Western Andalucia

HUELVA TO MÁLAGA – SPAIN

Crossbill Guides: Western Andalucía – Huelva to Málaga - Spain

First print: 2017

Second print: 2024

Initiative, text and research: Dirk Hilbers

Additional research, text and information: John Cantelo, Luc Hoogenstein, Kim Lotterman, Albert Vliegenthart

Editing: John Cantelo, Brian Clews, Cees Hilbers, Riet Hilbers, Kim Lotterman

Illustrations: Horst Wolter

Maps: Dirk Hilbers

Type and image setting: Oscar Lourens

Print: ORO grafic projectmanagement / PNB Letland

ISBN 978-94-91648-33-5

This book is made with FSC-certified paper. The printing process is CO2-neutral through carbon-offsetting. To compensate for the CO2-emissions of the printing processes, we’ve invested in a reafforestation project plus nature conservation in Europe. For more information, scan the qr-code. You can find the certificate of the carbon-offset on our website under ‘downloads’ on the Western Andalucía guidebook page.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by print, photocopy, microfilm or any other means without the written permission of the Crossbill Guides Foundation.

The Crossbill Guides Foundation and its authors have done their utmost to provide accurate and current information and describe only routes, trails and tracks that are safe to explore. However, things do change and readers are strongly urged to check locally for current conditions and for any changes in circumstances. Neither the Crossbill Guides Foundation nor its authors or publishers can accept responsibillity for any loss, injury or inconveniences sustained by readers as a result of the information provided in this guide.

This guidebook is a product of the non-profit foundation Crossbill Guides. By publishing these books we want to introduce more people to the joys of Europe’s beautiful natural heritage and to increase the understanding of the ecological values that underlie conservation efforts. Most of this heritage is protected for ecological reasons and we want to provide insight into these reasons to the public at large. By doing so we hope that more people support the ideas behind nature conservation. For more information about us and our guides you can visit our website at:

WWW.CROSSBILLGUIDES.ORG

Booted Eagle and Black Kite

2

Common Chameleon

Marvel at the exotic flora and fauna. In addition to flamingos, vultures and eagles, western Andalucía has odd insectivorous plants, Europe’s largest butterflies, giant spiders, chameleons, terrapins and many more astonishing examples of exciting wildlife.

Purple Gallinule

1 Head to Tarifa between late August and late October to witness the great exodus of hundreds of thousands of migrating birds from Europe across the Strait of Gibraltar to Africa (and go back in spring for their return)

3 Visit Coto Doñana, one of Europe’s most important wetlands. In wet springs, the marshes are alive with countless waders and waterfowl.

Los Alcornocales

4 Walk the hills of the leafy Alcornocales, a large expanse of cork oak woods, pierced by secluded valleys with pretty streams which are havens for rare wildflowers and dragonflies.

6 The pretty mountains of Sierra de Grazalema and Sierra de las Nieves are a must see. Exposed karst plateaux alternate with lush valleys and the gloomy, but unique, relict forests of Spanish Fir – all with a very rich flora that includes plenty of orchids.

8 Visit the exotic Laguna de Fuente de Piedra, the second-largest steppe lake in Spain and home to Europe’s secondlargest colony of Greater Flamingos.

5 Feel awed by the limestone plateaux of El Torcal, a superb karst landscape that looks like a petrified metropolis.

7 Head north to the Sierra de Aracena where traditional pig rearing in open holm oak woods is at the heart of a unique ecosystem which is very rich in birds, above all raptors.

Torcal de Antequera

Spanish Early-purple Orchid* (Orchis olbiensis)

Iberico-pigs in the Sierra Morena.

boat trip or ferry crossing

bicycle route

car route beautiful scenery walking route interesting history interesting geology

This guide is meant for all those who enjoy being in and learning about nature, whether you already know all about it or not. It is set up a little differently from most guides. We focus on explaining the natural and ecological features of an area rather than merely describing the site. We choose this approach because the nature of an area is more interesting, enjoyable and valuable when seen in the context of its complex relationships. The interplay of different species with each other and with their environment is astonishing. The clever tricks and gimmicks that are put to use to beat life’s challenges are as fascinating as they are countless. Take our namesake the Crossbill: at first glance it’s just a big finch with an awkward bill. But there is more to the Crossbill than meets the eye. This bill is beautifully adapted for life in coniferous forests. It is used like scissors to cut open pinecones and eat the seeds that are unobtainable for other birds. In the Scandinavian countries where Pine and Spruce take up the greater part of the forests, several Crossbill species have each managed to answer two of life’s most pressing questions: how to get food and avoid direct competition. By evolving crossed bills, each differing subtly, they have secured a monopoly of the seeds produced by cones of varying sizes. So complex is this relationship that scientists are still debating exactly how many different species of Crossbill actually exist. Now this should heighten the appreciation of what at first glance was merely an odd bird with a beak that doesn’t seem to close properly. Once its interrelationships are seen, nature comes alive, wherever you are. To some, impressed by the ‘virtual’ familiarity that television has granted to the wilderness of the Amazon, the vastness of the Serengeti or the sublimity of Yellowstone, European nature may seem a puny surrogate, good merely for the casual stroll. In short, the argument seems to be that if you haven’t seen a Jaguar, Lion or Grizzly Bear, then you haven’t seen the ‘real thing’. Nonsense, of course. But where to go? And how? What is there to see? That is where this guide comes in. We describe the how, the why, the when, the where and the how come of Europe’s most beautiful areas. In clear and accessible language, we explain the nature of Andalucía and refer extensively to routes where the area’s features can be observed best. We try to make Andalucía come alive. We hope that we succeed.

This guidebook contains a descriptive and a practical section. The descriptive part comes first and gives you insight into the most striking and interesting natural features of the area. It provides an understanding of what you will see when you go out exploring. The descriptive part consists of a landscape section (marked with a red bar), describing the habitats, the history and the landscape in general, and of a flora and fauna section (marked with a green bar), which discusses the plants and animals that occur in the region.

The second part offers the practical information (marked with a purple bar). A series of routes (walks and car drives) are carefully selected to give you a good flavour of all the habitats, flora and fauna that western Andalucía has to offer. At the start of each route description, a number of icons give a quick overview of the characteristics of each route. These icons are explained in the margin of this page. The final part of the book (marked with blue squares) provides some basic tourist information and some tips on finding plants, birds and other animals.

There is no need to read the book from cover to cover. Instead, each small chapter stands on its own and refers to the routes most suitable for viewing the particular features described in it. Conversely, descriptions of each route refer to the chapters that explain more in depth the most typical features that can be seen along the way.

In the back of the guide we have included a list of all the mentioned plant and animal species, with their scientific names and translations into German and Dutch. Some species names have an asterix (*) following them. This indicates that there is no official English name for this species and that we have taken the liberty of coining one. We realise this will meet with some reservations by those who are familiar with scientific names. For the sake of readability however, we have decided to translate the scientific name, or, when this made no sense, we gave a name that best describes the species’ appearance or distribution. Please note that we do not want to claim these as the official names. We merely want to make the text easier to follow for those not familiar with scientific names. An overview of the area described in this book is given on the map on page 15. For your convenience we have also turned the inner side of the back flap into a map of the area indicating all the described routes. Descriptions in the explanatory text refer to these routes.

site for snorkelling

interesting for whales and dolphins

visualising the ecological contexts described in this guide interesting flora interesting invertebrate life interesting reptile and amphibian life interesting mammals interesting birdlife

Western Andalucía is a hugely diverse and endlessly fascinating region. Between the barren thirsty karst plateaux high in the mountains and the marshy coastal flats of Coto Doñana lies a superb range of landscapes. There are Arcadian cork oak orchards and cool, shady, jungle-like river valleys, but also natural steppe lakes (rare in Europe!) and rocky plains that are extremely exposed and hot. There are wild gorges that cut deep into the bedrock and equally wild cliffs that tower high above the surrounding land – in short, the variation in landscape of western Andalucía is enormous.

What remains pretty much constant though, is the general intactness of it all. The marshes of Coto Doñana are a true gem. At its margin is a beach which is, at 25 kms, the longest unspoilt one in Spain. Except for a few minor roads and pretty whitewashed villages, the oak woods of the Sierra Morena run, uninterrupted, for hundreds of kilometres. The Alcornocales and Sierra de Grazalema are similarly wild. The wildlife of western Andalucía matches this diversity and grandeur. There are plenty of butterflies, numerous rare dragonflies and scores of reptiles and amphibians. The flora consists of plants adapted to severe drought as well as those that require permanent dampness and everything in between. But nothing beats the birdlife. It is hard to name an area in Europe with a higher diversity of birds. From the familiar iconic ones like Greater Flamingo, Hoopoe and Bee-eater to the more obscure and rare African birds as White-rumped Swift and Rüppell’s Vulture and flagship species of large undisturbed areas such as Spanish Imperial and Bonelli’s Eagle – western Andalucía has it all. In addition, the area is washed over twice a year by millions of migrant birds that cross the Straits of Gibraltar on their way to and from breeding or wintering quarters. You get the picture – visit western Andalucía once and you want to return over and over again. This book will help you get to the best sites and tell you where to go and what to look for. Vámos!

The landscape of western Andalucía has many dramatic features, such as the secluded Garganta Verde gorge (route 14).

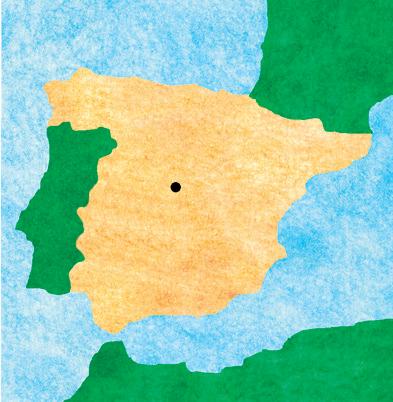

Andalucía is the southernmost of the fifteen autonomous regions of mainland Spain. It spreads from the Portuguese border in the west all along the south coast to the autonomous region of Murcia in the east, Castilla–La Mancha in the northeast and Extremadura in the northwest. Andalucía is divided into eight provinces, of which Huelva, Sevilla, Cádiz and Málaga are covered in this guidebook on western Andalucía and others in a second volume on eastern Andalucía.

Overview of western Andalucía Sierra

Castilla –La Mancha

From a topographical perspective, there are four distinctive landscapes in western Andalucía. In the north, bordering Extremadura and Castilla–La Mancha, are the rolling, wooded hills of the Sierra Morena. In the south rise the rugged mountains of the Sierra Baetica, which stretch out from Gibraltar all the way east along the coast towards the Sierra Nevada and Sierra de Cazorla in eastern Andalucía. Like a wedge between these two ranges lies the large lowland depression of the Guadalquivir river. The fourth and final region is the coastal strip, with its mixture of saltmarshes, fossilised dunes and rolling hills.

The Sierra Morena is an extensive, 400 km long range of hills and low mountains that stretch from the Portuguese border to the province of Jaén. The landscape is sparsely populated, covered in dehesas (oak groves), scrubland, some pine and eucalyptus plantations and pockets of original Mediterranean woodland. The landscape and its nature is reminiscent of Extremadura and Castilla–La Mancha, of which it is geologically a part. Almost all of the Sierra Morena is protected by a series of Parques Naturales.

