Pilotage Zone 12 Bahia ahoy! Meet Brazilian Maritime Pilots' Association Magazine 63th edition - October/2022 - January/2023

And we are now in the ninth article of the Rumos Práticos series regarding the Brazilian pilotage zones. This time, our team arrived in Bahia where 33 pilots are responsible for ship handling in the Bay of All Saints and Ilhéus. The apparently calm waters of the state also hide challenges for safe guiding of vessels, as the reader will see.

Further on, we take stock of the return of the National Pilotage Meeting, whose 44th edition was held in Gramado (Rio Grande do Sul-RS). The discussions were not only among pilots, managers and consultants of the pilot stations, but also involved teachers, researchers, representatives of local maritime and harbor authorities and partner firms.

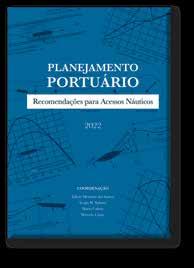

We also look back on the first year of the Brazilian Pilots Institute operations in Brasilia. Our premises were the venue for a launch of important books for the sector, as well as offering the first training course with pilots and operators on its maneuver simulator. One of the books was Planejamento Portuário – Recomendações para Acessos Náuticos [Port Planning – recommendations for nautical accesses], a key input by various authors to safely optimize designs.

Next, we reproduced another major article by the retired Rotterdam pilot, Henk Hensen. He has written a number of books, and makes recommendations for tug approach in strong winds, one of them on training by means of a bridge simulator.

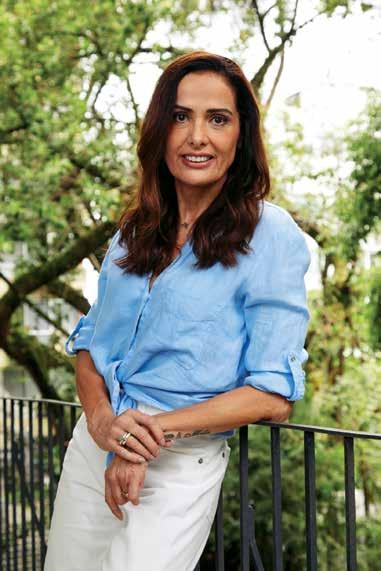

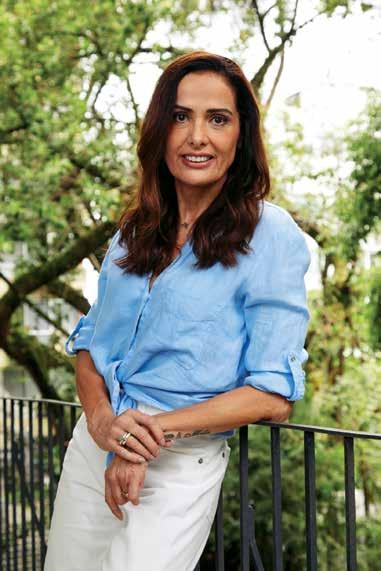

The edition’s last article addresses the social projects managed by Adriana Samuel, Olympic volley medalist, who combines this work with managing athletes’ careers, such as canoeist Isaquias Queiroz, sponsored by Brazilian Pilots.

Enjoy your reading!

editorial

Otavio Fragoso is the editor

Brazilian Maritime Pilots’ Association

Av. Rio Branco, 89/1502 – Centro – Rio de Janeiro – RJ – CEP 20040-004

Tel.: 55 (21) 2516-4479

conapra@conapra.org.br praticagemdobrasil.org.br

director president of Brazilian Maritime Pilots' Association and vice-president of IMPA

Ricardo Augusto Leite Falcão

director vice-president

Bruno Fonseca de Oliveira

directors

Marcello Rodrigues Camarinha

Marcio Pessoa Fausto de Souza

Marcos Francisco Ferreira Martinelli

Rumos Práticos

planning

Otavio Fragoso/Flávia Pires/Katia Piranda

editor

Otavio Fragoso

writer

Rodrigo March (journalist in charge)

MTb/RJ 23.386

translation

Elvyn Marshall

revision

Julia Grillo

layout and design

Katia Piranda

pre-print

DVZ Impressões Gráficas

cover

photo: Gustavo Stephan

The information and opinions expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily express the Brazilian Maritime Pilots' Association viewpoint.

6 16 22 25 27 33

Fair winds in Bahia

Pilots meet again at the profession’s annual event

Institute in Brasilia receives first visits and training with pilots and operators

Book combines best international practices in port planning

Tugs and wind drift

6 16 22

Learn about the free projects of Olympic medalist Adriana Samuel

index

Fair winds in Bahia

BAHIA Bahia Regasification Terminal Madre de Deus Terminal

Port of Ilhéus

Enseada Indústria Naval S.A.

Roque Terminal

Port of Salvador

São

pilotage in Brazil 6

Port Terminal of Cotegipe

Aratu Naval Base

Intermarítima Terminal

Former Ford Terminal

Port of Aratu

Port Terminal of Cotegipe

Aratu Naval Base

Intermarítima Terminal

Former Ford Terminal

Port of Aratu

Dow Química Terminal in Brazil 7

pilotage

Bahia state offers good climate conditions and natural facilities for navigation, but also challenges pilots in ship handling with its strong currents

Readers, smile, you’re in Bahia – a Brazilian state with natural charms, favorable environmental conditions and a deep-water bay. Nevertheless, it still offers challenges for the 33 pilots working in the Bay of All Saints [Bahia de Todos os Santos] and in Ilhéus. In December Rumos Práticos visited Pilotage Zone 12 for the ninth article of the Brazilian ZP series.

The Bay of All Saints measures 30 and 15 nautical miles North-South and East-West, respectively. It is one of the largest bays in the world and provides more than 30 mooring sites for a diversity of cargoes and passengers, in addition to anchored ship-to-ship operations. The narrow mouth of the bar increases water velocity. Every six hours the tide fills the bay up to three meters in height, then flows back into the ocean, helping toward internal cleaning.

“The water here is crystalline, and this really provides an environmental edge. We have very strict risk prevention regulations at every level. The whole bay is an Environmental Protection Area (APA)”, recalls pilot Flavio Durce, from Ilhéus Pilots.

pilotage in Brazil 8

PILOT FLÁVIO DURCE ON HIS WAY TO ANOTHER MANEUVER

photo: Gustavo Stephan

On the other hand, the tidal range creates quite a strong current, especially in the Cotegipe Canal and at the Madre de Deus Terminal.

“This is one of our major challenges. Almost all maneuver slots depend on the tide”, says pilot Alexandre Takimoto, from Madre de Deus Pilots.

The terminals in the Bay of All Saints are distributed at different points. The port of Salvador is located on the right side of Maré Island, providing 13 berths. It is operated by the Bahia State Dock Company (Codeba), handles general freight and receives passengers. It also includes the container terminal, to a depth of 16 meters. The port is certified for container carriers 366 meters in length.

Going northwards, the ore terminal is next, operated by Intermarítima (acquired from Gerdau). The port of Aratu was built farther into the Bay in 1975, in the Candeias municipality, ten kilometers from Salvador, since the latter was unable to operate special cargoes. Aratu, also under Codeba management, has six terminals for handling dry bulk, liquid and gas products.

Before reaching the port, on the right is the entrance to Cotegipe Canal, a narrow access with two sharp bends, which makes maneuvers tricky for larger ships. Right at its entrance is the Brazilian Navy’s Aratu Naval Base, with space for three vessels. On the same bank are two berths in the Cotegipe Port Terminal, for wheat imports and soy exports from western Bahia. On the other bank are located the deactivated Ford terminal, where roll on/roll off (Ro-Ro) car shipping vessels were once moored, and the site of Dow Chemical Company terminal.

To the left of Maré Island lies the Madre de Deus Terminal, south of Madre de Deus island, using five piers depending on the ships’ size. This is where petroleum arrives for Mataripe Refinery, which supplies the entire State of Bahia. The refinery was sold by Petrobras to an Arab fund to operate the asset, but for the time being Transpetro, the national oil company’s subsidiary, continues to provide the services.

The distance between Salvador and Madre de Deus is 16 nautical miles. Rumos Práticos accompanied an arrival maneuver with pilot Luiz Carlos Rosas, from Salvador Pilots, who has been a pilot for 46 years:

“The deepest part of the Bay is when we arrive at Madre de Deus, because the current, when it enters at the high tide and flows back at low tide, will deepen the channel, which is narrow at this stretch. It’s a strong current. The pilot needs to take care when guiding the ship and observe to which side the ship swings with the tide. And this also influences the vessel in the turning basin in front of the pier.”

9 pilotage in Brazil

PILOT LUIZ CARLOS ROSAS ON THE JOB TO MADRE DE DEUS

photo: Gustavo Stephan

Pilot Camilo Santos, from Ilhéus Pilots, once had to abort sailing up to Madre de Deus and return to the anchorage, after a ship had engine failure and missed the favorable tide:

“It occurred just before the terminal and there was the problem of an existing gas pipeline. There we cannot simply drop anchor. This time, the ship wasn’t moving fast. I reckoned we could pass the gas pipeline at a slower speed. I didn’t actually drop anchor because the engine started up again. But we missed the mooring window, which should be done with the weaker incoming tide.“

In addition to the sale of Madre de Deus, Petrobras leased the Bahia regasification terminal (TRBA) to Excelerate Energy. Situated west of Frade Island, the ocean terminal receives 300m-long ships anchored in ship-to-ship operations to transfer liquified natural gas for regasification. The product is then distributed through another pipeline across the bay, connected to TRBA.

