A.Myrna Nurse, PhD Editor-in-Chief

Pamela Mosley Gresham, JD Managing Editor & Chair, DE & I Council

Nirmaljit K. Rathee, PhD Deputy Editor

Joseph Fees, PhD Copy Editor

Francine Edwards, PhD Copy Editor

Danielle L. Archambault, EdD Member

Albee Mendoza, PhD, ACUE Member

Brandon Maddox Graphic Designer

Delaware State University’s Diversity, Equity & Inclusion (DE&I) Council is excited to invite faculty, staff, and students to submit articles or stories to be published in its monthly e-journal. The e-journal’s title is: Dynamic Self Matters. Its mission is: Our commitment to affirming members of the entire campus community.

Your article or paper can be on any of the following topics:

• An intercultural experience.

Note: An outstanding submission to be considered for the main feature

• Community service or work

• Travel experience

• Academic accomplishment or interest

• Sports accomplishment or interest

• Activism—internal or external of DSU

• Customer service at DSU

• Review of a book, movie, or documentary

Your article or paper must adhere to the following format and requirements:

• 800 to 1,000 words.

Note: An intercultural experience article is not to exceed 1,500 words.

• Times Roman, 12 point

• Double-spaced

• One-inch margins

• Minimum grammatical, mechanical, and spelling errors

• Either MLA or APA Style of documentation: Choose one and be consistent.

Please send your article or paper for consideration to be published in our fall semester 2023 issue no later than September 15, 2023, to: DEI@desu.edu.

NOTE: All articles must be submitted as a Word document only. No .pdf or PowerPoint, please. Failure to submit a Word document may result in a delay in processing your submission

Since childhood, my mamà y papà instilled in me that education was important. “Of course,” you may think, but for me, it was the ONLY option for me to make my parents’ sacrifices worth the effort. As immigrants, my parents left their home countries, their families, and their lives behind for their children to get to experience their American Dream; for their children to have the opportunity for a good education and good jobs which they never experienced. For me, being a first-generation (1G) college student was my American Dream because throughout elementary school and high school, as an immigrant, my resources felt limited. Having a 1G status meant that I was the first in my family to attend college in America.

I am a Latina with a Hispanic background, which aligns with the majority of other 1G college students who are more likely to be those who identify as female, Hispanic, African American, and/or come from low-income families (Terenzini et al., 1996). Being a 1G college student, it seemed that the odds were stacked against me. Unfortunately, 1G students have a different academic experience than students who have parents who have gone to college. For many reasons, 1G students have higher dropout rates and more of a lack of understanding

of the college culture (e.g., Engle, 2007; Gohn & Albin, 2006). But I had to get into college first. Despite my parents’ hopes for higher education, getting into college was one of the most challenging obstacles of my life. For many, being a 1G student was a proud accomplishment. For me, it was overwhelming. My peers did not see the tears running down my face because I did not understand FAFSA and risked not finishing for failing to get government assistance due to my status. They did not see the struggle to go on collegevisits with family because my mamà y papà did not speak English or did not understand the process. They did not see the hardships of finding scholarships I could apply for because I was not a U.S. Citizen. They did not feel the anxiety of not having anyone around to truly explain how college would be without sugarcoating it.

Being a 1G student of immigrants, I felt immense pressure to demonstrate that I was indeed proof that my parents’ sacrifice was worth it. Not only was I a 1G college student, I was also a DACA (Deferred Action of Childhood Arrivals) student. An immigrant child from immigrant parents felt like a slur to say to myself because of the rising race tensions and the negative connotations on the newswiththeword“immigrant.”Ibelievethatthis

feeling may be something many Americans will never experience and led me to not say anything or to ask for help. Despite these hardships, with my dream within reach, I applied and got admitted to several colleges and universities.

It was official! I was a Wolverine! Despite these visible and invisible hardships, I was happy when I officially became a Wolverine at Wesley College in Fall 2018. An exciting start to my college journey! Wesley was a primarily undergraduate institution (PUI), which once had ties with the United Methodist Church (DSU, 2023). At Wesley, I wasted no time in joining extracurriculars and getting involved. I tutored, became a student ambassador, was an RA, and joined plenty of clubs and organizations. I wanted to go beyond what my parents instilled and make connections I knew would last me a lifetime. My biggest priority was making the high school to college transition easier for people who came from backgrounds like my own. As a student ambassador, I had a voice to help Spanish speakers who came with their families to see

Wesley, and I helped with the language barriers and communication issues as I was fluent in both English and Spanish. This opportunity also allowed me to voice how college really was and the steps needed to prepare students considering coming to Wesley. These struggles may have been tough for me, but I wanted to make the experience less overwhelming for other 1G college students, for anyone I interacted with considering college, and for anyone living under the pressures of their family. I even created the Latinx Club at Wesley because I was motivated and was pursuing my dream. In a sample of one hundred 1G college students who were either Latinx or Asian, as personal and career-related motivation increased, college adjustment and commitment increased (Dennis et al., 2005). Like these students, feeling adjusted and committed, I was building my own home and family at Wesley; however, there were

rumors going around that Wesley was coming to an end.

It was official. I was almost three years into my program and my degree felt like it was being dangled over a pit of sharks. My stomach rumbled, my hands trembled, and my mind was running at one hundred miles per hour. Wesley College would be acquired by Delaware State University. Will I get to keep my major and honors status? Will my credits transition? Should I find a different college? Will my scholarships and DACA status impede me from continuing my education? Getting into college was hard enough, will I have to restart the whole process and lose all the connections I have made? So many questions and not enough answers.

On top of all these outside concerns, COVID-19 was still prominent. I was curious if the transition meant I had to get more immunizations and if commuting would affect my access to classes and the school in general. Fear is all I felt at that moment. I did not prepare for a big transition this late in my college career and I knew it would not be the same or as easy as my peers because of my immigrant status. In everything I did as a student ambassador for others, I had to turn toward myself and use that information to create my new home.

After plenty of back-and-forth emails, meetings, and showing up to offices at Wesley and DSU, I finally finished the transition. My assumptive world was being challenged and I lost friends and I lost professors who helped me on my college journey. It was time to rebuild everything I lost in the transition. Luckily, even with their own hardships and rough transitions, my DSU family brought me in as their own. Once a Wolverine and now a Hornet, I felt out of place. DSU was an HBCU, and it was significantly bigger, and I had to adjust to the new environment. I realized I continued to see everything as a negative. I lost

this, I lost that. But what will I gain? In time, I realized that this was an opportunity in disguise. My dream of graduating from college combined with my grit continued to push me through. Grit involved consistency of interests and perseverance of efforts over time (Duckworth et al., 2007). I was not alone in my story. In a sample of 264 1G Latinx students, O’Neal et al. (2016) reported that both citizen and non-citizen students demonstrated grit in overcoming obstacles. And so, I began my new journey. I gained friends, I gained experience, and I gained new connections with professors and organizations. Finally, it was beginning to feel like home.

I knew this was true when I gave my first presentation at DSU. I was so nervous. It was a new class full of strangers and not a single face I remember from Wesley. My hands were clammy, and it felt like I swallowed my tongue. When I gave my presentation on White Nostalgia (Matt, 2007), it felt like I had forgotten English. My voice was shaky, and I stumbled on some words. I felt defeated sitting back down ashamed at how it went: my worst public speaking yet. But it was the girls behind me who gave me the biggest smiles. They saw I was wearing a Wesley shirt, told me I did great and took me under their wing. For the rest of my time at DSU, they showed me how to be involved and how to be successful. I am grateful for students like them who realized the transition was not simple and made me feel like I belonged.