The central basin of Andalucía is the centre of human activity – this is where the big cities of Sevilla, Córdoba, Huelva, and, further east, Jaén are situated. It is also one of the agricultural powerhouses of Spain: endless fields and olive groves surround the towns and villages. The central part of the Guadalquivir basin – roughly the region between Sevilla and Córdoba – is the hottest part of mainland Spain. The natural attraction of this plain lies in the presence of dry steppes (many of which are now degraded) and complexes of temporary lagoons.

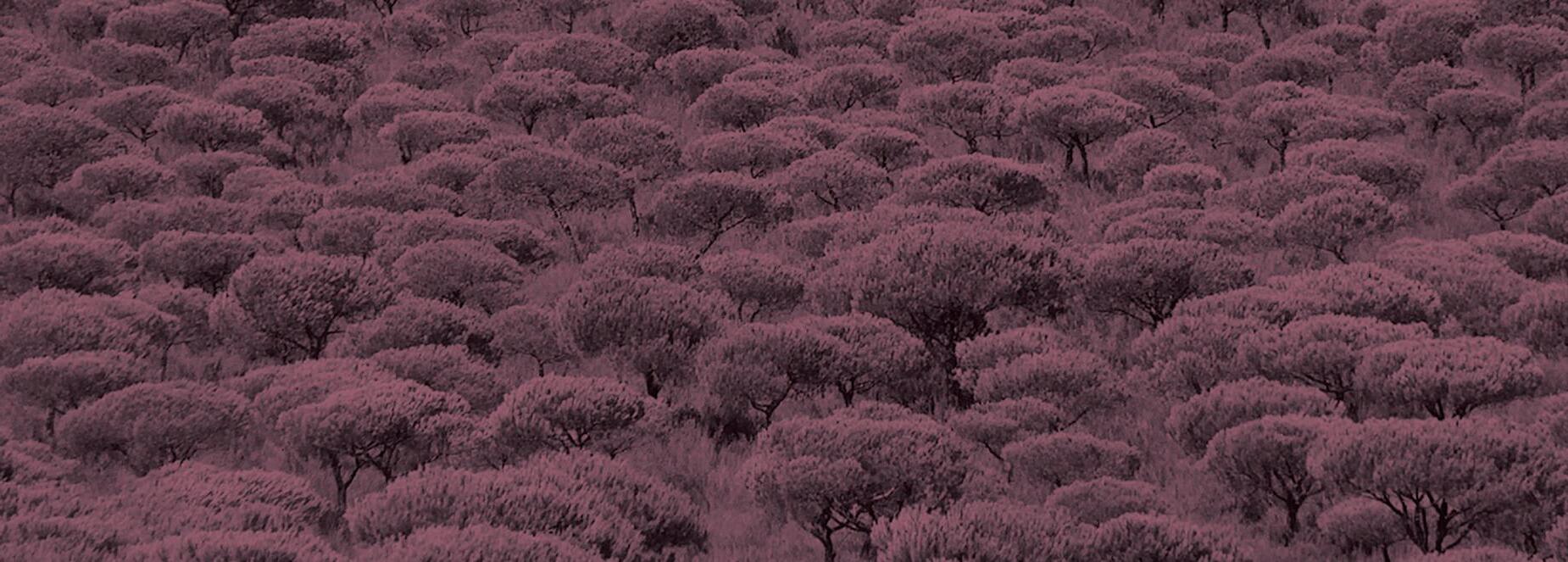

The rivers that drain the central basin have formed a large lowland plain all along the Atlantic coast. Extensive coastal marshes, known as

marismas , support a very rich flora and fauna. The largest and most famous of these coastal marshes are those of the Coto Doñana National Park. Together with the surrounding scrublands and umbrella pine forests they are one of the key regions for visiting naturalists. The coast west of Gibraltar is also known as the Costa de la Luz (the coast of light). It is one of the least developed of all the Spanish ‘costas’. Here the salinas and creeks of the Bahía de Cádiz constitute one of the largest areas of estuarine habitat in Spain. Further east, the Campo de Gibraltar forms a mixture of rolling foothills of the Sierra Baetica and river valleys and small estuaries. The almost subtropical climate makes this a distinct region from a biological point of view.

The Costa del Sol, which runs from Algeciras to Málaga, is unlike the Costa de la Luz, heavily developed and, as a result, it is not as attractive for naturalists.

The Sierra Baetica is completely different from the Sierra Morena. The landscape is more varied, with dense cork oak forests in some parts and elsewhere with barren limestone plateaux, dissected by steep gorges. Geologically, the Sierra Baetica is part of a complex range that extends from the Moroccan Rif mountains to Mallorca. They are much younger than the Sierra Morena and the mountains of central Spain, and have a very different flora and fauna.

The section of the Sierra Baetica that lies within the area of this book, has two very different faces. Its western part is dominated by Los Alcornocales – a huge and little populated area of sandstones, covered in cork oak forests and dissected by humid valleys.

East of this area lies a large area of limestone mountains, which are broken up into smaller sierras by areas of lowland. The Sierra de Grazalema is the most famous of these limestone karst sierras. To the west it is a seamless continuation with the Alcornocales, but to the east it borders the lowlands of the town of Ronda which separates it from the Sierra de las Nieves . The latter is the highest massif of western Andalucía (as defined by this book). Further east lie the massifs of El Chorro and Torcal de Antequera, which are a continuation of the same belt of limestone. At the southern edge of the mountains are some of Spain’s most famous beach resorts, such as at Málaga, Torremolinos and Marbella.

The Sierra Morena, the central plains and the Sierra Baetica may be geological and ecological unities, they are certainly not separate regions from a touristic perspective. Travelling the Sierra Morena from west

to east is impossible because of the lack of roads. You could do so in the Sierra Baetica, but the endless series of curves and narrow roads is befuddling and time consuming. It is much easier to combine areas of the Sierras with nearby lowlands – and much more rewarding as well, since the diversity of landscapes, flora and fauna is much greater when combining lowland and mountain areas. Hence the routes and sites described from page 133 onwards, are grouped in sections that are more conveniently covered from a single starting point.

Torcal de Antequera (site C on page 224), one of the most impressive karst plateaux in Europe. The limestones of the old seabed rose vertically, leaving a pattern of horizontal layering in the rock, which is creviced vertically due to the erosive and corrosive workings of rain water. The result resembles a pertrified metropole.

did not leave the Sierra Morena entirely unaffected: especially in the eastern part (Sierra de Andújar and Despeñaperros; covered in our guidebook on eastern Andalucía), the mountains rose and the relief became accentuated.

The Sierra Baetica rose from the bottom of a sea, just like the Hercynian plateaux, but this sea had been full of shelled marine life for millions of years. Their remains had been deposited in thick layers on the ocean floor and compressed into limestone. Hence, large parts of the Baetic mountains consist of limestone – a sharp contrast with the Sierra Morena. Nevertheless, the Sierra Baetica has important pockets of sandstone as well, such as in Los Alcornocales and Montes de Málaga.

Limestone is different from sandstone in about every imaginable way. It erodes easily, which is why the calcareous parts of the Sierra Baetica have dramatic cliffs, barren karsts, and deeply indented valleys, but there are also areas with gently rolling hills where the dissolved minerals were later deposited to form deep nutrient-rich soils, excellent for growing crops. Limestone is also very porous: rain easily sinks into the bedrock, leaving the plateaux dry even in areas with a lot of rain. Elsewhere, the water reappears as streams which carry water throughout the year. And perhaps most importantly, the chemical make-up of limestone is very different from acidic soils, and therefore this bedrock sports a very different flora. This corrosive interplay of water (naturally slightly acidic) and limestone (basic) results in some of the world’s most stunning landscapes: karst. Karst plateaux (karst features are usually on plateaux) are extremely

rocky, with many holes and crevices. Within our region, the limestones happen to be in the region with the highest and most torrential rainfall and as a result, the karst landscapes here are among the most dramatic in Europe. Some crevices have eroded so deeply and criss-cross the plateaux so chaotically, it is as if you are walking deep down in a petrified maze. The Torcal de Antequera (site C on page 224) is, in this respect, the most impressive. The corrosion continues underground as the water seeps through the softest limestone layers. Over millions of years, the water has carved out immense cave systems that make the interior of the karst sierras like a Swiss cheese. Many of these underground caves have collapsed, leaving depressions of various sizes, into which water runs down and accumulates. Here, the water finally returns what it has taken away elsewhere. The suspended limestone sinks down to form a thick layer of nutritious soil. These depressions are called dolines when they are small or poljes when they cover several square kilometres. The poljes are so green and lush that they look artificial in the stony surroundings. To an extent they are, because generations of farmers have taken away the stones to take advantage of these relatively scarce patches of fertile soil (Polje comes from the word for field in Serbo-Croatian). Most settlements in the karst sierras are situated near these poljes and dolines.

Hercynian plateaux

Hercynian plateaux

Hercynian plateaux

Hercynian plateaux

With the rise of the Cordillera Baetica (a process which still continues), the landscape of Andalucía changed dramatically. It was no longer a shallow sea at the foot of the Sierra Morena. It became a bay surrounded by mountains – mountains that caught moist oceanic air, causing rainfall which formed rivers that washed down sediments into the bay. These feeder streams deposited so much sediment that the bay gradually filled up leaving at the centre of the basin the mighty Guadalquivir River (Guadalquivir comes from the Arab Al-wadi-al-Kabir – literally the mighty river). This process is ongoing, and has changed the

