Algiers

VOLUME 1: ARCHITECTURAL & HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE

United States Embassy, Algiers, Algeria • Chief of Mission Residence (CMR)

Historic Structure & Cultural Landscape Report

Final Submission • 14 June 2023

OBO Contract # SAQMMA15D0118 • Task Order # 19AQMM19F3532

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Introduction / CMR

OVERVIEW

This four-volume set comprises the Historic Structure and Cultural Landscapes Report (HSR/CLR) for the Chief of Mission Residence that is part of the US Diplomatic Mission properties in Algiers, Algeria. The US Department of State, Bureau of Overseas Buildings Operations (OBO) commissioned this HSR/CLR from the Davis Brody Bond Study Team comprised of Davis Brody Bond, architects and planners, Robinson & Associates, architecture researchers and historians, Building Conservation Associates, building restoration specialists, Rhodeside Harwell, landscape architects, Thornton Tomasetti, structural engineers, and WSP, MEP engineers. The Team developed this report after visiting the CMR during the week of June 26-30, 2022. Volume 1 will be available to the broad reading public. Volumes 2, 3, and 4 will be available to readers with USG authorized access. Each volume contains specific information as described following:

• Volume 1 presents the architecture and landscape histories and significance of the property, its characterdefining features, and its status under Algerian preservation/cultural heritage law.

• Volume 2 documents and discusses existing conditions of the landscape, building, and building systems.

• Volume 3 includes paint and stucco analyses, and estimated construction cost information.

• Volume 4 offers operations and maintenance information and recommendations.

While it is possible to use each volume independently, the Study Team recommends that authorized first-time readers start at the beginning, developing an acquaintance with Volumes 1 and 2, before passing on to Volumes 3 and 4.

PURPOSE OF THE REPORT

Paraphrasing the SOW, the purpose of this Historic Structure and Cultural Landscapes Report follows:

The objectives of the HSR/CLR are to identify and document original and lost design and building history, and to describe the current conditions of architecture and building systems. It includes discussion of deterioration and causes; and proposes treatments to maintain and restore its historic character within the requirements of DoS Diplomatic use.

The content and objectives of the HSR/CLR are guided by the How to Write a Historic Structure Report by David H. Arbogast (2011); “Preservation Brief 43: Preparation and Use of Historic Structures “, National Park Service, 2005; Chapter 8 w/appendix C of NPS-28: Cultural Resource Management Guideline; The Secretary of the Interior's Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties with Guidelines for the Treatment of Cultural Landscapes ed. by Charles Birnbaum (1996); and “Preservation Brief 36: Protecting Cultural Landscapes: Planning, Treatment and Management of Historic Landscapes,” National Park Service, 1944.

A DoS HSR/CLR has critical differences from a traditional HSR/CLR produced for structures and landscapes within the United States which may be eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. Its sole purpose is to fulfill a legal and moral stewardship responsibility within and subject to the requirements of the DoS and a diplomatic mission: it will inform and guide the Department in its use and maintenance of the structure and grounds and provide the knowledge by which to judge potential proposed alterations. A majority of the document itself will not be distributed outside DoS: Volume 1, “Architectural and Historical Significance” section will be available for academic or public research purposes.

Introduction / CMR

METHODOLOGY

Research methods include the examination of both primary and secondary sources from select US, Algerian, and French archives and repositories. Sources are listed in the bibliography; some appear in the text.

The existing building and landscape were studied during a Site Trip the week of June 26-30, 2022, by the A/E team of historical, engineering, preservation, conservation, landscape, and architectural professionals. During the visit, the team conducted field observation and recording, including review and field verification of extant documentation, field measurement and sketching, detail and HABS-level 2 photography, and laser scanning.

Team members interviewed Embassy staff including David Treleaven, Tewfik Tizioualou, and Mahdi Tayeb, Post Building Systems SMEs, and CMR house staff including Mr. Boudjema, Chief Gardener regarding the practices of day-to-day and special event use, the history of maintenance, equipment and systems upgrades, and prior and forthcoming renovation projects. Team members performed site and building tours of areas of disciplinary interest accompanied by Post SMEs. The team members participated in a tour of the DCMR led by Professor Samia Chergui, an Algiers architectural historian. A local preservation/conservation contractor with project experience at the CMR, Mr. Francisco Javier Escribano Lax, led a tour of the CMR, highlighting conservation work performed, methods and materials used, and what he viewed as appropriate next steps in the stewardship of the building.

SITE VISIT TEAM

ARCHITECTURE / ENGINEERING CONSULTANT TEAM

Davis Brody Bond

Architecture

• Christopher K. Grabé, FAIA

• A. Eugene Sparling, AIA

WSP

MEP / IT / SEC

• Michael Cosentino

Thornton Tomasetti

Structure

• Evan Lapointe, PE

Robinson & Associates

Historical Analysis

• Daria Gasparini

• Tim Kerr

Professor Samia Chergui

University of Saad Dahleb, Bilda, Algeria

Local Architecture History and Research

Rhodeside & Harwell

Landscape

• Faye Harwell, FASLA

• Rachel Schneider, LA

BCA

Paint & Materials Analysis Field Measuring, Scans, and Photographs

• Christopher Gembinski (BCA)

• Rimvydas (Danius) Glinskis (BCA)

• Alexander (Alex) Ray (BCA)

• Erica Morasset (BCA)

• Fernando Viteri (Langan)

• Joseph Magers (Langan)

• T. Whitney Cox (Whitney Cox Photography)

Introduction / CMR (cont’d)

US DEPARTMENT OF STATE BUREAU OF OVERSEAS BUILDINGS OPERATIONS (OBO)

• Virginia Price, OBO, OCH

• Andrew Fackler, OBO, OCH

EMBASSY OF THE UNITED STATES ALGIERS, ALGERIA

• Ambassador Aubin, AMB

• Mr. Aubin

• Kristin Rockwood, MGT

• Greg Geerdes, RSO

• Tobias Slaton, RSO Office

• David Treleaven, FM

• Tewfik Tizioualou, FM Office

• Leila Kouroughli, FM Office

• Mahdi Tayeb, FM Office

Visitor to Embassy

• Francisco Javier Escribano Lax (Masmoudi Construction)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This historic structure and cultural landscape report for the Chief of Mission Residence of the US Diplomatic Mission in Algiers benefits from the cooperation and contributions of individuals and organizations which Davis Brody Bond gratefully acknowledges.

First and foremost, we thank Ambassador Aubin who generously opened the CMR to the team throughout the five-day visit and primed the Post to support the project wholeheartedly. The report also benefits from the contributions of others at Post. Mr. Dan Aubin, guided tours of the CMR and DCMR and freely shared his extensive experience of both buildings, offering knowledge and ideas about their proper preservation and stewardship. Kristin Rockwood, MGT, and Tobias Slaton (RSO office) provided an introductory tour and security briefing, and image review. Ms. Rockwood arranged and accompanied an evening tour of the Casbah. Greg Geerdes, RSO, offered a focused security briefing. David Treleaven, FM, provided the Team with workspace, building access, secure storage, background information, access to Post archives, and generally assured a smooth and productive Site Visit. Tewfik Tizioualou, Mahdi Tayeb of the FM Office, facilitated meetings between visiting consultants and Post maintenance and building engineering staff, provided recent building maintenance information and more. Leila Kouroughli in the FM offices facilitated local travel and coordinated expert assistance for arrivals and departures.

We are very grateful for the extensive research work performed by Samia Chergui, Professeur en histoire de l’architecture, Institut d’Architecture et d’Urbanisme (Université Saad DAHLAB/Blida 1) who uncovered in Algerian archives and repositories information that informs the entire study, including building and urban histories, significant historic maps and other records. Mr. Francisco Javier Escribano Lax, an Algiers architectural conservation contractor met with the Team and led a tour of the CMR highlighting conservation work he had completed there and offering thoughts on future projects.

The Team also greatly thanks Virginia Price, the OBO project manager for the project. Virginia gathered and provided access to records in the Real Estate division at OBO as well as documents in the Cultural Heritage office, including drawings, photographs, reports, and correspondence that helped document acquisition of the buildings by the United States, as well as changes to the CMR and DCMR during US ownership. She also helped organize the Casbah tour, which greatly added to the Team’s understanding of architecture in Algiers during the periods of Ottoman and French rule.

1.1 Executive Summary / CMR

The US Department of State, Bureau of Overseas Buildings Operations (OBO) commissioned this four volume Historic Structures and Building Conditions Report / Cultural Landscapes Report from the Davis Brody Bond Team comprised of Davis Brody Bond, architects and planners, Robinson & Associates, architecture historians, Building Conservation Associates, building restoration specialists, Rhodeside Harwell (RHI), landscape architects, Thornton Tomasetti, structural engineers, and WSP, MEP engineers. This four-volume report was developed following a visit to the CMR during the week of June 26-30, 2022. It includes an overview of the architecture and landscape histories and significance of the property now serving as the Chief of Mission Residence for the US Embassy in Algiers. The report also includes a survey of the existing conditions of the building and site, materials analysis, and an operation and maintenance program. A summary of the four volumes of the report follows.