I overcame my struggle, but it is one that I do not want anyone else to have. Fear turned into happiness and relief. Despite the challenges I have and continue to endure, I have learned that success is what I make it. Regardless of the obstacles, I will continue to strive toward my goals and meet the expectations given to me by my family, professors, and schools. This young immigrant is paving the way for others like me. Thank you, Wesley, and thank you, DSU. My gratitude for the contributions to my future success is immeasurable. I graduated Magna Cum Laude from DSU with honors in Spring 2022. The acquisition tested my patience and resilience, but I came out stronger. I am a proud Wolverine and Hornet for life.

Aisli Torres Landeros was born in Mexico and is a firstgeneration college graduate. She was accepted into the Honors Program at Wesley College in 2018 and transferred to Delaware State University after the acquisition in 2021. Aisli is a Delaware State alumna, Class of 2022, with Magna Cum Laude honors and a B.S. in Psychology. Having achieved a goal she and her family have dreamed of all her life, Aisli continues to dream bigger. She is setting her sights on a graduate degree, and is currently in pursuit of her master’s degree in social work, combining herlove for holistic services, lifelong learning, and counseling psychology. Aisli hopes to guide adolescents much like herself as she furthers her academic endeavors.

Dennis, J.M., Phinney, J.S., & Chuateco, L.I. (2005). The role of motivation, parental support, and peer support in the academic success of ethnic minority firstgeneration college students. Journal of College Student Development, 46(3), 223-236.

DSU. (2023). History of Wesley College. Delaware State University. https://www.desu.edu/about/our-history/history-wesley-college.

Duckworth, A.L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M.D., & Kelly, D.R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9, 1087-1101.

Engle, J. (2007). Postsecondary access and success for first-generation college students. American Academic, 3, 25-48.

Gohn, L.A., & Albin, G. R. (2006). Understanding College Student Subpopulations: A Guide for Student Affairs Professionals. National Association of Student Personnel Administrators: Washington, D.C.

Matt, S. J. (2007). You can’t go home again: Homesickness and nostalgia in U.S. History. The Journal of American History, 2(94), 469-497.

O’Neal, C.R., Espino, M.M., Goldthrite, A., Morin, M.F., Weston, L., Hernandez, P., & Fuhrmann, A. (2016). Grit under duress: Stress, strengths, and academic success among non-citizen and citizen Latina/o first-generation college students. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 38(4), 446-466.

Terenzini, P., Springer, L., Yaeger, P., Pascarella, E., & Nora, A. (1996). First-generation college students: Characteristics, experiences, and cognitive development. Research in Higher Education, 37(1), 1-22.

I first picked up a golf club at eight years old and never stopped. Throughout elementary school and high school, I knew I wanted to play golf in college. My parents supported my dream and flew with me to play in tournaments for exposure in the U.S. I flew to the U.S. (sometimes alone, sometimes with my family) on five separate occasions to play with the hopes of receiving a scholarship from a college or university. I met Coach Richard McCall at a tournament and immediately clicked with him. He watched me play a couple of holes and offered me a spot on a college team. So, I left my home country, Thailand, during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic to pursue my education and my dream of playing college sports. I flew across the world to come to DSU.

Being an international student comes with its pros and cons. The obvious pro is that I get to pursue my “American Dream.” I got the opportunity to attend college at DSU as a student-athlete through golf. Despite the world being on lockdown, my parents booked me a one-way ticket to the U.S. in August 2020. Everything that I owned was packed into my twenty-four-inch suitcase. From a study by Dennis et al. (2005), in a sample of one hundred college students who were either Latinx or Asian, as personal and career-related motivation increased, college adjustment and commitment increased. This held true for me because I was motivated to make my mark at DSU and along

with that came a commitment to graduate college and find ways to adjust to my life in America. For example, when classes moved online and golf practice was suspended due to COVID-19, I did not back down and fly home. I stayed committed to my studies and golf. I spent the summer at a golf course working on improving my game, despite only playing competitively for a semester during my freshman year.

On the other hand, I have experienced some cons being an international student. Being alone in a foreign country is a roller coaster of an experience. It made me appreciate home so much more. My biggest culture shock was transitioning from being in the majority in my home country to the minority in America. I am not alone in my feelings as the college student population has been growing more diverse in the last two decades, especially in the number of historically racial minority students in higher education (de Brey et al., 2019). It was strange having to explain my culture to people for the first time in my life. It made me realize how little people know about Asian culture on the West side of the world. On top of that, I was now an immigrant. In the eyes of the U.S., I was a “legal alien.” I could not vote. I could not work off campus without authorization. It was difficult to get a loan, a credit card, or even a driver’s license. I could be overqualified for an internship and still get rejected because of my status.

Another con is being so far away from my family. I was in the U.S. for almost two full years before seeing my family again. I left home in the summer of 2020anddidnotseemyfamilyuntilthesummer of 2022. I bounced around from campus housing to host families’ houses to friends’ houses. I vividly remember Thanksgiving break in my freshman year, which was in the fall semester We were told not to return to campus until January 9 because of COVID-19, which was in the spring semester. Everyone packed their bags for home but me. It was my first time experiencing “winter” because where I am from, it is ninety degrees Fahrenheit all year round. I was not prepared for how many layers I would have to wear! I spent three weeks alone on campus before flying down to Florida to see my childhood friend. I would have spent my first Christmas away from home alone if it were not for her!

Having a huge time difference was another con. I used to take for granted being able to call my parents whenever I wanted to. There is an eleven to twelve-hour time difference depending on the daylight savings from here to home. I had to tell my parents a day in advance if I wanted to call them. If there was an emergency, I could call my parents, but it was not guaranteed that they would be awake to pick up the phone!

Despiteallthechallengesof beinganinternational student, I love my experience. I have seen things I would have never seen or experienced if I had not left home! For example, I was able to experience different seasons for the first time in my life. Before the U.S., I did not know what fall, spring, and winter was. In Thailand, there are two seasons: summer season and rainy season. Although there is rain, the heat and humidity remain the same all year around! I have also been blessed with an amazing support

References

system. I have teammates and friends and coaches that care about me and are getting to know my culture With my team, I am blessed to travel to so many U.S states For golf tournaments, we traveled to Florida, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, New York, Washington, D.C., and New Jersey.

After experiencing both pros and cons, being an international student, a first-generation college student, and a student-athlete helped me grow tremendously. Transitioning from a teenager to an adult still is hard, and this is amplified by my family being a twenty-four-hour plane ride away. I have learned to be resilient and adaptive and be a problem solver. I have had to expand my social circle and search for opportunities. From my personal and professional growth over the years at DSU, I now know what I want to do with my life. I want to pursue a career in psychology and I plan on remaining in school for at least another seven years. I do not know if I want to remain in the U.S. for the rest of my life, but I definitely want to explore other U.S. states. Apart from the “American Dream,” I have another future dream: when I retire, I will live on a beach in Krabi, Thailand.

Verny, Class of 2024

Estelle Petchprakaykarn Verny was born in Bangkok, Thailand. She is currently a Junior and a Psychology major at the Wesley College of Health and Behavioral Sciences. Estelle was offered a scholarship to play on the Women’s Golf Team at Delaware State University in 2020. She is a student-athlete, a first-generation college student, and an international student. Estelle plans on attending graduate school to pursue her new dream of becoming a clinical psychologist.

de Brey, C., Musu, L., McFarland, J., Wilkinson-Flicker, S., Diliberti, M., Zhang, A., Branstetter, C., & Wang, X. (2019). Status and trends in the education of racial and ethnic groups 2018 (NCES 2019-038). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/.

