Protective

Design Standard s for Technical Security

REQUIREMENT

all Weapons container shall be protected in accordance with UL Safe partial protection with door contacts only. These sensors shall be annunciated through the alarm annunciation system.

all Safes shall be provided with door opening contacts and vibration detection.

all Exhibit security wiring shall be hardwired as shown on the drawings. Wiring shall be installed in a baseboard conduit and access box system. Access boxes shall be provided at 3000mm intervals around the perimeter of each gallery. Conduit shall be sized to accommodate two alarmed cases or a minimum of six pairs of wire per access box. Where an under floor wire duct system is provided, it shall accommodate partitioning for Class 2 alarm exhibit wiring.

all Intrusion devices of different technologies (i.e. motion detection, glass break or magnetic contacts) shall be zoned separately. Intrusion devices of like technologies shall be wired together within the confines of clear physical barriers, or, where barriers may be separated by great distances, at reasonable and regular intervals.

all Emergency power distribution shall be provided to allow the control room, associated equipment room, and security field devices to be powered from emergency generator power.

all All ATM machines should be outfitted with a common alarm output for connection to the facility security management system.

Smithsonian Institution - 17 -

SI Technical Standards Rev 8.doc

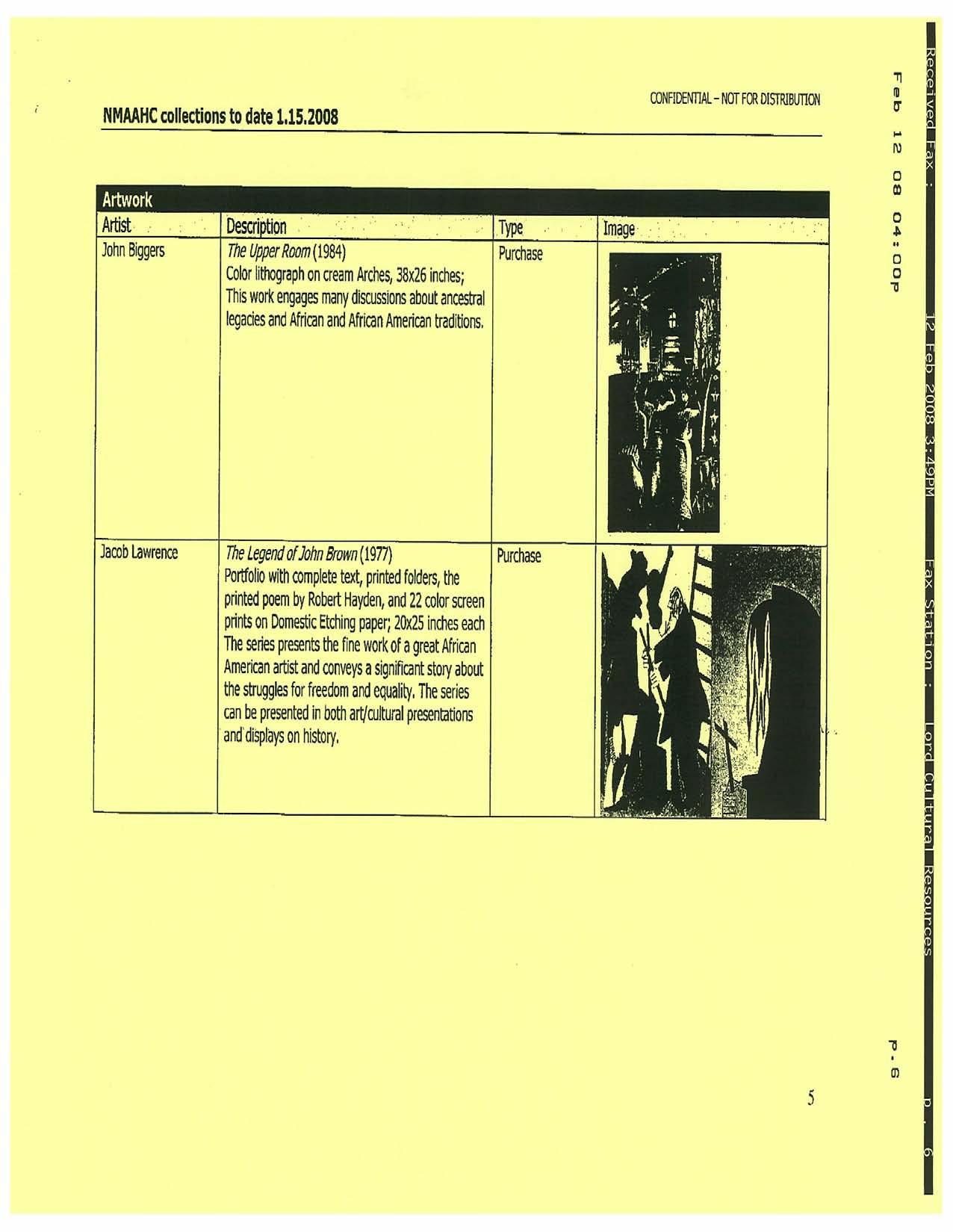

69 Appendix | FREELON BOND

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 70

E

Determining the Acceptable Ranges of Relative Humidity and Temperature in Museums and Galleries

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 72

Introduction

DeterminingtheAcceptableRanges of RelativeHumidity

And Temperature in Museums andGalleries

MarionF.Mecklenburg

Smithsonian MuseumConservationInstitute.

Part1,StructuralResponsetoRelativeHumidity

Ifoneisattemptingtointerpretthe temperatureandrelativehumidity(RH) information developedforSmithsonian Facilities Management (oranyinstitutionforthatmatter) itwould probablybemostusefultolookattherawdatafrommonitors ofindividualsites. Atthe Smithsonian, thecurrentenvironmentalguidelinesare45%RH+/- 8%RHand 70 o F+/- 4o Ffor exhibitionsandstoragespaces. (Mecklenburgetal,2004) Thissimplymeansitisacceptableto bewithinaRHandtemperatureboxboundedbetween37%RHand53%RHand66o Fand74o F.

Given that theactualdataistakenonanhourlybasisovera30 dayperiodonecanactuallysee theexcursioneventsintermsoftimeandmagnitude.Thisdatacanbeinterpretedinsuchaway thatitshowsboththeactualHVACsystemperformance andit allowsadetailedanalysisin termsofthewhetheranexcursionisactuallycausingproblemsforthecollections.Forexample, doesa4 hourdepressioninRHof4%-5%outsidethe allowable bandwidthhaveasignificant impactonthechemicalandstructuralstabilityofthecollection? Toanswerthatquestionone needs to knowwhat the actual, allowable , RHandtemperaturerangesareand toexaminethe timeittakesformoisture to enterorleavematerialswhenthereisachangeinrelativehumidity.

Beforediscussingtherateofmoistureabsorptionitwouldusefultoreviewsomefundamental issues. Thisincludes howtheguidelines were originally establishedandwhatwerethecriteria

73 Appendix | FREELON BOND 1

used? Anotherfundamental issue is how tointerpretthehourlymonitoringtemperatureand relativehumidity(RH)data.

SettingtheInitialCriteriaforEstablishingEnvironmentalGuidelines

Whenoriginallydeveloped, theenvironmentalguidelinesrequired criteri a fromwhichtowork. Forexampleifwoodorgluesamples wererestrainedanddesiccated,theywoulddevelop stresses.Thequestionsthatneededanswerswere; howmuchdepression orelevation inRH wouldbesufficienttocausefailureandhowmuch changecouldthematerial withstandwithout damage? Damagecanmeaneitherpermanentdeformationoractualcracking. Sinceitispossible todirectlyrelatehumiditychangesinamaterialunderrestrainttothemechanicalstressesand strainsdeveloped fromexternalloadingsources, itbecomespossibletodevelop criteriaforthe allowableRHfluctuations. (Mecklenburg andTumosa, 1996 )

Thisrequiresdeterminingthemechanicalpropertiesandthedimensionalpropertiesforthe materialsatdifferentlevelsofrelativehumidityandtemperature.

Thefirstcriterion establishedwas tosimplyassumethateverymaterialinthe SmithsonianInstitutioncollections was fullyrestrained fromdimensionalresponse Nowthisisnotnecessarilytrueinallcasesbutitestablishesaworstcaseconditionfor mostbutnotallofthecollections Atypicalexampleofconstrainedmaterialswouldbe woodveneerbondedcrossgrainedoverawoodsubstrate.

Thesecondcriterionisthattherestrainedmaterialsare initiallyfree ofstress . Exceptionswillbediscussedlaterinthispaper.

The third criterionselectedwasthatthemechanicalstrains ofthematerialcould never exceedtheyieldpointeitherintensionorcompression Theyieldpoint definesthe upperlimitof theelastic (reversible) regionof a material’smechanical performance

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 74 2

Loadingthematerialabovetheyieldpointinducesplastic(permanent)deformationinthe material.

Therehasbeensomeuncertaintyregardingthedimensionalbehaviorofhygroscopicmaterials anditwouldbeprudenttoshowwhatdoesoccurwithveryresponsivematerials.The rigid materialsthathavethemosthumidity-relateddimensionalresponsearetypicallywoods,glues, and ivory .Theflexiblematerialsthathavemoderatetohighdimensionalresponsetorelative humiditycanincludepapers,parchments,andtextiles. Materialsthatmightbeconsideredto havemoderatetolowdimensionalresponsetorelativehumidityincludegessoesandoil,alkyd, andtemperapaints. Forpurposesof clarifyingthedimensionalresponseofamaterialtomoisture changes itwouldbeusefultoexaminewood.

TheDimensionalResponseofWood

Overcenturies,woodhasbeenthematerialofchoicefor panelsupportsfortemperaandoil paintings,furniture,structuralsystems inbuildings andathousandotherthings . Itisstillused todayandisamaterialthatis very hygroscopic.Fromboththedimensionalandmechanical responsetorelativehumiditywoodissaidtobeorthotropic,thatisitrespondsdifferentlyinthe threeprimaryandmutuallyperpendiculardirections.Thosethreedirectionsarethelongitudinal directionwhichisthedirectionparalleltothegrainofthewood (L),theradialdirectionwhichis perpendiculartotheconcentricringsofwood (R) ,andthetangentialdirection (T) whichis tangent to theconcentricringsinwood (Fig 1)

Figure1alsoshowstheRH-relatedfreeswellingresponseinthethreeprimarydirections for modernScotchpine.Woodcutinthetangentialdirectionisthemostresponsiveandistobe avoidedwhenmakingpanelpaintings. Woodcutintheradialdirectionisbestforpanelpaintings sinceitistypicallylessthanhalfasresponsiveasthetangentiallycutwood. Theleastresponsive directionisthelongitudinaldirection. Whendryingoutwoodlogstendtocrack in theradial direction(Fig 2.) Ivoryontheotherhandismostresponsiveintheradialdirection.Thatiswhy

75 Appendix | FREELON BOND 3

ivorytendstocrackinconcentricringswhenexposedtoexcessivelylargechangesinmoisture content (Fig. 3).

NewScotchPine,TheThreePrimaryDirections

Figure1,theswellingresponsetolargechangesinrelativehumidityofwoodsamplesinthe threeprimarydirections for modernScotchpine.Themostresponsivedirectionisthetangential directionfollowedbytheradialdirection.Thelongitudinaldirectionisonlyminimally responsivetochangesinmoisturecontent.Thewoodsusedforpaintingstretchersandpanelsare best cutintheradialdirectionsincetheyexhibittheleastdimensionalresponsetochangesin relativehumidity.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 76 4

0 20 40 60 80 100 0 0.005 0.01 0.015 0.02 0.025 0.03 0.035 RelativeHumidity(%) F r e e S w e l l i n g S t r a i n s

R L T

Radial Tangential Longitudinal

Figure2shows thecracks alongtheradiiof asectionofDouglas firfromanAztecruin inN.M. datedA.D. 1240 . (Samplescourtesyof theLaboratoryofTree-RingResearch,TheUniversityof Arizona,Tucson.)

