Pass The Wine Gas The Science Of Wine-Food Pairings Sweet Rewards: Malvasia Bianca TECHNIQUES & TIPS TO KEEP YOU IN THE PINK WINEMAKERMAG.COM STOP & SMELL THE APRIL - MAY 2022 VOL.25, NO.2 ALTERNATIVE YEAST STRAINS FROZEN MUST WINEMAKING

Perfectly

© 2022 RJS Craft Winemaking

more at rjscraftwinemaking.com or bsghandcraft.com

LIMITEDTIMEONLY

Learn

timed for spring’s awakening, and ready to drink in just 4 weeks!

WINEMAKERMAG.COM APRIL - MAY 2022 1 Looking for Bottles, Caps and Closures? 888-539-3922 • waterloocontainer.com Like us on Facebook! • Extensive inventory of ready-to-ship bottles, caps and closures • No MOQ on most items – we serve all sizes of customers • Industry expertise to guide you through the packaging process • Quality products and customization to create or enhance your brand You Can Rely on Us

24 INERT GASES FOR WINEMAKING

There are four gases often used in winemaking, each with its own unique advantages. Learn more about what sets carbon dioxide, argon, nitrogen, and beer gas apart, and which is best for each chore where gas can be of assistance in the home winery.

by Bob Peak

by Bob Peak

30 LA VIE EN DRY ROSÉ

Pink wines may have gotten a bad rap due to sweet versions that dominated in the 80s and 90s, however, dry rosé is becoming more and more popular among winemakers and consumers alike. Whether a dry rosé was always the goal or you have grapes that better suit pink than red wine — we’ll supply the advice to craft an excellent summer sipper.

by Phil Plummer

by Phil Plummer

36 KIMCHI

Among the few bright spots caused by the worldwide pandemic is that many people stuck at home got into home fermentations — and those aren’t limited to beverages. Kimchi is a Korean dish that gets the mouth watering and can spice up just about any dish. Learn how to make your own!

by Ashton Lewis

by Ashton Lewis

42 DIY NETTING APPLICATOR

Vineyard netting is often critical to protect your grapes from birds and other predators; however, applying and removing it can be a real pain. Here is a solution for home winemakers with a utility vehicle that allows netting to mostly be installed by just one person without the net ever touching the ground.

by Ken and Leah Stafford

by Ken and Leah Stafford

2 APRIL - MAY 2022 WINEMAKER

features contents April-May 2022, VOL. 25 NO. 2 WineMaker (ISSN 1098-7320) is published bimonthly for $26.99 per year by Battenkill Communications, 5515 Main Street, Manchester Center, VT 05255. Tel: (802) 362-3981. Fax: (802) 3622377. E-mail address: wm@winemakermag.com. Periodicals postage rates paid at Manchester Center, VT, and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to WineMaker, P.O. Box 469118, Escondido, CA 92046. Customer Service: For subscription orders, inquiries or address changes, write WineMaker, P.O. Box 469118, Escondido, CA 92046. Fax: (760) 738-4805. Foreign and Canadian orders must be payable in U.S. dollars. The airmail subscription rate to Canada and Mexico is $29.99; for all other countries the airmail subscription rate is $46.99. 30 24 42 36

Sharing GOOD TIMES & GOOD WINE NEW FIN GER LAKES CABERNET FRANC ROS É New York Sign up to our newsletter MOSTI MONDIALE.COM 23L LIMITED EDITION 2022 MOSTI MONDIALE OFFICIAL DISTRIBUTOR CONCENTRATED BREWING MALTS! Enjoy Happy HOUR!

departments

8 MAIL

We answer reader questions on humidifiers for wine cellars, the sur lie aging timeline, and freezing grapes from an initial harvest when the rest of the vineyard lags behind.

10 CELLAR DWELLERS

If you’ve got a wine aging in your cellar you would like unbiased, expert opinions on, then entering it in a competition for judging is one of the best options. Get some pointers for getting the best feedback. Also check out these retro wine labels and catch up on the latest news, products, and upcoming events.

14 TIPS FROM THE PROS

When you want to make wines from grapes but it isn’t harvest season, one option home winemakers have is purchasing buckets of frozen must or juice. Three industry experts share their coolest tips.

16 WINE WIZARD

A winemaker is left scratching their head when a wine that seemingly has fermented dry is still producing bubbles. The Wizard also provides suggestions for vinegar storage and the possible cause of odd-colored speckles on a cantaloupe wine.

20 VARIETAL FOCUS

A grape of Mediterranean origins, Malvasia grapes spread throughout the region under the umbrella name. Get the scoop on this unusual family of grapes and the variety brought to North America under the title Malvasia Bianca.

48 TECHNIQUES

Approaching food-wine pairings can be complex given the nearly endless options available . . . but there is a science to it. Learn the basics to matching a wine with a food course to impress even the sticklers in the group.

50 ADVANCED WINEMAKING

Many of us in winemaking were trained to trust Saccharomyces yeast and not leave our wines to chance with wild strains. But winds of change are in the air and yeast companies are now turning to many non-Saccharomyces yeasts for certain purposes.

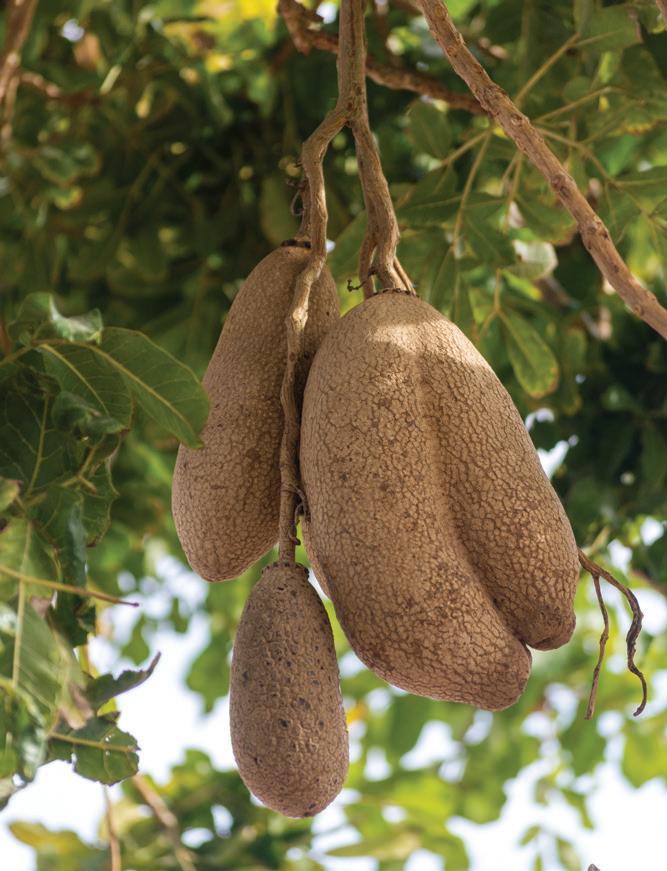

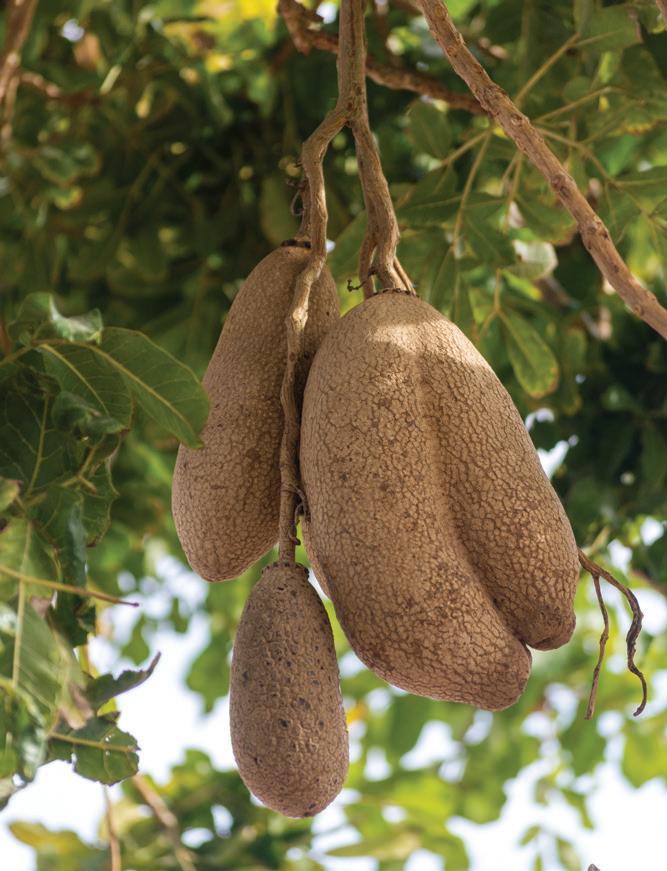

56 DRY FINISH

A group of wine lovers in Kenya turned to traditional winemaking when the world around them slowed to a crawl and imports of wines from Europe and the U.S. nearly stopped. Check out the story of muratina wine — a wine made from a potentially poisonous fruit.

4 APRIL - MAY 2022 WINEMAKER

53 SUPPLIER DIRECTORY 55 READER SERVICE where to find it ® 20 Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.com

WINEMAKERMAG.COM APRIL - MAY 2022 5 www.lallemandbrewing.com/wine FULL RANGE OF PREMIUM WINE YEAST

™

™

K1

(V1116) FRESH AND FRUITY STYLES EC1118

THE ORIGINAL “PRISE DE MOUSE”

71B

™ FRUITY AND “NOUVEAU” STYLES

D47 ™ FOR COMPLEX CHARDONNAY QA23 ™ FOR COMPLEX SAUVIGNON BLANCS

™

RC212

FOR PINOT NOIR STYLES

EDITOR

Dawson Raspuzzi

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Dave Green

DESIGN

Open Look

TECHNICAL EDITOR

Bob Peak

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Chik Brenneman, Alison Crowe

Dominick Profaci, Wes Hagen

Bob Peak, Phil Plummer, Alex Russan, Jeff Shoemaker

CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS

Jim Woodward, Chris Champine

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Charles A. Parker, Les Jörgensen

EDITORIAL REVIEW BOARD

Steve Bader Bader Beer and Wine Supply

Chik Brenneman Baker Family Wines

John Buechsenstein Wine Education & Consultation

Mark Chandler Chandler & Company

Wine Consultancy

Kevin Donato Cultured Solutions

Pat Henderson About Wine Consulting

Ed Kraus EC Kraus

Maureen Macdonald Hawk Ridge Winery

Christina Musto-Quick Musto Wine

Grape Co.