The Chief of Mission Residence at 6 Chemin Cheikh, Bachir Ibrahimi in Algiers was built as a luxurious villa on northeast-facing slopes above the city in the midnineteenth century and remodeled multiple times. The property appears on the OBO List of Significant Properties and on the Secretary of State’s Register of Culturally Significant Properties. It is not identified as a historic cultural resource under Algerian law.

VOLUME 1 ARCHITECTURE AND HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE

Volume 1 describes the Architectural and Historical Significance of the property. It traces the urban development of Algiers and offers a broad outline of Algerian architecture and landscape design in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It describes the CMR’s chronology of ownership, use, and development in its context. There is a summary of ongoing US-Algerian diplomatic relations beginning in Ottoman times.

Following the US Department of the Interior guidelines for applying the National Register of Historic Places criteria for evaluation, Robinson & Associates establishes a long period of significance for the CMR from 1866-1948. Together, Rhodeside Harwell and Robinson & Associates provide detailed descriptions of the landscape and the building exteriors and interiors, identifying copious character-defining features.

VOLUME 2

EXISTING CONDITIONS

During the June 2022 Site Visit, DBB Team members examined the CMR, recording with field notes, sketches, and photographs existing conditions pertaining to their respective professional disciplines. Volume 2 presents the record created, and disciplinary analyses of the existing conditions in the field. In summary:

CHAPTER 1

STRUCTURE

Thornton Tomasetti (TT), project consulting structural engineer reviewed visible structure at all levels and examined select concealed structure with the use of a borescope. In addition, TT visited existing outbuildings. The structural report finds the building structure to be in good condition overall with localized conditions warranting attention.

CHAPTER 2:

MEP/FP/FA/IT/TSS

WSP, project consulting building systems engineer reviewed and documented existing mechanical, plumbing, fire protection, electrical, telecommunications, and security systems installations in the field. In addition, WSP interviewed engineering staff charged with the operation and maintenance of existing systems. Generally, WSP finds the existing building systems to be in acceptable working order. For details, please refer to Vol. 2.

CHAPTER 3

LANDSCAPE EXISTING CONDITIONS

Rhodeside Harwell (RHI) walked, analyzed, photographed, and sketched the CMR site. It describes the landscape spatial organization, topography, uses, vegetation, and defining features in text and graphics.

CHAPTER 4

LANDSCAPE TREATMENT

Rhodeside Harwell (RHI)'s section on landscape treatment suggests establishing a philosophy and strategies of care for the CMR property. If offers specific treatment recommendations and suggests periodic maintenance practices.

CHAPTER 5

EXISTING ARCHITECTURE

BCA and DBB reviewed, documented, and discussed the building interiors and exteriors during the Site Visit. This chapter presents representational spaces by way of measured room plans, HABS Level 2 photographs and detail photographs. A data sheet for each representational space notes character-defining architectural features, their historic and current materials, assesses their conditions, and identifies treatment guidelines. Exterior elevations and spaces are similarly described. Overall, BCA and DBB find the building to be in good condition.

CHAPTER 6

TREATMENT OPTIONS AND WORK RECOMMENDATIONS

Guided by the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties, this chapter proposes that all work on the CMR shall respect the significance and historic condition of the building and its constituent elements. Preservation Zoning diagrams show the relative importance of different spaces, and treatment guidelines suggest appropriate conservation strategies in different preservation zones.

CHAPTER 7

ACCESSIBILITY

The CMR was built before accessibility was a matter of concern to most architects and many building owners. This chapter maps accessibility issues in the house and landscape. It offers conceptual remedies for selected instances of non-compliance. These range from simple measures to more complex and costly interventions, such as adding an accessible toilet room, a lift, or elevator. Notably, ABA Guidelines do not require retro-active compliance of pre-existing elements. However, in historic buildings, alteration projects do trigger accessibility upgrades in the work area. To respect and maintain the historical significance of the CMR’s representational spaces, OBO/PDCS/DE and OBO/OPS/CH guide the precise character of accessibility upgrades.

VOLUME 3

DIAGNOSTIC DOCUMENTATION

BCA performed extensive diagnostic sampling for paint and exterior stucco. Analysis reports on the samples provide bases for historically appropriate restoration work. The volume also includes a cost report.

VOLUME 4 OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE PROGRAM

The Operations and Maintenance Program assists and guides CMR stakeholders charged with the care and protection of this culturally significant property.

DIGITAL COMPONENTS

The HSR/CLR project deliverables comprise standalone digital files separate from this four-volume print report. Among them are raw, registered and photo-textured laserscanned point clouds of the building, and a Revit model constructed from the point cloud. Digital work also includes panoramic virtual tours with interactive points of interest content for OBO-identified representational spaces. Digital products will be posted independently of print documents.

Detail from Figure 1.2.2

Detail from Figure 1.2.2

1.2 Historical Background & Context / CMR

DEVELOPMENT OF ALGIERS AND ITS SURROUNDINGS

Origins

The Imazighen, known also as the Berbers, have been present in the Maghreb (the part of North Africa west of Egypt) since the beginning of recorded history, having been noted by ancient Egyptian dynasties as early as the thirteenth century BCE. Reaching the area by way of the Mediterranean Sea, Phoenician traders from what is now Lebanon established hundreds of settlements along the North African coast after 800 BCE. One of these settlements became known as Icosium. Both the Carthaginians in the fifth century BCE and later the Romans knew the town (Figure 1.2.1). The inhabitants of Icosium occupied four of the small islands in what is now the Bay of Algiers and a narrow strip of land along the shore. The town became a Roman colony in the first century CE. The Romans laid out Icosium’s streets in a grid pattern, established public baths, a necropolis, and other urban elements, and constructed a rampart with towers to protect the land side of the settlement. They also built villas with gardens in the hills outside the walls. Remains of Roman Icosium have been found in what is now known as the Casbah.1

Firmus, a Berber Numidian prince and son of a Roman general, sacked Icosium in 373 CE as part of a tribal revolt against the established Roman authority. The Romans put down the revolt, but the town was conquered again in the fifth century, this time by the Vandals, a Germanic tribe that crossed into Africa via Spain.2 The Vandals controlled all of Roman North Africa until the Byzantine general Belisarius and his army defeated them in 533. The Byzantines and then Islamic Arabs reduced

Icosium to ruins by the seventh century, and the settlement would not be revived until the tenth century, by which time the dominant cultural and political influences emanated from Islam, which had been introduced in North Africa from Egypt.

Indigenous Berbers initially opposed foreign rule by the Islamic caliphate headquartered in the Arabian Peninsula, but Arab forces ultimately prevailed and extended their rule throughout North Africa and, eventually, across the Mediterranean into the Iberian Peninsula. During the Fatimid period (909–1171), the rule of the area encompassing modern-day Algeria was left to the Zirids, a Berber dynasty that centered significant power in the region for the first time. In 944, Buluggin (or Bologhine) ibn Ziri, the founder of the Zirid dynasty, established a town on the site of ancient Icosium. He called it al-Jaza’ir, a name meaning “the islands” in reference to the islands off the coast. The period that followed was marked by constant conflict and economic decline. Algiers was ruled by successive Arab dynasties as a minor port from the arrival of the Almoravids in the early twelfth century until the sixteenth century.3 The Arab Muslims fortified the town with perimeter walls, which are believed to have incorporated existing ramparts and later formed the basis of the walls built during Ottoman rule.4

A watershed moment for medieval Algiers was the recapture of Spain by Christians in the fifteenth century, which resulted in a wave of Muslim refugees to the city. The Christian powers in Europe ended trade across the Mediterranean from North Africa, reducing markets for the products of Arab and Berber agriculture and industry. Some of those formerly engaged in merchant enterprises therefore turned to privateering the seizure of money, commercial products, ships, and sailors through piracy.

1. “Icosium,” The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites, Richard Stillwell, William L. MacDonald, Marian Holland McAllister, editors (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1976), Tufts University website, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus% 3Atext%3A1999.04.0006%3Aentry%3Dicosium, accessed September 24, 2022; “Algiers” and “North Africa,” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica website, https:/www.britannica.com/place/Algiers, accessed September 24, 2022.

2. Stillwell, et al., “Icosium,” The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites; “Algiers,” Encyclopædia Britannica.

3. Helen Chaplin Metz, ed., Algeria, a Country Study, 5th edition (Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, 1994), 11-17.

