MOVING LIGHTS Chris Noelle, aka TOFA, on cros sing creative boundaries in search of something new

Are you working on something interesting at the moment?

I’m working on a new mapping installation, a huge press conference in Vienna, where we will be providing the content for the projection mapping.

Projection mapping. What exactly does that mean?

Imagine you have a huge building and you want to project images onto it. We rebuild that structure in 3D and project onto it. We can make a living surface on any kind of object.

Sounds like a big technical challenge?

Oh, you need to know where the projectors are… Where the people are standing… And the theme of the event. Then you start on research, and only later get into production. There’s a lot of research first.

We produce video content and most of it is generated in 3D, there may also be a mix-down with After Effects and live footage, but this is totally different to the lightpainting.

Your lightpaintings have something magical about them, like capturing ghosts, how does it work?

It’s like when you have long exposure photos of cars driving by, and their tail lights make these trails.

So, basically, you put your camera on manual mode, and then you can act in front of the camera, or capture environments where there’s moving, or static, light.

Inside your scene, you are never visible because long term-exposure just erases everything which is in motion.

Has it taken a long time to master the tools used to manipulate light?

It’s a permanent learning process, because the software is never finished. Each company comes up with a new version every year. So you have to train your skills again and again… And again.

On some software, it’s easy. On others, it’s quite hard, particularly when you get into the coding - that’s not my favourite. But with all these new features and these technical

skills, you either have to find someone in your network who is a reliable partner, or you have to learn it for yourself.

Do you enjoy the learning process?

Well, I wish I could have a couple of interns who would do just what I want! But that involves cost, and if you’re freelancing, you have to manage everything on your own.

That means software, but you have to know the hardware too. You have to know how to locate any errors that might have crept into the project - and how to solve them.

And if you don’t have the ability to solve it by yourself, you must have the right phone number for the guy who could help you out.

When you move a project from the computer to the real world, is that a tricky process?

Well, I started with Photoshop version 1.0. But I grew up with analogue cameras.

So, I have the advantage that I learned from the analogue gear, how to solve problems, or to find solutions, before I switched into the digital world. For the younger generation this is quite hard, because they don’t have that experience from the analogue times.

It’s an advantage if you have an insight into both worlds. Because a lot of filters, for example, that you see today on TikTok or Instagram, they rely on analogue gear, on old mixing recorders and devices for video effects. All that comes back around eventually, and if you can reproduce it with an analogue machine, it’s even better.

Do you have a basement full of cool old machines?

Sometimes I think, “Now, finally, I can sell that thing. I’ll never need it again.” But a couple of years later, I always come back to wishing I hadn’t sold it!

At home, I try to keep things tidy, there’s no cabling lying around. But I do keep getting new gear. For example, I recently bought a really interesting little machine, which is a Polaroid transfer printer. You just lay your iPhone on top and away you go. So I’m also working with a new technique called Polaroid transfer. You cut out the Polaroid, put it in hot water, and transfer the gel print of the Polaroid onto watercolour paper. And then you have a unique artwork of a Polaroid, but which came out of a digital device. Getting an analogue output from the computer. That’s a big theme for me.

You move very freely between digital and analogue. What do you discover in that process?

When I work on art projects, I always like to get something which doesn’t depend on power.

Basically, if you have a print, or you have a picture in mind, and you have it stored on your hard drive, it will get lost. After 20 years my hard drive is now around 16 terabytes!

And all of that has to be somehow managed and sorted. So I prefer to have some of the things I love as real prints, as pieces of art.

[top] Flying Steps, 2007

Shooting with the B-boys of Flying Steps at an abandoned industrial zone. "Some nice reflections too, it had just rained."

[bottom] Festival of Lights, IHC Tower, 2007

At the Festival of Lights, Berlin, Chris’ first hugescale Pani projection artwork was thrown onto the IHC tower.

I’M A BIG FAN OF NOT FAKING THE PICTURES.

YOU IMMEDIATELY KNOW WHICH LIGHTING SETUP CREATED WHICH FEELING.

