Date:

Date:

Date:

COLLECTIVE MEMORY OF HISTORIC URBAN TRACES, MORPHOLOGY, AND IDENTITY IN URBAN REVITALIZATION

CASE STUDY OF A FORMER JEWISH QUARTER

Vilnius, Lithuania

Site Location

Old Town (Lithuanian: Senamiestis) – Vilnius, Lithuania

Date

March 2017 – September 2017

Phase/Status

Proposal (Master’s Program Final Project)

Architecture, Landscape Design, Urban Design, Urban Development

Typology(s)

Commercial Space, Cultural Space, Heritage Site, Historic City District, Low-Rise, Memorial, Mixed-Use, Public Space

Institution(s)

Brandenburg University of Technology, Cairo University

Tutor(s)

Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Heinz Nagler; Prof. Dr. Dalila Elkerdany, B.Sc., M.Sc.; Dipl.-Ing. Christoph Wessling

Special Thanks to Faculty of Architecture, Vilnius Gediminas Technical University; Lithuanian Jewish Community, Vilnius; Museum of Holocaust Exposition, Vilnius; National Library of Lithuania, Vilnius; Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum, Vilnius; Aistė Galaunytė; Anandit Sachdev; Artūras Čertovas; Indrė Raudoniutė; Martynas Užpelkis; Monika Antanaitytė; Dr. Nabeel M. Elhady, B.Arch., M.Sc. (Cairo University)

Task

Providing a proposal of urban design, development, and policies at the local, district, and city levels respectively for the revitalization of the former Jewish quarter in Vilnius.

Description

Vilnius was known as a significant religious-cultural center of Eastern European Jewry between the 17th and the early-20th centuries due to its large population of Jews. However, during World War II (1939–1945), around 95% of Jews in Vilnius were murdered, resulting in the low amount of Jewish population as well as Jewish cultural and historical significance in Vilnius today. Despite many Jewish historical remains in Vilnius, Jewish cultural significance as an essential part of the city’s history, memory, and identity has been forgotten since then. This project aims to increase awareness of Jewish cultural significance in the former Jewish Quarter area. An urban revitalization strategy in the area is proposed by integrating socio-cultural, economic, and environmental aspects as elements of the collective memory related to historic urban traces, morphology, and identity under the contexts of Jewish cultural and historical significance in Vilnius.

“The memory may be either individual or collective. Collective memory is a series of events collectively remembered by a group of people who share it and involve themselves in shaping it.* The greater the number of the people remembering the event, the more the memory finds a collective feature.”**

Guidelines and Principles

At the city level, the strategy is making the former Jewish Quarter as one of Vilnius’ main attractive touristic destinations to promote cultural and historical aspects of the city. It is implemented through promotions via websites and social media, which are executed by collaborations between the Lithuanian Ministry of Culture, Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum, The Tolerance Center, the Holocaust Exposition Museum, and the Lithuanian Jewish Community.

At the district level, the strategy is organizing annual cultural events as ‘trademark’ events of the Old Town of Vilnius in general and the former Jewish Quarter in particular. It is implemented through an annual culinary festival, an annual mural art festival, and an annual outdoor bazaar at the Vokiečių g. Spinal Pavilion.

