15 minute read

The Impact of Obesity on Knee OA Symptoms and Surgical Outcomes

The knee is the most common lower-limb joint affected by OA.

Osteoarthritis (OA), or degenerative joint disease, is the most common form of arthritis, affecting more than 32.5 million adults in the United States.1 Osteoarthritis results from damage to or breakdown of cartilage between bones, with the knee being the most common lower-limb joint affected by OA. The prevalence of OA significantly increases with age.1

Risk Factors for Knee OA

Knee OA is a multifactorial disease, with many risk factors playing a role in symptomatic findings and disease progression. Risk factors for knee OA include obesity, physical stress at work, previous trauma or injury to the knee, genetics, and gender (occurs more commonly in women than men).1,2

Common knee surgeries, such as anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) repair and arthroscopic meniscal surgery, may increase a patient’s risk of developing OA,3 in part because of alterations in gait after surgery. Evidence also suggests that varus malalignment increases the risk of developing OA in the medial tibiofemoral aspect of the knee.4 In patients who are obese, increased compressive load on the medial compartment during weight-bearing activities can result in medial tibiofemoral OA.4

It is important for primary care providers to educate their patients about modifiable risk factors for knee OA, such as obesity, so that patients can incorporate changes into their daily routine to improve symptoms of knee pain.

Symptoms and Diagnosis of Knee OA

Chief complaints from patients with knee OA may include, but are not limited to, knee pain (including at night), loss of function, stiffness, swelling, decreased range of motion, limitations in activities of daily living, and disability.1

A thorough evaluation of a patient’s history can help identify risk factors or potential causes of knee OA. Clinical and physical examination findings also should be considered when diagnosing knee OA.1

