Fourth branchial pouch sinus: A report of 7 cases and review of the literature

Age-related changes affecting the cricoarytenoid joint seen on computed tomography

Improved swallow outcomes after injection laryngoplasty in unilateral vocal fold immobility

Treatment outcomes in HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancer: Surgery plus radiotherapy vs. definitive chemoradiotherapy

www.entjournal.com A Vendome Publication AUGUST 2018 • VOL. 97, NO. 8

The new two-piece magnetically coupled solution for non-surgical closure Round Oval www.inhealth.com We speak ENT ©2017 InHealth Technologies Manufactured by Freudenberg Medical, LLC (161010.06) The voice of experience since 1978 Magnetic4

Nasal Septal Perforation Prosthesis

Closure

3

The #1 Most Profitable Ancillary Service for Private Practice ENTs

Y our peers wanted to share an update since adding a FYZICAL Balance Center to their ENT practice:

“This is the single best thing we’ve ever done in our practice. We can’t comprehend why an otolaryngologist would not do this. It’s a no-brainer and it’s taking our profession by storm."

vehicle."

ü We're seeing 40 - 4 5 patients per day for balanc e therapy only.

ü Our hearing aid sales have increased 59%.

ü Our total patient visits are up 15% for new patients and 5% for return patients.

ü Our allergy / immunotherapy population has grown 20% since joining.

"We couldn’t be more excited about our future. Get in touch with FYZICAL. You absolutely, positively, 100% need to see for your own eyes what this can do for your practice before it’s

Tuscaloosa ENT Group

"We can't stress enough how amazing of an opportunity this really is. You will grow every part of your practice through this

too late.”

Explore FYZICAL Balance at OTO Game Changer Discover the systems and procedures behind this opportunity. Call 941-227-4314

event.

seating

open to those with open

Discover more at www.BusinessofBalance.com

to register now or learn more about this

*Limited

and only

territories*

EDITORIAL BOARD

EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS

Editor-in-Chief

Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS

Professor and Chairman, Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, and Senior Associate Dean for Clinical Academic Specialties, Drexel University College of Medicine Philadelphia, PA

Jean Abitbol, MD

Jason L. Acevedo, MD, MAJ, MC, USA

Jack B. Anon, MD

Gregorio Babighian, MD

Peter C. Belafsky, MD, PhD

Bruce Benjamin, MD

Gerald S. Berke, MD

Michael J. Brenner, MD

Kenneth H. Brookler, MD

Karen H. Calhoun, MD

Steven B. Cannady, MD

Ricardo Carrau, MD

Swapna Chandran, MD

Chien Chen, MD

Dewey A. Christmas, MD

Nicolle T. Clements, MS

Daniel H. Coelho, MD, FACS

David M. Cognetti, MD

James V. Crawford, MD

David H. Darrow, MD, DDS

Rima Abraham DeFatta, MD

Robert J. DeFatta, MD, PhD

Hamilton Dixon, MD

Paul J. Donald, MD, FRCS

Mainak Dutta, MS, FACS

Russell A. Faust, PhD, MD

Ramón E. Figueroa, MD, FACR

Charles N. Ford, MD

Paul Frake, MD

Marvin P. Fried, MD

Richard R. Gacek, MD

Andrea Gallo, MD

Frank Gannon, MD

Emilio Garcia-Ibanez, MD

Soha Ghossani, MD

William P. R. Gibson, MD

David Goldenberg, MD

Jerome C. Goldstein, MD

Richard L. Goode, MD

Samuel Gubbels, MD

Reena Gupta, MD

Joseph Haddad Jr., MD

Missak Haigentz, MD

Christopher J. Hartnick, MD

Mary Hawkshaw, RN, BSN, CORLN

Garett D. Herzon, MD

Thomas Higgins, MD, MSPH

Jun Steve Hou, MD

John W. House, MD

Glenn Isaacson, MD

Steven F. Isenberg, MD

Stephanie A. Joe, MD

Shruti S. Joglekar, MBBS

Raleigh O. Jones, Jr., MD

Petros D. Karkos, MD, AFRCS, PhD, MPhil

David Kennedy, MD

Seungwon Kim, MD

Robert Koenigsberg, DO

Karen M. Kost, MD, FRCSC

Jamie A. Koufman, MD

Stilianos E. Kountakis, MD, PhD

John Krouse, MD

Ronald B. Kuppersmith, MD, MBA, FACS

Rande H. Lazar, MD

Robert S. Lebovics, MD, FACS

Keat-Jin Lee, MD

Donald A. Leopold, MD

Steve K. Lewis, BSc, MBBS, MRCS

Daqing Li, MD

Robert R. Lorenz, MD

John M. Luckhurst, MS, CCC-A

Valerie Lund, FRCS

Karen Lyons, MD

A.A.S. Rifat Mannan, MD

Richard Mattes, PhD

Brian McGovern, ScD

William A. McIntosh, MD

Brian J. McKinnon, MD

Oleg A. Melnikov, MD

Albert L. Merati, MD, FACS

Joseph P. Mirante, MD, MBA, FACS

Ron B. Mitchell, MD

Steven Ross Mobley, MD

Jaime Eaglin Moore, MD

Thomas Murry, PhD

Ashli K. O’Rourke, MD

Ryan F. Osborne, MD, FACS

J. David Osguthorpe, MD

Robert H. Ossoff, DMD, MD

Enrique Palacios, MD, FACR

Michael M. Paparella, MD

Kourosh Parham, MD, PhD

Arthur S. Patchefsky, MD

Meghan Pavlick, AuD

Spencer C. Payne, MD

Kevin D. Pereira, MD, MS (ORL)

Nicolay Popnikolov, MD, PhD

Didier Portmann, MD

Gregory N. Postma, MD

Matthew J. Provenzano, MD

Hassan H. Ramadan, MD, FACS

Richard T. Ramsden, FRCS

Gabor Repassy, MD, PhD

Dale H. Rice, MD

Ernesto Ried, MD

Alessandra Rinaldo, MD, FRSM

Joshua D. Rosenberg, MD

Allan Maier Rubin, MD, PhD, FACS

John S. Rubin, MD, FACS, FRCS

Amy L. Rutt, DO

Anthony Sclafani, MD, FACS

Raja R. Seethala, MD

Jamie Segel, MD

Moncef Sellami, MD

Michael Setzen, MD, FACS, FAAP

Stanley Shapshay, MD

Douglas M. Sidle, MD

Herbert Silverstein, MD

Jeffrey P. Simons, MD

Raj Sindwani, MD, FACS, FRCS

Aristides Sismanis, MD, FACS

William H. Slattery III, MD

Libby Smith, DO

Jessica Somerville, MD

Thomas C. Spalla, MD

Matthew Spector, MD

Paul M. Spring, MD

Brendan C. Stack, Jr., MD, FACS

James A. Stankiewicz, MD

Jun-Ichi Suzuki, MD

David Thompson, MD

Lester D.R. Thompson, MD, FASCP

Helga Toriello, PhD, FACMG

Ozlem E. Tulunay-Ugur, MD

Galdino Valvassori, MD

Emre Vural, MD

Donald T. Weed, MD, FACS

Neil Weir, FRCS

Kenneth R. Whittemore, MD

David F. Wilson, MD

Ian M. Windmill, PhD

Ian J. Witterick, MD,MSc, FRCSC

Richard J. Wong, MD

Naoaki Yanagihara, MD

Eiji Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

Ken Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

Anthony Yonkers, MD

Mark Zacharek, MD

Joseph Zenga, MD

Liang Zhou, MD

CLINIC EDITORS

Dysphagia

Peter C. Belafsky, MD, PhD

Gregory N. Postma, MD

Facial Plastic Surgery

Anthony P. Sclafani, MD, FACS

Geriatric Otolaryngology

Kourosh Parham, MD, PhD, FACS

Karen M. Kost, MD, FRCSC

Head and Neck

Ryan F. Osborne, MD, FACS

Paul J. Donald, MD, FRCS

Reena Gupta, MD

Imaging

Enrique Palacios, MD, FACR

Ramón E. Figueroa, MD, FACR

Laryngoscopic

Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS

Otoscopic

John W. House, MD

Brian J. McKinnon, MD

Pathology

Lester D.R. Thompson, MD, FASCP

Pediatric Otolaryngology

Rande H. Lazar, MD

Rhinoscopic

Eiji Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

Dewey A. Christmas, MD

Joseph P. Mirante, MD, MBA, FACS

Ken Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

Special Topics

Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS

Thyroid and Parathyroid

David Goldenberg, MD

218 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal August 2018

Balloon dilation for Eustachian tube dysfunction

The superior, durable results your patients deserve. With

the safety you can count on.

A randomized, controlled trial comparing balloon dilation with ongoing medical therapy as treatment for persistent Eustachian tube dysfunction reported zero complications and significant symptom improvement through 12 months for patients treated with the XprESS™ ENT Dilation System.1

1 Meyer TA, O’Malley E, Schlosser RJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of balloon dilation as a treatment for persistent Eustachian tube dysfunction with 1-year follow-up. Otol Neurotol. 2018. DOI: 10.1097/

MAO.0000000000001853

INDICATIONS FOR USE: To access and treat the maxillary ostia/ethmoid infundibula in patients 2 years and older, and frontal ostia/recesses and sphenoid sinus ostia in patients 12 years and older using a transnasal approach. The bony sinus outflow tracts are remodeled by balloon displacement of adjacent bone and paranasal sinus structures. To dilate the cartilaginous portion of the Eustachian tube for treating persistent Eustachian tube dysfunction in patients 18 years and older using a transnasal approach.

