating interstate policies and reaching across the aisle politically is an art form, and Elfreth considers this her creative process. “I can’t paint a picture or play the guitar, but my creative juices flow in legislating.”

This involves the consideration of nuance, which Elfreth not only understands but also teaches as an instructor of political science and public policy at Towson University. “My job is to get the smartest people in the room to talk (and sometimes fight) a problem out. You compromise to the point where everybody is a little happy and a little pissed off, and that’s when you know you have the best policy.”

As a young politician who is fighting to solve problems her generation did not create, Elfreth maintains an optimism not often seen among her peers. But she says that this is crucial for moving forward. “If people don’t feel optimistic about the future, they’ll vote for the people who feed into their worst fears,” she says. “And then we aren’t going to see progress at all.”

The Bay’s oldest and largest wooden boat gets the love she needs.

BY JEFFERSON HOLLAND

BY JEFFERSON HOLLAND

Driving over the Francis Scott Key Bridge across the Patapsco River, I could see the green knoll of Fort McHenry over my left shoulder with the skyscraper skyline of downtown Baltimore beyond. Over my right shoulder, I was surprised to be able to spot what I was looking for amid the industrial wasteland of Sparrow’s Point: the upright white masts and squared yards silhouetted against the angular arms of gigantic yellow rail cranes. If I could find my way across a maze of highway construction, railroad tracks, gatekeepers and abandoned warehouses, I would make it to the drydock where the USS Constellation was getting her bottom re-caulked.

You can view the Bay Bulletin video by scanning this QR code:

Above: The ship in 1859 in drydock at the Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston; engraving from Ballou's Pictorial done by Mr. Waud, a marine draughtsman and painter

PHOTOGRAPHY & VIDEOGRAPHY BY:

JEREMY MORRISON, ALEX JENNINGS, NICK GARDNER, AND MIKE WALLS OF HARBOR CRAFT FILMS, A BALTIMORE-BASED VIDEO PRODUCTION COMPANY.

Above: The ship in 1859 in drydock at the Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston; engraving from Ballou's Pictorial done by Mr. Waud, a marine draughtsman and painter

PHOTOGRAPHY & VIDEOGRAPHY BY:

JEREMY MORRISON, ALEX JENNINGS, NICK GARDNER, AND MIKE WALLS OF HARBOR CRAFT FILMS, A BALTIMORE-BASED VIDEO PRODUCTION COMPANY.

the drydock, while the black-and-white hull remained hidden. Perched on the rim, I looked down on the 168-year-old ship, her keel propped up on enormous blocks 30 some feet below. She is nearly 200 feet long from the rudder to the tip of the bowsprit, but sitting there in the corner of the vast

reminded me of a toy boat left behind in an empty bathtub.

I got there at noon on one bright, chilly day in early December. As I stood at the tippy-top of the set of metal stairs that cascaded down to the bottom, I saw three tiny figures coming out from under the hull. If the

professional caulkers—all internationally renowned for their work on tall ships and traditional vessels of all descriptions—who were hired to do the work the Constellation needed. They were heading off to pursue another ancient tradition for tradesmen of their ilk: lunch.

I climbed down the stairs and found Chris Rowsom on top of a scissor lift, using a trowel to patch a crack in the stem of the ship with a gray, gritty substance that looked just like Portland cement. Imagine my surprise when he informed me that it was Portland cement. “We’re taking care the ship’s watertight integrity,” he explained when he had lowered himself down to my level. Chris is the Executive Director of Historic Ships in Baltimore and Vice President of Living Classrooms Foundation, and the USS Constellation is his charge.

He explained that the ship had been taking on water for the past couple of years—sometimes up to 3,000 gallons per hour. (That’s the volume of nearly 200 kegs of beer. Every hour.) “A wooden ship like this, you should probably drydock every five years or so if nothing else just to make sure that everything is okay,” Rowsom said. The last time they did it was seven years ago. “In this case, we actually had some issues we needed to take care of, so that’s what we’re doing.”

And this isn’t just any old wooden ship; she’s a “sloop-of-war.” In this case, we’re not talking about a singlemasted boat like most modern recreational sailboats. In 17th and 18th century navies, a sloop-of-war was a designation for a fully-rigged ship— usually with three masts—with a single gun deck below the flush weather deck. The Constellation was built in the Gosport Shipyard in Portsmouth, Va., and launched in 1855. She was the last all-sail-powered

ship built by the U.S. Navy. Ships built later all had some form of auxiliary steam power.