4. Zeynep Çelik, Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 13; Metz, Algeria, a Country Study, 11.

1.2. Historical Background & Context / CMR

Privateering soon became a state-sponsored business in North Africa, with Algiers becoming “the privateering state par-excellence” between 1560 and 1620. The practice was organized and regulated by the kingdoms along the coast. Captains of the corsairs who carried out the raids on mercantile shipping formed a community known as the taifa that ensured the stability of the industry. Europeans who converted to Islam could become members of the taifa.5

Algiers During the Ottoman Period (Early 1500s–1830)

Algiers came under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, centered in Constantinople (now Istanbul), Turkey, in the early sixteenth century. Supported by Ottoman Sultan Selim I, two brothers, Aruj and Khair ad-Din, took control of Algiers in 1516. The pair had originally operated as privateers for the Berber Hafsid dynasty off what is now Tunisia. Aruj was killed in 1518, but Khair ad-Din, known to Europeans as “Barbarossa,” or “Red Beard,” succeeded him as military commander of Algiers. Khair ad-Din subsequently secured an agreement with the sultan, whereby, in exchange for their assistance in fighting Spanish invasions, Khair ad-Din would acknowledge Ottoman authority in the lands he conquered. In 1519, however, before the Ottoman troops arrived, the Spanish occupied Algiers, and it would be another ten years before Khair ad-Din successfully forced them out of the city. With Turkish troops and artillery supplied by the sultan, Khair ad-Din subdued the North African coast between Constantine in the east and Oran in the west (both in modern-day Algeria) and was named the area’s provincial governor. Algiers became the center of Ottoman authority in the Maghreb during Khair ad-Din’s regency.6

The Ottoman Empire maintained loose control over the city and the surrounding country. New walls were built in roughly the same location as those constructed in the Arab era. The walls ran continuously for 3,100 meters (roughly 10,170 feet), enclosing the town on all sides and limiting access to five gate points (Figure 1.2.2). Within

these walls, the lower part of the city, called “the plain” (al-wata), developed into the administrative, military, and commercial quarter. In this zone were mosques, military barracks, markets, warehouses, and the grand homes of the city’s political and military leadership and of its privateers, who accumulated great wealth. The upper zone, called “the mountain” (al-gabal or al-jabal), was a residential district, which became known as the Casbah, where narrow, crooked streets cut through small, densely developed neighborhoods.7

The rural countryside beyond the city walls of Algiers was a green and fertile landscape characterized by hills, valleys, and numerous springs and streams. This landscape was enhanced with public fountains erected by the Ottomans and sophisticated irrigation systems composed of norias (a water-powered device used for lifting water from a lower elevation, such as a river, to a higher elevation, such as an aqueduct), conduits, and basins. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, the countryside was relatively densely developed with farms, fruit plantations, and the country houses and pleasure gardens of the Algerian elite. Scattered along the ridges and slopes of the Algerian heights, these country estates, known as djnâyan (or djnân in the singular), typically featured expansive gardens, as well as orchards, vegetable gardens, shaded courtyards, water features, and outbuildings. They offered their owners both an escape from the crowds, noise, and heat of the medina and an opportunity to experience and interact with nature and wildlife. These country estates usually fell into one of two categories. They were either official summer residences of the governor, known as a dey, or his senior officers, or they were private residences belonging to rich merchants or privateers. The official residences included private quarters for the officer and his family, as well as spaces in which to conduct the business of the state. Private villas were smaller than the official ones and more informal. Whether sumptuous villas or modest dwellings, most shared a similar plan centered around an interior courtyard.8

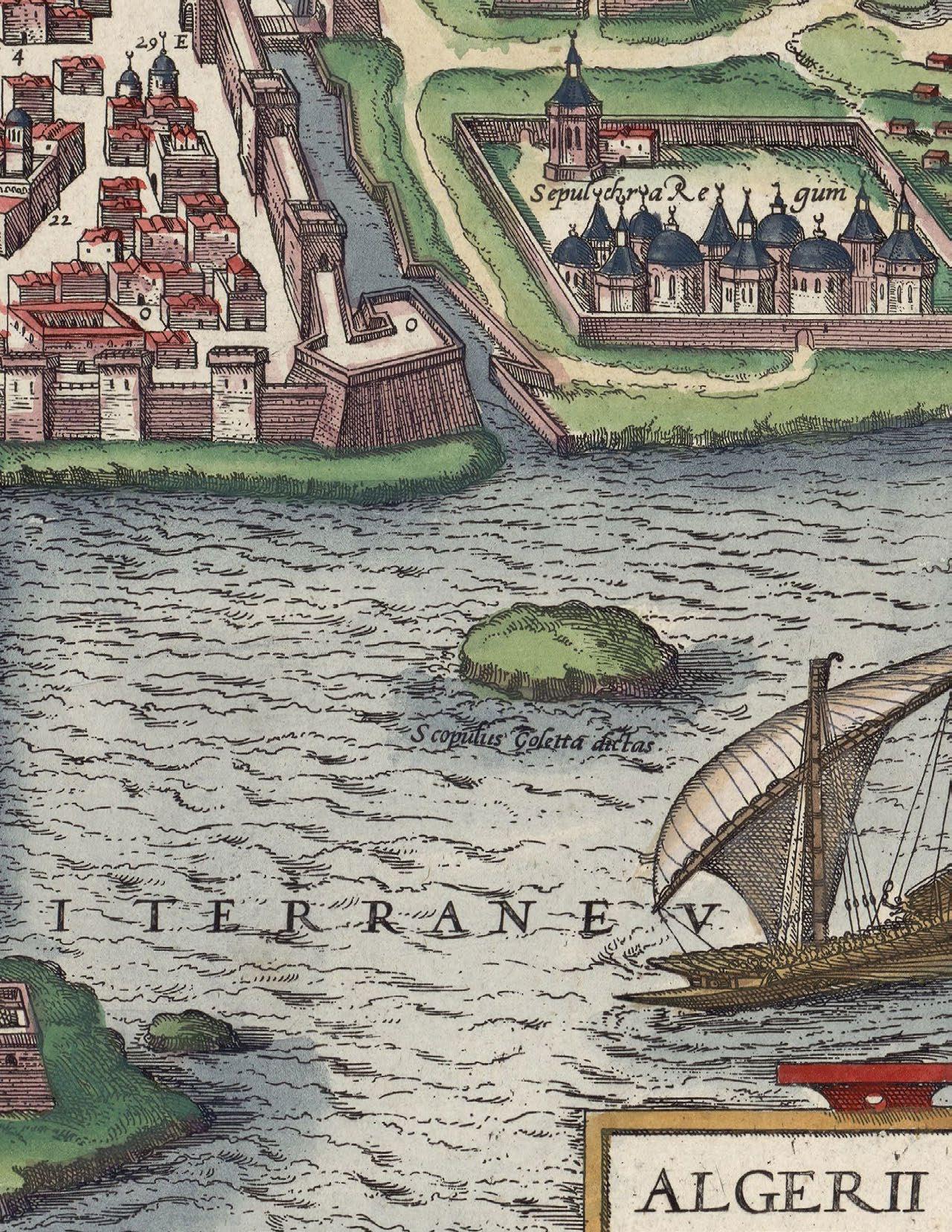

This map of Algiers was created in 1575 and published in Cologne, Germany, with the title, “View of Algiers, Seat of Power of the Saracens, in the Numidian Province of Africa and Situated on the Edge of the Balearic Current in the Mediterranean Sea, across from Spain, under the Princes of the Ottoman Empire.” It is one of the earliest printed maps of the city of Algiers. (Maps Division, Library of Congress)

French Colonization (1830–1962)

France had conducted significant trade with the port cities of the Maghreb since the thirteenth century, importing leather and skins, beeswax, cumin, sugar, dried figs, and fleece from across the Mediterranean. Over time, the French established commercial enterprises in Algeria run by French merchants. Although the French monarchy had been restored after Napoleon’s defeat, it remained unpopular and vulnerable to attack by other nations interested in colonization. To strengthen its own authority, the French government envisioned Algeria as a colony capable of absorbing the men and women in France made idle, and therefore susceptible to revolutionary ideas, by the poor economy. Colonists would produce raw materials to ship to France for conversion to finished goods for domestic and international markets. At the same time, the decline in privateering in the early nineteenth century led to a loss of the wealth the Regency of Algiers needed for defense, as did Ottoman defeats elsewhere in Europe. North Africa was therefore vulnerable.9

France used the occasion of a perceived insult to its consul by the dey as justification to blockade Algiers’ port in 1827. The blockade lasted three years but did not force Ottoman submission; the French then invaded, landing west of the city in June 1830. They captured the city in three weeks, and Hussein Dey, the last dey of Algiers, fled. The French did little to endear themselves to the Algerians during the invasion and later subjugation of the city. Thirty thousand people were either killed or exiled in the first year of the war, and thousands of properties were confiscated. In 1834, France annexed the parts of the country it occupied. Settlers from southern Italy, Spain, and France, called colons (colonists) or, more popularly, pied noirs (black feet), poured in.10

When France invaded Algeria in 1830 they encountered a dense, fortified city with monuments, public buildings, and a street network, developed over centuries, which they

found bewildering and irrational.11 Early French interventions were aimed at taking over the headquarters of the Ottoman military forces, appropriating a range of strategically significant buildings, including the palaces of local families, and clearing the urban fabric to create the spaces needed for the movement of the troops.12 Initially, these interventions were concentrated in the lower part of the city along the seafront, which came to be known as the quartier de la Marine (Marine Quarter), where military engineers were especially concerned about housing troops and cutting new arteries through the city to enable rapid maneuvers. French authorities confiscated houses, shops, and religious buildings for the purposes clearing a place d’armes, constructing new buildings, and opening streets.13 French colonizers also transformed the hills of the Sahel, where country estates were subjected to forced sales or expropriations.14 “Many officers and officials, immediately after the conquest, bought the finest gardens for a mere trifle in the communities of Mustapha and of Bujarea. The Turks were banished, the Moors began to emigrate, and both classes sold their property, parting with the most magnificent villas and farms at any price,” wrote one historian of the French invasion.15 Often, valuable materials (wood, iron, glazed tiles, marble columns) were stripped from these estates and sold, leaving many properties in ruins.

