Gettysburg Tourism: 50% Open

by Leon ReedThe reopening of Gettysburg will be a welcome change for merchants, unemployed workers, and people wanting to visit, but while Devil’s Den and the Pennsylvania monument will remain as iconic locations, returning visitors in coming weeks will encounter a very different place from what they remember. While tourists will still be able to obtain lodging and food (carry out and outdoor seating) and do some shopping, many of the most visible attractions will remain closed for now.

Governor Wolf announced that Adams County would enter “Phase Yellow” on Friday, May 22. This means most businesses were able to open with requirements for face masks, limited crowds to facilitate social distancing, and frequent cleaning. No announcement has been made about the Park, which means its status for now will remain the same: the Park grounds are open but the visitor center is closed and all ranger programs and other park activities are off for now.

Like all towns in America, Gettysburg suffered during the shutdown. Unemployment increased from ~3% to well over 10%; businesses catering to

tourists, weakened by several down years of park visitation, had to shelve plans for a strong recovery year. Business, government, and community groups were busy during the shutdown preparing for a smooth opening. The Borough of Gettysburg offered no-interest loans to help local businesses survive the crisis. Main Street Gettysburg, a downtown merchants association, developed and distributed a “pandemic” kit with hand sanitizer, fact sheets, signs, and “social distancing” markers. Destination Gettysburg prepared a “visit Gettysburg” ad campaign to run when reopening is authorized.

Norris Flowers, President of Destination Gettysburg, believes tourists will return quickly. He predicted that families may avoid long vacations that require an airplane trip and may revive “the family vacation in a car.” He suggested that proximity to major cities and the predominantly outdoor setup will both help draw visitors. A B&B owner shared a similar prediction. “I predict business will come back when the museums, shops, and restaurants are able to open, hopefully by mid-June 2020 will see mostly local and regional business with visitors from an approximately 200 mile radius. … Gettysburg is fortunately located within a 3 hour drive for a few million people, many of whom already love coming to Gettysburg.”

Another hotel owner predicted a “slow, long recovery.” He noted that his order book for June and July, when his hotel normally is 80-90% full, stands at 20-30% now. He noted that the status of major events, such as Bike Week, will go a long way to determine how the rest of the summer goes.

Whether the decision maker is the Park Service (activities in the Park), the Gettysburg Foundation (the visitor center), a local government, or individual businesses, visitors are likely to encounter much more emphasis on social distancing and crowd control. Some merchants seem to be taking an even more cautious attitude than the state requirements.

Local Park Service or Foundation officials need to make

tough decisions about issues such as whether there is a way to open the visitor center safely; when, or whether, to resume such popular activities as ranger talks or Cyclorama visits, and whether visits can resume at the Wills House or the Eisenhower farm. The days of three busloads of middle school students arriving simultaneously at the visitor center are probably over.

Superintendent Steven Sims commented “The health and safety of our visitors, employees, volunteers, and partners continues to be paramount. At Gettysburg National Military Park and Eisenhower National Historic Site, our operational approach will be to examine each facility’s function, and services provided, to ensure those operations comply with current public health guidance and will be regularly monitored. We continue to work closely with the NPS Office of Public Health using CDC

guidance to ensure public and workspaces are safe and clean for visitors, employees, volunteers, and partners.”

Most decisions about park operations remain in flux at this writing. From numerous conversations with people familiar with Park operations, it seems that planners haven’t yet identified a way to open the visitor center safely. Opinions of people knowledgeable about park operations ranged from “it won’t open this year,” or “it won’t reopen until Adams County goes to green,” to “they still haven’t identified a safe way to open the facility.”

Other events that draw crowds, such as ranger talks, are areas of concern and may remain so even after park facilities open. While formal ranger talks are off, effective May 22, rangers were authorized to interact occasionally with visitors by “roving” through the park. The Lincoln Fellowship, which sponsors “100 Days of

Taps” at the Soldiers National Monument, announced the park was prohibiting such live events and that the sundown “Taps” would be a virtual event until further notice.

Licensed battlefield guides were permitted to resume tours as of May 22 with some restrictions, including compliance with a manual prepared by a committee of guides, including two who are MD’s. Tickets will be available at the Guide Office or the Gettysburg Heritage Center.

Battlefield bus tours will run from the Gettysburg Tour Center on Baltimore St., weekends only at first, but not from the visitor center. The buses are not operating at full capacity in order to maintain social distancing.

The park is also considering crowd control measures such as limits on audiences for ranger

Civil War News

Published by Historical Publications LLC

520 Folly Road, Suite 25 PMB 379, Charleston, SC 29412

800-777-1862 • Facebook.com/CivilWarNews mail@civilwarnews.com • www.civilwarnews.com

Advertising: 800-777-1862 • ads@civilwarnews.com

Jack W. Melton Jr. C. Peter & Kathryn Jorgensen

Publisher Founding Publishers

Editor: Lawrence E. Babits, Ph.D.

Advertising, Marketing & Assistant Editor: Peggy Melton

Columnists: Craig Barry, Joseph Bilby, Matthew Borowick, Salvatore Cilella, Stephanie Hagiwara, Gould Hagler, Tim Prince, John Sexton, and Michael K. Shaffer

Editorial & Photography Staff: Greg Biggs, Sandy Goss, Michael Kent, Bob Ruegsegger, Gregory L. Wade, Joan Wenner, J.D.

Civil War News (ISSN: 1053-1181) Copyright © 2020 by Historical Publications LLC is published 12 times per year by Historical Publications LLC, 520 Folly Road, Suite 25 PMB 379, Charleston, SC 29412. Monthly. Business and Editorial Offices: 520 Folly Road, Suite 25 PMB 379, Charleston, SC 29412, Accounting and Circulation

Offices: Historical Publications LLC, 520 Folly Road, Suite 25 PMB 379, Charleston, SC 29412. Call 800-777-1862 to subscribe.

Periodicals postage paid at U.S.P.S. 131 W. High St., Jefferson City, MO 65101.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: Historical Publications LLC 520 Folly Road Suite 25 PMB 379 Charleston, SC 29412

Display advertising rates and media kit on request.

The Civil War News is for your reading enjoyment. The views and opinions expressed herein are those of its authors, readers and advertisers and they do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Historical Publications, LLC, its owners and/or employees.

P UBLISHERS :

Please send your book(s) for review to: Civil War News

520 Folly Road, Suite 25 PMB 379 Charleston, SC 29412

Email cover image to bookreviews@civilwarnews.com. Civil War News cannot assure that unsolicited books will be assigned for review. Email bookreviews@civilwarnews.com for eligibility before mailing.

ADVERTISING INFO:

Email us at ads@civilwarnews.com Call 800-777-1862

MOVING?

Contact us to change your address so you don’t miss a single issue. mail@civilwarnews.com • 800-777-1862

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

U.S. Subscription rates are $38.50/year, $66/2 years, digital only $29.95, add digital to paper subscription for only $10/year more. Subscribe at www.CivilWarNews.com

This year we did not publish a separate Gettysburg section due to the cancellation of all of the events in Gettysburg and the COVID-19 impact on the town. Instead, we have made this issue a Gettysburg issue. It contains all of the content that would have been

Letters Editor to the

TO THE EDITOR:

Joe Bilby and his “Black Powder; White Smoke” column continues to be my first read with each new issue. He always manages to come up with interesting and informative scholarship.

I also appreciate Ms. Hagiwara’s terrific “Through the Lens” articles with the wonderful colorized photos.

Craig Barry seems to really do his homework and has a knack for inserting some great off the wall minutiae that just blows me away.

John Sexton and Shannon Pritchard both present the most amazing artifacts to share with those of us who can only dream of ever handling such important relics. Tim Prince always fascinates me, not only with his fantastic firearms expertise, but also his attention to detail. His artifact photography enhances the whole experience of learning from these experts.

Captain David A. SulinTO THE EDITOR:

I read with great interest the June edition of the Civil War News and the article: “Fact or fiction? Black Confederates” by Dr. Lawrence E. Babits. Based on the large amount of information on this subject, I hope this article is the first of many.

In regard to the Dr. Lewis Steiner/Maryland-Antietam account, I found that this account was included in the book “Antietam and the Maryland and Virginia campaigns of 1862 from the government records—Union

included in a separate section.