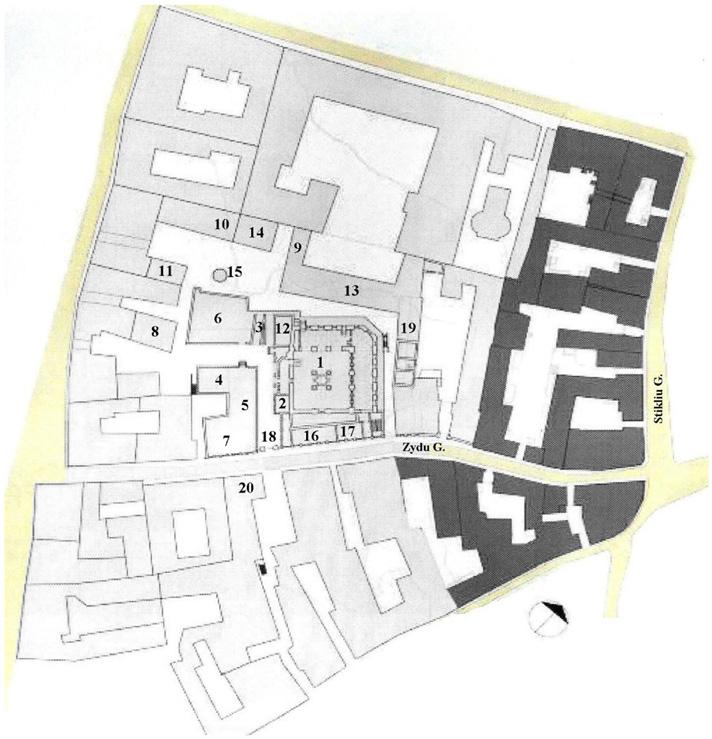

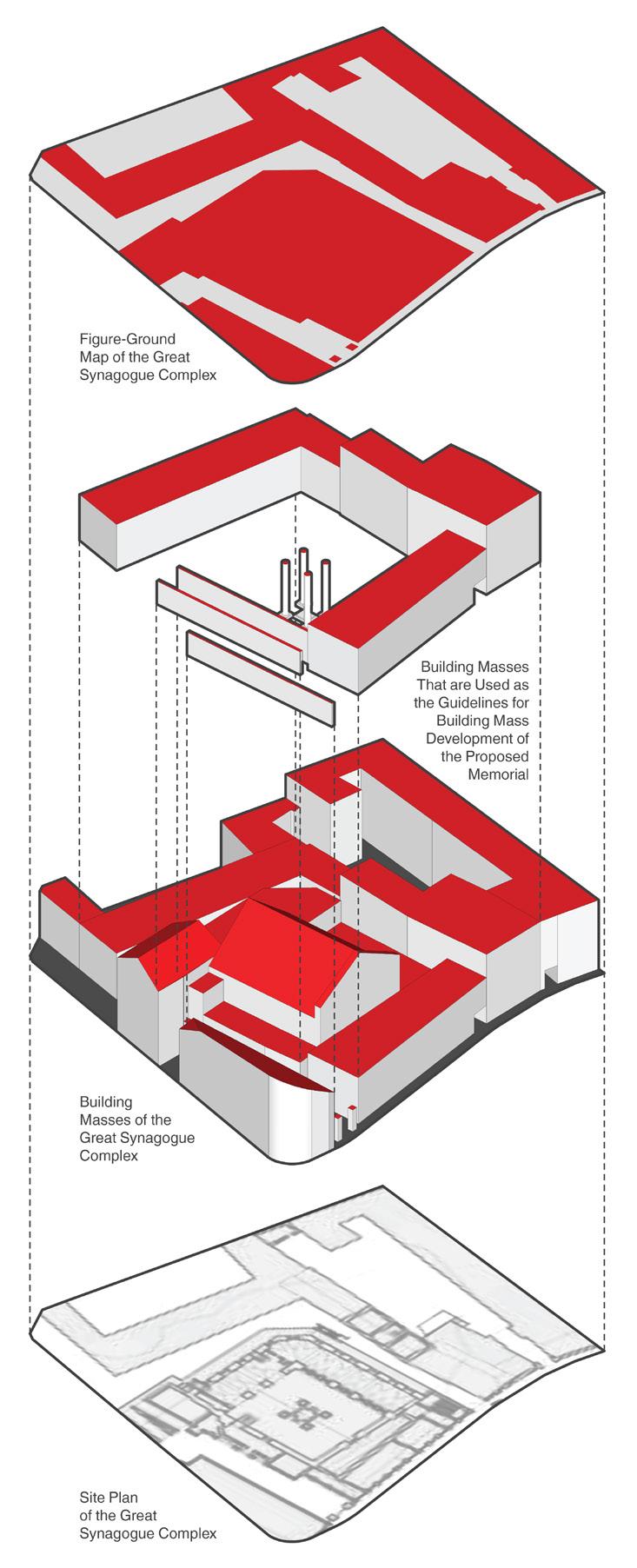

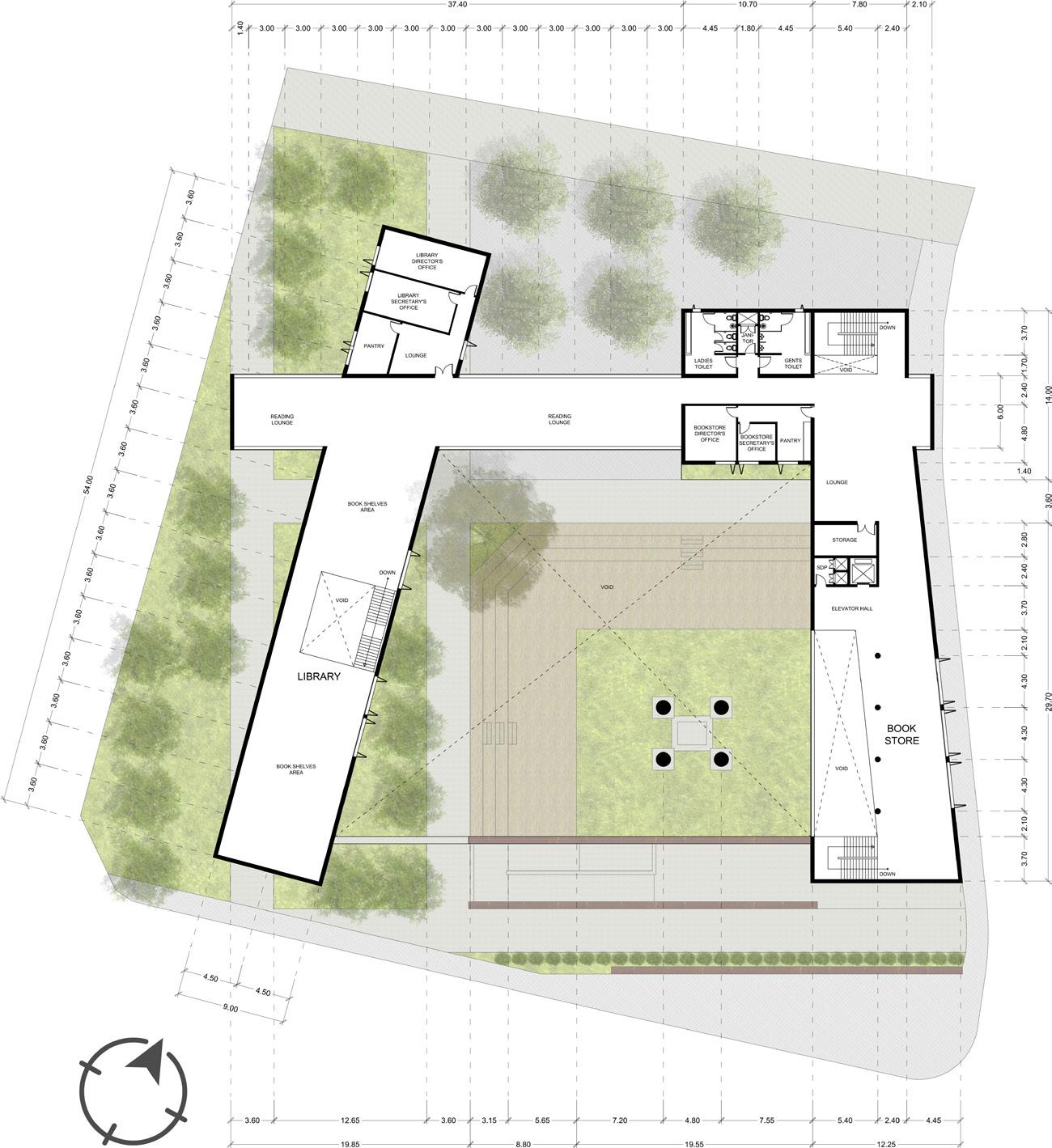

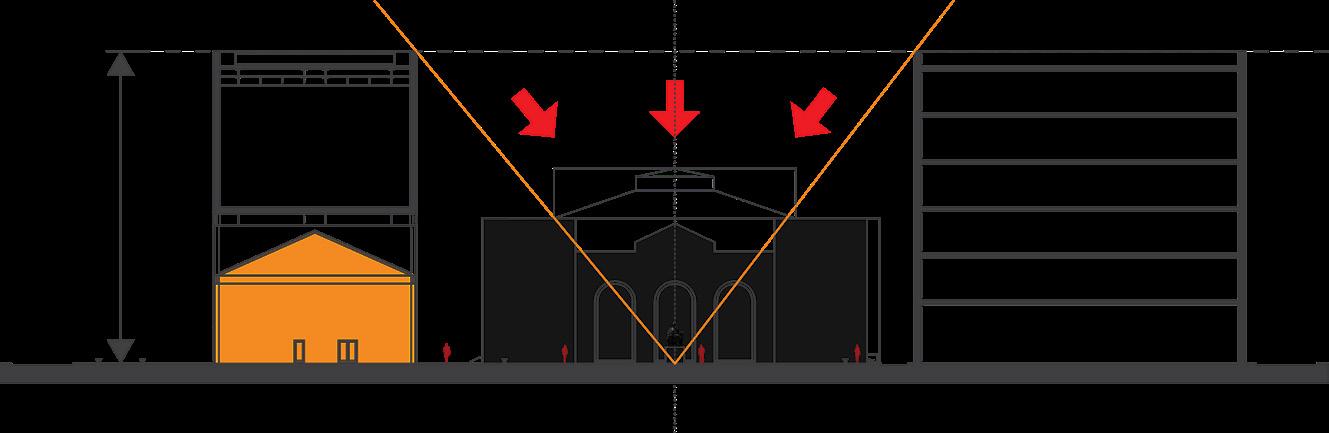

At the local level, the strategy is revitalizing the public spaces and the historic streets as urban reminders based on tangible cultural and historical significance. This strategy is manifested in: 1) the Great Synagogue Memorial, with the outdoor gallery, as the primary element of urban reminders; and 2) Vokiečių g. Spinal Pavilion. The Great Synagogue Memorial and the outdoor gallery commemorate the Great Synagogue of Vilnius as the center of religious-cultural, educational, and communal aspects of the Jewish community in the past. It consists of a library, a book store, a communal space, and a cafe & restaurant.

The Vokiečių g. Spinal Pavilion is a metaphor for Vokiečių g. that was perceived as the ‘backbone’ of the Jewish Quarter in the past, as well as one of the most active commercial areas in the present-day Old Town of Vilnius. It consists of an art gallery & cultural center, restaurants, and several public spaces as activity generators.

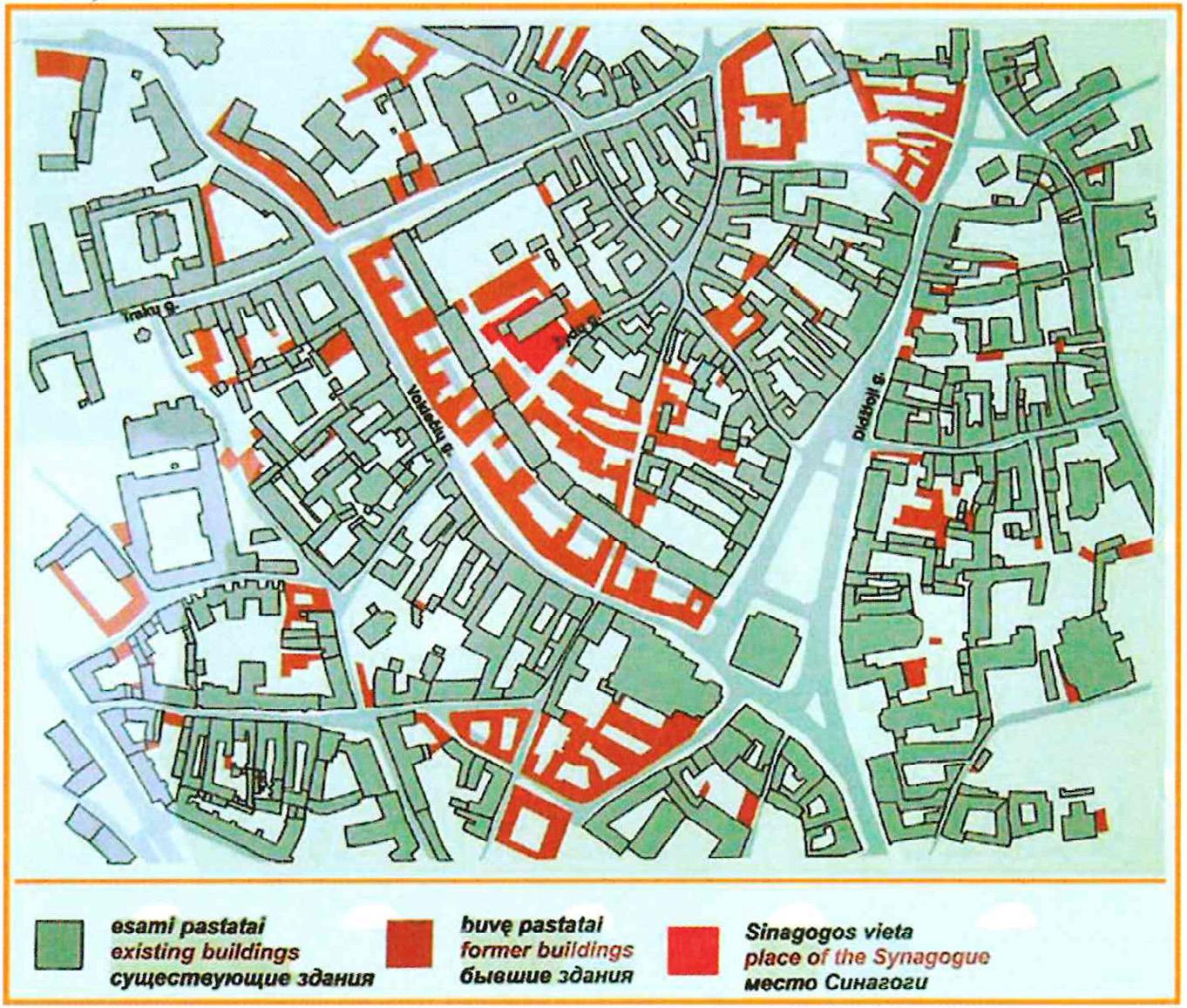

Regulations of Housing for Jewish Residents in Vilnius

In Vokiečių g., Jewish residents were not allowed to live in flats with windows facing the Vokiečių g. The regulation then became stricter in 1648. In 1633, in Žydų g. and Mikalojaus g. Jews were allowed to live on both sides of the streets, as well as in Jatkų (Mėsinių) g., where Jews were allowed to live in the street adjacent to Žydų g. In 1648, in Žydų g., Jatkų (Mėsinių) g., and Šv. Mikalojaus g. Jews were allowed to live only on the sides adjacent to Žydų g. In 1690, Jews were allowed to live and own houses in Žydų g., Jatkų (Mėsinių) g. and some areas in Vokiečių g. Jews live in Trakų g., Didžioji g., and Pilies g. by renting houses owned by Christians. In 1742, Jews were not allowed to live outside the core area of the Jewish Quarter. Jews who were previously living in houses owned by Christians were forced to move to the core area.

