Xanti Schawinsky und die Fotografie

Xanti Schawinsky and the Photography

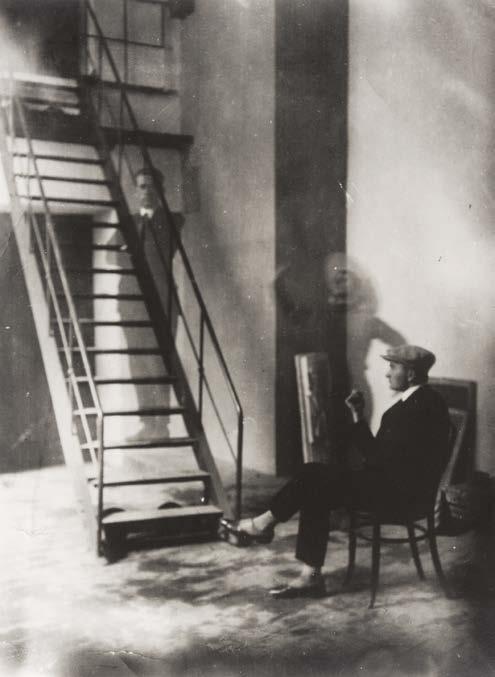

His close contact with László Moholy-Nagy, T. Lux Feininger (1910–2011), Herbert Bayer and Walter Peterhans (1897–1960) had already familiarised Schawinsky with photography during his period at the Bauhaus in Dessau. The fact that he was interested in the experimental aspect of photography at this point is demonstrated by an early photo of 1925 that he later presented under the name Treppenspuk (Haunted stairway): he used a double exposure to create the image, which shows himself and Marcel Breuer as well as the outline of a woman with a hat. (fig. 63)

In 1925, Moholy-Nagy’s Malerei, Fotografie und Film (trans. Painting, Photography, Film) was published as the eighth volume in the series of Bauhaus Bücher (Bauhaus books): it presents all the major possibilities and areas of work for artistic photography and uses examples to discuss them in depth. Moholy-Nagy describes photography as the medium of a new vision and – based on his interest in experimental photographic techniques like photomontage, collage and the photogram – he goes so far as to speak of new possibilities for painterly qualities which first emerged through the photographic medium.1 Peterhans, on the other hand, emphasised the possibilities of photographic precision in the process of communication and preserving the moment.2

Schawinsky was familiar with the spectrum of attitudes lying between these teachers and between the positions represented by the photographers shown at the 1929 exhibition at the exhibition building next to the Adolf-Mittag-See. These included figures like Eugène Atget, August Sander, Hugo Erfurth or Wanda von Debschitz-Kunowski and Eli Lotar or Umbo as well as Karl Blossfeldt, Albert Renger-Patzsch, André Kertész or Man Ray and Moholy-Nagy – to name just a few of the nearly 100 photographers in the exhibition. (fig. 47–52) This breadth is subsequently also described in almost apologetic terms by the curator Kurt Wilhelm Kästner in the exhibition catalogue: ‘But what presents itself here is not yet a unified image by any means; instead, we need to pay attention to currents running alongside one another.’3 As Schawinsky became personally more and more active as a photographer in Magdeburg, his interest encompassed this entire spectrum and corresponded entirely to Moholy-Nagy’s view that ‘those unfamiliar with photography will be the illiterate of the future’.4 Thus, to date, it has been possible to identify over 300 photographs as Schawinsky’s work for the municipal building authority. 5 Not all of these photos are of equal artistic value, but throughout his life Schawinsky’s photography accompanied the different phases of his oeuvre with greater or lesser intensity. At times it is an exclusively artistic medium of expression, as in the 1940s and 1960s, 6 and at other times it is once again committed to largely documentary photography – whether as a precious and indispensable memento of the Bauhaus years or in the form of documentary work for the town of Magdeburg’s building authority. However, Schawinsky always simultaneously utilised his photographic works as a storehouse of material for his countless collages and illustrative panels.

As a student of Klee, Kandinsky and Moholy-Nagy, Schawinsky had been familiarised not just with their specific and disciplined method, but primarily with an attitude towards the complex relationship between art and technology, which often incorporated far-flung fields of activity. This approach always corresponded to what Schawinsky felt ‘as a Bauhaus artist’.7 For Schawinsky – and entirely in the sense of the Bauhaus – colours and forms, motion and light, tones and words, pantomime and music, illustration and improvisation belonged to the vocabulary of his complex mode of expression. At this point – and also later, for example, as a teacher at Black Mountain College – Schawinsky already understood how to achieve a ‘symphonic effect’ employing all available skills and means.8

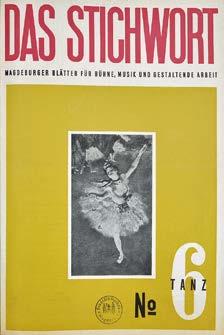

A large part of the photographs Schawinsky created in Magdeburg between 1929 and 1931 were produced specifically for the periodical Das Stichwort – Magdeburger Blät-

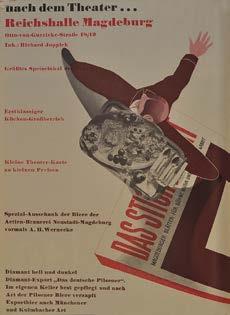

64 Das Stichwort. Magdeburger Blätter für Bühne, Musik und gestaltende Arbeit, Heft 6 (Tanz), 1930

64 Das Stichwort: Magdeburger Blätter für Bühne, Musik und gestaltende Arbeit. Issue 6 (dance), 1930

1 László Moholy-Nagy, Malerei, Fotografie und Film, Bauhausbücher, vol. 8 (Munich: Albert Langen Verlag, 1927), p. 106.

2 For Peterhans, see ‘Lux Feiniger: Aus meiner Frühzeit’, in: Film und Foto der 20er Jahre (see n. 18, p. 56), p. 80.

3 Kurt Wilhelm Kästner, in: Film und Foto der 20er Jahre (see n. 2), p. 10.

4 László Moholy-Nagy, ‘Diskussion über Ernst Kallai’s Artikel “Malerei und Fotografie”’, in: Internationale Revue i 10 6 (1927), p. 233 f., here p. 233.

5 Holdings of the HBA, Stadtarchiv Magdeburg. The identification process is laborious and possible only through comparison with the magazine Stichwort and the photos in the estate as well as several publications from the period up to 1986.

6 See Eckhard Neumann, ed. Xanti Schawinsky: Foto, exhibition catalogue (Bern 1989).

7 See Xanti Schawinsky, ‘metamorphose bauhaus’, in: Bauhaus und Bauhäusler: Erinnerungen und Bekenntnisse, ed. Eckhard Neumann (Cologne 1985), pp. 213–23.

