OPTION 8: CULTURE AND IDENTITY

01 PHYSICAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

02 CULTURAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

03 NATIONALITY AND THE NATION STATE

04 IDENTITY AS A CONCEPT IN SWITZERLAND

First published 2024

The Educational Company of Ireland

Ballymount Road

Walkinstown

Dublin 12

www.edco.ie

A member of the Smurfit Kappa Group plc

© Lee O’Donnell, 2024

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without either the prior permission of the publishers or a licence permitting restricted copying in Ireland issued by the Irish Copyright Licensing Agency, 63 Patrick Street, Dún Laoghaire, Co Dublin.

Editor: Dog’s-ear

Design: Ailbhe Hooper

Proofreaders: Dog’s-ear, Jane Rogers

Layout and illustrations: Compuscript

While every care has been taken to trace and acknowledge copyright, the publishers tender their apologies for any accidental infringement where copyright has proved untraceable. They would be pleased to come to a suitable arrangement with the rightful owner in each case.

Web references in this book are intended as a guide for teachers. At the time of going to press, all web addresses were active and contained information relevant to the topics in this book. However, The Educational Company of Ireland and the authors do not accept responsibility for the views or information contained on these websites. Content and addresses may change beyond our control and pupils should be supervised when investigating websites.

ii

OPTION 8: CULTURE AND IDENTITY 1. PHYSICAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY 2 2. CULTURAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY 23 3. NATIONALITY AND THE NATION STATE 54 4. IDENTITY AS A CONCEPT IN SWITZERLAND 76 iii CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In presenting The Natural World, Option 8: Culture and Identity I extend my deepest gratitude to a circle of individuals whose support and belief have been crucial. My partner Aoibheann deserves special mention for her unwavering love and belief in my capabilities. Your encouragement has been fundamental to this journey I am equally indebted to my mother Sinead and my brother Evan, whose support has been a cornerstone in all my endeavours.

I am profoundly grateful to the team at Edco for offering me the platform to express my enthusiasm for teaching and learning. A heartfelt thank you to Declan, whose expertise and guidance were invaluable throughout this project, and to Neil, whose dedication and insight were crucial in bringing the digital dimension of this book to life.

I extend my appreciation to our editors, Emma and Rónán, whose keen eye, constructive criticism, and meticulous approach were instrumental in refining every detail of this book

Lastly, my colleagues and students at Woodbrook College deserve my deepest thanks. Your daily inspiration and motivation have been a source of continuous encouragement, greatly contributing to the creation of this work.

Lee O’Donnell

PHOTO ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

For permission to reproduce photographs and other images, the author and publisher gratefully acknowledge the following:

Alamy: p.11 © Contraband Collection, Inc.; p.15 © PA Images; p.17 © GRANGERHistorical Picture Archive; p.18 © Everett Collection Historical; p.19 © Geopix; p.27 © Glasshouse Images; p.42 © Smith Archive; p.44 © NurPhoto SRL; p.47 © Associated Press; p.50 © reallifephotos; p.60 © Associated Press; p.66 © Associated Press; p.68 © dpa picture alliance; p.69 © Idealink Photography; p.73 © PA Images; p.74 © Associated Press. Getty Images: p.43 © Independent News and Media; p.48 © Charles McQuillan; p.49 © David Fitzgerald; p.57 © AFP. iStock: p.5 © JohnnyGreig; p.73 © TCrowePhoto. Shutterstock: p.1 © Lightspring; p.20 © Aaron of L.A Photography; p.23 © Nanzeeba; p.28 © Wjarek; p.29 © Shabtay; p.30 © Michiel Vaartjes; p.33 © Antlii; p.37 © Peter Krocka; p.38 © David Pimborough; p.47 © CREATISTA; p.51 © StockphotoVideo; p.52 © A G Baxter; p.54 © Shebeko; p.58 © Stocksvids; p.65 © Everett Collection; p.76 © Jaro68; p.80 © Casper1774 Studio; p.81 © Leonard Zhukovsky; p.81 © yangjlin; p.82 © stockcreations.

iv

OPTION 8: CULTURE AND IDENTITY

01 PHYSICAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

02 CULTURAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

03 NATIONALITY AND THE NATION STATE

04 IDENTITY AS A CONCEPT IN SWITZERLAND

1

PHYSICAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

CHAPTER 01

SYLLABUS LINK

8.1 POPULATIONS CAN BE EXAMINED ACCORDING TO PHYSICAL AND CULTURAL INDICATORS. CULTURE AND IDENTITY ARE TIED TO IDEAS OF ETHNICITY, WHICH INCLUDE RACE, LANGUAGE, RELIGION, AND NATIONALITY

KNOWLEDGE RETRIEVAL

Retrieval Quiz

1. State the population of Brazil.

2. Where is the population of Brazil concentrated?

3. What percentage of Brazil’s population lives in urban areas?

4. State the population density of São Paulo.

5. Discuss the factors that contributed to the uneven population distribution in Brazil.

2

LEARNING INTENTIONS

1. Outline and define race as a geographical concept.

2. Explain the impact of colonialism and migration on global racial patterns.

3. Describe the challenges of multiculturalism with reference to examples from Ireland.

4. Analyse the development of racial conflict in society in the United States.

KEYWORDS

Race Social construct

Biological realityShared genetic make-up

Caucasian East Asian African

East Asian migration African migration

Global slave trade Migration

Multicultural societies

Impact of colonialism

Cultural assimilation African diasporaCounter migration

Refugee movement Cross-cultural interactions

Indo-European migration

European colonisation

Racial hierarchies

Economic opportunities

Language barriers Xenophobia and racism

Challenges of asylum and immigration Russian invasion of Ukraine War in Syria and Afghanistan

Integration Right-wing politics

Language diversity

Direct Provision system Asylum seekers

TOPIC 1.1: Geographical Writing for Culture and Identity

The Culture and Identity section of the Leaving Certificate Geography syllabus has a different marking scheme from the rest of the written paper. It is the only part of the written paper that takes into consideration overall coherence as part of the marking scheme. This means that your answer must be written with a logical structure and must contain a consistent flow.

In order to ensure your answer is constructed with a logical structure and consistent flow, it is best to organise your answer into different aspects you are going to discuss. An aspect can be defined as an area of discussion that is relevant to the question being asked.

In each Culture and Identity answer, you will structure your answer into either three or four aspects:

• If you are writing about three aspects, you must write a minimum of 8 SRPs per aspect.

• If you are writing about four aspects, you must write a minimum of 6 SRPs per aspect.

MARKING SCHEME

MARKING SCHEME: 3 ASPECTSMARKING SCHEME: 4 ASPECTS

Name aspect = 4 marksName aspect = 3 marks

Discuss for 8 SRPs = 16 marksDiscuss for 6 SRPs = 12 marks

Overall coherence = 20 marksOverall coherence = 20 marks

A1 (20m) + A2 (20m) + A3 (20m) + OC (20m) = 80 marks A1 (15m) + A2 (15m) + A3 (15m) + A4 (15m) + OC (20m) = 80 marks

3 CHAPTER 1 | |PHYSICAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

TOPIC 1.2: Race as a Geographical Concept

RACE

In geography, race refers to a concept that is related to human diversity, focusing on physical characteristics that people inherit from their ancestors. It’s important to note that race is a social construct, not a biological reality. This means that it was created by societies to classify and group people based on certain physical traits, such as skin colour, hair type/colour, facial features and body type/structure.

Understanding race begins with recognising that humans, regardless of their physical differences, belong to one species – Homo sapiens. Our shared genetic make-up is remarkably similar, with around 99.9 per cent of our DNA being identical. However, even though we share so much genetic material, small variations in certain genes can lead to observable physical differences, giving rise to the concept of race

Papua NewGuineans, Ethiopians, Hadza, and Tanzanians

Africans (except the San), South Asians, and Australo-Melanesians

East Africans, Hadza, San, South Asians, and Australo-Melanesians

Africans and East Asians

years ago

years ago

Europeans and South Asians

Europeans, East Asians, Indians, and Native Americans

Europeans, San, East Asians, and Africans Europeans, San, and East Asians

Figure 1.1

Concept map showing how different races have developed due to variations in gene combinations that affect the colour of skin

For example, let’s consider skin colour. In Ireland, where we are, most people have light skin because of historical factors and the impact of latitude on sunlight exposure. However, it’s important to remember that skin colour can vary widely among individuals, even within Ireland or any other ‘racial’ group. Skin colour is mainly influenced by the amount of melanin in our skin, which helps protect us from harmful UV (ultraviolet) radiation from the sun.