[left page] Nordbahnhof, Selbstportrait, 2007

Mirrored photo at Berlin Nordbahnhof with the Berlin wall and TV tower as backdrop. "First the typo was painted into the air, then a colorfoil flash was used to freeze my ghost in the exposure."

[top] Yeah, Platoon, Berlin Mitte, 2008

“A big work light with a simple on-and-off switch is great for bold typographic letters.”

[bottom] Styrofoam Object, 2009

Studio setup of a styrofoam sculpture combined with various light sources. “The white picks up the reflections while you move your hands around the object, without touching it.”

BUT ONCE I’VE SEEN ENOUGH OF A PARTICULAR SCENE, I JUST MAKE A CUT AND SWITCH TO SOMETHING ELSE I PREFER.

[left page] Streettypo 002, Tokyo, 2009

Lost on a playground in the concrete jungle of Tokyo at nighttime.

[right page] Vasarely RMX, 2010

A polyurethane sculpture created from the cutouts of a Vasarely stencil, placed on mirrorfoil and lightened with a LED ballpen.

[left page] Streettypo 002, Tokyo, 2009

Lost on a playground in the concrete jungle of Tokyo at nighttime.

[right page] Vasarely RMX, 2010

A polyurethane sculpture created from the cutouts of a Vasarely stencil, placed on mirrorfoil and lightened with a LED ballpen.

The crossover between digital and analogue is something we are dealing with as a society.

That’s the core of my work. The conversion process between virtual and real world. You always need to move between analogue and digital skills. Each of those two worlds triggers the other one.

It’s like an intentionally imperfect translation process

I love errors! For example, if you do that Polaroid transfer technique, you start with a really clean graphic on the computer, transfer that to the iPhone and then print it with the Polaroid. Then, during that transfer process, I can just take a straw and push the colour gel around in the water. It behaves like folded paper and becomes something totally different. This all relies on experience and errors.

You’ve been involved with the music scene for a long time too. How’s music played into your work?

I’ve been producing music since the ‘90s. Today, it’s more on the computer, but I still have a couple of synthesisers hanging around too.

And I know how to get things working together somehow. If you’re making documentaries, you need all the audio working as well as the visuals, if you want to publish it.

I’ve been into electronic music since the mid ’90s. In fact, I started my visual career doing club visuals.

Back then, I was using two VHS recorders to play visuals for the crowd at techno parties.

That must have been an exciting time?

It was crazy! For example, I worked from 2007 to 2013 as art director in the oldest techno club in Berlin. It’s called Tresor . It’s all about diving into the music with a lot of fog machines, strobes, minimalistic lighting and fourto-the-floor beats! When you work in that environment, you meet a lot of musicians, artists, crazy people.

One of the great things about doing the night shift at a club is that you learn everything about the essentials of light. Then, coming back into your own creative process you immediately know which lighting setup created which feeling. You can take that knowvledge with you and transfer it directly to your artwork.

You were engineering people’s emotional state, in a way?

When you provide the visual experience for an audience, you have to be really aware of the effect you’re having, because too much light will disturb the entire feeling. Too little light is just as bad.

I’m a big fan of keeping it simple. So for me, it’s black, white and one colour.

Before that, you were a trials bike champion, how did you get from there to the visuals?

The trials bike riding gave me a chance to be in front of the camera, because they made documentaries about me, back in the early ‘90s.

One camera producer became a really good friend of mine, and he asked me, ‘Hey, don’t you want to come

with me on a trip and do some filming for other extreme sports?’

That’s how I got into the editing part of creating films. By working on documentaries about other extreme sports people. And then with the editing of the film, you had to learn special effects, animations and so on. Editing animations led to club visuals.

People usually have difficulty switching from one field to another. But it seems to have been very natural for you?

It was always a natural progression. For example, during my biking career, I won lots of trophies, had my own sponsoring contracts and went on adventure trips around the world with photographers and filmmakers.