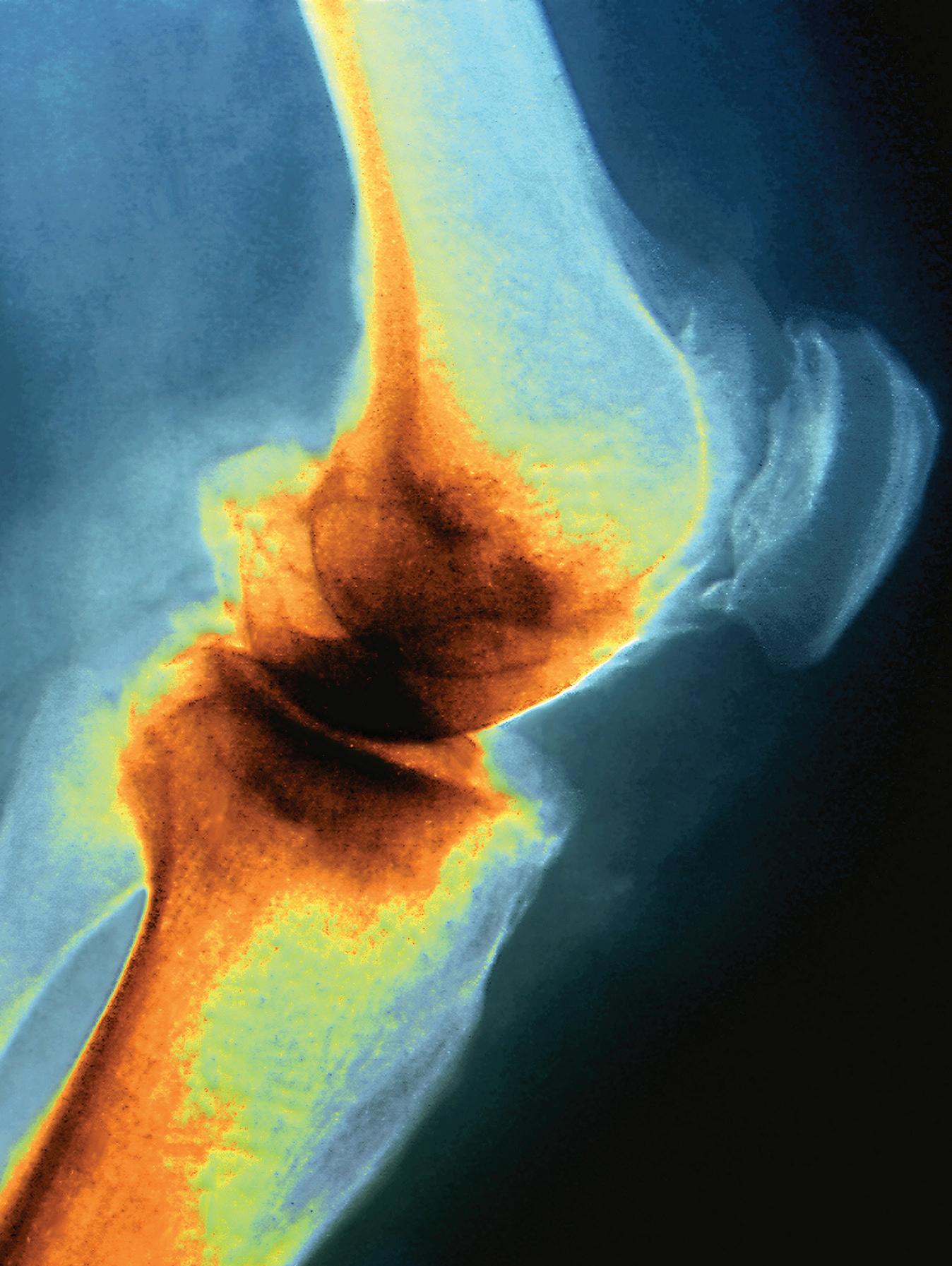

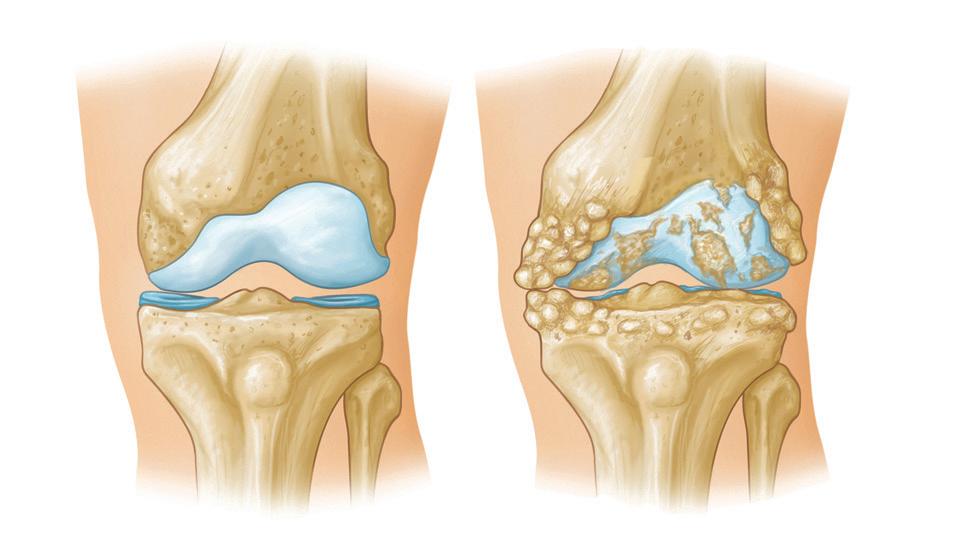

Radiographs of the knee in patients with OA show cartilage loss and the resultant narrowing of the joint space and bone spurs around the joint (Figure).5 However, symptom severity in knee OA does not always correspond with radiologic findings.5 Pain is a subjective finding, making it difficult to determine why some people with OA are more symptomatic than others.

Once a diagnosis is made, it is important to identify the best treatment option for each patient.

