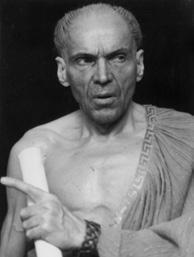

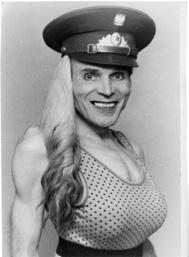

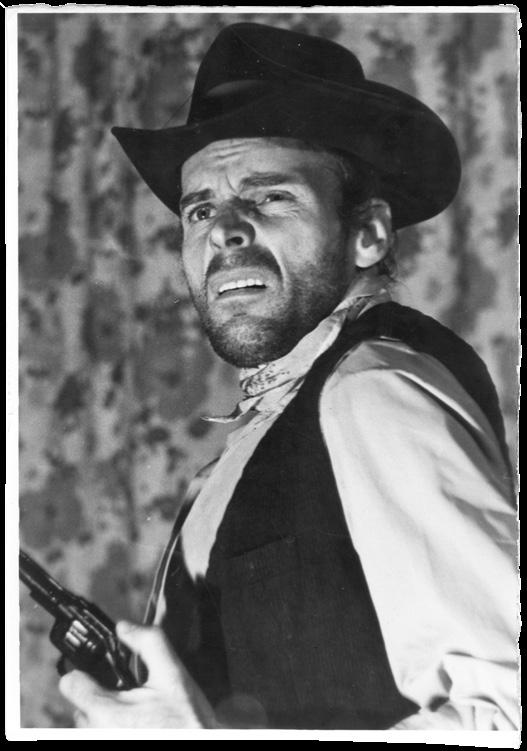

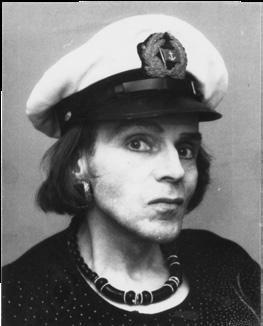

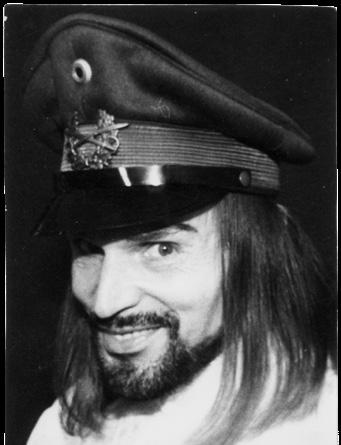

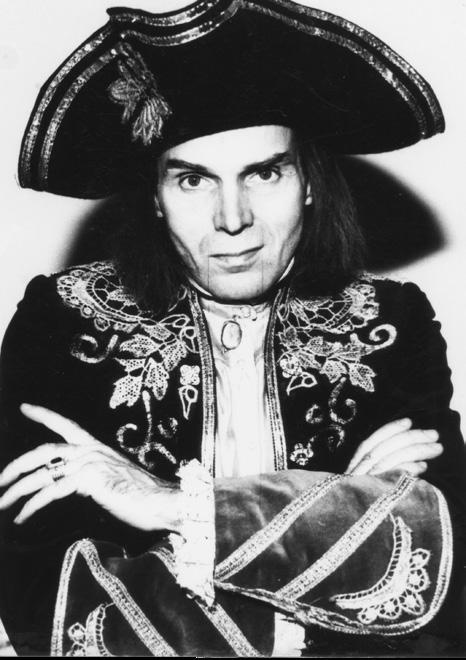

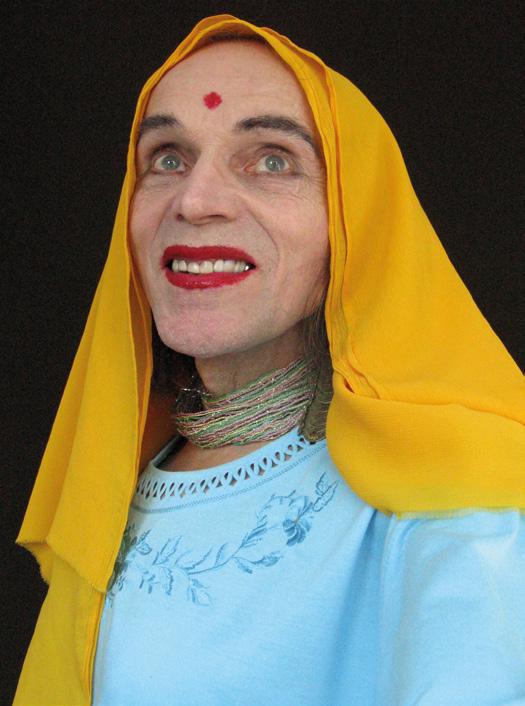

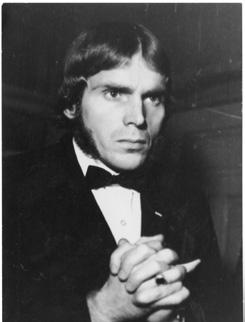

tomasz machciński, c.1988. © henryk dederko

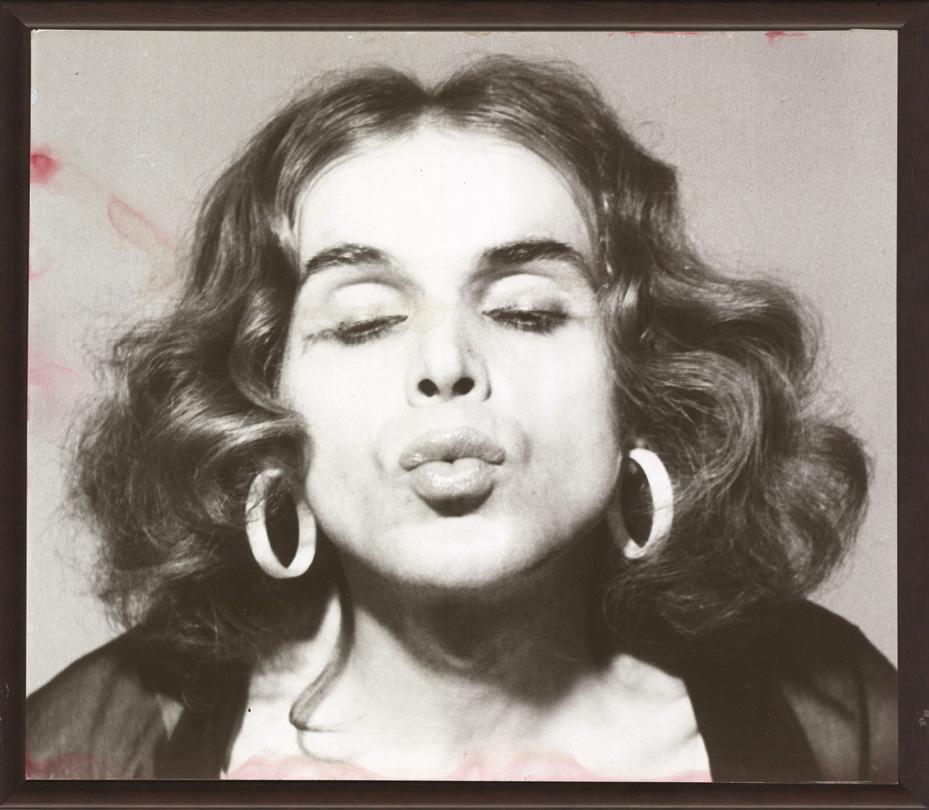

tomasz machciński, c.1988. © henryk dederko

I made it all because of you Tomasz Machcinski

avant-propos foreword christian berst

american dream I made it all because of you zofia płoska-czartoryska & katarzyna karwańska

un acteur, un poète, et un pirate will heinrich

la sybille et le phénix marc donnadieu

œuvres works texts in english portfolio

photo dédicacée par joan tompkins à tomasz machciński en 1947. © fondation tomasz machciński

Le rêve américain, c’est celui d’un ouvrier mécanicien polonais, né en 1942 près de Varsovie, orphelin de guerre et atteint de tuberculose osseuse. Son destin bascule lorsque, à l’âge de trois ans, dans le cadre d’un programme “d’adoption à distance”, il reçoit un mot de l’actrice hollywoodienne Joan Tompkins, avec la mention « Avec amour, à "Tommy", de “mère” Joan ».

Le jeune Tomasz Machciński se construit alors, durant près de vingt ans, avec la conviction que cette dernière est véritablement sa mère. Lorsque la brutale réalité le rattrape, il se lance pendant plus d’un demi-siècle dans une quête éperdue d’identité à travers des milliers d’autoportraits photographiques.

C’est comme si, à partir de 1966 – soit une décennie avant Cindy Sherman –, Tomasz voulait endosser tous les rôles, hommes ou femmes, indistinctement.

Or, s’il est vrai que les clichés de Sherman et de Machciński entrent formellement en résonance - chacun jouant sur le registre de l’autoportrait décalé – quelques antinomies fondamentales affleurent.

D’abord parce Sherman se place délibérément dans la perspective de l’art conceptuel, destinant résolument son travail aux autres, tandis que Machcinski, privé d’une identité qu’il tenait longtemps pour acquise, paraît multiplier les combinaisons pour trouver la sienne.

En somme, même si les deux se saisissent pareillement de figures iconiques et que leurs photographies infèrent de l’esthétique populaire – celle du cinéma, des personnages historiques ou de la publicité – Sherman déconstruit ces codes collectifs tandis que Machciński les met au service de sa reconstruction.

L’une tend un miroir à la société, la prenant à témoin, l’autre regarde derrière ce miroir pour trouver qui se cache en lui. Elle dit « regardez-vous », il dit « regardez-moi ».

Chacun prenant sa source dans sa propre image pour révéler aussi bien l’hybris que la psyché.

Joan Tompkins, au crépuscule de sa vie, finira par s’enorgueillir d’avoir inspiré ce grand œuvre, tandis que Tomasz, dans un mouvement inverse, revendiquera seul la paternité de ses créations, et ce jusqu’à sa mort en 2022.

« En vérité, vous ne sauriez porter masque meilleur, vous mes contemporains, que votre propre visage ! »

F. Nietzsche

En 2018, la Fondation Tomasz Machciński est créée et dès 2019, ses oeuvres sont présentées aux Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie d’Arles dans l’exposition

Photo | Brut.

Acclamé en 2021 à Paris Photo, sa présentation à l’Independent Art Fair en 2024 fera dire au New York Times que « l'événement le plus mémorable de la foire sera les débuts américains du photographe polonais Tomasz Machciński ».

Zofia Płoska-Czartoryska est commissaire d'exposition indépendante et auteure basée à Varsovie.

Elle est diplômée de l'université de Maastricht et de l'université de Varsovie. Dans le passé, elle a été associée à la galerie Marian Goodman à New York et au musée d'art moderne de Varsovie, où elle a occupé le poste de conservatrice et cheffe de projet international.

Avec Katarzyna Karwańska, elle a été cocommissaire des expositions : "Why We Have Wars : The Art of Contemporary Outsiders" (Musée d'art moderne de Varsovie, 2016), "With Love to Tommy" (Fondation Tomasz Machciński, 2019), et "Polska/Ziętek : The Gymnast" (Fondation Dzielna, 2023).

Zofia Płoska-Czartoryska a reçu la bourse Huygens du gouvernement néerlandais et le prix de la Fondation Gessel pour Zachęta.

Katarzyna Karwańska - conservatrice, productrice et fondatrice de la Fondation Tomasz Machciński. Depuis 2008, elle est responsable du développement des archives cinématographiques de la créativité amateur (Amateur Film Clubs et Polish Archive of Home Movies) au Musée d'art moderne de Varsovie. Son principal domaine de recherche est le travail des artistes marginaux engagés qui opèrent indépendamment du monde de l'art professionnel, ainsi que la créativité amateur et anonyme. De 2020 à 2021, elle a dirigé la galerie Incognito à Varsovie. Entre 2009 et 2017, elle a collaboré avec l'artiste Paweł Althamer sur le projet public du parc de sculptures de Bródno.