But it was in the pre-YouTube era. So there wasn’t this big social thing, like today. It was more about doing your own thing and getting paid from a couple of companies for having their bike on the cover of a magazine. That was a cool time.

But I broke my leg and had to stop sport for a year. At that point I had to make a decision about which direction I wanted to go next. So all of the things came one after the other by accident. I always chose what to do from a gut feeling.

I dived into the biking world for almost 15 years and it was a really intense time. I met a lot of crazy, cool people. But then I started a couple of internships and went to a big advertising agency in Hamburg.

After that, I studied fashion design, and became a professional designer.

While studying fashion design, I started working as a freelancer for agencies doing all the graffiti prints for big catalogues.

But once I’ve seen enough of a particular scene, I just make a cut and switch to something else I prefer.

You take on lots of things and you get them done. How do you manage that?

I always stick to what I love.

For example, music has accompanied me for almost 30 years, but I do it for myself. Sometimes it’s better to keep things as hobbies, because you can explore them as you like. Whereas, if you make it your business, you have to make them pay.

That’s the secret - keeping a balance between what you love and what you have to do to make a living.

Before we go any further, we must address one question : what is a pixelstick?

The pixelstick is one of the tools you can use for lightpainting. It’s a two meter long LED strip with an Arduino behind it. You can load a graphic onto the stick and the picture just shows slowly one line after the other.

So your pixelstick is playing a single line of a picture, while you leave a threedimensional trace in the photograph.

You can tell it to repeat an image in an endless loop, or just play it once, or just make a blue light. There are lots of different patterns you can use.

So the combination of having one more-or less-static picture, plus your movement, creates interesting things inside the picture frame.

“Before I wear new shoes I always love to get a clean

[left page] Mapped, LP, Kraftwerk, 2012 Mapping projection outlines the architecture, “a blue light sword and a double flash created this shot in one go.”

[right page] Sneakers, 2014

lightpainting shot.”

THAT’S THE CORE OF MY WORK. THE CONVERSION PROCESS BETWEEN VIRTUAL AND REAL WORLD. I LOVE ERRORS!

Spiro LP 06, 2017

Using two turntables with a custom spirograph extension arm is great for creating illustrations. “If you look closely, you can see that the extension arms broke during this shot. You can find the thred nut in the center, on the ground.”