Figure3showstheconcentriccracksinamammothtusk.Thecracksformedinthismanner sincetheradialdirectionofthetuskistheweakestandthemostdimensionallyresponsiveto moisture.(PhotocourtesyofWikipedia)

77 Appendix | FREELON BOND 5

Figure 4 showstheswellingresponsetolargeandsmallchangesinrelativehumidityof17th centuryScotchpinegrown inthesameforestinNorwayasthemodernwooddiscussedinFig .1. Thetangentialdirectionshownisthemostresponsivedirectionandshowsentirelydifferent behaviordependingon both the directionand magnitudeofthechanges inrelativehumidity. Whenlookingatlargechangesinrelativehumidity,thehumidificationplotismuchlowerthan thedesiccationplot.Thisdifferenceinthepathsiscalledhysteresis.

Whenthereisamuchmoremoderatechangeinrelativehumidity,therateofdimensional responseismuchreducedandthepathsarealmostthesame. Theslopesoftheswellingplots shownaretheestimatedcoefficientsofmoistureexpansionasafunctionofrelativehumidity. Thevalueoftheslope forthelarge desiccating changeinrelative humidityis 0.00071/%RH. Theslopeofthedimensionalchangeforthesmaller range inrelativehumidityisconsiderably less, (0.000417/%RH ) This differenceinrates helpsexplainwhymanymaterialssurvive uncontrolledbutmoderateenvironmentalchanges.

17th.CenturyScotchPine,TangentialDirection

Intermediate(30%to65%RH)

Measurement(.000417/%RH)

RelativeHumidity(%)

Figure 4,theswellingresponsetolargeandsmallchangesinrelativehumidityof17 th century ScotchpinegrowninthesameforestinNorwayasthemodernwooddiscussedinFig 1.The tangentialdirectionshownisthemostresponsivedirection andshowsentirelydifferentbehavior dependingonthemagnitudeofthechangeinrelativehumidity.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 78 6

0 20 40 60 80 100 0 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.06

F r e e S w e l l i n g S t r a i n s (.00071/%RH)

Itiscriticaltonotethatmanyculturalmaterialsexperience hysteresisand different ratesof dimensionalresponse dependingonthemagnitudeofthech angesinrelativehumidity. These differences willbe illustratedintheplotsthatfollow.

EstablishingRHBoundaries Usingthe YieldPointCriterion forMaterialswithLarge DimensionalResponses

Thissectionofthediscussion willillustratehowRHbo undariesaredeterminedwhenusingthe yieldpointcriterion.Itwouldalsobeusefulto include someofthe materialshavingthe most RH-relateddimensionalresponse These materials includewood,hideglue,andivory.Allofthe examplesshownaretypicaloftheirgroupsofmaterials.Forexamplethecottonwoodillustrated belowisoneofthemostdimensionallyresponsiveofallofthewoods. Inmanywoodssuchas mahogany,teakand,redwoodsthedimensionalresponsetomoistureisconsiderablyless. When testing thedifferenttypesofanimalglues,bovine,porcine,sturgeonandthephotographic gelatins, itwasfound thatthedimensionalresponsetomoisture was nearlyidentical.Their mechanicalpropertiesdiffer largely intermoftheirstrengthbutallcanbeconsideredtobevery strongmaterials. Ivorycomesfromthetusks(modifiedteeth)ofmammalsandisstructurally similar regardlessofthesourcespecies.

Woods

Whenfirst evaluating anymaterial itis necessarytoexamine its mechanicalpropertieswhen exposedtodifferentlevelsofRH.Figure 5 showsthetensilestress -straintestsforcottonwoodin thetangentialdirection. Cottonwood, alsoknownasEuropeanpoplar, wasjustoneofmany woodstestedbecauseitwasusedextensivelyinEuropeanpanelpaintings. (Richardetal,1998)

Thetangentialdirectionofanywoodis themostdimensionallyresponsivetoRH and itisalso theweakest. Thehorizontalscale (Fig.5) isinunitsof strainwhichisthechangeinlength

79 Appendix | FREELON BOND 7

dividedbythesample originallength Theverticalscaleisinstresswheretheunitsarein poundpersquareinch(psi). Stressiscalculatedbytakingtheforce(load)appliedtothe sampleanddividingbythecross-sectionalarea ofthetestsample. Theendofthetestiswhere thematerialbreaks.Thestressreachedwhenthematerialfailsiscalledthestrengthofthe material.Thestrainreachedwhenthematerialfailsiscalledthestraintofailure.Theinitial strainof0.005showninthefigureistheinitialyieldpointanddefinesupperlimitoftheelastic orreversiblerangeofthewood.Whenthewoodisstrainedbeyondtheyieldpointitissaidto undergoplasticornon-reversiblebehavior. Themodulusofanymaterialsistheratioofthestress tostraininthe elasticregiononly.Itisameasureofthestiffnessorflexibilityofthematerial.

Oneofthemosttellingfeatures ofwood isthat forthe relativehumidity rangesshown,thereis not adramaticeffectonthemechanicalproperties.Thereisnosignifi cantstiffeningor embrittlementof thewoodatlowrelativehumiditynordoesitloosesignificantstrengthathigh the levelofrelativehumidity. Ingeneralwoodslosestrengthandbecomeveryflexibleatvery highlevelsofRH. SomewoodscanbecomequitestiffandbrittlewhentheRHreacheslevels below10%. Itis important tonote thelocationoftheyieldpointat0.005 inrelationtothe breakingstrainsthatrangefrom0.012toabout0.2.asshown Fig. 5. Thewoodmustbestretched considerably beyondtheyieldstrain beforeitactuallybreaks.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 80 8

0 0.005 0.01 0.015 0.02 0.025 0.03 0 200 400 600 800 Strain S t r e s s ( p s i ) 48% 5% 80% 23% 63% Failure

CottonWood,TangentialDirection

Yieldpoint

Figure 5 showsthetensilestress -straintestsforcottonwoodinthetangentialdirection.The tangentialdirectionofanywoodisthemostdimensionallyresponsivetoRHanditisalsothe weakest. The yieldpointisindicatedbythearrowatastrain0.005. Thisisconsiderablylower thanthestrainrequiredtocausethewoodtoactuallybreak.

Figure 6 shows thedimensionalresponseoftangentiallycutcottonwoodtobothlargeand intermediatechangesinrelativehumidity.TheintermediateRHrangesare still fairlylargeand easily exceed the recommended museumcontrol RHranges There is actuallyafamilyofthe intermediatedimensional response rangesandtwoofthemareshowninthisfigure.Also shown in this figureare theallowableRHfluctuationsiftheyieldpointof0.005hadbeenusedasthe criterionforenvironmentalRHlimits.

The allowable fluctuation sshown rangebetween32%RHand62%RHascomparedtothe guidelinesrecommendation of37%RHand53%RH. Thismeansthatthewoodisbehavingina fullyelasticandreversiblemannerinaRHrangegreater thantherecommendedmuseum guidelines.Italsomeansthatthechangeinrelativehumidityhastogreateryettocausethewood tobreak

Currentenviromental guidelines,45%+/-8%

Whatispossibleif allowedafullyieldstrain of+/-0.005

81 Appendix | FREELON BOND 9

0 20 40 60 80 100 -0.02 -0.01 0 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04 0.05 RelativeHumidity(%) F r e e S w e l l i n g S t r a i n s

CottonWood,TangentialDirection

Figure 6 showstheallowableRHfluctuationsiftheyieldpointof0.005hadbeenusedasthe criterionforenvironmentalRHlimits.Thesefluctuationsrangebetween32%RHand62%RH ascomparedtotheguidelinesrecommendationof37%RHand53%RH.

HideGlue

Hideglue isalsoaRH-responsivematerial and itispresentinnearlyallculturalcollections. Itis foundastheadhesiveforbondingpartsandveneersinwoodfurniture,itisusedasthesizein traditionalcanvaspaintingsandsomewatercolorpapers , anditisusedtomakegesso.When refined intogelatin, itisusedastheimageemulsioninphotographicmaterials.

Figure 7 showsthetensilestress-straintestsforhideglueatdifferentRHlevels. At lowRH levelsthematerialisstillductileandnotbrittle.Athighhumiditylevelshidegluelosesstrength and this is acriticalfactor inmoisturerelateddamagetopaintings .Theyieldpoint,thelimitof elasticbehavior, usedforalloftheplotsisindicatedbythearrow, atastrain of 0.005.Early failuresshowninthetestsat38%RHand67%RH, resultedfromdefectsinsamplepreparation. Butitisworth noting thatdefectscancauseprematurefailure. Never -the-lesstheultimate breakingstrainsarefarinexcessoftheyield pointstrainof0.005.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 82 10

0 0.02 0.04 0.06 0.08 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 12000 14000 16000 Strain S t r e s s , ( p s i ) 38%RH 51%RH 67%RH 78%RH 23%RH 18%RH Yieldpoint

Hideglue,75F

Figure 7 showsthetensilestress -straintestsforhideglueatdifferentRHlevels.Notethatat verylowRHlevelsthematerialisstillductileandnotbrittle.Athighhumiditylevelshideglue losesstrength.The initial yieldpoint,thelimitofelasticbehavior, usedforalloftheplotsis indicatedbythearrow, atastrain0.005.

Figure 8 showsthedimensionalresponseofhidegluetobothlargeandintermediatechangesin relativehumidity.TheintermediateRHrangesar easwiththe caseforthecotton woodstillfairly large Figure 8 alsoshowstheallowableRHfluctuationsforhideglueiftheyieldpointof0.005 isusedasthecriterionforenvironmentalRHlimits.Thesefluctuationsrangebetween30%RH and60%RH ascomparedtotheguidelinesrecommendationof37%RHand53%RH.Alsoas withthewoodtheallowableRHrangewhenusingtheyieldpointof0.005isconsiderablylarger thantheallowableRHrangeunderthecurrentSIguidelines. Aswiththecottonwood, thewider RHrangesarestillwithintheelasticregionoftheglueanditwilltakesignificantlywiderranges tocausethematerialtobreak.

Currentguidelines

Figure 8 showstheallowableRHfluctuationsforhideglueiftheyieldpointof0.005isusedas a criterion forenvironmentalRHlimits.Thesefluctuationsrangebetween30%RHand60%RH ascomparedtotheguidelinesrecommendationof37%RHand53%RH.

83 Appendix | FREELON BOND 11

0 20 40 60 80 100 -0.03 -0.02 -0.01 0 0.01 0.02 0.03

F r e e S w e l l i n g S t r a i n s 30%to60% +/-0.005

HideGlue,75F

RelativeHumidity(%)

Whendiscussingenvironmentalcontrol,oneofthematerialsthat generate themostcontroversy isivory. Theivoryusedintheseexperimentswasfromawalrustuskbut quitesimilarto ivory fromotherspecies. Inactuality,ivoryissomewhatlessresponsivethanmost woods.Figure 9 shows thetensilestress-straintestsforwalrustusk(ivory). Todemonstrateitsdurability,this materialwascycled reversiblyfor over5000cycleswithintheyieldrange.Theplotsshownare cycle2109 ofover5000cycles andthefulltesttofailure. Thatthecyclingoftheivorywas reversiblewithnoplastic (permanent) deformationindicatedthatallcyclingtestswere conductedbelowtheyieldpoint. Theyieldpointfor the ivory isindicatedbythearrowata strain0.005. Inordertocausefailurethematerialhad tobeextendedtoastrainlevelofabout 0.0095,almosttwicetheyieldstrain.Thesampletestedherewascut throughthecenter fromone sideofthe tusktotheother whichistheweakestandmostdimensionallyresponsivedirection.

