An association of Davis Brody Bond and The Freelon Group Architects

Lord Cultural Resources and Amaze Design

Smithsonian Institution

National Museum of African American

History and Culture

VOLUME II

Visitation Estimate

Audience Research

Public Engagement

Collections Storage Plan

General Museum Requirements

Exhibition Master Plan

SUBMITTED BY: FREELON BOND

January 30, 2009

Pre-Design: Master Facilities Programming

Smithsonian Institution

National Museum of African American History and Culture

VOLUME I

A Preamble

B Introduction and Executive Summary

C Pre-design and Programming

VOLUME II

A Visitation Estimate

B Audience Research

C Public Engagement

D Collections Storage Plan

E General Museum Requirements

F Exhibition Master Plan

VOLUME III

A Existing Site Conditions

B Geotechnical Analysis

C Vehicular and Pedestrian Traffic

D Site Analysis

VOLUME IV

A Facility Program

B Engineering Systems

C Sustainable Design

D Accessibility

E Security

F Cost Estimates

VOLUME V

Room Data Sheets

A

Appendix

VOLUME VI

A Visitation Estimate

of

E General Museum Requirements

Introduction

Curatorial Objectives and Collections

Public Activities and Program Plan

Organizational Structure and Staffing Framework 06 Meeting the NMAAHC’s Cultural and Design Philosophy: General Requirements

Design Day Planning 08 Summary of Key Calculations

Master Plan

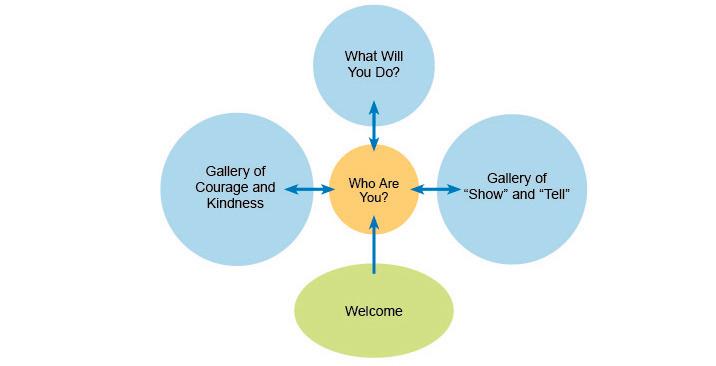

Guiding Principles

Implications of Guiding Principals for the Experience

Goals

Thematic Framework

Interpretive Strategies

Exhibition Walkthrough

Design Considerations

Volume

II Contents

01 Summary 02 Building

Visitation Estimate 03 Visitation Estimate 04 Visitor

05 Visitation

06 Design Day

07 Summary

Key

Research 01 Introduction 02 Summary of Findings 03 Results and Discussion

Public

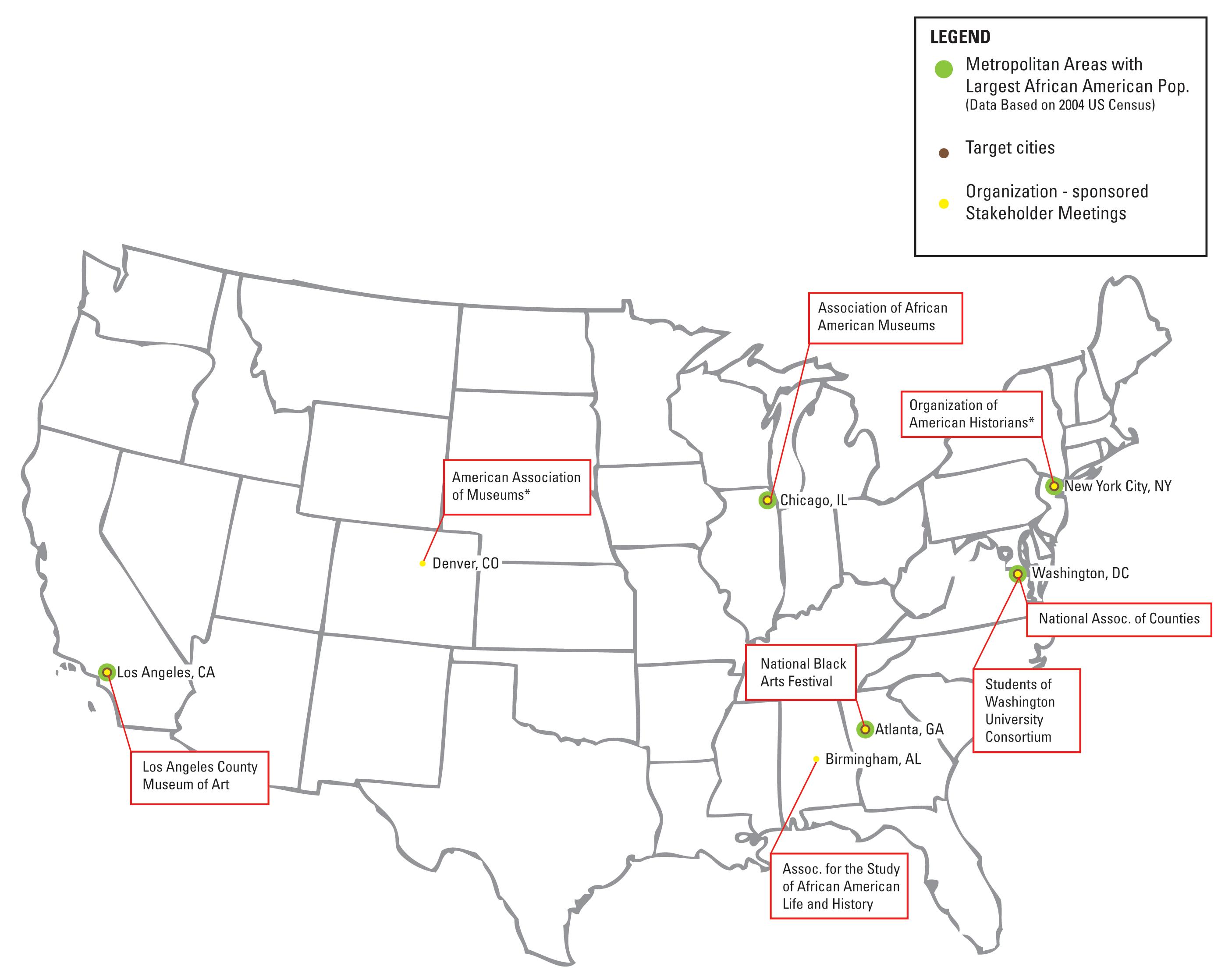

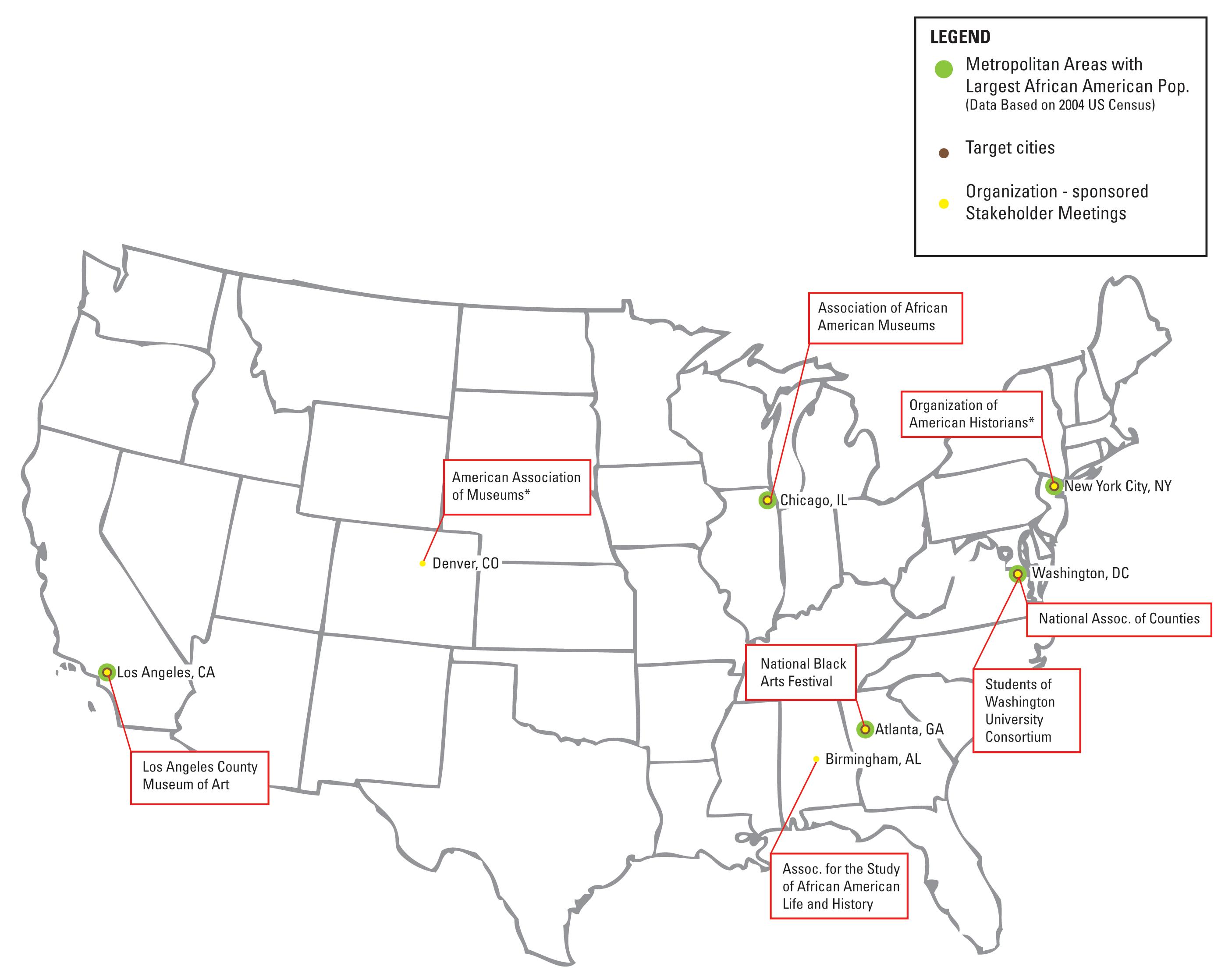

01 Introduction 02 Target

03

04 Key

05

NMAAHC Pre-design Program

the

Segments

Cycles

Planning

of

Calculations B Audience

C

Engagement

Audience for Public Meetings

Development and Location

the Public Meetings

Findings

Key Implications for the

Storage Plan 01 Summary 02 Collections Strategy 03 Recommended Plan to House the NMAAHC Collections and Equipment