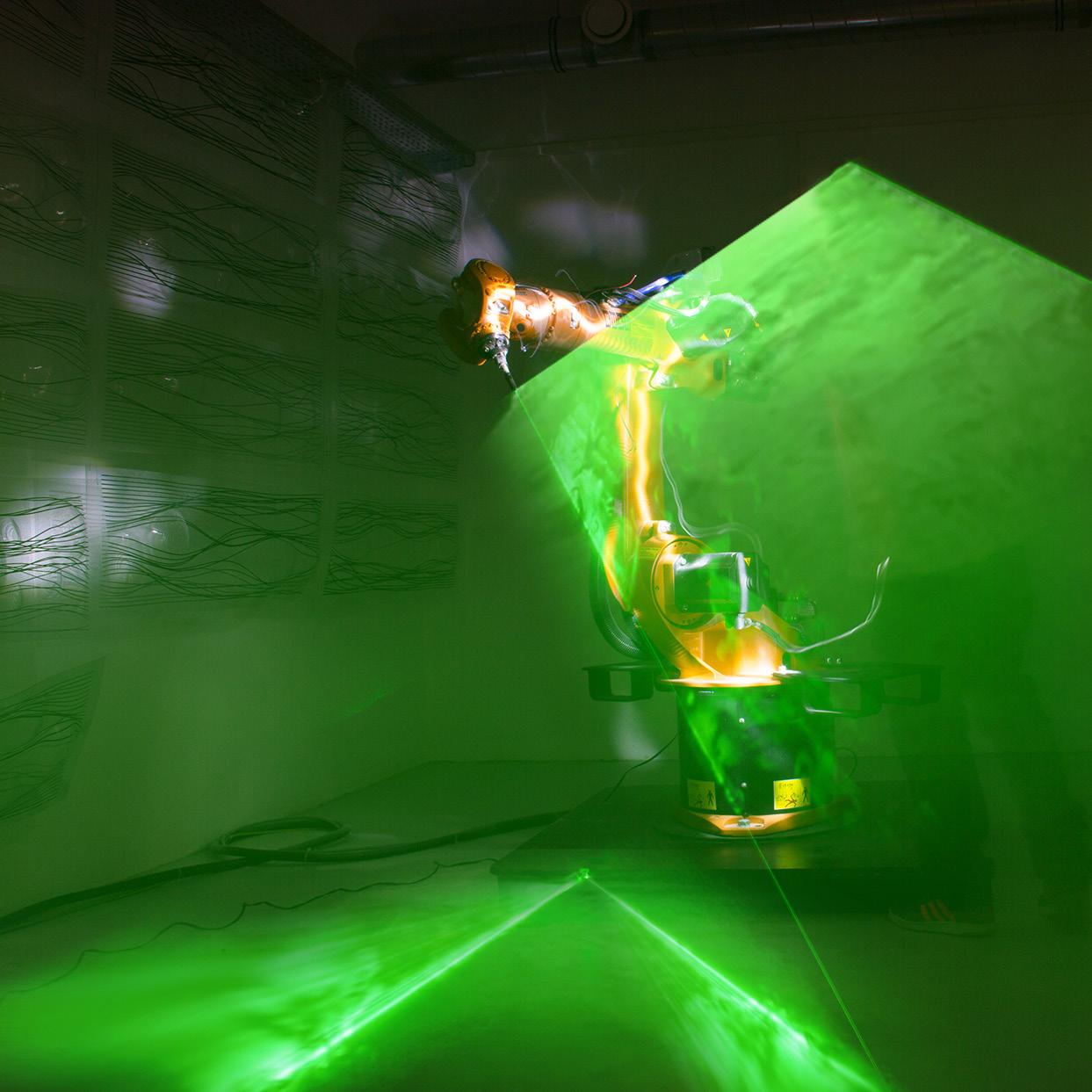

Kuka, 2016

Research at the robotic laboratory of UFG Linz University for an interactive lightpainting performance and installation. “We mounted a pixelstick on a KUKA robot and programmed a motionpath.” This was later the opener of the first „Creative robotics“ exhibition at the Ars Electronica Center.

[top]

[bottom]

[top]

[bottom]

[top] Sparkles, Kraftwerk, 2013

The leftover from NY E : a firecracker mounted on a swinging rope.

[bottom] Dragon, 2016

This is a very complex pixelstick lightpainting, shot in one take. “I started with the tail, changed the graphic behind the first pillar, repeated two half circle movements then, went back behind the last pillar to change for the head part. Simple, eh!?”

ALWAYS STICK TO WHAT I LOVE.

I

[top] MH Kienle, 2015

Editorial shooting for Mens’ Health together with ironman champion Sebastian Kienle, combining a wet floor, a pixelstick tube led lights on the rims and flashlight.

[bottom] I Will Never Grow Up, 2019

When the batteries of the pixelstick are almost dead, the LEDs create a glitch by accident. “This phrase is a metaphor for keeping myself in childish play-mode.”

I CAN DO IT ON A TRAIN RIDE, OR OUTSIDE, OR AT A SWIMMING POOL, WHEREVER I WANT.

Do you then post-process in Photoshop?

I try to always shoot in a mode called SOOC - straight out of camera. So ‘what you see is what you get’ is my mission, without too much time invested into retouching in Photoshop.

I shoot everything in high resolution, JPEG and a raw file. Maybe if I think the surrounding has too much brightness, I go into the raw file and fool around a little bit with the settings. But I’m a big fan of not faking the pictures.

That ‘realness’ comes through in the graffiti projects you’ve done Graffiti always had a big impact on me because I love calligraphy, which is a kind of a special division within graffiti. I have kept that as a hobby for three decades now.

And I keep hold of that sketching experience today. I do a lot of stuff on the iPad, in Procreate.