Cycle2109ofover5000

Figure 9 showsthetensilestress -straintestsforwalrustusk(ivory) at48%RHand74o F. This materialwascycledover5000cycleswithintheyieldrange.Theplotsshownarecycles 2109 andthefulltesttofailure.Theyieldpointsusedforalloftheplotsisindicatedbythearrowata strain0.005.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 84 12 Ivory

0 0.002 0.004 0.006 0.008 0.01 0 500 1000 1500 2000 Strain S t r e s s ( P S I )

CyclingofCrossGrainWalrusTusk

Fulltesttofailure

YieldPoint

Figure 10 sh owsthedimensionalresponseof walrustusk tobothintermediate andlarge changes inrelativehumidity.TheintermediateRHrangesarefairlylarge. Figure 10 also showsthe allowable RHfluctuationsfor the walrustuskiftheyieldpointof0.005isused asthecriterion forenvironmentalRHlimits.Thesefluctuationsrangebetween 27%RHand68%RHas comparedtotheguidelinesrecommendationof37%RHand53%RH.

WalrusTusk,Tang./RadialDirection

AllowableUsing+/-0.005

RelativeHumidity(%)

Figure 10 showstheallowableRHfluctuationsforwalrustusk(ivory)iftheyieldpoin tof0.005 isusedasthecriterionforenvironmentalRHlimits.Thesefluctuationsrangebetween 27 %RH and68%RHascomparedtotheguidelinesrecommendationof37%RHand53%RH.

ReassessingtheSomeoftheInitialAssumptionsandCriteria

Uptothis point inthisdiscussion itwasassumed that theyieldpointwas astrain 0.005 andthat theinitialstressforthematerialzero. IndoingsoitispossibletoshowthattheallowableRH fluctuationsforthematerialsexceedthe museum guidelinebyaconsiderableamount.Ifthe actualfailurestrainofthematerialshadbeenused,thentheallowablefluctuationswouldhave beenevengreater. Clearlyunder selectedcriteria thereisalargemarginofsafetyinthe37% RH-53%RHguidelines.

85 Appendix | FREELON BOND 13

0 20 40 60 80 100 -0.02 -0.01 0 0.01 0.02 0.03

F r e e S w e l l i n g S t r a i n s +/-0.005

.000205Strain/%RH CurrentGuidlines

Actuallythemagnitudeoftheyieldstrains cananddoes dependtoaconsiderabledegree onthe environmentalhistoryofthematerial. Culturalmaterials “strainhardens ” inmuchthesameway assteels.Thatis,iftheyarestretchedbeyondtheirinitialyieldpointand thenunloaded (relaxed) theywillexhibitplasticdeformation(permanentdeformation)and besetpermanently toa differentandhigheryieldpoint Figures 11 and 12 showtheunloadcompliancetensiletestsof Americanmahoganyandhideglue.Bothofthese materialsstrainhardenanddevelophigher yieldstrainsmeaninganexpansionoftheelastic orreversible regionofthematerial.

Whenunloadedcompletely andthe stress iseliminated, theamountofplasticdeformationcanbe determinedbythedistance betweentheoriginalstartofthetestandthepointwherethestress returnstozero.Inotherwordsthematerialhas“re-initialized”toapointofnostressbutwith someplasticdeformation. Fromtheperspectiveofthechangesin theenvironment ,itwillrequire RHchangesconsiderablylargerthanthecurrentSIguidelinestocausethis.

Anyobjectmademorethan70yearsago,priortotheuseofmajorHVACsystemsin museums, has experiencedsignificant changes inbothtemperatureandrelativehumidi ty.Somuchsothat thereisaveryhighprobability thatenvironmental changes weresufficienttocausestrainsin excessoftheinitialyieldpoints. Thiscanalsobesaidforallmaterialsthattothisdayexist outsideofcontrolledenvironments. Insuchcasesthematerialsallexperiencedstrainhardening ineithertensionorcompression. In restrained woodswhenthehumidity gets veryhigh, this proces siscalled“compressionset” becauseoftheplasticdeformation.

Thepointhereisthatthe hardened yieldstrains are highlylikelytobefoundinthematerialsof olderculturalobjectsand arealwayslargerthantheinitialyieldpointof0.005 andthishas significantimplications

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 86 14

AM.MAHOGANY,48%RHUNLOADTEST

Figure 11 ,thestressstraintestofasampleofAmericanmahoganycutinthetangential direction. Thismaterial“strainhardens”, meaningwithexcessiveextension(strain)itdevelopsa largerelasticregionbutloosestheplasticregion.

2.5YearLongHideGlueTensileTests

Figure 12 , Trueequilibrium, load-unloadcompliance, stressstraintestof three samples of hide glueat50%RHand74o F. This particulartestillustrates strainhardeninganddevelopmentof newandlargeryieldstrainsofhidegluewhenloadedbeyondtheinitialyieldpoint.

87 Appendix | FREELON BOND 15

0 0.005 0.01 0.015 0 200 400 600 800 1000 Strain S t r e s s ( p s i ) Newstrain hardened yieldpoint Initialpoint strain=0.005 Newyieldpoint strain=0.007

0 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04 0.05 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 Strain S t r e s s ( p s i ) 0.008 Strainhardened yieldpoint Initialyieldpoint 0.005

When culturalmaterialsstrainhardenandtheela sticregionincreaseswithhigheryieldpoints the allowablefluctuationsinRHincrease.Forexampleifthehideglueillustratedin Fig. 12 had strainhardenedtothepointwheretheyieldpointwas0.008insteadof0.005thentheallowable RHfluctuationswouldincreaseto arangefrom28%to68% asshowninfigure1 3

HideGlue

Currentguidelines

Strainhardenedyield

Allowablewithstrain hardenedyield

Figure13 showstheeffectofstrainhardening ontheallowableRHrangeforhideglue. Nowthe allowableRHrangehasincreased tobetween28%and68%.

Thereisoneothercriticalassumptionthatnowneeds tobeaddressed.Thatassumptionisthat theinitialstressinthematerialsiszero. Let ’ssupposethatamaterial suchasthehideglue shownin Fig 14 hasaninitial strain of0.005 and stress of1255psi at45%RHand72o F.Sinc e itisalreadyrestrainedandloaded, anyloweringoftherelativehumiditywillincreasethe mechanicalstrainsandincreasethestress.

Lowering therelativehumidityfrom45%to 28%increasesthestrainanadditional0.008, to 0.013, wherethestress isapproximately3000psi. It’spossibleto illustrate thisonthesame stressstrainplotbecause ithas already been shown( Fig. 7)thatwhilethereissome,thereareno substantialchangesinthemechanicalpropertieswith respectto changesinRHin theregion underdiscussion.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 88 16

0 20 40 60 80 100 -0.03 -0.02 -0.01 0 0.01 0.02 0.03 RelativeHumidity(%) F r e e S w e l l i n g S t r a i n s 28%to68% +/-0.008

+/-0.005

30%to60%

2.5YearLongGelatinTensileTests

Initialyieldpoint

Effectofdecreasing theRHfrom35%to28%

Effectofreturningfrom 28%RHto45%RH

Figure14 showshowRHexcursionsareabletoreinitializeexistingstresslevelstonearzero values.Thisisaresultofbothplasticdeformationandstrainhardening.Thenewslopeofthe modulusistypicallyabithigher thantheoriginalinitialmodulus.

Upon returning totheoriginalRHlevelof45% one observes thatthestressdropstozero asseen in Fig 14 Forrestrainedmaterials, anysignificantexcursionfromoneRHleveltoanothercan alter(increase)theyieldpoint Ifthespecimenis alreadystressed(loaded),theexcursioncan also reinitializethestresslevelwhentheRHreturnstoitsoriginalsetting.

ConsideringthatnearlyallmaterialsfoundinculturalinstitutionshaveexperiencedRH excursion much greaterthanthe“recommendedguidelines” they have toonedegreeoranother actuallyinitializedthemselvestotheaverageRHsettings oftheircurrentenvironments .Itsimply cannotbeprevented.Accordinglyassumingthattheinitialstressiszerointhisdiscussionisnot unreasonable.

Ontheotherhandtherearetimeswherethematerialsremainunderfairlyhighstressanditis usefultoexplorethatcondition. Figure15shows thestresslevelsdevelopedinsamplesoftulip poplarwhenrestrained anddesiccated.Thesamplesarealltangentiallycut. Thesample desiccatedfrom85%RHto15%RHisbendingoverindicatingthatsomeplasticdeformationis

89 Appendix | FREELON BOND 17

0 0.005 0.01 0.015 0.02 0.025 0.03 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 Strain S t r e s s ( p s i )

occurring. Thesampledesiccatedfrom80%RHto20%RHfollowsnearlythesamepathwhen decreasingandincreasingtherelativehumidity.Thisindicatesthatthewoodisactinginanearly fullelasticbehavior.Thisindicatesthattheinitialyieldpointisconsiderablyhigherthanthe estimated0.005.Thesampledesiccatedfrom58%RHto7%RHisa ctinginacompletelyelastic manner.Noneofthesamplesfailedinthesetests.Evenwithveryhighexistingstresses, restrainedwoodscansafelyfluctuateinwideRHbands.Fromabout60%RHto10%RHthe processiscompletelyelastic(reversible).This indicatesthattheinitialyieldpoint , estimatedat 0.005,isveryconservativeandconsiderablyhigher. Thisbehavioralsofallswithinthe requirementthatthereisneitherpermanentdeformationnorfailure.

TulipPoplar,restraineddesiccationtests

Figure15 showsthestresslevelsdevelopedinsamplesoftulippoplarrestrainedanddesiccated. Thesamplesarealltangentiallycut. Thesampledesiccatedfrom80%RHto20%RHfollows nearlythesamepathwhendecreasingandincreasingtherelativehumidity. Thisindicatesthat thewoodisactinginanearlyfullelasticbehavior.Thisindicatesthattheinitialyieldpointis considerablyhigherthantheestimated0.005

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 90 18

0 20 40 60 80 100 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 RelativeHumidity(%) S t r e s s ( p s i )

Laterinthispaperwewillexaminethosecaseswherethereisexistingstressinthematerials.

Examplesof OtherMaterials

Someofthematerialsfoundinculturalinstitutionscantrulybeconsideredbrittle.Thismeans thatthereisverylittle, ifanycapacityforplasticdeformation.Inthesecasesthematerialsoften actasiftheyarecompletelyelastic.Oneotherfeatureofthesetypesofmaterialsisthatthewill breakwithverylittledeformationorintermsofmechanicsthestraintofailureisextremely small.

Someofthesematerialsincludegessoes and somebrittlepaintssuchasold(andevensomenew) oilpaintsanddegradedmaterialssuchasdeterioratedpaper. Whileitisimpossibletolookat everymaterialfoundincollectionsatthistime,fewhavegreaterdimensionalresponsesthan woods,glues,andIvory.Thosematerialsthataresomewhatresponsivesuchaspaper, parchment,andtextilestendtobeexhibitedin such amanner thatthereislittlerestraint andor theyare bufferedbyframingtechniquesandexhibitioncases.

