responsibility as citizens, and on ethical practice.

we live in the world, with an eye on our environmental

globally connected, growing knowledge to reframe how

responds to these core ideas by being intensely local whilst

and TNE activities. Leicester School of Architecture’s identity

partners, through its award winning DMU Global initiative

understanding of place and people with our international

It is a vibrant and ambitious institution, sharing its local

into Leicester City’s social and physical infrastructures.

De Montfort University is a civic university embedded

of Architecture

Leicester School

2021

THE FACULTY OF ARTS DESIGN & HUMANITIES

The Leicester School of Architecture Contents

2021

Contents 2021 Introduction P.10-11 Kate Cheyne, Head Of School Architecture The Leicester School Of Architecture P.12-13 MArch Architecture P.14-15 Ben Cowd, Programme Leader Unit One / Wild City, Ben Cowd, Tim Barwell P.16-55 Unit Two / States Of Verticality, Dr Yuri Hadi, Lena Vasilev P.56-123 Unit Three / Material Futures, Alexander Mills, Danielle Fountaine P.124-147 Unit Four / Making Waves, Tom Hopkins, Rory Keenan P.148-177 Unit Five / Spatial Figures, Ashley Clayton, James Flynn P.178-211 Comprehensive Dissertation, Dr Jamileh Manoochehri P.212-227 BA Architecture P.228 Neil Stacey, Programme Leader Ba Architecture, Year Three P230-231 The Dark Factories P.232-245 Studio Dna / Frank Breheny, Sylvester Cheung P.246-255 Co-Existance In Theory / Dan Farshi, Jee Liu, Jamie Wallace P.256-295 Handmade Cities / Jon Courtney-Thompson, Andrew Waite P.296-319 Symbiote / Geraldine Dening, Neil Stacey, Lena Vassilev

Ba Architecture, Year Two /

Megahed

Ba Architecture, Year One / George Themistokleous

Architectural Technology P.366-379 Dr Luis Zapata, Programme Leader The Architecture Research Institute P.380-383 Prof Ahmad Taki Our Programmes P.384-388 Academic Staff 2020/2021 P.389 Editor, Art Direction & Design Dr Yuri Hadi ISSUE 4, 2021, Leicester School of Architecture Showcase Book All rights reserved. No part in this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any mean, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of DMU.

P.320-343

Yasser

P.344-355

P.356-365

LSA2021 10

THE SCHOOL

OF ART DESIGN & ARCHITECTURE

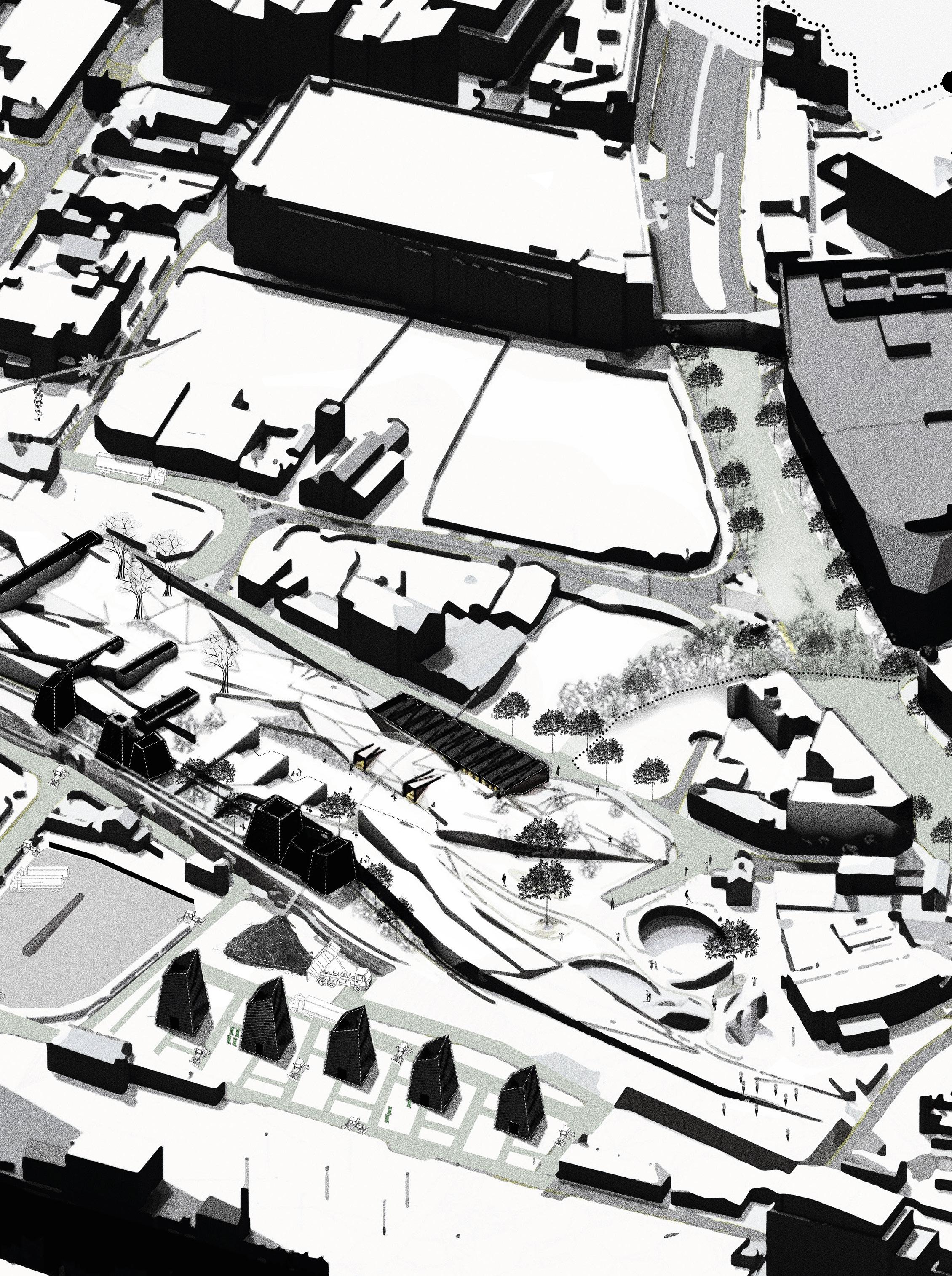

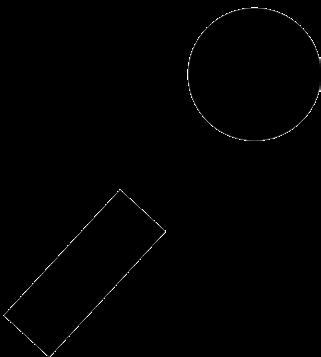

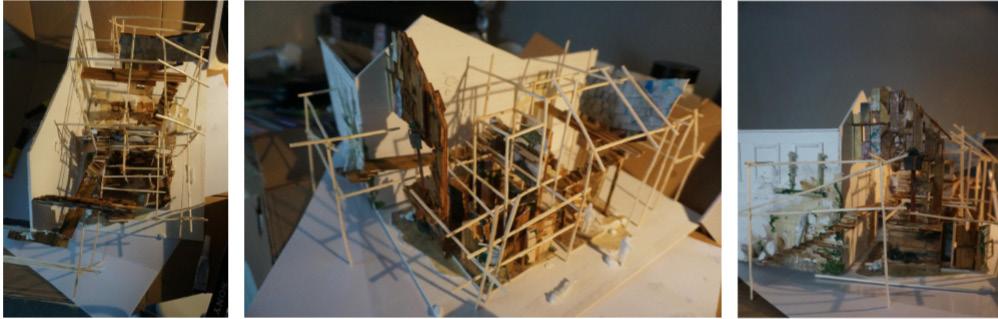

Opposite: Jan Moore, MArch, Year 5, Ruincarnation.

Welcome to Leicester School of Architecture 2021 Degree Show Book. 2021 continued to be a year which asked great maturity and resilience from our students. The anticipation of returning fully to campus and face-to-face teaching was shortlived, but newfound ways of teaching and learning through an on-line community have been enriched and expanded with some unexpectedly positive results, including the opportunity of hosting an international lecture series with architects and academics zooming in to Leicester from around the world.

We prepared for the expectation of a second lock-down with LSA’s academic community being asked to set projects that were intensely local whilst globally connected, growing knowledge to reframe how we live in both East Midlands, and the wider world. All programme briefs, from architecture (Part 1,2, 3 and Level 7 Apprenticeship) through to architectural technology and quantity surveying, acknowledge our environmental responsibility as citizens, and the importance of ethical practice. The need to be conscious of accountability has been heightened by the pandemic and the increasing wealth and health gaps. LSA has a diverse student body, reflecting the multicultural nature of Leicester, as well as a significant community of international students. Decolonising the curriculum, alongside embedding sustainability and UN SDGs is part of our commitment to ensure future architects and built environment professionals reflect the UK’s culturally diverse society and bring an inclusive and nuanced response to all of society’s needs when responding to the climate crisis we are living in. The evidence of this commitment is that all studio briefs address Spatial Justice.

Our students are supported by tutors that are leaders from industry, practice and research. Learning is extended throughout our lives, and our community is seen as a place where academics, practitioners and students are co-designing new ways of thinking while maintaining the highest standards in terms of ethics and integrity. Staff experience and knowledge combined with the students’ openness allow us to challenge existing conventions, redefining our subject, as we teach students to discover that architecture and construction is not only about a building but a vehicle for living, plugged into wider ecologies and social networks. LSA believes that the need to develop an ethical construction industry is central to the future of architectural practice. As the industry shifts away from large carbon emissions, poor quality construction, excessive construction waste and unsafe working practices, LSA is ambitious in wanting to lead in tackling the Climate Emergency and the need for Spatial Justice for all.

The students’ projects you will see here reflect our ethos of the work needing to be relevant to contemporary issues, addressing social and cultural conditions whilst also being visually and aesthetically mature and critically engaging.

Kate Cheyne Head of School of Art, Design & Architecture

(ADA) 2020/21

LSA2021 11

The Leicester School of Architecture

De Montfort University (DMU) is a civic university embedded into Leicester City’s social and physical infrastructures. It is a vibrant and ambitious institution, sharing its local understanding of place and people with our international partners, through its award winning #DMU Global initiative and TNE activities. It is the educational global lead for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (UNDG) number 16 - supporting peace, justice and strong institutions and leading the #jointogether Partner Universities. Leicester School of Architecture’s identity responds to these core ideas by being intensely local whilst globally connected, growing knowledge to reframe how we live in the world, with an eye on our environmental responsibility as citizens, and on ethical practice.

Cross-disciplinary Education

Leicester School of Architecture (LSA) was established in 1897, as part of an Arts College with Architecture taught alongside other building-related crafts and trades. This tradition of a collective understanding of ‘learning through making’ remains central to the School. LSA became part of a new School of Art, Design and Architecture (ADA) in 2019, sitting in a Faculty of Arts, Design and Humanities and exchanging ideas with the School of Fashion & Textiles and School of Humanities and Performing Arts. This allows us to build on our arts and crafts history by placing inter-disciplinary thinking and collaborations central to the School. We show how different disciplines can positively disrupt one another, revealing new ways of seeing, thinking and making.

Civic Engagement

Programmes in ADA span from architecture (Part 1,2, 3 and Level 7 Apprenticeship), architectural technology, surveying and interiors, across design crafts and design products and into photography, video and fine arts, with a nationally respected Arts and Design Foundation course as a pathway into these degree programmes. All courses are housed in the RIBA award-

winning Vijay Patel Building, sited within Leicester City. Our public facing Leicester Gallery showcases the work of students and staff to our wider community of Leicester, alongside international recognized artists and designers. This physically underpins our ethos of being a civic School of Art, Design & Architecture embedded in society, and ensures architecture students arrive with an understanding of the importance of designing for place and people.

Tradition of Making

The Vijay Patel building was designed with state-of-the-art workshops, offering cutting-edge digital fabrication facilities alongside a wide range of specialised craft workshops, where students can learn, experiment and innovate with materials and processes, alongside students from other disciplines. Embedded into the act of making is the need to understand material cultures and circular economies through ethical choice of materials and reduction in waste. It is a dynamic and multidisciplinary environment that supports one of the School’s tenets that the exploratory process of making the work is as important as the final piece. Students are encouraged to design through experimenting and testing

LSA2021 12

ideas with drawing and making as well as writing, reading and discussion. The facilities support our strong tradition of excellence in teaching (TEF Gold) underpinned by world-class research and strong industry links in the professional fields of architecture, construction, urban design and environmental design.

Local Impact

Our LSA community is seen as a place where academics, practitioners and students are co-designing new ways of thinking and meaningfully challenging conventions to redefine the future of practice. In architecture, our academic body includes a substantial number part time lecturers who teach alongside practice. They represent the regional creative community so that we can work closely with local stakeholders such as Leicester City Council (Heritage Action Zone), LCC Planning Department (Urban Observatory & future Urban Room), the National Forest (Live Projects), LCB Depot (Design Season), RIBA East Midlands (Education Forum), UKNewArtists (Leicester Takeover), Leicester and Rutland Society of Architects (Love Architecture) and #DMU Local (a university volunteering programme) to evolve briefs with a long lifespan that are relevant to our region and showcase the work widely through public facing exhibitions and talks. This allows us to design courses that prepare our students for the changing nature of the profession and its responsibilities and teach them to be bold and fearless in creatively exploring their ideas.

Global Application

LSA delivers an advanced enquiry-led education, designed to prepare and challenge students to take a personal and critical position in the globalised architectural world. We have an international academic community with 50% of our substantive posts being transnational, bringing a global perspective to architectural education. We support students to engage with the world through our #DMU Global project, subsidising students to attend global study trips. These have included studio field trips to Berlin, Dubai, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Ahmedabad, with many being active learning opportunities embedded into studio briefs. In 2021, De Montfort University announced the commencement of graduate and undergraduate programmes in its new Dubai Campus, which coincides with participating in the Dubai Expo, where our M.Arch students are showcasing work, responding to Spatial Justice and the UN Human Rights agenda. This will support our growing Trans National Educational opportunities out in China, Sri Lanka, Jordan, Thailand and Malaysia.

Research-led teaching

Our research at DMU is underpinned by the aspiration to better understand and improve social justice. The way the built environment is designed and managed shapes the distribution of resources, the efficiency of their use and the long-term sustainability of the communities that depend on them. LSA therefore explores social and spatial histories and proposes

innovative, sustainable architectural solutions to contemporary environmental challenges in order to create a just and equitable society with a more even distribution of resources. Both academic and practice-based research are folded into our teaching through offering design studio briefs that respond to our academic community’s depth of knowledge within the discipline; and our M.Arch studios are seen as studio laboratories where students, academics and practitioners evolve knowledge together.

Diverse

We have a diverse student body, reflecting the multicultural nature of Leicester, as well as a significant community of international students. Decolonising the curriculum, alongside embedding sustainability and UN SDGs, is part of our commitment to ensure future architects reflect the UK’s culturally diverse society and bring an inclusive and nuanced response to all of society’s needs when responding to the climate crisis we are living in.

Ethical

Students are supported by tutors that are leaders from industry, practice and research. Learning is extended throughout our lives, and our community is seen as a place where academics, practitioners and students are codesigning new ways of thinking while maintaining the highest standards in terms of ethics and integrity. Staff experience and knowledge combined with the students’ openness allow us to challenge existing conventions, redefining our subject, as we teach students to discover that architecture is not only about a building but a vehicle for living, plugged into wider ecologies and social networks. LSA believes that the need to develop an ethical construction industry is central to the future of architectural practice. As the industry shifts away from large carbon emissions, poor quality construction, excessive construction waste and unsafe working practices, LSA is leading in tackling the Climate Emergency and the need for Spatial Justice for all. Students’ projects reflect our ethos of the work needing to be relevant to contemporary issues, addressing social and cultural conditions whilst also being visually and aesthetically mature and critically engaging.

LSA2021 13

Master of Architecture

MArch Architecture/Full Time- Part Time

Our MArch Architecture programme delivers an advanced enquiry-led education, designed to prepare and challenge students to take a personal and critical position in the globalised architectural world. Our community is seen as a place where academics, practitioners and students are codesigning new ways of thinking and meaningfully challenging conventions to redefine the future of practice. As an integral part of its structure, it includes regular contributions from specialist academics from other departments and institutions, as well as consultants from allied professions. Prominent practitioners are also brought in to contribute to teaching and to monitor the performance of the programme, evaluated against national standards.

At the start of the programme, students are presented with a series of options through which they can tailor their MArch1 studies. Studio options are presented, as well as options for HT&C modules to enable the student to decide a personal stream of study that aligns to their particular interests. MArch 1 and MArch PT1 studios are conceived as design-laboratories; the focus of which is skills building, exploration, and experimentation, informed by dialogue concerning application

of design theory/position to architecture and the significance of building/being-in-the-world. The testing of ideas is expected to make extensive use of the workshops such that the student is able to articulate ideas in physical form to complement their digital/artistic representation and verbal explanation. Each studio will entail a field trip(s) to sites that have complex historical/geographical contexts and provide a rich basis for students to test and develop the skills developed in Design 1, in a context themed project for Design 2. Having chosen a site, under guidance, students will produce a full survey and physical/environmental/historical/social analysis, together with a fully researched project brief for a simple building/project and feasibility/conceptual studies for Design 2. This is then developed into a completed design that explores both internal and external materiality and arrangement in detail, as well as advanced presentation techniques.

In MArch 2 and MArch PT3 students will choose their tutor for the year long investigation at the beginning of the academic year. Each Tutor defines a particular interest or focus that the studio group will follow and within this intellectual framework the student will propose his/her personal investigation

LSA2021 14

States of Bold Poetic The

Wild City

Urbanicity

Sensitivities

to carry out. Some tutors may offer a particular city with optional sites to be investigated, whilst other tutors may open the site selection process but ask for a particular condition to be investigated. The goal is to create a critical dialogue between students and tutors that informs the design process, a process which builds on skills learned in Design 2. For the Comprehensive Design Project, students are invited to research, choose and propose a brief for a building (s). Approval must be attained to assure that the proposal accommodates a level of complexity expected for Design 3.