Gene Spaziani American Wine Society

Jef Stebben Stebben Wine Co.

Gail Tufford Global Vintners Inc.

Anne Whyte Vermont Homebrew Supply

EDITORIAL & ADVERTISING OFFICE

WineMaker

5515 Main Street

Manchester Center, VT 05255

Tel: (802) 362-3981 Fax: (802) 362-2377

Email: wm@winemakermag.com

ADVERTISING CONTACT:

Kiev Rattee (kiev@winemakermag.com)

EDITORIAL CONTACT:

Dawson Raspuzzi (dawson@winemakermag.com)

SUBSCRIPTIONS ONLY

WineMaker

P.O. Box 469118

Escondido, CA 92046

Tel: (800) 900-7594

M-F 8:30-5:00 PST

E-mail: winemaker@pcspublink.com

Fax: (760) 738-4805

Special Subscription Offer

6 issues for $26.99

Cover Photo Illustration: Charles A. Parker/Images Plus

Albariño. I enjoyed my first ones at WineMaker’s 2014 conference in Virginia and since then I have made an effort to seek them out. Crisp acidity, citrus and stone fruit flavors, and often a hint of salinity. I find it pairs great with many foods as well as warm summer evenings!

My choice for most underappreciated varietal is counterintuitive, big surprise from me, right?! It’s Chardonnay. I know what you’re thinking. It’s so darned ubiquitous in the U.S. as to be synonymous with white wine! But anything that gets popular enough gets maligned, and I will say without a moment’s hesitation that Chardonnay is the most noble and expressive white varietal on the planet (sorry Riesling, if I was in Germany this might go a different way), and is certainly the greatest grape we grow in the Santa Maria Valley and Sta Rita Hills AVAs.

An underappreciated varietal is Petit Verdot. While typically used for blending, I find the intense black fruit character, firm tannins, and mild astringency of Petit Verdot should be valued more as a single varietal wine. I do use a small percentage in many of my commercial blends to help fortify rich color, but seek out producers who bottle it as a single varietal for my personal enjoyment.

PUBLISHER

QBrad Ring

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER & ADVERTISING DIRECTOR

Kiev Rattee

ADVERTISING SALES COORDINATOR

Dave Green

EVENTS MANAGER

Jannell Kristiansen

BOOKKEEPER

Faith Alberti

SUBSCRIPTION CUSTOMER SERVICE MANAGER

Anita Draper

Phenolics & Tannins in White, Sparkling & Rosé Styles

Polyphenolics are usually associated with red wines, but there are definitely processing choices and stylistic options where polyphenolics play a role in whites, rosé, and sparkling wines also. https://winemakermag. com/article/phenolics-tannins-inwhite-sparkling-rose-styles

MEMBERS ONLY

The Winemaker’s Pantry: Supplies to keep on hand

For those that are regular winemakers, the accoutrements start to add up through the years. Here is a guide for folks to consider what things to keep in their “winemaker’s pantry,” their uses, and their shelf life.

https://winemakermag.com/technique/ the-winemakers-pantry-supplies-tokeep-on-hand

Special Purpose Wine Yeast

All contents of WineMaker are Copyright © 2022 by Battenkill Communications, unless otherwise noted. WineMaker is a registered trademark owned by Battenkill Communications, a Vermont corporation. Unsolicited manuscripts will not be returned, and no responsibility can be assumed for such material. All “Letters to the Editor” should be sent to the editor at the Vermont office address. All rights in letters sent to WineMaker will be treated as unconditionally assigned for publication and copyright purposes and subject to WineMaker’s unrestricted right to edit. Although all reasonable attempts are made to ensure accuracy, the publisher does not assume any liability for errors or omissions anywhere in the publication. All rights reserved. Reproduction in part or in whole without written permission is strictly prohibited. Printed in the United States of America. Volume 25, Number 2: April-May 2022.

Yeast are fairly simple, singlecelled organisms. But their diversity, functionality, and ability to adapt is why humans, and especially winemakers, love these fungi so much. Take a peek at several strains that winemakers should know are available. https://winemakermag. com/technique/special-purpose-wineyeasts

MEMBERS ONLY

Cooking With Wine

Your homemade wine doesn’t have to be simply for the wine glass — it can also be a part of the food on your table! Check out three recipes for a French-inspired feast that count wine among the ingredients. https://winemakermag. com/article/1549-cooking-with-wine

MEMBERS ONLY

* For full access to members’ only content and hundreds of pages of winemaking articles, techniques and troubleshooting, sign up for a 14-day free trial membership at winemakermag.com

6 APRIL - MAY 2022 WINEMAKER WINEMAKERMAG.COM suggested pairings at ®

WineMakerMag @WineMakerMag @winemakermag

An underappreciated wine grape varietal. . . choose one and tell us why.

WINEMAKERMAG.COM APRIL - MAY 2022 7

Phil Plummer has been a student of wine since 2004 when he began his formal education in the subject at Rochester Institute of Technology. For the past 11 years, Phil has worked for the Martin Family Wineries (Montezuma, Idol Ridge, and Fossenvue) in New York’s Finger Lakes Region, serving as Head Winemaker since 2013. In his time as Head Winemaker, he has developed a diverse portfolio of unique wines made from grapes, fruit, and honey. Phil’s passion for wine and winemaking is boundless, as evidenced by his constant experimentation with new techniques, materials, and mindsets.

Starting on page 30, Phil details the various ways to make dry rosé wines that are perfect for summer sipping.

HUMIDIFIER HELP

I need some guidance in choosing a humidifier for a small wine chamber. Are there any articles about this, or is there someone who can offer any advice?

John Pocs • via email

WineMaker’s Technical Editor Bob Peak responds: “I actually included a couple of paragraphs on this subject in a previous column ‘Maintaining a Home Wine Cellar’ that is available online at https://winemaker mag.com/technique/maintaining-home-wine-cellar

“I do not need to add humidity in my wine cellar; our coastal climate keeps it between about 50 and 60% all the time. I have had to add humidity to my cheese cave (a small fridge) at times to make moldy cheese (blue or brie). For that, I put water in a shallow tray and then set a large sponge in the water. The large surface area of the sponge facilitates evaporation into the cave space. When I was making more cheese a few years ago, I bought a reptile terrarium humidifier to automate it. The one I bought — Zoo Med Reptifogger Terrarium Humidifier — was about $50 and ideal for a small space. For a larger space, up to whole house, you can get a humidifier with a built-in digital humidistat.

“If you don’t want to keep refilling it and have a nearby water connection, you can install one like this one for less than $300, but you need to add a separate controller to make it automatic: https://amzn. to/3BrqotX”

SUR LIE AGING

I found the article “Sur Lie Aging” by Alex Russan in the June-July 2021 issue very informative and I hope to ask Alex a question on the subject. I’ve always racked off the gross lees and usually allow the fine lees to remain to help with the malolactic fermentation. You mentioned this under the heading “Lees and ML.” A bit further in your article under the heading “Lees and Red Wines” you mention how it is important to separate the fine lees from the red wine early in the process, and later put the lees back around six months after the fermentation, which is the stage when most of the polymerization has taken place. So can you please let me know if it is OK to hold off on removing the fine lees at the moment when I’ve started the ML fermentation so that the ML bacteria can benefit from it for about a month or two for it to complete, without causing less than

Bob Peak is a retired partner of The Beverage People Inc., a home winemaking and homebrewing shop in Santa Rosa, California. Before The Beverage People, he was the General Manager at Vinquiry, a company that provides analytical services to the wine industry. Bob has authored the “Techniques” column that runs in every issue since 2013, frequently writes feature stories, and has been the Technical Editor of WineMaker since 2017. He is also a frequent speaker at the annual WineMaker Magazine Conference.

In addition to his usual “Techniques” column on food and wine pairing (page 48), Bob also explains which gases are best used for different chores in the winemaking process in the feature story beginning on page 24.

Ken and Leah Stafford are award-winning amateur winemakers who have been around the wine industry for most of their lives. Having grown up on a Delano, California winery, Ken began making wines in 2011. Leah has worked in the industry since 1990, servicing and managing tasting rooms and providing wine education. She’s a certified American Wine ExpertTM, WSET 1, 2, 3 educated, a wine judge, and holds other certifications within the wine industry. In 2015, the couple moved to a 5-acre property that had an existing vineyard where they are now growing and making estate wines from Zinfandel, Barbera, Petite Sirah, Grenache Noir, and Sauvignon Blanc. Among those wines produced, the Sauvignon Blanc won Best of Show Estate Grown in the 2021 WineMaker International Amateur Wine Competition.

They make their WineMaker writing debut on page 42 sharing their simple solution to the challenges of applying and removing netting to the home vineyard.

8 APRIL - MAY 2022 WINEMAKER contributors

MAIL Calibrating Wine Testing Equipment Pro Tips For Hybrid Winemaking Award-Winning Home Wine Labels WHAT’S IN A NAME? MAKING CHARBONO/ BONARDA/DOUCE NOIR BACKYARD VINEYARD QUESTIONS ANSWERED KEYS TO BLENDING VINIFERAS & HYBRIDS TECHNIQUES FOR CRAFTING GREAT WINE FROM EXPERTS IN FRANCE, NEW ZEALAND, AND THE UNITED STATES FEBRUARY-MARCH 2022 VOL.25, NO.1

ideal polymers and without suppressing the color? Will waiting for about two months cause any harm? I’m afraid that by removing the fine lees I can starve the bacteria or disturb everything, or should I just wait about five days after racking off the gross lees so the fine lees settles, then remove it, and at that point start the malolactic fermentation without the fine lees?

I have had the two problems you mention happen with a Cab where I had left the fine lees for the first six months, and I have experienced incredible benefits from aging on lees from leaving the lees right from the beginning on a Tempranillo without affecting the color or complexity of the wine. I know I was very lucky with the Tempranillo, and not so fortunate with that particular Cab.

Robert St-Jean • Cantley, Quebec

Alex Russan responds: “To be sure, leaving the lees in the entire time won’t harm or damage anything, they’ll just adsorb color, which would otherwise have gone into your wine’s structure. What you describe wanting to do is totally fine from a do-no-harm point of view. But if the goal is to have as sturdy and long-lived wine as possible, or to maximize softness as the wine ages, it may not be ideal for maximizing what could be done — but it’s not hurting anything. The difference it would have made had you done the fine lees removal earlier is probably subtle, so the decision is not going to make or break the wine. I’d leave it alone, as again, you’re not hurting anything, just sacrificing some color that could have been used by the wine.”