Dennis, J.M., Phinney, J.S., & Chuateco, L.I. (2005). The role of motivation, parental support, and peer support in the academic success of ethnic minority first-generation college students. Journal of College Student Development, 46(3), 223-236.

The senior thesis focused on the impacts of neoliberal policies on Mexico’s political economy that inflated migration patterns. Twenty-seven DREAMers (the DREAM acronym stands for dedication, responsibility, education, attitude, and motivation) who have graduated or currently attend Delaware State in hopes of better understanding their own personal ties to neoliberal policies and migrating were interviewed for this study. The occupations of the students’ parents were also analyzed. This research aimed to humanize migrants, who are almost always portrayed as criminals and underserving of basic human rights and to thoroughly examine the economic root causes in Mexico and Central America and tie them back to the neoliberal policies that were viciously implemented by American and Mexican capitalists in the ’90s and 2000s.

Acknowledgment

I want to thank all the DREAMers who confided in me such personal stories about their migration history. I hope this research amplifies their voices and struggles as we move forward toward our liberation.

Introduction

This analysis focused on neoliberalism in Mexico and its impact on post-NAFTA migration patterns. Neoliberalism is defined as the philosophical view that a society’s political and economic institutions should be robustly liberal and capitalist but supplemented by a constitutionally limited democracy and a modest welfare state. America’s privatization of Mexico’s industries created a mass migrant population. The plunder of resources and labor that peaked in the late ’90s and early 2000s in the agricultural, manufacturing, energy, and service sectors led to a massive number of refugees escaping poverty, unemployment, inflation, and violence. If immigration reform is passed granting a pathway to citizenship to all undocumented migrants—the social and economic conditions in the home countries would remain the same. In addition to the exploitation of Mexican labor in Mexico, the exploitation of undocumented migrants in America plagues the immigrant community. Undocumented workers are used as fodder in the accumulation of capital. The despicable narrative portraying undocumented people as mooching off social services is false and ignores their exploitation. In addition to not receiving social services benefits such as healthcare and financial aid for higher education, they are also ostracized from society due to the fear of deportation.

Twenty-seven DREAMers (current and alumni) were interviewed to better understand their own personal migration stories in relation to neoliberalism. The follow table reflects the participant place of origin:

Place of origin Number (N=)

Mexico N = 25

Guatemala or El N = 2

Salvador

Mexico City N = 4

Michoacan or N = 3

Guanajuato

Tabasco or Veracruz N = 2

The interviewees were asked questions related to their families’ economic and social conditions, post-migration questions about their parents’ employment and their battles with economic insecurities. Imagine these students crossing through the desert or swimming across the Rio Grande before they were even old enough to enter kindergarten. This is a cruel reality for millions of people. Not all the DREAMers interviewed had to take these life-risking endeavors. Many came on a plane and overstayed their visas, and others used altered/false documents. Nonetheless, the way they arrived in this nation has little impact on how they are treated and perceived once they have been labeled an “illegal.”

The mainstream media typically portrays the root causes of migration from Mexico and Central America in broad demeanors, almost as if migration happens in a vacuum. It should not be a crime to want a better life. The follow table reflects the rationale for migration:

In hopes of a better future N = 13

Economic instability N = 11

Escaping violence N = 7

Michoacan or Guanajuato N = 3

Tabasco or Veracruz N = 2

In relation to the jobs that parents worked, most were in the informal sectors of the economy. Jobs consisted of grueling work in agriculture, factories, construction, cleaning services, street vending, and a variety of other low-paying and exploited occupations (see Table 3). Many were unemployed and had difficulty finding good-paying opportunities, even with a college degree. Others had government, military, or company jobs, but even these were not enough to escape the desperation inflicted by neoliberal policies.

Areas of employment Number (N=)

Street Vendors N = 6

Farming/Agriculture N = 5

Bus/Taxi Driver, Factory, Construction, Medical Services N = 2

Hotel Service N = 3

Babysitting, Private Company, Government Agency, Military, Small Business Owner, Accountant, Social Worker, Textile Industry, Janitorial Services, Retail

N = 1

Unemployed N = 9

Undocumented migrants are the ones who work twelve-to-fourteen-hour shifts in restaurants, factories, street vending, construction, landscaping, painting, hotel cleaning, and many other low-paying jobs. They perform back-breaking services without receiving healthcare or retirement benefits. It is their labor that keeps this economy afloat, yet they live with the constant fear of deportation while working in a country that does not value them as people. In the search for the American dream, many have found the American nightmare.

The predatory privatization of Mexico greatly raised the cost of living, especially for food, gas, rent, energy, baby supplies, and other necessities (Laurell, 2015). When asked if their parents saw an increase in the cost of living throughout the five years before migration: nineteen DREAMers answered yes and six said they did not. The rise in the cost of living has been a persistent theme in developing countries that have experienced structural adjustment policies by the IMF and the World Bank (Cypher, 2011). Using the excuse to modernize Mexico, neoliberalism plunged workers into deeper poverty and desperation. Many parents could not afford to house, clothe, and feed their children even with fulltime jobs.

Sixteen DREAMers stated that their families lived in poverty in the years before they decided to migrate. Ten stated that they were able to acquire the necessities to survive but economic mobility was nearly impossible. Eleven DREAMers stated that their parents consistently battled unemployment, and fourteen claimed their parents did not.

To date, approximately ten to twelve million undocumented individuals live in the United States. The undocumented community in the United States is an oppressed people who face discrimination based on their race, legal status, and as low-paid workers. A person in America without legal status wants the same as a person with legal status. They want respect, freedom, love, education, work, healthcare, a home, and a future. No human being is “illegal,” especially not those who were forced out of their home nations due to neoliberal policies and forced to cross an imaginary line.

Victor Hugo Urquiza

Victor Hugo Urquiza is a senior majoring in political science and minoring in philosophy. He has been organizing around immigrant justice since high school. Being a DREAMer himself, he has an undying passion to help my people. At DSU, he has committed himself by being the corresponding secretary for the Dreamer’s Rights Empowerment & Activism Movement. In the summer, he will be participating in the Dream Summer fellowship with UCLA working on immigration reform and helping undocumented youth receive higher education. He plans to dedicate his life to fighting for immigration reform for all undocumented people.

Cypher, J. M. (2011). MEXICO SINCE NAFTA: Elite Delusions and the Reality of Decline. New Labor Forum, 20(3), 61–69. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41408580.

Laurell, A. C. (2015). Three Decades of Neoliberalism in Mexico: The Destruction of Society. International Journal of Health Services, 45(2), 246–264. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45140494.

Vallier, K. (2022). Neoliberalism. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2022). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/neoliberalism/.

Blind and visually impaired students are challenged daily with navigating college campuses that are not designed with them in mind. Inaccessible physical spaces, insufficient assistive technology, limited social and academic support, biases from faculty and peers are just a few of the myriad of barriers that continue to impede their success. This essay explores the fundamental ideas of Universal Design (UD) and rethinking its approach to truly reflect diversity, equity, and inclusion on college campuses.

College campuses are complex settings with a variety of structures, pathways, signage, technologies, social activities/groups, and other amenities that are best suited for the able-bodied. Through an examination of ableism in higher education using the social dominance and social learning theories, Kattari (2015) asserts that all forms of privilege as well as different ideologies have a big impact on society. These ideas explain how ableism permeates society and how people who are able-bodied have historically been viewed with a higher social value than those who are disabled. It also explains how prejudice, discrimination, and general oppression are woven into everyday interactions, systems, and institutions.