You can then take a picture from Procreate, load it onto the pixelstick and get out into the environment and do a lightpainting with what you have created digitally.

It’s like a meditation, once you get hooked into something like that, isn’t it?

It’s good because I can paint something without the computer too. I just take a sketchbook and a good pen.

I can do it on a train ride, or outside, or at a swimming pool, wherever I want.

So I don’t need a computer to be creative.

You did a documentary about graffiti writers in Tokyo, didn’t you?

The first time I went to Tokyo was in 2007, to make a documentary about six graffiti writers who were invited by the Goethe Institute to take part in an exchange programme.

We stayed there for two weeks. We were hosted by a guy from the government who was into art. He was running a gallery called, ‘Tokyo Wonder Site’ which had an open platform where you could apply for grants.

Two years later, I won a grant to have a one month stay in Tokyo. I had a studio and could do whatever I wanted in my time there. So I made a lot of lightpaintings. For example, we produced a huge fashion series for a European street wear magazine.

I did a lot of street art too, going out with local writers, taking pictures. I came back with 10,000 images. A huge library, and that’s just from one trip!

It must be quite a job just managing your library these days?

Let’s just say I will have plenty to keep me busy during my retirement!

But the main mission, after all these years, is to find a publisher for a book. My experience, which takes a very meandering course through the creative fields, has not been seen by too many other people.

It could be interesting for others, it could trigger input for the new generation on how to find their own path in the jungle of creativity.

In that jungle, where does a job like your lightpainting project for Porsche sit?

Actually, I’ve worked with Porsche twice. Once for the lightpainting. I would love to have had more time for that, but when you are just one wheel in the entire production process, you don’t get that kind of freedom. You’re hired to do your painting.

But if you have the freedom to present the idea to a client, and the client loves what you do, that’s a big advantage. That’s how it was at Porsche.

Can you refine and explore the possibilities of that final, performance stage of your work?

The more often you have the chance to do something, the better you can make it. You add polish.

That’s the advantage in doing a project a couple of times. But in lightpainting, the project will never be the same twice. Even if you only move ten centimetres differently the second time, the result will look completely different.

Depending on what kind of idea you have, is it really reproducible? Is it a unique piece? These are the things that come to my mind when we talk about repetition. For example, last autumn, I worked on an audio-visual piece together with a break dancer. I made a mapping projection and he danced alongside the visual content.

Now that we have made the trailer from that first production, we are able to present it at other festivals, but each time you present it you think, ‘Yeah, I

can tweak it a little bit here and make it better with that idea…’

Each time you reproduce something, the experience from the previous project will push you to new heights.

So a huge project like Schloss Charlottenburg would be very sensitive to small changes in the setup?

That was an insane project to work on. Back in 2012, we were involved in the brand new field of huge scale, surface mapping projection. We went out each night to a different building, and SchlossCharlottenburg was one of them.

Where other companies need months for pre-production, we just dived into it in one night and did one theme per building. We discussed with the client upfront, and then it just happened.

Working at that scale, you have to be clear with the vision you have in mind. You cannot lose focus on the basic idea behind a project.

The only way you could perfectly repeat a lightpainting is with a robot, maybe?

Working with the robot is always exciting. It’s a bit like being in the Tron world, or Terminator… It’s great to have access to something like that.

The university in Linz has a huge robotic laboratory. And I’m a good friend with the professor there. He lets me in from time to time, so I can fool around with the machine and try out some ideas.

In fact, I have a new mission in mind for the robot this year. But there’s

BACK THEN, I WAS USING TWO VHS RECORDERS TO PLAY VISUALS FOR THE CROWD AT TECHNO PARTIES.

[left page, top] Stay Home, 2020

“A screenshot using my penplotter in combination with virtual ink realtime software.” The errors where the pen didn’t touch the glass, in combination with the almost empty battery sign, make this shot unique.

[left page, bottom] MH Lightpainting Ironman Kienle, 2015

The challenge was to create a swimming picture in a dry studio. “The triathlete was lying on a black box while I was shaking a fiberglass brush around him, before adding a blue Led light to create some water-like lightstrokes. At the end I used a flash to freeze him crispy-sharp within the picture.”