Inthissectionwewilldiscussgessoandoilpaints.Paintssuchastheacrylicsareextremely flexibleinnormalroomtemperatureenvironments.Enamelscanin many respects fallunderthe categoryofoilpaints. Thealkydpaintscanalsobeplacedinthecategoryofoils,notbecause theyarethesamechemicallybutbecausetheyhavesimilarifnotbetterpropertiesthantheoils withrespecttorelativehumidity.Paintssuchasthebutyrateandnitratedopesusedonthefabrics ofearlyaircraftareextremelydurableasevidencedbytheirabilitytowithstandoutdoor environmentsforconsiderableamountsoftime.Themostseriousproblemwithoil,alkydand acrylicpaintsistheirsusceptibilityto damageby lowtemperature and willbediscussedinsome detailinthesectionontemperatureeffects.

91 Appendix | FREELON BOND 19

Traditionalgessois amixtureofwater,rabbitskin(hide)glueandaninertmaterialssuchas calciumsulfate(gypsum).Otherinertmaterialsusedwerecalciumcarbonate(chalk)andground marbledust.Inmorerecenttimestitaniumdioxidepigmenthasbeenused.Traditionallygesso wasappliedasasolutionontowoodpanelspriortopainting.Whendryitprovid ed asmooth absorbentsurface.Thiswasparticularlyeffectivewhenpaintingineggtempera. Insomeofthe traditionalrecipesforgessomolasseswasaddedtoimprove itsflexibility.

There were some gessoes used in canvaspaintingbutthematerialprovedtobetoobrittle.Other typesofgessoescalledboleswereusedtoprepareframesforgilding. Theinertmaterialusedin gildingwasclaycalledgilder’sclaybut rabbitskingluewasstillused.Whileclaycanbesome whatresponsivetomoisturethemostactivematerialwasstillthehideglue.

Boththedimensionalresponseandthemechanicalpropertiesofgessodependonthestrengthof thehideglueusedandtheratioofgluetoinertmaterials.Thatratioisusuallydescribedinterms ofthepercentpigmentvolumerationorPVC.Thehigherthevolumeofinertmaterial(orPVC) themorebrittlethegessoandlesstheresponsivetomoisturewithrespecttodimensional changes. Ingeneralstiffandbrittlegessoes willhavelittledimensionalresponsetochangesin relativehumidity.ThemechanicalpropertieswillchangesignificantlyhoweverwhentheRH levelsarechanged. (Mecklenburg,1992)

Figures16 and1 7 s howthemechanicalpropertiesofgessoesmadewithhideglueandcalcium carbonate.Gesso10A,shownin Fig. 16 showsreplicatedtestsofagessoatthreedifferentlevels ofRH,16%,49%and96%.Thepigmentvolumeconcentrationof thegesso is71%.From 49% RHto16%RHthemechanicalpropertiesarefairlysimilarbutasisshownthestraintofailureis veryclosetoourassignedyieldstrainwhentheRHisat16%.At96%RH,thestrengthofthe gessoisgreatlydiminishedbutitremainsquiteflexible. At moderatetovery lowhumidity levels gessocanbeconsideredtobenearly brittle.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 92 20 Gessoes

Figure17 showsthemechanicaltestsgesso10B atthreedifferentenvironments,17%RH,55% RH,and84%RH.Thepigmentvolumeconcentrationofthisgessois71%but16% molasses (by weight) wasaddedtoactasatraditionalplasticizer.Theadditionofthemolasseshasseveral effects.Thegessoisnowweakerthanthegessowithoutthemolasses.Itismoreresponsiveto thechangesinrelativehumidity.Forexamplethe samplestestedat17%RHaremuchstiffer than gesso10Aandfailsatastrainof0.004whichisbelowtheassignedyieldstrain.Atthemid rangerelativehumidity levels, thesamples aremoreflexibleandthestraintofailureisgreater thangesso10A.

Figures 16 showsthestressstraintestsforreplicatedsamplesof Gesso10A atthreedifferent environments.Thegessowas madewithhideglue with gram strength of251 andcalcium carbonate.ThePVC ofthegesso was71 %. (DatacourtesyofDr.LauraFusterLopez)

93 Appendix | FREELON BOND 21

0 0.005 0.01 0.015 0.02 0.025 0.03 0 200 400 600 800 Strain S t r e s s ( p s i ) 96%RH 16%RH 0.005 49%RH

Gesso10A,75F

Gesso10B,75F

Figure 16 showsthestressstraintestsforreplicatedsamplesofGesso10Batthreedifferent environments.Thegessowasmadewithhidegluewith gram strengtho f 251 andcalcium carbonate.ThePVCofthegessowas71%. Gesso10Bhasasadded16%(byweight)molasses. (DatacourtesyofDr.LauraFusterLopez)

AtthehigherRHlevelof84%,gesso10Bhasnearlylostallofitsstrength.Atevenhigher humidityaround90%thismaterialwilllooseallstrength.Clearlyoneneedstostayinthe mid rangeRHforthismaterial.

Itisnownecessarytodeterminetheallowablehumidityranges.Figure 18 showstheallowable RHfluctuationsfor Gessoes10Aand10B iftheyieldpointof0.005isusedasthecriterionfor environmentalRHlimits.These fluctuationsrangebetween 18 %RHand 73%RHascompared totheguidelinesrecommendationof37%RHand53% RH. ThiswideallowablerangeofRH occurssimplybecausethedimensionalresponsetochangesinrelativehumidityissolow.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 94 22

0 0.005 0.01 0.015 0.02 0.025 0.03 0 200 400 600 800 Strain S t r e s s ( p s i ) 84%RH Contains16%molassesbyweight 0.005 55%RH 17%RH

Currentguidlines

Figures 18 showstheallowableRHfluctuationsforGessoes10Aand10Biftheyieldpointof 0.005isusedasthecriterionforenvironmentalRHlimits.Thesefluctuationsrangebetween 18%RHand73%RHascomparedtotheguidelinesrecommendationof37%RHand53%RH. Gessoes10Aand10Bweremadewiththehideglueandcalciumcarbonate.ThePVCwas71%. Gesso10Bhasasadded16%(byweight)molasses. (DatacourtesyofDr.LauraFusterLopez)

Asbefore,itwasassumedthattheinitialstressatthesetpointRHof47%waszero.Thismight betrueforpanelpaintingsthathadbeensubjectedtolargeenvironmentalswingsin their history butwhataboutnewerpaintings andthosethathaveahistoryofmoderateenvironments.

Supposethatwetakedifferentsamplesofgesso, addingtotheonesalreadydiscussed,restrain themandsystematicallydesiccatethem Inthiswayitispossibletoactuallymeasurethestresses developedbutalsoillustratetheRHrangesthatareactuallypossiblewithoutcausingthe specimenstobreak.

Figure 19 showstheresultofconductingsuchatest. Thegessosamplesusedaredescribedas follows.

95 Appendix | FREELON BOND 23

0 20 40 60 80 100 -0.03 -0.02 -0.01 0 0.01 0.02 0.03 Relativehumidity(%) F r e e S w e l l i n g S t r a i n s

Gessoes10Aand10B

Gesso10B

+/-0.005

Gesso10A

Gesso10A, W&Hhidegluecalcium,carbonate,PVC=71%

Gesso10B, W&Hhidegluecalcium,carbonate,PVC=71%,16%Molasses

Gesso11A, Bjornhide gluecalcium,carbonate,PVC=75%

Gesso11B, Bjornhidegluecalcium,carbonate,PVC=75%,16%Molasses

Gesso12A, Bjornhidegluecalcium,carbonate,PVC=69%

Gesso12B, Bjornhidegluecalcium,carbonate,PVC=69%,16%Molasses

The gessosamples wereallrestrained at70%RHanddesiccateincrementally .Ateach incrementofRH they acquired equilibrium andthestresslevelsrecorded.Asdesiccation proceeded thestressincrease d inthegessosamples. Atabout18%RHthetestisreversedinthat thehumidityisnowincreased.Asthehumidityincreasesthestresslowers. At45%RH,our museumsetpoint,allofthegessosamplesalreadyhavesignificantstresslevels.Soourinitial assumptionthatthestressesneedtobezeroisnotnecessarilyrequired. Whatisextremely significanthereisthatthedownwardstresspathsare nearly identicaltotheupwardstresspaths. Thismeansthatthegessosamplestested areallexhibitingnearlyfullelasticbehaviorwithout anyplasticdeformation.Thisinturnmeansthattheoriginalassumptionthattheinitialyield strainforthegessowas0.005wasinaccurate,itisactuallymuchhigher.

Itisalsoofsignificancethatnone ofthespecimensbroke duringthistesteventhoughthe relativityhumidity rangewas from70%RHto18%,whichisclearlywaybeyondthecurrent museumenvironmentguidelines.Thisformofrestrainedtestingwillbeexamined withother materialsasthisdiscussionproceeds.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 96 24

GessoRestrainedTests

Figure19 showsthetestresultsof6differentgessosampleswhenrestrainedanddesiccated.In thistest,stressincreasesasthehumidityislowered.Samples11Aand11B,thegessoeswiththe highestPVC(75%)havethelowesthidegluecontentand aretheleastresponsivetoRH. (Data courtesyofDr.LauraFusterLopez)

Therecanbenoquestionthatintheearlypanelpaintingsthegessolayerwastheweaklinkin thestructure. Inthe15 th centurywherebotheggtemperaandoilpaintswereused, atypicalwood panelpaintingconstructionwasmultilayered.Theprimarysupportwaswood,thenalayerof hideglue,possiblyalayeroffabric,agessolayerandthenthecoloreddesignlayersandpossibly gilding.Figures 20 – 23 showbothtemperaandoilpanelpaintingsanddetailsofpaintingsfrom the15th century.In bothcasescracksappearinthedesignlayers.Whatisofinterestisthese cracks originatedinthegessolayersofbothpaintingsandthatthecracksare primarily perpendiculartothegrainofthewoodpanels.

Thismeansthatthewoodpanelandgesso arerespondingindependentlytotheenvironmental changesinmoisture.Ithasalreadybeenshownthatthewooddoesnotsignificantlychange dimensionallyinthedirectionparalleltothegrainandinthiscaseitisactingasarestraintto the dimensionalchangeinthegessolayersofthesepanelpaintings.Since thegessolayersare

97 Appendix | FREELON BOND 25

0 20 40 60 80 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 Relativehumidity(%) S t r e s s ( p s i ) 10A 10B 11A 11B 12A 12B

restrainedindirection paralleltothegrainofthewood andhasbeensubjectedtofairlylargeand uncontrolledchangesinambientrelativehumidity thegessocracks.These paintingsare excellentexamplesofhowonematerialinthepaintingcanrestrainanother. Ontheotherhand thewooddoesmovewithmoisturechangeinthedirectionperpendiculartothegrainofthewood andwhendesiccationoccurs,theshrinkingofthe woodrelievesthestressesandstrainsinthe contractinggessolayers limitingcrackingparalleltothegrain ofthewood

Figure 20 ,GentiledaFabriano,Marchigian,c.1370 -1427, MadonnaandChildEnthroned,c 1420,Temperaonpanel,3711/16in.x 22¼in.(95.7x56.5cm),SamuelH.KressCollection,

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 98 26

1939.1.255 (Courtesyofthe NationalGalleryofArt,Washington,D.C.)

Figure 21, detail,showingcrackslargely perpendiculartothegrainofthewoodsupport.Gentile daFabriano,Marchigian,c. 1370-1427, MadonnaandChildEnthroned,c1420,Temperaon panel,3711/16in.x22¼in.(95.7x56.5cm),SamuelH.KressCollection,1939.1.255. (courtesyofthe NationalGalleryofArt,Washington,D.C.)