Parmi les expositions organisées par Karwańska : "Atomic Love Story" à la Fundacja Dzielna à Varsovie (2022); "You’ve Gone Incognito. Cross-dressing and Home Photo Sessions" au Fort Institute of Photography de Varsovie (2021); "Different Faces, Different Places": a solo exhibition of Tomasz Machciński au Manggha Museum of Japanese Art and Technology in Cracovie (2021); "Magda": a solo exhibition of Zbigniew Libera à la Incognito Gallery à Varsovie (2020); "With Love to Tommy" (co-curated with Zofia Czartoryska), Warsaw Gallery Weekend (2019); "House of Colonels. Girl and Gun" au Fuerteventura (2018); "I'm no longer a dog" (co-curated avec Zofia Czartoryska), Silesian Museum de Katowice (2017); "Why We Have Wars. The Art of Contemporary Outsiders" (co-curated avec Zofia Czartoryska), Museum of Modern Art de Varsovie (2016).

I made it all because of you

zofia

płoska-czartoryska & katarzyna karwańska

Dans le film classique hollywoodien Anastasia de 1956, Ingrid Bergman incarne une jeune fille orpheline et amnésique qui en vient à croire qu'elle est l'une des rescapées de la dynastie des Romanov –la grande duchesse Anastasia. Dans le Paris des années 1920, des exilés russes, fuyant la révolution, voient en elle l'opportunité de mettre la main sur une fortune. Ils s'empressent de la façonner pour qu’elle adopte les manières et le comportement d’une princesse, car sa ressemblance physique frappante renforce cette illusion. La jeune femme semble peu à peu retrouver la mémoire et joue ce rôle avec une telle conviction que même le spectateur doute de sa véritable identité. L'impératrice douairière Maria Fedorovna, la grand-mère d’Anastasia, finit elle-même par la reconnaître comme sa petite-fille. Pourtant, dans la scène finale, la jeune femme décide de renoncer à son passé et choisit de fuir avec l'homme qu'elle aime, préférant se réinventer une nouvelle fois. Quelques années avant que l'interprétation d'Anastasia par Bergman, qui a remporté

un Oscar, ne fasse sensation parmi les cinéphiles du monde entier, l'aspirante actrice américaine Joan Tompkins a contacté l'organisation caritative "Foster Parents Plan" à New York, qui gère un programme d'adoption à distance pour les enfants orphelins de la Seconde Guerre mondiale en Europe. Dans le catalogue, elle voit la photo d'un garçon alité appelé Tomasz Machciński, originaire de Pologne, décide de s'engager dans une relation qui, pour l'essentiel, consistait en un échange de lettres et l'envoi de petits cadeaux (elle avait reçu pour instruction de ne pas le gâter, car « ils commencent toujours à vouloir venir en Amérique, et nous devons les en dissuader1 »).

C'était en 1946, j'avais quatre ans, et je me trouvais au Nid des Orphelins à Myszków, dans le district de Szamotuły, puis au sanatorium de Kamienna Góra, où je suis resté alité pendant près de six ans, dans un lit de plâtre, suspendu par un treuil, avec un sac de cinq kilos attaché au lit, et un sac de sable sous ma bosse.

Je ne savais pas qui étaient ma mère ou mon père. Le plafond à carreaux était mon ciel.

It was 1946, I was four years old, I found myself in the Orphan's Nest in Myszków, in the Szamotuły district, and then in the sanatorium in Kamienna Góra, where I lay for almost six years in a plaster bed, on a lift, with a five-kilogram sack, tied to the bed, with a bag of sand under my hump. I didn't know who my mum or dad was. The checkered ceiling was my heaven.

extrait de l'interview avec katarzyna biełas, 2019.

Lorsque Machciński reçut sa première lettre signée « Amour à Tomasz de Maman Jennie », il n'avait que trois ans. Durant les années qui suivirent, passées dans des hôpitaux, orphelinats et écoles spécialisées, il crut fermement que Joan Tompkins était sa véritable mère. Quelques fois par an, elle lui envoyait des photos de tournage de ses nouvelles productions et lui donnait des nouvelles de sa carrière et de son déménagement à Hollywood. Lorsque leur correspondance s’interrompit pendant quelques années en raison de l’ère McCarthy et de sa méfiance envers les liens avec le bloc de l’Est, Tomasz entreprit de la rechercher ainsi que d’autres proches via la Croix-Rouge, découvrant ainsi la véritable destinée de ses parents : son père avait été assassiné par les nazis et sa mère était morte de la tuberculose peu après sa naissance. Cette crise identitaire, alors qu'il approchait de l'âge adulte, fut encore aggravée lorsqu'il obtint le statut officiel de citoyen handicapé –une étiquette qu'il trouvait absolument inadaptée à ce qu'il ressentait au plus profond de lui-même. Il se sentait spécial.

Installé dans la ville de Kalisz, il trouva un emploi de mécanicien de bureau. En 1966, il entreprit un projet artistique solitaire de longue haleine, consistant en 22 000 autoportraits photographiques dans lesquels il se métamorphosait en célébrités, figures historiques, personnages fictifs et types humains de tous genres, ethnies,

classes sociales, morales et styles. Prenant conscience qu’il avait bâti son identité sur la fantaisie, il se sentit libre de se lancer dans un travail inlassable d’auto-fiction ou, pour reprendre les mots de Susan Sontag, d'"auto-adulation"2. Ne disposant que de matériaux rudimentaires dans cette ville provinciale polonaise, il se comportait dans son art tel le plus extravagant des dandys. Dans nombre de ses premières photographies, il se glisse dans la peau d’archétypes hollywoodiens tels que des cow-boys, des femmes fatales, des amoureux de cinéma ou des athlètes –des incarnations qui lui permettaient de se montrer sous un jour séduisant, transcendant ainsi les limites physiques de son corps. Les photos de films qu'il recevait encore de Joan Tompkins étaient une influence évidente, tout comme les grandes stars de l'écran, notamment Humphrey Bogart, Liza Minnelli et sa préférée, Marlene Dietrich. Il explorait minutieusement les clichés liés aux genres et aux rôles sociaux, poussant les stéréotypes à l'extrême, prouvant ainsi que son rapport à la culture pop américaine n'était jamais un simple acte d'adoration ou d'imitation. Rapidement, il s'intéressa à une vision bien plus fluide de l'identité humaine et de sa relation avec l'apparence. Il se mit à poser en tant que figures audacieusement androgynes ou intersexuelles, ou à exposer son corps déformé, cherchant toujours à atteindre plus d’ambiguïté et

2. Susan Sontag, Notes on Camp, 1966, https://monoskop.org/images/5/59/Sontag_Susan_1964_Notes_on_Camp.pdf

d'excès (une liberté absolue qu'il obtint dans ses photographies numériques colorées des dernières années de sa vie).

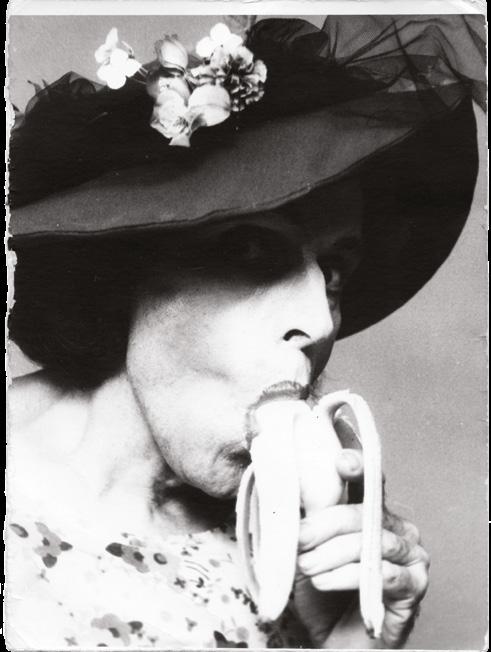

« Le propre du Camp3 est l'esprit de l'extravagance. Le Camp, c'est une femme se promenant dans une robe faite de trois millions de plumes. Le Camp, ce sont les tableaux de Carlo Crivelli, avec leurs véritables joyaux, leurs insectes en trompel'œil et leurs fissures dans la maçonnerie. Le Camp, c'est l'esthétisme outrancier des six films américains de Sternberg avec Dietrich », écrivait Sontag dans ses célèbres

Notes on Camp, publiées à New York à la même époque où Machciński commençait à prendre ses clichés. « Le Camp voit tout entre guillemets. Ce n'est pas une lampe, mais une "lampe" ; ce n'est pas une femme, mais une "femme". Percevoir le Camp dans les objets et les personnes, c'est comprendre l'Être-comme-Jeu-de-Rôle.

C'est l'extension ultime, en sensibilité, de la métaphore de la vie comme théâtre. » Ces remarques sont étrangement adaptées à la stratégie artistique de Machciński, bien que son. travail ait émergé indépendamment, dans des circonstances géopolitiques et personnelles totalement différentes, incorporant de nombreuses autres influences culturelles, aboutissant à l'un des projets d'art total les plus originaux de l'histoire de la photographie.

Dans sa défense publique du film expérimental censuré de Jack Smith, Flaming Creatures (1964) – un exemple classique de Camp – Sontag faisait l’éloge de son exécution brute et de l'orgie libre d’une sexualité indéterminée et d’une imagination issue de films ringards et de la culture de masse. Déçue par les critiques et les cercles artistiques, elle affirmait : « Ce genre d'art doit encore être compris dans ce pays4 ». Ce genre de transgression des normes sociales et de défi au « bon goût » pouvait-il être compris dans une ville provinciale de la Pologne communiste ? Surtout lorsqu'il était exécuté par un amateur, sans le soutien de la théorie de l'art et des cercles subculturels ? Machciński –dont le travail, tout comme celui de Smith, explorait « les impasses de l'identité », bien que d'un point de vue existentiel totalement différent – dut attendre plus d'un demisiècle pour être enfin remarqué par le monde de l'art en tant que pionnier du tournant performatif.

En 1991, Joan Tompkins écrivit un livre fictionnalisé, Tomek, sur leur relation inhabituelle à distance qui avait duré des décennies. « C'est une histoire vraie », affirmait la vétérane de l'industrie cinématographique. Pourtant, étonnamment, elle lui donna une conclusion fictive, empreinte du rêve américain.

3. Dans Notes on "Camp", un essai écrit en 1964 par Susan Sontag, le terme Camp est défini comme une sensibilité esthétique qui valorise l'artifice, l'exagération, l'ironie et l'extravagance.

4. Susan Sontag, Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures, The Nation, 1964, access: https://thenation. s3.amazonaws.com/pdf/feast1964.pdf

Dans les derniers chapitres, elle décide d'emmener Tomek au pays de ses rêves –l'Amérique, où il pourra enfin exposer son travail. « Tu as été Quelqu’un pour moi pendant plus de quarante ans. Maintenant, je prie pour que tu deviennes Quelqu’un en Amérique »5, lui écrit-elle dans une lettre d'invitation au ton impérialiste. Le style mièvre n’est pas surprenant – après tout, elle avait passé la majeure partie de sa vie à jouer dans des films mélodramatiques en tant qu’actrice de second rôle. Tout le livre est un autoportrait en tant que mère affectueuse et altruiste venue d’un monde meilleur pour un orphelin misérable de l’autre côté du rideau de fer – une œuvre d’auto-fiction et d’auto-adulation en soi.