Please see Instructions for Use (IFU) for a complete listing of warnings, precautions, and adverse events as well as cleaning, sterilizing and care for surgical instruments.

CAUTION: Federal (USA) law restricts these devices to sale by or on the order of a physician.

ENTELLUS MEDICAL and XPRESS are trademarks of Entellus Medical, Inc.

DURABLE symptom improvement through 12 months

NEW CLINICAL DATA Read more at: go.ent.stryker.com/ETDRCT1YearData

©2018 Entellus Medical, Inc. 1738-762 rA 07/2018

Balloon Dilation (N=28) Control (N=27) Baseline (N=54) 6 Weeks (N=51) 3 Months (N=52) 6 Months (N=51) 12 Months (N=49) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 4.6 2.1 2.12.1 2.1 MILD (NO PROBLEM) MODERAT E SEVERE M EAN OVERALL ETDQ-7 SCORE MEAN OVERALL ETDQ-7 SCORE ∆= -2.9±1.4 ∆= -0.6±1.0 p<0.0001 p<0.0001 for change from baseline to all follow-up periods BaselineFollow-up Baseline Follow-up ET balloon dilation

Balloon Dilation (N=28) Control (N=27) Baseline (N=54) 6 Weeks (N=51) 3 Months (N=52) 6 Months (N=51) 12 Months (N=49) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 4.6 2.1 2.12.1 2.1 MILD (NO PROBLEM) MODERAT E SEVERE M EAN OVERALL ETDQ-7 SCORE MEAN OVERALL ETDQ-7 SCORE ∆= -2.9±1.4 ∆= -0.6±1.0 p<0.0001 p<0.0001

from baseline

follow-up periods BaselineFollow-up Baseline Follow-up ET balloon dilation with XprESS is SAFE

% COMPLICATION RATE

SUPERIOR to medical management

for change

to all

0

Editor-in-Chief Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS 219 N. Broad St., 10th Fl., Philadelphia, PA 19107 entjournal@phillyent.com Ph: 215-732-6100

Managing Editor Linda Zinn

Manuscript Editors Martin Stevenson and Wayne Kuznar

Associate Editor, Reader Engagement Megan Combs

Creative Director Eric Collander

National Sales Manager Mark C. Horn mhorn@vendomegrp.com Ph: 480-895-3663

Traffic Manager Eric Collander

Please send IOs to adtraffic@vendomegrp.com

All ad materials should be sent electronically to: https://vendome.sendmyad.com

Customer Service/Subscriptions

www.entjournal.com/subscribe Ph: 888-244-5310 email: VendomeHM@emailpsa.com

Reuse Permissions Copyright Clearance Center info@copyright.com Ph: 978-750-8400 Fax: 978-646-8600

Chief Executive Officer Jane Butler

Chief Marketing Officer Dan Melore

Vice President, Finance Bill Newberry

Vice President, Custom Media Jennifer Turney Director, Circulation Rachel Beneventi

ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal (ISSN: Print 0145-5613, Online 1942-7522) is published 9 times per year in Jan/Feb, Mar, Apr/May, June, July, Aug, Sept, Oct/ Nov and Dec, by Vendome Group, LLC, 237 West 35th Street, 16th Floor, New York, NY 10001-1905.

©2018 by Vendome Group, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal may be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast in any form or in any media without prior written permission of the publisher. To request permission to reuse this content in any form, including distribution in education, professional, or promotional contexts or to reproduce material in new works, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center at info@ copyright.com or 978.750.8400.

EDITORIAL: The opinions expressed in the editorial and advertising material in this issue of ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal are those of the authors and advertisers and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or recommendations of the publisher, editors, or the staff of Vendome Group, LLC. ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal is indexed in MEDLINE/PubMed and Current Contents/Clinical Medicine and Science Citation Index Expanded. Editorial offices are located at 812 Huron Rd., Suite 450, Cleveland, OH 44115. Manuscripts should be submitted online at www.editorialmanager.com/entjournal. Instructions for Authors are available at www.entjournal.com.

SUBSCRIPTIONS: For questions about a subscription or to subscribe, please contact us by phone: 888-244-5310; or email: VendomeHM@emailpsa.com. Individual subscriptions, U.S. and possessions: 1 year $225, 2 years $394; International: 1 year $279, 2 years $488; Single copies $28; outside the U.S., $40.

POSTMASTER: send address changes to Ear, Nose & Throat Journal, PO Box 11404 Newark, NJ 07101-4014.

220 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal August 2018

ADVERTISER INDEX Pages Acclarent 223 Arbor .............................................. 246, 247 CANT Corporation ................................. 225 Compulink CVR3 Entellus .................................................. 219 Fyzical 217 InHealth Technologies ........................ CVR2 Lumenis ................................................. 221 McKeon Products CVR4, 241 Medtronic .............................................. 235 OmniGuide 253 Optim LLC ............................................. 229 Reliance Medical ................................... 231 RhinoWorld 237 SinOptim LLC ........................................ 243

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

236 Fourth branchial pouch sinus: A report of 7 cases and review of the literature

Indranil Pal, MS; Saumitra Kumar, MS; Ankur Mukherjee, MS, DNB; Bibhas Mondal, MS; Anindita Sinha Babu, MD

244 Age-related changes affecting the cricoarytenoid joint seen on computed tomography

Georges Ziade, MD; Sahar Semaan, MD; Sarah Assaad, MPH; Abdul Latif Hamdan, MD, EMBA, MPH

250 Improved swallow outcomes after injection laryngoplasty in unilateral vocal fold immobility

Steven Zuniga, MD; Barbara Ebersole, MA, CCC-SLP; Nausheen Jamal, MD

ONLINE EXCLUSIVES

E1 Treatment outcomes in HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancer: Surgery plus radiotherapy vs. definitive chemoradiotherapy

Dominique Rash, MD; Megan E. Daly, MD; Blythe Durbin-Johnson, PhD; Andrew T. Vaughan, PhD; Allen M. Chen, MD

E8 Protective effect of pentoxifylline on amikacin-induced ototoxicity

Mohammad Waheed El-Anwar, MD; Said Abdelmonem, MD; Ebtessam Nada, MD; Dalia Galhoom, MD; Ahmed A. Abdelsameea, MD

E13 Chronic otitis media with effusion in chronic sinusitis with polyps

Mary Daval, MD; Hervé Picard, MD, MSc; Emilie Bequignon, MD; Philippe Bedbeder, MD; André Coste, MD, PhD; Denis Ayache, MD, PhD; Virginie Escabasse, MD, PhD

E19 Ancillary medications and outcomes in post-tonsillectomy patients

Ashley P. O’Connell Ferster, MD; Eric Schaefer, MS; Jane R. Schubart, MBA, PhD; Michele M. Carr, DDS, MD, PhD

E25 Safety and utility of direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy in patients hospitalized with croup

Daniel P. Fox, MD; Julina Ongkasuwan, MD

E31 Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the epiglottis excised with a carbon dioxide laser: Case report and literature review

Blake Raggio, MD; Neil Chheda, MD

E34 Visualized ethmoid roof cerebrospinal fluid leak during frontal balloon sinuplasty

Navdeep R. Sayal, DO; Eytan Keider, DO; Shant Korkigian, DO

E39 Dacryocystorhinostomy with a thulium:YAG laser—a case series

Christopher Tang, MD; Scott Rickert, MD; Niv Mor, MD; Andrew Blitzer, MD, DDS; Martin Leib, MD

E43 A rare case of odontoameloblastoma in a geriatric patient

Pratyusha Yalamanchi, MD, MBA; Orly Coblens, MD; Meejin Ahn, DO; Steven B. Cannady, MD; Jason G. Newman, MD

DEPARTMENTS

222 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal August 2018 EDITORIAL OFFICE Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS, Editor-in-Chief • 219 N. Broad St., 10th Fl. • Philadelphia, PA 19107 CONTENTS AUGUST 2018 • VOL. 97, NO. 8

220 Advertiser Index 224 ENT Journal Online 226 Editorial 227 Otoscopic Clinic 230 Imaging Clinic 233 Head and Neck Clinic E46 Guest Editorial E48 Rhinoscopic Clinics E52 Laryngoscopic Clinic

*In the U.S. only

ACCLARENT AERA® is intended for use by physicians who are trained on Acclarent technology. Eustachian tube balloon dilation has associated risks, including tissue and mucosal trauma, infection, or possible carotid artery injury. Prior to use, it is important to read the Instructions for Use and to understand the contraindications, warnings, and precautions associated with these devices. The safety of the device as used under local anesthesia has not been evaluated.

Caution: Federal (US) law restricts the sale, distribution or use of these devices to, by or on the order of a physician. Third party trademarks used herein are trademarks of their respective owners. This site is intended for visitors from the United States and published by Acclarent, Inc., which is solely responsible for its contents.