Figure 22,FraLippoLippiandworkshop,Flo rentine,c.1406-1469, TheNativity,probablyc 1445,oilandtempera(?)onpanel,91/8in.x21¾in.(23.2x55.3cm),SamuelH.Kress Collection,1939.1.279.(courtesyofthe NationalGalleryofArt,Washington,D.C.)

99 Appendix | FREELON BOND 27

Figure 23, detailshowingcra cksperpendiculartothegrainofthewoolpanel.FraLippoLippi andworkshop,Florentine,c.1406-1469, TheNativity,probablyc1445,oilandtempera(?)on panel,91/8in.x21¾in.(23.2x55.3cm),SamuelH.KressCollection,1939.1.279 .(Courtesy ofthe NationalGalleryofArt,Washington,D.C. )

Thereareotherobservationstobemade.Oneisthatthereislittlecrackinginthepaintlayers independentofthegessolayers.Eggtemperaformsaverytoughfilmresistanttobothmoisture andcleaningsolvents.SeeminglyintheFralippoLippi (figures21-21) theoilsare demonstratingasimilartoughness. Finallythequestionthatneedsaskingis:whatwerethe environmentalchangesthatoccurredtocausesuchcrackinginthesepaintings?Fromthe researchabovethechangehadtohavebeengreaterthanfrom70%RHto20%RHandit probablywasmoreintheorderof85%to25%.

OilPaints

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 100 28

Oilpaintsarecomplexinthatthedifferentpigmentscausepaintstodryhavingverydifferent RH-related mechan ical anddimensional properties. Somepigmentswhenaddedtodryingoils formverydurablepaintswhileotherssuchastheearthcolorpigmentsformweakpaints. In additionoilpaintsmadewiththewhitepigments,basicleadcarbonate,titaniumdioxide,and zincoxideareverydimensionallystable.Ontheotherhandthosepaintsmadewiththeearth colors,suchasochre,umber,andSiennagetfairlyresponsivewhentherelativehumidity exceeds60%.Thisisaresultoftheswellingofnaturalclaysfoundinthesepigments.Itwillbe usefultoexaminesomeofthesepaints

Figure 24 showthestressstrainresultsfordifferentpaintsafterdryingforatleast12yearsina controlledenvironmentof40%-50%RHand23o C. Becauseofhydrolysis,thepaintsmad ewith theearthcolorsdevelopverylittlestrengthandstiffnessevenafter12.25yearsofdrying.The paintsmadewithtitaniumwhiteandbasicleadcarbonatehavenearlythesamemodulus (initial stiffness) butthetitaniumwhitehaslittlestrengthanditsextensionbarelyreachestheyieldpoint of0.005(0.5%elongation).Thetitaniumwhitecanbeconsidereda weakand brittlepaint.The paintmadewiththezincoxidehasdevelopedaveryhighmodulusandwhileithasdevelopeda highstrength,itis averystrong, brittle paint havingabreakingstrainofonly0.003(0.3% elongation).Thepaintmadewithmalachiteisincludedtoillustratetheeffectsofpigments containingcopper compounds

Paintstestedat48%RH,75F

101 Appendix | FREELON BOND 29

0 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04 0.05 0 200 400 600 800 Strain S t r e s s ( p s i ) Titaniumwhite 14.5Years YieldPoint Rawumber,12.25years Basicleadcarbonate 14.25years Coldpressedlinseedoil Zincoxide 14.5years Malachite 12.25years Yellowochre,12.25years

Figure 24,theresultsofstressstraintestsconducted ofpaintsmadewithdifferentpigments.As canbeseenthedifferentpigmentshaveadramaticeffectonthemechanicalpropertiesofoil paints.Itmustbenotedthatpigmentvolumeconcentrationscanalsohavesimilareffectsbut thesedataarearesultofthedifferentpigments.

Itisnecessarytounderstandthatwhilethestrengthofpaintisimportantitsabilitytoelongate (itsflexibility) isoffargreaterimportance.Itdoesn’ttakeagreatdealofforcetocrackthinpaint filmseventhoughthey haverelativelyhighstrength Itwouldbeusefultolookatsomeoilpaints madewithdifferentpigments.

Figure 25 showsthetensilestress -straintestsofapaintmadebygrindingbasicleadcarbonatein coldpressedlinseedoil.Thispaintwouldbetypicalofapaintmadeseveralhundredyearsago, thatis withouttheadditionofanymoderndriers,stabilizers,orinertbulkingmaterial.Asshown inthisfigure,thepaintisgettingstronger(greaterstressatbreak)asthetimeofdrying continues,andthereisamodestreductioninthestrain( elongation)atthepointoffailure.The strains tofailure inthi s paint arefairlyhighand itis stillquiteflexibleafter14.25yearsof drying.Onepointofinterestisthatthepaintshowsacontinualincreaseinstrengthoverthistime period.Thismeansthatwhateverchemicalprocessesthataffectthemechanicalpropertiesofthis paintarestillcontinuing

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 102 30

Leadwhiteincoldpressedlinseedoil,23C,50%RH

0.18Yearsold

Figure 25 showsthestressversusstrainplotsofbasicleadcarbonatepaintmadewithcold pressedlinseedoilatdifferentages.Evenafter14.25years,thepaintisstillgaininginstiffness andstrength.Theseplotsindicatethattheprocessesthatcausetheincreaseinstiffnessand strengthshowlittleindicationofslowingdown.

Figure26 shows thetensilestress-straintestsfor whitelead(basicleadcarbonate)groundincold pressedlinseedoil atdifferentRHlevels.NotethatatverylowRHlevelsthematerialisstill ductileandnotbrittle.Athighhumiditylevels the paint looses some strength butincreasesin flexibility.Theyieldpointusedforalloftheplotsisindicatedbythearrowatastrain0.005. As withothermaterialspaintalsostrainharden.Whiteleadoilpaintisaverydurablepaintandthis showsinactualpaintingssubjectedtoveryadverseenvironmentalchanges.

103 Appendix | FREELON BOND 31

0 0.02 0.04 0.06 0.08 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 Strain S t r e s s ( p s i ) 0.27Yearsold 0.98Yearsold 10.0Yearsold 0.005strain 14.25Yearsold

Figure 26 showsthetensilestress-straintestsfor whitelead(basicleadcarbonate)groundin coldpressedlinseedoil atdifferentRHlevels.NotethatatverylowRHlevelsthematerialis still ductileandnotbrittle.Athighhumiditylevels thepaint looses some strength butincreases inflexibility.Theyieldpointsusedforalloftheplotsisindicatedbythearrowatastrain0.005. Aswithothermaterialspaintalsostrainharden. (N/Fme annottofailure)

Figure27 showstheallowableRHfluctuationsfor leadwhiteoilpaint iftheyieldpointof0.005 isusedasthecriterionforenvironmentalRHlimits.Thesefluctuationsrangebetween 0%RH and 100 %RHascomparedtotheguidelinesre commendationof37%RHand53% RH. Itisthe goodmechanicalpropertiesandthelowdimensionalresponsetomoisturethatexplainsthe durabilityofleadwhiteoilpaint.Whentheleadbasedpaintswerereplacedwithotherwhites duetotoxicityissues,thecommercialreplacementwhitesincludedoilpaintsmadewithmixtures oftitaniumdioxideandzincoxideorzincoxidealone.Bothofthesecommercialoilpaint exhibitbrittlenessandlowdimensionalresponse.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 104 32 15yearoldwhiteleadincoldpressedlinseedoil 0 0.005 0.01 0.015 0.02 0.025 0.03 0.035 0 200 400 600 800 Strain S t r e s s ( p s i ) 52.1%RH,22.7C

96.5%RH,23.12C,N/F 14.6%RH,23.4C

YieldPoint

10yearoldwhiteleadincoldpressedlinseedoil

Figure 27 showstheallowableRHfluctuat ionsfor leadwhiteoilpaint iftheyieldpointof0.005 isusedasthecriterionforenvironmentalRHlimits.Thesefluctuationsrangebetween 0%RH and 100 %RHascomparedtotheguidelinesrecommendationof37%RHand53% RH.

LookingatExtremelyBrittlePaints

Ifoneexaminesfigure 24 closelyitiseasilyseenthatoilpaintsmadewithzincoxideortitanium dioxideareextremelybrittle.Somuchsothatthestrainsatfailureareeitherattheyieldpoint (titaniumwhite)orbelowtheyieldpoint (zincwhite).Inthesecasesitmightappearthatthese materialscouldbeconsideredlimitingfactors whenestablishingRHboundariesformuseums.

Howeveroilpaintsmadewitheithertitaniumorzinchaveextremelylowdimensional response rates tomoisture.Figure2 8 and2 9 illustratethis. Inthecaseofthetitaniumwhitepaintifone uses strainlimitsof+/- 0.002insteadoftheyieldstrainof+/ - 0.005 therewouldstillbea largeallowableRHrangebetween28%RHand 66%RH asshowninfigure28

Inthecaseoftheoilpaintmadewiththezincoxidetheallowablerangewouldbe from 17 %RH to63%RH iftheallowablestraincriterionof only +/- 0.002wereusedinsteadofthe+/ - 0.005 asshownin Fig. 29

105 Appendix | FREELON BOND 33

0 20 40 60 80 100 -0.03 -0.02 -0.01 0 0.01 0.02 0.03 RelativeHumidity(%) F r e e S w e l l i n g S t r a i n s CurrentGuidelines +/-0.005 Allowablerangeusing+/-0.005

20yearoldtitaniumwhiteinsaffloweroil

Currentguidelines

Allowablerange usingonly+/-0.002

Figure28 showstheallowableRHfluctuationsfor titaniumwhite oilpaint ifthe straincriterion ofonly+/- 0.002andnotthe yieldpointof +/- 0.005 are used . These allowable fluctuations rangebetween 28 %RHand 66%RHascomparedtotheguidelinesrecommendationof37%RH and53% RH.

20YearZincWhiteOilPaint

CurrentGuidelines

fluctuationswith Astrainof+/-0.002

RelativeHumifity(%)

Figure 29,theswellingresponsetolargechangesinrelativehumidityof20yearold zinc white paint groundinalkalirefinedlinseed oil.Aswiththeotherwhitepaintsshown,thereisverylittle dimensionalresponsetochangesinRH.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 106 34

0 20 40 60 80 100 -0.03 -0.02 -0.01 0 0.01 0.02 0.03

F r e e S w e l l i n g S t r a i n s +/-0.002

RelativeHumidity(%)

0 20 40 60 80 100 -0.03 -0.02 -0.01 0 0.01 0.02 0.03

F r e e S w e l l i n g S t r a i n s

+/-0.002

AllowableRH

Figure 30 shows themechanicaltestresultsofpaintsmadewiththepigmentsrawumberand yellowochreat1.25yearsand12.25years.Wherethewhiteleadpaintincoldpressedlinseedoil continuetostiffenovertheyears(figure25),thesetwopaints(andoilpaintsmadewithburnt umber)showanincreaseinstiffnessuptoaround1.25yearsandatsomepointthereafterthe paintsproceedtoloosethatearlystiffness.At12.25yearsthepaintsaretruefilmsbuttheyare extremelyweakandtheyhavelostsomeoftheir abilitytoelongate.Thereasonthisishappening isbecausethesepaintsarebecominghydrolyzedbymoistureintheair (Mecklenburgetal,2005 andTumosaetal,2005)

Hydrolysisisoccurringveryearlyinthesepaint’sdryinghistoryandinspiteof thefactthat thesepaintshavebeenmaintainedinaverybenignenvironmentof23o Cand40%-55%RH.