Tomasz et Joan se rencontrèrent à Los Angeles quelques années plus tard à l'initiative de la cinéaste polonaise Alicja Albrecht, qui réalisa un documentaire sur lui intitulé Child from a Catalog. Dans l'une des scènes, « Maman Jennie » l'emmena à Disneyland, et dans une autre, Tomasz, déambulant sur le Hollywood Walk of Fame, signa de son propre nom une étoile vide, à l'image de la vie qu'il avait menée. Leurs grandes fictions de l’amour véritable, de la célébrité et du faste de la vie américaine se heurtèrent finalement à la réalité.

« Elle n'était finalement pas Anastasia », déclare le prince déchu du Danemark après que le personnage interprété par Bergman s’enfuit. L'ancienne impératrice répond alors : « N'était-elle pas ? ». Et elle ajoute : « La pièce est terminée. Rentrez chez vous. » 5. Joan Swenson, ibid. p. 202

Will Heinrich est né à New York et a passé sa petite enfance au Japon. Il est critique de galeries, d'expositions de musées et de foires d'art pour le New York Times et rédige des nécrologies d'artistes. Il a également écrit pour le New Yorker, le New York Observer, Hyperallergic, Art in America, Jewish Currents et The Nation. Son roman The King's Evil, publié par Scribner en 2003, a obtenu une bourse PEN/ Robert Bingham en 2004. Son dernier roman, The Pearls, a été publié en 2019 par Elective Affinity.

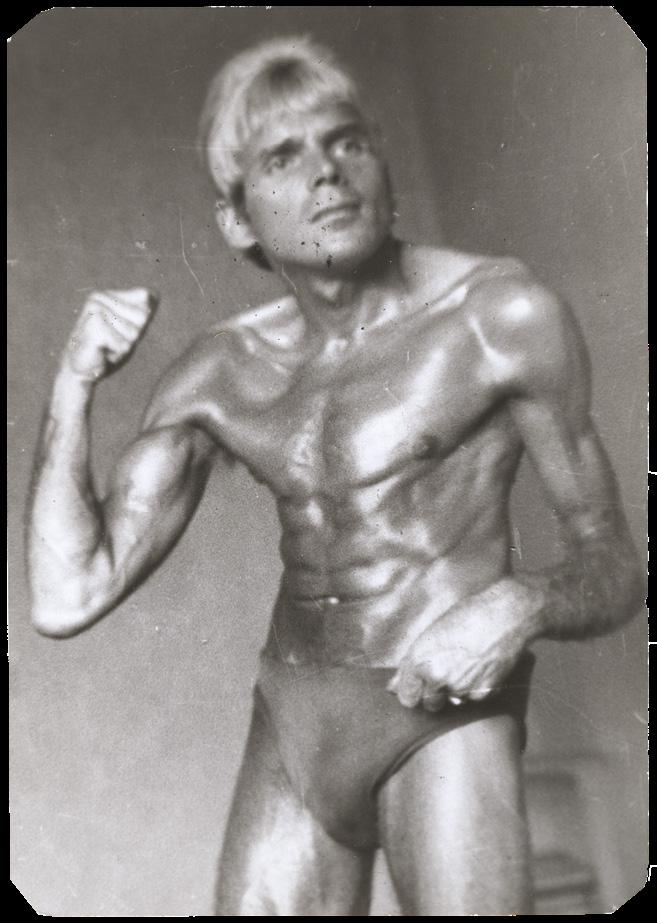

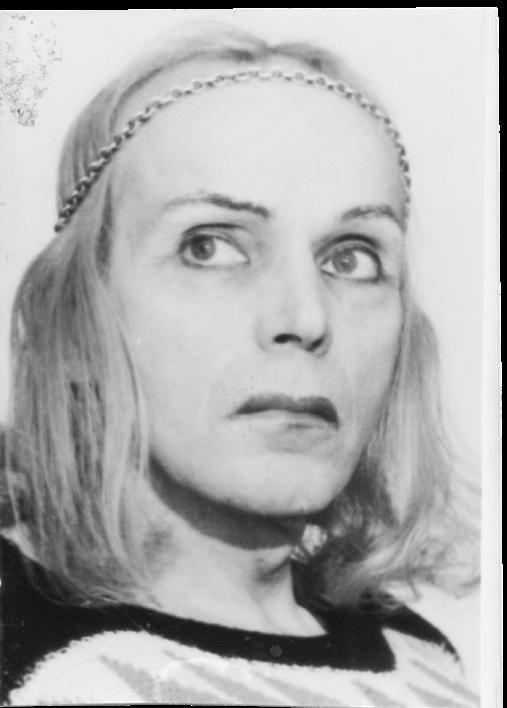

will heinrich

Tomasz Machciński était un acteur, un poète, un pirate, un mystique. Il était un sénateur romain, un rock-and-roller miteux, un culturiste huilé, une ingénue coquette avec des pommes ou des oranges à la place des seins. Il était un enfant espiègle et un don juan fatigué du monde. Il pouvait être beau, quelconque ou laid, selon l'occasion ; il se laissait pousser la moustache et la barbiche sur commande ; et il était toujours prêt à cacher son pénis à l'abri des regards entre ses jambes. Au début de sa carrière, il incarnait souvent des personnages historiques comme Hitler ou Gandhi. À la fin de sa carrière, il faisait apparaître des personnages moins identifiables, mais non moins spécifiques, et les incarnait avec un dédoublement magistral et fascinant. À travers leurs visages, leurs gestes et leurs costumes parfaitement réalisés, il laisse transparaître son propre caractère extraordinaire.

Dans la « vraie vie », bien sûr, Machciński était un orphelin de guerre polonais qui avait une femme, un fils et un diplôme d'ouvrier spécialisé, et ses autres rôles ne concernaient que les centaines d'autoportraits élaborés et fictifs qu'il créait en tant que photographe. Pendant la majeure partie de sa vie, il a gardé sa pratique photographique non seulement privée, mais aussi largement isolée du reste du monde. Lors d'une interview en 2019, il a affirmé, malgré l'histoire bien connue de sa correspondance d'enfance avec une actrice hollywoodienne et les preuves visuelles évidentes de ses premiers clichés en noir et blanc, n'avoir jamais été influencé par le cinéma. (Il a également nié avoir entendu parler de Cindy Sherman, bien qu'il ait si prodigieusement anticipé sa démarche). Ses photographies couleur ultérieures sont encore plus difficiles à cerner. Les costumes sont très évocateurs mais difficiles à situer temporellement ou géographiquement, et ses personnages réagissent souvent intensément à quelque chose qui se trouve juste en dehors du cadre.

Si l'on prend Machciński au mot dans l'interview, où il raconte en riant comment il endurait les coups à l'orphelinat, grimpait aux arbres dans le parc pour chanter comme un oiseau, et n'était jamais, malgré les obstacles souvent brutaux de son enfance, véritablement malheureux, on pourrait même supposer qu'il avait du mal à distinguer le fantasme de la réalité. Son sourire, notamment dans les dernières années, présente parfois une spontanéité qui semble presque dérangée, et l'on pourrait aisément imaginer l'histoire d'un

homme sublimant son exhibitionnisme, ses troubles de genre et d'autres impulsions dangereuses dans l'exutoire le plus inoffensif à sa portée.

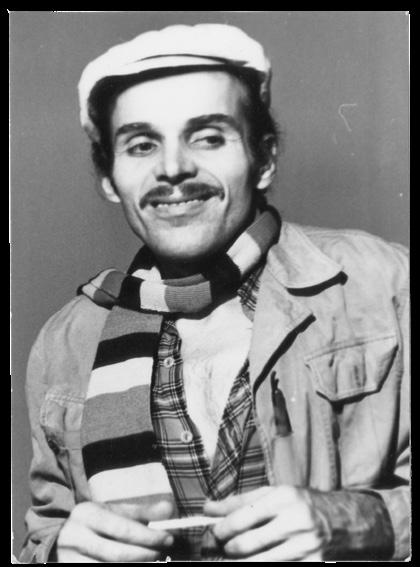

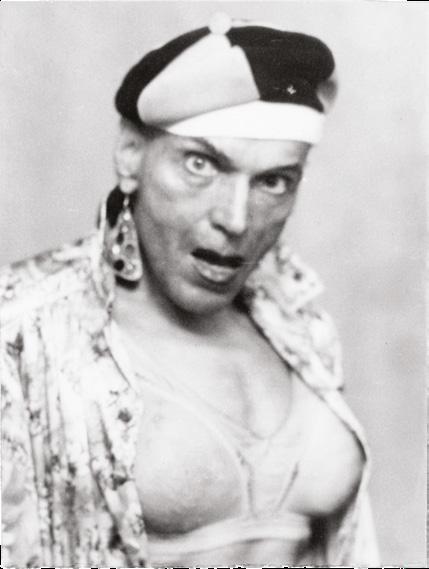

Cependant, toute interprétation de ce genre se heurte au contrôle absolu que Machciński exerçait sur son instrument. Il pouvait faire de son visage ce qu'il voulait. Comparez une photographie en noir et blanc de lui coiffé d'une casquette de camelot et d'une écharpe rayée, sa chemise ouverte jusqu'au sternum, avec une photo en couleur où il porte du maquillage, du rouge à lèvres, un chapeau ressemblant à un bonnet de douche et un maillot bleu marine. Dans la première, les mains de l'artiste serrent nerveusement une cigarette roulée, et son regard ainsi que son sourire sont étroits et horizontaux.

Il ressemble à un homme qui surcompense son malaise face à la masculinité conventionnelle tout en espérant séduire une femme. Dans l'autre photographie, inclinant légèrement la tête d’un côté, un froncement de sourcils affichant une tristesse feinte comme s'il réagissait à une mauvaise nouvelle, ses lèvres sont audacieuses et ses yeux immenses. Il a l'air d'une grande beauté consciente de son pouvoir et prête à l'exploiter.

Considérez une autre image, où Machciński tend tristement une grande fleur blanche. Cette fois, son regard trahit la mélancolie lucide d'un bouffon de cour aguerri, conscient de l'effet que produira sa moue, et qui la "signifie" comme on "signifie" un choix artistique –avec intention et distance critique. Coiffé d’un grand chapeau noir et arborant des

boucles d’oreilles lavande, derrière un bouquet de plumes blanches, il est, au contraire, totalement absorbé par l’instant. En cowboy, parfois – quand il semble sentir quelque chose de désagréable ou qu’il allume une cigarette faite d’un billet de cent dollars – on soupçonne qu’il doit plaisanter. Sous d'autres traits, comme celui de la garçonne avec un élégant fume-cigarette, il garde la blague pour lui.

La variété de ses poses est aussi étonnante que son contrôle. L'inventivité et l’ingéniosité de ses costumes sont impressionnantes en elles-mêmes, d'autant plus qu'il les confectionnait avec des moyens minimalistes et bon marché. Mais la gamme d'expressions de son visage semble infiniment nuancée et infiniment vaste, capable à la fois de voyager n’importe où et de moduler des teintes d'émotion si fines qu'elles pourraient tenir sur la tête

d'une épingle. En même temps, plus on les observe, plus elles deviennent abstraites. Ce n’est pas seulement que son séducteur en casquette de camelot ou sa beauté en maillot de bain ne sont ni nommés ni identifiés ; c’est qu’il n’y a finalement rien d'autre à ces personnages qu'un pur instant émotionnel, illimité, déraciné, infini. En réalité, c'était là sa grande source d'inspiration en tant qu'artiste. En plaçant son œuvre au cœur même de l'identité, dans ce lieu purement subjectif et intérieur d'où jaillissent les émotions, Machciński devançait les distinctions entre réalité et fantasme, signification et intention, implications et conséquences, faits et symboles, innocence et âge adulte, temps et lieu. Tout ce qui se passe en cet endroit est vrai, selon ses propres termes, aussi longtemps que cela dure. Dans la "vraie vie", Tomasz Machciński aura peut-être été un mécanicien de précision qui a passé sa vie à Kalisz, en Pologne, avant de mourir en 2022. Mais en vérité, il fut acteur, poète, pirate, sénateur romain, culturiste huilé et ingénue coquette.