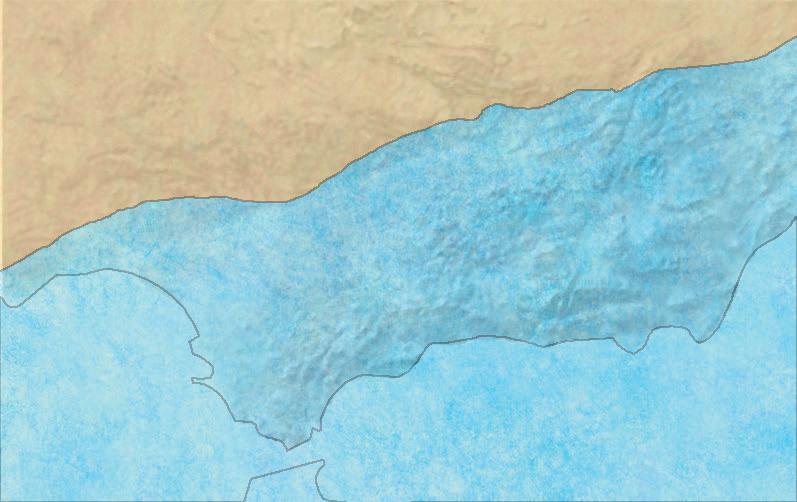

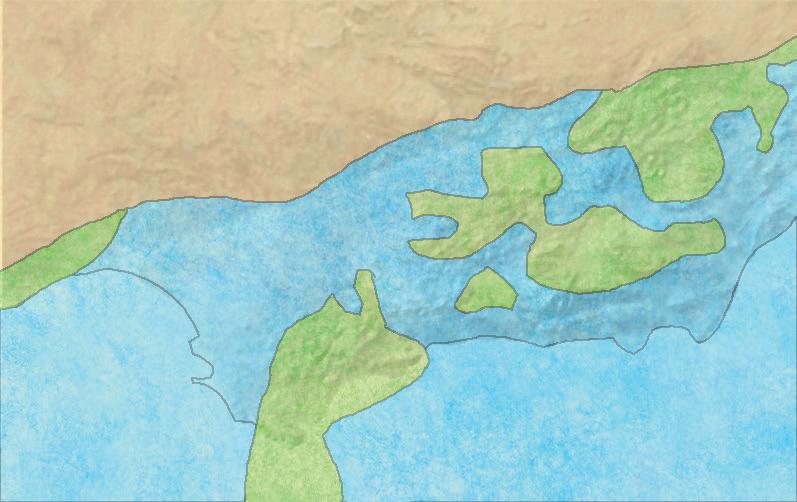

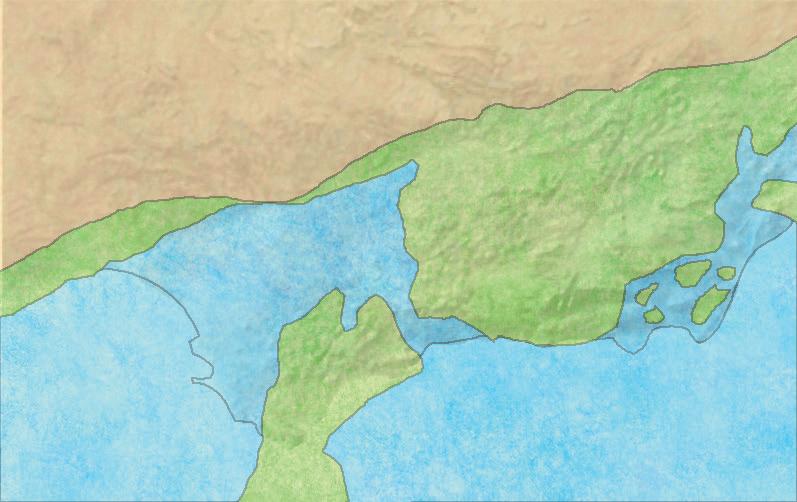

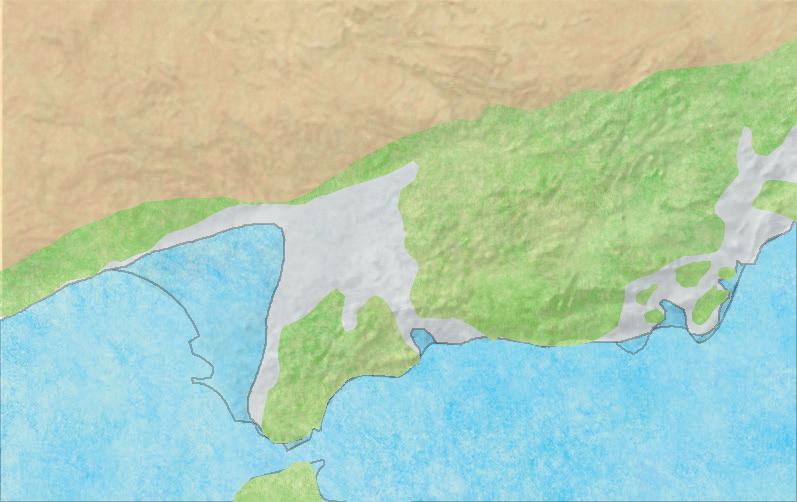

Andalucía at various stages of geological history.

As the sea winds sweep the huge mobile dunes of Doñana inland, they swallow entire pines.

landscape of lowland Andalucía even in historic times. Seville serves as an excellent example: in Moorish times this city bordered a shallow bay in the Atlantic! What is today the Coto Doñana was then still under the sea.

The Guadalquivir basin is gently undulating. Together with the hot and semi-arid climate, this gives rise to, by European standards, an odd geological phenomenon: endorheic lakes. The relatively wet winter months give rise to small streams that pour into depressions, where lakes are then formed. In the dry summer months these streams, as well as the lakes they feed, dry out. Endorheic lakes are isolated, faced with regular drought and conditions of high salinity, making them unique ecosystems (see page 32).

An extraordinary view on the beach of Maneli, near Doñana (route 4). The fossilised dunes (the light substrate), compressed when ancient dunes were submerged by the ocean, are overlain by young sands that are currently being blown over the old dunes.

Most of the Atlantic coast of Andalucía is covered in extensive areas of sand dunes, which culminate in extent and height on the coast of Coto Doñana. Here are some of Europe’s highest sand dunes, some of which overlie escarpments of older, fossilised dunes.

The dunes are a result of the strong westerly currents (and winds), which

Standing at the shore of Tarifa on a clear day, it seems as if you could almost touch the other side. The Straits of Gibraltar are only fourteen kilometres wide at their narrowest point. Africa is so close you can distinguish its fields and houses with the naked eye. From the earliest times this has been a strategic point of utmost importance, but in geological terms it has played an even greater role. It was the site of one of the most dramatic events in the history of the earth.

In 1970, researchers discovered large salt deposits in the seabed off the shores of Sicily. The seabed also contained remains of small crustaceans adapted to the warm, sunny and highly saline conditions found in shallow lagoons. This discovery gave rise to an extraordinary new scientific insight, namely that at some time the Mediterranean Sea must have dried out almost completely in a process of desiccation on an unimaginable scale.

It is calculated that only 10% of the water that evaporates each year in the Mediterranean Sea, is replaced by the rivers that pour into the basin. The rest comes in from the Atlantic Ocean. When the gates of Gibraltar closed, the Mediterranean Sea evaporated almost entirely in a relatively short period of time. This period of desiccation is referred to as the Messinian salinity crisis . The Mediterranean became the stage of a dramatic empty landscape: a vast, thirsty desert with a few large saline lagoons that shrank with each hot, scorching year. Today, such a moonlike landscape can only be found in the Takla Makan desert in western China.

While the water level continued to drop like an emptying bath tub, the coastal regions of France, Greece and Spain were still in a tectonic rise and towered hundreds of metres above the dried-up seabed. Rivers incised deep gorges or dropped into dramatic depths: a landscape of apocalyptic qualities. Scientists differ in their opinions as to what sealed off the Mediterranean Sea from the Atlantic Ocean and ushered the Messinian Salinity Crisis. It was most likely an ice age that caused the ocean’s water level to drop. Exactly opposite of what is threatening us today. Rivers and lakes froze in the north and no longer replenished the ocean. The combination of the falling sea levels and the rise in the land mass (caused by subterranean forces) cut the Mediterranean off from the Atlantic.

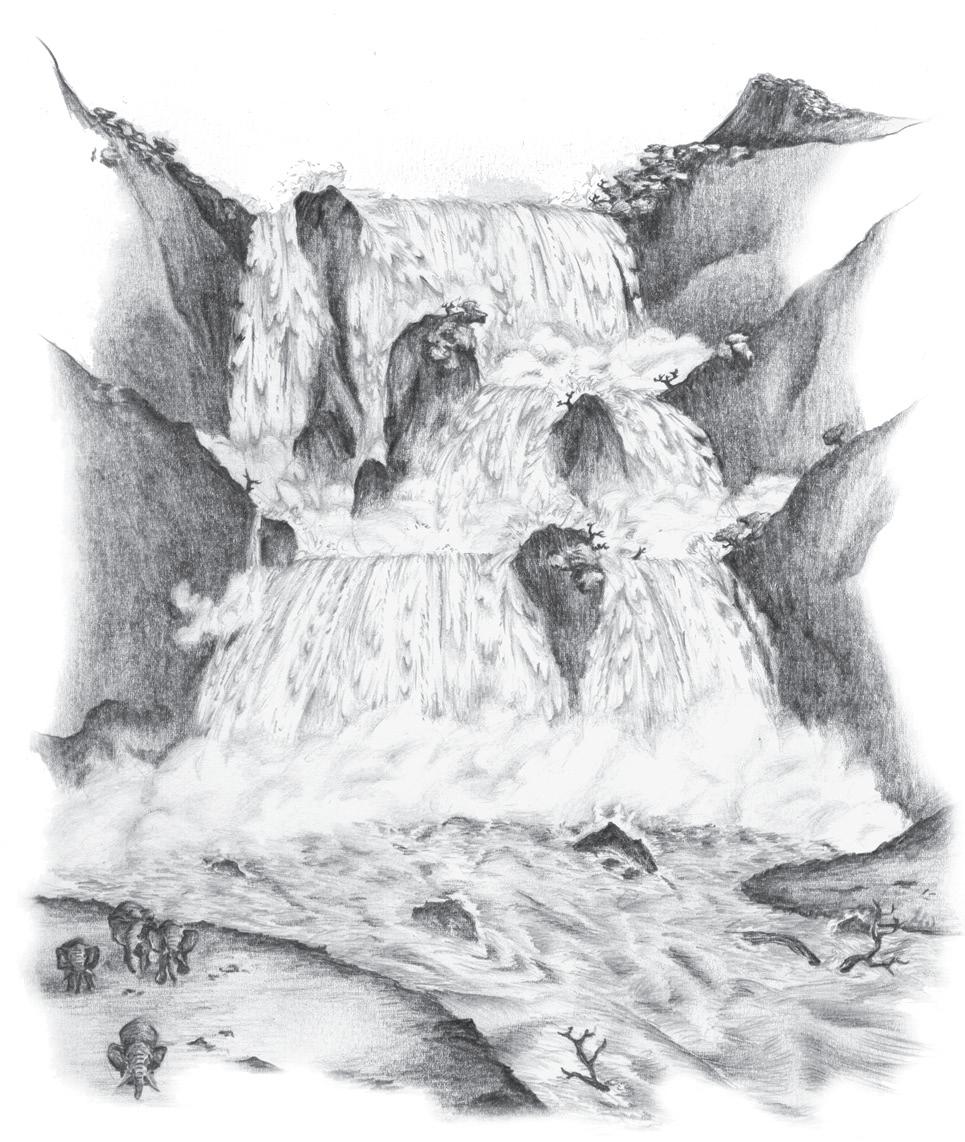

Measured in geological time, the Messinian salinity crisis had an abrupt start, but it ended with a bang – quite literally. A series of earthquakes broke the weakest link of the Baetic Cordillera and the ridge between present-day Gibraltar and Tangier collapsed under the pressure of the Ocean water. Over a length of 15 kilometres a cascade, many times the size of the Niagara Falls, poured into the desert seabed about 300 metres below. It has been estimated that about 65 cubic kilometres(!) of water blasted into the Mediterranean each day through the Gibraltar cascade,

Artist impression of what the ‘Gibraltar Falls’ might have looked like.

filling the entire basin up to its current limits in mere decades. Standing on Europa Point at the tip of Gibraltar today, the sounds of the wind may howl, but just imagine the roar that filled the air if you were to stand there at the end of the salinity crisis.

