Cru International invites you discover two highly acclaimed international wine styles!

Bourbon Barrel Style brings to life full-bodied whiskey flavours all the way from Kentucky and French Gamay Style highlights the unique tastes of grapes inspired by one of the finest grape-growing regions of France.

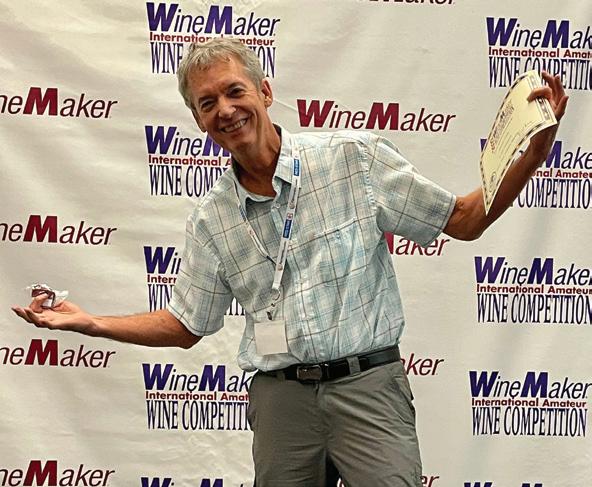

WineMaker readers and Publisher Brad Ring recently spent a week exploring beautiful wine regions in Chile and Argentina during harvest. We recap and share pictures from the adventure.

28

AWARD - WINNING FRUIT WINES

We share recipes and advice for four gold medal-winning fruit wines made by top amateur winemakers. Instead of just waiting for the grape harvest to roll around this fall, try your hand at one of these unique fruit wine recipes.

by Ryley Hougland

by Ryley Hougland

David Cohen’s dessert wines made from Finnish fruits have received top honors in competitions around the globe. Here, he shares his advice for home winemakers with access to fresh fruit and a sweet tooth to make their own post-dinner sippers.

by David CohenWhile it sometimes gets a bad rap because too much oxygen can destroy a wine, oxygen is also very important to the winemaking process. Learn the six ways to use oxygen to your wine’s benefit.

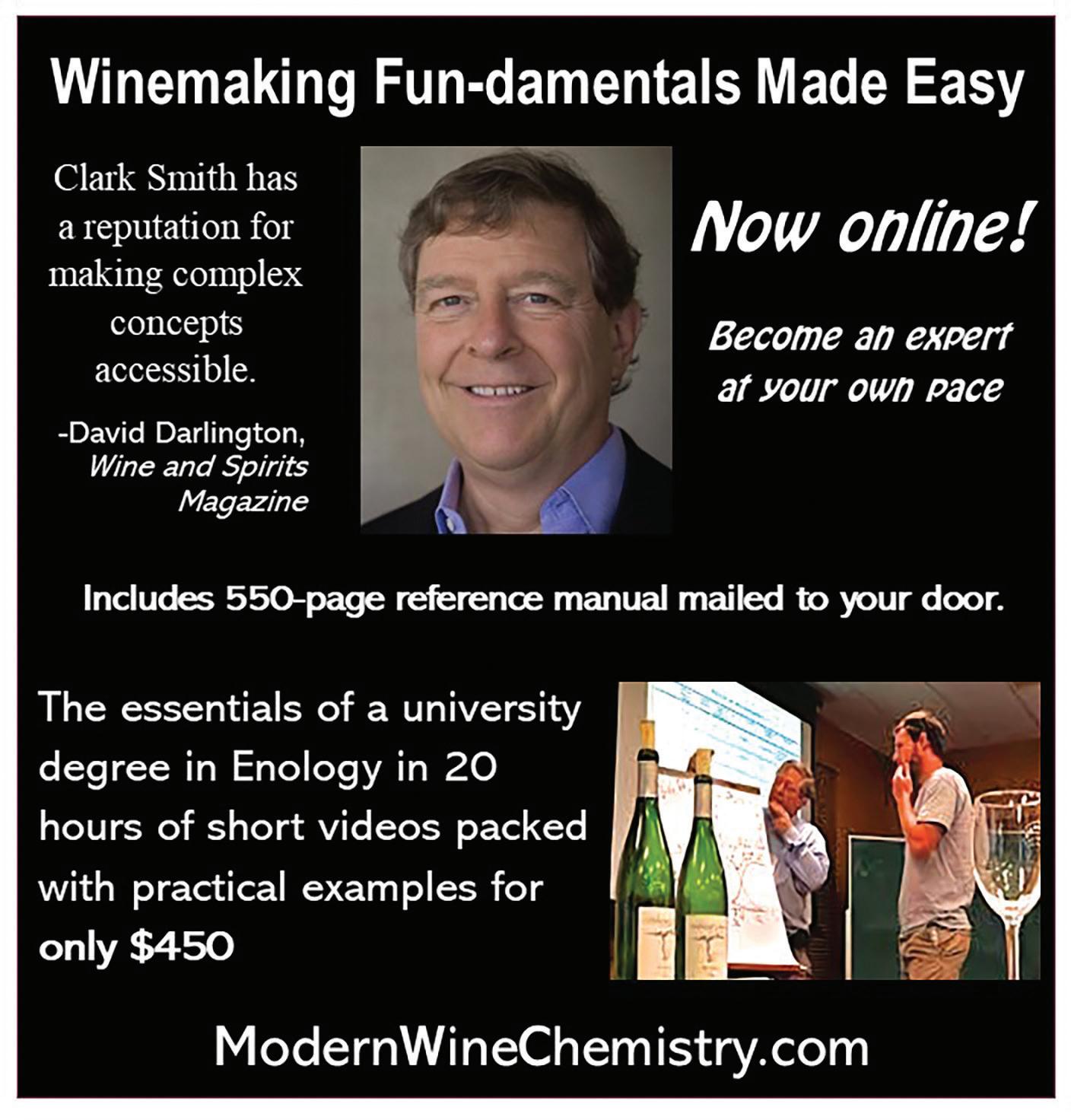

by Clark Smith

by Clark Smith

8 MAIL

A reader shares his pleasure for a recent story we ran on making wines from the often overlooked hybrid grapes, and another looks for help bottling large quantities of sparkling wine.

10 CELLAR DWELLERS

As the temperatures climb during the summer months, trees, bushes, and other perennials teeming with berries are aplenty. Get some tips on making berry wines, learn about the much beloved Marquette hybrid grape, and get the latest news, products, and upcoming events.

14 TIPS FROM THE PROS

Three pro winemakers share how they use pectic enzymes to their advantage to maximize yields, increase color and flavor extraction, and make filtration easier.

16 WINE WIZARD

The term “sacrificial tannins” is something that gets casually tossed into the winemaking lexicon by those who have been in the trade for a while . . . but what does it really mean? Get an explanation along with tips for rehydrating dry yeast and techniques to properly stabilize a fortified wine.

19 VARIETAL FOCUS

With its home along the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, this white grape is starting to find its way to the U.S. for good reason. Learn about the history, viticultural tips, and winemaking styles of Vermentino grapes.

48 TECHNIQUES

Many homebrewers of beer are unknowingly very familiar with the Charmat method to carbonate wine. If you are unfamiliar with this easy, albeit more equipment-heavy, process to produce bubbly wines, Bob Peak explains the technique.

51 BACKYARD VINES

Not every location needs to irrigate their vines every year, but for those that do, advanced planning is key. Here is a walk through the factors that need to be considered when establishing a vineyard and irrigation needs.

56 DRY FINISH

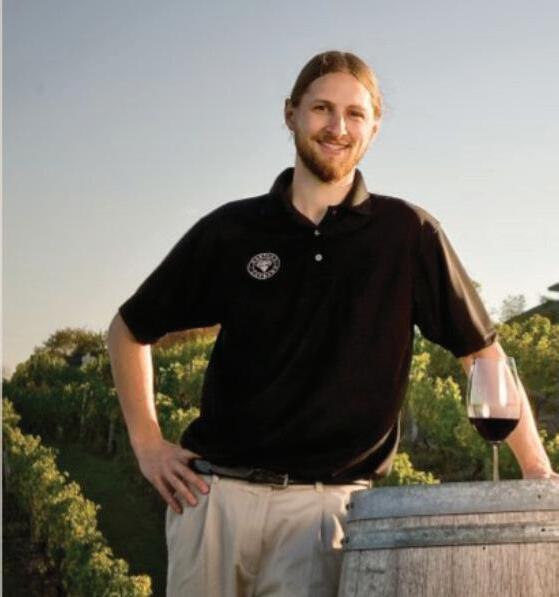

When a home winemaker moves to Finland and finds that the grape winemaking he has come to know and love isn’t feasible there, he turns to the next best thing . . . berry winemaking. Now he is making waves on a global scale.

March 18 – 26, 2024

Join WineMaker Magazine in South Africa next March 18 - 26, 2024 to combine wine with a safari adventure in one epic vacation! We’ll tour the most famous wine regions of South Africa including Stellenbosch, Franschoek, Paarl, and the Cape. We’ll visit both small and large wineries meeting their winemakers and tasting the local Pinotage and many other great wines during the excitement of their Southern Hemisphere grape harvest season. Then we’ll head to Kruger National Park to seek out lions, leopards, elephants, rhinos, and cheetahs from an open Land Rover with a ranger and spotter on a thrilling, once-in-a-lifetime safari.

For more details visit: winemakermag.com/trip

EDITOR

Dawson Raspuzzi

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Dave Green

EDITORIAL INTERN

Ryley Hougland

DESIGN

Open Look

TECHNICAL EDITOR

Bob Peak

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Dwayne Bershaw, Chik Brenneman, Alison Crowe, Wes Hagen,

Maureen Macdonald, Bob Peak, Phil Plummer, Dominick Profaci, Clark Smith

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHER

Charles A. Parker

EDITORIAL REVIEW BOARD

Steve Bader Bader Beer and Wine Supply

Chik Brenneman Baker Family Wines

John Buechsenstein Wine Education & Consultation

Mark Chandler Chandler & Company

Wine Consultancy

Kevin Donato Cultured Solutions

Pat Henderson About Wine Consulting

Ed Kraus EC Kraus

Maureen Macdonald Hawk Ridge Winery

Christina Musto-Quick Musto Wine

Grape Co.