RACIAL GROUPS

Most racial groups in the world are rooted in three different races:

• Caucasian

• East Asian

• African.

Throughout history, the movement and dispersal of racial groups has been influenced by a combination of geographic factors, including climate, geography, and human migration patterns. This topic will discuss how each of the three racial groups began to spread throughout the world.

4 THE NATURAL WORLD – OPTION 8

Gene variants associated with dark pigmentation

Da rk -t o-L igh t mu t ation

Gene variants associated with light pigmentation

SLC24A5

29,000

Sub-Saharan

250,000

Da rk -t o-L igh t mu t ation

Li gh tto -dark mu t ation 345,000 years ago

DDB1

Li gh tto -dark mu t ation 996,000 years ago MFSD12

HERC2

CAUCASIAN

The Caucasian racial group has its origins in the region surrounding the Caucasus Mountains, which spans the border between Europe and Asia. Over thousands of years, various groups from this region migrated and spread to different parts of the world.

One notable migration was the Indo-European migration, around 4000 to 2500 BCE. Indo-European-speaking peoples, believed to be ancestors of modern-day Europeans, moved westward and eastward, eventually settling across Europe, Southwest Asia, and the Indian subcontinent.

EAST ASIAN

The East Asian racial group has its roots in East Asia, which includes countries such as China, Japan and South Korea. The movement and dispersal of East Asian populations has been shaped by factors such as the vast Pacific Ocean, mountain ranges, and the climate.

The peopling of the Japanese archipelago is a significant example of East Asian migration. The first inhabitants are believed to have migrated from mainland Asia over 30,000 years ago, crossing land bridges during periods of lower sea levels during ice ages.

AFRICAN

The African racial group has the most ancient origins. Africa is the birthplace of humankind. The movement of African populations across the continent and beyond has been influenced by factors such as the Sahara Desert, river systems, and the availability of resources.

The ‘Out of Africa’ theory suggests that Homo sapiens originated in Africa and gradually migrated to other parts of the world around 70,000 to 100,000 years ago. These early human migrations led to the colonisation of Asia, Europe and eventually other continents.

Geography plays a crucial role in shaping the distribution and movement of human populations. Understanding these historical movements helps us appreciate the interconnectedness of different cultures and societies. Embracing diversity and respecting one another’s heritage are essential steps towards building a more inclusive and understanding global community.

5 CHAPTER 1 | |PHYSICAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

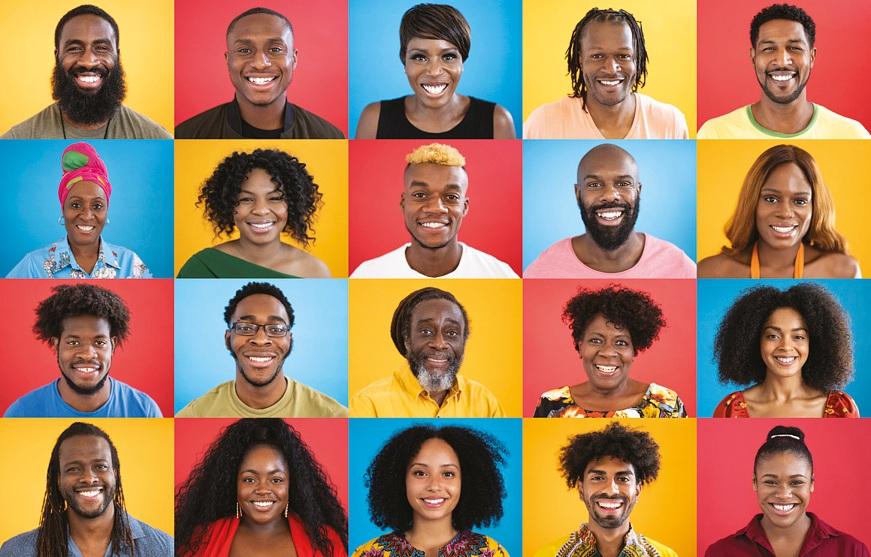

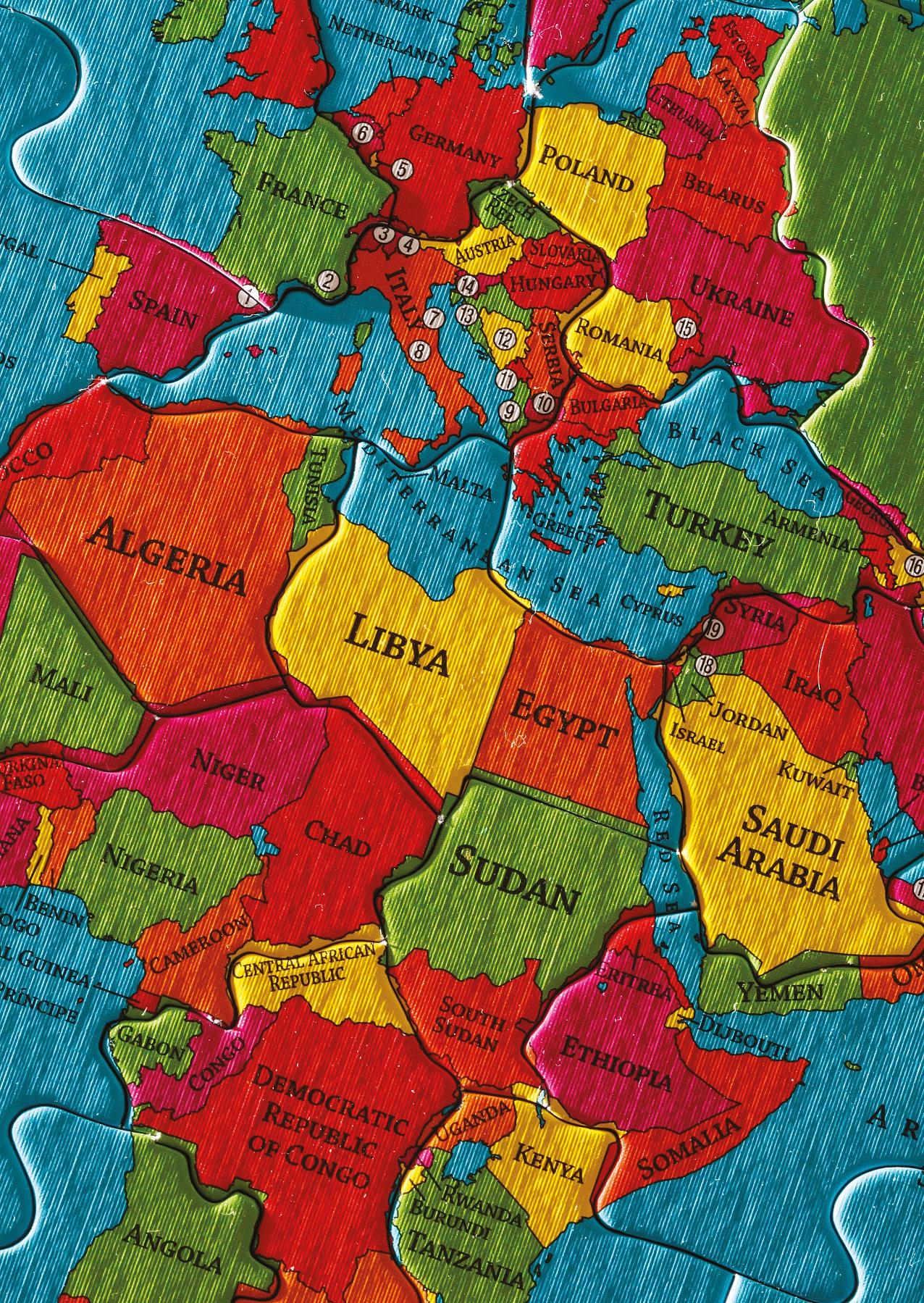

Figure 1.2

There is more diversity in Africa than on the rest of the continents combined because modern humans originate from there and lived there the longest

