PANHARD & CITROËN

a marriage of convenience ?

Yann Le Lay - Bernard VermeylenSummary

Summary

Introduction

Panhard & Levassor, a structurally fragile company

The Panhard – Citroën agreements: a matter of survival

The Dyna Z during the Citroën era... and the Panhard 2 CV

The PL17: low cost revival

Charles Deutsch’s bet

Final facelift for the Dyna

The Panhard 24: surviving without getting in the way

Born in a rose garden

A four year career: the evolution of the Panhard 24

Marketing: a narrow niche for the 24

Rally champion, economy champion

Panhard is no more

Panhards around the world

An illegitimate offspring: the Dyane

1

Panhard & Levassor, a structurally fragile company

Ancient origins

One has to go back to 1845 to find the origins of the Panhard & Levassor company. Two carpenters, Périn and Pauwels, joined forces to manufacture woodworking machines in a workshop in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine in Paris. In 1867 Pauwels departed and Jean-Louis Périn joined forces with the young René Panhard who in turn recruited Émile Levassor, a former alumnus from the Ecole Centrale Paris. It is he above all who would open up new directions for the company. Established in 1873 on the route d’Ivry 1 in the 13th arrondissement of Paris, the company began manufacturing German Otto & Langen gas engines under license. Levassor then befriended Gottlieb Daimler, who had worked on the design of a petroleum engine which he patented in 1885. Périn in turn departed and a new company was set up in 1886. “Panhard & Levassor” saw its capital shared between René Panhard and Émile Levassor. The latter was convinced that they should adopt the Daimler engine and develop practical applications: stationary engines, boats, trams and…cars.

Automotive industry pioneers

An initial meeting between Émile Levassor, Gottlieb Daimler and Armand Peugeot took place in November 1888. It was agreed that Peugeot would buy Daimler engines manufactured at Panhard & Levassor. Three months later, Daimler completed the development of a new engine, a 565 cc V-twin, with a significantly better power-to-weight ratio. Émile Levassor decided to develop a car equipped with this engine, the first tests of which had begun at the end of the summer of 1890. A second prototype, finished at the beginning of the following summer, was used for a two-day journey

From 1876 to 1895, the company manufactured gas engines, first under license from Otto & Langen (1876-1883), then from other origins (Friederich, Ravel, Benz and even Panhard & Levassor), from 1888 to 1895. This document shows the cover of the tariff published in 1892.

1 Renamed a little later Avenue d’Ivry.

This document dates from 1911, but perfectly symbolises the initial activities of the company created by JeanLouis Périn in 1845, and which constitute the ‘prehistory’ of the Panhard & Levassor brand. The woodworking machinery department remained active within the company until 1953, when it was transferred to another industrial group.

Motor car no. 102, put into service in September 1892, is identical to the brand’s first “production” cars powered by the Daimler licensed twin, launched a year earlier. The property of Hippolyte Panhard, it became famous by participating in the Paris to Marseille Rally between 27 March and 1 April 1893. Today it is a resident of the Musée National de l’Automobile in Mulhouse.

This omnibus with an M4F type engine, a large 3,296 cc four-cylinder, on a drive in Biarritz in 1899. On cars with this type of bodywork, the engine was placed under the driver’s seat.

Fitted with the Phénix engine, type M2E, this delivery van launched in April 1896 was the very first commercial vehicle manufactured by the brand, and truly the ancestor of all commercial vehicles.

by Émile Levassor from Paris to Étretat (some 180 km / 110 miles). This exploit confirmed for Levassor that they should start the manufacture of a series of thirty front-engined cars, an unprecedentedly unconventional layout and one which would eventually become the norm. Between 30 October and the end of December 1891 five cars were constructed. For its part, Peugeot marketed its first cars which were equipped with the Daimler engine manufactured by Panhard & Levassor at almost the same time. The automotive adventure had started!

The cars, which were constantly being improved, began to be exported in 1893. Émile Levassor understood that to permanently establish the superiority of the Daimler petrol engine, it was necessary to win the confidence of the public. The organisation of the first car races provided him with just the opportunity, and his victory in June 1895, during the Paris-Bordeaux-Paris race, had a great impact. It also demonstrated the superiority of the new Phénix engine, which was fitted with a revolutionary carburettor that allowed a very smooth operation. Levassor worked tirelessly to improve everything and continued to participate in car races. Alas, the unthinkable happened on 14 April 1897 when he died suddenly while at work.

Panhard & Levassor, a structurally fragile company 9

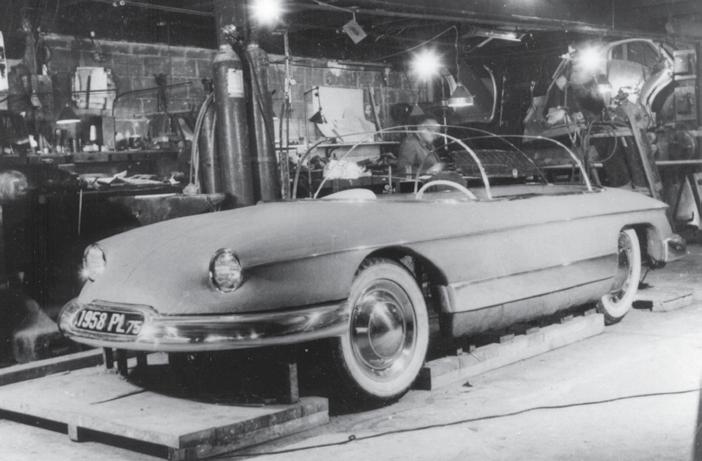

“I am the 1958 Dyna 58”

True to form, Panhard made some improvements to the Dyna during the 1957 year, but the most important change came in May, with the restructuring of the range. The base model remained the unchanged Luxe type Z11. The Luxe Spécial type Z12 disappeared and was replaced with two new models: a Grand Luxe with slightly simplified equipment, and the Grand Standing which was presented as a Luxe Spécial fitted with some additional equipment.