Ship-to-ship operations are also carried out with vessels anchored to the north of Itaparica Island. The reason for this is a 12.5-meter draft restriction in the access canal to Madre de Deus, so a smaller ship can moor alongside a larger ship to receive petroleum and move to the terminal. Today, maneuvers are limited to Suezmax oil tankers, with a 16-meter draft, but approval will be expected shortly for very large crude carriers (VLCC) with up to 23-meter draft. The area can accommodate three simultaneous operations: two for VLCCs and one for Suezmax.

This region is also certified for ore transfers in the same system. According to the original design, the contrary would occur. A smaller ship, coming from Enseada Indústria Naval, would carry the product for loading on a “Capesize” vessel, the largest class of bulk ship. Enseada is located on the River Paraguaçu, which flows into the Bay northwest of Itaparica Island, and is used for unloading wind-blades and receiving ore from southwest Bahia for export. However, there is a restricted draft due to a high-seabed and a gas pipeline passing 11 meters in depth at the river mouth. São Roque Terminal is also located within Paraguaçu, at the mouth of the River Baetantã, and operates as a Petrobras shipyard.

In the southern region of Bahia is the Port of Ilhéus, which had its operating draft reset to 9.8 meters after dredging. In addition to handling commodities such as soy, nickel, cacao, timber and design load, it also welcomes cruise ships. In the 2022-2023 season, around 110 such moorings were planned, including Salvador, where Rumos Práticos joined the arrival of one of those vessels with pilot Paulo Torres, from Ilhéus Pilots, 35 years working in the profession.

pilotage in Brazil 10

PILOT CAMILO SANTOS STEERING VESSEL TO ANCHORAGE

Bahia Pilots is based in the Bahia Marina, site of its operations center upgraded in 2019, and where the boats leave for boarding the pilots at the pickup point near Farol da Barra (Barra Lighthouse). The fleet was renewed and now has nine pilot boats and two port boats, manned by a team of 27 seamen. The port boats are catamarans, chosen for their good seagoing performance since the winds in the Bay of All Saints can cause up to five feet (1.5 meter) high waves. Because they are smaller, they require only one crew member and reach 30 knots in speed, compared to the pilot boat’s 23 knots.

More technology was added to the operations center, generating further data for decision-making and risk management. Cameras focus on Salvador (entrance to the bay and port); Cotegipe and Aratu canals; Madre de Deus; the ship-to-ship area and the TRBA (the latter located on Itaparica Island); and Ilhéus.

Salvador, Aratu, Madre de Deus and Ilhéus have weather stations. And meteo-oceanographic buoys are distributed along the main points of the bay; one at its entrance (measuring currents and waves); another close to the Yacht Club (waves and wind); at the Madre de Deus canal (currents); and the channel to TRBA (currents); in addition to a radar tide gauge and anemometer at the last two terminals.

The ReDraft dynamic draft system, which calculates how much a ship can increase its under keel clearance without risk of running aground, is in its final stage of approval. Virtual beaconing is another used technological tool. At the container terminal access, the virtual buoys provide further benefit of the depth of the channel to 14.8 meters, without need for dredging. The technology is ready to demarcate ships’ access with a draft of over 20 meters, towards the ship-to-ship area, as soon as they are authorized by the Brazilian Navy. Likewise, it can indicate shipping accidents and substitute damaged physical buoys.

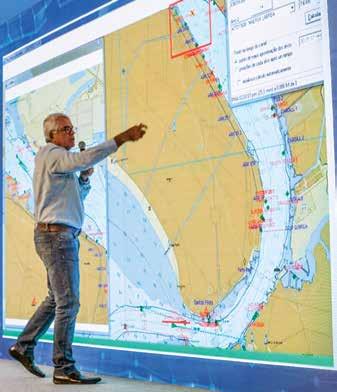

“Although we are not a vessel traffic service (VTS) or vessel traffic management information system (VTMIS), nor do we need it, we have come very close to being a local port service (LPS). We can accompany all vessels entering the bay, helping the Maritime Authority on maritime situational awareness”, states Victor Hugo Villafán, pilotage manager with Ricardo Blanquet.

The ZP-12 station also provides pilots with the portable pilot unit (PPU) that supplements onboard data. The pilots normally use it during maneuvers at TRBA, Enseada and the container terminal. Felipe Perrotta, from Bahia Pilots, prefers to use it whatever the task:

pilotage in Brazil 11

PILOT PAULO TORRES DURING A CRUISE SHIP MANEUVER

photos: Gustavo Stephan

“At the final mooring or when unmooring, we are outside (on the ship’s wing) with no access to bridge instruments, depending only on our sight to assess the ship’s speed and bow. Either the pilot is very confident of his sight, or has plenty of time to ask the captain what the speed is, etc. With the PPU, all this information is hand-held. Moreover, I am able to see the ship’s way forward, its distance from the terminal, bathymetric data not yet updated in the official chart, and the movement of vessels way before I communicate with them. It’s a tool that gives precision that I wouldn’t have if I only used my sight.”

Bahia Pilots undertakes around 4,500 maneuvers a year and has been contributing with all these investments and with its experience for the development of the state ports. In December, Codeba was awarded the Lidera Infra Prize from the Ministry of Infrastructure, for being one of the best performing publicowned companies between 2019 and 2022. In 2021, the company achieved an unprecedented result, with more than 13 million tons of shipments. The first quarter of 2022 was the second best ever.

12 pilotage in Brazil

MANAGER VICTOR HUGO AT THE CENTER OF OPERATIONS

photo: Gustavo Stephan

pilotage in Brazil 13

ARRIVAL AT MADRE DE DEUS TERMINAL

photo: Rodrigo March

PILOT FELIPE PERROTTA USING A PORTABLE PILOT UNIT (PPU)

photo: Gustavo Stephan

14

pilotage in Brazil

OUTGOING MANEUVER FROM PORT OF ARATU

pilotage in Brazil 15

photo: Gustavo Stephan

Pilots meet again at the profession’s annual event

The 44th edition of the National Pilots’ Meeting in Gramado (Rio Grande do Sul-RS) was attended by academics, maritime and port authorities and corporate partners

After the two-year suspension due to the pandemic, the National Pilots’ Meeting was resumed in Gramado (RS), in its 44th edition. From November 30 to December 2, pilots from all over Brazil, in addition to pilotage managers and advisors, met in the city to exchange experiences and discuss mutual challenges. Teachers, researchers, representatives of the Maritime Authority, the local port authority and corporate partners also participated in the discussions. The event was held at the convention center of the Wish Serrano hotel.

Pilot Ricardo Falcão, president of Brazilian Pilots, opened the meeting on the day of talks, highlighting the role of the profession during the pandemic:

“Cargo handling in our ports increased as much in 2020 as in 2021. We demonstrated all our resilience. And here it is worth mentioning the Brazilian Navy, responsible for regulating our profession. Thanks to our model, we are ready to meet any peak period demand. We underwent this difficult period smoothly and accident-free, which is the most important thing.”

16 national meetings

photo: Gustavo Stephan

RICARDO FALCÃO, PRESIDENT OF BRAZILIAN PILOTS, AND VICE-ADMIRAL JOSÉ LUIZ RIBEIRO FILHO

Falcão also mentioned the investments made by the profession during the period, namely the Brazilian Pilots Institute and its training and maneuvering simulations center in the capital Brasilia:

“In each pilotage zone, we’re partners in the development of the country and in this spirit, we inaugurated our center in Brasilia. With the center being located close to the authorities responsible for decision-making on the projects, we expect to be more agile in assessing access channels, implementing terminals and approving new ship classes.

Vice-Admiral José Luiz Ribeiro Filho, superintendent of Safety of the Waterway Traffic of the Directorate of Ports and Coasts (DPC), also praised the adaptation of the pilots during the pandemic to keep the service constantly available, as well as the importance of investing in simulators to increase the professional proficiency and optimization of port studies.

Representing Vice-Admiral Sergio Renato Berna Salgueirinho, director of Ports and Coasts, the superintendent argued in favor of the single service roster scale for attending shipowners:

“The roster scale is the guarantee for providing an uninterrupted service, preventing fatigue and maintaining the pilot’s qualification on any kind of ship. We understand that the competition (between pilots) does not contribute to navigation safety, and the extinction or flexibilization of the scale is not realistic.”

The Vice-Admiral mentioned the effort by DPC to ensure that the pilot’s boarding and disembarking devices on the ships comply with the regulation:

“The naval inspectors of the Ports and Coasts Directorate have been intensifying the inspection of the ladder conditions. The coordinators of my Inspection & Survey Management have

national meetings 17

PILOTS GATHERED AT THE EXTRAORDINARY GENERAL MEETING

photo: Gustavo Stephan

been instructed to focus, during the port state and flag state inspections, on checking the upkeep of the devices. All of them should be safer by the middle of this year.”

