A Cup of Kindness

THE STORY OF DILMAH TEA

“We come into this world with nothing, we leave with nothing.

The wealth some of us acquire is owed to the efforts and cooperation of many others around us. Let us, therefore, share that wealth, while we are still around, so that, the goodwill and contentment created thereby, may make our world a happier place for others, too.

That is the objective of the MJF Charitable Foundation”

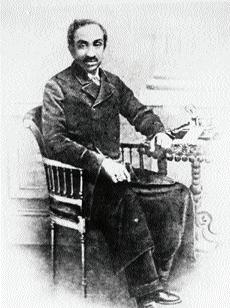

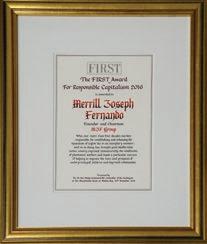

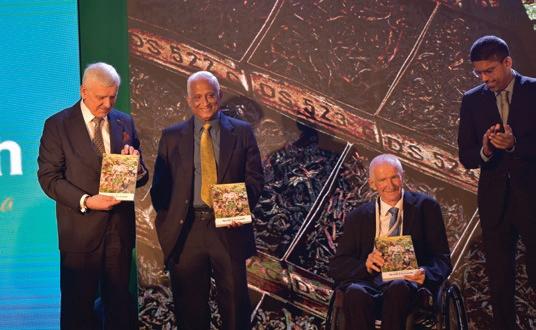

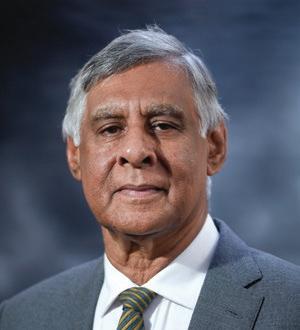

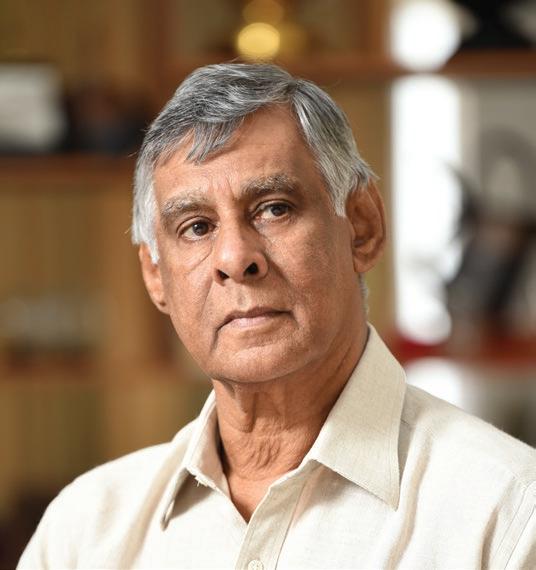

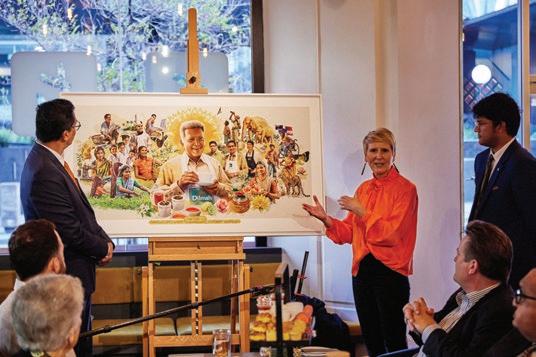

MERRILL J. FERNANDO Founder of Dilmah Tea 1930 - 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers

Copyright © Dilmah Ceylon Tea Co. PLC, 2025

Author: Anura Gunasekera

Art direction and design: Brand Marketing Team, Dilmah Tea

Photography:

Izabela Urbaniak, Bree Hutchinson, Sarath Perera, Malaka Premasiri & Rasika Surasena

Published by Dilmah Ceylon Tea Co. PLC. 111 Negombo Road, Peliyagoda, Sri Lanka www.dilmahtea.com

ISBN 978-955-0081-38-7

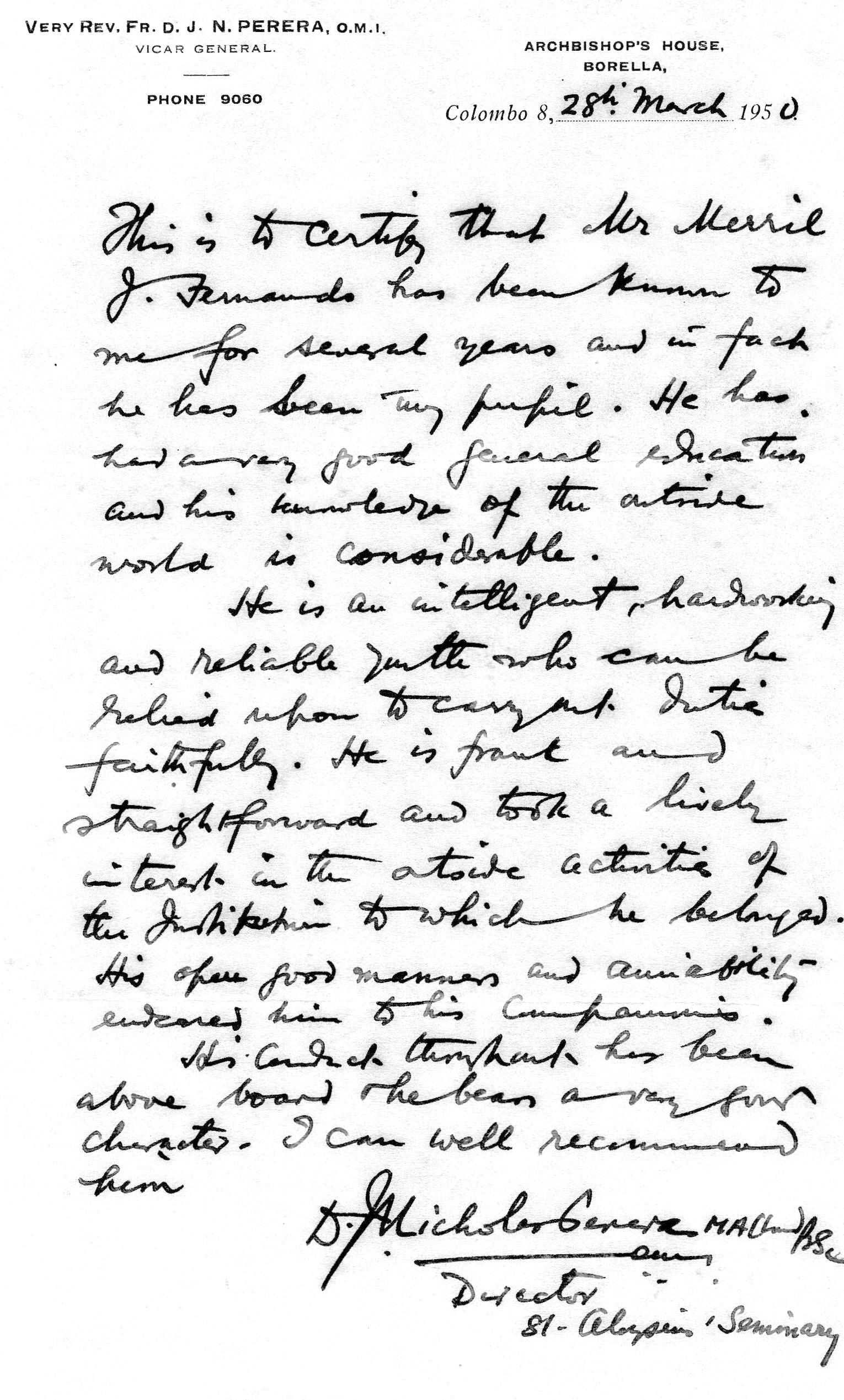

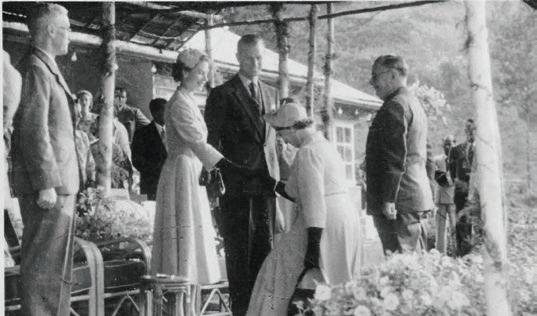

Merrill J. Fernando, the Founder of Dilmah, from the inception of his long journey in Ceylon Tea, was passionate in its cause and in the defence of its image. Early in his career, when he set out as a young independent entrepreneur, he also aligned his business philosophy along a trajectory which reflected his concern for his fellow-human beings and the environment.

Kindness is not a natural feature of big business, which is geared specifically for commercial success, leaving little space for genuine concern for humanity and the environment. Those aspects may have changed a little for the better in the new millennium, but much of the corporate responses to social and environmental issues still remain strategic and, often, are either cosmetic, or limited to minimal tactical compromises sufficient to meet mandatory requirements, regulatory pressures or societal expectations, but insufficient for the effective remediation of the real need.

Merrill J. Fernando, however, defined business as a “Matter of Human Service,” well before corporate social responsibility became fashionable, or mandatory. In the 1960s, when the young Fernando launched himself as an independent entrepreneur, he integrated with his enterprise the simple principles of community responsibility, absorbed in childhood from his mother. It was a time when such ethics were uncommon in business and, possibly, unappreciated. The mandate of corporate social responsibility, at that stage not even a concept but, from the beginning, an unlabelled pillar of the Dilmah enterprise, was a voluntary commitment by Merrill J. Fernando.

We live in a global society in which the enterprise environment is dominated by transnational corporations with tentacles across continents. Their very nature, the massive scale of operations, their financial power and influence on markets, communities, and even on governments, enable them to shape society and the environment and, yet, avoid responsibility for the detrimental consequences of their influence and actions, unless challenged by independent activists fighting for societal, community, and environmental rights.

The philosophy of kindness to the community and concern for environment, which Merrill J. Fernando espoused from the very outset, is of global relevance today. In a society driven largely by greed, in which both individual and community rights, and eco-system and environmental importance, are frequently trivialised in the quest for commercial success, it is now clearly established that the accommodation of social, environmental, and community concerns, is the only sustainable way of doing business. Given the glaring economic disparities and rising poverty indices, both within nations and between nations, and the steadily evolving spectre of climate change, which poses a singular threat to all communities – especially agricultural societies in the less developed world – it is absolutely clear, that there is no alternative to socially and environmentally responsible enterprise management.

Merrill Joseph Fernando’s life was one that was well-lived, providing a role model example of a socially responsible entrepreneur; not because such conduct was fashionable, good for business, or a mandatory requirement. He did business his way because kindness for his fellow beings and concern for the environment were inherent to his thinking.

The late Merrill Joseph Fernando, our father, dedicated his entire working life to the cause of Pure Ceylon Tea. He spent over seven decades in its service, with an unmatched passion and integrity of purpose.

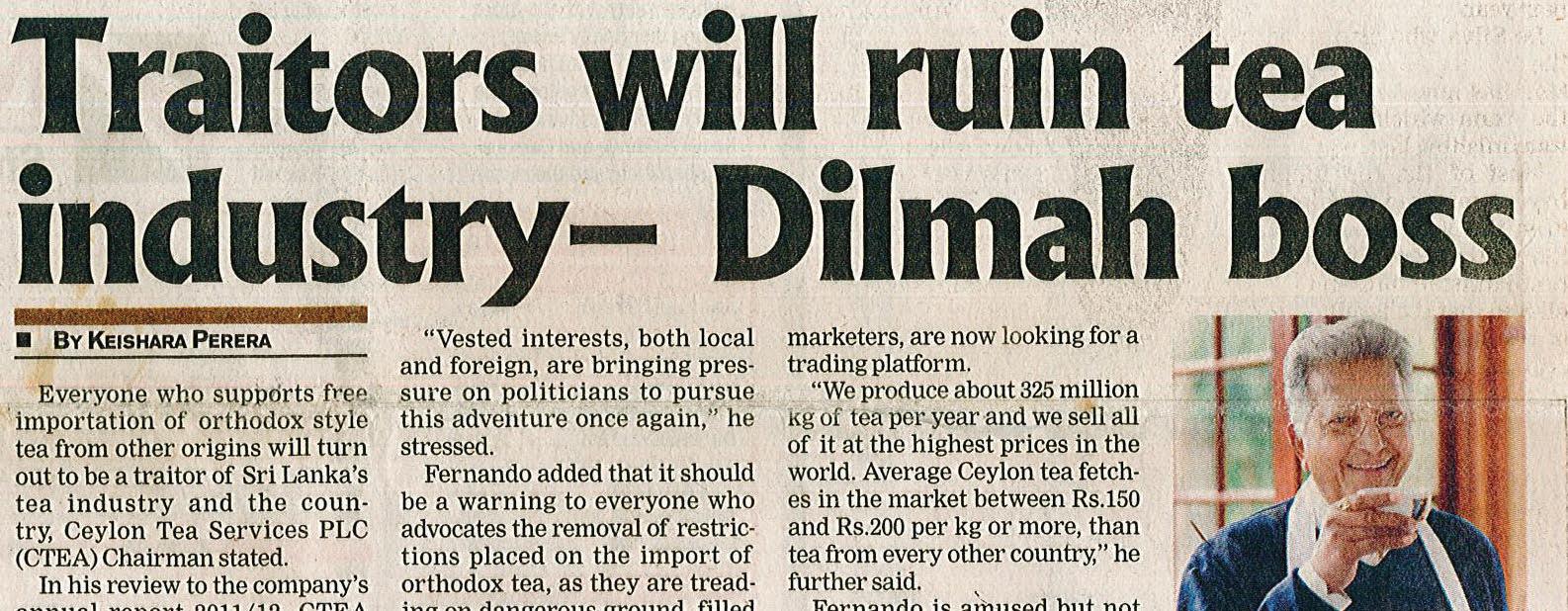

His commitment to the protection of the image of Pure Ceylon Tea, and his desire to advance its cause internationally, frequently pitched him into confrontation with both individuals and organisations. There were many who disagreed with his commitment to the preservation of the purity of Pure Ceylon Tea, especially when the dilution of that quality and the corruption of the image, offered both potential and opportunity for quick – but temporary – financial gain to many entrepreneurs.

