Eine Veröffentlichung des | A publication of the | Une publication du Max Ernst Museum Brühl des LVR

Herausgegeben von | Edited by | Édité par Madeleine Frey & Friederike Voßkamp

Wissenschaftliches Konzept | Scientific Direction | Direction scientifique Laura Braverman & Friederike Voßkamp

In Kooperation mit | In collaboration with | En collaboration avec

Jürgen Wilhelm

6 Prolog: Alberto Giacometti zu Gast bei Max Ernst

8 Prologue: Alberto Giacometti as Max Ernst‘s Guest

10 Prologue : quand Alberto Giacometti rend visite à Max Ernst

Madeleine Frey

12 Surrealistische Entdeckungen: Eine Einführung in die Ausstellung

16 Unveiled Surrealism: Introduction to the Exhibition

19 Le surréalisme dévoilé : Introduction à l‘exposition

Laura Braverman

23 Alberto Giacometti und der Surrealismus: eine kontinuierliche Bewegung

35 Alberto Giacometti and Surrealism: A Continuous Movement

46 Alberto Giacometti et le surréalisme : un mouvement continu

Friederike Voßkamp

59 Alberto Giacometti und Max Ernst: Zufällige Begegnungen

68 Alberto Giacometti and Max Ernst: Chance Encounters

76 Alberto Giacometti et Max Ernst : rencontres fortuites

85 Werke Works Œuvres

202 Verzeichnis der ausgestellten Werke List of Exhibited Works Liste des œuvres exposées

206 Impressum Credits Crédits

Es entspringt einem lang ersehnten Traum und erfüllt einen großen Wunsch, wohl einen der bedeutendsten Bildhauer des 20. Jahrhunderts als Gast im Max Ernst Museum Brühl des LVR willkommen heißen zu können. Die Fondation Giacometti hat diese Begegnung ermöglicht, wofür wir außerordentlich dankbar sind.

Die langjährige Bekanntschaft zwischen Max Ernst und Alberto Giacometti ist mehr als nur eine Künstlerfreundschaft. Wie sich mit der Lektüre dieses Katalogs zeigen wird, trägt die Freundschaft dieser beiden Ausnahmekünstler über die surrealistische Bewegung hinaus. Sie war nicht nur freundschaftlicher Natur, von großem Respekt für den jeweils anderen geprägt, sondern steht auch im Kontext künstlerischer Entwicklung.

Bereits 1929 erfährt Giacometti große Aufmerksamkeit mit seinen als Scheibenplastiken bezeichneten Skulpturen. Gleichwohl findet die Initialzündung, die André Breton veranlasst, ihn offiziell Teil der surrealistischen Bewegung werden zu lassen, erst 1930 statt. Werke, die er in der Galerie von Pierre Loeb in Paris gemeinsam mit Hans Arp und Joan Miró zeigt, überzeugen durch ihre große Abstraktionskraft und Symbolik. Breton bezog sich einmal auf Giacometti wie folgt: „Was ist Surrealismus? [...] Das ist (unter anderem) Alberto Giacomettis Kampf mit dem Engel des Unsichtbaren, der sich mit ihm in den blühenden Apfelbäumen verabredet hat.“1

Giacometti lernt rasch die damalige surrealistische Avantgarde kennen, neben Arp und Miró auch die Maler und Bildhauer André Masson und Salvador Dalí sowie die Schriftsteller Georges Bataille, Michel Leiris, Robert Desnos, Raymond Queneau und natürlich auch Max Ernst. Im Sommer 1935 treffen sich Ernst und Giacometti in der schweizerischen Heimat Giacomettis in Maloja. Es wird eine private

und auch arbeitsintensive Zeit. Die Grundlage dafür waren gemeinsame Ausflüge in die umliegenden Berge Graubündens, auf den Fornogletscher, wo sie von unterschiedlich geformten Granitblöcken fasziniert sind. Mit Unterstützung eines Pferdegespanns schaffen sie die Felsblöcke zum Haus von Giacomettis Familie und geraten in einen Arbeitsrausch, den Max Ernst selbst „Fieber“ nennt. Die Bildhauerei nimmt sie in diesen Tagen von einer völlig anderen, vielleicht unerwarteten Seite in Anspruch, die vor allem bei Ernsts bisherigen skulpturalen Werken keine Rolle gespielt hat. Max Ernst schreibt dazu: „Wir bearbeiten große und kleine Granitblöcke aus den Moränen des Fornogletschers. Durch Zeit, Eis und Wetter wunderbar abgeschliffen, sehen sie schon an sich phantastisch schön aus. Da kann die Menschenhand nicht mit. Warum also nicht die große Arbeit den Elementen überlassen und uns begnügen runenartig unsere Geheimnisse in sie einzuritzen?“ 2 Einige Ergebnisse dieser bildhauerischen Arbeit sind im Max Ernst Museum zu sehen und werden nun Teil der Ausstellung.