The proposal is submitted at the beginning of MArch2 and MArch PT3. Design 3 and the CDP are designed to integrate the techniques and skills acquired by the students throughout their previous architectural education into a major final design project. They carry out a detailed analysis of their sites in a wider context, using techniques learned in Design 2, and then make proposals for a building that illustrate a theoretical approach, using their HTC and Comprehensive Dissertation studies, as well as technical and professional knowledge gained in their first degree and placement year. In summary, the first academic year of the programme MArch1 and MArch PT1: uses

complex context to train the students in urban analysis and design, and introduces them to advanced theory, as well as widening their design horizons. The final academic part of the programme MArch1 and MArch PT2 & 3 :integrates this training by applying it to the Comprehensive Dissertation, Design 3 and the CDP, which at the same time allow maximum usage of student initiative and choice, producing a coherent synthesis of the various elements of the course.

LSA2021 15 Year 4- Advance Upper Year 5- Advance Final

PROGRAMME

BEN COWD

LEADER

Ben Cowd

Tim Barwell

Yuri Hadi

Lena Vasillev

Alexander Mills

Danielle Fountain

Reclamation

01 02 03 04 05

Thomas Hopkins Rory Keenan

LandUse_

Ashley Clayton James Flyn

STUDIO one

The Wild City

“I don’t want you to be hopeful. I want you to panic. I want you to feel the fear I feel every day. And then I want you to act. I want you to act as you would in a crisis. I want you to act as if our house is on fire. Because it is” Greta Thunberg at Davos, 2019

Studio 1 is interested in an architecturethat expresses the process of design, revealing the cuts, revisions and scares of iteration, seeking new forms of architecture, generated by current and future contexts and questions. The result of this expressive process is an architecture that is specific yet inherently adaptable to change and future mutation: Unafraid of time, decay and weathering, able to resonate at multiple scales and co-exist alongside nature and our environment. This year, we continue our research into biodiversity in cities and

Year 5

Year 4

how architecture can respond creatively to the extinction and climate crisis. In the UN Report: Natures Dangerous decline, Sir Robert Watson describes that ‘the health of ecosystems on which we and all other species depend is deteriorating more rapidly than ever. We are eroding the very foundations of our economies, livelihoods, food security, health and quality of life worldwide ...1 million animal and plant species are now threatened with extinction, many within decades, more than ever before in human history’. This is a global crisis, however the UK is one of the worst performing countries, “the UK has lost significantly more biodiversity over the long term than the world average. Ranked twenty-ninth lowest out of 218 countries, we are among the most nature-depleted countries in the world.” State of Nature Report (updated 2016) We begin the year with the science in mind and ask ourselves how architecture must adapt to provide increased habitats for nature. How can architecture change and transform from being a destructive force, to being a provider for plants, insects, birds and mammals capable of inhabiting our cities and streets? How will our habits and every-day life need to shift to meet these sustainable targets and accommodate a more bio-diverse environment?

LSA2021 17

Ben Cowd Tim Barwell

Rahul Baria Stephan Bevan Abu-Bakr Desai Donia Rose John Paulina Alicja Owczarek Adam Lamido Sanusi Chloe Walpole

01Opposite: M1.01, Sam Sandercock Sociable Housing For The Lonely, Leicester.

Aminah Althuwaini

James Evans

Amina Faizal Osman

Louis Holwell Karen Isaac

John Francis Javier Marasigan Nur Hazira Mohd Zahari Can Ozerdam

Sam Sandercock Flora Zejnulahi

SAM SANDERCOCK (Y5)

“Sociable Housing For The Lonely ” Loneliness can affect anyone in their life; however, it was important to understand who it affects the most in order to allow the project to work for them. This project is set to produce an elderly peoples’ home and so the addition of other age groups will become beneficial to provide a multigenerational dwelling complex aimed at allowing different generations to learn and develop from one another.

AMINAH

ALTHUWAINI

“The Waste Mountain”

(Y5)

Waste Mountain explores the philosophy of taskscape that is introduced by Martin Heidegger, developed by Tim Ingold. It is a project that evolves through time, turning wastes into a wild landscape. The aim of this project is to merge the landscape with public spaces, making Leicester wilder in terms of social density and developing a green city.

JAMES EVANS (Y5)

“The

Bio-Convalescence Project”

The Bio-Convalescence project is a recovery centre for those suffering physical or mental disabilities, surrounded by a rewilded forest landscape in the southern part of Leicesters’ ring road. This site is in close proximity to the Leicester Royal infirmary and intends to offer a haven for those coming from the hospital, for short-term or long-term stays.

LOUIS HOLWELL (Y5)

“The

BioSkin Project”

The BioSkin Project encourages an appreciation of nature and helps to remind us of its benefits, something that we all found very enjoyable during our ‘one hour’ of outdoor exercise during the heights of lock down, was a walk, jog or run outside. Each home in the BioSkin has their own private outdoor space that everyone no matter their situation can experience time outside and can therefore benefit from mental boast for mental health.

CAN OZERDAM (Y5)

The Zone: A Contaminated Landscape“

A project that aims to challenge the growing issues that involve soil contamination within Beaumont Leys, with hopes to introduce natural remediation such as Phyto-remediation and improve the quality of life in the area as well as provide a new housing scheme that will assist in the search for environmental justice.

AMINA FAIZAL OSMAN (Y5)

“Dance+Nature”

Dance and Nature is a project that celebrates the idea of dance spaces in between a housing complex next to Leicesters’ Golden Mile. The Golden Mile is an area rich with British Asian history and culture. The complex translates dance movements into abstract forms that aslo provides healing garden spaces.

KAREN ISAAC (Y5)

“Community Garden and Social Elderly Housing”

The initiation of the project posed fundamental questions, regarding which area of the ring road would be chosen for transformation? What is an environmental weave and how would it be formed? How could an existing cultural weave create an adaptable architectural weave that would support the elderly community within the area?

JOHN FRANCIS JAVIER MARASIGAN (Y5)

“Meta-Living”

A percentage of people suffer from their own mental health caused by an external matter. A sense of habit, routine, emotional and physical being affects one mental state to a downward spiral that feels uncontrollable. This project looks at alternative means of healing through design and Architecture.

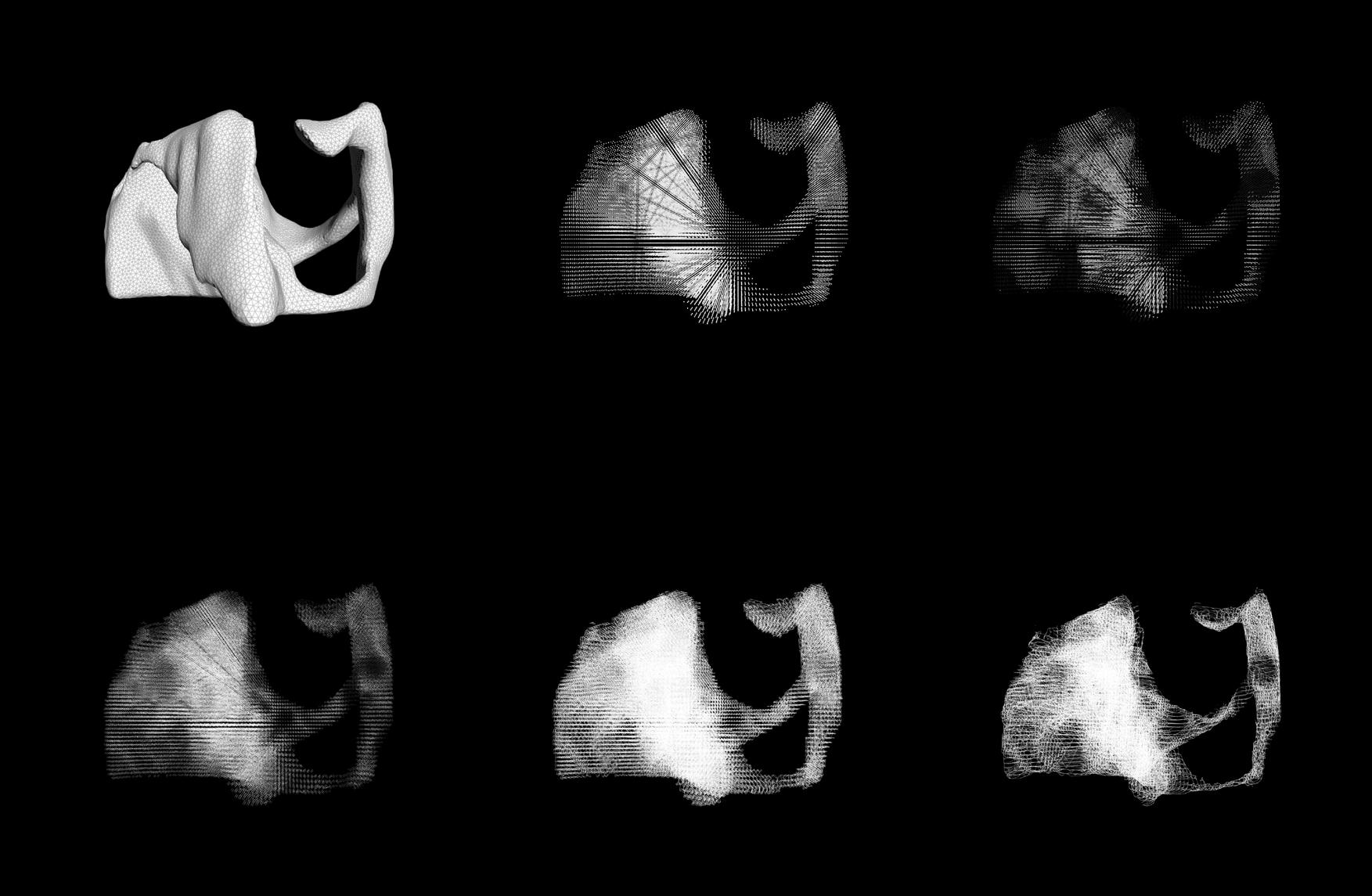

NUR HAZIRA MOHD ZAHARI (Y5)

“Eden Wellness Centre”

A project that looks a Biophilia Design by experimentative iterations of the patients mental state as a catalyst for designing spaces that enhances the sensory dimension.

FLORA ZEJNULAHI (Y5)

“The Stadium of Life” Sports and nature work hand-in-hand together, why not bring them together and to create a biophilic sports centre for Kosovos new tomorrow? Kosovo is the most recent independent country in Europe, it also has the youngest population. This project looks at how biophilic architecture and sports could create better opportunities.

DONIA ROSE JOHN (Y4)

“Leicester Children’s Hub”

A designed programme is aimed at improving the health and well-being of children and providing them with equal opportunities in the city of Leicester. The current state of the city centre does not provide any importance to the younger generation as it is mainly populated with small and large scale businesses and industries.

PAULINA ALICJA OWCZAREK (Y4)

“States of Decay”

A project that investigates what could happen when our environment is left to decay wihtout human interference for a given period of time. How could it be possible to salvage, re-use and develop our dwellings and workplaces in this exemplary reality?

ADAM SANUSI (Y4)

“City Re-Wilding- Leicester”

This project is aimed to provide a solution for the problem of Leicesters’ carbon emissions. The aim is to reduce overall carbon emmissions in the city while providing a possible solution for housing.

CHLOE WALPOLE (Y4)

“Wild Nursery”

The brief for the Wild Nursery is a tangible piece of architecture which responds to its climate and surroundings. The Wild Nursery is produced in response to the climate crisis, to aid and educate the children about the impacts this will have on their future.

ABU BAKR DESAI (Y4)

“Food!”

Food defines who we are and where we come from. The Food Port provides a comprehensive survey of the food industry and its processes while relocating many food programs typically separated from the buyer back into the heart of the city. It defines a new model for how the relationship between consumer and producer can be defined and addresses uncaptured market demand and inefficiencies within the local food industry.

RAHUL BARIA (Y4)

“Wild Skin”

The design that will encourage the biodiversity of birds and insects to thrive on the series of weaving skin platforms that can feed on the flowers and other plants. The design includes a flexible skin which was inspired by the formation of sunflower seeds and how they envelope the patters with the flower.

STEPHEN BEVEN (Y4)

“St Margaret’s Gardens”

St Margeret Quater in Leicester is an abandoned industrial site dividing the city centre and the river Soar. This project looks at complex layering of history to create a botanical reserve that acts as a research centre and public space for the city of Leicester.

LSA2021 18

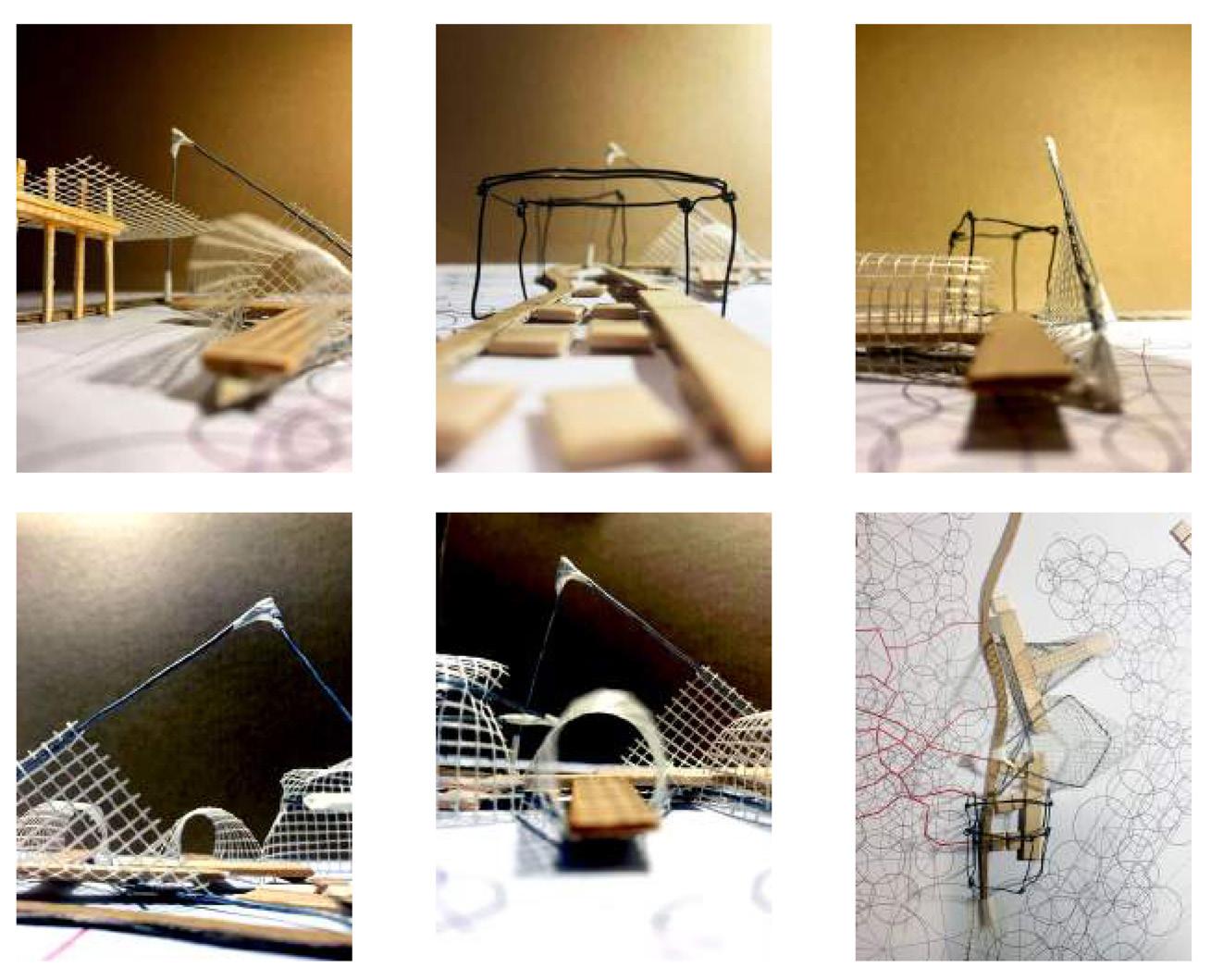

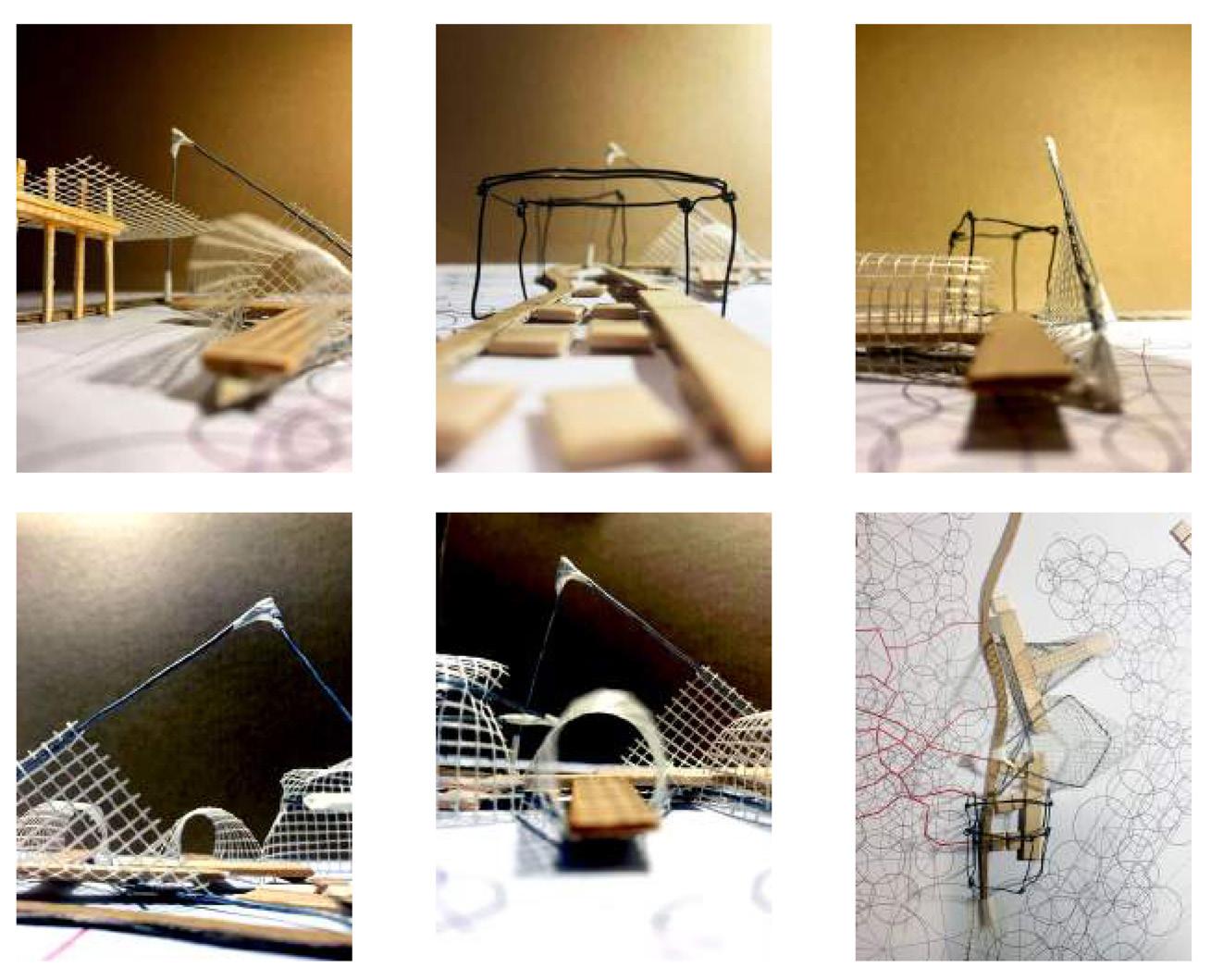

M1.02 Sam Sandercock (Y5) - Process Model, Sociable Housing for The Lonely

M1.02 Sam Sandercock (Y5) - Process Model, Sociable Housing for The Lonely

M1.03, Layered model of community space to demonstrate the permeability of the structure.