Phil Plummer Montezuma Winery

Gene Spaziani American Wine Society

Jef Stebben Stebben Wine Co.

Gail Tufford Global Vintners Inc.

Anne Whyte Vermont Homebrew Supply

EDITORIAL & ADVERTISING OFFICE

WineMaker

5515 Main Street

Manchester Center, VT 05255

Tel: (802) 362-3981 Fax: (802) 362-2377

Email: wm@winemakermag.com

ADVERTISING CONTACT:

Kiev Rattee (kiev@winemakermag.com)

EDITORIAL CONTACT:

Dawson Raspuzzi (dawson@winemakermag.com)

SUBSCRIPTIONS ONLY

WineMaker

P.O. Box 469118

Escondido, CA 92046

Tel: (800) 900-7594

M-F 8:30-5:00 PST

E-mail: winemaker@pcspublink.com

Fax: (760) 738-4805

Special Subscription Offer

6 issues for $29.99

Cover Photo: Charles A. Parker/Images Plus

As the temperatures rise, I like to keep a Gamay rosé on hand for guests or myself to enjoy while sitting in an Adirondack chair in the backyard. The ideal examples are dry with balanced acidity and give nuanced aromas of strawberry, rhubarb, and cranberry –perfect for summer sipping. Plus, they pair well when we have a strawberry spinach salad or grill seafood.

I like bright, aromatic whites and rosé, chilled in a tumbler with a picnic. Try a Sauvignon Republic Sauvignon Blanc from Marlborough, NZ, or any Provence rosé, especially designated ‘Tavel.’

As I think about summer being right around the corner, I am ready to bottle what I feel is by far the best summer sipper. Rosé has grown so much in popularity over the past few years; for good reason. It is easy drinking, packed with summer berry fruit flavors, and refreshing. It pairs beautifully with BBQ and pretty much anything with a bit of spice. My favorite rosé is made from a direct crush and press of the Marquette grapes I grow. It has a nice acidity to cleanse the palate of whatever you may be eating and fills your mouth with field fruits like strawberry and raspberry. Definitely looking forward to summer. Salute!

PUBLISHER

QBrad Ring

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER & ADVERTISING DIRECTOR

Kiev Rattee

ADVERTISING SALES COORDINATOR

Dave Green

EVENTS MANAGER

Jannell Kristiansen

BOOKKEEPER

Faith Alberti

SUBSCRIPTION CUSTOMER SERVICE MANAGER

Anita Draper

If you take as much care selecting your ingredients and crafting your country wine as grape winemakers do with theirs, you can make a wine that can hold its head high among the Cabs and Chardonnays of this world. Get advice from one of the masters of the trade.

https://winemakermag.com/article/ 5-10-tips-for-country-winemaking

MEMBERS ONLY

Perfect for after-dinner treats, dessert wines are some of the most complex wines in the world. Get tips for making your own icewine, Sherry-style, and Port-style wines at home. https://winemakermag. com/article/dessert-wines

All contents of WineMaker are Copyright © 2023 by Battenkill Communications, unless otherwise noted. WineMaker is a registered trademark owned by Battenkill Communications, a Vermont corporation. Unsolicited manuscripts will not be returned, and no responsibility can be assumed for such material. All “Letters to the Editor” should be sent to the editor at the Vermont office address. All rights in letters sent to WineMaker will be treated as unconditionally assigned for publication and copyright purposes and subject to WineMaker’s unrestricted right to edit. Although all reasonable attempts are made to ensure accuracy, the publisher does not assume any liability for errors or omissions anywhere in the publication. All rights reserved. Reproduction in part or in whole without written permission is strictly prohibited. Printed in the United States of America. Volume 26, Number 3: June-July 2023.

Dom Pérignon is a symbol of luxury engrained in pop culture. But beyond the hype, Dom Pérignon is also recognized by serious wine critics as a consistently exceptional example of the top tier of Champagnes. Get pointers from its Chef de Cave. https://winemakermag.com/ technique/622-secrets-of-dom-perignon

MEMBERS ONLY

Country fruit wines can be quite difficult to achieve the desired color, aroma, and clarity levels. Here is a look at the various enzymes typically used in grape winemaking that can also be used in fruit wines. https:// winemakermag.com/technique/1761enzymes-in-country-wines

MEMBERS ONLY

* For full access to members’ only content and hundreds of pages of winemaking articles, techniques and troubleshooting, sign up for a 14-day free trial membership at winemakermag.com

I commend Zac Brown for his fine article “Red Hybrid Grape Winemaking” in the April-May 2023 WineMaker magazine. And I thank you folks at WineMaker for devoting the space to highlight red hybrid grape winemaking. Making wine from hybrids grown here in Wisconsin can be challenging for all the reasons Zac points out, but when the wine turns out, and maybe even is recognized with an award or ribbon, it is especially satisfying to know that you have succeeded in an area where others have not traveled. Please keep these articles coming. Maybe the next one could be white hybrid grape winemaking?

Rod Kazmerzak • Sun Prairie, WisconsinWe always love hearing from readers who benefit from the stories we publish. Winemakers who live in a climate where they must rely on hybrid grapes to make wine may be a smaller audience, but they are just as important to us. The struggle that comes with making wine from hybrids can in part be due to the grapes often having numbers that aren’t as ideal as their Vitis vinifera cousins, but also because there is not as much literature available about making fine wines from these grapes. We’ll keep doing our part to help hybrid winemaking hobbyists as long as you and others who live in climates best suited for hybrid grapes keep trying their hand at turning them into wine. As a magazine based in Vermont, all of us at WineMaker understand the challenges when making wine with hybrids, but we’ve also tasted many of the success stories.

I am hoping you can provide me with a lead to where I might find bottling equipment for sparkling wine. We operate a fermenton-premises winemaking shop and our customers are looking to have their wine sparkled. We found a counter-pressure bottler that you connect to your Corney keg and CO2 bottle, but the unit isn’t very friendly to your hands as you attempt to hold it on the bottle while it is under pressure. Please let me know if you can recommend a company who may carry such a device. My hands will be eternally grateful.

Stuart Ray, Vintner’s Cellar Cochrane • Cochrane, AlbertaWe’d recommend getting in touch with XpressFill in California. We see this unit after a quick search on their site: https://www.xpressfill.com/ carbonated-beverage-counter-pressure-bottle-filler.shtml but they may have other solutions as well.

All the best bottling sparkling for your customers in an easier way!

David Cohen began his winemaking hobby making kit wines and reading WineMaker magazine 20 years ago while living in Massachusetts. He began to experiment making fruit wines from local berries after moving to Finland for work. After a couple of years of making wines that kept turning out better than he previously believed possible, he and his wife, Paola, founded Ainoa Winery. David makes the only fruit wines in the world awarded gold medals from the Oenologues de France — at tastings in Paris, Champagne, Provence, and Bordeaux.

Learn more about David’s winemaking journey in the “Dry Finish” column on page 56. And beginning on page 34, David also shares advice on making worldclass dessert fruit wines at home.

Clark Smith is one of California’s most widely respected winemakers. In addition to his own WineSmith wines, he has built many successful brands and consults for hundreds of wineries on five continents. His popular course, Fun-damentals of Winemaking Made Easy, has graduated over 4,500 winemakers to rave reviews. Winemaker, inventor, author, musician, and teacher, Smith was named the Innovator of the Year at the 2016 Innovation + Quality conference (presented by Wine Business Monthly), was named among Wine Business Monthly’s 2018 list of the 48 Most Influential People. His book Postmodern Winemaking was Wine and Spirits magazine’s 2013 Book of the Year.

Beginning on page 40, Clark counters the misconception that oxygen is the enemy of wine and details six beneficial ways to utilize oxygen to the advantage of your wine in the winemaking process

Alison Crowe is Vice President, Winemaking at Napa-based Plata Wine Partners, a 500,000+ case wine company servicing retailers, restaurant groups, and multiple wine brands. Alison holds a BS in Fermentation Science, a BA in Spanish, and an MBA from UC-Davis, is the author of The Winemaker’s Answer Book and has been writing the “Wine Wizard” column in WineMaker since its inception in 1998. She is Co-Chair of the Carneros Wine Alliance and serves on the Program Committee for the Unified Wine & Grape Symposium, the largest wine industry trade show in the Western Hemisphere. Though she makes wine on a commercial scale, Alison loves nothing more than helping the hobby- and micro-vintners achieve success and satisfaction with projects at home. She lives in Napa, California, with her husband and two young sons.

In this issue’s “Wine Wizard” column on page 16, Alison defines “sacrificial tannins” and when adding them is necessary, rehydrating yeast, and whether potassium sorbate should be added to a fruit Port-style wine.