Zu der Zeit der gemeinsamen Arbeit der beiden Künstlerfreunde in Majola war Giacometti bereits aus dem Kreis der Surrealisten ausgeschlossen. Ein Grund dafür war, dass er sich zunehmend der Arbeit nach der Natur und dem Modell zugewandt hatte, was die Surrealisten als ihren Überzeugungen widersprechend abqualifizierten. Breton soll sich dazu folgendermaßen geäußert haben: „Ein Kopf, jedermann weiß doch, was ein Kopf ist.“3 Infolge der Weigerung Bretons, Giacomettis neue Arbeitsweise zu akzeptieren, und nachdem er aus der surrealistischen Gruppe ausgeschlossen worden war, widmete sich Giacometti fast ausschließlich dem Gegenstand, der Figuration im weitesten Sinne.4

Giacometti warf später aber keineswegs sämtliche während seiner Zeit als Surrealist gemachten Erfahrungen über Bord. Auch wenn die Faszination, das Einmalige seiner Kunst darin liegt, dass er stets versuchte, das Wesen der Dinge

zu erfassen, um sie in ihrer Komplexität als Skulpturen zur Geltung kommen zu lassen, so ist doch ein „surrealistischer“ Geist in seinem Werk zu spüren, der sich trotz seiner Trennung vom Kreis der Surrealisten in vielen späteren Arbeiten erkennen lässt.

Den Auswirkungen der Begegnung zweier Weltkünstler des 20. Jahrhunderts nachzuspüren, die über Jahre und jenseits der Zugehörigkeit zur surrealistischen Gruppe Gemeinsames verfolgten, ist eine wichtige Aufgabe des Max Ernst Museums Brühl des LVR – und dieser Ausstellung.

Prof. Dr. Jürgen Wilhelm Vorsitzender des Vorstands der Stiftung Max Ernst

1 André Breton, handschriftliche Notiz auf der Umschlagseite von Alberto Giacomettis Exemplar von Was ist Surrealismus? (1934), zit. n. Reinhold Hohl, Alberto Giacometti, Stuttgart 1971, S. 248.

2 Max Ernst an Carola Giedion-Welcker, abgedruckt in: Werner Hofmann, Die Plastik des 20. Jahrhunderts (Fischer-Bücher des Wissens, Bd. 239), Frankfurt am Main 1958, S. 88–97.

3 André Breton, zit. n. Simone de Beauvoir, La force de l’âge, Paris 1960, S. 499–500.

4 Siehe hierzu Werner Spies, „Alles entschlüpft“, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 25. 1. 1992, Beilage Nr. 21.

To host Alberto Giacometti, undoubtedly one of the most important sculptors of the twentieth century, as a guest at the Max Ernst Museum Brühl of the LVR is the culmination of a long-standing dream and the fulfillment of a heartfelt wish. This encounter has been made possible by the Fondation Giacometti, to whom we are extremely grateful.

The long-lasting relationship between Max Ernst and Alberto Giacometti cannot be reduced to that of a simple friendship between artists. As one will realize upon reading this catalogue, the friendship of these two exceptional artists went beyond their participation in the surrealist movement. It was not only of an affective nature, marked by immense mutual respect, but it also unfolded within the context of their artistic evolution.

As early as 1929, Giacometti attracted great attention with his works known as “flat” sculptures. However, it was not until 1930 that the initial spark arose, leading André Breton to make him an official member of the surrealist movement. The works that Giacometti presented in Paris, alongside those of Jean (Hans) Arp and Joan Miró, at the Pierre Loeb Gallery, convinced the public with their heightened abstraction and symbolism. Breton once evoked Giacometti as follows: “What is Surrealism? . . . It is, among other things, Alberto Giacometti’s battle with the angel of the Invisible who made an appointment with him in the blossoming apple trees.” 1

Giacometti quickly became acquainted with the surrealist avant-garde of the time: not only with Arp and Miró, but also with the painters and sculptors André Masson and Salvador Dalí, as well as the writers Georges Bataille, Michel Leiris, Robert Desnos, Raymond Queneau—and of course, Max Ernst. In the summer of 1935, Ernst and Giacometti met in Switzerland, in Maloja, in Giacometti’s native region.

This marked an intense period, on both a private and artistic level. The two artists embarked on excursions into the surrounding mountains of the Grisons, to the Forno Glacier, where they were fascinated by granite blocks of various shapes. Using a horse-drawn carriage, they brought the blocks back to Giacometti’s family home and were seized by a frenzy of work that Ernst himself described as a “fever.” During those days, sculpture absorbed them in a completely different way, which they had perhaps not expected, and which had certainly not played a role in Ernst’s sculptural works until then. Ernst wrote about it: “We are working on blocks of granite, small and large, from the moraines of the Forno Glacier. Wonderfully smoothed by time, ice, and weather, they already look fantastic in themselves. The human hand cannot compete. So why not leave the hard work to the elements and be content with engraving our secrets into them like runes?”2 Several of these creations are exhibited in the permanent collection of the Max Ernst Museum and are now presented here as part of this exhibition.

At the time when the two artist friends were working together in Maloja, Giacometti had already been excluded from the surrealist group. One reason for this was his increasing turn to work from nature and models, a practice the surrealists deemed contradictory to their convictions. In this regard, Breton reportedly said: “A head? Everyone knows what a head is!”3 In the wake of Breton’s refusal to accept Giacometti’s new direction, and his later exclusion from the surrealist group, Giacometti dedicated himself almost exclusively to figuration.4

However, Giacometti never completely renounced the experiences he had during his participation in the surrealist movement. And although the fascination exerted by the uniqueness of his art lies in his constant effort to grasp the essence of things, capturing them in all their complexity in

his sculptures, a “surrealist” spirit is still evident in his œuvre, and can be found in many works created after his departure from the group.