Join

STORING GRAPES

I have an extremely small hobby vineyard of about 30 vines (mixed varieties) and find it hard to get help here in the U.K. with either advice or supplies and I rely heavily on your magazine. I envy you in North America where you seem to have a lot of amateur growers and resources to match. Last year the weather was very unusual and fruit growth was poor. I had some grapes that ripened early while others of the same variety in a different part of the vineyard were well behind them. Could I have picked the ripe ones and frozen or chilled them and waited until the rest were ready to crush so that I could process them all together?

David Lodge • via email

The short answer is that freezing them would be the best option. But there are some nuances and things to consider in this process, which Alison Crowe covered well in a previous “Wine Wizard” column found here: https://winemakermag.com/wine-wizard/freezing-grapes

SEND YOUR QUESTIONS TO WINEMAKER

Do you have a question or comment about something you’ve read in the pages of WineMaker magazine or online at winemakermag.com, or a story or idea to share? Send your letters, photos, story ideas, and projects to edit@winemakermag.com, post them on WineMaker’s Facebook page (https://www.facebook.com/WineMakerMag), find us on Twitter: @WineMakerMag, or share your winemaking photos and videos with us on Instagram: @WineMakerMag.

CHILE & ARGENTINA WINERY & MULTI-SPORT TOUR with WineMaker

March 12 – 19, 2023

Join WineMaker Magazine during the Southern Hemisphere’s grape harvest to explore five wine regions in Chile (Maipo, Apalta, Colchagua, Casablanca, and Aconcagua) and three in Argentina (Maipú, Uco Valley, and Luján de Cuyo). We’ll visit everything from beaches to valley vineyards to the peaks of the Andes. You’ll have insider tours of wineries meeting the people behind the wines, walk through vineyards with breathtaking views, and ride bikes on beautiful side roads surrounded by acres of grapevines. Plus we’ll hike at the base of Mount Aconcagua, the highest mountain in the Americas, horseback ride, and raft the Mendoza River. All along you’ll eat outstanding local food, experience the culture, and enjoy wines like Malbec and Carménère right at the source.

For more details visit: winemakermag.com/trip

WINEMAKERMAG.COM APRIL - MAY 2022 9

MAIL

WineMaker for the South American Harvest in 2023!

RECENT NEWS UPCOMING EVENTS

Great News For California Grape Growers

The 2021 California crush report was released in midFebruary and found that total wine grape production was up 6% over the 2020 harvest, coming in at 3.6 million tons. Red wine production saw the bulk of the increase, up 10.6% over 2020, while white wine grapes were up a marginal 0.3%. Despite the seeming “glut” of grapes, price per ton also saw a marked uptick. Red wine grape prices were up an astounding 32% while white wine varieties were up 19.7%. This is a big reversal in the trends of grape prices over the previous several harvests when overproduction of wine seemed an issue for grape growers.

https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/California/Publications/Specialty_ and_Other_Releases/Grapes/Crush/Reports/index.php

New Products: Twisted Mist™

A new line of summer wine kits is being offered by Winexpert with a modern twist on wine. These fruit-forward, cocktail-inspired kits will offer six different limited release flavors, with two flavors being released each month through March, April, and May. Flavors include: Piña Colada with pineapple and coconut character; Sex on the Beach with flavors of orange juice, peach, vodka, and cranberry; Pink Lemonade features lemons for a taste of pink lemonade; Strawberry Lemonade mixes strawberry with tart lemonade; Hurricane features flavors of dark rum, orange, lime, and passion fruit; Miami Vice is a blend of strawberry, pineapple, lime, and coconut. All Twisted Mist™ flavors are limited release and available only while supplies last.

MAY 28,

2022

Entry Deadline for the Orange County Fair Home Wine Competition. This competition is only open to amateur winemakers who live in California. The cost is $18 per entry and entries must be received by May 28. For more information about entering your homemade wines, visit: https://homewinecompetition.com

The World’s Largest Collection of Country Wine Recipes

A new book by winemaker and biodynamic wine advocate Chuck Blethen is a comprehensive recipe book for all those winemakers with interest in country wines. Through his decades of business travels, Chuck started work on this book long before he knew it would ever come to fruition, bringing home recipes from far and wide, utilizing all sorts of garden, orchard, or foraged ingredients. Featuring 195 recipes, it also contains useful conversion charts and know-how from his 40 years making wine. You can find out more information about the book or order a copy at https://wp.jeweloftheblueridge.com/

JUNE 2 & 5,

2022

Spots are still available for the 2022 WineMaker Boot Camps taking place Thursday, June 2 and Sunday, June 5 in San Luis Obispo, California. With nine Boot Camps to choose from, there is something for all levels and winemaking styles. Learn more at: https://winemakermag.com/conference/conference-overview

10 APRIL - MAY 2022 WINEMAKER

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.com

Chardonnay

GOLD

RJS Craft Winemaking Australian Chardonnay

SILVER

VineCo Atmosphere Chardonnay

Winexpert Private Reserve Dry Creek Valley Sonoma Chardonnay

Winexpert Select Chardonnay

BRONZE

VineCo Estate Australian

Chardonnay

VineCo Original Series Chardonnay

Pinot Grigio

SILVER

VineCo Original Pinot Grigio

Winexpert Limited Edition Pecorino

Pinot Grigio

Winexpert Vintners Reserve Italian

Pinot Grigio

BRONZE

Winexpert Classic Italian Pinot

Grigio

Sauvignon Blanc

GOLD

Winexpert Private Reserve

Sauvignon Blanc

tradition.

SILVER

Mosti Mondiale AllJuice Sauvignon Blanc

Winexpert Limited Edition Fume Blanc

BRONZE

VineCo Original Series Sauvignon Blanc

Winexpert Classic Chilean

Sauvignon Blanc

Winexpert Private Reserve New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc

WINEMAKERMAG.COM APRIL - MAY 2022 11 AWARD-WINNING KITS

PREMIER CUVEE • PREMIER BLANC • PREMIER COTE DES BLANCS • PREMIER CLASSIQUE • PREMIER ROUGE A Fermentis brand FIND OUR PRODUCTS IN YOUR LOCAL HOMEBREW /HOME WINE MAKING SHOP

Here is a list of medal-winning kits for the Chardonnay, Pinot Grigio, and Sauvignon Blanc categories chosen by a blind-tasting judging panel at the 2021 WineMaker International Amateur Wine Competition in West Dover, Vermont:

Our Red Star range is evolving. New names, the same

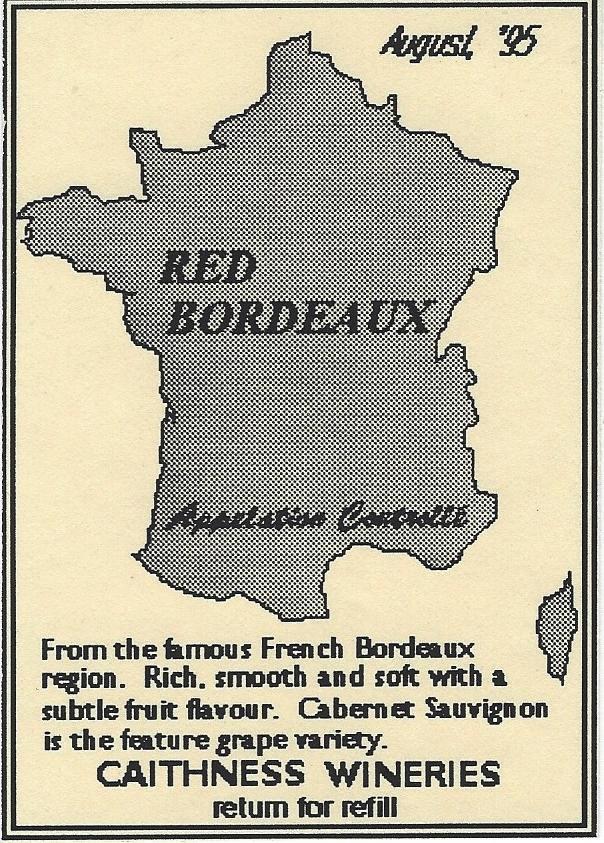

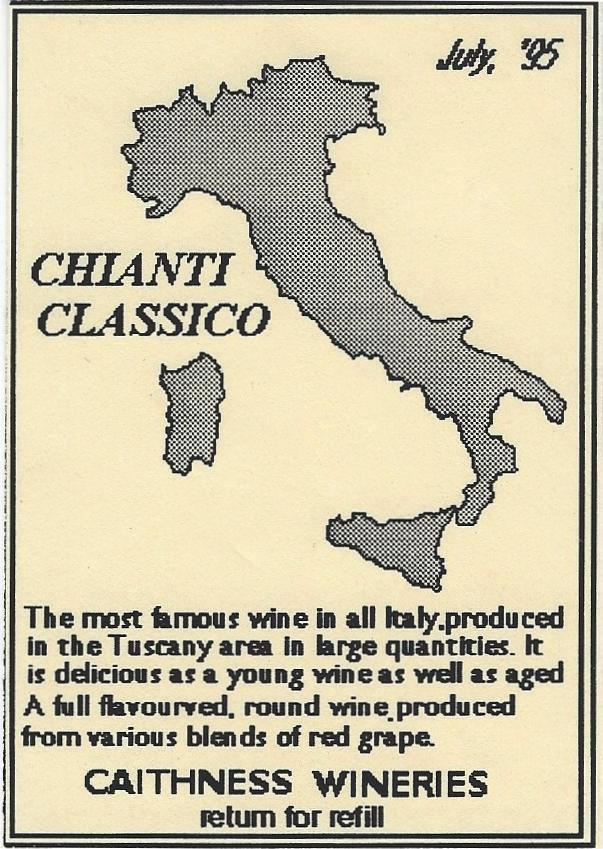

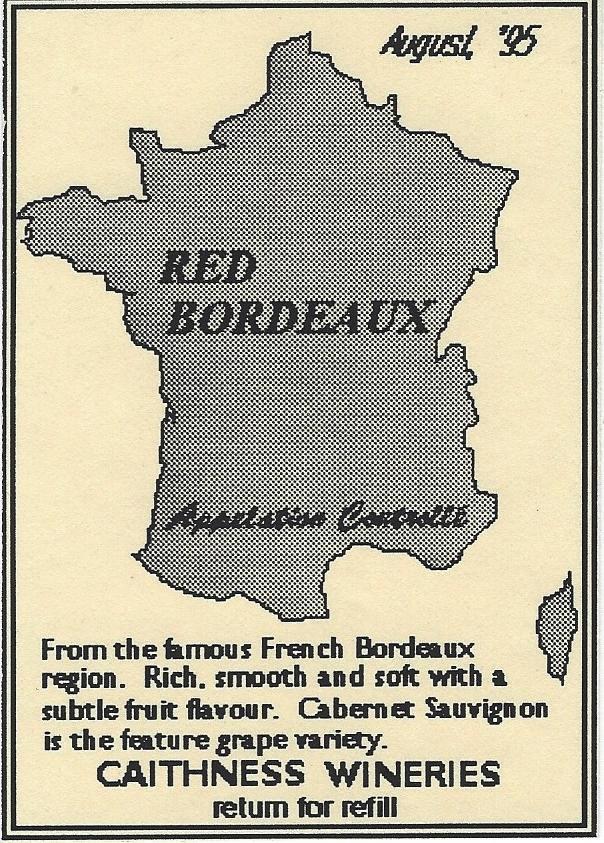

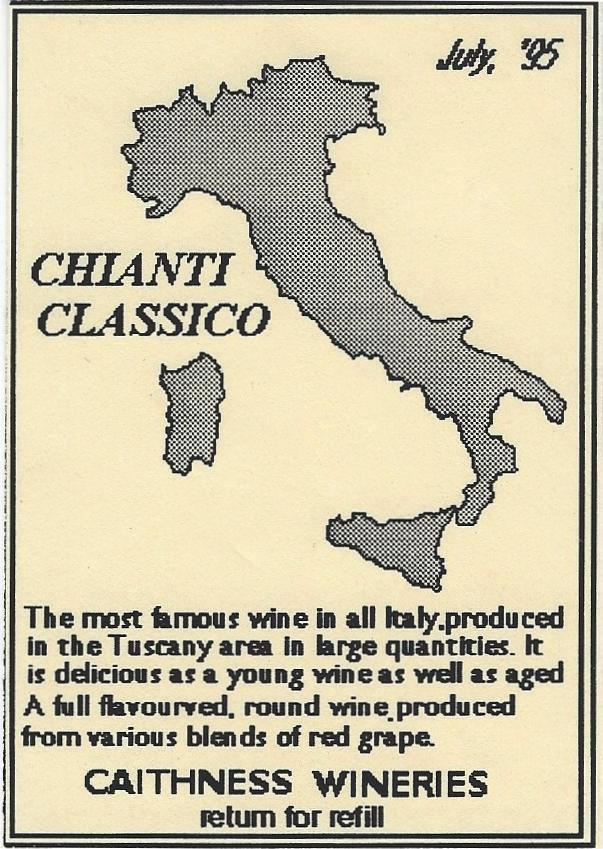

Iwas looking through my labels bin for this year’s wine label contest and stumbled across these old custom labels I made in the summer of 1995. I recall thinking I was so proud of what I could do on my new computer! It was a brand new Compaq with a 500 MB hard drive and 4 MB of RAM, and a fresh copy of Windows 95. I also bought a new Citizen Dot Matrix Printer. The whole outfit set me back about $4,600, which is about $8,330 in today’s dollars (think about how much technology you can get for that today). It was the luxury coupe in the tech world back then and I couldn’t wait to give it a test drive.

I created these on the built-in Windows Paint program and each one took me about 90 minutes to make. Amazing how far technology has come looking at some of the label contest entries made over the past few years. But if you’re into that retro look (think like the game Minecraft), then I hope you can appreciate these labels. Cheers!

12 APRIL - MAY 2022 WINEMAKER THE STORY BEHIND THE LABEL CAITHNESS WINERIES

QUALITY, FRESH PRESSED GRAPE JUICE VINIFERA - FRENCH HYBRID NATIVE AMERICAN 2860 N.Y. Route 39 • Forestville, N.Y. 14062 716-679-1292 (FAX 716-679-9113) OVER 20 VARIETIES OF GRAPE JUICE... PLUS Apricot, Blackberry, Blueberry, Cherry, Cranberry, Peach, Pear, Plum, Pomegranate, Red Raspberry, Rhubarb and Strawberry We Ship Juice in Quantities from 5 to 5000 gallons WALKER’S... GROWING SINCE 1955, SUPPLYING AWARD WINNING JUICE TO OVER 800 WINERIES IN 37 STATES Walkers Qrtr-pg Ad.qxp_Layout 1 12/3/18 9:33 AM Page 1 www.walkerswinejuice.com (For inquiries email jim@walkerswinejuice.com) SCOT CAITHNESS • CALGARY, ALBERTA

BEGINNER’S BLOCK

BY DAVE GREEN

Prepping Wine For Competition

Generally there are three reasons we enter our wines into a competition. The first is for confirmation that the wine being produced in your winery is good quality and to obtain feedback to see if there are ways to continue to improve them. The second reason is to try to troubleshoot some character flaw in a wine that you can’t route out, whether it’s from a specific batch of wine or a recurring character. A third reason is to compete for medals and recognition against fellow hobbyists to see where your skills stack up. No matter what your reason for entering a specific wine in the next local, national, or international competition may be, there are a few things we should all adhere to when getting ready to send our wines to a competition.

PRE-BOTTLING

There is not much here that is outside your standard sound winemaking practices. A proper aging period is advisable, tasting periodically to track the progress of the wine. During aging both a heat and cold stabilization process should be included. Since your wine may see extreme temperatures out of your control, it’s best to mitigate these problems.

Regularly topping up the vessel while maintaining sulfite levels will give you the best chance of producing a clean wine. Oxidized wine is one of the most common flaws seen in amateur wine competitions and can be best avoided by topping up and keeping up on metabisulfite additions. Use your phone or computer to set monthly, or even bi-weekly, reminders.

Finally, be sure the wine sees an appropriate fining and/or filtration, or even a de-gassing, especially if you would like to enter a younger wine in a competition. Appearance is the first thing judges note when a wine is presented.

BOTTLING

When it comes to bottling, there are a few keys to getting it right. First off, you should not be doing anything to the wine on bottling day other than transferring into the bottle and sealing it up. Any final additions, blends, or other adjustments to the wine should have been done at least a week prior to bottling. (A final sulfite addition may be the only exception to this rule, but even with sulfite, it should be done at least two days prior to bottling.) You want to make sure the wine has time to integrate any of these changes with proper time to settle precipitates that may form.

Make sure your bottles are spotlessly clean; bio-films can easily be removed with the proper cleaning solution such as One-Step. If using corks, double check to make sure that they are the appropriate size for the bottles and they are not dried out if using natural corks. If you are shipping wines for competition, the bottle(s) will be out of your hands for a time. Making sure the closure is properly sealing the wine in and keeping oxygen out can assure you a cleaner assessment of your wine.

ENTERING YOUR WINE

So you’ve got a wine that you want evaluated. Resist the urge to send any wines that have just been bottled. Bottle shock is a real phenomenon and wine should not be evaluated for at least 30 days post-bottling day. Also, if you added too much sulfite near bottling to a red wine, it can have a bleaching effect. This is reversible, so giving the wine proper time in the bottle is important. White and rosé wines may be ready within a few months post-bottling, but you should probably wait upward of a year post-bottling to enter most red wines into a competition.

Selecting the correct category is fundamental to get an appropriate assess-

ment of your wine. Having now worked as part of the team on the WineMaker International Amateur Wine Competition for 14 years, it still surprises me how many times wines will be entered into the wrong category. Make sure you have an understanding of the various categories, the varieties in your wines’ origins, blending requirements; all with an eye towards the category’s key expectations. If you are entering a wine in the Merlot category, expectations are that it is a red wine with at least 75% of the grape blend being Merlot. Blush/ rosé wines have their own categories and should not be entered to be judged against their red counterparts.

WINE SHIPPING

One positive about entering wines in a local competition is that you avoid the cost of shipping. But to enter your wines in larger national or international competitions, this cost is often unavoidable. The first order of business when it comes to shipping wines is the packaging. Since the cost of shipping has gone up as high as it has in recent years, we highly recommend you don’t skimp on your packaging material. Purchasing packaging specifically for shipping wine will spare you the worry of, “Will my wines make it safely?”

Finally make sure all your paperwork is filled out cleanly and both it and the registration payments are easily visible to the person unpacking your wines. Each wine bottle should be properly marked to make it clear to those who process the wines. A Post-It® flag left hanging on the side of a bottle is probably not a smart idea. Also, this task should not be done after opening your second bottle of wine for the night. While this step may not be rocket science, you’re much more apt to miss key details with a foggy mind.

We wish you the best if you plan to enter a wine competition!

WINEMAKERMAG.COM APRIL - MAY 2022 13

BY DAWSON RASPUZZI

TIPS FROM THE PROS WINE FROM FROZEN MUST

An option that is always in-season

Buckets of frozen must or juice allow winemaking season to be any time of the year. These juices are not concentrated and there is minimal intervention beyond flash freezing the grapes on the crush pad. Interested in exploring this option? Heed the advice from these three experts in the business.

Frozen grape buckets allow you to make the wine you want to make, when you want to make it. There is no appreciable difference between the resulting wines made from fresh grapes and those made from frozen must or juice. Several studies have shown a small increase in total phenolics from frozen grapes, but so far none have demonstrated a sensory impact.

The grapes are treated the same way they would be at a winery, except instead of starting fermentation they are put into buckets and flash frozen. Our reds have nothing added to them and only the stems are removed. The whites receive 75 parts per million SO2 at pressing. Our white juice pails contain 5.25 gallons (20 L) of settled juice and yield 5 gallons (19 L) of finished wine. Our red pails contain 5 gallons (19 L) of must and usually yield 3.5 gallons (13 L) of finished wine, but anywhere between 3–4 gallons (11–15 L) is normal depending on varietal and pressing.

Once they’re in the freezer, the pails are held below 0 °F (-18 °C) and the contents don’t change very much from that point — so they have a very long shelf life. After a few years there may be some visible oxidation on the surface, but so far no one has reported a pail “going bad” in the freezer.