The goal of universal design is to produce inclusive and equitable systems that support social, economic, and environmental sustainability and remove barriers to inclusion and involvement for all people. It is intended to be used and accessed by everyone, regardless of age, abilities, or disabilities. In an article titled, “A US model for inclusion of disabled students in higher education settings,” Mole (2013) makes the argument that disabled students who are financially invested in their postsecondary education will want to know that they have been considered in the campus design and integrated into the available learning approaches offered:

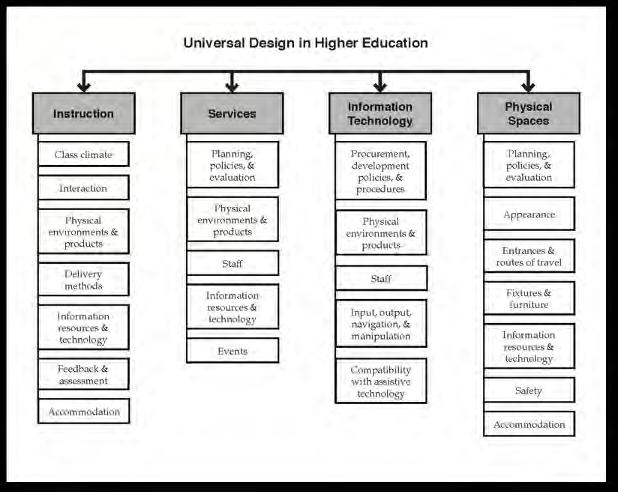

Burgstahler and Cory (2010) explored the perspectives of UD in higher education with forty scholars and practitioners, representing twenty-six postsecondary institutions and other organizations. Details of the study were included in a book titled, Universal Design in Higher Education: From Principles to Practice. According to the authors, all definitions of UD share the idea that a wide range of users can benefit from a product in an inclusive setting. They go on to state that through UD, users are not required to adapt to the constraints of any product or environment, but rather, that these conveniences adapt to the demands and preferences of any user. The study introduced a model for UD in higher education, specifically covering four areas for consideration where diverse initiatives could be implemented. They include instruction, services, information technology and physical spaces.

Source: https://www.washington.edu/doit/sites/ default/files/atoms/files/Self_Exam_Inclusive_ Campus_tagged.pdf

Null (2013) in the book, Universal Design: Principles and Models, outlines four major principles of Universal Design. They include the following:

1. Supportive: UD must give the user the assistance they need to operate, without placing an excessive burden on them.

2. Adaptable: The product or environment should accommodate the changing requirements of most individuals.

3. Accessible: The removal of attitudinal and physical barriers that may impede or harm people unnecessarily.

4. Safety-Oriented: Safe designs must identify and address physical and psychological challenges (pp. 3-6).

Null suggests Dr. Lee’s twenty-first-century paradigm of “Beautiful Universal Design” as a template for which entities can utilize as best practice to achieve success and sustainability. The model emphasizes primary, secondary, and tertiary characteristics for consideration.

Primary Characteristics: Deep, ethical, sensible, integrative, gentle and nourishing. Null (2013) defines each trait, but in summary the conclusion is that a “Beautiful Universal Design” should be a well-thought-out strategy that embodies ethics and respect for public interest and the environment. It should consider the appeal to human senses by promoting diversity in design to ensure inclusiveness, while also intentionally developing and nurturing relationships.

Secondary Characteristics: Useable, normalizing, versatile, enabling, respectable, supportive, accessible and legible.

Null (2013) posits there are nine characteristics that are represented through “UNIVERSAL.” In summary, consumers should be able to navigate their environments without disruption and discrimination. They should be able to supplement their limitations with respect, dignity and understanding.

Tertiary Characteristics: Benign, enhancing, adorable, user-friendly, touching, inspiring, flexible, useful, and loving.

According to Null (2013), to effectively grow to meet the needs of all people, UD should be acknowledged as “BEAUTIFUL.” This means that organizations should strive to be at the forefront of the market economy in order to appeal to consumers and enhance their quality of life by meeting their needs, thereby evoking impressions and feelings of appreciation and upliftment that transcend mere consumption and use.

Figure 1: Universal Design in Higher EducationUniversal Design is not just about accommodating people with disabilities. It is a thoughtful approach about designing for diversity and creating products and environments that work for everyone. However, UD is a fitting starting point for colleges and universities to eliminate barriers for blind and visually impaired students to formulate a more inclusive higher education experience. Institutions of higher learning must not be crippled by limitations, but instead work to expand their reach and grow beyond what the naked eye can see. Hellen Keller said it best, “The only thing worse than being blind is having sight but no vision” (Bhatt & Hughes, 2019, p.58).

Cecile K. CunninghamCecile K. Cunningham is a certified leadership and management professional with more than two decades of experience in the fields of public relations, nonprofit administration, municipal government, and education. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism with a concentration in Public Relations from California State University, Chico, a Master of Science in Management with a Leadership Certification from the University of Maryland Global Campus and is currently pursuing a Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership in Higher Education from Delaware State University.

Her leadership style is defined by her ability to see the broad picture and her willingness to take calculated risks. She is a visionary who is constantly in search of novel and inventive ways to improve her life and the community around her. She is driven by her faith and relationship with God, as well as her desire to help others attain their fullest potential. One of her favorite quotes from Bob Nelson is, “You get the best effort from others not by lighting a fire beneath them, but by building a fire within.”

Her marriage to her best friend and favorite musician, Minister Brian Cunningham, is one of her most significant accomplishments. When she is not working or attending school, she can be found performing with the Brian Cunningham Project at private or public events, cruising or spending quality time with her family.

Bhatt, H., & Hughes, T. A. (2019). Book Club review: The Story of My Life (by Helen Keller). Practical Neurology, 19(5), 456-456.

Burgstahler, S. E., & Cory, R. C. (Eds.). (2010). Universal design in higher education: From principles to practice. Harvard Education Press. Kattari, S. K. (2015). Examining ableism in higher education through social dominance theory and social learning theory. Innovative Higher Education, 40, 375-386.

Mole, H. (2013). A US model for inclusion of disabled students in higher education settings: the social model of disability and Universal Design. Widening participation and lifelong learning, 14(3), 62-86.

Null, R. (Ed.). (2013). Universal design: Principles and models. CRC Press.

Online learning (e-learning) describes any form of pedagogy delivered using digital technology. Such methods incorporate visual graphics, text, animations, videos, and audio. In addition, online pedagogy can also facilitate group learning, and the assistance of instructors within specific fields (Huseinović, 2022). It is fair to say that online learning gained stronger wings after the onset of theCOVID-19pandemicaseducatorstransferred the classroom from face to face to online. According to Wildana et al. (2020), the online learning models used during the COVID-19 pandemic equipped students with knowledge in a similar way to face-to-face learning. However, online learning provides more experience will be the importance of process learning that balances the development of time and technology based on self-regulatory capabilities, which is owned by each student. According to Wildana et al. (2020), the regulations enforced by the head of an educational institution are most important when delivering online learning. In this article, I am seeking to establish how educators and students can build a strong community online adapting basic practices used for social media engagement.

Social media can be broadly defined as the set of interactive Internet applications that facilitate (collaborative or individual) creation, curation, and sharing of user-generated content. At its core, social media involves interactivity between users. This interactivity can be synchronous, asynchronous, oneto-one, one-to-many, situational, or rooted in exhibition artifacts (Hogan, 2010). Online learning, like social media, enjoys some

commonalities in as much as they are different. They both have the power to connect people across distances and cultures through digital technologies. Like online learning, social media is dependent on Internet connection to function effectively. There are varying issues that affect one’s Internet connectivity from socioeconomic conditions to culture and tradition. Universities like Delaware State with its high volume of online learning offerings must consider these issues when delivering programs online especially to students in developing countries that may be behind in deploying digital technologies.