The Constellation served on the African Squadron, capturing slave ships and freeing hundreds of enslaved people. Later, she delivered food to Ireland during the famine of 1879. She served as a training vessel for the midshipmen at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis until 1893. After that, her provenance became a bit fuzzy. In the early 1900s, she became confused with

the ship of the same name that was built in Fells Point and launched in 1797, one of the six original frigates built by the U.S. Navy.

When she eventually landed in Baltimore Harbor in 1968, she was presumed to be that frigate. It wasn’t until she underwent a major reconstruction in the late 1990s that historians concluded that it wasn’t the same ship at all. They determined that the 1797 ship was dismantled in Gosport just about the same time that

caulking. “Paying the seams (smearing

half of the nearly 5,500 linear feet of seams between them, inch by inch.

The plank ends meet at “butt joints,” which are particularly prone to leakage. Rowsom explained that there are no fewer than 220 such joints on

this hull, and to keep them sealed, each one has been covered with a lead patch.

The team of five professional caulkers led by Mike Vlahovich got support from pre-release inmates from Baltimore City Corrections, five young

the seams. These bottom planks between the keel and the waterline are just about all that’s left of the original hull; the rest has been replaced or rebuilt over time. The planks were hewn from the heart of white oak, and some are four inches thick, 18 inches wide and up to 50 feet long. Townsend and the other craftsmen re-caulked about

Black men who are learning a new trade. I met Brandon Blount, a young man whose enthusiasm for the project was evident. He challenged me to a game of trivia and we rattled off facts about the ship at one another. This fellow knows his nautical history. He was particularly interested in Frederick Douglass, another young Black man who worked as a caulker in the shipyards of Fells Point not all that far away. While this is Blount’s first real job experience, it will have been his last before earning his freedom, just as caulking was Douglass’ last job before he escaped slavery.

“I’m liking this experience,” Blount told me. He’s learning all kinds of skills he hopes to put to use when he starts his new life outside the correctional system. Painting the bottom is okay, he says, but he really likes to run the forklift. He asked me to take a picture of him to send to his sister and struck a pose, giving the mammoth rudder a hug.

Chris Rowsom said he’s grateful for their help. “Everybody’s been great, I couldn’t have done this without them. They’ve been a really, really valuable asset, and I think they’ve enjoyed their time here as well. They definitely have a sense of pride that they’re working on a ship with such history, and particularly on a caulking project, because most of our guys are African American, and in the 1850s the Blacks of Baltimore, free and slaves, were primarily engaged in the caulking

trade, so that’s something the guys can relate to from a historical perspective.”

The apprentices are working as part of Living Classrooms’ “Project Serve” program. Project SERVE

(Service, Empowerment, Revitalization, Validation, Employment training) addresses the issue of high unemployment and high recidivism among returning citizens in

Baltimore City. SERVE provides onthe-job training for 150 unemployed adults per year in marketable skills.

The cost of the restoration project—between $850,000 and $1 million—was covered by the State of Maryland, Maryland Heritage Areas Authority, the City of Baltimore’s Capital Cultural Support Fund and Tradepoint Atlantic, which donated the use of the drydock and ancillary support services.

Just eight weeks after the start, on December 19, 2022, with all the seams and butt joints sealed and plied with concrete, and with the hull sporting a new coat of copper-colored bottom paint, the drydock filled up with

Patapsco River water and the ship floated with barely a whisper of a leak. A MacAllister tugboat at her side, the USS Constellation made her way back up the river and moored safely at her berth in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor.

“Constellation is the oldest and largest example of Chesapeake Bay wooden boat building left in existence,” Chris Rowsom told my CBM colleague Cheryl Costello in a video interview for Bay Bulletin. “Once it’s gone, it’s gone. Nobody’s going to be recreating this, so it’s important to preserve. I want our visitors to come away with an appreciation for the people who served aboard her.”

USS Constellation's and its Museum Gallery are located at Pier 1 in Baltimore's Inner Harbor. You can go aboard to take a tour, talk to a crewmember, participate in the Parrott rifle drill, or see what's cooking in the galley. The Constellation also hosts educational and overnight programs for all ages. For information on the Constellation's programs, log onto historicships.org/ explore/uss-constellation.