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING

Basic Knowledge

1. What does the term ‘race’ refer to in geography?

2. Is race a biological reality or a social construct? Explain your answer.

3. What are some physical characteristics that are used to classify and group people based on race?

Developed Knowledge

1. Describe the genetic make-up of humans and the percentage of DNA that is shared among individuals.

2. Explain how small variations in certain genes can lead to observable physical differences, giving rise to the concept of race

3. Discuss the cause of skin colour and how it can vary among individuals within the same racial group.

Advanced Knowledge

1. Compare and contrast the origins and dispersal patterns of the Caucasian, East Asian, and African racial groups.

2. Investigate the impact of geography, climate, and human migration patterns on the movement and dispersal of racial groups throughout history.

TOPIC 1.3: The Impact of Colonialism and Migration on Racial Patterns

INTRODUCTION

Before the period of European colonisation, multicultural societies did not exist However, as a result of intensive colonisation, the development of a global slave trade and increased levels of migration, racial patterns across the globe have been transformed. This topic will investigate the impact of colonisation, the slave trade and migration on racial patterns.

IMPACT OF COLONIALISM

Colonialism refers to the historical practice of powerful countries establishing control over other territories, exploiting their resources, and exerting dominance over the local populations. The era of colonialism, which lasted from the fifteenth to the twentieth century, has had a profound impact on global racial patterns. The period of colonialism resulted in people from different racial backgrounds coming into contact, which in turn led to cultural and genetic mixing.

Spanish explorers, such as Francisco Pizarro, arrived in the Americas in the late fifteenth century, claiming vast territories for Spain. The Spanish brought with them European diseases, which decimated indigenous populations. The colonisers also established the encomienda system, which exploited native labour and further entrenched racial inequalities. The intermixing of Spanish and indigenous populations gave rise to a new racial group known as mestizos.

When the British East India Company arrived in India in the seventeenth century, it gradually gained control over various regions through economic and military dominance. British colonial rule in India lasted until 1947. During this time, the British imposed their language, culture and administrative systems, which led to the formation of new racial identities. The British considered themselves superior and viewed the native Indian people as inferior, which led to social hierarchies and racial discrimination.

6 THE NATURAL WORLD – OPTION 8

3

In the late nineteenth century, Belgium colonised the Congo in Central Africa under King Leopold II’s rule. The Belgian colonial administration exploited the Congolese people, subjecting them to forced labour and extreme brutality This horrific chapter of colonialism resulted in the loss of millions of Congolese lives. The Belgian authorities implemented policies that favoured the lighterskinned Congolese, further exacerbating racial divisions.

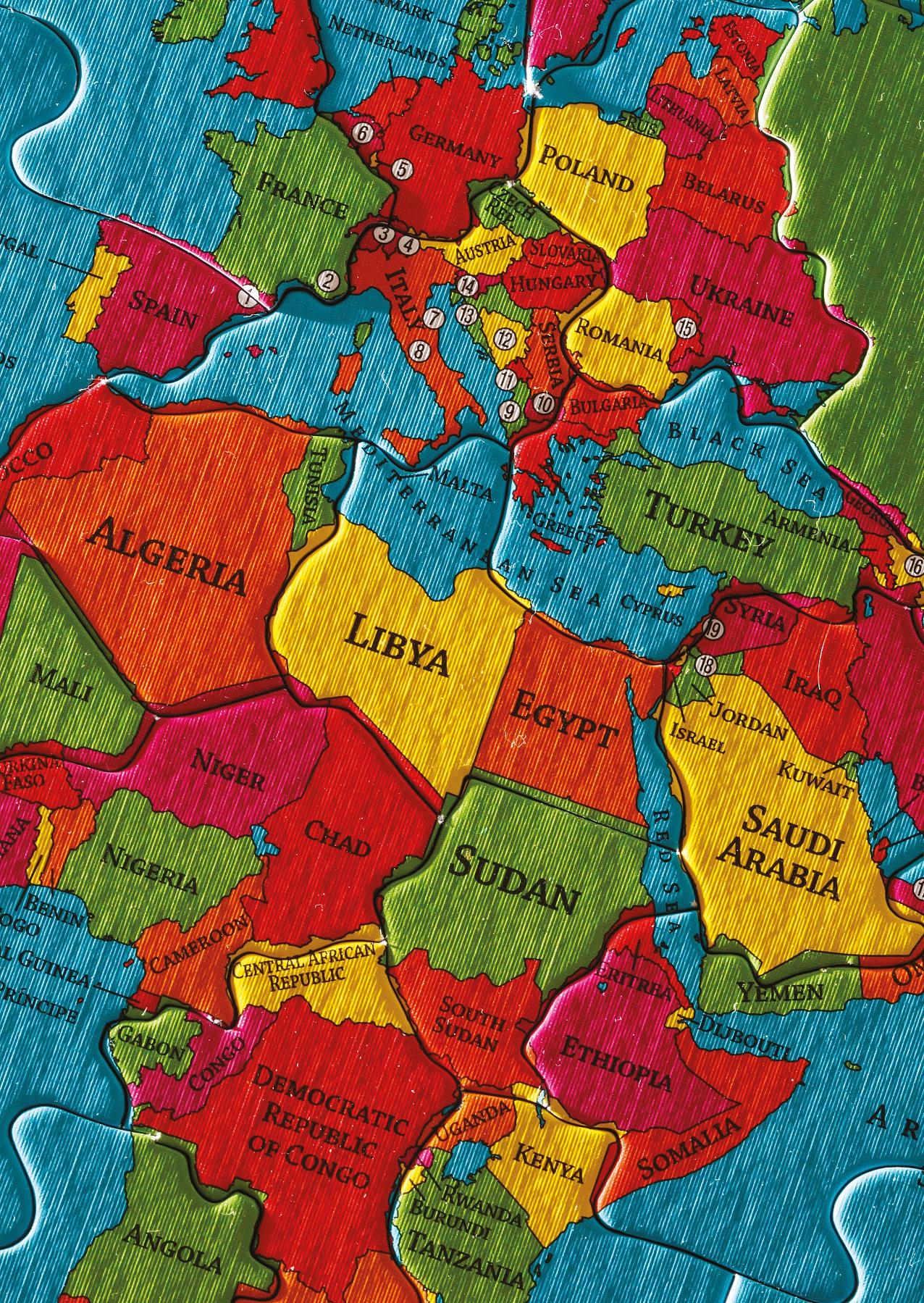

Colonies after the Berlin Conference of 1884

IMPACT ON GLOBAL RACIAL HIERARCHIES

Colonialism contributed to the establishment of global racial hierarchies, with Europeans often considering themselves superior to the indigenous populations of colonised regions. This idea of racial superiority led to widespread discrimination, exploitation and marginalisation of native populations. It also fostered the notion of ‘whiteness’ as a standard of beauty and intelligence, reinforcing harmful stereotypes.

CULTURAL AND SOCIAL ASSIMILATION

Colonial powers sought to assimilate the native populations into their own cultural norms and traditions. Indigenous languages, beliefs and practices were often suppressed, which eroded local identities and cultural diversity This assimilation process further influenced global racial patterns as it created a homogenising effect on diverse populations.