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the power of connections despite distancing made possible through digital technologies, whether it is social media or the online classroom. There are notable differences between social media and the online classroom, one being the fact that social media is highly individual creation, curation, and sharing of user generated content (insert source), while the online classroom is an exchange of information from facilitator to students, student to student and students to facilitator. The point I make here is that political participation, the spread of ideas, and the inclusion and exclusion of voice have most certainly been affected by social media, but these processes are very much rooted in an existing physical, political, and cultural reality (Rui, Stefano, 2012). The online classroom seeks to balance these issues as the lecturer/facilitator enables participation through inclusive and engaging methods that ensure active student participation and engagement.

I am exploring ways of connectedness, more so, than connectivity in this paper based on my personal experience in the online classroom so far. I love being around people, and so my initial apprehension to studying online was that I would not feel connected with people from various parts of Jamaica and the wider world from different backgrounds. In survival mode, I resorted to what I knew and that was how to show up online. Social media affords us a presence through its various platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Tik Tok and Snapchat. How we show up for classes online is very much how we show up on social media, and we can curate a look for ourselves and our environment on camera. Leary et al. (1995) defines this behavior as self-presentation. Self-presentation is, ‘‘The process of controlling how one is perceived by other people’’ (Leary, 1995, p. 2) and is key to relationship inception and development. To construct positive images, individuals selectively provide information about themselves and carefully cater this information in response to others’ feedback (Goffman, 1959). How do we present self in the online classroom as we do on social media? Have you ever received those posts on social media that insisted you demonstrate your friendship by reposting or leaving a comment? Do you ever respond to them?

My personal confession is that I sometimes find the posts annoying, mirroring the tradition of chain messaging, and suggesting that the sender is desperately in need of attention and so I usually ignore them. As I spend more time on social media, I recognize that it is rewarding to take the time to respond, share, copy and repost especially when it is from someone I engage with offline consistently. Taking the time to respond sends a message to the community that you care and are in tune with what is happening around you. In the same way we respond to each other on these social media platforms, it is important that students engage each other in the online classroom. The online classroom allows students

and faculty to engage each other synchronously or asynchronously in various locations across the world and time zones. In this classroom a community is built, and in our case at DSU, this community is the formal space a cohort meets until the end of the respective program. A community is firstly about people sharing with each other. It is about having a conversation. It is a living thing. It is there for you when you need guidance or to cheer you along. Creating or building an online community takes as much time as real-life relationships take to develop and takes effort to flourish. I would like to share some ways we can build a healthy DSU online community using the social media template for the classroom.

Whether you are on social media to maintain contact with friends or are business wishing to engage customers, building a presence online requires active participation. Social presence is the ability of participants to establish themselves as real in a virtual environment (Garrison et al., 2010). Social media platforms allow individuals to maintain a presence online and participate in conversations in and outside of their cultures. In the online classroom, according to Garrison, social presence is cultivated when students are supported in being authentic in the virtual classroom. Being authentic means being allowed to share aspects of their personal and professional lives in the online classroom and is highly dependent on lecturer facilitation. The simple action of turning on one’s camera establishes to those present that you are in the room and prepared to participate. In the very same way we share photos and videos of ourselves on the social media platforms, we can show our presence using the reaction buttons, messaging in the chat, or speaking as means of responding to another student’s presentation. It demonstrates that you are online and fully present and encourages others to do the same.

How often do you post on social media? What do you post? Do your posts give an accurate reflection of who you are and what your interests are? Being consistent on your social media platforms allows your audience to trust you (plus it lets the algorithms know your interest and keeps you in the loop). It is really no different in the online classroom. You are building a community with others who share the same interest and so staying online and not participating in discussions may send a message that you are not there. Staying silent may send a message that you are not paying attention, while responding, on the other hand, expresses that you are interested and ready to learn. In the online classroom, limited opportunities to interact with peers in person may increase feelings of distance and may undermine students’ sense of connection in distance programs (Koslow & Piña, 2015). Cultivating a strong community culture online is heavily dependent on teacher/ facilitator support. Social media participation, by connecting and activating potential ties, is instrumental in increasing “bridging” social capital, such that users acquire access to new perspectives and a broader range of information, resources, and support than that which is available in close-knit networks. Similarly, intense social media usage predicts “bonding” social capital, or an increased closeness with existing ties (Davis, 2016). The online classroom can create this connectedness through consistent and conscious communication led by teacher/ facilitator utilising the available technologies like breakout rooms to facilitate group discussions and sharing.

Communities are about sharing, and social media platforms are the ultimate democratic space where everyone has a voice and has equal opportunity to share their opinions no matter how controversial. The point here is that participation, the spread of ideas, the inclusion and exclusion of voice, has most certainly been affected by social media (Davis, 2016). In the same way, the online classroom is a space where all voices should matter, and the space given to ensure that all ideas are heard. Cultivating community online must consider the diverse needs and backgrounds of students and move beyond simply giving a lecture. One lecturer interviewed for a study in an online doctoral program shared “that an overreliance on lecture was not productive for an online environment: Teaching online is not just, “Hey! I’m gonna turn my computer on and my camera, and I’m just gonna be able to teach an online class.” If you are lecturing for two hours, then that is a complete waste of everybody’s time. If you are not giving students an opportunity to have a voice and an opinion, it is completely a waste of time for students (Davis, 2016). Diversity and inclusion involve people understanding each other, considering that everyone is unique, practicing simple tolerance of individual differences, and embracing and celebrating the rich dimensions of diversity contained within everyone (Dhawan, 2020). Whether it is language, time zone, or lived experience, the online classroom must be considered as ways for diverse voices to be heard, and all students to be included in classroom dialogue

Studying online requires discipline and commitment and most importantly engagement. The experience for both teacher student in the online classroom requires a range of strategies to ensure inclusion and facilitate diverse groups and social media, and its social media and robust engagement infrastructure are exemplary templates to mirror as we shape the online learning experience.

Coleen Douglas is a first-year student in the Educational Leadership (EDD) Program at Delaware State University. She is the currently the Director of Marketing and Communications at the Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts in Kingston, Jamaica. She is a leading voice in marketing arts and culture and has significant experience in marketing, public relations, branding, radio production and event management. She is a strong champion for arts education and creative industries and is actively involved in music as a publicist and board member of the Jamaica Reggae Industry Association. She is also a member of the Board of Directors at the Trench Town Polytechnic College.

Davis, J.L. (2016). Social Media. The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication. 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118541555.wbiepc004.

Dhawan, S. (2020). Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. Sage Journal, 49 (1), 5–22. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/ 0047239520934018.

Dhull, I. & Sakshi M. (2017). Online Learning. International Education and Research Journal 3(8). 32-34.

Garrison, D. R., Cleveland-Innes, M. & Fung, T. (2010). Exploring causal relationships among teaching, cognitive and social presence: student perceptions of the Community of Inquiry framework. The Internet and Higher Education, 13, 31–36

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Doubleday.

Hogan, B. (2010). The presentation of self in the age of social media: Distinguishing performances and exhibitions online. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 337-386

Huseinović, L. (2022). The relationship between digital competency, learning styles and learners’ perception of traditional versus technology-assisted language learning. MAP Education and Humanities. 3(1). 17-30.

https://doi.org/10.53880/2744-2373.2022.2.3.17.