Through his exploratory voyages in the summer of 1608, Smith visited and mapped the fall lines of all of the Chesapeake’s western shore rivers. The extraordinarily accurate map he published in 1612 served rapid colonization of Virginia and Maryland, though the English treatment of Native communities would prove far less than honorable. As the 17th century progressed, English colonists established trading centers at the fall lines on all of those waterways, as well as the less dramatic heads of navigation on the Eastern Shore rivers. A secondary benefit of those locations was the rapid change in elevation “where the water falleth so rudely.” The resulting energy release made the fall lines good locations for water mills, gristmills and sawmills. We know today that those trading centers turned into villages, then towns, and by the booming 19th century, into cities.

Today, Interstate 95 and old U.S. Route 1 run roughly up the Chesapeake’s western shore fall line. It’s no accident. Once highways took over from rivers for transportation of people and goods, planners laid out those roadways simply to connect the old port cities, from Petersburg on the Appomattox, Richmond on the James and Fredericksburg on the Rappahannock to Alexandria and Georgetown on the Potomac, Elkridge and Baltimore on the Patapsco and Havre de Grace on the Susquehanna. Although the pattern is not as clear on the Eastern Shore, there are cities and towns at or near the heads of navigation on the rivers there, for the same commercial reasons. Each is on a highway. Examples include Millington on the Chester (U.S. Route 301), Denton on the Choptank (Route 404), Seaford (Del.) on the Nanticoke (Route 13), Salisbury on the Wicomico (Route 13), and both Pocomoke City (Route

13) and Snow Hill (Route 12) on the Pocomoke. All those river ports hosted commercial traffic into the mid-20th century before the highways took over transportation. Salisbury still receives regular bulk shipments by river of western shore corn and soybeans for Purdue’s chicken feed mill, and most of these municipalities still have sandand-gravel operations moving product on their waters today.

From a geologist’s point of view, a fall line (or fall zone) is a section of river where a surrounding upland (Piedmont) region meets a coastal plain. The Chesapeake watershed’s Piedmont sits on hard crystalline basement rock, while its coastal plain is softer gravel, sand and mud washed down from the Appalachian and Blue Ridge Mountains over hundreds of millennia. Thus the coastal plain has worn away faster, creating abrupt elevation changes of 50 to 100 feet and resulting rapids. Millions of years ago,

those mountains rivalled the Himalayas in height, but rainfall, freezing, thawing and much time have worn them down, creating the rich soils of the Shenandoah Valley, the Piedmont and the coastal plain.

In that light, it’s worth noting that on an Earth time scale, a fall zone is not a static feature. It recedes upstream as the river slowly wears down the rocks over which it falls, exposing bedrock shoals. Remember that the underlying rock layers of the Chesapeake’s western uplands are not uniform in composition and hardness, either in north-south or east-west directions. Each river has carved its own channel, characteristic of the rocks under its bed. In a river with high flow, the abrupt drop that causes a waterfall may be miles upstream from the geologic boundary between

the Piedmont’s bedrock and the Coastal Plain’s loose sediments, at significantly higher elevation. The waterfall has slowly migrated upstream, towards the west, as the river has eroded the bedrock at the eastern edge of the Piedmont. Geologists tell us the Potomac has etched the upper lip of its Great Falls 14 miles upstream to an elevation around 150 above sea level during the last 2 million years, running over broken rock remnants—including Little Falls—until its bed reaches tide downstream around Theodore Roosevelt Island and the Kennedy Center. Thus, the Potomac’s fall zone has stretched out for that distance.

By contrast, the North Anna and South Anna Rivers (the headwaters of the Pamunkey, and thus of the York), with smaller flows originating only in

the Piedmont, begin their fall zones at elevations around 50 feet and drop to sea level very quickly, so the zones are much shorter, measuring in yards rather than miles.

For a fuller picture of the Chesapeake’s fall lines, it’s worth remembering the forces that shaped these river systems. Over the past 500,000 years, the Chesapeake watershed has gone through three periods of glaciation in which sea level dropped as much as 500 feet while the climate turned cold and locked up water in glaciers to the north during an Ice Age.

In these times, the main river (today’s Susquehanna) flowed from the edge of its glacier in today’s central New York and Pennsylvania. Bounded to the west by the Appalachian and Blue Ridge Mountains and the

Piedmont plateau, it ran south and east, gathering all of the other Chesapeake rivers as tributaries in its lower reaches. On the east, its boundary was the growing spit of coastal plain land built from the Atlantic’s longshore flow and sediments from the Hudson and Delaware rivers.

We know that spit today as the Delmarva Peninsula. It is built on coastal plain gravel, sand, and mud, so its rivers don’t have strict fall lines with rocky rapids. As they carry rain off higher ridges of land, though, their beds reach sea level at the points noted above.

