15 minute read

Dermatologic Look-Alikes

Blisters on the Hands

DINA ZAMIL, BS; TARA L. BRAUN, MD; CHRISTOPHER RIZK, MD

CASE #1

A 65-year-old man with hypertension presents to the dermatology clinic with a 3-day history of a rash on his arms and trunk. The patient reports having a similar rash 1 year ago that started 2 weeks after he had a tender blister on his lip. On examination, the patient has numerous scattered, target-like lesions with central vesicles on his palms, dorsal hands, forearms, back, and chest. The rash does not involve the mucosa, and the patient has no systemic symptoms. The patient has no food allergies and has no history of any other medical conditions. The rest of the examination is normal.

CASE #2

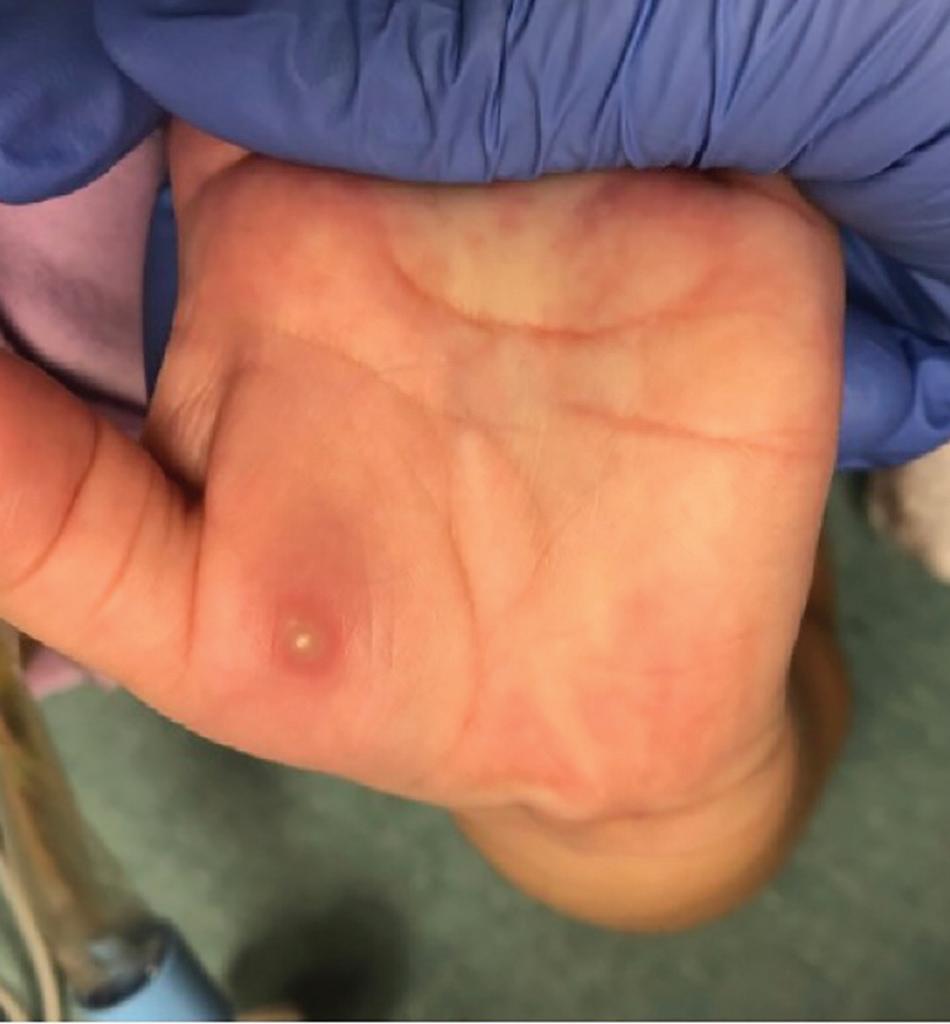

A 5-year-old girl presents with a 1-day history of fever, sore throat, and rash that started on her hands and feet and has spread to her legs. She has not been able to eat or drink for 24 hours because of throat pain. She attends day care and has 2 older siblings. On examination, the patient has scattered erythematous macules and vesicles with an erythematous base on her palms, lower legs, and soles of the feet. She also has erosions on her buccal mucosa and posterior oral cavity. The child’s parents report that the child has no food allergies or other chronic conditions. The rest of the physical examination is normal.