Once received, the buckets should be thawed at 65–75 °F (18–24 °C). At this temperature it should take 1–2 days to completely thaw and reach a temperature suitable for fermentation. Thawing at colder temperatures will take longer, which gives wild microbes a better chance at corrupting the juice. Thawing or fermenting at warmer temperatures

can risk cooking off some of the flavors. If you’re in a hurry, a warm water bath is the fastest way to effectively thaw a pail. There is no need to do a cold soak with previously frozen grapes. The freezing process ruptures some of the skin cell walls releasing more polyphenols into juice than cold soaking ever could! After quickly thawing the must or juice, pitch a cultured yeast rather than relying on native yeasts that will survive, but not thrive, the freezing process.

All of the buckets come with the listed Brix, pH, titratable acidity (TA), as well as other measurements and origin information. These measurements we post are an average taken from all the bins. There is usually some variation with the reds because the bins of grapes are individually fed into the destemmer and then flow directly into the buckets. So any bin-to-bin variation would also be reflected in the buckets. Usually the bins are all within +/-1 °Brix of the posted measurement. Also, as the reds soak on the skins some additional sugar and potassium can be released into the juice, causing the Brix and pH to rise. The numbers we post for the white juices are tank samples after all the grapes are blended together so the numbers are quite reliable. But it is always advisable to take your own measurements before making any adjustments.

The buckets the grapes come in are food-grade, however red wine ferments need 30% extra volume in the fermenter for the cap of skins to rise into, which means that a red ferment would overflow in the bucket! There is enough space to ferment whites, but be sure to transfer to a carboy before fermentation is complete to prevent oxidation.

14 APRIL - MAY 2022 WINEMAKER

The grapes are treated the same way they would be at a winery, except instead of starting fermentation they are put into buckets and flash frozen.

Brothers Michael and Andrew Crews are the Owners of Wine Grapes Direct, which sources, freezes, and delivers grapes from vineyards across California, Oregon, and Washington to home and commercial winemakers.

Making wine from frozen must or juice has many benefits, none more important than reliability and flexibility. You get grapes that are harvested at their prime for winemaking and have an idea about the chemical analysis of the grape ahead of time. Considerations of logistics for shipping to the ultimate winemaker are done with grapes or juice that is stable, not degraded or compromised in quality.

There are many other benefits too: You can make your wine on your schedule — no need to worry about missing harvest if you want to travel in the fall. It also allows the easy ability to make blends or co-ferment with different varietals, vintages, and vineyards. And you can make the same wine twice if you find out you loved the first batch when it was complete (assuming the juice is still in stock).

Most of these benefits listed so far have been for the convenience of the home winemaker. A benefit to the wine itself, though, is that there is a slight increase in color and yield from the freezing and thawing process. The freezing is basically a cold soak on steroids. Starting cold may be a lot easier than with fruit at 85 °F (29 °C). Frozen juice allows you many more options than fresh juice as well. The ice that forms and floats during the juice thawing is water. An undisturbed pail of thawed juice will be 6 °Brix on top and 40+ °Brix on the bottom. Potassium combined with the tartaric acid will create cream of tartar on the floor of the pail. These natural separations make accurate analysis of the juice or grapes initially difficult, however, it also allows for the production of ice wine or natural acid reduction. One juice — many possibilities.

Our red buckets are 6-gallons (23-L), filled with 5 gallons (19 L) of must and make 3–3.5 gallons (11–13 L) of wine. These grapes are gently destemmed and flash frozen. White grapes are whole bunch pressed at a low pressure in a pneumatic press. The white juice is chilled, settled, and racked off the gross lees into 6-gallon (23-L) buckets filled with 5 gallons

(19 L) of juice.

As a grape grower and grape buyer we prefer vineyards with sustainable, regenerative practices. Certainly what happens in the vineyard goes all the way to your bottle of wine. The basic goal is to provide the winemaker with grapes as they were when harvested. We freeze them in time. The addition of sulfite is seldom used. If used, the addition is noted, and usually quite low. An exception would be grapes heavily infected with Botrytis. This juice will have sulfite and other additives if deemed appropriate. With time, frozen juices that are not sulfited will become dark in color and become oxidized. The freezing process reduces the juice’s fauna and the wine ferments without fear of spoilage. The yeast consume the oxygen and near the end of alcohol fermentation the oxidized color will fall out. There is no aroma impact, and the result is a wine more resistant to oxidation.

When you receive your grapes, take the lids off and inspect them for any freezer burned or moldy grapes. Remove any grapes that are questionable. As soon as possible submerge the skins in the juice at least once per day — if you leave undisturbed and mold forms, pick it out and discard. Keep it covered.

Under no circumstances should you let your grapes thaw slowly in a refrigerated environment. You want to thaw the grapes quickly and evenly. Room temperature, 70 °F (21 °C), is ideal for thawing. Start preparing your yeast early. While there are native yeast that survive the freeze, it is recommended that a strong yeast starter be added to the must or juice. Instead of a 103 °F (39 °C) rehydrated yeast and 80 °F (27 °C) must, you have a 40 °F (4 °C) must. Your goal is to have the temperature of your yeast starter and must within 10 °F (5 °C) of each other. Start your yeast while the grapes thaw. Gradually feed the watery, cold defrosted juice to the starter. As the yeast acclimates to a cold environment the must/juice warms to a temperature within 10 °F (5 °C) of the must/juice, submerge the skins, keep juice agitated. Do not cold shock the yeast.

WINEMAKERMAG.COM APRIL - MAY 2022 15

Peter Brehm has been in the wine industry for more than 40 years and has taught thousands of people the techniques of winemaking. He developed the industry standard for flash freezing grapes and published the results in 1974. A decade later he started Brehm Vineyards, exclusively selling wine grapes from California and the Pacific Northwest, which he continues to operate today.

WINE WIZARD

BY ALISON CROWE

FERMENTATION COMPLETION

Also: Vinegar storage space and cantaloupe wine

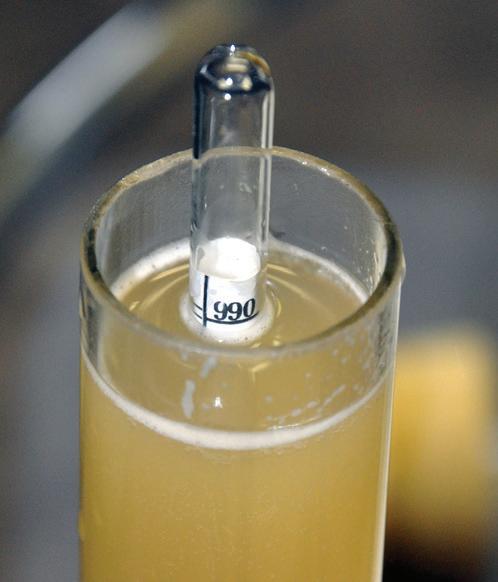

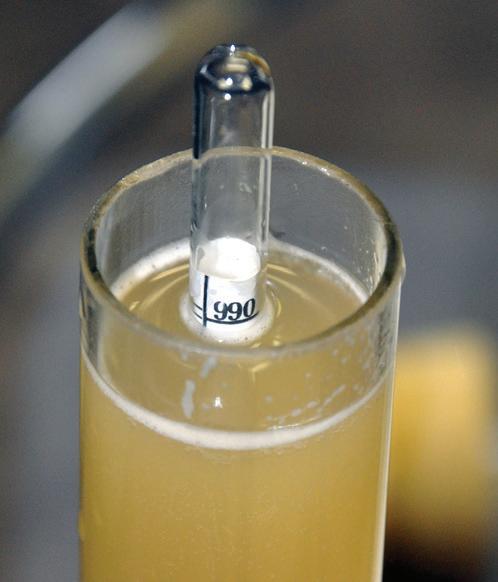

QWHAT IS A GOOD RULE OF THUMB TO CONCLUDE WINE FERMENTATION IS COMPLETE? I HAVE RECEIVED THE SAME READING FOR SEVERAL DAYS IN A ROW BUT STILL SEE BUBBLING AT THE TOP OF MY CONTAINER. THE SPECIFIC GRAVITY IS RIGHT BELOW 1.000 BUT I HAVE HEARD IT NEEDS TO GET BELOW 0.995. IS THIS TRUE?

ALSO, WHAT IS GOOD PROTOCOL AFTER FERMENTATION HAS COMPLETED? WOULD YOU RECOMMEND CHILLING DOWN TO 50 °F (10 °C ) THEN RACKING?

AIt certainly sounds like you are getting into the dryness zone. Specific gravity is the ratio of the density of a liquid in relation to the density of water, calibrated at a specific temperature (usually 60 or 68 °F/16 or 20 °C). Depending on which source you check (various winemaking books, websites, etc.) folks seem to agree that “dry” table wine usually clocks in around 0.990–0.996 specific gravity.

Why the range? Every wine is different and as such, every wine does actually contain a small amount of non-fermentable sugars and it’s unusual for a wine to go so low as to achieve “no sugar” 0.00 g/L glucose + fructose. “Dry” is philosophically defined (in my opinion) as not enough sugar left to taste or that any yeast cell will ferment as well as the place where the fermentation naturally stops and the yeast just can’t ferment anymore. Most professional winemakers I know chemically define this point as 2 g/L residual sugar (RS) or less (<0.2%) though I have seen wines naturally settle at around 3 g/L RS or 0.3%.

Also don’t forget that specific gravity (SG) is a measure of density. There are a lot of things other than water and sugar

that can affect the density of a wine so be sure you’re accounting for as many of those as you can. What is your wine sample’s temperature? As stated earlier, SG is usually calibrated against water at 60 or 68 °F (16 or 20 °C) measuring a specific gravity of 1.000 (check yours to make sure this is correct). If your wine is warm, it’ll be artificially less dense, and your reading will be off. Similarly, if your wine is colder than 60 °F (< 16 °C) it’ll be artificially dense and the hydrometer will float higher than it should. For this reason it’s important to check a hydrometer temperature correction chart to get an accurate reading. Carbon dioxide bubbles can also attach to the hydrometer, floating it artificially high, so do be sure to give it a spin in your measuring cylinder to dislodge them. Also make sure you’re reading the hydrometer line at eye level. If you look down on your hydrometer from above it can give a slightly skewed reading as a result.

If you’re following all of these good hydrometer-use tips and are seeing the same measure day over day, it’s likely your fermentation is finished. Have you ever heard of the Clinitest (sometimes called “the sugar pill”) method for testing for residual/fermentable sugar? You can

16 APRIL - MAY 2022 WINEMAKER

BRENT MOONEY FOREST HILL, MARYLAND

Every wine is different and as such, every wine does actually contain a small amount of nonfermentable sugars and it’s unusual for a wine to go so low as to achieve ‘no sugar’ 0.00 g/L glucose + fructose.

