Post-turbinectomy nasal packing with Merocel versus glove finger Merocel: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial

Comparison of anterior palatoplasty and uvulopalatal flap placement for treating mild and moderate obstructive sleep apnea

Psoriasis, chronic tonsillitis, and biofilms: Tonsillar pathologic findings supporting a microbial hypothesis

Quality of life in patients with larynx cancer in Latin America: Comparison between laryngectomy and organ preservation protocols

www.entjournal.com A Vendome Publication MARCH 2018 • VOL. 97, NO. 3

EDITORIAL BOARD

EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS

Editor-in-Chief

Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS

Professor and Chairman, Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, and Senior Associate Dean for Clinical Academic Specialties, Drexel University College of Medicine Philadelphia, PA

Jean Abitbol, MD

Jason L. Acevedo, MD, MAJ, MC, USA

Jack B. Anon, MD

Gregorio Babighian, MD

Peter C. Belafsky, MD, PhD

Bruce Benjamin, MD

Gerald S. Berke, MD

Michael J. Brenner, MD

Kenneth H. Brookler, MD

Karen H. Calhoun, MD

Steven B. Cannady, MD

Ricardo Carrau, MD

Swapna Chandran, MD

Chien Chen, MD

Dewey A. Christmas, MD

Nicolle T. Clements, MS

Daniel H. Coelho, MD, FACS

David M. Cognetti, MD

Maura Cosetti, MD

James V. Crawford, MD

David H. Darrow, MD, DDS

Rima Abraham DeFatta, MD

Robert J. DeFatta, MD, PhD

Hamilton Dixon, MD

Paul J. Donald, MD, FRCS

Mainak Dutta, MS, FACS

Russell A. Faust, PhD, MD

Ramón E. Figueroa, MD, FACR

Charles N. Ford, MD

Paul Frake, MD

Marvin P. Fried, MD

Richard R. Gacek, MD

Andrea Gallo, MD

Frank Gannon, MD

Emilio Garcia-Ibanez, MD

Soha Ghossani, MD

William P. R. Gibson, MD

David Goldenberg, MD

Jerome C. Goldstein, MD

Richard L. Goode, MD

Samuel Gubbels, MD

Reena Gupta, MD

Joseph Haddad Jr., MD

Missak Haigentz, MD

Christopher J. Hartnick, MD

Mary Hawkshaw, RN, BSN, CORLN

Garett D. Herzon, MD

Thomas Higgins, MD, MSPH

Jun Steve Hou, MD

John W. House, MD

Glenn Isaacson, MD

Steven F. Isenberg, MD

Stephanie A. Joe, MD

Shruti S. Joglekar, MBBS

Raleigh O. Jones, Jr., MD

Petros D. Karkos, MD, AFRCS, PhD, MPhil

David Kennedy, MD

Seungwon Kim, MD

Robert Koenigsberg, DO

Karen M. Kost, MD, FRCSC

Jamie A. Koufman, MD

Stilianos E. Kountakis, MD, PhD

John Krouse, MD

Ronald B. Kuppersmith, MD, MBA, FACS

Rande H. Lazar, MD

Robert S. Lebovics, MD, FACS

Keat-Jin Lee, MD

Donald A. Leopold, MD

Steve K. Lewis, BSc, MBBS, MRCS

Daqing Li, MD

Robert R. Lorenz, MD

John M. Luckhurst, MS, CCC-A

Valerie Lund, FRCS

Karen Lyons, MD

A.A.S. Rifat Mannan, MD

Richard Mattes, PhD

Brian McGovern, ScD

William A. McIntosh, MD

Brian J. McKinnon, MD

Oleg A. Melnikov, MD

Albert L. Merati, MD, FACS

Joseph P. Mirante, MD, MBA, FACS

Ron B. Mitchell, MD

Steven Ross Mobley, MD

Jaime Eaglin Moore, MD

Thomas Murry, PhD

Ashli K. O’Rourke, MD

Ryan F. Osborne, MD, FACS

J. David Osguthorpe, MD

Robert H. Ossoff, DMD, MD

Enrique Palacios, MD, FACR

Michael M. Paparella, MD

Kourosh Parham, MD, PhD

Arthur S. Patchefsky, MD

Meghan Pavlick, AuD

Spencer C. Payne, MD

Kevin D. Pereira, MD, MS (ORL)

Nicolay Popnikolov, MD, PhD

Didier Portmann, MD

Gregory N. Postma, MD

Matthew J. Provenzano, MD

Hassan H. Ramadan, MD, FACS

Richard T. Ramsden, FRCS

Gabor Repassy, MD, PhD

Dale H. Rice, MD

Ernesto Ried, MD

Alessandra Rinaldo, MD, FRSM

Joshua D. Rosenberg, MD

Allan Maier Rubin, MD, PhD, FACS

John S. Rubin, MD, FACS, FRCS

Amy L. Rutt, DO

Anthony Sclafani, MD, FACS

Raja R. Seethala, MD

Jamie Segel, MD

Moncef Sellami, MD

Michael Setzen, MD, FACS, FAAP

Stanley Shapshay, MD

Douglas M. Sidle, MD

Herbert Silverstein, MD

Jeffrey P. Simons, MD

Raj Sindwani, MD, FACS, FRCS

Aristides Sismanis, MD, FACS

William H. Slattery III, MD

Libby Smith, DO

Jessica Somerville, MD

Thomas C. Spalla, MD

Matthew Spector, MD

Paul M. Spring, MD

Brendan C. Stack, Jr., MD, FACS

James A. Stankiewicz, MD

Jun-Ichi Suzuki, MD

David Thompson, MD

Lester D.R. Thompson, MD, FASCP

Helga Toriello, PhD, FACMG

Ozlem E. Tulunay-Ugur, MD

Galdino Valvassori, MD

Emre Vural, MD

Donald T. Weed, MD, FACS

Neil Weir, FRCS

Kenneth R. Whittemore, MD

David F. Wilson, MD

Ian M. Windmill, PhD

Ian J. Witterick, MD,MSc, FRCSC

Richard J. Wong, MD

Naoaki Yanagihara, MD

Eiji Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

Ken Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

Anthony Yonkers, MD

Mark Zacharek, MD

Joseph Zenga, MD

Liang Zhou, MD

CLINIC EDITORS

Dysphagia

Jamie A. Koufman, MD

Peter C. Belafsky, MD, PhD

Gregory N. Postma, MD

Facial Plastic Surgery

Anthony P. Sclafani, MD, FACS

Geriatric Otolaryngology

Kourosh Parham, MD, PhD, FACS

Karen M. Kost, MD, FRCSC

Head and Neck

Ryan F. Osborne, MD, FACS

Paul J. Donald, MD, FRCS

Reena Gupta, MD

Imaging

Enrique Palacios, MD, FACR

Ramón E. Figueroa, MD, FACR

Laryngoscopic

Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS

Otoscopic

John W. House, MD

Brian J. McKinnon, MD

Pathology

Lester D.R. Thompson, MD, FASCP

Pediatric Otolaryngology

Rande H. Lazar, MD

Rhinoscopic

Eiji Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

Dewey A. Christmas, MD

Joseph P. Mirante, MD, MBA, FACS

Ken Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

Special Topics

Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS

Thyroid and Parathyroid

David Goldenberg, MD

42 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal March 2018

Editor-in-Chief Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS 219 N. Broad St., 10th Fl., Philadelphia, PA 19107 entjournal@phillyent.com Ph: 215-732-6100

Managing Editor Linda Zinn

Manuscript Editors Martin Stevenson and Wayne Kuznar

Associate Editor, Reader Engagement Megan Combs

Creative Director Eric Collander

National Sales Manager Mark C. Horn mhorn@vendomegrp.com Ph: 480-895-3663

Traffic Manager Judi Zeng

Please send IOs to adtraffic@vendomegrp.com

All ad materials should be sent electronically to: https://vendome.sendmyad.com

Customer Service/Subscriptions

www.entjournal.com/subscribe Ph: 888-244-5310 email: VendomeHM@emailpsa.com

Reuse Permissions Copyright Clearance Center info@copyright.com Ph: 978-750-8400 Fax: 978-646-8600

Chief Executive Officer Jane Butler

Chief Marketing Officer Dan Melore

Vice President, Finance Bill Newberry

Vice President, Custom Media Jennifer Turney Director, Circulation Rachel Beneventi

ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal (ISSN: Print 0145-5613, Online 1942-7522) is published 9 times per year in Jan/Feb, Mar, Apr/May, June, July, Aug, Sept, Oct/ Nov and Dec, by Vendome Group, LLC, 237 West 35th Street, 16th Floor, New York, NY 10001-1905.

©2018 by Vendome Group, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal may be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast in any form or in any media without prior written permission of the publisher. To request permission to reuse this content in any form, including distribution in education, professional, or promotional contexts or to reproduce material in new works, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center at info@ copyright.com or 978.750.8400.

EDITORIAL: The opinions expressed in the editorial and advertising material in this issue of ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal are those of the authors and advertisers and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or recommendations of the publisher, editors, or the staff of Vendome Group, LLC. ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal is indexed in MEDLINE/PubMed and Current Contents/Clinical Medicine and Science Citation Index Expanded. Editorial offices are located at 812 Huron Rd., Suite 450, Cleveland, OH 44115. Manuscripts should be submitted online at www.editorialmanager. com/entjournal. Instructions for Authors are available at www.entjournal. com.