After introducing the Maritime Authority representative, the panels began with the presentation of the Brazilian Pilots Institute. It included pilot Bruno Fonseca, vice-president of Brazilian Pilots and vice-president of the Institute's board of directors; Jacqueline Wendpap, the Institute’s executive director; and technical manager Jeferson Carvalho.

Bruno Fonseca told how the idea of a simulator in Brasilia came to mind, presented at the 43rd National Pilotage Meeting in Maceió, in 2019. The Institute completed one year on December 14th

“We have accompanied the significant increase in the size of ships and demand for cargo handling. But the port infrastructure is not growing at the same speed. So, there is an urgent need for feasibility studies for new operations, new berths and terminals. And so this is where the simulator comes in as an excellent tool. Through it, we test the limits of the meteorological conditions, types of loading and the different kinds of ships that will fit the intended maneuvers. We also have IMO Resolution A.960, which states that pilot training can be supplemented by using the simulator, which is an excellent tool for the Pilots’ Refresher Course. Our simulation center emerged from the new operational feasibility and the APTR pilot’s refresher course.

In the next panel, pilot Hermes Bastos Filho, Director-Superintendent of São Paulo Pilotage, explained how the maneuvers were optimized in the Port of Santos, reducing idle terminals and generating productivity gains. For the past two years there have been simultaneous maneuvers and two-way traffic in once narrow stretches, in total safety. To increase the efficiency of the channel’s use, the pilotage analyzed the timing of each special ship’s maneuver or each maneuver in between, tabulating these times.

“The crossing of a large ship takes six minutes, in two hours of navigation, to occur at a safe point. It isn’t so easy. We check available space and time for the maneuvers. We changed the paradigm in our operations and in programming special and “heavy” vessels, always respecting the standards and restrictions. Our vision was the Port’s development.”

Closing the morning cycle, Edson Mesquita, head professor of the Navy’s Higher Education center (Ciaga), addressed the history of the ship’s maneuvering theory, from the ship’s mathematical foundation of Isaac Newton until today, a subject on which he writes in the books A manobrabilidade do navio no século 21 [Ship maneuverability in the 21st century] and Princípios de hidrodinâmica e a ação das ondas – sobre o movimento do navio [Principles of hydrodynamics and wave-induced ship motion].

18

national meetings

photos: Gustavo Stephan

TALK BY BRUNO FONSECA, VICE-PRESIDENT OF BRAZILIAN PILOTS

PRESENTATION BY HERMES BASTOS FILHO, DIRECTOR OF SÃO PAULO PILOTAGE

In the afternoon, Navy and Merchant Marine captain Guillermo Gómez Garay, senior project manager of Force Technology, brought a new view on maritime safety and the pilot’s role, based on studies undertaken in Sweden, Denmark and Canada; the training of over 450 pilots in Europe and the US; and his learning from accident investigations. Some of the issues in his presentation were the cultural and social aspects in the relationship between the pilot and ship’s captain, which may lead to accidents if not recognized and well managed on the bridge.

The Bahia Pilotage’s ESG pilot-project (Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance) was the topic of the talk by Elemental Pact CEO, Fabio Gomes de Azevedo. He foresaw the points to be addressed in the pilotage zone: weather risk prediction, environmental and socio-economic strategic mapping and social investment.

Next, Rio de Janeiro pilot Matusalém Gonçalves Pimenta, partner of the law firm Matusalém Pimenta Advogados, talked further about the legal principles governing the pilotage service: minimum claim ratio, functional independence, recent experience, limitation of the pilot’s civil liability in event of accidents and reasonability of this limitation. And gave examples of accidents in which these principles were not respected, as in the case of Exxon Valdez, whose captain had no recent experience to navigate in an area of optional pilotage.

Equipment that provides more maneuvering safety, the Brazilian portable pilot unit (PPU) and its development were the focus of the talk by Rodrigo Barrera, managing partner of Navigandi. The electronic portable pilot unit helps the pilot aboard in making decisions and was developed in partnership with the pilotages, considering the difficulty in the upkeep of foreign equipment abroad. It took four years of development after interviewing 26 pilots in 17 pilotage zones, in addition to onboard metering campaigns. Today, the national PPU is used by the Pernambuco, Espírito Santo, São Paulo, Paranaguá (Paraná) and Itajaí (Santa Catarina) pilot stations. The next pilot stations to use them will be Pará and Rio de Janeiro. Cloud data storage of the maneuvers could help studies on draft increase and training.

19 national meetings

MARCELLO CAMARINHA, DIRECTOR OF BRAZILIAN PILOTS, AND PROFESSOR EDSON MESQUITA

GUILLERMO GÓMEZ GARAY BROUGHT NEW INSIGHT INTO SAFETY

FABIO GOMES DE AZEVEDO INTRODUCED THE ESG PROJECT

photos: Gustavo Stephan

20

national meetings

photos: Gustavo Stephan

LEGAL ADDRESS BY RIO DE JANEIRO PILOT MATUSALÉM GONÇALVES PIMENTA

MARCIO FAUSTO, DIRECTOR OF BRAZILIAN PILOTS, AND RODRIGO BARRERA OF NAVIGANDI

The last panel was by Fernando Estima, manager of RS Ports Planning and Management, who spoke about the role of the state company responsible for the entire port system in Rio Grande do Sul. He emphasized the partnership with the local pilot stations in the state’s progress:

“We won’t give up on having an integrated management with the other stakeholders. This is why we came to the Meeting and want to join the Institute (Brazilian Pilots). We are at your disposal to help pilotage find more cargo and generate progress and jobs for our state.”

Fabio Branco, Mayor of Rio Grande, and Rosa Volk, Secretary for Gramado Tourism, also attended the 44th National Pilotage Meeting. On the day before the plenary a meeting of pilotage managers and advisors was held. And on the last day, the pilots gathered in an assembly.

The event was sponsored by the companies All System, DMGA Consulting, Hidromares, Navigandi, Supmar, Volvo Penta and Wilson Sons.

Check out all the photos on https://www.flickr.com/photos/ praticagemdobrasil/albums

21 national meetings

MEETING OF PILOTAGE MANAGERS AND ADVISORS

MARCELO CAJATY, VICE-PRESIDENT OF FENAPRÁTICOS, THANKING FERNANDO ESTIMA, RIO GRANDE DO SUL PORTS

photos: Gustavo Stephan

Institute in Brasilia receives first visits and training with pilots and operators

Check out the Brazilian Pilots plans for its center in the capital, including the ATPR course

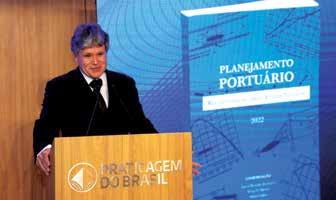

The Brazilian Pilots Institute and its maneuver simulations center celebrated their first year on December 14 in Brasilia. In 2022, the center welcomed its first visitors and was the venue for the launch of important books, as well having held training courses for pilots and operators of pilot stations. Also, preparation was made to accredit its full mission simulator with the Maritime Authorities in order to receive the Pilots’ Refresher Course (ATPR).

The next step is the signing of agreements to evaluate access canals in Brazil and abroad. Directors of the Companhia Docas do Ceará were among the visitors with this intention. Throughout the year, the Institute received many visitors, among whom were representatives from other public and private ports, from the Brazilian Navy, the Ministry of Infrastructure, the National Agency of Waterway Transports (Antaq), as well as researchers, journalists and students.

22 simulador

photo: Tico Fonseca

FULL HOUSE FOR LAUNCH OF PLANEJAMENTO PORTUÁRIO: RECOMENDAÇÕES PARA ACESSOS NÁUTICOS [PORT PLANNING: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR NAUTICAL ACCESSES]

The plans also include partnerships for pilots abroad to come train with Brazilian colleagues, as has already occurred in ATPR.

The pilots in Pilotage Zone 03 (Pará) were the first to use the simulator for training in October. They work in Marajó Bay, where they have ships with the greatest deadweight and draft, and in Guajará Bay, which despite its historic importance for the state, has depth restrictions. And it is precisely there that a new terminal expects to operate with an increase in the maximum authorized draft. At first, feasibility studies were performed by the pilots and the future port operator in the University of São Paulo (USP), which installed the Brazilian Pilots simulator in Brasilia.

“The simulation in the Institute meets our environment requirement for the new demarcated canal, through which we’ll sail in the future, as well as for the tighter turning in an area with strong natural forces (tidal currents, wind and waves). The terminal is under construction and depends on the approval of the relevant authorities, but the pilotage went ahead, and we divided our crew to adapt to the new conditions,” explains local pilot Marcos Martinelli, Brazilian Pilots director.

He stresses the relevance of the pilots’ experience and their seagoing view to calibrate the simulator and bring the hydrodynamic parameters closer to reality:

“This symbiosis between simulation and pilotage brings advantages for the service’s end-user community, which benefits from more professionalism, onboard technology and safety, considering the risk level of a maritime enterprise of this magnitude.”