8 Vittorio Fagone, in: Xanti Schawinsky (see n. 4, p. 52), p. 63.

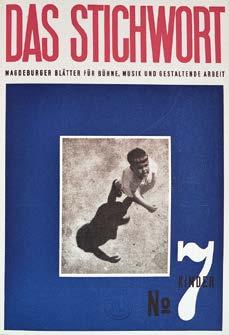

65 Das Stichwort. Magdeburger Blätter für Bühne, Musik und gestaltende Arbeit, Heft 7 (Kinder), 1930

65 Das Stichwort: Magdeburger Blätter für Bühne, Musik und gestaltende Arbeit. Issue 7 (children), 1930

1 Moholy-Nagy, László: Malerei, Fotografie und Film, Bauhausbücher 8, München Albert Langen Verlag, 1927, S. 106.

2 Zu Walter Peterhans vgl. Lux Feininger: »Aus meiner Frühzeit«, in: Film und Foto der 20er Jahre (wie Anm. 18, S. 57), S. 80.

3 Kurt Wilhelm Kästner, in: Film und Foto der 20er Jahre (wie Anm. 2), S. 10.

4 Moholy-Nagy, László: Diskussion über Ernst Kallai’s Artikel »Malerei und Fotografie«, in: Internationale Revue i 10 6 (1927), S. 233 f., hier S. 233.

5 Bestand des HBA, Stadtarchiv Magdeburg. Die Zuordnung ist mühsam und nur im Vergleich mit der Zeitschrift »Stichwort« und den Fotografien im Nachlass sowie einigen Publikationen aus der Zeit bis 1986 möglich. Vgl. Anm. 16. Ein gebundenes Exemplar der Zeitschrift »Stichwort« in allen 18 Ausgaben in der Stadtbibliothek Magdeburg. Einige Nummern in der Sammlung des Museum of Modern Art in New York.

6 Vgl. Xanti Schawinsky. Foto, Ausstellungskatalog, hrsg. v. Eckhard Neumann, Bern 1989.

7 Vgl. Schawinsky, Xanti: »metamorphose bauhaus«, in: Eckhard Neumann (Hrsg.): Bauhaus und Bauhäusler. Erinnerungen und Bekenntnisse, Köln 1985, S. 213–223.

8 Vittorio Fagone, in: Xanti Schawinsky Ausstellungskatalog 1986 (wie Anm. 4, S. 53), S. 63.

Der enge Kontakt zu László Moholy-Nagy, T. Lux Feininger (1910–2011), Herbert Bayer und Walter Peterhans (1897–1960) hatte Schawinsky schon während seiner Zeit am Bauhaus in Dessau mit der Fotografie vertraut gemacht. Dass ihn am Foto in dieser Zeit das Experiment interessierte, belegt eine frühe Fotografie von 1925, die er später unter der Bezeichnung »Treppenspuk« führte und die in Doppelbelichtung ausgeführt ihn selbst und Marcel Breuer sowie den Umriss einer Dame mit Hut zeigt. (Abb. 63)

1925 erschien als achter Band der Bauhausbücher Moholy-Nagys »Malerei, Fotografie und Film«, der alle wichtigen Möglichkeiten und Arbeitsgebiete künstlerischer Fotografie vorstellt und eingehend in Beispielen erläutert. Moholy-Nagy beschreibt die Fotografie als Medium einer neuen Sichtweise und geht, ausgehend von seinem Interesse für experimentelle fotografische Techniken wie Fotomontage, Collage und Fotogramm, so weit, von neuen Möglichkeiten malerischer Qualitäten zu sprechen, die erst durch das Medium der Fotografie entstehen würden.1 Walter Peterhans hingegen betont die präzisen Möglichkeiten der Fotografie im Prozess der Kommunikation und des Bewahrenden des Augenblicks.2

Schawinsky kannte die Bandbreite der Anschauungen, die zwischen den Lehrern lag und die in der 1929 gezeigten Ausstellung am Adolf-Mittag-See zwischen fotografischen Positionen eines Eugène Atget, August Sander, Hugo Erfurth oder einer Wanda von Debschitz-Kunowski, eines Eli Lotar oder Umbo sowie eines Karl Blossfeldt, Albert Renger-Patzsch, André Kertesz oder Man-Ray und Moholy-Nagy zu sehen waren – um nur einige der fast 100 Positionen der Ausstellung zu erwähnen. (Abb. 47–52) Im Katalog zur Ausstellung wird diese Bandbreite dann auch vom Kurator Kurt Wilhelm Kästner fast entschuldigend beschrieben: »Es ist aber überhaupt noch kein einheitliches Bild, das sich hier bietet, es sind vielmehr nebeneinander herlaufende Strömungen zu beachten.«3 Als Schawinsky in Magdeburg zunehmend selbst als Fotograf tätig wurde, umfasste sein Interesse dieses gesamte Spektrum und entsprach ganz der Ansicht Moholy-Nagys, »dass der fotografie-unkundige der analfabet der zukunft sein wird.«4 So lassen sich aus der Tätigkeit Schawinskys für das Städtische Hochbauamt bis heute mehr als 300 Fotografien identifizieren.5 Nicht alle diese Fotos sind von gleichem künstlerischem Wert, aber zeit seines Lebens begleitete die Fotografie Schawinskys unterschiedliche Schaffensphasen mehr oder weniger intensiv. Mal ist sie ausschließlich künstlerisches Ausdrucksmedium, wie in den 1940er und 1960er Jahren,6 dann wieder eher der dokumentarischen Fotografie verpflichtet, ob als wertvolle und unverzichtbare Erinnerung an die Bauhausjahre oder in Form dokumentarischer Tätigkeit für das Hochbauamt der Stadt Magdeburg. Immer aber verwendete Schawinsky seine fotografischen Arbeiten gleichzeitig auch als Materialfundus für seine unzähligen Collagen und Schautafeln.

Als Schüler von Klee, Kandinsky und Moholy-Nagy hatte Schawinsky außer der spezifischen und disziplinierten Methode vor allem eine Haltung gegenüber der komplexen Beziehung zwischen Kunst und Technik kennengelernt, die oft weit auseinanderliegende Aktionsfelder mit einbezog. Dieses Vorgehen entsprach immer dem, wie Schawinsky sich fühlte, »als Bauhauskünstler«.7 Ganz im Sinne des Bauhauses gehörten Farben und Formen, Bewegung und Licht, Töne und Worte, Pantomime und Musik, Illustration und Improvisation für Schawinsky zum Vokabular seines komplexen Ausdrucks. Wie auch später, u. a. als Lehrer am Black Mountain College, verstand es Xanti Schawinsky hier bereits, unter dem Einsatz aller Fähigkeiten und Mittel zu einer »Symphonischen Wirkung«8 zu gelangen.