7 CHAPTER 1 | |PHYSICAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

Spanish French French French French Belgium French French West Africa African

British British British Portuguese Portuguese Portuguese Free Free British German German German German British British British British British British British Spanish Spanish Italian Italian Italian French British

Figure 1.3

Map of Africa outlining the former colonisers of the continent

LINGERING EFFECTS TODAY

The legacy of colonialism is still evident today, as many post-colonial societies continue to grapple with the social, economic and political consequences of their colonial past. Racial inequalities, discrimination and ethnic tensions persist in various regions that were once colonised. Understanding the impact of colonialism on global racial patterns helps us recognise historical injustices and work towards a more just and inclusive world. As geographers, exploring this complex history can foster empathy and appreciation for diverse cultures and advance efforts to dismantle racial inequalities and promote social justice.

CASE STUDY: Impact of colonialism on Brazil’s racial patterns

The colonisation of Brazil is a significant historical event that shaped the country’s culture, society and geography. The colonisation of Brazil began in 1500 when Portuguese explorers landed on the north-eastern coast of present-day Brazil. The Portuguese claimed the territory for their empire, starting a process that would last for centuries. In the early years of colonisation, the Portuguese focused on extracting valuable natural resources, particularly Brazilwood (pau-brasil), which was highly sought after for its red dye. This exploitation led to the establishment of small trading posts along the coast.

Maranhão

Ceará

Rio Grande

Paraíba

Itamaracá

Pernambuco

Bahia de Todos os Santos Ilhéus

Porto Seguro

Espírito Santo

São Tomé

São Vicente

Rio de Janeiro

Santo Amaro

São Vicente

Santana

8 THE NATURAL WORLD – OPTION 8

Figure 1.4

How the east coast of Brazil was divided into colonies in 1543

During the sixteenth century, the cultivation of sugarcane became a booming industry in Brazil. The Portuguese established large-scale sugar plantations and brought enslaved Africans to work on them. The transatlantic slave trade had a profound and lasting impact on Brazil’s demographic and racial make-up.

After centuries of Portuguese rule, Brazil declared its independence from Portugal in 1822. The legacy of colonisation can be seen in Brazil’s culture, language (Portuguese) and racial diversity. The mixing of indigenous, European and African populations during the colonial period has contributed to Brazil’s vibrant and diverse society

The period of colonialism had a significant impact on racial mixing in Brazil. Racial mixing can be defined as when people of different races have children together. Before Portuguese colonists arrived in the 1500s, Brazil was mostly populated by nomadic tribes As Portuguese colonists began to settle in the region, slaves were brought into the country from West Africa and forced to work harvesting natural resources such as sugar and coffee. As a result of the large number of Europeans and African slaves who settled in Brazil due to colonialism, many people in the country have mixed ancestry The two main ethnicities in Brazil are defined as white and Afro-Brazilian, with 47 per cent of the population describing themselves as white and 43 per cent describing themselves as Afro-Brazilian.

Conversely, 500 years ago in Brazil the native population

9 CHAPTER 1 | |PHYSICAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

Brazilian diaspora: Brazil + 1,000,000 + 100,000 c.4.2 million (2020) 1,900,000 Portugal 276,000 Paraguay 240,000 United Kingdom 220,000 Japan 211,000 Italy 161,000 Spain 156,000 Germany 144,000 Canada 122,000 89,000 France Argentina 81,000 Switzerland 76,000 French Guiana 72,000 Australia 57,000 Ireland 70,000 + 1,000 + 10,000

United States

No data

Figure 1.5

The Brazilian diaspora today

was estimated at between 3 million and 6 million people. However, only 200,000 of those remain due to the impact of colonialism. The depopulation of native Brazilians can be attributed to the spread of European diseases and the violent treatment by European settlers Some historians have referred to this process as genocide because over 80 Brazilian tribes were decimated, and the native population declined by over 80 per cent In addition, there is a growing Brazilian diaspora around the world, as a culture of emigration has developed in the country since the start of the 2000s. Large Brazilian populations reside in the United States, Paraguay, Japan, England, Spain and France. On average, about 100,000 Brazilians have emigrated per year since 2000. It is estimated that 4.2 million Brazilians are currently living abroad, with 1.9 million of those in the United States. Eurostat currently estimates that there are 70,000 Brazilians living in Ireland, which is a threefold increase since 2006. Around 64 per cent of those Brazilians are based in County Dublin.

IMPACT OF THE TRANS-ATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE

The trans-Atlantic slave trade was a tragic and inhumane historical event that profoundly shaped global racial patterns. Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, millions of Africans were forcibly captured, enslaved and transported across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas, particularly to regions such as North America, the Caribbean and South America. The Middle Passage, the journey across the Atlantic, was marked by unimaginable suffering, with countless lives lost.

TRIANGULAR TRADE

Figure 1.6

Trans-Atlantic slave trade

The slave trade caused a significant demographic impact on Africa, as large numbers of young and able-bodied individuals were taken away from their communities. This disrupted traditional societies and economies, leaving lasting scars on the continent. The trans-Atlantic slave trade is estimated to have forcibly transported around 12.5 million Africans to the Americas

The trans-Atlantic slave trade perpetuated the idea of racial superiority, with European slaveowners considering themselves to be superior to Africans. This notion of white supremacy led to the dehumanisation of enslaved Africans and entrenched racial hierarchies, which continue to have far-reaching consequences.

CREATION OF THE AFRICAN DIASPORA

Enslaved Africans brought to the Americas were subjected to unimaginable hardships and forced labour on plantations. The descendants of these Africans, known as the African diaspora, now form significant populations in countries and regions such as the United States, Brazil and the Caribbean

The forced migration of Africans led to cultural and genetic mixing with indigenous populations and European colonisers. This blending of diverse cultures gave rise to new societies with unique cultural expressions which we can observe in music, art and language.

The legacy of the trans-Atlantic slave trade is still evident today. The African diaspora continues to face challenges, including systemic racism, socio-economic disparities, and cultural identity issues The impact of this historical injustice is felt not only in the Americas but also in Africa and beyond.

10 THE NATURAL WORLD – OPTION 8

AFRICA ATLANTIC OCEAN PACIFIC OCEAN CARIBBEAN ISLANDS Rawmaterials Manu facturedgoods EnslavedAfricans EUROPE 13Colonies

NORTH AMERICA SOUTH AMERICA

IMPACT OF COUNTER MIGRATION ON RACIAL PATTERNS

The period after World War II witnessed significant counter migration, where people moved back to their countries of origin or sought new opportunities in different regions. This movement had profound effects on racial patterns across the world, shaping societies, cultures, and economies.

After World War II, many colonised nations gained independence. This meant the return of European settlers to their home countries. For instance, the end of British colonial rule in India in 1947 resulted in the repatriation of British colonial administrators and settlers back to the United Kingdom. This return migration influenced racial dynamics in both the colonised nations and the home countries of the colonisers.

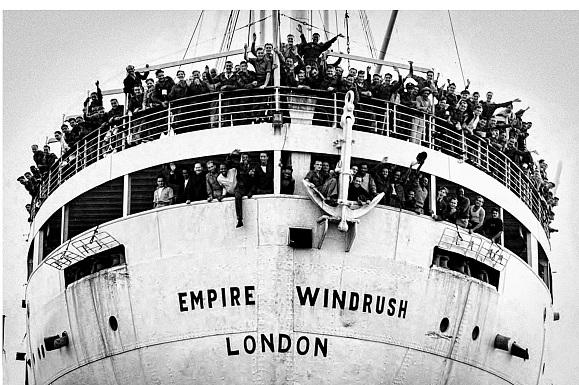

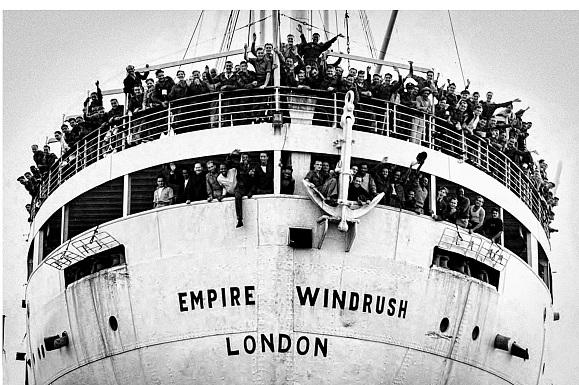

The EmpireWindrusharrives in England in 1948, carrying migrants to the UK to fill labour shortages after World War II.