The 1958 Dyna was launched on 22 July 1957 and on this occasion, the Z12 berlines and the Z15 convertible benefitted from an important innovation: the so-called

The 1958 model year changes of the made their appearance on the Dyna from 22 July 1957. On this occasion, the port of Honfleur served as the setting for the shots. Seen here is the new Grand Luxe berline.

On 1 May 1957, the Dyna berline range was redesigned. The Luxe continued its career unchanged, but the Luxe Spécial was replaced by two models; a Grand Luxe (whose finish is intermediate between the Luxe and the old Luxe Spécial), and a Grand Standing close to the latter, but fitted with polished stainless steel accessory parts added to the wings of the car and polished beading lining the upholstery. The Grand Standing is the only one to retain the central fog lamp.

The dashboard of the 1958 Grand Standing berline. In addition to the twotone upholstery, we note among other things the door pockets, the chrome strips on the dashboard and the patterned steering wheel badge, reserved for the best finishes.

50 The Dyna Z during the Citroën era... and the Panhard 2 CV

The inside pages of the catalogue published for the 1957 Motor Show include this exploded view which highlights 12 strong points of the Dyna and in particular the new Aerodyne engine. Drawn by Alexis Kow it makes the car look longer than it actually was; a recurring theme in his work.

From October 1957, the Dyna Grand Standing could be delivered with a two-tone paintwork, the second colour being applied to a wide area covering the sides and the entire upper part of the body. For lack of space, Panhard parked new cars in the immediate vicinity of the factory. A 2 CV van from the same workshops is visible next to the Dyna.

Since December 1956, the range of Panhard trucks had been enriched with the IE70 model powered by the 110 bhp 4HL Diesel and fitted with an original Citroën cab. With only 87 produced until January 1961, it cannot be said that this utility vehicle was a great success.

In 1957, the production of heavy utility vehicles fell sharply at Panhard, but, in collaboration with the Ateliers Legeu in Meaux (ALM), the brand specialised in particular in four-wheel drive vehicles used among others by oil exploration companies. These vehicles were photographed at the Tineldjame borehole in the Sahara.

Aerodyne engine which was characterised by its new double-effect cooling turbine, in fact a bladed fan that directed a forced air stream on to the cylinders, and a polished aluminium shroud. This device, which optimised engine cooling, also had a very beneficial effect on noise, which was now greatly reduced, and improved the heating-defrosting system. On the inside, upholstery in a washable synthetic material (a kind of vinyl renamed Dynil) replaced the old faux leather. In the same way, the cardboard Isorel insulation, used in the Dyna, was renamed Dynorel. For its part, the Luxe berline remained identical to the 1957 model.

During the Show, Panhard exhibited six Dynas of the four models available, including a two-tone Grand Standing featuring - as did the cabriolet - a new two-tone paint option. In addition to this visible novelty there was also a Dyna fitted with a Jaeger electromagnetic clutch, a new option which replaced the short-lived Ferlec clutch, but would not be marketed until a few months later; at the Porte de Versailles (the heavy goods vehicle fair) an IE70 truck and no less than five 4x4 vehicles designed especially for the Sahara and oil exploration were on display. During the year, some detail changes were made to the range, but we are far from the multiple variants of the years 55-56.

In 1957, the Dyna was at the height of its career, with a total production that year of 37,991 passenger cars, an absolute record in the history of the company. Starting

4

The PL17: low cost revival

On 2 May 1958, Panhard’s Board of Directors met to review the lessons of 1957. The mood was optimistic. The Dyna had achieved a daily production rate of around 120 cars, up 197% on 1955. The Suez crisis in the autumn of 1956 led to an increased demand for economical cars. In addition, the alliance with Citroën and the merging of the networks seemed to be working: of the 38,000 sales made in 1957, 40.5% were within the Citroën network, i.e. 15,400 transactions. These good results, after two mediocre years, led the Avenue d’Ivry to advance the V 338 project, which had been under study for several months and was intended to replace the Dyna, born in 1953 which was beginning to show its age despite the constant improvements. It would not survive the turn of the decade, even with the addition of a new engine. The Tigre was yet to come. Production had already begun to slow: 34,000 units would be sold in 1958. At the beginning of 1959 the numbers were even worse with only 12,000 sold in the first six months. The Dyna was up against increasingly fierce competition. At the October 1958 Paris Salon, Simca’s Aronde, the pretty facelifted P60 was displayed, while Renault continued its triumphal march with the Dauphine thanks to the addition of the Gordini model; Peugeot’s recent 403 Grand Luxe sold for the same price as the Dyna Grand Standing (780,000 F against 779,000 F) and while its unfavourable 8 CV tax category 1 didn’t help, its unfailing robustness was a convincing argument.

Developed during the winter of 1957 and finalised in the spring of 1958, this Dyna replacement project remained faithful to a modular construction. The line was dramatically modernised. The final realisation was much more timid, retaining only a few stylistic elements of this project, including the shape of the wheel arches.

After a good start, Dyna sales in the Citroën network also fell sharply (down by a third in 1958), because from March 1957 the new ID 19 was offered at a price of 894,000 F in the Normale version, a price which would remain unchanged on the 1959 models. At this price it constituted an attractive alternative to the Dyna Grand

1 This difference with the Dyna (5 CV) became painful when it came to paying the road tax, introduced in June 1956 by Paul Ramadier’s Socialist government in the name of ‘solidarity’.