Ein Großteil der zwischen 1929 und 1931 in Magdeburg entstandenen Fotografien fertigte Xanti Schawinsky zielgerichtet für die Zeitschrift »Das Stichwort – Magdeburger Blätter für Bühne, Musik und gestaltende Arbeit« an – oder sie wurden zumindest in dieser

ter für Bühne, Musik und gestaltende Arbeit or they were at least reproduced there; others are still to be founded exclusively in the artist’s estate today.9 Beginning on 1 September 1930 this periodical designed by Schawinsky appeared every 14 days; in its final issue, released at the end of March in 1931, it finally presented a collected work filling 264 pages.10 From the very beginning, Göderitz utilised it as a platform, where he could use his own contributions to reflect on the most innovative ideas and concepts in town planning and design as well as the development of theatre and art in the town and for the town. The fact that theatre served as a point of departure and was not considered the focus of the reporting is expressed by Otto Hahn as its editor-in-chief: ‘It is only anchored there […]the new Magdeburger Blätter are to be oriented around art in general.’11 Its unifying principles were entirely in keeping with the notions of a modern life and were familiar to Schawinsky from his work at the Bauhaus. In the magazine, they can be plainly recognised in the attitude towards life linking together every area of the town’s progressive cultural life. Financed by the modern world of commerce, that is, by department-store advertising, the reporting addressed the interests of a modern, open-minded and well-educated middle class. This is reflected in the often lengthy articles devoted (in addition to theatre) primarily to stage design, music, dance, fine arts, literature and – not least – architecture and its construction. The fact that the second issue already presents the work of Klee through his 1924 watercolour Lied des Spottvogels (Song of the mocking bird) and T. Lux Feininger through a photographic study of nature is to be traced back to Schawinsky’s direct connections with both of them. Alongside this aspect, the reprinting of older and more recent literature ranging from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Nietzsche to Else Lasker-Schüler (1869–1945) was part of the magazine – as was, of course, a contribution by the museum director Walther Greischel (1889–1970). The Magdeburg theatrical designer Hugo Schmitt’s stage sets – which, depending on the production, range across every style of art from the traditional to the avant-garde and adorn almost every one of the magazine’s eighteen issues – are joined in one of the first issues by photographs of Gret Palucca’s dance performances paired with the reprint of a formative text on expressive dance (fig. 116–127).12

Göderitz repeatedly wrote contributions and used the magazine as a medium for publishing reports on his architectural aspirations and designs for public buildings like the Stadthalle. In addition to reprinted writings on architecture by Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier, innovative essays from other areas of life were also published in increasing numbers. An article on play and toys by Walter Tiemann and an essay on the topic of modern architecture for children by Göderitz himself are paired with photos and collages of images by Schawinsky about the garden school in Rothensee (Magdeburg) or the Wilhelmstadt experimental school/new school,13 which could be seen at the same time at exhibitions in the exhibition hall next to the Adolf-Mittag-See. (fig. 60) The municipal medical official Ludwig Bergmann likewise has his say. After taking the occupational illnesses of musicians and stage and theatrical artists as his point of departure, it is very likely that he also authored the contribution printed beneath it. Written for the municipal health authority, the latter article deals with modern health care and has been illustrated by Schawinsky with numerous reproductions of his photo-collages.

With their modern typography (featuring the use of Futura type), their details from photos and pictures framed in colour on the cover and their clear and simple sequencing of image and text, the magazines’ design entirely corresponds to the idea of a periodical aimed at the programmatic education of its readers, much like the Bauhaus magazine by Gropius and Moholy-Nagy in Dessau. It seems likely that Schawinsky brought this idea with him from Dessau and defined the content together with Göderitz.

66 Magdeburger Sehenswürdigkeiten, in: Das Stichwort, Heft 4, S. 73

66 ‘Magdeburg Sights’, in: Das Stichwort, issue 4, p. 73

9 See n. 5: There is a bound copy of Stichwort with all 18 of its issues in the Stadtbibliothek Magdeburg. There are a few issues in the collection of MoMA (New York).

10 Regarding this, see: letter of Göderitz to Schawinsky from 2 April 1974, Correspondence in the papers of the Schawinsky Estate, Zurich, (XST341-365).

11 Stichwort 1 (1st September issue of 1930), p. 24.

12 Stichwort 6 (2nd November issue of 1930), pp. 124–25. The text is a reprint from Anbruch The music periodical Anbruch (beg. 1929) was an Austrian journal which became important for the development of New Music. It was published from 1919 to 1937 by the Wiener Musikverlag Universal Edition (UE) in 19 volumes with 165 issues and double issues and, from 1935, by the VorwärtsVerlag.

13 Johannes Göderitz, ‘Wenn man für Kinder baut’, Stichwort 7 (1st December issue 1930), pp. 133–35.

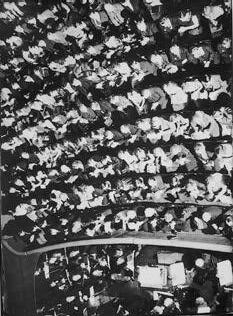

67 Applaus im Magdeburger Stadttheater, in: Das Stichwort, Heft 5, S. 105

67 ‘Applause in the Theatre Magdeburg’, in: Das Stichwort, issue 5, p. 105

abgedruckt; andere befinden sich bis heute im Nachlass.9 Ab 1. September 1930 erschien die von Schawinsky gestaltete Zeitschrift10 14-tägig und lag Ende März 1931 mit ihrem letzten Band schließlich als 264-seitiges Gesamtwerk vor. Johannes Göderitz nutzte sie von Beginn an als Podium, um in eigenen Beiträgen über die innovativsten Gedanken und Ideen der Stadtplanung und Gestaltung, der Entwicklung von Theater und Kunst in der Stadt und für die Stadt zu reflektieren. Dass dabei das Theater als Ausgangspunkt diente und nicht als Zentrum der Berichterstattung gedacht war, formulierte Otto Hahn als Schriftleiter: »Nur ihr Anker liegt dort […] die neuen Magdeburger Blätter wollen um Kunst schlechthin gelagert sein.«11 Die ganz im Sinne eines modernen Lebens verbindenden Gedanken, wie Schawinsky sie von seiner Tätigkeit am Bauhaus kannte, werden im Blatt in einem alle Bereiche des fortschrittlichen kulturellen Lebens einer Stadt verbindenden Lebensgefühl deutlich. Von der modernen Geschäftswelt bzw. Kaufhauswerbung finanziert, zielte die Berichterstattung auf die Interessen eines aufgeschlossenen modernen Bildungsbürgertums, was sich in den oft umfangreichen Beiträgen widerspiegelt, die neben dem Theater vor allem dem Bühnenbild, Musik, Tanz, Bildender Kunst und Literatur sowie nicht zuletzt auch dem Bauwesen gelten. Dass Paul Klee gleich in Heft 2 mit dem Aquarell »Lied des Spottvogels« von 1924 und T. Lux Feininger mit einer fotografischen Naturstudie vertreten sind, wird auf die direkten Kontakte Schawinskys zu beiden zurückgehen, während daneben auch der Wiederabdruck alter und neuer Literatur von Goethe und Friedrich Nietzsche bis hin zu Else Lasker-Schüler (1869–1945) ins Blatt gehörten sowie ganz selbstverständlich auch ein Beitrag des Museumsdirektors Walther Greischel (1889–1970). Neben Bühnenbildern des Magdeburger Bühnenbildners Hugo Schmitt, die je nach Aufführung alle Stile der Kunst zwischen Tradition und Avantgarde durchziehen und fast jede der 18 Ausgaben des Blattes zieren, gesellten sich in einer der ersten Ausgaben Abbildungen der Tanzauftritte Gret Paluccas mit einem Wiederabdruck eines wegweisenden Textes über den Ausdruckstanz hinzu (Abb. 116–127).12

9 Vgl. Anm. 5.

10 Hierzu Brief Göderitz an Schawinsky vom 02.04.1974, Briefwechsel im Nachlass, Xanti Schawinsky Estate, Zürich XST341–365.