02

02

03

05

06

07

09

D Collections

01 Summary

03

04

05

07

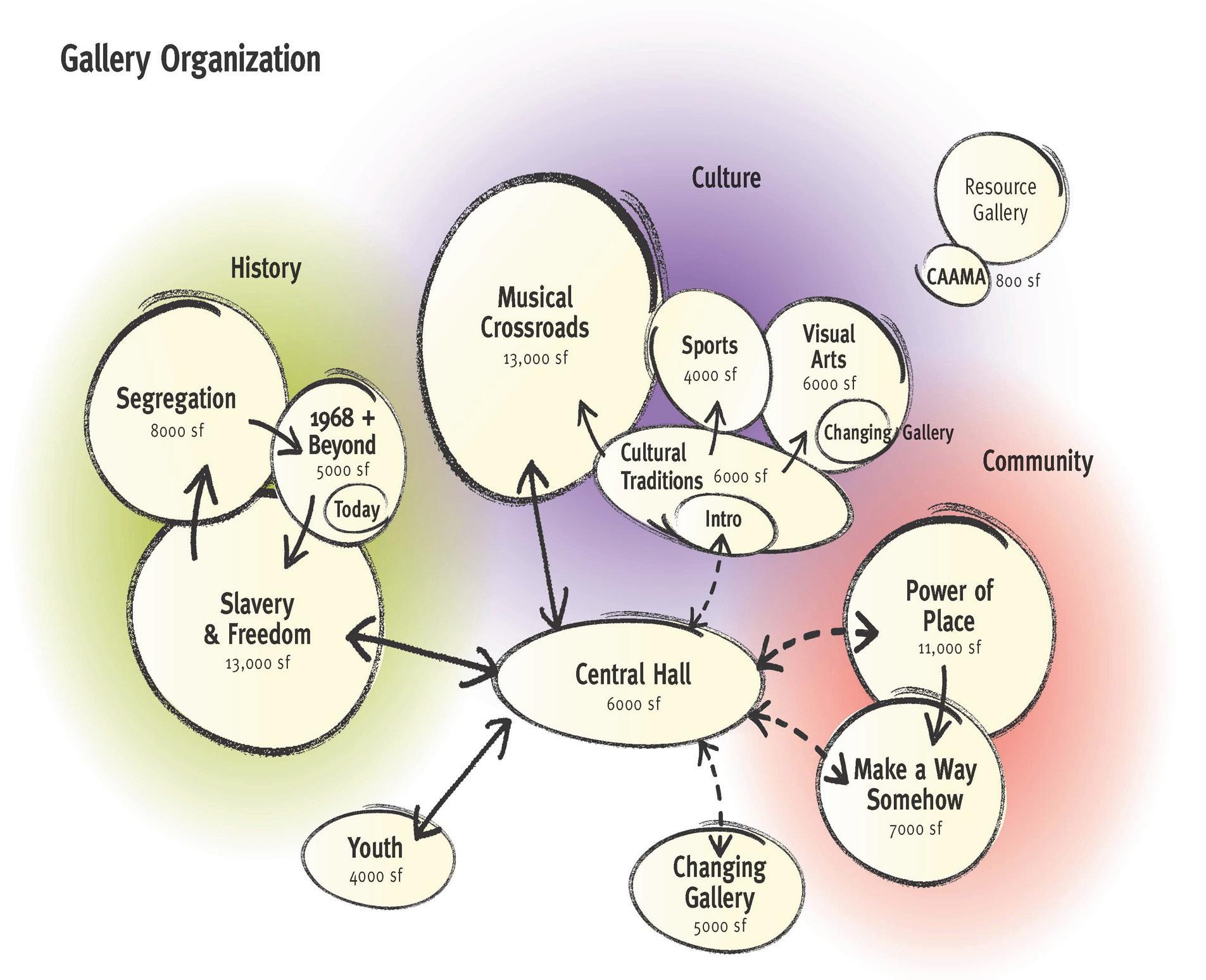

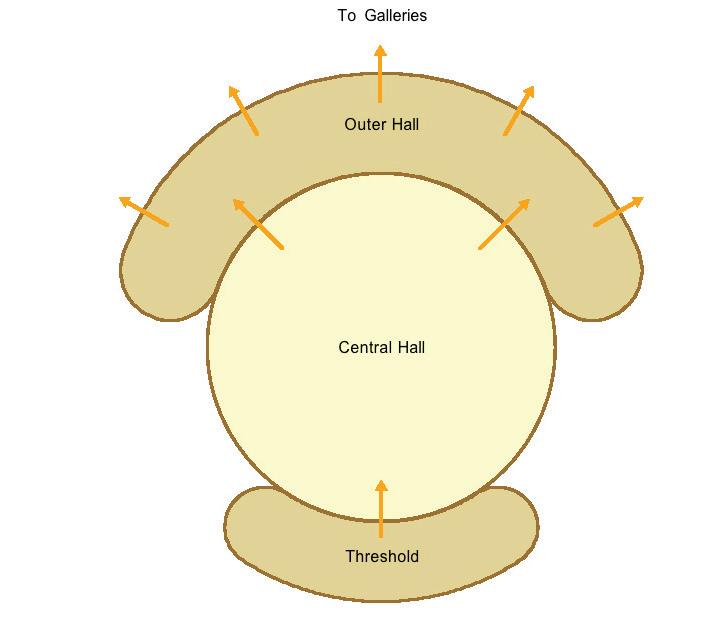

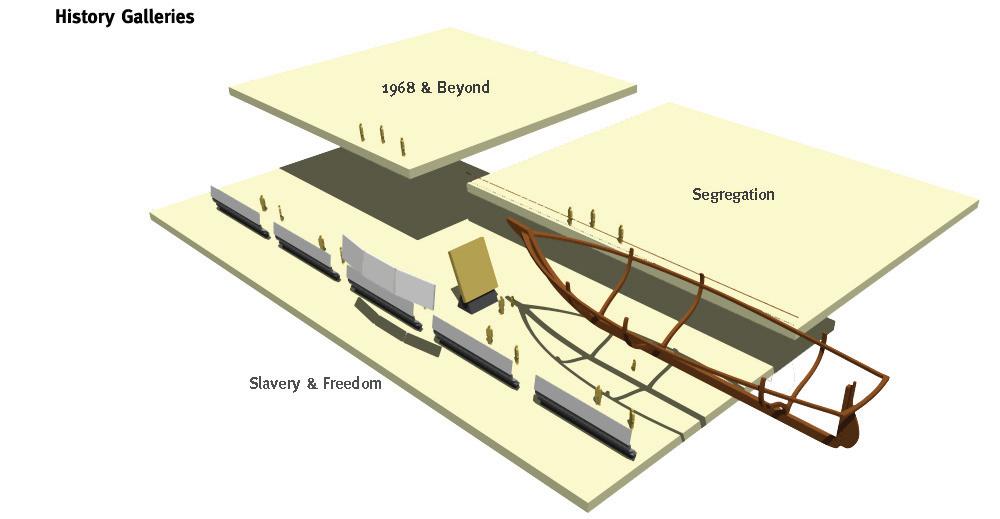

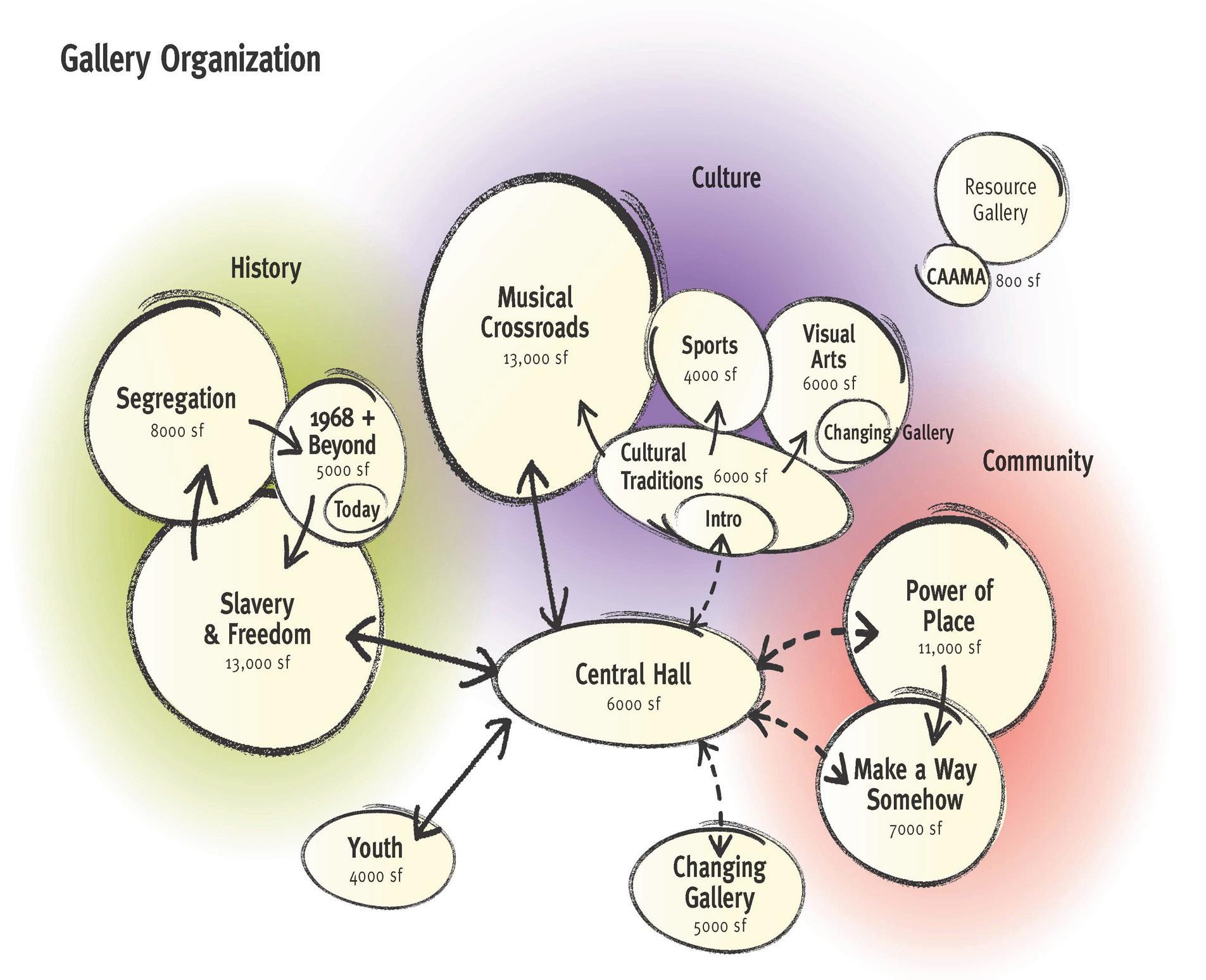

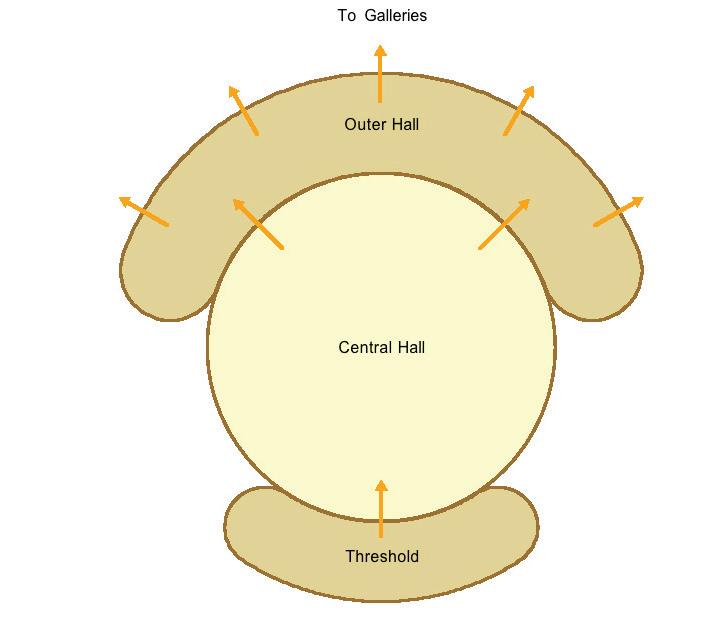

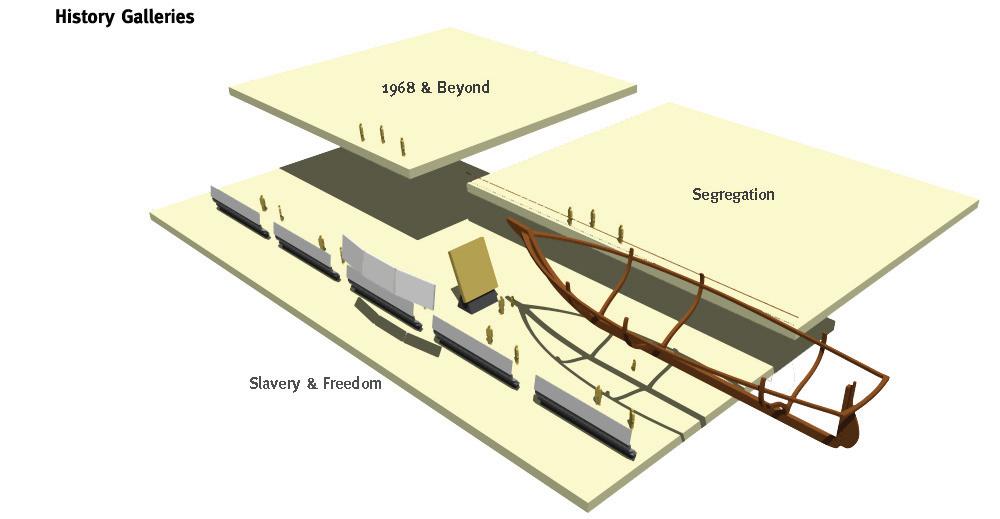

F Exhibition

01 Introduction

Core Message

04

08

A Visitation Estimate

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 8

Summary

The mission of the National Museum of African American History and Culture is:

To share the culture of African Americans, their ongoing struggles for freedom and equality, and the ways their economic role in building the country have shaped America’s history, identity, and democratic ideals.

The visitation goals for this new national museum includes the following:

Engaging everyone, especially African Americans, an under represented visitors to the Smithsonian

Institution, locally, regionally, and nationally;1

Sustaining an outstanding museum that attracts many of the visitors to other Smithsonian

museums and monuments, many of which can be seen from the museum site;

Being one of the most visited museums in the United States;

Striving to be the most effective museum by educating its audience about African American history

and culture.

Freelon Bond, a team of museum planners, architects, and designers, will provide architecture and engineering planning services for the NMAAHC, including an estimate of the number of visitors. Visitation estimates predict the number of people likely to attend the National Museum of African American History and Culture. This report will address:

The “Design Day”;

Seasonality of attendance; and

Other attendance patterns related to the time of day and day of week that may affect the

museum’s facility/space programs and the operating plan.

The “Design Day” is an average busy day for a museum. It is the attendance level for which the museum program is prepared. It is not affordable to build museums for “Peak Days”—a smaller number of days associated with public holidays or peak vacation periods. Determining the Design Day is a key step in the visitation-estimate process. Understanding when Peak Days occur is also important, however, because on these days, visitors need to be managed by museum staff so that—despite the crowds—they still have a great experience. The facility program needs to take Peak Days into account so that the museum’s facilities are flexible enough for staff to successfully manage unusually large crowds.

To date, the team has completed extensive research and consultation, which inform our calculations and judgment, including:

Partnering and visioning workshops with the NMAAHC staff and Smithsonian Institution officials;

Interviews and workshops with museum staff and other stakeholders;

1 The Analysis of Existing Visitation Report demonstrates the under-representation of African Americans in attendance at Smithsonian museums.

9 Visitation Estimate | FREELON BOND

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

01

• study:

Site visits, data collection, and interviews with comparable museums for the following areas of

o Physical structure—National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), Newseum, Canadian Museum of Civilization (CMC), and the Canadian War Museum. Please see table 24 for a complete list of museum abbreviations and acronyms used in this chapter.

o Visitation Estimate—NMAI, USHMM, CMC, Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History and Culture (RFL Museum), and the Japanese American National Museum (JANM).

o Collections—NMAI, National Museum of American History Archives Center, the RFL Museum, the Library of Congress, and JANM.

Over 400 Audience Research Interviews on the grounds of the National Portrait Gallery (NPG);

• the National Zoological Park; the National Museum of American History (NMAH); the National Air and Space Museum (NASM); the National Museum of African Art (NMAfA); the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH); the National Great Blacks in Wax Museum; and the RFL Museum.

Consultation with over 200 individuals in public meetings, which were held in conjunction with

• the National Association of Counties, the Organization of American Historians, and the American Association of Museums in Washington, DC; New York; and Denver.

• region, and the cultural field. Documents consulted were:

A review of background information on the Smithsonian museums, the National Mall, the northeast

o National Park Service, Public Scoping Comments Report: Background Report for the National Mall Plan, 2007

o US Census Bureau, Survey, 2000.

o US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2006.

o District of Columbia Public Schools, Master Education Plan, 2006.

o Market research from DK Shifflet Directions.

o Smithsonian Institution, Office of Protective Services, Visitor Counts 2004–2007.

o United States National Holocaust Memorial Museum Fact Sheet.

o American Association of Museums, Financial Data, 2006.

o American Association of Museums, Official Directory, 2008.

o Smithsonian-wide Survey of Museum Visitors, 2004.

o Government Accountability Office, US National Mall Survey, 2005.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 10

As a result of these extensive research and planning activities, the team has produced a number of documents for discussion with and evaluation by the NMAAHC staff and Smithsonian officials. These documents include the:

Freelon Bond, • Audience Research for the National Museum of African American History and Culture, National Portrait Gallery, and National Zoological Park (Sub-Study 1), Memo of Preliminary Results, April 2008.

Freelon Bond, • Phase Two Visitation Audience Research: Market Analysis, May 2008.

Freelon Bond, • Public Engagement Brief for Stakeholder Meetings #1-3, June 2008.

Freelon Bond, • Analysis of Existing Visitation prepared for the National Museum of African American History and Culture, March 2008.

Freelon Bond, • Summary of Smithsonian Visitor Research, February 2008.

Each report and summary document builds on the findings and conclusions of the previously completed work. The end result is this comprehensive Visitation Estimate.

The Visitation Estimate provides an estimate of the number of people likely to visit the NMAAHC once it is operational. There is no simple formula that leads to credible visitation estimates. For the museum’s purposes we, Freelon Bond, have used a variety of methods, including appraisals and comparisons to other relevant institutions and markets, ratios, and penetration analyses. We also take into consideration other factors, such as proximity to national monuments, location on the National Mall, and the growing diversity of the American population. The impact of key assumptions is also important, especially the following three factors:

1. Delivery of a dynamic, engaging, and interdisciplinary program that attracts the full range of audiences;

2. Inviting building and exhibit designs that maximize public space and are free of bottlenecks; and

3. An operational approach that manages crowds and engages with the public to encourage entrance.

The preparation attendance projections first requires a reasonable definition of a museum visitor. For the purposes of this analysis, a visitor is someone who attends an exhibition or program within the museum, or who otherwise makes use of the public space. This excludes staff, volunteers, and service and delivery people. While outreach and access through the Web site will be important visitation drivers, this visitation projection does not include outreach programs or Web site hits/visits. The projections are thus for on-site visits to the NMAAHC only.

11 Visitation Estimate | FREELON BOND

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 12

Building the Visitation Estimate

The key assumptions that affect attendance projections are those related to the size of the exhibition spaces and the nature and quality of the visitor experience planned for the NMAAHC. Since space planning has not been finalized, these projections will focus on the experience of the model institutions, other relevant Smithsonian museums, the market analyses set out in Phases One and Two, and the data provided by the Institute for Learning Innovation (ILI).

The Visitation Estimate for the NMAAHC is aimed at calculating “steady state” attendance: the number of expected visitors (including those who are there to use the amenities) after the initial rush of first-time visitors has died down. This estimate will be built upon four layers of data and involves both statistical analysis and the judgment of the consulting team. These layers are:

1. Appraisal of the NMAAHC relative to other museums;

2. Ratios for the NMAAHC;

3. Penetration analysis of key visitor segments; and

4. Other key factors

APPRAISAL OF THE NMAAHC RELATIVE TO OTHER MUSEUMS

The NMAAHC will be a museum with national and international appeal and will reside in a host city, the nation’s capital, which enjoys high rates of tourism. Additionally, the NMAAHC will be a Smithsonian Institution. The tables below focus on one or more of these individual characteristics in an effort to understand the effects of the NMAAHC’s particular characteristics more fully. Together, they will help to arrive at an overall visitation estimate for the NMAAHC.

Museums Worldwide with More than 1 Million Annual Visitors

Considering its appeal, scale, and high-profile location on the National Mall, the NMAAHC is examined in the context of museums worldwide that attract over 1 million visitors per year. These museums are studied both as a whole and as members of two categories—Art and History—in order to reflect the nature of the NMAAHC’s exhibition focus. Overall, these museums averaged a total annual attendance of 3.5 million. History and natural history museums ranked above art museums in average annual attendance, at 3.86 million and 3.14 million, respectively.

Among those museums in areas with Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) population (see explanation of MSA in the following table) similar to that of Washington, DC, the average attendance is 2.96 million. The range of visitors to these museums is between 995,000 and 4,000,000. We believe that the NMAAHC’s attendance will rank solidly in the middle of these figures because of the appeal of the museum’s content as well as its location both on the National Mall and in a large and much-visited city.

13 Visitation Estimate | FREELON BOND

02

Table 1: Top Museums Worldwide with More than 1 Million Annual Visitors

Source: The Art Newspaper #189, March 2008; AAM Official Museum Directory, 2008.

* MSA Population indicates Metropolitan Statistical Area, a designation provided by the US Census to define the geographical area surrounding a city’s borders that encompasses businesses, employees, and revenue interlinked with the city proper.