SUBSCRIPTIONS: For questions about a subscription or to subscribe, please contact us by phone: 888-244-5310; or email: VendomeHM@emailpsa.com. Individual subscriptions, U.S. and possessions: 1 year $225, 2 years $394; International: 1 year $279, 2 years $488; Single copies $28; outside the U.S., $40.

POSTMASTER: send address changes to Ear, Nose & Throat Journal, PO Box 11404 Newark, NJ 07101-4014.

44 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal March 2018

ADVERTISER INDEX Pages American Rhinologic Society 45 Arbor Pharmaceuticals ...................... 85, 86 Beutlich Pharmaceuticals, LLC ............... 95 CANT Corporation 49 Compulink Business Systems ................. 81 Cook Medical 59 Eagle Surgical Products LLC 53 Eosera, Inc......................................... CVR 3 Fyzical Therapy and Balance 41 Haag-Streit .............................................. 67 InHealth Technologies ............................. 47 Lannett Company 71, 72 Lumenis Ltd. ............................................ 89 McKeon Products, Inc. ...................... CVR 4 Optim LLC 43 Optinose ............................................ 75, 77 Reliance Medical 61 Spectrum Audiology ................................ 56 SurgiTel .............................................. CVR 2 Xlear, Inc. 51 Xoran Technologies ................................. 93

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

64 Post-turbinectomy nasal packing with Merocel versus glove finger Merocel: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial

Rani Abu Eta, MD; Ephraim Eviatar, MD; Jacob Pitaro, MD; Haim Gavriel, MD

69 Comparison of anterior palatoplasty and uvulopalatal flap placement for treating mild and moderate obstructive sleep apnea

Süheyl Hayto lu, MD; Osman Kür at Arikan, MD; Nuray Bayar Muluk, MD; Birgül Tuhanio lu, MD; Mustafa Çörtük, MD

79 Psoriasis, chronic tonsillitis, and biofilms: Tonsillar pathologic findings supporting a microbial hypothesis

Herbert B. Allen, MD; Saagar Jadeja, BS; Rina M. Allawh, MD; Kavita Goyal, MD

83 Quality of life in patients with larynx cancer in Latin America: Comparison between laryngectomy and organ preservation protocols

Alvaro Sanabria, MD, PhD, FACS; Daniel Sánchez, MD; Andrés Chala, MD; Andres Alvarez, MD

91 “Split to save”: Accessing mandibular lesions using sagittal split osteotomy with virtual surgical planning

Stanley Yung-Chuan Liu, MD, DDS; Douglas Sidell, MD; Leh-Kiong Huon, MD; Carlos Torre, MD

ONLINE EXCLUSIVES

E1 Relationship between dysarthria and oraloropharyngeal dysphagia: The current evidence

Brandon J. Wang, BA, BBA; Felicia L. Carter, MA, CCC-SLP; Kenneth W. Altman, MD, PhD

E10 Prospective evaluation of the early effects of radiation on the auditory system frequencies of patients with head and neck cancers and brain tumors after radiotherapy

Akram Hajisafari, Msc; Mohsen Bakhshandeh, PhD;

Seyed Mahmoud Reza Aghamiri, PhD;

Mohammad Houshyari, MD; Afshin Rakhsha, MD;

Eftekhar Rajab Bolokat, Msc; Abbas Rezazadeh, PhD

E18 Pharyngeal pack placement in minor oral surgery: A prospective, randomized, controlled study

Badr A. Al-Jandan, FRCD(C);

Faiyaz Ahmed Syed, MDS; Ahed Zeidan, MD; Hesham Fathi Marei, MSc, MFDS (RCS Eng), PhD; Imran Farooq, MSc

E22 Aerophagia and subcutaneous emphysema in a patient with Rett syndrome

Christine M. Clark, MD; Shivani Shah-Becker, MD; Abraham Mathew, MD; Neerav Goyal, MD, MPH

E25 Alternative therapies for chronic rhinosinusitis: A review

Aaron S. Griffin, MBBS, BSci; Peter Cabot, PhD, BSci; Ben Wallwork, PhD, MBBS, FRACS; Ben Panizza, MBA, MBBS, FRACS

E34 CO2-laser–assisted diverticulotomy remains an effective and safe method for treating Zenker diverticulum

Mazin Merdad, MD, MPH; Nitin Bhatia, MD; Elie E. Rebeiz, MD, FACS

E38 Bilateral pyriform sinus parathyroid adenomas

Thomas Muelleman, MD; Sreeya Yalamanchali, MD; Yelizaveta Shnayder, MD

E41 The utility of enlarging symptomatic nasal septal perforations

Philip G. Chen, MD; Stephen Floreani, MBBS; Peter-John Wormald, MD

E44 Incidence of epistaxis after endoscopic pituitary surgery: Proposed treatment algorithm

Lee A. Zimmer, MD, PhD; Norberto Andaluz, MD

46 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal March 2018 EDITORIAL OFFICE Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS, Editor-in-Chief • 219 N. Broad St., 10th Fl. • Philadelphia, PA 19107 CONTENTS MARCH 2018 • VOL. 97, NO. 3

DEPARTMENTS 44 Advertiser Index 48 ENT Journal Online 50 Editorial 54 Otoscopic Clinic 55 Imaging Clinic 57 Pathology Clinic 58 Thyroid and Parathyroid Clinic 62 Special Topics Clinic E49 Laryngoscopic Clinic E51 Rhinoscopic Clinic

JOURNAL ONLINE

Ear, Nose & Throat Journal's website is easy to navigate and provides readers with more editorial content each month than ever before. Access to everything on the site is free of charge to physicians and allied ENT professionals. To take advantage of all our site has to offer, go to www.entjournal. com and click on the "Registration" link. Once you have filled out the brief registration form, you will have full access. Explore and enjoy!

ONLINE EXCLUSIVES

Relationship between dysarthria and oraloropharyngeal dysphagia: The current evidence

Brandon J. Wang, BA, BBA; Felicia L. Carter, MA, CCC-SLP; Kenneth W. Altman, MD, PhD

There is a high prevalence of dysphagia among patients with neuromuscular diseases and cerebrovascular diseases, and its consequences can be profound. However, the correlation between dysarthria and oral-oropharyngeal dysphagia remains unclear. We conducted a literature review to define the clinical presentation of both dysarthria and dysphagia in patients with neuromuscular and cerebrovascular diseases. We performed a systematic PubMed search of the English-language literature since 1995. Objective and subjective outcomes instruments were identified for both dysarthria and dysphagia. Studies that included....

Prospective evaluation of the early effects of radiation on the auditory system frequencies of patients with head and neck cancers and brain tumors after radiotherapy

Akram Hajisafari, Msc; Mohsen Bakhshandeh, PhD; Seyed Mahmoud Reza Aghamiri, PhD; Mohammad Houshyari, MD; Afshin Rakhsha, MD; Eftekhar Rajab Bolokat, Msc; Abbas Rezazadeh, PhD

Patients with head and neck cancer after radiotherapy often suffer disability such as hearing disorders. In this study, the effect of radiotherapy (RT) on hearing function of patients with head and neck cancer after RT was determined according to the total dose delivered to specific parts of the auditory system. A total of 66 patients treated with primary or postoperative radiation therapy for various cancers....

Pharyngeal pack placement in minor oral surgery: A prospective, randomized, controlled study

Badr A. Al-Jandan, FRCD(C);

Faiyaz Ahmed Syed, MDS; Ahed Zeidan, MD; Hesham Fathi Marei, MSc, MFDS (RCS Eng), PhD;

Imran Farooq, MSc

We conducted a prospective, randomized, controlled study to investigate the influence of pharyngeal pack placement on postoperative nausea, vomiting, and throat pain after minor oral surgery. Our study group was made up of 80 patients—45 men and 35 women, aged 19 to 52 years (mean: 27.3)—who underwent a minor oral surgical procedure under general anesthesia. Patients were randomly assigned to one of three groups: 20 patients who received a pharyngeal pack under videolaryngoscopic guidance....

Aerophagia and subcutaneous emphysema in a patient with Rett syndrome

Christine M. Clark, MD; Shivani Shah-Becker, MD; Abraham Mathew, MD; Neerav Goyal, MD, MPH

A patient with Rett syndrome presented to our Emergency Department with extensive subcutaneous emphysema in the cervical region, chest wall, upper extremities, and back. Diagnostic evaluation revealed a mucosal tear in the posterior pharyngeal wall and an abscessed retropharyngeal lymph node, but she had no known history of trauma to account for these findings. This report discusses the occurrence of subcutaneous emphysema in the context of a rare neurodevelopmental disorder and proposes accentuated aerophagia, a sequela of Rett syndrome, as the most likely underlying mechanism.

Alternative therapies for chronic rhinosinusitis: A review

Aaron S. Griffin, MBBS, BSci; Peter Cabot, PhD, BSci; Ben Wallwork, PhD, MBBS, FRACS; Ben Panizza, MBA, MBBS, FRACS

The use of alternative medicine in chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) continues to increase in popularity, for the most part without meeting the burden of being based on sound clinical evidence. New and emerging treatments, both natural and developed, are numerous, and it remains a challenge for otolaryngologists as well as general practitioners to keep up to date with these therapies and their efficacy. In this systematic review, we discuss a number of alternative therapies for CRS, their proposed physiologic mechanisms, and evidence supporting their use. This analysis is based on....