11 Stichwort. Magdeburger Blätter für Bühne, Musik und gestaltende Arbeit 1 (September 1930), S. 24.

12 Stichwort 6 (November 1930), S. 124–125. Der Text ist ein Wiederabdruck aus »Anbruch«. Die Musikblätter »Anbruch« (ab 1929) sind eine österreichische Musikzeitschrift, die für die Entwicklung der Neuen Musik bedeutsam wurde. Sie erschienen 1919 bis 1937 in 19 Jahrgängen mit 165 Heften und Doppelheften bei dem Wiener Musikverlag Universal Edition (UE) und ab 1935 im Vorwärts-Verlag.

13 Göderitz, Johannes: »Wenn man für Kinder baut«, in: Stichwort 7 (Dezember 1930), S. 133–135.

Immer wieder berichtete Johannes Göderitz über seine architektonischen Anliegen und Entwürfe öffentlicher Bauten wie z. B. der Stadthalle im »Stichwort«. Außer den nachgedruckten Architekturschriften von Walter Gropius und Le Corbusier erschienen zunehmend auch innovative Aufsätze aus anderen Lebensbereichen. Einem Beitrag zu Spiel und Spielzeug von Walter Tiemann und einem Essay zum Thema Modernes Bauen für Kinder von Johannes Göderitz selbst ordneten sich Fotos und Bildcollagen Schawinskys zur Gartenschule Magdeburg Rothensee oder zur Wilhelmstädter Versuchsschule/ neue Schule Wilhelmstadt zu,13 die zeitgleich auch auf Ausstellungen in der Ausstellungshalle am Adolf-Mittag-See zu sehen waren. (Abb. 60) Ebenso kam der Stadtarzt Ludwig Bergmann zu Wort, der, ausgehend von den Berufskrankheiten der Musiker, Theater- und Bühnenkünstler, sehr wahrscheinlich auch den darunter gedruckten Beitrag zur modernen Gesundheitsvorsorge für das städtische Gesundheitsamt beisteuerte, den Schawinsky mit zahlreichen Abbildungen seiner Fotocollagen bebilderte.

Die Gestaltung der Hefte in ihrer modernen Typografie (unter Verwendung des Schriftsatzes der Futura), mit den farbig gerahmten Foto- und Bildausschnitten auf dem Cover sowie einer klar und einfach gehaltenen Folge von Bild und Text entspricht ganz der Idee eines Blattes, das, ähnlich der Bauhauszeitung von Walter Gropius und László Moholy-Nagy in Dessau, auf eine programmatische Unterrichtung des Lesers zielt. Dass Schawinsky diese Idee aus Dessau mitbrachte und gemeinsam mit Göderitz die Inhalte festlegte, bleibt zu vermuten. Sicher ist hingegen, dass alle abgebildeten Fotografien, mit Ausnahme einzelner eigens gekennzeichneter Aufnahmen, sowie die Gestaltung der Werbeannoncen einzelner Firmen auf Schawinskys Autorschaft zurückgehen. Besonders bemerkenswert, gerade im Hinblick auf Schawinskys spätere Karriere als Werbegrafiker,

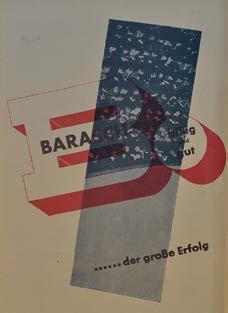

On the other hand, it is certain that all of the reproduced photographs – with the exception of isolated images that are individually identified – as well as the design of the advertisements of individual companies were created by Schawinsky. The advertisements for the Magdeburg branch of the Barasch department store and the theatre pub (fig. 69, 68),14 in which Schawinsky employs every trick known to the expert in advertising collage, are especially remarkable – particularly when considered in the context of Schawinsky’s later career as a commercial graphic designer.

At that time, Schawinsky was already dominated by a passion for montage, for the disparate and playful, as he set out to test new techniques on the basis of his knowledge about that relationship between volume and surface to space which plays a role in the theatre. He took his forms and inspiration from the street, the fair, the circus – and theatre, in particular, possessed many motifs which he could utilise. There is the clown who stands on his hands and, in his white robe, becomes a form that functions like a cut-paper silhouette; there is the doll whose spherical, round cheeks are juxtaposed with the round globe and which Schawinsky has supplemented through an additional round detail of a face as a montage. (fig. 97, 89) A large silver patene (fig. 128) in front of hand-embroidered text is just as worthy of depiction as an arrangement of little test tubes or the pattern of holes in a tablecloth. Placing a glass light bulb within the image was presumably almost a part of the standard etiquette for photos by a photographer friend of Moholy-Nagy (fig. 75). Whether in the playful handling of the material – as in the ‘shoe carousel’ in front of the mirror (fig. 78) – or a more or less photographically precise observation, as in the worm’s-eye view of the cars from the carousel at the fair: it is the simplest of subjects and everyday events that become precise images through the selective gaze of the camera. By contrast, other images – like the scenes from theatre and ballet, with their unpretentious informative content – seem more like forerunners of modern press photography.

An enthusiasm for montage, for the disparate, for playfullness was something integral to Schawinsky’s work even at that time, when he was trying out new techniques founded upon his knowledge of the relationship of the body and planes, a relationship which played an important role in theatre.15

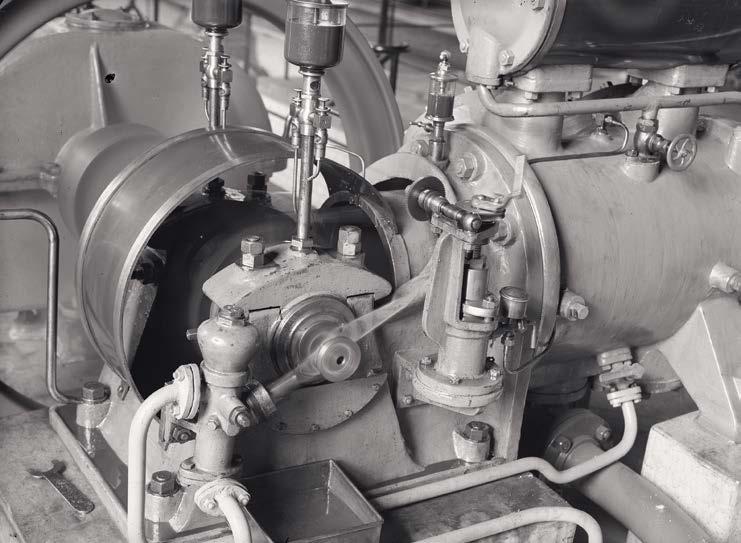

His familiarity with Dadaistic collages as well as the photograms of Man Ray, Christian Schad, Kurt Schwitters and, of course, his friend Moholy-Nagy also provided Schawinsky with a foundation for developing his bold exhibition designs. Growing out of his extensive collection of photographic material, these designs are particularly interesting because they link together elements of painting and graphic art in a completely unconventional manner. (fig. 53, 57, 58) As a designer he united the aesthetic demands of the Bauhaus with the requirements and mechanisms of product advertisement in his designs for extremely diverse shows in Magdeburg’s exhibition halls next to the AdolfMittag-See. In his article on ‘Magdeburg als Ausstellungsstadt’ (Magdeburg as an exhibition town), municipal official Georg Bucksch proudly talks about the exhibition work of 1929 and 1930: ‘The results of this series give reason to expect that the coming exhibitions – with the one on “Technical Structures” coming up next – will be expertly prepared. The municipal corporations can trust that the exhibition office will continue to work to the advantage of our local economy without engaging in excessive spending.’16