Tracing the effects of the encounter between two globally significant twentieth-century artists, whose approaches sometimes converged over the years and even beyond their affiliation with the surrealist group, is one of the main objectives of the Max Ernst Museum Brühl of the LVR—and of this exhibition.

Prof. Dr. Jürgen Wilhelm Chairman of the Board of the Max Ernst Foundation

1 André Breton, handwritten note on the cover page of Alberto Giacometti’s copy of Qu’est-ce que le surréalisme ? (Brussels: René Henriquez, 1934), quoted in Reinhold Hohl, Alberto Giacometti (New York: H. N. Abrams, 1972), p. 249.

2 Letter from Max Ernst to Carola Giedion-Welcker, reproduced in Werner Hofmann, Die Plastik des 20. Jahrhunderts, FischerBücher des Wissens, vol. 239 (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Verlag, 1958), pp. 88–97.

3 André Breton, quoted in Simone de Beauvoir, The Prime of Life, trans. Peter Green (London: Penguin, 1963), p. 387.

4 On this, see Werner Spies, “Alles entschlüpft,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, January 25, 1992, no. 21 supplement.

Pouvoir accueillir au Musée Max Ernst Brühl du LVR celui qui fut sans aucun doute l’un des plus grands sculpteurs du XXe siècle est l’aboutissement d’un rêve de longue date et la réalisation d’un souhait ardent. Cette rencontre a été rendue possible grâce à la Fondation Giacometti, et nous lui en sommes extrêmement reconnaissants.

Les liens qui ont uni pendant de nombreuses années Max Ernst et Alberto Giacometti ne se résument pas à une simple amitié d’artistes. Comme on pourra s’en rendre compte à la lecture de ce catalogue, l’amitié de ces deux artistes d’exception est allée au-delà de leur participation au mouvement surréaliste. Elle n’était pas seulement de nature affective, empreinte d’un immense respect réciproque : elle s’est également inscrite dans le contexte de leur évolution artistique.

Dès 1929, Giacometti suscite beaucoup d’attention avec ses sculptures qualifiées de « plates ». Pour autant, il faut attendre 1930 pour que jaillisse l’étincelle initiale qui conduit André Breton à faire de lui un membre officiel du groupe surréaliste. Les œuvres que Giacometti présente à Paris, aux côtés de celles de Jean (Hans) Arp et de Joan Miró, dans la galerie de Pierre Loeb, emportent la conviction du public par leur abstraction et leur symbolique exacerbées. Breton a un jour évoqué Giacometti en ces termes : « Qu’est-ce que le surréalisme ? (…) C’est la lutte d’Alberto Giacometti contre l’ange de l’Invisible qui lui a donné rendez-vous dans les pommiers en fleurs1 ».

Giacometti fait rapidement la connaissance de l’avantgarde surréaliste de l’époque : non seulement Arp et Miró, mais également les peintres et sculpteurs André Masson et Salvador Dalí, ainsi que les écrivains Georges Bataille, Michel Leiris, Robert Desnos, Raymond Queneau – et bien entendu Max Ernst. À l’été 1935, Ernst et Giacometti se retrouvent

en Suisse, à Maloja, dans la région natale de Giacometti. S’ouvre alors une période intense, tant sur le plan privé que sur celui du travail. Les deux artistes entreprennent des excursions dans les montagnes des Grisons, sur le glacier de Forno, où ils sont fascinés par des blocs de granite aux formes variées. Au moyen d’une carriole tirée par des chevaux, ils rapportent les blocs à la maison de la famille Giacometti et sont saisis d’une ivresse de travail que Max Ernst lui-même qualifie de « fièvre ». Pendant ces journées, la sculpture les absorbe par un biais tout à fait différent, auquel ils ne s’attendaient peut-être pas, et qui en tout cas n’avait joué aucun rôle jusqu’à présent dans le travail plastique de Max Ernst. Il écrit à ce sujet : « Nous travaillons de petits et de grands blocs de granite, provenant des moraines du glacier de Forno. Magnifiquement polis par le temps, la glace et les intempéries, ils sont déjà en soi d’une beauté fantastique : la main de l’homme ne peut rivaliser. Mais pourquoi ne pas laisser travailler les éléments et nous contenter d’y graver nos secrets comme des runes2 ? ». Certaines de ses réalisations sont exposées dans le parcours permanent du Musée Max Ernst et sont présentées dans cette exposition.

Au moment où les deux artistes travaillent ensemble à Maloja, Giacometti a déjà été exclu du groupe surréaliste. En effet, il revient de plus en plus au travail d’après nature et d’après modèle, ce que lui reprochent les surréalistes qui jugent cette attitude contraire à leurs convictions. À ce sujet, Breton aurait eu ces mots : « Une tête ? Tout le monde sait ce que c’est3 ! ». Breton ayant refusé la nouvelle orientation de son travail, Giacometti, une fois exclu du groupe surréaliste, se consacre presque exclusivement à la figuration4 .