Additionally, the post-war period saw significant migration from the Caribbean to the United Kingdom In the 1950s and 1960s, the British government encouraged workers from the Caribbean to move to the UK to fill labour shortages The Windrush Generation (named after the ship that carried the first group of migrants) contributed to the racial diversity of the UK. However, this migration also led to racial tensions and challenges, particularly in terms of housing and employment discrimination.

Post-war counter migration was often driven by economic opportunities and advancements in transportation. Skilled professionals, such as engineers, doctors, and scientists, sought work in developed countries, contributing to the phenomenon of brain drain in their home countries. For example, Indian professionals migrated to the United States, the UK and other countries, becoming an integral part of the workforce of their host countries This legacy of skilled Indian migrants can still be seen today. In 2022, 49 per cent of Indian immigrant adults moving to the US held a graduate or professional degree

The aftermath of World War II witnessed the displacement of millions due to conflicts and persecution. Many sought refuge in other countries, leading to the growth of refugee and asylumseeking populations. For example, the aftermath of the Vietnam War saw a significant number of Vietnamese refugees settling in the United States, Australia and other countries. These refugee movements influenced racial demographics and cultural landscapes in host nations.

IMPACT ON RACIAL AND ETHNIC RELATIONS

Post-war counter migration affected racial and ethnic relations in both the origin countries and the destination countries The arrival of diverse populations challenged existing racial hierarchies and fostered cultural exchanges However, it also led to social tensions and debates about national identity and assimilation. For instance, the influx of immigrants from former colonies into European countries has sparked discussions about multiculturalism and integration.

GLOBALISATION AND CROSS-CULTURAL INTERACTIONS

Counter migration played a vital role in facilitating cross-cultural interactions and fostering a more interconnected world The movement of people across borders led to the exchange of ideas, customs and traditions, contributing to the globalisation of cultures This global exchange has had lasting impacts on art, music, cuisine, and other aspects of everyday life.

11 CHAPTER 1 | |PHYSICAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

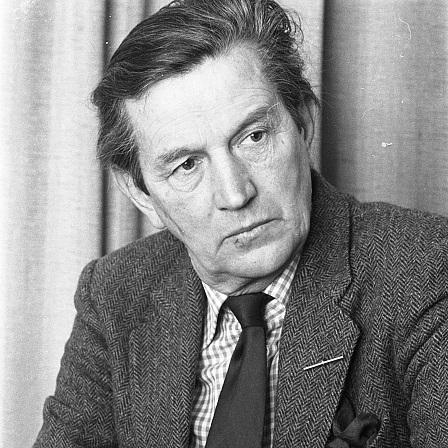

Figure 1.7

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING

Basic Knowledge

1. What is colonialism, and how did it impact global racial patterns?

2. Name three colonial powers mentioned in the text, and identify regions they colonised.

3. How did the trans-Atlantic slave trade contribute to the creation of the African diaspora?

Developed Knowledge

1. Describe the impact of colonialism on Brazil’s culture, society and racial diversity.

2. Discuss the demographic consequences of the trans-Atlantic slave trade on Africa and the Americas.

3. Outline the reasons behind post-World War II counter migration and its effects on racial and ethnic relations.

Advanced Knowledge

1. Analyse the long-term effects of colonialism on racial hierarchies and discrimination in post-colonial societies.

2. Compare and contrast the racial patterns resulting from colonialism in Brazil and the Americas with those in Africa and other colonised regions.

TOPIC

1.4: Multiracial Societies

MULTICULTURAL SOCIETIES

A multicultural society is a community or nation where people from diverse cultural backgrounds coexist, interact and contribute to the social fabric In such societies, individuals embrace and celebrate their unique customs, traditions, languages and beliefs. The richness of cultural diversity fosters an environment of tolerance, understanding and mutual respect among different ethnic groups

However, as the world has become interconnected and diverse, a number of challenges have arisen that are associated with multicultural societies.

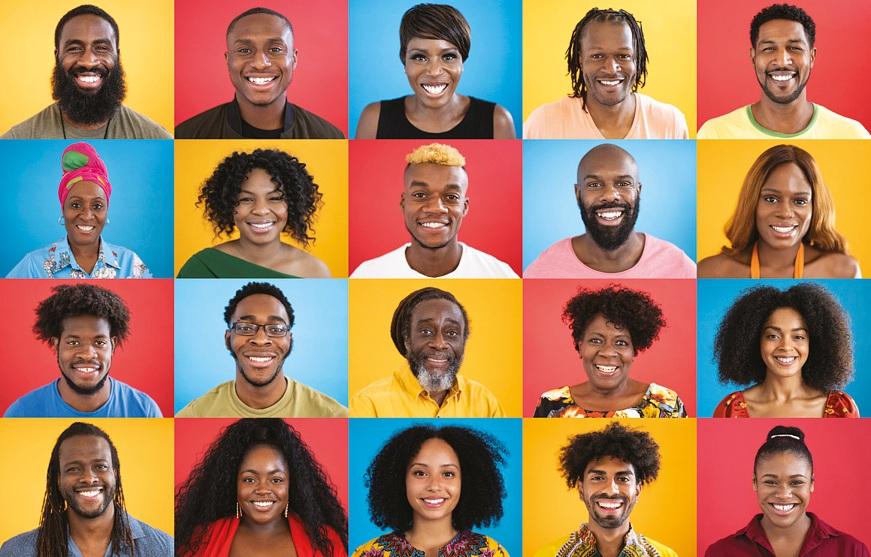

Figure 1.8

As a result of persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations, or events seriously disturbing public order, there has been a sharp increase in the number of people forcibly displaced from their homes in recent decades.

1. ASYLUM AND IMMIGRATION

Multicultural societies often encounter challenges related to asylum and immigration. Asylum seekers fleeing conflicts and persecution may face difficulties in integrating into their host communities due to language barriers, cultural differences and limited access to resources. This challenge has been exacerbated in recent years with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the wars in Syria and Afghanistan For example, in 2023 the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees reported that there were 108.4 million forcibly displaced people worldwide with over 53 per cent of those people coming from the three countries mentioned above.

12 THE NATURAL WORLD – OPTION 8

3

2000 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 2007 Pe op le in mi llions 2013 2022

2. LANGUAGE BARRIERS

Language diversity can be a challenge in multicultural societies. With people speaking different languages, effective communication becomes crucial for social cohesion and economic integration. Language barriers can hinder access to education, healthcare, and employment opportunities. In Belgium, where there are three official languages (Dutch, French and German), language differences have been an ongoing challenge for national unity.

3. XENOPHOBIA AND RACISM

Xenophobia and racism can arise in multicultural societies, driven by fear or prejudice against people from different cultural backgrounds. These attitudes can lead to discrimination, social exclusion, and even violence. To address these issues as a society, we need to promote diversity in education, foster intercultural understanding, and implement policies that combat discrimination. In 2022 the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights reported that 31 per cent of people surveyed in the EU experienced discrimination based on their ethnic or immigrant background.

CASE STUDY: Challenges of Multiculturalism and Integration in Ireland

Since Ireland became a member of the EU in 1973, Ireland has quickly become one of the most rapidly growing, multicultural societies in Europe. Since 2000, Ireland has the joint fastest growing population in Europe, as the country has seen a 32 per cent increase in population.

The 2022 census in Ireland indicated that there are 631,785 non-Irish nationals living in Ireland who originate from over 200 countries This number represents an increase from the 2016 census and accounts for 12 per cent of the population. The biggest non-Irish groups were Polish and UK citizens, followed by Indian, Romanian and Lithuanian. Brazilian, Italian, Latvian and Spanish citizens were also among the larger non-Irish groups

Figure 1.9 Europe’s population change 2000–2021. Notice that Ireland has one of the fastest growing populations.