The chances that somebody actually witnessed the megafalls are very low (although bones of human ancestors found in the Andalucían Sierras precede the date of the Gibraltar catastrophe). However, much later a similar event at the other end of the Mediterranean had a profound impact on both the history and mythology of humankind. The Mediterranean spilled into the Bosphorus and created the present-day Black Sea. This flood is thought by some to be the origin of the biblical story of Noah’s flood.

blow sands into high dunes. The shaping of the current dune landscape started when the seawater levels rose as a result of the warming of the climate following the last ice age. The strong current threw up long sand spits (e.g. the Doñana coast and Punta Umbría south of Huelva). Sheltered from the sea, the rivers slowed and deposited sediments in the bays behind the spits, gradually filling them in to create large areas of marisma salt marsh. Repeated flooding and marine sedimentations fossilised the dunes into a brittle sandstone. Several fault lines (e.g. above Matalascañas (route 1) and near Barbate – route 9) caused the fossilised dunes to emerge as cliffs at the coast – the most prominent of which is the Breña de Barbate. Elsewhere, mobile dunes form enormous and unstoppable ‘tsunamis of sand’, which, swept forth by the wind, rolled inland. In the Doñana National Park and at Bolonia, the massive mobile dunes make for a spectacular landscape.

The whole of western Andalucía has a Mediterranean climate, but one with an Atlantic twist. The summers are, overall, hot and dry and the winters usually cool and quite moist, as is typical for the Mediterranean region. However, the winter cooling is tempered by the western ocean winds.

Together with the Algarve and Almería, the Cádiz coast has the warmest winters in Europe, with the average minimum temperature of over 15° C. Some of the highest summer temperatures of Europe are found in Andalucía as well, but deeper inland, well away from the cooling sea breeze. The Guadalquivir basin between Seville and Córdoba has a more continental type of climate with rather cold winters but some of the hottest summers in the whole of Spain (together with the basins of East Andalucía and Murcia). Ecija, halfway between these two cities, is widely and rightly known as la sartén, the frying pan of Andalucía. Summer daytime temperatures here average over 35° C and are rising with climate change. The prevailing western winds, heavy with water vapour picked up over the ocean, find in the mountains of the Alcornocales and Grazalema their first obstacles. Therefore, the annual rainfall for these mountains is fairly high, in particular in the high Sierra de Grazalema. In fact, with an average of 2200 mm of rain per year, it is the wettest spot in the whole of Spain! This puts it in the same class as England’s wettest region, the Lake District, and so challenges our preconceived ideas of southern Spain. But statistics can be deceiving. The Grazalema soils are not wet. Nearly all rain falls in winter and spring in relatively short, heavy spells. The water seeps right through the cracks in the limestone soil. During the rest of the year, rain is scarce or even absent.

The Sierra de las Nieves (the snowy mountains!) is, with a highpoint of just over 1900 metres, high enough to have a cover of snow in most years (although in keeping with the global climate change, it has snowed considerably less in the last decades).

So all in all, there are four distinct climatic zones in western Andalucía: the relatively cool and precipitous mountains of the Sierra Baetica, the almost subtropical coastal strip with its very mild winters, the more traditional Mediterranean climate of the Sierra Morena and finally, the interior Guadalquivir basin with its continental climate of extremes.

View over the Laguna de Fuente de Piedra, the second-largest natural lake in Spain. It is of vital importance for birds.

water-body that is not part of this great water cycle and whose water will not reach the ocean so directly. Such water-bodies are called endorheic lakes – lakes that have an inflow of water from temporary streams, but no outflow to the sea. The evaporation is simply too strong and the streams that feed these lakes too feeble for these lakes ever to spill out of the depression in which they sit. What remains is an aquatic system that is completely isolated from other water bodies.

Biologically speaking, endorheic lakes are islands. They are isolated from similar habitats. Many aquatic species, fish above all, cannot (naturally) reach these lakes. Without these fish, amphibians and certain kinds of water plants thrive, creating a food chain that is very different from that of other wetlands. In short – the ecosystem of an endorheic lake is unique. The central plain of Andalucía holds quite a number of small endorheic lakes, dotted in the gently rolling tapestry of fields and olive groves. They are especially important for amphibians and pondweeds, plus the birds that feed on these. The rare and threatened White-headed Duck is found mostly on endorheic lakes, and the lakes have important populations of Purple Gallinule, Red-knobbed Coot and Red-crested Pochard. Many endorheic lakes have such a meagre influx of water in winter that they dry out completely during spring. Here the cards are dealt differently again – all the species that occur in these lakes must be able to either flee to other areas (like birds) or to adopt an amphibian lifestyle. Such sites can be teeming with life when conditions are right, or be silent and dormant when dry.

Endorheic lakes can hold fresh or brackish water, depending on the source of the water that feeds them. However, due to the high evaporation, many have become at least slightly brackish, resulting in fringes of saltmarsh, mixed with reeds and bulrushes that root deeper and profit from the periodic inundation in freshwater. This is especially visible in Europe’s largest endorheic lake, the Laguna de Fuente de Piedra (site E on page 226).

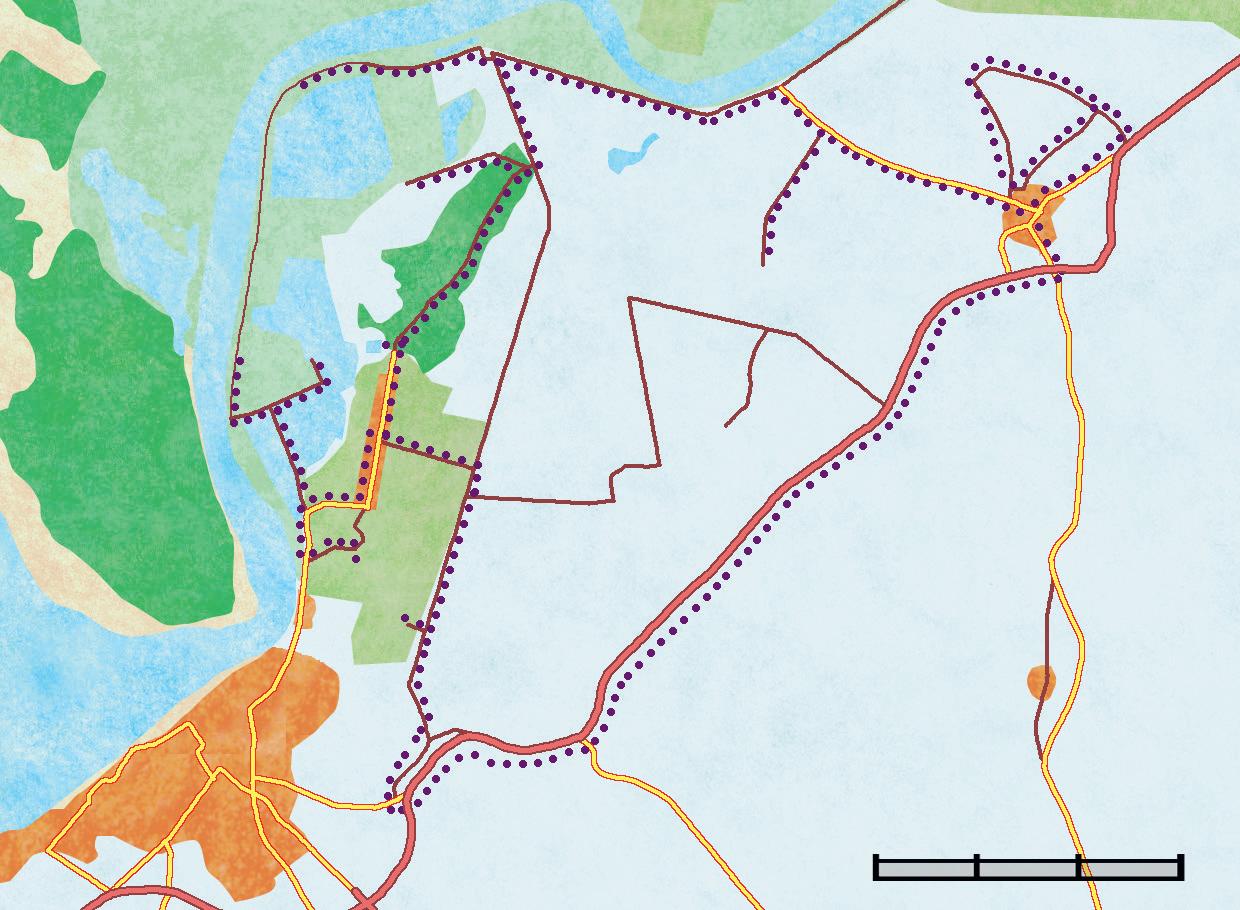

Routes 4 and 5 and the sites on page 160 are situated in the Sierra Morena.

The rolling wooded hills of the Sierra Morena run from the Portuguese border eastwards along the edge of Extremadura and Castilla – La Mancha. Geologically, the Sierra Morena marks the southern extreme of the old, Hercynian plateau that forms the bedrock of central Spain (see geology section; page 16). Hence the natural world of the Sierra Morena shows more similarities with central Spain than with the rest of Andalucía. More specifically, the western Sierra Morena, to which we limit ourselves in this guide, resembles Extremadura. Just like Extremadura, the landscape of the Sierra Morena is dominated by open woodlands of Holm oak. If you drive the N433 from Sevilla to Aracena, you cross a landscape that is best described as endless groves of oak trees. This is a beautiful and inviting scenery in spring as the swards between the trees are full of flowers. In summer and autumn, when the grass turns yellow, it has more the feel of a savannah – an association that is strengthened by the broad canopies of the trees. This is the dehesa, a vegetation that is unique to south-west Iberia. It dominates the lower parts of the Hercynian plateaux, from the Sierra Morena west into Portugal and north into Extremadura and the borders of Castilla Leon and Castilla La Mancha. Dehesas are special in many ways, ecologically and culturally (as we’ll discuss further on in this chapter).

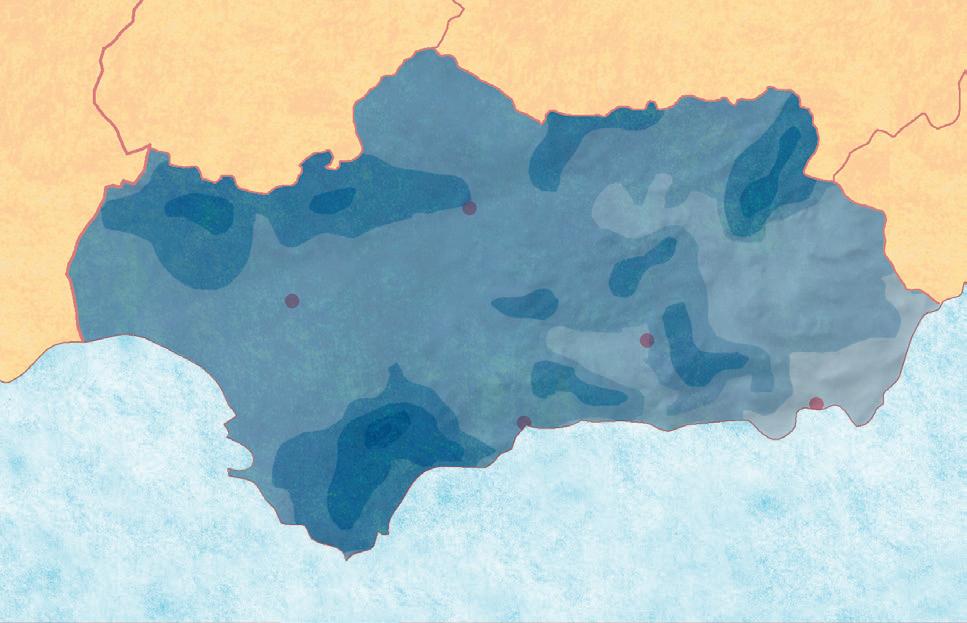

Location of the Sierra Morena (light grey). In dark, the part known as Sierra de Aracena, on which we focus in this guide.