You may have noticed that we have not been publishing the Calendar of Events section over the past couple of months. This exclusion has been due to the cancellation of almost all events and gatherings. When everything

and Confederate—mostly unknown and which have now first disclosed the truth; approved by the War department” by Captain Isaac W. Heysinger.

This book can be found on line on the website: archive.org/

is safe to open to the public and Civil War shows, reenactments, living history programs, etc. are re-scheduled, we will begin publishing the Calendar of Events section again. We are all looking forward to that day and hope it happens very soon.

details/antietammaryland00hey/ page/n13/mode/2up.

While I cannot vouch for the accuracy of this book, I think it is well worth reading and drawing your own conclusions.

Bob Brewer Gaithersburg, MD By Lawrence E. BabitsCivil War Alphabet Quiz - E

1. General Lee’s bald, “bad old man”

2. John B. Hood first led the Texas Brigade in this 1862 Virginia battle

3. The other name for the Battle of Pea Ridge

4. The engineer who designed and built Mound City gunboats

5. Commanding officer, NY Fire Zouaves, shot by an Alexandria, Va., hotel owner

6. Sherman’s brother in law who also came from 13th Infantry to be a general

7. Confederate division commander who lost a leg at Grovetown, Va.

8. He gave the “other,” much longer Gettysburg Address

9. Remote power source that detonated Confederate river torpedoes

10. This Jan. 1, 1863 document only freed slaves in Confederate controlled territory

Answers found on page 47.

walks. Town tours and carriage rides are also still on hold, but may be opening soon if not already by the time this issue reaches CWN subscribers.

The concern is magnified by worries about visitor behavior.

On a pleasant Sunday afternoon in the midst of the shutdown, at least five groups of 8 or more people were seen clustered together in Devil’s Den; none of them were practicing social distancing or wearing a mask. Maskwearing has become a partisan issue in Gettysburg. The state senator representing Gettysburg has been a leader of the “open now” movement and lately has called on his supporters to refuse to wear masks. Several local merchants expressed concern about confrontations between their staff and visitors insisting on their “constitutional rights.”

Most businesses and many local attractions are preparing to open with modified practices. Restaurants continue to offer carry-out and sometimes delivery service. Effective June 5th outdoor seating is permitted for businesses in the “yellow phase.”

Bars remain closed as well. Most hotels will be open with heightened cleaning and disinfecting efforts. Carry out of alcoholic beverages is permitted, and will soon available to be served (June 5).

The Lightner House B&B is practicing social distancing and asking guests to wear face masks at check-in and while socializing inside. To facilitate distancing, they are offering breakfast in guests’ rooms just this year.

Eileen Hoover, owner of the B&B, also said they have adjusted to accommodate the likely surge in last minute booking and cancellation. “Lodging properties need to be flexible with last minute bookings and penalty free cancellations.”

Many other businesses opened starting May 22 but with restrictions. For the Historian Bookstore is opening with a requirement for masks and limiting the number of visitors inside at any time. The Gettysburg Heritage Center will be opening its store, weekends only at first.

The Regimental Quartermaster and Jeweler’s Daughter are open. Customers will need to wear a mask at all times in the shop.

Regimental Quartermaster is allowing customers 60 years and

older to shop an hour before opening to the public. This will help to ensure everyone can get the items they need in a less-crowded environment. Their store hours are: Monday-Friday & Sunday: 10-5, Saturday: 10-6.

The Antique Center of Gettysburg, a popular source of Civil War memorabilia, reopened on Friday, May 22 on an appointment basis both for customers and vendors. The antique mall is limited to 15 guests in the shop at a time and masks are required. Some private attractions will open but many will remain closed. The Shriver House Museum opened Saturday, May 23, but will be operating with limited hours. Besides masks, sanitizers, and 6 foot separation, they are sanitizing the shop and house after each tour and limiting size of tour groups, etc. Nancie Gudmestad said, “We may have shortened hours throughout the week. We will be playing it by ear for a while.”

The Jenny Wade House museum, home of the only civilian casualty during the battle, will be opening for weekends only until Gettysburg moves into the “green” category. For now, tours will be self-guided rather than groups with a guide. The Gettysburg Tour Center will be opening and will be operating bus tours at reduced capacity for social distancing.

Gary Casteel, the sculptor who created the Longstreet statue and is preparing a series of

miniatures of Gettysburg and other monuments is open with mask requirements.

For those who come to Gettysburg for the ghosts, Ghostly Images resumed tours May 23, weekends only for now.

Mark Nesbitt Ghost Tours is holding off opening for now.

Some other businesses are remaining closed for now. Waldo’s and Co., a local coffee house, arts center, and popular gathering place, is staying closed.

Chris Lauer said “we are taking our time to make sure that we are opening in the most responsible way. … as a space that fosters community, i.e. strangers meeting strangers, tourists meeting locals, etc., we recognize that there is still some risk of spread. We have chosen to wait until the next phase of reopening and taking that time to prepare our staff and our space to mitigate any risk we can.”

The Seminary Ridge Museum, for now is “working on a plan to ensure staff, visitor, and resource safety when we reopen,” said COO Peter Miele. There is no firm reopening date.

Gettysburg isn’t just a tourist town: to a great extent, it’s also a special events town. Some events that draw large crowds (college graduation, Memorial Day parade, anniversary reenactment and Gettysburg Battlefield Preservation Association’s July 4 reenactment at Daniel Lady Farm) have already been cancelled or postponed; the future of

others is uncertain. On the other hand, Nancie Gudmestad said that Shriver House will be augmenting its “Confederates Take the Shriver House” program over July 4, “since both reenactments have been canceled … and so many people come over the holiday …”

Bike Week, which typically occurs in mid-July, is still on the schedule, as are events such as the Apple Festival and Dedication Day. Several major conferences scheduled for later in the year, including the Lincoln Forum, are currently assessing the feasibility of moving forward. Gettysburg College’s Civil War Institute, scheduled for June, was canceled, but the organizers plan a Facebook Life event at the time the conference was scheduled and, perhaps, a one day event in the fall.

The situation in Gettysburg will continue to evolve. Discussions in online Gettysburg discussion groups make it clear that there is a yearning on many people’s part to visit Gettysburg. Many people will undoubtedly agree with an adapted version of the old golf gag: a bad day at Gettysburg is better than a good day somewhere else, but it appears that the Gettysburg experience will remain a partial experience for much of the summer.

See the following links to get a more up-to-date status of guidelines.

• Cocktails to go: https://www. governor.pa.gov/newsroom/ gov-wolf-signs-cocktails-togo-bill

• Outdoor restaurant service: https://patch.com/pennsylvania/newtown-pa/pa-restaurants-can-open-outdoor-dining-rooms-june-5

• PA – red, yellow, green phase: https://www.governor.pa.gov/process-to-reopen-pennsylvania

Leon Reed is a former congressional aide, defense consultant, and US History teacher. He lives in Gettysburg, volunteers at the visitor center when it’s open, and is the author of Stories the Monuments Tell: A Photo Tour of Gettysburg, Told by its Monuments.

Ohio Private at Gettysburg Receives Medal of Honor

by Joan Wenner, J.D.Ohio soldiers were said to have fought well at Gettysburg. Included with monuments to the 25th and 75th Ohio Infantry are 16 others for cavalry regiments and artillery batteries. While most of the 300,000+ Ohioans were in the Western theatre, some 4,400 fought at Gettysburg.

There were many acts of bravery on that battlefield, both recorded and unrecorded. For example, during Pickett's Charge, when Henry Hunt, artillery chief for the Army of the Potomac, gave the order to hold their fire, the gunners waited. When they at last opened fire, one Ohio letter writer recalled, “It was like an earthquake for a couple of hours.”

Then there was a single Ohio sniper; Private Charles Stacey, who voluntarily snuck into Confederate territory on July 2, 1863, for the purpose of attacking a band of Southern sharpshooters. Alone, he remained hunkered down in a wheat field on the wrong side of the skirmish line over four hours, firing 23 shots, and taking out sharpshooters so completely it was said that not a single man in his company was harmed. Stacey wrote in a 1918 letter to his grandson, “that I don't believe any man ever had a line of battle fire at him as many times as I was fired at and live to tell of it.”

He earned the Medal of Honor for his actions. Charles Stacey died peacefully in his hometown of Norwalk, Ohio, in 1924 at age 82.