Mais jamais Giacometti ne renia les expériences qu’il avait faites lors de sa participation au mouvement surréaliste. Même si la fascination qu’exerce cet art unique tient à ses efforts constants pour saisir l’essence des choses et en restituer toute la complexité dans ses sculptures, on sent

tout de même dans son œuvre un esprit « surréaliste » que l’on retrouve dans de nombreux travaux postérieurs à son départ du groupe.

Examiner les effets de la rencontre de deux artistes d’envergure mondiale du XXe siècle, dont les démarches, par-delà les années et l’appartenance au groupe surréaliste, convergèrent parfois, est l’un des principaux objectifs du Musée Max Ernst Brühl du LVR – et de cette exposition.

Pr Dr Jürgen Wilhelm

Président du comité directeur de la Fondation Max Ernst

1 André Breton, note manuscrite sur la page de garde de l’exemplaire de Qu’est-ce que le surréalisme (Bruxelles : René Henriquez, 1934) appartenant à Alberto Giacometti, cité d’après Reinhold Hohl, Alberto Giacometti, Stuttgart, Gert Hatje, 1971, p. 248.

2 Max Ernst à Carola Giedion-Welcker, lettre reproduite dans : Werner Hofmann, Die Plastik des 20. Jahrhunderts (FischerBücher des Wissens, vol. 239), Francfort/Main, Fischer, 1958, p. 88-97.

3 André Breton, cité d’après Simone de Beauvoir, La force de l’âge, Paris, Gallimard, 1960, p. 499-500.

4 Voir à ce sujet Werner Spies, « Alles entschlüpft », Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 25.01.1992, supplément n° 21.

Die Ausstellung Alberto Giacometti – Surrealistische Entdeckungen im Max Ernst Museum Brühl des LVR präsentiert eine Facette des Bildhauers, die bislang kaum im Fokus seiner Rezeption stand. Giacometti ist insbesondere bekannt für seine schmalen, grazilen Figuren, die sich im Nichts aufzulösen scheinen und die Betrachtenden über die Aspekte von Raum und Bewegung in der Skulptur nachdenken lassen. Doch bevor Giacometti in den Nachkriegsjahren mit seinen ikonischen Figuren eine neue plastische Ausdrucksform entwickelte, schuf er ein außerordentlich qualitätsvolles Œuvre, das sich als Auseinandersetzung mit den Ideen des Surrealismus begreifen lässt. In dieser Zeit tauschte er sich eng mit Max Ernst aus, dem er sich künstlerisch wie freundschaftlich verbunden fühlte. Die Ausstellung nimmt die enge Verbundenheit der beiden Ausnahmekünstler als Ausgangspunkt, um das Frühwerk Giacomettis und seine Nachkriegsarbeiten bis in die 1960er-Jahre wechselseitig in Beziehung zu setzen.

Betrachtet man die Biografien von Max Ernst und Alberto Giacometti, ergeben sich einige Parallelen, die möglicherweise dazu beigetragen haben, dass beide eine langjährige Freundschaft pflegten, die weit über ihr Interesse an der surrealistischen Bewegung hinausging. Ernst und Giacometti zog es unabhängig voneinander zu Beginn der 1920er-Jahre nach Paris. Sie hofften gleichermaßen, von dort aus ihre noch junge Karriere voranzutreiben und vor allem ihre künstlerischen Ideen weiterzuentwickeln. Beide Künstler kamen aus der Provinz: Max Ernst wurde in Brühl geboren, Alberto Giacometti im Bergell, im italienischsprachigen Teil des Kantons Graubünden. Beide erhielten durch ihre Väter einen ersten Einblick in die Kunst und deren Techniken. Während Giacometti zunächst kurz an der Kunstakademie, dann an der Kunstgewerbeschule in Genf lernte und später nochmals in Paris an der Académie de la Grande Chaumière ohne Abschluss studierte,1 war

Ernst an der Universität Bonn in geisteswissenschaftlichen Fächern eingeschrieben (Philosophie, Psychologie, Kunstgeschichte). Doch stand bei beiden Künstlern das autodidaktische Lernen im Vordergrund.

In ihrem künstlerischen Schaffen orientierten sie sich zunächst an den dominierenden Strömungen ihrer Zeit. Einige Bilder im Max Ernst Museum zeugen von diesem ersten Experimentieren (Abb. 1 und 2). Die frühen Skulpturen von Giacometti referieren ebenfalls auf die vorherrschenden Kunstströmungen des ausgehenden 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhunderts, von denen sich Giacometti wie auch Ernst im Laufe ihres Schaffens emanzipierten.