M1.04, View Entering the site from St. Georges Way. With the vast amount of different plants being grown around the site, this will create a diverse range of habitats that will encourage a wider range of biodiversity of nature to inhabit the site as well as the people that move in. With the large site to occupy and food sources along with the reduction in road traffic, the animals will have a safe habitat to live.

LSA -

24

2021

M1.05, Visual representation of the communal dining space where residents can cook and eat meals as a group allowing for the enjoyment of self-grown produce as a community.

M1.06, Visual representation of the walkways and how residents can enjoy heing in company of their neighbours sat out in the dining space between flats and with the people walking past.

M1.07, Planting Species Plan: Using the stepped contours planned out where plants will be and what species will be used to help encourage certain wildlife to the site.

LSA2021 25

26

M1.07, Plan roof explorations of the Second Community Area.

M1.09, Sectional Views through Community Spaces.

M1.10, Isometric View of Second Community Area.

LSA2021

LSA2021 27

M1.11

M1.11, The First Community Area, M1.12, The Second Community Area.

M1.12

AMINAH ALTHUWAINI (Y5) “The Waste Mountain”

The human lifestyle is based on a series of tasks, fulfilled in space. With time, these tasks manifest and form different errands. Many factors allow these changes to happen that could be associated with psychological, political, and ecological instances that can affect a persons’ movement through space. Architecture can also affect the way in which human tasks are performed. For example, a library is a place where people read, however, other activities could be explored such as scanning and printing. Similarly, green landscapes bring opportunities that could explore a variety of tasks. This project explores the philosophy of taskscape that is introduced by Martin Heidegger, developed by Tim Ingold. The way in which this project will progress is to design the landscape first, to drive peoples’ desires. The second stage of the project is to merge the people with the landscape. The aim of this project is to merge the landscape with its users, making Leicester wilder in terms of social density and developing a green city.

M1.12, The Waste Vessel.

M1.13, Industrial Compost Delivery Route.

M1.14, Project Location: Frog Island, Leicester. The location brings opportunity to link the outer skirts of Leicester, towards the city of Leicester. Creating a wilder city through spatial bloom via landscape. Re-using the ring road as a green belt to limit car use and promote physical activity. This will improve the towns’ air quality.

LSA2021 30

LSA2021 31

1- A50 Route

M1.15,Bridging Spaces. The Third phase of the landscape explores a moment of transition towards a more formal event, this is seen with the structure of the promenade.The space also transitions from public to private, limiting human interaction in a the far end (North West) of the site to develop a relationship with wildlife. This key moment might be the far end of the landscape, however, the A50 Route is a key entrance point leading to Leicesters’ city centre. This makes it the first moment upon arrival.

LSA2021 32

2- Connecting bridge to the other side of Leicester 3- The Promenade (for more formal events) 4- River Soar 5- Functional path 6- Waste Vessel 7- Fertilized ground 8- Marshes

1- River Soar

2- Fertilized ground (from compost developed on site)

3- Marshes (where human activity is limited)

4- The promenade (a structure developed for formal use such as staff entrance an a lounge)

5- Compostable structure (material developed from the waste vessels’ compost)

6- Leicester Piazza

7- Leicester & Rutland Wildlife Trust (existing building)

8- All Saints Rd

9- Fertilized ground (from compost developed on site)

10- Access to the site

11- Jarvis St

12- The wild path (functions as a water sprinkler for the site whilst also accommodating plants.

LSA2021 33

M1.16, The Leicester Piazza Area. All Saints Road is transformed into a wild piazza where intergenerational strength comes to life. Both younger and older generations can enjoy the experience of the space to ensure social interaction and develop a scene of creative re-tasking. The journey portrays that midline of maturity where a moment of realisation starts to emerge. The focus of the space is the Leicester & Rutland Wildlife Trust building, where it’s significance flourishes on the opposite side of the Piazza, encouraging wildlife with the marshes.

M1.17, The Industrial Waste Vessels. A larger-scale operation that will allow larger compost production, in order to expedite the landscapes’ growth. Larger vessels are situated at the back of the landscape, allowing access from Jarvis St. the municipal tractors bring in the food waste and drop it into the holes inside the vessels.

M1.18, The Public Waste Vessel, with floral essences surrounding the vessel, the experience of composting is elevated. The material developed for the vessels’ facade is charcoal. It is made out of coppicied wood from Leicestershire woodlands. Charcoal is a material that provides air purification. The use of charcoal as the facade for the vessel will act as a filter to contain the smell of compost to make the peoples’ experience more comfortable and pleasant.

LSA2021 34

M1.19, The landscape in full bloom aromatic flow covers the landscape creating harmony in color. These are the effects of composting. The scale of the landscape indicates the sigificance of food waste as a national problem. To raise awareness and attract people into composting will allow this problem to be reduced and regulated with time. It is important to use architecture and landscape as a language of awareness and realisation thus; the result of composting is reflected on the landscape. This will allow people to understand that a simple task of composting will bring great results, in making the city wild!

JAMES EVANS (Y5)

JAMES EVANS (Y5)

“The Bio-Convalescence Project”

The upsurge of an everchanging urban world is allowing the human population to thrive and expand across the globe. However, this urbanisation has its negative consequences for the natural world. We are in the midst of the Earths’ sixth mass extinction event, the Holocene Extinction. This is the hypothetical end of a majority of species, brought upon by human interference. It is estimated that this extinction rate is happening one hundred times faster than the natural rate, with wild animal populations halved since 1970 (Pearce, 2015)

Our architecture is defined as a habitat for humanity, a constantly growing force of catastrophic change. This requires the adaptation of our architecture and building processest not just to suit the one dominant species, but to provide effective cohabitation for biodiversity. How can our architecture evolve from a destructive notion to a beneficial one?

LSA2021 36

M1.20 M1.21

M1.22, The hopsital buildings for the design flow into the park space in a geometric consistency. The grid for their structure coincides with the forestry grid for the tree planting, becoming much more randomised the further away from the urban area that the project progresses.

M1.23

M1.20, The trees for the forested lanscape are planted exactly 5m apart from one another, allowing the canopies and roots to avoid but cohabit one another. This allows the trees to thrive whilst maintaining the natural density of a forest. M1.21, Patient Transition Process. M1.23, Hospital Connection: Due to the healing aspect of the programme, the building has a direct connection to the L eicester Royal Infirmary. The walkways all flow into the hospital buildings to allow a smooth transition between the hospital to the healing spaces of the Bio-Convalescence project. This allows for limited journey time between the two entities. Furthermore, the walkways from the hospital area break-off to allow the public to move around to different areas of the site and to descend at many different points around the park.

LSA2021 37

LSA2021 38 M1.24 M1.25 M1.27

M1.24 - M125, Due to the high number of trees being planted in the area, there will be some level of change in the growth through time. Each species grows at a different pace, but the building would still provide the necessar y benefits of biophilia in a number of years. In 40 years, all trees should be fully grown, and the building will be at its most advantageous to the surroundings. In the meantime, trees, plants, bushes and vegetation at their early stages would be planted around the building, to reinforce the concept. Planting the new trees and maintaining them can also provide many jobs for the community. M1.26, These elevations show the different levels of recovery around different areas of the building. The project can accommodate for various disabilities regardless of where people need to go. Immersion of these into the forest and habitats allows for a calmer environment for convalescence. M1.27, The walkway is the primary circulation space for the different buildings. Raised on stilts and accessible from a series of ramps and steps, the walkway allows circulation for the public to traverse between the buildings, as well as across and down to the forested environment. The tall timber stilts supporting the walkway create an atmosphere of forested verticality within the natural forest, blending the walkway with the surroundings. The walkway also extends the views out across the canopy as well as across the other levels of the forest.

LSA2021 39

M1.29, The walkway has become one of the defining elements of the project, thus the discussion begins of how this will respond to the surrounding landscape. The elevation of the walkway (above) shows the verticality of the columns responding to the tree trunks creating a manmade forest atmosphere. The walkway axonometrics (below) show the habitats and wildlife around the walkways as well as the aesthetics of the seasonal change.

LSA2021 40

M1.27, Walkway azonometric showing seasonal changes over the forest. Two buildings are the most isolated and private recovery spaces. These buildings are situated amongst the forest landscape at ground level, allowing visitors to fully immerse themselves with the environment. These spaces will be for more physical-based recovery, as the location can encourage exercise and walks in and around the landscape for maximum exposure to nature.

LSA2021 41

M1.28, Walkway azonometric over water showing seasonal changes over the forest: A proposed waterfront offering natural views of the wildlife attracted to the area and the wetland habitat. Water features have relaxation, therapeutic and anxiety-reducing properties therefore this area will be primarily for those in need of mental recovery.

LOUIS HOLWELL (Y5)

“The BioSkin Project”

Leicester is one of the oldest cities in England, with a history going back at least two millennia. It is believed that the Romans arrived in the Leicester around AD 47 during their conquest of southern Britain. Leicesters’ rich history has given rise to a city that is full of varied culture and architecture in its appearance and appeal. Despite is history and the passing of time over hundreds of years, Leicester has managed to maintain many of its initial charms.

However, in the 1960-70s the inner ring road was created. This ring road aimed to give better access around the city and allow people situated outside the city centre the ability to travel in and around the city centre easier. However, our studio group believe that this road has actually separated the city. The road encircles the city centre and has created a separation that was perhaps not considered during its initial construction.

This project is an attempt to create architecture that will not only improve the new ‘Green Ring Road’, but also enhance the lives of the thousands of residents and visitors to this historic city.

LSA2021 42

M1.30

M1.31 M1.33

M1.30, Experiments with colour and form experiments referencing Roberto Murle Marx. M1.31-M1.32, Movement studies of people based on hypotetical characters living in Leicester within the Ring Road and around the site.

M1.33

M1.33, Drawing experiment to better understand the shapes and scale of the identified site. Shapes, and in turn, the negative spaces they left behind create forms.

LSA2021 43

LSA2021 44

M1.34, Train station view.

M1.35, London Road re-wilding.

LSA2021 44

M1.34, Train station view.

M1.35, London Road re-wilding.

LSA2021 45

M1.36, Level 1 residents’ pathways.

M1.38, Conceptual visualisation: Residents’ pathways to London Road.

CAN OZERDAM (Y5)

“The Zone: A Contaminated Landscape”

Perhaps one the greatest challenges of modern society and urban environments are co-produced natural artifical hazards, such as floods, landslides, fires, pollution, or the presence of persistent contamination. These offer frequent challenges to ecologies, cultural and spatial heritage, and residents’ wellbeing. The spaces inhabited by the urban poor bear the burden of such hazards and are particularly vulnerable to these hazards. Indeed, the most contaminated land, or that with the greatest susceptibility to risks, has historically had the lowest land value.

Throughout history, cities have produced different types of waste that they needed to dispose of, and urban policies have usually implied displacing it to the peripheries, affecting the ecologies and environmental qualities of the sites where they settled. Unaware of the consequences of that environment, the settlers of Beaumont Leys remain to live collectively. Over time, however, cities expanded, and what lies beyond the urban borders at one given time may have become part of the built environment a few decades after.

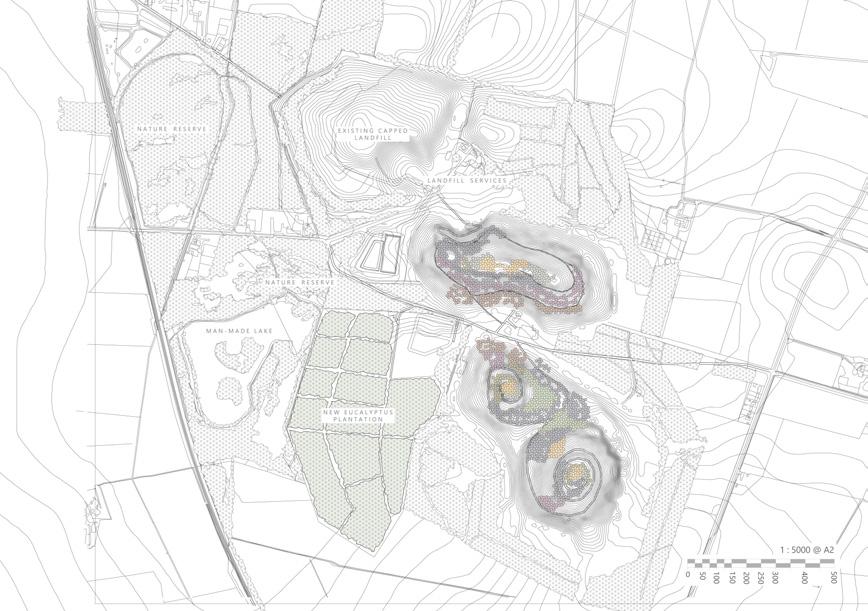

This project aims to challenge the growing issues that involve soil contamination within Beaumont Leys. It also aims to introduce natural remediation such as Phyto-remediation, improve the quality of life in the area, and provide a new housing scheme that will assist in the search for environmental justice.

LSA2021 46

M1.39 M1.40

M1.38, Plant speciment for Phyto-remediation.

M1.40, Reclaimed strategy for dismantling and reconstruction of old houses affected by the population relocation.

M.141, The Zone: A Contaminated Landscape.

M1.42, The Piazza. M1.43, This process of natural, or remediation through nature is named Phytore-mediation. The term Phytoremediation, or remediation by plants, simply describes the degradation and/or removal of a particular contaminant on a polluted site by a specific plant or group of plants. M1.43, The new Beaumont Market introduces a public market which increases access to healthy foods, honor historical legacies, and highlight the local culture of the communities in which they are found. These markets bring together community members, local business leaders, and visitors to celebrate and recognize the importance of this great public space and their roles in helping create communities of lasting value.

LSA2021 48

M1.44

M1.42

LSA2021 49 M1.43

STEPHEN BEVEN (Y4)

“St Margaret’s Gardens”

A vast industrial brown site sits on the western edge of the core of the city stradling along Leicester’s Soar river. Much of the site are industrial wasteland dividing the city between its inner centre to a large patch of residential area outside the city. This project looks at rewilding the area into a public park while retaining its industrial history, preserving some of the abandon artefacts on site.

LSA2021 51

M1.46, Positioning of the site in context to the centre of the city of Leicester. M1.47, City connection Map.

M1.48, Mapping studies on overlaying historical lines and urban form for building proposal.

M1.49, View of the Garfens towards the centre tower, taking form from Victorian Gas holders.

LSA2021 52

M1.49, View of the entrance to the gardens from the walls of St Margaret’s demolished factories.

M1.49 The aim is to promote the connection between the built environment and green spaces of the area using physical connections linking inner city and the green space of Abbey Park, in the form of foot paths and bridges.

M1.49,

M1.49, View of the gardens and gas tower structures from Soar river.

LSA2021 53

The main gardens highlighting the demolished gas towers. The space is a hybrid of public and natural gardens.

CHLOE WALPOLE (Y4)

“Wild Nursery”

Children perceive the world in a much different way than adults. They see an ordinary bookcase as a vast mountainous structure, shelves as an adventurous hike through vines, a table as their own mini home, a chair as a secluded place to read a book out of sight of an adults gaze and curtains as an opportunity to hide. All of these objects would be dangerous to use as a child would imagine, but they would if you let them. The Wild Nursery will allow the children to explore to their hearts’ content, but safely with specially designed spaces in and outdoors so that the children can test the limits through imaginative play without restrictions, instead of sitting in an ordinary classroom, day dreaming about exploring around the room. This could be through the use of integrated climbing areas within the walls, or a sloped surface within the green skins where they can climb. Both scenarios include a safe surface to fall on to when the limits are pushed too far. This allows the child to realise that it could have been dangerous, but without getting hurt; helping them to become more independent and confident on their own accord.

LSA2021 54

M1.50, This visual explores the green skins in more detail, showing the individual species of plants and animals, and how the children will be able to interact an observe them. The sunlight is also represented which will pass through the green skins, and the shadows they create are projected onto the floor

M1.51, This visual shows the atmosphere of being within two green skins. This space can be used to explore and new discoveries can be made every day. This shows how people and animals can live together in harmony.

M1.52. Models constructed from 3D printed and laser cut parts communicate the parametric form through the curvature of the materials. The primary wooden beams are pre-formed to the specific curves they require to create a strong base. The secondary structure is connected to the front and back of the primary beams which is a lightweight trellis that provides a suitable base for the climbing plants to naturally grow from the ground up.

M1.53. The strategic placement of the deciduous and evergreen planting, the buildings efficiency can be increased by using the deciduous planting on the south side of the building and the evergreen planting on the north side. This will mean that in the summer shading will be provided to the building where the sun would usually hit, therefore lessening the need to cool the building through other means such as air conditioning, which would increase the buildings running costs. It also provides shade to the outdoor play areas, making the space more versatile so the children can play outside more.