Paintstestedat48%RH,23C

Figure 30 showsthemechanicaltestresultsofpaintsmadewiththepigmentsrawumberand yellowochreat1.25yearsand12.25years.Wherethewhite leadpaintincoldpressedlinseed continuetostiffenovertheyears(Fig. 25),thesetwopaintsshowanincreaseinstiffnessupto around1.25yearsandatsomepointshortlythereafterthepaintsproceedtoloosethatearly stiffness.At12.25yearsthepaintsaretruefilmsbuttheyareextremelyweakandtheyhavelost theirabilitytoelongate. Thisis occurring becausethesepaintsarebecominghydrolyzedby moistureintheair

107 Appendix | FREELON BOND 35

0 0.02 0.04 0.06 0.08 0.1 0 1 2 3 4 Strain S t r e s s ( M P a )

Yellowochre,1.25years

Rawumber,12.25years

Coldpressedlinseedoil(CPLO)

Yellowochre,12.25years

Rawumber,1.25years

Thepaintsmadewiththeearthcolors tendtobe lowinstrengthat50% RH andh igherhumidity, above 70%, seriouslydegradetheirstrengthfurther. Itisbecausethesepaintsasweakthatthey areeasilydamagedbysolventsinthecleaningofpaintings. Neverthelessthepaintsmadewith theearthcolorscanwithstandanallowableRHrangeofbetween3 0%and6 4% asshownin F ig 31

20yearoldyellowochreinlinseedoil

Currentguidelines

AllowableRHrangewith strains+/-0.005 +/-0.005

RelativeHumidity(%)

Figure 31 shows theallowableRHfluctuationsfor yellowochreoilpaint if using a yieldpoint criterion of +/- 0.005 is used for establishingthe environmentalRHlimits.Theseallowable fluctuationsrangebetween 30%RHand64%RHascomparedtotheguidelines recommendationof37%RHand53%RH.

InteractiveBehaviorinCompositeStructures andtheEffectsofhighRH

Insomeways, simplestcompositestructureispaintedwood. Theillustrationsofsomeofthe behaviorofwoodpanelpaintingsshownin Figs. 20-23 demonstratetherestraintofwoodon gesso. Forthosepanelpaintingshavingoilgroundsandoildesignlayers thesame dimensional parametershold.Thatis; constraintinthedirectionofthegrainandreleaseofstressesandstrains perpendiculartograin. Certainlyoilpaintingsonwoodcanhavecrackingbuttherealquestionis

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 108 36

0 20 40 60 80 100 -0.03 -0.02 -0.01 0 0.01 0.02 0.03

F r e e S w e l l i n g S t r a i n s

whatwasresponsible, thepaintorthewood? Inmostcaseswherethepaintisdamagedbythe wooditis discerniblesincethecracksinthepaintlayerareparalleltothegrainofthewood.This makessensesincethewoodmovesthemostindirectionperpendiculartothegrain.Buttodo thatthewoodhastomovealotandthisrequiresverylargechangesinrelativehumidity.

Inthosecaseswherepaintcleavesintentsparalleltothegrainofthewood,excessivelyhigh humidityandrestraint tothewoodhastohaveoccurred.Athighhumidityandwhenrestrained thewood“compressionsets”andbecomessmallerthanbefore.Ondryingoutthewoodshrinks leavinglessroomforthedesignlayercleaved offinridges.

Butconsiderthecasewherethereis totalconstraint ofthesupport inalldirectionswhen consideringchangesinrelativehumidity.Suchacaseistheoilpaintingoncopper.Suchtotal restraintisrareforthereissomemovementof wood even inthelongitudinaldirection. Copperis totallyunresponsive (dimensionally) tochangesinmoistureyetoilpaintingsoncopperaresome ofthemostdurablepaintingsexistingtoday asseeninthepainting by JanvanKessel in F ig 32

“And,asartistsbeginningwithLeonardodaVinci(Italian1452-1519)suspected, paintingsoncopperthatarewellcaredforareextremelydurableandgenerally surviveinexcellentcondition” (Bowron,1999)

Itwouldbeexpectedthatifoilpaintsareexcessivelyresponsivemoisturechangesinthe environment andthecopperisactingasaperfectrestraint therewouldbeextensivedamagesto suchpaintings.

Yetthereis aremarkablelackofcrackingonmanypaintingsoncopper. Whenthereiscracking itismostlyfineandrandom sincethecoppersupportprovidesno dimensional biastothepaint films. M uch ofthe mechanical damage foundin paintingsoncopper resultswh enthecopper supports are dentedorfolded. Oilpaintingsoncopperrepresentoneofthemostsignificantclues astotheactualdurabilityofoilpaintswithrespecttomoistureintheenvironment

109 Appendix | FREELON BOND 37

Figure32 showstheremarkablestateofpreservationof anoiloncopper.Thisparticularpainting isby JanvanKessel, StudyofButterflyandInsects,c1655,Oiloncopper,45/16 in. x513/16 in.

Figure32, JanvanKessel, StudyofButterflyandInsects ,c1655,Oiloncopper,45/16 in. x5 13/16 in. 1983.19.3 (PhotocourtesyoftheNationalGalleryofArt,Washington,D.C.)

Canvas P aintings

Canvaspaintings represent some ofthemostcomplexstructuresintheculturalworld. Thisis becauseofthewidelyvariedmaterialsusedandtheircomplexresponsetotheenvironment.This canonlybeillustratedbylookingateachlayerindividuallyandthensuperimposingthelayers

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 110 38

together. Across-sectionofatraditionalcanvassupportedoilpaintingisshownin Fig 33 This assemblyincludesthe“support” canvas,agluesizelayer,anoilgroundandtheoildesignlayers. Asisshowninthefigurethegluesizelayerinalmosttoothintosee. Thisparticular sectionwas froma19th centuryItalianpainting.

Figure32,theconstructionofatr aditionalcanvassupportedpainting.Thisassemblyincludes the“support”canvas,agluesizelayer,anoilgroundandtheoildesignlayers. Thisparticular sectionwasfroma19th centuryItalianpainting.Thegreenbaratthetopofthepictureis0.04 in. (1mm).(Thecross-sectionandphotographcourtesyofMelvinJ.Wachowiak)

Figure34showsadetailofthesame19th centuryItalianpainting asshowninFig.33but looking fromthefront. Thisassemblyincludesthe“support”canvas,agluesizelaye r,anoilgroundand theoildesignlayers. Asisshowninthisfigurethegluesizelayeris anextremelythinfilm bridgingthegapsintheweaveofthecanvas. Eventhoughverythinthislayerisstillvery responsivetochangesinRH.

111 Appendix | FREELON BOND 39

Linensupport Gluesize Ground Designlayers

Figure34 sho wsadetailofthesame19th centuryItalianpaintingshowninFig.33butlooking fromthefront. Asisshowninthisfigurethegluesizelayerisanextremelythinfilmbridging thegapsintheweaveofthecanvas.Eventhoughverythinthislayerisstillveryresponsiveto changesinRH. (P hotographcourtesyofMelvinJ.Wachowiak)

Oneofthemostmisunderstoodfeaturesofthecanvassupported paintingsisthesupportitself. Whereithasbeen considered thatthecanvasofthepaintingisthesupport, inactualityitisthe gluesizethatmaintains thehighestforcesformostoftheRHranges.Thiscanbeillustratedby lookingattheindividuallayersofthepaintingwhentheyarerestrainedandsubjectedtochanges inrelativehumidity. (Mecklenburg, 1982)

Inadditiontoexploringhoweachlayerofthepaintingrespondstotheenvironmentalchangesit ispossibletodeterminetheactualdamagemechanismsthatoccuratdifferentlevelsofrelative humidity. Whereitwasassumedthattheinitialstressesinthematerials were zero, thatcondition

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 112 40

rarely existsinastretchedcanvaspainting.Aswillbeshownthestressesineachlayervary considerablywithchangesinrelativehumidity.

Forthisdiscussionlet’srestrainsamplesoflineninboththewarpandfilldirections.Once restraineditispossibletoseetheforcesthataredevelopedinthematerial.Inthissectioneachof thematerialsexaminedwillbeofthethicknessencounteredinatypical painting. Itisimportant tonotethattheforceperwidthofsampleactingonindividualmaterialsisusedsinceitis notpracticaltocalculatethestressesinalinentextile. Usingthisstrategy,itisalsopossible toexaminetheeffectsofthethicknessesofeachofthedifferentlayers.

Inbuildingthecompositepaintingfromthesupportcanvasupitisusefultostartwiththe canvas. ThesampleoflinentestedwasfromanUlster#8800canvas.Itisamediumweight canvasandwouldbefoundonmany easelpaintings.Boththeweftandfilldirectionswere tested.AninitialforcewasappliedtothespecimensatmidRHandtherelativehumiditywas incrementallychanged andtheforceperwidthrecorded.Thiswascontinuedforseveralcycles overalargerangeofrelativehumidity.

Figure35 showst heresultsofsuchtesting. Between10%RHand60%RHthereisrelatively littlechangeintheforceoneitherthewarpoffilldirections ofthetextile.From60%RHon thereisagradualincreaseinstressandabove80%RHtheforceincreasesdramatically.When damporwet,loosetextilesshrinkdramaticallyandwhenrestrainedtheshrinkageshowupas significantforcesinthetextile.Thisisthefirstindicationthatdramaticeventstakeplacein canvaspaintingswhenthehumiditygets very high.This behavior was replicated usingawide varietyofdifferenttextiles byGerryHedleyattheCanadianConservationInstitute. (Hedley, 1988)

113 Appendix | FREELON BOND 41

Figures 35 showsthetensileforcesperwidthmeasuredinindividualrestrainedsamplesofthe #8800lineninthewarpandfilldirectionswith changing relativehumidity.Thegreaterforces developwhentherelativehumidityisabove80%.

Ofallofthematerialsusedincanvaspaintingshideglueisthestrongestandnearlythestiffest.It isalsotheonematerialthatdevelopsthemostforcewhenrestrainedanddesiccated.Itisbecause thismaterialisbothstiff(andstrong)andhasahighdimensionalresponseatlowhumiditythatit developssomuchforce.Figure36 showsboththeforceperwidth (andstress) a very thinfilm (0.00047in.) ofgluewilldevelopwhenrestrainedanddesiccatedfrom85%to15%RH.The thicknessofthefilmisaboutthesameasthatfoundasasizecoatingonapainting. (SeeFig.34)

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 114 42 8800Linen 0 20 40 60 80 100 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 RelativeHumidity(%) F o r c e / w i d t h ( l b s / i n c h )

Restraineddesiccationofhideglue

Figure 36 showstheforceperwidthofrestrained samples ofhidegluewhendesiccatedfrom 85%to15%RH.Thestressofthehideglueatthemaximumforceperwidthofthesesamples was3920psi. From80%RHandabovethehidegluehasnostrengthandthereforenoabilityto retainthebondbetweenthe canvasandgroundlayers.

Ingeneral,theforceperwidth(andstress)developedinrestrainedanddesiccatedoilpaintis considerablylessthantheothermaterialsfoundinpaintings.Oneofthereasonsisthatwiththe exceptionofsomeofthepaints madewiththeearthcolors,thedimensionalresponsetohumidity changesislow.Ontheotherhandwhiletheearthcolorstendtohaveahigherdimensional responsetheyhaverelativelylowstiffness.Figure37 showstwopaintsamplesrestrainedand desiccatedfromaround75%to5%RH.Evenwiththislargechangeinrelativehumidity,the forcesandstressesdevelopedarelow.Sothelikely hoodthat largechanges in lowhumidity alone can damagetheoilpaintlayerislow.Ittakesacombinationofmaterialsandtheir individualresponsestochangesinhumiditytocausedeterioration.Thiscanbedemonstratedby superimposingallofthelayersofapaintingtogetherandcomparingtheresultswithanactual painting.