In December, it was the turn of 12 watchtower operators from different pilotage zones to take part in a three-day training course in Brasilia, on waterway traffic control. They had content classes such as port planning and infrastructure, pilotage service, language and communication, nautical knowhow, traffic and emergency situation management. The purpose was to provide basic know-how to control a pilot station and explain the importance of human resources for the service’s efficiency.

According to pilot Bruno Fonseca, vice-president both of Brazilian Pilots and of the Institute’s Board of Directors, the internal processes are being finalized to accredit the Institute with the

simulador 23 Além

ATPR atualizado e planeja retorno do curso para operadores em Brasília

de projetos visando à segurança do prático, Diretoria Técnica retoma

THE INSTITUTE’S FIRST COURSE FOR OPERATORS

photo: Pedro Ladeira

Maritime Authorities and offer the ATPR course, making Brasilia an option for the Brazilian Navy’s teaching units in Rio de Janeiro (RJ) and Belém (Pará-PA). During the 44th National Pilotage Meeting, Bruno Fonseca recalled that, starting in 2023 the National Pilots’ Federation will also occupy premises in the building, so that the address in the capital will become a center for Brazilian Pilots:

“A lot of work has been done in one year. We envisioned our Institute to be accredited and ready to house the ATPR, our pilots training more and more on the simulator, which is our home, and hosting our foreign colleagues.”

At the 44th ENP, Jacqueline Wendpap, CEO of the Institute, said that another target is to make this space a center for discussion of matters involving port construction and shipping in Brazil:

“In these terms, the Institute will act as a catalyst forum for all the debates in the segment, and always with the innovative footprint and ESG (Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance) approach.

In addition to the full mission simulator, the area has control rooms for simulations, for briefing and debriefing of maneuvers, electronic navigation training and classrooms, plus rooms planned for future facilities of another full mission simulator and a harbor tug simulator.

Jeferson Carvalho, technical manager of the Institute, affirms that in the future it will be possible, for example, to simulate a ship with a tug in the same scenario, and use the second full mission simulator as another tug, bringing more reality to the simulations. Currently, the installed simulator provides 20 models of vessels and 25 scenarios for composing various cases. However, new data could be developed in partnership with USP.

“We have a state-of-the-art simulation tool able to prepare any exercise”, pointed out Jeferson Carvalho during the 44th ENP.

He stated that a big data room is also planned:

“Our idea is to find data on vessel movement and produce scientific articles on, for example, collision probabilities. We can model this mathematically, simulate a percentage increase in ship handling and understand how the scenario will behave.

Further information and technical visit appointments at: secretaria@institutopraticagem.org.br

24

VISIT BY JOÃO AZEVÊDO, STATE GOVERNOR OF PARAIBA, IN DECEMBER

photo: Andressa Anholete

simulador

Book combines best international practices in port planning

Check out the launch of the publication in Brasilia. Download the contents for free

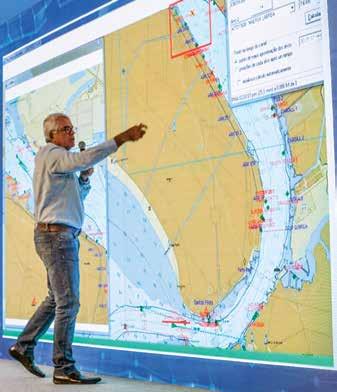

The seafaring community met in October in Brasilia to honor the launch of the book Port Planning – recommendations for nautical accesses. The event was held in the Pilotage Institute of Brazil, in the presence of representatives of dock companies, private terminals, shipping firms, government, producers, the sector’s bodies, academics, and other authorities. Everyone stressed the importance of the book for the country’s productivity and competitiveness.

The book is a contribution by 25 authors providing recommendations for drafting port designs or alterations to existing facilities. The coordination is by professors Edson Mesquita dos Santos and Sergio H. Sphaier, naval consultant Mario Calixto and Marcelo Cajaty, vice-president of the National Pilots’ Federation. Brazilian Pilotage was responsible for the edition.

The publication meets the need for a national technical standard on the topic, bringing safety and efficiency to new designs and current facilities. Some of the authors are designers, researchers, engineers, watermen, shipowners, port workers, pilots and terminal representatives. They used as basic references documents of the International Nautical Association (Pianc), the handbook of the US Army Corps of Engineers’ and recommendations from Spanish maritime projects.

Ricardo Falcão, president of Brazilian Pilots, recalls how he began port standardization. In 1965 the International Maritime Organization (IMO) perceived the need for harmonization in the world, and thus began the Convention on Facilitation of Maritime Traffic (FAL 65). The initial aim was to reduce bureaucracy and facilitate port traffic. After this Convention came FAL.6/Circ.14, a list of relevant publications with everything about the port/ship interface. This discussion developed into the first Pianc publication (World Association for Waterborne Transport Infrastructure) to address the matter (PTC/1997), reviewed and extended with the launch of the body’s 121/2014 report, one of the references for the book.

“From now on we will speak the same language because it’s a technical bible adopting world standards. The idea is to disseminate and level the knowhow for discussion, so that everyone can understand why certain decisions are taken or why an investment should or not be made. They are serious decisions that very often involve public money”, recalled Falcão, adding that the venue for the launch could not be more appropriate. “The book is part of history, since the projects in the area need to be assessed on a simulator, according to the good practices of the publication. And, to do so, we have in our institute the most advanced simulation center.”

Port planning – recommendations for nautical accesses is the result of the Commission to draft the second edition of the ABNT standard on port planning (ABNT NBR 13246:2017), cancelled a few months after being started without any explanation.

“When I joined the pilotage in 1996 they were extending the breakwaters in the Port of Rio Grande and there was a technical study about it, but it was based on such a faulty ABNT standard that it was complemented by a Portobras paper, a company which was extinct some years ago. This outdated standard lasted until commander Resano (CEO of the Cabotage Shipowners Association) requested support for its review in 2012. We started doing so and for five years worked on its upgrade. Unfortunately, the approved standard impacted third-party economic interests that lobbied for its cancellation in 2017. At that time, we got together to produce this book, based on the world’s best references”, stressed Marcelo Cajaty, vice-president of the National Pilots’ Federation (Fenapráticos).

Professor Edson Mesquita said that all port-related technical standards have elapsed, and stressed the book’s differential:

“We combined academic and practical knowhow in a simple language. In the ABNT, we were unable to explain the reason for and the origin of the standardization or publish bibliographic

25 book

references. Now, in the book we can provide explanations because it involves a multidisciplinary group of authors. The concept is the following: As a professor, I can be understood by an engineer, but sometimes I’m unable to talk to a port operator, one who has trained in economics.”

Port Planning – recommendations for nautical accesses can be downloaded free of charge on praticagemdobrasil.org.br/livros

The preface is signed by Vice-Admiral Wilson Pereira de Lima Filho, former president of the Maritime Court, in Rio de Janeiro, where the book was first released.

26 book

photos: Tico Fonseca

EDSON MESQUITA EDUARDO TANNURI

MARCELO CAJATY RICARDO FALCÃO

GUESTS LISTEN TO THE ADDRESS BY PRESIDENT RICARDO FALCÃO

Tugs and wind drift

Identifying a safe means of tug approach in high winds

Experience remains a crucial factor for safe ship handling, even as tugs are becoming more and more capable. This includes the need for the Master and pilot of the vessel to have an insight into the circumstances under which the tug master is operating.

Proper communication and information exchange between pilot and tug master is essential for safe ship handling and for the safety of the tug and its crew. The pilot knows what information a tug master needs, and in the case that it is not provided, a well trained tug master will request it.

There are, however, a few occasions where the tug master may not get the specific information needed – or even be neglected altogether. This can lead to very risky situations for a tug, its crew, and the ship alike.

Let us take the case of a large ferry, operating in cross winds of Beaufort force 7-8. These ships do not usually use tugs, often taking them only in adverse weather conditions, so will have less experience in their use. The same considerations will to a certain extent also apply to other high windage ships, particularly those with a relatively low draft.

THE VESSEL

Length o.a. 240m

Length p.p. 224m

Draught 6m

Two 4,000 HP bow thrusters

Estimated lateral wind area: 7000m2

Estimated lateral underwater area: 1350m2

Hydrodynamic conditions

Water depth: 15 metres

Underkeel clearance: 9 metres

Depth: draft ration: 2.5

WIND CONDITIONS

Wind direction: About 110° from the bow

Mean wind speed 1: 7 Bft = 15.5m/sec 30 secs gusts: 18.8m/sec

Mean wind speed 2: 8 Bft = 18.9m/sec, 30 sec gusts: 22.9m/sec.

Note: The Beaufort wind speed is given over an average of at least 10 minutes. The ferry may react to gusts of 30 secs average. A gust factor of 1.21 has therefore been applied.

FACTORS AFFECTING SHIP BEHAVIOUR

A crucial factor is how fast the ship will drift due to the wind. High windage ships with a relatively low draft will drift faster than the same ship when deep loaded. Although draft is an important factor, underkeel clearance, hull shape, bilge keels, etc, are also important parameters. For instance, ships will tend to drift aside more easily where there is a large underkeel clearance, as will ships with a less boxshaped hull.