LSA2021 55

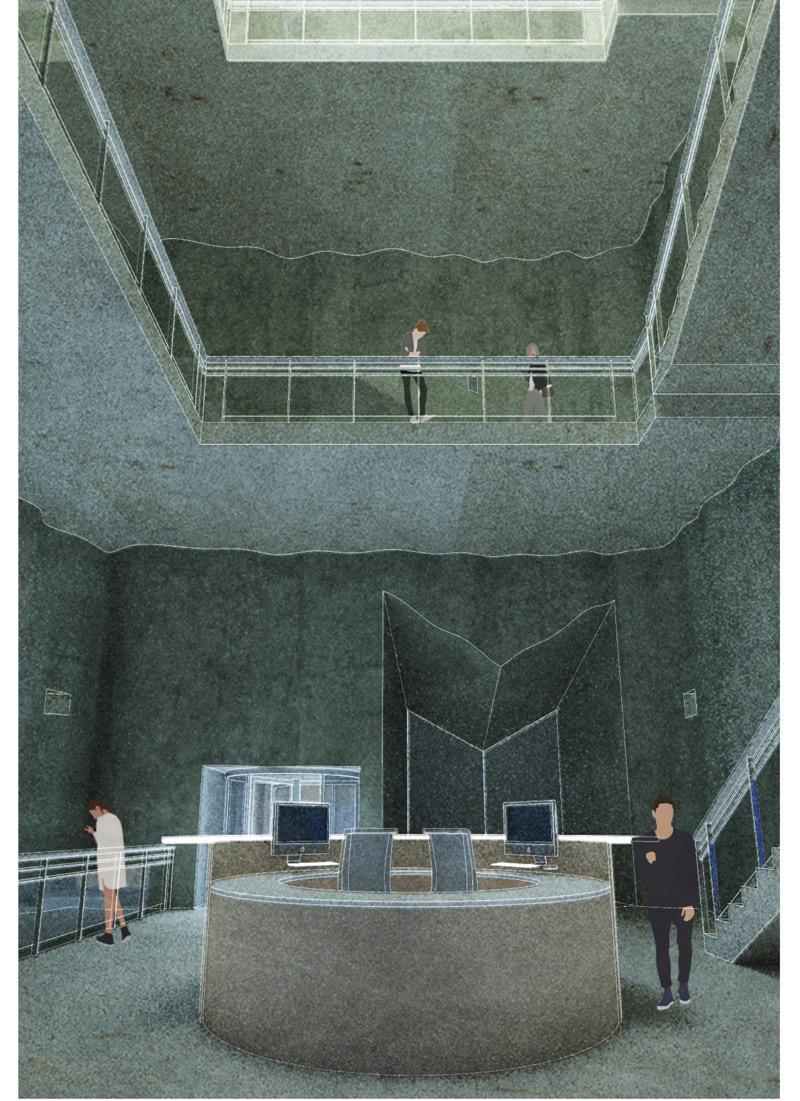

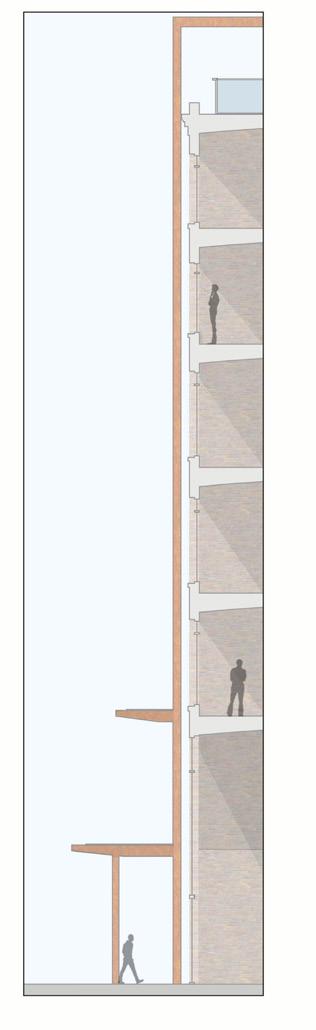

STUDIO two

States of Urbanicity

02

Year 5

Year 4

This Unit is about the study and speculation of Architecture in the many states of the industrial urban condition.

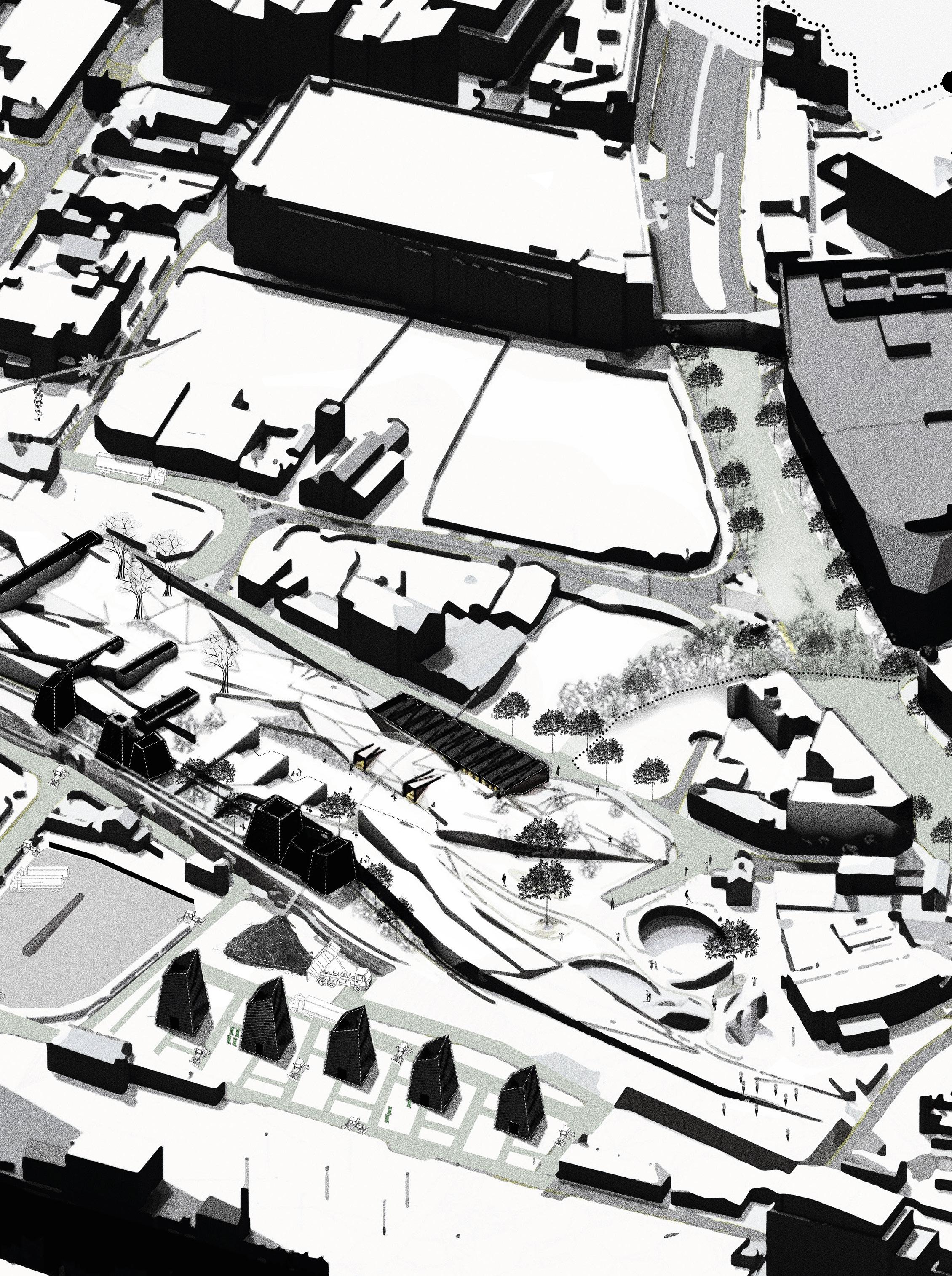

Over the past half a century, UK industrial landscape has become marginalised as the expanding global economy has brought manufacturing to various external international markets. This studio begins with investigations into the rise and fall of industry in the city and the inherent effects on the building stock and general urban condition. Existing patterns of urbanization in UK post-industrial cities are examined and new ways of inhabiting are proposed systematically designing with aging infrastructure.

The Unit works to develop a body of research that will identify opportunities for equitable development with respect to urban density, energy independence as well as social equity and policy. The city of Birmingham is the focus point for the testbed of ideas for MArch 1 students, while other sites can be considered for MArch 2 students wishing to approach the topic through a more global lens. Like many large urban centers today, Birmingham is undergoing the challenge of mitigating

unemployment amongst other economic challenges raised by the decline of manufacturing. Birmingham in the past was often known as “the workshop of the world”, before industry began leaving the city in the 1970s. The city has therefore reinvented itself as a vibrant ethnically and economically diverse place to live, with the local economy now focusing on service, retail, and tourism. This is not to say however, that the process of making has left the city entirely. Birmingham still produces over £2,000,000,000 of goods per year. The spirit of innovation is still alive and well.

The studio capitalised on the organic movement to radically rethink and holistically address some of the more abandoned and underutilized former industrial areas of the city. Themes of ecology, metabolism, food and energy, as well as infrastructural and systems design will be explored through design research and formal experimentation. The subject of the studio will include a contextual analysis of global urban trends and an in-depth study of Birmingham and its current trends in development, planning, and politics.

As for the MArch 2 sequence, students are allowed to work in other global post-industrial cities tackling similar challenges, as long as the work addresses similar studio themes.

LSA2021 57

Dr Yuri Hadi Lena Vassilev

Anisha Sharma Mehul Ashok Jethwa Kisheoun Sathiamoorthi Nadir Zadran

Jonathan Edwards Deepak Jayantibhai Prajapati David Cunnington Abdifatah Ali

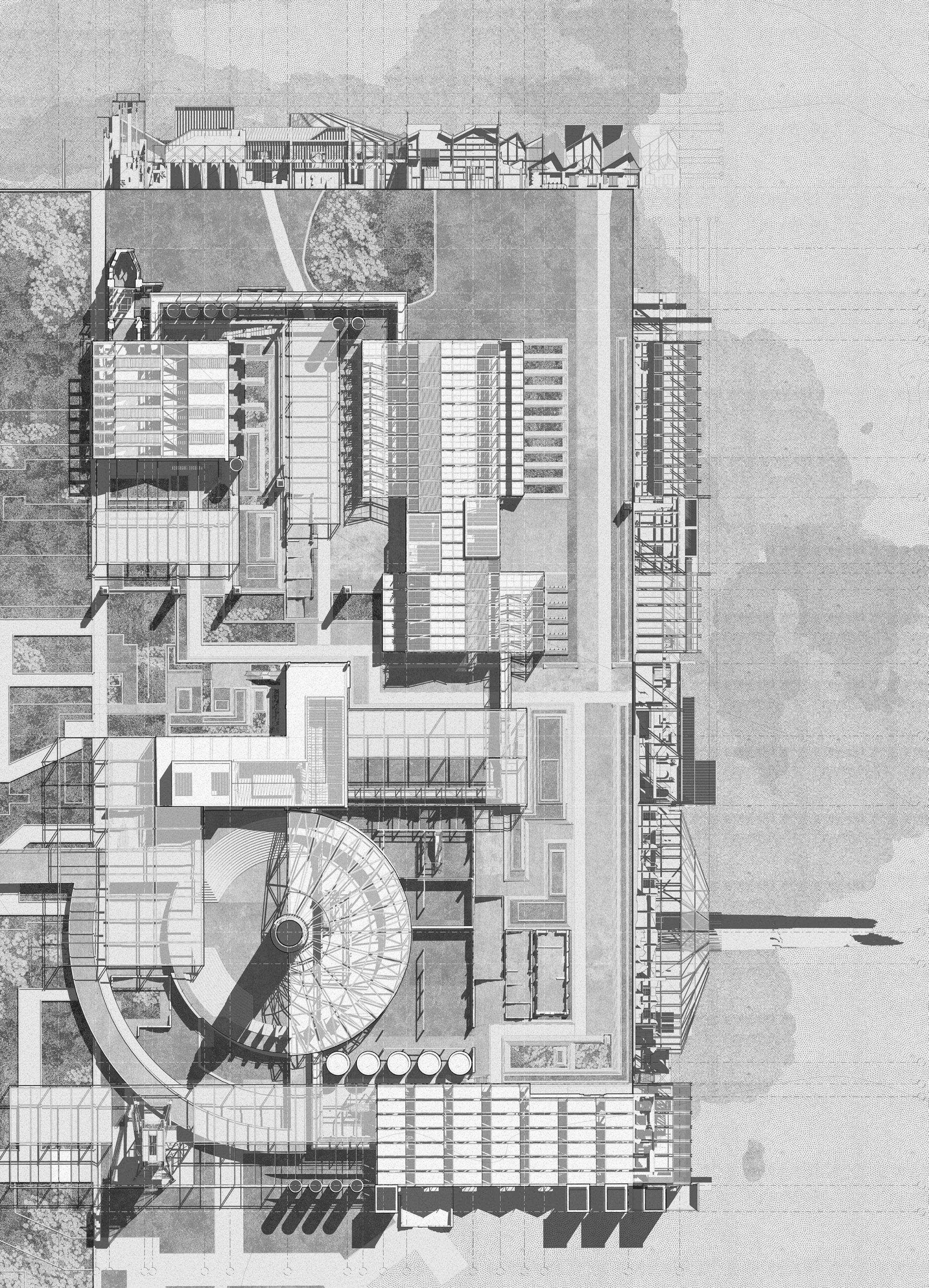

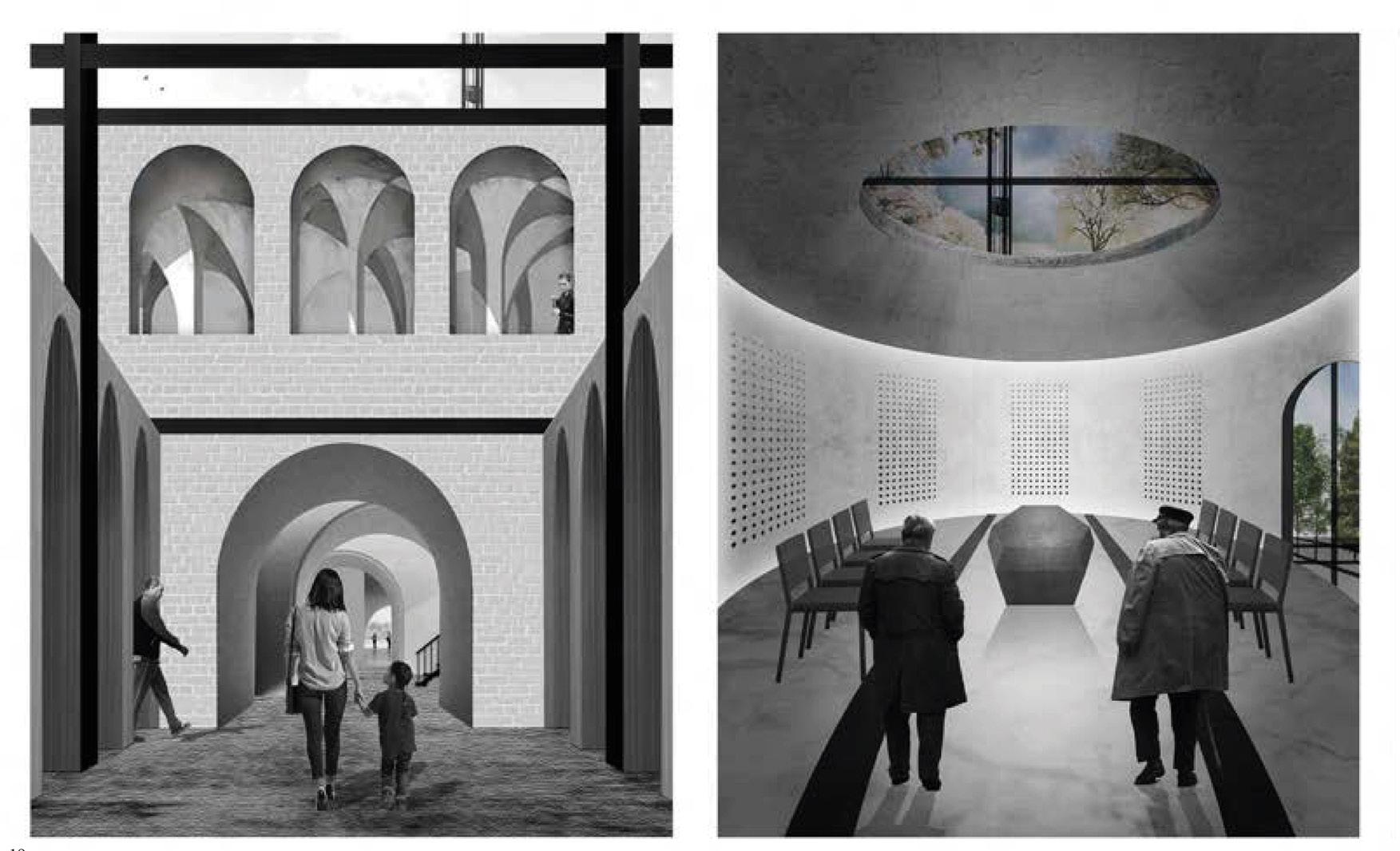

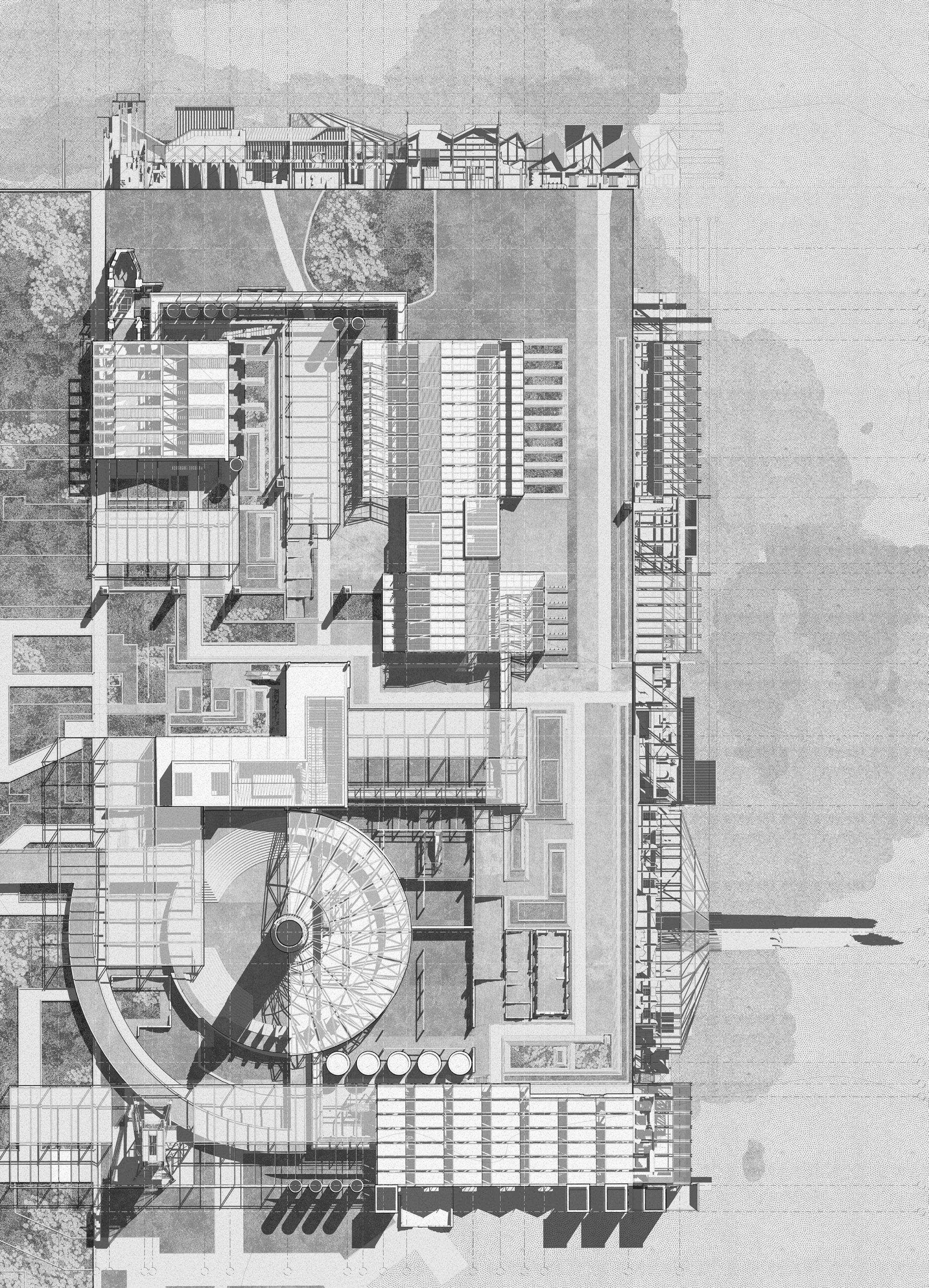

Opposite: M2.01, Ben Harrell (Y5) - The Vessels of Penrhyn, Wales

William Dudley Daniel Hambly

Benjamin Harrell

Pan Leung

Janusz Moore Oon Lam Wong

Gabriel Cristea

George Cristea Marcus Bree Pollyanna Beasley

BEN HARRELL (Y5)

“Vessels of Penrhyn”

Fairbourne is soon to be the first British settlement to be flooded due to climate change. In response, the local authorities have decided to remove the village from existence to prevent harm to human life and the surrounding environment, causing a displacement of its local population creating the UKs first climate refugees.