[right page, top] Mannequin, 2022

“Two shots with my beloved mannequin model and a white fiberglass brush.”

[right page, bottom] Jelly Blade, 2018

A rare Photoshop re-edit. “Here I had a session with a strobing acrylic blade and when I saw all the single parts, I gave the jelly a go, mixing four pictures into one.”

[top] Cyberpunk Portrait, 2019

“The model was lying on a mirrorfoil on the ground when I lit her with a UV torch. Then she moved out of the frame and I used a holographic tube on a torch to create a circle. Leaving enough black inside the composition is highly recommended.”

[middle] AIT Chris Noelle, 2018

Chris Noelle at the solo-exhibition space Entschleunigung at AIT Vienna. “Combining spirography and lightpainting to create a moment of deceleration.”

[bottom] Kyo, 2019

“When I didn’t mount my tripodclamp properly, this triple exposure came out as the camera lens slowly turned downwards.”

a point at which you need a guy doing the programming of the robot’s movement. You need the technical gear, you need the camera, you need the lighting idea.

All these elements need to come together. So it’s not just myself, I need a couple of people around me to get everything done. That’s a bigger challenge, but it makes it reproducible.

Any other plans for the coming year?

I have this project called ‘The holo-painter.’ That’s coming up next. It combines projection mapping in real environments with real-time lightpainting.

You just have to imagine a huge screen that you can roll around, and on that screen is a CT scan animation. A 3D model gets scanned by one white line. And by the movement of that screen, I can create a floating threedimensional object in the environment.

Sounds incredible, will you tour with it?

It’s happening in Linz first, but it’s portable.

I’ve seen a couple of similar hologram techniques used in the events industry. But none of them used it in the way I would like to. Real-time lightpainting allows me to create an animation of what I do. I can record as the light trace builds up and builds down again. That gives you a video lightpainting.

The hardware is fast enough now that it’s a really smooth experience. It’s interesting because you can, for example, produce Tron-style effects in real-time.

That’s the challenge which I always look for - finding something that I haven’t seen before.