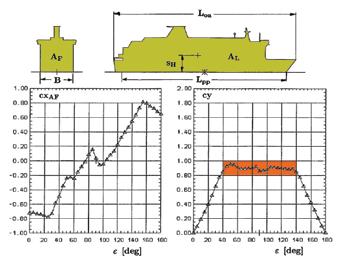

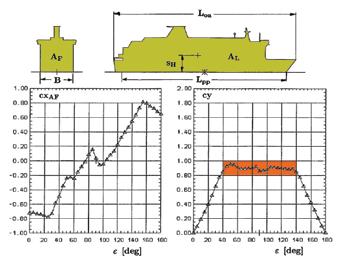

Wind drift is largest when the wind is from about three points forward of the beam to three points aft of the beam (see figure 1). Let us assume a wind direction of about two points aft of the starboard beam, about 110° from the bow, when the ship is not yet steering a drift angle.

Even where it seems like the situation is steady, the fluctuating wind requires the ship to steer a varying course to compensate

27 article

Capt Henk Hensen FNI

handling, even includes an master is pilot and the needs, will may not altogether. ship alike. of taking experience also apply low draft.

Factors affecting ship behaviour

A crucial factor is how fast the ship will drift due to the wind. High windage ships with a relatively low draft will drift faster than the same ship when deep loaded. Although draft is an important factor, underkeel clearance, hull shape, bilge keels, etc, are also important parameters. For instance, ships will tend to drift aside more easily where there is a large underkeel clearance, as will ships with a less boxshaped hull.

Wind drift is largest when the wind is from about three points forward of the beam to three points aft of the beam (see figure 1). Let us assume a wind direction of about two points aft of the starboard beam, about 110° from the bow, when the ship is not yet steering a drift angle.

for gusts. When a cross wind gust strikes the ship, the ship may start to turn. The Master is likely to compensate for this by increasing rudder angle, and probably by increasing power too. The immediate consequence of this action is that sideways drift will increase before the intended course is achieved. This may cause additional risk for any tugs on the lee side, especially if any corrective action taken by the ship is not communicated to the tug.

Even where it seems like the situation is steady, the fluctuating wind requires the ship to steer a varying course to compensate for gusts. When a cross wind gust strikes the ship, the ship may start to turn. The Master is likely to compensate for this by increasing rudder angle, and probably by increasing power too. The immediate consequence of this action is that sideways drift will increase before the intended course is achieved. This may cause additional risk for any tugs on the lee side, especially if any corrective action taken by the ship is not communicated to the tug.

To ensure the safety of tugs, it is essential that tug masters are kept continuously informed about all ship manoeuvres when approaching the bow to fasten a towline – even what may appear minor compensatory changes to maintain course and steering.

To ensure the safety of tugs, it is essential that tug masters are kept continuously informed about all ship manoeuvres when approaching the bow to fasten a towline – even what may appear minor compensatory changes to maintain course and steering.

DRIFT SPEEDS

To calculate the drift speeds, the drag coefficients for cross currents are needed.

Given a current angle of 90° and a water depth/draft ratio of 2.5, a Cyc = 1.2 is taken into account. The underwater area is Draft x Lpp = approximately 1350m2.

This gives the following drift speeds:

• Wind force 7 Bft: Drift speed: 1.38m/sec = 2.8kn

• Wind force 8 Bft: Drift speed: 1.68m/sec = 3.4kn

In other words, in five seconds, the ship will drift: 7 metres in 7 Bft winds; 8.5 metres in 8 Bft winds.

EFFECTS ON THE SHIP

What do these conditions mean, for the ship, and for the tug?

The drift angle which the ship steers will depend on its speed. The maximum safe speed for passing a towline near the bow of a ship having headway is 6 knots. However, because a speed of 6 knots could be too low for the ship to maintain its course in high winds, we will also look at the effects of the less safe speeds of 7 and 8 knots. The various drift angles are shown below.

Read Seaways online at www.nautinst.org/seaways

The right hand graph shows the wind drag coefficient Cy which hardly changes between wind attack angles 40 – 140 degrees.

16/12/2021 17:11

WIND FORCES

For ferries, wind drag coefficient for a wind angle of 90° varies between Cyw = 1.0 and 0.9. We will assume a wind drag coefficient of 1.0. Although the wind direction may differ, the wind drag coefficient itself hardly changes between rather large angles forward and aft of the beam as shown in Figure 1.

The calculated wind forces on the ferry for the two wind speeds are then:

• For wind speed 1 (7 Bft): 162 metric tons

• For wind speed 2 (8 Bft): 240 metric tons

The higher the ship speed, the smaller the drift angle to steer. Note that as the ship speed increases, so do the risks for the tug near the bow, due to the interaction effects between tug and ship.

Use of the bow thruster and stern propellers can to some extent compensate for sideways drift, although the effectiveness of the bow thruster decreases as the ship speed increases. The ship’s pilot or master should inform the tug master that the bow thrusters

28 article

Figure 1. Wind load coefficients of a passenger/car ferry: LOA 161m; beam 29m (Blendermann, 2004)

Wind speed 7 Bft Wind speed 8 Bft Sideways drift 2.8 knots Sideways drift 3.4 knots Ship speed Drift angle to steer 6 knots 27° 32° 7 knots 23° 28° 8 knots 20° 24°

least gust

Figure 1. Wind load coefficients of a passenger/car ferry: LOA 161m; beam 29m (Blendermann, 2004) The right hand graph shows the wind drag coefficient Cy which hardly changes between wind attack angles 40 – 140 degrees.

Feature: Tugs and wind drift

Feature: Tugs and wind drift

Feature: Tugs and wind drift

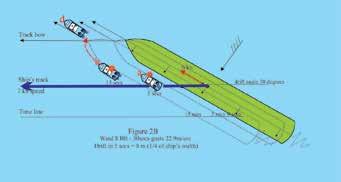

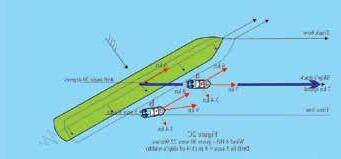

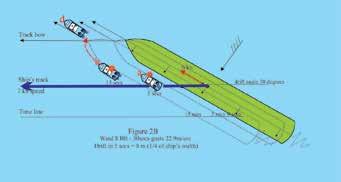

The situation shown in figure 2B, above, with wind force 8 Bft, is even worse. The ship speed is now 6 knots, and the vessel is steering a drift angle of 30 degrees. Everything that has been said about the tug positioning with wind force 7 Bft applies with even more urgency here.

In both situations, the tug master could give astern on the engines/ thrusters to get away from the vessel, instead of increasing speed with port rudder or port thruster angles. However, does that make any sense here? Would the tug get free from the drifting ship? An ASD tug might manage it, but with the conventional type of tug it becomes very problematic.

The situation shown in figure 2B, above, with wind force 8 Bft, is even worse. The ship speed is now 6 knots, and the vessel is steering a drift angle of 30 degrees. Everything that has been said about the tug positioning with wind force 7 Bft applies with even more urgency here.

The situation shown in figure 2B, above, with wind force 8 Bft, even worse. The ship speed is now 6 knots, and the vessel is steering drift angle of 30 degrees. Everything that has been said about the positioning with wind force 7 Bft applies with even more urgency In both situations, the tug master could give astern on the engines/ thrusters to get away from the vessel, instead of increasing speed port rudder or port thruster angles. However, does that make any sense here? Would the tug get free from the drifting ship? An ASD might manage it, but with the conventional type of tug it becomes problematic.

The situation shown in figure 2B, above, with wind force 8 Bft, is even worse. The ship speed is now 6 knots, and the vessel is steering a drift angle of 30 degrees. Everything that has been said about the tug positioning with wind force 7 Bft applies with even more urgency here.

In both situations, the tug master could give astern on the engines/ thrusters to get away from the vessel, instead of increasing speed with port rudder or port thruster angles. However, does that make any sense here? Would the tug get free from the drifting ship? An ASD tug might manage it, but with the conventional type of tug it becomes very problematic.

In both situations, the tug master could give astern on the engines/ thrusters to get away from the vessel, instead of increasing speed with port rudder or port thruster angles. However, does that make any sense here? Would the tug get free from the drifting ship? An ASD tug might manage it, but with the conventional type of tug it becomes very problematic.

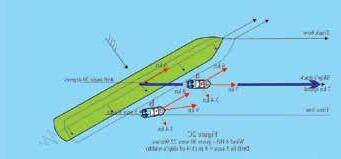

If the tug master has been informed of the drift angle, track speed and direction, the tug master could use this knowledge to anticipate the ship’s movements, as shown in figure 2C, below left. Here, the arrows at position a shows the direction and speed required to keep pace with the ship. The smaller red arrows in situation b show how the tug can move forward along the ship without coming close. In theory this looks feasible, but in practice it will be a very risky manoeuvre to keep the tug in a safe position on the leeside of the fast drifting ship.

it will be a very risky manoeuvre to keep the tug in a safe position on the leeside of the fast drifting ship.

Picking up the towline on the windward side of the ship is not an option.

A BETTER SOLUTION

Picking up the towline on the windward side of the ship is not an option.