Later, as French planners began the work of redesigning Algiers to French tastes and to house the new Europeans arriving in the city, the redevelopment of the Casbah, the old residential district of the upper city, proved to be a formidable challenge. High population densities made relocation particularly difficult, and the topography and concentration of densely packed old buildings made new construction and the cutting of new streets difficult without large-scale demolition. In addition, a romantic/ Orientalist appreciation of the aesthetic values of the buildings of the Casbah inspired an interest in preserving them. French poet and novelist Théophile Gautier commented in 1845 that the Casbah ought to be preserved and that the Europeans should limited

9. Mahfoud Bennoune, The Making of Contemporary Algeria, 1830-1987: Colonial Upheavals and Post-Independence Development (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 28-35; Metz, Algeria, a Country Study, 21.

10. Metz, Algeria, a Country Study, 21-24; Bennoune, The Making of Contemporary Algeria, 1830-1987, 36-39.

11. Çelik, Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations, 19; Henry S. Grabar, “Reclaiming the City: Changing Urban Meaning in Algiers after 1962,” Cultural Geographies 21, no. 3 (July 2014), 392.

12. Zeynep Celik, Empire, Architecture, and the City: French-Ottoman Encounters, 1830-1914 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008), 72.

13. Çelik, Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations, 27; Celik, Empire, Architecture, and the City, 72.

14. Zaki Bouzid, Algérie Palais et Somptueuses Demeures (Alger: Zaki Bouzid Editions, 2014), 27.

15. Francis Pulszky, The Tricolor on the Atlas; Algeria and the French Conquest (London: T. Nelson and Sons, 1854), 43.

16. Çelik, Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations, 26.

themselves to the lower part of the historic city, closer to the harbor.16 In 1865, Napoleon III called a halt to the éventrement (gutting) of the Casbah (Figure 1.2.3). Its preservation was viewed as a way to safeguard regional culture and to attract tourists.17

While colonists arrived Algiers looking for economic opportunity in the city and on agricultural properties, by the middle of the nineteenth century many Europeans and some Americans came as visitors, attracted to the city’s temperate weather and perceived exoticism. The earliest came for health reasons rather than tourism. Encouraged by doctors who extolled the curative properties of a warm, sunny climate, patients with pulmonary ailments took extended stays during the winter season, which lasted from October to May. Some visitors found lodging in hotels or rented houses. Those with enough wealth bought country estates in the fohôs, a term used to describe the peripheral zones of Algiers, where they built houses or renovated existing villas.18 English guidebooks, medical texts, and travelogues promoted travel to Algiers, encouraging tourism. The trip for a British visitor required a train from London through Paris to Marseilles, then a steamship to Algiers. Later, direct steamer service operated from Liverpool and London.19

A popular destination for wealthy British and Americans was the neighborhood of Mustapha Supérieur. After a visit in 1857, one English visitor to Algiers wrote: “To those who desire a permanent dwelling-house, and who intend to keep what is called a regular establishment, no situation could be more delightful, nor more desirable that than of upper Mustapha.”20 Another travel writer in 1895 described the neighborhood as “well situated on the slopes of the hills south of Algiers amongst gardens and pine woods…being at a considerable elevation above the sea, it has the great advantage of being fresher and more healthy than the town.”21 The first hotels in Mustapha Supérieur opened in the late 1880s, catering to visitors who did not take villas. J. Hildenrbrand, proprietor of the Hotel d’Orient and Hotel Continental, boasted that his

establishments offered magnificent views, lawn tennis, and “telephone to Algiers.” Moreover, he provided guests with omnibus service upon their steamship arrival.22 The seasonal visitors and residents of Mustapha Supérieur and the adjacent neighborhood of El-Biar formed a compartmentalized society. The British, for example, founded an Anglican church, a hospital, social clubs, and weekly newspapers. Although the golden age of AngloAmerican migrations to Algiers peaked in the last third of the nineteenth century, the city remained a popular destination until the eve of World War I.23

Mustapha Supérieur was incorporated into the city of Algiers in 1904, and, gradually, the built fabric of city climbed far onto the surrounding hills. Over time, the nineteenth-century pattern of Moorish-style villas in gardens on the heights was replaced by much denser settlement patterns where the “buildings of modern Algiers” crowded out “the cubic houses of the Arab city.”24 The increased urbanization of Mustapha Supérieur prompted many American and European owners to sell their estates to French colons 25 Following World War I, Algiers experienced a decline in its popularity as a winter retreat. The opening of trans-Mediterranean air travel in 1931 made short stays easier and decreased the need for season-long visits. The worldwide Depression of the 1930s essentially ended the seasonal gatherings of wealthy Europeans and Americans in Algiers.

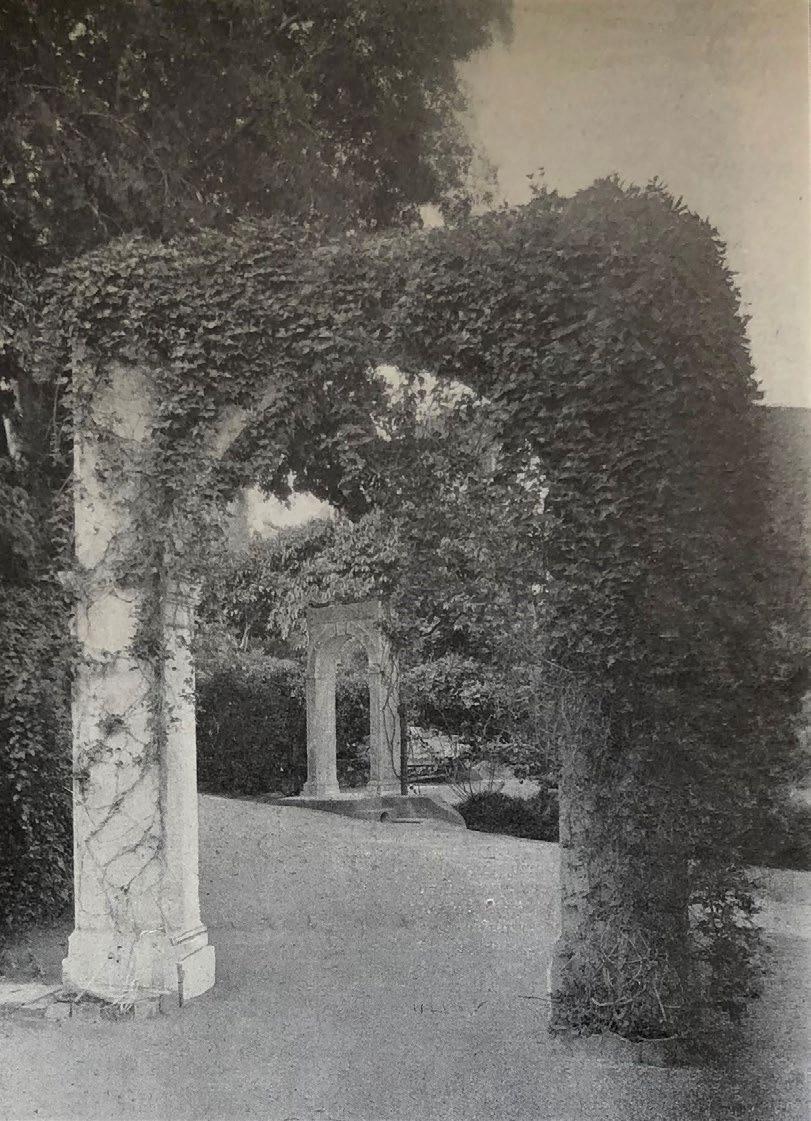

A nascent preservation movement emerged in the early twentieth century in response to the city’s rapid urbanization. In 1905, Henri Klein founded the Old Algiers Committee (Comité du Vieil Alger), which served as the movement’s leading voice. Klein and his associates documented the city’s historic buildings and monuments in the periodical Feuillets d’El-Djezair and organized tours of Ottoman djnâyan (Figure 1.2.4). Journals and magazines such as L’Afrique du Nord Illustrée also published stories highlighting notable historic villas and gardens (Figures 1.2.5 and 1.2.6). The first urban planning law in France, known as the Cornudet Law (1919, revised

17. Michelle Lamprakos, “The Idea of the History City,” Change Over Time 4, No. 1 (Spring 2014), 18.

18. Bouzid, Algérie Palais et Somptueuses Demeures, 25.

19. Liz Davenport, Woodchester, A Gothic Vision (Gloucestershire, England, 2014), Chapter 12.

20. Rev. E. W. L. Davies, Algiers in 1857 (London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, & Roberts, 1858), 52.