His citation reads “Voluntarily took an advanced position on the skirmish line for the purpose of ascertaining the location of Confederate sharpshooters and under heavy fire held the position

thus taken until the company of which he was a member went back to the main line.”

His headstone photo can be found at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/8363542/ charles-stacey.

Civil War Catalog

Featuring a large assortment of Civil War and Indian War autographs, accoutrements, memorabilia, medals, insignia, buttons, GAR, documents, photos, & books. Please visit our fully illustrated online catalog at www.mikebrackin.com

Free copy mail catalog

Mike Brackin

PO Box 652, Winterville, NC 28590 • 252-565-8810

In this current time period of watching how individuals react to the change of their lifestyles, jobs and lack of basic supplies, it is amazing to see the difference in actions. We all now have experiences in dealing with situations we may have never imagined being part of our lives.

Now, more than ever, we really can stand in awe of how our ancestors survived the aftermath of Civil War battles. Living in Gettysburg gives one pause on how the suffering after the battle must have been. Many stories have been written about the aftermath. We have seen books, articles, or town guides that try to relate what the Gettysburg citizens had to face in the months after the fighting.

I became interested in researching a family whose members reacted differently from each other. This led to choosing the Study family members who had settled in Gettysburg.

The Study’s were from Allegany County, Md. Their parents were Dr. John Study and Hannah Sell Study. The six children were: Jacob, David, John, Elizabeth, Catherine, and Lydia.

Three children had moved to the Gettysburg area before the battle. The first we will look at is Dr. David Study.

David first settled in Cumberland Township before he bought his home and office

The Study’s Of Gettysburg

on Baltimore Street. I find Dr. Study fascinating because we can see him depicted in the Gettysburg Cyclorama leaning over a wounded soldier beside a haystack on his sister Lydia’s farm. During the battle, his sister and her children had taken refuge in his home. I am curious why a doctor’s home would not be used as a field hospital, especially with its location on Cemetery Hill. Many words have been written about the army surgeons having a poor opinion of local doctors thus limiting their use on the battlefields, but I find it odd that they did not use a facility that had

medical supplies.

Dr. Study’s sisters both had their homes used as temporary field hospitals Maybe David did go to Lydia’s farm to give aid. Was it after the fighting had stopped? What stories were told that led Paul Philippoteaux to put him in the painting?

Dr. Study never married and eventually his home became a part of the orphanage on Baltimore Street. In the tough times after the battle, he had two nieces serve as housekeepers. David was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in 1872.

Catherine Study was born in 1809 and married John Slyder

on Sept. 25, 1838; together they moved to Gettysburg. They later bought 74 acres along Plum Run and Big Round Top. John and Catherine built a stone house and several outbuildings as they worked the farm. They had four children; William, Matilda Catherine, John, and Isaiah. On July 2, the family was told to leave the house. The Second US Sharpshooters under Colonel Homer R. Stoughton set up behind

their walls and fences, defending against the Law’s Brigade’s 14th and 47th Alabama. The Sharpshooters fell back past Big Round Top as Hood’s Division moved beyond the Union’s left. The next day Farnsworth’s Brigade moved across the farm in an ill-fated cavalry attack. The family returned to find their crops destroyed, possessions gone or damaged. The buildings were used for a few days as an

July and he helped burn the horses; the family collected the bones and sold them for fertilizer at fifty cents per one hundred pounds.

Lydia Study Leister was faced with damaged buildings, ruined crops and peach trees, bad water and needed to replace her fencing. The home was used as an aid station/hospital as well as General Meade’s headquarters.

When one thinks of all the adversities one can face in their lives, we can look back at Lydia Leister for inspiration on what can be done. Lydia replanted her crops and rebuilt her fences.

made the decision to move into town. When she learned the Association was going to tear down her addition, she had them move it next to the Dobbin house she had purchased. Later she added to this house, and it still is in use as a bed and breakfast. Lydia lived her final days there, dying on Dec. 19, 1893. She is buried in Evergreen Cemetery.

I cannot think of another who overcame more. A widow, still owing money, two children at home, her oldest son in the army and then seeing her older sister pull up stakes and move.

The Slyder family found things beyond their capability. Compensation would only be made for damages done by the Union army that were supported by receipts or by eyewitnesses. By September their farm was up for sale and the family moved to western Ohio.

Their oldest son William lost his wife, Rebecca, in 1862.

William planned to move with his parents to Ohio, but first he would marry the girl across the Emmitsburg Road, Josephine Miller.

In the Gettysburg Compiler John stated “As I intend to move to the west, I will sell on very reasonable terms.” The farm today is better known as the Granite Farm.

The last of the Study family in Gettysburg was the youngest. Lydia Study was born in 1811. She married James Leister around 1830 and they lived about 15 miles south of Gettysburg. By 1850 they moved to Greenmount, Penn. James had a drinking problem that led Lydia’s father to put her inheritance in a trust. When James died in December 1859, Lydia moved. She sold her late husband’s tools, and together with the money she inherited, bought nine acres along the Taneytown Road from Henry Bishop for nine hundred dollars.

Lydia’s son Amos enlisted in the 165th Pennsylvania regiment, infantry in 1862. This left Lydia with her two youngest living in

the home at the time of the battle.

When asked to leave on July 1st they went to David Study’s home on Baltimore Street. After the battle, they were faced with destruction. Lydia did an interview in 1865 and never mentioned one thing about the battle itself. What she saw on her nine acres was burnt into her memory.

The National Homestead at Gettysburg was an orphanage and widows home opened in October 1866, on Steinwehr Avenue on the north foot of Cemetery Hill. aid station. Remarkably, in looking at the research done by Greg Coco and Edward Richter, only three or four bodies were buried on the farm. One was identified as Colonel John A. Jones, 20th Georgia Infantry. His body was disinterred in December 1865, and shipped to his family in Columbus, Ga.

“I owed a little on my land yit, and though I’d put in two lots of wheat that year, and it was all tramped down, and I didn’t get nothing from it. The fences was all torn down, so that there wasn’t one standing, and all the rails was burnt up. One shell came into the house and knocked a bedstead all to pieces for me. The porch was all knocked down. There were seventeen dead horses on my land. The dead horse’s spoiled my spring, so I had to have my well dug.”

Amos was discharged in late

Amazingly, by 1868 Lydia doubled the size of her farm by expanding to the north for nine hundred dollars. In 1874 she constructed a two-story addition to her home where she lived until 1888.

The Battlefield Preservation Association offered her three thousand dollars for her farm. Her health was poor, and she

Anytime I face adversities I can sit back, smile, and ask myself: What would Lydia do?

Mike Shovlin is a graduate of Westminster College where he majored in history. He is currently employed by the Gettysburg Foundation as the lead Assistant at the Rupp House History Center.

The Gettysburg National Cemetery is an important part of any visitor’s experience on the battlefield. It is sobering to walk among the unique landscape architecture and understand the enormous sacrifice in lives represented by row upon row of solemn graves. Many visitors don’t realize the graves in the cemetery represent only a portion of the battle’s dead. Not only were there a significant number of solders’ remains taken home by families after the battle, but the national cemetery, according to the laws of its creation, excluded Southern casualties. The graves of Southern dead at Gettysburg would have to wait nearly a decade before the situation was properly addressed.

When the Battle of Gettysburg ended on July 3, thousands of bodies lay across 6,000 acres of trampled ground under the hot sun and pouring rain. The outcome of the conflict was a Union victory on Pennsylvania soil. Just the year before, the Pennsylvania legislature passed an act that provided for the care of her wounded and burial of her battle dead. Within days of the battle, Pennsylvania’s Gov. Andrew Curtin visited the battlefield and was appalled by the haste with which the brave dead had been buried. He appointed David Wills to carry out the requirements of the law.

Southern Dead at Gettysburg

Will’s first report emphasized the rapidly deteriorating condition of the temporary graves. Curtin authorized Wills to arrange for the exhumation and transportation of all Pennsylvanians killed in the battle. At least 700 bodies were shipped home in pine coffins to their families, but the decaying bodies created a terrible stench and a health risk. By the end of July, the military authorities ordered the cessation of further exhumations.

What we know today as the national cemetery system was already in place by 1863; nearly a dozen cemeteries were established in 1862. Those cemeteries, like Pennsylvania’s, allowed only for the burial of “loyal dead,” thereby automatically ruling out a solution for Confederate dead simply because they fought on behalf of states in rebellion and therefore were not “loyal.” Wills eventually acquired the 17 acres of ground that provided for establishment of the Soldiers National Cemetery at Gettysburg.