A better solution

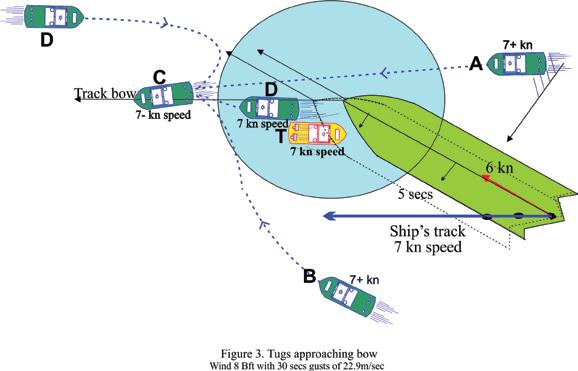

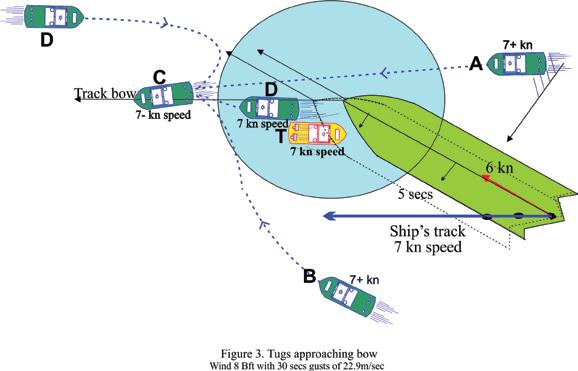

If the tug master is well informed, then there are better ways to approach the bow. These are discussed below, and illustrated in Figure 3, below. All these options are suitable for ASD tugs operating over the bow and tractor tugs, but also for highly manouverable conventional tugs and ASD tugs operating over the stern.

If the tug master has been informed of the drift angle, track speed and direction, the tug master could use this knowledge to anticipate the ship’s movements, as shown in figure 2C, below left. Here, the arrows at position a shows the direction and speed required to keep pace with the ship. The smaller red arrows in situation b show how the tug can move forward along the ship without coming close. In theory this looks feasible, but in practice it will be a very risky manoeuvre to keep the tug in a safe position on the leeside of the fast drifting ship.

If the tug master is well informed, then there are better ways to approach the bow. These are discussed below, and illustrated in Figure 3, below. All these options are suitable for ASD tugs operating over the bow and tractor tugs, but also for highly manouverable conventional tugs and ASD tugs operating over the stern.

If the tug master has been informed of the drift angle, track speed and direction, the tug master could use this knowledge to anticipate the ship’s movements, as shown in figure 2C, below left. Here, the arrows at position a shows the direction and speed required to keep pace with the ship. The smaller red arrows in situation b show how the tug can move forward along the ship without coming close. In theory this looks feasible, but in practice it will be a very risky manoeuvre to keep the tug in a safe position on the leeside of the fast drifting ship.

Picking up the towline on the windward side of the ship is not an option.

If the tug master has been informed of the drift angle, track speed and direction, the tug master could use this knowledge to anticipate the ship’s movements, as shown in figure 2C, below left. Here, the arrows at position a shows the direction and speed required to keep pace with the ship. The smaller red arrows in situation b show how the tug can move forward along the ship without coming close. In theory this looks feasible, but in practice

One possibility is for the tug to approach the ship from the windward side, coming in at position A. From here it can pass the bow of the ship at a safe distance. The course to steer is roughly parallel to the ship’s track (see dotted blue line inidicating tug’s course to steer and solid blue arrow indicating ship’s track).

Picking up the towline on the windward side of the ship is not an option.

A better solution

A better solution

The tug master may choose to alter the course somewhat to port or starboard to pass the ship’s bow at a closer or wider distance. Tug’s speed should be higher than 7 knots.

The situation shown in figure 2B, above, with wind force 8 Bft, is even worse. The ship speed is now 6 knots, and the vessel is steering a drift angle of 30 degrees. Everything that has been said about the tug positioning with wind force 7 Bft applies with even more urgency here. In both situations, the tug master could give astern on the engines/ thrusters to get away from the vessel, instead of increasing speed with port rudder or port thruster angles. However, does that make any sense here? Would the tug get free from the drifting ship? An ASD tug might manage it, but with the conventional type of tug it becomes very problematic.

If the tug master is well informed, then there are better ways to approach the bow. These are discussed below, and illustrated in Figure 3, below. All these options are suitable for ASD tugs operating over the bow and tractor tugs, but also for highly manouverable conventional tugs and ASD tugs operating over the stern.

One possibility is for the tug to approach the ship from the windward side, coming in at position A. From here it can pass the bow of the ship at a safe distance. The course to steer is roughly parallel to the ship’s track (see dotted blue line inidicating tug’s course to steer and solid blue arrow indicating ship’s track).

Having passed the ship’s bow (position C), speed can be decreased and tug’s heading can be changed somewhat to port. This allows the ship to approach the tug, which controls its position relative to the ship’s bow by heading and speed settings. The tug therefore comes into the lee of the bow. A heaving line can then be thrown from the ship’s bow to the tug.

If the tug master is well informed, then there are better ways to approach the bow. These are discussed below, and illustrated in Figure 3, below. All these options are suitable for ASD tugs operating over the bow and tractor tugs, but also for highly manouverable conventional tugs and ASD tugs operating over the stern.

One possibility is for the tug to approach the ship from the windward side, coming in at position A. From here it can pass the bow of the ship at a safe distance. The course to steer is roughly parallel to the ship’s track (see dotted blue line inidicating tug’s course to steer and solid blue arrow indicating ship’s track).

The tug master may choose to alter the course somewhat to port or starboard to pass the ship’s bow at a closer or wider distance. Tug’s speed should be higher than 7 knots.

Alternatively, the tug may approach from position B, at a safe distance from the ship, or from position D. In each case, the tug should manoeuvre towards position C and then follow the same procedure as above.

One possibility is for the tug to approach the ship from the windward side, coming in at position A. From here it can pass the bow of the ship at a safe distance. The course to steer is roughly parallel to the ship’s track (see dotted blue line inidicating tug’s course to steer and solid blue arrow indicating ship’s track).

The tug master may choose to alter the course somewhat to port or starboard to pass the ship’s bow at a closer or wider distance. Tug’s speed should be higher than 7 knots.

The tug master may choose to alter the course somewhat to port or starboard to pass the ship’s bow at a closer or wider distance. Tug’s speed should be higher than 7 knots.

A tractor tug can follow the same procedure.

Having passed the ship’s bow (position C), speed can be decreased and tug’s heading can be changed somewhat to port. This allows the ship to approach the tug, which controls its position relative to the ship’s bow by heading and speed settings. The tug therefore comes into the lee of the bow. A heaving line can then be thrown from the ship’s bow to the tug.

Having passed the ship’s bow (position C), speed can be decreased and tug’s heading can be changed somewhat to port. This allows the ship to approach the tug, which controls its position relative to the ship’s bow by heading and speed settings. The tug therefore comes into the lee of the bow. A heaving line can then be thrown from the ship’s bow to the tug.

Having passed the ship’s bow (position C), speed can be decreased and tug’s heading can be changed somewhat to port. This allows the ship to approach the tug, which controls its position relative to the ship’s bow by heading and speed settings. The tug therefore comes into the lee of the bow. A heaving line can then be thrown from the ship’s bow to the tug.

Alternatively, the tug may approach from position B, at a safe distance from the ship, or from position D. In each case, the tug should manoeuvre towards position C and then follow the same procedure as

Alternatively, the tug may approach from position B, at a safe distance from the ship, or from position D. In each case, the tug should manoeuvre towards position C and then follow the same procedure as above.

Alternatively, the tug may approach from position B, at a safe distance from the ship, or from position D. In each case, the tug should manoeuvre towards position C and then follow the same procedure as above.

A tractor tug can follow the same procedure.

A tractor tug can follow the same procedure.

A tractor tug can follow the same procedure.

An ASD tug operating over the bow in order to assist bow-to-bow (tug T, in yellow) should preferably start from position A, sailing stern first across the vessel’s bow towards position C and then reducing the speed and regulating the heading to let the leeside of the ship’s bow approach the tug. Once the tug has come close enough to the bow, the speed should be regulated to ensure that it stays at a safe distance from the bow.

30 article

Figure 2B. Wind 8 Bft – 30 secs gusts 22.9m/sec Drift in 5 secs = 8m (1/4 of ship's width)

Figure 2C. Wind 8 Bft – gusts 30 secs 22.9m/sec Drift in 5 secs = 8m (1/4 of ship's width)

Feature: Tugs and wind drift 8 | Seaways | January 2022 Read Seaways online at www.nautinst.org/seaways

WHICH TO CHOOSE?

The key difference between options A, B and D is that approaching from position A gives a better insight into the ship’s movements, such as drift and speed. The ship’s heading may change during a tug approach due to the fluctuating wind. Therefore, although the tug master should be informed of any changes, a tug approaching from position A will have a better view of ship movements as it passes rather close to the bow, regardless of any information given, and can better anticipate and control the tug’s position in relation to the ship.