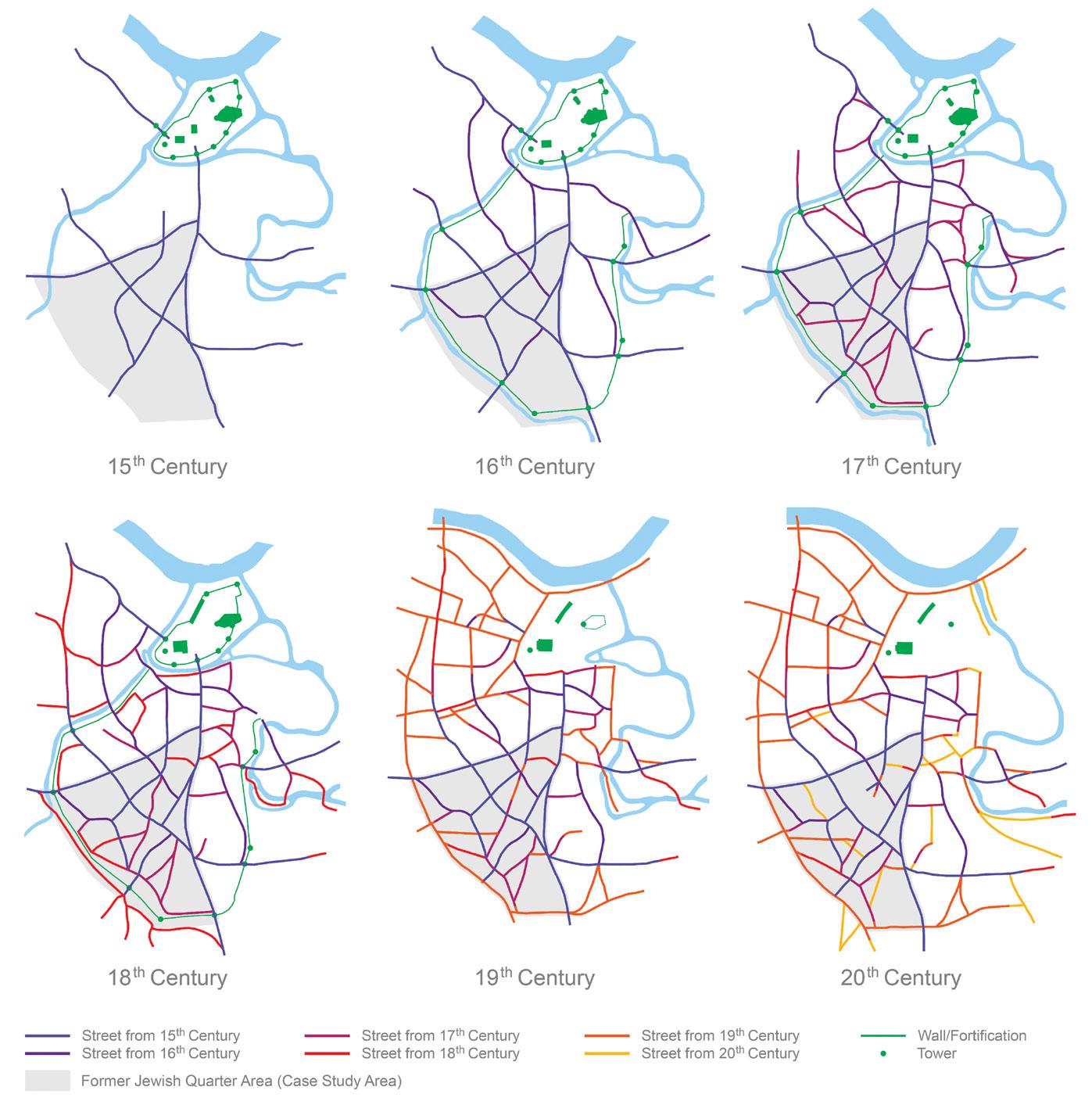

Morphology of the Old Town, Vilnius Between the 15th and the 20th Centuries

Heritages by UNESCO in the Project Area –Source: Developed by author(s) based on a map from http://whc.unesco.org/ [2017].

Monument to the Vilna Gaon: Located on the northern side of the existing primary school, the primary school was built in the Soviet occupation period. – Source: https://www.radzima.org (above); samgrubersjewishartmonuments.blogspot.com/ (below) [2017].

Existing

School: Facing

[2017].

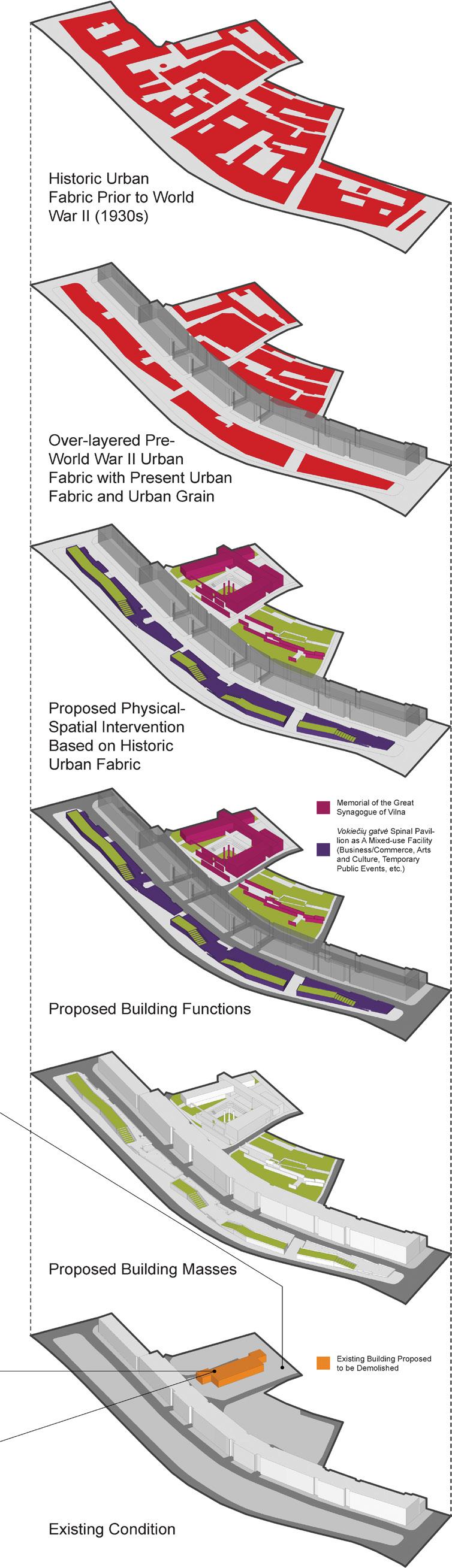

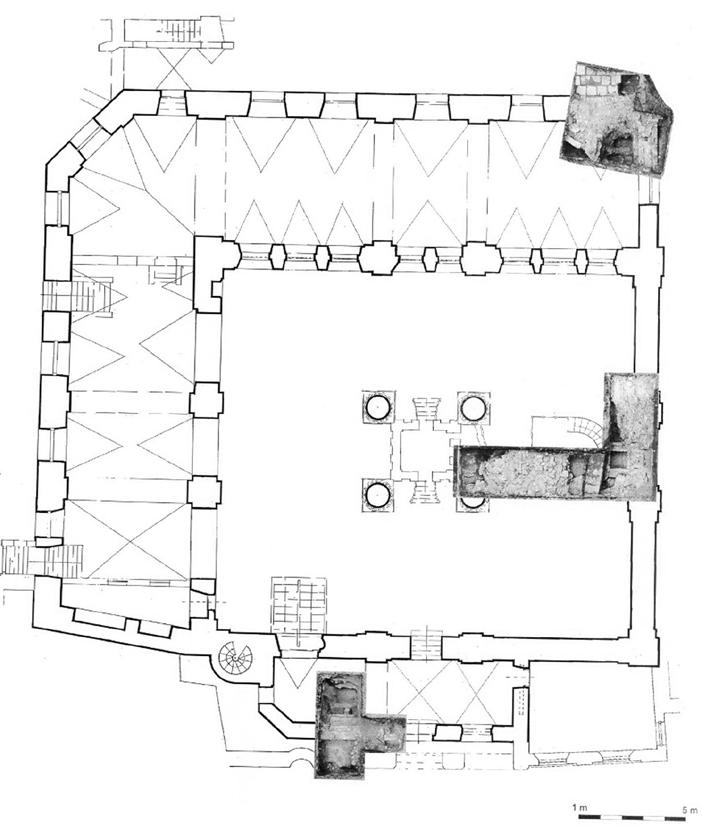

Isometric Diagram of the Specific Urban Design Strategy at the Local Level (the Former Jewish Quarter): Focused on the former site of the Great Synagogue and in the Vokiečių

The Great Synagogue Memorial and the Outdoor Gallery

The courtyard inside the memorial complex is occupied by four massive columns having the exact size of the four main columns of the podium (Hebrew: bimah) in the center of the demolished synagogue. As the sanctuary’s main focal point, it was the spot where the Torah was read and spoken in the synagogue during rituals.

The ground plan of the sunken courtyard is designed in reference to the original floor plan of the Great Synagogue building. At the time of its building (16th century), European ecclesiastical regulations specified that a synagogue could not be built higher than a church. Hence, to obey the law and yet to create the necessary interior height, it was customary to dig a foundation deep enough for the synagogue’s floor level to make it well below the street level. Outside, the synagogue looked to be about three storeys tall. Inside, it soared to over five storeys.

At the outdoor gallery, walls as a landscape element are combined to create a linear path of the exhibition area on the southern side of the Great Synagogue Memorial site. The outdoor gallery displays information about the historical and cultural significance of the Jewish quarter of Vilnius. The ground plan of the outdoor gallery is designed based on the traces of a historic 1930s urban fabric in the exact area where residential buildings lived by Jews. That urban fabric has been completely demolished since the end of World War II. The scattered, unjoined straight walls are composed to create an enigmatic atmosphere at the outdoor gallery and blend landscapes between the display area and the grassy park around it.

Landscape Design of the Park with a Public Sitting Space: Designed as a resting area as well as a communal space, integrated with the outdoor gallery.

Murals on the Spinal Pavilion in Vokiečių Gatvė: The solid walls are a commemorative element toward a discriminative housing regulation in

windows facing the Vokiečių gatvė.

Main Entrance to the Site of the Great Synagogue Memorial Complex Courtyard Inside the Great Synagogue Memorial Complex: Designed as a cultural-educational space with four massive columns

Walls at the Outdoor Gallery

Source:

CORDAHI HOUSE OF CULTURE

ARTS AND CULTURAL CENTER

Alexandria, Egypt

Site Location

Fouad St. (Now: Gamal Abdel Nasser St.), Cordahi Complex and Cinemaplatz – Alexandria, Egypt

Date September 2016 – January 2017

Phase/Status

Proposal (Master’s Program 3rd Semester Project: Architecture in Historic Context)

Category

Typology

Adaptive-Reuse, Community Center, Cultural Space, Heritage Building, Medium-Rise, Mixed-Use, Public Building

Institution(s)

Alexandria University, Brandenburg University of Technology

Tutor(s)

Prof. Dr. Hatem A. El-Tawil

Special Thanks to Dr. Ebtissam Mohamed Farid; Dr. Hebatalla F. Aboulfadl; Prof. Dr. Nevin Gharib; Dr. Zeyad El Sayad

Task

Transforming a complex of historic buildings into an arts and cultural center by using an adaptive-reuse design method.