Between its western and eastern shores, the big river cut its channel far across the continental shelf to reach the Atlantic in the region of today’s Norfolk Canyon. During this time, all

of the rivers carved deep channels into their geologically diverse beds.

Around 300,000 years ago, the climate warmed up, the glaciers melted and sea level rose, backing up into the big river’s valley to create an estuary of roughly the same length as today’s Bay. Its mouth appears to have been perhaps forty miles further north, because the Delmarva Peninsula had not grown as far down the coast. In (long) time, sediment filled that estuary. Another Ice Age and thaw around 150,000 years ago created another Bay with a mouth about twenty miles north of the current one. It too filled in before another Ice Age dropped sea level again. Our Bay began forming about 18,000 years ago, as that most recent Ice Age thawed. It reached its current basic shape about 3,000 years ago, though we know all

too well that that shape continues to change before our very eyes.

The story of our rivers’ fall lines carries an important lesson for us. Our Chesapeake is a dynamic system, changing subtly by our quick-time standards, but inexorably. There’s an old saying that “Mother Nature still makes the rules, and She always wins.” We do well to learn to work with her, rather than against.

Note: If you’d like to read a good non-technical summary of this process, check out Chesapeake Quarterly, the magazine of the Maryland Sea Grant Program, at chesapeakequarterly.net. Look in the CQ Archive for Volume 10, Number 1 (2011), The Bays Beneath the Bay.

“And the times, they are a -changing…”

Nobel laureate Bob DylanIf you like boats, and old boats in particular, and you travel up and down Route 50, Maryland’s busy highway to the ocean, you must have noticed Marine Mart and American Outboard. They sit across the road from each other, a mile or so apart, halfway between Wye Mills and Easton, and it seems as if they've been there forever.

They are wild and overgrown and out of place and time, museums for old boats and motors and trailers plopped down in a landscape of grain fields, fast-food shops, motels, strip malls and convenience stores. They’re places where broken things got taken to get fixed, and if they couldn’t be fixed got tucked away somewhere so their bits and pieces could be used to fix other things some day, or maybe never at all.

I’d sped by these places for years, racing along to St. Michaels or Cambridge or the beach, eyes fixed on the destination. Then one day, heading east, I slowed and turned into Marine Mart, which has a big iron gate at the entrance and a winding lane past boats and trailers and mounds of castaway motors leading to the main building, a sprawling, yellow wooden structure tucked against the headwaters of Skipton Creek.

“The county wouldn’t let us put up a sign” on the building, explains the proprietor, Irvin Horn, a gray-haired,

barrel-chested graduate of Easton High who was raised upstairs from the shop, on the top floor of the two-story structure his mom and dad, Ruth and Victor, built from scratch. Because they lived there, it was considered a residence rather than a business, he says with a rueful shake of his mane, so no sign was permitted.

Nonetheless, it’s where he’s worked on boats and outboards from the time he was big enough to turn a wrench, and he’ll soon be 70. First, though, there was a house to build.

“Everything you see here was built with our own trees, poplar and beech,” says Irvin, casting a glance across the lowslung pole barns and sheds that dot the 4 ½-acre tract bordering the tidal creek. The farmer who owned it sold the patch to his dad in 1955, when Route 50 was built and the new highway cut off this little, untillable corner from the rest of his farm.

“The whole place was nothing but trees. My dad had them cut down and he hauled them to the sawmill in Cordova on an old farm wagon. They milled them down to timbers

that we hauled back here and started building.”

When the main house and shop were finished, Victor moved his official Mercury Outboard dealership and his family over from Easton and began selling and fixing boats and motors. Irvin learned the trade by osmosis, at his father’s knee. And so it went, 40 years and more from the 1950s to the turn of the new century, when Victor Horn figured it was time to retire and sell the business to his son, who was keen to take over. “It’s all I ever did,” says Irvin.

He was in his element. “From the 1950s through the 1980s, outboards didn’t really change that much,” he says. “You give me an old two-stroke motor that don’t run, I can give it back to you in two or three days with everything right—rings, cylinders, carburetors, all fresh and running like new.”

Nor was it boring. “Not like on an assembly line where you do the same thing day after day. It’s challenging fixing things. It makes you think. You get deeply involved in something.”

Then, as we all know, along came computers and fuel-efficient fourstroke motors, more like automobiles than marine engines. For old-time mechanics like Irvin, who does not speak computerese, they get harder to work on every year. “The new stuff, it’s not repair. It’s just parts-replacing. You plug it in, the computer tells you what’s wrong, and then you start replacing things. With the old motors, it was knowing the technology and how it works. It made you think.”