Union dead were exhumed from October 1863 through March 1864. During the grueling work of reburying the dead, a dedication ceremony was held at which President Lincoln delivered his immortal address.

Throughout the process of gathering and reburying the Union dead in their newly dedicated national cemetery, Southern dead remained on the field, many in

unmarked graves or with identification markers rapidly becoming illegible. Fortunately, two individuals, Drs. J. W. C. O’Neal and Rufus Weaver, walked the fields and recorded as many names as they were able to make out. Weaver eventually took a much more active part in removing Southern dead from Gettysburg.

As plans were underway for dedicating the national cemetery in November 1863, local attorney David McConaughy received an inquiry from Governor Andrew Curtin who expressed an interest in knowing how much it would cost to remove and rebury the Southern dead. Curtin’s interest was inspired by the potential for bad publicity resulting from the large crowds visiting the battlefield for the cemetery’s dedication and seeing the poor condition of Confederate graves. McConaughy suggested that, although he was aware of a rumor that Southern sympathizers were raising funds to create a cemetery for their dead, it might be better if the government took control of the situation to prevent displays of disloyalty in the process. McConaughy gave assurances that Confederate graves would be properly covered by the dedication’s date. However, no further plans were forthcoming from the Pennsylvania legislature regarding removal of Confederate dead. There were other futile discussions on the matter as well. In February 1864, a newspaper article lamented the condition of the graves and the difficulty farmers would soon encounter trying to cultivate their fields. It went on to suggest that common decency

should prevail so that Southern families and friends of the fallen could have a place to visit when the war ended, to remember those they had lost. Later that spring, New York Governor Horatio Seymour contacted Gettysburg attorney Moses McClean offering to raise funds to give decent burials to Southern battle dead but those plans also failed to materialize. Although the topic appeared in local and regional papers from time to time, no further official action was discussed or taken.

When the war ended, the Federal government developed a very ambitious project to recover all Union dead scattered on battlefields across the land. The arduous task was able to be accomplished because the South was under Federal control. It was largely completed by late 1870, when more than 300,000 Northern soldiers were reburied in 72 newly established national cemeteries. Southerners hoped the Federal government would eventually include all the battle dead that were as yet improperly buried, however, in spite of discussions to that effect, Confederate soldiers were ultimately excluded from the government’s recovery efforts.

Meanwhile, Southern newspapers lamented the failure of the Federal government to include Confederate soldiers, blaming it on partisan politics. A Richmond paper’s message regarding Gettysburg was that while Northerners set the example of honoring their dead with eulogies, monuments, and great expenditures of money in turf, flowers, and plants, “the poor

southerner was cast aside from the scene, sleeping uncared for in his narrow and neglected house.” It went on to say that the expense for the Gettysburg ceremony was paid in part by Southerners but radicals censured the Southern people for wishing to take care of their own dead. The article ended by stating it was the Southerners’ right and duty to look after their own boys who died for their cause.

When it became clear that no help would be forthcoming from Federal authorities or the Northern people, work commenced under the auspices of Ladies Memorial Associations to raise funds to locate and identify Southern soldiers’ graves and care for them. They earnestly and faithfully carried out their work on battlefields within their own states throughout the late 1860s, but they had no organized plans for recovering their lost soldiers at Gettysburg.

At the 1869 dedication of the Soldiers National Monument, keynote speaker General George Meade included the following statement in his remarks: “When I contemplate this field, I see here and there the marks of hastily dug trenches in which repose the dead against whom we fought…. Above them a bit of plank indicates simply that these remains of the fallen were hurriedly laid there by soldiers who met them in battle. Why should we not collect them in some suitable place? In all civilized countries it is the usage to bury the dead with decency and respect, and even to fallen enemies respectful burial is accorded in death. I earnestly

hope that this suggestion may have some influence throughout our broad land, for this is only one of a hundred crowded battlefields.” Meade’s words inspired no further action on the part of Gettysburg citizens, state officials, or Federal authorities.

This was soon followed by a protest against the neglect of Confederate dead, delivered during a speech by Henry Ward Beecher. He said, “Can it be possible that a great and generous nation will much longer suffer the Confederate dead to lie disheveled in such utter and contemptuous neglect?”

The last straw that spurred initiative among Southerners to reclaim their Gettysburg dead came in March 1870, when a bill was passed by Maryland’s Senate to establish a cemetery near Hagerstown for the internment of Confederate dead from the battles of Antietam, South Mountain, and Gettysburg. The senate committee reported that the incorporation of the Antietam National Cemetery provided for including Confederate dead but in 1869 trustees of that cemetery refused to do so. Consequently, the senate took the initiative to establish a burial ground within

the recently established Rose Hill Cemetery that became known as Washington Confederate Cemetery. However, its stated purpose was to rebury the dead from battles and skirmishes in western Maryland. This included the dead from Antietam, South Mountain, and areas that saw skirmishes within the state in which Lee’s retreating army were engaged, thus excluding the bulk of Confederate dead still in Gettysburg.

At this point, the Hollywood Memorial Association took the lead. They appealed to each Southern state whose soldiers

still lay at Gettysburg to raise the necessary funds. The directors also appealed to General Lee to support their mission. Lee at first declined, not wishing to put himself into the public arena because he thought it would detract from the cause. He finally relented and issued a letter from Lexington, Va., on March 8, 1870, that was published in Southern newspapers. It read, “I have felt great interest in the success of the scheme of the Hollywood Memorial Association of Richmond for the removal of the Confederate dead at Gettysburg, since learning of the neglect of their remains on the battlefield. I hope that sufficient funds may be collected by the association that it will receive the grateful thanks of the humane and benevolent. May I request you to apply the enclosed amount [$125] to this object.” This endorsement by General Lee spurred the Ladies Memorial Associations to redouble their efforts in their respective states but funds were slow in coming from poverty stricken Southern states. In what could be described in today’s world as public shaming, a Charleston newspaper chided its citizens with the headline, “Nothing from South Carolina.”

The article enumerated the funds raised by other states that totaled just over $1,000 by April 1870, the majority of which was raised in Virginia; and stated, “So far, only a miserable sum has been collected for the purpose, and it will be noticed that there is nothing from South Carolina….the state which poured out her blood like water in the cause of the south, has, up to this time, given nothing for preserving from insult and pollution the mouldering bones of the gallant men who fell in the mighty conflict in Pennsylvania. Now that the truth is known, this reproach will not be allowed to rest upon our people.”

In early 1871, the long-awaited process to remove Confederate dead from Gettysburg was finally begun with a request by the Ladies Memorial Association of Charleston, S.C. Although Samuel Weaver, who was instrumental in removing Union dead to the National Cemetery in Gettysburg, was the initial recipient of the request, his untimely death in a railroad accident left his son, Dr. Rufus B. Weaver to take up the task. By Memorial Day, May 10, 1871, Weaver had shipped the

It is some of the most sacred ground in America, made so by the men who fought and died there, regardless of whether they were from the North or the South.

Further Reading:

One of three unknown sections in the Gettysburg National Cemetery where Confederate bodies found on Culp’s Hill, mistakenly thought to be Union, were buried in 1899.

bodies of 80 South Carolina soldiers to Charleston where they were buried with ceremonies in Magnolia Cemetery. His work on behalf of the Memorial Association of Charleston led to requests from other like associations. Ultimately, in response to requests from Ladies Memorial Associations and individuals during the summers of 1871, 1872, and 1873, Weaver exhumed and shipped 3,253 sets of Confederate remains to Charleston, S.C. (80); Savannah, Ga. (101); Raleigh, N.C. (137); and Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Va. (2,935). He also exhumed the bodies of 73 individuals that were sent to various locations throughout the south. Each shipment was lovingly received and reinterred with solemn and patriotic ceremonies. Weaver

received far less in compensation than was personally expended by his efforts. As of 1887 he was still owed over $11,000, a sum he most likely never received.

