Henry van de Velde: entrance portal of the Nietzsche-Archiv

Henry van de Velde: entrance portal of the Nietzsche-Archiv

With contributions by Alexandra Bauer, Helmut Heit, Katrin Junge, Jonah Martensen, Franziska Rieland, Christoph Schmälzle, Corinna Schubert and Sabine Walter

Nietzsche-Archiv with portal by Henry van de Velde

Nietzsche-Archiv with portal by Henry van de Velde

The Nietzsche-Archiv is situated to the south-west of Weimar on an elevation charmingly named Silberblick (lit. ‘silver view’). From here, it commands views of both Weimar, the seat of German Classicism (fig. 1), and the iconic “Bell Tower” of the Buchenwald Memorial on the Ettersberg to the north-west. The Nietzsche-Archiv can therefore be said to occupy one corner of a historically and symbolically charged topological triangle. Surrounded by lush greenery, tall trees and evergreens, the villa stands in an attractive residential neighbourhood with some very fine examples of Jugendstil architecture dating from the 1890s. The two-storey brick building built by district chief August Meisezahl in 1889/90 was grandly named Villa Silberblick, although at the time it was more like a large detached house than a villa.

A wrought-iron gate on Humboldtstraße opens onto the driveway leading up to the gravel forecourt in front of the Nietzsche-Archiv. The gate and gateposts are not original; they were added in the 1980s, emulating the style of the Belgian art reformer Henry van de Velde (figs. 2 and 3). The gravel forecourt is sufficiently large

for the impressive vestibule and portal to make an impact on anyone approaching it. This porch, which was built onto the east facade in 1903, was designed by Van de Velde himself, who retained the colour scheme of the red brick walls and pale sandstone reveals. The tall, solid-oak double door, which as in a temple can be opened only from within, instantly catches the eye. Especially striking are the brass fittings, whose sweeping organic lines flow into an angular spiral motif, which Van de Velde also used for his cutlery and lamp designs (fig. 4). Below the fanlight, the doors rise up into an arch, whose downward slant is taken up by the windows on either side. The portal is flanked by strips of red sandstone. These decorative elements are abstracted pilasters and capitals whose fluting is maintained in the wooden doors and window frames.

A slab of red sandstone bearing the name NIETZSCHE-ARCHIV in Antiqua script identifies what was once a private residence as a public place and serves as a label literally set in stone. The original nameplate was removed in 1956, nine years after the archive closed, but was reconstructed for its reopening in 1990. The wroughtiron railing on the roof of the vestibule echoes and inverts the arch motif, its vibrant linearity making for a pleasing contrast with the geometric shapes dominating the portal.

To accommodate the sloping terrain, the north side facing the city has a somewhat higher basement with an arcaded avant-corps to support a twostorey, now glazed-in veranda (fig. 5).

The transom windows with their sandstone and beige plaster reveals lend rhythm to the plain brick facade, and only the ground floor’s easternmost window breaks with the symmetry. With its unusual dimensions and its mullions, it indicates an interior design diverging from the building’s historicist architecture. The west side of the villa that faces onto the garden has a bricked-up window in the middle that again hints at the remodelling of the room within (fig. 6). That this garden facade was considered less important for the overall impression is evident from the retrofitted window that lacks a lintel and the ill-fitting extension built onto its southern end. Instead of brick, this side of the building was rendered in mud-coloured plaster with a grid of green wooden battens. Moreover, a simple back entrance with coal scuttles disrupts the semi-basement. The south side of the villa facing uphill is nowadays comparatively close to the wall of the Nietzsche Memorial

Hall erected in 1936 on what was then part of the property. As with the west facade, the original symmetry of the south side of the building was impaired by the later extension (fig. 7). Iron bars on the ground-floor windows prevent unlawful entry, while the upper storey has the same wide transom windows as the portal attached to the front of the villa.

The Nietzsche-Archiv is entered through a porch with red sandstone steps and wood-panelled walls that are painted brown (fig. 8). The steps lead up to a glazed swing door, whose fanlight has a remarkable lamp built into it. This rhomboid lantern made of plate glass and brass rods was originally a petroleum lamp and was electrified only in 1930. Its light amplifies the daylight streaming in through the fanlight above the front door and illuminates the vestibule beyond. The glass doors’ brass fittings with their three concentric arches are just as much an eye-catcher as those on the outside of the solid-oak double door. Having once arrived at a pleasing design, Van de Velde would frequently reuse it for all sorts of projects, which is why both the wall lamp and the door handle models are to be found not only in the Nietzsche-Archiv, but also in the Trebschen Sanatorium in the now Polish town of Trzebiechów.