CO2-laser–assisted diverticulotomy remains an effective and safe method for treating Zenker diverticulum

Mazin Merdad, MD, MPH; Nitin Bhatia, MD; Elie E. Rebeiz, MD, FACS

Our objectives were to review our experience with laserassisted diverticulotomy (LAD) in the treatment of Zenker diverticulum (ZD) and compare our results with those in published literature on other endoscopic and surgical techniques. We conducted a retrospective chart review of 57 patients who underwent LAD treatment of ZD in a single tertiary care institution. Data on surgical complications, length of stay, and follow-up were collected. Age ranged from 56 to 89 years. Endoscopic exposure of the diverticulum was not possible in 2 patients. All 55....

48 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal March 2018 www.entjournal.com

Bilateral pyriform sinus parathyroid adenomas

Thomas Muelleman, MD; Sreeya Yalamanchali, MD; Yelizaveta Shnayder, MD

Parathyroid glands undergo a variable descent during embryologic development and can be found anywhere in the neck from the level of the mandible to the mediastinum. To the best of our knowledge, we present the first report of a patient who was found to have bilateral parathyroid adenomas in her pyriform sinuses. A middle-aged woman with renal failure and secondary hyperparathyroidism presented with dysphagia and was found to have bilateral....

The utility of enlarging symptomatic nasal septal perforations

Philip G. Chen, MD; Stephen Floreani, MBBS; Peter-John Wormald, MD

Nasal septal perforations cause a subset of patients to suffer with significant impairments in quality of life. While smaller perforations can often be surgically repaired, perforations exceeding 2 cm are challenging to close. These repairs are highly technical, and there is a lack of consensus regarding the most effective means to do so. The authors performed a retrospective chart review of patients with....

Incidence of epistaxis after endoscopic pituitary surgery: Proposed treatment algorithm

Lee A. Zimmer, MD, PhD; Norberto Andaluz, MD

Endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary tumors is an increasingly common practice. Little has been reported on the incidence and treatment of postoperative epistaxis in this population. The aim of this study was to analyze the incidence of postoperative epistaxis and formulate a treatment algorithm based on our experience. We performed a case series with chart review. A total of 434 consecutive patients who had endoscopic transsphenoidal pituitary surgery were identified between April 2006 and November 2013. The incidence, clinical management, and outcomes were recorded. Based on the data, a treatment algorithm....

ONLINE DEPARTMENTS

Laryngoscopic Clinic: Reinke edema

Jessie C. Everaert, BS; Jonathan J. Romak, MD; Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS

Rhinoscopic Clinic: Endoscopic findings of bilateral fungal balls

Jong Seung Kim, MD; Sam Hyun Kwon, MD, PhD

Volume 97, Number 3 www.entjournal.com 49 ENT JOURNAL ONLINE

Geriatric surgery in otolaryngology

More than one-third of all inpatient surgical procedures are performed on patients age 65 and over.1 This is not surprising. In 2015, people ≥65 years constituted 15% of the U.S. population, and this percentage is expected to grow to 24% by 2060.2 In 2010, nearly 40% of hospital discharges (including short-stay hospitals) involved patients ≥65 years of age.3 This means that approximately 200 million operations a year are performed on elderly (≥65 years) patients. While these data are not specific to otolaryngology, it is likely that the age profile of our patients is similar; and, with changing population demographics, it is certain that the percentage of otolaryngology patients who are elderly will increase.

We have been trained to understand that pediatric patients are not just “small adults.” Similarly, geriatric patients are not just “old adults.” They have special problems and require knowledgeable diagnostic and therapeutic intervention. The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery acknowledged the importance of geriatric otolaryngology by publishing with Thieme a multidisciplinary textbook of geriatric otolaryngology–head and neck surgery in 2015.4 That text makes it clear that special knowledge of geriatric otolaryngology is important in all subspecialties except pediatric otolaryngology, and such knowledge is especially important in surgical decision making.

On one hand, surgery should not be denied to patients simply because they are “old.” Moreover, “old” is hard to define. More and more people are living beyond 100 years, so denying surgery to an 80-year-old and condemning him/her to suffer from a potentially correctable problem for another 15 to 20 years is not right. We need to be concerned about quality of life. On the other hand, surgery that is unlikely to improve quality of life, or that presents a high risk of ending life without a concomitant benefit (such as some surgery for advanced head and neck cancer), might not be appropriate in this population.

Numerous articles on surgery in the elderly have been published—far too many to reference in an editorial. Discussions of this topic appear regularly in publications of the American College of Surgeons, for example. The underlying theme of most of these articles is the need to improve preoperative assessment. Surgical decision making must focus on more than surgical mortality and morbidity. We must consider maintenance of independence, quality of life, return to at least preoperative functional activity levels, the likely consequences of each person’s physiologic reserve, the cognitive effects associated with general anesthesia in the elderly, and the patient’s desires regarding quality of life and longevity.

Ideally, with the help of a healthcare team, the surgeon needs to consciously assess cognitive function, nutrition, risk of falls, geriatric syndromes, and other special healthcare issues in all elderly patients for whom surgery is contemplated. Such preoperative assessments help not only in surgical decision making, but also in perioperative care of elderly patients.

50 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal March 2018

EDITORIAL

Elderly patients have increased risk of postoperative morbidity, sometimes after even relatively short general anesthesia. Problems may include long-term cognitive impairment, delirium, deep vein thrombosis, myocardial ischemia, infection, and others. It is essential for the physician, patient, and family to review these risks and make sure everyone agrees that they are justified and weighed against potential benefits. Physician and patient education are required, but much of the necessary knowledge is still being developed.

While there is no specific measure that will guide us in decisions about whether to perform surgery, assessments of frailty can be helpful and enlightening. This topic, as well as other tools for clinical assessment that predict adverse outcomes in geriatric patients, is covered in other literature.4-10 Interesting studies in geriatric trauma patients have shown the value of frailty assessment. For example, Joseph et al looked at elderly trauma patients (a particularly vulnerable population) and found that a 50-variable frailty index predicted unfavorable discharge disposition in geriatric patients.11 In a follow-up paper published during the same year, they validated a 15-variable trauma-specific frailty index (TSFI).12 The TSFI proved to be an effective instrument for predicting discharge disposition in geriatric trauma patients. Similar studies in otolaryngology patients have not been performed. Other frailty instruments have been used to predict surgical survival and outcomes, although most otolaryngologists are not using frailty assessment routinely and knowledgably. There are exceptions, such as the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, where targeted assessments of elderly patients have shown great value.

Nearly all otolaryngologists care for elderly patients, and the percentage of elderly patients in our practices will continue to increase. As a field, it is past time for us to study otolaryngology-specific implications of advanced age, to apply and study assessment tools that have proven useful in other specialties, and to develop assessments and guidelines of our own to assist our trainees and our patients in providing optimal care for patients 65 and older.

References

1. Hall MJ, DeFrances CJ, Williams SN, et al. National Hospital Discharge Survey: 2007 summary. National Health Statistics Reports. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. October 26, 2010. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr029.pdf. Accessed Jan. 26, 2018.

2. U.S. Census Bureau. 2014 national population projections summary tables. Table 6: Percent distribution of the projected population by sex and selected age groups for the U.S.: 2015 to 2060. www. census.gov/data/tables/2014/demo/popproj/2014-summarytables.html. Accessed Jan. 26, 2018.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Number of discharges from short-stay hospitals, by first-listed diagnosis and age: United States, 2010. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhds/3firstlisted/2010first3_ numberage.pdf. Accessed Jan. 26, 2018.

4. Sataloff RT, Johns MM, Kost KM (eds.) Geriatric Otolaryngology. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers and the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery; 2015.

5. Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: Implications for pay for performance. JAMA 2005;294(6):716-24.

6. Woods NF, LaCroix AZ, Gray SL, et al. Frailty: Emergence and consequences in women aged 65 and older in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53(8): 1321-30.

7. Fried LP, Kronmal RA, Newman AB, et al. Risk factors for 5-year mortality in older adults: The Cardiovascular Health Study. JAMA 1998;279(8):585-92.

8. Zafonte RD, Hammond FM, Mann NR, et al. Relationship between Glasgow Coma scale and functional outcome. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1996;75(5):364-9.

9. Foreman BP, Caesar RR, Parks J, et al. Usefulness of the abbreviated injury score and the injury severity score in comparison to the Glasgow Coma Scale in predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury. J Trauma 2007;62(4):946-50.

10. Shah MK, Al-Adawi S, Burke DT. Age as predictor of functional outcome in anoxic brain injury. J Appl Res 2004;4(3):380-4.

11. Joseph B, Pandit V, Rhee P, et al. Predicting hospital discharge disposition in geriatric trauma patients: Is frailty the answer? J Trauma Acute Care Surgery 2014;76(1):196-200.

12. Joseph B, Pandit V, Zangbar B, et al. Validating trauma-specific frailty index for geriatric trauma patients: A prospective analysis. J Am Coll Surg 2014;219(1):10-17.

Robert T. Sataloff, MD, DMA, FACS Editor-in-Chief

Ear, Nose & Throat Journal

52 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal March 2018 EdITORIAL

OTOSCOPIC CLINIC

Schwartze sign

Kevin A. Peng, MD; John W. House, MD

A 34-year-old man presented to the otology clinic complaining of right progressive hearing loss over the previous 4 years. Otoscopic examination revealed a reddish blush visible on the cochlear promontory beyond an intact right tympanic membrane (figure 1). Both 512- and 1024-Hz tuning forks lateralized to the right ear, and bone conduction was greater than air conduction on the right using both tuning forks. Audiometry revealed a moderate conductive hearing loss on the right with absent reflexes.