21. R. Lambert Playfair, Handbook for Travellers in Algeria and Tunis (London: John Murray, 1895), 106.

22. Handbook Advertiser, 1893-1894, in R. Lambert Playfair, Handbook for Travellers in Algeria and Tunis (London: John Murray, 1891), 5.

23. Osman Benchérif, The British in Algiers, 1585-2000 (Algiers: RSM Communication, 2001), 42.

24. “Jardins D’Alger,” L’Afrique du Nord Illustrée, Nouvelle série, no. 130 (October 1923), 5, translated by S. Chergui.

25. Christopher Ross “American Embassy Properties in Algiers: Their Origins and History” (typescript), April 1991, US Department of State, Office of Overseas Buildings Operations, 10.

1.2. Historical Background & Context / CMR (cont’d)

1.2. Historical Background & Context / CMR (cont’d)

in 1924) became applicable in Algeria with minor modifications by decree on January 5, 1922. The law created “zones of architectural protection” in the areas near historic monuments and proposed that French cities over a certain size submit a “plan for development, extension and embellishment.” The urban development plan for Algiers was approved in 1929, which divided the territory of the city of Algiers into four zones with different development limits and introduced planning tools such as no-building zones (zone non-aedificandi). Mustapha Supérieur was located Zone C, a residential district where gardens and trees were to be protected (Figure 1.2.7).

After World War II, Islamic immigration to Algiers increased substantially, putting pressure on the historic city. Bidonvilles squatters’ communities named for the gas barrels used to build walls for shelter proliferated, and overcrowding in the Casbah created extremely congested conditions. In 1957, General Charles de Gaulle unveiled a new development plan for Algeria which aimed to improve, among other things, housing deficiencies and congestion, but the administration never took action to address the issues facing residents of the Casbah. During Algeria’s war for independence, the area became a frequent site of urban guerrilla warfare.26 The effect on the heights of Algiers over time was to make the area more urban than rural in character.

Algerian Independence (1962–Present)

One of the immediate goals of Algerian leadership following independence was “to liquidate, in all its forms, colonialism as it manifests itself.”27 Across the country, streets and squares were renamed, and French statues and monuments were taken down. Soon after taking power, Algeria’s strongly centralized government instituted Ordinance 66-102, which gave it the authority to appropriate “bien vacants” properties deemed to be abandoned by their owners. Titles to these properties passed to the state, yet conflict over the issue persisted for years. As a result of the abrupt departure of French

colons in 1962 and 1963 (about one million French left within a period of seven or eight months), the city of Algiers experienced a rapid and destabilizing population transfer. Since the French had maintained control of many sectors of the municipal government, Algiers was left with a vacuum in administrative expertise and experience. At the same time, many rural residents flowed into the city seeking employment, resulting in a continuous increase in the urban population. While the primary character of the Sahel did not immediately change, green space within the city did disappear as parks and public gardens were developed for new housing.28 Despite government attempts at urban planning to account growth in the recent past, political upheavals, economic problems, and social changes have negated the impact. The suburbs have grown erratically and sometimes illegally, with a resulting loss of parkland and haphazard development in the hills surrounding the old city.29

For decades following independence, efforts to break away from its colonial past defined Algerian national identity. The classification of new monuments for safeguarding overwhelmingly prioritized archaeological sites from prehistory and antiquity. In the 1990s, however, government officials took important steps toward recognizing and protecting a broader array country’s cultural heritage, including heritage attached to the Ottoman and French presence. The Casbah was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1992, and in 1998, the president passed a new law (Law 98-04) that established regulations for identifying and registering historic sites and defining the rules for their protection. Since that time, conservation efforts have expanded to better reflect the extent and richness of the country’s national historic heritage.30

26. Çelik, Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations, 45-46.

27. Grabar, “Reclaiming the City: Changing Urban Meaning in Algiers after 1962,” 391.

28. Ibid. 398.

29. Çelik, Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations, 79-80; Azzeddine Bellout, “Monitoring Settlements Growth and Development in Algiers City Eastern Area,” February 17, 2021, Research Square website, https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-187885/v1; Edward Karabenick, “A Postcolonial Rural Landscape: The Algiers Sahel,” Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers 53 (1991), 98-99.

30. Abdeloushed Oukebdane, et al., “A Critical Review on the Classification Process of Historical Monuments in Algeria,” Conservation Science in Cultural Heritage 21, no. 1 (2021), 149-166.

1.2. Historical Background & Context / CMR (cont’d)

RESIDENTIAL ARCHITECTURE OF ALGIERS

Islamic Heritage

Islamic architecture refers to the built heritage “made by or for people who lived under rulers who professed the faith of Islam or in social and cultural entities which, whether themselves Muslim or not, have been strongly influenced by the modes of life and thought characteristic of Islam.”31 Faced with the complex interplay of theological, sociological, economic, political, and technological factors that this heritage represents, historian Ernst Grube has identified a list of key qualities that sets Islamic architecture apart. The first, he writes, is its inward-oriented focus. While the most common expression of this quality is the Muslim house, which is organized around an interior courtyard and often presents a windowless wall to the outside world, it also translates to public and religious buildings. The second key quality is the absence of a specific architectural form for a specific function. In other words, he writes, “an Islamic building does not automatically reveal, by its form, the function it serves.”32 The third quality is the emphasis on decorative expression of interior spaces. Decorative treatments, with the exception of the dome and entrance portal, are reserved for the interior, and exterior articulation is minimal. Grube theorizes that the principal purpose of Islamic decoration is to dissolve or negate all elements that emphasize or express the structure — the walls, the vaults, the columns to focus attention on space. Another important characteristic of Islamic architecture is its organic quality. Buildings rarely have a balanced plan or axial arrangement, and additions are never bound by symmetry or an inherent directionality.

Islamic architecture uses of a multitude of decorative treatments (mosaics, stone, stucco, tiles, painted polychrome) and a rich selection of designs, with the main elements being epigraphic, geometric, and foliated. On interior and, less frequently, exterior surfaces, decoration is typically controlled by primary and

secondary grids, which create rectangular or square panels. Another organizational unit is the mihrāb motif an arched niche, either deeply recessed or shallow, contained in a rectangular frame. Epigraphic decoration might use cursive or kufic script, a style of Arabic script preferred for architectural decoration. Foliation might be realistic or stylized into intricate patterns as part of arabesque decoration. The star, whether six points, eight, sixteen or more, is a fundamental shape in Islamic geometric design, and intricate geometric patterns are used to cover flat as well as curved surfaces. Decorative motifs might be repeated at different scales on the same wall or used interchangeably from one medium to another, creating sumptuous and exuberant spaces. The use of perforated screens or grilles (claustra) decorated with colored glass added another dimension to these highly decorated surfaces by projecting a secondary pattern over floors and walls.33

Although Islamic architecture encompasses a broad spectrum of vernacular dwelling types, common characteristics can be identified. The Islamic house is an introverted form reflecting the emphasis on domestic privacy in Islamic culture. The courtyard house is an ancient vernacular expression of this form in which the walls of the house enclose an open courtyard, allowing for outdoor activities while offering protection from wind, dust, sun and demarcating public and private life. Entry into an Islamic house is usually indirect. The main door leads to a vestibule or passage that is connected to the domestic quarters by a right angle turn so that is it impossible to see inside from outside. Interior rooms are not allotted to a specific activity, but rather are used interchangeably for eating, sleeping, recreation, and domestic tasks, and the use of cushions, mats, and rugs that can be easily rolled up and stored or moved reflect this flexibility. Rooms of an Islamic house often feature open niches or storage cupboards built into the walls.34

The urban houses found in the Casbah of Algiers embody many of these traits. Dwellings are highly interiorized,

reflecting the importance of family privacy and gender separation. The typical urban house does not have many exterior windows, relying instead on a central courtyard for light and ventilation. Houses share a similar plan whether they are modest or palatial. The entry hall, or sqîfa, creates a bent axis that kept the interior of the house out of view. Benches (doukana) embedded in the side walls of the sqîfa give visitors a place to rest while awaiting entry. The courtyard, or wast al-dār, is the heart of the home. It is located as centrally as possible on the lot, open to the sky, and typically surrounded by arcades on the ground floor and upper level. The rooms surrounding the courtyard are rectangular, and, if they face the street, an alcove (k’bou) might be built into the wall facing the door. This is materialized on the exterior wall by a corbel, sometimes supported with wood struts (Figure 1.2.8). In large houses, the alcove might be replaced by an ancillary space (iwān) topped with a cupola, creating a T-shaped room. The open courtyard facilitates the movement of air through the house, and its proportions create a microclimate that was reinforced by use of plants and water features, such as a fountain (Figures 1.2.9 through and 1.2.11). Galleries surrounding the courtyard opening provide shade and prevent the sun from hitting internal walls (Figure 1.2.12). Large doors around the courtyard are mounted so that they can be opened flat against the wall, maximizing ventilation. Each leaf contains a smaller door, used when the house is to kept warm. The courtyard also functions as a hybrid indoor/outdoor gathering space that affords members of the household tranquility, safety, and privacy from the urban environment. Roof terraces are another standard element of the Algerian house. Richly decorated interiors contrast strongly with the austere exteriors. Frequently, exterior ornament is limited to door openings, which might feature elaborate, carved stone surrounds.35

Algerian Djnâyan

As discussed previously, during the Ottoman period, the Algerian elite built country houses, known as djnâyan, along the ridges and slopes of the Sahel. These houses

resembled, in plan, the urban houses of the Casbah, but the availability of space made it possible to extend the dwelling into the landscape with ancillary rooms, large exterior courtyards that were either walled or surrounded by covered arcades, and terraces that extended down the hillsides. In addition to the main house, these rural estates might include a guest house (douèra), freestanding pavilions for enjoying the outdoors (riyādh), a guardhouse at the entrance to the property, or other outbuildings.