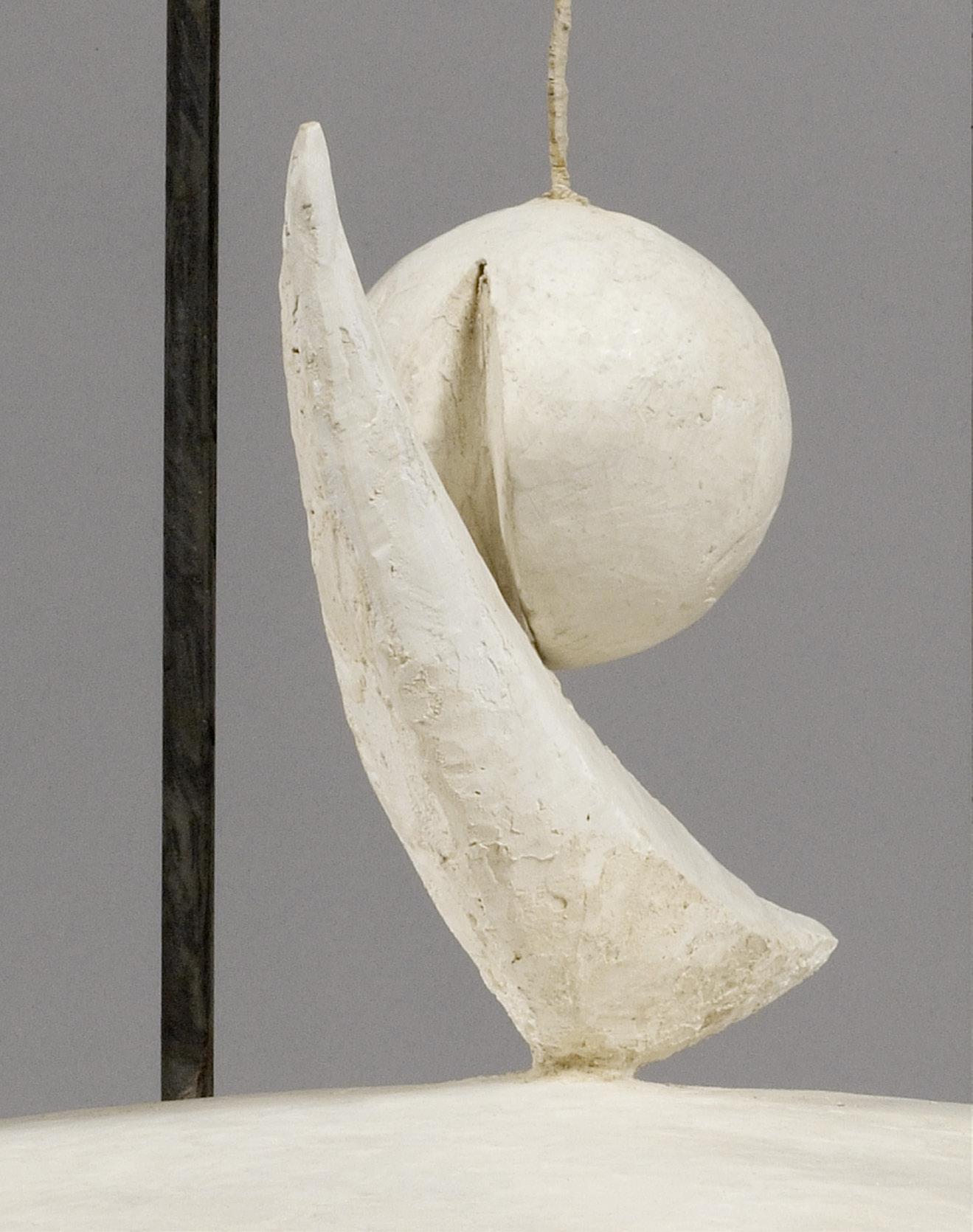

Die Vorkriegsarbeiten Giacomettis aus Paris, die in der Brühler Ausstellung gezeigt werden, die sogenannten „Scheibenskulpturen“ (Kat.-Abb. S. 98–99, S. 101 und 102–103), zeugen von seiner postkubistischen Phase. Die Femme (plate III), die zwischen 1927 und 1929 entstand (Kat.Abb. S. 102–103), kann als eine Auseinandersetzung mit der Figur im Raum verstanden werden.2 Giacometti arbeitete mit geometrischen Körpern, mit Kuben, Quadern und kugelförmigen Elementen. Weiterhin ließ er sich von afrikanischer und ozeanischer indigener Kunst inspirieren, um so eine Vereinfachung und Reduktion der Form zu erreichen, wie es in der Femme-cuillère (1927) (Kat.-Abb. S. 98–99) deutlich wird.3 Doch sah er sich nach wie vor mit dem Problem konfrontiert, den die Skulpturen umfließenden Raum auf adäquate Weise darzustellen. Mit den Gitterskulpturen wie Femme couchée qui rêve (1929) (Kat.-Abb. S. 105) wird der starre Körper aufgelöst, sodass der Raum in die durchbrochene Plastik integriert wird.4 In der Ausführung seiner Skulpturen bleibt für ihn jedoch weiterhin ein Widerspruch, der darin besteht, die starre Figur aus der Wahrnehmung zwischen Raum und Zeit herauszulösen. Mit der Boule suspendue (1930) (Kat.-Abb. S. 109–110) nähert er sich der Lösung dieses Problems, indem er die imaginierte

Bewegung, er versteht es auch als eine traumhafte Begegnung5, in seiner Arbeit mitdenkt. Eine Kugel ist in einen Käfig eingebettet, an einem Drahtseil schwebt sie über einer konkaven Form. Als Plastik ist diese Arbeit starr, doch kann sie in der Imagination der Betrachtenden bewegt werden. Giacometti thematisiert damit erstmals die Bewegung in seiner Arbeit und führt gleichzeitig die Idee des Dadaismus fort, das Publikum in die Kunst einzubeziehen.6 Diese Form der Aktivierung und der Bewegung wird ein wichtiger Aspekt im weiteren Verlauf seines künstlerischen Schaffens. Der gleichsam von der bewegten Kugel in Gang gesetzte Imaginationsprozess ist schließlich auch der Türöffner zum Kreis der Surrealisten um André Breton, in den er 1930 aufgenommen wird. Doch ist die Zugehörigkeit zu dieser Gruppe von kurzer Dauer, denn schon im Frühjahr 1935 wird er aus der Gruppe wieder ausgeschlossen – die Freundschaft mit Max Ernst bleibt weiterhin bestehen.