Photo courtesy of Tim Vandergrift

While the density of water at room temperature is 1.000 standard gravity, finished dry wine should be less dense than that.

buy little tablets that diabetics use to check their urine for sugar. By dropping a Clinitest tablet into a measured sample of your wine, and comparing the resulting color to a calibrated chart, you can see if there are any residual reducing sugars in your wine. This is a great (and quick, cheap, and easy) way to see if you’re dry or not once you start getting below 0.990 on the good ol’ hydrometer. Do be aware, however, that the tablets (copper sulfate is part of what makes them react) will also react with many of the pigments and phenolics in red wines, so red wine results tend to skew a little higher than white wines. You can help work around this by diluting a sample of red wine and multiplying the result accordingly. Please do realize that Clinitest tablets are *not* meant for internal consumption; they are poisonous so do not drink the test sample and be sure to keep away from pets and curious kids. Even if you’re still seeing bubbles on the top of your fermenter, it could just be carbon dioxide gas that’s escaping naturally or it could also mean you have a simultaneous malolactic fermentation going on, so gas bubbles are not always the best indicator at this stage. Assuming your wine is dry, what’s the best protocol for the

next step? You don’t mention what kind of wine you’re making in your question, but I’ll assume just for fun it’s a dry red table wine that you’d like to go through malolactic fermentation (MLF) and which you’re planning on storing in carboys with oak beans (or chips or sticks) for aging. Chilling the wine down is fine and will help settling, but if you do want it to go through the MLF that’s not a step that I recommend. Malolactic (ML) bacteria are inhibited by cold temperatures below 65 °F (18 °C). If you’re pretty sure the wine is dry, then let it sit for a few days to let the lees settle and rack off the heaviest lees into another clean, gassed container. I often use the phrase, “If it flows, it goes” to describe this phase — taking the light and medium lees (discard the heavy, sticky lees) is good for wine because they will break down later in the wine, helping to create a fuller, rounder mouthfeel. At this stage, in the carboy it’ll be sitting in for a while, I recommend adding about 55 grams of oak chips or beans per 5 gallons (19 L) of wine, which is about 3 g/L. Let the wine sit on the oak for two to three months, then taste it again and see if you’d like to add more. Be sure to keep your containers topped up — a topped wine is a happy wine!

QI AM GOING TO START MAKING SOME RED WINE VINEGAR. I KNOW, HOW DARE I ACTUALLY INTRODUCE VINEGAR INTO MY WINES . . .

SO, I HAVE EVERYTHING SET UP FOR MY VINEGAR STORAGE ( A 5- L/5.3 QT. OAK BARREL ) AND THE WINE’S READY TO GO INTO THE CONTAINER. MY QUESTION IS WHERE CAN I KEEP THIS SET UP? OBVIOUSLY, IT WILL NOT BE IN THE BASEMENT WITH MY WINE ROOM.

IS THE 1ST FLOOR A SAFE OPTION? IN OTHER WORDS, IS THAT FAR ENOUGH AWAY TO KEEP THE WINE ROOM SAFE FROM CONTAMINATION? THE ONLY OTHER PLACE I HAVE IS ON THE SECOND FLOOR IN THE BEDROOM/ EXERCISE AREAS AND I’M NOT TOO EXCITED ABOUT BREATHING VINEGAR THROUGH THE NIGHT. I HAVE A GARAGE, SHED, AND PORCH BUT THEY ARE LIKELY TOO COLD TO BE AN EFFECTIVE STORAGE/MAKING AREA. SHORT OF GOING TO SOMEONE ELSE’S HOME WHO IS NOT MAKING WINE, WHAT WOULD YOU RECOMMEND?

SUSAN HAMMOND EAST GREENWICH, RHODE ISLAND

AYou got a chuckle out of me. Indeed, how dare you introduce vinegar to your wines! I’m actually very happy that you’re writing so you can learn how *not* to introduce vinegar to your wines and in fact it seems like you’ve put a lot of thought into it. As many of my readers will know, wine turns into vinegar through the action of a group of bacteria known as Acetobacter, which eat alcohol and turn it into acetic acid, the sour yet pleasantly palatable acid that gives vinegar its “zing.”

Acetobacter are literally everywhere. They hang out on everyday surfaces, they live on our kitchen counters, they even hang out in the air we breathe. They’re so ubiquitous that it’s unlikely that you’ve got a room anywhere in your house that’s free of them. In fact, I’d wager your own basement wine room is the place with the highest cell count, because Acetobacter will naturally colonize in higher numbers where the “food”, i.e., your wine, is. With that being the case, you ask, why even try to keep the vinegar stored somewhere else? The simple and intuitive answer of which you’re already aware is that your vinegar fermentation area, where you’ll be actively encouraging a flour-

ishing Acetobacter colony, will soon become a population center to outrival even the darkest, dampest corner of your basement.

So yes, it does make sense to make your vinegar far, far away from where you make your wine. Ideally, this would be in a separate building, which could be kept at the temperature needed for good vinegar production, 60–80 °F (16–27 °C). Because the inside of your house will have its interior air in communication with your basement (even if you mostly keep the doors closed) it’s going to be that much harder to keep the “bad” bacteria away from your wine. It’s not just the air that can spread Acetobacter. Every time you (or the dog or cat) pass through the “vinegar room” you’d be colonizing yourself, your hair, and especially the soles of your shoes with Acetobacter, which would get transferred all over the house and eventually to the basement. You say your outbuildings are too cold, but, depending on the time of year, especially if you had an electric blanket or heating pad to help, is it possible to keep your vinegar containers in the temperature “sweet spot” for the three to four weeks typically needed for a vinegar fermentation? I’d hate to have you lose the hard-won produce of your old hobby

WINEMAKERMAG.COM APRIL - MAY 2022 17

in an attempt to try out a new one.

If I had to rank your locations, I’d say first choice would be

your stand-alone shed or porch, with the temperature regulated with the addition of an electric blanket or heating pad. You may also want to think about making vinegar when the conditions are the most conducive to it, possibly during the late spring, summer, or early fall. My next choice for location would be your garage, especially if it’s a garage you don’t enter often and especially if it’s not the way you usually enter your house. If you must choose a room inside your house then choose the spot that’s the farthest away from your wine room in the basement, taking into account how much you pass through, enter, or spend time in that space. The more time you spend in “the vinegar area” the more time the Acetobacter will have to glom onto you and get colonized into other parts of your house.

I hope all of this helps you decide where to locate your vinegar project and doesn’t creep you out with visions of aliens taking over your body or zombies invading your cupboards. Just use common sense and be aware, and you should be fine.

QSO GLAD I JUST FOUND YOUR WEBPAGE ON MAKING MELON WINE ( HTTPS://WINEMAKERMAG. COM/ARTICLE/MAKING - MELON - WINE ).

I STARTED FERMENTING CANTALOUPE JUICE A COUPLE DAYS AGO WITH ORGANIC CANE SUGAR DISSOLVED IN COCONUT WATER. FERMENTATION IS ACTIVE NOW. I SEE SOME RED - COLORED SPECKLES IN A LAYER ON TOP OF THE CONTENTS AND WOULD LIKE TO KNOW IF THAT IS TO BE EXPECTED, TO BE STRAINED, OR WHETHER THE WHOLE BATCH SHOULD BE DUMPED. DO YOU HAVE ANY THOUGHTS ON HOW I SHOULD APPROACH THIS? CHEF

JEM JACKSON, NORTH CAROLINA

ABecause cantaloupes have high pH, my guess is that the red speckles you’re seeing in a layer on top of your wine are bacteria colonies and no, they are not to be expected. According to a fruit pH chart I found online from Clemson University, the pH of cantaloupes usually falls in the range of 6.1–6.6. The pH of water is 7.0, and the pH of most table wines made from grapes fall in the 3.3–3.7 range, so are much more acidic than melon juices. Bacteria tend to thrive in a higher pH (lower acidity) environment, which is one part of the reason most wine in the world is made from grapes, whose lower pHs keep spoilage bacteria at bay better (alcohol being the other part of the equation). Wine made from grapes just naturally “happens” better than wines from other fruits, which sometimes need hefty acid additions.

As the article on making melon wines mentions, because melons grow on the ground (as opposed to grapes that are up off the ground on vines), they can pick up a lot of soil-borne microorganisms. Cut into the skin and you’ve just introduced potentially harmful bacteria into the fruit you’re about to press for the juice to make your wine.

Do you need to throw the wine out? Not necessarily, but you might want to be careful if your pH is high and your wine is still in the juice stage. Foodborne bacteria like E. coli and Salmonella can survive on cut watermelons and cantaloupe, and in the raw juice. Luckily, a pH under 4 will inhibit the

growth of just about all food-poisoning bacteria and increasing alcohol levels will also help eliminate them. Dr. Linda Bisson, Professor of Enology when I was a student at UCDavis often told her classes, “No human pathogen can survive in wine.” There’s a reason that drinking wine was safer than drinking water in the Middle Ages and also why wine was used by ancient civilizations to disinfect and clean wounds. However, cut cantaloupe and raw cantaloupe juice can harbor bacteria harmful to humans so do be careful and practice smart food-handling practices when using them in meals, juices, and in winemaking.

Keep an eye on how your wine is progressing because surface-growing bacterial colonies are rarely good news in winemaking. You also could be experiencing a flush of spoilage yeast; the fact that you’ve got colonies growing on the surface also leads me to include aerophilic (oxygen-loving) “film yeast” in the spoilage-organism suspect pool. “Red-colored speckles” doesn’t sound like any common winemaking yeast or bacteria I’m familiar with and it’s very possible they (and other organisms you can’t see) may throw off the flavor and aroma of the finished product. Melon wines are ephemeral products, with the heady aromas we love dissipating very quickly during fermentation. What remains often just seems like the “ghost” of the fruit, even with sound bacteria-free fermentations. This will be even more so if you’ve got any kind of spoilage organisms in there doing their dirty work.

18 APRIL - MAY 2022 WINEMAKER WINE WIZARD

Producing your own vinegar may be easy to do with the addition of a vinegar mother, but winemakers need to take extra precautions to make sure their wines are not negatively impacted from the Acetobacter activity.