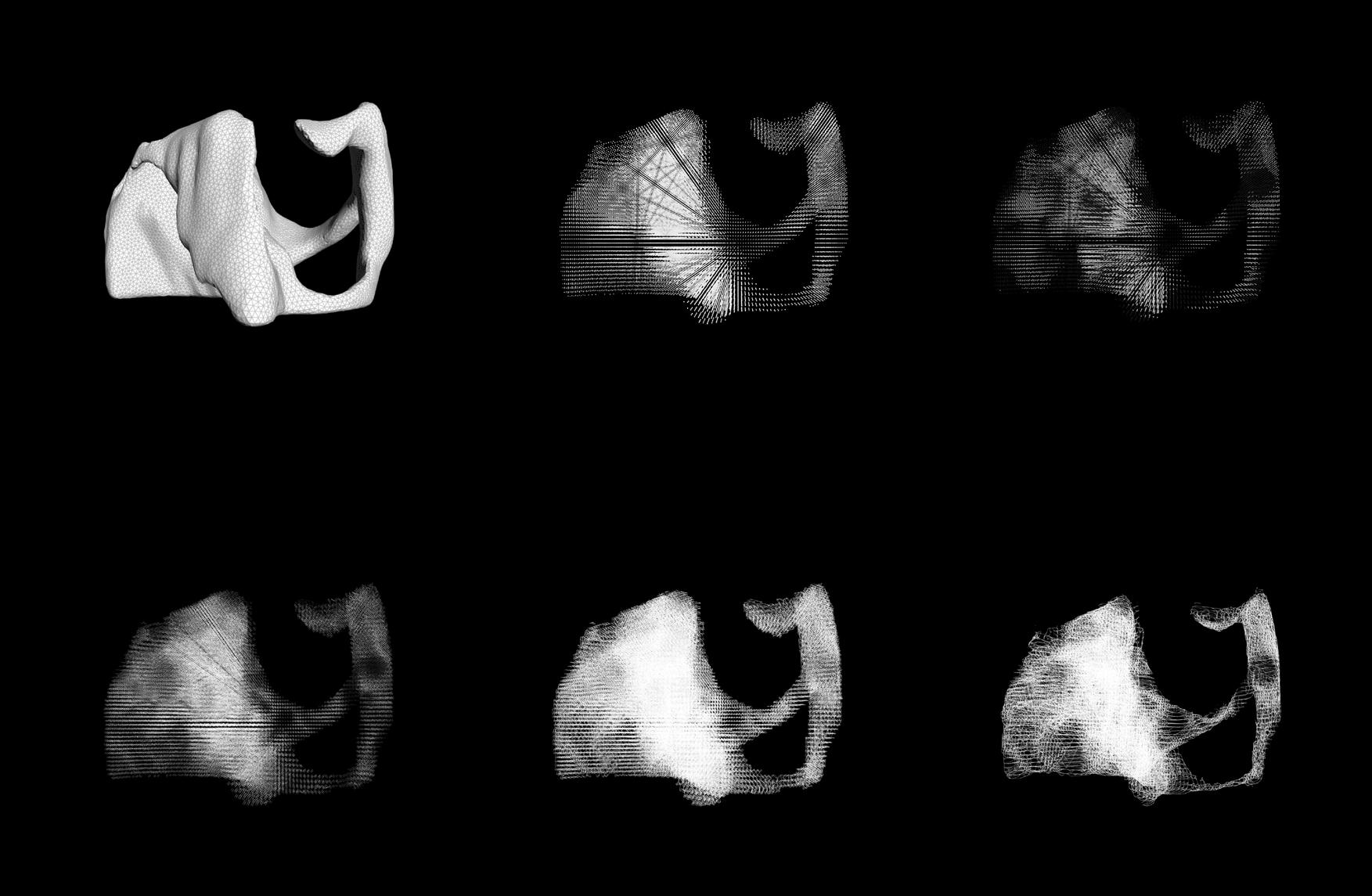

JANUSZ MOORE (Y5)

“Ruincarnation”

Ruincarnation seeks to respond to a new set of challenges, resulting from a global metamorphosis. The project deals with the subject of entropy and decay, looking to the UKs industrial past as one solution to its future. The outcome is a speculated future, in which design has been able to overcome these challenges with the integration of modern technological systems whilst respecting the systems of the past.

DANIEL HAMBLY (Y5)

“Transient Plasticity”

Transient Plasticity and explores the life cycle of plastic in our current society. The building sits on the bank of the river Mersey in Liverpool, recently crowned the single most polluted river in the world in terms of microplastics, even more so than the great pacific garbage patch.

WILL DUDLEY (Y5)

“Hotspur Home for the Lost”

A project that deals with the subject of mental healh in the UK. It inteprets rehabilitation stages to themes of character that are translated into form and space. These spaces are to offer people chances to stop and contemplate, or discuss their own mental health.

MARCUS BREE (Y5)

“Borve Center for Rehablitation for PTSD”

This project researching in creating a healing environment to rehabilitate PTSD patients from The British Army and Special Forces. The project looks at the use of gardens and healing spaces from group to individual therapies set on an abandon mill in East London.

GEORGE CRISTEA (Y5)

“Arts Haven Pavilion”

Arts Haven is a bold artistic approach to the monotonous Digbeth landscape that blends innovation with sustainable design to create a highly recyclable and reusable building complex aimed at delivering good quality public space.

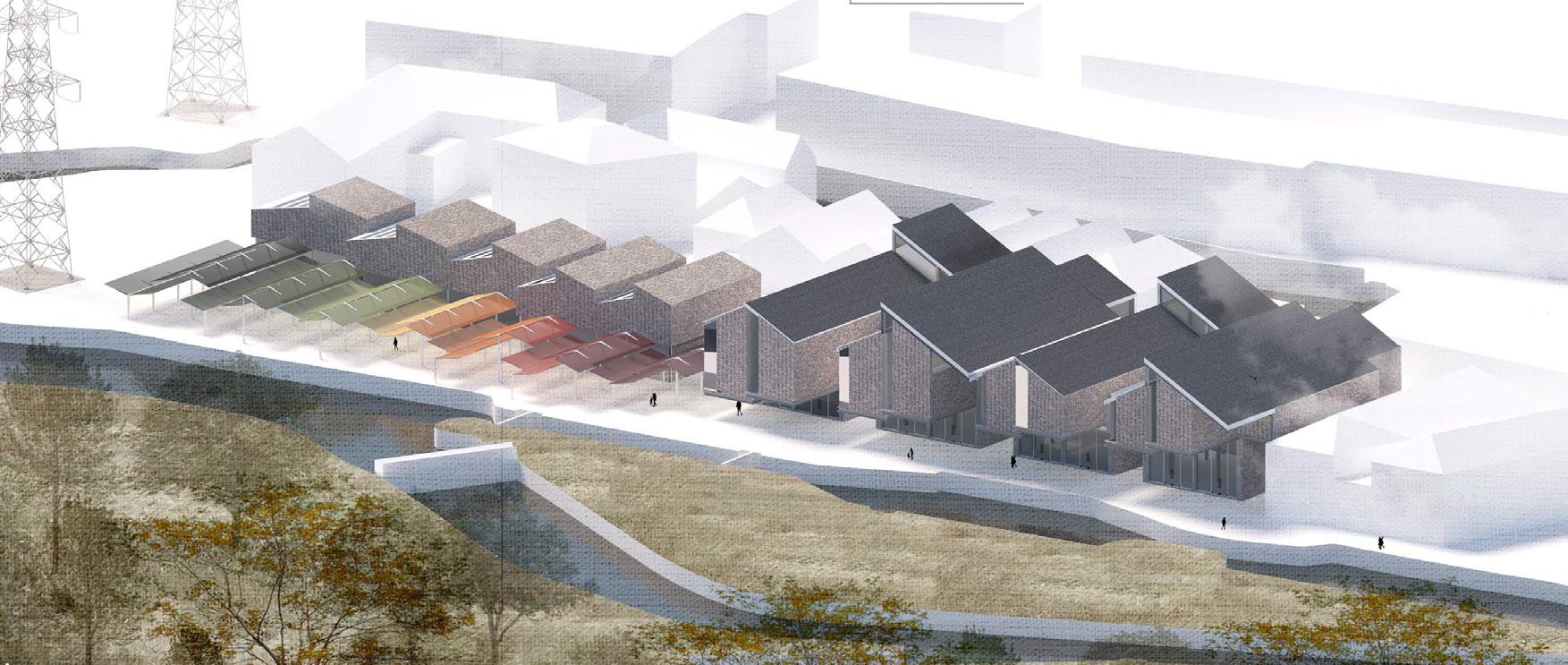

GABRIEL CRISTEA (Y5)

“Garden Wharf Development”

Starting from an interest in public green spaces and city farming, the project slowly developed into a polished design which proposes a series of vertical farming towers within the city of Birmingham. The proposal, the Garden Wharf, is one which utilises the shape of the towers in their advantage to maximise the light inside, while still offering plenty of space for food growing.

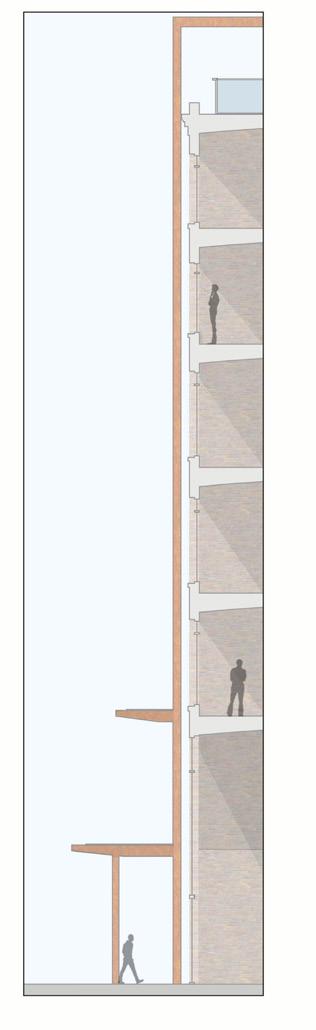

PAN LEUNG (Y5)

“Arts Tower- Housing for Arts and Craft Hong Kong” High rents are an unsolved problem in Hong Kong. Hong Kong’s housing policy is mainly focused on low-income people. A project focusing on a niche group in HK - artists. How can a vertical village of artists can be designed in Wan Chai, Hong Kong?

POLLYANNA BEASLEY (Y5)

“Communi-Tea”

Digbeth can be considered to be more ethnically diverse than the UK average. The UK population is approximately 86% white, with residents of this area being 52%. The next largest ethnic groups are Chinese and Indian. Culturally, these groups have tea engrained in their way of life. This proposal has been designed to allow different cultures and people in the community to embrace tea culture by the way tea is made, consumed and how people interact with tea.

ONN LAM WONG (Y5)

“Vertical Public Spaces”

A project that looks at the possibility of designing vertical public spaces in Wan Chai, Hong Kong. Open green spaces are a rarity and much needed in the city. How can we design a vertical garden within a small plot of land while maximising its use and space?

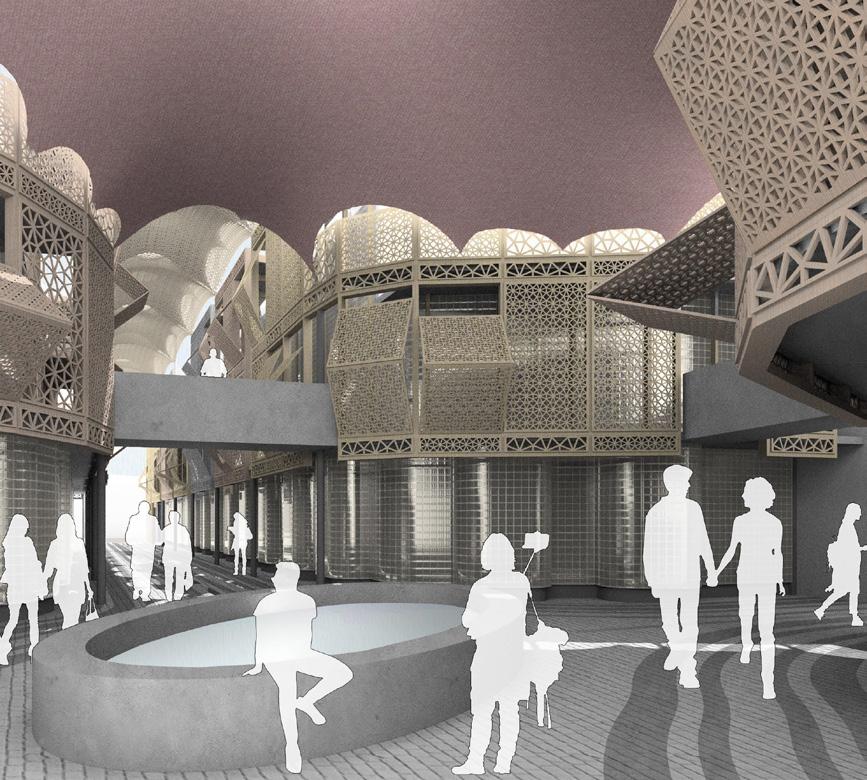

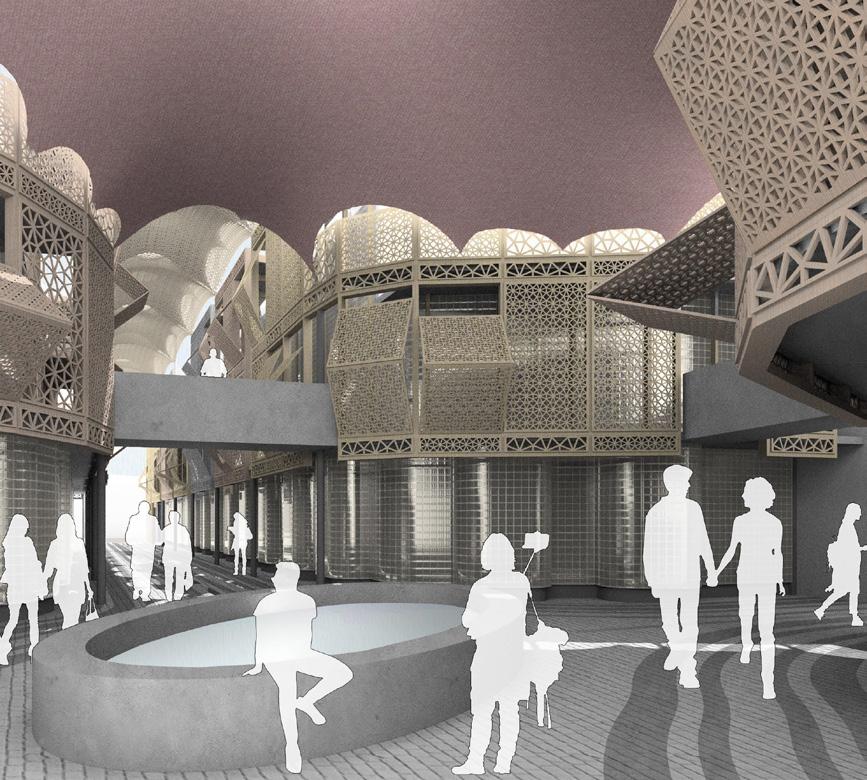

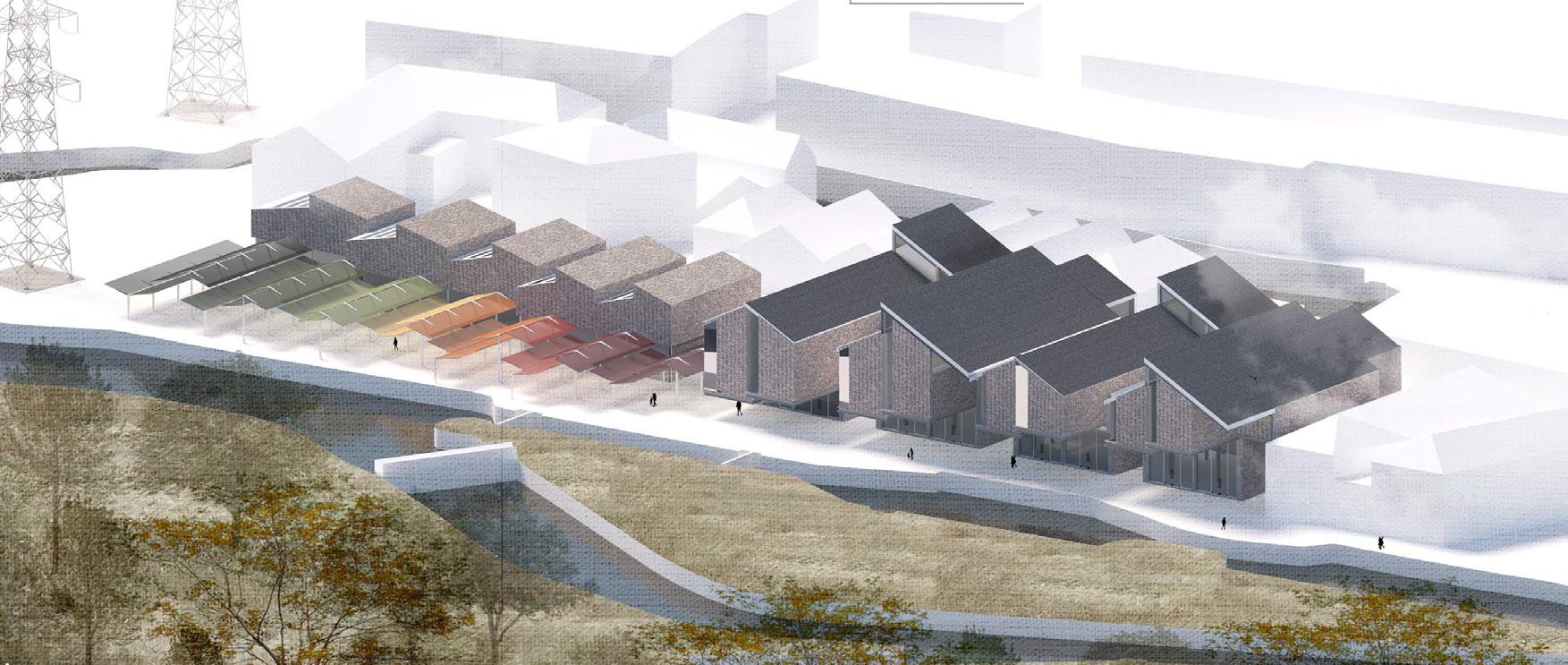

JONATHAN EDWARDS (Y4)