Koslow, A., & Piña, A. A. (2015). Using transactional distance theory to inform online instructional design.

Instructional Technology, 12(10), 63-77

Leary, M. R. (1995). Self-Presentation: Impression Management and Interpersonal Behavior. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Mirza, M.H., Bhuiyan, M. & Hossain, M. E. (2017). Impacts of culture and socio-economic circumstances on users’ behavior and mobile broadband technology diffusions trends. Computer Science Computers in Society. 473-479.

https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1708.02798

Ramirez, A., & Walther, J. (2009). Information seeking and interpersonal outcomes using the Internet. In T. D. Afifi & W. A. Afifi (Eds.), Uncertainty, information management, and disclosure decisions (pp. 67–84). New York: Routledge.

Rui, J., & Stefanone, M. A. (2013). Strategic self-presentation online: A cross-cultural study.

Computers in Human Behavior, 29(1), 110-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.022

Wildana W., Maimunah, I., Dewi, E. & Rofiq, Z. (2020). Student’s responses on learning in the early COVID-19 pandemic.

Journal of Education and Teacher Training

In Japanese culture, Seijin no Hi or Coming of Age Day marks an important milestone in a young adult’s life. This is a special day celebrated on the second Monday in January every year when young adults are celebrated as they transition into adulthood. At the age of twenty, recently changed from eighteen in 2022, they are legally and officially bestowed the privilege of doing the things of a fully-grown, mature individual.

J. Arnett (2004) theorizes “Coming of Age” as “emerging adulthood,” a distinct developmental period in the life course for many young people in industrialized countries, lasting from age eighteen to mid or even late twenties. During this period of instability, there is a focus on self and possible life directions are explored. Another interpretation of “Coming of Age” is becoming a culturally, socially aware, and responsible individual. Interestingly, and contrarily, through my experience, I have watched students transform from being focused and studious teenagers under the ever-watchful gaze of their parents to carefree, alcohol-drinking, partying, yet somewhat responsible adults, living in their own apartments working part-time to support themselves. They become tax-paying, enfranchised individuals who contribute to the uplifting, and sometimes even the breakdown, of their society. Newfound freedom for our new adults can be only what they make of the exhilarating feeling of independence.

How does this relate to higher education? In the last two to three decades higher education institutions have made strides toward what researchers call internationalization, which in its own way is higher education institutions’ own “Coming of Age.” Propelled by the growth of a demographic increasingly interested in

higher education, and the growing knowledgebased economies across the world, institutions have begun the process of transitioning their schools toward internationalization. Though a costly venture, international students have ventured across borders for centuries in pursuit of knowledge, taking advantage of scholarships and other funding opportunities. This phenomenon was termed the “internationalization of higher education institutions” by some researchers and has taken root in the scholarship since the 1990s (Gürüz, 2008). In fact, it is seen today as the “central motor of change” in higher education (Egron-Polak & Hudson, 2014), the kind of change that has allowed thousands of international students to move without limits to study at some prestigious universities. The internationalization of education involves links between higher education and economic and social development, much like the newly matriculated adults into the Japanese society on Coming of Age Day. As adults contribute socially and financially to the society in which they are a part, international students add not just their cultural marks to the university community, but also add to universities’ coffers as international fees are significantly higher than those of domestic students. There seems to be a correlation between the benefits of internationalization for both the international students and the institutions. While students get the opportunity to study in another country and impart knowledge of their own cultures, more recent studies suggest that universities get to reap the benefit of higher tuition and diversifying their population. Indeed, Bartlett and Fischer (2013) noted that large numbers of Chinese students have been flooding US universities, the vast majority of whom are from “one child” homes

and whose parents can pay tuition in full, thus highlighting the idea that Asian students can be seen as a burgeoning source of income for higher education institutions in the US.

Cantwell, in his 2015 article, posits that as universities across the world become more enterprising, the impulse to attract international students to generate revenue may have increased in many countries. He notes that both the popular press and academic literature have been replete with accounts of how individual private higher education institutions and national systems have generated income through international student recruitment. On the other hand, the international student market has been large and growing, with over four million students studying outside of their home country (OECD, 2013). Irrespective of the exorbitant fees, many students are opting to study overseas. Interestingly, the Hechinger Report of September 2018 alludes to a decrease in US college-aged students opting to attend universities which has given rise to a high Asian-American demographic in higher ed institutions. Students enrolling from India and China have a high attachment to higher education (Barshay, 2018). In addition to the financial and cultural benefits of having these international students enrolled, universities rely on these student numbers to maintain enrollment statistics. This suggests that diverse student populations inherently contribute to student learning outcomes and ultimately strengthens the institutions’ inclusivity agenda.

Indeed, the US Department of Education denotes in their 2016 report that students report less discrimination and bias at institutions where they perceive a stronger institutional commitment to diversity.

Like the blossoming of teenagers into adults and the celebration of their “coming of age,” universities are to be lauded for their move to diversify their population through internationalization. Interestingly, universityaged students, whether from China or India, enter universities as “emerging adults” at an age when they are adaptable to not only the culture of other countries, but also to institutional cultures. This means that while they impart and learn the new country’s culture, they will also adapt to institutional cultures, thus creating a cycle of social, cultural, and financial interconnectivity among institutions and students. Today’s Asian international students have contributed tremendously to the diversity agendas of many US higher education institutions, and in return, these universities have created the proverbial “circle of trust,” a welcoming domain where international students are free to be themselves while learning the ways of a new land.

Sasha-Kay Osbourne-Weir is a part-time lecturer at Utsunomiya University in Tochigi, Japan, and is in the first year of the Educational Leadership (EdD) Program at Delaware State University.

References

Arnett, J. (2004). Emerging Adulthood. (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. Barshay, Jill. (2018, September 12). College Students Predicted to Fall by More Than 15% After the Year 2025. The Hechinger Report https://hechingerreport.org/college-students-predicted-to-fall-by-more-than-15-after-the-year-2025/.

Bartlett, T. & Fischer, K. (2013). The China Conundrum. In D. Araya, P. Marber (Eds.) Higher Education in the Global Age (pp. 140-152). Routledge.

Cantwell, B., (2015). Are International Students Cash Cows? Examining the Relationship Between New International Undergraduate Enrollments and Institutional Revenue at Public Colleges and Universities in the US. Journal of International Students, (5) 4, pp. 512-525.

Egron-Polak, E. & Hudson, R. (2014). Internationalisation of Higher Education: Growing Expectation, Fundamental Values. IAU 4th Global Survey. International Association of Universities.

Gürüz, K. (2008). Higher Education and International Student Mobility in the Global Knowledge Economy. (2nd ed.). State University of New York Press. OECD. (2013). Education at a Glance 2013: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2013-en.

U.S. Department of Education. (2016). Advancing Diversity and Inclusion in Higher Education. Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development & Office of the Under Secretary. https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/research/pubs/advancing-diversity-inclusion.pdf.