Dermatologic Look-Alikes

CASE #1 Erythema Multiforme

Erythema multiforme (EM) is an acute, immune-mediated, hypersensitivity reaction affecting the skin and/or mucosa.1-3 EM, which can be episodic, recurrent, or seasonal, is known classically for its characteristic target-like lesions.1-4 There are 2 types of EM: EM minor, which affects the skin and not the mucosa; and EM major, which involves the mucosa.1,3

Case reports of EM date back to 1884.5 Although EM originally was considered to be closely related to Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis, it now is recognized as a separate disease.1-3

The prevalence of EM is unknown but is estimated to be between 0.01% and 1% of the population.1 EM occurs more commonly in young adults aged 20 to 40 years and women and has no racial predilection.1,2 However, a predisposition among certain Asian ethnic groups has been reported.3,6 In 37% of cases, recurrence of EM has been reported; in children, recurrent EM is more common in boys than girls.1-3,7

EM is caused by an immune response targeting small blood vessels in the mucosa and skin.2,3 Approximately 90% of EM cases are linked to infection, most commonly herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 and less often HSV type 2.1-3 The second most common infectious agent is Mycoplasma pneumoniae, particularly in children.1 Other viral infections associated with EM include Epstein-Barr virus, influenza virus, hepatitis C virus, cytomegalovirus, enteroviruses, and adenoviruses.2,3 Bacterial infections associated with EM include salmonella, pneumococcus, Mycobacterium leprae, hemolytic streptococcus, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, and Legionella pneumophila. 3

Drug-associated EM is reported in less than 10% of cases.1 Medications most commonly associated with EM include antibiotics, antiepileptics, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Allopurinol, barbiturates, phenothiazines, statins, and tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors also have been linked to EM.2 Other causative factors include vaccines, autoimmune diseases, cancers, chemicals, and food additives.2,3 EM commonly is found on sunburned or injured skin.1,2

Patients with EM may present with prodromal symptoms of nausea, fever, malaise, cough, and headache 1 to 2 weeks before the development of skin lesions. Systemic symptoms do not occur in most cases of EM minor and may occur in cases of EM major.1-3 Early cutaneous EM lesions typically appear as pink or red papules surrounded by blanching and may look similar to papular urticaria or insect bites with a symmetrical distribution.1,2 Over time, these papules develop into target-like lesions with a central bulla or crust. Although skin lesions are frequently asymptomatic, mucosal lesions can be extremely painful.2

The upper extremities, especially the forearms and dorsal hands, are the most commonly affected areas. The trunk, palms of the hands, soles of the feet, neck, and face also may be affected.1-3 Patients with EM major may present with edematous, painful lesions in the oral, ocular, or genital mucosa that develop into bullae before becoming shallow erosions.2 Most episodes of EM resolve within 1 to 4 weeks without scarring, though hypo- or hyperpigmentation may be present.2,3

The histology of EM demonstrates apoptotic keratinocytes, superficial dermal edema, vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer, and perivascular inflammatory infiltrates.3,4 Immunofluorescence findings are nonspecific and may show immunoglobulin M (IgM), fibrin, and C3 deposited along blood vessels and fibrin and C3 deposited along the basement membrane.4

The diagnosis of EM is clinical and based on the patient’s history and physical examination.4 Clinicians should pay attention to potential symptoms of prior infection or a history of medication use that may be linked to EM.2,3 Although laboratory findings will not diagnose EM definitively, biopsy, serology, and direct immunofluorescence can be used to rule out other diseases, such as autoimmune blistering diseases and malignancies.2-4

Other conditions in the differential diagnosis include bullous pemphigoid, primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, pemphigus vulgaris, paraneoplastic pemphigus, fixed drug eruptions, hypersensitivity reactions, and pityriasis rosea. Bullous pemphigoid can be differentiated from EM using immunofluorescence and histology. Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis occurs more frequently in young children without a rash.3 Pemphigus vulgaris presents chronically, while EM is acute, and patients with paraneoplastic pemphigus typically have underlying malignancies. Fixed drug eruptions show temporal trends in medication history, and polymorphous drug eruptions result in plaques in sun-exposed areas. Hypersensitivity reactions commonly are localized to the face; urticarial lesions tend not

Erythema multiforme is the result of an immune response targeting small blood vessels in the mucosa and skin.

