8 minute read

A Coronado Family Reflects on Armistice Day

A Coronado A Coronado Family Family Reflects on Reflects on Armistice Day Armistice Day

By Susie Clifford w/ John Lepore

Advertisement

Charles Lepore

Charles and his donkey at Army base near El Paso, Texas

In 1918, on the 11th hour on the 11th day of the 11th month, the signed Treaty of Versailles of World War I went into effect, ceasing the 52 long months of the “war to end all wars.”

November 11 went on to be known as Armistice Day, a day that should be “commemorated with thanksgiving and prayer and exercises designed to perpetuate peace through good will and mutual understanding between nations,” in a resolution passed by Congress in 1926. In 1954, it became Veterans Day, a day to honor all veterans and their organizations.

Two years ago marked the centennial of the Armistice Day. The significance of that date is especially poignant to John Lepore and his family here in Coronado, since John’s father, Charles Lepore, fought in that war. John carries many memories and memorabilia of his dad’s time in the war.

“My father never spoke about when he fought in France with the American Expeditionary Forces in 1918, but he treasured Armistice Day as the one day he could honor his buddies killed in the ‘war to end all wars’” said John.

John found that the movies that commemorate World War I, like “1917” and “They Shall Not Grow Old,” fleshed out some of what his father went through when he served.

John told how his father came to be in the war. “My dad was born in Boston, 1898, into a family of 11 siblings. He struggled getting along with his dad, his school (he was expelled at 12 years old), and his neighborhood. His father made him do odd jobs after he left school for

the next four years until his scraps with the law got worse. He was about 16 when a judge said to his probation officer, “Get him into the Army or he goes to jail.”

That was how Charles Lepore became an Army Reservist.

Within weeks of putting on a uniform, his Army outfit was called upon to capture Pancho Villa, the Mexican bandit who was raiding border towns along the Rio Grande River near El Paso, Texas. Young Charles enjoyed the hunt for Villa almost as much as boxing, drinking and gambling with his Army pals. On one occasion, he became the proud owner of a donkey he won in a poker game. The fighting that caused him so much trouble in Boston, became an asset when he boxed for his Army Company.

The game of playing soldier in Texas was short-lived. He was called back to Boston to be part of the newly formed Yankee Division (YD), preparing to enter World War I in France. The horror of trench warfare on the Western Front of France stood in stark contrast to the traipsing along the Texas border towns. When Charles confessed he lied about his age to sign up for the YD, his sergeant said, “That’s ok. You are assigned to the Ambulance Corps until you age out, then you will go to the front lines and join your unit.”

One night Charles and several other soldiers stole an ambulance and drove to a bar in a small town. On the return trip the drunken doughboys smashed into a pole outside their quarters. The next morning the sergeant wanted the names of the men responsible, or the whole unit would move out to the front lines. Since the troops knew they were due to go to the front anyway, no one volunteered their names.

However, it was sobering for Charles to pick up the battered bodies of Ameri-

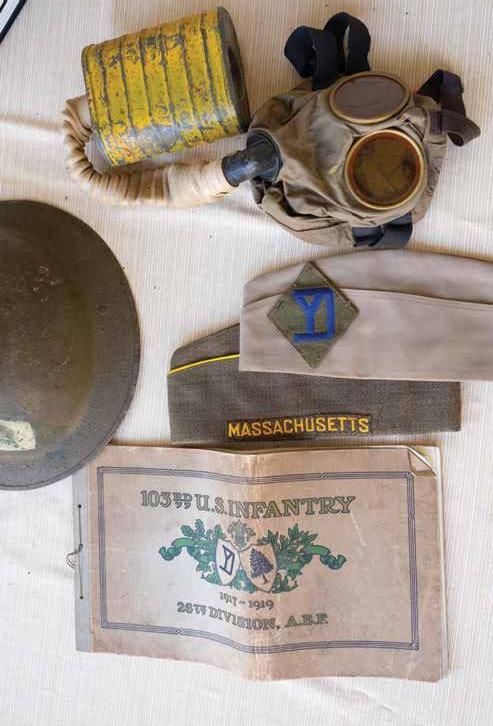

These 100 year old relics of WWI, A helmet and gas mask were worn by Charles Lepore on the Western Front

can soldiers and bring them back. Later it became even more traumatic when he entered trench warfare with all its brutality - the mud, rain, rats, barbed wire, artillery rounds, tank charges and even poison gas attacks.