Several bonnet and air inlet projects were tested in using full size models. Some were rather radical (retractable headlights or headlights built into the grille), but only the license plate integrated into the bumper would be retained.

This model is not lacking in interest: although it has a bonnet and rear “eyebrows” that prefigure those of the PL 17, it also offered innovative solutions such as the extension of the bumpers to provide side protection, the shape of the windows. The upper beltline could be found on the Panhard 24 a few years later.

Standing (754,000 F). For a reasonable additional cost, the customer had access to state-of-the-art technology, the hydropneumatic suspension, and to a more “high class” vehicle, externally like the DS even if the equipment levels were somewhat parsimonious... The dealers and agents of the Panhard network, often longstanding and very loyal, lived less well than their counterparts at Citroën and when they found themselves in direct competition in the same town, the comparison could even turn out to be cruel. As Étienne de Valance reminded us during a recent interview, the executives of the Avenue d’Ivry found it difficult to deal with the haughty methods of their partner, embodied for example by the commercial inspector Jean Masclet, sent by Citroën at the time of the joining of the networks. The more conciliatory Roger Créange who succeeded him did not really manage to mobilise the Citroën garages to sell Panhards.

Thwarted ambitions

For Panhard, the window of opportunity was narrow, but the Design Office could count on renewed means, thanks to an increase in the capital of the firm, decided jointly with Citroën and authorised at the annual meeting in May 1958. The doubling of capital, which rose in June from 1.4 to 2.8 billion francs through the issue of 280,000 shares almost all of which were bought by Citroën, made Panhard even more dependent on its partner whose share had increased from 25% to more than 45%. After the summer recess, at the express request of Citroën, the Ivry plant would switch to two shifts for the assembly of vans. And Citroën did not veto the study of a new Panhard model, contrary to what almost happened a little later, when the 24 was designed. In the meantime, the V338 project had been seriously revised downwards. Originally, as evidenced by the detailed drawings made during the winter of 1957/1958, Panhard had planned to completely replace the body of the Dyna, while retaining its powertrain and running gear and retaining the principles of its construction: a robust infrastructure and a central hull onto which would be mounted separate front and rear units, which would make the best use of the layout of the Ivry factory. On paper, the sketches were attractive: the central cell, with taut lines, makes the most of its reduced structural

side sills received a wide rib. Further exterior changes, replacement of the side lights under the headlights with clearly visible lamps acting as indicators and side lights with the whole lot surmounted by “eyebrows” in the same style as those of the headlights, or decorated with a thin strip on the basic model now called PL 17 Grand Luxe. Mechanically, there were only minor modifications to report, as well as a lowering of the cubic capacity, which dropped from 851 to 848 cc without any impact on either power or torque. This reduction allowed cars to be entered in rallies in the 700 to 850 cc-category. The Mines Department gave it the L4 designation. The utilities benefitted from most of these changes.

Holding something in reserve

At the same time, the management of Panhard learned that the factory was to be entrusted with the manufacture of a new derivative of the 2 CV: the four-wheel drive Sahara, the prototype of which had been presented to the press on 7 March 1958 at the Mer de Sable in Ermenonville and then to the public at the Paris Salon in October. But the 2 CV 4x4 (the name Sahara was no longer used in the marketing) did not go on sale until February 1961, nearly three years after its presentation! Assembly started in the autumn of 1960 at the Panhard factory in Orléans, where the sub-assemblies were manufactured, and ended with the assembly of the bodywork at the Paris factory.

Actress Sophie Destrade returned to work to reveal the advantages of Relax seats. Was this languorous Brigitte Bardot pose approved by Paul Panhard?

The presentation of the 1961 F65 (and F50) resembles that of the Grand Luxe berlines: small wheel trims, absence of quarterlights and windscreen trim. The lower body mouldings, still present in 1960, have been removed.

72 The PL17: low cost revival

72 The PL17: low cost revival

The complete hulls, whose structure and special parts can be seen here, arrived from Citroën to be assembled on the production lines on the Avenue d’Ivry. Note the air intake vents above the wings.

Details of the 2 CV 4 x 4. From left to right: the reinforced chassis, the rear engine in position, the separation between the passenger compartment and the rear compartment (the partition is attached to the seat), the location under the front seats of the two fuel tanks, each supplying an engine.

The twin-engined 2 CV 4 x 4 was fitted with an additional engine in the boot. This brought the total displacement to 850 cc and fiscal horsepower to 5 CV. Large vents at the base of the C-pillar are for cooling. The number plate has been moved. The cutaway rear wings allowed the fitting of large section tyres (155 x 400 instead of 125 x 400).

From the driver’s seat, the spare wheel (which had to be moved to the bonnet with a special stamping) was visible. The floor-mounted gear lever controls either the front gearbox alone or both front and rear gearboxes together. Two ignition keys and two separate starter buttons are used to start each of the engines, each being equipped with an oil pressure warning light. Finally, a wiper motor was fitted instead of the tachometer drive, as the car was often required to move at low speed.