Treatment Options for Knee OA

Osteoarthritis is a chronic, progressive disease, and treatment goals are targeted toward managing symptoms and slowing disease progression. A wide variety of conservative treatment options are available for knee OA.6-8

First-line pharmacologic treatment options for knee OA include topical or oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroid injections.8 However, these options may be limited by adverse effects and are not recommended for long-term use.8 Other recommended treatments include acetaminophen, duloxetine, topical capsaicin, and tramadol.8

Nonpharmacologic options such as lifestyle recommendations — exercise (walking, strength training, neuromuscular training, and aquatic exercise), tai chi, tibiofemoral knee braces, canes, and weight loss — are strongly recommended for people with knee OA. Alternative therapies that may reduce OA pain complaints include acupuncture, cognitive behavioral therapy, kinesiotaping, patellofemoral braces, radiofrequency ablation, thermal interventions, and yoga.8 The therapeutic effectiveness of these alternative therapies, however, has not been confirmed.7,8

When knee OA becomes refractory to conservative treatment measures and a patient’s quality of life is affected, surgical options should be considered. Several surgical options are considered curative treatments for knee OA. Common surgeries to treat knee OA include total knee replacement (TKR), unicompartmental knee replacement, osteotomy, arthroscopy, and cartilage repair.6

Multiple variables must be considered when determining which treatment option or surgical procedure is most appropriate for a patient. Weight management interventions are an important step, regardless of whether a patient undergoes conservative or surgical treatment for knee OA.

The Role of Weight Loss in OA Management

Obesity is a serious health problem that increases a patient’s risk for many chronic diseases, including joint pain and knee OA. In 2018, the prevalence of obesity in the United States was 42.4%.8 Patients with a BMI ≥30 have a 7-fold increased risk of developing knee OA.2

Weight loss is a healthy way to manage symptoms associated with knee OA. Research shows that weight loss is associated with reduced pain, improved function, and better quality of life in patients with knee OA who are overweight or obese.9,10 There is a strong, consistent relationship between obesity and the development of severe OA knee pain; clinicians can use this information to educate patients about the importance of weight loss to modify the disease course.11 Clinicians should educate patients about how much weight they may need to lose to see an improvement in knee OA symptoms.

Messier et al found that for every 1 pound lost, 4 pounds of stress are unloaded off the knees.12 A body weight reduction of 1% has been associated with a 2.8% improvement in function, pain, and stiffness, as measured by the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) scale.10 Thus, overweight or obese patients with knee OA who reduce their weight by 10% could see a 28% decline in knee OA pain and symptoms.10

It is important for patients to understand that weight loss will not reverse the disease process but can alter the severity of their symptoms by reducing the load on the knees. Daugaard showed that patients with obesity who lost a substantial amount of weight (mean, 12 kg) reduced their pain

Articular Cartilage

Meniscus Bone Spurs

Cartilage Loss

Normal Joint Space Joint Space Narrowing

Reproduced with permission from OrthoInfo. © American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. https://orthoinfo.org/

FIGURE. The physiologic changes between a normal knee (left) and a knee with osteoarthritis (right).5

OSTEOARTHRITIS AND OBESITY First-line treatments for knee OA include topical or oral nonsteroidal anti-in ammatory drugs and corticosteroid injections.

level.13 However, the in ammation seen on dynamic contrastenhanced magnetic resonance imaging was unchanged from the start of the study.

Weight loss also can help prevent the progression of mild knee pain to severe, debilitating knee pain. Jinks et al found that 19% of new cases of severe knee pain that developed over the 3-year study period in patients who were overweight or obese could have been avoided by a shift downward in BMI category.11 This demonstrates that weight loss is an e ective treatment option to improve quality of life and delay surgical intervention. Early intervention by clinical providers focused on educating patients about the bene ts of weight loss can help those with knee OA maintain the ability to continue their normal daily activities without disabling pain.

Obesity and Surgical Outcomes

When daily functioning is a ected by severe OA pain that is refractory to conservative approaches, surgical intervention becomes a viable option. Total knee replacement is an invasive procedure, and providers and patients must evaluate the risks and bene ts of this surgery. For patients who eventually need surgical intervention for knee OA, weight loss also leads to improved outcomes after TKR surgery.