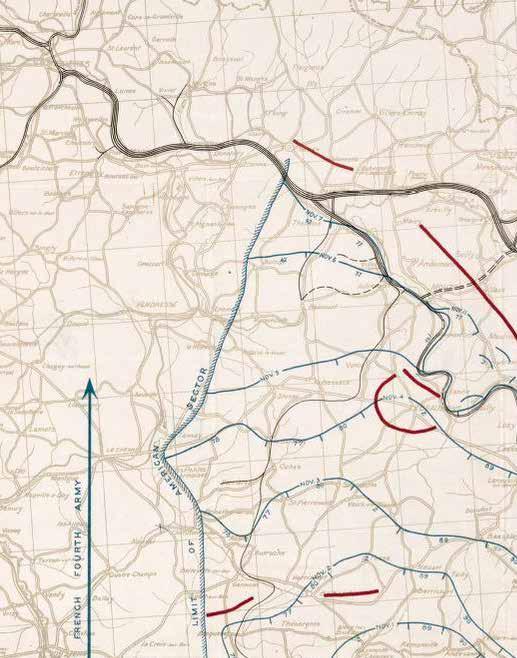

“According to Army records,” said John, “my dad spent most of 1918 battling the Germans on the Western Front. The battles he was engaged in were: Chemin des Dames Section, Toul Sector, Chateau Thierry Offensive, St. Mihiel, Trogon Sector and lastly, the Meuse Argonne Offensive where he was felled by mustard gas.”

The war ended for Charles at this point. He was taken to a hospital in LeMans, France to recover.

“While my father recuperated in the French hospital from the effects of mus-

tard gas, a young woman, named LuLu, would visit my dad and walk him around hospital grounds,” said John. “Her mother accompanied them, always a few yards behind, the custom of the times. I learned of this romance from letters my dad saved. In my home, the name ‘LuLu’ was bandied about jokingly quite a few times, such as ‘I should have married LuLu,’ or conversely, ‘You should have married LuLu.’ This did not deter my parents staying married for 65 years.”

When Charles recovered from his illness, he boarded a troop ship heading home with the last remnants of the American Expeditionary Forces. Upon arriving in Boston in 1919, he immediately passed out. He thought the cause of his distress was sweating from his heavy woolen uniform. In fact, he fell victim to the Spanish Flu of 1918-1919 that struck Europe and America quite hard. Again, Charles was hospitalized for several weeks.

John spoke about his father after the war. “The war in France forever changed my dad, according to his brothers. He gave up his pugilistic past and became a model family man working two jobs most of his life. When in 1941 Pearl Harbor was attacked, four of Charles’ younger brothers enlisted immediately in the Marines and the Army, while my dad tried his best to prepare them for the hell of combat.”

One brother, Capt. Billy Lepore was at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese attacked. He died in the Burma Campaign, and received the Silver Star award posthumously, for saving several of his men.

The Lepore family would march in the annual Armistice Day parade in their hometown, which was a huge affair. Charles and his brothers, veterans all, and their mother, part of the Civilian Defense Organization, and even his grandmother, a Gold Star mother, would take part for many years.

Once out of the service, Charles worked for CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) government camps building roads, then an ice cream factory (his family loved that job), and then finally for the U.S. Post Office for 35 years in Boston, where he retired. Throughout his life, he always worked as a bartender as a second job.

Charles married, had two daughters and one son. John, being the only male that could sign up for the military, followed the tradition of his family and did so in 1966. Unlike his father, he hadn’t been forced into the service. He volunteered from a parish in Hull, Massachusetts, believing that the war in Vietnam was honorable and became part of the Navy Chaplain corps so that he could serve the Marines. He served on active duty for the next seven years and then stayed in the Navy Reserves as a public affairs officer.

Today, John feels strongly about war being the epitome of man’s inhumanity to man. “It is a form of insanity that afflicts us still today, although to a lesser extent than wars of the past. In 1955, Pope Paul VI warned the United Nations in his famous speech ‘War No More - War Never Again’ and if heeded, the world could realistically enter a new golden age of peace. If war is not banned by all nations, the prophecy of John F. Kennedy will be realized, ‘Either mankind will put an end to war, or war will put an end to mankind.’”

John left the Navy Chaplain Corps and the priesthood on the same day in June, 1974, returning home to Everett, Massachusetts, to be a high school counselor and coach for 20 years. He married and eventually they moved to his wife’s hometown, Coronado, in 1994, after he retired. They divorced, but today live on the same street. John found a home in Coronado, stayed and later remarried.

John and his wife Betty have many items of Charle’s time in the service from World War I on display in their home. “I revere my dad’s World War I souvenirs, his helmet and gas mask, as reminders of the sacrifices he and my uncles made in the two world wars of the last century,” said John.

“Despite my dad’s mild demeanor in his post war life, I found that beneath his calm surface, he harbored a simmering anger that rarely percolated out. [But when it did] I learned my father had my back no matter what I did…The war damaged his lungs, but not his devotion to family, especially his only son.”

Military shadow box jointly contain awards Given to PFC Charles Lepore (WWI) and son CDR John Lepore (Vietnam). As John Says “Dad and I share the same shadow box because we didn’t receive a lot of medals in our limited Active Duty - but we both got Purple Hearts. The place of honor in the center of the box is my mom’s arm band. During WW II she served in our city’s Civil Defense Organization. When mock air raids were staged over Greater Boston, she would man her Fire Warden post in the neighborhood, and retrieve ‘ribbon’ bombs for identification.”