Computed tomography (CT) was performed, revealing demineralization at the fissula ante fenestram bilaterally (figure 2). At the time of surgery, a fixed stapes was noted, confirming the clinical diagnosis of otosclerosis.

Hermann Schwartze (1837-1910) was a German otologist at the University of Halle. In 1878, he published The Pathological Anatomy of the Ear, a comprehensive

From House Clinic, Los Angeles, Calif.

text cataloging diseases of the outer, middle, and inner ear.1 Although ankylosis of the stapes was discussed in his book, several years would pass before Politzer coined the term otosclerosis in 1893.2

It remains unclear when Schwartze first noted the red discoloration of the cochlear promontory now associated with his name, but by 1960, the Schwartze sign had become common parlance in otolaryngology publications. It is estimated to affect fewer than 10% of patients with otosclerosis, and it reflects the increased vascularity of otospongiotic bone in the otic capsule.

References

1. Schwartze H, Green JO. The Pathological Anatomy of the Ear. Boston: Houghton, Osgood and Co.; 1878.

2. Mudry A. Adam Politzer (1835-1920) and the description of otosclerosis. Otol Neurotol 2006;27(2):276-81.

54 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal March 2018

Figure 1. Otoscopy of the right tympanic membrane demonstrates a reddish blush on the cochlear promontory.

Figure 2. CT demonstrates demineralization at the fissula ante fenestram on the right, which is present bilaterally.

IMAGING CLINIC

An atypical presentation of hemifacial spasm secondary to neurovascular compression

Hemifacial spasm, also called tic convulsive, is a painless, involuntary contraction of the muscles innervated by the ipsilateral facial nerve, although less commonly it can present with weakness.1,2 As is the case in its trigeminal counterpart, tic douloureux, hemifacial spasm has a diverse array of potential etiologies. The most widely accepted of these is neurovascular compression, first proposed by Schultze.3 Other documented causes include space-occupying lesions, traumatic injury, and Bell palsy.1

Our case involved a 57-year-old man presenting with weakness of the left face for the previous 18 months with acute worsening over the course of that day. Transient ischemic attack was ruled out, although a vascular loop of the ipsilateral vertebral artery was observed on magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) of the brain to be impinging on the facial nerve (figure). The patient was treated with muscle relaxants with some relief of the symptoms, and he was discharged to be followed for further evaluation of the symptoms.

Hemifacial spasm affects 0.8/100,000 people.1 It presents most often in the fifth to sixth decades of life and is nearly twice as common in females.4,5 Symptoms typically manifest initially in the orbicularis oculi and progress downward, although 4% progress in the opposite direction.1 With its nonspecific symptomatology, the differential diagnosis for hemifacial spasm is wide and includes facial tic, myokymia, blepharospasm, and tardive dyskinesia.6

Diagnostic workup for hemifacial spasm consists of a complete neurologic exam, electromyography, mag-

netic resonance (MR) imaging, and MRA.3 Botulinum toxin injection and microvascular decompression are the mainstays of treatment.4 Symptoms are controlled

From the Department of Radiology, Head and Neck Section, Tulane University Medical Center, New Orleans.

Volume 97, Number 3 www.entjournal.com 55

Enrique Palacios, MD, FACR; Radia Ksayer, MD; Jeremy Nguyen, MD

A B C D

Figure. Noncontrast MR examination at the level of the cerebellopontine angle reveals a vascular loop corresponding to the distal portion of the left vertebral artery, compressing the area at the origin of the left facial nerve at the pontomedullary junction (A and B). In the axial (C) and coronal (D) T2W images, the arrows point to the flow void of the vessel. In the axial image of the source angiogram (C) and in the coronal view of the time-of-flight image (D), the arrows identify the vessel to better advantage than in A and B. The thin arrow in panel C identifies the left anterior inferior cerebellar artery.

acutely with anticonvulsants, muscle relaxants, and benzodiazepines.7

Visualization of the vascular structure and the nerve is best achieved in oblique sagittal gradient MR imaging, which is reported to have a 75.9% sensitivity for identification of facial nerve compression by the anterior inferior cerebellar artery or the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, the first and second most common offending vessels, respectively.8

Neurovascular compression involving the vertebral artery, which accounts for a minority of cases (17%), can be evaluated with 100% sensitivity due to the vessel’s larger caliber.8,9 MRA and computed tomography angiography have demonstrated similar utility in identification of pathologic vessels.10

References

1. Samii M, Günther T, Iaconetta G, et.al. Microvascular decompression to treat hemifacial spasm: Long-term results for a consecutive series of 143 patients. Neurosurgery 2002;50(4):71218; discussion 718-19.

2. Mauriello JA Jr., Leone T, Dhillon S, et al. Treatment choices of 119 patients with hemifacial spasm over 11 years. Clin Neurol Neurosur 1996;98(3):213-16.

3. Zappia JJ, Wiet RJ, Chouhan A, Zhao JC. Pitfalls in the diagnosis of hemifacial spasm. Laryngoscope 1997;107(4):461-5.

4. Lorentz I. Treatment of hemifacial spasm with botulinum toxin. J Clin Neurosci 1995;2(2):132-5.

5. Auger RG, Whisnant JP. Hemifacial spasm in Rochester and Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1960 to 1984. Arch Neurol 1990; 47(11):1233-4.

6. Palacios E, Breaux J, Alvernia JE. Hemifacial spasm. Ear Nose Throat J 2008;87(7):368-70.

7. Wang A, Jankovic J. Hemifacial spasm: Clinical findings and treatment. Muscle Nerve 1998;21(12):1740-7.

8. Nagaseki Y, Omata T, Ueno T, et al. Prediction of vertebral artery compression in patients with hemifacial spasm using oblique sagittal MR imaging. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1998;140(6):565-71.

9. Payner TD, Tew JM Jr. Recurrence of hemifacial spasm after microvascular decompression. Neurosurgery 1996;38(4):686–90; discussion 690-1.

10. El Refaee E, Langner S, Baldauf J, et al. Value of 3-dimensional highresolution magnetic resonance imaging in detecting the offending vessel in hemifacial spasm: Comparison with intraoperative high definition endoscopic visualization. Neurosurgery 2013;73(1):58-67.

56 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal March 2018

ImAgINg CLINIC

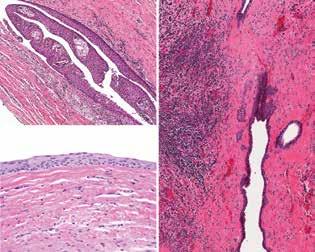

PATHOLOGY CLINIC

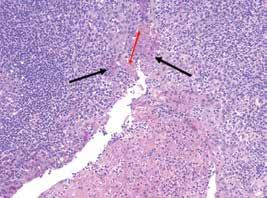

Dentigerous cyst

Lester D.R. Thompson, MD

A dentigerous cyst is a development cyst that surrounds and envelops the crown of an unerupted tooth, attached at the crown-root (cemento-enamel or cervical) junction. Dentigerous cysts account for about 20% of all odontogenic cysts, developing during a peak age of 10 to 30 years, with a male predilection (3:2). The lesion presents in the mandible (3rd molar region) about twice as often as the maxilla (near maxillary canines).

Patients are usually asymptomatic, so these cysts are incidentally discovered during routine dental imaging. However, pain may be experienced with bone expansion or resorption of adjacent teeth. Imaging studies (orthopantomographs) usually show a unilocular radiolucency surrounding the crown of the affected tooth (figure 1), with a well-defined sclerotic border. Cyst enucleation or extraction is generally employed, although marsupialization is sometimes used for larger lesions.

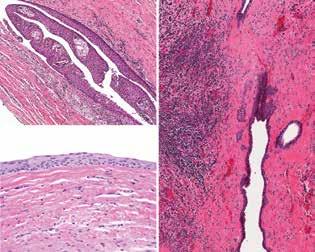

Histologically, there is a difference in findings depending on whether the lesion is inflamed. The noninflamed cyst shows 2 to 3 cell layers of cuboidal to squamoid

cells adjacent to fibrous connective tissue (figure 2), rarely showing ciliated, mucous, or sebaceous cells. The inflamed cyst shows a much thicker, proliferative epithelium, with hyperplastic rete, chronic inflammation (figure 2), and sometimes hyalinized keratin (Rushton bodies). Cholesterol clefts are common.

The differential diagnosis includes a dental follicle, an eruption cyst (a soft-tissue cyst overlying the erupting tooth), a glandular odontogenic cyst, and a unicystic ameloblastoma, while an odontogenic keratocyst may also be considered.

Suggested reading

Johnson NR, Gannon OM, Savage NW, Batstone MD. Frequency of odontogenic cysts and tumors: A systematic review. J Investig Clin Dent 2014;5(1):9-14.

Lin HP, Wang YP, Chen HM, et al. A clinicopathological study of 338 dentigerous cysts. J Oral Pathol Med 2013;42(6):462-7.

From the Department of Pathology, Southern California Permanente Medical Group, Woodland Hills Medical Center, Woodland Hills, Calif.

Volume 97, Number 3 www.entjournal.com 57

Figure 1. A unilocular radiolucency around tooth #32 (arrow) shows a crown-root junction of the cyst in this orthopantomograph.