Description

Located in the historic Fouad St. (Now: Gamal Abdel Nasser St.), the site is occupied by three existing historic buildings: 1) the Alexandria Opera House; 2) the Cordahi building 1 (apartment), and 3) the Cinemaplatz building (former cinema). In this project, the Alexandria Opera House —which is well-preserved and well-maintained— remains unintervened. Thus, the adaptive-reuse design intervention only implicates the Cordahi building 1 and the Cinemaplatz building.

The existing condition of the Cordahi building is deteriorating due to poor maintenance and service, while the Cinemaplatz building is almost fully abandoned in a terrible condition. With the change of the two existing buildings’ typologies into an arts and cultural center typology, the inner structure of the Cordahi building 1 is being transformed to suit the needs and purposes of the mentioned new typology. The main structure of the Cinemaplatz is demolished by only preserving its existing historical facades facing Fouad St. and Al-Naby Danyal St., to be further combined with the new additional building parts. The main challenge that is faced on this adaptive-reuse project is the existence of many archaeological sites and excavations along with historic buildings around the site due to the historic importance of the district —especially in and around the Fouad St.— that has been developed since the Hellenistic period of Alexandria (as early as 331 BC). Therefore, this adaptive-reuse project must ‘obey’ the contexts of its surrounding heritages. This includes the landmark hierarchy of Alexandria Opera House as one of the city's most important active (fully operating/functioning) historic landmarks today.

The Cordahi complex, once owned by George Cordahi, was built between 1918 and 1921 on the location where the old Zizinia Theatre used to exist. Located in Fouad St., adjacent to the Cinemaplatz, the whole complex was designed by a French architect, Georges Parcq (1874–1939). The Cordahi complex consists of Alexandria Opera House (also known as Sayyid Darwish Theatre and formerly Mohamed Aly Theatre) alongside two apartment buildings (Cordahi Building 1 and 2). Fouad St., named after King Fouad (1868–1936), played a significant role in the planning of Alexandria. After the 1952 revolt, the street’s name was changed to El Horreya St., then to Gamal Abdel Nasser St. after the late president’s death (1970). However, Alexandrians nowadays still address it as Fouad St., a European-style street which holds a great deal of the city’s history with a number of surviving notable landmarks.

Two Images at the Bottom of the Next Page

Left: Human’s-Eye View Perspective of the Cinemaplatz Building and the Cordahi Buildings Taken from Fouad Street (1943) –Source: https://14weeksworthofsocks.com/ (Paula Sillars) [2018].

Right: Human’s-Eye View Perspective of the Cinemaplatz Building and the Cordahi Buildings Taken from Fouad Street (Existing Situation, 2016)

Human’s-Eye View Perspective of the Cinemaplatz Building and the Cordahi Building 1 Taken from Fouad Street (Proposed Adaptive-Reuse Design)

Exsiting Block Plan – Source: Developed by author(s) based on Google Earth [2017].

Location of the Site in the City of Alexandria – Source: Developed by author(s) based on Google Earth [2017].

The Site in One of the World’s Oldest Streets

Guidelines and Principles

This adaptive-reuse design enhances the hierarchy of the Alexandria Opera House as a heritage with the highest cultural and historical significance on the site. This aim is achieved by redefining the plaza's solid-void composition (horizontally and vertically) to generate a symmetrical-minded physical-spatial quality in responding to the symmetrical front facade of the opera house. On horizontal solid-void composition, the insignificant existing additional mass behind the Cordahi building 1 is demolished. On vertical solid-void composition, the new building mass above the former Cinemaplatz main hall is levelling its height to the Cordahi building 2. A commemorative steel structure imitating the exact size of the demolished Cinema-

is also added as an urban reminder.

Concept and Development

In the adaptive-reuse project, distinguishing between the old (existing) part and the new part of the building is essential, most notably when the old part is historical. In this project, this distinction issue is tackled by the use of contrasting colors and textures on the materials of building exteriors. The color pearl white on fine material textures is used on the whole exterior parts of the Cordahi Building 1 as well as on the preserved part of the Cinemaplatz building. On the other hand, darker colors (grey and dark grey) on robust material textures are gained through ‘undressed’ concrete and stone cladding on the exterior walls of the new parts of the buildings.

The color of pearl white on the old parts of the buildings is carried by the intention to match two other historic public arts and cultural buildings in Fouad St.: Mohamed Ali Club (Alexandria Creativity Center) and Villa Bassili (Alexandria National Museum), which their exterior walls are also painted in white.

The continuity of public space between the plaza in front of the Alexandria Opera House and the outdoor performance stage is carried out for the improvement of urban space quality on the site and its surrounding areas. This improvement is achieved through a holistic strategy of integrative urban space by considering the solid-void composition, the circulation axis, and the view axis. Moreover, the strategy is also based on commemorative elements of the demolished Cinemaplatz building.