Merrill J. Fernando’s defence of Pure Ceylon Tea was driven largely by his concern for the millions comprising small local farmers and plantation workers, engaged in the cultivation of tea, who stood to lose livelihoods as a result of the distortion of its image. His primary purpose was the greater good of those small people engaged in the industry and the sustainability of a national industry, not personal enrichment.

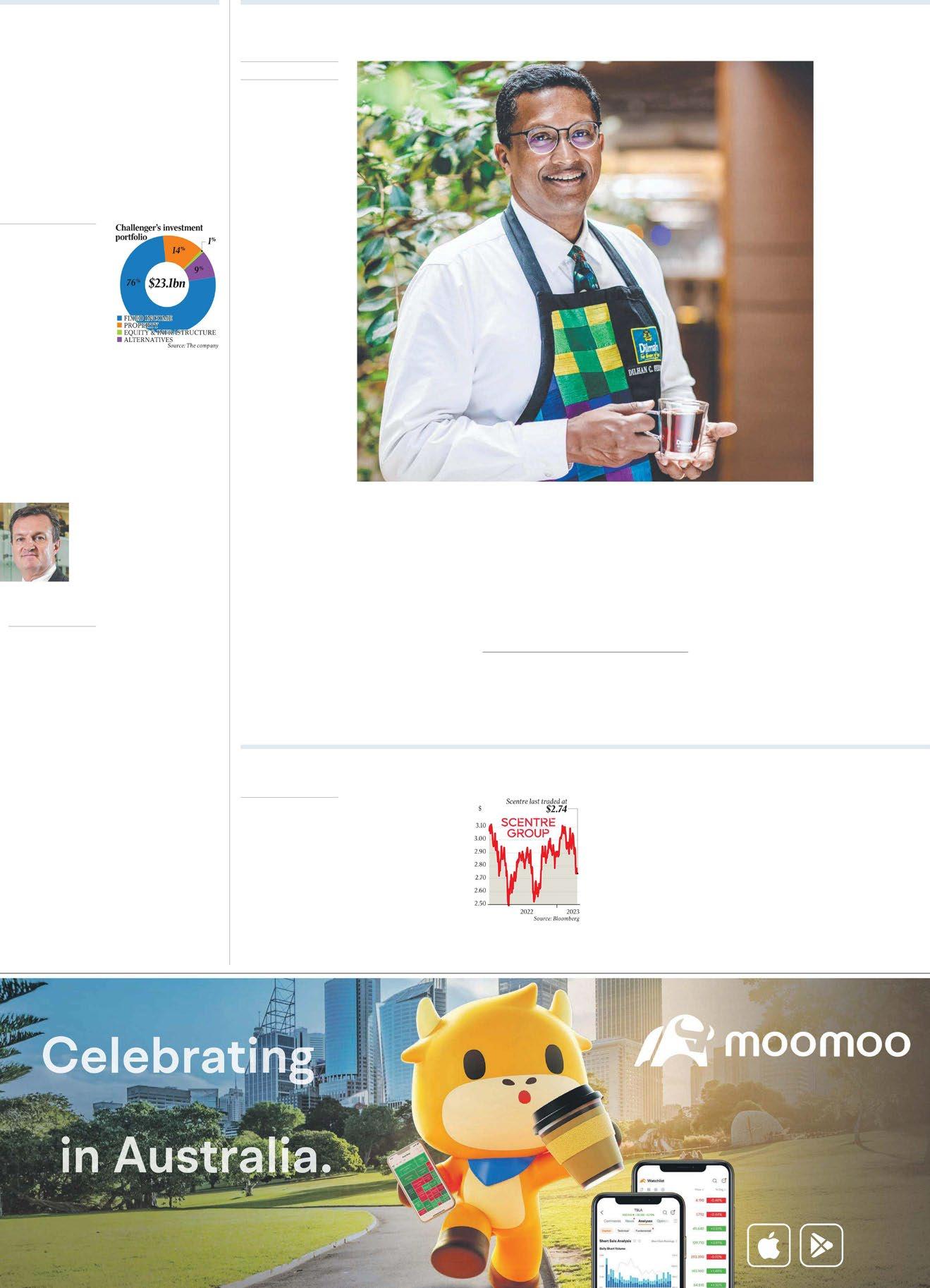

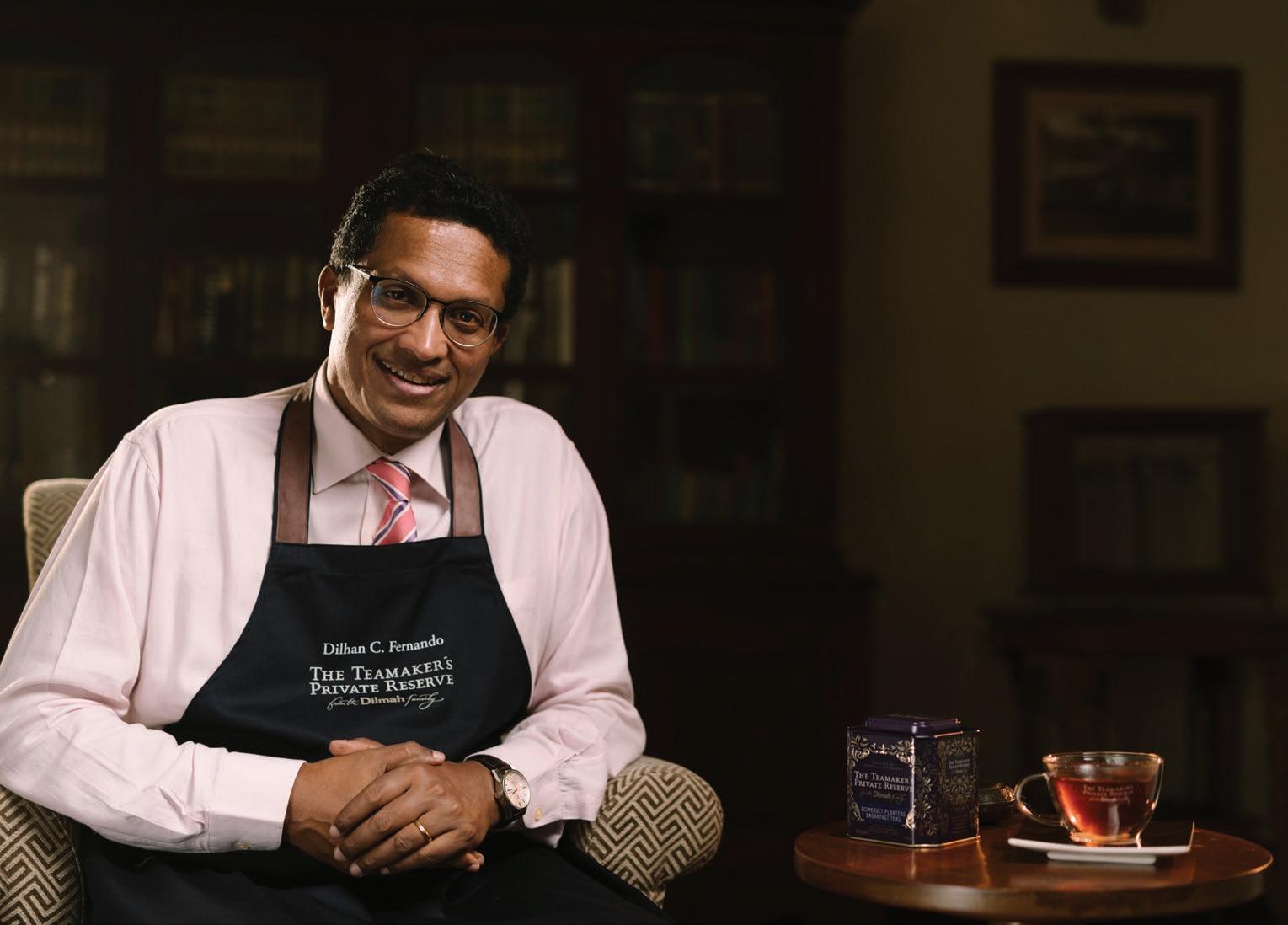

Merrill J. Fernando made it his life’s mission to take the message of Pure Ceylon Tea across the globe. He founded Dilmah, our family brand, in 1985, naming it after the two of us, Dilhan and Malik. Today, its presence in over a hundred countries has made it the global image of Pure Ceylon Tea. A major focus of his journey in tea was to share with consumers the pleasure of real tea; he introduced the world to the authenticity and singularity of a single origin family brand, and the difference it made to the daily cup. He transformed a

casual drinking habit into a pleasure, an experience to be savoured, and an occasion to anticipate with delight. He gave the world a better tea and Dilmah, Pure Ceylon Tea, was its ambassador.

His defence of the singularity of Pure Ceylon Tea, and its authenticity, has helped to bolster the sustainability of a huge national industry and the millions engaged in its service. It has contributed much to the securing of a national heritage, whilst the unique philosophy of social responsibility built into the foundation of Dilmah, has transformed the lives of underprivileged societies, marginalised individuals, and disabled children, and also helped revive and protect vulnerable eco-systems. Dilmah is no longer a simple, familyowned tea brand, but is also a great force for goodness.

Merrill J. Fernando left not just an enterprise, but a legacy of integrity, quality, and social responsibility. His commitment to giving the world a better tea, combined with the advocacy of workers’ welfare and rights, care for the environment, and for people, has set a new standard of community accountability for the industry.

As we of the next generation assume leadership, the focus will be on maintaining the core values which defined Dilmah from the inception. The transition represents not just a change in ownership and leadership, but also an opportunity for continued growth and innovation, whilst maintaining Dilmah’s leadership position in the market, along with conformity to its founding values. We will bring fresh insights and strategies to guide the company towards new horizons, whilst the Founder’s legacy remains a constant, a beacon for inspiration and a benchmark for emulation.

Dilhan and Malik

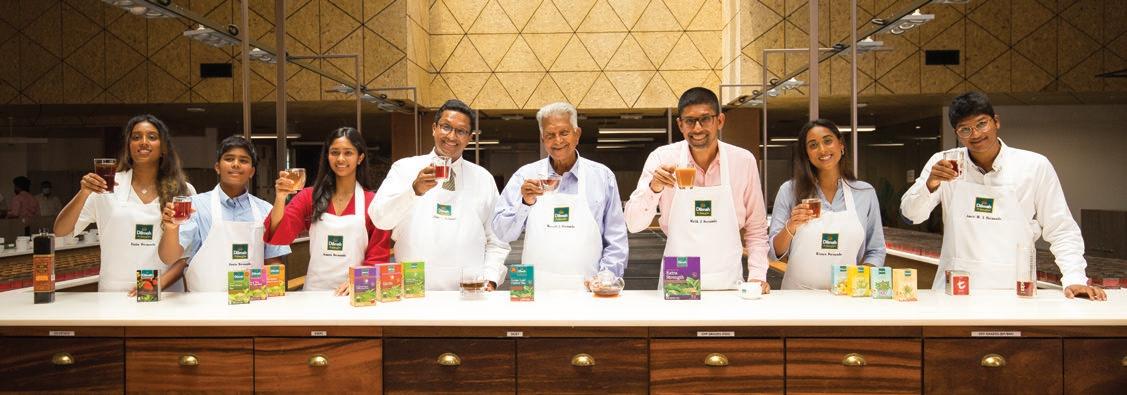

Merrill J. Fernando was a true pioneer, dedicating over 70 years of his life to championing Ceylon tea. As the visionary founder, leader, and CEO of Dilmah Ceylon Tea Company, he reshaped an industry. But to us, he was so much more – he was our beloved grandfather, or as we fondly called him, “ Seeya”.

From as young as four, we stepped into the Dilmah tea room, discovering the art and soul of tea-making under his watchful eye. It was in those moments that the seeds of pride, purpose, and honor were sown in us – values that continue to define our lives today as we carry forward the mission he began in 1985.

Our secondary education and university lessons often contradicted what Seeya taught us but his guidance and philosophy proved timeless and transformative. He redefined success, not in wealth or status but in love, care, and stewardship for people and the planet. He taught us to see beyond ourselves, to embrace kindness as the greatest wealth, and to nurture a life of purpose. He instilled the principle of faith across three generations, reminding us that our success and impact are not ours to claim but a reflection of the grace and blessings bestowed by God above.