“Digbeth Creative Bazaar”

The Digbeth Creative Bazaar is a shopping and making destination in the heart of the Birmingham district of Digbeth. The project deaks with Urban Regeneration by retro-fitting lost and abandoned buildings turning them into an arts and craft centre and shopping district.

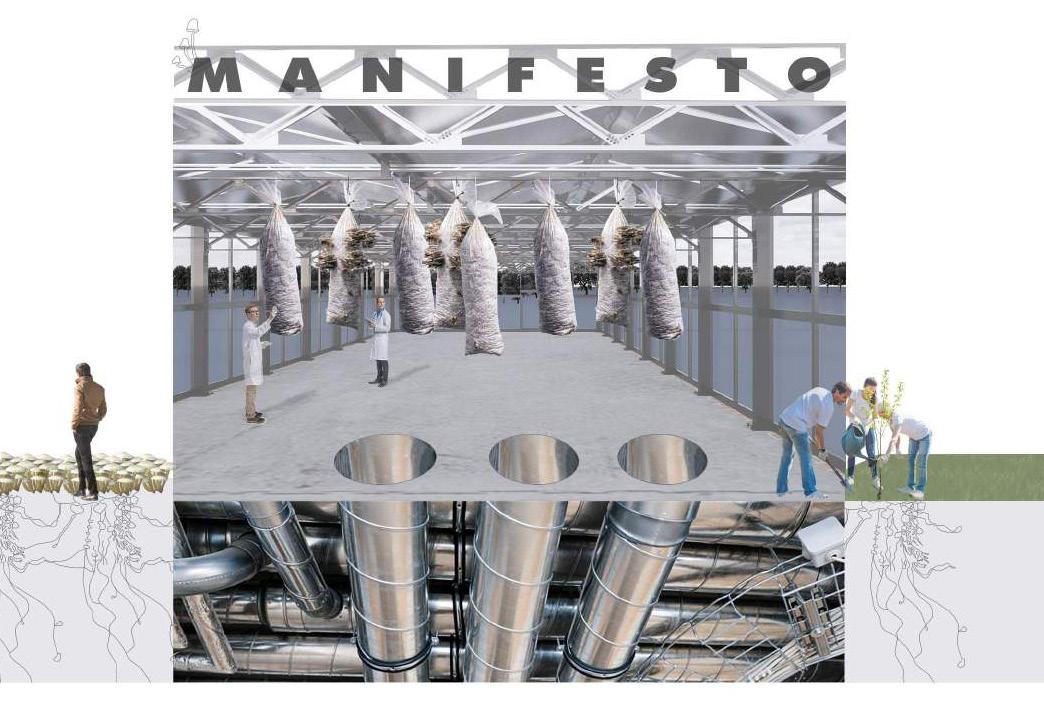

MEHUL ASHOK JETHWA(Y4)

“We Grow!”

We Grow! is an Urban regeneration project that looks at turning abandoned industrial areas in Digbeth, Birmingham into productive landscape for growing food. This concept follows both Birmingham’s new narrative to be a service city but also following trends in the city in the food industry.

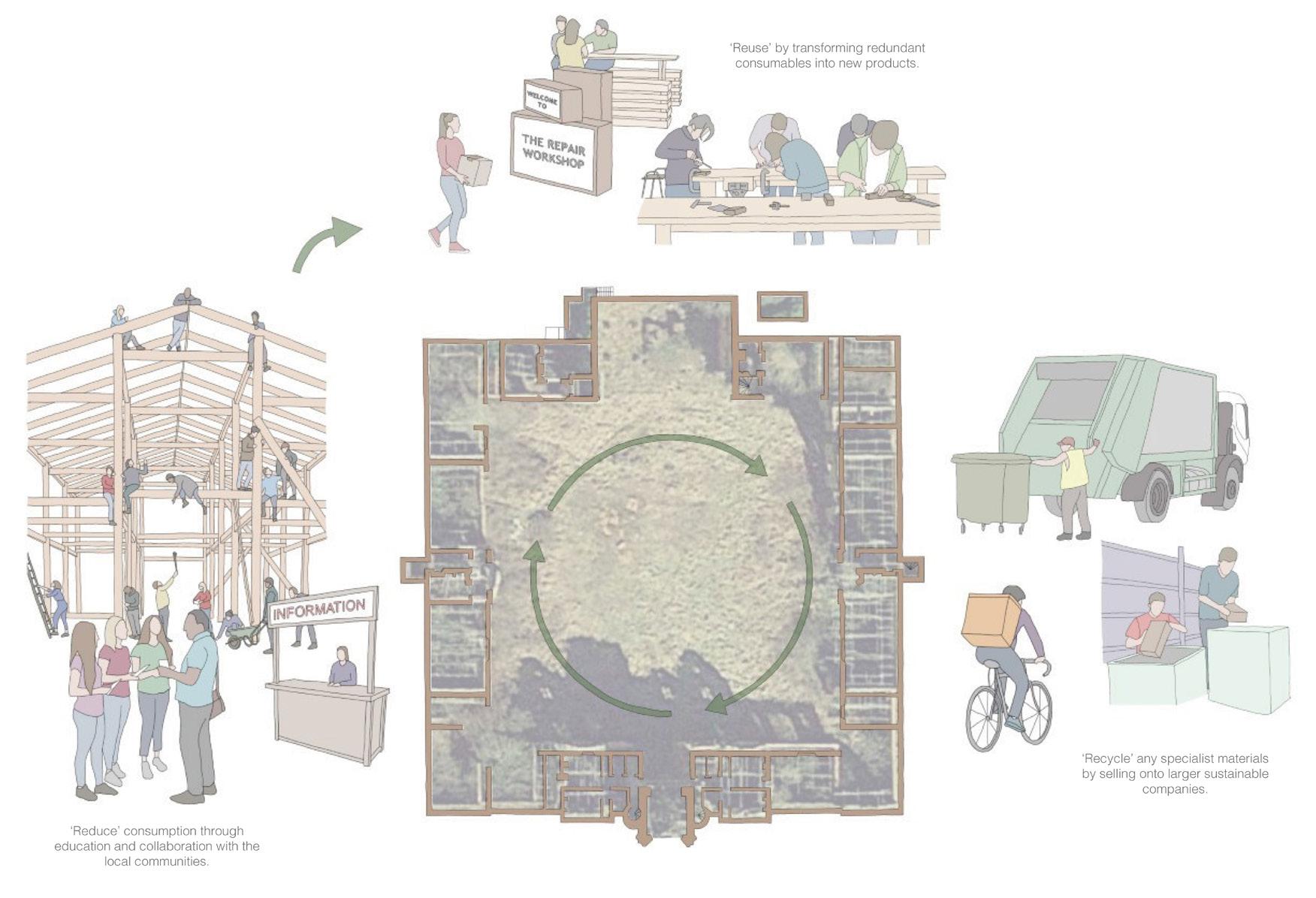

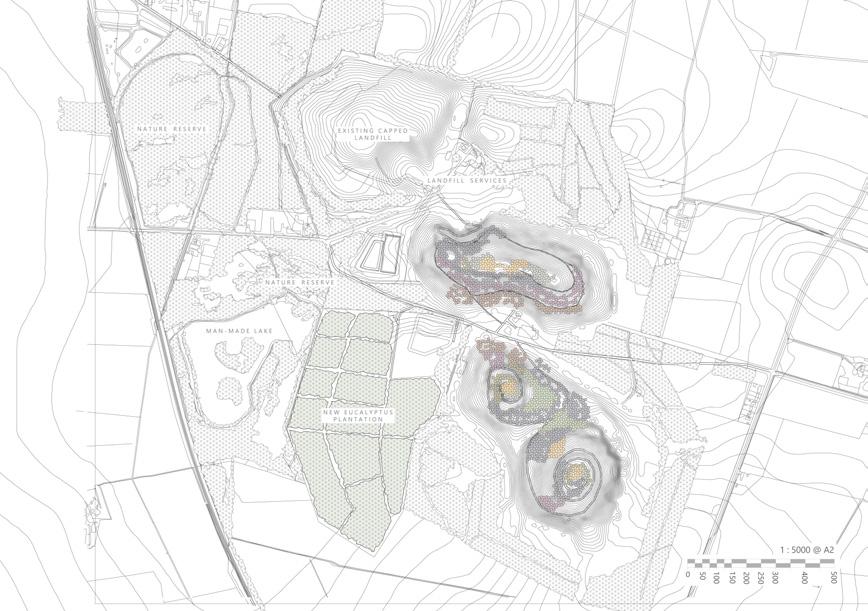

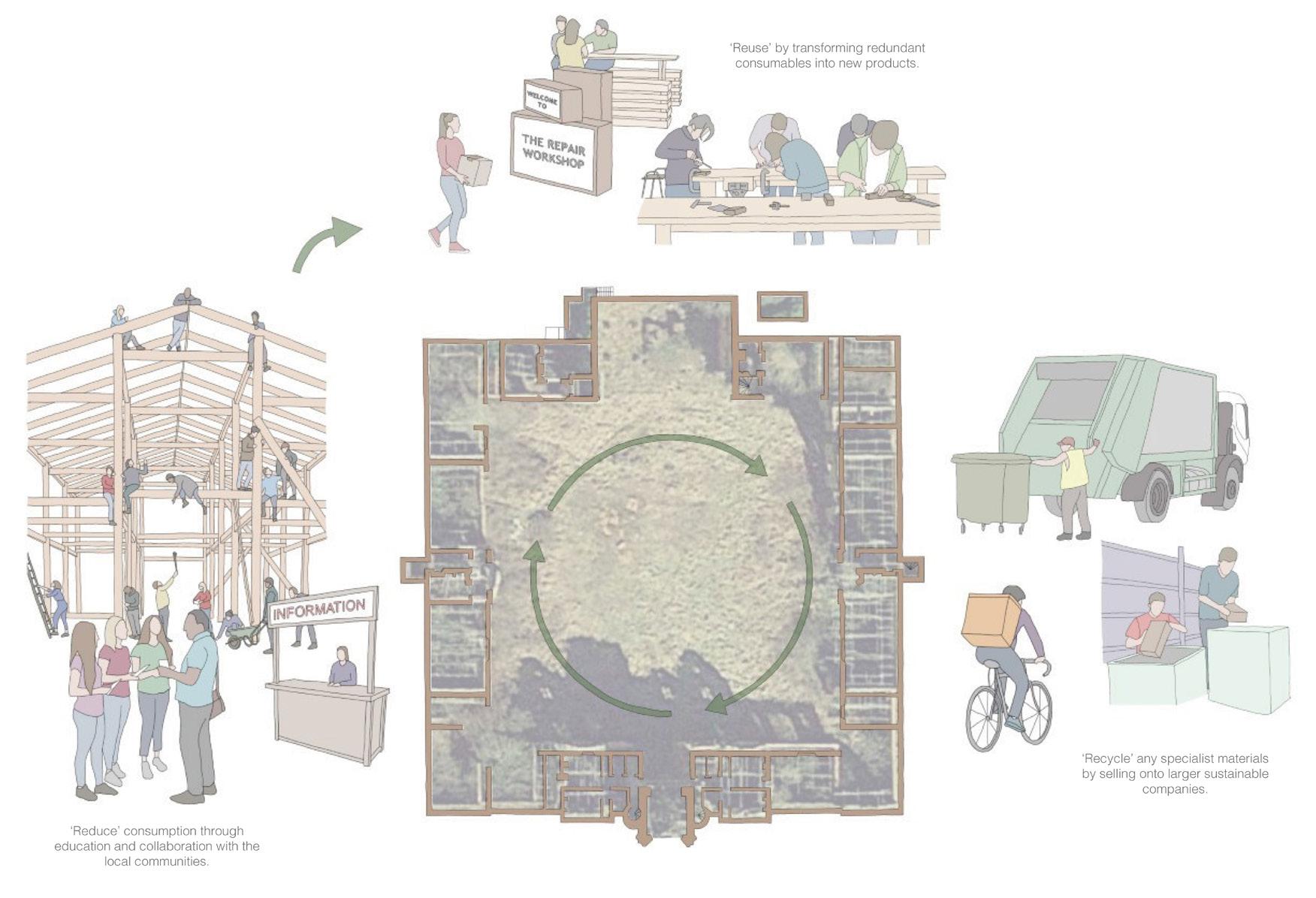

NADIR ZADRAN (Y4)

“Circular Economy”

The circular economy project is about encouraging the public to interact and participate with not only the process of upcycling and recycling but to also enjoy the journey behind it. Upcycling, also known as creative reuse, is the process of transforming by products or wate materials into new materials or products of better quality and environmental value.

ANISHA SHARMA (Y4)

“Urban Rehabiliation Community Garden”

The scheme will recognise the rehabilitation garden center as a tool for community social interaction, recreational, and a source of income as a means of aiding homeless people’s return into society.

DEEPAK PRAJPATI (Y4)

“Advanced Prototype and Production Research Center”

Advanced Prototype and Production Research Centre is aimed to provide a platform for inventors that have limited resources to realise their ideas. The centre is a collaborative platform where people with unique ideas can work together.

KISHEON SATHIAMOORTHI (Y4)

“Digbeth Performing Arts Centre”

A project taking inspiration from broken fragments of urban form turning it into a collective or inhabited scluptures on top of the abandoned Birmingham train viaduct.

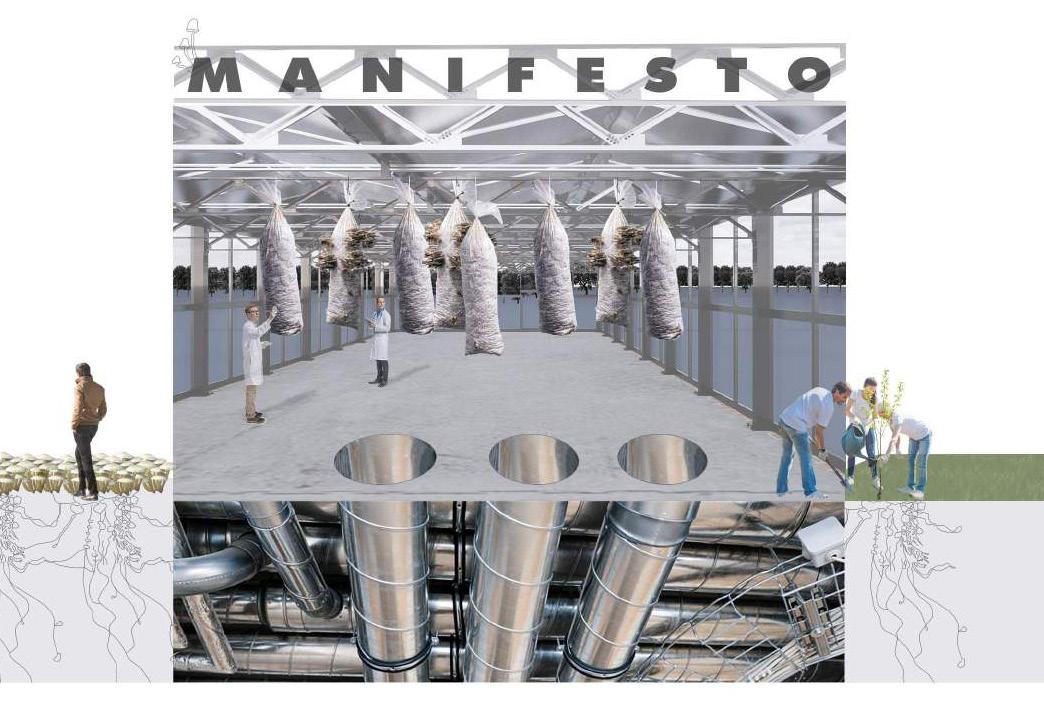

ABDI ALI FATAH(Y4)

“Hempus Centree”

The project aims to create a sustainable industry witin the Digbeth. The aims for the project will tackle the key issues states through the research. The agricultural lab will provide a faci1ity for research and development for sustainably grown crops, allowing a new generation of researchers and potential education facilities, to show the benefits of hemp.