On the Panhard stand at the Paris Motor Show in October 1962, a white CD, whose bodywork was for the time being, made of aluminium, was exhibited on the Panhard stand, alongside Panhard’s new range. Charles Deutsch willingly posed in front of his creation. To build the show car, it seems that the chassis of the car damaged in Le Mans was reused (no. 104) since only the bodyshell had suffered. The civilian CD was profoundly modified compared with the Le Mans cars: the front end had been redesigned, the competition appendages had disappeared, the windscreen was taller, the car featured front and rear spoilers and a double bulge which makes one think of the most beautiful Italian achievements by Zagato, while the smaller petrol tank made it possible to provide an occasional rear bench seat. Slightly less aerodynamic than the competition cars (Cd 0.22 instead of 0.17), it was powered by the new version (M6) of the standard 848 cc Tigre engine which appeared at the same time on the PL 17. In the CD it offered 60 bhp which allowed a top speed of 160/165 kmh (around 100 mph). The upholstery and seats were those of a grand tourer; they were designed by the Methods department on Avenue d’Ivry. The fittings were sporty and luxurious, even if some parts could not hide their PL 17 origins. In front of the driver, two large round dials, a beautiful steering wheel with wooden rim and

For the Motor Show, a catalogue was very hastily designed. Due to an error (the engine displacement was shown as 701 cc which was the size of the Le Mans cars) it had to be reprinted quickly. The colourisation of the photo seems a bit hit and miss.

In the middle of a floral composition, the berlinette CD exhibited at the 1962 Paris Salon was inaccessible and almost certainly locked. It was only a prototype, far from being ready for production. The interior mirror is now fixed to the roof.

To be homologated, the consumer-CD received bumpers with overriders at the rear, glass windows instead of Plexiglas, multifunction rear lights, etc. Note the location of the reflectors, the twin exhausts and the opening rear windows.

Draft undated advertisement, probably from the autumn of 1962: there are few differences between the victorious car at Le Mans and the one the customer could buy...

aluminium spokes; in the centre, the controls on the dashboard were organised in three superimposed lines extended by a central console. Some unusual Panhard accessories were fitted as standard: a cigarette lighter, fog lights and a grab handle on the dashboard. However, the braking, like the other 1963 models, used ETA drums (the CD would never be fitted with the discs mounted on the 24 CT and BT from the autumn of 1964), while the 145 x 380 Michelin X tyres, the same as those of a PL 17 Tigre, seemed somewhat narrow. Compact and lightweight with its length of 4.06 m (160”); width of 1.60 m (63”), height of 1.18 (46.5”) and unladen weight of 660 kg (13 cwt) the civilian CD became the fastest production car Panhard ever produced. Its elegance and the promises of performance and safety earned it the Grand Prix de l’Art et de l’Industrie in the Sport and Grand Touring category at the opening of the Motor Show. By the end of the event, 17 orders had been signed without any testing having been carried out, and serious contacts had been made with nearly 700 customers. Panhard hoped to manufacture, before the end of 1963, 1,000 copies of this car, in order to obtain homologation in competition in the Tourism category, where the CD would easily prevail.

Panhard quickly released factory photos to the press showing the new CD from all angles, as well as its sporty interior. The dashboard remained close to that of the competition cars. Note the installation of the horn/headlight switch, designed to “fall to hand” next to the gear lever.

V527: the development of a style

Produced on the instructions of Louis Bionier, the documents provided by René Ducassou-Péhau were in the form of watercolours, sketches or scale drawings some of which displayed an American influence (fins, a panoramic windscreen, pillarless windows). But other features quickly found a distinctive style: protruding boot lid housing, elongated lights, rounded front wheel arches, the prominent beltline surmounting hollow sides and large headlights mounted in nacelles. Another feature long present in the drawings and fullscale models was the extension of the bumpers around the sides using an imposing protective moulding. This principle would finally be abandoned but eventually appeared in the Renault 5 GTL of 1976.

1/10th

no. 1882 dated 11 June 1960: proposed

Undated drawing, probably one of Ducassou’s first for the project. Although it features a rather awkward front with a huge panoramic windscreen the rear part already foreshadowed the future 24.

134 The Panhard 24: surviving without getting in the way

scale drawing

bodywork for a 3-seater coupé. Note the spoiler on the roof and the concave rear window.

Drawing signed Ducassou no. 1934 of 18 July 1960. The letters LM in the number plate stand for Longueur Maximale, or maximum length; here it is 4.25 m or 14 ft.

Drawing signed Ducassou (1 /5th ) no. 1980 of 10 October 1960: VS profiles. Note the flatter roofs and the one piece bonnet.

134 The Panhard 24: surviving without getting in the way

scale drawing

bodywork for a 3-seater coupé. Note the spoiler on the roof and the concave rear window.

Drawing signed Ducassou no. 1934 of 18 July 1960. The letters LM in the number plate stand for Longueur Maximale, or maximum length; here it is 4.25 m or 14 ft.

Drawing signed Ducassou (1 /5th ) no. 1980 of 10 October 1960: VS profiles. Note the flatter roofs and the one piece bonnet.

1/5th scale drawing no. 1990: coupé 2 + 2. Note the marked longitudinal belt line joining the headlights to the tail lights, a very rounded roof, dished steering wheel and right hand drive.

Drawing no. 2012. A very harmonious design.

Two colour drawings signed Ducassou, one from 7 November 1960, the other undated. Note: the imposing side protection in the extension of the bumpers. The shapes of the front and rear have been found, except for the headlights, but the roof is still quite rounded. Centrally mounted instruments were envisaged.

1/5th scale drawing no. 2105 of March 20, 1961: VX car. Yet another right hand drive car is depicted. Note the straighter lines and flat roof but the position of the pillars was yet to be found.

Drawing no. 2230 of May 5, 1961: VX profile. Note the lines that differ from the previous designs and the original styling features (front air intake, headlights, wheel arches, location of the beltline).