An Investigative Study on Content Differentiation Life’s journey is more fulfilling with different experiences!

by Donna-Neisha Steele, M.Ed.Introduction

“Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) is a field of study which emphasizes acceptance of, and respect for, individual differences in ways of being” (Wallace, 2023). These principles are also applicable in education, as educators should embrace the range of differences within the classroom and utilize all available resources, including technology, when catering to students’ needs. Differentiated Instruction (DI) is the educational application of these DEI principles, as students thrive in instructional environments where teachers recognize, respect, and respond to their diversity (Wallace 2023). Consequently, there must be a shift from the “one size fits all” approach, and the need for differentiation must become more apparent. The students that teachers teach are not merely blank slates. For many educators, the main aim of teaching is to achieve the goals and objectives outlined in classroom instruction. While this is important, giving all students equal opportunities to realize these goals and objectives is equally important. In a typical classroom setting, students are charged with achieving the same learning objectives but their personalities, skill levels and experiences differ and as such, they are to be taught differently if they are to maximize their full potential; teachers must utilize differentiated instruction in carrying out their instructional practices. Tomlinson 2001 defines DI as a process where the teacher proactively “plans and carries out varied approaches to content, process, and product in anticipation of and response

to student differences in readiness, interest, and learning needs” (p.10). DI is not only a special education philosophy but applies among ‘typical’ students in general education. It is merely an inclusive way for teachers to recognize and react responsively to their students’ experiential background, readiness level, language, and interests (Hall, 2002). This comparative study investigates DI’s impact on student achievement at a primary school in Jamaica. The study sought to highlight the strategies used to support students and determined the extent to which it positively influenced their performance and promoted a general understanding of the content taught.

Literature ReviewAccording to Katz (2000), when a teacher tries to teach something to the entire class at the same time, chances are a third of the students already know it, a third of the students will get it, and a third of the students will not get it. So, in essence, two-thirds of the students’ time will be wasted. Instructors must ensure they minimize the chances of wasting anyone’s time, including their own. Therefore, the content that instructors seek to impart to their students becomes very important as it relates to catering to the individual needs of all students. The content taught becomes vital; it highlights specifically what the teacher wants students to know (knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values) during a given unit of study or a single lesson (Bush, 2006).

“The concepts of curriculum or content differentiation and instruction have been evolving through theory and practice” (Betts, 2004, p. 190). This statement put forward by Betts suggests that curricula given to instructors have already been differentiated, but could he also be suggesting that instructors themselves do the differentiating? The content used during instruction can be found in prescribed curriculum guides, syllabi, course outlines, and other relevant materials, including but not limited to textbooks pre-approved by college boards, Departments of Education, and other accredited institutions. From experience, these curricula and syllabi are designed to be inclusive of all students despite their differences. Betts (2004) further affirms this by stating that “prescribed curriculum involves basic knowledge and skills for all children.

However, the prescribed curriculum does not include the complexity and level of challenges for all students…” (p. 190). Differentiating the content should be prioritized during instruction if all students are to benefit from what is to be imparted. Therefore, the content strategies utilized during instruction should be explicit and inclusive while targeting diversity within these spaces. Tomlinson (1999) recommended the following strategies for differentiating content at the primary level: (1) utilization of reading resources at varying readability levels; (2) transferring text materials to different formats (e.g., tape); (3) use of vocabulary lists at students’ readiness levels; (4) presentation of information through varying means (e.g., audio, visual) (5) utilization of peer buddies; and (6) incorporating small groups instruction to reteach concepts to at-risk learners, or using interestspecific content to engage advanced learners.

There are many ways that instructors can differentiate the content of a lesson based on the student’s readiness levels, learning profiles, and interests. These ways of differentiation may sometimes overlap; however, Bush (2006) indicated that while it might be challenging to accommodate all students at all times based on their interests, ability, and profile, educators must

acknowledge that differences exist within the classroom. An inclusive pedagogical approach, therefore, becomes necessary if we are to ensure equity in education.

The study utilized an experimental research design with a QUAN-qual approach, which saw the sample divided into an experimental and a control group of thirty students. A quantitative analysis of students’ pre and post-test and survey results were used to determine the relationship between content-related strategies and student achievement. Interviews and classroom observations were conducted during the qualitative design phase of the study. Both methods allowed for triangulation which was supported by the findings which were guided by the following research questions:

1. How is the student’s achievement level affected by DI?

2. Is there a correlation between the achievement of students and the implementation of DI?

3. What DI strategies were used to ensure adequate student achievement?

4. How does the DI of the content differ across male and female students’ achievement?

The study’s findings suggested that DI positively impacted the students’ achievement within the primary school. Data gathered from both the quantitative and qualitative analysis provided evidence in support of DI and its positive learner outcome. The effect of DI on students’ achievement was very significant. Post-test results revealed that the students taught using the DI approach outperformed those taught using the traditional one-size-fits-all method. Teachers utilizing the DI method were observed using peer buddies, small group instruction, and incorporating varied

readability resources. The study further revealed that female students’ performance exceeded their male counterparts in both the pre-test and post-tests, despite being smaller in numbers. The overall results were consistent with Koeze’s 2007 study, which asserts that DI positively affects student achievement. A study by Grimes and Stevens (2009) also supports the notion of DI as an effective strategy for improving student achievement. It also increases the students’ desire to improve in specific subject areas and confidence in their abilities.

The study brought the relevance of DI practices to the Jamaican education landscape. It outlined the benefits of utilizing such an approach; if students are to be successful in school, their individuality and diversity must be accepted, respected, and factored into planning for learning. In addition, inclusive strategies must be implemented to improve academic performance while ensuring equity for all. It must be noted, however, that infrastructural improvement and access to adequate resources would have to be secured for full and effective implementation of DI in Jamaican primary schools. Several implications arose from the study, chief of them is the need to effect institutional changes regarding pedagogy and learning and the development of policies that promote DEI for effective classroom practice on twenty-firstcentury students.

Donna-Neisha Steele is currently a Special Educator and an Educational Consultant by profession. She has been in the field of Education for approximately 16 years and has worked at all levels, both locally and internationally. She has experience in teaching, consulting, testing, assessment, textbook review, curriculum and program development as well as teacher training. Ms. Steele is an avid volunteer to causes that promote equity for all. She enjoys carrying out research studies. Her most recent research study is entitled ‘The Psychological Effects of COVID-19 on Students, Parents and Teachers.’ Ms. Steele is also the founder of Special Education in Jamaica, an initiative that seeks to inculcate, advocate and educate the general public as well as stakeholders about everything and anything associated with special education and the student with a special need. Her overall goal as a Special Educator has always been to bring awareness as well as to advocate for those who require special education services while providing remediation, assessment, evaluation and consultative service.

Currently, Ms. Steele is working on several projects, including her brainchild, the Enhancing Students Experiences through Writing (EnSEW) project. Academically, Ms. Steele holds a DipEd in Special Education, Bachelor of Science in Sociology and Psychology and a Masters in Education in Measurement and Evaluation. At present, she is pursuing postgraduate studies toward obtaining a Doctorate of Education Degree (EdD) in Educational Leadership.

Betts, G. (Summer 2004). Fostering autonomous learners through levels of differentiation. Roper Review. 26(4), 190-191

Bush, G. (2006, November). Differentiated instruction. School Media Activities Monthly. 23(3), 43-44.

Grimes, K., & Stevens, D. (2009). Glass, bug, mud. Phi Delta Kappan, 90(9), 677-680. Hall, T. (2002). Differentiated instruction. Wakefield, MA: National Center on Accessing General Curriculum.

Katz, L.G., & Chard, S.C. (2000). Engaging children’s minds: The project approach. (2nd ed.). Stamford, CT: JAI Press.

Koeze, P.A., (2007). Differentiated instruction: The effect on student achievement in an elementary school.

Master’s Theses and Doctoral Dissertations. Paper 31. Retrieved from http://commons.emich.edu/theses/31.

Tomlinson, C. (2001). How to differentiate instruction in mixed-ability classrooms. Alexandria, VA: ASCD Publications.

Tomlinson, C. (1999). The differentiated classroom: responding to the needs of all learners.

Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. ED 429 944.

Wallace. L. (2023, April 5) Personal Communication. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Specialist.

