12 minute read

Erectile Dysfunction: Harbinger of Early Cardiovascular Disease

Comanagement of cardiovascular disease risk factors through exercise and weight loss can improve erectile function.

Erectile dysfunction may be one of the first physical manifestations of atherosclerosis in men.

Erectile dysfunction is a common disorder defined as “the persistent inability to achieve and then maintain an erection to permit satisfactory sexual intercourse.”1 An estimated 18 million men in the United States (18%) have ED.2 In a cross-sectional analysis, the prevalence of ED differed markedly by age, ranging from 5.1% in men aged 20 to 39 years to 70.2% in men older than 70 years of age.2 However, a recent study found that the incidence of ED in younger men is increasing, estimating the prevalence of ED in younger men (<40 years) to be as high as 30%.3

Although it can be distressing for patients to discuss ED, proper evaluation and treatment of the condition can significantly improve quality of life.4 The growing acknowledgement that ED is a harbinger of cardiovascular disease (CVD), for example, has made the early diagnosis of ED associated with vascular risk factors a priority for many primary care clinicians. Proper evaluation and treatment of ED has been shown to decrease the risk for CVD morbidity.1,5-9

Causes of Erectile Dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction is caused by a variety of factors such as vascular, endocrinologic, neurologic, psychogenic, and anatomic abnormalities. It also can be caused by a combination of factors, which can make determining the cause of ED more difficult. Psychogenic etiologies of ED include depression, anxiety, and interpersonal partner-related

conflicts.3 Men with ED related to psychogenic factors tend to experience a sudden onset of symptoms, decreased libido and normal androgen status, nocturnal or self-stimulated erections, and normal findings on penile duplex Doppler ultrasonography.3,10 Patients with ED related to vascular, endocrinologic, or neurologic factors usually experience a gradual onset of symptoms and a low to normal libido, weak noncoital erections, inconsistent early morning erections, and abnormal Doppler ultrasound findings.11,12

Cardiovascular Health and Erectile Dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction may be one of the first physical manifestations of atherosclerosis in men. Patients with ED of vascular etiology are at a higher risk for coronary artery disease (CAD) and should be screened for CVD and educated about lifestyle management options. Similarly, men with known risk factors for CVD — smoking, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes — should be screened for ED.6 The coexistence of these diseases often is overlooked by providers and can lead to adverse health effects as both conditions worsen.8