Top Museums in U.S. Cities with Highest Levels of Tourism

A host city’s popularity has an impact on the visitation of institutions that market to out-of-town visitors. The Forbes Traveler rankings assess all major U.S. cities according to the following factors: hotel occupancy, airport and cruise traffic, a consistent method of estimating day travelers, and information provided by convention and tourist bureaus in each metropolitan area.2 This ranking estimates the total number of visitors in Washington, DC for 2007 at 36.9 million.

Taking a city’s resident population into consideration, it is clear that some cities attract more visitors relative to their sizes than others. Washington, DC, is among those cities exceeding the average number of visitors relative to its area’s population.3 Interestingly, museums in the city attract a smaller proportion of visitors than the average among all the museums listed (local museums attract an average of 13 visitors/visitors to the city vs. the average of 21 visitors to a museum/visitors to host city). This discrepancy suggests that greater competition among entertainment attractions exists for Washington, DC, visitors than for the average city analyzed. This analysis highlights how important it is for the NMAAHC to consider the competitive landscape of its host city.

2 Rob Baedeker, “America’s 30 Most Visited Cities,” Forbes Traveler 2007, 3 Based on MSA data.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 14

Art Museums Location Total Attendance MSA Population*(US Only) Musée du Louvre Paris 8,314,000 Metropolitan Museum of Art New York 5,400,000 18,818,536 National Gallery, London London 4,959,782 National Gallery of Art, Washington Washington, DC 4,000,000 5,288,670 Tate Modern London 3,958,026 Musée d’Orsay Paris 3,009,203 Victoria & Albert Museum London 2,900,000 State Hermitage Museum St. Petersburg, Russia 2,395,075 Museum of Modern Art New York 2,219,554 18,818,536 Tokyo National Museum Tokyo 1,772,255 Museum of Fine Arts Houston 1,594,898 5,542,048 Art Institute of Chicago Chicago 1,346,004 9,506,859 de Young Museum San Francisco 1,137,217 4,180,027 Museum of Fine Arts Boston 995,844 4,455,217 Art Museums Average 3,142,990 Art Museums Median 2,647,538 History and Natural History Museums National Air & Space Museum Washington, DC 5,023,565 5,288,670 National Museum of American History Washington, DC 5,000,000 5,288,670 American Museum of Natural History New York 4,000,000 18,818,536 Canadian Museum of Civilization Hull, Québec 1,396,498 History/Natural History Museums Average 3,855,016 History/Natural

Museums Median 4,500,000 All Museums Average 3,495,407 All Museums Median 2,954,602

History

The overall average annual attendance for the museums listed is 2.5 million. For those with tourism activity similar to that of the nation’s capital, average annual attendance is 3.4 million. Based on tourism activity, we believe that the NMAAHC will attract an average of 2.5 million per year, with a likelihood of attracting as many as 3.4 million tourists annually.

Table 2: Museum Attendance and Tourism

Source: AAM Official Museum Directory, 2008

* Forbes Traveler, 2007, “America’s 30 Most Visited U.S. Cities.”

** D.K. Shifflet, 2005.

Ellis Island Museum attendance number is combined with the Statue of Liberty visitation.

Attendance at Smithsonian Institutions

An analysis of Smithsonian Institutions was conducted in the Analysis of Existing Visitation prepared for NMAAHC. Average attendance among all Smithsonian Institutions is 1.4 million. Among the “Big Three” (NMNH, NASM, and NMAH) average attendance is 4.7 million. Among mid-sized museums, average attendance is 1.3 million. The NMAAHC is likely to rank high in the mid-sized museums range, at over 1.3 million.4

4 Freelon Bond, Analysis of Existing Visitation, prepared for the National Museum of African American History and Culture, March 2008.

15 Visitation Estimate | FREELON BOND

Largest US Museums Location MSA Population No. of Visitors at Host City** California Science Center Los Angeles 1,300,000 12,950,129 58,600,000 Getty Museum Los Angeles 1,340,475 12,950,129 58,600,000 Metropolitan Museum of Art New York 5,400,000 18,818,536 44,000,000 American Museum of Natural History New York 4,000,000 18,818,536 44,000,000 Museum of Modern Art New York 2,219,554 18,818,536 44,000,000 Ellis Island Immigration Museum New York 3,408,560 18,818,536 44,000,000 Field Museum of Natural History Chicago 1,212,475 9,506,859 41,300,000 Chicago Museum

Science and Industry Chicago 1,300,000 9,506,859 41,300,000 The Art Institute of Chicago Chicago 1,346,004 9,506,859 41,300,000 National Museum of Natural History Washington, DC 5,542,000 5,288,670 36,900,000 National Air and Space Museum Washington, DC 5,023,565 5,288,670 36,900,000 National Gallery of Art Washington, DC 4,000,000 5,288,670 36,900,000 National Museum of American History Washington, DC 5,000,000 5,288,670 36,900,000 National Museum of the American Indian Washington, DC 1,588,922 5,288,670 36,900,000 United

Holocaust

Museum Washington, DC 1,373,589 5,288,670 36,900,000 Museum of Fine Arts Houston 1,594,898 5,542,048 31,000,000 Franklin Institute Science Museum Philadelphia 850,000 5,826,742 27,700,000 Children’s Museum of Indianapolis Indianapolis 1,200,000 1,669,370 21,700,000 Museum of Science Boston 2,010,000 4,455,217 17,600,000 de Young Museum San Francisco 750,000 4,180,027 15,800,000 Average 2,523,002 9,155,020 37,615,000

of

States

Memorial

Table 3: Attendance at Smithsonian Museums

Source: Smithsonian Institution Office of Protective Services, Visitor Counts, 2007. Excludes National Zoo.

Model and Neighboring Institutions

Attendance for the five model institutions (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Japanese American National Museum, National Museum of the American Indian, the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History and Culture, and the Canadian Museum of Civilization) breaks down into two

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 16

Museum Attendance 2004 2005 2006 2007 Average 2004-2007 “Big Three” National Museum of Natural History 4,366,341 5,629,324 5,874,485 7,115,735 5,746,471 National Air and Space Museum 4,919,510 6,100,871 5,023,565 6,012,229 5,514,044 National Museum of American History 2,924,080 2,990,519 2,957,300 Average 4,069,977 4,906,905 5,449,025 6,563,982 4,739,272 Mid-Sized Museums National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC 2,164,773 1,588,922 1,785,632 1,846,442 The Castle 1,472,308 1,280,015 1,254,219 1,619,530 1,406,518 NASM Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center 1,619,239 1,169,951 1,012,829 1,054,812 1,214,208 Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden 659,104 699,137 757,084 739,830 713,789 Average 1,250,217 1,049,701 1,008,044 1,138,057 1,111,505 Smaller Museums Freer & Sackler Galleries of Art 542,200 469,832 722,293 898,571 658,224 Donald W. Reynolds Center for American Art and Portraiture 480,851 786,056 633,454 National Postal Museum 353,306 518,612 390,343 325,796 397,014 International Gallery at the S. Dillon Ripley Center 178,272 198,356 240,547 296,480 228,414 National Museum of African Art 165,429 157,808 210,593 310,091 210,980 Renwick Gallery at the American Art Museum 115,347 142,511 155,101 132,147 136,277 National Museum of the American Indian, Cultural Research Center 2,243 1,717 1,378 1,011 1,587 Anacostia Community Museum 22,145 24,871 46,425 37,271 32,678 Average 196,992 216,244 280,941 348,428 287,328 TOTAL 17,339,524 21,548,297 17,758,635 21,115,191

groups: smaller museums, with attendance averaging 112,000, and larger museums with attendance over 1.3 million. For the museums in this latter category attendance ranges between 1.4 million and 1.7 million. We believe that the NMAAHC is more likely to rank among the top of these larger categories because of its national appeal and location on the National Mall.

The Audience Research Report indicated that geographical proximity is a factor for visitors when deciding which museums to attend while on the National Mall. In other words, visitors to a monument or museum are more likely to visit one that is nearby than one that is located further away on the National Mall. This geographic proximity correlation is explored below with respect to visitor estimates among those “wandering in” from the National Mall. The findings are used in the present analysis to arrive at a penetration level for the NMAAHC more accurately than if the NMAAHC were compared with the entirety of Smithsonian museums.5 The average attendance among these “neighbors” is 2.6 million, a reasonable range that the NMAAHC may share.

Table 4: Attendance at Model and Neighboring Institutions

Neighboring Institutions

Because NMAH is closed, the attendance figure is from 2005, the most recent available. All other figures are for 2007. USHMM, a model institution, is also a neighboring institution. It appears only once on this chart, under “Neighboring Institutions.”

Attendance at African American Museums in the U.S.

The highest annual attendance among the 20 top-ranking African American museums examined in the Phase 2 Study is 600,000, as reported by the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit, MI.6 Because we believe that this figure ranks far below the scale that the NMAAHC will likely reach, we have not included a more detailed analysis of these museums.

NMAAHC RATIOS

There are several ratios of varying value that may be applied to evaluate future demand for the NMAAHC. These emerge from the selected comparable institutions, the research conducted in Phase One and Phase Two, and the experience of other museums on the National Mall. Taken together, the information from these

5 Freelon Bond, Front-End Audience Research for the National Museum of African American History and Culture: National Mall and African American Museums, Preliminary Report, May 2008.

6 Freelon Bond, Phase Two Visitation Audience Research: Market Analysis May 2008.

17 Visitation Estimate | FREELON BOND

Attendance USHMM 1,655,998 HMSG 739,830 NMAfA 310,091 NMNH 7,115,735 NMAH* 2,990,519 Average 2,562,435

Attendance JANM 120,000 RFL Museum 104,532 CMC 1,396,498 NMAI 1,588,922 Average 802,488

Model Institutions

tables can best estimate the degree to which the NMAAHC’s unique qualities will help shape its rate of attendance.

Visitors per Thousand Tourists and per Thousand MSA Population

Table 5 lists museums’ popularity among their host city’s populations and with tourists. It also compares the NMAAHC with museums competing in comparable markets, both according to regional density and to tourist activity. To most accurately reflect the challenges of the NMAAHC in its competitive environment, two ratios were calculated: (1) a museum’s attendance relative to the MSA population of its host city; and (2) a museum’s attendance relative to the number of visitors descending on its host city. Only those museums in cities with comparable MSA populations and tourist activity were used to determine visitation estimates.

Compared with museums in cities with similar populations, the NMAAHC’s visitation would total 3.0 million. Based on the level of tourist activity, the NMAAHC’s total attendance would be 2.6 million.

Table 5: Ratios for Tourism and MSA Population

Ratios for Tourist Activity and MSA Population

Estimate Based on MSA Population:

Estimate Based on Tourist Activity:

Smithsonian Visitors Per Thousand MSA Population

While it will undoubtedly take a unique position among its cohorts on the National Mall, the NMAAHC will benefit from the same Mall visitors, tourist activity, and national appeal as other Smithsonian Institution museums.

Table 6 examines the attendance of museums on the National Mall, which share similar scale characteristics we think are appropriate for the NMAAHC. The ratio sets museum attendance against the Washington, DC area population in an effort to understand its impact on local and regional communities.