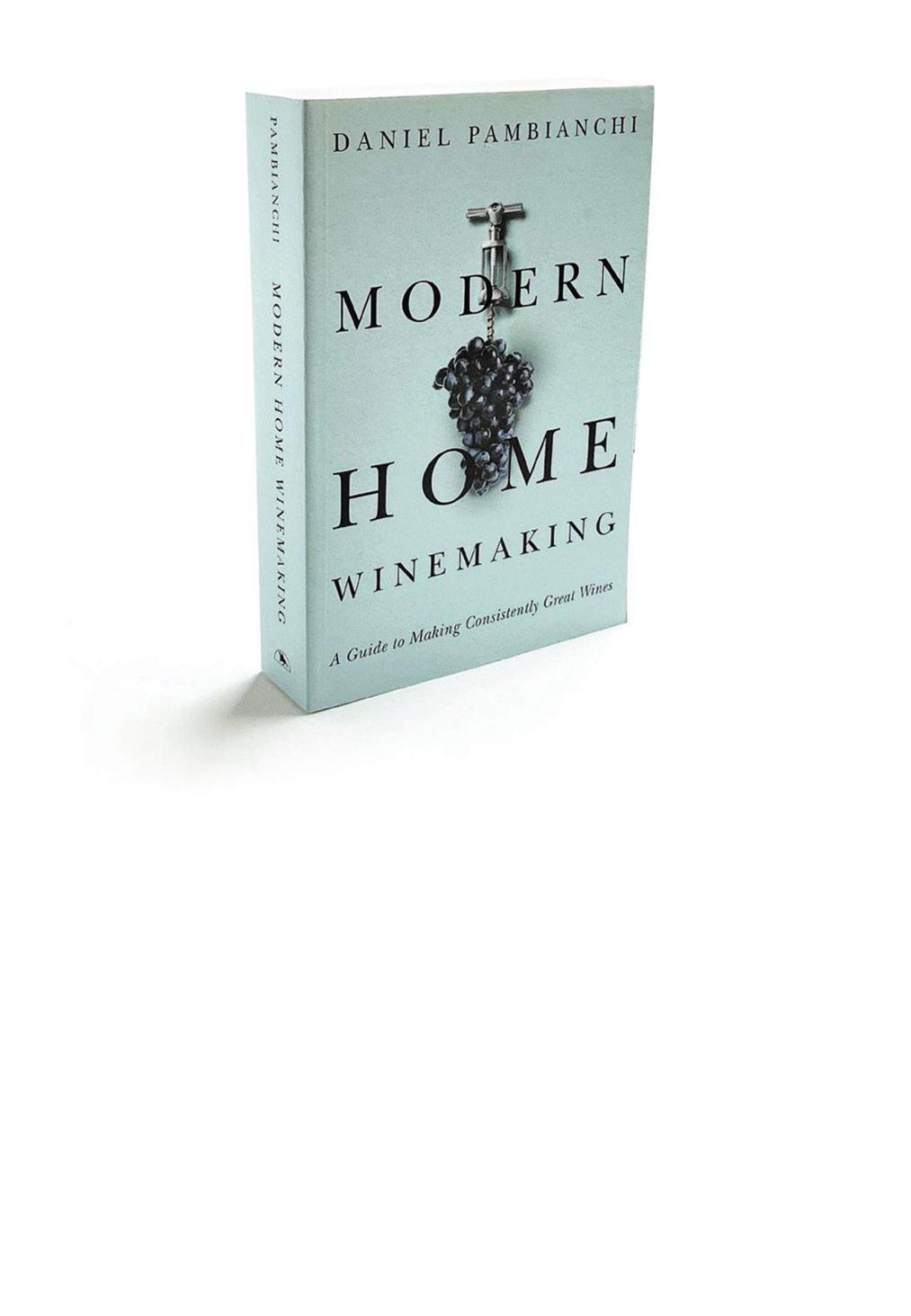

“This book contains techniques and methods for the home winemaker but would also be helpful to winemakers of any experience level from beginner to advanced commercial winemakers. It is thorough, complete, incredibly well researched, and contains the latest research on wine testing and analytical methods…this book leaves nothing out.”

– drew horton , Enology Specialist, University of Minnesota Grape Breeding & Enology Project

6x9” | illustrated | 614 pages

ISBN: 978-1-55065-563-6 $29.95 (trade paper)

ISBN: 978-1-55065-593-3 $59.95 (cloth)

Distributed by Independent Publishers Group

Milwaukee’s

PRO Mini

allow you to use your time more e ectively when performing titrations. The Titrators run a titration until an end-point is measured and provide the operator with a digital read-out! No more color change guessing!

Ask oenophiles around the world where wine grapes originally came from and most will cite the south Caucasus Mountains of Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. But new research has shown that Georgia may not be the only region to domesticate the wild Vitis vinifera sylvestris. A second location 600+ miles (~1,000 km) away, near modern Israel, Lebanon, and Jordan, looks to have produced similar results domesticating the wild grape vine. Not only that, but the grapes domesticated in this region seem to be the ones that proliferated both east towards the Asian continent and west around the Mediterranean.

Using gene sequencing technology, it seems that the domestication process in the south Caucasus region near the Asian/European border did not spread far and wide like earlier thought. While the more eastern domestication process seemingly was originally intended for table grapes, it was only later used for wine production after cross breeding occurred. The study also pushed the date of both domestication dates much earlier, now thought to have happened 11,000 years ago. There are still a lot of questions that remain such as if there was some minor domestication of wild grapes prior to the full split to Vitis vinifera vinifera that science is blind to at this point. We’re sure there will be more research into this topic, but be sure to check out:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adg6617

Released by the folks at GOfermentor, GOpump is intended for pumping wine or similar fluids (it is not designed to be used as a must pump). It can be used in pump mode where the delivery rate is automatically controlled at the user-set flowrate or in batch mode where a preset volume is delivered at a user-set flowrate. And finally there is a remote mode where the pump can be controlled by external device or app (Bluetooth or WiFi). A built-in totalizer based on magnetic flux sensing (no moving parts) provides an accurate estimate of total wine transferred. Controllable flow rate allows gentle or rapid transfer of wine. Flow rate is from 1 to 10 liters per minute (0.26 to 2.6 gallons per minute). It also has automatic shutdown on empty detection. http://gofermentor.com/gopump/

Home

in

on July 16 from 4–6:30 p.m. at the

There is no charge to serve your wines, but there is a $25 fee per wine in order to get them judged. Or simply come as a guest and taste others’ wines. In its 40th year, this event fundraises for the Mt. Veeder Fire Safe Council’s community outreach for wildfire safety and prevention. Serve, sip, and bid for world-class wines and gift packages, all in the name of supporting wildfire safety. More information can be found at: www.homewinemakersclassic.com

Grape & Non-Grape

Vintner’s Best Mango GOLD

SILVER

Winexpert Island Mist Black Cherry

Winexpert Island Mist Coconut

Yuzu

BRONZE

Vintner’s Best Cherry

Winexpert Island Mist Black

Raspberry Merlot

Winexpert Island Mist Blood

Orange Sangria

Winexpert Island Mist Green Apple

Riesling

Winexpert Island Mist Raspberry

Peach Sangria

Here is a list of medal-winning kits for the Grape & Non-Grape Table Wine Blend and Berry Fruit categories chosen by a blind-tasting judging panel at the 2022 WineMaker International Amateur Wine Competition in West Dover, Vermont: Our Red Star range is evolving. New names, the same tradition.

Cranberry Pinot Gris

Winexpert Island Mist White

Winexpert Island Mist Wildberry

Shiraz

Table Wine Blend Berry Fruit

GOLD

RJS Craft Winemaking Acai Raspberry

Winexpert Island Mist Blueberry

Pinot Noir

BRONZE

Vintner’s Best Cranberry

Winexpert Island Mist White

Cranberry

First introduced by the University of Minnesota, Marquette is a cold-hardy red wine grape that can withstand winter temperatures as low as -30 °F (-34 °C). Its parentage is a cross between two other hybrid grapes and is best known for producing dry, medium-bodied reds with the capacity to get Brix up to 22–26. According to the University of Minnesota, the suggested titratable acidity at harvest is roughly 11–12 g/L and a pH between 2.9–3.3. The wines it can produce are well known to be able to stand up to an extended time in barrel.

In the vineyard, Marquette has a reputation for its disease resistance with moderate resistance to black rot, Botrytis bunch rot, and both powdery and downy mildews. But it does have

some susceptibility to phylloxera. It is an early budding vine, which makes it vulnerable to late frosts. It is a later ripening variety, sometimes hanging on the vines until late September or early October. Marquette is a vigorous grower, making it well suited for soils with lower nutrient levels. High-nutrient soils will require greater spacing in order to allow the vines to spread, and an aggressive canopy management may be needed in that circumstance.

Because of the quality of wine it can produce, Ontario, Canada, added Marquette to its list of approved grapes under its VQA label in 2019. For those living in colder climates and looking to grow wine grapes, Marquette should be near the top of your list of varieties to investigate.

What defines a berry is akin to what constitutes a vegetable. There are two definitions, the botanical one and the traditional classifications. Take, for example, raspberries, blackberries, and strawberries; three iconic berry fruits grown in temperate climates . . . and it turns out none of them are truly berry fruits. But winemakers don’t really care about botanical definitions, much like tomatoes are still called vegetables by many in the culinary world. So for the sake of this column, many soft-skinned, pit-less fruits like those listed earlier still fall under the umbrella of berries.

Berry wines are commonly made in areas where Vitis vinifera and other wine grapes struggle to thrive. Even many grape growing regions also offer an array of fruits available for winemaking purposes. Fruits like currants, salmonberries, juneberries, gooseberries, bearberries, chokecherries, and cranberries . . . there are an abundance of berry fruits growing around the world that can be processed into wine. Berry wines are also a great option for home winemakers living where grapes are prevalent because they often ripen outside of the grape harvest timeframe; giving winemakers another season to enjoy their hobby.

Not everyone can harvest and process the amount of fruit required to produce a mid-sized, say a 5-gallon (19-L), batch of wine. There are plenty of alternatives including frozen fruit, purees, juices, and concentrates that are available for purchase if a larger volume is desired. Supplementing two or more of these options may actually be a good solution as they can provide different fruit character. Also, blending with grape wine may be a great solution when certain characteristics in a grape

wine need a boost. Blueberries in a Pinot Noir or strawberries in a Grenache rosé can prove to be fun, highly drinkable porch sippers.

A key for almost any of the traditional berry fruit wines is breaking down the cell walls of the fruit. Freezing the fruit prior to maceration is one common technique that many berry winemakers employ. The addition of pectic enzymes can also be helpful. Pectins are in the sugar family (polysaccharides) and can cause a haze in the final wine. Adding an enzyme meant to chop these polysaccharides can actually have a two-fold solution: They can break down one of the key problematic haze-causing compounds and can also increase your yield. If you’re using fresh-picked or frozen fruit, a little pectic enzyme can go a long way in crafting a stable wine.

