Post- Pregnancy

Mood & Sleep

Research based, post-pregnancy formula to support positive mood, calm and sleep.

EDITOR

Hayley McMurtrie

E: communications@nzcom.org.nz

ADVERTISING ENQUIRIES

Hayley McMurtrie

P: (03) 372 9741

MATERIAL & BOOKING

Deadlines for December 2024

Advertising Booking: 1 November 2024

Advertising Copy: 11 November 2024

Welcome to Issue 114 of Midwife Aotearoa New Zealand

At the time of writing the College is leading a Class Action on behalf of members in the High Court. This is set to become a significant moment in the history of New Zealand midwifery and of the College. We do not know what the outcome will be, but we do know we can be very proud of all of those who have taken the stand on behalf of the profession and we take this opportunity to thank them all. Whilst primarily the debate relates to LMC midwives, midwifery is one profession, and regardless of how and where midwives work with women and whānau, if all midwives are supported and their work valued and respected, the whole profession will be better for it.

There is also much discussion within Te Whatu Ora and within this issue of Midwife Aotearoa about the continuity of care model. As we approach this period of potential change it is beneficial to remember the beginnings of this model and the woman-led, whānau-centred core of the midwifery model that we are lucky enough to have in Aotearoa today.

Change is also reflected in the number of practice updates we have in this issue, including prescribing updates (p.12), Vitamin D recommendations (p.14), Pulse Oximetry requirements (p.15) and TXA (p.16). The College midwifery advisors are available to assist with any clarification around what these updates mean for you in practice, whether you are working in a core or LMC environment.

Spring is in the air and here at the College we are preparing to welcome many of you to the Joan Donley Research Forum (p.9), a fabulous opportunity to see first-hand the quality research that is taking place in Aotearoa, as well as to catch up with colleagues in the wonderful New Plymouth.

Ngā mihi nui, Hayley Square

HAYLEY MCMURTRIE

COMMUNICATIONS MANAGER

Email: communications@nzcom.org.nz

from the co-presidents

"Ki te tika te tauira, ka tika te whāia mai' If the example is appropriate, then they will follow in the appropriate manner

- Sir Timoti Karetu (Ngāti Kahungunu, Tuhoe)

'Models of care’ is an interesting phrase. For me personally, it’s lacking in clarity or substance. And despite its firm embedment in the modernday midwifery vernacular, it’s not possible to know what difference our current ‘model of care’ has made to outcomes for whānau. Especially for the whānau whose stories filled the pages of the latest PMMRC report.

I don’t believe the solutions lie in developing or designing new ‘models of care’. In my experience, these constructs aren’t what keep people accountable. True accountability and responsibility have nothing to do with buzz words, and everything to do with something more deeply, intrinsically human.

In this sense, responsibility refers to one’s ability to respond. As midwives, our ability to respond is, quite literally, in our hands. It’s also contained within the vast body of mātauranga we’ve acquired either through the passing down of intergenerational wisdom, or our modern midwifery education, or both.

In te ao Māori, we speak of tīpuna and mokopuna in the same vein; they are one and the same. Tīpuna doesn’t just refer to ancestors passed, but ancestors yet to come.

And irrespective of whether we share biological whakapapa with whānau we’re caring for, every mokopuna is valued equally and as if they’re our own.

So it’s our tīpuna and mokopuna that I and other Māori midwives look to for guidance in our practice. And it’s these mokopuna we respond to. We don’t need words like ‘continuity’ or ‘partnership’, because our values and senses supersede these words; the

behaviours are inherent, imprinted in our DNA.

In other words, Māori midwives are already working in ways that meet the needs of whānau and have been for some time now. And naturally, we’re best positioned to share our perspectives and ways of being.

I’ve cared for my own whānau, including my own daughter, as my mokopuna have entered this world. Had I ignored my own inner compass and followed the so-called professional boundaries outlined to me as a midwifery student, I would have been denying the very fabric of my being and, in our world, nothing could be more damaging.

The solution does not lie in the development of new models. The solution lies in ensuring that the system in which midwives work enables us to be guided by our tipuna so that we are not constrained in the way we can practice. Whether working at policy level in Te Whatu Ora, or in the community alongside birthing whānau, we need to value and respond to each mokopuna as if they are our own. Square

‘Models of care’ is something of a buzz phrase in health this year. However it can mean many things, depending on the setting in which it is used.

Within the International Confederation of Midwives’ consensus statements it refers to a philosophy of care which centres the needs of the recipient of care within their wider cultural, social and psychological context. Whereas within our own recently released Government Policy Statement on Health 2024-2027, the term refers to wider system settings which could enable such care to be provided.

The latest PMMRC report states in no uncertain terms that if we continue to do what’s already been done, nothing will

change. Ensuring the cultural responsiveness of the health system and providing culturally safe care at an individual practitioner level are essential things we can do to play our part in addressing inequities.

Rethinking service delivery, including the role so-called ‘models of care’ have to play, is more pressing than ever and who better placed to design these models, than midwives?

The Midwifery Insights survey, a joint project between Kahu Taurima and Te Whatu Ora, provided midwives with this opportunity - to reflect and feed back on potential models of care across different maternity settings and what those could look like. I hope all of you had your say.

We already have a strong, legislated foundational model of midwifery care based on the principles of continuity, partnership and autonomy. These principles are the core of our work as midwives, however, within this national model we also have examples of local models that recognise and acknowledge the uniqueness of different communities and the extent to which needs vary between groups.

But what does the concept mean to you and your colleagues? As a staff midwife working at a maternity facility, this might look and feel different to the commonly referenced ‘model of care’ often associated with LMC communitybased care. In reality, staff midwives and LMC midwives are interconnected and rely upon one another to deliver a service; both are equally integral to the design of any model. So what is the model of maternity care you work within? And what’s great about it?

What do whānau/families tell you about their experiences of the model you’re currently working in?

I believe a sustainable and effective model of midwifery care must include all of midwifery across community and hospital settings and take into consideration local midwives’ availability and local facilities. It must also be developed in partnership with the whānau/ families you care for, keeping their needs at the centre. Square

Bea Leatham

Debbie Fisher

CLASS ACTIONOUR DAY IN COURT

The College’s legal case against the government is being heard in the High Court in Wellington from 5 August for a six-week period. The proceedings allege breach of contract; breaches of equitable representations by the government; and also claim unlawful gender-based discrimination under the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990.

The circumstances which have led to the current case being taken date back to the College’s initial judicial review claim against the Ministry of Health (the Ministry) in 2015 and include two subsequent Settlement Agreements between the College and the Ministry, one of which is the centre of the present breach of contract claim.

The current case is being taken as a class action, with over 1,400 midwives participating. It is being funded by an international class action funder. As the case and the matters under dispute are currently before the court, the College is limited in what it can publicly say about it. In the fullness of time, we will ensure that there is a coherently documented narrative of the convoluted chain of events that have brought us to this point, for the record.

The College’s decisions to pursue legal actions against the Ministry have not been easy decisions to make. These decisions have only ever been motivated by the desire to ensure that the profession is treated fairly and equitably – and so that we can continue to recruit midwives and retain them in the workforce, under conditions enabling them to provide the care that women and whānau need and deserve. Throughout every step, foremost in the board’s decision-making processes has been consideration of the profession’s future, including those who are new in our profession or yet to join it. Although MERAS has the mandate to negotiate on behalf of employed midwives, in the absence of any other entity with the mandate to negotiate for LMC midwives, the College has been forced to take

from the chief executive, alison eddy

Preparation for the case to be heard in court has been intense and involved the work and commitment of many. Heartfelt thank you to the mediation team witnesses Karen Guilliland, Nicole Pihema and Deb Pittam, all of whom have all been involved throughout legal and Settlement agreement processes which lead to these proceedings.

the issues forward by standing up for working conditions that will support retention, sustainable high quality equitably accessible care, and pay which fairly recognises the responsibilities and skills LMC midwives hold.

Preparation for the case to be heard in court has been intense and involved the work and commitment of many. Heartfelt thank you to the mediation team witnesses Karen Guilliland, Nicole Pihema and Deb Pittam, all of whom have all been involved throughout legal and Settlement agreement processes which lead to these proceedings. The breadth of your testimony, traversing content from the 1993 Maternity Benefits Tribunal in Karen’s case, to the present, including Nicole’s description of her practice as a Māori midwife in rural Te Taitokerau demonstrated the intricate and complex nature of the issues which the case is seeking to resolve. To our midwife witnesses, Yvonne Hiskemuller, Fiona Hermann, Bex Tidball, Sheryl Wright, Kendra Short the profession thanks you for your courage and willingness to put yourself on the record, with at times moving testimony about the work of midwives.