A question, often asked by visitors who are told about the removal of the Confederate dead from the battlefield, is whether any bodies remain on the field. The affirmative answer allows historians to impress upon visitors the fact that the Gettysburg battlefield is indeed hallowed ground, not just for the battle that was fought there but also because there are still soldiers’ remains there. Dr. Weaver was not able to remove all the Confederate dead nor did he attempt to do so. Some bodies buried in out-of-the way places were left undisturbed. Some were simply not found. Some were found over the years

Magnolia Cemetery, Charleston, S.C., where some Gettysburg dead now repose. as farming, the building of roads, and other improvements required ground to be disturbed. A number of discoveries are recorded in the reports of governing bodies over the years. For example, it is known that approximately 200 soldiers were buried on the 11th Corps Hospital site at the George Spangler Farm; conflicting records report that between 4 and 20 of them were Confederates. Yet there is no record of their removal in Dr. Weaver’s notes.

During War Department years (1895–1933), Park Commissioner William Robbins noted in his journal in September 1899, that one crew working on the battlefield “found on the southwestern side of Culp’s Hill about 17 bodies of Union soldiers. We had the remains put in boxes and sent to the Custodian of the National Cemetery to be buried there among the unknown.” The discovery was reported in regional newspapers which prompted David Monat, a veteran of the 29th Penn. Volunteers to write to Col. John P. Nicholson, head of the Park Commission, to explain why he felt the bodies were actually Confederate. He shared that on July 4, 1863, he and his

fellow soldiers filled two burial trenches with Confederate bodies, 13 in one trench and 16 or 17 in the other. He said they covered the bodies with their old (US) blankets because they picked up new ones the day before from the Maryland Eastern Shore troops. This explained why the bodies were originally thought to be Union. Monat drew a crude map to show where the bodies were.

There were a number of other incidents in which bodies, both Union and Confederate, were found on the field over the years. Some were sent to the Confederate Cemetery in Hagerstown, some to the National Cemetery, and some were simply moved out of the way and reburied. The most recent discovery was a partial skeleton found in 1996 in the side hill of the railroad cut on the first day’s field. It was thought to be that of a Confederate after the remains we analyzed by Smithsonian archaeologists. Those remains rest in the Gettysburg National Cemetery today.

It is this author’s hope that my article has reinforced the need to preserve the Gettysburg Battlefield for future generations.

Early Photography at Gettysburg, by William Frassanito (1995); A Strange and Blighted Land, by Gregory Coco (1995); Wasted Valor, by Gregory Coco (1990); “The Removal of the Confederate Dead from Gettysburg,” by Edward Richter in Gettysburg Magazine, January 1, 1990; “The Aftermath and Recovery of Gettysburg,” Part 2 by Eric Campbell in Gettysburg Magazine, July 1, 1994; Richmond Dispatch and The Charleston News, various dates, 1866–1871; “Journal of Major William Robbins,” Gettysburg National Park Commission, GNMP Archives.

Sue Boardman, a Gettysburg Licensed Battlefield Guide since 2001, is a two-time recipient of the Superintendent’s Award for Excellence in Guiding. Sue is a recognized expert of not only the Battle of Gettysburg but also the National Park’s early history including its many monuments and the National Cemetery.

Sue is Director Emeritus of the Gettysburg Foundation’s Leadership Program. Her program, In the Footsteps of Leaders has been well-received by corporate, government, non-profit and educational groups.

Sue is a native of Danville, Penn., and an Honors Graduate from Penn State/Geisinger Medical Center School of Nursing and attended Bloomsburg University. A 23-year career as an ER nurse preceded her career at Gettysburg. Sue served as President of the historic Evergreen Cemetery Association and is currently on the Board of Trustees. She has worked as an adjunct instructor for Harrisburg Area Community College and Susquehanna University.

Pandemic affects history profession in multitude of ways

by Chris MackowskiCanceled talks, postponed tours, lost book sales, closed facilities, Civil War historians have dealt with an array of problems since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic.

“I’ve had to wave off travel plans, conferences and speaking engagements have been put off or cancelled, publication schedules are up in the air, and I’m doing much more over video and Zoom than I had before,” says Chris Kolakowski, chief historian for Emerging Civil War. “My colleagues and I have found ourselves looking to historical examples for perspective and strength during these days.”

“It is truly a historic event,” says Kevin Pawlak, site manager at the Bristoe Station Battlefield and Ben Lomond Historic Site in Prince William County, Va. “As historians, it is stunning to live in a time sure to be studied by humans decades and centuries from now.”

Pawlak and Kolakowski are two of nearly three-dozen Emerging Civil War historians, representing a broad cross-section of the profession: historic site supervisors, tour guides, authors, academics, National Park Service rangers, museum employees, volunteers, and independent historians. Their stories offer a glimpse into the

ways the virus has impacted the way historians do history.

“It has changed how we share history with others,” Pawlak says.

“I empathize with anyone who’s trying to scratch out a job in history right now,” says Edward Alexander, a historical cartographer who owns Make Me a Map (makemeamapllc.com). A former park ranger, he now describes history as “a hobby that also provides freelancing opportunities.”

“That being said, the ways in which I still interact with the public history world is being impacted,” Alexander explains.

“One tour I had scheduled for the summer has been postponed already and another might follow. Map work has also slowed down. A few projects that I’m involved with are seeing delays, and new jobs are not coming in as fast. I am trying to use the extra time I have at home to tinker with new design styles and work on the business side of mapmaking.”

Historians have lost speaking gigs at conferences, Civil War Roundtables, and historical societies, and tours have been cancelled. This, in turn, has led to lost revenue, in the thousands of dollars for some people, as well as lost book sales.

“Historic sites and battlefields are closed for programming and public interaction,” Pawlak adds.

That often means seasonal hiring is frozen and paid internships are not available. Such closures likewise impact book sales.

For Ryan Quint, who works as a costumed interpreter at a site in Williamsburg, Va., such closures mean life is on hold. “The museum I work for has been closed for months,” he says. “There is a tentative timeline to reopen, but no one is sure.”

Kolakowski, who works as director of the Wisconsin Veterans Museum, had been on the job for just two and a half months when the pandemic struck. “For two solid weeks, March 11-25, I faced a daily-changing situation, while leading a team that I was still getting to know and they were getting to know me,” he says. “We successfully shifted into dispersed operations and started doing many things, including programs, online. It required tough decisions to be made quickly, similar to crisis reactions on battlefields; indeed, it was a lesson about leadership in a dynamic and uncertain environment.”

Kolakowski noted an important collateral result, though. “An interesting, and quite positive, side effect is that my staff and I have bonded faster and more thoroughly than we may have in more normal times,” he says.

Bert Dunkerly, who works as a historian for Richmond National Battlefield Park, faced a similar transition. “We really scrambled at first trying to transition to teleworking,” he says. “Our jobs involve working with the public, being out in the field, and being on site. With park laptops, we are doing things digitally now, research and online presentations. We are doing a series of Facebook Live talks, as well as pre-recorded videos for schools and the general public. We’re doing more with Twitter and Instagram.” Other national parks have responded in similar fashion, with programming varying from park to park as technical capabilities and employee availability have allowed.

“We’re not sure what the summer will look like,” Dunkerly admits, “but I think we’ve made a good transition to keep our audiences engaged the best we can.”

Academics also had to make the shift to online. “I have not seen my students in nearly two months,” says Derek Maxfield, an assistant professor at Genesee Community College in Batavia, N.Y., as the end of the semester was bearing down. He’s had to operate mostly by using software that allows him to post class lessons and materials to an online

space that students can access and then post their homework there in response. Both professor and students had to make adjustments to their college experience.

“I am trying to be as flexible as possible,” Maxfield adds.

Maxfield also has been trying to take advantage of social media to promote his new book, Hellmira: The North’s Most Infamous Civil War Prison, Elmira, NY, part of the Emerging Civil War Series. “The book is out, thankfully, but all the presentations and signings are on hold,” he says.

Zachery A. Fry, Ph.D., also had to transition his classes to an online format, “which has required an unprecedented level of administrative headache,” he admits. Fry is an assistant professor in the Department of Military History at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Ft. Belvoir, Va. He’s also author of the newly released book A Republic in the Ranks: Loyalty and Disunion in the Army of the Potomac.

“The pandemic has also closed all brick-and-mortar bookstores, so the release of A Republic in the Ranks was marred by a complete absence of any actual lectures or signings,” he says. “I hope to make up for lost ground in the fall, but the Civil War publishing world is so fast-paced and dynamic that there’s really no telling how that will go. In the meantime, I’m trying to maximize the number of virtual interviews and blog entries to broaden awareness of the book.”