It’s impossible to talk about berry wine production and not also discuss the need for chaptalization and for a possible acidification or deacidification as well. If you stick with typical grape wine parameters then producing a stable berry fruit wine is attainable. Starting with a sugar addition to chaptalize up to 22 °Brix is safest. Most recipes you will find call for between 2.5–5 lbs. of berry fruit per gallon (0.3–0.6 kg/L) of finished wine. The more fruit means more fruit character, less water needed, and more acidity. Starting sugar concentrations and acid levels depend upon the fruit type and variety, its growing season, and harvest date.

Targeting a pH level between 3.3–3.6 is a good goal. While there are a few exceptions, citric acid is typically the largest organic acid component in berry fruits. Winemakers should note citric acid, like malic acid, is susceptible to metabolic degradation. Also, high acidity can be counterbalanced with backsweetening.

Strawberry

A key component of strawberry wine is coaxing the flavor from the berries while retaining that character and color. The pigments that color strawberries are not that robust and prone to oxidative degradation. Adding some crushed red grapes or red grape concentrate can provide a more stable rosé hue. Strawberry wines are often crafted with a sweet character, but they don’t need to be, and actually can be quite delicious when dry. Look for fruit that has received a great deal of sun exposure, allowing them to gain that vibrant red hue from anthocyanins.

In standard greenhouse-grown strawberries you may find sugar at 9 °Brix, which should provide a great base for a strawberry wine. With the TA at 9 g/L or higher, water dilutions may require an acid addition if pH started high. Sometimes a little strawberry flavoring extract can really make the wine pop.

One of the great aspects of blueberries is the polyphenolic load found in their skins that are close to typical wine grapes. These compounds will help provide color and structure to blueberry wine. Blueberries are fairly high in sugar with ripe, high-quality fruit coming in at 14–18 °Brix. Some red grape concentrate can be added to enhance the fruitiness and bring Brix up to a more common wine range.

Raspberries can come in both red and black form and both can be utilized for winemaking. Freezing the berries prior to working with them is a great help to pulverize each berry. Expect them to ripen to 8–13 °Brix with a TA between 10–20 g/L. Also note that pressing raspberries can be a challenge due to their mushy character at this point. Go slow or add rice hulls to separate the juice from pulp.

Pectic enzymes can be a significant help to maximize yields, increase color and flavor extraction, and make filtration easier by breaking down pectin. These benefits are especially useful in making wines from fruits higher in pectin. Three pros share advice on when and why they turn to these enzymes to help in the winery.

Pectic enzymes have several uses in winemaking. Typically, they are utilized to break something down into smaller parts and/ or extract a desired compound. There are multiple formulations for different applications, so the appropriate product should be chosen based on the use. They can be used for settling of juice to increase yields at pressing or racking by breaking down the pectins so they compact, allowing the juice to be more easily separated from the pulp. They can also be used before pressing white grapes or during red fermentation to extract color and/or flavors by breaking the bond to things like polysaccharides. They can also be used to break down pectin or other filter plugging compounds so filtration can go smoother.

Care should be used in selecting the appropriate enzyme for the application as some enzymes are too aggressive to use on whole fruit and will turn the whole batch into mush that will be impossible to press or separate from the solids.

Wine made from fruit other than grapes is one of the best places to use pectic enzymes. Many fruits have more pectin in them than vinifera grapes, though hybrids tend to have more pectin than other wine grapes. That said, underripe grape varieties of all types tend to be higher in pectin as well. In the instance of fruits other than grapes, wine filtration can be near impossible without the use of enzymes in the worst cases, and even in the best cases you will get more wine through a set of filter pads with their use.

Enzymes should be added based on the recommendations of the manufac-

turer and application. That said, there are some things to be aware of when adding pectic enzymes. The first is temperature: The colder the wine or juice, the slower they will work.

Second is inhibitors: Additives such as sulfur, bentonite, and tannins can inhibit or inactivate enzymatic activity. All these things should be added separately and fully homogenized prior to the next one. Sulfur will inhibit at high rates so it will need to be mixed well first so that it is equally distributed without any pockets of high concentration as it can settle to the bottom. Bentonite will inhibit enzymes completely so you should remove the wine from bentonite prior to adding, or conversely it could be added once the desired effect has occurred to stop enzymatic activity.

Pectic enzymes as a method of clarification are not going to be as clearly obvious as traditional fining agents in that they don’t operate in the same way, so I don’t typically classify them as a fining agent. They don’t bind to anything in particular and precipitate it out, but rather break it down into smaller compounds that remain in solution.

There are times when pectic enzymes may be too effective, like if you’re doing a cold soak on white grapes before pressing. They may accelerate extraction faster than you might be used to and the wine could end up with extra astringency. But the bigger concern is misusing a very aggressive formulation before pressing and being unable to get clean pressing and separation.

As a whole, pectic enzymes can be a very effective tool depending on the desired use. Make sure that you understand what it is formulated for and what conditions it requires for efficient use.

Wine made from fruit other than grapes is one of the best places to use pectic enzymes.Brian Hosmer is the Winemaker at Chateau Chantal and Hawthorne Vineyards in Traverse City, Michigan. He holds a degree in enology and viticulture from Michigan State University.

ectinase is an enzyme that breaks the structural bonds that keep the tissue of grapes from being attacked by fungus or any other microbial threat. Once broken, the internal structure is exposed, which facilitates the extraction of juice (aka free run) and any material from the skin like polysaccharides, proteins, aroma precursors, etc.

I recommend using pectic enzymes to obtain a good yield from your grapes. Another good reason is because there is a lot of varietal character embedded in the pulp and epithelial tissue that can be extracted as well. I highly advise it for white and rosé winemaking. It will create cleaner wines with more aroma and finesse.

Since it helps with the free run of juice, I think its use is important regardless of the grape variety, so I’d recommend it for all uses and styles for economic reasons. However, the higher the varietal character of the grape, the more important its use. For example, you will need to use a more concentrated and complex cocktail of enzymes, where pectinase is one of them, for Albariño than for Pinot Gris, since Albariño has a richer and deeper varietal character. Pectinase also acts synergically with other enzymes like pectin lyases

Pectin is composed of complex polysaccharides that are present in the primary cell walls of plants.

In grapes, pectinases help break down grape pulp thereby releasing trapped juice, decreasing solids, increasing yield, and resulting in higher quality juice. Press cycles are optimized with its use and lees are more compact.

Pectinases are usually used with white and rosé juices. Red wines are fermented on their skins and are usually pumped over or punched down. These actions along with the alcohol and temperature extract the grape juice without the use of enzymes.

These enzymes are usually added at the crusher/destemmer or, if pressing whole clusters, at the press. As for dosage rates, use the manufacturer’s recommendations, using the upper limits with varieties that historically settle poorly,

and Beta-polygalacturonase. Combining them may achieve a more complete and efficient extraction of other precursors and components from the grapes.

While beneficial for most wines, you may not need to use it for matured red grapes, since their natural pectinase is released from the skin into the fermentation because of the nature of red winemaking.

As far as timing — the sooner, the better. The manufacturer of the enzyme typically gives a range for dosing, but I recommend doing a trial to see what suits your grape and sanitary conditions. Sometimes you don’t need as much as you think and sometimes it’s the opposite. Certain grapes have thicker skin that requires a higher ratio of enzymes. But it’s better not to overdo it. The importance of its usage is to help clarify but not in excess (over clarifying).

After clarification, there is a test called “alcohol pectin procedure.” It’s a very easy protocol that you can look up. You can do it on the juice before fermentation or on the wine after. If the test shows not a total depectinization, you can do another trial to see how much more enzyme you’ll need.

Compared to other methods of clarification like bentonite or gelatin, it’s more effective and creates less sediment, resulting in less loss.

like Labrusca and Muscadines.

Enzymes are proteins, so do not add them with SO2, which will denature them, nor with bentonite, which will precipitate them.

To evaluate whether an enzyme has worked and to the degree that it has worked, a winemaker will have to divide the grape pick into two lots, a control without enzyme and an enzyme-treated lot. And, because pectinases are used for optimizing pressing and cold settling, one does not get a second chance to add more enzymes. Just make a note to add more next time.

Pectinases are considered a cheap and easy way of clarifying juices. Many larger wineries will use flotation or centrifugation as faster ways of clarifying juices. Some wineries are concerned about using GMOs, but there are plenty of natural enzymes available from many suppliers.

QI HEAR A LOT OF WINEMAKERS TALK ABOUT “SACRIFICIAL” TANNINS. WHAT THE HECK IS SACRIFICED WITH TANNINS ADDED EARLY?

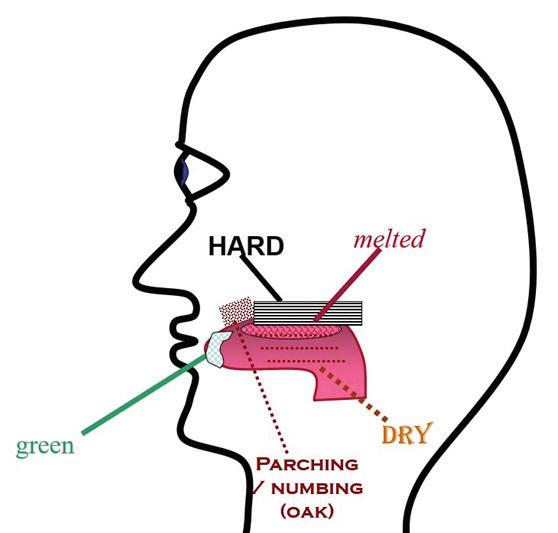

LARRY ROUX SYRACUSE, NEW YORKATannins, or the compounds in grapes (and oak barrels) that contribute to a pleasing sensation of astringency in red (and some white) wines, are found in grape skins and seeds. As a class of compounds, they are very important in winemaking as they are amazingly powerful antioxidants in addition to contributing in important ways to the sensorial quality of any given wine. A very tannic wine can make your mouth, tongue, and cheeks feel puckery and dry but a wine that has a balanced tannin level will have some “grip” while not being overpoweringly tannic. Big red wines like Petite Sirah and Cabernet Sauvignon will normally contain more tannins than lighter reds like Pinot Noir; the grape skin chemistry is just that different. As a result, Pinot Noirs generally feel softer on the palate but, due to their lower tannin content, might not age as long or as well as a more tannic red wine counterpart.