Canadian Centre for Diversity and Inclusion. https://ccdi.ca/.

The God Brothers of Delaware is a nonprofit student organization that was created with the purpose of cultivating an environment for Black men to develop themselves through selfless service on campus and the local community. Founded in 2015 by Delaware State University alumnus Alexander Hackett, the organization takes its name from its sister organization, the Fairy God Sisters. The God Brothers of Delaware’s mission is centered around the idea, “All it takes is one.” The objective is to make real and meaningful that it only takes one person to make a significant change.

The organization has accomplished several impressive initiatives this academic year, including over six hundred hours of community service. One of the most significant achievements of the God Brothers was working with the Delaware Center for Justice to provide expungement resources to low-income communities in Wilmington, Delaware. The organization also created initiatives like “Faculty Friday” to honor faculty members and worked with Public Safety and the Chief of Police to establish routine campus cleanups after school events.

This year, the organization has set a goal for the development of 360 men on campus. God Brothers strive to be a resource for men on campus who may not have had a structured lifestyle back home and aim to instill positive characteristics in them, so that they can be positive contributors to their communities.

In addition, God Brothers have taken it upon themselves to raise awareness about STDs and STIs with their annual “Pizza and Protection” event, in collaboration with the Epsilon Alpha Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority Incorporated. The organization has

also collaborated with Delaware State University’s Student Government Association and the DSU Chapter of the NAACP to orchestrate “The Black History Museum: The Experience,” which included student re-enactments of significant figures in Black history, a pop-up shop for small businesses, and a fashion exposé. The whole event was a massive success, with over six hundred students attending the four-hour event.

In conclusion, the God Brothers of Delaware is an organization that has made a significant impact on the Delaware State University community. The members’ dedication to cultivating an environment for Black men to develop themselves through selfless service is inspiring and necessary. The impressive initiatives they have accomplished this academic year, including community service, awareness events, and collaborations, demonstrate the organization’s commitment to making a difference. The God Brothers’ efforts have not gone unnoticed, and they continue to be an essential resource for men who are committed to making a positive difference on campus through serving others.

The God Brothers inducted over fifty Delaware State University men into the organization on Sunday, February 26, 2023. This accomplishment showcases the significant impact the organization has had on campus and highlights the dedication of its members to making a positive change in their community.

Caption: The Locked-In Program, Chess Match |Fall 2022

Caption: The Locked-In Program, Chess Match |Fall 2022

Chris Searle, an anti-racist, British historian, has claimed that the twentieth century witnessed two successful revolutions, one that is well known— Russia’s 1917 Glorious Revolution that ended the reign of the Russian monarchy—and the other relatively unknown and apparently destined for history’s dustpans. The Trinidad Youth Revolution remains obscured for its toppling an institution of British imperialism and colonialism. Many people, including Trinbagonians, are unaware that hundreds of Trinidadian high schoolers in 1971, 1972, and 1973 jeopardized their lives and future economic well-being to end the British hegemony of the Caribbean educational system. They, like many students at DSU, past and present, sacrificed their health and well-being for positive change, and it was overwhelming. I was one of them.

While the Black Power Movement was being influenced by Trinidadian Stokely Carmichael living in New York, the fervor for change fueled Trinidadian secondary school students—all teenagers—to stake their own claim. Our activities remain undocumented, having been overshadowed by the bigger revolution owned by the university students, which itself changed the course to Trinidad and Tobago’s (T&T) history, as narrated in the 2010 documentary, Remembering A Revolution, and post-screened on the DSU campus in 2011. Elizabeth Topp, Trinidadian Canadian and one of the directors, was invited by the Project Advance (renamed College Advance) Learning Communities program. Therefore, her visit was recorded and archived by our Mass Communication Department. However, even she was taken aback when I asked her about NUFF, which stands for National Union of Freedom Fighters. She admitted that she was aware only of the activities of the National Joint Action Committee, commonly known as NJAC, the subject of her documentary. I informed her privately about NUFF, which I now wish to share publicly.

NUFF was led by organizing students from Diego Martin Secondary School who embraced the acronym for its effective capturing of their emotions, perspective, and momentum of the country’s revolutionary febrile. “Nuff said” in Trinbagonian lingua franca means, “Enough said. We done talkin’ and we takin’ action.” NUFF as an organization remained

amorphous and its membership non-defined.

This was deliberate because the organizers chose invisibility to the country’s colonial apparatus in order to survive.

They were aware of the historic names of Julien Fedon and Frances Danglade of Grenada’s 1795 revolution against the British and French, and whose names were stricken from Grenada’s historical records. In 1970, we all had seen how T&T’s colonial government had solicited and gained military support from America and executed their power with unimaginable heavyhandedness and cruelty. The university students and a handful of very brave high schoolers who declared themselves to be guerillas were gunned down on the Diego Martin hills, their bulletriddled bodies displayed on the front page of the national newspapers as a warning to other young people that such would be their fate. It was history repeating the days of enslavement. NUFF members looked and learned.

Their operation would be both amorphous and asymmetrical in its strikes against the government and the private enterprises owned by Americans, Canadians, the British, and other European companies. Hence, when NUFF struck forcefully with Molotov cocktails to effect massive damage to buildings, no activity could be traced back to anyone. No membership list existed. No headquarters could be identified and raided. No arrests could be made. Consequently, no one can say with any measure of certainty how many high schoolers had pledged loyalty to NUFF whose biggest target was the institution that stunted free thought and intellectual development: the Ministry of Education.

NUFF’s organizers, whose perspective was undoubtedly influenced by the university activist students with whom they interacted, made it clear that they thought the 1966 Independence had become a joke because virtually nothing had

changed. All the colonial powers retained their firm control of politics, the economy, education, religion, and culture. Prime Minister Eric E. Williams had been elected on the promise of uniting and empowering all Trinbagonians; however, he was emerging similarly to all the other three Caribbean heads: Alexander Bustamante (Jamaica), Forbes Burnham (Guyana), and Errol Barrow (Barbados). These four leaders were merely puppets of colonialism. They were four tops spinning into their sandy beaches, tossing sand into their people’s eyes to blind them to reality. Enough was enough!

NUFF members calculated that the path to change laid in education. Enough with Williams’s showy celebrations of Divali, Eid-al-Fitr, Double Ten, Yom Kippur and Hanukkah, and Shango under the “All ah we is one” umbrella. Williams functioned merely to pacify and manage resisters. True change could be realized only through a complete overhaul of education with a curriculum that allowed for the studying of all literatures, including those by Caribbean writers and scholars: Trinidadians Earl Lovelace, V.S. Naipaul, C.L.R. James, among others; Barbadians George Lamming, Frank Collymore, and Edward Brathwaite, among others; and Jamaican Herbert de Lisser, among others. They wanted Caribbean and American history to include the names of Fedon, Danglade, Toussaint L’Ouverture, Nat Turner, and the more recent oppressive and intimidating Greenwood, Tulsa bombing. While working at a Wall Street firm in Lower Manhattan in 1977, I inquired of this bombing of a co-worker, a Black Cuban American. Because she was born in Brooklyn and prided herself in knowing all about US Black history and had never heard of the bombing, she accused me of making things up about US history. She then proceeded to teach me about Barbadian American Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman to run for US president.

To return to NUFF, its students’ preeminent demand was for Martiniquan Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth to be required reading for all high school students. “Nuff said and done! Time for true change for “ah we people!” I learned about their demands for a new curriculum and Caribbean-based examination for graduating high schoolers from the only one meeting that I secretly attended to witness what was being whispered around my all-girls high school. The passionate speakers at that meeting were all emphatic: The time for change had come!