These midwives provide us with a great example of parrhesia (an ancient Greek word which means speaking truth to power). Midwifery has never been shy of speaking truth to power in advocating for women’s

rights, and in this case, these midwives are speaking up for our own profession’s rights to be treated fairly. I also acknowledge and thank the many other midwives; including Sally Pairman (who provided a written brief of evidence to the court), while not appearing in court, generously assisted our legal team with their time and knowledge.

To our legal team – including Robert Kirkness, Dr Mark Hickford, Kate Cornegé, Kerryn Webster, Taz Haradasa, Nerys Udy, Rosalie Reeves and Carla Humphrey – your work and commitment to bring the case to this point has been amazing to observe and bear witness to. The case preparation has involved hours and hours of complex and detailed work, combing through documents, drafting and redrafting briefs, critical thinking and mind mapping to draw the intricate web of facts and evidence of events which have occurred over nearly a decade (and even prior) into a comprehensive and coherent case. Whatever the outcome, members can be assured that with the calibre and fortitude of our midwife witnesses, and expertise of the legal team who have represented us, we have most certainly put the best possible case forward.

By the time this edition of the magazine goes to print, it is expected that the court hearing will be in its final weeks. Most of the evidence will have been presented with witnesses examined and cross examined. Her Honour Justice Cheryl Gwyn, who is presiding over the case, will then retire to consider the evidence. Her judgment is anticipated to be delivered some time in 2025.

I sincerely hope that once this case is concluded, the future is set for self-employed,

publicly funded midwives’ rights to negotiate fair and reasonable working conditions and for that work to be valued fairly. I hope that the College and its members will be able to draw a line in the sand, leaving this challenging decade behind us and, for the sake of those whom we care for, be able to look forward to a future in which our profession can flourish and thrive. Square

governance of the college

For some months now, the College’s board has been deliberating on our current governance model and how well it is serving our organisation’s needs. This discussion commenced as the board was developing our current strategic plan and continued as the recommendations and themes from the cultural review were considered. The work included reviewing the governance models of a range of other professional membership associations and unions.

Our current board is highly unusual in that it is large and appointments are entirely on a representative basis. It includes a total of 25+ individuals:

• Kuia and Elder

• two co-presidents

• 11 regional chairpeople (two for Auckland and one each for other regions)

• two Ngā Maia representatives

• two Pasifika representatives

• two midwifery student representatives

• up to four consumer representatives

• the College CE

• an ex-officio education consultant

• an independent Finance Committee member

There are often additional ex-officio (non-voting) attendees at board meetings too, including incoming or outgoing chairs, sub-regional chairs and staff members. It is not unusual for there to be 30 or more people in attendance at any given meeting.

Although some aspects of our current model are highly valued (including broad representation which brings a diversity of perspectives and skills, networking and relationships), there are some aspects that don’t work so well. A considerable portion of the time spent at board meetings is on information sharing rather than governance-related matters. This means board meetings, which currently take place three times a year in person, take two full days each. The turnover of board membership is high as regional chair roles commonly have two-year terms. In the 20+ years I have worked for the College and attended almost every board meeting, I have never attended a meeting whereby exactly the same people were in attendance at consecutive meetings. This can lead to challenges with decision making as important historical context can be lost from meeting to meeting.

Although our current model served us well as a grassroots and fledgling organisation in our past, it is time to ask ourselves whether it is still serving our needs as best it can. Over the years we have grown and matured as an organisation. We now have over 4,000 members and hold significant responsibilities for the delivery of contracted workforce support services. As the College is an Incorporated Society with charitable status, the board holds legal and financial accountability for the College and, with such a large board, it is sometimes challenging for each board member to maintain a line of sight to this accountability. Because regional chairs form a critical part of our national governance structure, they hold dual responsibilities with both regional and national governance accountabilities, which can also be challenging. It is therefore timely to also consider whether we have the best model and support for our regional structures.

As for all organisations, effective governance is essential to steer the College at a strategic level. It strengthens our organisation, and helps us to manage the risks and challenges that we face. Good governance will ensure that we are effective in meeting our members’ needs and in achieving our mission and objectives. The board has agreed to commission a report on our governance model which will consider options for change for the future.

This work will be undertaken over the coming months within a te Tiriti partnership, and a report is planned to be tabled at the board’s November meeting. Any recommendations for change will be brought to members for their views and perspective before any changes are agreed or implemented. Change can be exciting but also challenging; however, we owe our members the assurance we can adapt and change in response to our organisation’s needs, to make sure we are fit for purpose for today’s world. Square

Although our current model served us well as a grassroots and fledgling organisation in our past, it is time to ask ourselves whether it is still serving our needs as best it can.

your college

MSR and education administration

Alys Pullein has joined the College as Administrator for Midwifery Standards review and Education. She spent several years working in the UK before returning to her Aotearoa home. Alys takes over from Saili who held this position for fourteen years. Saili will be missed by her colleagues and the reviewers and educators throughout the country. Square

college statement on Abortion Reversal

At its July meeting, the National Board approved a statement about a non-evidence-based and potentially harmful practice known as'abortion reversal' which has been reported as having arrived in Aotearoa. The statement has been published on the College’s website, in the practice guidance section. Square

eLearning

By the time members receive this issue of Midwife Aotearoa the College’s long awaited eLearning programme will be live. We are excited to announce the first two courses available through the platform: Practicalities of Mentoring in Aotearoa; and Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Many more courses are in progress and will be launched in the coming months. Square

maternity care for refugee women

The inaugural Refugee Health Community of Practice forum was held at Te Āhuru Mōwai Refugee Resettlement Centre in Māngere on 20-21 June. Midwives Claire MacDonald, Shaqaiak Masomi and Amber Izzard were invited as speakers at the forum. Their presentation was about the College’s work on supporting access to and acceptability of maternity care for former refugee women, and the e-learning module about midwifery care for former refugee whānau which Te Whatu Ora has funded the College to develop. Along with Shaqaiak and Amber, the subject matter expert midwives informing the education development are Sonia Azizi and Louise Nibarema. The forum was an opportunity for stakeholder engagement with the refugee health community to inform the e-learning module, and for the College team to make

Above: Attendees at the inaugural Refugee Health Community of Practice forum in June.

connections and learn about the amazing mahi that is being done across the motu to support former refugees into their new homes and lives in Aotearoa. Square

upcoming workshops

The following dates are available now for face-to-face workshopsbook online www.midwife.org.nz to secure your place.

Tāmaki Makaurau | Auckland

MESR Midwifery Emergency Skills Refresher: 13 September, 18 September, 20 November A-Z of Perineal Care: 3 October

Ōtautahi | Christchurch

A-Z of Perinatal Care: 14 October

Dotting the I's in a Digital Age: Record Keeping for Midwives: 4 November

Te Whanganui a Tara | Wellington A-Z of Perineal Care: 11 November

Ahuriri | Napier

Dotting the I's in a Digital Age - Record Keeping for Midwives: 8 October

Kirikiriroa | Hamilton

MESR Midwifery Emergency Skills Refresher: 8 November

A-Z of Perineal Care: 25 November

Ōtipoti | Dunedin

Dotting the I’s in a Digital Age - Record Keeping for Midwives: 19 November

Maruawai | Gore

Dotting the I’s in a Digital Age - Record Keeping for Midwives: 20 November

bulletin

midwifery insights survey

Under its Kahu Taurima work programme, Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora has recently undertaken a survey to inform possible future funding models for community midwives. Alternative contract options may be developed, however, the Primary Maternity Services Notice will remain as an option for LMC midwives who wish to continue working as they are now. Kahu Taurima also aims to address the reality that some whānau are not currently able to access LMC midwifery care, and there are also inequities in whānau choice, and outcomes for māmā and pēpi. Any new alternatives need to be sustainable for midwives, and achieve improved access, experience and outcomes for whānau.

The purpose of the survey was to learn what midwives value in alternatives to the current funding model, to inform the development of new national settings for enhanced workforce support for community midwifery and to achieve improved access, outcomes and experiences of care for whānau. Health NZ have confirmed that continuity of care will continue to be a cornerstone of any future Kahu Taurima service. Midwives are a vital and valued workforce within our health services and will continue to lead in the provision of primary maternity care.

The College hosted two member webinars

in July to explain and discuss the survey and both webinars were well attended with strong engagement from midwives. Health New Zealand have agreed to share the survey results with the College. Square

national perinatal pathology service online training

The National Perinatal Pathology Service will be inviting midwives to participate in their new online course that is being launched in the last quarter of 2024. The service has worked with subject matter expert, Dr Vicki Culling, to develop an online course that provides information and resources to health professionals, who interact with bereaved parents and whānau after the death of a baby, and introduce the post-mortem procedure to them.