Continues on page 28

Dermatologic Look-Alikes

to last more than 24 hours; and pityriasis rosea presents with scaly, erythematous plaques.2,3

The general approach to treating EM is to provide symptomatic therapy and address the underlying cause, if possible.1-3,8 In cases of EM induced by drugs or infection, the offending medication should be discontinued or the infection treated.1,2,8 Topical steroids, oral antiseptics, and antihistamines can be used for acute EM.2 More severe EM cases may require intravenous fluid administration or systemic corticosteroids.2,3 In patients with recurrent EM caused by HSV, antiviral therapy with famciclovir, valacyclovir, or acyclovir for 6 months can help prevent EM recurrence.3

The patient in this case was diagnosed with recurrent EM secondary to HSV infection. Because his lesions were asymptomatic, the episode was treated with supportive care, and the lesions resolved after 2 weeks. He was started on acyclovir for prevention of future episodes of EM.

CASE #2 Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease

Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) is a highly contagious, primarily pediatric, viral infection caused by enteroviruses.9-11 Transmitted by respiratory, fecal, and oral droplets, the illness commonly results in oral lesions and vesicular eruptions affecting the palms, soles, and, occasionally, the buttocks and genitals.9,10

First described in the 1950s in Canada and New Zealand,12,13 HFMD initially was reported as a mild, self-limiting infection that resolved spontaneously.9,14,15 HFMD often occurs in outbreaks in the summer and fall or at summer camps and day care centers.9,10,15 Recently, HFMD has received more attention because of the discovery of unusual manifestations, such as dangerous cardiorespiratory and neurologic symptoms.15

HFMD occurs most commonly in children younger than 10 years of age, with the largest concentration in children younger than 4 years of age, and less commonly in adults.9,10,14 HFMD affects the sexes equally.9,10 In some countries, such as China, health professionals continuously monitor for HFMD. However, the true incidence of HFMD is underreported in most countries because cases with atypical manifestations are not diagnosed accurately.15 Although the disease is rarely fatal in the United States, complications of HFMD in China have resulted in higher fatality rates. Outbreaks and HFMD-related deaths also are more frequent in India, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Cambodia because of a lack of access to clean water.14

More than 90% of HFMD cases are caused by enterovirus A.15 Although coxsackievirus A16 is implicated most often, coxsackievirus A6 has been associated with more recent outbreaks worldwide and is associated with HFMD in adults.10,11,15 Since 2010, coxsackievirus A10 has played a greater role in HFMD outbreaks in Europe, Asia, and North America.14,15 Enteroviruses causing HFMD incubate for 3 to 6 days, and, although individuals with HFMD are most contagious in the first week of illness, the virus can remain in the stool for 4 to 8 weeks.9

The most severe cases of HFMD are caused by the enterovirus A71.9 Risk factors for developing severe HFMD include male sex, persistent high fever, young age, a lack of skin and oral lesions, increased neutrophil count, and steroid use.15 Additional risk factors for severe HFMD include living in a temperate climate and living in high-income countries, perhaps because of greater testing.16

Patients with HFMD commonly present with throat or mouth pain because of an eruption that affects the posterior oral cavity, buccal mucosa, or tongue. Malaise, low-grade fever, and reduced appetite may be present, along with a papulovesicular or maculopapular rash on the hands or feet.9,10 The

cutaneous lesions, which start as erythematous macules with a diameter of 2 to 6 mm, later develop into oval vesicles on an erythematous base and resolve after 7 to 10 days.9 Unusual cutaneous features can arise, such as pustules and bullae, desquamation of the palms and soles, eczema coxsackium, and hemorrhagic lesions.9 HFMD also may be accompanied by an exanthem on the buttocks, arms, and legs.10 Finally, severe complications including acute flaccid paralysis, encephalomyelitis, acute transverse myelitis, acute cerebellar ataxia, polio-like syndrome, and cardiorespiratory and pulmonary complications, are possible.9,10

Histopathology of HFMD demonstrates spongiosis and epidermal necrosis or ballooning degeneration of individual keratinocytes. Superficial perivascular inflammation and papillary dermal edema also are found. No multinucleated keratinocytes or inclusion bodies are found.17

TABLE. Erythema Multiforme vs Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease

Erythema Multiforme1-8 Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease9-18

Dermatologic presentation • Target-like, asymptomatic lesions • Patients may present with oral, ocular, or genital mucosal lesions and prodromal symptoms • 2- to 6-mm erythematous macules that develop into oval vesicles on an erythematous base