Als sich Giacometti nach und nach von der surrealistischen Gruppe entfernt, sucht er nach Antworten auf die Frage, wie er seine Figuren im Raum verorten und die Wirklichkeit abbilden kann. Zunächst werden die Körper immer kleiner, bis sie zusehends auch schmaler werden.7 Während Giacometti die Figuren geradezu marginalisiert, stehen sie im Kontrast dazu auf einem immer markanteren Sockel, so etwa die Quatre figurines sur piédestal (Figurines de Londres, version B) (1950) (Kat.-Abb. S. 186). Mit der Akzentuierung einer sich fast auflösenden Figur auf einem im Vergleich dazu sehr präsenten Grund löst Giacometti die Grenzen zwischen Realem und Imaginärem auf.8 Durch das Schrumpfen der Figur auf Miniaturgröße dehnt der Künstler den Raum ins Unendliche aus.9 Die Form des Käfigs, die er bereits 1930 in der Boule suspendue verwendet, nutzt er auch in seinen Werken der Nachkriegszeit, wie etwa bei Le Nez (1949) (Kat.Abb. S. 161–163), als „Verräumlichung des Körpers“ 10, was die Dreidimensionalität der Figuren betont und wie eine Art Bilderrahmen wirkt.11

Die Ausstellung Alberto Giacometti – Surrealistische Entdeckungen zeigt rund 60 Kunstwerke von Giacometti und einige Arbeiten von Max Ernst, wobei vor allem die während des gemeinsamen Aufenthalts in Maloja entstandenen Werke hervorzuheben sind. Verknüpft werden die Exponate mit biografischen Zeugnissen beider Künstler, ergänzt um Fotografien und Zeichnungen.

Die Ausstellung wurde anlässlich des 100-jährigen Jubiläums des surrealistischen Manifests gemeinsam mit der Fondation Giacometti erarbeitet. Mein herzlicher Dank gilt Catherine Grenier, der Direktorin der Fondation Giacometti, die die einmaligen Exponate in die Obhut des Max Ernst Museums gegeben und so ein Ausstellungshighlight ermöglicht hat. Die Ausstellung und der Katalog sind nicht nur eine Hommage an Giacomettis Schaffen und seine langjährige Freundschaft mit Max Ernst, sondern auch ein Spiegel der künstlerischen Brüche und Kontinuitäten, die sein Werk durchziehen.

Mein Dank gilt den Kuratorinnen Dr. Friederike Voßkamp, der Sammlungsleiterin des Max Ernst Museums, und Laura Braverman, Kuratorin der Fondation Giacometti, für die Erarbeitung dieser einmaligen Schau. Danken möchte ich auch dem Vorsitzenden der Stiftung Max Ernst, Professor Dr. Jürgen Wilhelm, durch dessen Initiative der Erstkontakt nach Paris zustande kam. Mein besonderer Dank gilt dem ehemaligen Direktor des Max Ernst Museums, Dr. Achim Sommer; durch sein großes Engagement konnte die Kooperation mit der Fondation Giacometti auf den Weg gebracht und so diese Ausstellung realisiert werden. Für das eindrückliche Ausstellungsdesign und die Kataloggestaltung danke ich Mathias Beyer und Svenja Hoffritz. Dem Deutschen Kunstverlag möchte ich für die ausgezeichnete Kooperation und die Erstellung dieser Publikation meinen

Dank aussprechen. In enger Zusammenarbeit zwischen den Teams des Max Ernst Museums und der Fondation Giacometti sowie durch die Bereitschaft des Landschaftsverbands Rheinland, dieses Projekt in hohem Maße zu unterstützen, ist eine Ausstellung gelungen, die sich der Freundschaft zwischen Max Ernst und Alberto Giacometti widmet und die surrealistische Phase des Schweizer Künstlers in besonderem Maße würdigt.

1 Casimiro Di Crescenzo, „Die frühen Jahre in Paris“, in: Giacometti: Die Spielfelder, Ausst.-Kat. Hamburger Kunsthalle, 25. 1. – 19. 5. 2013, Hamburg 2013, S. 36–44, hier S. 36.

2 Annabell Görgen, „Die Spielfelder“, in: Hamburg 2013 (wie Anm. 1), S. 21–35, hier S. 27.

3 Michael Brenson, „Approaching Giacometti“, in: Giacometti, Ausst.-Kat. Wilhelm-Lehmbruck-Museum der Stadt Duisburg, 17. 9. – 21. 11. 1977, Duisburg 1977, S. 42–50, S. 43.