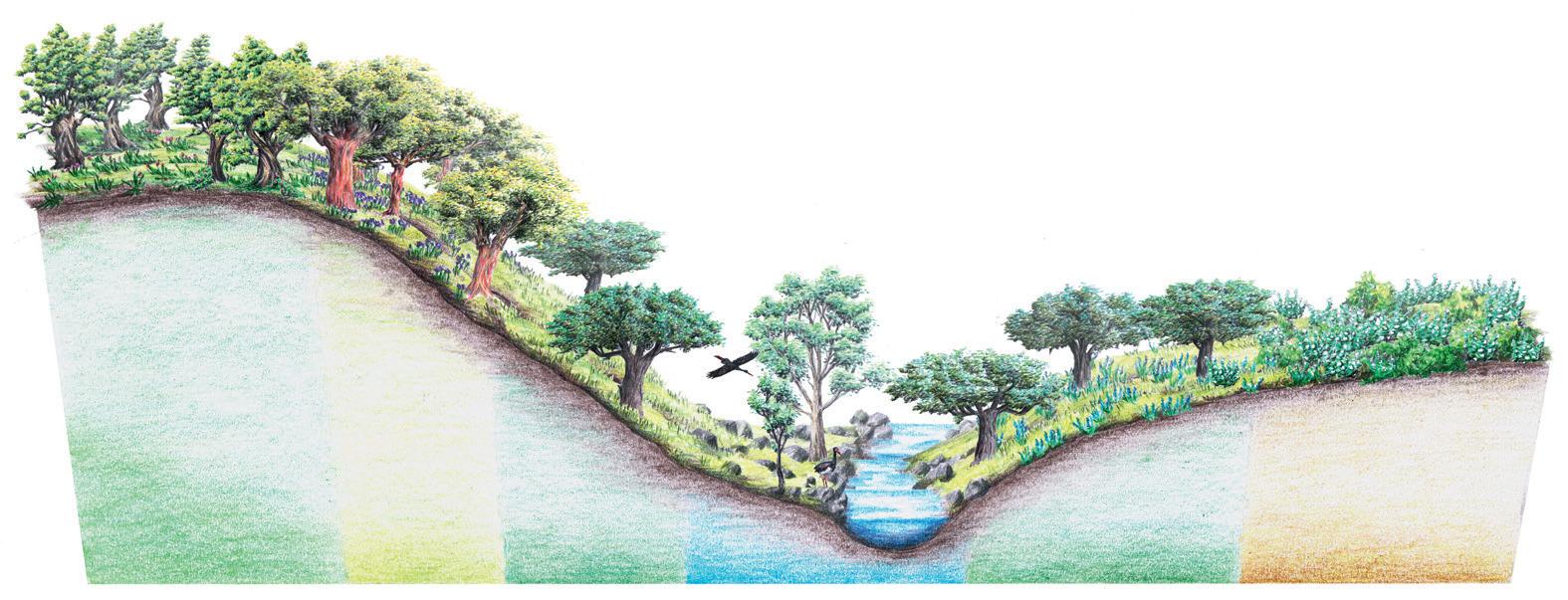

Cross-section

the Sierra Morena.

Dehesa is not the only habitat in the Sierra Morena. In spite of its modest elevation (most peaks are 700-900 metres high) and rolling character (in particular in the western section), the Sierra Morena has an excellent variation of habitats that ranges from the river valley via the dehesa-clad slopes up to the higher peaks where scrublands, chestnut groves and Pyrenean Oak woodlands dominate.

The rivers are green, densely vegetated ribbons in the dehesa-clad hills. Most of them have a seasonal water flow. The current is strong in winter as the rains fall and the water, hardly able to penetrate the bedrock, seeks its way above ground down to the valleys. In summer, the rivers dry out to a series of pools in most places, although the shady conditions in the valleys, together with the occasional groundwater source, maintains standing water throughout the dry season.

The broad rivers at low elevations (like the Chanza; route 5) form a very different kind of habitat from the narrow stream valleys higher up. The first tends to be more open, lined with Narrow-leaved Ash and Elm trees and Tamujo* (Securinega tinctoria), a shrub that is endemic to southwestern Spain. In places where the dehesa reaches all the way down into the valley, the riverbanks are open and grassy. Enriched by sediments, they support a much richer flora than the dry slopes. The rivers themselves are clean, with lots of fish, reptiles and amphibians. Spanish Terrapins are quite common, often basking on a rock (or on one another) amidst a thick bed of Water Crow’s-foot – a wonderful spring image of the Sierra Morena. The small and harmless Viperine Snakes are frequent too, hunting for the many tadpoles and frogs. The abundance of food attracts many birds. The dehesa birds (see page 108) join the Iberian Green Woodpeckers, Golden Orioles and Cetti’s Warblers

that live in the riparian vegetation. The brooks higher up in the mountains are clad in a thick vegetation of Alders, Narrow-leaved Ash and Strawberry Trees. These streams are shady and cool and support a flora and fauna that is much more similar to that of northern Europe.

The dehesa covers the largest areas in the Sierra Morena. It is the realm of Short-toed and Booted Eagle, of Black and Griffon Vulture, of Thekla’s Lark and Azure-winged Magpie, of Hoopoe and Bee-eater. It is, in short, a bird paradise. Dehesas are somewhere between a forest, a scrubland and a grassland and combines characteristics of all of these. This becomes clear when you look more closely at the birdlife. In the denser dehesas, especially those with Cork Oaks, you’ll find forest birds like Chaffinch, Nuthatch and Short-toed Treecreeper. Others parts are so open that steppe birds like Calandra Lark finds a home. In rocky places, there are Black-eared Wheatears and Rock Sparrows, while Woodchat and Iberian Grey Shrikes and Dartford and Sardinian Warblers enjoy the scrubby sections. Anyone who visits the dehesa in spring will be impressed by the amount of wildflowers, particularly after a rainy winter. Keep your eye fixed on the grasslands some 50 metres ahead of you and you’ll see more pink, purple, white and yellow than there is green. There are not many habitats in the world with such a profusion of flowers. However, look at the turf right around your feet and you’ll notice that the sea of wildflowers disintegrates into a scatter of flowers and between it is bare soil that is so poor it is not able to sustain a denser vegetation.

Rio Múrtigas near Encinasola with mats of Water Crow’s-foot in the shallow borders.

The dehesa is an agricultural landscape and it is born out of necessity. Intensive crop growth, like the fields and olive groves you find everywhere in the Guadalquivir basin, is not possible in the Sierra Morena. The dehesa

Natural free-ranging pigs in the dehesa. The Ibérico pig is the cornerstone of the dehesa agricultural system.

is the best possible agricultural system for these poor soils. It offers grazing ground for sheep and pannage for pigs, while the trees preserve the soil against desiccation and erosion during the strong winter rains. The trees also provide wood, cork, fodder, branches for making charcoal and, above all, acorns to feed the pigs (with holm oaks offering the best acorns). Every once in so many years, cereals are planted to harvest some crops as well, after which the soil is left to recover.

One of the typical dehesa products is the Jamón Ibérico, the famous and much praised hams. The Sierra de Aracena (the western part of the Sierra Morena that we focus on in this book) has a fine tradition of pig rearing and production of jamon.

Dehesas come in a Holm Oak and Cork Oak variant. Although there is great overlap in the natural range of these trees, they are seldom mixed within a single dehesa. As a rule of thumb, cork oak dehesas are found on richer and damper soils than the holm oak stands. In the Sierra Morena, cork oak dehesas are generally found at higher elevations because of the damper conditions. However, cork oak stands are also found at sea level near Coto Doñana, but here the soils are different.

The Iberian ham (Jamón Ibérico) is the most typical product of the dehesa. It is world-wide famous as a delicacy and something the locals are deservedly proud of. One of the main centres of Jamon production is the Sierra de Aracena, in particular the town of Jabugo. To some meat lovers this town is the mecca of ham. The high quality hams are expensive, even in the region itself. This is a direct result of the process of fabrication: the local race of pigs (the black-skinned Ibérico swine) is a free-ranging pig that is held in low numbers in the dehesa and feeds on the acorns of the Holm Oaks. After the slaughter, the leg is salted and hung to dry for 1½ years before it is ready to consume. But then you have an exquisite product, which is locally sold as Jamón Ibérico de Bellota (de bellota meaning fed on acorns). This is the best and most expensive of them all (Similarly good is the paleta – the fore leg). It is also a product that supports the maintenance of the dehesa, so is the most organic, nature-friendly local meat that you can have. However, there are a range of other jamones on the market, which are cheaper.

A step down the ladder is the Jamón Ibérico de cebo, which comes from the same free-ranging Ibérico pig, but this time fed on maize, wheat and whatever is available. The Ibérico ham, by the way, is what abroad is sometimes called Pata Negra – black foot, referring to the skin of the Ibérico pigs. It is not a term that is used much in Spain.

Much cheaper is the Jamón Blanco, which comes from ‘pink’ pigs. As this meat can be salted and dried in the same way as the Ibérico ham, it looks the same, but the taste is different. Also, as these are not free-ranging pigs, the texture is different too. This ham is sold as Jamón Serrano, dried ham.

The Ibérico products are not limited to Jamón. There are wonderful chorizos, dried sausage (Salchichon ) and loins (lomo) as well.

This traditional system of land use, combining crop growing, grazing and forestry within the same area is unique. It is centuries old, boasts a wonderful biodiversity and has withstood the agricultural revolution of the 20th century (which has put so many nature-rich agricultural landscapes in Europe under such severe strain) relatively well, although there are problems with overgrazing and the abandonment of the land. In particular a fungal infestation that kills the trees, known as La Seca (the drought), is considered a major threat in the long term to the dehesa of the Sierra Morena.

In some parts of the Sierra Morena, the dehesa was cleared during the Franco days to make way for Eucalyptus or pine plantations. Such stands are monotonous and ecologically virtually dead.

Ancient chestnut groves dominate the higher hills in the Sierra de Aracena. At present, the chestnut culture is experiencing hard times as the profits are too low to maintain the groves.

Roughly above 600 metres, the cork oak stands gradually give way to another type of oak: the Pyrenean Oak. Unlike the Cork and Holm Oak with their small and leathery leaves, the Pyrenean Oak has large and deeply lobed leaves which are shed in winter. Also in posture it is much more like the oaks of temperate Europe.

Pyrenean oak woods are now very rare in the Sierra Morena, particularly in the western section, as many have been replaced by chestnut groves. The chestnut groves are a typical feature of the Sierra de Aracena, where the largest chestnut woods of Spain are found. The village of Castaño del Robledo is even named after the chestnut (castaño) as it is surrounded by so many chestnut groves (route 6).

Thick in girth but low in height, the Sweet Chestnuts stand like squat giants on the high hillslopes. The chestnut culture is an ancient one, as are the groves themselves. On average, the trees are between 300 and 400 years old! In particular in October and November, when the leaves turn yellow and the chestnuts fall, they are beautiful.

The chestnut groves are under serious threat – the harvest of chestnuts has declined enormously and the market price for chestnuts is very low. The revenues from other traditional products from the groves (wood, charcoal, grazing pigs) is insufficient to cover the high costs of collecting the chestnuts and maintenance of the trees. Almost 50% of the groves are either neglected or abandoned.