DAVID CUNNINGTON (Y4)

“Digbeth

Regeneration”

The intention is to do an intervention to The Brolly Works and The Custard Factory - both are located at the junction of Coventry street. The aim is to give more provision for green space to create a new sense of place and identity to its population. Both the Brolly Works and Custard Factory have a strong heritage to Digbeth and its identity.

LSA2021

58

M2.02 Ben Harrell (Y5) “Vessels of Penrhyn- Village Forum Amphitheater”

Ben Harrell (Y5)

M2.02 Ben Harrell (Y5) “Vessels of Penrhyn- Village Forum Amphitheater”

Ben Harrell (Y5)

This project’s origins stemmed from stumbling across a BBC news article, published in October of 2019, amidst the global climate change protests. The article entitled “Sea-threatened Fairbourne Villagers call for answers” leapt out from the surrounding fog of headlines (Sea-threatened Fairbourne villagers call for answers, 2019). This concern about our changing environment is reflective of the current zeitgeist. This movement showed that my generation (bridging between millennial and generation Z) most passion ately concerned about the environment’s health and dealing with most of the consequences. This article actualises the consequence of humanity recklessly polluting our planet.

Upon reading the article, I became conscious that the repercussions of polluting our atmosphere with greenhouses gasses for decades have manifested in our sea levels rising so much that they have now start ed to affect human habitation in the UK. Due to these rising sea levels, the settlement of Fairbourne, located along the welsh coast and dating back to the late 1800s, is now under severe threat (Sea-threatened Fairbourne villagers call for answers, 2019). This is to the extent that an intervention must be made, as the village will be unfit to exist in years to come. The threat to Fairbourne now means a village in the United Kingdom, a ‘first-world’ country and ‘global leader’, has an impending expiration date.

The hard truth is that this will create the first ‘climate refugees’ within the United Kingdom. Fairbourne will not be unique in being claimed by the sea. As we gain greater awareness of this global issue, we must realise that this situation will worsen over the coming years and simply will not improve. As an island nation with multiple coastal communities, Fairbourne is merely the first to face these issues.

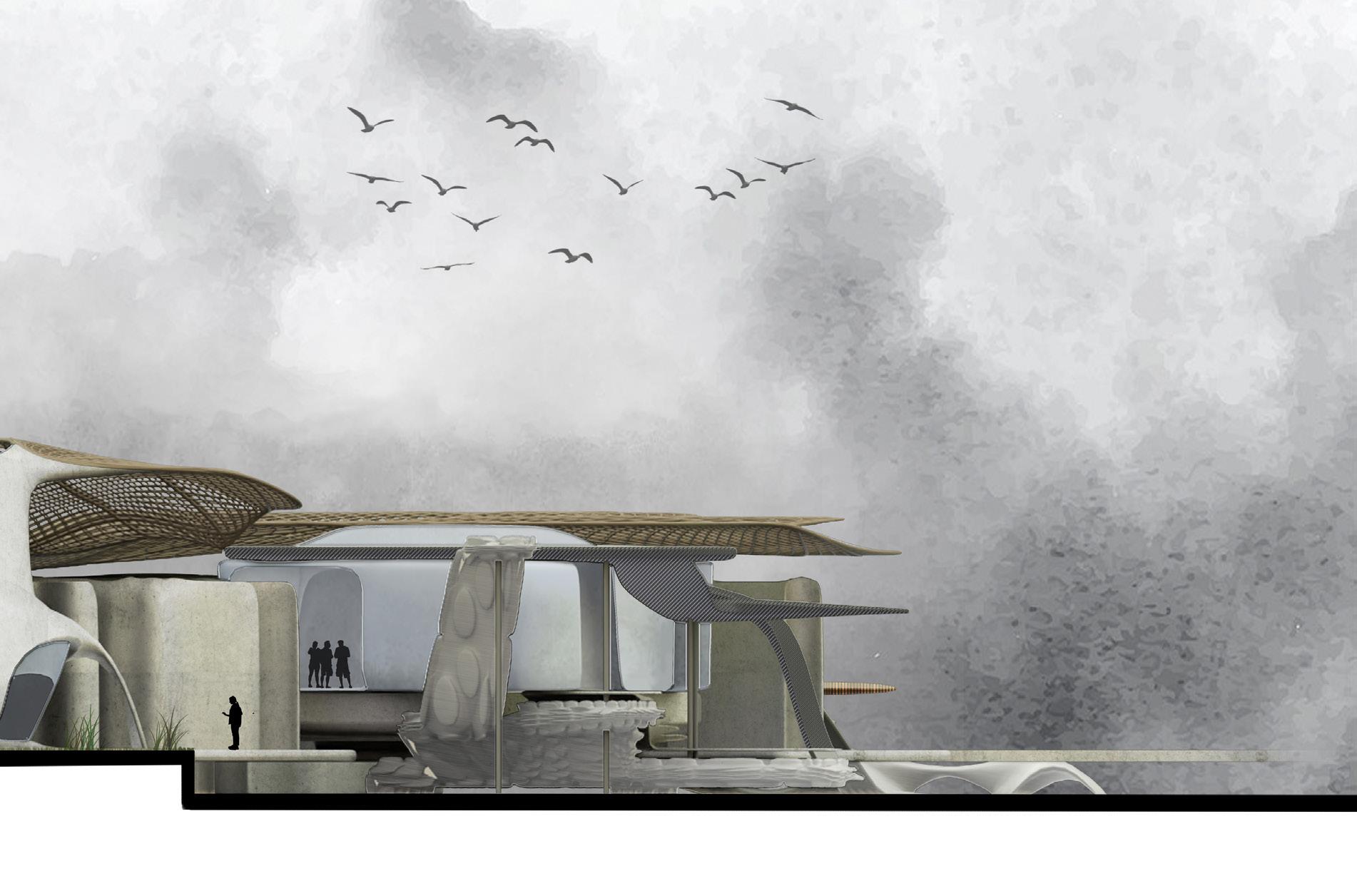

M2.03, Lower levee master plan for New Fairbourne with farming grounds. Vessels of Penrhyn is set in 80 years in which the villagers refused to move from their homes and adapted their life and village to survive among the flooding marsh, entering a symbiotic relationship with the sea, embracing the changing tidal landscape. This project explores further themes such as phenomenology, Sea Defence Infrastructure, Coastal/Sea Farming, and Urban Design.

LSA2021 60

“Vessels of Penrhyn How to Rebuild a Village for Climate Change”

LSA2021 61

M2.04, Monuments, Vessels and Artefacts. WWII defences built in 1940 incorperated as part of the new sea wall.

LSA2021 62

M2.04, Illustration showing the connection between the Salt Marsh and the Sea how more industrial nursery area relate to the context of both the marsh and the upper walkway. These contain a shallow water line method, a fast floating method, and the suspension raft. These make delicate, shallow line seaweeds, medium durability and size seaweeds on the raft, and hardier deep seaweed readily available for the public and visitors to see.

LSA2021 63

M2.05, Inspired by the design of the homes that regularly flooded/experienced stor ms in Friog Corner, Germany, as shown in the site analysis portfolio. The idea behind the design is that all windows are protected with boards and shutters. Therefore in the case of extreme weather in the future, to help keep heat in or for privacy, the houses can effectively seal themselves off from the outside world and protect the glass. These houses are designed with the traditional vernacular of the Welsh longhouse in mind, dating back to the early middle ages with the Anglo Saxons.

M2.06, Aerial Isometric view of the new village. Further development of the master plan includes the addition of seaweed farming extending into the Irish Sea. These include shallow water rope growing in the shallowest, calmest region.

LSA2021 66

M2.07, Tidal Conditions: Normal. The barrier acts as the lower promenade for the village.

M2.08, Tidal conditions level 3: Mid tide.

LSA2021 67

M2.09, Tidal conditions level 4: High tide.

M2.10, Tidal conditions level 5: Spring high tide/storms.

LSA2021 68

M2.11, The Market Hall and Sheltered Garden: One of the most important buildings within the new village scheme is the market hall, in which people trade, serve food and socialise, inspired by the previous indoor-outdoor shops along the main road of Fairbourne. The market is to function by a series of pop-up stalls placed underneath the sheltered area, simulating the village’s weekly market once held. When the market is not open, space becomes a sheltered extension of the informal public square, in which people can socialise.

M2.12, Underneath the Walkway: The walkway’s design is based on the principles of the Barmouth bridge, the footings of which help prevent damage to the wood from both the sea and woodworm. In addition, the infrastructure needed from the Village, including freshwater, sewage, and electricity, is serviced from the void created between the upper and lower planks of the structure.

LSA2021 69

LSA2021 70

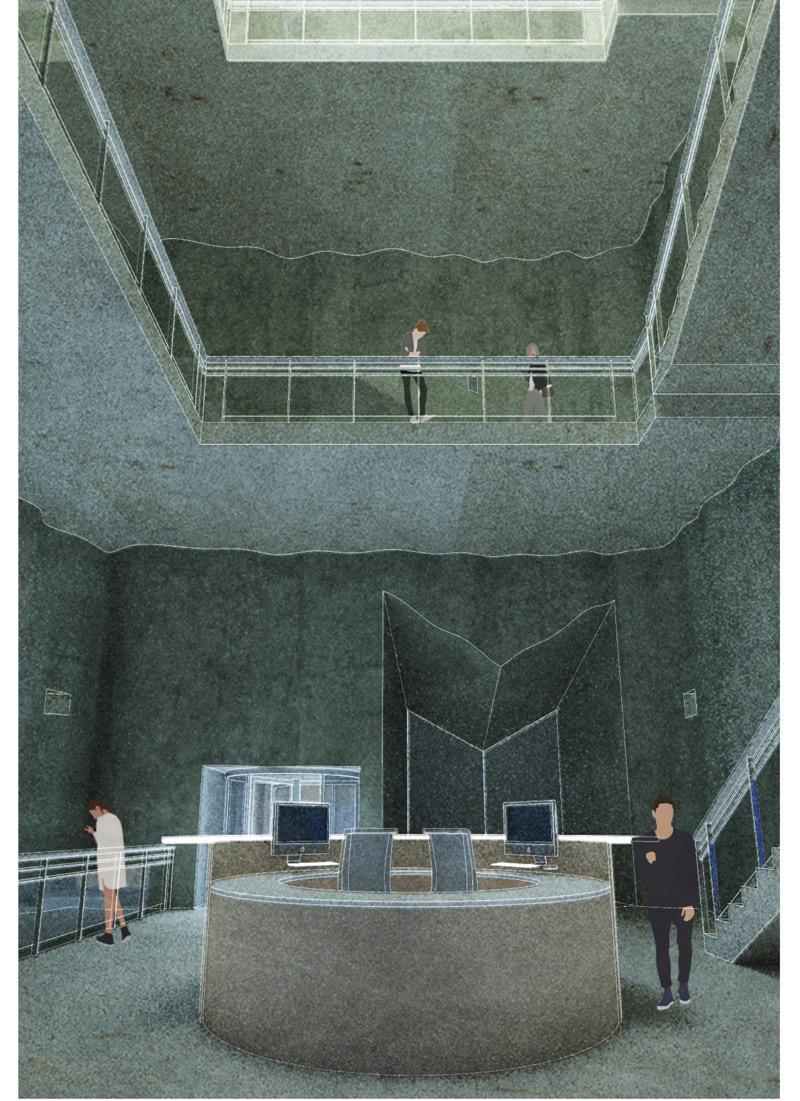

M2.13, The Amphitheatre: At the centre/heart of the village sits a forum manifesting in the typology of an amphitheatre.

M2.14, Community Centre/ Village Hall: Within this building, visitors can become educated as to the processes which happen on the site. It can function as a venue for talks (ground floor), a library on the First floor, and a village hall (free, flexible space on the top floor). Its more formalised programmes stem from the fact that any business growing and selling materials also need space where residents can undertake administration and managers can address staff. This space can also be used as a research and education centre to educate more people on the methods and benefits of seaweed farming.

LSA2021 71

LSA2021 72

M2.15, Community Centre/ Village Hall: Night Isometric in context to walkway and salt marshes.

LSA2021 73

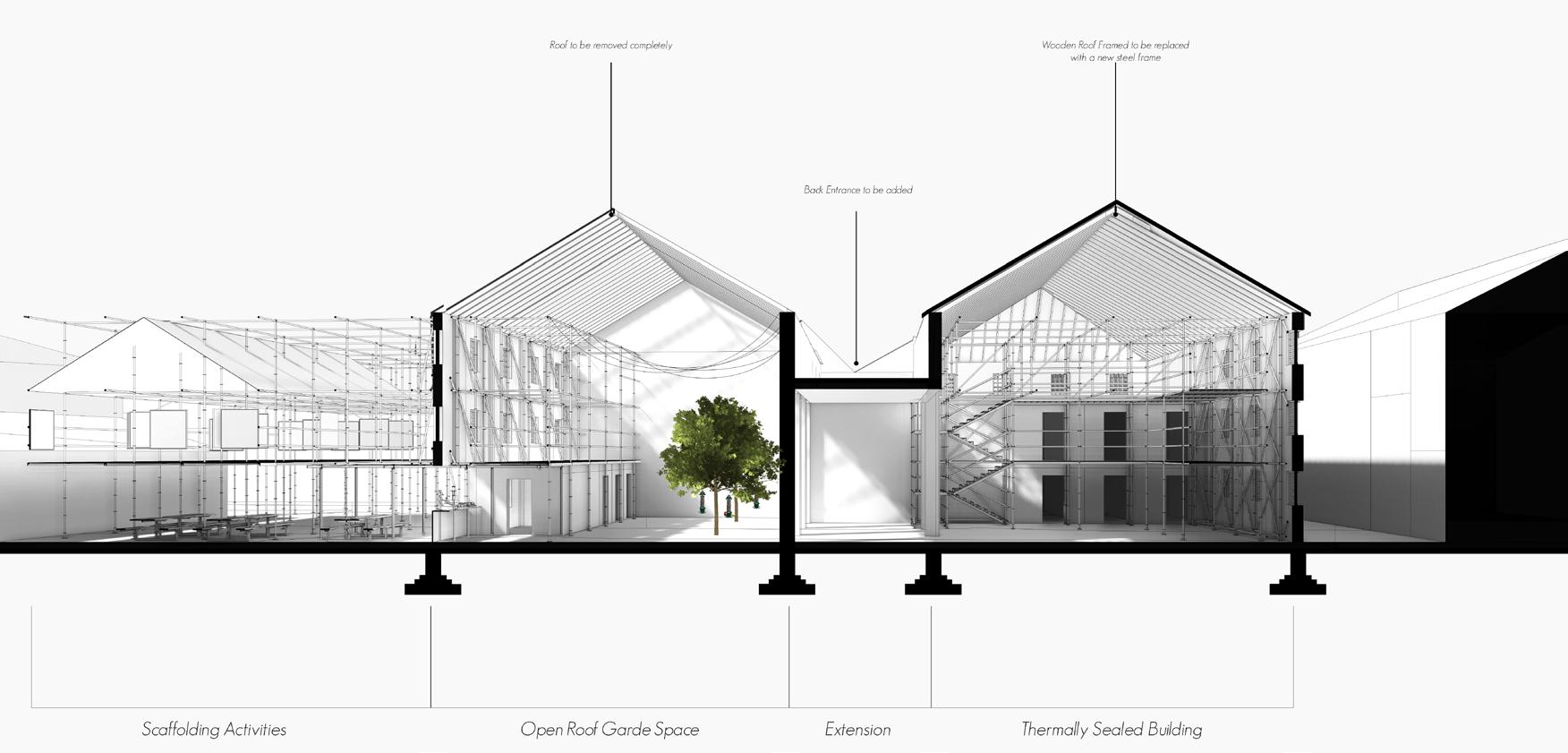

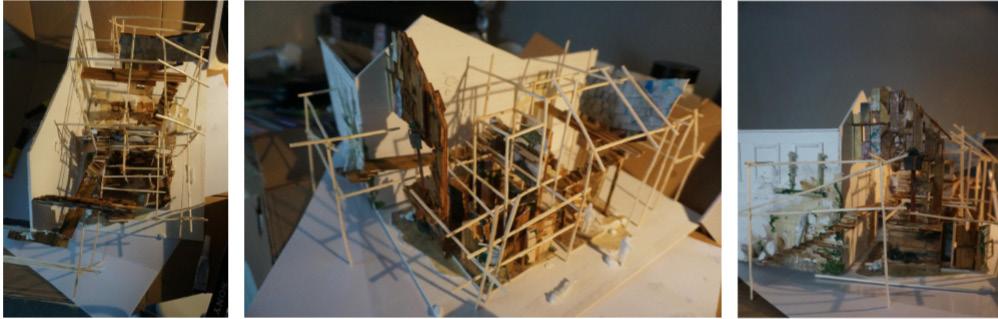

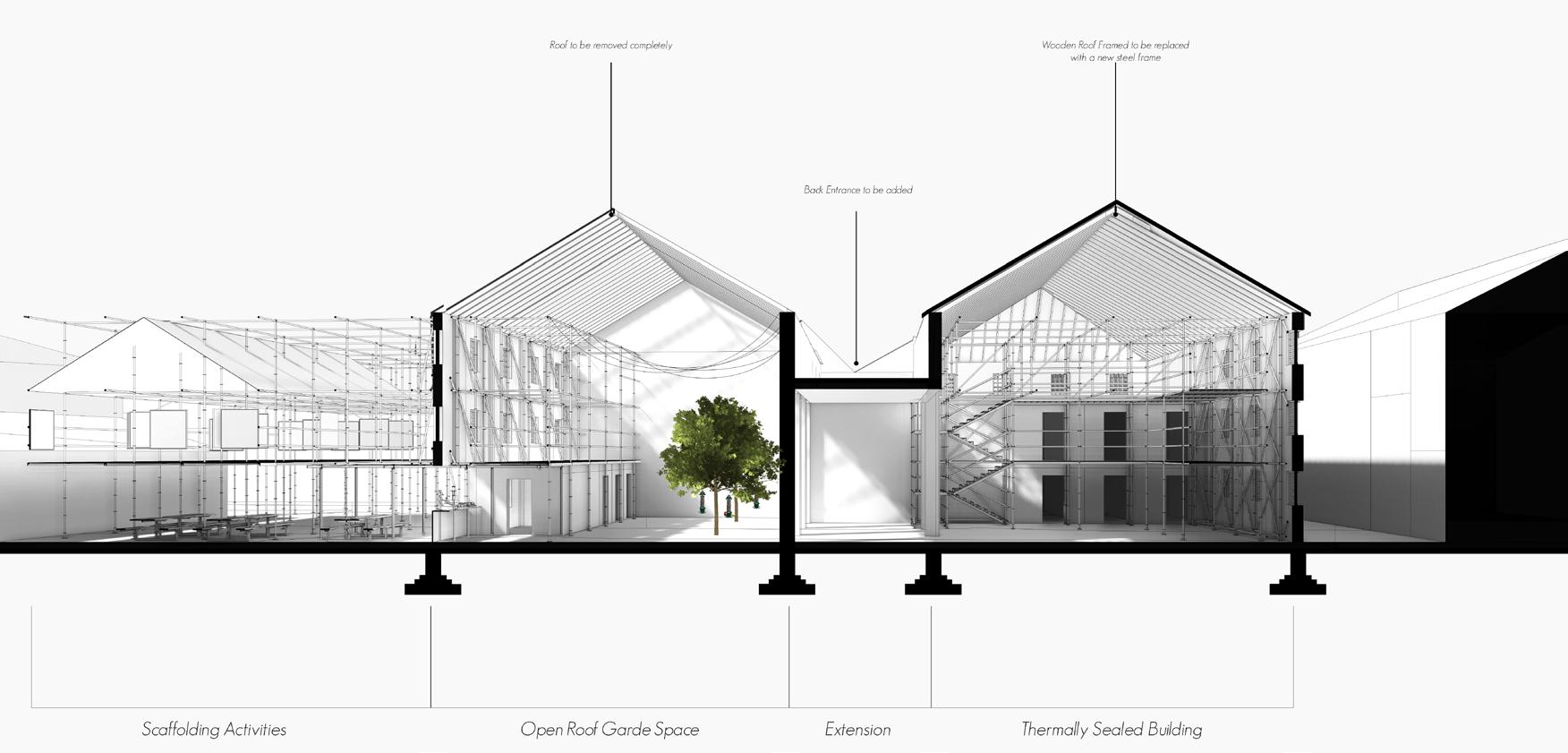

Ruincarnation responds to contemporary issues prompted by the political shift post-pandemic. As the UK adapts to these changes and breaks ties with the urban powerhouse, what might the nation look like during its shift back into rural society? This project looks to the UK’s rust belt as a new avenue for cohabitation and explores key challenges that come when dealing with historical sites subject to dereliction.