©2017 Acclarent, Inc. All rights reserved. 061003-170803

ACC L ARE NT AER A® Eustachian Tube Balloon Dilation System GO TO THE SOURCE.

only balloon dilation system*speci cally designed to address persistent Eustachian tube dysfunction at its source. OpenMyEars.com | Acclarent.com

The

JOURNAL ONLINE

Ear, Nose & Throat Journal's website is easy to navigate and provides readers with more editorial content each month than ever before. Access to everything on the site is free of charge to physicians and allied ENT professionals. To take advantage of all our site has to offer, go to www.entjournal. com and click on the “Registration” link. Once you have filled out the brief registration form, you will have full access. Explore and enjoy!

ONLINE EXCLUSIVES

Treatment outcomes in HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancer: Surgery plus radiotherapy vs. definitive chemoradiotherapy

Dominique Rash, MD; Megan E. Daly, MD; Blythe Durbin-Johnson, PhD; Andrew T. Vaughan, PhD; Allen M. Chen, MD

We performed a retrospective study to compare clinical outcomes among 51 consecutively presenting patients—38 men and 13 women, aged 46 to 74 years (median: 57)— with locally advanced human papillomavirus (HPV)-negative oropharyngeal cancer who were treated with either primary surgery followed by postoperative radiotherapy (S/RT group; n = 22) or definitive chemoradiotherapy alone (CRT group; n = 29). Within the cohort, 45 patients reported....

Protective effect of pentoxifylline on amikacininduced ototoxicity

Mohammad Waheed El-Anwar, MD; Said Abdelmonem, MD; Ebtessam Nada, MD; Dalia Galhoom, MD; Ahmed A. Abdelsameea, MD

We conducted an animal experiment to assess the effect of adding pentoxifylline to amikacin to prevent amikacin-induced ototoxicity. This research was conducted on 24 rats arranged in four groups of 6. One group was injected with 200 mg/kg of intramuscular amikacin once daily for 14 days (AMK-only group). Another received 25 mg/kg of oral pentoxifylline and 200 mg/kg of intramuscular amikacin once daily for 14 days (PTX-AMK 14/14 group). A third group received 25 mg/kg of oral pentoxifylline for 28 days and 200 mg/kg of intramuscular amikacin once daily for 14 days on days 15 through 28 of the pentoxifylline regimen (PTX-AMK 28/14....

Chronic otitis media with effusion in chronic sinusitis with polyps

Mary Daval, MD; Hervé Picard, MD, MSc; Emilie Bequignon, MD; Philippe Bedbeder, MD; André Coste, MD, PhD; Denis Ayache, MD, PhD; Virginie Escabasse, MD, PhD

The relationship between otitis media with effusion (OME) and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis (CRSwNP) remains unclear. We conducted a cross-sectional study of 80 consecutively presenting patients—42 males and 38 females, aged 15 to 76 years (median: 48)—who were diagnosed with CRSwNP. Our aim was to ascertain the prevalence of OME in CRSwNP patients, to determine whether the severity of CRSwNP affected....

Ancillary medications and outcomes in posttonsillectomy patients

Ashley P. O’Connell Ferster, MD; Eric Schaefer, MS;

Jane R. Schubart, MBA, PhD;

Michele M. Carr, DDS, MD, PhD

To investigate the impact of medications on outcomes after tonsillectomy, a retrospective review using the MarketScan database was performed. A total of 306,536 privately insured children and adolescents (1 to 17 years old) who underwent tonsillectomy/adenoidectomy were identified from 2008 to 2012. Pharmaceutical claims identified patients who received outpatient prescriptions for ibuprofen, steroids, or topical anesthetics until discharge and for medications for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity....

Safety and utility of direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy in patients hospitalized with croup

Daniel P. Fox, MD; Julina Ongkasuwan, MD

Acute croup is a common admitting diagnosis for pediatric patients. If a patient is not responding to medical management for presumed croup, the otolaryngology team is occasionally consulted for direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy (DLB) to rule out tracheitis or another airway pathology. We conducted a study to determine if inpatient DLB in acute croup is safe and efficacious and to correlate preoperative vital signs with intraoperative findings. We reviewed the charts of 521 patients with an admitting diagnosis of acute tracheitis, acute laryngotracheitis, or croup. Of this group, 18 patients—11 boys and 7 girls, aged 1 month to 3.3 years (mean: 1.3 yr)—had undergone inpatient DLB. Comorbidities, complications, and level of care were also analyzed. Five patients (28%) had gastrointestinal reflux ....

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the epiglottis excised with a carbon dioxide laser: Case report and literature review

Blake Raggio, MD; Neil Chheda, MD

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) is a benign neoplasm of intermediate biologic potential. It rarely occurs in the larynx, and it has not been previously reported in the epiglottis. We treated a 66-year-old woman who presented with progressive dysphonia and a mass on her suprahyoid epiglottis. The tumor was completely excised with a CO 2 laser; no adjuvant therapy was administered. Histopathology revealed that the mass was an IMT. No evidence of recurrence was noted after 6 months of follow-up. We present what we believe is the....

224 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal August 2018

www.entjournal.com

Visualized ethmoid roof cerebrospinal fluid leak during frontal balloon sinuplasty

Navdeep R. Sayal, DO; Eytan Keider, DO; Shant Korkigian, DO

Balloon sinus dilation (BSD) is generally accepted as a safe alternative to traditional sinus surgery. It is a unique technique designed to potentially minimize complications....

Dacryocystorhinostomy with a thulium: YAG laser—a case series

Christopher Tang, MD; Scott Rickert, MD; Niv Mor, MD; Andrew Blitzer, MD, DDS; Martin Leib, MD

We conducted a retrospective chart review of 27 patients—7 men and 20 women, aged 47 to 94 years (mean: 71.3)—with symptomatic epiphora secondary to dacryostenosis who....

A rare case of odontoameloblastoma in a geriatric patient

Pratyusha Yalamanchi, MD, MBA; Orly Coblens, MD; Meejin Ahn, DO; Steven B. Cannady, MD; Jason G. Newman, MD

Odontoameloblastoma is an extremely rare tumor derived from odontogenic epithelium and mesenchyme. In the fewer than 20 reported cases, odontoameloblastoma is described

as occurring in the maxilla or mandible of young men with a history of unerupted teeth. Here we report a case of a 73-year-old woman who presented to the dentist for routine cleaning and x-rays, which displayed a mandibular lesion....

ONLINE DEPARTMENTS

Guest Editorial: ENT Journal at the crossroads: Personal perspectives from an editorial board member

Rhinoscopic Clinics: A polyp originating in the middle turbinate and extending to the maxillary sinus ostium

Jae Hoon Lee, MD

Endoscopic view of postoperative maxillary sinus mucoceles separated by bony septum

Jae-Hoon Lee, MD

Laryngoscopic Clinic: Isolated lymphatic malformation of the postcricoid space

Douglas Sidell, MD; Arjun S. Joshi, MD; Christopher R. Kieliszak, DO; Steven A. Bielamowicz, MD

Reach More Patients.

People come in different shapes and sizes.The same piece of equipment does not fit them all.Make oropharyngeal surgery easier with a simple extension.The CANT Corporation has created the Dedo Extension that fits between the Mayo Stand and the Crowe-Davis mouth gag so that it can be adjusted to fit larger patients.The DE98-A mounts to the square-sided Mayo Stand,while the DE98-B fits the tubular-sided support. The Dedo Extension - a simple but effective solution.

Applicable Procedures

• T&A’s

The Crowe-Davis mouth

• Uvuloplasty

• Palatoplasty

• All oropharyngeal procedures using a Crowe-Davis mouth gag

Volume 97, Number 8 www.entjournal.com 225 ENT JOURNAL ONLINE

The Dedo Extension

The Mayo Stand

gag

337 • 233 • 2666, ext.9 • www.jrcant.com • PO Box 3522 • Lafa yette,LA 70502 Extension “DE98-B” also available for tubular support Extension “DE98-A” A B Dedo Ext 9 (ENT1/18/05) 1/19/05 1:51 PM Page 1

Telemedicine: Part II

[Note: This is Part II of a two-part Editorial. Part I was published in the July 2018 issue. It has been adapted with permission from Rubin J, Sataloff RT, Korovin G. Telemedicine. In: Rubin J, Sataloff RT, Korovin, G (eds). Diagnosis and Treatment of Voice Disorders. 4th Ed. San Diego: Plural Publishing, Inc.; 2014:781-4.]