Along with the exhibitions Technical Structures: Light in the Service of Advertising, Rite and Form 17 and Woman, 18 all held in 1930, it was particularly the exhibitions Flat for Poverty-line Income,19 held in October of the same year, as well as The Child in Magdeburg’s Schools in Neuhaldensleben and Magdeburg’s contribution to the German Hygiene Exhibition (Deutsche Hygiene-Ausstellung) in Dresden from 17 May to 12 October 1930 which seem likely to have consumed most of Schawinsky’s attention. The exhibi-

68 Anzeige für ein Café, in: Das Stichwort, Heft 10, 2. Umschlagseite

68 Advertisement for a café, in: Das Stichwort, issue 10 (inside front cover)

14 Stichwort 9 (1st January issue 1931) and 10 (2nd January issue 1931), back cover of each.

15 Andreas Krase’s expressed opinion that Schawinsky’s photographs are of no particular importance is based on his being unaware of many photos that have only since become known. See Andreas Krase, “Xanti Schawinsky. Magdeburg 1929–31/Fotografien”, in: Magdeburg – Die Stadt des Neuen Bauwillens. Zur Siedlungsentwicklung der Weimarer Republik, Magdeburger Hefte des Stadtplanungsamtes 39, 1, 1995, pp. 8–17.

16 Magdeburger Amtsblatt (1930), p. 12.

17 Magdeburger Amtsblatt (1930), p. 140.

18 Magdeburger Amtsblatt (1930), p. 328.

19 Magdeburger Amtsblatt (1930), pp. 64 ff., pp. 328, 356, 664, 861.

69 Anzeige für das Kaufhaus Barasch, in: Das Stichwort, Heft 9, Rückseite

69 Advertisement for the Barasch department store in: Das Stichwort, issue 9 (back page)

sind die Anzeigen für die Magdeburger Filiale des Kaufhauses Barasch und das Theaterlokal,14 (Abb. 69, 68) in denen Schawinsky alle Tricks einer gekonnten Werbecollage zum Einsatz bringt.

Die Lust an der Montage, dem Disparaten, dem Spielerischen beherrschte Schawinsky schon damals, als er, ausgehend von seinen Kenntnissen des Verhältnisses von Körper und Fläche zum Raum, wie es im Theater eine Rolle spielte, neue Techniken erprobte. Von der Straße, vom Jahrmarkt, aus dem Zirkus nahm er seine Formen und Anregungen, und gerade das Theater hat viele Motive, die sich verwenden ließen. Da ist der Clown, der auf den Händen steht und in seinem weißen Gewand zur Form wird, die wie ein Papierschnitt fungiert, da ist die Puppe mit ihren runden Wangen, die kugelrund dem runden Globus gegenübersteht und die er durch einen weiteren runden Gesichtsausschnitt als Montage ergänzt. (Abb. 97, 89) Eine große silberne Patene (Abb. 128) vor handwerklich gesticktem Text wird ebenso bildwürdig wie eine Anordnung kleiner Reagenzgläser oder das Lochmuster einer Tischdecke. Eine gläserne Glühbirne ins Bild zu setzen gehörte vermutlich schon fast zum guten Kanon der Fotografie eines Fotografenfreundes von Moholy-Nagy. (Abb. 75) Ob spielerischer Umgang mit dem Material, wie im »Schuhkarussell« vor dem Spiegel (Abb. 78), oder eher fotografisch präzise Beobachtung, wie dem extremen Unterblick auf die Gondeln des Karussells auf dem Jahrmarkt: Es sind einfachste Gegenstände und alltägliche Ereignisse, die durch den selektierenden Blick der Kamera zu präzisen Bildern werden. Andere hingegen, wie die Theater- und Ballettszenen, wirken in ihrem unprätentiösen Informationsgehalt doch eher wie die Vorreiter einer modernen Pressefotografie.

Schawinskys Begabung, die kreative, ungezwungen spielerische Leichtigkeit seiner Malerei und Bühnenerfahrung mit dem Gespür für fotografische Vorgänge und Bildkompositionen zu verbinden, macht die fotografische Qualität seiner erhaltenen Bildserien aus.15

14 Stichwort 9 (Januar 1 1931), Stichwort 10 (Januar 2 1931), jeweils Rückseite.

15 Die Meinung Andreas Krases, Schawinskys Fotografien seien ohne besondere Bedeutung, beruhte auf Unkenntnis vieler inzwischen bekannter Fotografien. Siehe Andreas Krase: »Xanti Schawinsky. Magdeburg 1929–31/ Fotografien«, in: Magdeburg – Die Stadt des Neuen Bauwillens. Zur Siedlungsentwicklung der Weimarer Republik, Magdeburger Hefte des Stadtplanungsamtes 39, 1, 1995, S. 8–17.

16 Magdeburger Amtsblatt 1930, S. 12.

17 Magdeburger Amtsblatt 1930, S. 140.

18 Magdeburger Amtsblatt 1930, S. 328.

19 Magdeburger Amtsblatt 1930, S. 64 ff., S. 328, 356, 664, 861.

Aufgrund seiner Kenntnis der dadaistischen Collagen, der Fotogramme Man Rays, Christian Schads, Kurt Schwitters’ und natürlich seines Freundes Moholy-Nagy entwickelte Schawinsky auch seine kühnen Ausstellungsgestaltungen, die vor allem deshalb von Interesse sind, weil er in ihnen, ausgehend von umfangreichem fotografischen Material, Elemente der Malerei und Grafik in ganz unkonventioneller Weise miteinander verband. (Abb. 53, 57, 58) Gestaltend vereinte er die ästhetischen Forderungen des Bauhauses mit den Bedingungen und Mechanismen der Produktwerbung in seinen Gestaltungen für ganz verschiedene Schauen in den Magdeburger Ausstellungshallen am Adolf-MittagSee. Stolz lässt sich in einem Artikel über »Magdeburg als Ausstellungsstadt« der Magistratsrat Georg Bucksch über das Ausstellungswesen der Jahre 1929 und 1930 aus: »Das Ergebnis dieser Reihe lässt erwarten, dass die kommenden Ausstellungen, von denen zunächst die über ›Bauten der Technik‹ bevorsteht, geschickt vorbereitet werden. Die städtischen Körperschaften dürfen darauf vertrauen, daß das Ausstellungsamt ohne übermäßige Aufwendungen zum Nutzen der heimischen Wirtschaft weiterarbeiten wird.«16