Table 6: Smithsonian Visitors per Thousand Population

Ratios for Tourist Activity and MSA Population

Mid-Sized Museums

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 18

Attendance/1,000 MSA Population 575.3 Attendance/1,000 Visitors to City 71 Washington,

5,288,670 No.

36,900,000

3,042,777

DC MSA Population

of Visitors to Washington, DC

2,619,900

218 Model Institutions 307 Neighboring Institutions 485 MSA Population 5,288,670 Average 336

Population 1,779,386

Estimate Based on Attendance/1,000 MSA

Note that neither the Big Three nor the smaller museums were used in these ratios. The Big Three’s average was 873 visitors per 1,000 MSA residents. Smaller museums attracted 61 visitors per 1,000 MSA residents. Mid-sized museums include the National Museum of the American Indian, the Smithsonian Castle, and the National Air and Space Museum Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center. Model Institutions used were USHMM and NMAI. The others were not relevant for the DC MSA population.7

Neighboring institutions include the USHMM, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (HMSG), the National Museum of African Art (NMAfA), the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH), and NMAH, using the last recorded attendance counts since it closed its doors for renovations. The ratio for this group was higher than the others because two of the Big Three museums were included—NMAH and NMNH. This increases the overall ratio for this analysis. Given the attendance at these sets of museums, the NMAAHC’s annual visitation would be 1.8 million. A complete list of abbreviations and acronyms for the museums discussed in this volume can be found in table 24.

Relevant Institutions per Thousand Mall Visitors

Multiple entry and exit points make National Mall visitation difficult to calculate; consequently, double counting is common. For the purposes of this study, National Mall visitation is calculated based on Monument and Smithsonian museum visitation. This total is 42,146,480.

Table 7: Relevant Institutions per Thousand Mall Visitors

Mall

Source: NPS Survey, 2004

The same institutional sets have been used, and the same caveats apply due to the strength of NMNH, which skews numbers upwards. Based on these calculations, annual attendance at the NMAAHC is estimated to be 1.9 million.

PENETRATION ANALYSIS OF KEY VISITOR SEGMENTS

This section examines the extent to which different visitor market segments—the tourist market, the resident market, and the school group market—will be attracted to the NMAAHC. The tourist market includes both leisure and business travelers, who might visit the museum as part of a day trip or an overnight visit. The resident market comprises visitors who live in the DC MSA, within 50 miles of the institution. Finally, the school group market includes local, national, and sometimes international groups whose trip is folded into a planned curriculum.

The motivations and needs of these audience segments are quite different, as are the strategies used to market to them. While all museums are likely to attract these audience segments, different types of museums attract varying proportions from each segment.

7 Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History and Culture is in Baltimore, MD, sharing the same DC-CMSA, but nonetheless located in a different MSA.

19 Visitation Estimate | FREELON BOND

Ratios for Attendance/1,000

Visitors Mid-Sized Museums 31 Model Institutions 41 Neighboring Institutions 61 Average 44 Mall Visitation 42,146,480 Estimate Based on Attendance/1,000

Visitors 1,868,494

Mall

The Tourist Market

According to Forbes Traveler, 36.9 million people visited the DC MSA in 2007.8 In the same year, about 85% of the visitors to the Smithsonian museums were from out of town.

Table 8 shows the penetration levels of the nearest museums to the site where the NMAAHC will be located. These include USHMM, HMSG, NMAfA, NMNH, and NMAH.

Table 8: Tourist Market

Out-of-Town Visitors

Because NMAH is closed, the attendance figure is from 2005, the most recent available. All other figures are from 2007.

* Source: Forbes Traveler, 2007, “America’s 30 Most Visited U.S. Cities.” Personal interviews.

Penetration levels for the USHMM, HMSG, and NMAfA range between 0.7% and 2.0%— statistically similar proportions. The NMAH and NMNH—among the Smithsonian’s Big Three, along with the NASM—have higher penetration levels, at 17.2% and 7.5%, respectively. The disparity is consistent with variation in scale and national appeal between the Big Three and the mid-sized and smaller museums on the National Mall.

The attendance at the NMAAHC is expected to closely resemble that of the USHMM, which has a penetration level of 2%. The reasons for this are twofold: first, the NMAAHC has specialized content—like the USHMM—which past Freelon Bond research has shown does not appeal to everyone;9 second, the NMAAHC is expected to have strong visitation from the DC MSA, as is the case with the USHMM (55% local). Overall, it is expected that the NMAAHC will realize a market penetration of 2% to 3%, or 738,000 to 1,107,000 visitors.

The Resident Market

The Washington, DC MSA region reported a population of 5.3 million in 2005. To estimate the degree to which the NMAAHC may attract members of this population, table 9 looks at resident-market visitor numbers at the NMAAHC’s model institutions, as well as relevant Smithsonian museums.

8 Forbes Traveler, 2007, “America’s 30 Most Visited Cities.”

9 33% of visitors to the Mall said that they do not intend to visit the NMAAHC. Freelon Bond, Front-End Audience Research, May 2008.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 20

Attendance Nationwide Outside US Out-oftown Visitors No. of Out-ofTown Visitors DC MSA Visitors Penetration Level Attendance USHMM 1,655,998 36% 9% 45% 745,199 36,900,000 2.0% 1,655,998 HMSG 739,830 65% 10% 75% 554,873 36,900,000 1.5% 739,830 NMAfA 310,091 66% 14% 80% 248,073 36,900,000 0.7% 310,091 NMNH 7,115,735 82% 7% 89% 6,333,004 36,900,000 17.2% 7,115,735 NMAH 2,990,519 83% 9% 92% 2,751,277 36,900,000 7.5% 2,990,519 Average

2,562,435

Table 9: Resident Market

Because NMAH is closed, the attendance figure is from 2005, the most recent available. All other figures are from 2007.

* Baltimore population is for the city proper, not MSA.

** Quebec population indicates the “Quebec Metropolitan Community.”

*** Source: Personal interviews, US Community Survey, US Census Bureau, 2006. Smithsonian Institution Office of Protective Services, Visitor Counts 2007.

The museums examined demonstrate the full range of penetration levels for the resident market, with a cluster of 11%, 15%, and 17%. Longevity and outreach may help to explain why the USHMM’s penetration is, for example, more than 10% greater than that of the NMAI. The USHMM targets local and regional educators and managers, including teachers and law enforcement officials, with specially designed educational programs and group trips. This concerted effort undoubtedly accounts for the level of penetration into the local and regional market.

An important factor to consider is that 26.5% of the Washington, DC MSA population is African American. As well, African Americans in the area share the socioeconomic characteristics that overlap with average museum-going visitors to a greater degree than African Americans in the nation as a whole. It is therefore likely that penetration levels for the NMAAHC will benefit from a core constituency based within a 30 minute drive of the museum.

It is expected that the NMAAHC will realize a strong penetration of the resident market, between 15% and 20%, or 795,000 to 1,060,000 visitors.

The School Group Market

The Washington, DC CMSA is a broader region than the Washington, DC MSA. It comprises both the DC MSA and Baltimore, Hagerstown, and Frederick, MD. The population of school children aged 5–17 in this region is 1.4 million.10 USHMM, which compares favorably with the NMAAHC, reported that school visits made up 12% of its 2006 attendance, amounting to 199,000 children visiting in groups or a penetration rate of 14%. The RFL Museum, on the other hand, welcomed 27,200 school visitors, or a 2% penetration rate.

With over 40,000 African American children in DC public schools alone, it is expected that the NMAAHC will have a healthy penetration of the school market.11 This rate is expected to be between 10% and 15%, or 140,000 to 210,000 children visiting in school groups.

10 US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2006.

11 For the purposes of this study, it is assumed that visiting school groups are only from the DC CMSA.

21 Visitation Estimate | FREELON BOND

Neighboring Institutions Attendance % Resident Visitors No. Resident Visitors MSA Population % Penetration Level USHMM 1,655,998 55% 910,799 5,288,670 17% HMSG 739,830 25% 184,958 5,288,670 3% NMAfA 310,091 66% 14% 5,288,670 1% NMNH 7,115,735 82% 7% 5,288,670 15% NMAH 2,990,519 83% 9% 5,288,670 5% Model Institutions JANM 120,000 63% 75,600 12,950,129 1% RFL Museum** 104,532 65% 67,946 640,064 11% CMC*** 1,396,498 21% 300,000 712,000 42% NMAI 1,588,922 22% 349,563 5,288,670 7%

OTHER KEY FACTORS INFLUENCING VISITATION ESTIMATE

In addition to the ratios and rankings developed above, there are a variety of indicators that need to be considered when evaluating likely potential attendance for the NMAAHC. Some of these estimates suggest higher attendance levels than we indicated in the various analyses, while others suggest more modest levels. These points are more qualitative than quantitative and will be taken into consideration as part of Freelon Bond’s judgment in the final analysis.

Positive Impacts

Museum Content

The NMAAHC’s broad scope and universal message will increase demand for museum attendance. The content is expected to attract not just people who are interested in American history but also those who are interested in the broader aspects of American life, both past and present. This broad reach is a unique departure from museums that focus exclusively on history, particularly those whose specialty is American history.

The NMAAHC will be a forerunner in the vision to present a thorough understanding of American history through the lens of African American perspectives and experiences. People already familiar with the American historical narrative will seek out the NMAAHC for a more nuanced understanding.

NMAAHC’s Location on the National Mall

Its iconic status as a national museum and as a Smithsonian museum identifies the NMAAHC as a gem among American cultural institutions. By virtue of its location on the National Mall, the NMAAHC will benefit from a steady stream of visitors who descend on the landmark district as part of a patriotic pilgrimage.

Proximity to the Washington Monument

The NMAAHC’s particular position on the National Mall links it with the Washington Monument. The Monument is a limited-capacity ticketed site that turns away many more visitors than wish to visit it. Those who have been turned away are likely to search for an alternative attraction once they have made the trek to the Monument. The NMAAHC presents an attractive alternative for these visitors, and, as we know from Freelon Bond research, visitors are most likely to cluster their activities by location or proximity.

Effect of the new Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial

The NMAAHC will benefit from the opening of the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial, which is expected to attract millions of visitors per year. In addition to becoming a point of pilgrimage for the African American community, the Memorial is expected to inspire many visitors to learn more about the African American experience. Although the NMAAHC is not in close proximity to the Memorial, it will still be within walking distance, and the two sites are expected to see major cross-visitation activity.

A Diverse and Educated Population

The local population that the NMAAHC will draw upon is diverse and highly educated, and therefore likely to visit repeatedly. Nationwide, persons identifying as white will decline over the next 20 years (although the Hispanic and Asian populations will grow, the African American population will not). The US Census Bureau projects that by 2025, the national population will be increasingly diverse.12

Education is the single most important indicator for museum participation; in the DC MSA, 29% percent of African Americans hold a bachelor’s degree or higher. This percentage is higher than the national average (17%) among African Americans and among all people over the age of 25 in the United States (27%).