115 Appendix | FREELON BOND 43

0 20 40 60 80 100 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 RelativeHumidity(%) F o r c e / w i d t h ( l b s / i n c h ) Themaximumstress levelis3920psi Hidegluesizeinatypicalpainting,00047in.thickfilm

Restraineddesiccationofoilpaints

13YearoldLeadWhite, 0.0051in.thick (maxstress=94.3psi)

13YearoldNaplesYellow, 0.0063in.thick

Figure 37 showstheforceperwidthof restrainedsamplesofleadwhiteandNaplesyellowoil paints.Thestressofthewhiteleadpaintatthemaximumforceperwidthofthissamplewasonly 94.3psi. Theforceperwidthofthepaintsisconsiderablylowerthanthehideglueandabit lower thanthe#8800linenshowninfigure 33 .Thethicknessesindicatedforthepaintsamplesis typicalofthosefoundinpaintings.

Superpositionofthedifferentpaintlayers

Itispossibletoplottheinformationfrom Figs. 35,3 6,and37 onthesamegraphasshownin Fig 38.Thethicknessofthesefilmsarethesameshownintheirrespectivefiguresandwouldbe typicalofacommonpainting.Inthisfigureitispossiblecomparetheresponsesoftheindividual layersofacanvaspaintingandtodetermine thedifferentforcesoccurring at differentlevelsof RH.ForexamplethefabricisdevelopinghighforcesonlyathighRHlevelsandstaying relativelyconstantathumiditylevelsbelow80%.Thehideglueisdevelopinghighforces atvery lowRHlevelsbutloosesall strength atlevelsabove80%RH.Alsonotethatthepaintfilmsare developingrelativelylow forces andthatisonlyatverylowlevelsofRH.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 116 44

0 20 40 60 80 100 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 Relativehumidity(%) F o r c e / w i d t h ( l b s / i n c h )

Figure 37 showstheforceperwidthofrestrainedsamplesoflinen,hideglue,andleadwhitean d Naplesyellowoilpaints.Thethicknessofthesefilmsarethesameshownintheirrespective figuresandwouldbetypicalofacommonpainting. Usingthis figureitispossiblecomparethe responsesoftheindividuallayerstothatofanactualcanvaspaintingandtodeterminethe differentforcesoccurringatdifferentlevelsofRH.Forexamplethefabricisdevelopinghigh forcesathighRHlevelsandthehideglueisdevelopinghighforcedatverylowRHlevels.

Therestrainedtestingofsamplesfrom anactualpainting

Figure38 shows theforceperwidthdevelopedinrestrainedsamplesofa1906paintingby DuncanSmith. This paintingw as constructedwithamediumweightmachinewovenfabric,a hidegluesize,aleadwhitegroundandadesignlayer ofrawandburntumber.Itisimportantto notethattherearetwoareasofhighforcedevelopment,oneattheverylowlevelsofRHandthe otherattheveryhighlevelsofRH.Thisiscomparabletotheforcedevelopmentofhideglueand thecanvasasshownin Fig. 37. Whenlooking at this figureitiseasyto determine whichlayers ofanactualpainting aredevelopingthehighestforcesatdifferentlevelsofrelativehumidity.

AlsowhenlookingatbothFigures 37 and 38,italsobecomesapparentwhichm aterialsare loosingalloftheirstrength.Forexampleitissafetosaythat above80%RH thehideglueisno

117 Appendix | FREELON BOND 45 0 20 40 60 80 100 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 RelativeHumidity(%) F o r c e / w i d t h ( l b s / i n . )

groundandpaint

8800linen

Hidegluesize

longeractingasthesecurebondbetweenthegroundandlinencanvas.From80%RHandabove thepaintlayerisclearlyatriskofdelaminatingfromthecanvas.AtthissameRHthepaints filmsarethemostflexiblebutarealsointheirweakeststate.From80%RHandbelowtheforces inthefabric are changingverylittle.Above80%RH,thefabricwillshrinkiflooseandcertainly delaminatethe designlayers attachedtoit.Thiswillbeexploredinmoredetailinlatersections. Onefurthercommenthereisthatfrom10%RHto75%RH,theforcelevelinthegluelayerisso muchhigherthantheotherlayers,includingthelinencanvas.Inthisrangethehideglueisthe supportofthepainting.

UnknownAmericanPortraitbyDuncanSmith(1906)

Figure 38 showstheforcesperwidthofrestrainedsamplesofanactualpaintinginbothwarp andfilldirections.Thesepaintingsampleswereconstructedwithamediumweightmachine wovenfabric,ahide gluesize,aleadwhitegroundandadesignlayerofrawandburntumber.It isimportanttonotethattherearetwoareasof highforcedevelopment,oneattheverylowlevels ofRHandtheotherattheveryhighlevelsofRH.Thisiscomparabletotheforcedevelopment ofhideglueandthecanvasasshowninfigure37

Notalllinensshowthesamebehavior.Otherlinensarewovensuchthatthefilldirectionyarns arequitestraightandhavelittlecrimp.Itisthecrimpinayarnthatcauseshighhumidity shrinkage whenloose andhighforces whenrestrained.Figure39 showstheresponseofsuch

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 118 46

0 20 40 60 80 100 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 RelativeHumidity(%) F o r c e / w i d t h ( l b s / i n c h ) Fill Warp

linenwhenrestrainedandsubjectedtochangesinhumidity. Linensofthistypecanshowupin commerciallypreparedartists’canvaseswherethequalityofthelinenislower.Inordertoget thestifferfeelforthelinenheavierlayersofgluesize are appliedtothelinenbeforetheoil groundis applied.Thisresults inevenhigherforcesatthelowhumidityrangesasshownin

Figure 39 showsthetensileforcesperwidthmeasuredinindividualrestrainedsamplesofthe #248lineninthewarpandfilldirectionswithdecreasingrelativehumidity. Inthiscaset he greaterforcesdevelop onlyinthewarpdirection whentherelativehumidityisabove80%. The reasonthereisnoforcedevelopmentinthefilldirectionisbecausetheseyarnsarequitestraight andwithoutthecrimpfoundinthewarpyarns.

Figure 40 showstheresponsetochangesinrelativehumidityofrestrainedsamplesofa1990’s painting Thispaintingwasconstructedwithcommerciallypreparedlinenwithaheavygluesize. Thegroundlayerwasamixtureoflead,titaniumandzincinoil.Ontopofthegroundisalayer oftitaniumandzincinoil.Thetopdesignlayerwastitanium,zincandanearthcolorinoil. At veryhighrelativehumidity,above80%,theforcelevelsrisedramatically onlyinthewarp direction.Sincethereislittlecrimpinthefillyarnsthereisnoforcedeveloped. Ontheother

119 Appendix | FREELON BOND 47

figure 40

0 20 40 60 80 100 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 RelativeHumidity(%) F o r c e / w i d t h ( l b s / i n c h ) Fill Warp

248Linen

handthecauseofthe high forcesdevelopedwithdesiccationisthe additionofathick hideglue sizeinthepainting.

A importantpointtomakeisthatthestartingforcesatthebeginningofthis testwerehigh.Once thehumiditywascycledthestressesloweredtoequilibriumlevels.Thispaintingre-initializedit selfandthisactuallyhappensfrequently.Artistandconservatorsareroutinelyre-stretching paintingsandthereisreallynowayofknowingthelevelofstresscausedbythatstretching.Itis almostaguaranteethatrecentlystretchedpaintingshavehighstresslevelinthedifferentlayers.

Figure 40 shows theforceperwidthdevelopedinrestrainedsamplesofa1990paintingby an unknown American. Thispaintingwasconstructedwithcommerciallypreparedlinen witha heavygluesize.Thegroundlayerwas amixtureoflead, titaniumandzincinoil. Ontopofthe groundisalayeroftitaniumandzincinoil.Thetopdesignlayerwastitanium,zincandanearth colorinoil. Atveryhighrelativehumidity,above 80%,theforcelevelsrisedramatically onlyin thewarpdirection.Sincethereislittlecrimpinthefillyarnsthereisnoforcedeveloped. Onthe otherhandthecauseofthe high forcesdevelopedwithdesiccationisthe additionofathick hide gluesizeinthepainting.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 120 48

0 20 40 60 80 100 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 RelativeHumidity(%) F o r c e / w i d t h ( l b s / i n . ) Warp Fill Startofthetest

MechanicalDamageduetotheExpansionoftheStretcher

Whiledirectlyrelatedtoenvironmentalfactorsit is usefultolookatthemostobvioussourcesof damage, the simpleexpansionofthestretcher. Examiningtheexpansionofastretcherisalso helpfulinunderstandingwhythemechanicalmeasurementsareuseful.Supposethatasmall paintingof25in.x30in.iskeyed-outinthecornerssuchthatthereisanexpansionof1/16 in.in eachdirectionforallofthecornersasshown infigure 41 Thismeansthatthe 25in. x 30in. paintinghasbeenexpandedatotalof 1/8in. ineachdirection.Thisisactuallyprettytypicalfor olderpaintingsthathavebecomelooseontheirstretchers.

1/16in.

1/16in.

Figure 41 , showthecornerofastretcher keyedout 1/16 in.ineachdirection.

Nowlet’sconsiderwhatthisdeformationdoestotheactualpainting.Figure 42 showsthestrains resultingfromkeyingoutthe 25in. x 30in. paintingatotalof 1/8in. ineachdirection.

121 Appendix | FREELON BOND 49

Strain=0.01orhigher

Strain=0.0042

Strain=0.005 25in.

Figure 42, showsthestrainsresultingfromkeyingouta 25in.x 30in. paintingatotalof 1/8in. ineachdirection.Crackingisillustratedinallofthecorners.

Strainsarecalculatedasthechangeinlengthdividedbytheoriginallength.Inthemiddleofthe paintingand inthehorizontaldirectionthestrainsare 1/8in./25in. or0.005microstrainswhich istheinitialyieldpointofmostartists’materials.Thisisalso0.5%elongation.Inthecenterof thepaintingandintheverticaldirection,thestrainsare 1/8 in. / 30in. or0.0042(0.42% elongation).

Inthecornershoweverthisisadifferentstory.Becausethepaintingistacked(stapled)tothe stretcherthereislittlefreedomforthepaintingtoexpandandthestretcherexpansionresultsin veryhighstrains.Theclosertothecornerthehigherthestrainsget.Thisiswhyoneoftensees cracksradiatingoutfromthecornersofpaintings. Ifcracksdonotinitiallyoccuratthetimeof thestretching,desiccationcertainlycanprecipitateit. Thepoint ofallofthisisthemagnitudeof thestrainsistypicallyfoundinpaintingscanbeusedasthecriteriafordiscussingthe performanceofpaints.Soifapaintfilm,asshowninamechanicaltestcannotelongatetoa

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 122 50

3 0

n.

i

strainofeven0.005,(0.5%elongation)thenitismostlikelygoingtocrackwithevenmodest stretcherexpansion. Itisgenerallytheextensivedistortionoftherawcanvasatthetacksor staplesattheedgesofpaintingsthatrelievesthestrainsontheactualdesignlayersandmitigates theseverityofstretching.