AMBAVASTU

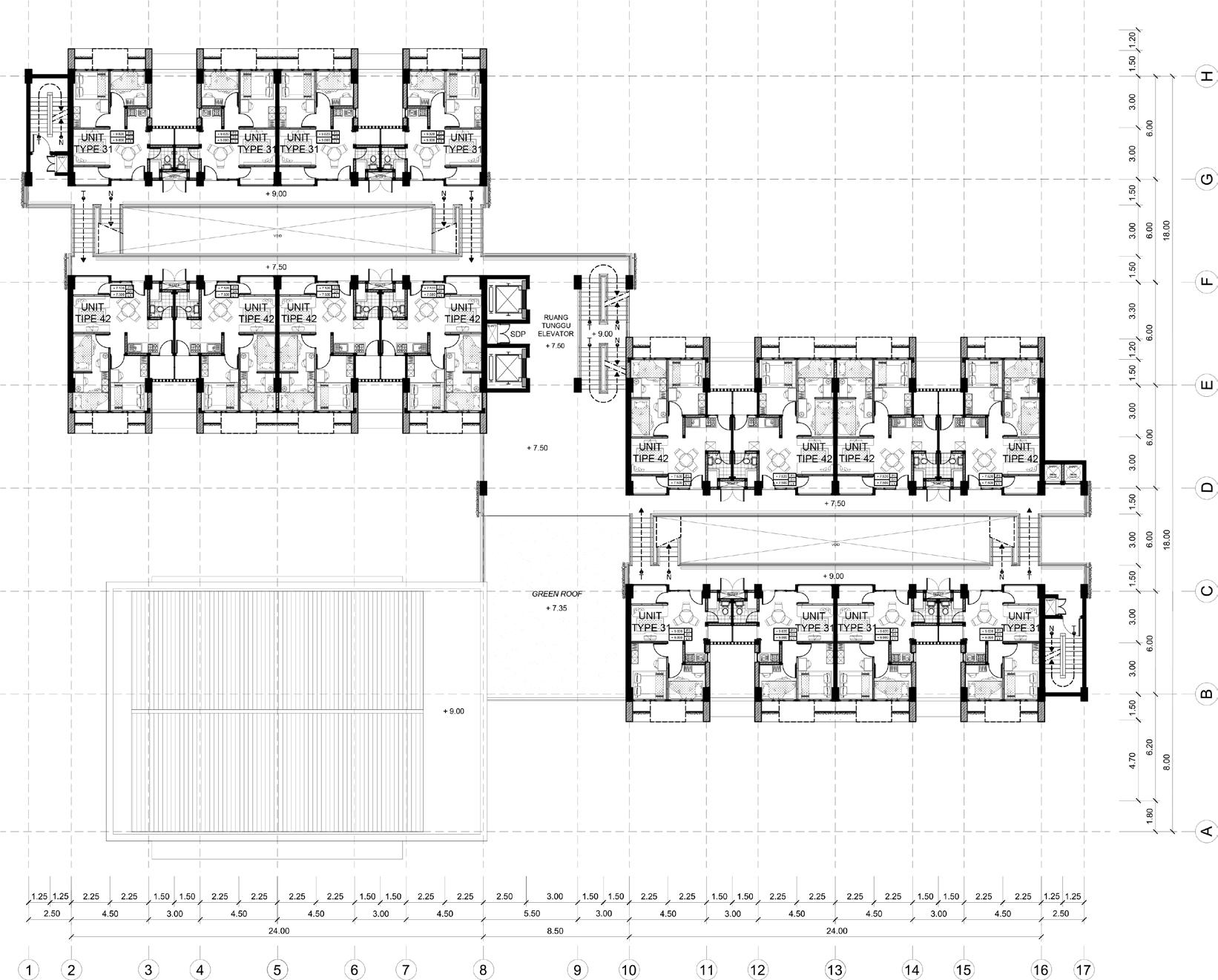

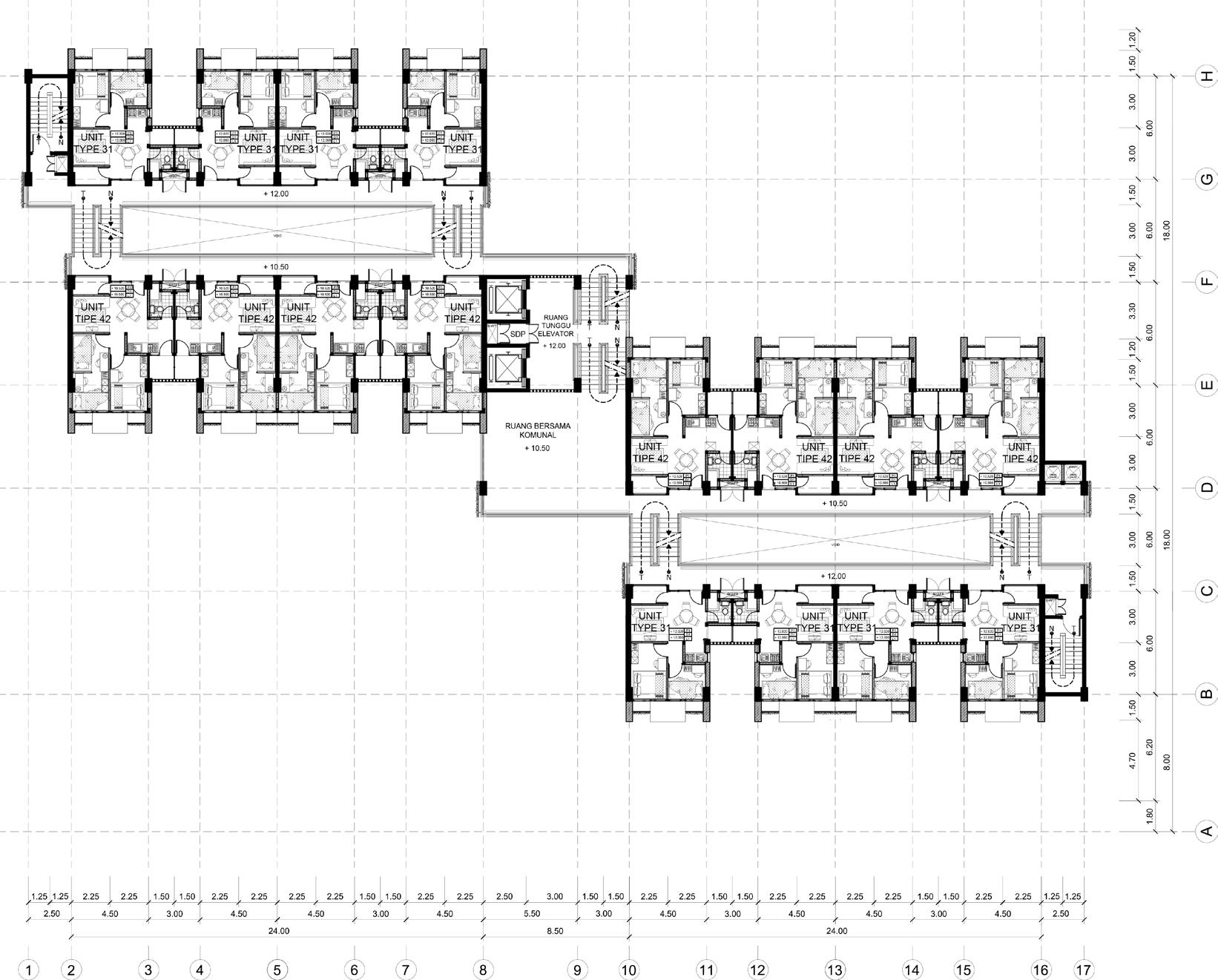

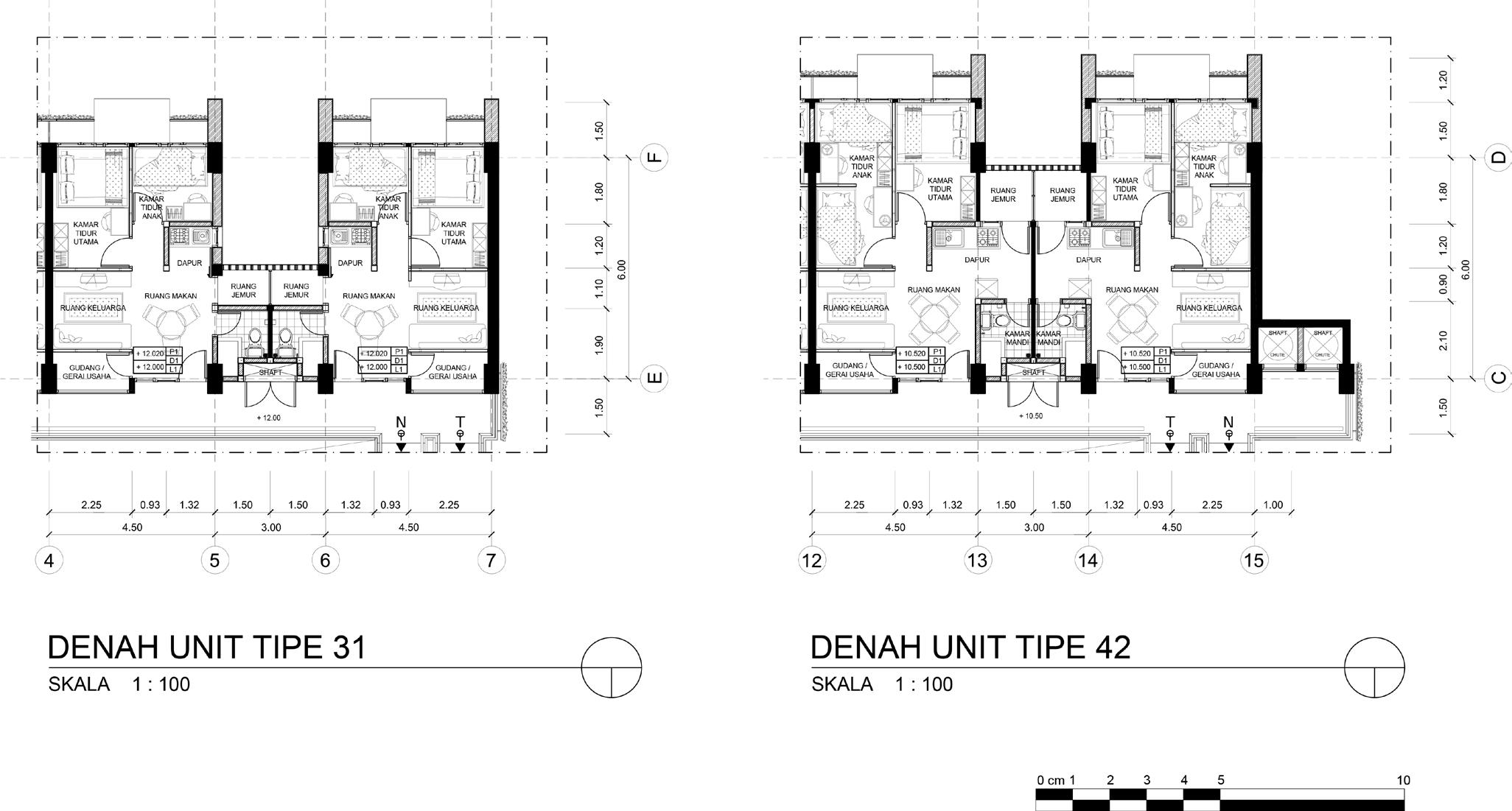

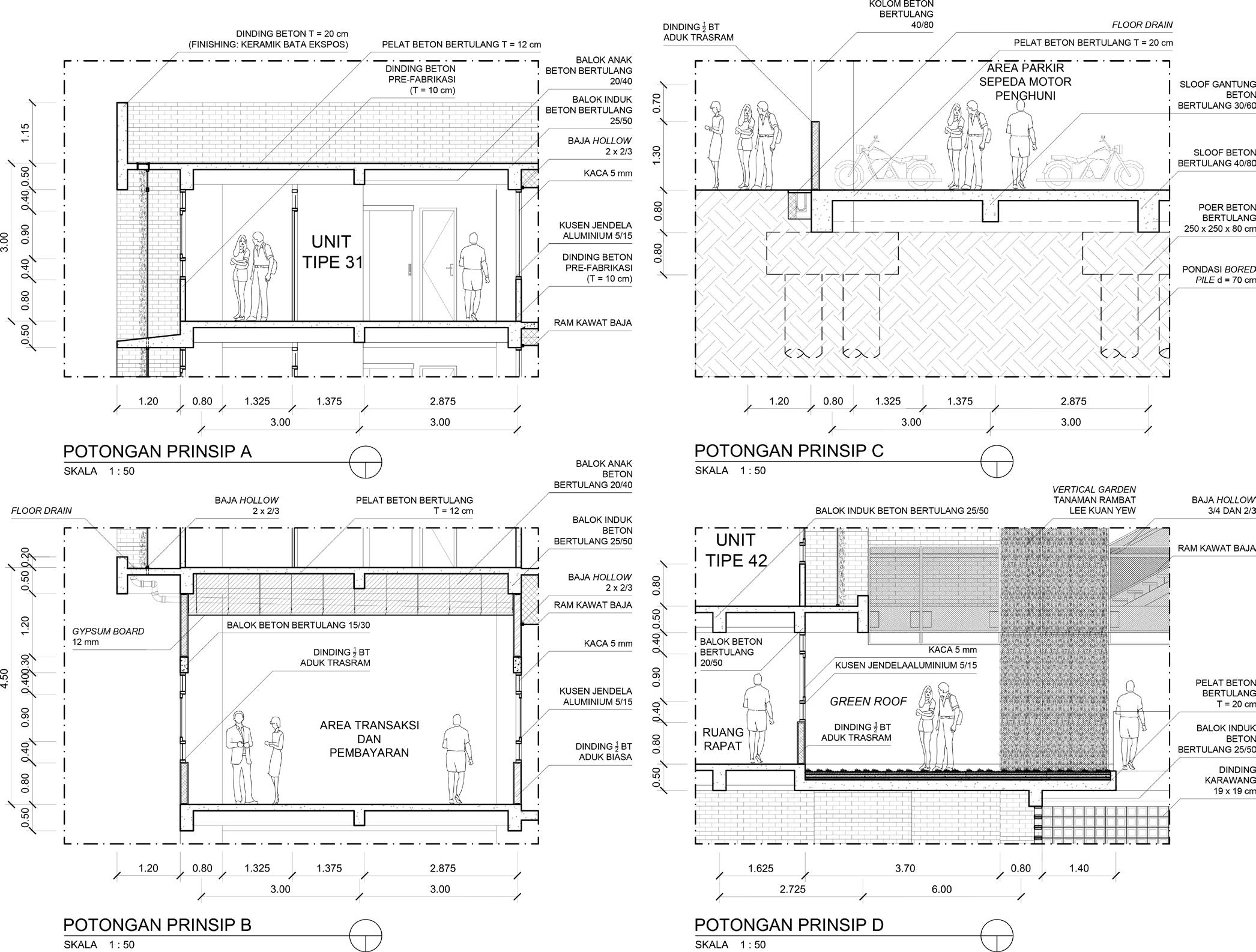

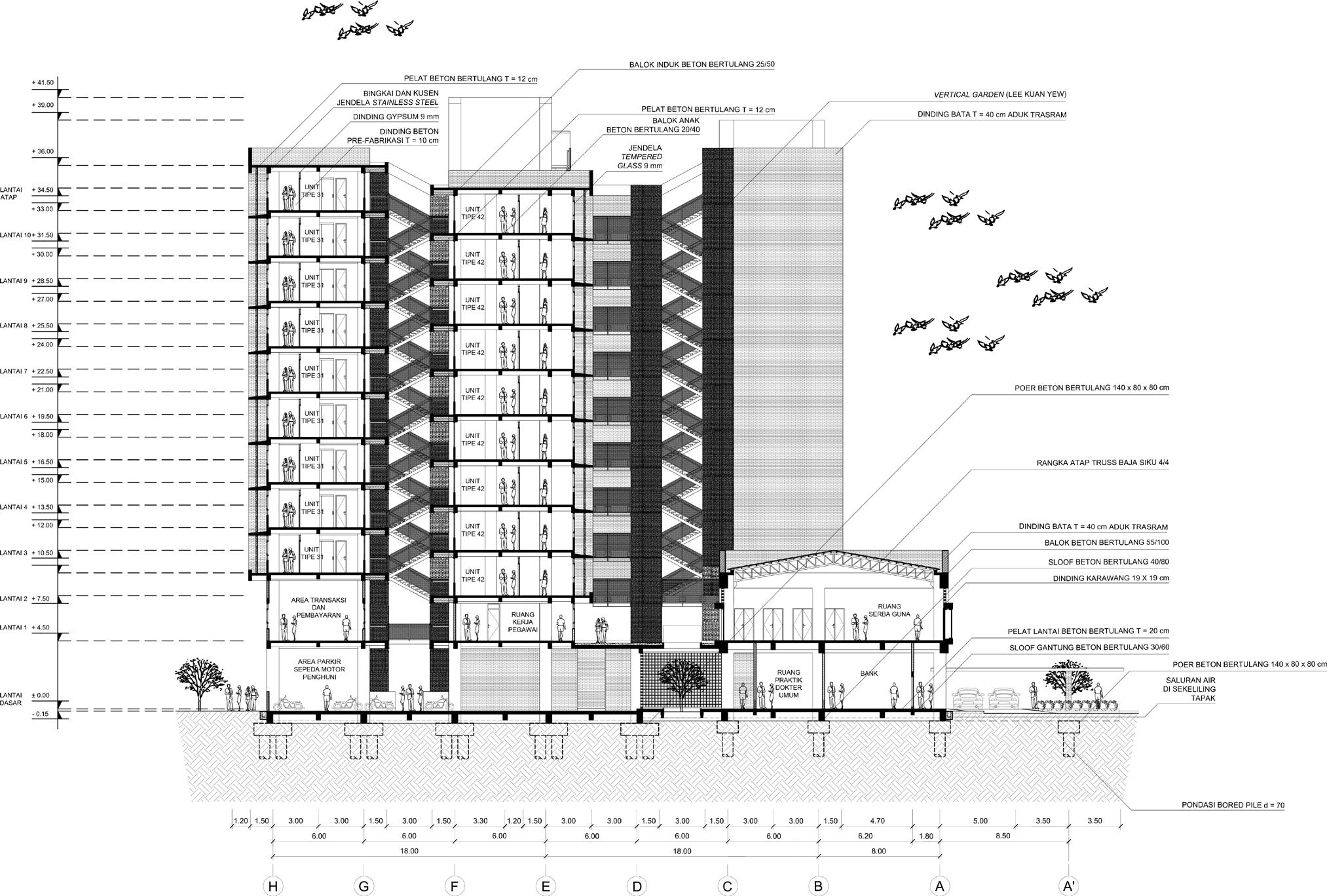

LOW-COST SOCIAL HOUSING

Bandung, Indonesia

Site Location

Jln. P. H. Hasan Mustofa, Kel. Sukapada, Kec. Cibeunying Kidul – Bandung, Indonesia

Date

January 2014 – May 2014

Phase/Status

Proposal (Bachelor’s Program Final Project);

Nominee of the 23rd Architecture Final Project Awards –

Parahyangan Catholic University

Category

Individual Project

Scale

Typology

Apartment, Communal Space, Low-Cost Housing, MediumRise, Social Housing, Residential, Urban Housing

Institution(s)

Parahyangan Catholic University

Tutor(s)

Dr. Anindhita N. Sunartio, S.T., M.T.

Special Thanks to Antonius Richard Rusli, Canical Mey Pratama, Christian Hansen Kartjito, Teguh Risnandar Utama

Task

Designing an affordable public housing for lower middle-class people who settle in an urban area.

Description

Cibeunying Kidul district is one of the strategic urban industrial districts in Bandung, Indonesia. The district has many factories and offices for various industries that support the economic and trading aspects of other districts in the city. Therefore, among the local population, the district is occupied by many settlers from other districts and cities who reside as workers in the previously mentioned sector.

Consequently, there are many apartments and lodging houses (Indonesian: indekos) in the settlement areas of Cibeunying Kidul district. They provide residencies for workers from other places outside the district. Socially, the majority of those workers are classified as lower-middle class people who get employed at the factories and the offices inside and around the district. Hence, they can only afford to rent low-quality yet cheap (low-cost) apartments and lodging houses to settle in the district.

While this social phenomenon is prominently reflected by the workers’ poor urban living conditions in poorly maintained apartments and lodging houses, many of these residencies are located around Jln. P. H. Hasan Mustofa is the primary strategic road connecting several factories and offices inside and around the Cibeunying Kidul district. This project aims to create good quality, affordable (low-cost) social housing, targeted to be rented and lived primarily by the lower middle-class workers (along with their families) who work at the factories and the offices inside and around the Cibeunying Kidul district.

Concept and Development