Along with canceled talks, delays in book publications and promotions were among the most common, and, says author Dwight Hughes, “the most serious repercussion,” cited by historians.

Leon Reed, a developmental editor for the Emerging Civil War Series, had a book published in December, No Greater Calamity for the Country: North-South Conflict, Secession, and the Onset of Civil War. The book, he thought, “had extraordinary potential for personal appearances, not only at the ‘traditional’ Civil War and historical society events, but also at stamp collector groups. The book makes heavy use of patriotic envelopes of the time period. I’ve had a book launch party as well as a dozen speaking engagements or book signings cancelled or delayed; sales of all my books are pretty much limited to online sources.”

`Like Maxfield and Fry, Reed has tried to push the book on the internet but hasn’t “had a lot of luck goosing online sales.” He

adds, though, “One consolation is that I’ve been invited to do a regular series of online ‘stamp chats’ by the American Philatelic Society.”

The pandemic has also impacted historians’ research and writing time. “I had research trips scheduled to several research libraries in New York and to the Army Heritage Center in Carlisle.... So these research efforts are deferred,” Reed said.

Jon-Erik Gilot is one such archivist who’s been shut out of his archives. “This week marks my seventh week home from work,” he said on April 30. “My wife is considered ‘essential’ and has remained working full time, which leaves me home with our two daughters, ages 8 and 2, who have likewise been home from school for the past seven weeks. I juggle my time between the two as both a teacher and an entertainer. Needless to say by the time they go to bed I’m exhausted and my research and writing have been dragging. I’ve started to wake up early, before the girls, and do some writing then. The quarantine has forced me to find small pockets of time with which to work.”

Others, like Reed, have found “PLENTY of time to write.” Quint has seen that as a major positive. “The quarantine has allowed me to finish my manuscript, which I was working on for nearly three years,” he says. Doug Crenshaw, who volunteers for Richmond National Battlefield, has also “found time to do a lot of research and writing.”

“I’m also preparing for a major tour in the fall,” Crenshaw adds. “And I have ordered a bunch of books and am enjoying burning through them. On a non-historical note, there has been a lot of time to take long walks with my wife, and these have been fun.”

Some historians, though, have faced more challenging personal situations. “I was supposed to visit family in Pennsylvania and New Mexico, both canceled,” reveals Dunkerly. “In fact, I don’t know when I’ll get to visit family, partially because I don’t want to expose them as they’re older and at risk. Do I just go to help them out, or wait till things are better, while they keep going to the grocery and pharmacy? No easy answer.”

Quint, meanwhile, has a family thick in the COVID fight. “With both of my parents on the frontlines of public healthcare, I could not be prouder of what they have done, and will continue to do, to combat this pandemic,” he says.

“In the grand scheme of things, cancelled book talks are minuscule in the list of problems.”

Many historians have embraced the pandemic as an opportunity rather than a problem. As examples, virtual tours, YouTube videos, Zoom interviews, ranger talks, and Facebook groups have exploded online since the pandemic began.

Phill Greenwalt, a National Park Service historian who’s also the chief historian for Emerging Revolutionary War, says the pandemic inspired his Rev War colleagues to have an online chat they unofficially call ‘Rev War Revelry.’ The public is invited to watch and comment. “We discuss in a more informal way a topic while we drink our favorite brew,” Greenwalt explains. “It’s a kind of virtual happy hour for historians. So, that has been something positive, using technology to continue to talk and share history.”

Pawlak sees such initiatives as good adaptations. “I can’t help but notice how this challenge has made history more accessible,” he says. “The abundance (perhaps over-abundance) of online talks, interviews, programs, and articles has brought history programs to people who live hundreds of miles from the hosting

organizations. It seems that these efforts have met with success and a multitude of followers. While it’s been difficult to take in all of these programs, we have all been able to attend more from our homes than we could if these programs were held all across the country and not online. Historians have met the task of educating our public in this time of social distancing.”

For all the problems individual historians have struggled with since the pandemic began, the profession itself has largely risen to the challenge.

Chris Mackowski teaches writing in the Jandoli School of Communication at St. Bonaventure University. He is the editor-in-chief of Emerging Civil War (www.emergingcivilwar.com) and the historian-in-residence at Stevenson Ridge, a historic property on the Spotsylvania battlefield. Chris has authored or co-authored more than a dozen books on the Civil War and frequently contributes to the major Civil War magazines. Prior to his career as a professor and writer, he was an award-winning journalist.

Some thoughts on the Henry

In the years following the Civil War, a lot of folklore regarding small arms became part of the American story. One of these tales, regarding the Henry rifle, provided the information that President Abraham Lincoln had test fired the Henry in the summer of 1861. The origin of the story was apparently the faulty memory of one William A. Stoddard, a secretary in the White House given to latter day self-promotion. It was probably inspired by Lincoln’s actual test firing of the Spencer rifle. That event was also misinterpreted after the war, but testing the Henry never happened.

The lever action, fifteen shot (sixteen if one counts a round in the chamber) Henry, a perfected version of the Volcanic repeating arms of the 1850s, was invented by B. Tyler Henry, works superintendent of Oliver Winchester’s New Haven Arms Company, that purchased the patent from Henry. The Henry, patented in 1860, was a major advance in firearms design, essentially due to its use of a .44 caliber self-contained rimfire cartridge with powder, projectile, and primer all in one package.

Oliver Winchester, more of a marketing than a technical expert, had promoted the troubled Volcanic arms as providing “every quality requisite in such a

weapon” in an 1858 story he planted in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. In an alleged testimonial, he included quotes by a purchaser of a Volcanic handgun, quotes that claimed the gun was “the ne plus ultra of Repeating or Revolving Arms and far superior in many respects to Colt’s much extolled revolver.” Another bit of hyperbolic advertising referred to the Volcanic as “the most powerful and effective weapon of defense ever invented.”

Winchester was well aware of the Henry’s significance and its superiority in a number of ways to any other rifle on the market in 1860. The onset of the Civil War seemed to provide a ready market for the Henry, and Winchester tried to interest the Chief of Ordnance, General James W. Ripley, in the gun. The spring and summer of 1861, however, was not the right time frame to adopt innovative but essentially unproven arms and Ripley, condemned by many for his conservative view of new products, was actually being reasonably astute.

Winchester did not hesitate to go over Ripley’s head, however, and sent presentation grade Henrys to administration officials, including Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, a fellow Connecticut man. A naval officer tested the Henry in May 1862, and found it performed well in accuracy and endurance tests. There were other favorable tests, but orders were

by Joe Bilbynot forthcoming. Had those orders come, however, Winchester would not have been able to fill them. Who actually manufactured the first 500 Henrys, with an iron rather than the familiar bronze frame, is murky. One historian believes Colt manufactured them, but there is no conclusive evidence for that, although Winchester did have a contract with Colt during that period, mostly for machinery, The first Henry rifles were not on the market until the summer of 1862. The guns were shipped to dealers in the Midwest and Kentucky, a state in considerable internal strife. Secretary of War William Stanton personally sent one to pro-Union Louisville Journal editor George D. Prentice. Prentice praised the gun to the skies, writing that his Henry was “the most efficient and beautiful rifle we ever saw,” adding that a shooter with one was the equivalent of “fifteen men armed with regular guns.” Although it is not widely known, there were Henrys, privately purchased from dealers in Kentucky, that ended up in the hands of Confederate guerillas and the first Henry shots fired in the Civil War were probably fired by Rebels in Kentucky, Henry production was never extensive, By October 1862, only 900 Henrys had been manufactured. By late 1864, Henry production peaked at 290 rifles per month, and a total of 13,000 were

produced through 1866. Most were scattered throughout the Union armies by 1865.

The vast majority of Henry rifles used in combat during the Civil War were privately purchased, or captured.

The only Henrys bought by government contract were those purchased for Colonel Lafayette Baker’s 1st DC cavalry. Baker, whose special unit was intended to be used in counter-guerilla and military police duties in addition to secret service operations, wanted the very best small arms available. He initially ordered 300 Henrys, but General Ripley arbitrarily cut the order to 240 and then 120 rifles. Through some back door negotiations, the number was raised back to 241 although many of them were kept in the government arsenal in Washington. As Baker’s unit, mostly recruited in Maine, grew, he petitioned for more Henrys and, fortunately for him, Ripley had been replaced by General Ramsey. In the end, Winchester shipped an additional 800 rifles to Washington by the summer of 1864.