Epidemiology • More common in adults aged 20-40 years • More common in women • More common in children aged 5-10 years

Potential risk factors • Exposure to etiologic agents such as drugs and infections • Healthcare practitioners and individuals exposed to others with HFMD

Etiology • Infection in 90% of cases, commonly by HSV type 1 and

Mycoplasma pneumoniae • Exposure to certain drugs, vaccines, autoimmune diseases, cancers, chemicals, and food additives • Most commonly caused by coxsackievirus A16, A6, and A10 • Severe cases more likely caused by enterovirus A71

Characteristic location • Face, trunk, palms of hands, soles of feet, arms, and legs • Throat and mouth pain; lesions on palms of hands, soles of feet, buttocks, arms, and legs

Histology • Apoptotic keratinocytes, superficial dermal edema, vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer, perivascular inflammatory infiltrates • Deposits of IgM, fibrin, and C3 along blood vessels and basement membrane • Spongiosis, epidermal necrosis or ballooning degeneration of individual keratinocytes • No multinucleated keratinocytes or inclusion bodies • Superficial perivascular inflammation and papillary dermal edema

Diagnosis

Treatment • Clinical diagnosis with history and physical examination • Biopsies, serology, and direct immunofluorescence to exclude other diagnoses • Clinical diagnosis with history and physical examination • Polymerase chain reaction and serology to confirm the diagnosis

• Symptomatic with topical steroids, oral antiseptics, and antihistamines in acute cases • Address underlying etiologic cause • IV fluids and prednisone in severe cases • Antivirals in recurrent cases of HSV infection • Symptomatic with acetaminophen, ibuprofen, hydration

HFMD, hand, foot, mouth disease; HSV, herpes simplex virus; IgM, immunoglobulin M; IV, intravenous

Diagnosis of HFMD is based on the clinical presentation of symptoms. Polymerase chain reaction and serology can be used to confirm the diagnosis.9,10 Serology also may be helpful in differentiating the cause of the infection — coxsackievirus vs enterovirus 71 — and measuring IgG levels during recovery.10 A variety of diseases may mimic HFMD, including herpangina, which is caused by the same viruses as HFMD but can be differentiated by a lack of skin involvement because it is limited to the mouth.9,18 Similarly, aphthous ulcers and herpetic gingivostomatitis do not feature the widespread skin involvement seen with HFMD.9 Herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus also invoke characteristic rashes and can be differentiated from HFMD via biopsy.9,10 Behçet syndrome and pemphigus vulgaris also present with oral involvement; suspected cases warrant further investigation.9 Atopic dermatitis can be recognized based on its recurrent nature; scabies is pruritic; bullous impetigo frequently involves the trunk; and erythema multiforme characteristically features target lesions on the upper extremities.9 Other conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis include Kawasaki disease, viral pharyngitis, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and, if the patient has other risk factors, HIV.9,10

Dermatologic Look-Alikes

Mild cases of HFMD typically resolve spontaneously within 7 to 10 days; thus, symptomatic treatment with acetaminophen or ibuprofen is recommended.9,10,15 Hydration is essential because dehydration can lead to hospitalization.9 Immunoglobulins and antivirals have been used in severe cases, but more evidence is needed to support use of these treatments.9,10,15

In this case, the patient was treated with supportive care including intravenous fluids and ibuprofen. Her rash resolved after approximately 1 week. ■

Dina Zamil, BS, is a medical student at Baylor College of Medicine, Tara L. Braun, MD, is a resident in the Department of Dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine, and Christopher Rizk, MD, is a dermatologist affiliated with Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas.