Furthermore, Prince George’s County, MD, a suburb of Washington, DC, has one of the most educated African American populations in the country. Thirty-three percent of the county’s African American 12

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 22

US Census Bureau, Population Projections.

population has a bachelor’s degree or higher, a proportion exceeding the educational attainment of the county as a whole (30%), regardless of race.13

An added group likely to visit the NMAAHC in greater numbers is the African American population along the Atlantic Coast. This group is more educated and possesses a greater income than its cohorts nationwide.14 Moreover, studies on leisure travel show that tourists are increasingly traveling by automobile, rather than airplane. East Coast travelers are thus likely to make up a greater proportion of visitors to Washington, DC, than in the past.15

Washington, DC, Tourists’ Profile: Tourists are Museum Visitors

According to Forbes Traveler, 36.9 million16 people visited the Washington, DC, metropolitan area in 2007. The city is above average in visitor attraction relative to its MSA. Most visitors to Washington, DC, possess the average museum-goer’s socioeconomic characteristics. According to D.K. Shifflet, 84% of visitors to the city have attended at least some college and almost a quarter hold graduate degrees. Additionally, over 50% of travelers to Washington, DC, report per capita incomes of over $75,000. These traits overlap with the highly educated and wealthy constituents that attend museums.17

A Focus on Amenities

The NMAAHC is intent on overcoming the barriers for those who are not accustomed to visiting museums or, perhaps, a museum with an African American focus. One of the methods it hopes to use is to welcome National Mall visitors with much-needed amenities. A survey of visitors to the National Mall found that over one-third of them were looking for such amenities as washrooms, places to rest, and places to buy food.18 As a result, the NMAAHC is expected to draw in visitors who may not have planned to attend the museum ahead of time.

Signature Architecture

The selection of an innovative design is expected to draw both critical acclaim and visitors who are interested in seeing the new building regardless of its exhibition or collections.

Heightened Interest in African American Culture

Recent shifts in national attitudes suggest a stronger interest in African American heritage. A Pew Study showed that people expressed greater acceptance of mixed-race dating in 2004 than they did as recently as 1994.19 This finding, along with the recent overwhelming support for the first African American presumptive presidential nominee, suggests a greater enthusiasm for African American history and culture than ever before.

More People are “Black-Invested” “Black-invested” individuals are those who possess a strong personal tie to the African American community, whether by living in an interracial household or having close black friends. Regardless of their race, these people are likely to possess an important investment in Black culture and identity, perhaps possessing an intimacy that is likely to last beyond a passing intellectual curiosity. Researchers have found that the number of cross-race friendships in the US is increasing for both children and adults.20

13 US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2006.

14 Ibid.

15 D.K. Shifflet & Associates in partnership with Travel Industry Association of America, Washington DC’s 2006 Visitor Statistics, August 2007.

16 Forbes Traveler reports a significantly higher visitation rate for Washington, DC, than DK Shifflet in its tourist and leisure estimates. The former estimates travel into the MSA region; the latter, reporting a total of 15.1 million visitors, strictly studies the city proper. While this study prefers to rely on overall numbers from Forbes Traveler, DK Shifflet’s research is nonetheless vital to and understanding of general characteristics of the Washington, DC visitor.

17 Freelon Bond, Analysis of Existing Visitation prepared for the National Museum of African American History and Culture, March 2008.

18 US Government Accountability Office, Report to the Chairman, Committee on Government Reform, House of Representatives, June 2005.

19 Pew Research Center, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, March 2006.

20 Elizabeth Page-Gould & Rodolfo Mendoza-Denton and the Center for Peace and Well-Being, Cross-Race Relationships: An Annotated Bibliography, University of California, Berkeley, 2005.

23 Visitation Estimate | FREELON BOND

Mixed or Unclear Impacts

The following factors also need to be considered when assessing the NMAAHC’s visitation estimates. Some may indicate lower attendance levels; the influence of others is as yet undetermined.

Uninitiated Public

While instantly welcomed by many people, the NMAAHC may be an institution whose mission needs to be understood over time by others. Some people may fear that the institution is exclusionary or will try to blame them for racial injustice in the United States. Others simply may not fully comprehend the universal message that the NMAAHC will present, and believe that “This is not for me.”

Stable DC MSA African American Population

It is noteworthy that demographic projections for the DC MSA estimate that the proportion of African Americans will remain constant from 2005 to 2015, holding forth at approximately 25%. While the proportion of White residents is expected to decline, it is the proportion of Hispanic and Asian residents that is growing.21

21 Woods and Poole Economics, The Complete Economic and Demographic Data Source, 2006.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 24

Visitation Estimate

The following calculations incorporate analyses in this chapter. It concludes with an estimate for visitation at the NMAAHC.

CALCULATION OF VISITATION ESTIMATE FOR STEADY STATE

Table 10 summarizes the figures emerging from the various ratios and rankings discussed in Section 2.

Table 10: Evaluation Methods for Visitation Estimate

Two scenarios emerge from this analysis, one conservative, the other aggressive (see table 11). When the NMAAHC is compared with museums that have similar content and estimated scope, such as the USHMM, the mid-sized museums on the National Mall, and neighboring Smithsonian museums, the NMAAHC’s attendance is estimated at about 1.7 million. This estimate is based on past experience and visitation attendance of museums that share some important characteristics with the NMAAHC.

The aggressive scenario, in part, takes into account broader market indicators, such as a metropolitan area’s level of tourist activity and size. The average for this cluster is 2.6 million. Based on these factors, as well as the attendance levels of museums worldwide attracting over 1 million visitors, the NMAAHC’s steady state attendance is estimated to be 2.5 million.

25 Visitation Estimate | FREELON BOND

Evaluation Methods Appraisal Range Estimate Worldwide Museums with >1m Visitors 995,000 4,000,000 2,497,500 Average Attendance of Museums in Tourist Markets Similar to DC MSA 2,500,000 Mid-Sized Smithsonians 1,300,000 Model and Neighboring Institutions 1,400,000 1,700,000 1,700,000 Average 1,999,375 Ratios Estimate Worldwide Museums with >1m Visitors 3,000,000 Average Attendance of Museums in Tourist Markets Similar to DC MSA 2,600,000 Mid-Sized Smithsonians 1,800,000 Model and Neighboring Institutions 1,900,000 Average 2,325,000 Penetration Range Tourist Market 738,000 1,107,000 Resident Market 795,000 1,060,000 School Market 140,000 210,000 1,673,000 2,377,000 Total Estimate 1,674,600 2,594,900

Selected

03

Key factors discussed in the second chapter are critical in reconciling these two scenarios. Given the high degree of content appeal, a core constituency of African Americans in the DC MSA population, its location on the National Mall, and the presence of the Washington, DC, Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial, we believe that the NMAAHC is likely to realize the attendance rates estimated in the aggressive scenario. Attaining the aggressive attendance estimate is dependent on three factors:

1. Delivery of a dynamic, engaging, and interdisciplinary program that attracts the full range of audiences;

2. Inviting building and exhibit designs that maximize public space and are free of bottlenecks; and

3. An operational approach that manages crowds and engages with the public to encourage entrance.

Table 11: Conservative vs. Aggressive Visitation Estimates

Conservative

Mid-Sized Smithsonians

Model and Neighboring Institutions

SI Attendance/1000 DC MSA

SI Attendance/1000 Mall Visitors

Aggressive Museums with >1m Visitors

Average Attendance of Museums in Tourist Mkts Similar to DC MSA

Museum Attendance/1000 Host City MSA Pop.

ESTIMATED VISITATION FOR YEARS 1, 3, AND 5

Virtually all new or expanded museums and related institutions experience their highest attendance levels in the first year; by Year 3, attendance declines, generally by about 20%. Visitation may increase slightly by Year 5. This is particularly true for institutions that have a strong resident market. Such a pattern has been assumed for the NMAAHC, which will unveil a signature building that is expected to attract a significant number of one-time visitors in the first year.

Our work is also based on the experience of the following model institutions:

Canadian Museum of Civilization (CMC)

The CMC is an outlier in achieving a steady state of attendance earlier than most museums. The museum differs from the NMAAHC in critical ways—most importantly, it had been in existence since 1856 and was aware of its audience potential for several years prior to its reopening in 1989. As a result, both audience expectation and marketing strategies were more advanced than those typically devised for a museum opening its doors for the first time.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 26

1,300,000

1,700,000

1,800,000

1,900,000 Penetration–Low 1,673,000 Average 1,674,600

2,497,500

2,500,000

Museum Attendance/1000

2,600,000 Penetration–High 2,377,000 Average 2,594,900

3,000,000

Visitors to Host City

National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI)

The NMAI is still within its five-year period of expected attendance fluctuation following its opening. So far, attendance levels have been following traditional museum trends. By Year 3, attendance had dipped by 21.2%. Though it has not yet reached Year 5, further internal marketing strategies and projections, and steady tourist activity, anticipate a rise of 5% by the end of Year 4.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM)

The oldest museum of the three, the USHMM, experienced a rise in Year 2, contrary to museum trends. This is explained by the museum’s difficulty in meeting capacity demands in Year 1, and evolving operational systems in response to those demands to accommodate more visitors in Year 2.

Table 12: The Experience of the Model Institutions

Percent Difference between Years

Museum Year Opened Year 3 Year 5

Source: Personal Interviews.

We estimate that attendance at the NMAAHC will be in the range of:

3 million in Year 1, approximately 20% higher than steady state attendance;

2.5 million in Year 3, the steady state calculation; and

2.55 million in Year 5, as the program and collection matures, the population grows, and museum

attendance diversifies (+2%).

27 Visitation Estimate | FREELON BOND

Museum Year Opened Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Year 5 NMAI 2004 n/a -26.6% 12.4% n/a n/a USHMM 1993 n/a 6.6% -13.9% 8.8% -0.9% CMC 1989 n/a -6.0% 5.3% -3.7% 2.4% Average Annual Difference -8.7% 1.2% 2.6% 0.8%

NMAI 2004 -21.2% n/a USHMM 1993 -9.0% 7.2% CMC 1989 -1.1% -1.3%

•

•

•

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 28

Visitor Segments

VISITATION BY MAIN MARKET SEGMENT

Estimating attendance by main market segment requires using analysis from several data sources. These include:

Demographic data and projections derived from the US Census Bureau and Woods & Poole • Economics, Inc., an independent firm that specializes in long-term economic and demographic projections;

Tourism data from the Washington, DC, Convention & Tourism Bureau and

Forbes Traveler;

Personal interviews with and data collection from model institutions; and

Analysis conducted by Freelon Bond during the first two phases of this study.

The Resident Market

Estimating the NMAAHC’s resident market takes into account Smithsonian museum attendance in general. In order to provide greater utility this analysis will distinguish between the Big Three and the four mid-sized museums included in this study. Resident markets visiting the model institutions are also examined.