EffectsofCycling CanvasPaintings inLargeRanges ofRelativeHumidity

Ifa canvas painting, asdescribedinthisdiscussion, isexposedtocyclingoflargechangesin relativehumiditythenanotherformofcornercrackscanoccur.Thiscanbedemonstratedby constructinga“mock”paintingofcanvas,asizelayerofhideglueanda“designlayer” composedofahardgessofilmhavingthemechanicalpropertiesofanoldbrittleoilpaintfilm. Thedimensionsofthepaintingwere 20in.x30in. Thegessolayerwasahideglueandcalcium carbonatemixture (Mecklenburgetal,1994)

Figure 43 illustratestheresultsofsuchanexperiment. Thismockpaintingwascycledfrom90% RHto35%RHandthenbackto90%RH.Each half cycle(fromhightolowRHorlowtohigh RH)required just lessthan 24 hoursforfullequilibration. Periodicallythetestpaintingwas examinedtoseewhatcrackingmighthaveoccurred.Itwasobservedthat withonesmall exception, allofthecracksoccurredatthecornersofthepainting. Attheendsofselectedcycles (#4,#7,and#9),theendsofthecrackswerenotedandmarked.Forexampleacrackwithaline anda“4”markednexttoitindicatedthemaximumextensionofthecrackafter4complete cyclesfrom90%RHto35%RHandbackto90%RH.

Afterninefullcyclesthecrackextensionceasedaswasdemonstratedbyadditionalcycles.The paintingwasthensubjectedtoseveralmoreseverecyclesfrom95%RHto20%RHandback. Therewasnoadditional crackingorcrackextension.Whatisofinterestisthatthefirst4cycles causedthemostinitialdamageandsubsequentcyclesonlyproducedsmallerincrementsofcrack extensionuntilitceasedaltogether.Moreseverecyclesdidnotaddtothedamage.T hecracks

123 Appendix | FREELON BOND 51

thatdidoccurbegantoactasexpansionjointsandnowthepaintingcanexperiencelargeRH cyclingwithoutfurtherdamage.

Fromthediscussionabovehidegluelosesstrengthathighhumiditylevelsbutdevelopsvery highstresseswhendesiccated.Itwasalsoshownthatactingalonepaintlayerswon’tgenerally develophighstressesanddamagethemselveswhenrestrainedanddesiccated.Itisthe desiccationofthegluelayeractingonthepaintlayerthatcancausesproblems.Thecracks showninthecornerofthetestpainting(Fig43)reflecttheeffectsofthehideglue (andtoasmall extentthepaintitself) pullingfromthecentralregionsandawayfromthecornersofthepainting. Thisdistortsthedesignlayerssufficientlytocausecrackinginthepaintlayeratthecorners. But whyistherenocrackinginthecentralregionsofthepainting?Thisisbecausetheglueandthe paintarecontractingsimultaneouslywithdesiccationandrelieving,notincreasingstressesinthe paintnotincreasingthem. Itwillbeshownthatexposure verywet(notjusthighRH)conditions or lowtemperaturelevelscausethe severe crackingtothecentralregionsofthepaintings.

Figure 43 showstheresultsofcyclingandexperimental“mock”painting tocyclesoflarge changesinrelativehumidity.Additionalcyclingbeyondtheinitial9cycleddidnofurther

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 124 52

damageasthecracksthatoccurredrelievedthestressesduetotheinitialRHcycles.Thismodel paintingwasconstructedwithastretchedcanvas,ahidegluesizeandastiffgessoactingasa designlayer.

Inanactualpainting,itisnotunusualtoseeboththecrackingfromstretcherexpansionand environmentalcyclinginlargerangesofrelativehumiditycombined.ThisisillustratedinFig 44

Figure 44 showsthecombinationofcrackpatternsfromstretcherexpansionandcyclinginlarge changesinrelativehumidity.

125 Appendix | FREELON BOND 53

MoistureInducedDamageto Canvas Paintings

RH Cycling

Stretcherexpansion

Oneofthemostfrequentlyencounteredtypesofdamagetopaintings,bothoncanvasandon woodisaresultofexposuretohighmoisturelevels.Inoldhistoricbuildings,themoisturecan condenseontheinsideofexteriorwallsfromavarietyofreasons.Oneofthosereasonsisthe excessivehumidification iftheinteriorspacesofthebuildinginthewintertime.Atsuchtimes theexteriorwallsofolderbuildingcangetquitecoldtothepointwheretheinteriorsurfaces reachthedewpoint.Thedewpointistheambienttemperaturewheremoisturecondenses outof theair.Behindpaintings,which can actasinsulation,moisturecondensesonthecoldwalls. Converselyinthesummertime,theexteriorwallsgethotandthespacebehindthepaintingis warmerthantheinteriorspaceofthegallerywherethepaintingisexhibited.Insuchcasesthe relativehumiditycangetaslowas35%.Themicroclimatebehindpaintingshanginginthe inside surfaces of exteriorwalls isentirelydifferentthanthecentralgalleryspace.

Anotherreasonthatcondensationcanoccuristhatinoldstonebuildings,themasonrywallsare cooledduringthewintertime.Thesemassivestonewalls,duetotheirhighthermalmass,are slowtowarmupwiththechangingseasonsandinthespringtimewarmmoistairentersthe buildingalong withvisitorsthroughopendoors.Thisresultsinextensivecondensationofnot onlythewallsbutpaintingshangingonthosewalls.Thisoccursonmanyofthemonumentsin Washington,D.C.intheUnitedStates.

Oneofthelessfrequentlyconsideredconditionsoccursonveryhot,humiddaysinthe summertime.InJulyinRomeforexample,theoutsidetemperaturecaneasilyreach90o Fand therelativehumiditycanreach65%orhigher.InsideabuildingsuchasSt.Peter’sBasilicaitis considerablycooler wherethetemperaturecanbearound80 o Fbuttherelativehumiditycanbe ashighas90%.Thisisaresultofopendoorsandtheoutsideaircoolsatitentersthebuilding. Theairinsuchlargebuildings canstratifyandthecoolerairremainsatthelowerlevelsof spaces where thehumidity canbe evenhigher,evenapproachingthedewpoint.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 126 54

Existingenvironmentalconditionsarenottheonlysourceofhighmoisturelevels.Manyofthe traditionalliningtechniquesusinghidegluesandpastaliningadhesivescontributetoincreasing themoisturecontentofthepainting.Thisincreasesthepotentialforcausingmassiveshrinkage oftheoriginalpaintingcanvasandweakeningtheoriginalgluesize.

Watercondensingonpaintingsoftentendstoruntothebottomofthepaintingandtypically causingdamagealongthebottomsofthepaintingsasshowninfigure45.Inthecaseofthe paintingshowninthefigure46,therewassufficientwater on thecanvas thatit totallydisrupted theadhesivebondofthe animalgluesizelayer.Hencethecanvasshrank,gluesizelostallofit adhesivestrengthandthepaintandgroundlayerscompletely crushed fromthecanvas.Now thereisinsufficient room tofitthebrokenpiecesofthepaintbackintoproperalignment.

127 Appendix | FREELON BOND 55

Figure45 showsadetailofa19 th centuryItalianpainting.Itisclearthattotalseparationofthe paintandgroundlayersfromthecanvashasoccurred.Themoisturelevelwassufficienttocause crackingofthedesignlayers andfailureofthebondatthegluelayer. Thecanvasshrank,andthe paintcleaved fromthecanvas.(PhotobyMatteoRossiDoria)

Figure46 showsadetailof a19 th centuryItalian painting.Itisclearthattotalseparationofthe paintandgroundlayersfromthecanvashasoccurred.Themoisturewassufficienttocausethe adhesivebondoftheanimalgluesizelayertocompletelyfail.(PhotobyMatteoRossiDoria)

Consequencesofthe MechanicalandDimensional BehavioroftheDifferent Oil Paints

Ifapaintingweresubjectedtosevereswingsofrelativehumidity,saybetween95%ormoreto say35%thenonewouldexpectdamagetothedesignlayersofthepainting.Thehighrelative

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 128 56

humiditycaneasilybearesultofcondensingcoldexteriorwallinhistoricbuildings.Conversely, whereexteriorwallscangetcoldtheycanalsoabsorbheatinthesummertime.Warmwalls effectivelylowertherelativehumidityoftheambientairincloseproximitytothewalls.So paintingshangingontheinsideofexteriorwallscaneasily beexposedofbothcoldmoistand warmdryenvironments.

Forthisdiscussionlet’ssupposewehadapaintingthatcontainedpaintsmadewithdryingoils withearthcolorssuchasSienna,ochre,andumberandwhiteleadandasizeofhideglue.And let’s supposethatthepaintingwashangingonanexteriorwallwheretherewerelargechangesin relativehumidityoveranannualcycle.Inlookingatthemechanicalanddimensionalproperties ofthedifferentpaintsdiscussedabove,onewouldexpectthatthewhiteleadpaint,becauseofits strengthandresistancetomoisturewouldsurvivelargeswingsinrelativehumidity.Ontheother handonemightsuspectthatweakanddimensionallyresponsivepaintslikeumber,ocher,and Siennawouldmostlikelysufferconsiderabledamageinthesameharshenvironment.Detailsof suchapaintingareshowninfigure47

Athighrelativehumiditythegluesizeandtheearthcolorstendtoswellandexperience “compressionset”inmuchthesamewaywoodmightwhenrestrainedandexposedtohigh moisturelevels.Theearthcolorshaveverylittlestrengthandthereforelittleabilitytoresist deforming.Whenthesizeandearthcolorsdryoutatlowlevelsofrelativehumiditytheywill shrinkandcrack.Oncethepaintstartstofailtheadditionalfailureofthegluedsizeis aggravatedandpaintflakesoffofthepainting.Clearlyavoidinghighhumiditylevelsisof primaryimportance.

Itisnowimportanttonotethatmoistureinduceddamagetopaintingsisselectiveinth at theweakerpaintswillfailandthedurableoneswill maintainsomestability.Thisisin contrasttodamageduetoexcessivelylowtemperatureswhich hasthesameadverse effects onallpaints.

129 Appendix | FREELON BOND 57

Figure47 showsthedetail ofapaintingcontainingbothwhiteleadpaints(bluearrows)and paintsmadewiththeearthcolors,ochreandSienna(yellowarrows).Thispaintingwasdamaged bywetwallsandtheselectivedamageisduetothelowstrengthandhighdimensionalresponse tomoistureoftheearthcolors. (PhotobyMatteoRossiDoria)

CommentaryontheRangesandEffectsofExposuretoRelativeHumidity

If oneexamines fullyrestrained culturalmaterials exposedtochangesinrelativehumidityitis possibletogaininsightintotheallowableRHrangestheycantoleratesafely. Thisrequiresthat thereisinformationregardingtheRHrelatedmechanicalanddimensionalpropertiesofthese materialsavailable.

Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture 130 58

Usingthemoststringentcriteriasuchalowyieldsstrains, ful l restraint ofthematerialsin themostdimensionallyunstabledirection andeventhepresenceofpre-exitingstresses most materialsdiscussedcaneasilywithstandRHrangesfrom30%RHto60%RH reversibly.

Nearlyall RH-related damagetobothcanvas andwoodpanelpaintingsandwoodfurnitureis causedbyexcursionstoveryhighlevelsofrelativehumidityorevenliquidwaterandthen desiccationtolowlevelsofRH.Priortotheinterventionofcentralheatinglowlevelsofrelative humiditywould meaninthe20%RHto30%RHrange

Addtothisthemitigatingcircumstances:

Betterwoodobjectsaremadewithwoodscutintheradialdirection,eventhebetter veneers.Theytypicallyhaveonlyhalfofthedimensionalresponsetomoisturewhen compared totangentiallycutwoods.

Nomaterialinanycollectioniscompletelyrestrained.Evenwoodsbondedcrossgrained tooneanothergetsomerelieffromthedimensionalresponseinthelongitudinaldirection andwhilethisseemtobelittleitisactually effective.