8 Born in a rose garden

The 24 conquers Versailles

In March 1963, Étienne de Valance started looking with the help of the SNP,1 for a beautiful place in which to present the new model. Initially, an aerodrome to the south of Paris was considered, either Villacoublay or the main hall at Orly airport. This initial project was abandoned in favour of a more rural setting suggested by the SNP: the Truffaut rose gardens at Versailles. The site was available free of charge, apart from any floral decorations. Traditionally, at Panhard, the presentation of new models took place on the Monday immediately following the Le Mans 24 Hours. The reason was very simple: the choice of this date meant that the many foreign journalists present would not have to schedule an additional trip to France. And in 1963, the anniversary of D-Day (when the allies landed in Normandy in 1944 to start the liberation of France) fell on 24 June. A totally appropriate date to reveal a new car named 24. On Friday 14th, the invitation cards were sent. Sales staff were given a preview presentation on Saturday 22nd at the Ivry Palace cinema, where, after a speech by Mr. Léger, they looked at the 24 C and CT (with all the doors closed) and four 1964 17 berlines.

The cardboard sleeve of the press kit given to journalists during the presentation of the 24 recalls the prestigious and already long history of the brand, underlined by the words “The prestigious coat of arms of the Panhard company has stamped its seal on a long line of classy cars”, of which the 24 was obviously the worthy heir.

1 The Société Nouvelle de Publicité, a subsidiary of the Havas group, designed and published the brand’s advertising materials at the time.

This right hand drive Fandango red 24 CT was on display at the presentation at Truffaut. A door is open so that guests can see the interior layout. However, the other 24s on display remained locked.

On 9 July 1963 dealers and agents from the North-East region were invited to discover the new 24 in Reims at the premises of the Pommery champagne producers. (FDPMHI)

When the big day arrived, the organisation of the events was precisely scheduled:

• Delivery of cars from 7 a.m.

• From 9 to 10 a.m. VIPs’ reception.

• From 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. press reception: successive speeches by Paul Panhard (5 minutes) and Jean Panhard (15 minutes) to be followed by a buffet, each journalist receiving a complete file before leaving the premises.

• From 4 to 7 p.m. Citroën sales department meeting, with speeches by the same speakers, followed by a buffet.

As part of the Points Cardinaux operation, on 29 June 1963 the 24 was presented at the Aéro-Club in Angoulême for the regional sales network and local journalists. Contrary to what was done at the launch of the PL 17, the cars were transported to the site by road. (FDPMHI)

Four cars were on display, two 24 Cs and two 24 CTs. One car was placed on a platform in the middle of an ornamental pond, another was on a podium. In addition, a CT without doors was displayed allowing one to view the interior. The last car, a C, was fully accessible to visitors. This exhibition was completed by ten PL 17 berlines in different configurations, two breaks, two utility vehicles and a CD. Finally some PL17s were available for test drives - six berlines, a break and a CD. Once the day was over, one of the 24s and several 17s were transported to the Champs-Elysées store to be exhibited there, though the 24 remained locked. On 26 June there was a presentation in the factories in Reims, Orléans and Paris, followed by a series of regional meetings called Opération points cardinaux (Operation cardinal points), for sales staff and local journalists, in Laval, Angoulême, Avignon, Beaune, Reims and Saint-Germain en Laye, between 27 June and 11 July.

During these presentations, the journalists were given a folder containing photos and a brochure. To achieve the latter, very shortly before the presentation of Versailles, Louis Bionier was persuaded to loan a car, followed by a few two-hour photo sessions. For the sake of secrecy,

Enthroned right in the middle of the Truffaut rose garden in Versailles, as if delicately placed on the surface of a pond lined with water lilies, a two-tone 24 C prototype (Quetsche with a Capeline grey roof) attracted everyone’s attention. Lacking an engine, blocks were placed underneath the bonnet to ensure the car remained horizontal.

Marketing: Marketing: a narrow niche for the 24

Since the 24s were now Citroëns, the Delpire agency was commissioned to design and print the catalogues. The beautiful catalog for the 1966 model year (and reprinted for 1967) adopts the original and recognisable style of the famous agency. The document contains superb photos of undeniable artistic merit.

Alongside these more or less luxurious brochures, there was an individual sheet for each model and, for the 1967 model year, this leaflet was devoted to the technical characteristics. Interestingly the Panhard name used a much smaller font than the word Citroën.

Since the 24 had been counted as a Citroën product since the merger, the monthly production figures were reported in the minutes of the Board of Directors from July 1965. This shows a slow fall in sales over the months, as can be seen in the table below.

Very rare today, this little leaflet published in 1966 shows, using a flap, the difference between the sports coupé (the CT) and the 4/5-seater berline (the B and BT). A detachable response card allowed one to request a test drive.

Production figures

When the 1967 models were launched, the fate of the 24 appeared to be sealed in the relatively short term, resulting in a halt in those investments needed to boost sales. Despite being very successful, the competition budget for the 24 was not renewed at the end of the 1965/1966 season and communications about the marque became rare. They no longer invested in the improvement of this model and the beautiful catalogue of the previous season was reused for 1967, despite the fact that the now obsolete 24 BA was included. One can imagine that at this stage, it was above all a question of liquidating the stocks of parts accumulated for the manufacture of the cars. As if Citroën wanted to get rid of a ball and chain at any cost, the announcement of the end of production made on 20 July 1967 was two months before the last car left the production line on 19 September…

Marketing: a narrow niche for the 24 189

The cockpit of a Dyna Z12 Rally: the dashboard is standard, but a tachometer and tripmaster have been fitted. The front seats were replaced with seats borrowed from a 2 CV Citroën to save precious kilos.

Heures

de Sebring, Prix de Paris, Coupes de Paris and Circuit de Clermont-Ferrand in 1959, 1,000 km at the Nürburgring, the Rouen GP, the Circuit des Six Heures d’Auvergne and the Paris 1,000 km in 1960. At the end of the 1962 season, these wins earned Panhard the title of French champion in the Sport category. If the presence of the marque was very limited subsequently for various reasons, the fact remains that Panhard claimed a remarkable track record in ten years of targeted hard work.