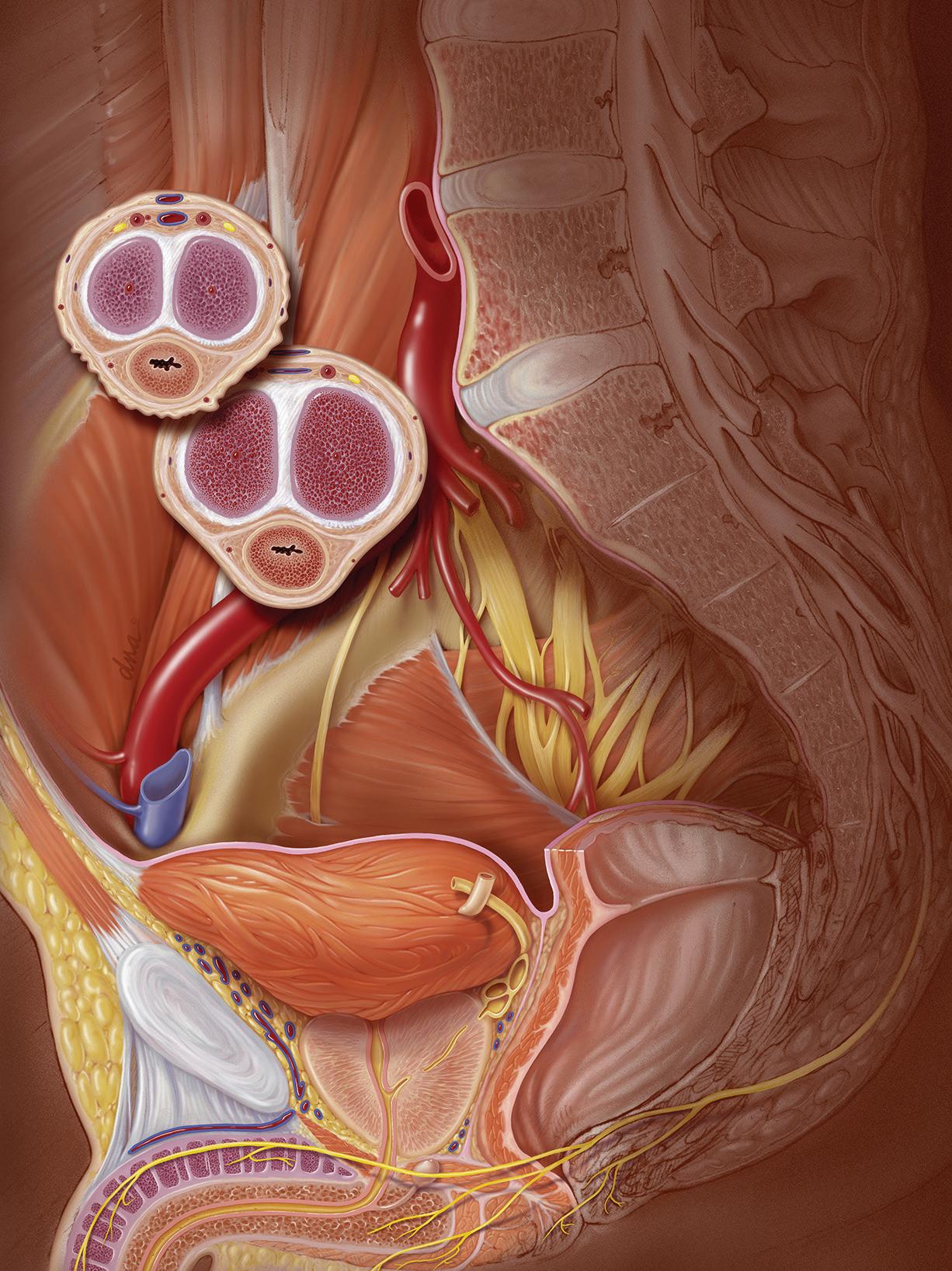

There is a clear link between increasing severity of ED and poor cardiovascular health. Sufficient blood flow and nitric oxide levels are required for successful erections.13 Interference with blood flow greatly affects the ability to maintain an erection.13,14 When more than 50% of the lumen of the deep penile (cavernosal) and common penile arteries are narrowed, ED will occur.13

It also is important to evaluate the elasticity of the endothelium in patients with CVD and those with ED. PohjantähtiMaaroos et al reported that men with ED had a significantly lower arterial elasticity index than those without ED after adjustment for age, diabetes, family history of CVD, smoking, physical activity, use of statins or β-blockers, waist circumference, blood pressure, and lipids.15 This study confirms that atherosclerotic damage physiologically affects the systemic elasticity of arteries, including the penile artery.

Dzenkeviciute et al evaluated subclinical vascular disease in relation to ED severity and found that men with ED had significantly higher CVD risk than controls.7 The severity of ED also was associated with left ventricular hypertrophy, left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, and impaired renal function. The changes they found in the endothelium were the same changes that occur in patients with chronic kidney disease and chronic myocardial injury.

Inman et al found new-onset CAD in more than 10% of men with ED during a 10-year follow-up period.6 Banks et al found that men with worsening ED and CVD have increasing hospitalizations related to myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and heart failure. Vascular ED also is associated with increased overall mortality.9

Patients without CAD who have ED symptoms likely are experiencing mild endothelial changes beginning in arteries such as the penile artery and should be counseled about measures to prevent CAD.6

Evaluation and Screening

Having an understanding of the relationship between ED and CVD may lead more men to openly discuss their sexual history, allowing providers to address both conditions and possibly prevent the worsening of CVD. Men with better overall cardiovascular health will have a better long-term prognosis related to sexual function.9

Erectile dysfunction often presents as a mix of both psychogenic and vascular etiologies; therefore, it is important to determine the specific cause or causes of ED.11 Evaluation of vascular ED should begin with a thorough history, including medical and sexual history. It is important to approach the topic sensitively and educate the patient about the prevalence of ED. The stigma related to ED is what prevents many men from admitting difficulty in their sexual life.14

A thorough history of the patient’s smoking status, diet, and exercise routines should be included in the patient interview.5 It also is important to ask the patient about major symptoms associated with cardiac disease, such as chest pain, edema, palpitations, syncope, fatigue, and dyspnea. Patients who smoke or have diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity, or metabolic syndrome should be counseled that these diseases not only increase risk for adverse outcomes such as myocardial infarction and stroke but also affect the ability to maintain an erection.16

In general, when discussing a patient’s ability to obtain an erection, there are specific aspects of the history that suggest the problem is vascular. A gradual onset of ED is indicative of vascular etiology. Weak noncoital erections and inconsistent early morning erections suggest abnormal vascular functioning.11 The patient’s sexual partner should be included in the interview and can help explain the patient’s difficulty in obtaining or maintaining an erection, along with sexual technique and any other sexual problems the couple may be facing.17

Physical Examination

The physical examination should start with an assessment of the vital signs. If the patient has tachycardia (pulse >100 beats per minute), hypertension (blood pressure ≥130/80 mm Hg), or tachypnea (respiratory rate >20 breaths per minute), then a more detailed cardiovascular examination should be performed.18 The patient’s waist circumference and BMI should be assessed. All of the peripheral pulses should be palpated and documented for signs of vascular disease. Cardiac auscultation along with auscultation for carotid, aortic, renal, and iliac bruits should be performed.19

CARDIOVASCULAR HEALTH: ERECTILE DYSFUNCTION Having an understanding of the relationship between ED and CVD may lead more men to openly discuss their sexual history.