As mentioned earlier, the lack of properly designed public housing in Indonesia is one of several important national issues that this project needs to tackle. However, by “properly designed,” the term is not just being interpreted in an aesthetic sense but further in functional and social senses by ‘humanizing’ people. Since Indonesians (significantly lower-middle class people) tend to be familiar with collectivist cultures and values on a daily basis, that interpretation is manifested through generating a good atmosphere of

social interaction among the residents. Thus, this manifestation is achieved by providing public and communal spaces as social activity generators inside and outside the building. The typical storey levels are also split in half storey each. Separated by a long void for natural lighting and ventilation, each typical storey circulation space is interconnected to its other storeys above and below. This space composition is not just creating a dynamic visual and physical-spatial experience inside the building but is also enhancing the quality and the quantity of social interaction possibilities between the residents through social/communal-minded interior spaces.

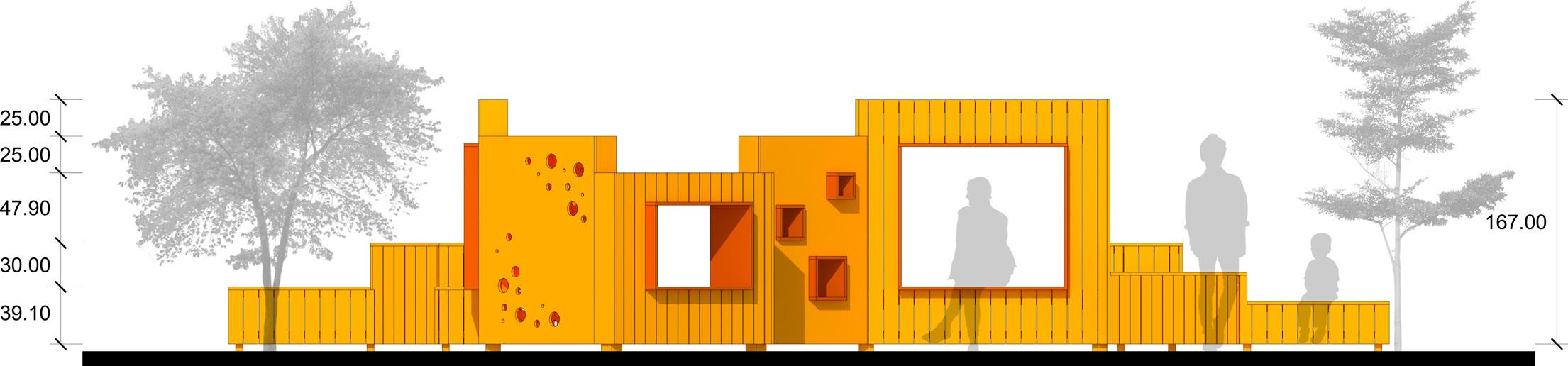

THE WALL

INTERACTIVE PLAYGROUND

Vilnius, Lithuania

Site Location

Architektų g. 85, Lazdynų – Vilnius, Lithuania

Date

1–14 September 2016

Phase/Status

Built

Category

Group Project – Personal Contribution: Created the design concept, 3D-model, and construction drawings; involved during the construction process together with other team members along with kids/students and teachers.

Project Team

Artūras Čertovas, Dewobroto Adhiwignyo, Gabija Rutkūnaitė, Gabrielė Liucija Ošikaitė, Goda Žukaitė, Greta Čerškutė, Kazimieras Kasteckas

Scale Extra Small

Type

Other (Design & Build Workshop)

Typology

Child’s Playground, Playing Facility, School Playground, Wooden Structure and Construction

Institution(s)

Baladilab, Vilnius Gediminas Technical University, Vilniaus Palaimintojo Teofiliaus Matulionio Gimnazija (Then: Vilniaus „Versmės“ Katalikiškoji Gimnazija), German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD)

Tutor(s)

Barbara Pampe, Carla Schwarz, Leonie Weber, Melanie Miglė Kundrot, Vittoria Capresi

Special Thanks to

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Liutauras Nekrošius (Faculty of Architecture, VGTU); Edita Riaubienė, B.Sc., M.Sc., Ph.D. (Faculty of Architecture, VGTU); Indrė Ruseckaitė, B.Sc., M.Sc., Ph.D. (Faculty of Architecture, VGTU); Aistė Galaunytė, B.Sc., M.Sc. (Faculty of Architecture, VGTU); Mgr. Violeta Ališauskienė (Vilniaus „Versmės“ Katalikiškoji Gimnazija); Katharina Wittke

Task

Designing and building a new playground in a participatory process together with kids/students & their parents and teachers of the Vilniaus „Versmės“ Katalikiškoji Gimnazija, Vilnius.