Seeya’s love and luminous kindness would beam from across the room. He carried himself with a quiet grace and an unassuming strength, perfectly balanced with his humility. It was this humility that we admired most about our grandfather.

Looking back on our journey with our grandfather, we have come to realize that the greatest lessons he imparted were not about tea, accounting or marketing. Instead, they were lessons rooted in the values of integrity, unwavering commitment to quality, and the conviction that business should always serve as a force for good, dedicated to the wellbeing of humanity and nature.

As the third generation, we proudly carry forward the legacy of Dilmah and the MJF Foundation, guided by the wisdom and leadership of our parents. Our dedication remains unwavering as we honor our grandfather’s enduring promise: to offer the world a better tea, crafted with integrity and care.

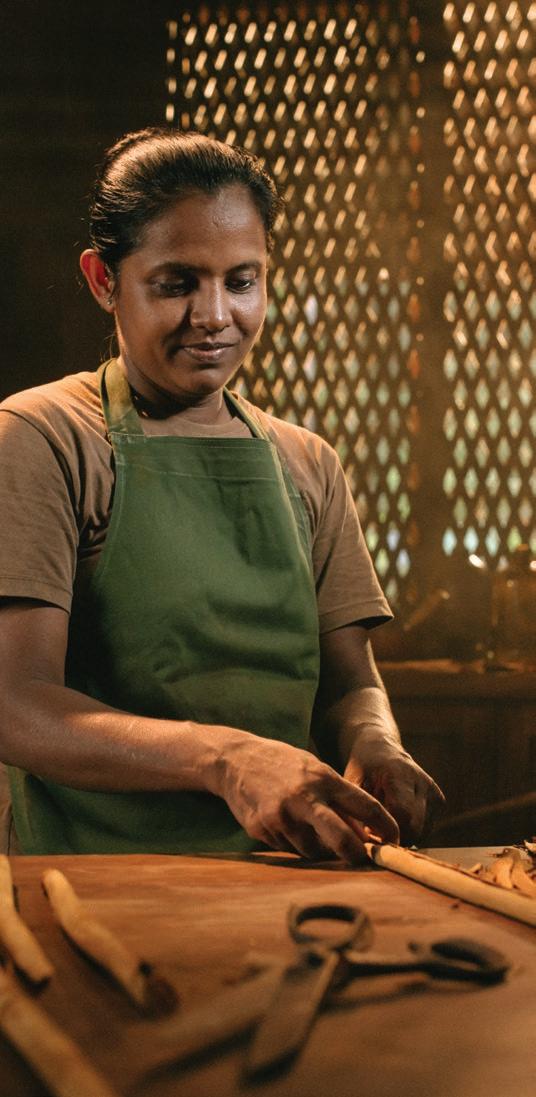

Looking ahead, we envision Dilmah as more than a name synonymous with Ceylon Tea. We see it as a beacon of hope for the marginalized, a force for the protection of vulnerable nature, and as a symbol of empowerment for the artisans of Sri Lanka, beginning with Ceylon Cinnamon. By championing their craft and preserving the rich heritage of our island nation, we will strive to make a meaningful impact for generations to come.

This is our pledge and promise to our late grandfather.

Kiyara, Tasha, Amaya, Devin & Amrit

“Cathay,” a poetic name for China, is said to have been first used in print by the Venetian traveller, Marco Polo, early in the 13th Century, AD. Odoric of Pordenone, a Franciscan Friar from Italy, writing about his travels in then China also used the same term, in parallel with Marco. Tea had its origins in China – the Cathay of the Western traveller – but its actual origin probably pre-dates its first historical mention by several centuries.

Ancient Greek geographers called our beautiful island Taprobane, a derivative of the more ancient name of Thambapanni, apparently that given by the legendary Vijaya (543-505 BC), the outcast Bengali Prince widely accepted as the first historical king of Sri Lanka. The Arab seafarers who roamed the South Asian sub-continental seaboard in search of spices, especially our cinnamon, called this compact, pear-shaped island “Serendib,” as early as the 4th century AD, probably as an easier alternative to the Sanskrit “Sinhaladvipa” – the abode of lions. Explorer Marco Polo is said to have referred to it as “Zeilan,” though he may have never visited it. The Portuguese who arrived at our shores in 1505 called it “Ceilao,” later Anglicised as Ceylon.

Ceylon was the last of the countries in the South-East Asian basin to start growing tea commercially but, Ceylon – the “Serendib” of the Arab mariner – today Sri Lanka, soon came to be identified globally by the wonderful tea it produced. As a national product, no tea from any other origin is so significantly benchmarked for quality.

It is this tea that Merrill Joseph Fernando, pre-eminent Teamaker of Sri Lanka, has taken to the world, as Dilmah – his personal creation – and positioned globally as the leading image of Pure Ceylon Tea.

To understand the magnitude of the journey that Merrill J. Fernando undertook more than seven decades ago, tea has to be viewed in its historical context. Firstly, China’s control and monopoly of tea for about twenty-five centuries and, secondly, the stranglehold on international trading and distribution of tea for over two centuries by the British and Dutch East India companies, entities with more wide-ranging powers than most governments of the day. This was followed by the domination of the cultivation, production, and trade of tea by British companies empowered and favoured by the British Government, and, thereafter, the limitless influence and outreach of the multi-national trading companies of today.

To succeed with Dilmah, Merrill J. Fernando, a small entrepreneur from a small country, both with limited resources, had to overcome the forces of history and the power of ruthless global trading systems, as well as opposition and prejudice at home.

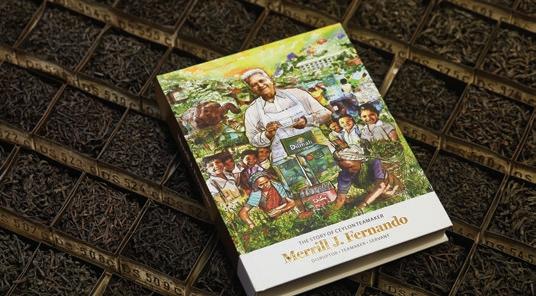

This book reflects on important aspects of that journey, recounted in fascinating detail in Merrill J. Fernando’s autobiography, ‘The Story of Ceylon Teamaker, Merrill J. Fernando, Disruptor. Teamaker. Servant’. In simple terms it is a story of triumph over adversity, of overcoming seemingly insurmountable odds; it is also a story of faith – in the authenticity of Pure Ceylon Tea, in the primacy of a genuinely socially responsible enterprise, and in one’s ability as a Teamaker, underpinned by sublime faith in a personal God.

Although the long and absorbing history of tea is too diverse, too complex, and too full of detail and incident to be dealt with comprehensively even in several volumes, this book outlines, very briefly, some of its more interesting aspects. To the uninitiated, it will serve as an introduction to that history and, also, to the evolution of tea as the most widely consumed beverage on the planet, next to water. This book is not meant to be a scholarly work but a brief, general introduction to tea to the random reader, and, more importantly, to the positioning of Dilmah in the wide world of tea.

Despite the global popularity of Ceylon Tea, there is a curious disconnect between point of production and point of consumption. The consumer drinking the daily “cuppa” with great enjoyment may have no concept of how tea is grown, made, or even of its properties of natural goodness. This book attempts to bridge that knowledge gap. Whilst tracing the

long and tortuous journey of tea, from ancient China to pre-modern Ceylon, it offers some information on the plantation industry in Ceylon/Sri Lanka and the manner in which the peerless Ceylon Tea is produced and brought to market. There is also a segment which explains some of the key health-giving properties of tea, especially when those features of natural goodness are preserved by its largely artisanal production, as in Sri Lanka.

The writing also explains why Dilmah is so special and stands apart from the thousands of other brands out there in the global market. And that is not just for its taste and goodness but, also, for the philosophy which drives the Dilmah enterprise. The book outlines the many initiatives which have contributed to that Dilmah specialness; the Fernando family’s personal assurance of bush-to-cup answerability, the sophisticated production technology accompanied by uncompromising attention to product quality, which reinforces that accountability and, in parallel, the caring for the environment and society.

The sustainability of the Dilmah enterprise is the result of a uniquely holistic approach to business, in a manner that skilfully, but transparently, balances conflicting features; environmental stewardship, social responsibility, product authenticity, stakeholder expectations, and economic prosperity. In sum, it reflects the rare and unquantifiable worth of a tightly-knit family business, driven by simple, old-fashioned family values, which defy replication within massive multi-national corporates.

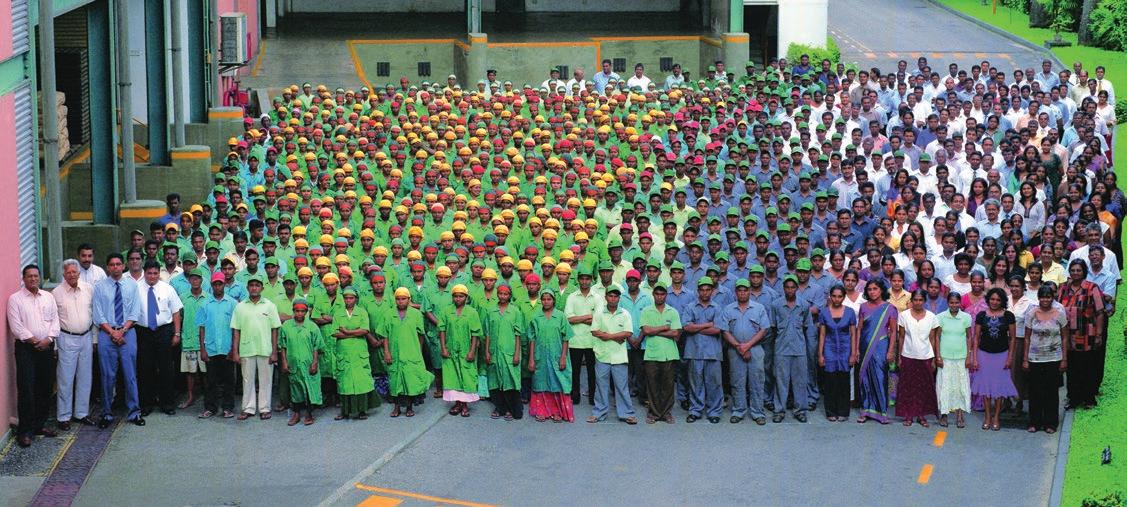

Merrill J. Fernando’s passion was to make the world a better tea and, with his earnings, to make the world a better place to live, especially for the underprivileged, the marginalised, and the disabled. It is a journey that is now being travelled and a mission being driven, by his children, Malik and Dilhan, and grandchildren, who have inherited the Founder’s passion and his unique business philosophy, of an enterprise powered by the principle, ‘Business is a Matter of Human Service’.

Anura Gunasekera

Author 12th January 2025

The story of Tea, through a combination of legend, folklore, adventure, discovery, intrigue and international commerce, reflects the culture and history of the countries where it is grown and drunk. It has shaped geographies, histories, economies and destinies of countries. Tea is embedded in customs, rituals, religious observances and in art and science. In its fascinating variety and allure, Tea is a beverage like no other.

The origin of tea is attributed to a serendipitous accident, in ancient China, in 2737 BC.

Chinese emperor Shen Nung, a renowned herbalist, on a journey through his lands, was resting beneath a shady tree whilst his servant was boiling some water. A few leaves from the tree had fallen into the pot and the resulting brew, which the emperor had consumed and liked because of its singular colour and taste, became the first infusion of Camellia sinensis. Shen Nung had found the liquor aromatic, flavourful, and restorative. The legend goes on to describe that, thereafter, he had encouraged his subjects to cultivate and drink tea as a health-giving brew.

It is a charming story and at this point in time, indistinguishable between myth, legend, or history. From that misty beginning, till its arrival in Ceylon about 45 centuries later, the story of tea is an equally heady mix of myth, folklore, romance, religion, intrigue, political and military adventurism, and, of course, commerce. There is no other beverage, or any other consumable in the history of the planet, with as compelling and as beguiling a history as tea. That aspect is also very much a part of its enduring allure.

Whilst there are other variants to the origin story of tea, all equally quaint and charming, as one travels further forward through the pages of history, other more credible and verifiable references emerge, establishing tea as one of the earliest of such nonalcoholic beverages to have been widely consumed,

though for many centuries confined primarily to the Chinese mainland. The recorded history of tea is as long as the long history of China itself.

What emerges from the thousands of accounts about tea through history, is that it originated in the monsoon-fed jungles of the Eastern Himalayas, and that early inhabitants of those regions, many thousands of years ago, through experimentation, or even by observing other mammals, such as monkeys, eating the leaf without any ill-effects, themselves followed suit. Obviously, such people would have found the leaf both a stimulant and a relaxant, and a sustainable energy-giver, whilst travelling in arduous mountain terrain.

A useful parallel is the use of coca leaves by ancient tribes in the Andean mountains of South America.

The leaf, which, in the 20th century, produced the lethally addictive “cocaine”, and laid waste to countless members of modern communities across the globe, had been a staple in the Andean life-styles for thousands of years, without causing the natives any visible harm.