« En cowboy, parfois – quand il semble sentir quelque chose de désagréable ou qu’il allume une cigarette faite d’un billet de cent dollars – on soupçonne qu’il doit plaisanter. »

Excerpts from the film Incognito, directed by Henryk Dederko, 1988. In this sequence, Tomasz Machciński imagines himself coming to welcome Joan Tompkins, who informs him at the last moment that she will not come, as the journey is too expensive.

Extraits du film Incognito, réalisé par Henryk Dederko, 1988. Dans cette séquence, Tomasz Machciński imagine qu'il vient accueillir Joan Tompkins, qui l'avise au dernier moment qu'elle ne viendra pas car le voyage est trop cher.

Marc Donnadieu, né en 1960 à Jerada (Maroc), est chercheur, enseignant, critique d’art et commissaire d’exposition indépendant basé à Paris. Il a été conservateur en chef de Photo Élysée (Musée cantonal pour la photographie, Lausanne, Suisse) de 2017 à 2023, après avoir été conservateur en charge de l’art contemporain au LaM Musée d’art moderne, d’art contemporain et d’art brut de Lille Métropole de 2010 à 2017, et directeur du Fonds régional d’art contemporain de Haute-Normandie de 1999 à 2010.

Il a été commissaire ou co-commissaire d’expositions monographiques ou thématiques de référence consacrées à la photographie contemporaine, aux représentations actuelles du corps, aux processus identitaires au sein des espaces sociaux d’aujourd’hui, au champ pictural, aux pratiques du dessin, aux relations entre art et architecture, ainsi qu’aux rapports entre art brut et photographie. Membre de l’Association internationale des critiques d’art (AICA) depuis 1997, il a collaboré à de très nombreuses revues étrangères et françaises, dont Art Press et The Art Newspaper. Il a également participé à plusieurs dizaines de catalogues et d’ouvrages monographiques ou thémat iques dans les domaines des beaux-arts, de la photographie, de l’architecture, du design ou de la mode. Compagnon de la galerie christian berst art brut depuis de nombreuses années, il a réalisé l’exposition « Comme je me voudrais “être” » au bridge by christian berst en février-mars 2024. Il a également préfacé le catalogue de l’exposition « le fétichiste. Anatomie d’une mythologie » présentée à la galerie en octobre-novembre 2020.

« Puisque ces mystères me dépassent, feignons d’en être l’organisateur1. »

Jean Cocteau, Les Mariés de la Tour Eiffel

Tomasz Machciński n’existe pas. Pourtant, Tomasz Machciński a bien existé et existe toujours. Ou, plutôt, en inversant une formule devenue si célèbre qu’elle en devient adage populaire : Tomasz Machciński est né Tomasz Machciński, mais est devenu, par un effet du hasard ou de la destinée, un ailleurs et un autrement pluriels et insaisissables. Selon Virgile, aux vers 433 à 462 de L’Énéide, la Sybille de Cumes écrivait ses oracles sur des feuilles de chêne qu’elle disposait à l’entrée de sa tanière. Mais, en ouvrant la porte, chaque personne qui y entrait faisait s’envoler le tas de feuilles, si bien qu’il ne savait plus sur quelle feuille emportée par le vent était écrit son futur, son destin, ou l’énigme qu’il devait déchiffrer. Si certains seraient immédiatement partis à la recherche de « leur » feuille, Tomasz Machciński les prend toutes, et les

incarne les unes après les autres avec une désinvolture mâtinée d’indiscipline. Aussi tous les destins disponibles dans le courant de l’histoire et du monde deviennent-ils son propre destin, chacun étant l’un de ses destins possibles.

Plus précisément, Tomasz Machciński a cessé d’être l’orphelin de guerre qu’il était2 lorsqu’il a reçu un autographe sibyllin de la star hollywoodienne Joan Tompkins, qui sous-entendait qu’elle souhaitait devenir sa mère adoptive : « Avec amour à "Tommy" de "mère" Joan ». Pour le jeune Tomasz, il ne pouvait s’agir, à le lire, que de l’aveu de l’actrice d’être sa mère véritable : une étoile américaine dans le ciel de sa vie lui a soudain (re)donné vie. De cette confusion renversante entre le devenir et l’être, le probable et le certain, sont nés dans le secret près de 22 000 autoportraits

1. Jean

2. Sa mère est décédée d’une tuberculose alors qu’il avait deux ans, et son père est mort dans un camp de concentration nazi.

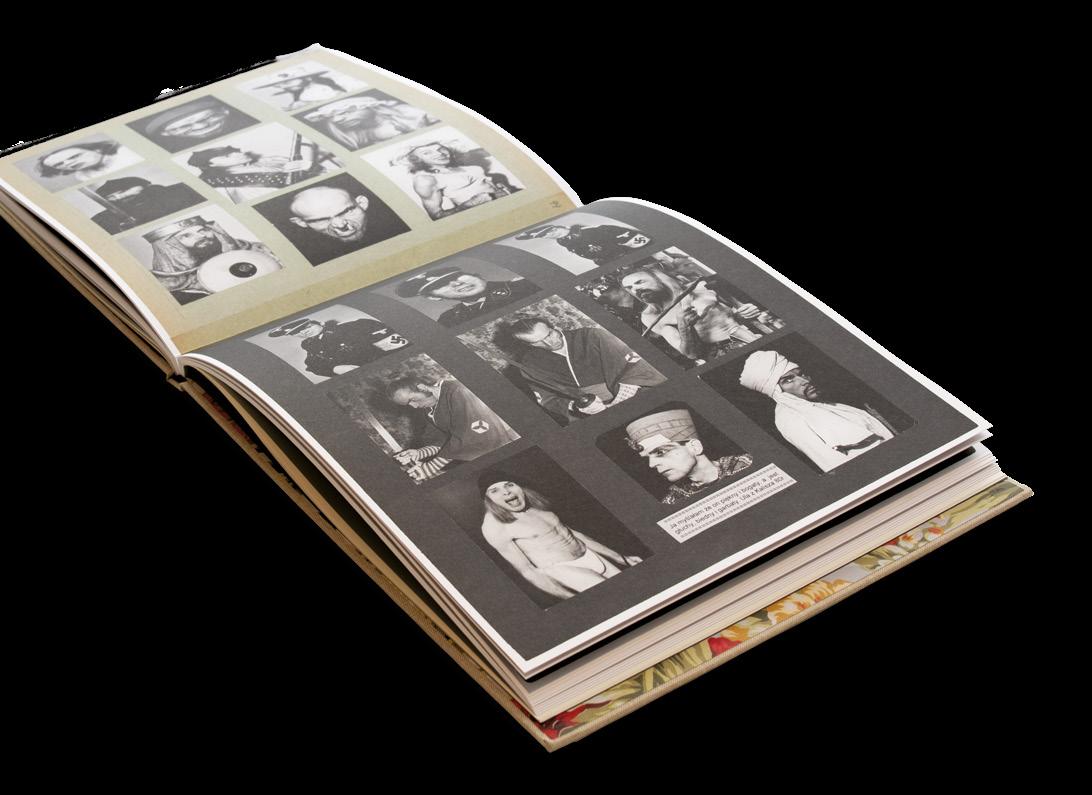

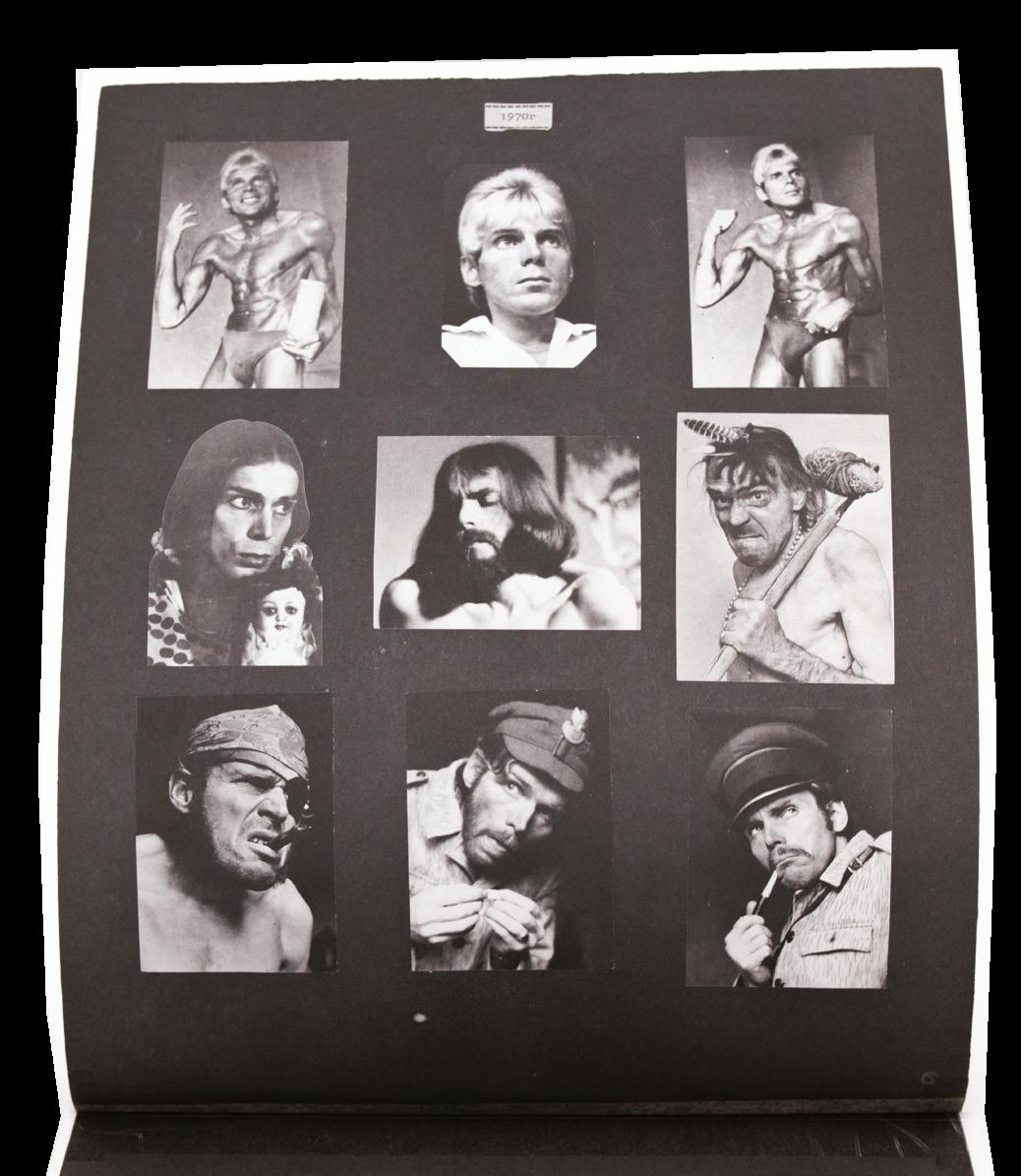

fac-simile de l'album de tomasz machciński.

photographiques3 ou cinématographiques4, dévoilés depuis peu. Un album publié en fac-similé en 2020 par la Fondation Tomasz Machciński, réunissant son propre choix de 407 portraits réalisés sur plus de 50 années de pratique continue5, en témoigne.