The chestnut zone is like a cool island above the hot low hills of the Sierra de Aracena – a wonderful place for walks. The flora and fauna are different as well. The birdlife has a decidedly temperateEuropean slant to it. Lesser Spotted Woodpecker and Redstart are common birds, as are the more widespread forest birds like tits, finches, Nuthatches and Short-toed Treecreepers. Botanically, the groves are quite attractive, with large stands of the pretty Western Peony as their most typical hallmark.

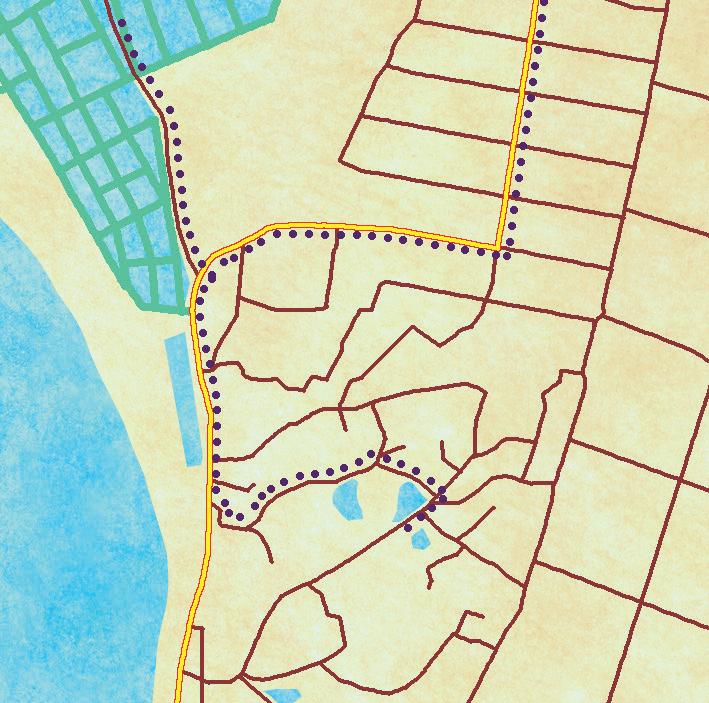

Routes 10 to 12 and the sites A to E on pages 192-195 lead through the sandstone mountains in and around Los Alcornocales. The prettiest canutos feature on route 11 and 12 and sites A, B and C. Cork oak woods feature on all these sites and routes, but the dense woodlands of Algerian Oak are best on route 12. The most attractive heathland and low scrub is found on route 11 and on the peaks of Aljibe – El Picacho (site A).

The sandstone mountains and loamy hills of Los Alcornocales and bordering Campo de Gibraltar provide a wonderful, leafy wilderness that is unexpected this far south in Spain. Lush river valleys (locally called canutos) cut deep into the surrounding hills, which are covered in dense forests that blend into open cork oak woods and scrubland on the exposed slopes with shallow soils. The rockiest crests and recently burnt areas are reserved for an open mountain heathland that, like the canutos, is one of the area’s specialities.

A stroll through the Alcornocales is a thoroughly pleasant experience. Along the rivers and in the woodlands you will find a large variety of wildflowers, while from up in the canopy you are greeted by the songs of Golden Oriole, Bonelli’s Warbler, Blackcap and Iberian Chiffchaff. It is also a great area to hang out on warm summer days, when the shade and water bring the essential coolness and a large number of southern dragonflies buzz along the streams (the Alcornocales form a dragonfly hotspot). Large,

After Franco died in 1975, nothing stood in the way of a liberal democracy. Spain joined the EU in 1986. From that time on, agriculture and nature conservation policies were dictated by the EU’s capricious laws, which are as often brilliant as they are counter-intuitive, contra-productive, contradictory or downright destructive. Huge areas of West Andalucía’s mountains and pretty much all wetlands were put under protection as Important Bird Area (IBA) and / or Natura 2000 site. One example is the dehesa landscape of the Sierra Morena, whose ecological value was formally recognised for the first time, thanks to European law. That same law became one of the first real threats to this ecosystem. New hygiene rules made traditional pig rearing difficult, while the prohibition of leaving dead cattle in the field (due to fears surrounding BSE – mad cow disease) threatened many of the region’s raptors with starvation. Modernised and subsidised agriculture threatens the birdlife of the fields and grasslands and the subsidised improvement of the road network pose new threats to mammals like the Iberian Lynx.

Parallel to these developments, an enormous interest is flowering among the Spanish in exploring their own region. Few places in Europe saw such an increase in local hiking clubs exploring new trails, while, judging from the many school classes on mountain trails, nature education takes a prominent role in the school curriculum. Grass-root initiatives to preserve or even restore habitats are plentiful while reintroduction programs for Iberian Lynx, Osprey, Spanish Imperial Eagle and Bald Ibis indicate a great awareness of the importance to preserve the Spanish natural heritage.

After Franco’s death, Spain rapidly put large swathes of land under protection. The Parque Natural de Sierra de Grazalema was established in 1977, Torcal de Antequera followed in 1978 and Laguna de Fuente de la Piedra in 1983. The year 1989 was an important year for the Parques Naturales – Bahía de Cádiz, Marismas del Odiel, Coto Doñana, Laguna Medina, Los Alcornocales, Sierra de las Nieves and Breña de Barbate all became either Parajes (protected landscapes) or Parques Naturales (nature parks) in that year.

In the first decade of the 21st century, many of endorheic lagoons became protected sites and the Parque Natural del Estrecho was established. Most

became Natura 2000 sites and the marshlands were designated Ramsar sites. The paper protection for most sites was in order. In its nature conservation, Spain adopted the ‘soft approach’, in which nature parks (with the exception of the Coto Doñana National Park) serve both the goals of nature conservation and the local economic development, based on green tourism and the branding of local and organic food. Andalucía was the first and most ardent autonomous region in Spain in adopting this strategy of conservation. Twenty-two parques naturales were created, many of which covered huge areas of which the overwhelming percentage of land was privately owned. In practice, very little changed in these areas in the daily routine of land use. However, the inclusion in the Natura 2000 network, plus the implementation of specific species recovery and habitat restoration plans do help to improve the natural areas. Furthermore, nature tourism (both national and international) has increased tremendously and does indeed put economic value to these areas besides the agricultural gain. Perhaps even more important, the increased interest in nature has led to a re-evaluation of the beauty and the ecological and historical value of these areas, both among the locals and the city folk who come to visit. The increase in hiking clubs, wikiloc trails (see page 241) and birders are testimony to this.

Notwithstanding all the conservation efforts and reintroductions, Andalucía’s natural areas face some serious conservation challenges. Many of them are directly or indirectly related to modern agriculture, tourism and climate change.

Both agriculture and mass tourism use up huge amounts of water. Since the 1990s, Spain has the greatest per capita water consumption in Europe. Much of this, particularly in Andalucía, is due to high levels of consumption by agriculture and tourism. The marismas and endorheic lakes are fed by rainwater, but the Lucíos and lagoons near Matalascañas, so important for being the only permanent wetlands in the area, are influenced by groundwater, which is depleted by heavy extraction for tourism and agriculture. The Huelva coast has become an important region for growing strawberries under plastic. The climate is ideal for producing strawberries early in the season. However, this crop consumes large amounts of water. Worse is the extraordinarily high consumption by golf courses which are watered permanently to keep the greens green. Often constructed at the expense of valuable dune systems and other coastal sites, golf courses can be considered the epitome of wasteful decadence and mindless destruction.

Over the last decades, various iconic species have been reintroduced in western Andalucía.

Osprey Sporadic breeding attempts, often on inland reservoirs, helped to prompt a reintroduction programme between 2003 – 2009, when young birds were released in Huelva (56) and Embalse de Barbate (73), where, by 2013, respectively 3 and 4 pairs were breeding.

Bald Ibis The historical status of this bird in Spain is obscure, but, under the name Cuervo Calvo (Bald Raven), it was last reported in 1616. The last viable wild population of this species in the world is in Morocco where 600 individuals remain. They breed well in captivity, so from 2003 onwards birds from Zoobotánico de Jeréz were reintroduced to the La Janda area. By 2014 two colonies had a total of 24 pairs and 78 free-flying birds.

Spanish Imperial Eagle Between 2002 and 2010 a total of 73 young eagles were released near La Janda, an established wintering site for the species. In 2010 a pair bred nearby for the first time in 50 years. Despite a high death rate (mainly from electrocution) a small population seems to be establishing itself.

Iberian Lynx By 2008 only two viable populations of Iberian Lynx remained – one in Doñana (24 – 33 adults) and the other in the Sierra de Andújar (67 -190 adults). By 2014 however, intensive conservation work has raised the total to 327 individuals and 50 captive-bred lynx have been reintroduced to the Sierra Morena and Montes de Toledo in Castilla–La Mancha, the Matachel Valley (Extremadura) and Guadiana Valley in Portugal. Large recovery projects for Iberian Lynx (here near Mazagon –route 4) seem to have saved this gracious feline from the gates of hell. The Iberian Lynx is still the rarest cat of the world.

Intensification of agricultural practises – the ‘green revolution’ that has destroyed so much of the beautiful and nature-rich countryside in western Europe – has left the mountains of western Andalucía relatively unscathed. The dehesa landscape, the karst plateaux and cork oak forests are not so easy to ‘improve’ (the term that is often used for the practises that boast the agricultural production at the expense of the natural world). The trees, often regarded as inimical to intensive agriculture, are vital for the preservation of the soil, which by nature retains water poorly. However, the products linked with the extensive use of the dehesas and

scrublands – wool, sheep meat, sheep and goat’s cheeses, honey, cork, wood, ham – are expensive to produce in comparison to the industrial meat production and intensive agricultural practises. Fortunately, there is a renewed interest in and appreciation of the original productos del campo, which taste so much better and are uniquely tied to the landscape. A worrying new use of the land is for wind turbines and solar panels. Spain, like many European countries, has developed the production of energy from wind and sun – two sources that are readily available in large parts of western Andalucía. This is a particularly thorny issue, as it is of pivotal importance that we change our energy use, making it hard to criticise the increase of renewable energy production (especially for tourists – be honest, did you arrive in Andalucía by carbon-neutral means?). However, there is no debate that wind and solar parks can have disastrous effects on the flora and fauna, not to mention the scenery. The windiest parts of the region happen to be the lowlands near Tarifa – right in the middle of the busiest stretch of the west European flyway of migratory birds. Evidence suggests the exact siting of turbines can be critical with most of the individuals being killed by a relatively small number of turbines. With this in mind wind farm companies employ observers (especially August – December) to alert control centres when flocks of birds (or even individual rare birds like Spanish Imperial Eagle) approach so turbines with the highest mortality rates can be shut down, thus reducing the risk of bird fatalities. Studies have been done on the effect on bats, which do not have the advantage of intermittent shut downs, with worrying results. At the time of writing several large wind farms off the Cádiz coast are being planned, the impact of which on birds and cetaceans remains uncertain.

Wind turbines in the coastal zone of Tarifa, right beneath the main migration flyway. This is a thorny issue – of course the transition to renewable energy is of vital importance to fight climate change, while at the same time, they have an adverse effect on migrating birds.