A full urologic examination should be performed, including inspection of the testes and penis for any anatomical abnormalities. Assessment of the bulbocavernosus reflex and anal sphincter tone is important for evaluating the sacral neural outflow.17 A detailed physical examination and thorough history of present illness are key in determining a vascular etiology of ED.

The workup for a patient with ED often includes assessment of potential hormonal and psychologic etiologies, but many primary care providers and urologists overlook vascular etiology. A standard cardiovascular assessment should include blood work, including fasting glucose, glycated hemoglobin A1c, lipid panel, creatinine, and serum testosterone, as well as an electrocardiogram.20

The severity of ED is measured using the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) or the simplified International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5). The IIEF is a validated selfadministered questionnaire that is a highly specific and sensitive measurement of ED severity.21 Questions in the IIEF assess confidence, penetration ability, maintenance of erection, and satisfaction after sexual intercourse. The responses are calculated, with the ED classified as mild, mild-moderate, moderate, or severe.22

Color Doppler ultrasonography is another diagnostic tool that allows for visualization of arterial insufficiency or other vascular etiology of ED.10 This assessment is performed by giving the patient a pharmaceutical agent that causes an erection, followed by ultrasonography of the left and right cavernosal arteries. Many providers use ultrasonography to determine cavernosal artery flow velocities to accurately characterize arterial integrity.12 This allows for identification of hemodynamic instability causing ED. Doppler ultrasound showed a high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (78%) in diagnosing vascular ED in a prospective study.12 Ultrasound findings also can detect the severity of atherosclerotic activity within the penile artery, which may be an indicator of systemic CVD.12

Penile vasculature is small, making it a particularly sensitive marker of systemic vascular disease; smaller arteries often are affected earlier than larger arteries in vascular disease. The diameter of penile arteries is usually 1 to 2 mm compared with 3 to 4 mm for coronary arteries and 5 to 7 mm for carotid arteries. Vessel size theory suggests that an atherosclerotic plaque should occlude and affect the penile artery earlier than a carotid or coronary artery.6

Treatment of Erectile Dysfunction

A variety of medical and nonmedical options can be used to treat vascular ED. Lifestyle changes, such as weight loss, exercise, dietary changes, cessation of smoking, and reduced alcohol consumption, help treat ED and prevent the development of CVD. These modifiable behaviors should be the first interventions addressed with patients to improve their ED and their cardiovascular health.23

A longitudinal study found that men who initiated physical activity for the first time in midlife had a reduced risk for ED compared with those who remained sedentary (odds ratio, 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1-0.6). One-third of men with ED at baseline were able to improve sexual function through lifestyle changes alone.24

Younger men with vascular ED, in particular, should be counseled on their increased risk for atherosclerosis and educated about lifestyle changes that can lower the risk for CVD and mortality and improve quality of life. For example, the risk for death from CVD declines by half after 5 years of stopping smoking. Thus, smoking cessation should be encouraged in the younger population.25

Phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors have been proven to be effective in improving ED in patients with cardiovascular risk factors or CVD. These medications allow for corporeal vascular relaxation and penile erection during sexual stimulation.26 This class of medications also has been shown to improve cardiovascular functioning by increasing the ischemic threshold.27 Three PDE5 inhibitors have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration: sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil. The drugs are the mainstay of the pharmacologic treatment for ED and have been shown to improve hypertension and endothelial changes in patients with CVD.19 These drugs do not increase the risk for cardiovascular events, such as ischemia, myocardial infarction, and myocardial hypertrophy, and can be safely coadministered with anti- hypertensive medications, statins, and most other medications. However, patients should avoid taking nitrates while taking PDE5 inhibitors because a severe drop in blood pressure may occur if these agents are used together.28

Aspirin, a medication known for its antiplatelet activity, also has been studied in patients with ED. In a study comparing aspirin and tadalafil, both medications were proven effective in the treatment of vascular ED; however, a combination of tadalafil and aspirin showed greater efficacy compared with aspirin or tadalafil alone.29 In addition, the analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of aspirin decrease side effects of tadalafil, such as headache, back pain, extremity pain, flushing, and myalgia. Aspirin also may delay the onset of penile atherosclerosis by inhibiting platelet activity, reducing

proinflammatory mediators, and decreasing vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation.29

Low intensity shock-wave therapy (LISWT) is a more invasive treatment option for men with vascular ED. While the mechanism of action of LISWT is unclear, it is believed that the compression and negative pressures created by this therapy lead to shear stress on cell membranes, causing an increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and resulting in neovascularization of penile arteries.30