In rallying, the Dyna Z happily succeeds the Dyna X

The exceptional displacement/weight/performance ratio enjoyed by the Dyna Z1 worked wonders. Both streamlined and light, the car reached 130 kmh (81 mph) thanks to its 851 cc 42 bhp flat-twin, which let it compete with much more powerful cars which, most often, had inferior roadholding and handling. It was no surprise then, that the team of Gillard and Dugat achieved a brilliant 2nd place in the general classification in their Dyna during the 1955 Monte-Carlo Rally. Panhard advertising obviously made much of the many competition successes. The Dyna 56 brochure thus highlighted “the (car) mechanism with 600 victories”. The abandoning of the aluminium hull in 1956 undoubtedly complicated the task of the drivers a little, but this was hardly reflected in the results, even more so as some continued to race the old all aluminium Z1s or even the antediluvian Dyna X! Of course, the derivatives, in the forefront of which was the DB HBR5, largely contributed to the plethora of victories. It is obviously not possible to go into detail on all the achievements of the Dyna and PL 17 in rallying from 1956 to 1961, so we will content ourselves with

1 See chapter 5.

192 Rally champion, economy champion

Run from 24 February to 1 March 1957, the Sestriere Rally saw the old Dyna X86 crewed by the Italian team of Bianchi and Borghesio triumphed in the general classification. Before the race, the team availed themselves of a factory visit to take advantage of the latest developments.

At the Grand Prix des Voitures de Série (Production Cars Grand Prix), held on 12 May 1957 on the Francorchamps circuit, it was the Belgian driver Berchem who proved to be the fastest in his category, at an average of 126.346 kmh (78.508 mph).

By ranking first overall and in the performance index, the Dyna Z12 of Bernard Consten and Jean Hébert offered Panhard a magnificent victory, in the Rallye des Routes du Nord, run from 7 to 9 February 1958, and this in particularly difficult conditions, mixing snow, ice and fog. To commemorate this win the brand had this beautiful garage poster made.

Neither the identity of the crew nor the classification of this Dyna participating in the Trophée de Provence, from 7 to 10 May 1959 are known.

listing the most significant here, limiting ourselves to series cars:

• 13 May 1956: Grand Prix des Voitures de Série à Francorchamps; category win (Van Hauw)

• 26-27 May 1956: Rallye de Dieppe: overall victory (Trimatis)

• 23-24 June 1956: Rallye Alpin des dix cols: overall victory (Robin-Bourrely)

• 24-28 February 1957: Rallye de Sestrières: overall victory (Bianchi-Borghesio, sur Dyna X86)

• 7-9 February 1958: Rallye des Routes du Nord: overall victory (Consten-Hébert)

• 31 January / 1er février 1959: Critérium Neige et Glace: category win (Bernard-Charlois)

• 6 April 1959: Rallye de la Forêt: overall victory (Lelong et Mme)

• 12-13 December 1959: Tour de l’Oise: overall victory (Lelong et Mme)

• 13 March 1960: Rallye de Printemps: overall victory (Lelong et Mme)

• 15-23 September 1960: Tour de France: overall victory (Lelong-Delignère)

• 21-28 January 1960: Rallye de Monte-Carlo: overall victory (Martin-Bateau)

The MEP X2: Last stand for the Panhard flat-twin

More than twenty years after its creation, the flat-twin Panhard was about to bow out. At the last moment, a reprieve was granted thanks to the Citroën dealer in Albi, Maurice Émile Pezous. The latter, an engineer from l’École Supérieure Nationale d’Arts et Métiers and a naval air engineer-mechanic, was already known for having, marketed a pretty coupe in 1954 borrowing the mechanical components of the Citroën 11 CV under the MEP brand, an acronym for the initials of its creator.

In the mid-1960s, the Formule Vee had just appeared: light single-seaters using the mechanical components of old Volkswagens were offered to apprentice drivers wishing to train in motor racing at a low cost. The phenomenon came to the ears of Maurice Pezous, who then imagined building a French single-seater which could play the role of an initiation formula in France, using

This rear view allows you to see the tube frame. The Panhard M10S engine is centrally located behind the driver and behind it, at the extreme rear, the fourspeed gearbox borrowed from the Ami 6 is coupled to the engine via a special spacer.

In January 1967, the magazine Moteurs dedicated its cover to the new MEP X2. Alain Bertaut wrote: “The MEP, in its presentation and in the care given to the realisation of many details can, without blushing, bear comparison with the best of its kind”.

Citroën mechanical elements. His project took a long time to think about: “I set myself two imperatives from the outset: first, I banned DIY by relentlessly carrying out real engineering work. Then, I led my project by telling myself that it could only be viable if this car were built in small series. […] I wanted to provide young people with a machine that has all the characteristics of a competition single-seater,” he said to the driver and journalist Alain Bertaut at the end of 1966 1 .

His prototype, the MEP X1, was ready in 1965. Pezous chose the most powerful twin-cylinder from Citroën’s range, the 602 cc engine from the Ami 6, which at

From the rear, the MEP clearly displays its membership of the Citroën family. The suspension is independent on all four wheels. All suspension parts are chrome plated and hinged on good sized Uniball ball joints.