As the landscape changed, business slowed and by 2010, Irvin had to drop his official relationship with Mercury. The head office demanded a certain level of sales every year for certification, and Marine Mart was not keeping up.

It was a blow, and a warning sign, but Irvin has a son, Dylan, who is a chip off the old block. Irvin hoped the next generation could make the jump to the new technology and maybe save the operation. Dylan, now 23, gave it a go. He worked alongside his dad as a youngster, learning the things you learn by doing, then after high school went to a marine technology school in Florida for a year and tackled the new language. “I got my degree,” says Dylan, who still works with his dad as Irvin once worked with Victor. “But it was kind of a pain.”

Unlike the old two-stroke motors, the newer, microchip-driven outboards are constantly being updated and

upgraded. Technicians need to keep up, and Dylan found he did not love the work. “You need training every year, and I didn’t take it.”

It doesn’t help that the Horns stayed wedded to Mercurys, which had kept the place going for so long. I once asked Irvin if he could help me out with a balky Johnson I owned that needed some love. He said he didn’t work on Johnsons.

“It’s not that I can’t,” he said. “I won’t!”

If I knew then what I know now, I might have taken that motor across the road to Dora Kawalek and her two grandsons at American Outboard, which has the same worn, overgrown appearance as Marine Mart, with old boats in the yard and dimly lit rooms full of antique outboards and parts inside, in various stages of repair and decay. Dora’s place is a little fresher— they opened in 1985—and her grandsons are well versed in the computer world, though they still prefer the older two-strokes, and specialize in digging up parts for antique motors that folks can order online from across the country and around the world.

But Dora’s place is a story best held for another day. They’ll be around for some time.

I’m more concerned with the sad prospect of one day crossing Skipton Creek on my way east, taking a glance to the right halfway up the hill and finding no more the emerald-green oasis called Marine Mart. No more acres of boats, motors, trailers, hoists, consoles, bearings, gaskets and carburetors. No winding lane, no smiling Irvin, scratching his head to reflect on where he might dig up a replacement for that tilt-and-trim part you need, or some springs for your sagging boat trailer.

“I’m getting ready to retire,” he says, “and I’m not sure the boy is going to keep it going.”

“It’s a pretty piece of property,” I say. “Someone will surely want to buy it.”

“You think?” he says.

Let’s just hope it’s not just another soulless convenience store.

Getting restless while your boat’s on the hard? You don’t have to. Winter is a great time to cruise around the Bay, even if you need to do it in a car. Instead of summertime crowds, you’ll encounter a whole new set of visitors in the form of locals out enjoying their own towns and wildlife happy to have the run of the place for the season. Here are a few ideas offering unique locations, cozy features and a bonus: discounted rates over what you’ll find at peak season. But great escapes await all around the region. So pack up the car and discover that beauty that is off season.

BY SUSAN MOYNIHAN

If you need a reminder that our nation’s capital of marble monuments and grassy expanses is also a riverfront city, head down to The Wharf. This Southwest section along the Potomac has a long history of waterfront commerce that continues today. The piers are home to a working marina, with plenty of slips for residents and transients, as well as ferry service (reopening in March) that connects you with spots like Georgetown, National Harbor and Alexandria.

The complex is edged at the north end by The Municipal Fish Market, the last vestige of the country’s oldest fish market, which still sells fresh and prepared seafood to go. (It opened in 1805, 17 years before that more famous one at New York’s Fulton Street.) The rest of the area has been transformed into a blocks-long waterfront boardwalk with a slew of shops, theaters (including The Anthem, one of the city’s top concert venues) and restaurants, plus many floor-to-ceiling windows and decks to take in the views. The area is hopping in summer months, as D.C. denizens and visitors come to take in the energy. In the winter, it’s a more serene affair, which is exactly the appeal.