The course provides information about what the perinatal post-mortem entails and the referral process, and participants hear from perinatal pathologists from around the country. It also provides information on discussing post-mortem in a supportive, culturally safe way. The course includes interviews with bereaved whānau – some who chose to have a post-mortem for their baby, and some who chose not to and why.

The approximately 5 hour course is free for health professionals and can be used as CPD.

Register your interest at perinatalpathology@ adhb.govt.nz Square

breastfeeding apps

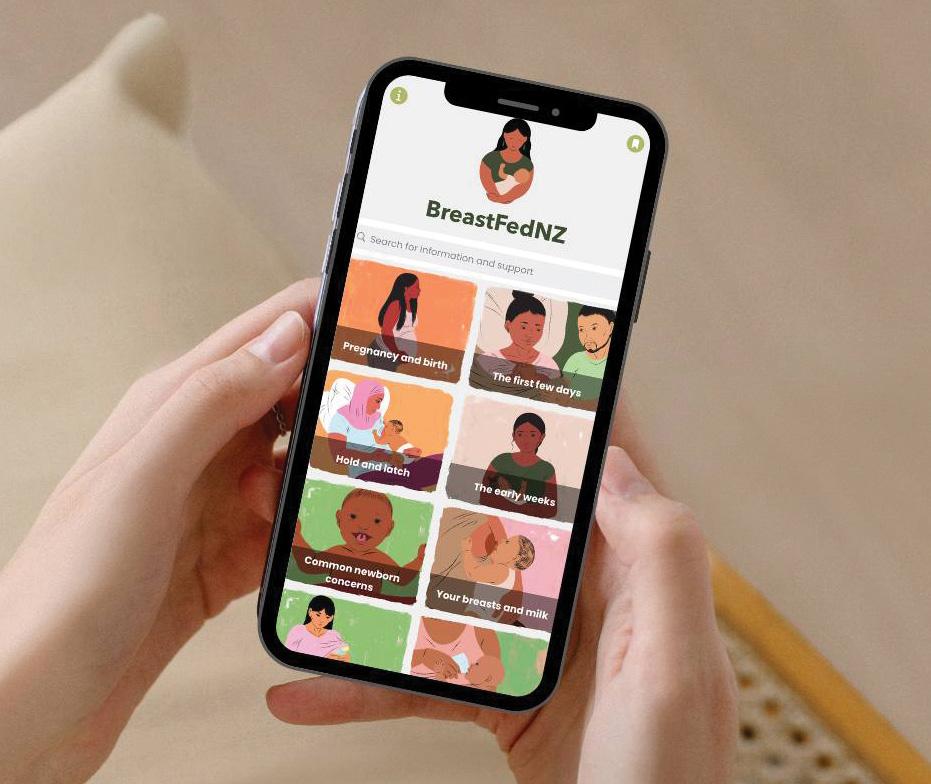

The BreastFedNZ app has had a major overhaul and has been relaunched. The project was originally initiated by the five Midland DHBs with midwife and lactation consultant Karen Palmer developing content as part of a wide consultation process. The easy to use resource is designed for consumers and health practitioners - particularly midwives.

The updated Mama Aroha app, developed by midwife and lactation consultant

Amy Wray in collaboration with the New Zealand Breastfeeding Alliance and Hāpai Te Hauora, puts breastfeeding information into a user-friendly format for health professionals, mothers and whānau. Both apps are available for download from Google Play and App store. Square

telehealth (COVID) number is no longer active

The Covid Telehealth clinical advice line was decommissioned on 1 July 2024. Guidance for Health Professionals can now be found on the Health NZ website https://www.tewhatuora. govt.nz/health-services-and-programmes/ infection-prevention-and-control/ Square

CE Alison Eddy with Laura Aileone, Chief Midwife, Health NZ

BreastFedNZ App

jane cartwright is moving on from the new zealand breastfeeding alliance

After seven years as CEO of the New Zealand Breastfeeding Alliance (NZBA), Jane is now leaving this role to take on a new part-time role as Regional Integration Team Lead with Te Waipounamu. Jane's relationship skills, commitment to strengthening communities, and dedication to working in partnership, have supported the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative to flourish. This year Jane became a Member of the NZ Order of Merit (MNZM), for her services to health governance. The College is sorry to see Jane leave the NZBA, but we wish her all the best for her new role. Square

chief midwife appointed

Laura Aileone has recently been appointed as the new Chief Midwife within the Clinical leadership directorate in Health New Zealand. As Tāngata o Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa, Ngāti Hāmoa, Laura is passionate about addressing the inequities in our healthcare system, and ensuring both clinical and whānau voices are at the heart of midwifery service design and delivery. Having spent over 20 years in healthcare as a midwife, in midwifery and maternity service development, and in leadership and advisory roles across Aotearoa, Laura brings a wealth of experience to the role. The College CE and Advisors have met with Laura and look forward to working with her in this newly permanent role. Square

thank you deb

The College acknowledges the work of Deb Pittam who was seconded into the Interim Chief Midwife position when it was established last year. Deb led the profession in this role throughout particularly challenging times, as the health system adjusted to its new structure and with midwifery workforce shortages ever present. Throughout her tenure in the Chief Midwife role, Deb displayed innovative problemsolving skills, clear leadership and advocacy for women and whānau who access midwifery and maternity services, as well as for the midwifery profession. The profession thanks you for your service and wishes you all the best for the future. Square

Deb Pittam, former interim Chief Midwife

VIOLET CLAPHAM MIDWIFERY ADVISOR

PRESCRIBING UPDATE FOR MIDWIVES

Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora has recently published the latest version of the Pharmacy Procedures Manual (available at www.tewhatuora.govt.nz), which sets out rules and requirements for prescribing in Aotearoa New Zealand.

REINSTATEMENT OF CO-PAYMENTS ON PRESCRIPTIONS

The Government ended universal free prescriptions on 15 July 2024, with the $5 copayment restored for most New Zealanders. However, prescriptions will remain free for people with Community Services Cards,

people under 14 and people aged 65 and over. The Prescription Subsidy Card will continue to limit the total number of co-payments an individual or family will pay to 20 per year (the pharmacy year is 1 February to 31 January).

MIDWIFERY PRESCRIBING

Registered midwives take responsibility for the care of a woman throughout her pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal period. Registered midwives may claim maternity, pharmaceutical and other related benefits relevant to pregnancy and childbirth. Midwives are not able to prescribe for an underlying medical condition, such as asthma or hypertension but they may prescribe for the treatment of a patient under their care:

• any pharmaceutical for the woman, providing it is during pregnancy, labour and the postpartum period up to six weeks

• for the baby during this six-week period

• morphine, tramadol, fentanyl and pethidine, but no other controlled drug

As per the College’s consensus statement on Midwife Prescribing, midwives are expected to have knowledge regarding the effects, side effects, interactions and contra-indications of the drugs prescribed. The College expects midwives to prescribe within the level of their knowledge and expertise. However, midwives are not expected to prescribe for all antenatal, labour, birth and postnatal situations.

In relation to a preterm baby, the Midwifery Council defines the six-week postpartum period as commencing from the expected date of birth rather than the actual date of

birth. In other words, for preterm babies, the postpartum midwifery role may extend beyond six calendar weeks.

LEGAL AND CONTRACTUAL REQUIREMENTS OF A PRESCRIPTION FORM

The information supplied on a prescription form must be legible and indelible (written in pencil, for example, is not acceptable) and must include all the following:

• Prescriber’s usual signature in their own handwriting (not being a facsimile or other stamp) – subject to the Signature Exempt Prescription provisions

• The date on which the prescription form was signed

• Prescriber details, which include:

- Prescriber’s full name

- Prescriber’s physical work address, or postal address for those who do not have a place of work

- Prescriber’s telephone number

• Patient details, which include:

- Surname and each given name of the patient

- Physical address of the patient

- Patient’s date of birth if the prescription form is for a child under 14 years

• Pharmaceutical details, which include:

- Name of the pharmaceutical

- Strength of the pharmaceutical to be dispensed (where appropriate)

(0-13 years)

(14-17 years)

(18-64 years)

- Total amount of pharmaceutical or the total period of supply to be dispensed - Dose and frequency of the dose for internal pharmaceutical

- Method and frequency of use for external pharmaceutical

The Temporary Authorisation from Signatures on Prescriptions without NZePS (i.e., no barcode), which has been in place since October 2022, continues to allow non-NZePS signature-exempt prescriptions to be issued if the requirements under the Temporary Authorisation are met.

Midwives are entitled to verbally communicate prescription forms in an emergency situation.