A 2012 Guest Editorial for Ear, Nose & Throat Journal outlines ENT-related usages of telemedicine.15 Some examples include: Louisiana in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, where a telemedicine service was developed for neurotology patients,16 and Anchorage, Alaska, where a remote video-otoscopy service has been devised for post-tympanotomy tube insertion patients.17 There are several potential benefits of telemedicine for patients with voice disorders and their providers, including remote readings of strobovideolaryngoscopic and high-speed imaging, as well as provision of voice therapy.18 Telemedicine has several issues that still must be addressed if it is to become a pillar of medical care. Initial issues included difficulty in use, expense, limited reach, and slowness of service. Many of these issues have been resolved as technology has improved. Concerns regarding patient confidentiality, security, and regulatory challenges remain, however. Reimbursement issues also are still problematic in many areas, placing the investment burden on the hospital healthcare system or physician. Furthermore, cultural barriers are not easy to overcome as patients and doctors need to adapt to telemedicine paradigms for most effective use of the new techniques. There also are legal issues that remain a substantial impediment, especially in the United States, where medical licensure is on a state-by-state basis. Problematic examples can be envisioned readily. For example, if a physician is performing a remote examination on a patient who is physically in the state of California while the physician is working in and only licensed to practice medicine in the state of New York, is the physician liable for practicing medicine in California without a license? At present, the answer is yes. The location of practice is defined as the location of the patient, not the physician. Clarification also is required for analysis of biosignals, such as radiologic examinations that are stored in one state but reviewed in another. Similar queries could be posited for physicians practicing remotely between countries. As of the time of writing this editorial, the underlying suppositions that telemedicine is cost-effective and that it improves well-being are still unproven. The Whole

System Demonstrator Programme was launched by Great Britain’s Department of Health in May 2008. It is the largest randomized, controlled trial of telehealth and telecare in the United Kingdom, involving (according to the Department of Health in its “Early Headline Findings”)19 6,191 patients and 238 general practices across three sites: Newham, Kent, and Cornwall. In total, 3,030 people with one of three conditions (diabetes, heart failure, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) were included in the telehealth trial. For the telecare element of the trial, people were selected using the Fair Access to Care Services criteria.19

The results are still being analyzed. The UK Department of Health states: “If used correctly, telehealth can deliver a 15% reduction in A&E [accident and emergency department] visits, a 20% reduction in emergency admissions, a 14% reduction in elective admissions, a 14% reduction in bed days, and an 8% reduction in tariff costs. More strikingly…a 45% reduction in mortality rates.”19

In 2012, Steventon et al described 179 general practices and 3,230 people with diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or heart failure recruited from practices between May 2008 and November 2009 and concluded that telehealth is associated with lower mortality and emergency admission rates.20 The reasons for the short-term increases in admissions for the control group are not clear, but the trial recruitment processes could have had an effect. However, as Gornall stated, “Whether telehealth can help to reduce NHS costs, chiefly by reducing admissions and freeing up beds for closure, remains a complex question.”21

The BBC website, on March 21, 2013, ran the headline, “NHS remote monitoring ‘costs more.’”22 In this article, they stated, “The cost per quality—adjusted life year—a combined measure of quantity and quality of life of telehealth—was £92,000 when added to usual care. This is way above the threshold of £30,000 that the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence has set. A bestcase scenario considering that the price of equipment was likely to fall over time and that services were not running at full capacity during the trial, saw the probability that the service was cost-effective rise from 11% to 61%.”

In 2016, Gunter et al published a systematic review of the current use of telemedicine for postdischarge surgical care.23 Their review provided 72 references, including seven articles that studied clinical outcomes associated with telemedicine. All reported either no difference in the numbers of complications in the telemedicine group versus the group receiving usual care, or slightly higher

Continued on page 228

226 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal August 2018

EDITORIAL

Persistent stapedial artery with ankylosis of the stapes footplate

Fiona C.E.

A 46-year-old man presented to the Otolaryngology Department with a 10-year history of right-sided hearing loss. He denied any prior ear problems or family history of hearing loss. An audiogram demonstrated a right maximal conductive loss and a Carhart notch. Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a 2-mm lucency on the oval window (figure 1). The opinion of the radiologist was that this was in keeping with an otosclerotic plaque.

The patient gave consent for middle ear exploration and stapedectomy. His malleus and incus were mobile. A large, pulsating vessel was found passing through the crura of the stapes, consistent with a persistent stapedial artery (PSA) (figure 2). His stapes footplate was found to be fixed. Because of the large PSA, stapedectomy was abandoned, despite the presence of a fixed stapes.

Postoperatively, the CT images were reviewed and the lucency that had previously been identified on the

stapes footplate was determined to be a PSA. The patient also was noted to have an absent foramen spinosum, one of the features of PSA (figure 3).

Given the position and size of the patient’s PSA, his treatment options were either hearing aids or ablation of the PSA followed by a stapedotomy. Because of the theoretical risks of ablation, including bleeding and injury to the facial nerve, the patient decided to use hearing aids to manage his conductive hearing loss.

PSA is a rare congenital vascular anomaly with a prevalence of 0.02% to 0.5%.1 It may present as a pulsatile middle ear mass or may appear as an incidental finding during middle ear surgery. Most patients with a PSA are asymptomatic. The classic CT findings suggestive of a PSA include a soft-tissue prominence in the region of the tympanic segment of the facial nerve and the absence of the ipsilateral foramen spinosum. These findings also can include a small canaliculus

Volume 97, Number 8 www.entjournal.com 227

From the Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, The Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital, East Melbourne, Victoria, Australia (Dr. Hill and Mr. Tykocinski); and the Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, The Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia (Dr. Bing and Mr. Tykocinski). The case described in this article occurred at The Alfred Hospital.

OTOSCOPIC CLINIC

Hill, MBBS; Bing Teh, MBBS; Michael Tykocinski, FRACS

Figure 1. CT demonstrates the opacification over the stapes footplate (arrow), originally reported as a sclerotic plaque but determined to be a PSA.

originating from the carotid canal and enlargement of the tympanic segment of the facial nerve canal or a separate canal paralleling the facial nerve. In the present case, the presence of the soft tissue on the stapes footplate initially gave the appearance of an otosclerotic plaque. This case illustrates an unusual presentation of a PSA and demonstrates the importance of thorough middle ear assessment in the management conductive hearing loss.

Reference

1. Moreano EH,

D,

Continued from page 226 complication rates in the telemedicine group, although they could not relate those complications causally to the use of telemedicine. The greatest financial savings noted in their review accrued to the patients, particularly savings related to travel time and costs, although savings to healthcare systems were found, as well.

The role of telemedicine is increasing. Newer technologies such as mobile phone messaging applications, short message service, and multimedia message service have become readily available. Such technologies lend themselves to telemedical approaches. However, the future standing of telemedicine in medicine in general and in otolaryngology specifically remains unclear.

References

15. Garritano FG, Goldenberg D. Telemedicine in otolaryngology–head and neck surgery. Ear Nose Throat J 2012;91(6):226–9.

16. Arriaga MA, Nuss D, Scrantz K, et al. Telemedicine- assisted neurotology in post-Katrina Southeast Louisiana. Otol Neurotol 2010;31(3):524–7.

17. Kokesh J, Ferguson As, Patricoski C, et al. Digital images for postsurgical follow-up of tympanostomy tubes in remote Alaska. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008;139(1):87–93.

18. Rubin, J, Sataloff, RT, Korovin, G. Telemedicine. In: Diagnosis and Treatment of Voice Disorders, 4th edition. San Diego: Plural Publishing, Inc.; 2014:781-4.

19. Department of Health. Whole System Demonstrator Programme: Headline findings. December 2011. https://www.gov.uk/government/ publications/whole-system-demonstrator-programme-headlinefindings-december-2011. Accessed June 11, 2018.

20. Steventon A, Bardsley M, Billings J, et al. Effect of telehealth on use of secondary care and mortality: Findings from the Whole System Demonstrator cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2012;344:e3874.

21. Gornall J. Does telemedicine deserve the green light? BMJ 2012;345:e4622.

22. No authors listed. NHS remote monitoring ‘costs more.’ BBC News. March 21, 2013. www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-21874978. Accessed July 12, 2018.

23. Gunter RL, Chouinard S, Fernandes-Taylor S, et al. Current use of telemedicine for post-discharge surgical care: A systematic review. J Am Coll Surg 2016;225(5):915-27.

John S. Rubin, MD, FACS, FRCS

Royal National Throat Nose and Ear Hospital

National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery

University College London Hospitals NHS Trust

School of Health Sciences

City, University of London

Department of Surgery

University College of London

London, United Kingdom

Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS

Editor-in-Chief

Ear, Nose & Throat Journal

1994;104(3 Pt 1):309-20.

Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery

Drexel University College of Medicine

Philadelphia

228 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal August 2018

CLINIC

EDITORIAL OTOSCOPIC

Figure 2. In this photograph down the external auditory canal with the tympanic membrane elevated, the pulsatile stapedial artery can be seen running over the stapes footplate, between the anterior and posterior crura. The stapedius tendon and chorda tympani nerve are seen in the foreground.

Figure 3. CT reveals the bilateral foramen ovale (red arrows) and the foramen spinosum on the left (yellow arrow), which is absent on the right.