Proper tannin management during the winemaking process, from grape to bottle, is a skill set that can take years for winemakers to master because each variety, region, vineyard, and vintage is different. The natural tannin levels in any given red fermentation can vary greatly from one to the other. In addition to agitating the skins via punchdowns or pumpovers during the fermentation process (called “maceration”) to extract tannins, winemakers can also add tan-

nins at many points along the winemaking timeline. These tannins can be in liquid or powder form and are sourced from grape skins, grape seeds, oak wood, oak galls, and even quebracho wood (a South American tree). In addition, aging in oak barrels or using oak pieces or staves during aging are also technically a tannin addition as tannins present in the wood will get leached into the wine over time.

Intuitively, the closer a wine is to being bottled (and therefore then left to age and mellow on its own), the more careful a winemaker should be about making drastic tannin additions. Also, as my loyal readers know, I always recommend bench trials when making additions lest we go too crazy and make an addition we don’t like.

That being said, the safest and arguably best time to boost a wine’s tannin content is early on in the winemaking process, as they’ll have the most time to integrate into a wine and become a seamless supporting addition to the entire wine matrix. The term “sacrificial tannins” that you are asking about, are tannins added especially early on in the winemaking process, usually upon crushing or very soon thereafter. The idea is to add these tannins to must so that they will be oxidized early on in the winemaking process, instead of the grape skin tannins that you want to keep.

So, what gets “sacrificed” by adding sacrificial tannins? Many of the added tannins themselves. By adding extra tan-

The idea is to add these tannins to must so that they will be oxidized early on in the winemaking process, instead of the grape skin tannins that you want to keep.Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.com Oak galls are one source of tannins that winemakers may consider adding at various stages, including active fermentation as sacrificial tannin.

nin at the beginning and increasing the overall tannin content in any given fermentation, both grape tannins and the added tannins will be oxidized, or sacrificed. By adding extra tannins into the mix, a greater proportion of grape skin tannins will be preserved than if you didn’t add any extra tannin. Many winemakers also feel that by adding tannins at crushing (which act as an oxygen sink) they can get away with adding less sulfur dioxide at crushing as well.

There are many different types of tannin on the market from just about every major winemaking supplier. Most are classed as “fermentation tannins,” “aging tannins,” and “finishing tannins.” Finishing tannins are intended for use within 3–6 months prior to bottling, aging tannins are supposed to be added after all fermentations are complete, and, as you may presume, fermentation tannins are meant to be added during active fermentation.

Anecdotally, I’ve found that finishing tannins are gentler, more refined, and often more expensive as they tend to be aromatic oak extracts. One can add them usually up to 6 weeks before bottling because the effect is subtle, and the molecules are smaller and “marry” with the wine much more easily than the rougher aging and fermentation tannins. I wouldn’t waste my money by putting finishing tannins into a fermentation where they may just drop out of solution over time and not

“stick” in the final wine after the tumult of the fermentation, racking, and aging process. It’s critical to always do very careful bench trials when adding anything that close to bottling.

I find that aging tannins as a class can be quite angular and, depending on the brand, can be quite rough and aggressive. It’s important to do bench trials here as well, lest you add too much of something unpleasant. Fermentation tannins (or sacrificial tannins) tend to be the simplest and the least expensive and are often the roughest tasting. They really should be used only for fermentation. Even then, I would still tend to hew to the lower range of the manufacturer’s suggested addition rate, just to be safe.

Another more nuanced way to introduce tannins into a fermentation, and a method I often employ, is to add a 50/50 mixture of toasted and untoasted fine-grain oak chips to the fermentation at the rate of about 1–1.5 g/L. My favorite brand is Radoux (they have a great mixed product called “Duofresh”) and I find that it helps preserve color, serves as an oxygen sink, and also starts the wine along its way to gain in subtle oak character. The quality of the oak is very high; these aren’t “shop floor shavings” at all. Other oak producers sell similar products — they are worth seeking out as I find them to be subtler and a little more forgiving than adding straight up tannin powders or liquids to fermentations.

QCOULD YOU PLEASE CLARIFY FOR ME ONCE AND FOR ALL, DOES DISTILLED WATER HAVE A PLACE IN YEAST REHYDRATION? I HAVE FOUND CONFLICTING INFORMATION ON THIS FROM VARIOUS WINEMAKING RESOURCES.

MARIO SARRA VIA EMAILARehydrating dried yeast is a simple and straightforward process, and one that I find to be essential when using dried yeast for winemaking purposes.

The simple answer to your question is no, do not use distilled water for yeast rehydration. Distilled water is not osmotically balanced, which means that it can actually disrupt the delicate cellular membranes of your developing yeast. Distilled water is just that — distilled. That means that water (could be tap, or from any other source) has been boiled and the resulting steam condensed back into liquid form, leaving any salts, minerals, or other dissolved solids behind. As such, the water is too clean (free of anything except molecules of hydrogen and oxygen) and since physics dictates that solutes move from an area of high concentration to low concentration, distilled water will essentially push into the cell membrane until some yeast cells burst during the rehydration process or weaken the cellular membrane. The end result could be a loss of viability in your culture, which is the exact opposite of what you want when adding yeast to a fermentation. Less than fully viable yeast increases the chances of sluggish, stuck, or otherwise compromised fermentation, which can lead to not only sweet wine (stuck fermentation) but also a whole host of other wine flaws like increased VA (volatile acidity), acetaldehyde, or

ethyl acetate production (smells like oxidized apples and nail polish remover, respectively).

While it might be tempting to use distilled water because it doesn’t contain any chlorine (which can cause TCA or “corked” defects) and if in a closed container is sterile, it may actually be better to use bottled mineral water or even your own home’s tap water, as long as it doesn’t contain any chlorine. If you suspect your water has chlorine, it’s easy to buy faucet-mounted filters from any hardware store or online. Metabisulfite can also be utilized to knock chlorine out of water. If you’re worried about your water containing microbes (i.e., it’s not sterile) you can always boil and then cool your rehydration water before using it.

No matter which water you use, always follow the rehydration protocol for your yeast strain of choice. Most suppliers have directions on their website, if not on the actual packaging. I also like to use a rehydration nutrient, which helps the awakened yeast cells get off to their best start, no matter what the must or juice conditions. An example is GoFerm (a Lallemand product sold in the U.S. via Scott Labs). A small amount of the nutrient is dissolved in the warm water you’ll use for hydration. So you can use distilled water if the nutrients are added prior to the yeast. Again, it’s important to follow the manufacturer’s instructions.

Here are some handy conversions for everyone to note (save them somewhere, because you’ll always use them no matter what part of winemaking you’re doing). The internet is also full of handy automatic calculators, but it’s always faster to have some of these memorized so all you have to do is plug them into a calculator and don’t have to be bothered to search online.

1 hL= 100 L

1 L = 1,000 mL = 0.264 U.S. liquid gallon

1 U.S. liquid gallon = 3.785 L = 3,785 mL

1 kg = 1000 g = 2.2 lbs.

1 lb. = 0.454 kg = 454 g

These conversions can make reading between different suppliers and products a little easier. Happy re-hydrating!

QWHY DO YOU NEED TO ADD POTASSIUM SORBATE TO BLACKBERRY PORT AFTER BACKSWEETENING WHEN YOU ARE ADDING BRANDY TO PREVENT REFERMENTATION? A RECIPE I HAVE FOR BLACKBERRY PORT CALLS FOR POTASSIUM SORBATE AT THE END AND THEN THE SUGAR AT A RATE OF 3 LBS. PER GALLON OF WINE (355 G/L ) THEN A PINT OF BRANDY PER GALLON (125 ML/L ). I HAVE MADE THIS FIVE TIMES WITHOUT USING POTASSIUM SORBATE THE FIRST THREE TIMES. THE FOURTH TIME I HAD SOME REFERMENTATION AND CORKS WENT FLYING. MAYBE I DIDN’T HAVE ENOUGH BRANDY. BUT WHY IS THE SORBATE NEEDED IF ENOUGH BRANDY IS ADDED?

JERRY BLACK PORTLAND, MAINEAWell, in the olden days of fortified winemaking, potassium sorbate (a potassium salt of sorbic acid) wasn’t even a thing. While sorbic acid does occur naturally in some plants (rowan berries and hippophae berries, to be exact), almost all of the world’s potassium sorbate is made in a laboratory. In addition to potassium sorbate being a relatively modern, artificial ingredient, I also object to the aroma and taste of it in wine, which gives me fake pineapple and geranium vibes. Not so great. Luckily, there are some things you can do to ensure you get a completely arrested fermentation (and no re-fermentation) the next time you attempt your blackberry Port.

When making fortified wines, a must or juice is usually started just like normal, and then high-proof alcohol (like brandy) is gradually added in order to stop the fermentation. To make sure your wine gets really and truly “stuck,” I suggest employing these traditional basics: Fermentation kinetics management, temperature control, alcohol additions, sulfur dioxide additions, sugar additions, and, eventually at the end, filtration. (Note that these are the steps to producing a more traditional Port wine where little to no sugar is added to backsweeten, rather fermentation is halted in order to leave residual sugar from the original must/juice.)