To avoid surface-growing film yeast (and also spoilage bacteria) next time, make sure your sanitation procedure is top-notch and get the alcoholic fermentation going right away with a strong strain of yeast so you get a protective layer of carbon dioxide formed on top of the surface. I also don’t recommend using any kind of coconut meat, milk, or water in winemaking as it will contain fat. Especially if your coconut water is the kind sold with small pieces of coconut pulp in it; those little bits will float to the top, forming a perfect little raft for spoilage organisms to grow on!

If your wine goes dry and you still like how it smells and tastes, I recommend sterile filtering it, if possible, with a unit like those made by the popular Buon Vino brand. They can be

spendy so see if your local home winemaking supply store rents filters or if a local home winemaking club has one you can borrow. Filtration (if done with filtration technology that is 0.45 micron sterile or “nominal”) will exclude all yeast and bacteria from your wine, which will help set it up for sound aging. Be sure to adjust the free sulfur dioxide of your wine to around 25–30 ppm (there is a great sulfur dioxide calculator at winemakermag.com/sulfitecalculator to help you do that) so you know your wine will be further protected from oxidation and microbial spoilage during aging. Speaking of which, melon wine lacks the tannins and antioxidants that grape wines naturally have, so it’s recommended to drink them within a year. I wish you luck!

WINEMAKERMAG.COM APRIL - MAY 2022 19

Foodborne bacteria like E.coliand Salmonellacan survive on cut watermelons and cantaloupe, and in the raw juice. The Spring Winemaking Season is almost here! Contact Musto Wine Grape for details on the highest quality and variety of grapes and juices in New England! www.juicegrape.com 877.812.1137 sales@juicegrape.com

VARIETAL FOCUS

BY CHIK BRENNEMAN

MALVASIA BIANCA

A Greek grape that has gotten around

Welcome to the New World perspective on Old World varieties. Seems to be a familiar theme over the years of producing this column. Just about every Old World variety we have covered has a unique story to be told. That is not to say the New World varieties, notably the hybrids, don’t have their own stories, but in many cases, their stories are rooted in how they came to be from Old World varieties. The New World perspective focuses on the science of how any variety came to be, and how the science contradicts the traditional knowledge passed down through generations of viticulturists and winemakers.

When tradition contradicts science I liken that to the old game of “telephone,” where something, fact or fiction, is written on a piece of paper. The paper is then sequestered, and the originator whispers into the ear of the person sitting to one side of them and the story moves around the circle. The last person reveals what they heard and the original statement is revealed, to the laughs and giggles of everyone involved. The similarity here is that traditional documentation is hard to follow and sometimes the science is quite different. We’ll focus on Malvasia Bianca this time around, a variety with many aliases.

HISTORY

Malvasia, by itself, is a generic name for a wide range of white, pink, grey, and black-skinned grapes. Tradition derives its origins from the Greek port of Monemvasia, on the east coast of Peloponnese. From there, the various Malvasia grapes supposedly went out to populate other regions around the Mediterranean. The spelling of Monemvasia morphed to Malfasia, and

then to Malvasia in Italy and Portugal. Malvagia (Spain), Malvasier (Germany), Malmsey (England), Malvasijie (Croatia), and Malvoisie (France) were names also reported by Pierre Galet, the famous French ampelographer, in 2000. However, the science-side shows that all these grapes that contain the name Malvasia are in fact at least 19 genetically distinct varietals, and they do not usually have a common origin. Therefore, when it is reported that something belongs to the Malvasia family, that statement is not correct and I found several references to the “Malvasia family” that, prior to researching this further, were some of my trusted sources for varietal information.

Putting that whole train wreck of a story aside, let’s hone in on the grape Malvasia Bianca. It’s an Old World varietal that is mentioned in literature as early as 1606 near Torino, Italy. It was widely cultivated in Italy’s Piemonte where it is known as Malvasia Bianca di Piemonte until the vineyards there were devastated by powdery mildew towards the end of the 19th century. Today, there is a small amount of it planted in the Italian provinces of Alessandria, Asti, Cuneo, and Torino.

VITICULTURE

Viticulturally, it is a vigorous varietal, with early- to mid-budding, making it somewhat susceptible to late spring frosts. The berries are medium sized and found in large but compact bunches. The varietal is susceptible to powdery mildew but less so to Botrytis.

Beyond Italy, the only other place in the world where it is grown with any significance is California, where the name was shortened to simply Malvasia Bianca. It was brought to the state by immigrants from the Piemonte. The California Department of Food and Agriculture reports that there were 1,384 acres planted in 2009, and that fell

20 APRIL - MAY 2022 WINEMAKER

Photo

of Shutterstock.com

It was widely cultivated in Italy’s Piemonte where it is known as Malvasia Bianca di Piemonte until the vineyards there were devastated by powdery mildew towards the end of the 19th century.

courtesy

MALVASIA BIANCA Yield 5 gallons (19 L)

INGREDIENTS

100 lbs. (45 kg) Malvasia Bianca fruit

Distilled water

10% potassium metabisulfite (KMBS) solution (Weigh 10 grams of KMBS, dissolve into about 75 mL of distilled water. When completely dissolved, make up to 100 mL total with distilled water.)

5 g Lalvin QA23 yeast (Premier Cuvee can also be used as a substitute)

5 g Fermaid K (or equivalent yeast nutrient)

5 g Diammonium phosphate (DAP)

EQUIPMENT

5-gallon (19-L) carboy

6-gallon (23-L) carboy

6-gallon (23-L) plastic bucket

Airlock/stopper

Racking hoses

Equipment cleaning and sanitizing agents (Bio-Clean, Bio-San)

Inert gas (nitrogen, argon, or carbon dioxide)

Refrigerator (~45 °F/7 °C) to cold settle the juice

Ability to maintain a fermentation temperature of 55 °F (13 °C) TIP: Use a 33-gallon (125-L) plastic can as a water bath. Place ice blocks in the water to maintain a relatively constant temperature. This will be your refrigeration system for peak fermentation. If you have other means to keep things cool, of course use that. TIP: You may have a need to keep it warm, in this case wrapping the bucket/carboy with an electric carboy wrap (available at most home winemaking outlets) works well.

Thermometer capable of measuring between 40–110 °F (4–43 °C) in one degree increments

Pipettes with the ability to add in increments of 1 milliliter

Ability to test or have testing performed for sulfur dioxide

STEP BY STEP

1. Crush and press the grapes. Do not delay between crushing and pressing. Move the must directly to the press and press lightly to avoid extended contact with the skins and seeds.

2. Transfer the juice to a 6-gallon (23L) bucket. During the transfer, add 16 milliliters of 10% KMBS solution (This addition is the equivalent of 40 mg/L SO2). Move the juice to the refrigerator.

3. Let the juice settle at least overnight. Layer the headspace with inert gas and keep covered.

4. Measure the Brix.

5. When sufficiently settled, rack the juice off of the solids into the 6-gallon (23-L) carboy.

6. Prepare yeast. Heat about 50 mL distilled water to 108 °F (42 °C). Measure the temperature. Pitch the yeast when the suspension is 104 °F (40 °C). Sprinkle the yeast on the surface and gently mix so that no clumps exist. Let sit for 15 minutes undisturbed. Measure the temperature of the yeast suspension. Measure the temperature of the juice. You do not want to add the yeast to your cool juice if the temperature of the yeast and the must temperature difference exceeds 15 °F (8 °C). To avoid temperature shock, acclimate your yeast by taking about 10 mL of the juice and adding it to the yeast suspension. Wait 15 minutes and measure the temperature again. Do this until you are within the specified temperature range. Do not let the yeast sit in the original water suspension for longer than 20 minutes. When the yeast is ready, add it to the fermenter.

7. Add Fermaid K or equivalent yeast nutrient.

8. Initiate the fermentation at room temperature ~(65–68 °F/18–20 °C) and once fermentation is noticed, (~24 hours) move to a location where the temperature can be maintained at 55 °F (13 °C).

9. Two days after fermentation starts, dissolve the DAP in as little distilled water required to completely go into solution (usually ~ 20 mL). Add the solution directly to the carboy.

10. Normally you would monitor the progress of the fermentation by measuring Brix. One of the biggest problems with making white wine at home is maintaining a clean fermentation. Entering the carboy to measure

the sugar is a prime way to infect the fermentation with undesirable microbes. So at this point, the presence of noticeable fermentation is good enough. If your airlock becomes dirty by foaming over, remove it, clean it, and replace as quickly and cleanly as possible. Sanitize anything that will come in contact with the juice.

11. Leave alone until bubbles in the airlock are about one bubble per minute. Usually about two to three weeks. Measure the Brix every 2–3 days.

12. The wine is considered dry, or nearly dry when the Brix reaches -1.5 Brix or less. Taste the wine, to get a sense of dryness and acidity. Consider a malolactic fermentation (MLF) if acidity is too high.

13. If not opting for an MLF, then add 3 mL of fresh KMBS (10%) solution per gallon (3.8 L) of wine at this point to suppress the bacteria. If opting for MLF, wait until MLF is complete then add 3 mL of fresh KMBS (10%) solution per gallon (3.8 L) of wine. This is the equivalent to ~40 ppm addition. Transfer the wine to the five-gallon (19-L) carboy and lower the temperature to 38–40 °F (3–4 °C).

14. After two weeks, test for pH and SO2. Adjust sulfite as necessary to attain 0.8 ppm molecular SO2. (There is a SO2 calculator available at www. winemakermag.com/sulfitecalculator). Check the SO2 in another two weeks, prior to the next racking and adjust while racking. HINT: Rack to another sanitized five-gallon (19-L) carboy or your bucket. In the case of the latter, clean the original carboy and transfer the wine back to it. This is done at about 4–6 weeks after the first SO2 addition. Once the free SO2 is adjusted, maintain at the target level by monitoring every 3–4 weeks.

15. Consult winemakermag.com for tips on fining and filtration.

16. At about three months you are ready to bottle. Be sure to maintain sanitary conditions while bottling. Once bottled, you’ll need to periodically check your work by opening a bottle to enjoy with friends.

WINEMAKERMAG.COM APRIL - MAY 2022 21

VARIETAL FOCUS

to 988 acres in 2012 where it has pretty much held steady since then. It is mostly grown in the San Joaquin Valley, where it yields approximately four tons to the acre. Given the rich soils of this region, it is certainly not the cash crop growers would hope for, fetching only about $700 per ton ($772 per tonne) in an area that can produce other varieties for more money by weight, and higher tonnage to the acre, like Sauvignon Blanc or Pinot Grigio.