Paparella MM, Zelterman

Goycoolea MV. Prevalence of facial canal dehiscence and of persistent stapedial artery in the human middle ear: A report of 1000 temporal bones. Laryngoscope

Portability Redefined

ENTity

Protects endoscope from damage during transport

Crash cart compatible

Shoulder strap offers mobility to move throughout hospital

ENTity™ XL Flexible Laryngoscope Everywhere ENT Clinicians Need to Be Outpatient Clinic | ICU | Bedside | ER | Radiation Oncology | OR TM Designed to empower ENT clinicians with the visibility & mobility they need Powerful innovation. proven performance. All-in-one, portable, flexible ENT scopes for clinic and bedside Contact Us Today : 800.225.7486 / sales@optim-llc.com Find out how to make the transition to portability with our endoscope trade-in program* *Program valid through September 30, 2018 | Mention offer code: GetTheBest www.optim-llc.com/entitygetthebest you’ve seen the rest now get the best Trade-in Promo Flexible Laryngoscopes No cables. No additional equipment. No Limits.

EndoCarrier

Transport System

ENTity XL & ENTity SDXL Laryngoscope Brightest, long-lasting patented LED lighting technology Durable craftsmanship and design with industry leading two-year warranty Standard and small diameter options to meet patient needs Get the Best - End the summer by adding the new generation ENTity XL Flexible Laryngoscope to your practice. Trade in your old endoscope for a credit towards the purchase of a brand new ENTity XL or SDXL Laryngoscope featuring our latest next generation LED illumination.

Powerful Innovation

IMAGING CLINIC

Bilateral massive pharyngoceles

Norair Adjamian, DO; Lyndsay L. Madden, DO; Libby J. Smith, DO

A 20-year-old collegiate man presented for evaluation of progressively worsening throat pain and left-sided neck bulging that occurred while he was playing the trumpet. He rated the pain as moderate and compared it to a sore throat one would experience with a common cold. The pain and neck fullness completely subsided when he was not playing the trumpet. He denied having associated dysphagia or dyspnea. His physical examination demonstrated a large, soft, left, easily compressible lateral neck fullness when he puffed his cheeks. Flexible laryngoscopy demonstrated no abnormalities of vocal fold motion or laryngeal lesions.

Based on these findings, a fine-cut, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) imaging study of the larynx was acquired. Imaging was first taken with the patient at rest and then with his achieving positive pharyngeal pressure by exhaling through pursed lips, mimicking playing the trumpet. The results revealed normal anatomy at rest (figure 1) and massive bilateral pharyngoceles with positive pharyngeal pressure when exhaling (figure 2). CT showed no evidence of an underlying mass, fluid, or infection.

Reports of pharyngoceles are uncommon in the literature. They also have been described as lateral pharyngeal diverticulum, pharyngeal pouch, aerocele, pulsion pouch, and pulsion diverticulum.1 Dysphagia is described as the most common presenting complaint, followed by neck swelling and food regurgitation.2 Therefore, the differential diagnosis can be vast, and misdiagnosis often can occur without proper imaging studies.

The etiology of pharyngoceles often has been associated with elevations in intrapharyngeal pressure, as seen in individuals who play wind instruments; however, it has been postulated that pharyngoceles also can be a manifestation of a branchial arch anomaly, specifically a branchial sinus outpouching that may dilate over time.3

Nonsurgical treatment measures have provided excellent outcomes in symptomatic patients.4 A compressive neck wrap worn when he was playing the trumpet provided symptomatic relief to our patient. When surgery is required, external or endoscopic approaches are used.5 With proper history acquisition, physical exam, and imaging studies with normal and elevated pharyngeal pressures, pharyngoceles can be correctly diagnosed and treated appropriately.

From the Department of Medicine, Kansas City University of Medicine and Biosciences, Kansas City, Mo. (Dr. Adjamian); the Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, Wake Forest University Center for Voice and Swallowing, Winston-Salem, N.C. (Dr. Madden); and the Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, University of Pittsburgh Voice Center, Pittsburgh, Pa. (Dr. Smith). The case described in this article occurred at the University of Pittsburgh Voice Center.

230 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal August 2018

Figure 1. Postcontrast axial CT section at the level of the hyoid bone (triangle) and pharynx (asterisk) demonstrates normal hypopharyngeal anatomy without positive pharyngeal pressure.

Since 1898, Reliance Medical Products has had an unmatched reputation for reliability and craftsmanship, building everything from exam chairs to ENT cabinets and accessories that stand up to anything. Including the test of time. And we’d like to thank all the doctors along the way who’ve helped us reach this proud milestone.

Learn how our history of excellence can help build a stronger future for you. Stop by our booth #1732 at the AAO-HNSF annual meeting.

BUILT TO LAST. AND LAST. AND LAST. A REPUTATION 120 YEARS IN THE MAKING.

Builttosupport.com © 2018 Haag-Streit USA. All Rights Reserved.

800.735.0357 |

2018 Reliance 710 Premiere Chair

1962 Reliance Model 630 Chair

1926 Reliance Barber Chair

Figure 2. A: Postcontrast axial CT section at the level of the hyoid bone (triangle), mandible (circle), and pharynx (asterisk) demonstrates bilateral pharyngoceles with positive pharyngeal pressure. B: This postcontrast axial CT section demonstrates massive bilateral pharyngoceles at the level of the pharynx (asterisk), below the hyoid.

References

1. Norris CW. Pharyngoceles of the hypopharynx. Laryngoscope 1979;89(11):1788–1807.

2. Naunheim M, Langerman A. Pharyngoceles: A photo-anatomic study and novel management. Laryngoscope 2013;123(7):1632–8.

3. Chang CY, Furdyna JA. Bilateral pharyngoceles (branchial cleft anomalies?) and endoscopic surgical considerations. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2005;114(7):529–32.

4. Daultrey C, Colley S, Costello D. “Doctor I have a frog in my throat”: Bilateral pharyngoceles in a recreational trumpet player. Journal of Laryngology & Voice 2013;3(1):18-21.

5. Yılmaz T, Cabbarzade C, Süslü N, et al. Novel endoscopic treatment of pharyngocele: Endoscopic suture pharyngoplasty. Head Neck 2014;36(8):E78–80.

232 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal August 2018

A B IMAGING CLINIC

HEAD AND NECK CLINIC

Castleman disease

A 57-year-old man presented with a 3-year history of a left anterior neck mass. It was nonpainful and did not cause dysphagia, hoarseness, or difficulty breathing. Physical examination was significant for a firm, well-circumscribed, nonulcerating mass at left level 1B, with no overlying skin changes. Additionally, he had asymmetric left tonsillar hypertrophy. Flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy revealed no abnormalities. Computed tomography (CT) of the neck with contrast revealed lymphadenopathy involving left level 1B measuring 3.1 cm (figure 1) and left supraclavicular

fossa measuring 2.1 cm, as well as asymmetric fullness of the left palatine tonsil. The patient proceeded with bronchoscopy, esophagoscopy, direct laryngoscopy, tonsillectomy, and open neck biopsy. Right tonsil, left tonsil, and level 1B lymph node surgical specimens were sent for review.

Histologically, the lymph node showed an overall increase of small atrophic follicles. The mantle zone was expanded, forming an “onion-skin” appearance that was penetrated by hyalinized vessels at a right angle (figure 2, A). Two atrophic germinal centers within a single

From the Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, Philadelphia (Dr. Cohn); and the Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (Dr. Cohn and Dr. Hu) and the Department of Pathology (Dr. Zhou), Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia. The case described in this article occurred at Hahnemann University Hospital, Philadelphia.

Volume 97, Number 8 www.entjournal.com 233

Jason E. Cohn, DO; Jing Zhou, MD, PhD; Amanda Hu, MD

Figure 1. Left level 1B lymphadenopathy measuring 3.1 cm is seen on contrastenhanced CT of the neck.

mantle zone were frequently seen. Interfollicular areas showed paracortical plasmacytosis (figure 2, B). The histology of the tonsils revealed lymphoid hyperplasia with some atrophic germinal centers with an expanded mantle zone. Interfollicular areas also showed increased hyalinized vasculature and plasma cells.

Immunohistochemistry of the tissues was negative for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8). Additionally, Epstein-Barr virus RNA in situ hybridization was negative. Flow cytometry revealed normal cell populations. Given these clinical findings, the patient was diagnosed with Castleman disease (CD).

CD, also known as angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia or giant lymph node hyperplasia, is a rare lymphoproliferative disease characterized by benign, localized enlargement of lymph nodes.1 CD presents more commonly as a solitary mass with a benign course, known as the localized type. Less commonly, patients can present with a more aggressive form involving constitutional symptoms, hepatosplenomegaly, and laboratory abnormalities, referred to as the multicentric type. The multicentric type is usually associated with infection or malignancy such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), HHV-8, Kaposi sarcoma, or lymphoma.1,2

Most individuals affected by CD are young to middle-aged, with males and females equally affected. Most cases are asymptomatic, unicentric, and are the hyaline-vascular tissue type.2 The etiology of CD is believed to involve the overproduction of cytokine IL6, which has been shown to increase the proliferation and survival of B cells.1 Therefore, CD is usually treated with immunotherapy.3

Although there have been cases of CD involving the tonsils,4 this is rare. Our case also is unique because the patient’s disease was multicentric and the mixedtype (both hyaline-vascular and plasma-cell type),

and he tested negative for HIV (serology) and HHV-8 (immunohistochemical staining). HIV-negative CD has been associated with certain conditions including autoimmune disease, collagen vascular disorders, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and glomerulopathy. In some instances, the etiology is unknown.3 Once an underlying cause is identified, proper targeted therapy can be instituted.