• Non-robust fermentation: Under-pitch your yeast addition rate so that you don’t have a run-away fermentation that’s hard to arrest. Similarly, don’t over-feed your fermentation with yeast nutrients at the normal dry-wine level, since some of it will not be consumed when you add your alcohol to arrest the fermentation. Both of the above will help keep your fermentation moderate and easier to stop.

• Temperature control: By keeping your temperatures modest, you help ensure the fermentation won’t take off so quickly and, as such, will be easier to control and to stop when you do eventually add the alcohol. Ferment closer to the lower recommended temperature for your given strain.

• Alcohol addition: Indeed, the higher the alcohol, the less chance you’ll have of a refermentation. Most Port-style wines are over 18% alcohol, and to be safe, I’d aim for above 20% if your grape and wine style can handle the “heat.” You can fortify with a wide variety of spirits — because you’re not making your product to be sold commercially you have a lot of leeway. The traditional Port-style wine addition is brandy or grape spirits, often aged in oak. This remains a good choice but don’t turn down fruit-flavored spirits, unoaked spirits like grappa, or even a little Bourbon, if you’re hankering to make a Bourbon-barrel-aged type final product. No matter which spirit you use, be sure to do the algebra correctly . . . and don’t forget that “proof” is twice the alcohol content, i.e., an 80-proof spirit is 40% alcohol by volume.

• Sulfur dioxide addition: Yeast is sensitive (but not as sensitive as bacteria) to sulfur dioxide, so make sure a fortified wine has enough SO2. While it won’t kill yeast, it will inhibit them to a certain extent. Aim for bottling with free SO2 between 28–35 ppm for a reasonable balance between sensory quality (it won’t be too strong) and microbial abeyance.

• Optional “finishing sugar” addition: If the flavor profile of the wine and the wine’s balance warrants it, more sugar (in the form of table sugar, grape concentrate, etc.) can be added. The additional increase in osmotic pressure will further help retard yeast and bacteria growth.

• Optional filtration: Once the fermentation is stopped you will want to press, settle, and rack like normal. Be sure you keep measuring your Brix with a hydrometer (not a refractometer because the alcohol and any carbon dioxide bubbles will interfere) to make sure you’ve really stopped it. Once the wine is racked and has settled, sterile filtration is always a great technique to employ to make sure all microbes are excluded.

At the end of the day, if you really want to use potassium sorbate, you can add it at the rate of ½ teaspoon per gallon (3.8 L) of wine.

If you could put all the wonderful wines of Italy into one room, you would think you were in heaven! We do that almost every year at this early spring trade tasting, presented by Gambero Rosso. It features all Italian wines and is aptly named Tre Bicchierri, because the wines being presented are the top wines that earned the “three glass” distinction of quality. All the top producers from the various regions of Italy are there. It’s amazing to get so many of Italy’s best wines in one place. With all the indigenous and mainstream varieties, you have to stay focused on specific wines in a tasting this size.

The first year we visited this event we decided to focus on white wines from Italy. We found an abundance of one that really stood out that day . . . a grape called Vermentino, one that I did have experience working with but had limited success with. But its true capabilities were on display here at this tasting. The world of Vermentino awaited us with many excellent examples of the variability you experience between different producers and growing areas.

The earliest mention of Vermentino in literature is in 1658 in Piemonte, where vineyards were planted with grape varieties cortese (Cortese), nebioli dolci (Nebbiolo), and fermentino (Vermentino). Some scholars believe its name derives from the root, vermene, meaning young, thin, and flexible shoots. But the word origins going back to its first appearance in the literature, fermentino, meaning “ferment” referring to the fizzy character of young white wines, supports the former hypothesis. Vermentino has become the preferred name over the last 400 or so years with no real support as to why. Its morphological and DNA profile support that it is identical to Favorita in Piemonte and

Pigato in Liguria. The Ligurian grape, Rollo, is sometimes confused with Vermentino, and both can be referred to as Rolle.

As with many grape varieties, historical records are handed down from generation-to-generation by word of mouth unless some written record exists. One hypothesis was it was introduced to Sardegna from Spain, but the variety is not found in Spain. Another places its origins in Greece or the Middle East, but no scientific evidence supports that thought either.

Grown under the various synonyms, this supposed Italian grape is also widely planted in Southern France, notably in the Languedoc-Roussillon and Provence regions where its plantings have greatly increased in recent years.

In Italian grape acreage reports Favorita and Pigato are listed separately and Italy still retains the most acreage of Vermentino in the world, although France is not far behind. Typical to French regional AOC rules it is blended with local grapes as well as Muscats, Roussanne, and Carignane Blanc (Mazuelo). It can also be a blending component in Provencal rosé wines. Outside of its home region, it can also be found in Lebanon, Australia, Texas, North Carolina, Idaho, Virginia, Oregon, and California.

Vermentino is a white grape, very aromatic, and generally of very high quality. Viticulturally it is early budding, hence somewhat susceptible to spring frosts. It is mid-ripening and does best when grown near the sea in its native range of Italy, Southern France, the island of Corse (Fr.), and Sardegna (It.).

Vermentino grapes are thin-skinned and light in color. It is a vigorous vine that is drought-resistant and thrives in hotter climates. I have tasted Vermentino from Italy, France, and California, but

Vermentino is a white grape, very aromatic, and generally of very high quality.Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.com

100 lbs. (45 kg) Vermentino fruit

5 lbs. (2.3 kg) rice hulls

Distilled water

10% potassium metabisulfite (KMBS) solution (Weigh 10 g of KMBS, dissolve into about 75 mL of distilled water. When completely dissolved, make up to 100 mL total with distilled water.)

5 g Lalvin QA23 yeast (CY3079 can be used as a substitute)

5 g Diammonium phosphate (DAP)

5 g Fermaid K (or equivalent yeast nutrient)

Food-grade Brute bucket, about 45-gallons (170-L)

5-gallon (19-L) carboy

6-gallon (23-L) carboy

6-gallon (23-L) plastic bucket

Racking hoses

Inert gas (nitrogen, argon, or carbon dioxide)

Refrigerator (~45 °F/7 °C) to cold settle the juice (remove the shelves so that the bucket will fit)

Ability to maintain a fermentation temperature of 55 °F (13 °C). TIP: Use a 33-gallon (125-L) plastic can as a water bath. Place ice blocks in the water to maintain a relatively constant temperature.

Thermometer capable of measuring between 40–110 °F (4–45 °C) in one degree increments

Pipettes with the ability to add in increments of 1 mL

Tartaric acid (addition rate is based on acid testing results)

1. Crush and press the grapes. Mix in your rice hulls so that they are evenly dispersed with the must. Move the must directly to the press and press lightly until the juice flow diminishes. Increase the pressure of the press, taste the juice and transfer the hardest pressed juice to a separate vessel.

2. Transfer the juice(s) to a 6-gallon (23-L) bucket, keeping your fractions separate, if this is what you choose to do. During the transfer, add 3 mL of 10% KMBS solution per gallon of juice (0.8 mL/L). This addition is the equivalent of 50 mg/L (ppm) SO2. Move the

juice to the refrigerator.

3. Let the juice settle at least overnight. Layer the headspace with inert gas and keep covered.

4. Measure the Brix and acidity.

5. Adjust the titratable acidity to 6-7 g/L. If the acidity is greater than 7 g/L, consider the option of inoculating for the malolactic fermentation at the completion of the alcoholic fermentation described below.

6. When sufficiently settled, rack the juice off of the solids into the 6-gallon (23-L) carboy.

7. Prepare yeast. Heat about 50 mL distilled water to 108 °F (42 °C). Measure the temperature. Pitch the yeast when the water is 104 °F (40 °C). Sprinkle the yeast on the surface and gently mix so that no clumps exist. Let sit for 15 minutes undisturbed. Measure the temperature of the yeast suspension. Measure the temperature of the juice. You do not want to add the yeast to your cool juice if the temperature of the yeast and the must temperature difference exceeds 15 °F (8 °C). To avoid temperature shock, acclimate your yeast by taking about 10 mL of the juice and adding it to the yeast suspension. Wait 15 minutes and measure the temperature again. Do this until you are within the specified temperature range. Do not let the yeast sit in the original water suspension for longer than 20 minutes. When the yeast is ready, add it to the fermenter.

8. Add Fermaid K or an equivalent yeast nutrient.

9. Initiate the fermentation at room temperature ~65–68 °F (18–20 °C) and once fermentation is noticed, (~24 hours) move to a location where the temperature can be maintained at 55 °F (13 °C).

10. Two days after fermentation starts, dissolve the DAP in as little distilled water required to completely go into solution (usually 20 mL). Add directly to the carboy.

11. Leave alone until bubbles in the airlock are about one bubble per minute. Usually about two to three weeks. Measure the Brix every 2–3 days. If acidity is high, consider inoculating with a lactic acid bacteria culture.

12. The wine is considered dry when

you taste it and it does not taste sweet anymore. Add 3 mL of fresh KMBS (10%) solution per gallon of wine (0.8 mL/L). Transfer the wine to the 5-gallon (19-L) carboy and lower the temperature to 38–40 °F (3–4 °C). If there are any sulfide-like (rotten egg) odors, rack the wine off the lees. If the wine smells good, then let the lees settle for about two weeks and stir them up (bâtonnage). Repeat this every two weeks for eight weeks. This will be a total of four stirs.

13. After the second stir, check the SO2 and adjust to 30–35 ppm free.

14. After eight weeks, let the lees settle. At this point, the wine is going to be crystal clear or a little cloudy. If the wine is crystal clear, then that is great! If the wine is cloudy, then presumably, (if you have kept up with the SO2 additions and adjustments, temperature control, kept a sanitary environment, and there are no visible signs of a re-fermentation) this is most likely a protein haze and you have two options: Do nothing – it’s just aesthetics — or clarify with bentonite.