Il est vrai que l’histoire de l’art abonde de semblables projets d’identités multiples : des mises en scène de la Comtesse de Castiglione devant l’objectif de Pierre-Louis Pierson (1856-1867 et 18931895), véritable actrice de ses (auto) représentations, à Pierre Molinier et ses travestissements, en particulier en la poupée qui l’accompagne dans tous les sens du terme, en passant par Aloïse Corbaz et l’opéra infini de ses amours projetés avec l’empereur Guillaume II, sans oublier, bien évidemment, Claude Cahun, Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol, Michel Journiac ou Cindy Sherman6… Et ceuxci n’appartiennent vraiment ni au seul champ de l’art brut, ni au seul champ de la photographique, ni au seul champ de l’art contemporain, ni au seul champ de l’art tout court. Cependant, tout l’œuvre de Tomasz Machciński, du fait de son ampleur et sa démesure, sa constance et

sa détermination, en est l’une des formes les plus abouties et les plus bouleversantes.

Car il ne s’agit pas simplement ici, face à l’objectif, de changer tour à tour d’identité, ou d’emprunter des identités autres, que de (re)trouver en soi toutes les identités que l’on pourrait être ou dans lesquelles on pourrait « faire sa vie » comme on dit « faire sa demeure », forme inédite de bernardl’hermitisme existentiel. Aussi les 22 000 Tomasz Machciński qui ont été répertoriés sont-ils voués à quitter la scène du moi sitôt présentés et représentés7, comme si chacun d’entre eux, à peine paru, n’importait même plus à leur auteur, ne comptait même plus, ou presque, pour lui – le phénix ici s’auto-consume pour mieux renaître perpétuellement de ses cendres.

Dans son illustre essai « La Mort de l’auteur », Roland Barthes soutenait qu’un texte n’appartenait pas à son auteur même, mais qu’il était réécrit à chaque lecture8, et qu’il subsistait donc en permanence dans un état latent, prêt à n’importe quelle interprétation du lecteur. Avec Tomasz Machciński, c’est l’être lui-même qui n’existe que par la mort de son origine ou de son état, afin de devenir – de se révéler

3. D’abord réalisés avec un appareil soviétique Smena, qu’on lui a offert en échange de la réparation d’une montre.

4. À partir d’un appareil photographique numérique.

5. Entre 1966 et 2021.

6. « Je suppose que c’est devenu intéressant pour moi de me choisir dans un groupe de personnes », Cindy Sherman dans Madame Figaro, 2020.

7. « Plus que de m’identifier ou de me révéler dans mes photographies, je tente de m’effacer », ibid.

8. « La naissance du lecteur doit se payer de la mort de l’auteur », Roland Barthes dans « The Death of the Author », Aspen Magazine, n° 5/6, 1967.

6. À partir d’un appareil photographique numérique.

presque, à l’instar d’une photographie – une polyphonie de possibles présents et à venir auxquels nous, spectateurs, accordons ensuite crédit. Et la vie n’a de sens que par le crédit que l’on veut bien lui ou leur accorder. Aussi ne chercherons-nous même plus à distinguer ici un sexe biologique et un sexe de genre, une identité de naissance et une identité choisie, voire deux états paradoxaux de transgenrité identitaire, mais à rester simplement et seulement le spectateur ébloui d’un processus insensé de (ré)incarnation continue et protéiforme, presque généalogiquement rhyzomatique, où le(s) moi(s) se matérialise(nt) à chaque apparition selon une figure rêvée et désirée par l’auteur : « Tout ce dont je rêve, je l’ai photographié. Ce sont des photographies de mes rêves, de mes désirs, de mes objectifs, comme de l’inatteignable9. »

La photographie en est donc l’inscription et l’expression, vérifiables et tangibles : ce Tomasz Machciński que nous voyons aujourd’hui à l’image – tout comme tous les autres passés ou futurs – a bien existé à un moment donné du temps et de la vie. ça a été là10 preuve nous en est donnée.

Pour autant, et son propre album en témoigne, il ne s’agit pas d’un atlas construit et organisé, d’une encyclopédie définitive de personnages réels ou

fictionnels, d’un inventaire exhaustif d’identités endossées, d’une somme monumentale sur le travestissement, mais d’une simple et seule suite d’entrevues, de trouvailles et de retrouvailles au gré du vent, d’interprétations éparpillées, temporaires, transitoires et nomades, voire de confusions dérégulées du genre11. Une fugue identitaire, au sens musical comme au sens premier. Un déport autant qu’un départ permanent pour un voyage intérieur 22 000 fois réitéré durant lequel il se découvre autant qu’il se recouvre. Et considérer Tomasz Machciński comme un simple performer amoindrirait la force tentaculaire de ce projet où, seul dans sa chambre d’écho photographique, c’est surtout avec lui-même et ces autres en lui qu’il entretient ce dialogue infini : « Je crée des autoportraits depuis 1966. Je n’utilise pas de postiches, ni d’astuces, mais j’utilise tout ce qui se passe dans mon corps : repousse des cheveux, perte de dents, maladies, vieillissement, etc. » Pour un enfant dont on avait prédit qu’il allait comme sa mère mourir de tuberculose (sa mère biologique ayant été (re)trouvée), il fallait donc se réécrire lui-même, se réinterpréter, se repeupler et se retisser à partir de tous ces autres avec lesquels il se relie et se délie. Car c’est bien de cela dont il s’agit à chaque occurrence : plier, déplier

10. Voir à ce propos Roland Barthes, La Chambre claire : Notes sur la photographie, Paris, Gallimard, 1980.

11. « Il s’agit en réalité d’une façon de me dématérialiser pour exister au sein de ces personnages », Cindy Sherman dans Madame Figaro, 2020.

et replier une naissance d’une (petite) mort, une retrouvaille d’un abandon, une famille d’une solitude, afin de ne plus jamais retomber dans l’avant : l’indicible, le nonnommé, le non-statué, l’informulé presque, sinon le degré zéro de l’existence.

Dans l’un de ses livres d’artiste intitulé justement Fugue, Louise Bourgeois – certainement l’une des plus grandes Sybilles de l’art – a écrit successivement : « toi », « eux », « elles »12. Si le passage de l’individuel au collectif à travers le « toi » et le « eux » peut sembler limpide, celui du « eux » aux « elles » est plus complexe et engageant. « Elles », cela pourrait être toutes ces femmes qui ne sont pas contenues dans le « eux », mais également toutes celles qui y sont contenues sans vraiment l’être en propre, à part entière. Il en est de même des identités de Tomasz Machciński : il y a « lui » ; il y a tous ces « eux » à l’extérieur et à l’intérieur de lui-même ; et il y a toutes ces « elles », ces identités qu’il développe, qu’il révèle et qu’il fixe pour l’éternité afin de mieux les rajouter aux « eux », ou pour mieux souligner leur existence invisible parmi les « eux » précédents. « Elles » c’est également, au sein de ce « nous tous » qui nous rassemble, ces « nous-moi » avec lesquels Tomasz Machciński s’assemble13.

« Elles » sont donc ces identités auxquelles il se rattache et s’attache, mais pour mieux ensuite les détacher, les effeuiller et les laisser fuir dans le souffle de l’histoire et du monde, afin que nous les attrapions aujourd’hui comme autant de fragments de discours de vie, comme autant de formes envisageables de futur ou de destination. Comme si rien, autre que la fin de l’existence elle-même, ne devait avoir de fin.

12. Louise Bourgeois, Fugue, New York, Procuniar Workshop, 2005, série de 19 dessins originaux réalisé en 2003, publiée sous la forme d'un portfolio composé de 19 planches, dont 17 sérographies et lithographies et 2 lithographies, édité à 9 exemplaires.

13. On pourra trouver une même nuance de signification dans la formule Us, We, Them utilisée par l'artiste Tavares Strachan en 2015.

Toutes les œuvres couleurs ci-après sont des photographies numériques, sans titre, tirages uniques sur papier brillant Fuji.

Toutes les œuvres noir et blanc ci-après sont des photographies argentiques, sans titre, tirages uniques d'époque par l'artiste sur papier baryté.

All the color works below are untitled digital photographs, single print on glossy Fuji paper.

All the black and white works below are untitled analog photographs, vintage single prints by the artist on baryta paper.

Selon la volonté de l'artiste et en accord avec la Fondation Tomasz Machciński, seules 2 500 photographies issues de la succession sont accessibles à la vente. Il s'agit, dans tous les cas, de tirages uniques.

According to the artist's wishes and in agreement with the Tomasz Machciński Foundation, only 2,500 photographs from the estate are available for sale. In every instance, these are unique prints.

2014, 38 x 29 cm

2010, 38 x 25,4 cm

Independent Art Fair, NYC, 2024

christian berst art brut in collaboration with ricco/maresca gallery

2009, 38 x 28,8 cm

Les photos de films qu'il a conservées de Joan Tompkins ont été une source d'inspiration évidente, de même que d'autres stars de cinéma célèbres, telles que Humphrey Bogart, Liza Minnelli et sa préférée, Marlene Dietrich.

The film stills that he kept from Joan Tompkins were an obvious inspiration, as well as other famous movie stars, such as Humphrey Bogart, Liza Minnelli and his most beloved one - Marlene Dietrich.

2002, 12,6 x 11 cm

2013, 38 x 26 cm 2012, 38 x 26,3 cm

2013, 38 x 27,9 cm

l'un de ses premiers autoportraits "selfies" one of his first self-portrait, selfies, 1966

"En 1966, j'ai reçu un appareil photo Smiena pour avoir réparé une montre, et j'ai appris à prendre des photos. Je posais ma chaussure sur le rebord de la fenêtre, le Smiena était coincé verticalement à l'intérieur de la chaussure - c'était mon trépied.

Il fallait encore que j'achète de la pellicule et que je la développe. Au début, j'ai incarné le vieil homme avec qui je vivais à Kalisz (...) dans une pièce terriblement poussiéreuse. Le lustre était fait de papier journal. J'enfilais un chapeau noir, levais mon appareil bien haut, pointais l'objectif vers mon visage, et je ralentissais l'obturateur.

Une magnifique photo en est sortie. Aujourd'hui, on appelle ça un selfie.

In 1966, I got a Smiena camera for repairing a watch and learned to take photos. I would put my shoe on the windowsill, the Smiena was pressed vertically inside the shoe - that was my tripod. I still had to buy film for something and then develop it. In the beginning, I incarnated the old man I lived with here in Kalisz (...) in a terribly dusty room. The chandelier was made of newspaper.

I put on a black hat, raised my camera high, pointed the lens at my face, slowed down the shutter. A beautiful photo came out.

Today they call it a selfie.

extrait de l'interview avec katarzyna biełas, 2019.

Ce qui compte le plus, c'est l'impression que dégage le personnage, sa personnalité, sa psyché. Qui il est, à quoi il pense, ce qu’il faisait autrefois, que ce soit bon ou mauvais, rusé, toutes les nuances de son esprit. J'observe les gens ; pour moi, un visage humain est comme un paysage pour un peintre.

The most important thing is the impression the character makes, his personality, his psyche. Who she is, what she thinks about, what she used to do, whether it was something good or bad, sly, all the nuances of the psyche. I watch people, for me a human face is like a landscape for a painter.

extrait de l'interview avec katarzyna biełas, 2019.

9 x 87 cm

22,2 x 16,2 cm

Paris Photo, Paris, 2021

2015, 38 x 26,4 cm

Si besoin, vous vous faîtes pousser une moustache ou une barbe, les cheveux longs. Ne serait-ce pas plus facile de les coller ?

Alors il n'y aurait pas de vérité, seulement un masque. Je fais tout sans artifices, sans retouches. J'utilise ce qui arrive à mon corps : la repousse des cheveux, la maladie. Je peux colorer mon corps, élargir mon visage en mettant des boules de pain dans ma bouche ou du coton dans mon nez, mais c'est toujours un corps vivant, on peut me griffer n'importe où et je le sens. Parfois, je n'ai qu'à me coller des cils quand je représente une femme, mais c'est rare. Je fais des seins avec des pommes ou des oranges, puis je les mange. La règle, c'est minimum d’accessoires, maximum de corps.

You grow, if necessary, a moustache, a beard, long hair. Isn't it easier to glue it on?