What are the processes necessary to transform these sites in order to revive the industrial roots and forgotten communities that ground them? How should we respond to material decay in order to highlight issues of finiteness and celebrate historical value whilst developing sustainable systems for development? Like many other rust belt towns and cities, Stoke-on-Trent is an area defined by its industrial past. The slow decline in industry over the past 30 years has resulted in a parallel deformation of identity. Within its forgotten collieries, steelworks, and potteries, the buildings themselves are in a state of constant entropy, suffering a slow death with little functional purpose but to remind us of their past achievements. Utilising Chatterley Whitfield Colliery as its anchor site, the project aims to create a new industrial identity for the UK’s rust belt, whilst celebrating its golden era of production.

M2.16

M2.16, Chatterly Whitfield Colliery, axonometric taxonomy of buildings. M2.17, Conceptual section illustrating the intervention of the site with new buildings.

M2.17

LSA2021 74 JAN MOORE (Y5) “Ruincarnation”

M2.18, The Circular Approach and the tevival of the UK’s Urban Rust Belt. Central to the ethos of Ruincarnation is the concept of circular economy. From the adaptive reuse of the industrial brownfield site to the use of timber produced on site, each phase of the continuously evolving programme revolves around sustainable approaches to design with longevity in mind.

M2.19

M2.19,

LSA2021 77 M2.20 M2.21

Roof Plan and Site Elevations. M2.20-21, Stage of intervention includes the construction of the construction warehouse, primarily from recycled and reclaimed materials, before the biopower plant is constructed and the site produces renewable energy to power the subsequent phases.

LSA2021 78

M2.21, Post-Intervention Phase: The second stage of intervention sees cohabitation be ginning with the formation of the residential terraces. By this stage the rhizosphere is remediated and the surrounding land is used for the production of food.

LSA2021 79

M2.22, Various building interventions and insertions.

LSA2021 80

LSA2021 81

M2.24, Isometric Section, Site Layout.

M2.24, Isometric Section, Site Layout.

M2.24, The design of the landscaping is chiefly driven by the functional programme. The expanse of vegetation in and around the site creates an encompassing garden typology. The primary function seeking to create a calming atmosphere, a zone of decompression as one moves between the structures. The design of the pool and walkways throughout the site have been modelled on the plan of the mine shafts and galleries deep below the surface. This provides a reference to the original colliery, for those who once worked the mines, using the reflective medium of water.

88

M2.24, Detail Section, Seed Bank & Herbarium.

“Nothing disappears completely ... In space, what came earlier continues to underpin what follows ... Pre-existing space underpins not only durable spatial arrangements, but also representational spaces and their attendant imagery and mythic narratives.”

Lefèbvre, H. 1991. pp.228.

LSA2021

LSA2021 89

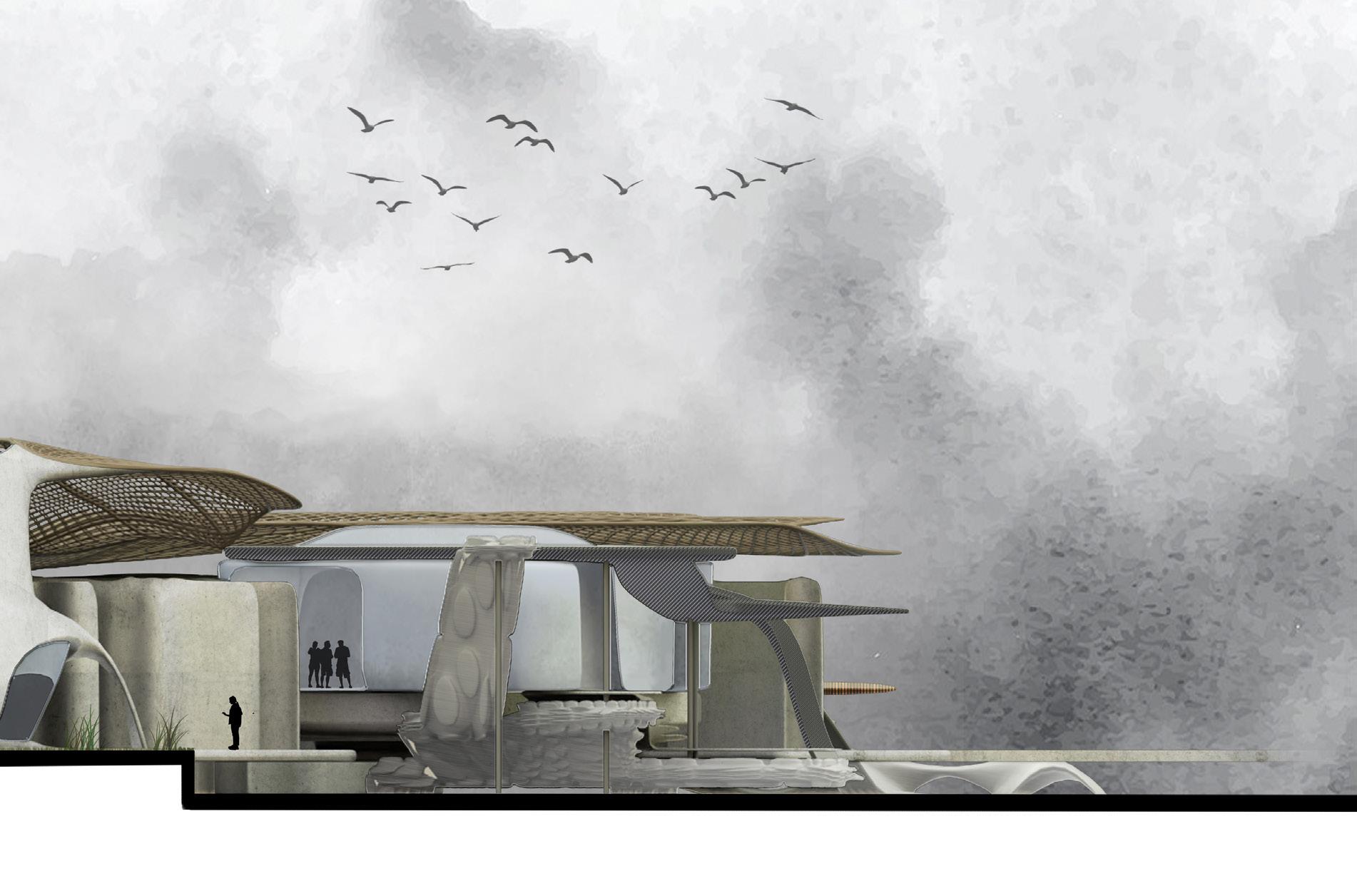

DANIEL HAMBLY (Y5)

“Transient Plasticity”

We are currently faced with an environmental catastrophe on an unprecedented scale. As a result of the global failure of the plastic recycling system, we are faced with 6.3 billion tonnes of plastic, of which 79% will accumulate in landfill or the natural environment. If this trend were to continue, by 2050, 12 billion tonnes of plastic will be leaching its way into our soil and waterways, further damaging ecosystems, and causing mass extinction.

Transient Plasticity explores the life cycle of plastic in our current society, providing an architectural response to the global issue of increased environmental plastic pollution through the synthesis of urban infrastructure and the dense fabric of the city.

The building sits on the bank of the river Mersey in Liverpool, recently crowned the single most polluted river in the world in terms of microplastics, even more so than the great pacific garbage patch.

The building acts as an organism, metabolising used plastics through the process of chemical depolymerisation, before repolymerising said plastics and developing them into new building materials, forming the canopy roof that covers the project.

The project is centred around the idea of a building’s life cycle matching that of an organism. The building metabolises plastic, cleaning the surrounding environment until there is no longer any plastic to be consumed, at which point it metabolises its outer shell, revealing the gardens below.

LSA2021 92

M2.25, Sextional perspective showing roof envelope in context to existing buildings on the Liverpool Docks

M2.26, Plan showing plant and public spaces inter-connecting with the waterfront. Due to Prince’s Dock’s location on the waterfront, an interesting opportunity was presented for receiving deliveries of raw plastic. Due to the dense water way network that surrounds Liverpool, many of the most significant recycling plants in the surrounding area are connected by waterways that feed into the Mersey. This means that plastic deliveries could be brought in by electric boat, directly from the existing recycling plants to the proposed bio-recycling infrastructure at Prince’s Dock.

LSA2021 93

M2.27, Green corridors were another aspect of the design that was particularly important. The overall philosophy of the design was that the building, through its existence, would begin to reintroduce wildlife back into prince’s dock, which had been lost since the industrial revolution. In order to achieve this, multiple different types of garden were introduced, each catering to different environmental conditions.

LSA2021 94

LSA2021 95 M2.28, East Elevation

M2.31, Over the last 50 years, the use of plastics has increased twentyfold. A study led by a team of scientists from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and the Sea Education Association, published in the journal Science Advances, found that since plastic production began in the 1950s, humans have created 8.3 billion tonnes of plastic, of which 6.3 billion tonnes have already become waste. Of this total amount of waste, only 9% was recycled, 12% was incinerated, and the remaining 79% ended up in the natural environment.

As the failings of the current plastics recycling system are systemic, they require an overhaul of the plastics recycling system. This overhaul would entail closing the linear system to form a closed loop, in which the input virgin feedstock would be replaced with renewably sourced feedstock, fed by recycled plastic from recycling plants or recovered from the natural environment.

M2.32, The Stage 1 visual depicts the project during construction. At this point, the Mersey. is still contaminated in extremely high levels of microplastic pollution. The internal machinery, metabolises the micro-plastics from the Mersey, and the plastics wastes from the surrounding recycling plants, the building begins to grow. The grwoth becomes a symbol of better times to come, as the environment is slowly cleansed from the contaminants that have blighted the Mersey.

M2.33, Next is Stage 2. At this point the Mersey begins to recover from its ecological collapse. This is due to the collection and filtiration of microplastics from the river itself, as well as dramatic improvements to the efficiency and prevelance of plastic recycling, spearheaded by the project. The building has reached it maximum size from the metabolisation of plastic as if it is an organism maturing into adulthood.

M2.34, Finally, at this point the Mersey has recovered from its ecological disaster. Wildlife and an ecosystem has flourished as the marshes begins to reform, providing new habitats for flora and fauna, that has been lost in the previous decades due to industrial activity. The building has reached its final form, metabolising its outer plastic shell exposing the inner block. These underlayer blocks are to become public buildings surrounded by the gardens that have merged with the marshes. This it the process in which the project gains its name: Transient Plasticity, relating to the transient or impermanent nature of the outer shell, lasting only when it is no longer needed. The shell metabolises into refined oil which can be transported to another location. This process repeats itself, truly acting as an organism that mutually benifits the form and improves the environment.

LSA2021 98

M2.35, Bio Concrete Terraced Gardens.

M2.35, Bio Concrete Terraced Gardens.

LSA2021 100

M2.36, Visually illustrating the connection of the building and the water taking the form of the pier lined by raw plastic delivered to the docks. The enzyme substrate delivery docks to the left. The enzyme substrate deliveries are then loaded into the building manually, whereas the plastic deliveries are fed directly into the shredders mounted on the pier.

LSA2021 101

LSA2021 102

M2.37, The internal promenade viewed from the first floor. A key design consideration involved highlighting the circulation through the building as a journey that reveals each machinery areas. Ballustrades are finished in brass, juxtoposing the earthy and white tones of plastic. The shell created from 3D Printed plastic shell structure takes centre stage with green cascading from above.

LSA2021 103

LSA2021 104

M2.38, Enzyme Fermenters and Tropical Gardens. Visualisation displaying the enzyme fermenters, in which specific enzymes are produced which break the polymer chains of the plastic into the bioreactors. They are surrounded by pools and tropical greenery. The heat it produces allows for the cultivation of tropical gardens, creating a warm humid bio-dome.

LSA2021 105

WILL DUDLEY (Y5)

“House of Reflection- The Hotspur Home for The Lost”

A project focusing on the interpretation of the turbulence of severe mental disorders. They are spaces to offer people chances to stop and contemplate, or discuss their own mental health. The key driver of the design was the idea that you can’t know what’s going on inside someone’s head until they tell you or until cracks in their ‘normal’ behaviour start to appear. Narratives were

LSA2021 106

intepreted from Roald Dahl’s short story: the opening story to the collection called Madnes, a talk given by Casey Gerald: The Gospel of Doubt and a case study by Stephen Grosz, in his book, The Examined Life.

M2.39, The Rehabilitation stage of the collage series explores the potential interactions between the themes of the character and the existing fabric within Hotspur House. In this image, Mr. Thrum’s sound and plantlife imagery have been portrayed in a far more spatial manner. As a greenhouse would be a suitable space to grow sustainable plant life, Mr. Thrum’s intervention is shown occuring in the roof section of the tallest existing building. Mr. Thrum is depicted as a composer in this image in reference to my first ideas regarding his potential treatment.

“Thank you, Doctor,’ he said, and he nodded his head again and dropped the axe and all at once he smiled, a wild excited smile, and quickly the doctor went over to him and gently he took him by the arm and he said: Come on, we must go now...”

Mr. Fowler’s character is based on the father character in Max Porter’s book, Grief is the Thing with Feathers.

LSA2021 107

M2.40, Mental illness is often considered an ‘invisible illness’ because there are many symptoms which can’t be seen or measured. Unfortunately this is true for many of the most severe mental illnesses. The problem is people dismiss mental illness as not real. If someone has never personally experienced a mental disorder, they have no frame of reference to help them truly comprehend and empathise as they attempt to gauge the severity of the issue. The most dangerous accusation or most inconsiderate question is regarding whether these symtpoms are real or not. Even more dangerous is that sometimes the person experiencing the issues cannot accept or acknowledge their own symptoms. A good example is a headache. No test can prove or disprove that someone has a headache, yet we have all experienced the pain of one and can accept it as a real condition, with capacity to be equally as painful as a physical injury.

M2.41, This series intends on portraying the effect of a mental disorder upon our perception of reality and therefore our daily life, the slow creep of our reality refracting to the point we no longer recognise it. This discussion begins with out perception of ‘normal’. The vast majority of people you walk past in the street are likely automatically categorized as normal people. This is a broad and diverse group but that’s normal. Each of those people appears normal because their external appearance falls within our range of tolerance for what can be considered normal. However, we now know that roughly a quarter of them are likely struggling with a mental disorder. Prior to learning how common it was, if we had learned of somebody’s dissociative disorder, PTSD, OCD, etc - would we still have been able to class them as normal? These afflicted people may now deviate from our own sense of normal and it will affect how we interact with them.

LSA2021 108

M2.42, We are often secure in our own sense of what’s normal because everyone else agrees with us. We can confirm that everyone is seeing what we’re seeing, hearing what we’re hearing etc. So what do we do when somebody says they are seeing and hearing things nobody else is? It’s hard to really believe them but that’s the life of those suffering from psychotic disorders. This is the second core theme of this series of images. A psychotic episode is what we call someone’s perception or interpretation of reality, which exists only for them. We say they have ‘lost touch’ with reality. We can understand these experiences as hallucinations and delusions, these are words we know the definition of and are concepts which can easily be explained. Many of us probably feel as though we’ve hallucinated before, maybe during a rough fever or after administration of psychoactive agents but they’re temporary so we haven’t completely lost touch, we’re just a bit ‘out of it’. This is normal.

M2.43, The issue lies in the fact that when this lasts longer than a few hours or a few days, it can be incredibly disruptive to daily life. The people around those with a form of psychosis start to lose their frame of reference in their comprehension of the condition as it extends beyond the normal limits. This is where it starts to become messy, if the conversation breaks down, we lose touch with each other and the person suffering may end up feeling cut off from what could be their support. We may feel out of our depth when dealing with this topic so we say “get help” or “you need therapy” - while reasonable advice, it distances them from us. From what I’ve read and learned so far, the best advice I can give to mitigating this distance is to engage with their therapy or rehabilitation. Rather than saying “don’t worry there’s nothing there/ it’s all in your head”, start by telling people with psychosis that you believe them and that you’re there for them. This final image represents the inevitable splitting of all things; the splitting of reality, the split from society, the muddled overlap of experiences.

LSA2021 109 M2.36