After crossing the porch and entering the vestibule, the visitor cannot help but be impressed by Van de Velde’s Ge samtkunstwerk, whose many colours and shapes are perfectly harmonised in a “unity of style” such as Nietzsche himself had propagated. This interior space, which is through-composed down to the tiniest detail, makes for an elegant connection between the original house and the vestibule built onto it. Its simplicity and finesse generate just the kind of solemn and dignified atmosphere in which

(1844 Röcken – 1900 Weimar)

Born on the same day as the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV, and named after him, Nietzsche grew up in a pious Protestant household in the village of Röcken near Leipzig, where his father was a pastor. When the latter died after a severe illness in 1849, the family moved to nearby Naumburg, where the semi-orphaned Nietzsche was awarded a scholarship, enabling him to receive an excellent education at the Pforta school. At the age of only twentyfour and before having finished his doctoral dissertation, he was appointed Professor of Classical Philology at the University of Basel. As meritorious as his works in this field were, his enthusiasm for the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer and the music of Richard Wagner prompted him to realign and change over to philosophy. His first philosophical treatises were written in support of Wagner’s ambition to reform German culture. In 1878, however, Nietzsche broke with Wagner and turned his back on the Bayreuth project. After relinquishing his professorship for health reasons in 1879, he lived the life of an itinerant philosopher with no fixed abode. It was in Italy, Switzerland and Germany that he wrote his books on moral, religious, linguistic and cultural criticism for which he is best known today, though they did not attract much attention among his contemporaries. It was only after his mental breakdown in Turin in January 1889 that he was recognised as one of the most influential thinkers of the day. By the time of his death in Weimar on 25 August 1900, he was world-famous. People all over the world are still fascinated and provoked by his writings to this day. HH

Friedrich Nietzsche spent only the last three years of his life at the Villa Silberblick in Weimar, and by then his dementia was so far advanced that he was utterly dependent on the care of others. He neither registered that there was now an archive bearing his name, nor could he have any say in the interiors and furnishings of his new home, still less work at the desk in his study. The NietzscheArchiv as a cultural and academic institution is not his work, but rather the creation of his sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche. That such an institution was possible at all, however, was thanks only to the texts of unparalleled significance that Nietzsche wrote. The core of the Nietzsche-Archiv is thus Nietzsche’s philosophy.

Born in the village of Röcken in Prussia on 15 October 1844, Friedrich Nietzsche was the son of a pastor and a pastor’s daughter, who spent his childhood and youth firmly rooted in Germany’s

Protestant heartland (figs. 1, 2, 3). His extended family included some genuine natives of Weimar: his grandmother Erdmuthe Krause (1778

1856), for example, who lived there at the height of German Classicism, and her older brother Johann Friedrich Krause (1770 –1820), who as General Superintendent of Weimar’s parish church of St Peter and St Paul held a position that Johann Gottfried Herder had once held. On Boxing Day in 1873, Nietzsche watched a performance of Richard Wagner’s Lohengrin at Weimar’s Grand Ducal Court Theatre, an opera that had premiered in Weimar in 1850 under the baton of Franz Liszt. After meeting Richard and Cosima Wagner in 1868, Nietzsche became a close friend of theirs, as well as corresponding with Cosima’s father Liszt from time to time. As to the other great heroes of Weimar Classicism, however, Nietzsche tended to be dismissive. Wieland had “nothing new” to say and Herder was “dated”, he said, while he disliked Schiller with all his patriotic enthusiasts and followers for being the “moral trumpeter of Säckingen”. Only Goethe did he deem worthy of his unbroken respect. That Nietzsche himself would one day take his place in the rollcall of Weimar’s notabilities was unimaginable at that stage. His rise to a philosophical phenomenon of world-wide magnitude essentially took place in three stages: a philological, a Wagnerian and a philosophical. After the sudden death of his father Carl Ludwig Nietzsche in 1849, his widowed mother Franziska moved to Naumburg (Saale), taking Friedrich and his younger sister Elisabeth, two aunts, her mother-in-law and a servant with her. In Naumburg the young Friedrich attended the Domgymnasium, and thanks to a scholarship awarded to him as the child of a deceased public servant was able to become a boarder at the prestigious Pforta School. It was there that Nietzsche’s remarkable gift for ancient languages became apparent. He left school as the best of his year and in the winter semester 1864/65 began the study of

The story of Henry van de Velde’s design of the Nietzsche-Archiv in Weimar as a Gesamtkunstwerk begins in 1897 with Count Harry Kessler’s dismay at the stylistic eclecticism of the Villa Silberblick (fig. 1). Kessler, a cosmopolitan connoisseur of European avant-garde art, had made the acquaintance of Elisabeth FörsterNietzsche in Naumburg two years earlier, when they met to discuss the publication of Nietzsche’s compositions in the art magazine PAN . His advice had since become indispensable to her, and he was the first guest to be invited to the archive’s new premises in Weimar. Describing it later in his diary, he compared the disappointingly banallooking setting chosen to house his great idol with the stylishly staged Goethe Residence on the Frauenplan that he had likewise just visited: “In the reception room on the ground floor there is red velvet furniture and framed family photographs mixed with mementos from Paraguay, lace veils, needlework, Indian majolica. Everything is displayed above all for the interest of its content and not to evoke an aesthetic impression, like the home of a prominent university professor or civil servant.” Since Förster-Nietzsche had confidence in his sense of style, Kessler suggested that she commission the pioneer art reformer Henry van de Velde – then barely known in Germany – with the graphic design of the planned luxury edition of Also sprach Zarathustra (Thus Spoke Zarathustra). To give her a foretaste of Van de Velde’s modern aesthetic vision and forge a personal bond between them, Kessler invited

her to meet up with Van de Velde and his wife personally in Berlin in January 1901, where they visited Van de Velde’s lectures as well as soirées and exhibitions (fig. 2).