The act of boiling a leaf and then consuming the hot infusion, is not something that suggests itself automatically to primitive societies. Therefore, the tea leaf would first have been eaten or chewed. In fact, in many communities in Burma, Northern Thailand, Assam, and Yunnan, people still eat tea leaves, boiled and prepared in various ways as a food. The Shan people of Northern Thailand apparently used to eat

the wild tea leaf, steamed or boiled and seasoned with salt, oil, garlic, pig fat, and dried fish. The Singpho and Kamttee people of the Burma border did something similar with tea leaf.

These practices are clearly derived from early primitive custom, of eating or chewing the leaf, as all food habits specific to indigenous communities have histories embedded in pre-historic practices. For instance, in Tibet, Mongolia, and other remote locations in Central Asia, especially at high altitudes, tea, liberally garnished with yak butter, salt, and sugar, is still consumed as a hot semi-soup. Given all the above reportage, it can be safely assumed that the connection between tea and humans, now a global addiction – benevolent, of course – has its roots in pre-history.

The earliest proven physical evidence of tea comes from the 2,250-year-old mausoleum, of Emperor Jingdi of the Han Dynasty, in Xi’an, suggesting that tea would have been consumed as early as the 2nd century BC. A writing of the first century BC, ‘The Contract for a Youth,’ attributed to Wang Bao, a classical Chinese poet (c. 84-c. 53 BCE), carries the first known reference to the boiling of tea. Similarly, the first reference to tea cultivation is also dated to this period, near Chengdu, in the mountainous regions of the Sichuan Province.

These historically verifiable references suggest strongly that tea cultivation, and tea drinking, would actually have become well-established practices in China, in the many centuries preceding its first

historical citations. Irrespective of all other factors, it is quite clear that the original home of tea was China, the legendary Cathay of the European traveller. Leaving aside the mythology, archaeological evidence also indicates that tea was being used by the elite of China for centuries, especially for its medicinal properties.

Within China alone, the journey of tea occupied several centuries. The first commercial tea cultivations of any size may have been in the mountainous Yunnan Province, adjacent to the Himalayan foothills of Tibet. It is this region, the South of China, that even today is the main source of tea in the country. By the time of the Tang dynasty (618-907 AD), tea appears to have become an everyday beverage, but still confined to the wealthier upper classes, probably because of cost and, also, the deliberate nurturing of an image of exclusivity surrounding its cultivation and consumption. Even within China, up to the Tang Dynasty period, tea drinking remained a largely Southern habit.

‘The Classic of Tea’ by Lu Yu (c. 760 CE), an orphan who was brought up in a Buddhist monastery and directly engaged in the cultivation of tea in the monastery gardens, is a primary source of information on the tea culture of the Tang period. He is considered one of the greatest of all the Chinese authorities on tea. The Tang Dynasty poet, Lu Tung, was another key figure in Chinese tea culture. The Sung Dynasty (960-1279), which followed the Tang Dynasty, a period of great literary achievement

in general, also produced an impressive volume of stories and poetry on the art of tea. In 1107, the Chinese emperor Hui Tsung wrote a comprehensive treatise on the culture of tea, ranging from its cultivation to its brewing.

Tea, in the form of compressed cakes or bricks, or packed into bamboo stems, was ferried on the backs of horses or camels along a network of caravan trails, connecting the mountainous regions of Sichuan, Yunnan, and further north into Tibet and Mongolia. Within the growing regions of China itself, in mountainous areas not accessible even to pack animals, tea was carried to main collection points by men. Eventually, tea found its way into the Levant and Anatolia, traditionally the last stops on the ancient Silk Road. Unsurprisingly, modern Turkey –which now includes the ancient Province of Anatolia – boasts of the highest per capita consumption of tea in the world today.

In China itself, tea drinking became such a widespread habit and a compulsion that it soon, passed into the hierarchy of needs of Chinese life, along with firewood, rice, oil, salt, soy sauce, and vinegar. Available records indicate that by the time of the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE) in China, tea culture had spread widely, no longer as exclusive as it used to be, being enjoyed as much for its taste as a beverage, as for its therapeutic value.

In the context of the commodity barter trade, which preceded the exchange of currency for goods, the highly-sought-after China tea would have been

as coveted as the fabled silks of Cathay. The fact that tea was a component of the prized parcel of commodities, comprising delicate fabrics, scarce spices, precious metals, and exquisite handicrafts, all traded under imperial monopoly and licensing, is a reflection of its high commercial importance even at that stage. Eventually tea became such a desirable commodity that, compressed into bricks, Black Tea especially, served as a de-facto currency in Mongolia, Tibet, and Siberia, well into the 19th century.

The importance of these goods was such that, despite the general lawlessness of the age and the frequent conflicts between the countries through which tea consignments passed, these caravanserai were often provided free and safe passage, underwritten by treaties, grants, and pacts, especially under China’s Mongol dispensation. In fact, Ibn Battuta (1304-c. 1377) Moroccan traveller and explorer, has written that China was the safest of all countries for the traveller, a view echoed by Florentine merchant, Francesco Pegollotti (1290-1347) speaking of the entire length of the Silk Road, from Central China all the way to the Black Sea.

“Tea is the elixir of life”

LAO

TZU (CHINESE PHILOSOPHER, CIRCA 570 BC)

There is an early nexus of tea with Buddhism, as Chinese Buddhist monks used to consume tea regularly, especially during long hours of prayer and meditation. Undoubtedly, the caffeine content of the tea would have energised them both physically and

mentally, and enabled them to stay focused for long periods. What is indisputable in the context of the evolution of tea cultivation and consumption, is its core association with Buddhism which, in various forms, exists to this day.

Till the initial stages of its domestication, which could be placed around the 5th century AD, the cultivation of tea was generally confined to monastery gardens. It was included in the Chinese pharmacopoeia, very well developed and sophisticated even then, as a herbal medicine and a therapeutic. However, apart from its curative properties, tea was found to be tasty and invigorating and, as a result, it was soon being consumed as a beverage. From that point onwards, its adoption by the wider society was a matter of time.

In its more austere forms, the ceremony of the preparation of tea and its consumption symbolises the ethos and practices of yoga, Zen, and meditation. The combination of strict ritual, attention to minute detail, mindful movement, and the tranquillity that the process induces, encouraging a cultivation of inner harmony, invests the preparation of tea with a spiritual quality that equates it with a religious experience.

The words “Cha Dao,” or the “Tao of Tea,” can be traced back to the poetry of Jiao Ran – Buddhist monk and poet of the Tang dynasty – extolling the virtues of drinking tea.

Tea drinking was much appreciated by modern poets as well, as seen below, even one famous for his advocacy of hallucinogenic drugs and abuse of

alcohol, a lethal combination which resulted in an early demise.

“The first sip is joy, the second is gladness, the third is serenity, the fourth is madness and the fifth is ecstasy”

JACK KEROUAC, AMERICAN NOVELIST AND “BEAT GENERATION” POET, 1922-1969

“Zen” (Chinese; Chan, Korean – Son; Vietnamese –Thien), a reformed school of Mahayana Buddhism, said to have originated in China in the 6th century CE, means meditation. In this discipline, the path to spiritual enlightenment required monks to spend hours in deep inward focus. It was during this period that the regular consumption of tea became a feature of Chinese monastic life. Around the same period, Japanese monks travelled to China to study Buddhism, and, along with the philosophy, also acquired the tea drinking habit and took it back to the Buddhist monasteries of Japan. Historically, Japanese Buddhist monks Saicho (767-822 CE) and Kukai (774-835 CE), are said to have been responsible for first returning from China with tea seeds and leaves.

The ritual of its preparation and drinking, governed by a strictly observed set of rules, protocols, and conventions, was known as “Cha-No Yu,” or the “Way of Tea”. By the Heian period (794-1185), ceremonial tea drinking had also become a favourite pastime of Japanese Royalty and aristocrats.

Tea drinking in Japan appears to have kept pace with the spread of Zen in the country. By the time of the Kamakura period (1185-1333) and beyond, the influence of Zen had become both widespread and powerful, with Zen temples being established throughout Japan under warrior patronage. The Japanese Zen monk Eisai (1141-1215) too, after a period of study in China, returned home with tea seeds, and thus began its widespread cultivation in Japan. First planted in monastery gardens, its cultivation and consumption soon spread outside temple walls. The Muromachi period (1333-1573), saw the emergence of a more elaborate tea ceremony –much richer than the ascetic monastic ritual – being practiced in their castles by the Japanese shoguns and feudal barons.

“I am a humble tea merchant, pouring out the elixir of life to the world”

KAKUZO OKAKURA - 1863-1913; JAPANESE ART CRITIC AND AUTHOR OF ‘THE BOOK OF TEA’)

Another interesting version of the introduction of tea to Japan is the story of the Chinese Buddhist monk, Chien Chen (688-763 CE), who had accepted an invitation to Japan and brought with him a wide range of medicines, which included tea seeds, as well as turmeric, cloves, fennel, sandalwood, and sugar.

Whilst the version of the introduction of tea by Eisai has greater historical validity, the contributions of the others mentioned cannot be discounted.

Consequent to the introduction of tea to Japan, tea drinking spread to Korea, as records indicate,

early in the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392). Here again, the connection between ritualistic tea drinking and Buddhism is significant, with tea being offered frequently to revered monks in temples. The Korean ruling elite also adopted the custom of tea drinking, both as a daily practice and as a special ritual reserved for more significant occasions, the latter distinguished by elaborate protocols regarding the use of special utensils, method of preparation, and serving style. In fact, they all mirrored tea-related practices then in operation in both China and Japan.

The spread of the tea culture and the spread of Buddhism appear to have moved in parallel, in both Korea and Japan.

In all these countries, apart from the elaborate customs associated with the preparation and consumption of tea, another significant feature was the use of specially crafted, ornately decorated, exotic utensils, either stone-ware or metal, and, especially amongst the aristocracy, rare and delicate porcelainware. The importance attached to the ritual itself was such, that servants and retainers were not permitted to prepare the tea. That was done by a senior member of the family, generally the matriarch.

The significance of the utensils was such that they were passed down from generation to generation. Obviously, from the very inception, tea drinking was elevated to the level of a special ceremony, associated with spiritual significance, mental well-being, physical health benefits, and a sense of occasion. This sense of exclusivity cultivated in ancient times

survived the passage of centuries and, in many societies, remains so to this day.

It was the Chinese, however, with their culture of literacy, philosophical learning, appreciation of beauty and the arts, and a reverence for tradition reaching back to several thousand years, who were the first to see the depth of potential of tea, as a civilising influence, which transcended its practical value as a popular beverage. This sensitivity was

reflected in the development of ritual surrounding its consumption, subsequently emulated by tea drinking societies in other nations.

Curiously, despite the wide consumption of tea in China, Japan, and other adjacent countries, extending all the way through Afghanistan to Anatolia, and parts of the Middle East by about AD 1000, its popularisation in Europe did not take place

till the 16th century. One reason is that though there were limited tea related interactions with Japan initially, and other nearby countries later, successive Chinese administrations were very secretive about the methods of cultivation and processing of tea.

Despite the intense commercial dynamism of the Silk Road, direct interaction between China and the European countries seems to have been intermittent and sparse, and not widely reported on, till the appearance of the Italian explorers, Niccolo, Maffeo, and Marco Polo, in the period between 1264 and 1295. Marco Polo’s colourful descriptions of his travels, with vivid accounts of his sojourn in the fabled court of Chinese Emperor Kublai Khan, would have stimulated interest in a land which was, until then, as far as most of Europe was concerned, largely mythological.

The earliest reference to tea, in European literature, is attributed to Giovanni Giambattista Ramusio, a Venetian writer, who, in his book ‘Navigationi et Viaggi’ (Navigations and Travels) called it “Chai Catai,” or “tea of China”. The first volume of the book was published in 1550, the second in 1556, and the third in 1559, after his death (1557). In 1678, a Dutchman, William Ten Rhinje (1647-1700), is said to have imported the first tea plant to come to the West. Another Dutchman, Jan Huygen van Linschoten –spy, merchant, traveller, and writer – in his book ‘Itinerario,’ published in 1596 (later translated as ‘Discours of Voyages into Ye East and West Indies’) described tea as a drink being consumed by the Chinese and the Japanese, identifying it as “chaona”.

Englebert Kaempfer (1651-1716), a German naturalist, physician, explorer, and writer, also an employee of the Dutch East India Company, in his voluminous ‘History of Japan,’ included a well-rounded treatise on tea.

Formal trade between China and Europe, which facilitated the dispatch of tea to the West, actually began with the arrival of Portuguese mariner, Jorge Alvares, in the City of Guangzhou, in 1517. In 1519, the Portuguese merchant-mariner Pires de Andrade established a trading post on the Pearl River, first in Zhujiang and then in Canton. In 1557 the Portuguese established a post in Macau and, subsequently, news of “Chai Catai,” a Chinese herb with medicinal properties, popular in the Sichuan Province, was being reported to the outside world.

In 1606, a ship of the Dutch East India Company, brought the first commercial consignment of tea to Amsterdam from China, although travellers and mariners, especially the Portuguese, may have earlier returned from the East with small personal packages. By the end of the century the Dutch were the largest European consumers of tea.

A few decades later, around the middle of the century, there was a short-lived interest in tea in Paris, apparently influenced by Cardinal Mazarin (1602-1661), briefly Chief Minister to King Louis X111 (1601-1643), who himself became an avid consumer.