MIDWIFE PRESCRIBING RULES FOR CONTROLLED DRUGS (CLASS B AND CLASS C)

Within the controlled drug categories, midwives may only prescribe tramadol, pethidine, morphine or fentanyl. The maximum period of supply is one month, and every controlled drug prescription form must state ‘for midwifery use only’. Midwives may not prescribe any other controlled drugs, such as codeine and benzodiazepines. Controlled drugs must be first dispensed no more than four days after the date of the prescription and repeats must be dispensed no more than four days after the previous supply is exhausted.

PRACTITIONER SUPPLY ORDERS

Midwives are entitled to use a Practitioner's Supply Order (PSO) form to order pharmaceuticals within their scope of practice. PSOs must be supplied in accordance with Pharmaceutical Schedule Rules. Pharmac publishes a list of funded pharmaceuticals which may be obtained by a midwife on a PSO. The list is updated monthly and can be found on the Pharmac website (www.pharmac.govt.nz). Square

YOUTH (AGES 0 TO 13 YEARS) – Y CODE

ADULT (AGES 18 TO 64 YEARS) – A CODE

VIOLET CLAPHAM MIDWIFERY ADVISOR

PRACTICE UPDATE –VITAMIN D

Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora have published a new national maternity companion statement titled: Companion Statement on Vitamin D and Sun Exposure in Pregnancy and Infancy in Aotearoa New Zealand – Tauākī Āpiti mō te Huranga Hihirā me te Huaora D i te Hapūtanga me te Nohinohitanga i Aotearoa. This statement, developed by a multidisciplinary steering group with sector-wide consultation, supersedes previous versions. The full version is available on www. tewhatuora.govt.nz

The Companion Statement should be read in conjunction with the Consensus Statement on Vitamin D and Sun Exposure in New Zealand (Ministry of Health and Cancer Society, 2012), the Ngā Paerewa Health and Disability Services Standard 8134:2021 (Standards New Zealand, 2021) and the corresponding sector guidance.

Midwives are advised to read the companion statement and supporting content to comprehensively understand this update and implications for practice. The companion statement is expected to be implemented within maternity services and professional practice to the best of one’s ability, ensuring clear documentation and rationale when there is an inability to do so. The key changes for midwives to be aware of are:

• Universal vitamin D supplementation is now recommended for all exclusively or partially breastfed babies

• Supplementation for infants should be commenced by four weeks of age and continue until 12 months of age

• The recommended daily supplement for babies is 400 IU colecalciferol 188mcg/mL orally per day (1 drop)

• Midwives should screen pregnant women to determine risk of vitamin D insufficiency

• Supplementation should be offered to pregnant women if they have any of the following risk factors:

- Live south of Nelson during winter or spring

- Naturally dark skin tone

- Spend limited time outdoors and/or have minimal sun exposure due to religious, cultural, personal or medical reasons. Square

References available on request.

practice points for midwives

DEFINING INSUFFICIENCY/ DEFICIENCY

In this companion statement Vitamin D insufficiency is defined as a level of <50 mmol/L, Vitamin D deficiency is defined as a level of <25 mmol/L.

MATERNAL HEALTH OUTCOMES

There is some evidence to suggest the health outcomes, gestational diabetes and pre-eclampsia. are linked to vitamin D insufficiency.

INFANT HEALTH OUTCOMES

There is sufficient evidence to suggest bone health is linked to adequate optimal vitamin D status. There is some evidence indicating the health outcomes, low birth weight, dental caries and acute respiratory infections are linked to vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency.

Discuss the following with whānau during pregnancy and infancy:

Maternal and infant risk factors for vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency; Testing asymptomatic pregnant people and infants for vitamin D insufficiency is not routinely recommended; Testing may be appropriate for: pregnant people with a known history of vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency; pregnant people with unexplained raised serum alkaline phosphatase, low calcium phosphate, atypical osteoporosis, unexplained bone pain, unusual fractures, or other evidence suggesting metabolic bone disease; infants presenting with seizures where hypocalcaemia is implicated, or unexplained raised serum alkaline phosphatase.

Recommendations for supplementation

Pregnancy: Offer vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy if they have any of the listed risk factors. Prescribe 400-800 IU Colecalciferol 188 microgram/ mL oral liquid per day. Individuals with all three risk factors during pregnancy may be at a higher risk of vitamin D deficiency and testing may be considered. Where vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency is confirmed through testing, follow the advice from New Zealand Formulary.

Infancy: Offer to prescribe vitamin D supplements to all exclusively or partially breastfed babies. Supplementation should begin by 4 weeks and continue until 1 year of age. Prescribe 400 IU Colecalciferol 188 microgram/mL oral liquid per day.

Sun safety advice: Discuss the following messages with whānau where appropriate: Follow the same sun safety messages as for the general population during pregnancy; Always avoid sunburn; There is no safe threshold of UV exposure from the sun that avoids skin damage and ensures sufficient vitamin D synthesis; Sunscreen should only be used on small areas of a baby's skin and should not be the only form of protection from the sun: use shade, protective clothing, broad-brimmed hats, and sunglasses; Young children, once mobile, should follow the same sun safety advice as for the general population.

RISK FACTORS IN PREGNANCY

There is an increased risk of vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy if the pregnant person has any of the following: naturally dark skin tone; live south of Nelson/Marlborough during winter or spring; spend limited time outdoors and/or have minimal sun exposure due to religious, cultural, personal or medical reasons.

SUPPORTING BREASTFEEDING

Breastmilk is the ideal food for infants and contains antibodies which protect infants against illness whilst providing all the energy and nutrients that the infant needs for the first months of life. There is strong evidence on the benefits of breastfeeding for both the mother and infant. Everyone should be encouraged and supported to breastfeed.

FURTHER RESEARCH

Further evidence is important to strengthen the understanding of vitamin D and sun exposure on health outcomes in pregnancy and on infants.

BRIGID BEEHAN MIDWIFERY ADVISOR

NEW NATIONAL GUIDELINES FOR NEWBORN PULSE OXIMETRY SCREENING

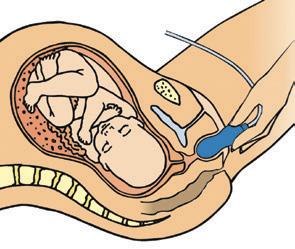

Pulse oximetry is a simple, non-invasive screening tool that can detect critical congenital heart disease in newborns before symptoms appear. Health NZ I Te Whatu Ora has published a new national guideline, titled Pulse oximetry screening guidelines for newborn babies, to provide a consistent and evidence-based protocol for practitioners to follow. The guideline supports local health services, including all midwives providing birth and early postnatal care, to implement this screening.

Midwives are recommended to familiarise themselves with the guidelines, along with the algorithm, data collection form, and an information sheet for parents and whānau, all of which are available on the Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora website.

Developed for health practitioners involved in the assessment, screening, and treatment of newborns in Aotearoa New Zealand, these guidelines have been endorsed by the National Maternity Monitoring Group. Districts are responsible for implementing these guidelines and ensuring they meet their obligations under Te Tiriti o Waitangi to deliver equitable services.

The College was represented on the guideline development group and the draft guideline underwent member consultation. The College advocated for their implementation to enable screening to be equitably available to all whānau regardless of birth setting. This includes addressing challenges regarding access to appropriate

pulse oximetry equipment for midwives providing homebirth services.

KEY POINTS FOR MIDWIVES

• Motion-tolerant pulse oximeters that measure functional oxygen saturation levels are recommended.

• Parents, whānau, and guardians of well newborns born at 35 weeks gestation or more should be offered screening.

• Depending on the birth setting, the optimal time for the pulse oximetry screen is between 2 and 24 hours of age.

• Health practitioners should provide full, accurate, and unbiased information to help parents make an informed decision, ideally before the baby is born.

• Test results should be documented in the newborn’s clinical notes. If screening is declined, this should be recorded in both maternal and newborn clinical notes.

• Babies should not be discharged from a facility unless their oxygen saturation is greater than 95%. If their oxygen saturation is less than 95%, refer to the algorithm.

• For home births, screening should be undertaken before the midwife leaves the home, where possible.

The College understands that districts are at different stages of implementing this guideline. We recognise the importance of equitable access to this screening and are advocating for locally designed strategies to ensure that the place of birth does not become a barrier.