Neben den Ausstellungen »Bauten der Technik. Das Licht im Dienste der Werbung«, »Kult und Form«17 und »Die Frau«18 , alle im Jahre 1930, sind es insbesondere die im Oktober desselben Jahres stattfindenden Ausstellungen »Die Wohnung für das Existenzminimum«19 und »Das Kind in Magdeburger Schulen« in Neuhaldensleben sowie der Beitrag Magdeburgs für die Internationale Hygiene-Ausstellung in Dresden vom 17. Mai bis 12. Oktober 1930, die Schawinskys Aufmerksamkeit am meisten gebunden haben werden. Die Ausstellungen in verschiedener Verantwortlichkeit wurden alle gestalterisch vom Ausstellungsamt betreut, und so unterschiedlich sie in ihrer thematischen Ausrich-

tion office supervised the design of all these exhibitions, which were organised by various groups: as diverse as they may have been in terms of their thematic orientation, the exhibitions were nonetheless always defined by a very progressive intention and design. The contribution to the hygiene exhibition in Dresden was entitled ‘Cooperation of the office of community health with other municipal administration offices: personnel examinations, transporting the sick, infant-care instruction, district welfare services, youth welfare services, marriage counselling’.20 It finally offered an exemplary presentation encompassing the whole spectrum of modern municipal administration: everything from its societal advantages and opportunities for advancement all the way to progressive educational reform was summed up in clear and vivid images and presented through large illustrative panels as well as models.

Besides his work as an exhibition designer and for the building authority as well as numerous commissions for private clients in Magdeburg, Schawinsky also repeatedly worked for Gropius until the end of 1931.21 In March of 1931, he produced the illustrative panels for Gropius’s ‘Project for a high-rise block of flats with common rooms’ for the German Building Exhibition. A surprised Gropius personally sent him the copy of a prize awarded to both of them together for this project. (fig. 70, 71) Not only does the extensive correspondence between Gropius and Schawinsky clearly show how close they were, it also mentions of this or that project, such as the production of an advertising brochure for the prefabricated ‘Kupferhäuser’ homes of the Hirsch-Adler company. Gropius won a prize at the 1931 World’s Fair in Paris for the revision he made to the homes’ design. Precisely this brochure was designed by Schawinsky at that time and printed by Wohlfeil in Magdeburg.22 Gropius also depended on Schawinsky’s assistance for realising the illustrative panels on the occasion of the international competition for the Palace of the Soviets in Moscow, to which Le Corbusier and Erich Mendelsohn had also been invited, in addition to Gropius.23

The most striking aspect of all the illustrative panels designed by Schawinsky is the fact that he cut individual figures out of his own photographs and combined these into new scenic depictions. Moholy-Nagy called this method of compilation ‘photo-sculpture’ (Fotoplastik),24 and Schawinsky would perfect it only a few years later in the sequences of images in his spectodramas at Black Mountain College. (fig. 36–39) He always maintains the unconventional scale and formal diversity in the typographies and visual material he utilises as well as in his unbelievably creative handling of existing materials. The extreme enlargements of photographs are especially remarkable, and Schawinsky was already using them in 1929 for the trade-fair stand of Junkers & Co. at the Berlin exhibition Gas and Water. The fact that Schawinsky was a master of juxtaposing ideas may also have served him well in this context. In particular the use of the collage principle, experiences in theatrical design and knowledge of possibilities enabling the use of images at greater than life-size were probably founded on relevant personal contacts or, alternatively, directly viewing the pavilion designed by Konstantin Melnikov for the 1925 Paris Expo and the high standard it set for formal dynamism and the innovative use of materials.25 However, it may also have been his familiarity with the pioneering trade fair ‘Pressa’, which was held in Cologne in 1928: among the 1500 exhibitors from 43 countries, it was particularly the Soviet pavilion featuring floor-to-ceiling photo-collages by El Lissitzky that drew intense attention.26 In any case, the correspondence with Gropius allows us to conclude that he personally held Schawinsky’s technical ability in this area, his skill as a negotiator, his connections and his creativity in high esteem. This finally predestined Schawinsky – in 1939, when he was already working from New York –to join Herbert Bayer in decorating the ‘Pennsylvania Pavilion’ built by Gropius and Marcel

70 Walter Gropius, Projekt eines Wohnhochhauses, Deutsche Bauhausausstellung Berlin, Grafische Gestaltung Schawinsky, 1930/31

70 Walter Gropius, project of a high-rise apartment building, German Bauhaus Exhibition Berlin, graphic design Schawinsky, 1930/31

20 Stichwort 12 (2nd February issue 1931), p. 206.

21 See the letters from his estate papers, 1930 to 1934.

22 On the houses, see deutsche bauzeitung (2006), cited from: https://www.db-bauzeitung. de/allgemein/in-die-jahre-gekommen-25 [accessed 23 January 2018].

23 Gropius to Schawinsky on 28 November 1931: ‘dear Xandi, […] if it is in any way possible, could you please be part of the final sprint and tell your assistant that he should come here immediately, quick as a telegram. we will reach an agreement about the payment along the lines already discussed with you. the Soviet palace is an enlarged rotunda, keep that in mind. your Pius’, papers of the Schawinsky Estate, letters of Walter Gropius. Regarding the competition itself, see Selim O. Chan-Magomedov and Christian Schädlich (ed.), Avantgarde II 1924–37: Sowjetische Architektur (Stuttgart: Verlag Gerd Hatje, 1993), pp. 113 ff., 214 ff.

24 László Moholy-Nagy, Malerei, Fotografie, Film (see n. 1), p. 106.

25 This transfer could have been mediated through Theo van Doesburg, for example, who was not only very impressed by Melnikov’s building, but also knew Schawinsky well.

26 Schawinsky himself was surely in Cologne, because his parents lived there at that time.

Letter from Gropius to Schawinsky of 1930, estate papers of Xanti Schawinsky Estate, Zurich (see n. 10).

71 Walter Gropius, Projekt eines Wohnhochhauses, Deutsche Bauhausausstellung Berlin, Grafische Gestaltung Schawinsky, 1930/31

71 Walter Gropius, project of a high-rise apartment building, German Bauhaus Exhibition Berlin, graphic design Schawinsky, 1930/31

tung auch gewesen sein mögen, waren sie doch immer von einer sehr fortschrittlichen Intention und Gestaltung geprägt. Der Beitrag zur Hygiene-Ausstellung in Dresden unter dem Titel »Zusammenarbeit des Gesundheitsamtes mit den anderen Magistratsstellen: Personaluntersuchungen, Krankentransport, Säuglingspflegeunterricht, Bezirksfürsorge, Jugendfürsorge, Eheberatung«20 zeigte schließlich beispielhaft das ganze Spektrum einer modernen Stadtverwaltung mit ihren sozialen Vorteilen und Fördermöglichkeiten bis hin zur fortschrittlichen Reformpädagogik anschaulich bildlich aufgearbeitet und in großen Schautafeln sowie Modellen präsentiert.