Consistent with the opulent tradition of the French court, the French Emperor is said to have steeped his tea in a solid gold teapot. However, the habit did not spread, possibly because of the expense, and remained confined to select social circles.

In about 1636, tea travelled to Russia, the first consignment being a gift of four “poods” (65-70kg), from the Mongolian ruler, Altyun-Khan, to Czar Michael Fyodorovich of Russia. Around the middle of the century, the then Chinese Ambassador made another gift of tea to the then Czar, Alexei Mikailovich. In Germany, as in France, the interest in tea did not take root, nor last long. However, by the last quarter of the 17th century, large consignments of tea were making their way overland, in camel caravans, to Russia.

The relaxation of restrictions on foreign trade in the 1680s, during the Qing period of China, led to a sudden increase in the exports of porcelain, sugar,

and, in particular, tea. This period also marked the emergence of a new dimension in contacts between Europe and China.

From the inception till the 15th/16th centuries, by when the drinking habit had spread to several other countries, the tea output of China was mostly in the form of Green Tea, Oolong Tea, and other unfermented or semi-fermented specialist varieties. These found easy acceptance in Japan, Tibet, Mongolia, and within China itself. However, transport distances and extended travel time compelled the Chinese producers of Green Tea, to find a more practical alternative, with longer shelf-life and better keeping qualities. Those outcomes were achieved with some adjustments to the manufacturing process.

Thus the highly oxidised Black Tea, more resistant to change and contamination during transport, and with a stronger, coloury liquor, came into being.

As with the near-mythological origin of tea itself, there are other unusual stories about the origin of Black Tea. However, it is most likely that the production of Black Tea was stimulated by the need for a hardier alternative to the more delicate Green variety. That factor apart, Europeans, even at that time, showed a marked preference for loose tea, as against the cakes of compressed, green and semifermented tea, popular in Tibet, Mongolia, and further North. The new method of manufacture, which, in simple terms, involved the rolling of the withered, raw green leaf, followed by the drying of the broken, fully-fermented tea leaf particles, under artificial heat, yielded a robust tea with a red liquor. In China it was first known as “Hong Cha,” or red tea. Due to the heating of the fermented leaf particles over open fires of pinewood, the commonest method at that time, the liquor also acquired a smoky aroma and flavour, and this tea acquired fame as “Lapsang Souchong”.

Consequent to the formal introduction of tea to Russia, in 1679 Russia signed a treaty with China for the delivery of tea, by camel caravan, in exchange for furs. Due to the difficulties of overland transportation, tea was at first a very costly commodity, affordable only by the wealthy merchant class, boyars, and the aristocracy. In 1689, the Treaty of Nerchinsk, signed between the Qing Dynasty of

China and the Tsardom of Russia, resolving a border conflict and defining the Northern boundaries between the two countries, also marked the creation of the “Tea Road” between the two. By the time of the death of Empress Catherine the Great of Russia, in 1796, Russia was importing over three million pounds of tea annually, in the form of loose tea and bricks.

Tea caravans unloaded their cargoes at Kashgar, the largest westernmost city of China, and, for over 2,000 years, the most important staging post on the Silk Road between China, the Middle East, and Europe. A single caravan would deliver as much as 150,000 pounds of tea at a time. By the time the consignments selected by Russian traders traversed the Gobi desert and reached Moscow, the tea would have been on the road for anything between six months to a year or more.

The ancient tea culture of Kashgar can still be experienced in its authentic style and ambience, in

the traditional tea houses of the city, especially in its old quarter, which has remained unchanged for centuries. Bearded elders of the city, clad in baggy trousers and thick, warm coats, topped by ornate fez hats, still sit cross-legged on colourful carpets, to enjoy long-drawn out meals of traditional savouries and sweets, washed down by the thick, smoky tea, served in heavy metal pots and drunk from large, shallow ceramic bowls without handles. The age-old custom was to cradle the hot bowl in one’s palm and let the comforting warmth enter the body.

The increased volumes arriving in Russia contributed to price discounts and, eventually, enabled lower and middle class citizens to adopt the tea-drinking custom of the Russian elites. However, even after consignments of tea started reaching European countries more regularly, with the subsequent introduction of sea transport, especially the fasttravelling “clipper” ships, the general population of those countries did not adopt tea drinking as a regular habit. In countries such as Holland, France, Portugal, and Spain, coffee became the preferred beverage of the common citizens, whilst the nobility continued to enjoy the extravagance of tea.

The development of the three-masted, multi-sailed clipper vessels, with their distinctive, long, slim, graceful hulls, was actually stimulated largely by the need to transport the first tea of the season from China to ports in Europe.

Within a few decades of its introduction to the country, especially because of the very cold northern

climate, drinking of tea as a steaming beverage became very much part of Russian culture. As in all the other countries of its consumption, the drinking of tea in Russia too was invested with protocol and ritual and accompanied by culinary specialties specific to Russian food culture. A distinctive feature of the Russian tea drinking custom was the use of the “Samovar,” a modification of the Mongolian communal cooking pot, which, kept simmering throughout the day, enabled people to offer strong black tea to family and visiting friends at any time of the day.

Till the 17th century, a large proportion of China tea, if not all of it, was transported overland by camel and horse caravan. Despite their well-organised management and the Royal protection afforded to these baggage trains, in the countries which they traversed, the obstacles to safe delivery were still quite formidable. Apart from designed human aggravation, weather, climate, and terrain were also always hostile.

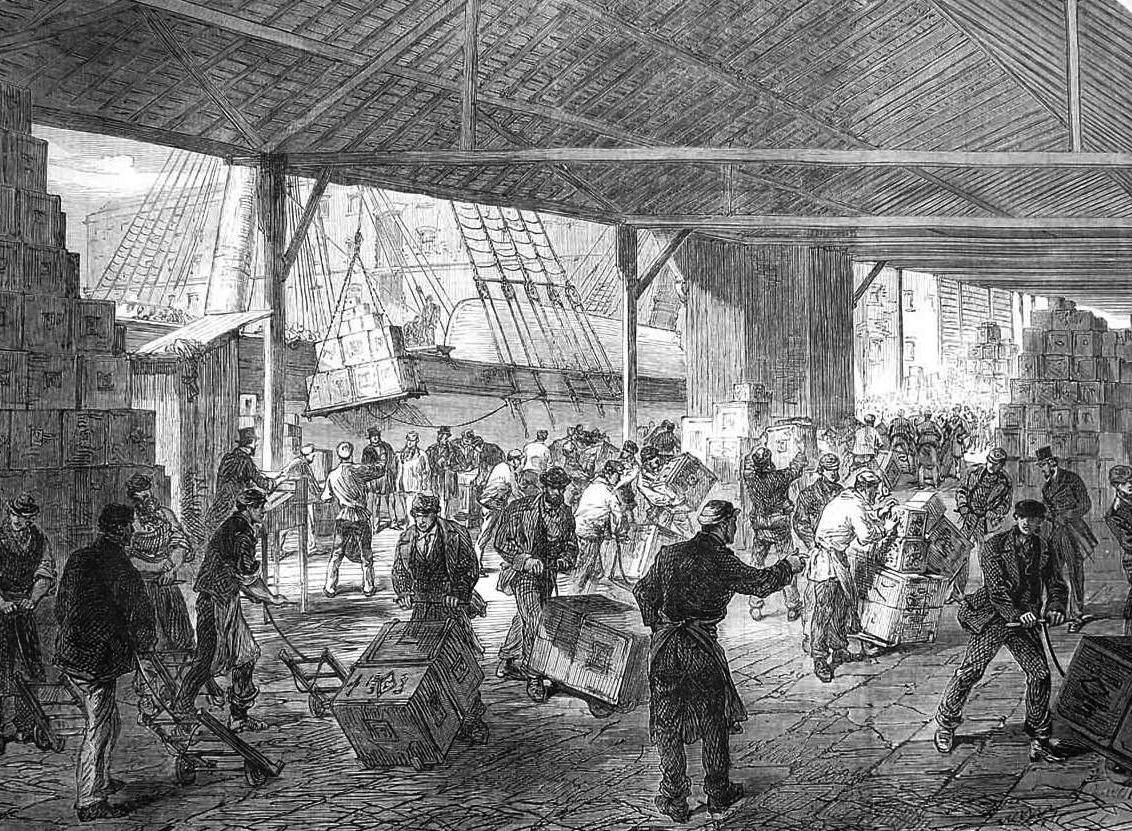

However, the emergence of the two giant trading companies, Dutch East India and British East India, within a couple of years of each other, changed the entire complexion of trade and economics of the countries in which they operated, and of the countries which fathered them, the Netherlands and Britain, respectively. The impact these two companies had on the global distribution and marketing of tea itself was considerable and irrevocably influenced its cultivation patterns as well.

Veerenidge Oostindsche Compagnie (VOC), the Dutch East India Company, received its charter from the States General of the Netherlands in 1602, two years after the granting of the Royal Charter to the English East India Company. For the next two centuries the two organisations were involved in a no-holds-barred competition, for regional and market hegemony. The operations of the VOC soon became crucial to the economic growth of the Netherlands, in the 17th and 18th centuries, whilst

the English East India Company made a similar contribution to the growth of the British Empire.

The two organisations played equally important roles in the export, sale, and distribution of tea, worldwide. The sea routes that their vessels travelled ensured the much quicker delivery of consignments of tea, larger by an order of magnitude from the volumes laboriously ferried by overland baggage caravans. With increasing supply, tea became cheaper and affordable even to middle and low-income groups, thus spreading the tea-drinking habit.

The VOC, a chartered trading company with a sweeping mandate, was the first joint-stock company in the world. With its Royally approved manifesto to trade across many colonies and countries, in both the East and West, it can be considered the world’s

first multi-national corporation. The extraordinary and wide-ranging powers accorded to this entity, to trade, to build forts, raise and maintain armies, to declare war or peace, to strike coin and currency, and to engage in treaties and agreements with other countries, also enabled it to offer a serious challenge to the Portuguese, already well-entrenched in the maritime trade in all the countries along the SouthEast Asian seaboard. Eventually, the VOC dislodged the Portuguese from previously held ports and cities, and, by the time of its dissolution in 1799, had been, for decades, a key player in the transport of textiles, porcelain-ware, tea, coffee, spices, precious metals, and even slaves. At its zenith, the company employed over 4,000 ocean-going vessels for merchandise transport.

Tea has an interesting history in America, terminating in a turbulent event now historicised as the “Boston Tea Party,” which took place on December 16, 1773. This pivotal incident, an American protest against the imposition by the British Government of a high tax on tea imports to America, marked the beginning of the American Revolution and the War of Independence, which led to the ceding of the North American colonies from the British Empire, and the establishment of an independent confederation of states, the precursor to the United States of America.

Petrus Stuyvesant (1610-1672), Director General of Dutch possessions in America on behalf of the Dutch West India Company, and Governor of New

Amsterdam (located at the strategically important southern tip of Manhattan Island and from 16241664, a provincial extension of the Dutch Republic), arrived in North America in 1647. He is said to have brought with him a consignment of tea for personal consumption. Consequently, the tea-drinking habit had been quickly adopted by the rich and powerful of the colony. In 1664 the British took over the colony and re-named it New York, after the Duke of York, later crowned King of Britain as James II.

In 1773, during the reign of King George the 3rd, the British Government imposed a tea tax on the North American colonies, despite the absence of the colony’s representation in the British Parliament. A primary reason was to provide financial support to the then struggling British East India Company, by allowing it a monopoly to export tea direct to American colonies and to sell through its own agents. Additionally, the company was granted an exemption on export tax. In protest against the wide-ranging concessions granted to the company, which were inimical to the interests of all other shippers and merchants, a group of white colonists, disguised as native Americans – “Mohawk Indians” – boarded a British clipper, the “Dartmouth”, anchored in Boston harbour, seized 342 chests of a cargo of tea, and threw the lot into the sea. The British Parliament responded in 1774 with a series of punitive measures, which were intended to subdue the colonists. The rising political tensions between the colonists and its British overlord, eventually led to the commencement of open warfare between the two parties in 1775.

The separation of the American states from the British Empire in 1783, and the subsequent boycott of tea by the Americans, as a reaction to the tea tax, led to a sharp decline in the consumption of tea in North America. That void was soon replaced by coffee, which was anyway being consumed up to that time, in parallel with tea. The patronage of tea, in view of its association with British domination and unfair taxation, was considered unpatriotic and, as a result, suffered by the conscious rejection of many of its earlier consumers in North America.

If you are cold, tea will warm you. If you are warm, tea will cool you.

If you are too depressed, tea will cheer you. If you are too exhausted, tea will calm you

WILLIAM GLADSTONE - 1809-1898; FOUR-TERM PRIME MINSTER OF BRITAIN

As mentioned earlier, the first reference to tea in English was in 1598, in an English translation of ‘Itinerario,’ by Dutchman Jan Hugo Van Linschoten. In 1615 the first known reference to tea by an Englishman appears in a letter by R. Wickham – an agent of the East India Company stationed in Japan –addressed to one Eaton, stationed in then Portuguese Macao. Wickham requests Eaton to send him a “pot of the best sort of Chaw,” undoubtedly a reference to tea.

The earliest historical records of the sale of tea in Britain are from the coffee houses of London, around 1657, when Green Tea from China was offered on the menu. This origin is attributed to Thomas Garway, tobacconist and coffee house owner of London. Apparently, in order to educate the public, tea was offered with an explanatory pamphlet, extolling the virtues of its consumption.

