“All journeys have secret destinations of which the traveller is unaware”. Martin Buber

This book is dedicated to my very dear friend, Vivian Silver of Kibbutz Beeri, who was murdered in her home on 7 October 2023.

“All journeys have secret destinations of which the traveller is unaware”. Martin Buber

This book is dedicated to my very dear friend, Vivian Silver of Kibbutz Beeri, who was murdered in her home on 7 October 2023.

Vivienne Silver-Brody

First published in Hebrew under the title

by The Hebrew University Magnes Press

ISBN: 978-3-422-80263-6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2024942038

Design and production: Magen Halutz, Adam Halutz

Editing: Doron Narkiss

Copy-editing: Marc Shapiro

Editing and production: Yael Klein

This book was made possible by an anonymous contribution.

Distributed by Deutscher Kunstverlag/Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Genthiner Straße 13, 10785 Berlin, Germany www.deutscherkunstverlag.de www.degruyter.com

All measurements in the book are in centimeters (height × width) unless stated otherwise.

Every effort has been made by the author to trace the copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of the copyrighted photographs in this book. Some of the photographs fall under supplementary protection certificate (SPC) right. The publishers would be grateful to be notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

© All rights reserved by The Hebrew University Magnes Press Jerusalem 2024; Deutscher Kunstverlag, and Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston 2024

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Front cover: Yosef Schweig, First deep ploughing, Jezreel Valley, 1928

Back cover: Gideon Sella, Arab woman in the south Hebron Hills, 1978

Table of Contents

6 Acknowledgements

7 About the Book

8 Chapter One Personal Background

24 Chapter Two A Long Learning Process

80 Chapter Three How My Collection Was Built

92 Chapter Four Structural Divisions within the Collection

114 Chapter Five Photography in Palestine-Eretz Israel from the Late Nineteenth to the Mid-Twentieth Century

162 Chapter Six Photography in Israel from the Middle of the Twentieth Century to the End of the 1960s

210 Chapter Seven Continuity and Innovation, Late 1960s to Late 1970s

224 Chapter Eight End-of-Century Diversity

260 Chapter Nine Commentary

290 Chapter Ten Closing Comments

295 Contributing Writers

418 Bibliography

Numerous people have contributed their time and interest during the making of this book, and to them all I extend my sincere appreciation. The serious consideration extended to me by the guest writers has enriched and widened the scope of this work.

Professor Moshe Naor of the Department of Israel Studies of the University of Haifa read and commented on the manuscript. Doron Narkiss, who has been the editor of my other publications, has been a practical, caring and wise editor over many years. Dalya Odem, who was a student when I started out, helped with the cataloguing. My dear friend and my former German teacher, Rachel Ammon, assisted with the translations from German. Nobuya Yamaguchi of Ein Hod translated a text from Japanese. A number of photographers, friends, and scholars went out of their way to assist or to provide missing links and sources: Micha and Orna Bar-Am, Tomer Bein, Ettel and Dan Bibro, Shimon Gibson, Shuka Glotman, Yudit Kaplan, Lavy Shay, Nick Levison, Ruth Oren, Guy Raz, Ronit Shany, Rona Sela, Jean Michel de Tarragon of the École Biblique et Archéologique Française in Jerusalem, Shula Widrich, Naomi Zur, Nurit Ohanna, the other Vivian Silver, Shlomit Sapir, Amnon Wolk, the Schadeh family, Mimi Zreik, and the Boulos and Said families in Kfar Yasif – all participated in some way.

The editorial staff at the Hebrew University Magnes Press were more than supportive during the long preparation period. Yael Klein has supported me and helped publish the book in the best possible way. The designers Magen and Adam Halutz have made a book which showcases the many fine images and is both readable and beautiful. I thank Magnes Press’

Hebrew editor, Benny Mer, who has helped make the text more flowing and readable. My thanks to Chrissy Iemma for her patience.

Roy Brody, my beloved friend and husband, has shared, listened, suggested, and supported this long journey, and he has endured several years of meals not always appearing on time.

This book is devoted to my collection of Israeli photography. During the often mechanical and tedious process of cataloguing it, I became aware that the images in my collection did not fit conveniently into the overriding framework of a Zionist history; rather they suggested an integral view of the photographic histories of all the groups living in this land. I find it culturally stimulating that this emerges from the images I have found during the process of collecting. The established view sees a standoff in which each national group constantly repeats its own narrative. At times it may include the Other in negative or enemy form, or it may otherwise ignore, obscure or distort the Other. If the photographs are sorted chronologically, however, without preconceived notions, it is the variety of peoples and groups living here that catches the eye. Each group and sub-group has a certain way of life, customs, dress and traditions. A wide range of photographs allows us to see this broad perspective.