20 Stichwort 12 (Februar 2 1931), S. 206. 21 Vgl. Briefwechsel Gropius/Schawinsky im Nachlass Schawinsky (wie Anm. 10), XST570-692. Zum Preis vgl. XST 578.1.

22 Vgl. zu den Häusern: deutsche bauzeitung 2006, zit. nach https://www.db-bauzeitung.de/ allgemein/in-die-jahre-gekommen-25/ (geprüft am: 23.01.2018).

23 Gropius an Schawinsky, 28.11.1931: »lieber Xandi, […] ich bitte dich ab Mittwoch, wenn irgendmöglich am Endspurt zu beteiligen und deinem Assistenten zu sagen, dass er sofort auf dem telegrammweg herkommt. über das gehalt in dem schon mit dir besprochenen sinne werden wir uns verständigen. Der sowjetpalast ist eine vergrößerte rotunde, stelle dich darauf ein. dein Pius«, Briefwechsel Gropius/Schawinsky im Nachlass Schawinsky (wie Anm. 10); vgl. Briefe Walter Gropius zum Wettbewerb: Selim O. Chan-Magomedov und Christian Schädlich (Red.): Avantgarde II 1924–37. Sowjetische Architektur, Stuttgart 1993, S. 113 ff., 214 ff.

24 Vgl. László Moholy-Nagy 1927 (wie Anm. 1), S. 106.

25 Die Vermittlung könnte bspw. über Theo van Doesburg erfolgt sein, der nicht nur von Melnikovs Gebäude sehr beeindruckt war, sondern den Schawinsky gut kannte.

26 Schawinsky selbst wird in Köln gewesen sein, da seine Eltern zu dieser Zeit hier lebten. Brief von Gropius an Schawinsky 1930, Briefwechsel Gropius/Schawinsky im Nachlass Schawinsky (wie Anm. 10).

Außer seiner Arbeit als Ausstellungsgestalter für das Hochbauamt sowie zahlreicher Aufträge für private Auftraggeber in Magdeburg bis Ende 1931 war Xanti Schawinsky auch immer wieder für Walter Gropius tätig.21 Für die Deutsche Bauausstellung fertigte er ab März 1931 die Schautafeln für Gropius’ »Projekt eines Wohnhochhauses mit Gemeinschaftsräumen«. Walter Gropius selbst war es, der ihm dann die Kopie eines gemeinsamen Preises, mit dem sie für dieses Projekt ausgezeichnet worden waren, zuschickte. (Abb. 70, 71) Aus dem umfangreichen Briefverkehr zwischen Walter Gropius und Xanti Schawinsky wird nicht nur die große Vertrautheit beider deutlich, sondern es findet auch das eine oder andere Projekt Erwähnung – so die Herstellung eines Werbeprospektes für die Kupferhäuser der Firma Hirsch-Adler, für deren Überarbeitung Gropius auf der Weltausstellung 1931 in Paris einen Preis gewann. Eben jener Prospekt wurde damals von Schawinsky gestaltet und bei Wohlfeil in Magdeburg gedruckt.22 Auch für die Umsetzung der Schautafeln anlässlich des Internationalen Wettbewerbs zum Palast der Sowjets in Moskau, zu welchem Gropius neben Le Corbusier und Erich Mendelsohn eingeladen worden war, war Gropius, wie so oft, auf die Mithilfe Schawinskys angewiesen.23 Am auffälligsten für alle von Xanti Schawinsky gestalteten Schautafeln ist, dass er einzelne Figuren aus eigenen Fotografien herausschnitt und diese zu neuen szenischen Darstellungen zusammensetzte. Eine Kompilationsmethode, die Moholy-Nagy »Fotoplastik«24 nannte und die Schawinsky nur wenige Jahre später in den Bildfolgen der Spectodramen am Black Mountain College zur Perfektion geführt hat. (Abb. 36–39) Stets ungewöhnlich bleibt die Größe und Formenvielfalt der verwendeten Typografien und des Bildmaterials sowie der unglaublich kreative Umgang mit den vorhandenen Materialien. Insbesondere die starken Fotovergrößerungen, wie Schawinsky sie bereits 1929 für den Messestand von Junkers & Co auf der Ausstellung »Gas und Wasser« in Berlin verwendete, sind bemerkenswert. Dass Schawinsky ein Meister in der Zusammenstellung von Ideen war, mag ihm auch hier zugutegekommen sein. Gerade die Verwendung des Collageprinzips, die Erfahrungen der Bühnengestaltung und die Kenntnis der Möglichkeiten, Bilder in Überlebensgröße nutzbar zu machen, dürfte auf entsprechenden Kontakten bzw. der direkten Anschauung des von Konstantin Melnikov entworfenen Pavillons der Pariser Expo von 1925 und dem darin gesetzten hohen Standard für formale Dynamik und innovativen Materialeinsatz beruht haben.25 Vielleicht war es aber auch die Kenntnis der 1928 in Köln veranstalteten wegweisenden Messe »Pressa«, auf der unter den 1500 Ausstellern aus 43 Ländern besonders der sowjetische Pavillon mit raumhohen Fotocollagen El Lissitzkys für große Aufmerksamkeit sorgte.26 Zumindest lässt sich aus dem Briefwechsel mit Gropius ableiten, dass jener das technische Können Schawinskys in diesem Bereich, sein Verhandlungsgeschick, seine Kontakte und seine Kreativität persönlich sehr hoch schätzte. Dies prädestinierte Schawinsky schließlich 1939 dafür – dann schon von New York aus –, gemeinsam mit Herbert Bayer den von Walter Gropius und Marcel Breuer erbauten »Pennsylvania Pavillon« sowie in Eigenregie den »North Carolina Pavillon« auf der Weltausstellung in New York auszustatten. Im Manuskript zur Ausstellung heißt es, die Pavillongestalter würden »mit wenigen, dafür aber groß eingesetzten Aussageträgern

Breuer for the World’s Fair in Paris as well as the ‘North Carolina Pavilion’ on his own. The manuscript for the exhibition states that the pavilion designers had ‘achieved a particularly intense effect among visitors through few, but monumentally utilised vehicles of expression’.27 Schawinsky was aware of the effectiveness of advertising efforts: ‘The art of advertising is still young and finds itself at the beginning of an important evolution. Bound to the epoch, it has to work with an orderly precision in which the personal recedes in favour of the super-personal. And it finds itself in a strange situation: beyond a readily grasped demonstration and a simplification of the complex into elementary representations and simple manifestations, there is the ordering, creative fantasy of a functional advertising.’28

In the 1930s, Schawinsky was enthusiastic about the ‘materials that technology has placed at our disposal: […] their ease and elegance and their own characteristic transparency. Colourful crystal panels, Erinoid, cellophane, the delicate aluminium skeleton of the Zeppelins, chrome, photography and film, graphic creations of melodious harmonies, the grid, television, hard rubber, curving tubular steel, spray and enamel techniques, fluorescent paints, perforated panels, glass […]’.29

This enthusiasm is particularly apparent in the photographs created during his period in Magdeburg: experimentation and playing with motifs and forms created a store of material encompassing the dolls’ heads he photographed for the Nehab company as well as the props in the theatre workshops and so many other motifs. The store of photographs he compiled at that time would accompany him on his way throughout the years and was repeatedly utilised from the period he spent working for the Italian advertising industry to his photograms of the 1960s. His spectodramas – some of which can be traced back to ideas from 1926 – also make repeated use of his storehouse of photographs from the 1930s.