Like urban houses, the main residence (dâr) of a country estate was organized around a central courtyard surrounded by arcaded galleries. In the summer months, the courtyard, or wast al-dār, functioned to keep the house cool and well ventilated. During the day, the galleries facing the courtyard shaded the interior walls, protecting them from direct sun. At the same time, the open construction of the courtyard encouraged the movement of air. Small openings in the upper walls of the interior rooms, often fitted with decorative grilles or claustra, helping keep the house cool by allowing for the natural ventilation of warm air. At night, the courtyard allowed cool air to enter the house, and doors facing the courtyard could be fully opened to encourage the ventilation of adjacent rooms. During the winter months, the high thermal capacity of the house’s thick masonry walls helped keep it warm. In contrast with the urban house form, the floor plan of a country house would frequently incorporate iwān, small ancillary rooms off the main rooms that were covered with octagonal domes. Windows in the iwān caught prevailing winds in the summer, and small openings in the dome allowed for the release of warm air. Since these were freestanding houses, there were a greater number of window openings and both windows and doors were larger than those in the city.36 The window openings featured wrought-iron grilles. An example of such a property is the Villa Abd-el-Tif (Figures 1.2.13 through 1.2.15). Constructed in the middle of the seventeenth century in a wooded area on the hillside, it exemplifies the features of the Ottoman period djnân

1.2. Historical Background & Context / CMR (cont’d)

The seventeenth-century Villa Abd-el-Tif possesses all the features of a typical djnân, including a principal residence and other buildings enclosing a courtyard, a riyādh, or gallery, water features, a well, and a guest house. (Adli-Chebaiki and Chabbi-Chemrouk, “Vernacular Housing in Algiers”)

The open courtyard (here spelled west-ed dar) of the Villa Abd-el-Tif helped ventilate the rooms around it. (Adli-Chebaiki and Chabbi-Chemrouk, “Vernacular Housing in Algiers)

1.2. Historical Background & Context / CMR (cont’d)

In terms of construction, these houses were load-bearing, brick masonry structures laid with lime-based mortar. Foundations might incorporate rubble stone into the walls for extra stability. The thermal mass of masonry construction minimized temperature extremes within the house, and limewash coatings on the exterior walls and roofs reflected solar radiation. Ceilings and floors were vaulted or post-and-beam construction with wood beams and joists set directly into thick walls. Arches on columns were used to support long spans of large interior spaces. Roofs were predominately flat with low parapets that functioned as railings. Exterior walls integrated two types of conduits flues for the evacuation of smoke from oil lamps and pipe drains for channeling rainwater from roof terraces to underground reservoirs. As water passed through the internal conduits, it cooled the rooms. Some houses incorporated small, domed spaces. The most commonly used dome form was a ribbed, hemispheric dome with eight panels assembled on an octagonal base. The base of the domes featured horizontal belts made up of chains of logs. On February 3, 1716, Algiers was rocked by a devastating earthquake that destroyed many homes, palaces, and mosques. The earthquake resistant construction techniques that emerged after the earthquake included inserting wood logs as longitudinal ties within masonry walls and rows of logs at the base of arches to absorb rotational movements (Figure 1.2.16).37

Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century travelogues and memoires written about Algiers are full of evocative descriptions of the djnâyan that graced the hills of the Sahel. Eugène Fromentin, a French painter and writer, who published, in 1857, a travel diary of his visits to Algeria in the 1840s and 1850s, wrote about the landscape fringing the city and the houses he observed there. On a visit in December 1852, he observed: “I ended my day among the trees, looking at Turkish houses. There is a whole part of the hills where these elegant buildings are in great number. They can be seen here and there over the foliage, at a very small distance from each other, and so well surrounded that each of them seems to have its own park. They are all

L.

1.2. Historical Background & Context / CMR (cont’d)

built in a picturesque situation, on an echelon of wooded slopes, and all of them look out over the sea. As you stand on this vast amphitheatre, regularly arranged in terraces, you can imagine the beautiful and great view enjoyed by the inhabitants of these beautiful residences.”38

Moorish Revival Style in Algiers

The large influx of European and American visitors to areas like Mustapha Supérieur and el-Biar beginning in the mid-nineteenth century and continuing through the early twentieth contributed to its urbanization and altered the character of its residential architecture. While some hivernants (winterers) valued the authenticity of and were content living in Ottoman-period dwellings, many others saw fit to renovate existing buildings or build new houses, bringing their own ideas about architecture to the Sahel. This especially affected the internal layout of houses. Whereas in a typical Islamic house, the primary space and “heart” of the dwelling was the interior courtyard, European sensibilities introduced large, carefully appointed spaces that were given equal importance in the floor plan and were assigned specific functions.

Continental and North American visitors, however, were often deeply affected by the exotic aspects of the existing architecture and landscape and saw no reason to replace its decorative motifs with imitations of the buildings of their homeland. This interest in and appreciation of the art, architecture, language, and history of what was broadly defined as “the East” meaning Asia and the Middle East, but also North Africa is often subsumed into an art, literature, and cultural category known as Orientalism. During the nineteenth century, painters from many nations came to Algiers to record their impressions of the exotic people, costumes, and customs of the locals. In his book Orientalism, Edward Said, a PalestinianAmerican professor at Columbia University, saw in the romanticizing of “the East” a persistent prejudice that helped justify colonizing its people.39

In architecture, “homage” to native buildings could take the form of restoring existing Ottoman-period djnâyan or creating new Moorish Revival designs using the forms of the Algerian villa. The Moorish Revival (or Neo-Moorish) style was one of many revival styles adopted by architects of Europe and the Americas in the nineteenth century that reflected a growing interest in medieval architecture together with a rejection of Neoclassicism. It reached the height of its popularity in Europe after the mid-nineteenth century and was strongly linked to the decorative arts and a flourishing academic interest in the art and architecture of Andalusia. Welsh architect Owen Jones was one of the most influential design theorists of the nineteenth century. Working with French architect Jules Goury, Jones spent months studying and meticulously documenting the Alhambra outside the city of Granada, Spain, one of the most influential examples of Moorish architecture. He published his research in a highly influential book titled Plans, Elevations, Sections and Details of the Alhambra (Figure 1.2.17), which helped stimulate wide interest in Islamic architecture. His 1856 book The Grammar of Ornament also became a seminal design sourcebook for architects interested in NeoMoorish and other revival styles.

To imbue these colonial-era residences (and their associated gardens) with authenticity, architects and builders salvaged original materials and features from buildings in the Casbah and elsewhere to reuse in the new construction. New construction might feature elegant tile panels made in the Qallālīn workshops of Tunis, which featured distinctive green, blue, and yellow pigments. Carved stone courtyard columns and carved stone door surrounds, often featuring crescent moon, floral, and six-pointed or eight-pointed star motifs, were reused in courtyard arcades and at door openings. Interior wood doors featuring elaborate geometric panels known as qâyam-nâyam were retrofitted in new openings, or their design reproduced for niche cupboards. Reclaimed wall and floor tiles were also used to decorate the interior surfaces of European and American homes.

38. Eugène Fromentin, Une année dans le Sahel (Paris, M. Lévy frères, 1859), 89-90, translated by S. Chergui.

39. M.C. Thomas, “Orientalism,” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/science/Orientalism-cultural-field-of-study, accessed January 9, 2023; John MacKenzie, Orientalism: History, Theory and the Arts (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995), 62-67.

The architects of Moorish Revival buildings in Algiers, and especially in the Sahel, were likely to have been trained in Europe, given French command over such positions in Algeria at this time. Builders, artisans, and contractors were likely to be colons as well. The British architect Benjamin Bucknall, who settled in Algiers in the fall of 1878, was a practitioner of the Moorish Revival style and developed a client base in the Sahel. A colleague of and collaborator with Bucknall was the Algerian contractor Barthélémy Vidal. (See text below for additional information on Bucknall and Vidal.)