4 Di Crescenzo 2013 (wie Anm. 1), S. 41.

5 Görgen 2013 (wie Anm. 2), S. 27.

6 Ebd.

7 Siehe Reinhold Hohl, Alberto Giacometti, Stuttgart 1971, S. 143.

8 Di Crescenzo 2013 (wie Anm. 1), S. 32.

9 Markus Brüderlin, „Einführung – Skulptur und Höhle und der Ursprung des Raumes“, in: Alberto Giacometti, Ausst.-Kat. Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, 20. 11. 2010 – 6. 3. 2011, Wolfsburg 2010, S. 17.

10 Ebd., S. 29.

11 Di Crescenzo 2013 (wie Anm. 1), S. 32.

The exhibition Alberto Giacometti: Unveiled Surrealism at the Max Ernst Museum Brühl of the LVR presents a facet of the sculptor that has thus far scarcely been a focus of his reception. Giacometti is best known for his slender and graceful figures that seem to dissolve into nothingness, prompting viewers to reflect on the significance of space and movement in sculpture. However, before developing a new form of plastic expression with his iconic postwar figures, Giacometti created exceptionally high-quality work that can be understood as the fruit of his encounter with the ideas of Surrealism. At that time, he interacted frequently with Max Ernst, to whom he felt connected, both as an artist and a friend. Taking the close ties between these two exceptional artists as a point of departure, the exhibition sets up a dialogue between Giacometti’s early creations and those of the postwar period, up until the 1960s.

An analysis of Ernst and Giacometti’s biographies reveals parallels that may explain their long-lasting friendship, which went far beyond their shared interest in the surrealist movement. In the early 1920s, Ernst and Giacometti both decided to move to Paris. There, they both aspired to advance their budding careers and, above all, develop their artistic ideas. The two artists came from provincial areas: Max Ernst was born in Brühl, and Alberto Giacometti in the Val Bregaglia, in the Italian-speaking part of the canton of Graubünden. Both were introduced to art and its techniques by their fathers. Giacometti briefly studied at the École des BeauxArts and then at the École des Arts et Métiers in Geneva, before resuming his studies at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris, without obtaining a formal diploma.1 For his part, Ernst was enrolled in humanities—philosophy, psychology, art history—at the University of Bonn. But autodidactic learning was important for both artists.

Their artistic pursuits initially followed the dominant movements of their time. Several paintings in the Max Ernst Museum testify to this early experimentation (figs. 1 and 2). Giacometti’s early sculptures also reflect the prevailing art movements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, from which he—much like Ernst—would emancipate himself over the course of his career.

Giacometti’s prewar Parisian works, featured in the exhibition in Brühl—especially his “flat” sculptures (pp. 98–99, p. 101 and pp. 102–103)—testify to the artist’s post-Cubist phase. Woman (Flat III), created between 1927 and 1929 (pp. 102 –103), can be interpreted as a reflection on the figure in space.2 Giacometti was working with geometric bodies, cubes, parallelepipeds, and spherical elements. He was also inspired by African and Oceanic Indigenous art in order to reach simpler forms, as clearly evidenced by Spoon Woman (1927) (pp. 98–99).3 However, he continued to grapple with the problem of adequately representing the space surrounding his sculptures. With sculptures set within grids, such as Reclining Woman Who Dreams (1929) (p. 105), the rigid body is broken down so that the space is integrated into the perforated sculpture.4 In creating his sculptures, however, a contradiction remained in the need to free the static figure from the perception between space and time. With Suspended Ball (1930) (pp. 109–110), he came closer to solving this problem by incorporating imagined movement into his work, which he also understood as a dreamlike encounter.5 In a cage, a ball suspended by a wire hangs above a concave form. This work, though static as a sculpture, can be set in motion by the viewers’ imagination. Giacometti thus addressed movement in his work for the first time while also following a Dadaist idea: that of involving the audience with art.6 This type of activation and movement would become an important aspect of his work. Ultimately, the imaginary process triggered by Suspended Ball was also the key that opened the door to André Breton’s surrealist circle, into

which Giacometti was admitted in 1930. However, his membership in the group would be short-lived, since he would be excluded by the spring of 1935. His friendship with Max Ernst, however, would remain intact.

By gradually distancing himself from the surrealist group, Giacometti sought to understand how to situate his figures in space and represent reality. At first, his bodies became increasingly small, and then increasingly thin.7 While Giacometti markedly diminished his figures, they, in contrast, are set on increasingly prominent pedestals, as exemplified by Four Figurines on a Stand (London Figurines, Model B) (1950) (p. 186). By emphasizing an almost-dissolving figure on a conversely prominent base, Giacometti broke down the boundaries separating the real and the imaginary.8 The shrinking of his figures allowed the artist to extend space infinitely.9 The cage motif, used in 1930 with Suspended Ball, reappears in his postwar works, such as The Nose (1949) (pp. 161–163), allowing a “spatialization of the body.”10 It emphasizes the figures’ three-dimensionality and creates the impression of a picture frame.11

The exhibition Alberto Giacometti: Unveiled Surrealism presents around sixty works by Giacometti and several by Max Ernst. Of particular interest are the works produced during their stay in Maloja. The works presented are supplemented by photographic and documentary archives that testify to the ties between the two artists.