Invariably, as is customary in the global history of tea, there is an interesting story attached to its introduction to Britain, and the popularisation which followed soon after. Though tea came relatively late to Britain, the association between the two is of primary significance, as it was the Empire which was eventually responsible, both directly and indirectly, in promoting the cultivation of tea in the Asian and African countries famous for it today, as well as for organising the regular sale and distribution of the product, worldwide. The systems of cultivation, plantation management, processing, selling, marketing, and other related practices, initially

introduced by the British, are still in place today, with very little change, in all the countries which produce tea.

In 1662, Princess Catherine of Braganza arrived from Portugal to marry Charles the 2nd of England, in compliance with a marriage treaty between the two countries. Included in her baggage, along with sugar, spices, and other easily marketable goods –part of the Royal dowry – was a large casket of tea from China. The Portuguese had been importing tea

to Europe since the beginning of the century, and ceremonial tea drinking had become a cherished custom of the Portuguese nobility. Catherine introduced the custom to the court of Charles the 2nd and, soon, the British nobility of the day had adopted the habit. It also helped that Charles himself was already a tea drinker, having acquired the habit during his growing years, whilst living in exile (16461650), in The Hague, the Dutch capital, during the period of the English Commonwealth, under Oliver Cromwell.

EAST INDIA

First an English and later a British joint-stock company, formed under Royal Charter, very similar to its Dutch counterpart in composition and mandate, it was in operation from 1600 till its dissolution in 1874. It was founded by John Watts, under the patronage of Elizabeth I, and hugely empowered by King Charles II in 1678, the additional scope being sanctioned by a grateful King, probably in response to the expensive “gifts”, he and his brother received from the company.

At its peak the British East India Company was possibly larger than the VOC by various measures. The armed forces under its command at one stage, numbered around 266,000 men, twice the size of the then standing British Army. It was authorised to trade in the Indian Ocean Region, which included the

Indian sub-continent and most of South East Asia. The primary commodities it traded in were cotton, silk, indigo, dye, sugar, salt, spices, salt-petre, tea, and opium.

In the story of the merchandising of tea, as the globally renowned beverage that it is today, the importance of the contribution made by the British East India Company, in its cultivation, transportation, and distribution, cannot be overemphasised.

Initially, when the volumes of tea imported into Europe – especially Britain – from China, were small, it was paid for by trading cotton exported from Bengal, which was under British control. However, this trade dwindled as China improved its own cotton production. Silver maintained a balance of trade between Britain and China from about 1720 to 1770, till the American Revolution, by about 1776, cut off supplies of silver from Mexico, the chief source. Very soon, the purchase of tea from China was financed by the forced sale of opium in that country, by the East India Corporation.

The spread of tea consumption in Britain is inextricably intertwined with the equally widespread usage of opium in China, then the land of tea. In 1758, The British Parliament had given East India Company, the monopoly on the cultivation of opium in India. Acting on behalf of the British Empire, the East India Company enforced the barter trade of opium for tea, extracting acquiescence from a reluctant China, from behind the barrel of a gun; it

led to two wars, known as the Opium Wars, the first in 1839 and the second in 1860.

The opium that the company sold in China, the earnings from which it funded its purchase of tea from the same country, was grown in Bihar and Bengal in British-occupied India. In fact, opium was being cultivated in increasing extents in those regions, in order to fund purchases of silk, porcelain, and, above all, tea from China. It is said that by the beginning of the 19th century, the cultivation of opium involved over a million people in Bengal, the chief source of supply.

During that period opium was also smuggled into China by the Jardine-Matheson agency, which has since evolved into a highly-diversified and respected conglomerate, operating out of Hong Kong. According to reliable sources, between 1711 and 1790, tea purchases from China had increased from 142,000 pounds to 15 million pounds, reflecting a corresponding increase of opium deliveries into

China. In 1833, just before the Opium Wars began, the imports of opium into China had been worth around USD 12 million, in the currency of that time, whilst exports of tea were around USD 9 million.

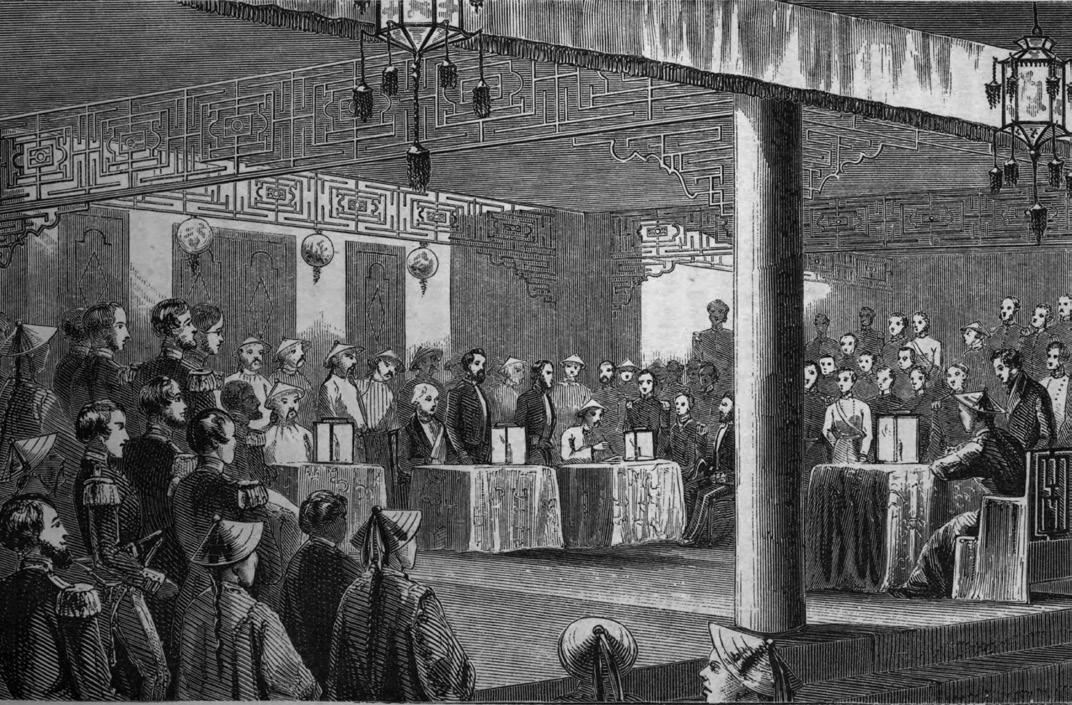

The first Opium War was the result of the British response – delivered through the gunboats of the East India Company – to the banning of opium and the burning of a year’s supply, by the Chinese Government, in a desperate effort to counter the dangers that its consumption presented to Chinese society. The tea-for-opium trade was a tragedy for the Chinese, on account of widespread addiction, whilst for Britain it was an indispensable source of revenue, as the tea that it purchased provided as much as 10% of State revenue, in the form of importation and sales taxes, during the Victorian era.

The first Opium War ended in a predictable defeat for the Chinese, a spin-off benefit to the British being the lease of Hong Kong island from China, in 1842. The second Opium War ended in 1860, with the Treaty of Tientsin, which legalised the importation

of opium into China. It was an inevitable outcome as the lightly-armed Chinese “sampans” were no match for the British gunboats. The agreements reached between Western powers and the Chinese government, consequent to military action, were “unequal treaties”, as the treaty conditions were weighted heavily in favour of the victorious Western powers.

A fact of interest is that America too, signed a similar trade treaty with China – known as the Treaty of Wangxia – in 1844. The reality was that whilst Western countries were greedy for Chinese products, such as exquisite furniture, silks and tea, China did not share the same appetite for goods from the West. This extractivist philosophy was already being unapologetically displayed by the British government, in India, another one of its colonies.

Interestingly, despite Britain imposing opium consumption on Chinese society through force of arms, Queen Victoria of Britain, under whose Royal sanction the company operated, banned the sale and consumption of opium in Britain. Obviously, with the moral ambivalence common to all colonial powers, she saw no harm in facilitating its consumption in an Asiatic society. The tea-for-opium trade was heavily weighted in favour of British society. Apart from the revenue it earned for Britain, tea provided a very healthy and hygienic alternative drink to the working classes of Britain, preferable by far to the highly contaminated groundwater of its large cities, or the heavy and stupefying beer of the British ale-houses, or the corrosive, crudely distilled gin,

served in the Victorian “gin palaces”. Thus, whilst the popularisation of China tea in Britain was helping to reduce alcoholism amongst the British working classes, in particular, opium addiction, supported by British-sponsored supplies, was laying waste to an equivalent segment of Chinese society.

William Gladstone (1809-1898), a minister of Queen Victoria’s Cabinet and, subsequently, four times a prime minister during her reign, was unequivocal in his condemnation of the British involvement in the opium trade in China. In a speech in Parliament 1880, he referred to it as “most infamous and atrocious”.

The treaty of 1860, which legalised the sale and consumption of opium in China, ironically, stimulated discussion and action amongst concerned colonial parties for an alternative source for tea, which, by that time, had become as addictive within British society, as opium was in Chinese society.

Vested interests in Britain had already become apprehensive about the Chinese monopoly on tea, and their secretiveness about its cultivation and manufacture. The legalisation of opium in China and its unrestricted cultivation in the country, was certain to soon neutralise the British monopoly on its supplies from India. The captive market in China would, shortly, become its biggest competitor. With Britain’s heavy reliance on the unwilling revenue collections from the colonies for internal

development – railways, roads, industries, and supporting a massive Civil Service – she could not afford any disruption to the balance of trade.

One of the first official warnings of the impending reversal of fortune, and the need for a counterstrategy, came from General Henry Hardinge (17851856), Governor General of India (1844-1848).

“It is in my opinion by no means improbable that in a few years the Government of Pekin, by legalising the cultivation of opium in China, where the soil has already proved equally well adapted with India to the growth of the plant, may deprive this Government of one of its present chief sources of revenue. Under this view, I deem it most desirable to afford every encouragement to the cultivation of tea in India. In my opinion the latter is likely in the

course of time to prove an equally prolific and more safe source of revenue than that now derived from the monopoly on opium.”

Clearly, British civil servants, whatever their private views on the morality of the British role in the opium trade in China, were under no illusions as to the possible adverse impact on the British economy, arising from the loss of that odious commerce.

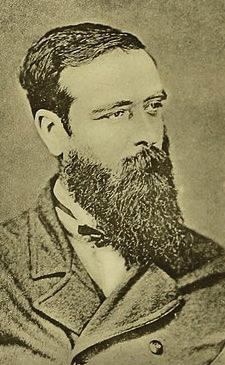

In 1845, self-taught botanist and self-made horticulturist, Scotsman Robert Fortune (1812- 1880), returned to England after a three-year specimencollecting expedition in southern China. It was a commission assigned to him by the Horticultural Society of Chiswick, his then employer. His massive collection, meticulously labelled and annotated, proved to be a botanic treasure trove of hitherto

largely unknown species of exotic flora. During his travels, to achieve success, he literally braved death several times, which included pitched battles and exchanges of fire with pirates in the South China Sea. After his return, consequent to the publication of a book on his travels in China, he acquired a justifiable reputation as the most knowledgeable Westerner on China’s interior. He was also able to secure a more prestigious and better-paid position, as Curator of the Chelsea Physic Garden.

In 1848, the East India Company offered a wellcompensated assignment to Robert Fortune; to travel to the interior of China and smuggle out – as the Chinese did not permit the export of tea plants – tea seeds or tea plants for cultivation in India.

Though Fortune had travelled widely in China on his first visit, venturing into areas no Briton had previously visited, he had travelled primarily from treaty port to treaty port. The company’s assignment would require him to penetrate inland China and travel to areas normally barred to foreigners.

In a three-year, largely clandestine mission, across the main tea growing provinces of China, including remote areas of Fujian, Guangdong, and Jiangsu Provinces, Fortune collected tea plants and seedlings from local growers, which were dispatched to the company’s representatives in India. The first consignment failed, on account of transport delays and incompetent nursery management, but the second batch had produced successful plants in the experimental gardens of North-Western India.

Apart from the seeds, Fortune smuggled out a group of experienced Chinese tea workers and set them to work in the tea fields of the Darjeeling region of India.

More than the plants that he sent back, what was most important was the knowledge of techniques of cultivation and processing that Fortune returned with. These were of immense value to the fledgling Indian tea industry and eventually cascaded to Ceylon as well. The seasonal Darjeeling teas still produced in the Himalayan foothills, derived from modern strains of the original Chinese plants, are amongst the most highly priced tea in the world today.

Whilst there are credible reports of tea drinking in India, even as far back as 750 BC, and even more recently as the 16th century, the credit for its rediscovery and commercial cultivation goes to the British.

In 1774, Warren Hastings, British Governor General of Bengal, is reported to have sent a few tea seed samples obtained from China to his colleague in Bhutan, George Bogle. Given the Chinese restrictions on the removal of tea planting material from the country, it is not clear how Hastings came by the seeds. In 1776, English botanist Sir John Banks, recommended India as a suitable growing country for tea. A few years later, Colonel Robert Kyd, Commanding Officer of a British East India Army Regiment, experimented with tea seed germination in an Indian Botanical garden at Howrah (presentday Kolkata).