Figure 2. Left: A few layers of epithelium are noted, lacking a palisading of the nuclei and showing an abrupt junction with the surrounding fibrous tissue. Right: Inflammation is noted in the adjacent stroma, with several projections of the epithelium into the stroma.

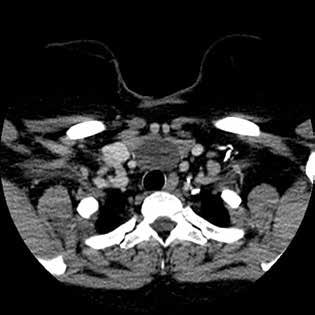

THYROID AND PARATHYROID CLINIC

A midline mediastinal parathyroid cyst

Guy

A 49-year-old woman presented with progressive dysphagia of several months’ duration accompanied by a pressure sensation at the lower anterior base of her neck. Her medical history was significant for type II diabetes, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, obesity, anxiety, and depression. Lab values were unremarkable. Physical examination revealed no neck mass. The remainder of her head and neck examination was within normal limits. On ultrasound, a cystic lesion measuring 4.0 × 2.7 × 3.6 cm was seen, abutting and immediately caudal to the thyroid isthmus. There were no pathologic findings within the thyroid gland and no neck lymphadenopathy.

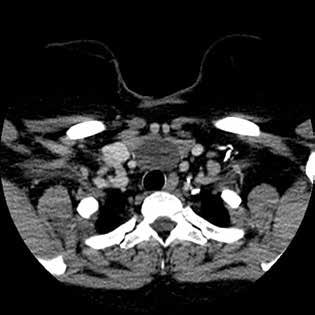

Computed tomography (CT) of the neck with intravenous contrast revealed a cystic mass of similar dimensions adhering to the anterior tracheal surface

and occupying the space between the thyroid isthmus and the aortic arch. Because of mass effect, there was splaying of the inferior poles of the thyroid lobes and the left and right innominate veins (figure 1).

The cytologic findings of an ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy were of rare macrophages, inflammatory cells, and proteinaceous debris, consistent with cystic contents; there was no evidence of malignant cells.

The patient underwent exploration of the lower neck and upper anterior mediastinum by a cervical approach. A cystic lesion at the superior anterior mediastinum was identified. It was meticulously dissected and entirely removed. Histopathology revealed a unilocular cystic cavity containing parathyroid cells in rare residual groups on an otherwise flat lining and in focal nests

58 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal March 2018

From the Department of Surgery, Division of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (Dr. Slonimsky, Dr. Baker, and Dr. Goldenberg) and the Department of Pathology (Dr. Crist), The Pennsylvania State University, College of Medicine, Hershey.

Slonimsky, MD; Aaron Baker, MD; Henry Crist, MD; David Goldenberg, MD

A B

Figure 1. A: Axial CT with contrast of the neck and chest demonstrates a homogeneous cystic lesion overlying the inferior border of the thyroid gland, anterior border of the trachea, and the great mediastinal vessels. B: Coronal CT of the cyst demonstrates its cervical and mediastinal components with splaying of the innominate veins.

within its fibrous wall, indicative of a parathyroid cyst (figure 2).

Parathyroid cysts are rare lesions of the neck and mediastinum with a peak incidence in the fourth and fifth decades of life.1-3 These cysts are generally divided into nonfunctional or functional, based on their hormonal activity, and can rarely lead to hypercalcemic crisis. 3-5 There are several theories for the pathogenesis of these cysts, including remnants of branchial clefts, retention cysts, coalescence of numerous minute cystic lesions, or degeneration of an adenoma.3

The clinical presentation is varied and ranges from an incidental finding on imaging or physical examination in the asymptomatic patient to a neck mass with compressive symptoms, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, and sometimes hyperparathyroidism.2-4,6 The mainstay of diagnosis includes neck ultrasonography, CT, or magnetic resonance imaging, with nonspecific findings of a benign-appearing homogeneous cystic lesion.7 Detection of parathyroid hormone in fine-needle aspiration can facilitate the diagnosis, as parathyroid cysts can be easily misdiagnosed as thyroid cysts or other cystic lesions of the neck.8 Histopathology will reveal a smooth cystic lesion lined with cuboidal epithelium and nests of parathyroid cells within its wall.9

Nonfunctioning asymptomatic cysts can be observed with routine follow-up. Symptomatic nonfunctioning cysts can be treated with fluid aspiration2 or sclerotherapy in recurrent cases with the risk of fibrosis.10,11 Although needle aspiration may lead to definitive resolution in some cases,12 surgical resection is warranted in many cases as a diagnostic procedure, for the treatment of hyperparathyroidism (in cases of functional cysts), and because of the rare possibility of

parathyroid carcinoma presenting as a cystic neck or mediastinal mass.13,14

The location and size of the parathyroid cyst will dictate the appropriate surgical approach. The cervical approach will enable the resection of lesions in the neck and upper mediastinum, whereas large mediastinal lesions and lower or posterior mediastinal lesions will require thoracotomy, median sternotomy, or thoracoscopy.15

References

1. Cappelli C, Rotondi M, Pirola I, et al. Prevalence of parathyroid cysts by neck ultrasound scan in unselected patients. J Endocrinol Invest 2009;32(4):357–9.

2. Ippolito G, Palazzo FF, Sebag F, et al. A single-institution 25-year review of true parathyroid cysts. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2006; 391(1):13–18.

3. Shields TW, Immerman SC. Mediastinal parathyroid cysts revisited. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;67(2):581–90.

4. Suzuki K, Sakuta A, Aoki C, Aso Y. Hyperparathyroidism caused by a functional parathyroid cyst. BMJ Case Rep 2013 June 21;2013. pii: bcr2012008290

5. Khan A, Khan Y, Raza S, et al. Functional parathyroid cyst: A rare cause of malignant hypercalcemia with primary hyperparathyroidism—a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Med 2012;2012:851941.

6. Jarnagin WR, Clark OH. Mediastinal parathyroid cyst causing persistent hyperparathyroidism: Case report and review of the literature. Surgery 1998;123(6):709–11.

7. Kato H, Kanematsu M, Kiryu T, et al. Nonfunctional mediastinal parathyroid cyst: Imaging findings in two cases. Clin Imaging 2008;32(4):310–13.

8. Ujiki MB, Nayar R, Sturgeon C, Angelos P. Parathyroid cyst: Often mistaken for a thyroid cyst. World J Surg 2007;31(1):60–4.

9. Fortson JK, Patel VG, Henderson VJ. Parathyroid cysts: A case report and review of the literature. Laryngoscope 2001;111(10): 1726–8.

10. Kaplanoglu V, Kaplanoglu H, Ciliz DS, Duran S. A rare cystic lesion of the neck: Parathyroid cyst. BMJ Case Rep 2013 Oct 11;2013. pii: bcr2013200813

11. Kim JH. Ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy for benign non-thyroid cystic mass in the neck. Ultrasonography 2014;33(2):83–90.

12. Prinz RA, Peters JR, Kane JM, Wood J. Needle aspiration of nonfunctioning parathyroid cysts. Am Surg 1990;56(7):420–22.

13. Vazquez FJ, Aparicio LS, Gallo CG, Diehl M. Parathyroid carcinoma presenting as a giant mediastinal retrotracheal functioning cyst. Singapore Med J 2007;48(11):e304-7.

14. Pirundini P, Zarif A, Wihbey JG. A rare manifestation of parathyroid carcinoma presenting as a cystic neck mass. Conn Med 1998;62(4):195–7.

15. Dell’Amore A, Asadi N, Bartalena T, et al. Thoracoscopic resection of a giant mediastinal parathyroid cyst. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;62(7):444–50.

60 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal March 2018 ThyROId ANd PARAThyROId CLINIC

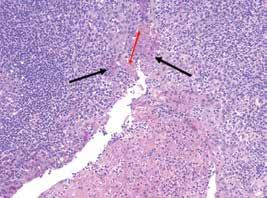

Figure 2. Nests of parathyroid cells are seen within the wall of the cyst with residual foci lining the cyst wall (arrow) (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×100).

SPECIAL TOPICS CLINIC

Complete resolution of guttate psoriasis after tonsillectomy

Psoriasis is a chronic, inflammatory, immunemediated disease that affects 3.2% of adults in the United States.1 Streptococcal infections have been associated with several systemic disease processes including glomerulonephritis and rheumatic heart disease. A well-established link between psoriasis and streptococcal infection also has been reported in the literature.1,2 Specifically, this association appears to be with both guttate and plaque psoriasis.

Although the exact etiology is unclear, it is believed that a streptococcal trigger residing in the palatine tonsils might activate T cells in the skin through molecular mimicry.1 HLA-Cw*0602 homozygosity has been linked to streptococcal-associated psoriasis.3 Several studies have reported improvement or complete resolution of psoriasis after tonsillectomy.1,2,4-8

A 26-year-old man presented to our office with a history of recurrent streptococcal tonsillitis. One episode of tonsillitis was treated with oral levofloxacin by his primary care physician. However, because the patient

developed joint pain after several days of treatment, it was discontinued.

Two weeks later, the patient began to develop a rash over his hands (figure 1), trunk, back, and extremities. The patient was evaluated by a dermatologist and was subsequently diagnosed with guttate psoriasis. It was further described as a salmon-pink, teardrop-shaped papular rash with a fine scale. This rash was treated with topical steroids.