References

1. Newlon JL, Couch M, Brennan J. Castleman’s disease: Three case reports and a review of the literature. Ear Nose Throat J 2007;86(7):414-18.

2. Wu PW, Lee TJ, Huang CC, et al. Intermittent hemoptysis and blood-tinged sputum. Castleman disease (CD), hyaline-vascular type. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;139(7):743-4.

3. Muskardin TW, Peterson BA, Molitor JA. Castleman disease and associated autoimmune disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2012;24(1):76-83.

4. Thakral B, Zhou J, Medeiros LJ. Extranodal hematopoietic neoplasms and mimics in the head and neck: An update. Hum Pathol 2015;46(8):1079-1100.

234 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal August 2018

Figure 2. A: Histology shows a regressed germinal center surrounded by an expanded mantle zone (“onion skin”). The hyalinized vessel is penetrating small atrophic follicles. B: Expanded interfollicular zones show paracortical plasmacytosis. Some atypical binucleated forms and enlarged morphology are seen.

A B

HEAD AND NECK CLINIC

IRRIGATION. SUCTION. SYNCHRONIZATION.

Now there’s a better way to provide saline washes. The HydroCleanse™ Sinus Wash Delivery System from Medtronic combines pressurized sinus irrigation with builtin suction capability for a more efficient procedure. Disposable and easy to use, it allows you to irrigate the sinuses while limiting pooling and effluent discharge.

§ Disposable and easy to use

§ 360° fan spray

§ Pressurized saline irrigation

§ Built-in suction capability

§ Choice of angled catheter tips

HydroCleanse™ Sinus Wash Delivery System

IMPROVE THE SALINE WASH EXPERIENCE. CHOOSE HYDROCLEANSE.

Rx only. Refer to product instruction manual/package insert for instructions, warnings, precautions and contraindications.

For further information, please call Medtronic ENT at 800.874.5797 or consult Medtronic’s website at www.medtronicent.com.

© 2018 Medtronic. All rights reserved. Medtronic, Medtronic logo and Further, Together are trademarks of Medtronic. All other brands are trademarks of a Medtronic company. UC201902765 EN 07.2018

Fourth branchial pouch sinus: A report of 7 cases and review of the literature

Indranil Pal, MS; Saumitra Kumar, MS; Ankur Mukherjee, MS, DNB; Bibhas Mondal, MS; Anindita Sinha Babu, MD

Abstract

A fourth branchial pouch sinus often manifests quite late in life as a recurrent neck abscess, suppurative thyroiditis, or pseudothyroiditis. Demonstration of the sinus opening in the piriform fossa by hypopharyngoscopy in combination with ultrasonography of the neck provides adequate information to justify proceeding to surgery. The sinus tract usually courses through the thyroid cartilage. The most effective treatment is surgical excision of the tract up to the piriform fossa through the cartilage. This procedure is associated with very low complication and recurrence rates. A fourth branchial pouch sinus is an uncommon condition. Even so, it is still underdiagnosed as a result of poor awareness of its existence by medical practitioners, including otolaryngologists. Part of the reason is a lack of adequate coverage of this topic in otolaryngology and surgery textbooks. In this article, we add to the literature by describing our experience with 7 patients—4 males and 3 females, aged 5 to 45 years (mean: 25.6)—who were diagnosed with a fourth branchial pouch sinus over a 6-year period. The diagnosis was confirmed by identifying the sinus opening at the apex of the piriform sinus during hypopharyngoscopy. Definitive treatment consisted of surgical exploration of the neck and excision of the tract.

Introduction

Branchial cleft anomalies are not uncommon in clinical practice. Most of these (~95%) originate in the second branchial cleft.1 The remainder originate in the first, third, or fourth clefts.2

From the Department of Otorhinolaryngology (Dr. Pal, Dr. Kumar, Dr. Mukherjee, and Dr. Mondal) and the Department of Pathology (Dr. Babu), College of Medicine & JNM Hospital, West Bengal University of Health Sciences, Kalyani, Nadia, West Bengal, India.

Corresponding author: Dr. Indranil Pal, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, College of Medicine & JNM Hospital, West Bengal University of Health Sciences, Kalyani, Nadia, West Bengal 741235, India. Email: thisisindranil@yahoo.co.in

Fourth branchial cleft anomalies are rarely encountered, poorly understood, and often misdiagnosed. As a result, patients with this condition often undergo multiple consultations, referrals, and interventions before a definitive diagnosis is made and treatment instituted. The reason for this is a lack of awareness about this condition among the medical community— specifically, among otolaryngologists, general surgeons, and pediatricians, who are generally the first to attend these patients after referral by a general practitioner.

Fourth branchial pouch anomalies clinically manifest as a recurrent neck abscess, suppurative thyroiditis, or pseudothyroiditis.3 They are almost always located on the left side of the midline in the anterior part of the neck. They present as a sinus tract with a proximal opening in the floor of the piriform fossa; from there they extend upward for various distances in the neck.

In this article, we report our experience with 7 cases of fourth branchial pouch sinus, and we discuss their presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. We also discuss the possible reasons for delays in establishing a definitive diagnosis, and we offer our suggestions for making an early diagnosis.

Patients and methods

Patients. Over a period of 6 years at our institution, 7 patients—4 males and 3 females—were diagnosed with and operated on for a fourth branchial pouch sinus by the team of authors. For this study, we retrieved their medical records and compiled, in addition to the demographic data, information on their patient profile, their age at the onset of symptoms, the type of symptoms, the interval between symptom onset and the definitive diagnosis, the side of the sinus, the number of symptomatic episodes, and the number and type of previous surgical interventions performed before the definitive diagnosis was established.

Surgical procedure. All patients were treated under general anesthesia with surgical excision of the sinus

236 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal August 2018 ORIGINAL ARTICLE

RHINOWORLD CHICAGO June 6-9, 2019 Sheraton Grand Chicago THE PREMIER CONGRESS FOR RHINOLOGISTS Combined International Rhinology Meeting Robert Kern MD - 2019 ISIAN President Brent Senior MD - 2019 IRS President James Palmer MD - 2019 ARS President David Kennedy MD - ISIAN General Secretary Metin Onerci MD - IRS General Secretary Joseph Jacobs MD - ARS EVP For questions or more information visit RhinoWorld2019.com Contact: Wendi Perez, Executive Administrator, ARS +1-973-545-2735 ext. 6 | wendi@amrhso.com Polly Rossi, CMP-HC, CMM, Meeting Logistics +1-219-465-1115 | polly@meetingachievements.com Kevin Welch MD, Rakesh Chandra MD & David Conley MD - Program Chairs Featuring Pre-Course Dissections on June 5, 2019 SAVE THE DATE Registration opens October 1, 2018

tract through a neck incision. In the operating room, patients were placed in the supine position with the neck extended. An incision was made in equal lengths on both sides of the midline in a transverse neck crease roughly corresponding to the lower end of the lesion. Subplatysmal flaps were raised superiorly and inferiorly for adequate exposure. Superiorly, the exposure extended to the upper border of the thyroid cartilage. The strap muscles were retracted, and the upper pole of the thyroid lobe was exposed.

All the sinus tracts ended roughly at the upper pole of the thyroid gland. The sinus tract was identified and carefully dissected out. The recurrent laryngeal nerve was dissected if the sinus tract extended below the level of the cricothyroid joint. The superior laryngeal nerve was dissected and preserved whenever possible. Thyroid lobectomy was not required in any of our cases because the tract could be dissected free off the thyroid gland in all of them. The tract was then traced superiorly.

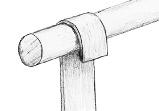

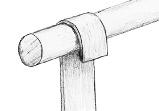

In all cases, the tract was found to pierce the thyroid cartilage at its lower end before opening into the piriform fossa. Therefore, a small sliver of thyroid cartilage was cut from the posterior border of the thyroid ala to trace the sinus tract up to the floor of the piriform fossa (figure 1). The tract was then excised as close to the piriform fossa as possible, and the stump was ligated with nonabsorbable sutures. The wound was then closed in layers. No drains were required.

Postoperative recovery was uneventful in all patients, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were the only necessary prescribed medications.

Results

Patients’ age at the onset of symptoms ranged from 3 to 40 years (mean: 20.3), and their age at diagnosis ranged from 5 to 45 years (mean: 25.6) (table 1).

The most common manifestation was recurrent neck abscess, which was seen in 5 of the 7 patients and which required multiple drainings. Recurrent thyroiditis or pseudothyroiditis was seen in 4 patients. One patient (patient 6) also had a pharyngeal fistula in addition to a recurrent abscess and thyroiditis; the fistula developed after she had undergone a total thyroidectomy at another institution for the treatment of suspected medullary thyroid cancer (table 1).

In all cases, the definitive diagnosis was made by viewing the sinus tract opening on the floor of the ipsilateral piriform sinus near its apex (figure 2). In the first 4 patients we tested, a barium swallow examination failed to demonstrate the sinus tract, even after the Valsalva maneuver, so we decided against administering a barium swallow test to the succeeding 3 patients.