The 131-room Pendry Washington DC towers over the southern Phase 2 of the complex, just finishing completion. It’s a breath of fresh air. Interiors are modern and chic, with emphasis on the views of the Potomac River or the capital skyline. (Book a riverfront room

and you can watch the comings and goings on the river and at DCA from bed.) The stunning penthouse restaurant Moonraker—named after the mast topper, not the James Bond film—features sharable sushi and Japanese whiskeys, with stunning views in every direction, both from indoors and the open-air wraparound deck. Or go old-school with drinks and nibbles by the fireplace in clubby Bar Pendry, just off the lobby. The secondstory pool deck is a sweet place to soak up Vitamin D on sunny winter days, and the hot tub beckons the brave all year round. Or hit the eucalyptus steam room before getting a treatment in the spa. And while The Wharf gets quieter in colder months, it never closes. Keep an eye out for events like Curling and Cocktails, and touring bands making a stop at The Anthem, which is a five-minute walk away. pendry.com/washington-dc; washington.org

The Middle Peninsula of Virginia’s Chesapeake region is still somewhat of a secret. Although it’s less than three hours from the nation’s capital and half that from the world’s largest naval base at Naval Station Norfolk, you’d never think so by driving the rural byways that wind through the low landscape, home to farms, small towns and small marinas that cater to working watermen and recreational boaters along the York and Rappahannock rivers and their myriad creeks and bays.

Even when you’re driving in, you’d be well served to bring along some inflatable kayaks; Mathews County is considered one of the top kayaking spots along the Virginia coast. And winter is a great time to visit places like New Point Comfort Lighthouse. This 63-foot sandstone tower was

commissioned by Thomas Jefferson in 1801, and is the 10th oldest lighthouse in the country. It’s not accessible by land, so drop in a pair of kayaks and explore it at your own pace, without the crowds. If you want to stroll, Bethel Beach Natural Area Preserve’s sandy shoreline is ever-changing and a

great spot for beachcombing. Boater’s favorite (and repeat CBM Best of the Bay winner) Hole in the Wall Grill at nearby Gwynn’s Island stays open all year, offering fresh seafood and full-on views of the Bay.

The Inn at Tabbs Creek is a restful home away from home, overlooking a scenic tributary of the East River. The family-run B&B has seven rooms, all unique in style and all with water views. Winter stays are up to 25% off summer rates (and even better on weekdays), which means you can upgrade to one of their three oversized suites, each with its own patio and firepit, plus kitchenette and jacuzzi tub indoors. Ask owners Greg and Lori Dusenberry about their special that includes a complimentary bottle of wine and cheese board on arrival, just to make it that much cozier. If you didn’t bring your own kayaks, no worries; they have some on hand, as well as bicycles for exploring. innattabbscreek.com; visitmathews.com

Kent Island is loads of fun in the summer, with all the busy dock bars and waterfront seafood restaurants, all the pleasure boats and waterman’s workboats scurrying up and down the Narrows. In the winter it’s an altogether mellower affair, a small community left mainly to the residents who live there year-round. Its prime position as the connecting point between Maryland’s Western and Eastern Shores also makes

it a magnet for migrating waterfowl, who kick back here on vacation like we humans do in summer.

There are ample ways to see them. Climb the towers at Chesapeake Heritage and Visitors Center for views of the Narrows and Chester River and Eastern Bay beyond, or walk the boardwalk at Ferry Point Park, where swans and snowy owls make regular appearances in the off season. The Cross Island Trail is a paved bike path that runs the length of Kent Island. It gets crowded in warmer months but from January through March you may have it all to yourselves, which means taking it at your own pace with lots of impromptu stops along the way.

Located just off the first east-bound exit from the Bay Bridge, The Inn at Chesapeake Beach Club is a cozy and convenient place to check in. The inn is a favorite for wedding groups in the summer (their venue is tops in the region) but in winter it’s more low-key, with couples and families looking for a

scenic staycation. Choose from rooms in the main lodge, 18 rooms in The Barn or five cottage suites; all are decked out in clubby, homey style. After a day exploring, take a seat by one of four firepits located in across the grounds, and enjoy bites and drinks from the onsite to-go Market or their flagship Knoxie’s Table, known for stellar food sourced from local

purveyors. Or stroll across the marina to Libbey’s Coastal Kitchen + Cocktails, which opened in summer 2022 (in the former Hemingway’s space) to regional acclaim. You can use the average $100 off summer rates for treatments at the spa, along with time in their eucalyptus sauna. baybeachclub.com/the-inn; visitqueenannes.com

Back in the mid-1600s, when Bohemian merchant and cartographer Augustine Hermann was running his farm in what is now Cecil County, Md., he thought that connecting the Delaware River to the Chesapeake Bay would be a game-changer for the region. He was right, but construction on what is now called the C&D Canal didn’t begin until 1824, with the earliest version (hand dug and only 10 feet deep) opening five years later. In 1919, the federal government took over the

private project, and today the 14-mile long, 35-foot deep canal is one of the busiest in the world, bringing freight, cruise ships and recreational vehicles along the watery corridor that saves them approximately 300 miles from going “the long way” around the Delmarva Peninsula.