Several months later the rash resolved, but it returned with another episode of tonsillitis. Given the recurrent episodes of tonsillitis, the patient underwent tonsillectomy 2 months later. After surgery, the rash completely resolved (figure 2). On his back, some hypopigmented lesions from scarring remained, but these are expected to improve over time. The patient currently does not require treatment for psoriasis; his rash has not returned to date.

Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of tonsillectomy for the treatment of streptococcal-associated

62 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal March 2018

From the Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine (Dr. Cohn and Dr. Pfeiffer); and the Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Jefferson Health–Methodist Hospital (Dr. Vernose), Philadelphia.

Jason E. Cohn, DO; Michael Pfeiffer, DO; Gerard Vernose, MD

Figure 1. Photo shows the guttate psoriasis on the patient’s hands before tonsillectomy.

Figure 2. This photo shows the patient’s hands 2 months after tonsillectomy. The psoriasis has resolved completely.

psoriasis. One meta-analysis revealed that 290 of 410 (70.7%) patients with psoriasis who underwent tonsillectomy experienced improvement of their psoriasis.1 The authors concluded that evidence is insufficient to support tonsillectomy in most patients with psoriasis. However, a tonsillectomy might be beneficial when psoriasis exacerbations are closely associated with recurrent tonsillitis.1

A randomized, controlled trial demonstrated that patients with plaque psoriasis undergoing tonsillectomy had significantly improved health-related quality of life and psoriasis-related stress.5 A Cochrane database protocol states that adult tonsillectomy for psoriasis is beneficial, but the evidence for this is not robust.6

It has been shown, especially with guttate psoriasis, that tonsillectomy has a potential benefit in psoriasis disease burden.1,5,7,8 Our patient demonstrated complete recovery after tonsillectomy. The decision to perform a tonsillectomy in this case was appropriate because the patient’s psoriasis flares corresponded with episodes of tonsillitis. It is important to highlight this case because it involved an adult, although tonsillitis-associated guttate psoriasis is typically reported in the pediatric population.4,7,8 Additionally, we demonstrated a significant improvement in this disease process with photographic evidence. Future prospective studies looking at the efficacy of tonsillectomy on psoriasis are encouraged.

References

1. Rachakonda TD, Dillon JS, Florek AG, Armstrong AW. Effect of tonsillectomy on psoriasis: A systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;72(2):261-75.

2. Sigurdardottir SL, Thorleifsdottir RH, Valdimarsson H, Johnston A. The role of the palatine tonsils in the pathogenesis and treatment of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2013;168(2):237-42.

3. Thorleifsdottir RH, Sigurdardottir SL, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. HLA-Cw6 homozygosity in plaque psoriasis is associated with streptococcal throat infections and pronounced improvement after tonsillectomy: A prospective case series. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016;75(5):889-96.

4. Saita B, Ishii Y, Ogata K, et al. Two sisters with guttate psoriasis responsive to tonsillectomy: Case reports with HLA studies. J Dermatol 1979;6(3):185-9.

5. Thorleifsdottir RH, Sigurdardottir SL, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and clinical response in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis treated with tonsillectomy: A randomized controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol 2017;97(3): 340-5.

6. Owen CM, Chalmers RJ, O’Sullivan T, Griffiths CE. Antistreptococcal interventions for guttate and chronic plaque psoriasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000(2):CD001976.

7. Hone SW, Donnelly MJ, Powell F, Blayney AW. Clearance of recalcitrant psoriasis after tonsillectomy. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 1996;21(6):546-7.

8. McMillin BD, Maddern BR, Graham WR. A role for tonsillectomy in the treatment of psoriasis? Ear Nose Throat J 1999;78(3):155-8.

Volume 97, Number 3 www.entjournal.com 63 SPECIAL TOPICS CLINIC

Post-turbinectomy nasal packing with Merocel versus glove finger

Merocel: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial

Rani Abu Eta, MD; Ephraim Eviatar, MD; Jacob Pitaro, MD; Haim Gavriel, MD

Abstract

Nasal packs are widely used after septoplasty and turbinectomy. We conducted a prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial including 100 patients who underwent septoplasty with/or without turbinectomy randomized into two groups. In the first group (the Merocel group), a standard tampon was inserted at the end of surgery. In the second group (the glove finger group), the tampon was first placed inside a glove finger. The main outcomes measured were pain and bleeding during the postoperative period and during tampon removal. Consumption of pain killers and tranexamic acid were also recorded. The mean visual analog scale score 12 hours after surgery and during tampon removal in the Merocel group were 6.78 and 8.92, respectively, compared to 4.06 and 5.27, respectively, in the glove finger group (p < 0.001). A statistically significant difference in the bleeding rate and tranexamic acid consumption during tampon removal in favor of the Merocel group was shown (p < 0.001). The use of Merocel in a glove finger is significantly less painful, although a higher chance of bleeding is reported. The influence of the surgeon’s experience in using this technique needs further investigation.

Introduction

Septoplasty and reduction of the inferior turbinates are the most commonly used surgical interventions to enhance nasal airways compromised secondary to nasal septal deviations and turbinate hypertrophy.

From the Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Assaf Harofeh Medical Center, Zerifin, Israel, affiliated to the Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, Israel.

Corresponding author: Dr. Haim Gavriel, Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Assaf Harofeh Medical Center, Zerifin 70300, Israel. Email: haim.ga@012.net.il

Nasal packs are widely used after these operations to prevent nasal bleeding, to support the mucoperichondrial flaps, and to minimize the risk of forming septal hematomas and prevent adhesions.1

Since Hippocrates first defined nasal tampon packing in the fifth century BC, 2 various materials have been proposed for nasal packing, such as gauzes with or without medication (e.g., paraffin), Telfa cellulose and foam, Merocel (a polyvinyl acetate sponge; Medtronic Xomed; Jacksonville, Fla.), expanding sponges, ready-made or inflatable tampons, and Foley catheters. Ideally, nasal packs should be easy to insert and remove with minimal discomfort, and they should also effectively prevent postoperative bleeding. 3,4

The use of nasal packing may result in several side effects that include pain, dysphagia, eustachian tube blockage, sinusitis, synechia and toxic shock syndrome.5-7 Aspiration of nasal packing and airway obstruction have also been reported.8 However, the most frequent patient complaints appear to be pain and bleeding during removal of nasal tampons.

Merocel dressings are widely used after endonasal surgery.9,10 To reduce pain during their removal, several studies have proposed using Merocel within a glove finger after septoplasty and endoscopic sinus surgery.7,11 However, a higher risk of bleeding post-turbinectomy is expected and, to the best of our knowledge, no study on the use of Merocel in a glove finger has been reported in the English literature.

In this study, we prospectively compared the effects of two different types of nasal packs on pain and bleeding after turbinectomy with or without septoplasty: Merocel standard 8-cm nasal dressing and Merocel in a glove finger.

64 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal March 2018 ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Patients and methods

A prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial comparing Merocel nasal pack and Merocel within a glove finger regarding pain and bleeding before and during tampon removal was conducted. The study was approved by the Institute Ethical Committee.

The study group included 100 consecutive patients with an indication for septoplasty with turbinectomy or turbinectomy alone. Twelve operations were performed under general anesthesia and 88 under local anesthesia. Local homeostasis was achieved with lidocaine HCl 1% and epinephrine 1:100,000.

Excluded were patients younger than 18 years, patients with a history of previous endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) or underlying immunologic diseases, patients with Samter’s triad, those allergic to latex, and those who reported using anticoagulants or antiaggregants.

Surgical technique. Surgery was carried out under general or local anesthesia. After proper premedication, the nasal cavities were packed with 2% lidocaine with epinephrine (1: 100,000) and then removed after several minutes. Angled turbinate scissors were used for this procedure. One blade was inserted beneath the inferior turbinate and the other on top of it after the turbinate was fractured medially. Resection included the turbinate mucosa and, partially, the bone. The extent of the resection depended on the degree of turbinate hypertrophy.

The patients were randomized into two groups according to the last digit of their identity number. Patients in the first group were packed at the end of surgery with a standard 8-cm Merocel tampon (Merocel group). Patients in the second group were packed with a Merocel tampon of the same size that was placed in a glove finger of a regular sterile glove (glove finger group).

All tampons in both groups were secured to the nose with tape and a 2-0 silk stich—through the anterior edge of the tampon in the Merocel group and through the anterior edge of the glove finger in the glove finger group. The same nasal packing materials were used for both sides of the nose for each patient. The nasal tampons were removed 48 hours postoperatively.

Surgical outcomes. The main outcomes measured were pain and bleeding during the postoperative period. Pain was evaluated by a nurse using a visual analog scale (VAS) numbered from 0 to 10 (0 representing the least pain and 10 the maximum pain) at two times: 12 hours after surgery and during the removal of the tampons. Patient painkiller intake was divided into three categories: category A, per os: dipyrone 1 g

(metamizole in the United States), acetaminophen 1 g, or oxycodone 5 mg and naloxone 2.5mg); category B, per os: oxycodone 5mg and acetaminophen 325 mg or tramadol 50 mg; and category C, intravenous: tramadol 100 mg.

Bleeding after the removal of the nasal tampon was evaluated according to the following scale created by the authors of this study: 0 = no bleeding; 1 = blood seeping from the nose; 2 = continuous bleeding from the nose; 3 = bleeding stopped in the operating room.

The need for intravenous tranexamic acid was recorded in both groups.