One important distinction between Ottoman and French colonial construction was structural. One of the construction methods in common use in new buildings erected during this period was known as plancher à voûtains vaulted floors. The technique employed iron or steel “I” beams as floor joists connected with low vaults of solid or hollow bricks which landed on the flat surface of the beams. Floors were laid on top of the vaults and, since the technique was not employed in traditional Algerian architecture, a flat ceiling was often applied to the underside to hide the modern method. This means of constructing floors had begun to be used widely in France in the middle of the nineteenth century to exploit the potential new methods of producing iron and steel. It continued to be used in France until World War II.40 While the precise dating of its use in Algeria is not known, it is assumed that it was introduced not long after it began to be used across the Mediterranean and continued for the same period of time. It is referred to by current architectural historians and preservation specialists in Algeria as “French construction.”

RESIDENTIAL GARDENS AND LANDSCAPES OF ALGIERS

Elements of Islamic Gardens

In the history of Islamic landscapes, the archetypal formal garden plan is the so-called chahar bagh, a four-part garden laid out with axial walkways that intersect at the garden center. In early examples of this highly structured geometric scheme, the quadrants took the form of shallow expanses of turf for sitting or were sunken below pavement level and planted with a careful arrangement of flowers or shrubs to produce a colorful “carpet” effect when seen from above. Water channels, or runnels, and fountains, arranged symmetrically or axially within the four-part form, were a key element of the garden. They served the practical purpose of irrigation and added to its sensory experience (Figure 1.2.18). Another typical water element was the chadar, a stone or marble chute, sometimes with a textured surface, used to create a gentle cascade. The quadripartite plan of the Court of the Lions in the Alhambra, which dates to the Nasrid period (1232-1492) demonstrates the form. It features a central fountain, in this case composed of a large basin resting on the backs of twelve lions, and axial runnels that intersect at the fountain to create a four-part arrangement (Figure 1.2.19). According to landscape historian Dede Fairchild Ruggles, while the chahar bagh is typical, it should not be considered ubiquitous. Variations of the four-part plan might include a single, long rectangular bed with a central watercourse, a paved courtyard with a fountain, a sunken basin surrounded by potted plants, or multiple beds aligned on terraces carved into a sloping hillside.41 The Court of the Myrtles at the Alhambra, for example, is a courtyard garden with a large, rectangular central pool that receives its water from fountains at either end. It also dates to the Nasrid period.

The earliest surviving Islamic gardens, which date to the seventh to the mid-tenth century, were enclosed by walls. Trellises were used to create “living walls” and provided a

structure for the display of flowers or fruit. Another typical feature was an outdoor seating pavilion, or riyādh, which provided a place to relax and offered shelter from the elements. In palace gardens, the pavilion might be placed in the center of the chahar bagh, as an expression of power. The fluid relationship between architecture and landscape, with structures such as arcaded porches forming an integrating element, was another important design consideration.42

Gardens of the Islamic world were made to appeal to the senses. Fragrant flowers, fruits, or herbaceous borders perfumed the air. A trickling fountain, rustling branches, and the presence of birds animated the garden with sounds. The smooth feel of tile or marble surfaces appealed to the sense of touch, as did the feel of running water. Fruit trees rewarded one’s sense of taste and smell, and everywhere sight was rewarded with contrasting colors, the interplay of light and shade, and reflections on water. The Muslim conception of paradise is a perfect garden where the faithful dwell in eternity. Ruggles argues, however, that a garden divided into four parts does not reflect a specifically Muslim conception of paradise. Rather, the description of paradise in the Qu’ran reflects a pre-existing garden form and vocabulary.43

Ottoman gardens were more sensitive to the natural topography of their sites and generally did not impose an artificial grid on the landscape.44 An unusual example of the chahar bagh plan in an Ottoman garden was built in the early sixteenth century near the Topkapı Palace in Istanbul. Known as the Karabali Garden, it featured intersecting axial paths broad enough for the passage of three horses and was entirely surrounded by a double row of cypress trees that formed an oval around the garden quadrants (Figure 1.2.20). The Ottoman-era djnâyan built on the foothills surrounding Algiers were often sprawling estates with extensive gardens watered by a multitude of springs. Located high above sea level, the gardens provided a healthy retreat, a place of refuge, and captivating views. They also served as a demonstration of

the wealth and status of their owners. Characteristic elements included courtyards, terraces, pavilions, trellises, and ornamental water features, as well as orchards and vegetable gardens. Irrigation systems might include wells, waterwheels (or noria), aqueducts, irrigation canals, ponds, and cisterns. These properties were unfenced; instead, boundaries were marked by hedges of myrtle, hawthorn, aloe, or Barbary figs (prickly pear).45

In her book Six Years Residence in Algiers, Elizabeth Broughton, daughter of Henry Blanckley, who served as British consul general to Algiers starting in 1806, recounted her childhood spent in Algeria. In her memoir, she writes about the courtyard of their country house, and one can discern in her description the underlying influence of Islamic gardens and identify key features characterizing the gardens of Ottoman djnâyan. “On one side of the courtyard,” she writes, “was a very pretty little garden in which grew five very tall orange trees giving the best fruit in the country, both for its size and its remarkable taste. Just before leaving, we had planted banana trees there, next to a channel formed by the water that overflowed from a large marble fountain.” She continues, “Along the three sides of the courtyard, there were flowerbeds maintained by low brick walls three to four feet high, which as well as those surrounding the courtyard, were whitewashed.” She also describes a trellis “that supported the branches of a magnificent vine, which took root in the flowerbeds.”46 Broughton also provides a description of the road that led to their country house: “The road…was bordered on both sides by high and thick hedges, impenetrable to both men and animals. They were double: there was a first row of plants called prickly pears and a second of aloes, whose giant flowers could not exceed their beauty in the landscape. On the other side of these enclosures, there were vast fields of wheat and barley.”47

42. D. Fairchild Ruggles, Islamic Gardens and Landscapes (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 42, 44.

43. Ibid., 89.

44. Ibid., 50.

45. Chabbi-Chemrouk and Hocine, “Reuse of Djenane Abd-el-Tif, An Emblematic Islamic Garden in Algiers,” 135.

46. Alain Blondy, Six ans de résidence à Alger Par Mrs. Broughton (Editions Bouchène, 2011), 214-15, translated by S. Chergui.

47. Ibid., 212, translated by S. Chergui.

In November 1852, while staying in Mustapha Supérieur neighborhood, the French artist and writer Eugène Fromentin described the garden of his house, writing, “I almost have two gardens. One is small, enclosed by walls, planted with roses, orange trees, rubber trees, and high foliage trees that will lend me shade…My second garden is, strictly speaking, only a parterre enclosed in a meadow that recent rains have made a little green, and which is beginning to be filled with wild mallows.”48 In a separate diary entry the same year, he describes the garden’s water features, including the “hollow marble gullies, where the water meanders and draws mobile arabesques” and a “vast cistern where the water is no more than a meter high, paved with the finest white marble and opened by arches over an empty horizon.”49 He also provides a vivid description of the djnâyan scattered across the hillsides. “There is a whole part of the hills where these elegant buildings are in great number. They can be seen here and there over the foliage, at a very small distance from each other, and so well surrounded that each of them seems to have its own park. They are all built in a picturesque situation, on an echelon of wooded slopes, and all of them look out over the sea. As you stand on this vast amphitheater, regularly arranged in terraces, you can imagine the beautiful and great view enjoyed by the inhabitants of these beautiful residences,” he writes.50

The Djnân Abd-el-Tif, located in Bab Azzoun on the outskirts of Algiers, is considered one of the best remaining examples of the city’s Ottoman-era country houses and one in which the Islamic-style garden has survived. Built sometime before 1715, the buildings and structures that comprised the estate, which included the main house, a guest house (douèra), and several ancillary buildings, were all organized around and oriented toward the garden, which features fountains, an ornamental pond, and terraces (Figure 1.2.21).51

European Trends and Influences

During the last decades of the Victorian period in England, the cottage garden became the model for gardeners who rejected the formality of the Gardenesque, an early nineteenth-century style championed by botanist and garden designer John Claudius Loudon and characterized by displayed plants, exotics, and elaborate parterres. In the tradition of the Picturesque, the cottage garden “began with a premise in which a delight of the natural sets the scene,” and featured compositions of plants that were intermingled and sometimes intertwined, as in the wild.52 The practitioner most associated with the English cottage garden style was William Robinson, an Irish gardener and journalist, whose seminal work, The English Flower Garden, published in 1883, attracted a wide readership and ran to sixteen editions. Often associated with the Arts and Crafts movement, Robinson’s cottage garden style promoted rock gardens, wild gardening, herbaceous borders, and naturalistic effects. A frequent collaborator of Robinson’s was Gertrude Jekyll, the garden designer and artist who built a successful design practice with the architect Edwin Lutyens.53 Jekyll was known for her painterly approach to garden design, creating schemes that favored shapes, textures, and broad masses of color. She wrote several books, was the author of the chapter on color in Robinson’s The English Flower Garden, and became a contributor to Country Life magazine in 1901.