Ironically, some of these guns, captured from the 1st DC in fighting around Richmond, ended up in the hands of Confederate cavalrymen in the Shenandoah Valley during the 1864 campaign and some were reportedly later carried by Jefferson Davis’ bodyguards when the Confederate president fled Richmond in April 1865. Many remained in the Washington Arsenal as the war wound down and were offered to “Veteran Volunteers,” soldiers who reenlisted after having served three years.

The Spencer repeating rifle, rather than the Henry, was purchased in great numbers by the government during the Civil War, but in the end, the Henry’s descendants, from the Winchester Model 1866 on down, secured a dominant share of the civilian market.

Joseph G. Bilby received his BA and MA degrees in history from Seton Hall University and served as a lieutenant in the 1st Infantry Division in 1966–1967. He is Assistant Curator of the New Jersey National Guard and Militia Museum, a freelance writer and historical consultant and author or editor of 21 books and over 400 articles on N.J. and military history and firearms. He is also publications editor for the N.J. Civil War 150 Committee and edited the award winning New Jersey Goes to War. His latest book, New Jersey: A Military History, was published by Westholme Publishing in 2017. He has received an award for contributions to Monmouth County (N.J.) history and an Award of Merit from the N.J. Historical Commission for contributions to the state’s military history. He can be contacted by email at jgbilby44@aol.com.

Nobody even comes close to building a Civil War tent with as much attention to reinforcing the stress areas as Panther. Our extra heavy duty reinforcing is just one of the added features that makes Panther tentage the best you can buy!

NEWS

Gettysburg Foundation Appoints Five New Members

to Board of Directors and New Chair of the Board

GETTYSBURG, Pa.—At its May meeting, the Gettysburg Foundation Board of Directors welcomed five new Directors, honored three Directors with emeritus status, and approved the appointment of its new board chair.

Joining the Foundation’s Board of Directors for a three-year term are Cynthia Hill; Thavolia Glymph, Ph.D.; Hal Kushner, M.D.; Richard Morin, and Charles ‘Cliff’ Bream.

“We are delighted to add five new directors to the Board of the Gettysburg Foundation, each with a unique set of experiences that strengthen our diversity and governance,” said Eric B. Schultz, outgoing chair.

Cynthia D. Hill, a former Board member and Gettysburg Friend since 1996, retired as Chief Program Officer of the District of Columbia Bar, after working over three decades to expand its programs and develop its strategy. Hill also served as Director of the Election Services and Litigation Division of the League of Women Voters Education Fund. She holds a Juris Doctor degree from Georgetown University Law Center.

Thavolia Glymph, Ph.D., professor of history and law at Duke University, specializes in nineteenth-century social history in the U.S. South. Glymph is the author of Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household and The Women’s Fight: The Civil War’s

Battles for Home, Freedom, and Nation. She is an Organization of American Historians Distinguished Lecturer, an elected member of the Society of American Historians, the American Antiquarian Society, and currently serves as the 86th President of the Southern Historical Association.

Hal Kushner, M.D., served in the U.S. Army from 1965 to 1977 as military flight surgeon, retiring from the Army Reserve in 1986 as a colonel. Dr. Kushner spent five-and-a-half years as a POW in Vietnam. He received the Silver Star, the Soldiers’ Medal, the Bronze Star, the Air Medal, 3rd award, the Purple Heart, 3rd award, the Army Commendation Medal, and was inducted into the Army Aviation Hall of Fame in April 2001. Now an accomplished ophthalmologist in Daytona Beach, Fla., Dr. Kushner has served as a visiting surgeon in Peru, Turkey, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, India, and Africa.

Richard A. Morin retired as the Executive Vice President for Finance and Administration and Chief Financial Officer after nearly two decades with Cognex, a leading global provider of machine vision software products. Morin is a Certified Public Accountant. He serves on several non-profit boards, including the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Foundation.

Charles “Cliff” Bream, whose family goes back eight generations in Adams County, is a seasoned executive and turnaround expert with more than 30 years of experience leading companies in the telecommunications, computer, office products, and packaged

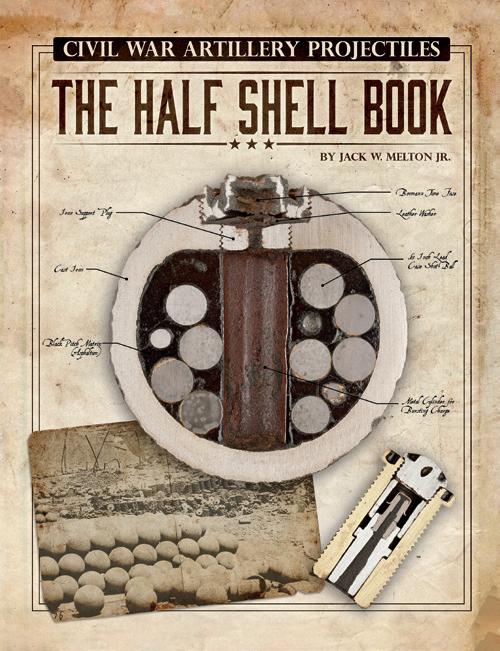

Civil War Artillery Book

392 page, full-color book, Civil War Artillery Projectiles – The Half Shell Book.

For more information and how to order visit the website www. ArtillerymanMagazine.com or call 800-777-1862.

$89.95 + $8 media mail for the standard edition.

goods sectors, including Xerox and Epson.

“Richard and Cliff are both enthusiastic citizen-historians who also bring deep business acumen to our board,” Schultz said.

Members of the Gettysburg Foundation Board of Directors serve a three-year term and are eligible to serve three consecutive terms.

“History, law, strategy, education, program development, business expertise—from New England, the Southeast, and the West Coast. This is an extraordinary class of new directors committed to the mission of the Gettysburg National Military Park and our Foundation,” Schultz added.

The Board also named Michael Higgins, Sandra Mellon, and George Will, Ph.D., as Director Emeriti.

“Mike, Sandy, and George have all made substantial contributions to the Foundation over the last decade,” Schultz said. “We look forward to their continued close involvement in our mission.”

Completing his seventh year as a Director and third as Board Chair, Schultz was elected at the May meeting to the class of 2023 emeriti.

“I believe in the work of the Foundation and the Gettysburg National Military Park and look

forward to supporting Dr. Moen and our new Board,” Schultz added.

Schultz is the former Chair and CEO of Sensitech, a former CEOpartner with Ascent Ventures and author of four books, including (with Michael Tougias) King Philip’s War: The History of America’s Forgotten Conflict and most recently, Innovation on Tap: Stories of Entrepreneurship from the Cotton Gin to Broadway’s Hamilton.

The Foundation’s Board of Directors approved its next Chair, James Hanni. Hanni, a current Board member and member of the Friends of Gettysburg, is the retired Vice President of Public Affairs of AAA Club Alliance, Inc., an affiliate club of the American Automobile Association. Previously, he served as the Chair of the Gettysburg Foundation’s Membership Committee and Board Secretary.

“We are so pleased to be led by Jim Hanni, who brings both corporate and non-profit experience and years of passion for this place as a long-standing Friend of Gettysburg,” said Dr. Matthew Moen, President of the Foundation. “We are so grateful for three years of dedicated service by outgoing Board Chair, Eric Schultz, who ably steered us through a time of transition for the Park and the Foundation

alike, helping drive a host of preservation and education achievements.”

“I am so honored to be involved with the Gettysburg Foundation and serve in the shadow of the legacy that the original Board, under the leadership of Bob and Anne Kinsley, launched nearly 15 years ago,” said Hanni. “The partnership created between the National Park Service and the Gettysburg Foundation to ‘enhance the preservation and understanding of the heritage and lasting significance of Gettysburg and the National Parks,’ has been abundantly fruitful for Gettysburg’s parks. We look, with confidence and pride, for new ways to support the Park in the pursuit of the mission. Our Board looks forward to finding those pathways of support together with the Park.” At the meeting, the Board of Directors also ratified its Executive Committee members.

• James R. Hanni, Chair

• Matthew C. Moen, Ph.D., President and CEO

• W. Craig Bashein, Vice Chair

• Barbara J. Finfrock, Vice Chair

• A.J. Kazimi, Secretary

• Shanon R. Toal, Jr., Treasurer

The Gettysburg Foundation Board of Directors is scheduled to hold its next meeting in the

Civil War Artillery Book

New 392 page, full-color book, Civil War Artillery Projectiles – The Half Shell Book.