Overall, residents of the Washington, DC, region made up 17.4% of Smithsonian attendance in 2006.22 Although different in scale and scope from these museums and from the NMAAHC, 20% of the National Museum of African Art’s visitors were local. Additionally, residents made up 85% of the Anacostia Community Museum’s overall attendance23

An analysis of model institutions further helps to estimate the resident market proportion of the NMAAHC’s overall visitation. The USHMM welcomed slightly over 900,000 visitors from the Washington, DC, region in 2006, or 55% of its total visitors. In the same period, 22% of the visitors to the NMAI were local.24

The NMAAHC is likely to exceed the proportion of the area market that all Smithsonian museums combined attract. It will benefit from the large African American community in the DC MSA, which is likely to visit museums given its higher-than-average socioeconomic levels relative to the nation as a whole. Indeed, the NMAAHC will edge closer to the USHMM in its overall percentage of local-resident visitors because of the museum’s level of community outreach. However, given its universal message and its larger core constituency of African American visitors, it is reasonable to assume that the NMAAHC’s appeal will reach far beyond the resident market, more so than the USHMM. It is therefore estimated that the resident market will make up 35% of the NMAAHC’s overall attendance.

22 Smithsonian Institution, Office of Policy and Analysis, Results of the 2004 Smithsonian-wide Survey of Museum Visitors, October 2004. 23 Ibid.

24 Smithsonian Institution, Office of Policy and Analysis, A Comparison of Visitors to the National Museum of the American Indian to General Smithsonian Visitors, April 2005.

29 Visitation Estimate | FREELON BOND

•

•

•

04

The School Market

School groups make up an important proportion of a museum’s overall attendance. The average museum attracts 15–40% of its total attendance from the school-group market. Indeed, as discussed in Freelon Bond’s Analysis of Existing Visitation, 27.5% of Smithsonian Institutions’ overall attendance is from school groups.25

By contrast, the average school group proportion among the five model institutions interviewed—the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the National Museum of the American Indian, the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History and Culture, the Canadian Museum of Civilization, and the Japanese American National Museum—was just 14.4%. The disparity in school group proportions between Smithsonian museums and model institutions may be explained by the Smithsonian Institution museums’ established destination among local and national school groups, as well as their levels of efficiency in managing school group attendance, and the model institutions’ more limited reach, both because of geographic location (JANM is located in a dense residential neighborhood in Los Angeles, for example) and specific content. Among all the institutions interviewed, the USHMM most closely approximates the high profile and potential for national appeal that the NMAAHC will achieve.

The NMAAHC is likely to approximate other Smithsonian museums (27.5%) as well as the USHMM (12.1%) in its attraction of school groups. Therefore, school group attendance is estimated at 20%.

The Tourist Market

Tourism is a major economic generator in communities across the nation. Tourists can be segmented by both motivation (e.g., business and convention, leisure, recreation, eco-tourism, cultural tourism) and by the activities in which they participate while traveling. For the purposes of this analysis, tourists keen on cultural attractions—“cultural tourists”—are of particular interest. Research shows that the number of cultural tourists is growing. This group stays longer at its host city, and spends more money than other types of tourists.26

Visitors to Washington, DC, possess many of the same characteristics and interests as cultural tourists in general. Among visitors to the city, 84% have attended at least some college. In fact, almost one-quarter earned a graduate degree. Over 50% of Washington, DC, visitors reported per-capita incomes over $75,000. Moreover, 35% of Washington, DC, visitors were between 35 and 49 years old. Finally, 8% of visitors were African American, a proportion that remained steady from 2000 to 2006.27

Out-of-town visitors made up 82.6% of overall attendance for Smithsonian Institution museums in 2004.28 By contrast, the model institutions (NMAI, USHMM, and CMC) are more likely to attract local visitors than the museums on the National Mall. On average, these model institutions welcomed 38% of visitors from out-of-town.29

With active efforts to build a strong local community and a mission that will be nationally and internationally attractive, the NMAAHC is likely to straddle the national appeal of its fellow National Mall residents and the strong local base of its model institutions. A particularly relevant example, surpassing other model institutions, is the USHMM (45% of total attendance comprises tourists). Taking into account the example of the USHMM in light of Smithsonian comparisons, the NMAAHC is expected to realize 45% of its total attendance from the tourist market.

25 Freelon Bond, Analysis of Existing Visitation, Prepared for the National Museum of African American History and Culture, March 2008.

26 Travel Industry Association of America, The Historic/Cultural Traveler, 2003.

27 D.K. Shifflet & Associates in partnership with the Travel Industry Association of America, Washington, DC’s 2006 Visitor Statistics, August 2007.

28 Smithsonian Institution, Office of Policy and Analysis, Results of the 2004 Smithsonian-wide Survey of Museum Visitors, October 2004.

29 Model institutions with available data on geographic breakdowns are the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Japanese American National Museum, and the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History and Culture.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 30

Steady State NMAAHC Attendance by Market Segment

If the steady state attendance for the NMAAHC is examined along these market segment lines, it breaks down as shown in table 13:

Table 13: Projections for Market

Segments

VISITATION BY VISITOR

CATEGORY

The NMAAHC’s attendance will comprise the following types of visitors: individual adults and groups, school and adult, senior, children, and “wanderers.” This section discusses each type and estimates the respective proportions.

Table 14: NMAAHC Visitation by Visitor Category

Individual Adults

At the same time that the adult age group is expected to shrink in the DC MSA, average per-capita income will rise for both the DC MSA and the nation as a whole, more so nationwide (11.6%) than in the DC MSA (9.3%).30 Based on this trend, the NMAAHC will likely benefit from an increase in average income both locally and nationally.

The NMAAHC’s attendance will likely be 45% adult, despite the slight decrease in the adult age group proportionally in both geographic areas.

School Groups

The proportion of school groups is likely to be 20%.

Adult Groups

Adult groups are likely to approximate the levels experienced at the USHMM. Because of the strong ties that both ethnic and racial groups have to their heritage, African American adult groups, among others, will display an analogous tendency to patronize the NMAAHC. That proportion is expected to be 5%.

30 Woods and Poole Economics, The Complete Economic and Demographic Data Source, 2006.

31 Visitation Estimate | FREELON BOND

Market Segment Projections (Percent) Residents 35 Tourists 45 Schools 20

Visitor Categories Attendance Percentage Adults/Individuals 1,125,000 45 School Groups 500,000 20 Adult Groups 125,000 5 Seniors 375,000 15 Children 125,000 5 Wanderers 250,000 10

Seniors

For the purposes of this report, seniors are those aged 59 years and over. Their habits will reflect the spirit of adventure that the baby boomer generation embraces. The DC MSA population will experience a larger percentage increase in this age group than will the nation as a whole, with the proportion increasing by more than twice the national percentage. Nationwide, the proportion of seniors will rise from 13% in 2005 to 19% in 2025.31

The NMAAHC will likely realize similar levels of senior attendance as the Smithsonian Institution museums, one that will reflect the large increase in the local senior population and the attraction that a cultural destination will have on an adventurous older age group. Therefore, while not increasing nearly as much as the proportion of seniors in the general population, the NMAAHC is likely to see seniors become 15% of its total attendance.

Children

Considering trends among families to travel during spring breaks and summer vacation as well as the nonschool group interests among residential children coming with their families, it is estimated that non-school group children will mirror the level seen by the Smithsonian Institution museums overall, at 5%.

Wanderers and Amenity Seekers

As discussed in previous reports, the majority of National Mall visitors do not enter a museum when they visit.32 When interviewed about their interest in an upcoming museum on African American history and culture, 27% of visitors to the National Mall said that they would visit that day and 16% said that they would visit during that trip. One-third of those interviewed said they were not likely to visit the NMAAHC at all.33

The NMAAHC is striving to meet the needs and interests of these and other visitors with premier exhibits, relevant themes, and an attractive visitor experience. Among its strategies is to purposely aim its effort at those National Mall visitors who may be prone to wander into the museum.

The wanderer will likely visit the museum for three main reasons:

1. He or she is looking for a particular desired amenity;

2. The museum is close to a planned destination; and

3. The visitor has had an unexpected change of plans. Nearly one-third of people (32%) who answered a National Park Service (NPS) survey on what they wanted on the National Mall cited a desire for a breadth of amenities, many of which could be satisfied by the NMAAHC (including washrooms, food, water, seating, information, and shopping).34 This finding suggests that although a small percentage of National Mall visitors visit a museum, that trend may change if museums can satisfy amenity needs. Because the NMAAHC is anticipating the needs of National Mall visitors in its facilities planning, the museum is likely to realize an attendance boost by accommodating those needs.

The Freelon Bond Audience Research Report presented in 2008 studied the likelihood of visitors who have patronized one museum or monument visiting another attraction on the National Mall.35 Indeed, a strong

31 US Census Bureau, Population Projections.

32 Freelon Bond, Summary of Smithsonian Research, March 2008.

33 Freelon Bond, Front-End Audience Research, May 2008.

34 US Government Accountability Office, Report to the Chairman, Committee on Government Reform, House of Representatives, June 2005.

35 Freelon Bond, Front-End Audience Research, May 2008.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 32

predictor of choice for additional attraction visits was geographic proximity. Between 10% and 17% of visitors to the Washington Monument said they would visit nearby museums.

The study also found that 70% of people visiting the National Mall changed their original plans at least one day before their visit. Interestingly, 17% indicated that they made a spontaneous decision to visit a site they had not originally planned to see. This finding suggests a certain level of willingness to wander around after arriving at the National Mall.

Taking these factors into account, we believe that the NMAAHC will attract 10% of its total visitors from those wandering on the National Mall.

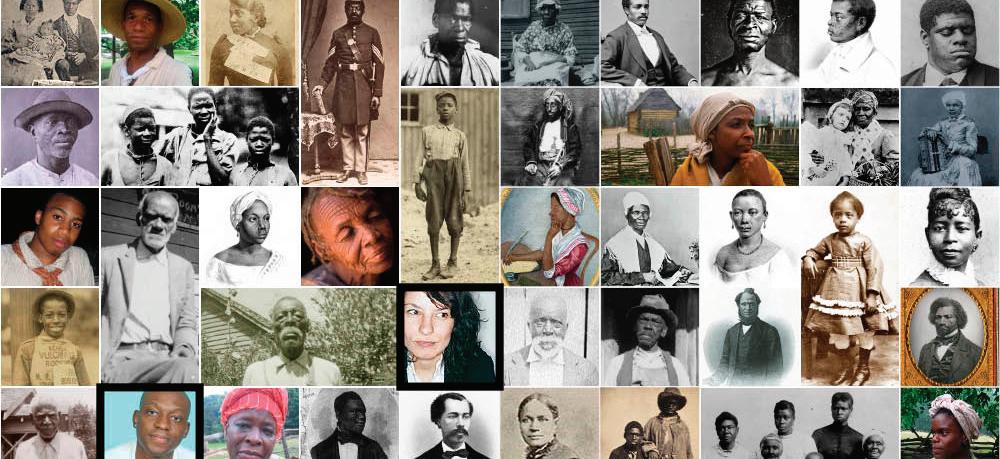

VISITATION BY RACE/ETHNICITY

The NMAAHC will strive to welcome all individuals with a superb collection, signature architecture, diverse programming, and a mission that has universal appeal. Simultaneously, the museum will aim at attracting a core constituency of individuals of African American descent, persons identifying as mixed race, and people of color. Visitation estimates for these three groups are analyzed in this section.