Patients with obesity are at increased risk for surgical revision.14,15 Surgical revisions can be required after loosening or wear of 1 or more components of the prosthetic joint.14 Higher revision rates in patients with obesity have been attributed to increased compressive forces on the joint due to excess weight. Surgical revision of a TKR also may be needed after complications from an infected prosthetic joint.14 Such infections after TKR are more common in patients with obesity compared with patients without obesity.14,15 This is, in part, because obesity is associated with reduced subcutaneous tissue oxygenation, which is associated with higher rates of wound infection.16 The severity of potential postoperative infections can range from a super cial wound infection to deep infection of the prosthetic joint. Studies have shown that patients with obesity who undergo TKR are at increased risk for both deep infections and TKR revisions.15

Despite the possibility of complications, TKR has been proven to improve functional outcomes in patients with and without obesity.

How to Help Patients Lose Weight

When addressing weight loss with patients, it is important to provide them with feasible weight-loss options that can help them achieve their goals. Clinicians must assess each patient’s needs and access to resources to help them achieve optimal outcomes when they are attempting to lose weight.

Initial weight-loss recommendations should include information on how patients can increase physical activity while also modifying their diet to reduce caloric intake. An open discussion about obstacles to achieving weight loss will allow patients and providers to come up with feasible lifestyle modi cations patients can incorporate into their daily routines.

Patients have reported that lack of time and lack of accessibility to an exercise facility are 2 of the most common barriers preventing them from losing weight.17 For patients without access to a gym, clinicians can provide home exercises that require little equipment. For patients who do have access to exercise facilities, aquatic therapy has proven to be an e ective option for individuals with knee OA.8 Patients who have concerns about how they will achieve exercise or who experience low physical self-esteem may bene t from group exercise programs or a personal trainer.

For patients to achieve weight loss, they must address diet as well as exercise habits. Information about healthy eating and cost-e cient healthy recipes can provide patients with the skills and resources needed to incorporate healthy eating habits into their daily routines. In a survey conducted at an orthopedic clinic, 61% of participants with obesity reported that they would be most interested in information about

POLL POSITION

Which of the following statements is not true about knee OA?

■ Weight loss slows progression of OA ■ Obesity increases risk for postoperative infection ■ Patients with BMI ≥30 have 10-fold risk for OA ■ A 10% loss of weight equals 28% decline in pain 18.95%

20.35% 31.93%

28.77%

For more polls, visit ClinicalAdvisor.com/Polls.

healthy eating when receiving information from a healthcare professional about weight loss.18

Teaching patients how to moderate portions and eliminate unhealthy foods from their diet also is positively associated with successful weight loss. Some patients may benefit from a referral to a registered dietitian when starting their weightloss journey. Reducing caloric intake by decreasing sugar consumption, increasing fruit and vegetable intake, controlling portions, and increasing physical activity provides patients with the greatest chance of achieving weight loss.19

Pharmacotherapy is an option for patients with a high BMI and weight-related comorbidities who have tried and failed to lose weight with exercise and diet alone. A recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found that the following antiobesity medications indicated for long-term use are associated with a significant reduction in body weight: liraglutide, lorcaserin, naltrexone/bupropion, orlistat, and phentermine/extended-release topiramate.20 Primary care providers should discuss these options with their patients to determine whether these options are appropriate.

When conservative treatment options have failed, referral to a bariatric surgeon may be warranted.

Conclusion

Weight loss can be a beneficial and conservative approach to treating patients who are overweight or obese and have knee OA. Weight loss can improve knee pain, overall function, and quality of life. It is important for clinicians to address weight loss at all encounters with their patients and help set realistic goals. Discussion about patient goals and perceived barriers to weight loss can help providers offer patients resources they need to best meet their individual goals. Most studies show that at least a 10% weight reduction is needed to improve knee pain in OA.9,10,21 If a 10% loss is achieved, encouraging patients to continue their weight-loss journey can help further reduce the load on their knees.