In 1823, Scottish explorer Robert Bruce, assisted by Assamese nobleman Maniram Dewan, had discovered indigenous tea plants, growing wild, in an expedition to the Upper Brahmaputra Valley, in Assam. Apparently, the local Singhpho tribe was brewing tea from the plants, as a medicinal drink. However, Nathaniel Wallich, curator of the Calcutta Botanical Garden, identified them as a species separate from the Chinese variety, though modern botanists consider them to be variants of the same species, Camellia sinensis.

Maniram Dewan went on to become the first Indian to set up a commercial tea plantation.

The first consignment of Indian tea reached London in 1838. In the meantime, tea was being planted in different locations in Darjeeling and by around 1875, 113 plantations, covering about 180,000 acres, were producing close upon 4 mn pounds, annually. The success of tea cultivation in Darjeeling stimulated cultivation in Kumaon (Northern India) and further south in Garhwal, Kangra Valley, Dehra Dun and the Nilgiris. By 2017, India was producing over 1.2 bn kg of tea, annually, second only to China, the world’s largest producer.

A journey across 40 centuries

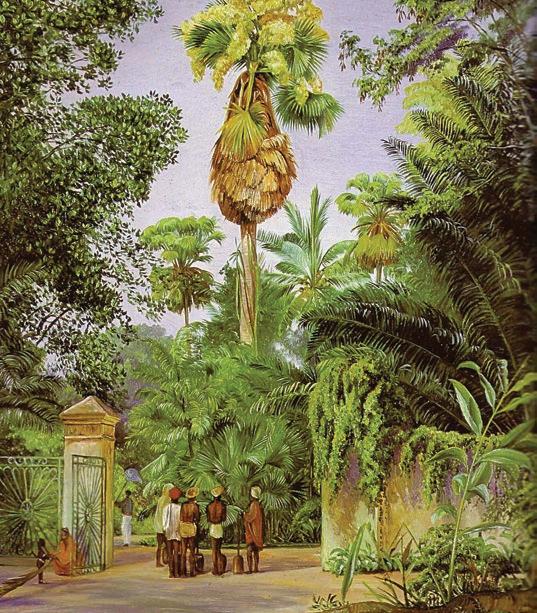

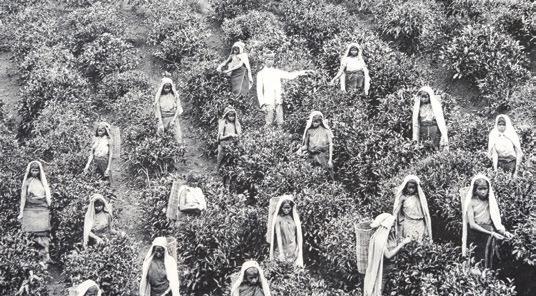

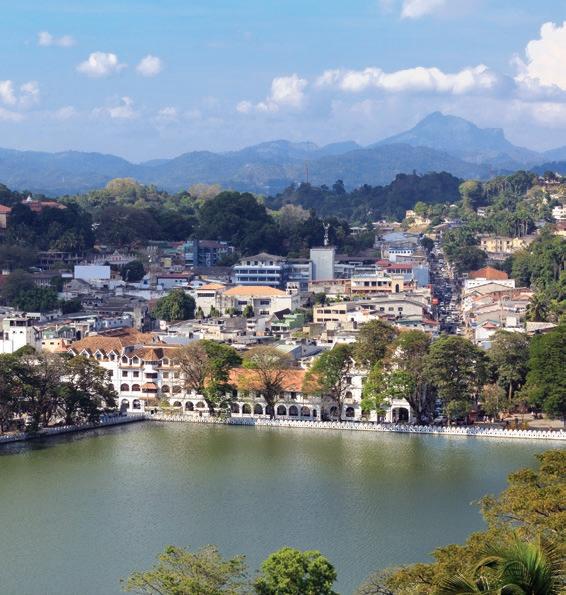

Ceylon was the last country in the South-East Asian sea board to grow tea. But no Tea is as celebrated as a product of a nation, as Ceylon Tea is. It shaped pre-modern Ceylon, configured its land, guided its political direction, altered its regional demography and gave it economic stability. Modern Sri Lanka is still under its spell and influence.

Plantation crops have played a significant role in the history and economy of Sri Lanka – then Ceylon – especially since the arrival of the Portuguese in 1505. Initially, what attracted Western invaders –the Portuguese and then the Dutch – was the famed Cinnamon of Ceylon, which had, historically, been one of the most coveted commodities from the island, for at least 15 centuries before the advent of the Portuguese. Cloves were another item on the list of preferred spices.

The Portuguese relied largely on existing traditional local systems, with a few innovations, for the production and collection of cinnamon. Areca nut was another important item of trade and barter, and of great commercial value, again preceding the Portuguese arrival by many centuries.

The Portuguese intervention in Sri Lanka led to a sharp increase in commercial activity, and a much higher degree of monetisation of the economy. The Dutch, following later, with their far more methodical and pragmatic approach to the commercial management of colonies, made considerable improvements on the model left behind by the Portuguese. The British, taking over from the Dutch in the first quarter of the 19th century, laid down the foundation of the organised plantation economy of the country, which flourished well into the 20th century.

The history of the commercial cultivation of globally desirable products is, most often, tied up with the

colonisation and domination of undeveloped nations and tribal societies, by commercially and militarily superior Western nations; exploitative and often linked to slavery, such as tobacco and cotton in North America, coffee and sugar cane in the Caribbean and, most infamously, rubber cultivation in the African Congo by Belgium. The story, first of coffee and then tea cultivation in Ceylon, today Sri Lanka, initially followed the same unattractive pattern, though in this country it was always paid labour and, certainly, never as brutal as the other examples cited.

The history of the island of Sri Lanka, located within touching distance of the southernmost tip of its giant neighbour, India, has been inextricably linked with the latter from before pre-history. At various stages, under varying circumstances, India has been its ally, friend, co-conspirator, and foe. India has been brotherly and helpful and, also, antagonistic and overbearing. For thousands of years it has been a love-hate relationship. Tea arrived in then Ceylon, from India, under British patronage, then the colonial master of both India and Ceylon.

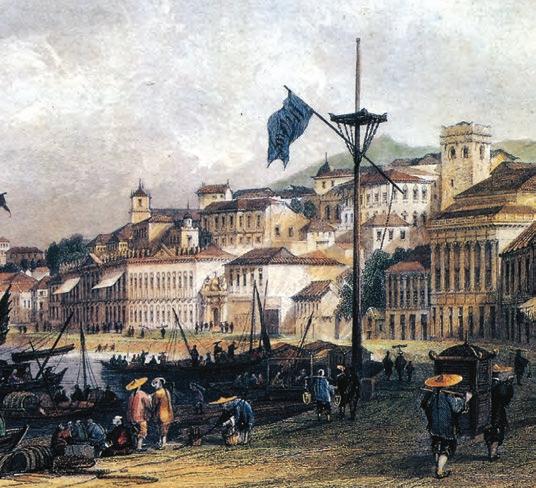

Portuguese mariners, who commanded the blue water trade along the South East Asian sea-board for much of the 16th century, first came to Ceylon in 1505; accidently in fact, when a fleet commanded by mariner Lourenco de Almeida was driven to the then Port of Colombo by adverse winds. In about 1518, with the permission of the then King of Kotte, Vira Parakrama Bahu, they built a fort at the mouth of the Kelani River. They were also given trading concessions.

The Portuguese stayed on till being comprehensively ousted by the Dutch, by about 1658, with some active assistance from the native administration, which had begun to find Portuguese intrusion into the country’s internal affairs intolerable. The Portuguese had been mainly interested in Ceylon Cinnamon, which grew abundantly along the south-western coastal areas and, also, inland. The Dutch, represented by the VOC forces, took over this trade with the expulsion of the Portuguese; gradually, they also took control of the entire coastline provinces, isolating the Kandyan Kingdom in the central hills.

In 1795, William V of Holland, the last Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic, abandoned his country to the invading French forces and fled to England. In return for his safe custody and asylum in England, he signed over control of all Dutch possessions in the colonies, across the globe, to the British. Gerard van Angelbeek, then Commander of the Dutch possessions in Ceylon, after a brief initial resistance, surrendered to the British, ironically, represented by the forces of the ubiquitous British East India Company.

By 1818, the British were in control of the island of Ceylon in its entirety, an advantage, from a military, administrative, and commercial position, that the previous colonial occupiers did not possess. This gave the British unrestricted access to large swathes of land, including commonly owned but un-demarcated, traditionally-owned land in farming areas, and massive tracts of virgin forest, especially in the central hills, which had been untouched for centuries.

In parallel with the consumption of tea, coffee drinking had also become highly popular in 19th century Britain. Supplies were mainly from the West Indies, where slave labour in the plantations enabled producers to maintain low production costs, rendering West Indian coffee highly competitive in Western markets.

In 1833, slavery was officially abolished across the British Empire and, with that, the profitability of the West Indian coffee plantations, especially those in Jamaica, declined drastically. That gave Ceylon coffee, which had hitherto been more experimental and a widespread cottage industry than an organised commercial enterprise, a massive boost.

British Colonial Governor Edward Barnes of Ceylon (1824-1831), following the example of his predecessor, Thomas Maitland (1805-1811), dedicated to the concept of developing plantations in the colony, hastened to provide the colonial entrepreneurs and British Government officials in Ceylon with land for coffee.

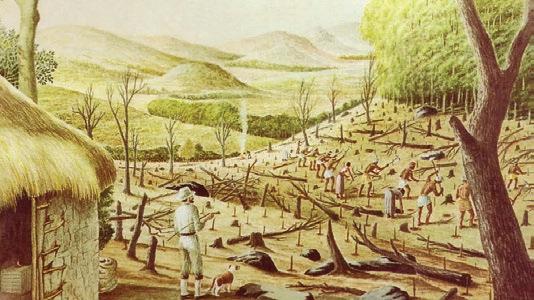

The acquisition of land, either as grants or at rockbottom prices, by British entrepreneurs, military men, civil servants, employees of the British East India Company, and even the Christian clergy – all British of course – was facilitated by the enactment of infamous Crown Lands Ordinance of 1840 and Ordinance No.9 of 1841.

The implementation of the above acts enabled prospective planters and investors, to literally invade and acquire any land they considered suitable for coffee, irrespective of its original status. This resulted in village farmers being dispossessed of cultivable land and many areas of the central hills and other heavily forested wet-zone provinces, being denuded

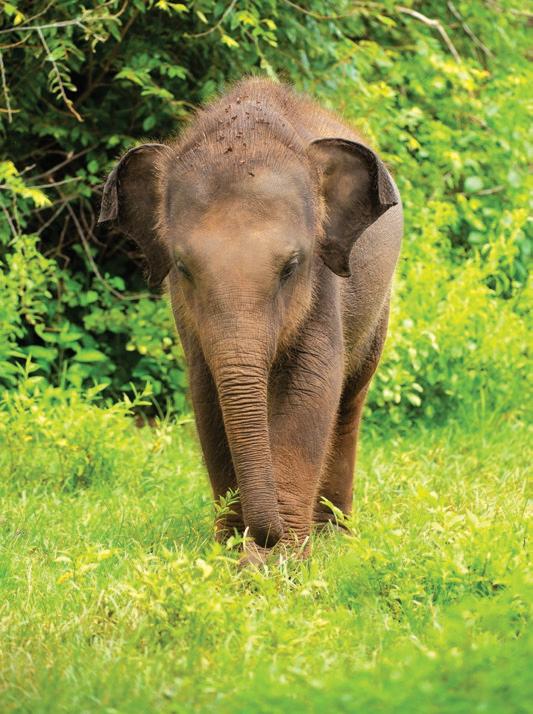

of their virgin forest cover. Whilst the British created the opportunity for valuable export crops – which still serve the country well – first for coffee and then tea and rubber, it was at tremendous cost to the environment and its fauna, flora, animal habitats, and watersheds. Equally affected were the traditional village communities in those areas, which were heavily reliant on well-balanced eco-systems to sustain traditional life-styles and livelihoods, harmonious with the natural environment.

When morning broke... I found myself gazing upon a scene not altogether unfamiliar to me. All around me lay hundreds of black charred logs, stumps in fantastic shapes and outlines; fallen branches, broken and distorted by fire; cinder heaps, and little rivulets of sodden ash; all indicative of the fierce, merciless fire that but a few weeks ago had been a beautiful forest land (‘Sixty Four Years In Ceylon’ – Frederick Lewis, 1858-1923, British Coffee Planter, Forest Officer, and Surveyor in Ceylon), on witnessing the carbonised remnants of the montane forest which later became Alton Estate, Upcot; first planted in coffee and then in tea)

Amongst the first British coffee planters, George Bird (1792-1857) stands out as the owner of the first successful commercial plantation, located in Sinhapitiya, close to Kandy, in the 1820s. He was followed by Scotsman Robert Tytler (18191882) who brought with him his experience of West Indian coffee culture.

Following the example of the British coffee pioneers, a few wealthy Ceylonese businessmen too invested in the crop. Foremost among them was Jeronis de Soysa (1797-1862), followed by his son, Charles Henry de Soysa (1836-1890), who expanded the land holdings and businesses inherited from his father. The latter is still remembered for his great philanthropy, especially for his contributions to public health, school education, and institutions for agriculture.