While the levels of immigration and integration and multiculturalism in Ireland have increased dramatically as a result of EU enlargement and increased economic development in Ireland, there

CHAPTER 1 | |PHYSICAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

32 32 14 30 21 10 Population change from 2000 to 2021 (%) –33% 33% 17 7 –5 –20 –20 20 10 13 11 1 12 2 2 6 1 –1 –11 –5 –9 –4 –16 –15 –2 17 4

13

are still concerns in Irish society regarding the acceptance of multiculturalism. According to the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance Report on Ireland in 2022, the country has made some progress towards tackling racism in Irish society However, there are areas in which further improvements are needed. The report specifically outlines the damage caused by hate speech, hate crimes and ethnic profiling. The report also states that supporting the needs of asylum seekers would facilitate the integration process in Ireland.

The integration of non-Irish nationals into Irish society faces a complex set of challenges that must be addressed to ensure the success of Irish growth and the development of an inclusive multicultural society.

1. RACIAL DISCRIMINATION

Racial discrimination can hinder the integration of non-Irish nationals, leading to social exclusion and unequal treatment. Discrimination based on ethnicity, nationality or race prevents individuals from fully participating in society and accessing equal opportunities. Findings from research published in 2023 state that almost two-thirds (63 per cent) of international students in Ireland have experienced and/or witnessed racism The most common form of racism experienced or witnessed was verbal (42 per cent). This was followed by ‘indirect’ racism (39 per cent), e.g. by being treated differently or unfairly due to their race, particularly in the workplace. Following this was physical racism (12 per cent), including physical assaults. Additionally, only 10 per cent of international students who experienced an incident of racism reported it to the authorities. Of those who did report an incident, 67 per cent were dissatisfied with the response they received. While the levels of multiculturalism and integration have increased in Ireland, results from this survey suggest that racism and xenophobia are still prevalent issues in society

2. LANGUAGE BARRIERS

Language barriers can impede effective communication and social interaction, making it challenging for non-Irish nationals to integrate fully. Access to language courses and support services is vital to help immigrants improve their language skills, and enhance their ability to engage with the broader community.

3. APPLICATION PROCESS

Navigating the immigration and residency application process can be complex and timeconsuming. Lengthy waiting periods and paperwork can cause frustration and uncertainty for non-Irish nationals seeking to establish themselves in Ireland. For example, in 2022 the average time for asylum seeker cases to be processed to completion was 18 months. Streamlining and simplifying the application process would contribute to smoother integration.

4. LACK OF DOCUMENTATION

Some non-Irish nationals may arrive in Ireland without proper documentation, often because they are seeking asylum or escaping conflict. Lack of documentation can lead to difficulties in accessing essential services, employment and housing. Addressing the needs of undocumented migrants is a significant challenge that requires compassionate and comprehensive solutions.

14 THE NATURAL WORLD – OPTION 8

15% Poland 3% Spain 3% Latvia 13% UK 3% Italy 5% Lithuania 7% Romania 7% India 4% Brazil 40% Other

Figure 1.10

Non-Irish population percentages, 2022 census

5. RISE OF RIGHT-WING POLITICS

The rise of right-wing politics in Europe, including Ireland, has significant implications for the integration of non-Irish nationals into the country. Right-wing political ideologies often promote nationalist sentiments, anti-immigrant attitudes, and a focus on preserving traditional national identity. Right-wing politics may fuel xenophobia and discrimination against non-Irish nationals, particularly those from diverse cultural backgrounds. This hostile environment can lead to social exclusion, hinder opportunities for cultural exchange, and create barriers to acceptance and belonging.

Furthermore, right-wing political parties tend to advocate for restrictive immigration policies and stronger border controls. These policies can make it more challenging for non-Irish nationals to enter the country legally and obtain residency or citizenship. The potential tightening of immigration rules can create uncertainty and anxiety for immigrants seeking to integrate into Irish society. This can cause negative narratives and stereotypes to emerge, which leads to reduced support for social services and integration programmes. This lack of support can hinder immigrants in accessing essential resources and services, making their integration more challenging.

Consequently, an ‘us versus them’ mentality is created in society. This polarisation can hinder efforts to foster a sense of unity and inclusivity, making it more challenging for non-Irish nationals to feel welcomed and accepted. Asylum seekers and refugees, who are among the most vulnerable groups of non-Irish nationals, can be particularly affected by the rise of right-wing politics. Antiimmigrant sentiments can lead to stigmatisation and increased challenges in accessing asylum processes and support services.

In several European countries, right-wing political parties have gained popularity in recent years, leading to changes in immigration policies and public debates about integration. For example, Hungary introduced a law that made it illegal to provide support for asylum seekers seeking refuge in the country. This is a breach of EU law and international law.

DIRECT PROVISION

Direct Provision is a system in Ireland that provides accommodation and basic needs for asylum seekers while their application for refugee status is being processed. While designed as a temporary solution, this system has faced criticism for its adverse effects on the integration of non-Irish nationals into Irish society

15 CHAPTER 1 | |PHYSICAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

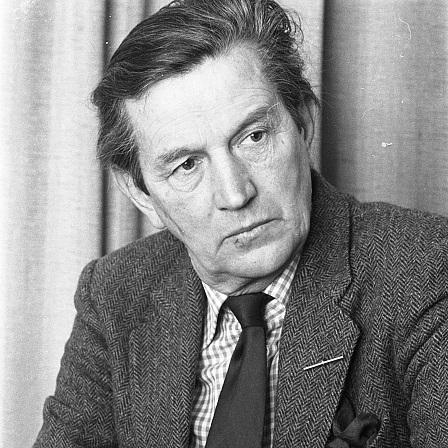

Figure 1.11

Direct Provision centre in Ireland

Asylum seekers in Direct Provision often experience prolonged stays while awaiting the outcome of their application. According to the Irish Refugee Council, the average length of stay in Direct Provision centres in 2020 was 26 months, with some individuals residing in the system for several years. Such lengthy stays create uncertainty and anxiety, hindering the ability to plan for the future and integrate effectively.

The quality of accommodation and services in Direct Provision centres has been a subject of concern. The Ombudsman’s office highlighted issues with overcrowding, lack of privacy, and insufficient cooking facilities, which can negatively impact the physical and mental wellbeing of residents. These conditions make it difficult for non-Irish nationals to maintain their dignity and sense of self-worth while striving to integrate into Irish society.

Asylum seekers in Direct Provision face barriers to accessing education and employment opportunities. While there have been improvements in allowing access to primary and secondary education, the right to work is restricted until asylum seekers have been in the system for at least nine months. This restriction limits their ability to contribute to society and gain valuable skills for integration.

Living in Direct Provision centres can lead to social isolation for residents. Limited opportunities for social interaction with the wider community hinder the development of meaningful relationships and cultural exchange. According to a report by the Economic and Social Research Institute, residents in Direct Provision highlighted feelings of isolation and a lack of belonging in Irish society

In 2021, Ireland announced plans to end the Direct Provision system and replace it with a new model of accommodation for asylum seekers. The government announced plans to ensure the system of Direct Provision was ended by 2024. However, in 2023 a total of 20,140 people resided in Direct Provision centres in Ireland. This highlights the significant number of asylum seekers experiencing this challenging system and the need to ensure that the system is changed.

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING

Basic Knowledge

1. Define a multicultural society and explain how people from diverse cultural backgrounds coexist in such societies.

2. List three challenges associated with multicultural societies, as mentioned in the topic.

3. How does the rise of right-wing politics impact the integration of non-Irish nationals into Irish society?

Developed Knowledge

1. Describe the impact of language barriers on social cohesion and economic integration in multicultural societies.

2. Discuss the role of xenophobia and racism in hindering social inclusion and promoting discrimination in multicultural societies.

3. Outline the challenges faced by non-Irish nationals in the integration process in Ireland, including issues related to documentation, application processes, and direct provision.

Advanced Knowledge

1. Analyse the factors that contribute to the challenges faced by asylum seekers and refugees in integrating into multicultural societies.

2. Investigate the complexities and potential solutions in transforming the Direct Provision system in Ireland to promote effective integration and improve conditions for asylum seekers.