The evolution of my collection parallels simultaneously the process of my own awareness, leading me to suggest in broad strokes a chronological and stylistic synthesis of local photography. My collecting journey is a story of many people with shared historical backgrounds relating to this land. It has heightened my awareness not only of history, but also of the potential of photography to encompass the very fabric of life. I would like to believe that the dichotomy of the two nations in this land cannot be resolved until we look at one another within a shared history, and this includes a history of photography.

This book is the outcome of a collaborative effort, of two sets of personal choices: my own and

those of some sixty invited writers, each of whom adds an individual voice to the complex mosaic of this land. They have generously breathed wide knowledge, broad interpretation, and their own passion into the images they chose to describe. I have had the privilege of meeting almost all the authors individually. It was a journey I shall always remember, from one welcoming harbour to another. Many were drawn to photos of the 1940s, responding to the time and place from a very personal perspective, sometimes invoking their fathers or childhood memories. I believe that those most suited to write about these images are the people who live here, Jews and Arabs. They are more aware of the intricacies of the past and the present. Their texts create a coalescence and convergence which extend beyond the images, and I still believe in the possibility of a better future. The idea for this section is based on the Victoria and Albert Museum catalogue from 1983, PersonalChoice:ACelebration of Twentieth-Century Photographs Selected and IntroducedbyPhotographers,Painters,andWriters, which was given to me by Tim Gidal.

Chapter Two

During my academic studies in the United States in the late 1970s, I was exposed to extensive museum collections in the United States and England, but I knew nothing about Israeli photographic history. During the 1980s there was particular international interest in nineteenth-century photography, which included also the Middle East and Palestine. Sotheby’s specialized in auctions of nineteenthcentury works, but it took me time to understand that most of the images had been made exclusively for Westerners, by photographers for travellers who had come to this area of the world as tourists, pilgrims, or explorers.

I was intrigued by the exoticism of nineteenth-century albumen prints of this land made by Europeans and some local photographers. The images were so distant from the present day, and often the sites were no longer similar. After a few years, I realized that I was actually

Brogi, Group of

at the

8 April

Also known as the Gate of Mercy, this site has symbolic meaning for Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Travelling in the Holy Land in 1869 was to sleep in tents, to shoot for one’s dinner, and to move around on horseback or in a sedan chair. I am fascinated by the formal attire of most pilgrims during this period. It was not a simple matter to travel around the Holy Land and to appear as though it were an everyday event.

American Colony Studio, Bedouin tent encampment, c. 1900, albumen print, 10.5×13. During an interview with Prof. Mordecai Omer, Itzhak Danziger described the harmony between the desert landscape and the sheep which inhabited the land alongside the desert people. He explained: “A flock of sheep resembles a carpet, something which glides down the hill and covers the ground, the slope of the valley… Sheep are symbols, models… Through the sheep I reach what interests me, the soil, light and shade” (Omer, 1978: 365)

collecting images of the Holy Land seen in the context of Christian theology. These were photographs sold to Christian travellers looking to find a record of the places where Jesus lived, walked, and taught, as well as to uncover archaeological secrets. The images are multilayered markers, in which present-day interpreters may find romance and nostalgia, or perhaps colonial exploitation. They mirror their period and have retained for posterity their own truths, which we in the present must try to place in context. The images related to the sites that pilgrims visited, while diaries and books described the food, accessories, dinnerware, and bed linen – all of which were encountered during that era in tents, of course. This was a period enriched by images and literature, but often the extreme specificity of the descriptions obscured the contexts they depicted. It took me time to learn, for example, about the geo-political setting – the Ottoman Empire, the politics, the diverse populations, the economics and progress of the Industrial Revolution; how steamships fuelled a growing local tourism.

As I continued collecting, I wondered whether early local photography even existed, and whether there was an internal market for photographic images. If so, I asked myself, who were the photographers, and did they leave archives? These questions motivated me to investigate our common photo history. The process of discovery came with curating, seeing exhibitions, writing, and meeting photographers. When I started out, my research required many hours spent in libraries and archives, although today the Internet has radically improved the possibilities for accessing material.

Unlike some researchers, I believe that non-resident photographers and their oeuvre before the start of the new Jewish settlement in Palestine are a necessary part of the complex and diverse development of the medium in this land. Local photo history encompasses a long span under three ruling bodies – first the Ottomans, then the British, and now the Israelis. The study of photographs of this land from the midnineteenth century onwards reveals a kaleidoscope of images embracing an intercultural and multi-ethnic society. I could not have envisaged that photography could be so organically complex and interrelated.