References

1. Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(8):889-902. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05348.x 2. Trayes KP, Love G, Studdiford JS. Erythema multiforme: recognition and management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(2):82-88. 3. Samim F, Auluck A, Zed C, Williams PM. Erythema multiforme: a review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical features, and treatment. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57(4):583-596. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2013.07.001 4. Al-Johani KA, Fedele S, Porter SR. Erythema multiforme and related disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103(5):642-654. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.12.008 5. Spencer HE. Notes of a case of erythema multiforme. Br Med J. 1884;2(1236):465. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.1236.465 6. Lonjou C, Thomas L, Borot N, et al. A marker for Stevens-Johnson syndrome ...: ethnicity matters. Pharmacogenomics J. 2006;6(4):265-268. doi:10.1038/sj.tpj.6500356 7. Heinze A, Tollefson M, Holland KE, Chiu YE. Characteristics of pediatric recurrent erythema multiforme. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(1):97-103. doi:10.1111/pde.13357 8. Lerch M, Mainetti C, Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Harr T. Current perspectives on erythema multiforme. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54(1):177-184. doi:10.1007/s12016-017-8667-7 9. Saguil A, Kane SF, Lauters R, Mercado MG. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(7):408-414. 10. Guerra AM, Orille E, Waseem M. Hand foot and mouth disease. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Accessed February 12, 2021. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431082/ 11. Kimmis BD, Downing C, Tyring S. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease caused by coxsackievirus A6 on the rise. Cutis. 2018;102(5):353-356. 12. Robinson CR, Doane FW, Rhodes AJ. Report of an outbreak of febrile illness with pharyngeal lesions and exanthem: Toronto, summer 1957; isolation of group A Coxsackie virus. Can Med Assoc J. 1958;79(8):615-621. 13. Seddon JH, Duff MF. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease: coxsackie virus types A 5, A10, and A16 infections. N Z Med J. 1971;74(475):368-373. 14. Aswathyraj S, Arunkumar G, Alidjinou EK, Hober D. Hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD): emerging epidemiology and the need for a vaccine strategy. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2016;205(5):397-407. doi:10.1007/s00430-016-0465-y 15. Esposito S, Principi N. Hand, foot and mouth disease: current knowledge on clinical manifestations, epidemiology, aetiology and prevention. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;37(3):391-398. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3206-x 16. Liu Z, Meng Y, Xiang H, Lu Y, Liu S. Association of short-term exposure to meteorological factors and risk of hand, foot, and mouth disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):8017. doi:10.3390/ijerph17218017 17. Rapini RP. Viral, rickettsial, and chlamydial diseases. In: Practical Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Saunders; 2012;14:207-217. 18. Muzumdar S, Rothe MJ, Grant-Kels JM. The rash with maculopapules and fever in children. Clin Dermatol. 2019;37(2):119-128. doi:10.1016/j. clindermatol.2018.12.005

Don’t miss any of our Free CME/CE articles

Each month, The Clinical Advisor offers a free featured course on topics important to nurse practitioners and physician assistants

Please visit our CME/CE section at

ClinicalAdvisor.com/CME-CE-features

LEGAL ADVISOR

CASE

Nurse Sues Over Sexual Harassment

Nurse in surgical unit quits after years of sexual harassment by a supervisor.

BY ANN W. LATNER, JD

When Ms B was hired to work as a nurse in a surgical center, she had been out of school for a short time and the surgical center was the perfect place to gain experience and grow. The surgical center was under the direction of Dr K, who was a contract employee. He had 2 separate contracts with the surgical center: 1) to provide anesthesia services and 2) to serve as the surgical center’s medical director.

Dr K took a great interest in the new employee, as he did with many of the younger nurses — often joking around with her, sometimes inappropriately. For a time, Ms B tried to overlook this behavior, but the doctor’s actions increasingly made her feel uncomfortable. He shared with her his previous sexual conquests and how he enjoyed being the dominant man with a submissive woman.

He insinuated that she should engage in a submissive relationship with him and that she should get a tattoo signifying his “ownership” of her. He would write a “sex word of the week” on Ms B’s calendar. He also passed around an unflattering picture of Ms B on her hands and knees, while making inappropriate comments.

The behavior was upsetting and confusing to Ms B, especially because Dr K was sometimes kind and helpful and acted appropriately. Then there were instances where he would hug her against her will, pull her hair, push her into a corner, or try to kiss her. The surgical center had a mechanism in place for making complaints, both anonymous and formal, but Ms B was afraid that reporting Dr K would have negative consequences for her career.

After working at the surgical center for more than 2 years, Ms B finally filed an anonymous complaint against Dr K. Afterward, his behavior improved for a few months, but soon he was back to making inappropriate remarks to Ms B.

Ms B eventually filed an official complaint well over 3 years after the harassment began. The surgical center’s management conducted an investigation and its medical executive committee

After her resignation, Ms B sued Dr K for battery and emotional distress as well as the surgical center for a hostile work environment and constructive discharge.

Cases presented are based on actual occurrences. Names of participants and details have been changed. Cases are informational only; no specific legal advice is intended. Persons pictured are not the actual individuals mentioned in the article.