For more information and how to order visit the website www.ArtillerymanMagazine. com or call 800-777-1862. $89.95 + $8 media mail for the standard edition.

The 2020 Civil War Dealers Directory is out. To view or download a free copy: www.civilwardealers.com/dealers.htm

100 Significant Civil War Photographs: Atlanta Campaign collection of George Barnard’s camera work. Most of the photographs are from Barnard’s time in Atlanta, mid-September to mid-November 1864, during the Federal occupation of the city. With this volume, Stephen Davis advances the scholarly literature of Barnardiana.

$19.95 + $3.50 shipping

128 pages, photographs, maps, bibliography. $19.95 + $3.50 shipping. Softbound. ISBN: 978-1-61850-151-6. www.HistoricalPubs.com. Order online at www.HistoricalPubs.com or call 800-777-1862

“The moment I saw them, I knew we should give them Fredericksburg,” declared Captain Henry Livermore Abbott, recalling when he spotted the Confederate infantry advancing to attack the Union center the afternoon of July 3, 1863. The Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble Charge moved across nearly a mile of open fields, destined to meet a devastating fate. Some Union soldiers waiting along the stonewall could have used their experience six months earlier to warn the gray-clad troops, but it was no time for warnings. The soldiers of the 20th Massachusetts recognized a moment for revenge, a change to pay back the losses suffered on the plains in front of Marye’s Heights.

At both battles, the 20th Massachusetts, “The Harvard Regiment,” fought in the Third Brigade, Second Division, II Corps. Formed in 1861 and initially including many university graduates and students, the volunteer unit served until the end of the war and suffered the most casualties of any Massachusetts regiment. The unit had battle experience from Ball’s Bluff, the Peninsula Campaign, and Antietam by December 1862 when they stood on Stafford Heights, looking across the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg, an open plain, and Marye’s Heights rising to the west.

On Dec. 11, 1862, the 20th crossed the Rappahannock under fire and help secure a Union foothold on the Fredericksburg side, pushing Barksdale’s Confederates back and allowing completion of the pontoon bridge at the Upper Crossing. Forming on Hawke Street, the regiment received orders to “clear the street leading from the bridge at all hazards.” Supported by two other regiments, the Harvard Boys plunged into the fight, driving back the Confederates and securing the Federal grip at the Upper Crossing. That night and the following day some tended to the wounded, others took advantage of the situation to plunder homes or have impromptu concerts on pianos left behind by fleeing civilians. Another day of combat dawned on December 13, one that would be etched in the minds of the regiment’s survivors.

From Marye’s Heights, standing west of Fredericksburg’s close streets, Colonel Edward

“Give Them Fredericksburg”: The 20th Massachusetts at Gettysburg

P. Alexander’s guns trained a crossfire over open ground that Union infantry would have to cross to reach the high ground. Below the heights, in a sunken road, Confederate infantry from Longstreet’s Corps waited to add their rifle fire to the defense.

French and Hancock’s Divisions from the II Corps made the early assaults. Howard’s Division, including the Third Brigade with the 20th Massachusetts followed in the footsteps of their unsuccessful attacks. Around 1p.m., their brigade went into action, deploying in line of battle after crossing the infamous millrace that cut across the open ground.

Anchoring on William Street, the 20th Massachusetts formed the brigade’s right flank with their attack aimed at rifle pits along the heights, not the actual Sunken Road further down the line.

The Harvard Boys advanced about sixty yards under artillery and rifle fire, then stood fast, and returned fire. Other regiments in the brigade fell back, and for a little while the 20th stood alone, unwilling to retreat and suffering heavy casualties. “The Twentieth Massachusetts stood firm and returned the fire of the enemy, till I had, with the assistance of my staff and other officers, reformed the line and commenced a second advance,” recalled Colonel Hall, the brigade’s commander.

Twice, the regiment advanced. The 20th “showed the matchless courage and discipline,” but courage and training would not prevail against the deadly crossfire; the brigade finally fell back to the millrace where they held a position into the night. Despite the risks, some soldiers crawled back into the field and dragged wounded comrades to safety under the cover of darkness. According to their official records, the regiment lost 163, over half the 307 men they had in the ranks when the battle began; the majority were lost in the assault on Marye’s Heights.

Nearly six months later, the 20th Massachusetts laid low on July 3, 1863, as a terrific cannonade shook the ground. Across open fields, Alexander’s Confederate artillery again pounded the Union army, but this time the roles were reversed. Federal troops waited in defense; the Confederates could make the attack.

Captain Henry L. Abbott described the afternoon in his battle report: “After the cessation of the enemy’s artillery fire, their

infantry advanced in large force. The men were kept lying on their bellies, without firing a shot, until. . .the enemy having got within 3 or 4 rods of us, when the regiment rose up and delivered two or three volleys, which broke the rebel regiment opposite us entire to pieces, leaving only scattered groups. When the enemy’s advance was first checked by our fire, they tried to return it, but with little effect, hitting only 4 or 5 men. We were feeling all the enthusiasm of victory, the men shouting out, “Fredericksburg,” imagining the victory as complete as everywhere else as it was in front for the Third Brigade.”

However, disaster loomed for the Union line as Confederate units broke through. Quickly, the officers of 20th Massachusetts repositioned the men, where “the enemy poured in a severe musketry fire, and at the clump of trees they burst also several shells, so that our loss was very heavy, more than half the enlisted men of the regiment being killed or disabled while there remained but 3 our of 13 officers. .

.

. Notwithstanding these adverse circumstances, the men of this command kept so well together that after the contest near the trees, which last half an hour or so was ended, I was enabled to collect. . . nearly all the surviving men of the regiment and returned them to their original place in the pits.”

The cost had been heavy for the 20th Massachusetts, but they had helped hold and secure the Federal line on Cemetery Ridge. The reputation of their unit had been forged on many fierce battlefields, but in these soldiers’ minds Fredericksburg had been the moment that prepared them for Gettysburg. Feelings of relief and revenge prompted the chant “Fredericksburg, Fredericksburg” as they poured a shocking volley into the Confederate infantry in front of their position near the center of the line at Gettysburg.

The battle in central Virginia six months earlier had left a deep impression on the 20th Massachusetts soldiers. Their urban attack, assault on Marye’s Heights, and horrifying night on the battlefield left that town’s name as the place where they fought against terrible odds with a foe most probably never got close enough to see. On a ridge in Pennsylvania, they had their moment of payback, and they knew it. They gave them

“Fredericksburg” and all the tragedy, carnage, and horror that word had come to symbolize for those survivors from Massachusetts.

Sarah Kay Bierle serves on staff at Central Virginia Battlefields Trust. CVBT is dedicated to preserve hallowed ground at Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, The Wilderness,

and Spotsylvania Court House. To learn more about this grassroots preservation non-profit, please visit: www.cvbt.org.

Isaac Hollis & Sons (formerly Hollis & Sheath)

The English Gun Trade has families that overlap and intertwine over the course of the decades, and in some cases centuries, while they are in the trade. There are many cases where nephews share the same names as uncles, eldest sons with fathers, etc., J.E. Barnett commercial gunmaking firm is a great example of this. Reconstructing the Isaac Hollis story is somewhat complicated because it was a family with several branches in the Birmingham Gun Trade. The seminal gun-maker William Hollis was born in 1777 and established his business in 1807 at St Mary's Row; he was recorded there until 1811. He most likely had at least one brother, Richard Hollis, in the firm.

There was also a nephew named Richard Hollis (1829-1853).

Around 1814 William and his brother moved to 73 Bath Street and did business as Richard & William Hollis at Bath Street until 1829. In 1838 the firm became William Hollis & Sons, but reverted back to a sole proprietorship as William Hollis in 1839 when sons Frederick and Isaac formed Hollis Bros & Company. When William Hollis died in 1856 at the age of 79 he claimed to be the oldest manufacturer and contractor in Birmingham.

In 1829 William’s brother Richard Hollis opened his own premises at 3 Lench Street. In 1833 Richard also occupied 20 St Mary's Row, but for a short time only. In 1847 Richard moved from Lench Street to 79 Weaman Street, and it appears that he teamed up with Christopher Hollis, possibly a brother or son,

as the record is not clear. This firm is no longer recorded after 1853.