Rally champion, economy champion 203

1 During a test of the MEP X2, published in Moteurs magazine No. 59, January 1967.Panhards around the world

Although the agreements between Panhard and Citroën initially had no effect on the distribution of Panhards abroad, this situation was only temporary. Although the networks of the two brands were combined in France, in 1956, it was decided to wait until the following year to see how the situation would evolve regarding exports. There were two aspects here: firstly assembly, which in Europe took place in Belgium and Ireland, and in Uruguay and Chile in Latin America, while the second aspect was imports and distribution to many countries around the world. Here you will find an overview, by geographical area, of the export situation. 1

Apart from a few markets for which we have details from other sources, the tables reproduced below only concern Dyna Z1s, PL 17s (from 1960 2 to 1965 model years), CDs and 24 Cs / CTs of 1964 model year only. Aside from an overall number for Dyna Z1s, the numbers are for model year and not calendar years. Finally, the countries are mentioned under their name at the time with the current name appearing in parentheses where appropriate.

1 Given the total absence of production records for Dynas other than the Z1 (from 1953 to early 1956) and the lack of information on exports provided by the records for Panhard 24s from the 1965 model year onwards.

2 The PL 17 registers are almost complete, but are missing a batch of around 6,000 cars at the end of 1959 (i.e. 18% of the model year), some of the commercial vehicles from the 1960 model year and all convertibles (except the last ones) from the spring of 1962. On the other hand, some figures are available from other sources: for the entire Panhard production at the Citroën factory in Forest, Belgium, we have a complete copy of the registers.

The Dyna bodies are painted, but the rest of the cars are only at the very beginning of their assembly. In the background, the Dynas are at the end of the assembly line (Photo Devaux).

The Dyna Z12 assembly line in Forest in 1957 or 1958. The final assembly operation was the fitting of the bumpers. (Photo Devaux)

This Belgian advertisement published at the beginning of May 1957 announced the resumption of the sale of Panhards by the Citroën network and the assembly of Dynas at the Forest factory. The drawing shows the emblematic Citroën building in Brussels.

Citroën Belgium published numerous advertisements for the Dyna in the press. This dates from May 1958 and highlights its good fuel consumption.

Europe: the brand’s main market

Belgium and Grand Duchy of Luxembourg

It was on 4 April 1957, during a visit to the Brussels facilities by Paul and Jean Panhard, that the news broke: from that day on, the import, sale and assembly of Dynas for Belgium and Luxembourg were handed over to the Société Belge des Automobiles Citroën, which had taken over many the staff employed by the former importer, SA Harold de Hemptinne. Mr. Rolland, the commercial director, continued to perform this function at the Belgian headquarters of Citroën at the Place de l’Yser

in Brussels. In fact, the assembly of Dyna berlines had already begun with the production lines being finetuned on the first three cars as early as February. In March, 66 cars left the Citroën factories in Forest, to the south of Brussels. Subsequently between 50 and 100 Dynas were assembled each month. These volumes were expected to increase significantly with the launch of the PL 17 in 1959 and remained at approximately 300 monthly units until 1962. Assembly activity continued until June 1963 with the last PL 17 L6s and L7s. The very last Panhard assembled in Forest was a blue L6, serial number 2.171.212, which came off the line on 22 June 1963.

On July 12, 1959, Paul and Jean Panhard went to Brussels; having just disembarked from the Sabena helicopter which brought them from Paris, they were greeted on the Place de l’Yser by Raymond Pérée, then director of the Belgian subsidiary of Citroën. (Photo Devaux)

For tax reasons, the Dynas assembled in Forest incorporated a number of parts supplied by local Belgian manufacturers, including glass, wheels, tyres, battery and paint. Until 1963 the colours were also different from those found on the French Dyna, because they were those used on the Belgian-built 2 CV, Ami 6 and ID/DS. The upholstery however was the same as that used in France. The Belgian-assembled Dyna Z12 and Z16 also retained the polished aluminium bonnet and rear wing strips until June 1959. On French cars, these were painted. Initially, the car was offered in a single version, officially called Grand Luxe with a second Luxe version appearing in January 1958. The Grand Luxe was, more or less, the same as the French Grand Standing, but the Luxe was midway between the French Luxe and Grand Luxe 3 versions. It is interesting to note that these two trim levels were maintained until assembly ceased in Belgium in June 1963, independently of the changes in finish made to the cars assembled in France. At the time of the Dyna, the Belgian range did not include the convertible, Jaeger clutchless transmission, Tigre engine or two-tone bodywork. These shortcomings, apart from two-toned paint were corrected with the arrival of the PL 17. The Belgian plant also assembled several D65 panel and tarpaulin vans and a few PL 17 convertibles. There is some mystery about these vans,

3 The manufacturer’s plate for Belgian Luxe models shows the type BGL, as it does for French Grand Luxe models.

Chile

A number of PL 17s, including 42 x WL1 and WL3 chassis-cabs were delivered in CKD, and just four berlines were delivered to Santiago between 1960 and 1962.

Uruguay - PL 17s in many varieties

At the time of the Dyna X, the Barrère & Cia company had imported a good number of cars and numerous chassis-cabs that were bodied on site. In 1961 another importer, Mutio Passadore & Cia, took the initiative to distribute Panhards in Uruguay. The company, founded by Jorge Mutio, Albérico Passadore, Ruben

Despite the poor print quality, we wanted to show this advertisement which probably dates from 1962- 63. It presents little-known variants of the local PL 17s, curiously renamed here F50: a pick-up which uses the rear of the berlines, a break and a sort of limousine with unusual aesthetics...

This photo taken at the Montevideo Motor Show in 1962 shows part of the Panhard stand, with an F65 chassis-cab, and, unfortunately cut off, a PL 17 berline transformed into an F50 pick-up de Lujo.

Two versions of Lujo’s F50 pickup marketed in Uruguay from 1962 to 1966 (here, 1965 models). The difference between the two lies in the treatment of the rear part, separated and completely open for one, without clear separation and retaining the berline boot lid on the other. The front has undergone a unique treatment, and, in the authors’ opinion, aesthetically less successful than the original design.