BRIGID BEEHAN MIDWIFERY ADVISOR

PRACTICE UPDATE: TRANEXAMIC ACID (TXA) IN POSTPARTUM HAEMORRHAGE MANAGEMENT

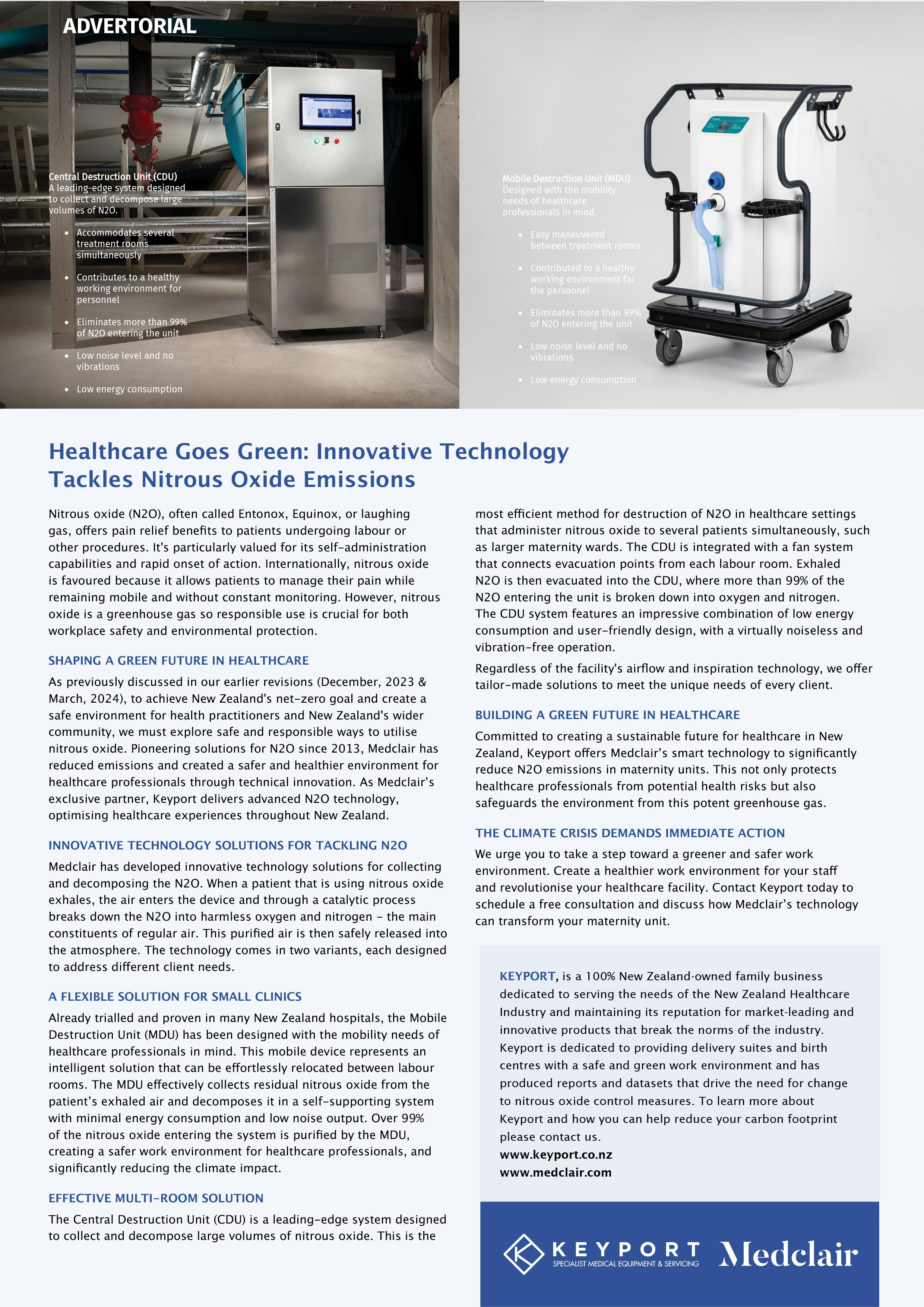

In 2022, the Ministry of Health | Manatū Hauora (MOH) published the Postpartum Haemorrhage (PPH) Consensus Guidelines, accompanied by the Treating Postpartum Haemorrhage poster. A notable update in these guidelines included specific recommendations for the administration of Tranexamic Acid (TXA) in the early management of PPH. This change means that midwives are now prescribing and administering TXA as part of the early recognition and proactive management of PPH. This article serves as a recap and practice update for TXA prescribing and administration, providing practical points to ensure effective and safe use in various practice settings.

WHAT IS TXA?

Tranexamic Acid (TXA) is an antifibrinolytic drug that inhibits the enzymatic breakdown of fibrin blood clots – known as fibrinolysis. It has been widely used in medical fields, including emergency trauma and surgical care. The 2020 WHO WOMAN (World Maternal Antifibrinolytic) trial significantly influenced PPH management worldwide. This large, randomised, controlled trial, involving over 20,000 women in 21 countries, provided robust evidence supporting the use of TXA in PPH management. The trial demonstrated that TXA reduces the risk of death due to bleeding by 30%, without increasing the risk of thromboembolic events, and reduces the risk of urgent surgery to control bleeding by 35%, thus shaping global and national guidelines, including those in Aotearoa.

KEY FACTORS

The 2022 National PPH guideline stresses the need for immediate action without

delay when PPH is suspected, including early recognition and assessment with swift management, including drug treatment. It is important to know that TXA is most effective when administered early, alongside other management and treatment measures. It's crucial to understand that TXA is not a replacement for uterotonics but rather an adjunctive treatment. Uterotonics stimulate uterine contractions to reduce blood loss. In contrast, antifibrinolytics temporarily slow the breakdown of clots and prevent further bleeding. Both drug classes play essential roles in the comprehensive management of PPH.

PRESCRIBING AND ADMINISTRATION

For PPH, TXA is recommended to be administered intravenously. The dosage is 1g/10ml IV at 1ml per minute. A repeat dose may be given if bleeding continues after 30 minutes or resumes within 24 hours of the initial dose. Square

Tranexamic acid

Dosage for PPH

1g/10ml IV at 1ml per minute

Action IV acts in 5-15 mins, effects last 3 hours and dosage can be repeated after 30 mins. There is no benefit of giving TXA after 3 hours from onset of bleeding.

Side effects and contraindications

Nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea are common. Do not use if a woman/ person has:

• A known thromboembolic event

• A history of coagulopathy

• Active intravascular clotting

• A known hypersensitivity to tranexamic acid

practice points for midwives

• TXA is within the midwife’s scope to prescribe and administer, and plays a crucial role in improving maternal outcomes when used effectively and safely. When prescribing a new medication, the College expects the midwife to do the necessary professional development to be competent to prescribe and administer the medication.

• The College recommends midwives add TXA to their homebirth pharmaceutical kit.

• IV TXA is not currently included in the Pharmac practitioner supply order. The College has been advocating for Pharmac to include TXA on the PSO schedule. Currently, 5 vials cost around $20.

• TXA is most effective when administered early after the onset of a PPH. TXA has no benefit after 3 hours. Early administration within 3 hours significantly improves survival rates and reduces the need for hysterectomy. Delays decrease survival by 10% for every 15 minutes.

• Ensure accurate dosage, using the appropriate concentration and administration rate (1g/10ml IV at 1ml per minute).

• Consultation and caution must be considered with contraindications for the medication: Do not administer TXA to women with active thromboembolic disease, a history of coagulopathy, or known hypersensitivity to the drug.

• Ensure TXA administration and subsequent care are culturally safe and respectful. Engage with the woman’s whānau and respect cultural practices and beliefs.

• The principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi should guide interactions and care plans to achieve equitable health; TXA for PPH should be offered in all birth settings, including home.

• For comprehensive guidance on managing PPH, midwives should refer to the MOH Postpartum Haemorrhage (PPH) Consensus Guidelines and poster, alongside any regional guidelines.

CAROLINE

CONROY MERAS CO-LEADER (MIDWIFERY)

SAM JONES MERAS CO-LEADER (INDUSTRIAL)

changes in the workplace… how should this occur?

At some time most midwives have experienced changes in their workplace. These can include:

• Environmental changes such as renovations or changes in the use of rooms

• Relocation of services

• Changes to hours of work or shift patterns

• Changes to role, duties, expectations, service reviews or restructuring of services

• Creation of new roles or disestablishment of roles

• New or revised policies and guidelines

Change managed well in a workplace can be positive, providing opportunities for midwives to contribute ideas and to feel part of any change, which in turn has a positive effect on staff morale. Managed badly, change can have a negative impact on the retention of staff, adversely affect morale and breaking down trust between managers and employees. The MERAS Collective outlines how change should occur in the workplace, capturing key principles which are also included in legislation.

HOW SHOULD CHANGE BE MANAGED?

Changes should occur with some level of consultation with MERAS and the affected workers. The level of consultation may differ depending on the significance and impact of the change, but it must occur. Depending on the nature of the change or provisions of your employment agreement, your consent may be required.

Key principles required in change management processes include:

• Presenting proposals for change of a decision which is not yet finalised.

• Providing relevant information to enable adequate understanding of the proposed change, along with substantive input by affected employees and their Union.

• Ensuring reasonable timeframes that enable the consultation to occur.