You can’t visit the C&D Canal Museum in the winter—it’s only open weekends from Memorial Day through Labor Day—but you can walk alongside it; the Ben Cardin C&D Canal Recreational Trail runs 15 miles along the north side of the canal, ending at Delaware City. In winter, canal traffic is more freighters and cruise ships than recreational boaters, and watching them squeeze down the narrow channel and slide under the arcing bridge is a must-see experience. Chesapeake City’s historic downtown, located on the southern bank, is one of the prettiest towns on the Bay. Much of it dates to the mid-1800s, and wood-frame cottages and stately granite halls have been turned into shops, restaurants and B&Bs. The town has winter pop-up events, like the mid-February Sip and Stroll.

Built as a private residence in 1920, the 10-room Ship Watch Inn is the only lodging directly overlooking the canal. Every room has a sundeck facing the water, and most of them have jacuzzi tubs as well, a great place to warm up if you work up a chill. Come weekdays for solitude and pricing specials, or visit on weekends and mingle with other guests in the communal sitting room. You’re a short stroll from historic Bayard House Restaurant, as well as Chesapeake Inn Restaurant and Marina, a popular

spot for dock and dines. You’ll have to drive to get to Chateau Bu-De Winery; built on the former land of the visionary Hermann, but their cozy tasting room is a great place to toast to his vision, and to the melding of past and present. shipwatchinn.com; chesapeakecity.com

Since its opening in 2020, POV Restaurant at Pier450 has become the destination dining spot for St. Mary’s County, Md. Chef Carlos’ crab balls are one of the reasons why. His elevated take on a Southern Maryland staple makes the perfect savory bite for any season, so they stay on the menu year-round.

When you’re looking to change it up, keep an eye out for their “Chef’s Tastings” dinner series as well. Chef Carlos takes diners on a culinary journey with themed dinners reflecting different cuisines around the world. Held biweekly on Sunday nights, these special menus range from three to five courses.

DRY INGREDIENTS:

1 ¼ cup cornmeal

1 ¼ cup all-purpose flour

2 Tbsp sugar

½ tsp baking soda

½ tsp baking powder

1/8 tsp black pepper

¼ tsp salt

WET INGREDIENTS:

1 cup of buttermilk

1 egg

2 Tbsp vegetable oil

3 Tbsp grated onion

3 Tbsp finely diced jalapeños (no seeds)

1. In a medium-sized bowl, whisk the dry ingredients together.

2. Add the dry ingredients to wet ingredients.

3. Heat oil in a pan to 365 degrees.

4. Use medium-sized ice-cream scoop to spoon each hush puppy carefully into the oil.

5. Fry until the hush puppies are fully cooked inside.

INGREDIENTS:

1 lb. jumbo lump crab

1 Tbsp Old Bay

½ cup panko

½ cup mayo

1 egg

2 tsp Dijon mustard

1 tsp Worcestershire sauce

INSTRUCTIONS:

1. Fold and mix ingredients together without pressing.

2. Let sit for 10 minutes.

3. Mix 1 cup panko with 1 Tbsp Old Bay.

4. Form crab balls into desired sizes and roll into panko mix.

5. Fry at 365 degrees.

INGREDIENTS:

1 cup mayo

1 tsp. cajun spice

1 tsp. paprika

1 Tbsp. pre-prepped horseradish

¼ tsp. cayenne

1 tsp. lemon juice

¼ tsp. salt

¼ tsp. pepper

2 Tbsp. dijon mustard

INSTRUCTIONS:

Whisk together all ingredients and serve on the side.

The Northern Neck and Middle Peninsula of VA have the most beautiful waterfront and fantastic small towns on the entire East coast! Let us help you navigate buying your waterfront getaway. With over 60 years of combined experience, our family of Realtors has intimate knowledge of the rivers and roadways and can help you find the home or property that best suits your goals. That’s why we have been the top producing agents in Long & Foster for the Northern Neck and Middle Peninsula since 2013. We are passionate about the Chesapeake Bay Lifestyle and are eager to share it with you!

Please visit our property websites to view interactive floor plans, aerials, maps and more! 804.724.1587 •

Your Northern Neck & Middle Peninsula of Virginia Real Estate Specialists

Your Northern Neck & Middle Peninsula of Virginia Real Estate Specialists

Denise Neitzke REALTOR®/Team Member

Chris McNelis Associate Broker/Team Leader

Ashley Burroughs REALTOR®/Operations Coordinator

Will Hooper REALTOR®/Executive Assistant

Announcing our new Team Member

Megan Erickson REALTOR®

Look for her in our future ads!