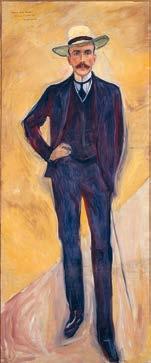

The Belgian artist’s own business named Henry-van-de-Velde-GmbH had recently been forced into liquidation, prompting him to leave Brussels and move to the booming Prussian metropolis to design interior furnishings for the Hohenzollern-Kunstgewerbehaus and promote his concept of “rational form” (fig. 3). Animated by Kessler’s enthusiasm and sensing an affinity between Van de Velde’s aims as a designer and her brother’s views and preferences, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche also recommended the Belgian artist for an employment in Weimar, where he would be able to dedicate himself to the development of modern, low-cost objects of everyday use. It was in August 1901 at the memorial event held to mark the first anniversary of Nietzsche’s death that Kessler, Van de Velde and Förster-Nietzsche first floated their vision of a “New Weimar” as a meeting place for Europe’s avant-garde with the NietzscheArchiv at its centre. The “New Weimar” movement gained momentum in the spring of 1902 when almost simultaneously with Van de Velde’s commencement of duties the impressionistic painter Hans Olde was appointed director of the Grand Ducal Saxon Art School in Weimar. Olde had attracted notice in 1899 with some sensitively done portraits of Nietzsche on his sickbed, and Förster-Nietzsche held him to be the artist “best suited to work alongside Van de Velde”. Emboldened by his success, Kessler began to dream of “a kind of supreme directorate of all artistic endeavours in the grand duchy”, and in 1903 accepted the honorary position of director of the Grand Ducal Museum for Arts and Crafts, for the

sake of which he dispersed the existing Permanent Art Exhibition (now the Kunsthalle Harry Graf Kessler). Curated by Kessler, a series of barnstorming exhibitions of European modernism opened in Weimar in the spring of 1903 (fig. 4).

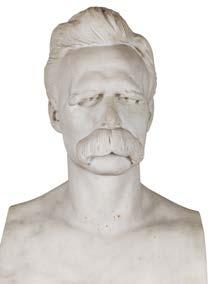

Simultaneously with the arrivals of Van de Velde, Olde and Kessler as representatives of the “New Weimar” project, the plans to lend the Nietzsche-Archiv a more modern look were becoming ever more concrete. Förster-Nietzsche acquired the property from her cousin Adalbert Oehler in April 1902 and entrusted the – originally small-scale – remodelling of the bel étage to Van de Velde. Her choice of a known stylistic reformer signalled her intention to transform an otherwise bourgeois-looking home into the site of the Nietzsche cult. In his memoirs, Van de Velde recalled feeling as if he were living “in the philosopher’s spirit” throughout the planning phase. The reverence for Nietzsche of all those involved became apparent in the remodelling of the interior as a sacred space, a “consecrated temple” with a “sacred and monumental treasury”, even if the private apartments upstairs were left unchanged, on grounds of both piety and cost. Kessler likewise made his contribution to the memorial by commissioning Max Klinger with a marble herm bearing a portrait head of Friedrich Nietzsche to be set up in the “hall”, as the library was now called (fig. 5).

Van de Velde designed a stylish architecture that accorded with his understanding of Nietzsche’s philosophy as well as with the ambitions of Nietzsche’s sister, who intended to create a Nietzschean equivalent to the Villa Wahnfried in Bayreuth and with it a space that might be used for both social functions and private tea parties. Indeed, the new beginning signalled by the choice of Van de Velde was not just aesthetic and social; it was also one of content. From now on, every detail right down to the door handles was to convey modernity (fig. 6). The resulting Gesamtkunstwerk with its aspirations to a stylistic unity defined by the artist also meant that FörsterNietzsche had to dispense with many personal items. Confronted with her “horror” at these radical changes, Kessler assured her “that the renewal symbolises, as it were, the stripping away of all things random and banal from your brother’s person and surroundings and the forming of the imperative and the eternal living within him”. True to Nietzsche’s spirit, the archive was to become culturally productive and to bring forth “people of the utmost inner and outer perfection”.

Ever since the late 1880s, it had been Van de Velde’s mission to have a hand in the shaping of modernity. After training as a painter (fig. 7), he suffered a crisis of creativity during which he engaged with various strands of social critique. In addition to socialism and anarchism, these included the aesthetic innovations of the English Arts and Crafts movement inspired by John Ruskin and William Morris, and the years 1886 – 90 had seen him studying Nietzsche’s visions of modern life as well. Absorbed by the idea of designing stylish everyday objects that would modernise the ambient living, he abandoned painting and began designing furniture, eventually shifting to the