15. While aging, test for SO2 and keep maintained at 30–35 ppm.

16. Once the wine is cleared, it is time to move it to the bottle. This would be about six months after the onset of fermentation. Keep in mind this wine has had the malolactic fermentation inhibited (unless you opted to for an acid correction). If all has gone well to this point, given the quantity made, it can probably be bottled without filtration. Your losses during filtration could be significant. That said, maintain sanitary conditions while bottling, and you should have a fine example of a clean Vermentino.

Sulfur dioxide additions: The recipe calls for specific additions of sulfur dioxide at specified intervals. Once these scripted additions are made, you must monitor and maintain to 30–35 ppm. Adjusting as necessary using the potassium metabisulfite solution previously described or by methods of your own choosing. Testing can be done at a qualified laboratory, or in your home cellar using various commercially available kits.

in reading reviews, and with an upcoming trip planned to Texas, I am curious as to see if I can find some examples of Hill Country Vermentino varietals. Most reviews talk about it being made with all stainless fermentation and aging, something dear to my heart with such an aromatic variety. Winemakers should want to express the grape and not something around it to mask the flavors. Bonuses in the winemaking process are preserving this grape’s natural acidity by preventing the malolactic fermentation (certainly regional and stylistic dependent) and enhancing mouthfeel.

The descriptors of the flavors of Vermentino range from fragrant, mineral, floral, fruity, citrus, spicy, and tropical. The latter come about when the grapes are grown in warmer regions. But care needs to be taken to pick before the fruit acidity starts decreasing too much. Sometimes an acidity adjustment is necessary in warmer years and almost the norm in California.

My experience with these white grapes in both home and commercial settings is fruit that is grown properly does not require any extended skin contact to generate optimum aromatics. So what does it mean to properly grow this grape? Some keys to coaxing the most from the clusters while hanging in the vineyard include incidental but not direct sun exposure, good air flow through the canopy, and harvesting when the flavors are there, not necessarily the sugar.

Focusing on the winemaking side of the grape, recall that the aroma compounds are found in the skin of white grapes and therefore some skin contact is needed. I like to refer to best practices with Vermentino as incidental skin contact — just enough contact while the must is being de-juiced (the term I use instead the word press). De-juicing is the process of a series of light pressure increases in the press until the juice flow starts to decrease. Then I release the pressure, mix the must, and repeat. While easiest to do with a pneumatic membrane press, the home winemaker using a typical basket press can utilize rice hulls evenly distributed in the must

and then press normally until the juice flow starts to decline.

If you want to press firmer, switch to another receiving vessel and press harder for more yields. But make sure to treat these as two separate fractions. The firmer press may need some more attention because it will undoubtedly have a higher pH due to the hard press and longer skin contact.

I typically use one 4-cubic foot (0.11 m3) bag of rice hulls per ton (910 kg) of crushed and de-stemmed fruit (roughly 1 lb./0.45 kg rice hulls per 100 lbs./45 kg of grapes). Speaking from experience, I do not advocate for the use of enzymes as they can gum up your press process and overly complicate your day. Sure, you are going to find rice hulls in every nook and cranny of your press area, but that’s what brooms and wet/dry shop vacs are for!

Once you get your juice, allow it to cold settle overnight then rack off the grape solids (gross lees). The longer it settles the better the yield, but temperature and initial sulfur dioxide additions need to be considered. Depending on your growing region an acidity adjustment might be necessary. I am not afraid to adjust my acidity to around 6.5 g/L pre-fermentation with tartaric acid.

I use an aromatic yeast like QA 23 and ferment at a cool temperature of 54–59 °F (12–15 °C). After alcoholic fermentation is complete, I chill and add sulfur dioxide to prevent spontaneous malolactic fermentation (MLF). Certainly, if your acid is too high you could consider an MLF, but that is a stylistic choice. Keep the wine cool through the winter, stirring the lees to help with mouthfeel and bottle as the cellar warms in the spring. Voila! You have Vermentino!

At the annual Tre Bicchierri tasting, we experience many wonderful examples of what the grape variety can be all about. The Vermentino wines of Sardinia and Liguria are the benchmarks to match when you can get your hands on the grape to make in your own cellar. I long to make another Vermentino like a vintage I made in 2016. It was not a large volume that we made, but it was delicious and we can only be inspired every year when we return to this tasting and seek out the current year’s winners.

DON’T MISS OUT ON:

• 24 Big Seminars

• Group Interactive Workshops

• Tasting Party

• 8 Hands-On Winemaking Boot Camps

ADVANCED WINEMAKING

• Advanced Malolactic Techniques

• Maximizing Cold Soaks

• Willamette Valley Pinot Panel

• Post-Modern Tools to Build Wine Structure

• Crafting Age-Worthy Wines

• Making Brandy

GRAPE GROWING

• Canopy Management

• 5 Biggest Grape Growing Mistakes

• Backyard Grape Growing Q & A

GENERAL WINEMAKING

• Willamette Valley Winery Tours

• WineMaker Competition Awards Dinner

• Sponsor Exhibits

KIT WINEMAKING

• Keys to Wine Clarity

• Troubleshooting Q & A

• Award-Winning Country Fruit Winemaker Panel

• Crafting Italian Reds

• Calibrating Wine Equipment

• Basics of Wine Analysis & Testing

• Making Limoncello & Other Citrus Liqueur

GROUP INTERACTIVE WORKSHOPS

• Advanced Kit Techniques

• Award-Winning Kit Winemaking Roundtable

WINEMAKER BOOT CAMPS

• Side-by-Side Oak Trials

• Winemaking Table Topics

• Winemaking Hot Subjects

• Willamette Valley Winemaking

MEET WITH WINEMAKING SUPPLIERS

• Advanced Winemaking from Grapes

• 2-Day Fundamentals of Modern Wine Chemistry

• Winemaking from Grapes

• Distilling

• Small Winery Start-Up

• Home Wine Lab Tests

• Backyard Grape Growing

• Judging & Scoring Wines

• Willamette Valley Winery Tours

As an attendee, you’ll have the opportunity to check out the latest equipment, products & supplies from many of these leading winemaking vendors Friday & Saturday.

TITLE SPONSORS

EXHIBITING SPONSORS

SUPPORTING SPONSORS

Blichmann Engineering Home Fermenter RJS Craft Winemaking Winexpert

THURSDAY, JUNE 1 • 10 AM – 4:30 PM

Maximize your learning by taking two different Boot Camps. Full-day, small-class Boot Camps will run pre-conference on Thursday and post-conference on Sunday from 10 AM to 4:30 PM and include lunch. Attendance is limited to just 35 people per session and do sell out. This add-on Boot Camp beyond the conference registration is a great opportunity to get an in-depth learning experience in a small-class setting and learn hands-on from experts.

ADVANCED WINEMAKING FROM GRAPES

Go beyond the basics and understand complex techniques to get the most from your winemaking using fresh grapes. This workshop intended for intermediate and expert home winemakers will tackle a range of tips: From dialing in extraction levels on the front end all the way to protecting your wine with advanced tips through bottling.

DISTILLING

Walk through the small-scale distilling process. You’ll leave understanding the various types of small still equipment, as well as the small-scale distillation process for brandy, whiskey, rum, and gin. Get your questions answered throughout the full day as you learn the art of distillation using a small still.

WINEMAKING FROM GRAPES

Learn all the steps of making wines from grapes including crushing and fermenting all the way to bottling. You’ll work with fresh grapes and operate the different pieces of equipment and the tests you’ll have to run on your wine.

You’ll learn site selection, vine choice, planting, trellising, pruning, watering, pest control, harvest decisions plus more strategies to successfully grow your own great wine grapes.

Step-by-step teaching on how to properly test your wine for sulfites, malolactic, acidity, and pH. You’ll have the chance to run these different tests yourself to give you a valuable hands-on learning experience so you can accurately run these tests on your own wine at home.

Tour several wineries as you explore the world-famous Willamette Valley and have plenty of opportunities to ask their professional winemakers your winemaking and grape growing questions. You’ll be served lunch along the way and have tastings of award-winning wines.

Learn on Thursday and Sunday from wine expert Clark Smith how to use wine chemistry as a practical tool to improve your winemaking. You’ll cover wine chemistry from crush to bottling and how it can inform better decisions resulting in better wine. *This 2-day boot camp includes a 550-page manual that will be a valuable wine reference for this 2-day workshop and for years to come.

Learn how to evaluate your own and other wines in the same way as a trained wine judge so you can use these skills to help your own winemaking. Gain a sensory appreciation for various common faults and how to properly use the 20-point UC-Davis judging sheet as a foundation for evaluating wines.

Walk through the steps, planning decisions, and key financial numbers you need to know if you want to open a smaller-scale commercial winery. Learn how to better achieve your dream of running your own small winery.

Tour several wineries as you explore the world-famous Willamette Valley and have plenty of opportunities to ask their professional winemakers your winemaking and grape growing questions. You’ll be served lunch along the way and have tastings of award-winning wines.

Pre-Conference WineMaker Boot Camps & Winery Tours • Thursday, June 1, 2023

Fundamentals of Modern Wine Chemistry – Day 1 of 2

10 AM – 4:30 PM

Winemaking from Grapes

Day #1 Friday • June 2, 2023

8 – 9 AM

9 – 9:15 AM

9:30 – 10:45 AM

10:45 – 11:15 AM

11:15 AM – 12: 30 PM

12:30 – 1:45 PM

–

PM

Calibrating Wine Equipment

Advanced Winemaking from Grapes

Backyard Grape Growing

Distilling

Home Wine Lab Tests

Willamette Valley Wineries Tour

Breakfast & Registration

Welcome & Introduction

Canopy Management Keys to Wine Clarity

WineMaker Exhibits

Making Brandy

Advanced MLF Techniques

Award-Winning Kit Winemaker Panel

Lunch & Keynote: Southern Willamette Valley Winemaking with King Estate

WineMaker Exhibits

–

Basics of Wine Analysis & Tests

Willamette Valley Pinot Panel

WineMaker Exhibits

WineMaker Workshop: Side-By-Side Oak Trials

WineMaker Tasting & Wine Sharing Party

DAY #2 Saturday • June 3, 2023

8:30 – 9:30 AM

9:30 – 10:45 AM

10:45 – 11:15 AM

11:15 AM – 12:15 PM

12:15 – 1:45

WineMaker Workshop: Winemaking Table Topic Talks

5 Biggest Grape Growing Mistakes

WineMaker readers and Publisher Brad Ring recently spent a week exploring beautiful wine regions in Chile and Argentina. The group experienced a South American harvest during visits to wineries on either side of the towering Andes Mountains during WineMaker’s Chile-Argentina Wine, Bike & Hike Adventure in March. We visited wineries from the large and well-known like Cono Sur in Chile to the small husband-wife-run Atillio & Mochi for a very personal tour and tasting in Chile’s Casablanca Valley. All along the way we had the chance to walk vineyard rows bursting with fruit, taste ripe grapes on the vine, and meet with local pro winemakers happy to answer questions from North American home winemakers while we enjoyed sampling their wines.