O 410-394-0990

M 410-610-4045

Web: mcnelis.penfedrealty.com

Waterfront. Land and Farm. Condominium. Commercial.

Serving Southern Maryland and the Patuxent River region since 1992

Megan Erickson REALTOR®/Team Member

Denise Neitzke REALTOR®/Team Member

Chris McNelis ASSOCIATE BROKER/ Team Leader

Will Hooper REALTOR®/Executive Assistant

A member of the franchise system of BHH Affiliates, LLC

Announcing our new Team Members Lacey Foerter, REALTOR® and Kyle Antel, REALTOR®. Look for them in our future ads!

O 410-394-0990

M 410-610-4045

Web: L veChesapeake.com

Waterfront. Land and Farm. Condominium. Commercial.

Serving Southern Maryland and the Patuxent River region since 1992

..............................................................

50359 Scotland Beach Rd - 2616 SF

POINT OF LAND with 4BR/3.5BA home w/ 2 car garage on quiet Tanner Creek w/ access to the Chesapeake Bay. Impressive retreat on 1.7 acres with 600 ft of shoreline, big water views, private pier. Great fishing location, high speed internet. Plan your getaway here!

$775,000

259 Cove Drive, Lusby MD

NEW WATERFRONT HOME with main level living and oversized garage and open living plan near Solomons. 2717 SF + walkout basement and extra lot. Private pier on protected cove with access to the Chesapeake Bay. Drum Point community has a boat ramp, beaches, lakes and more!

$985,000

$1,575,000

$1,345,000

$1,300,000

lYons landing

WATERFRONT brick property located on 2.27 acres with panoramic views of the Poquoson River. SALT WATER POOL, hot tub, outdoor shower, pool house and upstairs balcony with Treks decking.

$1,100,000

smithfield

Deep water! Almost 11 acres. Refinished hardwood floors throughout the first floor, 3 bedrooms downstairs, with 1 bonus room upstairs and an amazing open floor plan with giant windows.

$649,900

YorktoWn

Gorgeous 4 bedroom 3 bath home. Beautiful landscaping, large kitchen w/ island, first floor bedroom and full bath, large sunroom. 1.72 AC lot w/ extremely large outbuildings for storage or entertainment space.

Chisman Creek

VERY RARE OPPORTUNITY! Deep water access in highly coveted York County! Dock has 2 jet ski lifts and 2 boat lifts. Elevator, backup generator, open concept kitchen and living room, sun room, library, and more!

$1,000,000

YorktoWn

7-bedroom, 7-bathroom, 6,900 sq ft home with 3 ensuites, one on each level, MEDIA ROOM, office and formal living room. Full walk out basement w/ in-law suite and indoor solar heated pool & hot tub!

$600,000

suffolk

5 bed, 3 full bath, gourmet kitchen opens into the great room with gas fireplace and access to the backyard. Home office and one bedroom with en-suite bathroom on 1st floor. Whole home gas generator.

kingsmill

All brick 5 bedroom 3.5 bathroom home. LARGE kitchen w/ double ovens, granite countertops, stainless steel appliances. Family room with cathedral ceilings and gas fireplace. 1st floor primary bedroom.

$650,000

Williamsburg

Extremely private, on a double lot in Seasons Trace. 2nd floor primary bedroom with 2 walk-in closets, 2 additional bedrooms and full bathroom. Basement features 2 more bedrooms and a full bathroom.

$470,000

Williamsburg

5-bedroom & 3-full bathroom brick home with a first floor bedroom & full bathroom! Open floor plan, large family room.

Ifirst met Ruffian shortly after moving to Eastport, the maritime working-class neighborhood of Annapolis, where Black and white families had lived in relative harmony for generations. I had moved in with some other quirky housemates and found a job with Annapolis Boat Shows. My way around at that time was my old canoe—a 17-foot, square-stern Grumman aluminum that my Dad had bought when I was six. I poked up and down all the creeks and eventually discovered a little stretch of beach on the far side of the mouth of Back Creek.

The beach was deserted when I scuffed the bow up onto the sand, but before I could step ashore, a big black dog appeared and spat a huge chunk of driftwood at my feet. He stood there, staring at me expectantly, so I dutifully picked up the hunk of wood and chucked it as far as I could into the water. He charged after it, grasped it in his jaws, brought it back and spat it at my feet again.