Concurrent with the development of the English cottage garden style was a resurgence of interest in Italianate gardens, with their broad terraces, staircases with balusters, and urn-shaped finals, and in ornamental French parterre de broderie. Yet another important source of influence on garden design in the late Victorian period was Reginald Bloomfield, an architect by training, who advocated for a return to design formality in the English garden. “To suppose that love of nature is shown by trying to produce the effects of wild nature on a small scale in a garden is clearly absurd,” he wrote.54

48. Fromentin, Une année dans le Sahel, 13-14, translated by S. Chergui.

49. Ibid., 91, translated by S. Chergui.

50. Ibid., 77-79, translated by S. Chergui.

51. Chabbi-Chemrouk and Hocine, “Reuse of Djenane Abd-el-Tif, An Emblematic Islamic Garden in Algiers,” 136.

52. Elizabeth Barlow Rogers, Landscape: A Cultural and Architectural History (New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001), 378; Monique Mosser and Georves Teyssot, eds., The History of Garden Design: The Western Tradition from the Renaissance to the Present Day (London, Thames & Hudson, 1991), 424-25.

53. Lutyens designed the British Ambassador’s Residence in Washington, D.C.

54. Rogers, Landscape: A Cultural and Architectural History, 379-383.

1.2. Historical Background & Context / CMR (cont’d)

OWNERS OF THE CHIEF OF MISSION RESIDENCE

A Period of Speculation, 1837–1862

There is scant information on the ownership history of the country estate in Mustapha Supérieur that would later become the site of the CMR until 1837, when, according to a history of US embassy properties in Algeria prepared by former Ambassador Christopher Ross, it was sold to a French citizen. Ross describes the pre-1837 owners as “various Moors and Morresses [sic],” which may be a phrase taken from legal documents of the time. He also notes that these may have been multiple heirs of one owner.56 This was during a time when French colonists were expropriating the country estates of many Ottoman elite. The property’s hillside location in the Mustapha Supérieur neighborhood also made it an attractive piece of real estate. Over the next twenty-six years, title to the property would be transferred seven more times, on each occasion to a French national. The frequency in which the property traded hands was not unusual for the period. Francis Pulszky, in his history of the early colonial period noted, “Some of these splendid residences have often changed proprietors, each of them selling it as a premium to some new-comer, as there were always speculators enough, who, in the believe that the epoch of great European immigration had arrived, disproportionally enhanced the prices…”57

British Occupants of the Villa, 1863–1932

In 1863, the English merchant Archibald Briggs purchased the property, which at the time featured a “large dwelling house” built by the previous owner on the site of an earlier “Moorish-style house.”58 Briggs was one of a wave of European and American visitors who came to Algiers in the middle of the nineteenth century for its temperate weather and exotic locale.

The Briggs family had its origins in Yorkshire, England, where it amassed a fortune in the coal mining industry

during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The family firm, Henry Briggs, Son & Co., which operated the Whitwood and Methley Junction Collieries, became a pioneer in the profit-sharing movement that developed in England in the 1860s.59 Beginning in 1865, the firm changed its corporate structure from a privately owned operation to a join stock limited liability company, making shares available to its employees and creating profit incentives. Archibald Briggs was promoted to secretary of the firm for the purpose of carrying out the experiment. His brother, Henry Currer Briggs, served as managing director until the death of their father, at which time he became chairman and Archibald resumed the responsibilities of managing director. Archibald retained the title of managing director of Henry Briggs, Son & Co. until 1876, when the health of his family obliged him to move abroad. He published an essay on the firm’s experience with the profit-sharing movement in the book Profit-Sharing between Capital and Labour, published in 1884.60

While the specific reason for Briggs’ move to Algiers in 1863 is unknown, health may have been a factor, as it was the reason for his 1876 move abroad. Briggs’ decision to sell the Algiers estate after only three years of ownership was likely due to professional and familial responsibilities related to Henry Briggs, Son & Co., of which, by that time, he was managing director.

The next owner of the property was Anna Leigh Smith (1831–1918), a British citizen who, for years prior, had made Algiers her winter home as a guest of her sister, Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, who owned an Ottomanera country house on 12 acres in the Mustapha Supérieur neighborhood.

Born in Sussex, England, in 1831, Anna Leigh Smith was one of five extra-marital children of Benjamin Leigh Smith (1783–1860), a Whig politician, and Anne Longden, a milliner. Her family history is full of remarkable and wellaccomplished men and women. Her grandfather, William Smith, was a member of Parliament and a radical

56. Ross, “American Embassy Properties in Algiers: Their Origins and History,” 16.

57. Pulszky, The Tricolor on the Atlas, 43-44.

58. Ross, “American Embassy Properties in Algiers: Their Origins and History,” 15-16.

59. Leeds University Library, Special Collections Finding Aid, “K. M. Briggs Collection, Special Collections MS 1309,” available at https://explore.library. leeds.ac.uk/multimedia/17151/157MS1309Briggs.pdf; R. A. Church, “Profit-Sharing and Labour Relations in England in the Nineteenth Century,” International Review of Social History 16, no. 1 (1971), 3.

60. Sedley Taylor, Profit-Sharing between Capital and Labour (London: Kegan Paul, Trench & Co, 1884), 131-132; Ross, “American Embassy Properties in Algiers: Their Origins and History,” 16.

Historical Background & Context / CMR (cont’d)

abolitionist. Florence Nightingale was her cousin. Her father, a politician and philanthropist with radical views, sent all of his children to local schools, despite being a member of the landed gentry, and gave each an annual income of equal share when they reached adulthood rather than favoring his male progeny. One of her brothers, Benjamin Smith (1828–1913), was an Arctic explorer, but the most well-known member of her immediate family was her sister, Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (1827–1891), a renowned nineteenth-century feminist, women’s rights advocate, publisher, and founder of Girton College, Cambridge. Barbara made her first trip to Algiers in 1856, where she met Eugène Bodichon, a French physician, whom she married the following year (Figure 1.2.22). For many years Barbara divided her time between Britain and Algiers.61

Anna Leigh Smith, known to her friends and family as Annie or Nannie, was described as “a woman of stern intellectual vigor and an unwavering kindness.”62 In December 1856, Anna and her sister were visited in Algiers by George MacDonald, the Scottish author, poet, and minister, who described the pair as “rather fast, devil-may-care sort of girls…not altogether to our taste, but very pleasant…one of them (Anna) who is in poor health, is more sweet and womanly.”63 Finding MacDonald’s judgement of the Leigh Smiths somewhat unsympathetic, his biographer (and son), offered up the following explanation: “The intimacy with women so well read and cosmopolitan as the Leigh-Smiths, and belonging to an order of free-thinking intelligence different from any [MacDonald] had yet had intimacies with, offered, I conceive, a new outlook.”64

Anna Leigh Smith was wealthy, liberal minded, and unconventional, and, like her sister, she was an artist and a key figure in the women’s movement. She sat on the board and helped finance the English Woman’s Journal, a monthly journal co-founded by Barbara in 1858 dedicated to female employment and equality issues.65 She also contributed several chapters to Algeria; Considered as a

Winter Residence for the English, a guidebook published in 1858 by her sister from the offices of English Woman’s Journal Anna Leigh Smith was thirty-five years old when she purchased a djnân immediately north of her sister’s property, which she christened “Mountfield” after one of her family’s estates in Sussex, England. The anglicized spelling was soon dropped in favor of the French “Montfeld,” and the property was known for many years as Campagne Montfeld. She shared her home at Campagne Montfeld with her companion, Isabella Blythe, using it on a seasonal basis until about 1890.66

Anna Leigh Smith made significant changes to the roughly 5-acre property she purchased in 1866, including building the house that now functions as the CMR and reimagining the gardens and grounds. Indeed, close study of the CMR suggests that the residence as it stands today may be the result of three separate building campaigns, all carried out during the Anna Leigh Smith ownership period (1866-1909). Leigh Smith worked with the English architect Benjamin Bucknall and contractor Barthélémy Vidal, although questions remain about the exact timing of their involvement and the extent of the interventions. (Analysis of the architectural and landscape development of the CMR is covered in Chapter 3.)

Architect Benjamin Bucknall

Benjamin Joseph Bucknall (1833–1895) was born in 1833 near the town of Stroud, which played a key role during the Industrial Revolution as a manufacturing center for broadcloth. Stroud is located in Gloucestershire County at the western edge of the Cotswolds, a region of southwest England known for its honey-colored limestone buildings. Benjamin was the fifth of seven sons of Edwin Bucknall, an accountant and bank and insurance agent, and Mary Clissold Bucknall, whose family had long been in the wool trade. At the age of 18, he started working as an apprentice to a millwright, a profession that required knowledge of mechanics, practical engineering, and construction. In 1852, Bucknall and his two younger