• Maintaining open and transparent communication between the parties.

• Giving consideration to the feedback prior to any decision being made.

WHAT HAPPENS IF THIS PROCESS IS NOT FOLLOWED?

If midwives are experiencing change in their workplace or are aware of change that is about to occur, and the requirements outlined above are not evident, they should talk to their local MERAS workplace representatives and MERAS staff. Don’t assume that MERAS has been advised of the change occurring.

If change is occurring and there has not been consultation with midwives and MERAS, then MERAS will raise concerns with managers and highlight the expectations within the Collective and legislation. Any change should not occur until after there has been genuine consultation.

WHAT HAPPENS IF THERE IS A FORMAL CONSULTATION PROCESS?

There are times when midwives and MERAS representatives have been involved in the discussions and development of proposed changes that form the ‘proposal for change’. In other cases the proposal for change is a complete surprise to midwives and MERAS.

When MERAS is advised of a proposal for change, staff talk to local MERAS workplace representatives and affected midwives to gauge their views on the proposal. Feedback is drafted and circulated to members to ensure all their concerns and ideas are reflected. Following the feedback period, midwives, MERAS workplace representatives and MERAS staff may be invited to be part of the review of the feedback and recommendations.

At other times this is just done by managers with midwives and MERAS advised of the outcome.

THE IMPACT OF CHANGE

Sometimes change in a workplace can have a significant impact on an individual midwife or a group of midwives. If this occurs MERAS staff are available to

support midwives through any change nd ensure they are aware of the options available to them. There must be reasonable time for employees to explore these options and for notice to be given prior to any change after consultation has occurred. Do not hesitate to contact MERAS if change is proposed or occurring in your workplace. Square For MERAS Membership merasmembership.co.nz www.meras.co.nz

MERAS/Te Whatu Ora Collective Employment Agreement

Clause 27.1

Management of Change

a. The parties to this Collective Agreement accept that change in the health service is necessary in order to ensure the efficient and effective delivery of health services. They recognise a mutual interest in ensuring that health services are provided efficiently and effectively, and that each has a contribution to make in this regard.

b. Regular consultation between the employer, its midwives, and the union is essential on matters of mutual concern and interest. Effective communication between the parties will allow for:

• improved decision making;

• greater co-operation between employer and midwives; and

• a more harmonious, effective, efficient, safe, and productive workplace.

c. Therefore, the parties commit themselves to the establishment of effective and ongoing communications on all midwife relations matters.

d. The employer accepts that MERAS representatives are a recognised channel of communication between the union and the employer in the workplace.

e. Prior to the commencement of any significant change to staffing, structure or work practices, the employer will identify and give reasonable notice to employees who may be affected and to MERAS to allow them to participate in the consultative process so as to allow substantive input.

f. Reasonable paid time off at T1 shall be allowed for midwife representatives to attend meetings with management and consult with employees to discuss issues concerning management of change and staff surplus.

g. Prior approval of such meetings shall be obtained from the employer and such approval shall not be unreasonably withheld.

Clause 27.2

a. Consultation involves the statement of a proposal not yet finally decided upon, listening to what others have to say, considering their responses and then deciding what will be done. Consultation clearly requires more than mere prior notification.

b. The requirement for consultation should not be treated perfunctorily or as a mere formality. The person(s) to be consulted must be given sufficient opportunity to express their view or to point to difficulties or problems. If changes are proposed and such changes need to be preceded by consultation, the changes must not be made until after the necessary consultation has taken place.

c. Both parties should keep open minds during consultation and be ready to change. Sufficiently precise information must be given to enable the person(s) being consulted to state a view, together with a reasonable opportunity to do so - either orally or in writing.

d. Consultation requires neither agreement nor consensus. The parties accept that consensus is a desirable outcome, however the final decision shall be the responsibility of the employer.

e. From time to time directives will be received from government and other external bodies, or through legislative change. On such occasions, the consultation will be related to the implementation process of these directives. In considering the period of consultation the parties will agree on a period of time for the parties to engage with each other.

f. The process of consultation for the management of change shall be as follows:

1. The initiative being consulted about should be presented by the employer as a 'proposal' or 'proposed intention or plan' which has not yet been finalised.

2. Sufficient information must be provided by the employer to enable the party/parties consulted to develop an informed response.

3. Sufficient time must be allowed for the consulted party/parties to assess the information and make such response, subject to the overall time constraints within which a decision needs to be made.

4. Genuine consideration must be given by the employer to the matters raised in the response.

5. The final decision shall be the responsibility of the employer.

WAYNE ROBERTSON EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, MMPO

reflecting on the integration of the BadgerNet Maternity Suite into New Zealand’s maternity care system

New Zealand’s maternity system has historically faced challenges due to fragmented and disconnected clinical data-recording practices. Recent advancements maintain the drive towards a unified clinical maternity data system, primarily centred around the continued implementation of the BadgerNet maternity suite of products.

The system is expected to be fully adopted by most North Island maternity facilities, in addition to the existing Lead Maternity Carer (LMC) midwife users across Aotearoa. This will mean that more maternity data and information will be seamlessly shared between LMCs providing community care and midwives based in maternity facilities. But how will this benefit māmā, pēpi, whānau and LMCs?

KEY FEATURES AND BENEFITS

• Better clinical decision-making support, leading to more responsive maternity care

• More efficient and effective integration of healthcare services (community and facility)

• Greater māmā and whānau empowerment and engagement

• Greater provision of education and resources

• Better data analytics and reporting, leading to improved insights and innovation

• Continuous improvement to training and support

The current BadgerNet suite offers a unified system through access to contrasting functions and views. These are:

MĀMĀ, PĒPI AND WHĀNAU ACCESS AND VIEW (BADGERNOTES – MULTI LANGUAGE)

This enables secure and private online digital access (through any digital device) to important parts of the woman’s pregnancy record, plus digital access to key resources (including online leaflets) as the pregnancy progresses.

Available pregnancy notes can be securely shared with other health professionals for a limited time. Women control their notes' sharing and can grant up to 1-hour access that can be cancelled anytime, with an audit trail of invitees and access usage.

BadgerNotes integrates with BadgerNet, tracking when leaflets/resources are opened and when the māmā/whānau completes birth plans.

LMC COMMUNITY MIDWIFE ACCESS AND VIEW (AVAILABLE TO THE MIDWIFE NOW)

This gives LMCs the ability to document, review and manage the full pregnancy from the first registration visit, to labour and birth and through until handover to Well Child and general practice.

To ensure safe practice standards, the implementation of included features like

offline mode, partner present mode and robust login support are essential. Offline mode allows continuous documentation even without internet access, ensuring no data loss. Partner present mode controls the visibility of sensitive and confidential data and information during consultations, enhancing support and safety. Secure login mechanisms are crucial for maintaining an accurate audit trail, safeguarding whānau data and ensuring accountability.

Additionally, charts such as MEWS (Modified Early Warning Score), NEWS (National Early Warning Score), GROW (Gestation Related Optimal Weight), Partogram, and biometric charts are accessible and play a vital monitoring and management role.

MATERNITY FACILITY MIDWIFE ACCESS AND VIEW

This gives maternity facility midwives the ability to document, review and manage the pregnancy during the labour and birth stage. The LMC midwife has complete visibility of all data and information updated while the māmā and pēpi are in any maternity facility that uses the BadgerNet maternity system.

NATIONAL DATA VIEW (PERINATAL SPINE) MANAGED BY BADGERNET

The Spine is a national data repository of certain data points and fields (based on the HISO Maternity Care Summary Standard) and sourced from digital records maintained by all LMC midwives (including non-BadgerNet digital vendors) and facility midwives.

Currently, only some booking data, including basic demographic data, are being sent to the Perinatal Spine. No clinical notes or additional context is sent unless the midwife is providing the required information directly in the BadgerNet Raw Care record (through the MMPO and certain facility users).

As data is progressively added to the Spine, māmā and their whānau will no longer need to repeatedly provide detailed medical history, and it will facilitate smoother claims if there is a change in LMC, as the subsequent midwife will not need to start from scratch.

The Spine's implementation is being rolled out in four phases:

• Phase 1 has already been delivered.

• Phase 2 is in testing and includes labour and birth data, newborn baby data and functionality for external parties to

retrieve data, with a release date still to be confirmed.

• Phase 3 will cover postnatal data.

• Phase 4 will include remaining antenatal data and a 'Do Not Share' feature, which is a Health NZ function requiring women to contact Health New Zealand, with the process details yet to be released.

UNIFIED DIGITAL MATERNITY

SYSTEM – BADGERNET DIGITAL

SUITE CLINICAL AND PROFESSIONAL OVERSIGHT

The MMPO Clinical Reference Group (CRG), composed of current midwife users, plays a crucial role in ensuring that the digital maternity system is fit for purpose by focusing on functionality, features, and clinical requirements.