It would be good to test and train these manoeuvres on a ship bridge simulator. If doing so, please be aware that the close hydrodynamic ship – tug interaction may not be accurately modeled in the simulator and a nearby position may seem safer in the simulator than it is in real life.

ship to approach the tug, which controls its position relative to the ship’s bow by heading and speed settings. The tug therefore comes into the lee of the bow. A heaving line can then be thrown from the ship’s bow to the tug.

Alternatively, the tug may approach from position B, at a safe distance from the ship, or from position D. In each case, the tug should manoeuvre towards position C and then follow the same procedure as above.

A tractor tug can follow the same procedure.

Note:

It has been shown that approaching the ship on the leeside to pass a heaving line poses risks for the tug and its crew. This is potentially a very stressful situation for a tug master, and the risks may be increased by the following instinctive reactions:

1 A tendency to quickly turn the thrusters. No problem with that. However, a combination of quickly turning the thrusters while proceeding at a rather high speed may cause a large angle of attack of the nozzle openings versus the direction of the inflowing water.

This may result in thrust reduction and consequently in speed reduction.

2 A tendency to oversteer, meaning that a larger angle than necessary is selected. This is often afterwards followed by a smaller angle as the tug starts to react. Both oversteering and understeering have an adverse effect on thrust.

When positioned close to the ship, any thrust reductions may have a disastrous outcome when the tug master tries to keep sufficient distance and may so collide with the ship.

31 article

8 | Seaways | January 2022

Seaways online at www.nautinst.org/seaways

Wind 8 Bft with 30 secs gusts of 22.9m/s

Read

Wind drift lrb.indd 8 16/12/2021 17:12

AT A GLANCE

This discussion and the following conclusions apply specifically to crosswinds – that is, from about 30 degrees before the beam to 30 degrees aft of the beam.

Most importantly, it is essential that the ship’s pilot, Master or mate informs the tug master of ship’s speed, drift angle steered and the direction and speed of the ship.

The best way for an ASD tug or tractor tug is to approach the ship from the windward side, cross the bow and manoeuvre the tug into a position where the ship will approach the tug with its leeside, as shown in Figure 3. A heaving line can then be sent over from the ship’s bow.

The tug’s position can be precisely controlled, and the tug can easily enlarge the distance if the ship comes too close. A good manoeuvrable conventional tug could also follow this procedure.

Other lessons to be learned include:

• The drift angle to be steered depends on ship size and draft, etc, but also on the safe speed for working with tugs, particulary bow tugs. This safe speed is in general about 6 knots. In strong cross winds, it can become very difficult to control a large high windage vessel at such a low speed and speeds may rise to 7 knots or more.

• It is difficult for the tug master to see drift speed and drift angle steered, particularly when there are few visible cues and in darkness, rain or snow.

• Not being aware that the ship is steering a drift angle due to high winds includes risks for the attending tugs, tug crew and the ship to be assisted.

• Ship’s pilot or master should inform the tug master if the bow thrusters are running as this may affect the flow pattern around the bulbous bow.

• Conventional tug types and ASD tugs operating over the stern should not approach a drifting ship from the lee side. If drift speed is not more than about 1 knot, tractor tugs may be able to operate at the leeside, although utmost care is needed.

It is strongly recommended to test, and if necessary, to train the above manoeuvres on a ship bridge simulator with pilots and tug masters for the high windage ships that call at the port, particularly for those ships that do not normally use tugs.

Nota: Foi demonstrado que se aproximar de um navio por sotavento para passar uma retinida causa riscos ao rebocador e a sua guarnição. É, potencialmente, uma situação muito estressante para um mestre de rebocador, e os riscos podem aumentar pelas seguintes reações instintivas:

1 Uma tendência a mudar subitamente o ângulo dos propulsores Não existe problema com isso; no entanto, a combinação de mudança súbita do ângulo dos propulsores com navegação em velocidade razoavelmente alta pode causar um grande ângulo de ataque entre as aberturas dos túneis e a direção da água que flui para dentro, o que pode resultar em redução na propulsão e consequentemente na velocidade

2 Uma tendência a exagerar no ângulo de governo, o que significa selecionar ângulo maior do que o necessário. Isso é frequentemente seguido por um ângulo menor quando o rebocador começa a reagir. Um ângulo excessivo de governo, tanto quanto um insuficiente, tem efeito adverso sobre a propulsão. Se o rebocador está posicionado próximo ao navio, quaisquer reduções na propulsão podem ter resultados desastrosos quando o mestre do rebocador tenta manter distância suficiente, podendo, assim, abalroar o navio.

é, em geral, de cerca de 6 nós. Sob ventos fortes pelo través, podese tornar muito difícil controlar um navio com muita área vélica em velocidade tão baixa; nesse caso, ela poderá ser aumentada para 7 nós ou mais.

• É difícil para o mestre do rebocador identificar a velocidade e o ângulo de deriva com que o navio está sendo conduzido, particularmente quando existem poucas referências visíveis e na escuridão, sob chuva ou neve.

• Desconhecer que o navio está sendo governado com um ângulo de deriva devido a ventos fortes implica riscos para os rebocadores que prestam assistência ao navio, suas guarnições e para o navio que está sendo assistido.

• O prático ou o comandante do navio deve informar ao mestre do rebocador se os bow thrusters estão em operação, visto que isso pode afetar o padrão de fluxo da água à volta da proa bulbosa.

REFERENCES:

• Rebocadores dos tipos convencional e ASD operando com o guincho de popa não devem se aproximar por sotavento de um navio que deriva. Caso a velocidade de deriva não seja superior a 1 nó, rebocadores do tipo trator podem conseguir operar a sotavento, embora seja necessário o máximo cuidado. Recomenda-se enfaticamente testar e, se necessário, treinar essas manobras em um simulador de passadiço de navio, com práticos e mestres de rebocadores, para navios de grande área vélica que escalam no porto, em particular para aqueles que normalmente não utilizam rebocadores.

1 Ship may encounter high wind loads – a statistical assessment. Blendermann, 2004.

Tugs and wind drift

Referência:

Ships may encounter high wind loads – a statistical assessment. Blendermann, 2004

article 32 Feature: Tugs and wind drift 6 Seaways January 2022 Read Seaways online at www.nautinst.org/seaways Identifying a safe means of tug approach in high winds

Capt Henk Hensen FNI Experience remains a crucial factor for safe ship handling, even as tugs are becoming more and more capable. This includes the need for the Master and pilot of the vessel to have an insight into the circumstances under which the tug master is operating. Proper communication and information exchange between pilot and tug master is essential for safe ship handling and for the safety of the tug and its crew. The pilot knows what information a tug master needs, and in the case that it is not provided, well trained tug master will request it. There are, however, few occasions where the tug master may not get the specific information needed – or even be neglected altogether. This can lead to very risky situations for a tug, its crew, and the ship alike. Let us take the case of a large ferry, operating in cross winds of Beaufort force 7-8. These ships do not usually use tugs, often taking them only in adverse weather conditions, so will have less experience in their use. The same considerations will to a certain extent also apply to other high windage ships, particularly those with a relatively low draft. Factors affecting ship behaviour A crucial factor is how fast the ship will drift due to the wind. High windage ships with a relatively low draft will drift faster than the same ship when deep loaded. Although draft is an important factor, underkeel clearance, hull shape, bilge keels, etc, are also important parameters. For instance, ships will tend to drift aside more easily where there is a large underkeel clearance, as will ships with a less boxshaped hull. Wind drift is largest when the wind is from about three points forward of the beam to three points aft of the beam (see figure 1). Let us assume a wind direction of about two points aft of the starboard beam, about 110° from the bow, when the ship is not yet steering drift angle. Even where it seems like the situation is steady, the fluctuating wind requires the ship to steer varying course to compensate for gusts. When a cross wind gust strikes the ship, the ship may start to turn. The Master is likely to compensate for this by increasing rudder angle, and probably by increasing power too. The immediate consequence of this action is that sideways drift will increase before the intended course is achieved. This may cause additional risk for any tugs on the lee side, especially if any corrective action taken by the ship is not communicated to the tug. To ensure the safety of tugs, it is essential that tug masters are kept continuously informed about all ship manoeuvres when approaching the bow to fasten a towline – even what may appear minor compensatory changes to maintain course and steering. The vessel Length o.a. 240m Length p.p. 224m Draught 6m Two 4,000 HP bow thrusters Estimated lateral wind area: 7000m Estimated lateral underwater area: 1350m2 Hydrodynamic conditions Water depth: 15 metres Underkeel clearance: 9 metres Depth: draft ration: 2.5 Wind conditions Wind direction: About 110° from the bow Mean wind speed 1: 7 Bft = 15.5m/sec 30 secs gusts: 18.8m/sec Mean wind speed 2: 8 Bft = 18.9m/sec, 30 sec gusts: 22.9m/sec. Note: The Beaufort wind speed is given over an average of at least 10 minutes. The ferry may react to gusts of 30 secs average. A gust factor of 1.21 has therefore been applied. Figure 1. Wind load coefficients of a passenger/car ferry: LOA 161m; beam 29m (Blendermann, 2004) The right hand graph shows the wind drag coefficient Cy which hardly changes between wind attack angles 40 – 140 degrees.

passadiço de navio. Caso venha a fazê-lo, esteja consciente de que a interação causada pela proximidade navio/rebocador pode não ser acuradamente modelada no simulador, e uma posição próxima ao navio pode parecer mais segura no simulador do que na vida real.