PREVIOUS PUBLICATIONS 01 CHRISTOPH NIEMANN Illustration Design 2009 02 MICHEL MALLARD Creative Direction 2009 03 FUN FACTORY Product Design 2009 04 ANDREAS UEBELE Signage Design 2010 05 HARRI PECCINOTTI Photography 2010 06 KUSTAA SAKSI Illustration Design 2010 07 5.5 DESIGNERS Product Design 2011 08 NIKLAUS TROXLER Graphic Design 2011 09 JOACHIM SAUTER Media Design 2011 10 MICHAEL JOHNSON Graphic Design 2011 11 ELVIS POMPILIO Fashion Design 2011 12 STEFAN DIEZ Industrial Design 2012 13 CHRISTIAN SCHNEIDER Sound Design 2012 14 MARIO LOMBARDO Editorial Design 2012 15 SAM HECHT Industrial Design 2012 16 SONJA STUMMERER & MARTIN HABLESREITER Food Design 2012 17 LERNERT & SANDER Art & Design 2013 18 MURAT GÜNAK Automotive Design 2013 19 NICOLAS BOURQUIN Editorial Design 2013 20 SISSEL TOLAAS Scent Design 2013 21 CHRISTOPHE PILLET Product Design 2013 22 MIRKO BORSCHE Editorial Design 2014 23 PAUL PRIESTMAN Transportation Design 2014 24 BRUCE DUCKWORTH Packaging Design 2014 25 ERIK SPIEKERMANN Graphic Design 2014 26 KLAUS-PETER SIEMSSEN Light Design 2014 27 EDUARDO AIRES Corporate Design 2015 28 PHILIPPE APELOIG Graphic Design 2015 29 ALEXANDRA MURRAY-LESLIE High Techne Fashion Design 2015 30 PLEIX Video & Installation Design 2016 31 LA FILLE D’O Fashion Design 2016 32 RUEDI BAUR Graphic Design 2016 33 ROMAIN URHAUSEN Product Design 2016 34 MR BINGO Illustration Design 2016 35 KIKI VAN EIJK Product Design 2016 36 JEAN-PAUL LESPAGNARD Fashion Design 2017 37 PE’L SCHLECHTER Graphic Design 2017 38 TIM JOHN & MARTIN SCHMITZ Scenography Design 2017 39 BROSMIND Illustration Design 2017 40 ARMANDO MILANI Graphic Design 2017 41 LAURA STRAßER Product Design 2017 42 PHOENIX DESIGN Industrial Design 2018 43 UWE R. BRÜCKNER Scenography Design 2018 44 BROUSSE & RUDDIGKEIT Design Code 2018 45 ISABELLE CHAPUIS Photography Design 2018 46 PATRICIA URQUIOLA Product Design 2018 47 SARAH-GRACE MANKARIOUS Art Direction 2018 48 STUDIO FEIXEN Visual Concepts 2019 49 FRANK RAUSCH Interface Design 2019 50 DENNIS LÜCK Designing Creativity 2019 51 IAN ANDERSON Graphic Design 2019 52 FOLCH STUDIO Strategic Narrative Design 2019 53 MARC TAMSCHICK Spatial Media Design 2020 54 TYPEJOCKEYS Type Design 2020 55 MOTH Animation Design 2021 56 JONAS LINDSTRÖM Photography 2021 57 VERONICA FUERTE Graphic Design 2021 58 CHRISTOPHE DE LA FONTAINE Product Design 2021 59 DAVID KAMP Sound Design 2021 60 THOMAS KURPPA Brand Design 2021 61 NEW TENDENCY Product Design 2022 62 MARTHA VON MAYDELL Illustration Design 2022 63 STUDIO KLARENBEEK & DROS Design Research 2022 64 JOUPIN GHAMSARI Photography Design 2022 65 LOTTERMANN AND FUENTES Photography Design 2022 66 SUPER TERRAIN Graphic Design 2022 67 EIKE KÖNIG Art Design 2023

Design Friends would like to thank all their members and partners for their support.

Support Design Friends, become a member. More information on www.designfriends.lu

COLOPHON

PUBLISHER Design Friends

COORDINATION Heike Fries

LAYOUT Isabelle Mattern

INTERVIEW Mark Penfold

PRINT Imprimerie Schlimé

PRINT RUN 250 (Limited edition)

ISBN 978-99987-939-4-1

PRICE 5 €

DESIGN FRIENDS

Association sans but lucratif (Luxembourg)

BOARDMEMBERS

Anabel Witry (President)

Guido Kröger (Treasurer)

Heike Fries (Secretary)

Claudia Eustergerling, Reza Kianpour, Dana Popescu, Hyder Razvi (Members)

COUNSELORS

Charline Guille-Burger, Silvano Vidale

WWW.DESIGNFRIENDS.LU

WWW.METOFA.COM

Design Friends is financially supported by

This catalogue is published for the lecture of Christopher Noelle "Surrounded by darkness - on the cutting edge of experimental cross-medial Art" at Mudam Luxembourg on 29th of March, 2023 organised by Design Friends

In collaboration with

This event is supported by Partners Service Partners

WWW.DESIGNFRIENDS.LU

[left page] Streettypo 002, Tokyo, 2009

Lost on a playground in the concrete jungle of Tokyo at nighttime.

[right page] Vasarely RMX, 2010

A polyurethane sculpture created from the cutouts of a Vasarely stencil, placed on mirrorfoil and lightened with a LED ballpen.

[left page] Streettypo 002, Tokyo, 2009

Lost on a playground in the concrete jungle of Tokyo at nighttime.

[right page] Vasarely RMX, 2010

A polyurethane sculpture created from the cutouts of a Vasarely stencil, placed on mirrorfoil and lightened with a LED ballpen.

[top]

[bottom]

[top]

[bottom]