Naturally, species diversity is not evenly distributed across the world, but, generally, increases with higher temperature and moisture. Biodiversity hotspot is the technical term for an area with an exceptionally high number of plant and animal species. The tropical rainforests (warm and moist) are world famous for being natural treasure troves. Yet only few people know that the Mediterranean basin is also among the world’s biodiversity hotspots as well.

Within the Mediterranean region there are again specific areas that are much richer than others. Amongst the 10 Mediterranean biodiversity hotspots is the Sierra Baetica (the range that extends north-west from Cádiz to Valencia) of which roughly a third lies in our area. It is literally the top of the tops. Hence, the flora and fauna of western Andalucía is hugely diverse. The number of species far exceeds that of any similarsized area north of the Alps.

Much of this richness comes from its endemics – plants and animals that are confined to just a small area, be it the whole of the Iberian Peninsula or a smaller part like the Sierra Baetica. There are even some that are confined to a still smaller patch. Some plants are found exclusively in the Sierra de Grazalema. Obviously, such species have a special appeal. To understand the why behind this uneven distribution of plant and animal species, you need to look back into the past. When the Iberian tectonic plate got sandwiched between the much larger African and Eurasian land masses, the Pyrenees were formed in the north and the Rif-Baetic chain was pushed up in the south. These east-west oriented mountain chains became, quite literally, hurdles for the flora and fauna as species migrated north and south to the rhythm of the advancing and retreating ice.

During the warm interglacials, cold-adapted species found refuge high up in the mountains, where isolated from northern populations, they evolved into new species.

While the mountains acted as a refuge for cold-loving species, the warmthloving ones found them a formidable, or even impassable, barrier. For some species (e.g. lizards like the Large Psammodromus) the Pyrenees are such a barrier, confining them within the Iberian Peninsula. Yet others, such as the Spanish Psammodromus, found a way into France, but ground to a halt when faced with impassable barriers in the Alps and an inhospitable northern climate.

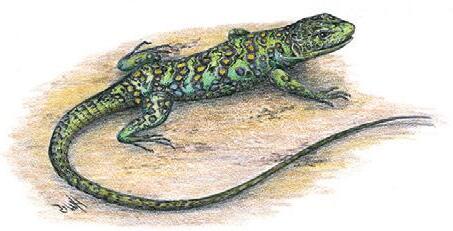

The Common Chameleon was most probably introduced by the Moors and has established several populations on the warm west coast.

It may come as a surprise, but the Strait of Gibraltar, dividing Europe and Africa, is not nearly such a barrier as the mountains. Many plants and animals of Andalucía are shared with the Moroccan Rif mountains. As these ranges are geologically one and the barrier of the Straits is a relatively young, populations of such species separated fairly recently. Add to this the fact that the climate of coastal Andalucía and coastal Morocco is similar and the distance between both coasts is not that great, then it is logical that there are strong resemblances between these regions. Examples of such Ibero-African endemics (as they are called) are Lorquin’s Blue, Atlantic Orchid and Green-flowered Narcissus. The term Ibero-African is a little deceptive here as many of the species given this label (most notably the plants) do not occur widely in either region, but are instead endemic to limited areas in both the Sierra Baetica in Iberia and in northern Morocco.

The Andalucían coast has also been ‘invaded’ by more widespread African species coming from much further south. These are invariably excellent flyers, such as dragonflies (e.g. Violet and Orange-winged Dropwings and Northern Banded Groundling are African species) and birds like Little and White-rumped Swifts.

Some of these African species clearly benefit from the very mild winter temperatures. The lowlands of western Andalucía stand out in Europe for having exceptionally benign winters. The Atlantic winds are to thank for this. This climate is peculiar enough to boast its own ecological ‘province’ – the Lusitanian region, which covers the lowlands roughly south of a line between Lisbon and Málaga. Examples of typical Lusitanian species are Portuguese Squill and Portuguese Sundew.

The climate also creates a haven for a final curiosity of the flora and fauna of western Andalucía: relicts of the Tertiary era. The Tertiary was the period preceding the ice ages. The climate in the Mediterranean basin was moist and subtropical – a climate that persists in our times only on Madeira and the Canary Islands (which are therefore living museums of the nature and wildlife of the Tertiary). However, secluded and moist valleys in West Andalucía (above all the canutos of the Alcornocales) have a somewhat similar climate and so boast a number of Tertiary species. Most of them are tree and rock dwelling fern species, which give these sites their brilliant ‘jungle feel’. These permanently moist and mild sites have become post-ice age refuges for some temperate European species too.

Paradoxically, you could see a north-European Roe Deer munching away on ferns which have their main distribution in the cloud forests of the Canary Islands!

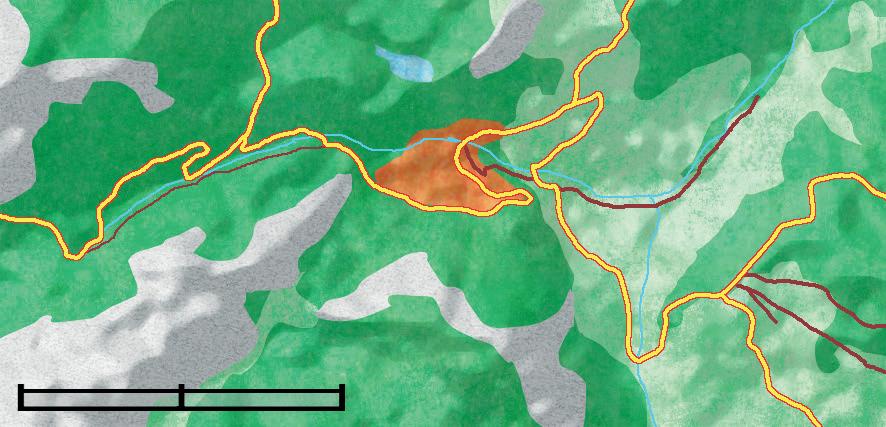

Main biogeographical regions in western Andalucía

Lusitanian region

e.g. Portuguese Squill (Scilla peruviana)

(West)-Mediterranean region

e.g. Ocellated Lizard (Timon lepidus)

Ibero-African region

e.g. Lorquin’s Blue (Cupido lorquinii)

West Mediterranean region

Andalucía

Ibero-African region

Relict species or recent colonists from other biogeographical regions

Macaronesian species (Madeira, Canary Islands)

e.g. Hare’s-foot Fern (Davallia canariensis)

Recent African colonists

e.g. White-rumped Swift (Apus caffer)

Temperate region species

e.g. Roe Deer (Capreolus capreolus)

In contrast its relative, the Autumn Lady’s-tresses is quite common in woods in the lowlands in late September and October.

This leaves spring for all the other species of orchids. As with the rest of the flora, limestone boasts a very different orchid flora than the neutral and acidic soil types.

On limestone soils (i.e. Sierra de Grazalema, Las Nieves, Torcal and the coastal sierras east of Marbella), the most numerous spring species are the Spanish Early-purple Orchid (mostly in woodlands) Man and Nakedman Orchid and various species of the bee orchid genus (Ophrys). The most widespread of these is the Yellow Bee Orchid (p. 207). It grows commonly in roadsides, in karst areas and open patches in scrubland. It is frequently joined by the Mirror Orchid, which sports a shiny, bright blue lip lined with a brown hairy ‘beard’. Much rarer is the Lusitanian Mirror Orchid (O. lusitanica), which has a reddish ‘beard’ and a more rounded lip. Sombre Bee, Spanish Omega (the latter recognisable by the white omega sign on the lip) and Woodcock Orchids are frequent too. Less numerous but widespread (also away from limestone soils) is the Sawfly Orchid, which grows in grassy places. It sports hot pink petals and has the largest flowers of the Ophrys species in the area. It looks superficially like the Bee Orchid, which is quite common in the Alcornocales and Grazalema. In grasslands not far from the coast, the small Bumblebee Orchid (p. 187) can form large populations. It is most common in the grassy areas in the Campo de Gibraltar and Alcornocales, but occurs in the karst landscape of the Grazalema as well. The highlight of the region is the very rare Atlantic orchid, with its untypical, saddle-shaped lip. It is a species proper to the North-African Rif mountains, but grows in a few isolated spots in the Sierra de Míjas, Sierra Bermeja and Sierra de las Nieves.

Los Alcornocales is a good area for orchids as well. Apart from the afore-mentioned Bee, Bumblebee and Sawfly Orchids, the cork oak woods are brightened by the purple spikes of Lange’s Orchid. It often grows alongside Tremols’ and Long-leaved Helleborine and the parasitic Violet Bird’s-nest, looking very much like a stout, purple asparagus until it opens its showy flowers. In moist areas in scrubland and grassland, you may encounter Looseflowered, Champagne and Heart-lipped and Common Tongue Orchids (the Small-flowered Tongue Orchid tends to grow on drier places). Moving into the lowlands of Cádiz and the Guadalquivir basin, the number and diversity of orchids drops rapidly. Only the more widespread ones like Sawfly, Yellow Bee, Woodcock and Mirror Orchids can still be found here and there in scrublands. In the lowlands they flower earlier in the year, not infrequently starting to bloom already in the final days of February. The hills of the Sierra Morena are richer, although the uniform and acidic soils are no match to the splendour of the Sierra Baetica. Nevertheless, it is well possible to see good numbers of Tongue and Champagne Orchids (again in wet spots) and Sawfly Orchid (on the richer soils). Heading into the more shady parts of the hills you should be able to find Violet Bird’snest Orchid, Narrow-leaved Helleborine and Dense-flowered Orchid, plus two species that are rare or absent elsewhere: the first is the yellowflowered Sicilian Orchid (Dacthyloriza markusii ) – one of only two representatives of the Dactylorhiza -orchids which are so common in northern Europe. The second is the small Conical Orchid. Look for these in the cork oak dehesas and chestnut forests in the higher parts of the Sierra. Apart from the above, there are a number of other species which occur uncommonly in western Andalucía. On our website you can download a checklist of all the orchids of Andalucía.

Good numbers of bee orchids (Ophrys) occur in the Sierra Baetica. From left to right:

Sawfly Orchid –widespread though usually in low numbers throughout the mountains.

Bee Orchid – locally very common, particularly in roadsides in the Alcornocales.

Mirror Orchid –locally common in grassy patches in light woodland on limestone (together with Yellow Bee; page 207).

Sombre Bee Orchid – locally common in grassy patches in the limestone mountains.

Spanish Omega Orchid – as Sombre Bee but generally less common and more localised.

Western Andalucía holds the only European population of Little Swift (top) and has a large population of Bonelli’s Eagle (bottom).

Lesser Kestrel Some of Spain’s largest colonies of this beautiful and scarce species are found here.

Bonelli’s Eagle Western Andalucía holds Europe’s largest population of this rare species.

Spanish Imperial Eagle

The region covered by this book holds around 45 pairs of this rare raptor. It is endemic to the Iberian Peninsula.

Azure-winged Magpie

The region holds a fairly large population of this local, beautiful and sought-after endemic.

Marbled Duck Andalucía holds most of the European population of this rare and threatened bird.

Red-knobbed Coot This is a widespread bird in sub-Saharan Africa, but in Europe it only occurs here and in a few other sites in Spain. It is in sharp decline.