In patients who undergo surgery, obesity is associated with an increased risk for postoperative infection as well as failure of the prosthesis requiring revision surgery.14,15 Thus, for patients undergoing TKR, clinicians may require weight loss before surgery, particularly if patients are morbidly obese. Although it can be challenging for providers and patients to discuss weight loss, it is in the best interest of patients and will contribute to optimal surgical outcomes. Patients who receive weight-loss counseling are 4 times more likely to achieve success after surgery compared with those who do not receive counseling.22

Weight-loss methods should be determined based on what is best for the patient and what is most feasible in a given timeframe. Primary care providers can help guide patient education about weight loss and treatment options for patients with knee OA considering TKR surgery. ■

Natalie Reed, PA-C, is a recent graduate of the Physician Assistant Program at Augusta University in Augusta, Georgia, and is currently working in orthopedics in Atlanta. Kelly S. Reed, PharmD, MPA, PA-C, is an assistant professor in the Physician Assistant Program at Augusta University.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Osteoarthritis (OA). Updated July 27, 2020. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/ arthritis/basics/osteoarthritis.htm 2. Toivanen AT, Heliövaara M, Impivaara O, et al. Obesity, physically demanding work and traumatic knee injury are major risk factors for knee osteoarthritis—a population-based study with a follow-up of 22 years. Rheumatology. 2010;49(2):308-314. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kep388 3. Capin JJ, Khandha A, Zarzycki, Manal K, Buchanan TS, Synder-Mackler L. Gait mechanics after ACL reconstruction differ according to medial meniscal treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(14):1209-1216. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.01014 4. Wei J, Gross D, Lane NE, et al. Risk factor for heterogeneity for medial and lateral compartment knee osteoarthritis: analysis of two prospective cohorts. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27(4):603-610. doi:10.1016/j. joca.2018.12.013 5. Arthritis of the knee. Orthoinfo. Updated June 2014. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases--conditions/ arthritis-of-the-knee/. 6. Bedson J, Croft PR. The discordance between clinical and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a systematic search and summary of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:116. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-9-116 7. Brown GA. AAOS clinical practice guideline: treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd edition. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21(9):577-579. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-21-09-577 8. Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2020;72(2): 149-162. doi:10.1002/acr.24131 9. Messier SP, Mihalko SL, Legault C, et al. Effects of intensive diet and exercise on knee joint loads, inflammation, and clinical outcomes among overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis: the IDEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(12):1263-1273. doi:10.1001/ jama.2013.277669

10. Christensen R, Astrup A, Bliddal H. Weight loss: the treatment of choice for knee osteoarthritis? A randomized trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(1):20-27. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2004.10.008 11. Jinks C, Jordan K, Croft P. Disabling knee pain—another consequence of obesity: results from a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:258. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-258 12. Messier SP, Gutekunst DJ, Davis C, DeVita P. Weight loss reduces knee-joint loads in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(7):2026-2032. doi:10.1002/ art.21139 13. Daugaard CL, Henriksen M, Riis RGC, et al. The impact of a significant weight loss on inflammation assessed on DCE-MRI and static MRI in knee osteoarthritis: a prospective cohort study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2020;28(6):766-773. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2020.02.837 14. Boyce L, Prasad A, Barrett M, et al. The outcomes of total knee arthroplasty in morbidly obese patients: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2019;139(4):553-560. doi:10.1007/ s00402-019-03127-5 15. Kerkhoffs GMMJ, Servien E, Dunn W, Dahm D, Bramer JA, Haverkamp D. The influence of obesity on the complication rate and outcome of total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis and systematic literature review. J Bone Joint Surg. 2012;94(20):1839-1844. doi:10.2106/ JBJS.K.00820 16. Kabon B, Nagele A, Reddy D, et al. Obesity decreases perioperative tissue oxygenation. Anesthesiology. 2004;100(2):274-280. doi:10.1097/ 00000542-200402000-00015 17. Wilcox S, Der Ananian C, Abbott J, et al. Perceived exercise barriers, enablers, and benefits among exercising and nonexercising adults with arthritis: results from a qualitative study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(4): 616-627. doi:10.1002/art.22098 18. Howarth D, Inman D, Lingard E, McCaskie A, Gerrand C. Barriers to weight loss in obese patients with knee osteoarthritis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92(4):338-340. doi:10.1308/003588410X12628812458653 19. Varkevisser RDM, van Stralen MM, Kroeze W, Ket JCF, Steenhuis IHM. Determinants of weight loss maintenance: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2019;20(2):171-211. doi:10.1111/obr.12772 20. Singh AK, Singh R. Pharmacotherapy in obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of anti-obesity drugs. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13(1):53-64. doi:10.1080/17512433. 2020.1698291 21. Atukorala I, Makovey J, Lawler L, et al. Is there a dose-response relationship between weight loss and symptom improvement in persons with knee osteoarthritis? Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68(8):1106-1114. doi:10.1002/acr.22805 22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Weight loss for adults with arthritis.. Updated September 9, 2020. Accessed February 5, 2021. https:// www.cdc.gov/arthritis/communications/features/arthritis-weight-loss.html