Annual sales (Peru)

Source : Fernando Murgah

This advertisement published in the autumn of 1962 presented the new MP range, a utility model whose body and chassis were designed in Uruguay around Panhard mechanical components. The letters MP are simply the initials of the importer, Mutio, Passadore y Cia.

This

Buenchristiano and Jorge Astigarraga, took over the company C. Hernandez & Cie, in Montevideo. To avoid the customs duties imposed on fully assembled cars, they decided to import cars and chassis cabs in parts. They had in their company one Mr. Pasture, a commercial inspector of Basque origin, established in Argentina and who represented Panhard’s South American interests. Pasture sold PL 17s with some success in Argentina, and in a letter he addressed on 7 April 1961 to Mr. Casparin the export department at Panhard, he explained: “I assure you that the people know the Panhard here in Argentina. The Grand Prix received huge publicity, as well as in Montevideo. With the principle of assembly and the sale price that we have, it will sell very well”. The authorisation made it possible to deliver 17 cars in 1961, and led to the dispatch, on 24 May 1962, of 96 x PL17 L4 infrastructures bound for Montevideo. Also in 1962, we note that 72 x F65 (WL3) chassis-cabs were shipped to Uruguay in CKD. These vehicles were fitted with a whole series of bodies designed locally: breaks of differing types, several of which were oneoffs (there were several small bodybuilders in Uruguay carrying out this kind of adaptation to vehicles of various brands), pick-ups, two-door berlines whose specific parts were moulded in fibreglass, and even a four-door body reminiscent of a limousine, only two of which were built, including one for Jorge Mutio himself. Somewhat mysteriously, Uruguayan PL 17 pick-ups and breaks are called F50 in the advertising. Which isstrange since, to our knowledge, no F50s were ever imported into the country. As for the two-door PL 17s, which appeared only towards the end of 1964 or the beginning of 1965, we were unable to find out whether they too were considered to be F50s.

Born on 4 July: the MP

At the same time, on 4 July 1962, Mutio Passadore y Cia presented to the press a vehicle whose Jeep-type bodywork was entirely original: this MP (the initials of the company) was available in several configurations: a break, a 750 kg van and a pick-up, of which there were several variants. The body of the MP sat on a tubular frame reinforced by double side members in sheet

forward a little to prevent the driver’s fingers touching the air intake and de-icing vent. Another innovation concerning the dashboard: the linear speedometer has a flat glass angled to prevent reflections. Ventilation was augmented at the front by two-way sliding windows. Interesting detail, it was initially proposed to separate the front windows along a diagonal line, retaining the principle of the 2 CV, but this arrangement did not survive tests in real conditions. On the other hand, the third side window, although fitted to the 2 CV from the 1966 model year, was initially rejected for the Dyane.

Citroën muzzles Panhard’s designers

If the initial drawings were done quickly and efficiently by the BERC, one point soon posed a problem: the front end, which Bionier wanted to be vertical as on the Renault 4! There was consternation when the initial model arrived in rue du Théâtre to be shown to the general staff: Pierre Bercot immediately told Robert Opron that the nose must be reworked. This change, viewed as catastrophic in the BERC, required many sketches both by René Ducassou at Panhard and Jacques Charreton at Citroën. An initial proposal from Opron to make the small grille more acceptable by fitting it with a honeycomb mesh as would be found on the GS upset Louis Bionier, who exclaimed: “Opron reproaches me for having made a wall, but he laid the bricks!”

Dated February 1965 and redrawn in May 1966 for archiving purposes, this drawing is full of ideas despite its questionable style. The registration number VP5 marks a continuity with the nomenclature of the post-war Panhard Design Office. The wings are integrated into the overall line. The flat-glass windscreen with side windows is reminiscent of the Dyna Junior. Some of the features dear to René Ducassou’s heart are the integral cross-swept windscreen wipers and the anti-reflective bonnet. The front windows open horizontally in half.

A 1/5 scale plastiline model of the Dyane as it looked on 19 March 1965, one and a half months after the project was launched. It was made by Panhard’s modeller, Jacques Perraud, from drawings by René Ducassou, which proves that he was able to define the general shape of the AY very quickly. The bonnet was flat, with a wide raised rib separating two air intakes. The front end is still very vertical.

258

An illegitimate offspring: the Dyane

These drawings are dated 5 March (right) and 24 March 1965 (below). The ribbed rear quarter panel was not retained, nor was the petrol filler flap or the square headlamps (instead, the Dyane got round headlamps enclosed in an angular bezel). Another notable difference is the very vertical front end, with a grille reminiscent of the Vietnamese Dalat. Citroën rejected the front end, which allowed René Ducassou, according to his own testimony, to “design for four more months”.

On 9 April 1965, two versions were designed: a brown country model and a green city model, with more luxury and more chrome parts.

An illegitimate offspring: the Dyane 259

An illegitimate offspring: the Dyane 259

ISBN 978-90-832960-9-8

9 789083 296098

Except for the very specific field of military vehicles, which is the only surviving activity of Panhard & Levassor’s glorious adventure, the marriage between the oldest automotive brand and Citroën lasted a mere twelve years. More precisely, from April 1955 to September 1967, the production date of the last Panhard 24, whose rich career is covered in depth in this book. Whatever one might think, the Panhard heritage is not completely lost at Citroën. Thanks to men and methods derived directly from Avenue d’Ivry, the builder of Javel significantly enriched its know-how.

More than fifty years have subsequently passed, and we think it is time today to take an objective look at this period, overcoming some still tenacious grudges held by Panhard-enthusiasts. We cannot rewrite history, but we can make it accessible to all those who are interested in both brands, or simply to those who are curious about automotive history as a whole.