16 THE NATURAL WORLD – OPTION 8

3

TOPIC 1.5: Racial Conflict

RACIAL CONFLICT

Racial conflict in geography refers to the tension, discrimination and violence that arise between different racial or ethnic groups within a specific geographic context. In this topic, we will explore the development of racial conflict in the United States of America.

CASE STUDY: Racial Conflict in the US

The history of racial conflict in the United States is deeply intertwined with the arrival of European settlers, the brutal slave trade, the emancipation of slaves, the abolition of slavery after the Civil War, and the implementation of the Jim Crow laws. This sequence of events has left a lasting impact on the social and cultural fabric of the nation.

The roots of racial conflict can be traced back to the early seventeenth century when European settlers arrived in North America. They encountered indigenous Native American populations, leading to clashes over land and resources. The forced removal and displacement of Native Americans resulted in widespread suffering and dispossession.

Figure 1.12

An African American man drinks from a water fountain marked ‘Colored’ at a streetcar terminal in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma in 1939

The demand for cheap labour in the American colonies led to the trans-Atlantic slave trade. From the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, millions of Africans were forcibly brought to America as slaves. They were subjected to inhumane treatment, exploitation and dehumanisation, perpetuating a system of racial inequality that would shape the nation’s history

The mid-nineteenth century saw growing tensions between the Northern and Southern states over the issue of slavery In 1863 President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared the freedom of all enslaved people in Confederate-held territory While this was a significant step towards ending slavery, racial discrimination and segregation persisted.

The end of the Civil War in 1865 led to the passage of the 13th Amendment, officially abolishing slavery in the United States. However, the process of reconstruction was fraught with challenges, as Southern states implemented Black Codes and other discriminatory practices, limiting the rights and opportunities of newly freed African Americans.

THE JIM CROW LAWS

The Jim Crow laws were a series of state and local laws enacted in the Southern states of the United States between the late nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries. These laws enforced racial segregation and institutionalised white supremacy, effectively separating African Americans from white Americans in all aspects of public life.

17 CHAPTER 1 | |PHYSICAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

1. Segregation of public facilities: Jim Crow laws mandated separate public facilities for African Americans and white Americans. This included segregated schools, public transportation, restrooms, parks and restaurants. For instance, in some states, African Americans were forced to sit at the back of buses or use separate drinking fountains and entrances.

2. Voting restrictions: Jim Crow laws sought to suppress the political power of African Americans. Poll taxes, literacy tests and other discriminatory measures were used to prevent them from exercising their right to vote. These practices effectively disenfranchised many African American citizens.

3. Miscegenation laws: Some states had laws prohibiting interracial marriages, known as miscegenation laws These laws aimed to maintain racial ‘purity’ and further perpetuated racial segregation.

4. Restrictions on employment and housing: African Americans faced limited job opportunities and housing options because of the Jim Crow laws. Discrimination in hiring practices and restrictive covenants in housing contracts were common. This created segregated neighbourhoods and limited economic mobility.

5. Education disparities: Schools for African American children were underfunded and lacked resources compared to white schools. These disparities in education perpetuated racial inequality and hindered social mobility for African American communities.

The Jim Crow laws during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had a devastating impact on African American communities, perpetuating racial discrimination, segregation and social inequities. African Americans faced widespread poverty, limited access to education and

18 THE NATURAL WORLD – OPTION 8

Figure 1.13

Segregated school in a Southern state of the USA

healthcare, and constant threats of violence from white supremacist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan. Additionally, the Jim Crow laws provide a poignant example of the conflict that can occur between political and cultural groups. These laws enforced racial segregation and discrimination, leading to significant social, political and cultural tensions.

THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

The civil rights movement was a transformative social and political movement that took place in the United States during the mid-twentieth century. It aimed to challenge racial segregation, discrimination and systemic racism faced by African Americans, advocating for equal rights and social justice. The movement had a profound impact on American society, leading to significant legal changes and inspiring a broader understanding of the importance of civil rights.

The civil rights movement gained momentum in the 1950s and 1960s as a response to the entrenched racial segregation and discrimination faced by African Americans. Influential leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr, Rosa Parks and Malcolm X led peaceful protests, sit-ins and other non-violent actions to demand equal rights and an end to racial segregation.

The civil rights movement achieved significant milestones that transformed American society. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, outlawed racial segregation in public places and employment discrimination based on race, colour, religion, sex or national origin. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 further protected the voting rights of African Americans, ending discriminatory practices that had suppressed their voting rights.

The civil rights movement brought attention to the systemic racism and social injustices faced by African Americans, sparking a national conversation about racial equality It led to the dismantling of many Jim Crow laws, which had been used to enforce racial segregation in the South.

In summary, the civil rights movement serves as a vivid illustration of the conflict between political structures seeking to maintain the status quo, and cultural groups advocating for justice and equality. This pivotal period in US history had profound geographic and societal consequences, shaping the nation’s future trajectory.

19 CHAPTER 1 | |PHYSICAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

Figure 1.14

Martin Luther King at the scene of his famous ‘I Have a Dream’ speech

BLACK LIVES MATTER MOVEMENT

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement is a response to racial conflict and systemic racism, particularly in relation to racially motivated police brutality in the United States. It gained prominence in 2013 after the acquittal of George Zimmerman, a neighbourhood watch volunteer who fatally shot Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black teenager, in Florida.

Racially motivated police brutality refers to instances where law enforcement officers use excessive force against individuals from racial minority groups, particularly African Americans. These incidents often result in severe injuries or even death, leading to heightened tensions and protests against discriminatory policing practices.

George Zimmerman’s acquittal in the Trayvon Martin case brought the issue of racial profiling and unjust treatment of black individuals to national attention. It highlighted the broader problem of racial bias within the US criminal justice system.

Furthermore, in May 2020, the murder of George Floyd, an unarmed black man, by a white police officer in Minneapolis, further ignited the BLM movement. A viral video showing Floyd’s agonising final moments sparked outrage and mass protests across the US, as people demanded an end to police violence and systemic racism.

The murder of George Floyd led to an unprecedented wave of protests across the US and around the world. Demonstrators took to the streets to demand justice for Floyd and other victims of police brutality, as well as structural reforms to combat racial inequality.

The BLM movement has had a significant impact on public awareness and policy discussions. It has spurred discussions on racial inequality, police accountability, and the need for systemic change. The movement has also influenced some policy reforms in certain states and cities, focusing on issues such as police training, transparency and community engagement.

Despite progress, the struggle for racial justice and police reform continues. The BLM movement seeks to challenge entrenched racism and advocate for lasting change in policies, practices and attitudes to ensure that all citizens are treated with fairness and respect, regardless of their race or ethnicity.

In conclusion, the Black Lives Matter movement is a modern-day example of the conflict between political structures and cultural groups. Its efforts have led to significant political and social changes, sparking geographic discussions about racial disparities and inequalities across the United States and beyond.

20 THE NATURAL WORLD – OPTION 8

Figure 1.15

Black Lives Matter protests in the United States have gained momentum in response to the increased use of violence by police officers against African Americans.

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING

Basic Knowledge

1. What is racial conflict in geography, and how is it defined in the context of the United States?

2. Name two historical events that contributed to the development of racial conflict in the US

3. Explain the significance and impact of the Jim Crow laws on African American communities. Developed Knowledge

1. Describe the key features of the Jim Crow laws and their effects on the daily lives of African Americans.

2. Discuss the goals and achievements of the civil rights movement in the United States.

3. How did the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement gain prominence, and what are its primary objectives?

Advanced Knowledge

1. Analyse the factors that led to the rise of racial tension between European settlers and native American populations in the early seventeenth century.

2. Investigate the ongoing challenges faced by the Black Lives Matter movement and the progress it has made in addressing systemic racism and police brutality.

WRITE LIKE A GEOGRAPHER

1. Examine how conflict can arise between political structures and cultural groups. Success criteria:

Your answer must:

• Clearly define the term ‘racial conflict’ and its relation to the geographic context of the United States.