ENOLOGY

What I personally liked about working with Malvasia Bianca when I was the Winery Manager at UC-Davis, was the flavors our climate at the UC-Davis vineyards produced. It is a warmer climate with rich, deep, and loamy soils. We always noted a subtle Muscat character from year-to-year, but depending on the harvest timing it was more floral during the early harvest period, moving to tropical given more time on the vine.

This also translated into somewhat higher viscosity in the resulting wines. My favorite was bringing in the fruit early at lower sugar levels — around 21 °Brix typically. As I reviewed the crush data, it turns out this is the typical Brix for the aforementioned regions. If only I had known that I was onto something! Depending on the variety, harvesting on flavor profile is more important than the actual sugar levels, especially with aromatic white varietals like Malvasia Bianca.

Malvasia Bianca is typically made into a dry style, but there are some off-dry examples as well. My personal favorite is the lower alcohol, fruit-forward version with those hints of Muscat. I am not sure where the Muscat characters come from. Curiously, I looked back though its lineage a few generations and there is no mention of it.

I experimented a little those first few years at UC-Davis making the wine a couple of ways. In one vintage, I minimized the skin contact because the equipment we were using did

22 APRIL - MAY 2022 WINEMAKER

The mostly free-run versions were crisp, aromatic, and very refreshing on the palate.

enough damage to the skins through the crusher/destemmer. I affectionately referred to that piece of equipment as the “master of maceration.” As a result, I would only process what I could press within a very short amount of time and collecting mostly free-run juice. I took the remaining must, still quite wet, and let that sit on the skins for several hours more. Then pressed it fairly dry. I took this advice from one of our German students who told me that up to 24 hours of skin contact is acceptable for aromatic whites, since the aroma compounds are located in the skins. The resulting wines were quite different, with the latter having significantly more bitterness and astringency than the former. In hindsight, perhaps some use of enzyme to reduce the skin contact time would have been helpful, but my experience with enzymes is somewhat limited.

The mostly free-run versions were crisp, aromatic, and very refreshing on the palate. They were well-balanced with respect to acidity and flavors. One of the challenges with making wine in California is the natural tendency for the grape berry acidity to decrease during maturation. This acidity reduction can be minimized with an earlier harvest, albeit once those flavors you desire have been achieved. There is generally the subsequent need to supplement the acidity prior to fermentation. This is a challenge to many home winemakers without the proper testing equipment. For those that can’t test, sending a sample to a commercial lab will lead you to a plethora of pre-fermentation steps to properly adjust your juice and must for acidity and nutritional status. This is money well spent.

In order to preserve the acidity that I work hard to start out with I monitor my primary fermentation very closely, and when the Brix goes negative for a couple of days in a row I add sulfur dioxide and chill the wine to inhibit malolactic bacteria. The amount of sulfur dioxide depends on the pH. Refer to winemakermag.com/sulfitecalculator for the optimum amount. Ideally, you want to achieve 0.8 ppm molecular, which will assure a cessation of the malolactic fermentation, but you have to be careful if your wine pH is too high. In this case, 0.5 ppm and keeping

your temperatures low (<45 °F/7 °C) should be sufficient. Once the wine is sufficiently stable, taste the wine. If the acidity is too high by taste, I will consider backsweetening to the off-dry style. Backsweetening can be achieved by setting aside and freezing some of your juice when you pressed it or with the use of white juice concentrates available at your local winemaking supply stores.

The scientific side of Malvasia is

not intended to be a buzz-kill about the traditional lore of the “Malvasia family.” But what it boils down to is your reference source material should be sound and based on fact. With such a long historical account of all the Malvasia-named grape varietals there is bound to be confusion. In this case, the scientists have set it straight. That said, when traveling the Old World, I still love to hear the traditionalists tell their stories too. Enjoy!

WINEMAKERMAG.COM APRIL - MAY 2022 23

A N D M A L O L A C T I C C U L T U R E S P I O N E E R I N G P R E M I U M Y E A S T

FOR WINEMAKING

Exploring the options and functions in the winery

by Bob Peak

by Bob Peak

n earning a chemistry degree and working in laboratories, I thought of “inert gases” as being the same as the “noble gases” of the periodic table: Helium, neon, argon, krypton, xenon, and radon. Once I started making wine, though, and got into some more advanced topics, I found winemakers consider the inert gases to include argon, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide (carbon dioxide is not really inert — more on that later.) One more gas — a blend of two of these— comes up in winemaking as well. That is “beer gas,” a blend of nitrogen and carbon dioxide. As the name suggests, it is most commonly used by brewers (usually for dispensing beers “on nitro”) but it finds use in wineries as well. The gases used in winemaking serve mostly to prevent or minimize oxidation of wine. Even though not fully inert, I’ll call them that in this article since that is common usage in winemaking.

For some winemaking applications, one or another of these inert gases may be clearly superior. For others, you may be able to make substitutions. After we consider the characteristics of the four gases, we will review their principal uses. In roughly the order they might come up during a winemaking cycle, we will look at cold soaking, extended maceration, container purging, wine transfer, sparging, bottling, carbonating, and dispensing.

24 APRIL - MAY 2022 WINEMAKER

WINEMAKERMAG.COM APRIL - MAY 2022 25

Photo by Charles A. Parker/Images Plus

GET TO KNOW YOUR GASES ARGON

Argon (Ar) is the lone noble gas of the periodic table used in winemaking. It is resistant to all chemical reactions and is denser than atmospheric air, giving it an advantage in filling vessels or displacing a layer of air. It has a density of about 1.78 g/L, compared with air at about 1.29 g/L. (The density difference is also why noble gas helium is of no interest to winemakers. At less than 0.2 g/L, it would dissipate immediately.) Argon is a pure element in monatomic form: Individual Ar atoms make up the gas.

To use argon in your winery, you will need a compressed gas cylinder, a pressure regulator, and various hoses and fittings. A common size for home use is a 19-cubic foot (538-L) cylinder, named for the volume of gas upon release at atmospheric pressure. The cylinder is about 14 inches (36 cm) tall and 5.25 inches (13.3 cm) diameter. The gas is compressed to about 2,000 psi (pounds per square inch) or 13.8 megapascal. Argon, nitrogen, and beer gas use an inert gas regulator with a connection designated CGA #580 by the Compressed Gas Association. Such a regulator can be used interchangeably on those three gases. Fermentation supply stores and welding gas outlets sell tanks and fittings. Argon costs about $250 for a full 19cu. ft. cylinder and a regulator is about $90. The cylinder can be refilled or exchanged at a lower cost.

NITROGEN

Nitrogen (N2), the diatomic gaseous form of nitrogen, is what we are considering here. As a winemaking gas, it is unreactive and works well in many “inert” applications. As an element, home winemakers know nitrogen as a component in compounds like DAP (diammonium phosphate) and amino acids that do react with other wine components. For inert gas use, molecular nitrogen can be used at a lower cost for most of the same purposes as argon. The gas in contact with juice or wine does not spontaneously react with any other constituents. One drawback for nitrogen in blanketing or inerting operations is a density

slightly lower than air: 1.25 g/L for nitrogen vs. the 1.29 g/L for air. It mixes easily with air and dissipates quickly.

Distributed in the same cylinders as argon, it uses the same regulator. It has a lower cost than argon with a 19cu. ft. (538-L) cylinder selling for about $235, but may add more cost per use because its density makes it a less effective blanket gas. Cylinder refills or exchanges are less expensive as well.

CARBON DIOXIDE

While it is used for many of the same oxygen displacement purposes as argon and nitrogen, carbon dioxide (CO2) is not inert. In contact with water or wine, some molecules combine with water according to the reaction:

CO2 + H2O H2CO3

From there, a fraction of the resulting compound dissociates like this:

H2CO3 HCO3- + H+

Seeing that H+ lets us know that hydrogen ions are present: An acid-forming reaction. In solution, carbon dioxide is sometimes called carbonic acid. Unreacted molecular carbon dioxide remains dissolved as well. Rising temperature or agitation causes gas to leave solution. Wines with noticeable carbon dioxide are considered spritzy, petillant, or sparkling. If you do not want spritzy wine, you must be careful in your use of carbon dioxide as your “inert gas.” It has one clear advantage in its density of 1.98 g/L, making it the heaviest of the winemaking gases. CO2 condenses to a liquid when pressurized in a cylinder. As a result, cylinders are sold by weight rather than nominal volume. Most common for home use is a 5-lb. (2.3kg) cylinder that is about the same size as the 19-cu. ft. cylinders argon and nitrogen come in. A full 5-lb. (2.3-kg) cylinder costs about $125 and will release about 44 cu. ft. (1,250 L) at atmospheric pressure. A refill or exchange costs about $40. Because the contents are in liquid form, a CO2 cylinder must be kept upright in use, presenting only headspace gas to the regulator. If liq-

uid CO2 were to enter the regulator, its sudden evaporation would damage the equipment. CO2 requires a specific CO2 regulator that cannot be used with the other gases mentioned.

BEER GAS

Used primarily for dispensing draft beer, this blend of nitrogen and carbon dioxide is most commonly found in a ratio of 75% nitrogen and 25% CO2 With that blend, beers like Guinness Stout and Boddington’s Pub Ale on draft maintain the cascading bubbles and creamy mouthfeel that drinkers expect from “nitro” beers. For winemaking, beer gas is used for the same purposes as the other inert gases. In contact with wine, some carbon dioxide will dissolve, but not usually enough to carbonate the wine or make it “sparkling.” Blends with a higher carbon dioxide ratio are available, but offer no particular advantage to the home winemaker. Because nitrogen does not condense to a liquid under pressure, the tank and regulator for beer gas are the same high-pressure equipment as for nitrogen or argon. A full 19-cu. ft. (538-L) cylinder costs about $230, offering a small price advantage over argon or nitrogen.

WHAT ELSE YOU’LL NEED

Once you have purchased a full cylinder and appropriate regulator of your chosen gas, you will need some other hardware. Most regulators have an on-off valve already fitted. Have one installed if yours does not. You will also need to buy some beverage-grade tubing that fits your regulator. Between five and 10 feet (1.5 to 3 m) works well for most, but take into account your winery layout. If you intend to use your gas for sparging wine (more on this later), efficiency will be improved if you buy a fritted stainless steel sparging stone. A hose-end spring loaded squeeze valve may be convenient. You may add other fixtures like quick disconnects, inline valves, or a flow meter.