Computed tomography (CT) was obtained in patients 1, 2, 3, and 4, followed by ultrasonography of the neck;

both demonstrated a hypodense area in relation to the thyroid gland. Since CT provided no information beyond what we saw on ultrasonography, we did not obtain CT in patients 5, 6, and 7, and we relied on just the ultrasonographic findings.

As described, definitive treatment entailed surgical exploration of the neck and excision of the tract. The tracts were easily dissected off the thyroid lobes, and thyroidectomy of any description was not required in any patient. Electrocautery was attempted in 3 patients (patients 1, 6, and 7), but it was unsuccessful in resolving the symptoms.

Follow-up ranged from 2 months to 6 years. No patient experienced any significant postoperative complications or recurrence (table 2).

Of the 7 patients, only 2 demonstrated the presence of lining epithelium, but all 7 exhibited inflammatory tissue and a tract lumen. The lining epithelium in both cases was stratified squamous epithelium; a focal presence of columnar epithelium was also seen in 1 of these 2 patients. However, even in the absence of any epithelial lining, the presence of a lumen and the preoperative demonstration of a tract opening in the piriform sinus left no doubt about the diagnosis.

238 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal August 2018

PAL, KUMAR, MUKHERJEE, MONDAL, BABU

Figure 1. The tract of the right-sided fourth branchial pouch sinus in patient 5 extends behind the ala of the thyroid cartilage and enters the apex of the piriform sinus. A sliver of thyroid cartilage was excised to trace the tract into the piriform fossa (SCM = sternocleidomastoid muscle).

Figure 2. Endoscopic views show the proximal openings of sinus tracts at the apex of the right piriform fossa (A) and the left piriform fossa (B)

Table 1. Clinical data obtained at presentation

Discussion

Although it is theoretically possible, the presence of a complete fourth branchial cleft or pouch fistula has never been demonstrated. It generally presents as a sinus with a proximal opening in the apex of the piriform fossa and with the distal end extending to any point along the theoretical extent of the tract—that is, beginning at the piriform fossa, passing between the thyroid (fourth arch) and cricoid (fifth arch) cartilages, descending between the superior laryngeal nerve and the cricothyroid muscle (fourth arch), and thereafter extending between the trachea and the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

The tract then loops around the aortic arch on the left side and around the subclavian artery on the right side and rises in the cervical area posterior to the common carotid artery. Then it loops over the hypoglossal nerve and finally descends and opens on the skin of the lower neck along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.4

Based on the difference between the theoretical course and the actual course of the sinus tract, Thomas et al suggested that the branchial sinuses arising from the piriform sinuses do not originate in the true third or fourth arch pouches but that they are sinuses arising from a patent thymopharyngeal duct.5 None of the fistulas described in their report were congenital; all were acquired secondary to infection and abscess formation, which was followed by spontaneous rupture or surgical drainage. The lone patient in our series who presented with a fistula had developed it secondary to a thyroidectomy performed at another hospital.

Lu et al suggested that there could be three different emerging pathways for the sinus tract from the piriform fossa.6 The tract could emerge by penetrating either the thyroid cartilage near the inferior cornu, the inferior constrictor muscle of the pharynx, or the cricothyroid membrane as it emerges from the pharynx. In our series, all seven tracts emerged by penetrating the thyroid

cartilage. This probably indicates that this is the most common course.

A third branchial pouch sinus is similar to a fourth branchial pouch sinus in its course and presentation. The difference is that the third pouch sinus opens in the cranial part of the piriform sinus, while the fourth opens more caudally at the apex of the piriform fossa.7 The third pouch sinus then courses superiorly through the thyrohyoid membrane cranial to the superior laryngeal nerve, posterior to the carotid vessels, and deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle.4 In our series, all the sinus tracts were located caudal to the superior laryngeal nerve, and all opened at the apex of the piriform sinus.

A fourth branchial pouch sinus, like most congenital conditions, is generally believed to manifest as symptoms during the first or second decade of life.8,9 In our series, however, only 3 of the 7 patients experienced an onset of symptoms within the first decade. In the other 4 patients, the initial symptoms manifested late—at the age of 20, 28, 37, and 40 years.

By far, most fourth branchial pouch sinuses occur on the left side, probably as a result of the asymmetry in vascular development in this arch.1 They are rarely seen on the right side, and there are only occasional reports of bilateral sinuses.10 In our series, only 1 of the 7 was located on the right side.

The most common presentation is recurrent deep neck infections, 3 followed by thyroiditis-like features (pseudothyroiditis).11 Two uncommon presentations that have been reported were stridor in a neonate12 and suspected esophageal perforation in a 14-year-old boy.13 Our study yielded similar findings, although we had the 1 case of iatrogenic fistula.

A fourth branchial pouch sinus should be high on the list of differential diagnoses for patients with recurrent thyroiditis or recurrent neck abscess, especially on the left side. The recommended investigations for confirming the diagnosis include a barium swallow examination, sonography with a Valsalva maneuver, fiberoptic

Volume 97, Number 8 www.entjournal.com 239 FOURTH BRANCHIAL POUCH SINUS: A REPORT OF 7 CASES AND REvIEw OF THE LITERATURE

Pt. Sex/age at presentation, yr Age at onset, yr Symptom Side Symptomatic episodes, n Previous surgeries, n 1 M/20 20 RT Left 2 0 2 F/5 3 RNA Left 4 3 3 M/45 40 RNA Left 5 2 4 M/10 8 RNA Left 3 1 5 M/30 28 RT + RNA Right 4 3 6 F/29 6 RT + RNA + fistula Left 6 5 7 F/40 37 RT Left 4 3

Key: RT = recurrent thyroiditis or pseudothyroiditis; RNA = recurrent neck abscess.

Table 2. Investigations, treatments, and outcomes

laryngoscopy, CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and hypopharyngoscopy under general anesthesia.

In our series, the most definitive diagnosis was made by viewing the sinus tract opening on the floor of the ipsilateral piriform sinus near its apex. Barium swallow examination failed to demonstrate the sinus tract, even after the Valsalva maneuver in our first 4 patients, so we decided against performing this test in the 3 patients who presented later. The reason for the low yield of barium swallow skiagrams is probably because they require a quiescence of inflammation of the tract for the entry of the barium contrast into the sinus.

CT was performed in our first 4 patients, and it demonstrated a hypodense area in relation to the thyroid gland. Ultrasonography of the neck was also performed on these 4 patients, and the findings were similar to those of CT. Since CT provided no additional information beyond what we saw on ultrasonography, we decided that it was unnecessary for the final 3 patients, and we used only the ultrasonographic findings. MRI was not available at our institution.

We believe that the demonstration of the sinus opening in the apex of the piriform sinus with a flexible fiberoptic laryngoscope or bronchoscope or with an upper gastrointestinal endoscope is a simple, highly sensitive, and highly specific procedure for confirming the diagnosis of a fourth branchial pouch sinus. We also conclude that ultrasonography of the neck performed by an experienced and competent radiologist is sufficient to identify the extent of the sinus tract. The two procedures together provide us with adequate information with which to proceed to surgery. Other radiologic investigations yielded little additional information over and above what these two procedures did.

The most noteworthy finding of our study was that almost all of our patients presented with two or more episodes of pseudothyroiditis or abscess in the neck that required multiple drainings. One of our patients (patient 6) had undergone five previous surgical interventions

at different hospitals, including a total thyroidectomy that led to the development of a nonhealing fistula in her neck, and yet a precise diagnosis was not made.

In an attempt to understand the low level of suspicion among physicians when it comes to recognizing and diagnosing fourth branchial pouch sinuses, we reviewed the world literature as available on PubMed. We found that the interval between the first appearance of symptoms and the final diagnosis ranged from 2 to 10 years,14,15 excluding neonatal presentations12,16 and incidental presentations.13 In a case published in 2012, a young boy experienced 10 episodes of neck abscess during a 10-year span, and he had undergone seven surgical interventions before a diagnosis was finally reached.6 This fact is astonishing given that more than 100 cases of fourth branchial sinus have been indexed on PubMed, with the first case having been reported more than 40 years ago.2

We also reviewed 6 reference books on otorhinolaryngology and head and neck surgery and found only 1 that contained a complete description, which consisted of 27 lines of text.17 We found 3 to 8 lines of text tucked away in four other books.18-21 We also checked 3 reference books in surgery along with 10 different textbooks used by undergraduate medical students in otorhinolaryngology, and none of them contained any mention of this condition. We believe that the description of this condition should not be limited to articles in peer-reviewed journals, but should be included in detail in all future textbooks, for undergraduates as well as for postgraduates, to raise the level of awareness of this condition.