Then there would be no truth, there would only be a mask. I do everything without tricks, retouches. I use what happens to my body: hair regrowth, illness. I can colour my body, widen my face by putting bread balls in my mouth or cotton wool in my nose, but it's still a living body, you can scratch me anywhere and I feel it. Sometimes I only have to stick my eyelashes on when I do a woman, but rarely. I make breasts out of apples or oranges, then eat them. The rule is minimum prop, maximum body.

extrait de l'interview avec katarzyna biełas, 2019.

2012, 38 x 24 cm

fac-simile de l'album de tomasz machciński.

22 x 16 cm

23 x 16 cm

2005, 15 x 10 cm

2013, 38 x 23,8 cm

2014, 38 x 23,8 cm 2014, 37,8 x 22,8 cm

2014, 38 x 26,9 cm

Je suis mon propre coiffeur. Je dois admettre que c'est plus difficile avec les femmes, mais elles me fascinent.

I am my own hairdresser. I admit that the most difficult thing is with women, but I am fascinated by them.

extrait de l'interview avec katarzyna biełas, 2019.

12 x 9 cm

Je crois qu'instinctivement, je voulais montrer que je n'étais pas ce que j'avais l'air d'être : petit, maigre, bossu...

I think I instinctively wanted to show that I wasn't what I looked like : small, skinny, hunchbacked...

extrait de l'interview avec katarzyna biełas, 2019.

1995, 7 x 5 cm

2017, 38 x 26 cm

2000, 16 x 12 cm

2012, 38 x 27,9 cm

13 x 9 cm

Les rencontres de la photographie d'Arles, France, 2021

2017, 38 x 28 cm

2017, 38 x 27,5 cm

2011, 38 x 29 cm

fac-simile de l'album de tomasz machciński.

1969, 11 x 9 cm

1970, 12,8 x 10,5 cm

foreword

christian berst

The American dream belongs to a Polish mechanic, born in 1942 near Warsaw, a war orphan suffering from bone tuberculosis. His fate takes a turn when, at the age of three, as part of a “long-distance adoption” program, he receives a note from Hollywood actress Joan Tompkins, with the message, “With love, to Tommy, from ‘Mommy’ Joan.”

For nearly twenty years, young Tomasz Machciński grows up with the conviction that she is truly his mother. When the harsh reality catches up with him, he embarks on a desperate quest for identity through thousands of photographic selfportraits, spanning more than half a century.

It is as if, from 1966 onward ten years before Cindy Sherman — Tomasz wanted to play every role, both male and female, indiscriminately. While it is true that Sherman’s and Machciński’s images formally resonate with each other both engaging with the realm of unconventional self-portraiture some fundamental antinomies emerge. First, because Sherman deliberately places herself in the realm of conceptual art, resolutely aiming her work at others, whereas Machciński, deprived of an identity he had long believed to be his, seems to be multiplying combinations to find his own.

In short, even if both artists similarly engage with iconic figures and their photographs draw from popular aesthetics those of cinema, historical figures, or advertising Sherman deconstructs these collective codes, while Machciński uses them for his own reconstruction.

One holds a mirror up to society, bearing witness to it, while the other looks behind that mirror to discover what lies within himself. She says, " Look at yourselves, " he says, “ Look at me. ” Both draw from their own images to reveal both hubris and psyche. Joan Tompkins, in the twilight of her life, would end up being proud to have inspired this great work, while Tomasz, conversely, claimed sole authorship of his creations until his death in 2022.

“ In truth, you could wear no better mask, my contemporaries, than your own face ! ” F. Nietzsche

In 2018, the Tomasz Machciński Foundation was created, and in 2019, his work was presented at the Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie d'Arles in the exhibition Photo | Brut. Acclaimed in 2021 at Paris Photo, his presentation at the Independent Art Fair in 2024 will lead the New York Times to say that “the fair's most memorable event will be the American debut of Polish photographer Tomasz Machciński”.

tomasz

machciński : american dream

I made it all because of you

zofia płoska-czartoryska & katarzyna karwańska

In the classic Hollywood movie “Anastasia” from 1956, Ingrid Bergman plays the orphaned amnesiac girl who comes to believe she is a survivor of the Romanov dynasty - the Grand Duchess Anastasia. In the Paris of 1920’s, Russian post-revolution exiles look for an opportunity to seize her fortune and take advantage of the opportunity to train this young woman of extreme physical likeness to act as a princess. She herself seems to regain her memory and play the role well, leaving the audience in doubt about her true identity. Even The Dowager Empress Maria Fedorovna, Anastasia’s grandmother, recognizes her as such. Yet in the final sequence, she decides to give up the past and run away with a man she loves, deciding to be yet someone else.

Few years before Bergman’s Oscar-winning performance of identity-baffled Anastasia caused a sensation among the cinema lovers worldwide, the aspiring American actress Joan Tompkins approached the Foster Parents Plan charity in New York which ran a distant adoption scheme for children orphaned during WWII in Europe. In the catalog she saw a photograph of a bedridden boy called Tomasz Machciński from Poland, and decided to engage in relationship which

for most part encompassed the exchange of letters and sending minor gifts (she was instructed not to spoil him as “they always start wanting to come to America, and we have to discourage that”). 1

When Machciński got his first letter signed “Love to Tomasz from Mother Jennie”, he was three years old. For the next years that he spent in hospitals, orphanages and special schools, he believed Joan Tompkins was his real mother. Few times a year she would send him the film stills of her new productions and report on her career developments and relocation to Hollywood. When their correspondence stopped for some years due to the McCarthy era of suspicion towards any ties with the Eastern Bloc, Tomasz started to look for her and other relatives via the Red Cross and learned about the true fate of his parents - father was murdered by the Nazis and mother died of tuberculosis soon after his birth. His identity crisis at the threshold of adulthood was deepened by the fact that he was granted the official status of a disabled citizen - the stigma he found utterly unfit to describe who he truly felt. He felt special.

He settled in the town of Kalisz and started a job as a mechanic of bureau equipment. In 1966 he started his solitary, life-long art project that spans 22,000 photographic self-portraits in which he impersonated celebrities, famous figures from history, fictional characters and human types of all genders, ethnicities, social classes, ethics and styles. Learning that he built his own identity on the fantasy, he was free to engage

in the tireless work of self-fiction or - as Susan Sontag would put it - “self-adoration”.2 Working only with poor materials available to him in the Polish provincial town, in his art he acted as the most extravagant dandy.

In many of his early pictures he impersonates Hollywood archetypes like cowboys, femme fatales, screen lovers or athletesthe incarnations that allowed him to look attractive, beyond the physical limitations of his body. The film stills that he kept on receiving from Joan Tompkins were an obvious influence, as much as the famous stars of the screen, including Humphrey Bogart, Liza Minnelli and his most beloved one - Marlene Dietrich. He examined thoroughly cliches about gender and social roles by pushing the stereotypical features to extreme, proving that his approach to American pop culture was never one of pure adoration or mere mimesis. Soon he became interested in a much more fluid view on human identity and its relation to appearance. He started to pose as bold androgynous or interesexual figures or expose his deformed body, always trying to reach for more ambiguity and excess (with the absolute freedom reached in his digital colorful photographs from the final years of his life).

“The hallmark of Camp is the spirit of extravagance. Camp is a woman walking around in a dress made of three million feathers. Camp is the paintings of Carlo Crivelli, with their real jewels and trompel'œil insects and cracks in the masonry. Camp is the outrageous aestheticism of Sternberg's six American movies with

Dietrich”- wrote Sontag in her famous Notes on Camp, published in New York at the same time Machciński started to take his pictures. “Camp sees everything in quotation marks. It's not a lamp, but a "lamp"; not a woman, but a "woman." To perceive Camp in objects and persons is to understand Being-asPlaying-a-Role. It is the farthest extension, in sensibility, of the metaphor of life as theater.” These remarks are surprisingly fitting to Machciński’s art strategy, which nevertheless flourished independently, in completely different geopolitical and personal circumstances, incorporating many other cultural influences, which resulted in one of the most original total art projects in the history of photography.

In the public defense of the Jack Smiths’ censored experimental film “Flaming creatures” (1964) - a classic example of camp, Sontag praises its crude execution and free orgy of indeterminate sexuality and imagination from corny movies and mass culture. Disappointed with the New York critics and art circles, she claims: “This kind of art has still to be understood in this country”3. Could this kind of transgression of social norms and challenge to the “good taste” be understood in the provincial town in communist Poland? Especially if executed by an amateur, without the backing of art theory and subcultural ties ? Machciński - whose work as much as Smiths’ explored “the dead ends of the self”though from an entirely different existential perspective - had to wait more than half a century to be first noticed by the art world as a pioneer of the performative turn.

2. Susan Sontag, Notes on Camp, 1966, access: https://monoskop.org/images/5/59/Sontag_Susan_1964_Notes_ on_Camp.pdf

3. Susan Sontag, Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures, The Nation, 1964, access: https://thenation.s3.amazonaws. com/pdf/feast1964.pdf

In 1991 Joan Tompkns wrote a fictionalized book Tomek' about their unusual long distance relationship that lasted through decades. “This is a true story” - claimed the movie industry veteran. Yet surprisingly she gave it a fictitious, “American Dream” sort of a narrative conclusion. In the final chapters she decides to bring Tomek to the supposed land land of his dreams - America, where he will finally get a show. “You have been Somebody to me for over forty years. Now, I have a prayer that you be Somebody in America”4 - she writes to him in the imperialistically flavored letter of invitation. The soppy style of her version of the story is not surprisingafter all she starred in melodramatic movies as a supporting actress for most of her life. The whole book is a self-portrait as an affectionate and altruistic mother from a better world to the miserable orphan from behind an Iron Curtain - a piece of self-fiction and self-adoration on its own.

Tomasz and Joan did meet in Los Angeles a few years later at the initiative of the Polish filmmaker Alicja Albrecht who shot a documentary “Child from a Catalog” about him. In one of the scenes “mother Jennie” took him to Disneyland and in another Tomasz, walking the Hollywood Walk of Fame, signed the waiting empty star on his own - the way he acted all of his life. Their grand life-time fictions of true love, fame and splendor of American life arrived at the final reality-check.

“She wasn’t Anastasia after all” says the dumped prince of Denmark after the character played by Bergman runs away. The old Empress famously replies: “Wasn’t she?”. And she adds: “The play is over. Go home”.

4.

Zofia Płoska-Czartoryska is a Warsawbased independent curator, author, and cultural manager. She graduated from Maastricht University and the University of Warsaw. In the past, she has been associated with the Marian Goodman Gallery in New York, the 2nd Programme of the Polish Radio, and the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, where she held the position of curator and chief international project manager, leading major activities of the L'Internationale Confederation of European progressive museums. She co-curated with Katarzyna Karwańska the exhibitions "Why We Have Wars: The Art of Contemporary Outsiders" (Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, 2016), "Paweł Althamer: The Burghers of Bródno" (Bródno Sculpture Park, 2016), "I Am No Longer a Dog" (Silesian Museum in Katowice, 2017), "With Love to Tommy" (Tomasz Machciński Foundation, 2019), and "Polska/Ziętek : The Gymnast" (Dzielna Foundation, 2023). She is the author of numerous academic and popular publications on contemporary and outsider art and serves as an art columnist for Magazyn Pismo, often referred to as the Polish New Yorker. The accolades for her work include the Dutch Government Huygens Scholarship and the Prize of the Gessel Foundation for Zachęta.

Katarzyna Karwańska - curator, producer, and founder of the Tomasz Machciński Foundation. Since 2008, she has been professionally associated with the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, where she is responsible for the development of film archives of amateur creativity (Amateur Film Clubs and the Polish Archive of Home Movies). Her main area of research is the work of engaged outsider artists who operate independently of the professional art world, as well as amateur and anonymous creativity. From 2020 to 2021, she ran the home gallery Incognito on Bagatela Street in Warsaw. Between 2009 and 2017, she collaborated with artist Paweł Althamer on the public project Park Rzeźby na Bródnie (Bródno Sculpture Park).