Description

The project aims to create friendly, motivating, and inspiring playgrounds in the schoolyard. The workshop participants from Lithuania & Germany work together with kids/students & their parents and teachers to improve the quality of the schools’ playground by designing and building playing elements.

The program has two aims: 1) giving participants a possibility to develop their soft skills by working in a cross-cultural group to experience participatory planning processes as well as to realize their own designs; and 2) by involving kids/students & their parents and teachers in the creative process from the design phase to the construction phase, the participants get a new way in understanding their surroundings and developing responsibility to initialize further similar activities.

Brainstorming with Kids/Students

Workshop participants are assisting and conversing with the groups of kids/students. In this phase, the workshop participants are separated into groups consisting of 2–3 workshop participants per group. Each group assists a group of 3–4 kids/students in creating their study models based on their wishes, imaginations, and ideas of playing activities. The narrative stories of their models generate particular/ specific contents and concepts of their desired playgrounds in the schoolyard.

Study Models Made by Kids/Students

Study models made by kids/students are the abstractions of their wishes, imaginations, and ideas. The workshop participants then use and analyse them as references in understanding what kind of playing activities and patterns the kids/students like and want to do in the school playgrounds.

Study Model of “The Wall

A study model of “The Wall” is made by the project team as one of five playing elements in the schoolyard. The model is used as basic guidelines and principles in designing further detailed construction drawings. The Wall’s design concept itself is gained as the essence of the kids/students’ abstractions of wishes, imaginations, and ideas.

State of the Art: Schoolyard in Vilnius

Presentation of Design Proposals to the Kids/Students & Their Parents and the Teachers

All five project teams present five proposed playground facilities in front of the kids/students & their parents and the teachers. The project teams then receive some design suggestions and recommendations from the kids/students & their parents and the teachers to be considered as the last revision possibilities before fixing further detailed construction drawings and starting the construction phase of the playgrounds.

The educational system in Lithuania has experienced tremendous changes after the collapse of the Soviet regime in 1991. Since then, the educational paradigm has been shifting from classical to become more accessible, or in other words: liberal. On the other hand, the school’s physical-spatial structure and quality of spaces remain unchanged and hardly conform to contemporary requirements. The liberal preschool education performs close interactions between indoor and outdoor educational spaces. These kinds of educational spaces are both used simultaneously. However, the primary school, which usually operates in the same building as the secondary school, has lost the opportunity for outdoor education due to insufficient or even absence of outdoor facilities. Most of Vilnius’s comprehensive schools were built during the Soviet occupation period (1945–1990), and about 75% of the schools were constructed according to standardized projects. There are lots of secondary schools in Vilnius that perform primary education. These schools have large surrounding open spaces, which are still not properly designed and are still

poorly used for educational purposes. The growing interest and awareness of the outdoor environment as a valuable complement to the traditional classroom teaching style is a reasonable argument for improving the outdoor teaching style, which leads to improving the school grounds. The summer school targets this need by working to realize friendly, motivating, and inspiring playgrounds in the schoolyard, where children can spend their cheerful and relaxing playing time, moving around, and learning together. Moreover, the binational (Lithuanian and German) teams coach the kids/students together to familiarize the workshop participants from Lithuania and Germany with the diverse way of teaching. The summer school takes place at Vilnius Gediminas Technical University to introduce German workshop participants to the architecture curriculum of the faculty.

Five Playing Elements in the Schoolyard

As my team and I were working on “The Wall” during this summer school program, The Wall itself is one of the five playing elements on the schoolyard of Vilniaus „Versmės“

“The Wall” is Used as a Playing Facility by Kids/Students of Vilniaus „Versmės“ Katalikiškoji Gimnazija: After the inauguration of new playgrounds on the last day of workshop.

Final Construction of “The Wall” on the Schoolyard of Vilniaus „Versmės“ Katalikiškoji Gimnazija: Before the inauguration of new playgrounds on the last day of workshop.

Katalikiškoji Gimnazija. The other four playing elements are: 1) The Bricks; 2) The Surplus; 3) The Balancing Beams; and 4) The Tents. All five playing elements have different design concepts to serve and fulfill various playing activities and motoric purposes for 6- to 12-year-old children.

Concept and Development of “The Wall”

The Wall is formed through the keyform of five wall-shaped parts as vertical elements, although there are also two bench parts which are considered as horizontal elements. The main playing activities and motoric purposes that are served and fulfilled by The Wall are “observing” and “protecting.” The children can use The Wall as a medium to sit, stand, hide, seek, and even —in specific less-expected ways— climb when they are playing in the schoolyard.

The wall-shaped and bench parts have various heights to suit different heights of 6- to 12-year-old children. The wallshaped parts as vertical elements can be used for hide-andseek-based playing activities, while the bench parts as horizontal elements can be used for sit-and-stand-based activities.

Three of the five wall-shaped parts have framed ‘windows’, which can be used for sitting and stall shop role-playing activities, while the other two have some square- and circle-shaped holes as peepholes. The height of the bench parts is designed based on the height of regular footstools, chairs, and tables on anthropometric standards.

By using wood as the main structure and construction material, all wooden structures are joined by bolts. The construction of The Wall is based on the ‘bone’ and ‘skin’ principle. The bone parts as the inner structure (primary structure) are ‘wrapped’ by the skin parts as the facades. In its final form of construction, the bone parts are —almost— visibly unnoticed.

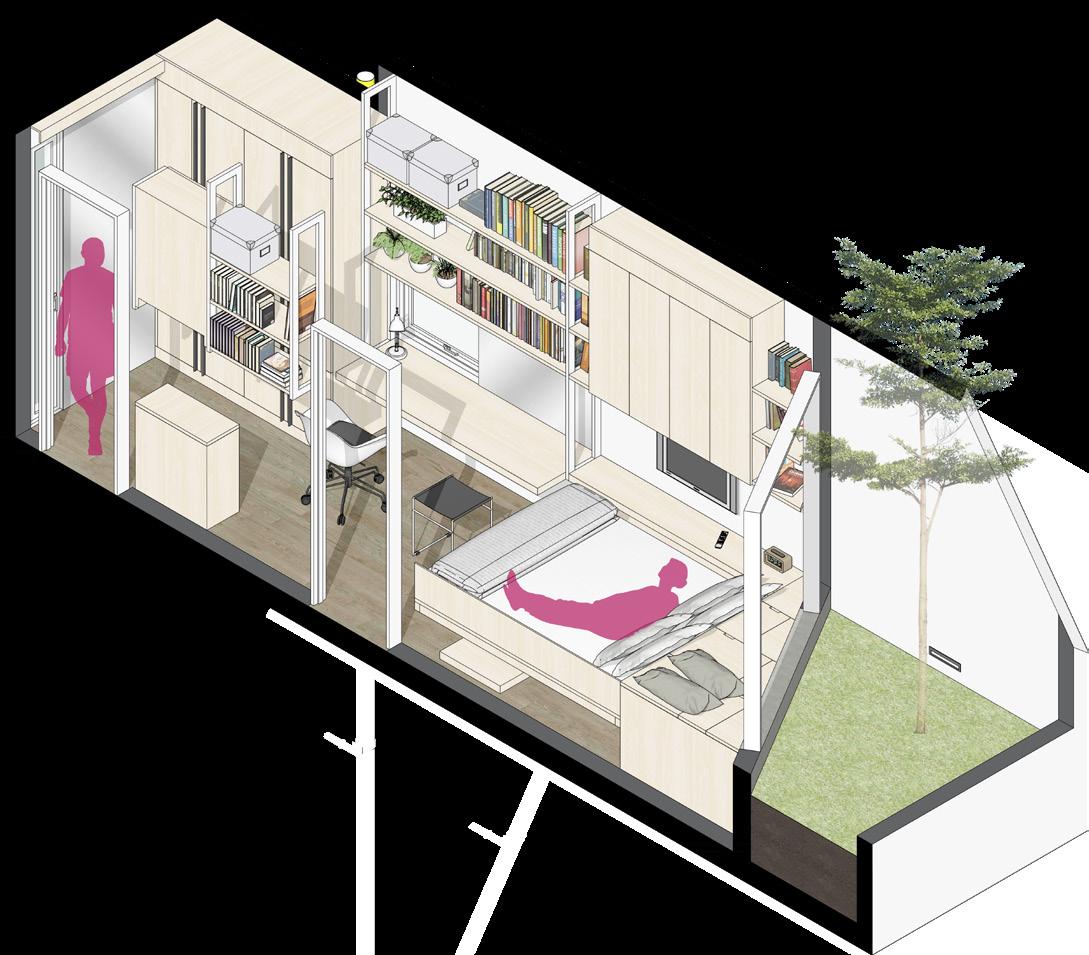

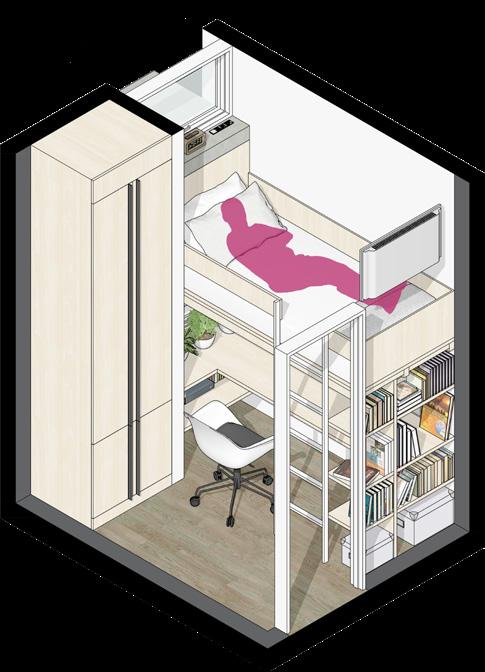

RUANGSISIP HOUSE

LUCID SPACES IN MOTION

South Tangerang, Indonesia

Site Location

Bumi Serpong Damai (BSD) – South Tangerang, Indonesia

Date February 2019 – July 2019

Phase/Status

Proposal (Professional Project)

Category

Project

Scale

Small

Type

Architecture, Other (Interior Design)

Typology

Cluster House, Landed House, Low-Rise, Mass Housing, Private Housing, Residential, Semi-Detached House, Small House, Urban Housing

Institution(s)

PT Image Qreator Indonesia

Client(s)

PT Bumi Serpong Damai Tbk. (Sinarmas Land)

Task

Designing a prototype of private houses for a mass landed-housing (cluster house) project initiated by PT Bumi Serpong Damai Tbk. (Sinarmas Land), a renowned Indonesian real estate & property developer.