We learned the wonders of a South American asada eating like kings and queens with many of our delicious winery meals cooked a few feet away from our tables over open flame and paired with glasses of Carménère and Cabernet in Chile and Malbec in Argentina. We earned those plates of steak with scenic bike rides through endless vineyards and hikes along ridgelines covered in cacti and grapevines.

We visited in mid-March during the excitement of harvest and we were lucky enough to watch just-picked Malbec grapes being destemmed carefully by hand and moved directly into new French oak barrels for fermentation at Bodega Monteviejo in Argentina’s Uco Valley. We tasted 11 di erent grape varieties still on the vine for a truly unique side-by-side tasting experience at Viña MontGras in Chile’s Colchagua Valley. Some readers even helped with pre-dinner punchdowns at Flaherty Wines in the Aconcagua Valley of Chile.

It was a treat to learn about the biodynamic vineyard of Chilean Carménère pioneer Alvaro Espinoza at his Antiyal winery, hiking to see 1,000year-old Incan petroglyphs before a tour and lunch at Viña In Situ whose logo is one of these same petroglyphs from the hillside above their vineyards, and tasting barrel samples as well as unlabeled 16-year-old Malbecs at Hacienda del Plata in Mendoza, Argentina. And it was a trip made extra special by sharing it with 18 fellow home winemakers passionate about wine and winemaking while exploring the mountains, valleys, and special culture of wine regions in both Chile and Argentina.

Our next WineMaker trip with space available will be a South Africa Wine & Safari Adventure next March 18–26, 2024. Details on this trip combining both winery tours and a wildlife safari can be found at winemakermag.com/ trip. We hope you can join us on a future WineMaker adventure. ¡Salud!

Whether it is to feed our winemaking hobby as we wait for grapes to ripen, put to use a surplus of fruit growing in the backyard, or simply because they are delicious summer sippers to enjoy on a warm evening, fruit wine should be embraced by every home winemaker. The options are nearly limitless when considering the varieties of fruit and combinations that can be made from them, not to mention dryness levels and even wine styles that can di erentiate wines from the same fruit.

No matter where you live, there is sure to be locally grown fruit that will make a tasty wine. Getting ripe fruit in season is the best place to start when considering a fruit wine recipe; because starting with excellent fruit (just like when making wine from grapes) is a key to crafting an award-winning fruit wine.

Of course, starting with great fruit only lays the foundation for a great wine. There are also unique techniques used in fruit winemaking that are less common when making wine from grapes, such as sugar additions both prior to fermentation to bring up the Brix (chaptalization) and after fermentation (backsweetening) to better express the fruit character. Methods of collecting juice, nutrient additions, and even aging techniques are also unique to fruit wines.

If you have never made a fruit wine before, the best place to start is with a trusted recipe (and then tweaking it to match the fruit you have and style you want to make). So when we thought about pulling together a collection of fruit wine recipes, our first instinct was to collect recipes we knew for a fact would make gold medal-quality wine. For that, we reached out to amateur winemakers and asked them to share their recipes that resulted in gold medals in competition and asked for their secrets. We’re excited to share four unique fruit wine recipes that are perfect for summer.

Won Gold Medal in the 2022 WineMaker International Amateur Wine Competition (Stone Fruit category)

Our winemaking journey started in 2017 when I was working on my capstone project in graduate school. I was working on my Masters of Business (MBA) in Phoenix, Arizona. My capstone project required a paper with a word count of 10,000 words, plus a presentation to the professors in the department. My graduate school experience provided the opportunity to complete the research needed on how to lay out a vineyard, determine which fruit would grow in western Kentucky, and the chronic setbacks associated with a wet climate. Two years after graduate school, my wife and I moved back to Beaver Dam, Kentucky. That’s when we decided to make our first batch of wine. Peaches were the fruit in season.

For me, there’s nothing like biting into a perfect juicy yellow peach. So, when deciding which fruit would be our medium it was easy. We wanted those enjoying a glass to have the same experience, except without having peach juice running all over their face. Our first batch of wine was started August 10, 2020 which, by the way, was poured down the sink drain. Our second peach wine was the one that received a gold medal in the WineMaker International Amateur Magazine competition in 2022. This is our recipe for that wine, which can be scaled to meet your batch size.

3 lbs. (1.4 kg) yellow peaches (halved, pitted, frozen)

2 lbs. (0.9 kg) granulated sugar Spring water (if needed to hit volume)

1.5 tsp. acid blend

1 tsp. pectic enzyme

0.25 tsp. grape tannin

0.5 tsp. yeast energizer

1 Campden tablet

0.5 tsp. potassium sorbate

LorAnn peach oil

Lalvin K1-V1116 yeast

We source yellow peaches locally around mid-June and then slice each peach in half and remove the pit by hand. Then we place them in clear freezer bags weighing approximately 3 lbs. (1.4 kg) each for one gallon (3.8 L) of wine. I suggest freezing the fruit for a minimum of 90 days, as this will aid in the fruit producing more juice when thawing out. When the 90 days is up, or whenever you’re ready to make some wine, just remove the peaches from the freezer and allow them to thaw in your fermentation vessel (we use a 5-gallon/19-L foodgrade bucket).

Add granulated sugar to the thawed peaches. Press the peaches and (if needed) add water up to one gallon (3.8 L). Add enough sugar to bring the specific gravity up to 1.090 (21.6 °Brix), which will result in a wine of about 12% ABV. This is generally around 2 lbs. (0.9 kg) of sugar, but will depend on the sugar concentration of the fruit. Take another Brix reading 24 hours after adding the sugar using a refractometer and adjust if necessary. We then add acid blend, pectic enzyme, tannin, yeast energizer, and one crushed Campden tablet and stir to mix.

Rehydrate and then pitch your yeast. We prefer Lalvin K1-V1116. Fermentation is around 65 °F (18 °C) for 12–15 days.

It’s imperative you press down the fruit cap and stir at least twice a day for the first six days. After that, stir just once a day. Once the hydrometer reads 1.000, fermentation is considered complete. Now it’s time to use a nylon mesh straining bag in a clean food-grade 5-gallon (19-L) bucket. Strain the fermented wine through the bag into the second bucket and squeeze the wine from the mesh bag. Allow the wine to rest for 24 hours so the lees settle to the bottom of

the bucket.

Siphon the wine to a sanitized carboy. We add one Campden tablet per gallon (3.8 L) at this point to preserve the natural color and protect against bacteria. We recommend cold stabilization for 30 days at 27 °F (-3 °C). You will need to rack the wine after cold stabilization is complete.

Clearing peach wine can be done several ways; we prefer to use natural aging, however, you may also use bentonite. Once the wine is clear, we add 0.5 tsp. potassium sorbate stabilizer per gallon (3.8 L) to prevent renewed fermentation from backsweetening.

Backsweetening is accomplished by making a simple syrup. We use a 1:1 ratio of granulated table sugarto-spring water. You want to bring the water to a boil, then add an equal amount of sugar. Backsweeten to taste; the sugar should help accentuate the peach flavor, but not overpower it with sweetness. This took about 10 cups of simple syrup for one gallon (3.8 L) of wine (with this addition, the resulting wine volume is a little over 1.5 gallons (~6 L). To really kick up the peach flavor, which can sometimes be dulled by fermentation, add 0.625 oz. (18.5 mL) LorAnn Peach oil 24 hours after the potassium sorbate addition. Remember, fruit wine peaks at 15 months.

I did not like wine until my husband and I took a trip to Napa, California, in 2007. A woman at St. Supéry Estate Vineyards & Winery took the time to teach me about wine. After trying a Moscato, I fell in love. I have a very curious mind so my husband bought me everything I’d need to start making my own wine. I made a few kits and then in 2011 we moved to Grand Junction, Colorado, only to find out I moved to the Grand Valley AVA haven. In 2013 I started making wine with fresh grapes and entering competitions to get honest feedback. I make a large array of wines — from Vitis vinifera varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon and Muscat, to hybrids including Crimson Cabernet and Brianna, as well as fruit wines.

This particular wine came about after a friend with a few cherry plum trees in her yard called me and asked if I wanted some plums (she knew I made wine but also did not want to pick them up to mow around them).

After picking for half a day, I ended up with approximately 90–100 lbs. (41–45 kg) of plums. I washed them, pitted, halved, and froze them. After a couple weeks in the freezer and trying to research which yeast I was going to use, I thawed them into three separate batches using nylon mesh bags for easy extraction of fruit. Since I do not get YAN (yeast assimilable nitrogen) levels tested on my fruit wines, I count on recipes and trials. This was my first plum wine, which fortunately hit the mark on what I was looking for.

30 lbs. (14 kg) cherry plums (halved, pitted, frozen)

20 lbs. (9 kg) table sugar

~5 gallons (19 L) water

7.5 tsp. acid blend

5 tsp. pectic enzyme

5.9–9.5 tsp. Go-Ferm

(yeast-dependent)

2.5 tsp. Fermaid K