Erectile Dysfunction

Continued from page 15

20. Schroeder S, Enderle MD, Ossen R, et al. Noninvasive determination of endothelium-mediated vasodilation as a screening test for coronary artery disease: pilot study to assess the predictive value in comparison with angina pectoris, exercise electrocardiography, and myocardial perfusion imaging. Am Heart J. 1999;138(4 Pt 1):731-739. doi:10.1016/ s0002-8703(99)70189-4 21. Tang Z, Li D, Zhang X, et al. Comparison of the simplified International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) in patients of erectile dysfunction with different pathophysiologies. BMC Urol. 2014;14:52. doi:10.1186/1471-2490-14-52 22. Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, Lipsky J, Peñ BM. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11(6):319-326. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3900472 23. Esposito K, Giugliano F, Maiorino MI, Giugliano D. Dietary factors, Mediterranean diet and erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2010;7(7):2338-2345. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01842.x 24. Derby CA, Mohr BA, Goldstein I, Feldman HA, Johannes CB, McKinlay JB. Modifiable risk factors and erectile dysfunction: can lifestyle changes modify risk? Urology. 2000;56(2):302-306. doi:10.1016/ s0090-4295(00)00614-2 25. Prabhat J. The hazards of smoking and the benefits of cessation: a critical summation of the epidemiological evidence in high-income countries. eLife. 2020;9:e49979. doi:10.7554/eLife.49979 26. Gazzaruso C, Solerte SB, Pujia A, et al. Erectile dysfunction as a predictor of cardiovascular events and death in diabetic patients with angiographically proven asymptomatic coronary artery disease: a potential protective role for statins and 5-phosphodiesterase inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(21):2040-2044. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.069 27. Thadani U, Smith W, Nash S, et al. The effect of vardenafil, a potent and highly selective phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor for the treatment of erectile dysfunction, on the cardiovascular response to exercise in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(11):2006-2012. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02563-9 28. Vlachopoulos C, Ioakeimidis N, Rokkas K, Stefanadis C. Cardiovascular effects of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors. J Sex Med. 2009;6(3):658-674. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01107.x 29. Bayraktar Z, Albayrak S. Efficacy and safety of combination of tadalafil and aspirin versus tadalafil or aspirin alone in patients with vascular erectile dysfunction: a comparative randomized prospective study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2019;51(9):1491-1499. doi:10.1007/s11255-019-02211-4 30. Brunckhorst O, Wells L, Teeling F, Muir G, Muneer A, Ahmed K. A systematic review of the long-term efficacy of low-intensity shockwave therapy for vasculogenic erectile dysfunction. Int Urol Nephrol [Internet]. 2019;51(5):773-781. doi:10.1007/s11255-019-02127-z