Manobra de um navio com borda-livre alta sob condições tranquilas

–

sob fortes ventos, as coisas são bem diferentes Leia Seaways online em www.nautinst.org/seaways Janeiro 2022 | Seaways |9

Originally published in the Nautical Institute Magazine Seaways, in association with the Royal Institute of Navigation in January 2022 and reproduced with the author’s permission www.nautinst.org

Handling a high-sided ship in calm conditions – matters are very different in high winds

Learn about the free projects of Olympic

Former beach volleyball athlete uses her entrepreneurial skills to help sports careers and projects in disadvantaged areas

medalist

Adriana Samuel

One of the pioneers in female beach volleyball in Brazil, with two Olympic medals (silver in Atlanta-1996 and bronze in Sydney-2000), Adriana Samuel took up entrepreneurialism after retiring from the sand. After leaving the volleyball courts for the sand in 1992, she had to chase sponsorship to fund a sport that was not Olympic at that time. Today, she uses her enterprising vocation to manage her team of athletes, one of which is canoeist Isaquias Queiroz, and she runs four social projects, repaying society for what sport has given her.

33 social inclusion

photo : Publicity

“In the second Olympics I already knew I wouldn’t compete in a third and began getting used to the idea of quitting. And that made me think of having a social project. I would discuss this idea at home with my younger brother Tande (Olympic beach volleyball champion). We saw the change that sport made to our lives, in every sense. I clearly remember after winning the medal in Sydney, when a reporter asked me about my plans for the future, my reply was that I would compete only one more year and then would like to have a social project.”

And Adriana stuck to her plan: she quit competing in December 2001. The first project was created in September 2004, after the Athens Games, when she inaugurated her free volleyball school on Copacabana Beach in the presence of medalists Ricardo Santos and Emanuel Rego, recently arrived from Greece. Ten years later, she felt confident and experienced enough to take a major step and opened a second center in Deodoro, in the West Zone of Rio de Janeiro, precisely in the military village, where she had spent her childhood.

“I was driven by a single certainty; I no longer wanted to be in Rio’s South Zone, which was now being overrun by all kinds of projects. We moved to wherever we would make the difference. The Deodoro project lasted seven years. Unfortunately, I was unable to raise enough funds to keep it going, but it’s on my radar to restart it. Every step is tough to transform an idea into reality. Perhaps the easiest thing is to conceive the projects”, says Adriana, who resorts to the state and federal laws for sports incentive.

The ex-athlete turned the key and has shown that she can carry out any social project, not only involving volleyball. She currently has a unit in Caramujo, Niterói, which is completely dedicated to this sport. Her other project, No Barriers [ Sem Barreiras ], offers volleyball, judo and athletics classes in Estácio; and volleyball and judo in Lins de Vasconcelos, both neighborhoods in the Rio North Zone.

The latest project is Gaming Park, in Rocinha. This is a hub of activities that uses mobiles to empower young athletes in eSports, with courses in English, games programming and graphic design. The entrepreneur plans to extend the project to Vitória, Espírito Santo state, her first project outside the state of Rio de Janeiro.

“I’m restless, always with an eye on the trends. Why not a social project focusing on something that is a global fever such as the games? There were over 300 applications in three days. It’s a huge challenge but I’m loving it.”

Adriana feels that the projects make the difference in extremely vulnerable areas, bringing a good structure to the practices, best teachers and the values that sport transmits.

“The feedback from families is invaluable, it’s the oxygen that motivates me to carry on. We hear from parents about the visible changes in their children’s behavior, such as, for example, the matter of discipline. These young people feel welcome, respected and this influences their self-esteem, it brings a feeling of belonging, feeling proud to wear the project’s shirt and knowing that they are part of it. We have no idea how the little things have such a transforming power. It’s as if they had been invisible before. It’s priceless.”

The former player’s projects have a waiting line. To start them from zero and attract the public, public schools in the vicinity are visited. The activities are always held after school hours. Adriana tells how two pupils were hired as structure assembly assistants, although this was not the objective. Others have joined clubs that have asked for talent referral, and some even reach the Juvenile Brazilian team. For example, 18-year-old Cleiton Silva was one of the 3,000 or more students that have been assisted. He started with volleyball in the No Barriers project in Estácio, in 2018, and today also participates in judo.

“I was a very introverted kid, not communicative. The sport helped me to improve. I met new people and learned practices with which I’d had no contact before, I would only see them on TV. One of the things that I like most in the project is the people. Everyone jokes around, has fun and learns from each other”, says the young man, who intends to start competing in judo in 2023.

ABOUT THE PROJECTS

Adriana Samuel Volleyball School, Niterói (Escola de Vôlei Adriana Samuel) – Attends 80 children and young people, from 7 to 17 years old, at the Caramujo Social and Sports Park in Niterói. The project is sponsored by the State Secretariat for Sport and Leisure and Enel Distribuição Rio (energy utility). It originated in 2004 in

social inclusion 34

photo: Publicity

Copacabana, where it lasted 14 years. The second unit operated for seven years in the Dias Gomes Neighborhood Park in Deodoro.

No Barriers Project (Estácio) – It began four years ago in the Municipal Employees’ Club in Estácio. It attends 230 children in three categories: volleyball, judo and athletics. The project is sponsored by the State Secretariat for Sport and Leisure, Itaú Bank and IBM, in addition to support from Capemisa (life insurance company) and the NGO ALDEeA [ Associação Latina de Desenvolvimento Esportivo, Cultural e Ambiental ].

No Barriers Project (Lins de Vasconcelos) – Unit in the Lins de Vasconcelos Complex, North Zone of Rio. The project offers volleyball and judo classes for 210 students from 6 to 17 years old. It is sponsored by Light (energy company) and the State Secretariat for Sport and Leisure.

Gaming Park (Rocinha) – This is Adriana Samuel’s first venture outside traditional sports. The area provides space for 80 young players from 8 to 17 years old. In addition to a room for live streaming and spaces for training, the Gaming Park offers courses in English, games programming and graphic design. The project is in partnership with Light and supported by the Rio de Janeiro State Government Sport Incentive Act.

35 social inclusion

photos: Publicity

EVENTS

RICARDO FALCÃO PARTICIPATES IN THE MEETING WITH ARGENTINE PILOTS

Pilot Ricardo Falcão, Vice-President of the International Maritime Pilots’ Association (Impa) and president of Brazilian Pilots, gave a talk in October at the 2nd National Meeting of Argentine Pilots, organized by the Argentine Pilotage and Ship Handling Chamber. The event marked the 126 years of the profession in the country and was held at the Center of Overseas Captains and Merchant Navy Officers, in Buenos Aires. On that occasion, Ricardo Falcão provided Brazilian pilotage data and investments made by the service in favor of shipping safety and productivity in the ports, in addition to the National Pilotage Council’s technical actions.

ELECTION

GUSTAVO MARTINS IS REAPPOINTED PRESIDENT OF FENAPRÁTICOS

Pilots Gustavo Henrique Martins and Marcelo Cajaty were reappointed president and vice-president, respectively, of the National Pilots’ Federation (Fenapráticos), based in Brasilia, which operates in the labor environment. Completing the Executive Board are Carlos Alberto Rodrigues, continuing as managing director; Adonis dos Santos (financial director); and Pedro Henrique Parente (institutional director).

In September, Gustavo Martins presented the organization chart of Fenapráticos during a seminar at the National Confederation of Workers in Waterway and Air Transports, Fishing and Ports (Conttmaf).

fast & focused 36

photo: Publicity

photo: Paulo Vitor

UNIPILOT BACKS RENOVATION OF LAUNCH FOR SANTARÉM PORT AUTHORITIES

Santarém Waterway Authorities have upgraded the launch LAEP 7 Acari, through a partnership with the Pilots’ Logistics and Support Cooperative of Pilotage Zone 1 (Unipilot). The vessel’s operations include teaching support, patrol and rescue in the rivers of the Amazon. Pilot Adonis dos Santos from Unipilot participated in the hand-over ceremony in November, in the presence of Santarém Port Captain Fabrício Fróes. “Thanks to the Pilotage effort and partnership, we succeeded in having the launch ready for operation. This enabled the military to stay five to six days in activity, taking actions and patrolling in places far from the municipality seat,” stated the captain.

AREIA BRANCA PILOTS EXPECT IMPROVEMENTS THROUGH TERMINAL LEASING

On November 1st, Companhia Docas do Rio Grande do Norte (Codern) delivered the Areia Branca Salt Terminal to the Intersal Lessee Consortium, formed by intermaritime companies and Salinor. The investments expected for the Island Port are BRL 160 million. According to pilot Igor Sanderson, director-president of Areia Branca Pilots, “the change in management will enable improvements in the maintenance of the facilities and equipment, increasing the safety of the maneuvers and productivity, as well as preserving and providing more jobs”.

SPONSORSHIP

BRAZILIAN PILOTS SPONSORS RACE AND WALK IN GRAMADO