Coffee had been grown in Ceylon for several decades by native peasant farmers, but as a subsistence crop and not on large commercial-scale plantations. The advent of the British plantation entrepreneur,

elevated what had been smallholder occupation, to the level of a massive export production enterprise.

With the impetus provided for its cultivation by the British Colonial Government, by 1870, coffee production had spread to about 275,000 acres and Ceylon had become the third highest producer in the world, behind Brazil and Indonesia. It was also the primary source of income for Ceylon’s Colonial Government. However, around that time, a fungus disease, later classified as “Hemeleia Vastatrix,” or Coffee-Rust, made its appearance, literally unnoticed. Within a decade it had spread, country-wide, and without an effective antidote, decimated the national industry. Plantations were abandoned, workers were left destitute, planters and administrators lost employment, and offices closed down, whilst a multitude of companies officially declared bankruptcy.

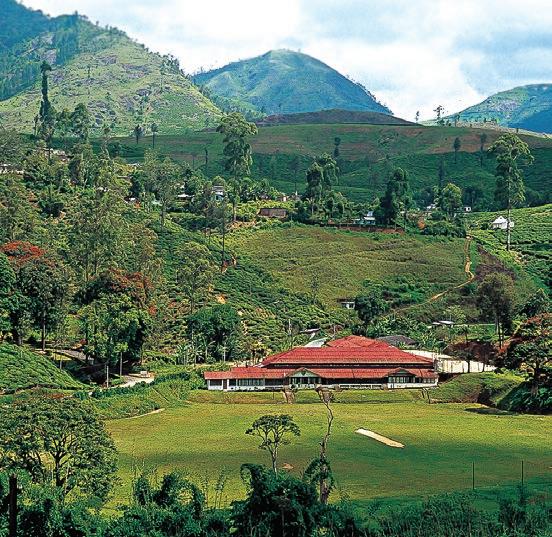

Whilst there are obscure and not easily verifiable references to tea in Ceylon, dating back to the second decade of the 19th century, an indisputable starting point would be 1839, when the Royal Botanic Gardens at Peradeniya received a consignment of seeds from Dr. Wallich, eminent botanist and curator of the Calcutta Botanic Gardens. In February that year, there was another lot of 205 plants, of which a few had been sent to Nuwara Eliya, a region in the central hills with elevations ranging from 1,500 to 2,500 metres above sea level. Again, in April 1842, part of another consignment of the Assam variety from Dr.

Wallich had been sent to one Mooyart of Nuwara Eliya. That lot had been planted on land in Nuwara Eliya, belonging to Sir Anthony Oliphant, then Chief Justice of Ceylon. According to Rev. E.F. Gepp, tutor to Sir Anthony’s son, the planting may have been in the vicinity of the subsequently constructed (1893) Queen’s Cottage – now President’s House – of Nuwara Eliya.

Maurice and Gabriel Worms, both of German-Jewish origin, two pioneering coffee planters of Pussellawa, are also associated with early experiments with tea planting in Ceylon. Maurice had apparently returned from a trip to China in 1841 with a few rootlets or cuttings of tea and planted them on Rothschild, Pussellawa, then a flourishing, mid-elevation coffee estate, about 40 km below Nuwara Eliya. A field on Condegalla division of Labookellie Estate, Ramboda, in close proximity to Nuwara Eliya, is also said to have been planted with a few tea plants during the same period. Apparently, a retired Assam tea planter, W.J. Jenkins, had carried out experimental manufacture from the tea on Condegalla.

Emerson Tennent (1804-1869), British Colonial Secretary and historian of Ceylon, in his book ‘Ceylon’ (first published in 1849), refers to a thriving tea field on Rothschild: “when I saw them they were covered with bloom”. Concurrent with the Worms brothers’ episode, there is a report of one Llewellyn of Calcutta, planting tea on Pen-y-Lan Estate, Dolosbage. This is verified later by A.M. Ferguson, reporting on the existence of large tea trees on Pen-ylan, during a visit made by him in 1885.

Another reference comes from Uva, a large, mountainous province in the Eastern part of the country, with one James Irvine of Kottagodde Estate, Badulla, claiming to have maintained a small field of tea planted by one A. Bartlin, possibly an early British owner of the estate, at a period prior to 1870.

Similar to the above, there are many other tantalising titbits of tea-related information from various parts of the island, relevant to the period, 1840-1867. However, there is no reliable evidence of the survival of plants from any of the above experiments.

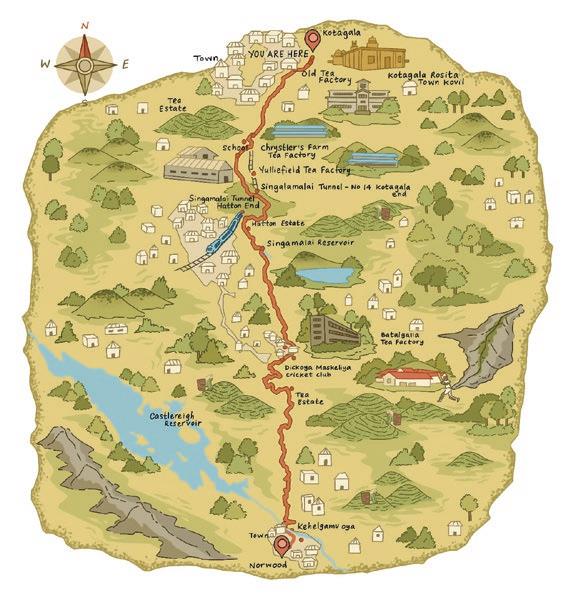

In October 1851, James Taylor, a 16 year old Scottish youth from Laurencekirk, Kincardineshire, signed a contract with Messrs. G & J. A. Hadden of London, estate agents, committing himself to a three-year plantation engagement, with Englishman, George Pride, coffee estate owner of Kandy, Ceylon. Taylor boarded ship in London on 23rd

October, accompanied by his mother’s young cousin, Henry Stiven, also a plantation recruit, and arrived in Ceylon on February 2th, 1852.

After a few weeks on Naranghena Estate, Hewaheta, Kandy District, he transferred to Loolecondera, a mid-elevation coffee estate in close proximity. Over the next couple of decades, Taylor was responsible for the successful planting and production of coffee on that property.

By about 1880, the collapse of the coffee industry had become inevitable and many planters commenced experimenting with other crops. One was cinchona, the bark of which was used in the production of quinine, a medicine for malaria. However, it soon became clear, that cinchona, despite being an effective prophylactic, was not a commercially viable replacement for coffee.

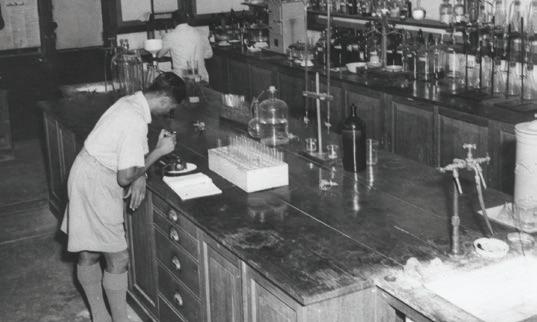

In the meantime, Dr. George Thwaites(1812-1882), Superintendent of the Peradeniya Botanical Gardens, had been experimenting with tea cultivation in the gardens itself. In or around 1864, on his own Taylor appears to have experimented with a few tea plants, set down along the roads within Loolecondera. In 1868, Taylor cleared 20 acres on field no:7 of Loolecondera and, with seeds obtained from Thwaites, planted the area with tea. The first effort had failed but a second planting in 1869 had

been successful. It is recorded that Taylor sent a lot of 23 lbs of Black Tea, manufactured from his leaf, to London, in 1872, the first commercial consignment from Ceylon. That tea field, protected as a museum piece, still produces Black Tea on a commercial scale.

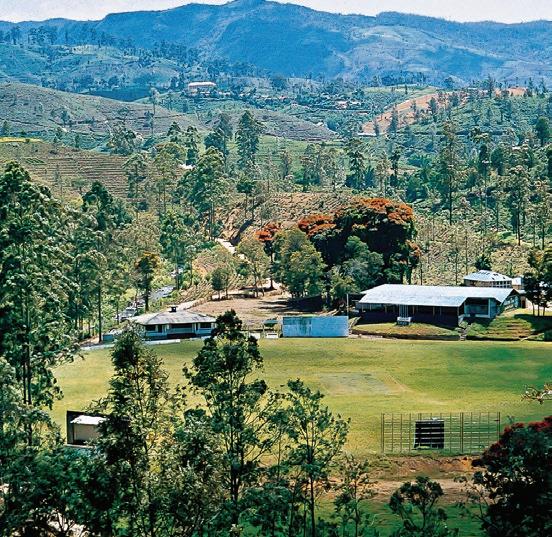

Other planters, encouraged by Taylor’s success and, also, driven by the desperate need for an alternative to coffee, commenced large scale tea cultivation, firstly in the hills of the central province, using the infrastructure which had supported coffee. Tea plantations soon became wide-spread in the upcountry districts and quickly moved down to the low-country, eventually establishing a significant presence in five out of the nine provinces.

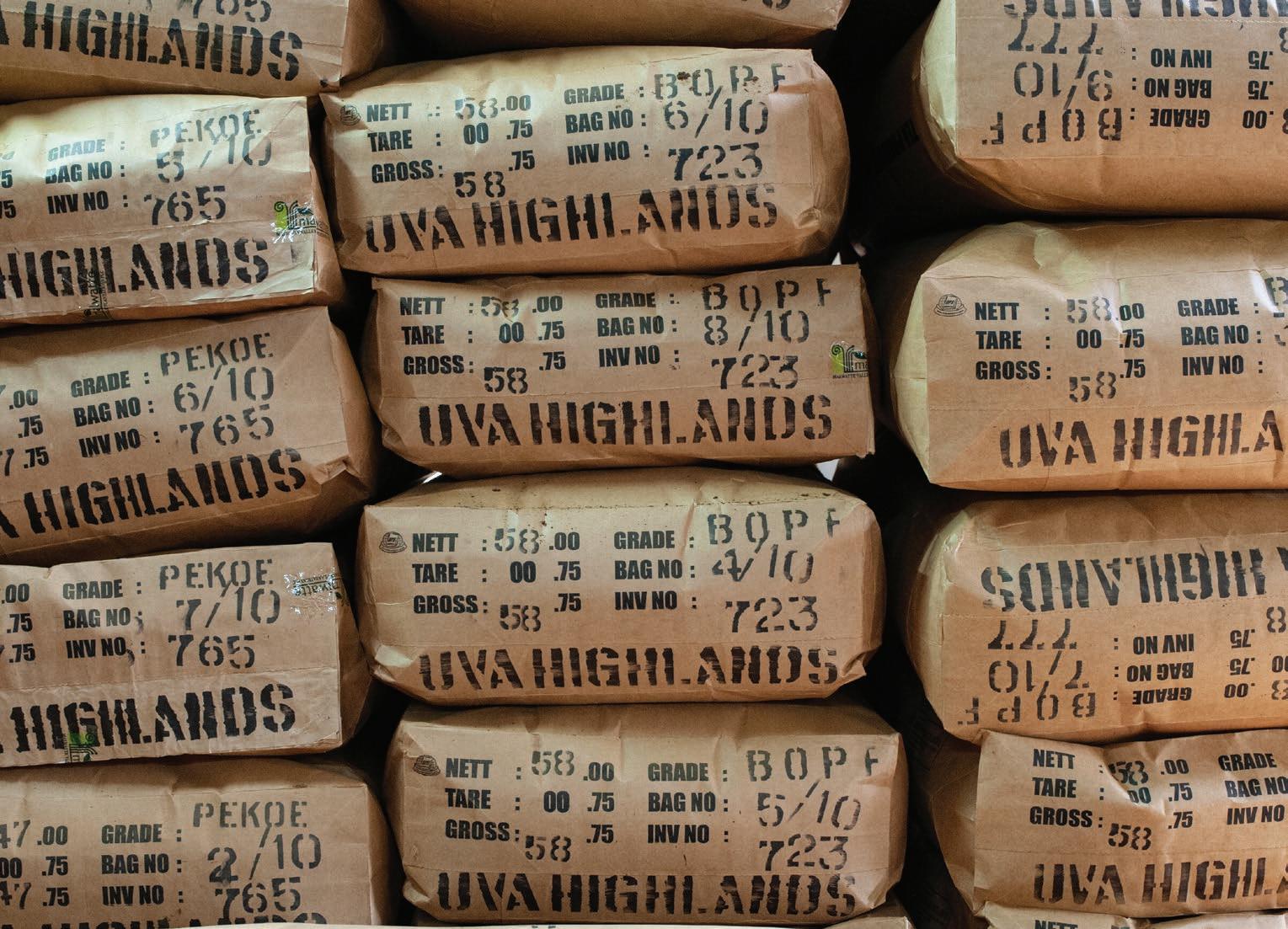

By 1900, the extent under tea had increased to 120,000 hectares (296,400 acres) and the annual national production to 69,000 metric tonnes (151,800,000 lbs). Today tea covers around 200,000 hectares (440,000 acres) and the average annual production is around 300 million kg (660 million lbs).

An industry built on the wreckage of another soon acquired a pre-eminent position, as the country’s biggest revenue earner.