Statistical analyses. Categorical variables were reported as numbers (percentages), and continuous variables as means (standard deviations [SD]) or medians (interquartile ranges [IQR]). Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test and quantile-quantile (q-q) plots. The chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables; continuous variables were compared by the independent-samples t test or the Mann-Whitney U test. A two-tailed p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed with R (R Project for Statistical Computing) version 3.1.2.

Results

A total of 100 patients (87 men and 13 women; mean age: 22 years, range 18 to 69 years) were enrolled prospectively during the study period. The Merocel group consisted of 41 patients with a median age of 29 years, and the glove finger group consisted of 59 patients with a median age of 22 years (p = 0.012) (table 1).

Comorbidities were identified in 5 (5%) patients: 3 patients had hypertension, 1 patient had ischemic heart disease, and 1 patient had hypercholesterolemia.

The median VAS scores 12 hours after surgery and during tampon removal in the Merocel group were 7 and 9, respectively, compared to VAS scores of 4 and 5, respectively, in the glove finger group (p < 0.001) (table 1).

All patients in the Merocel group consumed an analgesic; 11 (18.6%) patients in the glove finger group did not (p = 0.002). Six (14.6%) patients in the Merocel group needed category A painkillers, 25 (61.0%) needed category B painkillers, and 10 (24.4%) needed category C painkillers. In the glove finger group, 11 (18.6%) patients needed no painkillers at all, 40 (67.8%) patients were treated with category A painkillers, and 8 (13.6%) with category B painkillers.

Thirty-five patients (85.4%) in the Merocel group showed no signs of bleeding during tampon removal

Volume 97, Number 3 www.entjournal.com 65

POST-TURbINECTOmy NASAL PACkINg wITh mEROCEL vERSUS gLOvE fINgER mEROCEL: A PROSPECTIvE, RANdOmIzEd, CONTROLLEd TRIAL

Key: IQR = interquartile range; SMR = submucous resection;VAS = visual analog scale.

compared to only 2 (3.4%) patients in the glove finger group ( p < 0.001). Mild bleeding was observed in the other 6 (14.6%) patients in the Merocel group. However, in the glove finger group, mild bleeding was detected in 27 (45.8%) patients, continuous bleeding in another 27 (45.8%) patients, and in 3 (5.1%) patients the bleeding was stopped only in the operating room ( p < 0.001) (table 2).

In the Merocel group, 2 (4.9%) patients needed intravenous administration of tranexamic acid (1 g) after tampon removal due to continuous bleeding compared to 19 (32.2%) patients in the glove finger group (p = 0.001) (table 2).

Discussion

Septoplasty and reduction of the inferior turbinates are among the most common surgical interventions in otorhinolaryngology. Since these operations may lead to significant bleeding postoperatively, nasal packing is widely used to reduce bleeding. The use of nasal packing may, by itself, lead to severe complications. One of the most significant concerns of patients is pain during removal of the tampon while that of the surgeon is postoperative bleeding.12

Merocel packing is the most commonly used material after nasal surgery, with well-known advantages and reported complications and disadvantages such as pain and bleeding. Endeavors to alleviate the disadvantages of Merocel tampons by using glove fingers during ESS and post-septoplasty have been previously reported.1,3-5 In these studies, the major benefit of using a Merocel tampon in a glove finger was the reduced pain reported by the patients during tampon removal. No significant difference was observed in these studies regarding bleeding after the removal of the tampons. However, none of these studies investigated the outcomes after inferior turbinectomy.

Major bleeding during or after septoplasty is seldom observed due to the good visualization of the surgical field during the operation.7 In cases of significant

66 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal March 2018 AbU ETA, EvIATAR, PITARO,

gAvRIEL

Merocel group (n = 41) Glove finger group (n = 59) p Value Sex, n (%) male 35 (85.4) 52 (88.1) 0.685 female 6 (14.6) 7 (11.9) median age, yr (IQR) 29 (21-41.5) 22 (20-25) 0.012 Surgery, n (%) SmR conchotomy 37 (90.2) 54 (91.5) >0.999 Conchotomy 4 (9.8) 5 (8.5) Anesthesia, n (%) Local 33 (80.5) 55 (93.2) 0.066 general 8 (19.5) 4 (6.8) Analgesics, n (%) 41 (100) 48 (81.4) 0.002 Pain killers, n (%) None 0 (0) 11 (18.6) <0.001 Category A 6 (14.6) 40 (67.8) Category b 25 (61.0) 8 (13.6) Category C 10 (24.4) 0 (0) vAS during hospitalization, median (IQR) 7 (6-7) 4 (3-5) <0.001 vAS during removal, median (IQR) 9 (9-9.5) 5 (4-6) <0.001

Table 1. Differences in pain and pain control in the Merocel group vs. the glove finger group

Merocel group (n = 41) Glove finger group (n = 59) p Value Tranexamic acid, n (%) 2 (4.9) 19 (32.2) 0.001 bleeding, n (%) 6 (14.6) 57 (96.6) <0.001 bleeding grade, n (%) No bleeding 35 (85.4) 2 (3.4) <0.001 blood seeping from nose 6 (14.6) 27 (45.8) Continuous bleeding from nose 0 (0) 27 (45.8) bleeding stopped in OR 0 (0) 3 (5.1)

Table 2. Differences in bleeding between the Merocel and glove finger groups

bleeding, cauterization is feasible and successful in most cases. ESS harbors great risk to major vessels with possible significant bleeding. However, the magnified surgical field and the ability of the surgeon to work with two hands enables better bleeding control. ESS should be finalized with no significant bleeding and, therefore, the use of a tampon in a glove finger is mostly effective.

Inferior turbinectomy poses a unique challenge regarding nasal packing. In many cases, it will not be performed with endoscopic surgery, and the surgeon relies on his or her ability to view the turbinates throughout their entire length. Moreover, major bleeding from major branches of the sphenopalatine artery is usually encountered from the posterior half of the injured turbinate. Therefore, optimal packing should be used post-turbinectomy, especially when it is performed by a lesser-trained surgeon.

The results of the current study indicate that nasal packing with Merocel carries significantly higher pain scores when compared to the use of Merocel in a glove finger, either after septoplasty with inferior turbinectomy or turbinectomy alone. We attributed the lower degree of pain reported in patients in the glove finger group to less adherence of the Merocel glove finger to the structures inside the nose, thereby lowering the amount of superficial tissue injured by the exiting tampon and resulting in significantly less consumption of painkillers.13,14

Our study also demonstrates statistically significant greater postoperative bleeding when using a Merocel tampon in a glove finger, with a significantly greater need for intravenous tranexamic acid. Unfortunately, the advantage of less pain due to less adherence of the packing to the tissue and a smaller amount of tissue trauma during the pack removal brings with it the disadvantage of bleeding. As the amount of tissue in close contact with a Merocel tampon in a glove finger is reduced compared to Merocel, a higher chance of blood vessels not directly affected by the influence of the tampon is anticipated, leading to a higher chance of postoperative bleeding.

It is important to mention that all patients reported in this series were operated on by our skilled residents, experienced with these types of surgeries. However, we believe that an experienced consultant surgeon would have targeted the placement of the Merocel tampon in a glove finger to the higher bleeding risk areas of the nose, thereby possibly lowering the chances of postoperative bleeding.

Conclusion

The use of Merocel in a glove finger is significantly less painful for the patient than Merocel directly inserted into the nostril, although a higher risk of bleeding is demonstrated. We are preparing for a comparative study to investigate the effect of the surgeon’s experience on the bleeding rate post-turbinectomy when using Merocel in a glove finger.

References

1. Acio lu E, Edizer DT, Yi it Ö, Alkan Z. Nasal septal packing: Which one? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2012;269(7):1777–81.

2. Singer AJ, Blanda M, Cronin K, et al. Comparison of nasal tampons for the treatment of epistaxis in the emergency department: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med 2005; 45(2):134–9.

3. Ozcan C, Vayisoglu Y, Kiliç S, Görür K. Comparison of rapid rhino and merocel nasal packs in endonasal septal surgery. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008;37(6):826–31.

4. Bresnihan M, Mehigan B, Curran A. An evaluation of Merocel and Series 5000 nasal packs in patients following nasal surgery: A prospective randomised trial. Clin Otolaryngol 2007;32(5):352–5.

5. Ardehali MM, Bastaninejad S. Use of nasal packs and intranasal septal splints following septoplasty. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009;38(10):1022-4.

6. Taasan V, Wynne JW, Cassisi N, Block AJ. The effect of nasal packing on sleep-disordered breathing and nocturnal oxygen desaturation. Laryngoscope 1981;91(7):1163-72.

7. Celebi S, Caglar E, Develioglu ON, et al. The effect of the duration of merocel in a glove finger on postoperative morbidity. J Craniofac Surg 2013;24(4):1232-4.

8. Koudounarakis E, Chatzakis N, Papadakis I, et al. Nasal packing aspiration in a patient with Alzheimer’s disease: A rare complication. Int J Gen Med 2012;5:643-5.

9. Badran K, Malik TH, Belloso A, Timms MS. Randomized controlled trial comparing Merocel and RapidRhino packing in the management of anterior epistaxis. Clin Otolaryngol 2005;30(4):333–7.

10. Corbridge RJ, Djazaeri B, Hellier WP, Hadley J. A prospective randomized controlled trial comparing the use of merocel nasal tampons and BIPP in the control of acute epistaxis. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 1995;20(4):305–7.