Three of the earliest articles on local photography were written by photographer and historian Tim Gidal for the yearbooks of the

Chapter Seven

The book Israel/TheReality52 and the 1968 exhibition of the same name, held at the Jewish Museum in New York and later at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, were one of the first attempts to construct an historical overview of local early twentieth-century photographers. Together with well-known contemporary American, European and Israeli photographers, the book and the exhibition presented early twentiethcentury images by lesser known artists like Leo Kann (1894–1983), as well as by Avraham Soskin, Yaacov Ben Dov, and Zvi Orushkes.

Two curators, Yona Fisher at the Israel Museum and Micha BarAm slightly later at the Tel Aviv Museum, were intent on showing and supporting current photography by young artists. In 1973, the works of Drora Spitz (b. 1945) were shown at the Israel Museum; she has had a long creative career and is still working today.53 Her photographs contain dreamlike imagery: timelessness, luminosity, order, a complex layering of textures, all elements which combine to create images with depth and restrained passion. Although her vision is enhanced by her mastery of technical possibilities, her works deserve to be better known. The exhibition “Jerusalem – City of Mankind” opened at the Israel Museum in 1973, on the eve of the Yom Kippur War and was overlooked in the events of the war.54 But, the following year, the above-mentioned exhibition entitled “Situation: Israeli Photographers ’74” opened at the Israel Museum with the catalogue published jointly by the Museum and Israel Magazine. It included younger Israeli photographers, some of whom are in my collection. The curators Micha Bar-Am and Marc Scheps noted that it was “the first comprehensive show of Israeli photography within the walls of a museum. The twenty-one photographers are a cross-section of the country’s creative activity in this discipline”.55

This period is a perfect example of different generations creating in a wide variety of expressions. Marli Shamir and Amiram Erev

52. Capa, 1969.

53. Spitz, 2010.

54. Capa, 1974.

55. Bar -Am & Scheps, 1974.

intrusion into the drowsy, self-conscious collective amnesia. […] There were some who attacked his photographs as pornography because they saw nude buttocks and stomachs. Kirshner was infuriated and rightly so. “What is this bullshit, this cynicism? It’s true, these are revealing pictures. Why can’t you look at the buttocks of a 16-year-old boy, with his pelvis cut in half? In the same accusation, it is possible to exclude pictures of nude men or women? Just as the entrance to the gas chambers or the pits into which Jews were thrown can be considered pornographic”.67

In another interview published in the newspaper Hadashot in 1988, Shosh Abigail asked Kirshner if he missed Israel of yesteryear:

Yes, but I don’t want to return there. There is a distinction between nostalgia and longing […] There was hope then, and I long for hope. The constructive kind of Zionism – work, industry, kibbutz, and creativity. [...] There is an enormous muddle here and there are things that I do not long for.68

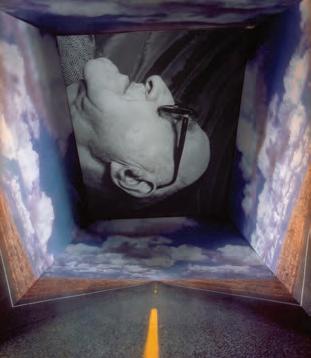

When I asked Kirshner about the making of the portrait of Prof. Yeshayahu Leibowitz, he replied:

I photographed Leibowitz at his home in black-and-white; there are also images in colour but I did not use them. I made a black-and-white print, then built a carton box, with perspective. On three sides I stuck a photograph of the sky and on the fourth side, the floor, a photograph of a road with an open view. The black-and-white photograph is the back panel. I photographed the “installation” that was created. Why a road? Because it leads to other far-off and interesting scenarios. Why the sky? Maybe because he [Leibowitz], unlike us, is constantly on the way to faroff and cosmic horizons.

Simcha Shirman (born in Germany, 1947) and Pesi Girsch (born in Germany, 1954) are both obsessed with collective memory and place. Each one has formed a large body of very different and complex imagery, sometimes difficult to follow. In the work of both, the Holocaust appears

67. Maor, 1988.

68. Hadashot, 20.4.1988.

David Rubinger, Farod, 1964, silver print, 38.5×49.6. “A later stage of immigrant absorption. In the early days of the 1950s immigrants were just dumped on hillsides where they were given tents or, in some luckier cases, asbestos huts. Ten years later the government could already allow itself to enter a new stage called, ‘from ship to settlement’. Houses were built prior to the arrival of the newcomers. Disembarking from the ships they were taken to buildings waiting for them. This village, at the time called ‘Farod’, grew into what is now known as the foremost health food spa, ‘Amirim’. In recent photographs some of these little white houses are still visible – serving as storage rooms” (David Rubinger, copyright Yedioth Aharonoth)