Among the exhibitions curated by Karwańska are: "Atomic Love Story" at Fundacja Dzielna in Warsaw (2022); "You’ve Gone Incognito. Cross-dressing and Home Photo Sessions" at the Fort Institute of Photography in Warsaw (2021); "Different Faces, Different Places": a solo exhibition of Tomasz Machciński at the Manggha Museum of Japanese Art and Technology in Krakow (2021); "Magda": a solo exhibition of Zbigniew Libera at the Incognito Gallery in Warsaw (2020); "With Love to Tommy" (co-curated with Zofia Czartoryska), Warsaw Gallery Weekend (2019); "House of Colonels. Girl and Gun" in Fuerteventura (2018); "I'm no longer a dog" (co-curated with Zofia Czartoryska), Silesian Museum in Katowice (2017); "Why We Have Wars. The Art of Contemporary Outsiders" (co-curated with Zofia Czartoryska), Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (2016).

an actor, a poet, and a pirate will heinrich

Tomasz Machciński was an actor, a poet, a pirate, a mystic. He was a Roman senator, a seedy rock-and-roller, an oiled-up bodybuilder, a coquettish ingenue with apples or oranges for breasts. He was a mischievous child and a world-weary roue. He could be handsome, forgettable, or ugly, as the occasion demanded; grew mustaches and goatees to order; and was always ready to tuck his penis out of sight between his legs. At the beginning of his career, he often became historical figures like Hitler or Gandhi. By the end, he was conjuring less identifiable but no less specific characters and wearing them with a transfixing, magisterial doubleness. Through their fully realized faces, gestures, and costumes, he let his own extraordinary character shine through.

In “real life,” of course, Machciński was a Polish war orphan who had a wife, a son and a diploma in precision mechanics, and his other roles pertained only to the hundreds of elaborate, fictional self-portraits he created as a photographer. For most of his life he kept his photographic practice not only private but largely sealed off from the larger world. In a 2019 interview, he claimed, despite the well-worn story of his childhood correspondence with a Hollywood actress and the obvious visual evidence of his early black and white stills, never to have been influenced by cinema. (He also denied having

heard of Cindy Sherman, despite having so stupendously anticipated her approach.) His later color photographs are even harder to pin down. The costumes are highly evocative but hard to place temporally or geographically, and his characters are often reacting intently to something just out of frame.

Taking the Machciński of the interview at his word, as he describes laughing through beatings at his orphanage, climbing trees in the park to sing like a bird, and never, despite the often brutal obstacles and circumstances of his upbringing, being unhappy, you might even suppose that he was confused about the distinction between fantasy and reality. There can be an unfiltered quality to his smile, particularly later on, that doesn’t feel quite sane, and a very plausible story could be constructed about a man sublimating his exhibitionism, gender confusion, and other dangerous impulses into the most harmless avenue available to him.

Against any such interpretation, however, must be set the total control that Machciński exercised over his instrument. He could make his face do anything. Compare a black and white photograph of him in a newsboy cap and striped scarf, his shirt open to the sternum, with a color picture of him in makeup, lipstick, a hat that looks like a showercap, and a navy blue singlet. In the former, the artist’s hands nervously clutch a roll-your-own cigarette, and his eyes and smile are narrow and horizontal. He looks like a man at once overcompensating for his discomfort with

conventional masculinity and hoping to pick up a girl. In the latter photograph, tipping his head to one side and slightly frowning, as if self-consciously responding to bad news by pretending to be sad, his lips are bold and his eyes enormous. He looks like a great beauty who knows her power and is ready to use it.

Or consider another image, in which Machciński sadly offers a large white flower. This time his eyes telegraph the melancholy self-awareness of a seasoned court jester who knows what his pout will accomplish, and “means” it the way one “means” an artistic choice -- with intention and critical distance. In a big black hat and lavender earrings, behind a clutch of white feathers, on the other hand, he’s totally lost in the moment. As a cowboy, sometimes -- when he seems to be smelling something unpleasant, or is lighting up a cigarette made of a hundred dollar bill -- you suspect he must be joking. In other guises, like the flapper with an elegant cigarette holder, he keeps the joke to himself.

The variety of his poses is no less astonishing than his control. The inventiveness and ingenuity of his costumes is impressive in its own right, particularly since he did it all as minimally and inexpensively as he could. But the expressive range of his face seems infinitely graded and infinitely broad, capable at once of traveling anywhere and of modulating fine shades of feeling that could fit on the head of a pin. At the same time, the more you look at them, the more abstract they become. It’s not only that his lothario in a newsboy cap or beauty in a bathing

suit aren’t named or identified; it’s that there really isn’t anything more to them than one pure, emotional moment, unlimited, unrooted, unending.

In fact, this was his great inspiration as an artist. By locating his work at the very center of selfhood and identity, in the purely subjective, internal place from which emotions spring, Machciński preempted distinctions between reality and fantasy, meaning and intention, implications and consequences, facts and symbols, innocence and adulthood, time and place. Whatever happens in that place is true, on its own terms, for as long as it lasts. In “real life,” Tomasz Machciński may have been a precision mechanic who spent his life in Kalisz, Poland, and died in 2022. In truth, however, he was an actor, a poet, and a pirate, a Roman senator, an oiled-up bodybuilder, a coquettish ingenue.

Will Heinrich was born in New York and spent his early childhood in Japan. He reviews gallery shows, museum exhibitions, and art fairs for the New York Times, as well as writing artist obituaries, and has also written for the New Yorker, the New York Observer, Hyperallergic, Art in America, Jewish Currents and the Nation. His novel The King's Evil, published by Scribner in 2003, won a PEN/Robert Bingham Fellowship in 2004. His most recent novel, The Pearls, was published in 2019 by Elective Affinity.

the sibyl and the phoenix marc donnadieu

"Since these mysteries are beyond me, let us pretend to be their orchestrator.1"

Jean Cocteau, The Eiffel Tower Wedding Party

Tomasz Machciński does not exist. And yet, Tomasz Machciński did exist and still does. Or, rather, to reverse a phrase that has become so famous it has turned into a popular adage: Tomasz Machciński was born Tomasz Machciński, but, through a twist of fate or destiny, he became something plural and elusive, somewhere and somehow else. According to Virgil, in lines 433 to 462 of the Aeneid, the Sibyl of Cumae wrote her oracles on oak leaves, which she placed at the entrance of her cave. Yet, upon opening the door, anyone entering would cause the pile of leaves to scatter, so that no one could know on which wind-blown leaf their future, their fate, or the riddle they were to decipher was inscribed. While some would have immediately set out to find "their" leaf, Tomasz Machciński gathers them all and embodies them one by one, with a nonchalance tinged with insubordination. Thus, all the fates available in the course of history and the world become his own destiny, each one being a possible version of his fate.

More precisely, Tomasz Machciński ceased to be the war orphan he was2 when he received a sibylline autograph from the Hollywood star Joan Tompkins, which implied she wished to become his adoptive mother: "With love to "Tommy" from "Mother" Joan." For the young Tomasz, this could only be, as he read it, a confession from the actress that she was his true mother: an American star in the sky of his life had suddenly given him (a new) life. From this dizzying confusion between becoming and being, the probable and the certain, were born in secrecy nearly 22,000 photographic3 or video4 self-portraits, only recently unveiled. An album published in facsimile in 2020 by the Tomasz Machciński Foundation, containing his own selection of 407 portraits created over 50 years of continuous5 practice, bears witness to this.

It is true that the history of art is replete with similar projects of multiple identities: from the staged self-portraits of the Countess of Castiglione before Pierre-Louis Pierson’s lens (1856–1867 and 1893–1895), where she is the true actress of her (self-) representations, to Pierre Molinier and his transvestism, particularly as the doll who accompanies him in every sense of the word, to Aloïse Corbaz and the endless opera of her imagined love affairs with Emperor Wilhelm II, not to mention, of course, Claude Cahun, Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol, Michel

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Journiac, or Cindy Sherman6… And these artists belong neither strictly to the realm of outsider art, nor solely to the domain of photography, nor merely to contemporary art, nor to art itself in its narrowest definition. However, the entire oeuvre of Tomasz Machciński, by virtue of its scope and excess, its constancy and determination, stands as one of the most accomplished and deeply moving forms of this phenomenon.

For this is not simply, before the camera, a matter of merely changing identities one after another, or borrowing other identities, but rather of (re)discovering within oneself all the identities one might become, or in which one might "make a life," as one might "make a home"—a novel form of existential hermit crab-ism. Thus, the 22,000 Tomasz Machcińskis catalogued are destined to leave the stage of the self as soon as they are presented and represented7, as if each of them, having barely appeared, no longer mattered even to their creator—counted for nothing, or almost nothing, to him. Here, the phoenix self-consumes only to be perpetually reborn from its ashes.

In his famous essay "The Death of the Author," Roland Barthes argued that a text does not belong to its author, but is rewritten with every reading8, and thus it remains in a perpetual state of latency, ready for any reader's interpretation. With Tomasz Machciński, it is the very self that exists only through the death of its origin or state, in order to become — to almost be revealed, like a photograph — a polyphony of possible presents and futures to which we, the spectators, then lend credence. And life has meaning only through the credence we choose to give it or them. Thus, we will no longer seek to distinguish here between biological sex and gender identity, between an identity of birth and a chosen identity, or even between two paradoxical states of transgender identity, but rather to remain simply and solely the dazzled spectator of an insane process of continuous and protean (re)incarnation, almost genealogically rhizomatic, where the self (or selves) materializes with each appearance according to a figure dreamed of and desired by the author: “Everything I dream of, I have photographed.

6. “I guess it became interesting for me to choose myself from a group of people,” Cindy Sherman in Madame Figaro, 2020.

7. “More than identifying or revealing myself in my photographs, I try to erase myself”, ibid.

8. “The birth of the reader must be paid for by the death of the author”, Roland Barthes in ‘The Death of the Author’, Aspen Magazine, n° 5/6, 1967.

These are photographs of my dreams, my desires, my goals, as well as the unattainable.9”

Thus, photography is its inscription and expression, verifiable and tangible: this Tomasz Machciński that we see today in the image — like all the others, past or future — has indeed existed at a given moment in time and life. It was there10; proof is given to us.

However, as his own album attests, this is not a constructed and organized atlas, a definitive encyclopedia of real or fictional characters, an exhaustive inventory of assumed identities, or a monumental treatise on disguise, but rather a simple, singular series of encounters, discoveries, and rediscoveries at the whim of the wind — scattered, temporary, transitory, and nomadic interpretations, or even unregulated confusions of gender11. An identity fugue, in both the musical and literal sense. A displacement as much as a permanent departure on an inner journey repeated 22,000 times, during which he discovers himself as much as he covers himself. To consider Tomasz Machciński as a mere performer would diminish the sprawling power of this project, where, alone in his photographic echo chamber, he engages in an infinite dialogue primarily with himself and the others within him: "I have been creating

self-portraits since 1966. I do not use wigs or tricks, but I use everything that happens in my body: hair regrowth, tooth loss, illness, aging, etc." For a child who was predicted to die of tuberculosis like his mother (his biological mother having been [re]discovered), it was necessary to rewrite himself, reinterpret himself, repopulate and reweave himself with all these others with whom he connects and disconnects. For this is what each occurrence entails: folding, unfolding, and refolding a birth from a (small) death, a reunion from an abandonment, a family from a solitude, so as never to fall back into the before: the unspeakable, the unnamed, the undecided, the almost unformulated, if not the zero degree of existence.