Looking at African American museums has the advantage of examining institutions whose focus, in part, matches that of the NMAAHC. However, as mentioned earlier, none of the museums currently open is on a scale that matches the estimate for the NMAAHC. The museum with the largest attendance is the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit, MI, with annual visitation totaling 600,000. Moreover, for three museums examined in detail, African Americans made up between 60% and 80% of total attendance.36 The NMAAHC is more likely to attract a broad audience that will welcome African American and non-African American visitors in proportions more similar to other Smithsonian museums than African American museums across the nation.

As the Analysis of Existing Visitation Report revealed, African Americans are more likely to attend exhibits and museums when themes of personal relevance are presented.37 As the table below illustrates, whereas 9% of Smithsonian museum visitors are African American, five times that percentage of African Americans make up the total attendance at the National Museum of African Art (NMAfA). African American attendance is nearly ten times greater at the Anacostia Community Museum than at Smithsonian museums overall, although this institution’s strong community-based focus differs from Smithsonian museums in general.

Table 15: Proportion of African American Attendance at Smithsonian Institution Museums

Source: NMAI MVS Study, March 2006.

DC MSA: African Americans 26.5

US: African Americans

Source: US Census Bureau Community Survey, 2005.

36 Three museums were analyzed: The Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit, MI (African Americans made up 70% of total attendance); the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History and Culture, in Baltimore, MD (80%); and the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, TN (60%).

37 Freelon Bond: Analysis of Existing Visitation prepared for the National Museum of African American History and Culture, March 2008.

33 Visitation Estimate | FREELON BOND

African

All Smithsonian Museums 9.0 National Museum of African Art 46.0 Anacostia Community Museum 85.0

American Attendance (Percentage)

13.2

Correspondingly, a significantly higher proportion of Jewish people and Native Americans visit the USHMM and the NMAI, respectively, approximately ten times the proportion of their population rate in the United States overall for each institution.

Table 16: Museum Attendance of Core Constituency Groups

* Source: American Jewish Committee, 2006.

** Source: A Comparison of Visitors to the National Museum of the American Indian to General Smithsonian Museum Visitors, Office of Policy & Analysis, April 2005.

*** Source: US Census Bureau, 2000, for persons identifying as “American Indian alone.”

The socioeconomic levels of local African Americans are also a factor in estimating African American attendance at the NMAAHC. African Americans living in the DC MSA have a higher socioeconomic level than their counterparts nationwide. These residents are 10% more likely than African Americans nationwide to have earned a college degree or higher. Per capita income is nearly two-thirds higher among DC MSA African Americans than it is among their counterparts nationwide.38 Given that the general museum-going audience is characterized by higher-than-average socioeconomic levels, this local constituency may have a significant impact on African American attendance rates at the NMAAHC.

The NMAAHC’s attendance will comprise a greater African American proportion than Smithsonian museums in general, especially considering the disproportionality of core constituents evident at the USHMM and the NMAI. Because of its broad national appeal, it will more likely approximate the proportion of African Americans attending the NMAfA than the Anacostia Community Museum. Even so, the NMAAHC aims to attract an audience interested in American history and culture through an African American lens—that is, a broader audience than at the NMAfA. Given these factors, as well as the large proportion of highly educated African Americans in the DC MSA, African Americans will likely make up 25–30% of total attendance at the NMAAHC.

38 US Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2006.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 34

Museum Core Constituency Nationwide Attendance Making Up Core Constituency USHMM* 1.78% 10.00% NMAI** 0.66%*** 6.00%

Mixed-Race Groups

Persons identifying as mixed race are of interest to the NMAAHC because at least some will possess African American heritage. Even among those who do not claim African American identity, there may be some who empathize with the cultural experiences of African Americans in the United States who were ostracized or imprisoned for engaging in interracial relationships with individuals subjected to historical taboos regarding interracial families. As mentioned earlier, recent studies have shown that younger people have exhibited an attitudinal shift toward accepting interracial relationships. Therefore, the population of mixed race individuals is likely to increase in the next 5–10 years as these individuals marry and start a family.39

The Smithsonian Institution estimates that 4% of its total attendance is made of individuals identifying as mixed race. By contrast, 2.04% of the general population identifies as mixed race.40 Because of the added relevance that the NMAAHC is likely to have for persons of mixed race, we estimate that mixed-race visitors will make up 4–8% of the museum’s total audience.

The Phase Two Report discussed the likelihood of persons with familial or friendship relationships associated with African Americans as being drawn to the NMAAHC.41 Included here are individuals who are members of interracial households as a result of marriage or adoption as well as persons with strong relationships and bonds outside of the home with members of other races. We believe that the NMAAHC will attract this group of individuals, who will be drawn by personal relevance to the exhibits at the museum. There is no readily available data on these individuals’ level of cultural participation. The only reliable estimate matches that provided for mixed-race individuals (a group that has been studied), who are likely to possess a strong affiliation with the themes and mission of the NMAAHC. The US Census Bureau reports that 1.07% of marriages in the United States are multi-racial.42 This represents almost half of the mixedrace proportion of the population. Therefore, these individuals may make up as much as 4% of the NMAAHC total visitation.

39 Smithsonian Institution, Office of Policy and Analysis, A Comparison of Visitors to the National Museum of the American Indian to General Smithsonian Visitors, April 2005.

40 US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2006.

41 Freelon Bond, Phase Two Visitation Audience Research: Market Analysis, May 2008.

42 US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2006.

35 Visitation Estimate | FREELON BOND

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 36

Visitation Cycles

SEASONALITY

An examination of all Smithsonian Institution museums by season for the years 2004–2007 reveals a consistent divide between the heavy seasons of summer and spring (33.9% and 31.8% of annual attendance, respectively), and the light seasons of winter and fall (14.4% and 19.9%, respectively). Variation is more apparent between summer and winter, with the winter season attracting the smallest proportion of visitors. Variations over the years can be accounted for both by museum-specific factors (e.g., a popular special exhibition, renovation/expansion schedule, etc.) and environmental factors (e.g., extreme weather conditions, consumer index rates, tourist activity, etc.)43

The NMAAHC’s seasonal visitation cycles are likely to adhere to the patterns seen among Smithsonian museums overall, with over 60% of visitors attending during the spring and summer and 34% attending during the winter and fall seasons. Opportunities to increase visitation during low attendance periods could involve special programs connected to themes such as Kwanzaa, Emancipation Day, Veteran’s Day, March on Washington, etc.

Table 17: Seasonal Distribution of Visitors

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Office of Protective Services, Visitor Counts 2004-2007.

Monthly rates of attendance can be estimated by looking at specific museums, both on and off the National Mall, and for Smithsonian Institution museums overall for fiscal year 2006. Research shows that within the heavy seasons of summer and spring, the greatest attendance occurs in the months of April and July. The National Cherry Blossom Festival is in April. This is also the month in which most public and private schools schedule spring break and when school groups and families embark on trips to the capital. July, the heart of the summer and a period of low precipitation in Washington, DC, is prime family vacation time.

The least-visited months for Smithsonian museums and Washington, DC, museums are January and February. February is Black History Month, a marketing and programming opportunity for African American museums and a time of heightened interest in African American subject matter generally. Whereas the NMAAHC is likely to mirror the trends of Smithsonian and Washington, DC, museum visitor cycles in general, we believe that it will experience a unique rise in attendance in February. Smithsonian Institution visitor counts research (see table 18) shows that the busiest months are likely to be April and July. The quietest month is likely to be January.

43 Smithsonian Institution, Office of Protective Services, Visitor Counts 2004–2007.

37 Visitation Estimate | FREELON BOND

Average SI 04–07 NMAAHC Projection Winter 14.4% 358,914 Spring 31.8% 795,936 Summer 33.9% 848,742 Fall 19.9% 496,408 TOTAL 100.0% 2,500,000

05

Table 18: Monthly Distribution of Visitors in a Steady State

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Office of Protective Services, Visitor Counts 2007.

With the exception of the winter months, ticketed visitors to the Washington Monument are relatively constant.44 This is likely due to the fact that the Monument is generally operating at capacity. The most interesting point about this for the NMAAHC is the number of visitors who are outside the Monument, possibly having been turned away due to lack of available tickets. Further study is recommended to understand the impact that ticketed and non-ticketed visitors to the Washington Monument will have on the NMAAHC.

VISITATION BY DAY OF THE WEEK

An examination of the days of the week for all of the Smithsonian museums shows that the majority of visitors—41%—visit during the weekend. Among the weekdays, Tuesday is the least-frequented day and Monday and Thursday compete for the most-frequented day. The NMAAHC is expected to generally adhere to this distribution, with over 40% of its visitors attending during the weekend.

Table 19: Projected Steady State Attendance by Day

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 38

Month All Smithsonian Institutions All Smithsonian Institutions (Adjusted to Include Black History Month) NMAAHC Projections January 4.3% 4.1% 102,500 February 4.3% 4.9% 122,500 March 8.3% 8.1% 202,500 April 13.8% 13.8% 345,000 May 10.9% 10.9% 272,500 June 10.3% 10.3% 257,500 July 13.7% 13.7% 342,500 August 9.0% 9.0% 225,000 September 5.6% 5.6% 140,000 October 7.0% 6.8% 170,000 November 6.5% 6.5% 162,500 December 6.3% 6.3% 157,500 TOTAL 100.0% 100.0% 2,500,000

All Smithsonian Museums for FY07 Day Percentage Sunday 17 Monday 14 Tuesday 5 Wednesday 10 Thursday 14 Friday 15 Saturday 24 Weekend 41 44 US Government Accountability Office, Report to the Chairman, Committee on Government Reform, House of Representatives, June 2005.

HOURLY VISITATION

In general, museums experience heavy attendance by school groups in the mornings, until about 1:00 P.M. An interview with the staff of the USHMM, an institution that issues tickets to its permanent exhibition that indicate the time the tour begins, confirms that the museum’s busiest times are the first two hours after opening.45

On the other hand, an interview with the NMAH confirms that the busiest times were in the afternoon, between 2:00 P.M. and 4:00 P.M. Table 20 details the distribution of hourly visitation.

Table 20: Hourly Visitation at National Museum of American History

Source: Personal Interviews.

The NMAAHC is expected to experience two waves of visitation on most days: the first will include those who have prioritized the NMAAHC as their first activity choice. School group visitation will also be much higher during the morning hours. The second wave will be in the afternoon and will include higher levels of wanderers and amenity seekers, and those who have chosen to spontaneously change plans.

39 Visitation Estimate | FREELON BOND

National

of American

Hours Total Yearly Attendance Percentage of Attendance 10 A.M.–11 A.M. 408,643 9 11 A.M.–12 P.M. 511,551 11 12 P.M.–1 P.M. 682,412 14 1 P.M.–2 P.M. 781,965 17 2 P.M.–3 P.M. 836,457 18 3 P.M.–4 P.M. 833,363 18 4 P.M.–5 P.M. 665,978 14 TOTAL 4,720,369 100

Museum

History

45 Paul Garver, interview by Manager of Visitor Services, USHMM, June 2008.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 40

Design Day Planning

DESIGN DAY EXPLANATION AND ESTIMATE