This exhibition is the result of a collaboration with the Fondation Giacometti on the occasion of the surrealist manifesto’s centenary. I extend my deepest thanks to Catherine Grenier, Director of the Fondation Giacometti, who, by entrusting these unique works to the Max Ernst Museum,

has made this flagship exhibition possible. The exhibition and catalogue are not only an homage to Giacometti’s work and his long-standing friendship with Max Ernst, but also a mirror of the artistic rifts and continuities that run through his œuvre.

My gratitude goes out to the curators Friederike Voßkamp, Head of Collection at the Max Ernst Museum, and Laura Braverman, Associate Curator at the Fondation Giacometti, for organizing this unique exhibition. I would also like to thank the Chair of the Board of the Max Ernst Foundation, Professor Jürgen Wilhelm, who initiated our first contact with Paris. I owe a special thanks to Achim Sommer, former director of the Max Ernst Museum. It was his commitment that made the cooperation with the Fondation Giacometti—and thus this exhibition—possible. For their impressive exhibition design and graphic design of the catalogue, I would like to thank Mathias Beyer and Svenja Hoffritz. I would like to express my gratitude to the Deutscher Kunstverlag for their outstanding cooperation and production of this publication. The close collaboration between the teams of the Max Ernst Museum and the Fondation Giacometti and the broad support of this project by the Landschaftsverband Rheinland have made it possible to successfully produce an exhibition dedicated to Surrealism in Giacometti’s work and to pay a special tribute to the friendship between Max Ernst and the Swiss artist.

1 Casimiro Di Crescenzo, “Die frühen Jahre in Paris,” in Giacometti: Die Spielfelder, exh. cat. Hamburger Kunsthalle, January 25–May 19, 2013 (Hamburg: Hamburger Kunsthalle, 2013), pp. 36–44, esp. p. 36.

2 Annabell Görgen, “Die Spielfelder,” in Giacometti: Die Spielfelder, pp. 21–35, esp. p. 27.

3 Michael Brenson, “Approaching Giacometti,” in Giacometti, exh. cat. Wilhelm-Lehmbruck-Museum, September 17–November 21, 1977 (Duisburg: Wilhelm-Lehmbruck-Museum, 1977), pp. 42–50, esp. p. 43.

4 Di Crescenzo, “Die frühen Jahre in Paris,” p. 41.

5 Görgen, “Die Spielfelder,” p. 27.

6 Ibid.

7 See Reinhold Hohl, Alberto Giacometti (London: Thames & Hudson, 1972), p. 169.

8 Di Crescenzo, “Die frühen Jahre,” p. 32.

9 Markus Brüderlin, “Introduction: The Origin of Space and Sculpture as an Everted Cavity: Giacometti’s Revolutionary Handling of Space as a Sculptural Concept,” in Alberto Giacometti, exh. cat. Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, November 20, 2010–March 6, 2011 (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2010), pp. 14–36, esp. p. 17.

10 Ibid., p. 29.

11 Di Crescenzo, “Die frühen Jahre,” p. 32.

Madeleine Frey

Le surréalisme dévoilé :

L’exposition « Alberto Giacometti : Le surréalisme dévoilé », organisée au Musée Max Ernst Brühl du LVR, présente une facette du sculpteur à laquelle sa réception a généralement accordé peu d’attention. Giacometti est surtout connu pour ses figures élancées et graciles qui semblent se dissoudre dans le néant, incitant à une réflexion sur les dimensions de l’espace et du mouvement dans la sculpture. Pourtant, avant de développer une nouvelle forme d’expression plastique avec ses figures emblématiques d’après-guerre, Giacometti a créé une œuvre d’une qualité exceptionnelle, qui peut être considérée comme le fruit de sa rencontre avec les idées du surréalisme. À cette époque, il échangeait beaucoup avec Max Ernst, auquel il se sentait lié tant sur le plan artistique qu’amical. Prenant comme point de départ les liens étroits qu’entretiennent ces deux artistes d’exception, l’exposition établit un dialogue entre les premières créations de Giacometti et celles d’après-guerre, jusque dans les années 1960.

Une analyse des parcours biographiques d’Ernst et de Giacometti révèle des parallèles qui pourraient expliquer la longue amitié qui les lie, dépassant largement leur intérêt pour le mouvement surréaliste. Au début des années 1920, Ernst et Giacometti prennent chacun la décision de partir pour Paris. Tous deux aspirent à y faire avancer leur carrière débutante et surtout y développer leurs idées artistiques. Les deux artistes viennent de province : Max Ernst est né à Brühl, Alberto Giacometti dans le val Bregaglia, dans la partie italophone du canton des Grisons. Tous deux ont été initiés à l’art et à ses techniques par leur père. Giacometti a très brièvement étudié à l’École des Beaux-Arts puis à l’École des Arts et Métiers de Genève, et reprend ses études à l’Académie de la Grande Chaumière à Paris, sans obtenir de diplôme formel1. De son côté, Ernst a été inscrit en sciences humaines – philosophie, psychologie, histoire de l’art – à l’université de Bonn. Mais l’apprentissage autodidacte était important pour les deux artistes.

Schwebende Kugel | Suspended

| Boule suspendue 1930 (Version von 1965 | 1965 version | version de 1965)

Schwebende Kugel

| Suspended Ball (detail) | Boule suspendue

1930 (Version von 1965 | 1965 version | version de 1965)