In one of her artist's books aptly titled Fugue, Louise Bourgeois — surely one of the greatest Sibyls of art — wrote in succession: "you," "them," "her12." If the transition from the individual to the collective through "you" and "them" seems clear, the shift from "them" to "her" is more complex and engaging. "Her" could represent all the women who are not contained within "them," but also all those who are contained without truly being so in their own right.

9. Tomasz Machciński, in Album, Warsaw, Tomasz Machciński Foundation, 2020.

10. On this subject, see Roland Barthes, La Chambre claire: Notes sur la photographie, Paris, Gallimard, 1980.

11. “It's really a way of dematerializing myself to exist within these characters”, Cindy Sherman in Madame Figaro, 2020.

12. Louise Bourgeois, Fugue, New York, Procuniar Workshop, 2005, series of 19 original drawings created in 2003, published as a portfolio of 19 plates, including 17 serrographs and lithographs and 2 lithographs, edition of 9.

The same applies to the identities of Tomasz Machciński: there is "him"; there are all those "them" outside and inside himself; and there are all those "hers," those identities that he develops, reveals, and fixes for eternity, so as to better add them to the "them," or to better highlight their invisible existence among the previous "them." "Her" also represents, within the "all of us" that brings us together, those "usme" identities with whom Tomasz Machciński assembles himself13. "Her" is therefore those identities to which he attaches and connects himself, only to better detach them later, to strip them away and let them drift in the breath of history and the world, so that we may catch them today as so many fragments of the discourse of life, as so many conceivable forms of future or destination. As if nothing, except the end of existence itself, should ever have an end.

Marc Donnadieu, born in 1960 in Jerada, Morocco, is a researcher, educator, art critic, and independent exhibition curator based in Paris. From 2017 to 2023, he served as Chief Curator at Photo Élysée (Cantonal Museum of Photography, Lausanne, Switzerland), following his role as Curator of Contemporary Art at the LaM – Lille Métropole Museum of Modern Art, Contemporary Art, and Outsider Art – from 2010 to 2017, and Director of the Fonds Régional d’Art Contemporain in HauteNormandie from 1999 to 2010.

He has curated or co-curated several landmark monographic and thematic exhibitions focused on contemporary photography, current representations of the body, identity processes within today’s social spaces, the field of painting, drawing practices, relationships between art and architecture, as well as the connections between outsider art and photography. A member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA) since 1997, he has contributed to numerous foreign and French publications, including Art Press and The Art Newspaper. He has also participated in dozens of catalogues and monographs on fine arts, photography, architecture, design, and fashion.

A longtime partner of the christian berst art brut gallery, he curated the exhibition “Comme je me voudrais ‘être’” at the bridge by christian berst in February-March 2024. He also wrote the preface to the catalogue for the exhibition “Le fétichiste. Anatomie d’une mythologie,” presented at the gallery in October-November 2020.

13. A similar nuance of meaning can be found in the formula Us, We, Them used by artist Tavares Strachan in 2015.

fondation tomasz machciński

1. tomasz (à gauche / on the left), 1954

2. 3. 4. tomasz machciński, 1963

5. tomasz avec sa femme / with his wife, 1991

6. tomasz avec son fils / with his son, 1991

7. tomasz avec son fils / with his son, 1996

Je suis ravie au-delà des mots de jouer ne serait-ce qu'un infime rôle dans la magnifique comédie, tragédie et histoire que Tomasz Machciński a créées. Il a fait fleurir un jardin remarquable à partir des graines les plus improbables et d'un sol qui aurait été désespérément inadapté pour n'importe qui d'autre."

I'm thrilled beyond words to play even a tiny part in the magnificient comedy, tragedy and history that Tomasz Machcinski has created. He has grown a remarkable garden from the most unpromising seeds ans soil that would have been hopelessly inadequate to anyone else.

Tompkins (c. 1980's)

irena machcińska & alicja albrecht, katarzyna biełas, rafał bujnowski, henryk dederko, paweł machciński, adam mickiewicz institute, polish Institute in paris. & manuel anceau, élisa berst, enki berst, adriana bustamante, juliette daveau, antoine frérot, amanda jamme, indya khayat, carmen et daniel klein, alejandro labrador, guillaume oranger, jeanne rouxhet, zoé zachariasen.

Ce catalogue a été publié à l’occasion de l’exposition "tomasz machciński : american dream. I made it all because of you" à christian berst art brut, du 14 septembre au 10 novembre 2024.

This catalog has been published to mark the exhibition "tomasz machciński : american dream. I made it all because of you" at christian berst art brut, from September 14th to November 10th, 2024.

design graphique et réalisation graphic design and production élisa berst © christian berst art brut, septembre 2024

3-5-6 passage des gravilliers 75003 paris contact@ christianberst.com

Catalogues bilingues publiés par christian berst art brut depuis 2009

Bilingual catalogues published by christian berst art brut since 2009

little venice aloïse corbaz, madge gill, leopold strobl, anna zemánková 78 p., 2024.

les mots pour le dire #1 textes de laurianne melierre, 86 p., 2024.

ken grimes space oddity textes de alejandra russi, 72 p., 2023-2024.

luboš plný body language textes de philippe comar, claire margat et lucie žabokrtská, 98 p., 2023.

sebastián ferreira megalopolis texte de christophe le gac, 87 p., 2023.

joaquim vicens gironella paradis perdu texte de guillaume oranger, 130 p., 2023.

in abstracto #3 texte de raphaël koenig, 130 p., 2023.

hans georgi noah’s plane texte de françois salmeron, 200 p., 2022.

alexandro garcía architectura sagrada cosmica textes de pablo thiago rocca, charles-mayence layet, 198 p., 2022.

james edward deeds the electric pencil #2 texte de philippe piguet, 154 p., 2022.

jesuys crystiano a contrario textes de thilo scheuermann & manuel anceau 180 p., 2022.

do the write thing read between the lines #3 texte de jean-marie gallais, 160 p., 2022.

josef karl rädler la clé des champs textes de céline delavaux & ferdinand altnöder, 150 p., 2022.

les révélateurs débordement #1 textes de anaël pigeat et yvannoé krüger, 200 p., 2020 - 2021.

mary t. smith mississippi shouting #2 textes de daniel soutif et william arnett, 172 p., 2013 - 2021.

julius bockelt ostinato textes de christiane cuticchio et sven fritz, 300 p., 2021.

anna zemánková hortus deliciarum #2 textes de terezie zemánková et manuel anceau, 300 p., 2021.

franco bellucci beau comme... #2 texte de gustavo giacosa, 188 p., 2021.

carlos augusto giraldo codex textes de jaime cerón et manuel anceau, 200 p., 2021.

le fétichiste anatomie d'une mythologie textes de marc donnadieu et magali nachtergael, 250 p., 2020.

zdeněk košek dominus mundi textes de barbara safarova, jaromír typlt, manuel anceau, 250 p., 2020.

in abstracto #2 texte de raphaël koenig, édition bilingue, 264 p., 2020.

albert moser scansions textes de bruce burris et philipp m. jones, 200 p., 2020.

jacqueline b. l’indomptée texte de philippe dagen, 280 p., 2019.

jorge alberto cadi el buzo texte de christian berst, 274 p., 2019. réédition 2022.

japon brut la lune, le soleil, yamanami textes de yukiko koide et raphaël koenig, 264 p., 2019.

anibal brizuela ordo ab chao textes de anne-laure peressin, karina busto, fabiana imola, claudia del rio, 240 p., 2019.

josé manuel egea lycanthropos II textes de graciela garcia et bruno dubreuil, 320 p., 2019.

au-delà aux confins du visible et de l’invisible texte de philippe baudouin, 220 p., 2019.

éric benetto in excelsis texte de christian berst, 212 p., 2019.

anton hirschfeld soul weaving texte de nancy huston et jonathan hirschfeld, 300 p., 2018.

lindsay caldicott x ray memories texte de marc lenot, 300 p., 2018.

misleidys castillo pedroso fuerza cubana #2 texte de karen wong, 300 p., 2018. réédition 2020.

jean perdrizet deus ex machina textes de j.-g. barbara, m. anceau, j. argémi, m. décimo, 300 p., 2018.

do the write thing read between the lines #2 texte de éric dussert, 220 p., 2018.

giovanni bosco dottore di tutto #2 textes de eva di sefano et jean-louis lanoux, 270 p., 2018 .

john ricardo cunningham otro mundo 180 p., 2017.

hétérotopies architectures habitées texte de matali crasset, 200 p., 2017.

pascal tassini nexus texte de léa chauvel-lévy, 200 p., 2017.

gugging the crazed in the hot zone édition bilingue, 204 p., 2017.

in abstracto #1 texte de raphaël koenig, 204 p., 2017.

dominique théate in the mood for love texte de barnabé mons, 200 p., 2017.

michel nedjar monographie texte de philippe godin, 300 p., 2017. réédition en 2019.

marilena pelosi catharsis texte laurent quénehen, entretien laurent danchin, 230 p., 2017.

alexandro garcía no estamos solos II texte de pablo thiago rocca, 220 p., 2016.

prophet royal robertson space gospel texte de pierre muylle, 200 p., 2016.

josé manuel egea lycanthropos textes de graciela garcia et bruno dubreuil, 232 p., 2016.

melvin way a vortex symphony textes de laurent derobert, jay gorney et andrew castrucci, 268 p. 2016.

sur le fil par jean-hubert martin texte de jean-hubert martin, 196 p., 2016.

josef hofer transmutations textes de elisabeth telsnig et philippe dagen, 192 p., 2016.

franco bellucci beau comme... texte de gustavo giacosa, 150 p., 2016.

soit 10 ans états intérieurs texte de stéphane corréard, 231 p., 2015.

john urho kemp un triangle des bermudes textes de gaël charbau et daniel baumann, 234 p., 2015.

august walla ecce walla texte de johann feilacher, 190 p., 2015. sauvées du désastre œuvres de 2 collections de psychiatres espagnols (1916-1965) textes de graciela garcia et béatrice chemama steiner, 296 p, 2015. beverly baker palimpseste texte de philippe godin, 148 p., 2015.

peter kapeller l’œuvre au noir texte de claire margat, 108 p., 2015.

art brut masterpieces et découvertes carte blanche à bruno decharme entretien entre bruno decharme et christian berst, 174 p., 2014.

pepe gaitan epiphany textes de johanna calle gregg & julio perez navarrete, 209 p., 2014.

do the write thing read between the lines textes de phillip march jones et lilly lampe, 2014.

dan miller graphein I & II textes de tom di maria et richard leeman, 2014.

le lointain on the horizon édition bilingue, 122 p., 2014.

james deeds the electric pencil texte de philippe piguet, 114 p., 2013

eugene von bruenchenhein american beauty texte de adrian dannatt, édition bilingue (FR/EN), 170 p., 2013. réédituion en 2021.

john devlin nova cantabrigiensis texte de sandra adam-couralet, 300 p., 2013.

davood koochaki un conte persan texte de jacques bral, 121 p., 2013.

albert moser life as a panoramic textes de phillip march jones, andré rouille et christian caujolle, 208 p., 2012

josef hofer alter ego textes de elisabeth telsnig et philippe dagen, 2012. réédition en 2022.

rentrée hors les normes 2012 découvertes et nouvelles acquisitions édition bilingue, 2012.

pietro ghizzardi charbons ardents texte de dino menozzi, 2011.

guo fengyi une rhapsodie chinoise texte rong zheng, 115 p., 2011.

carlo zinelli une beauté convulsive texte par daniela rosi, 72 p., 2011. réédition en 2022.

joseph barbiero au-dessus du volcan texte de jean-louis lanoux, 158 p., 2011.

henriette zéphir une femme sous influence texte de alain bouillet, 2011.

alexandro garcia no estamos solos texte de thiago rocca, 2010.

back in the U.S.S.R figures de l’art brut russe texte de vladimir gavrilov, 2010.

harald stoffers liebe mutti texte de michel thévoz, 132 p., 2009. réédition en 2022.