Little and White-rumped Swifts These two swifts are recently arrivals from Africa. Little is restricted to Western Andalucía (mainly in Chipiona). White-rumped is more widely, if thinly, spread and reaches Extremadura and Portugal. White-headed Duck Western Aldanulcia holds a fairly large population of this rare and threatened bird.

Raptor passage There are tens of thousands of migrating Griffon Vultures, Egyptian Vultures, Honey Buzzards, Black Kites, Booted and Short-toed Eagles.

Steppe birds Small but significant numbers of Great and Little Bustard, Black-bellied and Pin-tailed Sandgrouse, Collared Pratincole and Black-winged Kite are found in Western Andalucía. Audouin’s Gull This rare and endemic gull of the Mediterranean basin is common near Tarifa.

Flamingos Europe’s second-largest Greater Flamingo colony breeds in the region.

common, but they are there and can be tracked down with some dedication and a bit of luck.

Because of the short distance to Africa, the region acts as a major bottleneck of migration on the western flyway – one of the two busiest routes for migratory birds. Hence, western Andalucía, more specifically the area between Gibraltar in the east and Coto Doñana in the west, is among the very best areas for watching migratory birds. In autumn, it is quite common to see wheeling ‘kettles’ of raptors and storks gaining altitude for the big crossing southwards (in spring northbound birds tend to arrive in fewer

numbers and at a much lower elevation, but on a broader front). Patches of scrub and woodland at the coast are full with songbirds, waiting for the best moment to make the leap down to Africa (in autumn) or are recovering from the breezy trip over the sea (in spring). The marismas of the Doñana are full of northern waders, while the Guadalquivir acts as a busy ‘route du soleil’ for terns, gulls and waterfowl.

Winter is, for birdwatchers, not such a rewarding time, but even this is relative and while fellow enthusiasts are freezing further north, the daytime temperatures can make you feel smugly warm! With its mild winter climate and access to plenty of food in the woods, fields and dehesas, western Andalucía is hugely important for wintering birds. The paramount importance of Coto Doñana as a wintering area for waterfowl is rather evident, but the dehesas and olive groves attract masses of northern birds as well, in particular finches, thrushes, Chiffchaffs, Blackcaps, pigeons and Cranes. Rocky terrain even houses a few birds of the high mountains in winter, such as Alpine Accentor. A small but growing number of migrant raptors – Lesser Kestrel, Black Kite, Booted and Short-toed Eagle – remain in winter as do larger numbers of White Stork. In all, around 400 species of bird have been recorded in western Andalucía of which a little under 50% breed (some irregularly or in very small numbers), with another 90 odd turning up fairly regularly as migrants or as winter visitors. Raptors pass through in the tens of thousands as do uncountable numbers of smaller migrants. So brace yourself for some serious birding! On page 244 there is a bird list with the best sites and routes for each species. Here we go deeper into the birdlife of the different areas of western Andalucía.

Master in disguise during the day, the Red-necked Nightjar is best observed at dusk. In open pine and oak woods with some shrubs, they can be numerous. From late April, listen for the typical ka-TOK, ka-TOK call.

About 136 species of birds breed in the Coto Doñana National Park on a regular basis. Many more visit, either as a wintering species or as a passing migrant, as the Coto is conveniently close to the migration route over the Strait of Gibraltar to West Africa.

It is during these periods of migration that birdlife is at its most diverse, although in terms of numbers, winter beats all other seasons.

The annual winter census in Doñana has more than once exceeded the 1.2 million mark. The birds are drawn to the area for the food: the marshes (and rice fields) offer enormous amounts of roots, grain, bulbs, mosquitofish and macro-invertebrates (the larger species of insects, shrimp, mollusks, etc).

Many ducks winter in Doñana, mostly belonging to the familiar species that are found across western Europe, like Wigeon, Teal, Mallard, Shoveler and Pintail. Among them are a varying number of Mediterranean species like White-headed Duck (variable, averaging 250) and smaller numbers of Marbled Duck (<50). About 70,000 Greylag Geese gorge themselves on the Sea Club-rush roots each winter. This may not be as impressive to the visitor from northern Europe, but their dining habits are. The geese eat sand after their banquet in order to grind the hard and otherwise indigestible roots. Stumbling upon a group of geese gobbling up sand in the middle of the desert-like sand dunes is one of the stranger birdwatching experiences of the Doñana. Other wintering birds include tens of thousands of Greater Flamingos, Coots and waders like Avocet, Lapwing, Redshank, Black-tailed Godwit, Little Stint, Dunlin and Snipe, plus Osprey.

Most birders visit the marshes in April and May. The temporary marismas are usually flooded at this time of year (see page 30). The quantity of birds all depends on the water level with the best condition being when the marismas are only just submerged. At such times, groups of Flamingos, Spoonbills and herons can be seen in the hundreds, or even thousands,

mixed with huge groups of both breeding and migratory waders, above all Black-winged Stilts and Redshanks (breeding) and migratory Spotted Redshanks, Greenshanks, Wood Sandpipers and many more. Collared Pratincoles wheel overhead, sometimes in large flocks, while Little, Gullbilled, Whiskered and migrating Black Terns patrol the flats. Variable numbers of Slender-billed Gull breed (over 500 pairs in good years) and small numbers of Caspian Tern winter (although Cádiz Bay is better for this species). The more saline parts of the marsh (e.g. the saltpans at Algaida) attract Dunlin, Little Stint, Curlew Sandpiper and Grey, Golden and Kentish Plovers (with the latter breeding).

The lagoons outside the core area of Doñana, as well as the lucíos within the marismas are fed with fresh water. This shows strikingly in the birdlife. The rich aquatic vegetation of reeds and bulrushes are home to Pochard, Red-crested Pochard, Gadwall, Shoveler, Little Grebe and Purple Galinule. It is in these sites that you have the best chance of finding some of the rare species of wildflowl, like the essentially East European Ferruginous Duck, which has an isolated population here. Locally, the globally threatened Marbled Duck breeds as well. The freshwater sites sustain a taller vegetation with tamarisks and, at higher ground, Cork Oaks. This is the perfect breeding habitat for herons, storks and Spoonbills. These birds often breed in large colonies consisting of several species. Doñana is a stronghold for all breeding herons: Great Bittern, Little Bittern, Night Heron (2,500 pairs), Squacco Heron (200-400+ pairs), Cattle Egret, Little Egret (up to 6,000 pairs in wet years), Great White Egret (30 breeding pairs in 2011 and 300-400 in winter), Grey Heron (around 1,200 pairs) and Purple Heron (up to 3,000 pairs in wet years).

The Cattle Egret was originally an African species. It arrived here as early as the 16th and 17 th centuries, but until the 1950s it was pretty much restricted to the marshes of Huelva, Seville and Cádiz. Then it rapidly expanded across much of Spain, into France (1968) and has recently started to breed in the UK and the Netherlands. Although a slow starter, it is the most successful of the African immigrants, which can be seen all over western Andalucía, but is truly abundant from the Portuguese coast to Gibraltar.

The Glossy Ibis is another success story. It became extinct in Coto Doñana in the early 20th century (thereby disappearing from Spain as a breeding bird), but returned in the 1990s. Its population is rapidly increasing (now over 5,000 pairs) making it a common bird in the extensive wetlands and rice paddies in the northern and eastern part of Doñana.

The Large Psammodromus (top) is the most common lizard in the area. Its plain olive back with two cream stripes on either side of the body makes it easy to recognise.

The large Ocellated Lizard (bottom) frequents dry areas like karst and scrubland. With its agility and speed, its bright colours and a length of up to 80 cms, it is an impressive sight.

Lizards are the most frequently encountered reptiles. Particularly abundant is the Large Psammodromus. This species is readily recognised by its plain olive back with two cream stripes on the back that extend from the head all the way to the tail. Large Psammodromuses are your frequent company in scrublands, dehesas and light woodlands where they live among the leaf rubble and the vegetation. They often occur together with ‘wall lizards’, of which, according to recent taxonomic insights, three species occur: Carbonel’s (within our area only in Coto Doñana) Geniez’s (in the Sierra Morena) and Vaucher’s Wall Lizard in the rest of the area.

Another lizard you are likely to see when you venture into the more sandy areas (especially the Doñana region) is the Spiny-footed Lizard. This small lizard has strikingly yellow flanks and 6 yellow to white stripes on the greyish brown back. The Spiny-footed Lizard is the only European representative of the Acanthodactylus lizards – a large genus of desert lizards, abundant in the Sahara. The smallest lizard of the region is the Spanish Psammodromus, a rather rare, secretive and hard to find lizard that prefers rocky habitat. Much easier to find is the Ocellated Lizard. Anyone who spends much time in Andalucía will at some point see a large, bright-green flash dashing across the road. That’s him – a big, agile lizard of up to 80 centimetres. The males are handsome beasts, bright green with blue spotted flanks. The females are smaller and duller. Ocellated Lizards are rather shy and with reason. There is a score of predators who find them an ample meal. They were even a favoured ‘bushmeat’ in the poor, rural regions of Spain. If you keep your eyes open on your rambles and

don’t rush along your trail too fast, you have a good chance of seeing them at one point or another. The best areas are warm and grassy, with rocks or loose soil nearby.

You are also likely to encounter geckos during your stay in Andalucía, at least when the evenings are warm. These nocturnal animals live in rocky areas, but have found in houses and sheds a great artificial habitat. Being insectivorous, they take advantage of the street lights which attract lots of moths. On warm evenings, you can see them on the walls near (or even inside) the lights (p. 227).

There are two species of geckos in Andalucía. The most common one is the big and bulky Moorish Gecko, which has large disc-like finger-tips, with which it is able to walk over walls and ceilings. The other is the Mediterranean House Gecko, which in Andalucía is largely confined to the coast. It is more slender, with small adhesive finger-pads with a single central nail sticking out.

This is where the list of fairly easily encountered reptiles ends. However, deep in the scrub, woods and marshes of Andalucía, there are many more reptiles, for which luck or dedicated searching is required to find them. Among them are terrapins, tortoises, skinks, snakes, worm-lizards and even a chameleon.

The two species of skink that occur in Andalucía are easy to tell apart, but not easily found. Both Bedriaga’s Skink (with a thick, smooth-scaled body and relatively small limbs) and western Three-toed Skink (with a thin, long and striped body and tiny, nearly invisible limbs) prefer grassy areas or low scrub with open patches.

The two worm lizards – Iberian and Maria’s – are strange inhabitants of the area. Both closely resemble large, shiny earthworms. The first is found in the east of our region and the other in the west. Like their namesake, they live a subterranean life but can sometimes be found under rocks. Whenever excavation works are done (e.g. for road building) it becomes clear that worm lizards are actually quite common.

There are eight species of snake in western Andalucía, of which two –Viperine and Iberian Grass Snake – are aquatic. They occur in all kinds of fresh water. The Viperine Snake is very common and is relatively easy to see at the edges of small rivers in the hills and in the marshes of Coto Doñana and surroundings. Iberian Grass Snake is much rarer, although it occurs sparingly throughout the lowlands and often hunts away from water.

The back patterns are a good way to tell the scrubland snakes apart: the coinpattern is typical for for Horseshoe Whip Snake, the ladderpattern for Ladder Snake and the zigzag is reserved for Lataste’s Viper. Snakes with a uniform, grey back can be distinguished by looking at the head shape and pattern.