Furthermore, the MMPO regularly engages with the College to seek professional advice and guidance, ensuring that the system aligns with the most up-to-date clinical standards and best practices.

Finally, the MMPO actively participates in broader maternity sector groups such as Health New Zealand's Expert Clinical Advisor (ECA) groups, which include representatives from midwifery, obstetrics and gynaecology, neonatal practitioners, and anaesthetists. These interactions ensure that the needs and perspectives of midwives are well-represented and integrated into the ongoing development and enhancement of the system.

From a wider sector view to ensure the ongoing maintenance of clinical and professional standards, as well as the functionality of the digital maternity system, various sector groups play vital roles. Health New Zealand's ECA groups report to the National Maternity and Neonatal Data and Digital Steering Group (MNDDSG) under Te Whatu Ora.

This steering group is responsible for submitting requests as the system evolves in response to user needs and maintaining high standards of clinical care.

IN SUMMARY

The integration of the BadgerNet Maternity Suite into New Zealand's maternity care system marked a pivotal advancement towards unified clinical data and streamlined care coordination. By integrating maternity data and facilitating seamless sharing between LMC midwives and facility midwives, the

system significantly enhances clinical decision support, efficiency, and patient engagement. Key features such as offline mode, partner present mode, and secure login ensure safe practice standards, while tools like MEWS, NEWS, GROW, Partogram, and biometric charts provide comprehensive maternal and fetal health monitoring. The phased implementation of the national Perinatal Spine further simplifies data sharing and continuity of care.

Through ongoing professional oversight and collaboration across the sector, the BadgerNet Maternity Suite promises to elevate the quality of maternity services, ensuring better outcomes for māmā, pēpi, whānau and the midwifery community. Square

MMPO provides self employed community midwives with a supportive practice management system.

www.mmpo.org.nz

mmpo@mmpo.org.nz

03 377 2485

TAMARA KARU NGĀ MAIA GENERAL MANAGER

Enhancing Support for Māori Midwives: A Tiriti Honouring Approach

TRANSFORMING THE GRADUATE SUPPORT PROGRAMME

The Graduate Support Programme for Qualified Midwives in Aotearoa (New Zealand) is undergoing a major transformation. This redesign is a collaborative effort with the New Zealand College of Midwives (the College) and Ngā Maia Trust. From the beginning, this process has been deeply rooted in honouring Te Tiriti o Waitangi, ensuring the articles and the principles of partnership, protection, participation and equity are top of mind.

As we near the completion of this redesign process, I am hopeful the new and improved version of the Graduate Support Programme will expand its view of the traditional elements such as mentoring, professional development and clinical support, as well as enhance and strengthen the cultural support component. This integration is crucial to creating a culturally responsive environment that meets the needs of all midwives, particularly Māori midwives, tangata whenua (people of the land).

TŪRANGA KAUPAPA AND CULTURAL SAFETY

We are thrilled to share that the Tūranga Kaupapa Education Programme 2024-2028 has received endorsement from the Midwifery Council. The Trust is working diligently to prepare the enrolment pathway for both a face to face and a live online learning schedule. The aim is to make the process smooth and accessible. We feel it best that our primary focus is to first train midwifery educators, midwifery leaders and MSR reviewers, ensuring they are all well-prepared to integrate the anticipated learning outcomes into their respective areas.

CLINICAL COACHING OPPORTUNITY

Ngā Maia is excited to support Te Whatu Ora (formerly Te Aka Whai Ora) in offering a pilot programme to explore the benefits of clinical coaching for Māori midwives. The expectation is that clinical coaching will improve recruitment and retention.

Ngā Maia Trust now offers professional support to practising midwives (Kahu Pōkai) to help them thrive in their work, by their design. Due to the need for both rapid and short-term actions (6 months), we are launching this service immediately with five trusted Clinical Coaches: Lisa Kelly, Crete Cherrington, Jacqueline Martin, Victoria Roper and Tamara Karu. Eligibility for the pilot requires that midwives be beyond their first two years of practice. However, if you have a significant need for clinical coaching or are about to complete MFYP, we would like to hear from you on admin@ngamaiatrust.org.

If you're interested in free clinical coaching, peer mentoring or clinical practice support in a culturally responsive manner, register your interest via your membership portal on our website ngamaiatrust.org/services. Coaching can be delivered face-to-face by arrangement, via phone call or via online hui, depending on availability. Sessions will be strictly confidential. Ngā Maia are required to provide quantitative data and themes; however, these do not include identifiers. Our goal is to offer clinical coaching to 100-130 midwives with up to 8 sessions (1 hour each) per eligible midwife. For urgent matters (within 24 hours), please contact Tamara Karu, phone 0276353566. Square

Heather Muriwai's pōwhiri to the MOH.

Sweet Fruit of Labour

Pasifika Midwives Aotearoa was established well over a decade ago (2012) by the small number of Pacific midwives in the workforce at the time. One of the driving factors for the group’s creation was to halt the alarming attrition rates of Pacific students during their first year of the midwifery degree - hence the ‘Aunties’ mentoring was initiated.

Over the years, whilst we have celebrated the increased numbers of Pacific midwifery students in the programme, the most joyous moments have been watching the colourfully adorned graduates walk across the stage, amidst impromptu cheers from those kin they represent.

The following is the reflection of one of PMWA’s members – fruition of the group’s purpose.

‘Fakaalofa lahi atu ki mutolu oti ko e higoa haku ko Whitney Amadia, mo e ko au ko e fifine Niue Samoa fakahekeheke. Ko au ne hau mai he tau kaina ko Alofi mo Mutalau i Niue mo Safune i Samoa. Ko au ko e māmā mo e fakamālohi ke he fāmili, ko e tokoua au ke he tau fānau he hōhā e 4, ko Emma-Jade, Madison, Leilani mo Ava, mo e tāgata fakamālohi haku ko Jordan.

Greetings to everyone, my name is Whitney Amadia, and I am a proud Niue Samoa woman. I come from the villages of Alofi and Mutalau in Niue and Safune in Samoa. I am a mum to four beautiful daughters, Emma-Jade, Madison, Leilani and Ava, and partner and soon-to be wife of Jordan Slade.

My journey into midwifery began when I had my second baby, Madison Grace, in 2011. For the first time, I experienced what it was like to have the care of a Lead Maternity Carer (LMC), as with my eldest baby I had my local doctor.

In 2019, I took a significant step forward by enrolling into midwifery at Auckland University of Technology (AUT). Although returning to study after over a decade was daunting, I felt a profound sense of certainty that this was the path I was meant to follow. During my first placement, I had the honour of witnessing my first birth. In that transformative moment, immersed in the birthing experience, I knew without a doubt that I was exactly where I belonged.

During my studies at AUT, I had the incredible opportunity to represent my fellow Pasifika students as the Pasifika Student Representative. This role allowed me to be a voice for Pasifika students, advocating for their needs and ensuring our cultural perspectives were recognised and respected within the academic environment. It was a rewarding experience that deepened my commitment to supporting Pasifika communities.

Throughout the degree, there have been numerous challengesbalancing motherhood, placements and assignments, and navigating a pandemic (COVID-19). Despite these hurdles, I would not change a thing, as it was during this time that I met friends who have become family, and networked with many of my future colleagues.

While my goal in pursuing this degree was to become an LMC within the Pasifika community, I realised the importance of understanding the complexities of midwifery care. I wanted to gain the skills to identify when the normal presents with complications. After graduating from AUT, this understanding took me to Te Toka Tumai (Auckland City Hospital), where I completed the New Graduate Programme. It was here that I gained hands-on experience with complex care situations, providing a strong foundation for my midwifery practice and enhancing my ability to provide comprehensive care to māmā and whānau. Te Toka Tumai has been an incredible experience, and I am immensely grateful for the time I spent there. The insights and skills I gained were invaluable, and if I were to return to a facility, I would choose Te Toka Tumai again without hesitation. I have embarked on a new journey as an LMC at the Nga Hau Birthing Centre in Māngere. This role has been a blessing, allowing me to care for Pasifika māmā within the South Auckland community while learning and adapting to this new environment. I am deeply grateful for the support of Tyra Fitisemanu, my midwifery partner and sister, and the exceptional Southside Aiga Midwives. Their support and collaboration have been crucial during this transition. Fulfilling my goal of working within my own community, I feel privileged and honoured to walk alongside these amazing māmā and whānau. I am excited to contribute to the health and well-being of Pasifika and Māori māmā in this vibrant community.