Description

Apart from its social, economic, and environmental dilemmas & agonies at the urban level, when we talk about mass landed-housing, this particular issue always takes place: “The degradation of architectural values due to massive replication and massive repetition of architectural products.” Compared to custom-landed houses that can be proud of their sense of identity and uniqueness, mass landed-houses are less likely to possess values of individual identity and uniqueness of physical and visual-spatial aspects. Therefore, mass landed-houses always require more than just aesthetically pleasing facades as well as aesthetically pleasing space and form compositions.

Within a relatively small 72 m2 (6 m × 12 m) plot size, Ruangsisip House as mass landed-houses must be gaining things that are less likely to be achieved by custom landed-houses; not just in an innovative way but also in a revolutionary way. As a product of mass landed-houses, both indoor and outdoor spaces of Ruangsisip House are perceived as “spaces in motion” that are lucid, dynamic, and kinetic in progressive ways rather than perceived merely as “spaces in stilllife composition” that are exotic but static in conventional ways The principle of space in motion progressively results in inclusive spaces that are not only generally compatible for various types of activities but also specifically convertible in a modest and simplistic way to maximize the utilization of limited spaces for different types of activities. Every room in this house serves at least two functions: the living/dining area serves both leisure and dining activities; the library & study serves both working/studying and leisure activities; and each bedroom serves sleeping, leisure, and working/studying activities.

A Disclaimer: Problems with the Gated Community of Mass Landed-Housing

When I was a kid, I grew up in a gated community of mass landed-housing in the city of Bekasi, one of the satellite cities of Jakarta, located in the eastern part of the Jakarta metropolitan area. However, since I started studying architecture and urbanism in 2010, I have never been interested in this kind of ‘American Dream’ typical of urban planning & design. Since then, have been given to understand and become fully aware that a gated community of mass landed-housing segregates its residents from the ‘real world’ outside the gated housing territory.

In a deeper sense of housing, settlement, and urban studies, the gated community of mass landed-housing is also considered to be socially, economically, and environmentally unsustainable and inefficient. For instance, instead of taking a walk or cycling, people who live inside a gated community

of mass landed-housing need to take rides with their private automobiles or their private motorcycles for relatively long-distance commuting just for the sake of reaching the commercial area (shophouses/“ruko” or shopping centers area) that is located near arterial roads at the periphery of their gated housing territory. The same habit of commuting is also applied when people need to get out of their gated housing territory for work and school, where they are always dependent on the use of private automobiles and private motorcycles due to the long-distance commuting and the unavailability of public transport within the neighborhood of their gated housing territory. In fact, more automobiles and motorcycles, longer commuting distances, and less accessibility (due to the restricted gateway system) lead to more air pollution, more traffic jams, more wasted time, more wasted money, and fewer people-friendly streets & public spaces.

In many developed countries, such as Western European

countries, the approach of gated community-minded urban planning & design of mass landed-housing is already being classified as obsolete. Meanwhile, in Indonesia, this approach is still being eminently promoted and glorified by many lessvisionary urban planners & designers and profit-hungry real estate & property developers. It is also still pathetically loved and preferred by many people in Indonesia, including those living in urban areas.

Many people may argue that the approach of gated community-minded urban planning & design of mass landedhousing is a matter of safety issues due to higher crime rates in the cities in developing countries and ―with a hipsterish pragmatic argument― that it is eventually a matter of market demands. However, from advanced urban planning & design perspectives, establishing a gated community of mass landedhousing to fulfill the market demands doesn’t solve the safety issues at the basic & holistic levels in the first place.

“People react primarily to direct experience and not to abstractions. It is very rare to find anyone who can become emotionally involved with an abstraction.”

― Stanley Kubrick, 1965

In terms of mass landed-house design, where its scope of users is broad, general, and unspecific, my approach and philosophy of space in this design are focused more on people’s direct experience over abstraction of space, as not so many people can emotionally react to and interact with spaces at the abstract level.

Manifesto for Mass Landed-Housing

Apart from its social, economic, and environmental dilemmas & agonies at the urban level, when we talk about mass landed-housing, this particular issue always takes place: “The degradation of architectural values due to massive replication and massive repetition of architectural products.”

Compared to custom-landed houses that can be proud of their sense of identity and uniqueness, mass landed-houses are less likely to possess values of individual identity and uniqueness of physical and visual-spatial aspects. Therefore, mass landed-houses always require more than just aesthetically pleasing facades as well as aesthetically pleasing space and form compositions. The design statement of this project is that Ruangsisip House as mass landed-houses must be gaining things that are less

by custom landed-houses; not just in an innovative way but also in

Revolutionizing the Mindset of Property Developers in Indonesia: From “Square Mentality” to “Cubic Mentality”

When we talk about tiny houses, every cubic meter is valuable. It is essential to optimize the design and the composition of space in a 3-dimensional sense (space volume) rather than just in a 2-dimensional sense (floor area) since both the floor area and the space volume are limitary.

Revolutionizing Mass Landed-Housing in Indonesia: From “Space in Still-Life Composition” to “Space in Motion”

A custom landed-house may be able to be proud of its exotic material choices, and/or its magnificent craftsmanship quality, and/or its unique and unusual construction details, and/ or its sophisticated anti-mainstream spatial composition, while most mass landed-houses are generally not keen on that sort of architectural privileges. To cope with that lack of architectural privileges issue, as a product of mass landed-houses, both indoor and outdoor spaces of Ruangsisip House are perceived as “spaces in motion” that are lucid, dynamic, and kinetic in progressive ways rather than perceived merely as “spaces in still-life composition” that are exotic but static in conventional ways.

Generally Compatible, Specifically Convertible: Transformable Compositions of Inclusive Space

The principle of space in motion progressively results in inclusive spaces that are not only generally compatible for various types of activities but also specifically convertible in a modest and simplistic way to maximize the utilization of limited spaces for different activities. Moreover, the principle of space in motion is relevant in accommodating work/ study-from-home scenarios, especially amid the pandemic, where people are forced to compensate for regular office/ college/school days by working or studying from their homes. Through this principle, the bedrooms as inclusive spaces are able to be converted into three different modes to accommodate three types of activities: sleep, leisure, and work/study.

Ruangsisip House: Lucid Spaces in Motion South Tangerang, Indonesia

Puzzle Architecture: Sideyard as a Transformable Communal Space

Within just 92.5 cm of clear width, the sideyard of Ruangsisip House can be transformed into at least three different space compositions that are able to accommodate different types of activities. These three space compositions are formed through the arrangements of eight modular platforms as landscape furniture with the dimensions of l × w × h = 120 × 40 × 20 cm each, along with a portable entrance ramp that can be transformed into an extension of the sideyard’s platforms by folding it. These arrangements of the platforms and the portable ramp are perceived as compositions of puzzle blocks, just like Lego or any other similar kinds of 3-dimensional puzzle. The narrow space of the sideyard is progressively perceived as an outdoor space in motion that is lucid, dynamic, and kinetic rather than merely as a set of still-life compositions. Just like the living/ dining area and the bedrooms, the sideyard is also an inclusive space that is not only generally compatible with various types of activities but also specifically convertible in a modest and simplistic way to maximize the utilization of limited space for different types of activities.

Although a collectivistic mentality is at the core of Indonesian social structure in general, many Indonesians who live in urban areas nowadays tend to respect privacy more than ever compared to their suburban and rural counterparts. This individualistic tendency of living is prone to happen among people who live in urban areas in any big cities in the world, where they tend to be living in individualistic manners and socializing in heterogenous/cosmopolitan manners, in contrast with their sub-urban and rural counterparts, where they tend to be living in socialistic/communalistic manners and socializing in homogenous/endemic manners.

As the house is located under the urban context of the city of Tangerang, to keep the inhabitants’ privacy safe, the sites of Ruangsisip Houses are arranged in unmirrored linear repetitive rows. This arrangement juxtaposes the sideyard as a communal space with the service passageway of the neighboring houses. Furthermore, walls with a 3.6 m height (from the ground level) are erected between each house to increase the sense of privacy between inhabitants of one house and neighboring inhabitants of other houses. This unmirrored linear repetitive rows arrangement is also intended to juxtapose functional areas (bedrooms) with circulation & service areas (stairs and bathroom) of the neighbors, so that bedrooms’ windows don’t perpendicularly face other bedrooms’ windows of the neighboring houses.

However, each house still needs communal space to accommodate collective leisure activities, especially during weekends. Since one of the most common collective leisure activities among Indonesians is eating together with family, relatives, and friends, the eight modular platforms on the sideyard can be transformed into outdoor benches of communal space to accommodate the collective leisure activity of eating barbeque together.

Sideyard

Composition

Outdoor Communal Space: A Relevance Toward Collectivistic Culture in Indonesia

Ruangsisip House: Lucid Spaces in Motion South Tangerang, Indonesia

Presentation Model of the Project “Collective Memory of Historic Urban Traces, Morphology, and Identity in Urban Revitalization: Case Study of a Former Jewish Quarter –Vilnius, Lithuania” 2017

Scale 1:500 | Media: Styrofoam and Paper

3-Dimensional Form and Mass Study | 2009

Dimension: 18.00 x 18.00 x 56.00 cm (Dimension of Each Part

— Out of 2 Parts) Media: Paper

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe | 2010

Dimension: 42.00 x 29.70 cm Media: Mixed (Ink, Pencil, Colored Pencil, and Digital Printing on Paper)

Presentation Model of the Farnsworth House | 2010

Scale 1:100 | Media: Grey Board

Juliane 2016

Dimension: 21.00 x 29.70 cm Media: Watercolor on Paper

Portrait of a Young Woman 2011

Dimension: 42.00 x 29.70 cm Media: Pencil on Paper

Human Studies and Tree Studies | 2010

Dimension: 42.00 x 59.40 cm Media: Pencil and Watercolor on Paper