For patients taking β-blockers for heart failure or hypertension who experience ED, practitioners should consider nebivolol, a β-blocker that is less likely to cause difficulty with obtaining and maintain an erection.19

Conclusion

Healthcare providers should discuss cardiovascular risk factors in all patients with ED. Men with any sexual dysfunction should be screened for CVD and educated promptly about lifestyle management. Early detection and comanagement of CVD risk factors in men with ED is beneficial to promote sexual well-being and prevent CVD.5 ■

Melissa Long, PA-C, is a recently graduated physician assistant currently working at Doctors Urology and Pelvic Health Specialists in Augusta, Georgia. E. Rachel Fink, MPA, PA-C, is a physician assistant at Augusta Urology Associates and an assistant professor in the Physician Assistant Program at Augusta University.

References

1. Jackson G, Boon N, Eardley I, et al. Erectile dysfunction and coronary artery disease prediction: evidence-based guidance and consensus. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(7):848-857. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02410.x 2. Selvin E, Burnett AL, Platz EA. Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in the US. Am J Med. 2007;120(2):151-157. doi:10.1016/j. amjmed.2006.06.010 3. Nguyen HMT, Gabrielson AT, Hellstrom WJG. Erectile dysfunction in young men—a review of the prevalence and risk factors. Sex Med Rev. 2017;5(4):508-520. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.05.004 4. Pastuszak AW. Current diagnosis and management of erectile dysfunction. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2014;6:164-176. doi.10.1007/s11930-014-0023-9 5. Walczak MK, Lokhandwala N, Hodge MB, Guay AT. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in erectile dysfunction. J Gend Specif Med. 2002;5(6):19-24. 6. Inman BA, Sauver JL, Jacobson DJ, et al. A population-based, longitudinal study of erectile dysfunction and future coronary artery disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(2):108-113. doi:10.4065/84.2.108 7. Dzenkeviciute V, Petrulioniene Z, Rinkuniene E, Sapoka V, Petrylaite M, Badariene J. Cardiorenal determinants of erectile dysfunction in primary prevention: a cross-sectional study. Med Princ Pract. 2018;27(1):73-79. doi:10.1159/000484949 8. Shah NP, Cainzos-Achirica M, Feldman DI, et al. Cardiovascular disease prevention in men with vascular erectile dysfunction: the view of the preventive cardiologist. Am J Med. 2016;129(3):251-259 doi:10.1016/j. amjmed.2015.08.038 9. Banks E, Joshy G, Abhayaratna WP, et al. Erectile dysfunction severity as a risk marker for cardiovascular disease hospitalisation and all-cause mortality: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2013;10(1): e1001372. doi:10.1371/ journal.pmed.1001372 10. Deveci S, O’Brien K, Ahmed A, Parker M, Guhring P, Mulhall JP. Can the International Index of Erectile Function distinguish between organic and psychogenic erectile function? BJU Int. 2008;102(3):354-356. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07610.x 11. Same RV, Miner MM, Blaha MJ, Feldman DI, Billups KL. Erectile dysfunction: an early sign of cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2015;9(49). doi.10.1007/s12170-015-0477-y 12. Yildirim D, Bozkurt IH, Gurses B, Cirakoglu A. A new parameter in the diagnosis of vascular erectile dysfunction with penile Doppler ultrasound : cavernous artery ondulation index. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17(10):1382-1388. 13. Ponholzer A, Temml C, Rauchenwald M, Madersbacher S. Vascular risk factors and erectile dysfunction in healthy men. Int J Impot Res. 2006;18(5):489-493. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3901468 14. Solomon H, Man JW, Jackson G. Erectile dysfunction and the cardiovascular patient: endothelial dysfunction is the common denominator. Heart. 2003;89(3):251-253. doi:10.1136/heart.89.3.251 15. Pohjantähti-Maaroos H, Palomäki A. Comparison of metabolic syndrome subjects with and without erectile dysfunction—levels of circulating oxidised LDL and arterial elasticity. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(3): 274-280. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02595.x 16. Swap CJ, Nagurney JT. Value and limitations of chest pain history in the evaluation of patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2005;294(20):2623-2629. doi:10.1001/jama.294.20.2623 17. Irwin GM. Erectile dysfunction. Prim Care. 2019;46(2):249-255. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2019.02.006 18. Schwartz BG, Kloner RA. How to save a life during a clinic visit for erectile dysfunction by modifying cardiovascular risk factors. Int J Impot Res. 2009;21(6):327-335. doi:10.1038/ijir.2009.38 19. Nehra A, Jackson G, Miner M,,et al. The Princeton III Consensus recommendations for the management of erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(8):766-778. doi:10.1016/j. mayocp.2012.06.015