11. Garth RJ, Brightwell AP. A comparison of packing materials used in nasal surgery. J Laryngol Otol 1994;108(7):564–6.

12. Eliashar R, Gross M, Wohlgelernter J, Sichel JY. Packing in endoscopic sinus surgery: Is it really required? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2006;134(2):276-9.

13. Lemmens W, Lemkens P. Septal suturing following nasal septoplasty, a valid alternative for nasal packing? Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg 2001;55(3):215-21.

14. Weber R, Keerl R, Hochapfel F, et al. Packing in endonasal surgery. Am J Otolaryngol 2001;22(5):306–20.

68 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal March 2018

AbU ETA, EvIATAR, PITARO, gAvRIEL

Comparison of anterior palatoplasty and uvulopalatal flap placement for treating mild and moderate obstructive sleep apnea

Süheyl Haytoğlu, MD; Osman Kürşat Arikan, MD; Nuray Bayar Muluk, MD; Birgül Tuhanioğlu, MD; Mustafa Çörtük, MD

Abstract

We prospectively compared the efficacy of anterior palatoplasty and the uvulopalatal flap procedure for the treatment of patients with mild and moderate obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS). Our study group was made up of 45 patients who had been randomly assigned to undergo one of the two procedures. Palatoplasty was performed on 22 patients—12 men and 10 women, aged 28 to 49 years (mean: 39.2)—and the flap procedure was performed on 23 patients—14 men and 9 women, aged 28 to 56 years (mean: 41.3). Our primary outcomes measure was the difference in pre- and postoperative apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) as determined by polysomnography at 6 months after surgery. Surgical success was observed in 18 of the 22 palatoplasty patients (81.8%) and in 19 of the 23 flap patients (82.6%). Compared with the preoperative values, mean AHIs declined from 17.5 to 8.1 in the former group and from 18.5 to 8.6 in the latter; the improvement in both groups was statistically significant (p < 0.001). In addition, significant postoperative improvements in both groups were seen in mean visual analog scale (VAS) scores for snoring, in Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index values, and in Epworth Sleepiness Scale scores (p < 0.001 for all). VAS scores for pain at rest were significantly lower in the palatoplasty group than in the flap group at 2, 4, and 8 hours postoperatively and on postoperative days 4 through 7 (p <

From the ENT Clinic, Adana Numune Training and Research Hospital, Adana, Turkey (Dr. Haytoğlu, Prof. Arikan, and Dr. Tuhanioğlu); the ENT Department, Kırıkkale University Faculty of Medicine, Kırıkkale, Turkey (Prof. Muluk); and the Pulmonary Diseases Department, Karabük University Faculty of Medicine, Karabük, Turkey (Dr. Çörtük). The study described in this article was conducted at Adana Numune Training and Research Hospital. Corresponding author: Prof. Nuray Bayar Muluk, ENT Department, Kırıkkale University Faculty of Medicine, Birlik Mahallesi, Zirvekent 2. Etap Sitesi, C-3 blok, No: 62/43 06610 Çankaya, Kırıkkale, Turkey. Email: nurayb@hotmail.com

0.002). Likewise, VAS scores for pain during swallowing were significantly lower in the palatoplasty group at 2, 4, 8, and 16 hours and on days 4 through 7 (p < 0.009). We conclude that both anterior palatoplasty and uvulopalatal flap procedures are effective for the treatment of mild and moderate OSAS in patients with retropalatal obstruction. However, our comparison of postoperative pain scores revealed that anterior palatoplasty was associated with significantly less morbidity.

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is characterized by episodes of partial or complete obstruction of the upper airway during sleep, which results in interruptions (apnea) or reductions (hypopnea) of the flow of air; the transient awakening that follows leads to the restoration of upper airway permeability.1 In the upper airway, the retropalatal area is the most common site of the obstructive process.2,3

Since Fujita et al first described uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) in 1981,4 many studies have been published about its efficacy and complication rates. Studies have shown that while short-term success rates ranged from 76 to 95%, rates after 1 year fell to only 46 to 50%.5-9

Since UPPP has been associated with high recurrence and complication rates and patient discomfort, other procedures have been introduced to restore the space at the retropalatal area.9,10 One of them is the uvulopalatal flap procedure, which was first described by Powell et al in 1996.11 Studies showed that flap placement yielded success rates similar to those of UPPP but with less postoperative pain.11-13 Nevertheless, postoperative pain is still a common complication of the uvulopalatal flap procedure, as is temporary velopharyngeal insufficiency and a permanent foreign-body sensation in the pharynx.12,13

Volume 97, Number 3 www.entjournal.com 69 ORIGINAL ARTICLE

A modified cautery-assisted palatal stiffening procedure was introduced by Pang and Terris in 2007 as an alternative to the flap procedure.14 They subsequently called this procedure anterior palatoplasty.15 In their first study, which looked at a small series of patients with mild OSAS, they observed surgical success in 6 of 8 patients (75.0%) as determined by polysomnography, as well as a reduction in daytime sleepiness scores in 11 of 13 patients (84.6%).14 In a subsequent study of 77 patients published in 2009, Pang et al found a success rate of 71.8% for anterior palatoplasty with or without tonsillectomy at a mean of 33.5 months of follow-up.15 With anterior palatoplasty, temporary velopharyngeal insufficiency and postoperative pain are also common, but a foreign-body sensation is not.

In a 2013 study by Marzetti et al, success rates for anterior palatoplasty and the uvulopalatal flap procedure were 86 and 84%, respectively.16 The authors reported lower pain scores in the palatoplasty group. In both groups, they performed a tonsillectomy first if the tonsil size was greater than grade 2. Previous studies of palatal surgeries in OSAS patients had not considered the possible effects of tonsillectomy on success rates and postoperative discomfort, especially pain.

In this article, we describe our comparison of the efficacy of anterior palatoplasty and the uvulopalatal flap procedure for the treatment of mild and moderate OSAS in patients with retropalatal obstruction who did not require a tonsillectomy.

Patients and methods

For this prospective study, we recruited 50 patients who had been diagnosed with mild or moderate OSAS in the ENT Clinic at Adana Numune Training and Research Hospital from June 2012 through January 2014. All diagnoses had been based on the results of polysomnography. All patients had undergone a complete head and neck examination, including flexible fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy to evaluate the posterior airway space. All were found to have retropalatal collapse, based on the Müller maneuver.

Our inclusion criteria were an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of greater than 5 and less than 30, a body mass index (BMI) of less than 30 kg/m 2 , a tonsillar hypertrophy grade of 0 or 1,17 and the presence of retropalatal obstruction. Exclusion criteria included previous palatal surgery, the presence of a retrolingual obstruction, and the presence of a chronic disease that prevented surgery.

Of the 50 patients, 25 were randomly assigned to undergo anterior palatoplasty and 25 were randomized to uvulopalatal flap surgery. Tonsillectomy was not performed in either group. During surgery, sutures became unraveled in 3 palatoplasty patients and 2 flap

patients, and thus these cases were not included in our final analysis. As a result, our final study population was made up of 45 patients. The palatoplasty group included 22 patients—12 men and 10 women, aged 28 to 49 years (mean: 39.2)—and the flap group included 23 patients—14 men and 9 women, aged 28 to 56 years (mean: 41.3).

Surgical procedures. Anterior palatoplasty. All palatoplasties were performed with general anesthesia. First, the mucosa and submucosal tissue (including fat) were removed as a horizontal rectangular strip (70 to 100 mm long and 40 to 50 mm wide) from the lingual surface of the soft palate down to the muscle layer. Bipolar cautery was used for hemostasis. The remaining tissue was sutured with 4-0 Vicryl and a round-body curved needle.

Uvulopalatal flap procedure. All flap procedures were likewise performed with general anesthesia. After insertion of a Dingman mouth gag, the projection formed by folding the uvula toward the soft palate was determined and the mucosa, submucosa with glands, and the fat on the lingual surface of the uvula and soft palate according to the determined area were removed with a scalpel. Then the uvular tip was amputated. Once bleeding was controlled, horizontal incisions were made to the upper part of the posterior plicas of the tonsils. The uvula was folded into its new position and was fixed with 3-0 Vicryl sutures.

During the postoperative period, patients were administered analgesia in the form of acetaminophen at 250 mg/5 ml in doses of 10 to 15 mg/kg per dose 4 times a day.18 Patients were permitted to take additional acetaminophen as long as the total daily dose did not exceed 4 g. All acetaminophen intake was recorded.

Data collection. In addition to demographic information, we compiled pre- and postoperative data on patients’ AHI, snoring, sleep quality, daytime sleepiness, and postoperative pain. We also recorded the duration of surgery and the amount of intraoperative blood loss.

AHI. The primary outcomes measure was the difference between pre- and postoperative AHI at 6 months after surgery as determined by polysomnography. The other findings were secondary outcomes.

Snoring. Snoring was assessed by bed partners preoperatively and 6 months postoperatively with the use of a visual analog scale (VAS) of 0 (none) to 10 (extremely loud).

Quality of sleep. We assessed the quality of sleep with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), which is one of the most commonly used scales in sleep research.19 It was originally designed for use in clinical populations as a simple and valid assessment of both sleep quality and sleep disturbance that might affect sleep quality.

70 www.entjournal.com ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal March 2018

hAyTO LU, ARIkAN, mULUk, TUhANIO LU, ÇÖRTÜk