72 North Carolina Pavillon auf der Weltausstellung New York 1939

72 North Carolina Pavilion for World‘s Fair, New York 1939

27 See Xanti Schawinsky (see n. 8), pp. 209–10. Letter from Schawinsky to Gropius, Xanti Schawinsky Estate, Zurich (see n. 10), XST 619.1.

28 ‘Xanti Schawinsky 1935’ in: ‘Publicitá funzionale, 1935’, Lúfficio moderno, La Pubblicitá, Rivista mensile (October 1935), n. pag., cited in: (German trans. Ingeborg Ferraresi), Xanti Schawinsky (see n. 8), pp. 205–6.

29 Ibid.

73 Pennsylvania Pavillon auf der Weltausstellung New York 1939

73 Pennsylvania Pavilion for World‘s Fair, New York, 1939

bei den Besuchern eine besonders intensive Wirkung erzielen«.27 Schawinsky ist sich der Wirkung von Werbemaßnahmen bewusst: »Die Werbekunst ist noch jung und befindet sich am Anfang einer bedeutenden Entwicklung. Gebunden an die Epoche, muss sie in geordneter Präzision arbeiten, in der das Persönliche zugunsten des Überpersönlichen zurücktritt. Und sie befindet sich in einer sonderbaren Situation: jenseits einer gelehrigen Demonstration und einer Vereinfachung des Komplizierten auf elementare Darstellungen und einfache Erscheinungen steht die ordnende, schöpferische Phantasie einer funktionalen Werbung.«28

Schawinsky war in den 1930er Jahren begeistert von den »Materialien, die uns die Technik zur Verfügung gestellt hat: […] ihre Leichtigkeit und Eleganz und eine ihnen eigene Durchsichtigkeit. Bunte Kristallplatten, Galalith, Cellophan, das feine Aluminiumskelett der Zeppeline, das Neon, die Verchromung, die Fotografie und der Film, grafische Schöpfungen von wohlklingenden Harmonien, das Raster, das Fernsehen, der Hartgummi, gebogene Stahlrohre, Spray- und Lackierungstechniken, die Leuchtfarben, die Lochplatten, das Glas […]«.29

Diese Begeisterung ist nicht zuletzt den in der Magdeburger Zeit entstandenen Fotografien anzusehen, das Ausprobieren, das Spiel mit Motiven und Formen schafft einen Fundus, zu dem die Puppenköpfe, die er für die Firma Nehab fotografierte, wie auch die Requisiten in den Theaterwerkstätten und so manches andere Motiv gehören. Der damals angelegte Fundus an Fotografien begleitete ihn über die Jahre hinweg und fand in der Zeit seiner Arbeit für die italienische Werbebranche bis zu seinen Fotogrammen der 1960er Jahre immer wieder Verwendung. Auch für seine späteren Spectrodramen, die teilweise auf Ideen aus dem Jahr 1926 zurückgehen, griff er immer wieder auf seinen Fotofundus der 1930er Jahre zurück.

27 Vgl. Xanti Schawinsky Ausstellungskatalog 1986 (wie Anm. 8), S. 209–210; zum Beitrag Schawinskys: Brief Schawinskys an Gropius und Breuer vom 09.11.1938, Briefwechsel Gropius/Schawinsky im Nachlass Schawinsky (wie Anm. 10), XST 619.1.

28 Schawinsky, Xanti: »Pubblicitá funzionale«, in: L’ufficio moderno, La Pubblicitá, Rivista mensile, Oktober 1935, o. S., (übersetzt v. Ingeborg Ferraresi), zit. nach Xanti Schawinsky Ausstellungskatalog 1986 (wie Anm. 8), S. 205–206.

29 Ebd.

74 ohne Titel, Schanktisch, 1929/30

74 Untitled. Bar counter, 1929/30

75 ohne Titel, Glühbirne, gespiegelt, 1929/30

75 Untitled. Light Bulb, mirrored, 1929/30

76 ohne Titel, Reagenzgläser, 1929/30

76 Untitled. Test Tubes, 1929/30

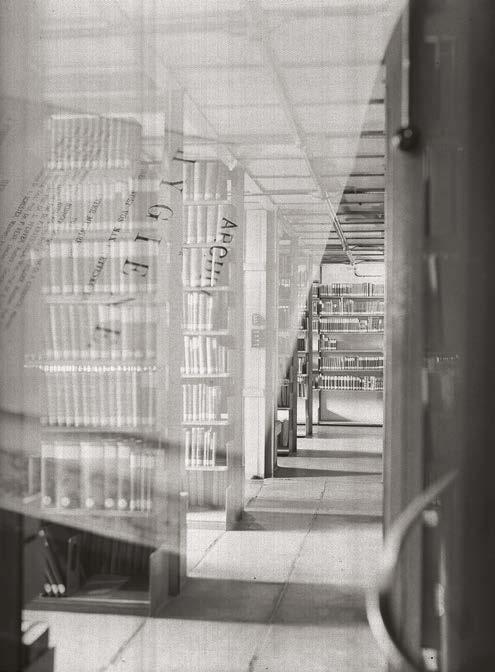

77 ohne Titel, Hygienearchiv, Fotografie einer Doppelbelichtung, 1929/30

77 Untitled. Hygiene archive, photography of a double exposure, 1929/30

78 ohne Titel, Damenschuhe im Schuhhaus Delphi, gespiegelt, 1929/30

78 Untitled. Women’s shoes, mirrored, 1929/30

79 ohne Titel, Kristall, 1929/30

79 Untitled. Crystal, 1929/30

80 ohne Titel, Topf (Detail) in der Ausstellung »Die Frau«, 1930

80 Untitled. Pot (detail) in the exhibition The woman, 1930

81 ohne Titel, Internationale Hygiene-Ausstellung Dresden, 1930

81 Untitled. Hygiene exhibition Dresden, 1930

82 ohne Titel, Internationale Hygiene-Ausstellung Dresden, 1930

82 Untitled. International Hygiene Exhibition Dresden, 1930

83 Puppen Firma Hugo Nehab, Magdeburg, 1929/30

83 Dolls by Hugo Nehab, Magdeburg, 1929/30

84 Puppen Firma Hugo Nehab, Magdeburg, 1929/30

84 Dolls by Hugo Nehab, Magdeburg, 1929/30