The definitive treatment for a fourth branchial pouch sinus is an excision of the tract via a neck incision, sometimes accompanied by a hemithyroidectomy,6,9 an endoscopic transpharyngeal excision with a CO2 laser, 22 chemocauterization with 10% trichloroacetic acid, 23 endoscopic monopolar

240 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal August 2018

PAL, KUMAR, MUKHERJEE, MONDAL, BABU

diathermy,24 or

endoscopic tissue fibrin glue biocauterization.25

even KTP-laser–assisted

Pt. Scope findings* Site of tract exit Thyroid lobectomy Vocal fold paralysis Follow-up Recurrence 1 Opening identified Thyroid cartilage Not done No 6 yr No 2 Opening identified Thyroid cartilage Not done No 4 yr No 3 Opening identified Thyroid cartilage Not done No 3 yr No 4 Opening identified Thyroid cartilage Not done No 3 yr No 5 Opening identified Thyroid cartilage Not done No 2 yr No 6 Opening identified Thyroid cartilage Not done No 3 mo No 7 Opening identified Thyroid cartilage Not done No 2 mo No

* Hypopharyngoscopy.

www.macksearplugs.com *Independent research as completed by Business Research Group, February 2014. Pillow Soft® comfort only from Mack’s®, the original moldable silicone putty earplug. Mack’s ® is the #1 Doctor Recommended earplug brand to help prevent otitis externa and to get a good night’s sleep when sleeping with a snoring spouse.* Available at pharmacies.

We managed all of our patients with surgical excision of the tract through a neck incision. In all cases, we could dissect the sinus tract from the thyroid gland and surrounding tissues, and therefore we did not have to perform a thyroid lobectomy in any patient.

The sinus tract is said to be lined with columnar epithelium. In our series, most patients exhibited a denudation of the epithelial lining, owing to recurrent inflammation. Two of our patients had a stratified squamous epithelium. This might have been attributable to a metaplastic change in the normal columnar epithelial lining of the branchial sinus secondary to recurrent inflammation.3,26 In such a circumstance, histopathology provides little clue as to the diagnosis of a fourth branchial pouch sinus.

In conclusion, a fourth branchial pouch sinus is an uncommon yet underdiagnosed condition. Awareness of its existence is low, and thus so is a suspicion for it among medical practitioners, including otolaryngologists. The problem is compounded by a lack of adequate coverage of this topic in otorhinolaryngology and surgery textbooks, a deficiency that needs to be corrected in the future.

The most common presentation of this condition is a recurrent neck abscess on the left side. Symptoms often manifest quite late in life, unlike the case with most congenital sinuses, fistulae, and cysts.

A fourth branchial pouch sinus is best diagnosed by demonstration of the sinus opening in the piriform fossa. Hypopharyngoscopy in combination with ultrasonography of the neck provides adequate information with which to proceed to surgery.

The tract most commonly courses through the thyroid cartilage. Surgical excision of the tract up to the piriform fossa through the cartilage is the most effective treatment, and it is associated with very low complication and recurrence rates.

References

1. Rosenfeld RM, Biller HF. Fourth branchial pouch sinus: Diagnosis and treatment. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1991;105(1):44-50.

2. Tucker HM, Skolnick ML. Fourth branchial cleft (pharyngeal pouch) remnant. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 1973;77(5):ORL368-71.

3. Godin MS, Kearns DB, Pransky SM, et al. Fourth branchial pouch sinus: Principles of diagnosis and management. Laryngoscope 1990;100(2 Pt 1):174-8.

4. Liston SL. Fourth branchial fistula. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1981;89(4):520-2.

5. Thomas B, Shroff M, Forte V, et al. Revisiting imaging features and the embryologic basis of third and fourth branchial anomalies. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010;31(4):755-60.

6. Lu WH, Feng L, Sang JZ, et al. Various presentations of fourth branchial pouch sinus tract during surgery. Acta Otolaryngol 2012;132(5):540-5.

7. Franciosi JP, Sell LL, Conley SF, Bolender DL. Pyriform sinus malformations: A cadaveric representation. J Pediatr Surg 2002;37(3):533-8.

8. Yang C, Cohen J, Everts E, et al. Fourth branchial arch sinus: Clinical presentation, diagnostic workup, and surgical treatment. Laryngoscope 1999;109(3):442-6.

9. Madana J, Yolmo D, Kalaiarasi R, et al. Recurrent neck infection with branchial arch fistula in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2011;75(9):1181-5.

10. Rea PA, Hartley BE, Bailey CM. Third and fourth branchial pouch anomalies. J Laryngol Otol 2004;118(1):19-24.

11. Contencin P, Grosskopf-Aumont C, Gilain L, Narcy P. Recurrent pseudothyroiditis and cervical abscess. The fourth branchial pouch’s role. Apropos of 16 cases [in French]. Arch Fr Pediatr 1990;47(3):181-4.

12. Nathan K, Bajaj Y, Jephson CG. Stridor as a presentation of fourth branchial pouch sinus. J Laryngol Otol 2012;126(4):432-4.

13. Jeyakumar A, Hengerer AS. Various presentations of fourth branchial pouch anomalies. Ear Nose Throat J 2004;82(9):640-2, 644.

14. Mehrzad H, Georgalas C, Huins C, Tolley NS. A combined third and fourth branchial arch anomaly: Clinical and embryological implications. Eur Arch Otolaryngol 2007;264(8):913-16.

15. Hamoir M, Rombaux P, Cornu AS, Clapuyt P. Congenital fistula of the fourth branchial pouch. Eur Arch Otolaryngol 1998;255(6):322-4.

16. Leboulanger N, Ruellan K, Nevoux J, et al. Neonatal vs delayed-onset fourth branchial pouch anomalies: Therapeutic implications. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010;136(9):885-90.

17. Gleeson M, ed. Scott-Brown’s Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. 7th ed. London: Hodder Arnold; 2008:1779-80.

18. Bailey BJ, Johnson JT, Newlands SD, eds. Head & Neck Surgery–Otolaryngology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:1211.

19. Flint PW, Haughey BH, Lund VJ, John K, et al. Cummings Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:2585.

20. Wetmore RF, Muntz HR, McGill TJ. Pediatric Otolaryngology: Principles and Practice Pathways. 2nd ed. New York: Thieme; 2012:849-50.

21. Watkinson JC, Gilbert RW, eds. Stell & Maran’s Textbook of Head and Neck Surgery and Oncology. 5th ed. London: Hodder Arnold; 2012:222.

22. Parker KL, Clary MS, Courey MS. The endoscopic approach to a fourth branchial pouch sinus presenting in an adult. Laryngoscope 2013;123(11):2798-2800.

23. Stenquist M, Juhlin C, Aström G, Friberg U. Fourth branchial pouch sinus with recurrent deep cervical abscesses successfully treated with trichloroacetic acid cauterization. Acta Otolaryngol 2003;123(7):879-82.

24. Wong PY, Moore A, Daya H. Management of third branchial pouch anomalies—an evolution of a minimally invasive technique. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2014;78(3):493-8.

25. Huang YC, Peng SS, Hsu WC. KTP laser assisted endoscopic tissue fibrin glue biocauterization for congenital pyriform sinus fistula in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2016;85:115-19.

26. Takimoto T, Yoshizaki T, Ohoka H, Sakashita H. Fourth branchial pouch anomaly. J Laryngol Otol 1990;104(11):905-7.

242 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal August 2018

PAL, KUMAR, MUKHERJEE, MONDAL, BABU

Age-related changes affecting the cricoarytenoid joint seen on computed tomography

Georges Ziade, MD; Sahar Semaan, MD; Sarah Assaad, MPH; Abdul Latif Hamdan, MD, EMBA, MPH

Abstract

We conducted a retrospective chart review to compare four characteristics—cricoarytenoid joint ankylosis, narrowing, erosion, and density increases—in patients younger and older than 65 years. Our study population was made up of 100 patients, who were divided into two groups on the basis of age. The younger group (<65 yr) comprised 49 patients (27 men and 22 women), and the older group (≥65 yr) was made up of 51 patients (25 men and 26 women). Findings on computed tomography (CT) of the neck were used to determine whether each of the four characteristics was present or absent. Overall, we found only one statistically significant difference between the two groups: ankylosis was significantly more common in the older group (p = 0.036). When we looked further at the side of these anatomic changes, we found that the older group had significantly more right-sided and left-sided ankylosis than did the younger group (p = 0.026 for both), as well as significantly more left-sided narrowing (p = 0.028) (some patients had bilateral involvement). When we analyzed age as a continuous variable, older age was again associated with significantly more ankylosis (p = 0.047) and narrowing (p = 0.011). We conclude that CT can be useful for assessing radiologic changes in the cricoarytenoid joint in elderly patients during the workup of dysphonia and abnormal movement of the vocal folds.

Introduction

With age, many changes affect the laryngeal structures; among them are the cricoarytenoid joints. These diarthrodial joints are formed by the articular facets of both the cricoid and arytenoid cartilages apposed in a multiaxial form.1 In the elderly—which for the purposes of this study we defined as those aged 65 years and older—the articulation begins eroding and the perichondrium becomes thicker, which affects the precise movement of the arytenoid cartilages over the cricoid cartilage and alters the position of the vocal folds during phonation. These histologic and structural changes result in a change in voice quality.2-4

Among the different laryngeal imaging modalities, computed tomography (CT) is the best for assessing the cricoarytenoid joint. With its rapid image acquisition and low susceptibility to artifact induced by breathing and swallowing, it is considered by many to be the standard diagnostic imaging study for the evaluation of organic voice disorders.5 Modern CT scanners allow for a reconstruction of high-quality images in multiple planes and orientations, and they provide excellent spatial resolution.5