Midwives need midwives to mentor and nurture each other throughout their entire career paths. It strengthens collegiality, provides safe spaces and sustains the profession. When this ethic is applied, it will ultimately translate to quality care for whānau Square

WHITNEY AMADIA (NAMALAU’ULU TISH TAIHIA)

Whitney with her beautiful whānau.

TE WHETŪ ORANGA: AN INTEGRATED HEALTH HUB WITH A MIDWIFERY HEART

Kahu Taurima, the joint Te Aka Whai Ora and Te Whatu Ora approach to the First 2,000 Days, has seen millions of dollars disbursed to various health organisations throughout Aotearoa over the past year. And while a number of Kahu Taurima funding recipients have sought midwifery input at various stages, one in particular has been entirely midwiferyled from the outset. Amellia Kapa shares the story of three Māori midwives in Tokoroa who’ve stopped at nothing to bring their vision to life.

AMELLIA KAPA REGISTERED MIDWIFE

Māori midwife Kimai Cure knows the town –and hāpori (community) – of Tokoroa like the back of her hand. Born and raised in the South Waikato town, Kimai’s Ngāti Raukawa whakapapa not only links her directly to the whenua, but many of the whānau living upon it.

Gaining her midwifery degree in 2014 while living in the Hawke’s Bay, Kimai practised in the region for a couple of years before the call of her papakainga became too loud to ignore, and she returned home to Tokoroa in 2017 to put her new skills to use in her own hāpori.

Upon her return, Kimai crossed paths with Tracey White (Ngāti Toa), another Māori midwife based in Tokoroa, and the following year the pair officially joined forces, forming an LMC partnership. 'One weekend we sat down and came up with a plan for Te Whetū Oranga Midwives,' Kimai explains, the name of which stemmed from a painting she had created for an assignment during her degree. Kimai had created a visual representation of the standards of practice, Tūranga Kaupapa and Te Pae Mahutonga (Mason Durie’s health framework model), and named the image Te Whetū Oranga. It seemed the perfect fit for

Above: Kimai Cure's Te Whetū Oranga.

the pair’s shared vision and model of care.

'When we first started out, we attended all of our births together, and that carried on right up until Covid-19 hit,' Kimai explains.'Then, in 2020, Jackie arrived as a student and by that time Tracey and I were getting burnt out. Covid-19 was rough and especially rurally, things were disconnected and we were having to constantly adapt our practice due to the number of emergencies we experienced over that time.'

The pair knew something needed to change, not just for themselves, but for whānau too. The arrival of Jackie Simpkins (Ngāti Rangiwewehi, Ngāti Koata) as a student was pivotal and her official addition to the practice as a registered midwife in 2021 marked the beginning of a new phase, as her own vision and tikanga aligned perfectly with Kimai and Tracey’s long-held dream.

'We could see the gaps in Tokoroa, between discharge from midwifery care and other health services,' Jackie explains. 'Our whānau were coming back to us well after being discharged from our care, saying they hadn’t been visited by Well Child, or that they didn’t have any contraception. We’d already identified those holes in the system and knew something needed to be done. We had a vision but, at that stage, we weren’t quite sure how we could achieve it.'

The first step, Jackie details, was converting the status of their practice in preparation for what was to come. 'The year I started with Te Whetū Oranga Midwives, we decided to convert our business into a company. We were already steering that way because we knew we’d need to expand if we were to offer more support to whānau. And even though we didn’t know the specifics of how we’d achieve it, we just knew we needed to start. So we created a company – that was the first step. The following year, after six months, we went from Te Whetū Oranga Midwives to Te Whetū Oranga Health.'

On a day-to-day level, everything remained the same and the three midwives continued to toil away, caring for their caseload but knowing all the while, the right opportunity would present itself. And sure enough, when they least expected it, they stumbled across a funding opportunity.

'We were doing things like driving rural whānau to Tokoroa for appointments, or putting petrol in their cars,' Jackie recalls. 'We knew that gap needed to be filled so badly. Then we found Kahu Taurima and it was exactly what we’d been looking for; a way

of wrapping all of these extra services and resources around the whānau we were caring for, but maternity based. So we went for it.'

Pulling the initial proposal together was a collective effort, Jackie and Kimai say, laughing as they reflect on their antics.

'My cousin is the ED nurse manager at Tokoroa, so I asked her to come and help us,' Kimai says. 'She came and sat with us until midnight – until we’d finished it and sent it in. A month later, we were offered an interview and got through to the next stage, which was a presentation.'

It was a lengthy process. Kimai explains the trio still needed to meet their primary responsibilities as caseloading midwives, while dedicating every other spare minute to ensuring they presented a worthy case. 'All throughout the process we were still working as midwives, so in some instances we’d been up all night birthing, hadn’t had any sleep, and had to front up for meetings so that we could get it over the line. We were running on empty. Then on the 2nd of June, we found out we’d got the funding.'

The next challenge, the pair explain, was asking people – mostly whānau – to work for free while they waited for the funds to be disbursed. 'We had to make a start before we’d actually received the funds,' Jackie explains. 'So we found people to work for us for free and we funded the rest of it ourselves for the first few months. But they were our whānau, and that’s the Māori model, so they did it willingly,' she adds proudly.

'We got up and running in November 2023,' Jackie recalls. 'We had to move to new premises because our old space was too small, and we’ve already outgrown it. We have a Well Child nurse, a social worker, we contract a counsellor and we now have a general manager as well as an administrator who also does our PR. Our GM and administrator both worked for free in those early months, and their skillsets are amazing. We didn’t know how to set up job descriptions, for example, but they took those things off our plate.'

The organisation has gone from strength to strength, as Jackie illustrates. 'This year we got cold-chain accredited for immunisations and now we have an immunisations contract, supported by South Waikato Pacific Islands Community Services (SWPICS). We’ve also employed a Clinical Nurse Lead, who still works as an ED nurse manager. We realised we didn’t understand nursing and knew that aspect

One of our greatest success stories is our Well Child programme. When our nurse goes to her training sessions, the other nurses are in awe; she’s almost ready to close her books and that’s because it’s so seamlessly integrated.

of the service was going to grow, so we needed to bring someone on board with that expertise.'

And that’s not all. The list of services available to whānau is extensive, just as the midwives had always envisaged. 'We have hapū wānanga, Wai Ū breastfeeding support that includes a Pasifika lactation consultant, and Pēpi and You, which is a fourth trimester programme. We also serve as a drop-in centre; we have breast pumps for hire and we always have free stuff at the front for whānau to take. The other thing is transport; we can organise transport for women who can’t get to scans or appointments. So that bridges another gap.'

A bustling hub, Te Whetū Oranga Health has been well received by the community and engagement is at an all-time high, Jackie demonstrates. 'One of our greatest success stories is our Well Child programme. When our nurse goes to her training sessions, the other nurses are in awe; she’s almost ready to close her books and that’s because it’s so seamlessly integrated. The women come in for their antenatal appointments with us, then the Well Child nurse pops in to meet them. So that whakawhānaungatanga starts in pregnancy, before that pēpē is even born.'

Jackie Simpkins, Tracey White and Kimai Cure.

The convenience of having multiple needs addressed in the same appointment removes yet more barriers for whānau. 'It’s become a one-stop shop,' Jackie explains. 'If a woman says they haven’t had something like the pertussis vaccination, I pop out and find a nurse who can talk to them about it while we’ve got them there and we get it booked in.'

Having a strong midwifery core is what makes Te Whetū Oranga Health so unique, Kimai explains. 'I think that’s our point of difference; this all started with midwives. Being so intimately involved with whānau and holistic in our view means we’ve always been able to see what’s been missing. Our own midwifery work is still funded by Section 94, just like any other midwifery practice. But the Kahu Taurima funding covers everything else that surrounds the core of midwifery care. And it’s important to make that distinction; the midwifery team is at the centre, and everything else wraps around it, not the other way around,' she emphasises. Being so well integrated in their community is another reason why whānau are consistently engaging with services, Kimai explains. 'We’ve

been established here in this community for 13 years. There’s a real sense of partnership and trust, so when we embarked on this journey, our hāpori followed.'

Another success story could have ended very differently but Kimai and Jackie point to the power of an integrated approach.

'A young 17-year-old client of ours came to us in a psychotic state, which was druginduced,' Kimai begins, 'and we needed to care for her antenatally. We were so out of our depth but, in addition to the other referrals, we got our social worker and counsellor on board to support her. The social worker went and worked with her whānau, discussing why she needed to be on medication, sharing more information so that they understood the rationale and what support she needed to keep her and baby safe. And then together we all made a collaborative plan for her postnatal care. That young woman came out of the psychosis and is no longer on drugs. I was so terrified she might take her life during that pregnancy but, with an integrated approach and by involving the whānau in her care, a tragedy was avoided.'

Come join us!

Are you a skilled midwife looking to make a meaningful impact in the lives of whānau?