• Provide a brief overview of the history of racial conflict in the United States, including key events such as emancipation, the abolition of slavery, and the implementation of the Jim Crow laws.

• Mention the significance of the civil rights movement in challenging racial segregation and discrimination faced by African Americans

Your answer should:

• Discuss the key aspects of the Jim Crow laws, including their impact on segregation, voting rights, and education disparities for African Americans.

• Explain the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, its relation to racially motivated police brutality, and its significance in addressing racial bias within the criminal justice system.

Your answer could:

• Analyse the long-term societal impact of the civil rights movement, especially in terms of the dismantling of Jim Crow laws and the broader national conversation about racial equality.

• Evaluate the effectiveness of the BLM movement in changing policy reforms at state and city levels. Your answer should highlight the challenges for long-term change.

21 CHAPTER 1 | |PHYSICAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

3

PAST EXAM PAPER QUESTIONS

HIGHER LEVEL

2021

Explain how conflict can arise between political structures and cultural groups. (80 marks)

2019

Examine the impact of the movement of people on racial patterns (80 marks)

2015

Examine the impact of colonialism and migration on ethnic/racial patterns (80 marks)

22 THE NATURAL WORLD – OPTION 8

CULTURAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

CHAPTER 02

SYLLABUS LINK

8.1 POPULATIONS CAN BE EXAMINED ACCORDING TO PHYSICAL AND CULTURAL INDICATORS. CULTURE AND IDENTITY ARE TIED TO IDEAS OF ETHNICITY, WHICH INCLUDE RACE, LANGUAGE, RELIGION, AND NATIONALITY.

KNOWLEDGE RETRIEVAL

Retrieval Quiz

1. Describe the impact of colonialism on Brazil’s culture, society and racial diversity.

2. Outline the demographic consequences of the trans-Atlantic slave trade on Africa and the Americas.

3. List three challenges associated with multicultural societies mentioned in the topic.

4. How does the rise of right-wing politics impact the integration of non-Irish nationals into Irish society?

5. How did the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement gain prominence, and what are its primary objectives?

23

LEARNING INTENTIONS

1. Outline how language serves as a cultural indicator of identity with reference to the Polish and Hebrew languages.

2. Explain how the media has influenced the development of European languages.

3. Compare how the Irish and Welsh governments have implemented policies to support the survival of minority languages in their respective countries.

4. Discuss how religion serves as a cultural indicator of identity with reference to the development of church–state relations in Ireland.

5. Analyse the causes and impacts of religious conflict in Northern Ireland.

6. Describe expressions of cultural identity in Ireland under the headings of sport, music, food and religion.

KEYWORDS

LanguageCultural identityIndigenous languages Linguistic diversity

Hebrew languageMass media Language evolution English

Globalisation Internet influenceMinority languages Cultural significance

Language decline Irish (Gaeilge) Welsh language revival Religion as cultural indicator

Religious festivals Church–state relations Church’s continuing presenceReligious conflict

Northern Ireland Ulster Plantation Partition of Ireland Segregation

TOPIC 2.1: Language as a Cultural Indicator of Identity

Language, a fundamental aspect of human communication, transcends its basic function to become a powerful indicator of cultural identity Across the world, diverse linguistic patterns have evolved, shaping unique cultural landscapes.

Figure 2.1

World map outlining the geographic location of various language groups

Language profoundly influences the sense of belonging within a community. For indigenous peoples worldwide, language is intertwined with cultural heritage In Australia, the loss of many indigenous languages has led to a disconnection from ancestral roots. According to the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, about 120 indigenous languages are still spoken today, down from an estimated 250 before European colonisation

The global significance of linguistic identity cannot be overestimated. It is recorded that over 7,000 languages are spoken globally. However, nearly 40 per cent of these languages are at risk

24 THE NATURAL WORLD – OPTION 8

Indo-European Albanian and Hellenic (Greek) Germanic Indo-Iranian Romance Slavic Armenian Sino-Tibetan Tibetan and Burmese Chinese Afro-Asiatic Berber and Cushitic Arabic Niger-Congo Austronesian Dravidian Turkish Mongolian Japanese Korean Others

.

of extinction. As globalisation accelerates, linguistic homogenisation (the phenomenon whereby languages mix together as one) threatens this rich cultural diversity

WORLD LANGUAGE GROUPS

Language groups consist of languages that share common ancestral origins, often displaying similarities in grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation. These groups can be further classified into language families, which encompass multiple related languages. For instance, the Indo-European language family includes languages such as English, Spanish, Hindi and Russian, with shared roots dating back thousands of years.

MAJOR LANGUAGE GROUPS AND EXAMPLES

1. Indo-European: This is the largest language family, spoken by billions around the world. It includes English, French, Spanish, German and many more.

2. Sino-Tibetan: Dominant in East Asia, this group includes Chinese, Tibetan and Burmese. Mandarin Chinese alone has over a billion speakers.

3. Afro-Asiatic: Encompassing languages spoken in Africa and the Middle East, it includes Arabic, Hebrew and Amharic.

4. Niger-Congo: Predominant in Sub-Saharan Africa, this group includes Swahili, Yoruba and Zulu. Swahili is spoken by over 100 million people.

African Languages

Tamazight Arabic Tachelhit

Arabic

Pullar Fulfulde

Serere-Sine Wolof Wolof Mandinka Fulfulde

Crioulo

Fulfulde Balanta

Arabic Chaouia Kabyle

Hassaniya Arabic Pulaar Fulfulde Soninke Bambara Fulfulde Soninke

Jula Fulfulde Moore Jula Senoufo Baule Fante Ewe AsanteTwi

Maninka Futa Jalon Susu Mende Themnee Krio Kpelle Bassa Dan

Arabic Jerba

Figure 2.2

Language Families

Afro-Asiatic Nilo-Saharan Khoisan Niger-Congo Creole Austronesian Indo-European

Kabiye Waci-Gbe Ewe

Aja-Gbe Fon-Gbe Yoruba

Hausa Zarma Fulfulde Chadian Arabic Ngambay Daza

Hausa Yoruba Igbo Bulu Beti Pidgin Banda Gbaya Sango

Bube Fang Seki Crioulo

Fang Myene Mbere Kongo Teke Munukutuba

Umbundu Kongo Mbundu

Arabic Jabal-Nafusah Zuara Tswana Kalanga Kgalagadi

Arabic KenuziDongold Nobiin

Tigre Tigrinya Afar

Arabic Somali Afar

Sudanese Arabic Bedawi Dinka Tigrinya Amharic Oromo Maay

Lingala Swahili Luba

Rundi Hima Swahili

Ganda Chiga Nyakore Swahili Gkuyu Luo

Swahili Gogo Sukuma

Nama Herero Kwambi Bemba Nyanja Tonga Shona Ndebele Ndau

Lomwe Nyanja Yao

Somali Garre

Kinyarwanda Hima Swahili

Makhuwa Lorrwe Tsonga Zulu Xhosa Sotho Afrikaans Swati Sotho Comorian Malagasy

Map outlining the variety of different languages officially registered in Africa

25 CHAPTER 2 | CULTURAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

CASE STUDY: The Polish Language as an Indicator of Identity

The Polish language serves as a powerful indicator of identity, bearing witness to Poland’s tumultuous history and its enduring spirit of resilience. This case study delves into how the Polish language evolved as a symbol of national pride and identity, despite centuries of foreign rule and oppression.

Poland

+ 10,000,000 + 1,000,000 + 100,000 + 10,000

Figure 2.3

World map of Polish diaspora

CENTURIES OF FOREIGN OCCUPATION

Poland, situated between a number of neighbouring countries, including Germany, Austria and Russia, endured a turbulent past marked by foreign occupation Under foreign rule, particularly during the partitions of Poland in the eighteenth century, schools were prohibited from teaching the Polish language, and its use in official matters was forbidden. Instead, schools were often forced to teach in languages such as Russian, German or Austrian, limiting the use and promotion of Polish. Although historical data was not accurately recorded during this period, it is clear that there was a decline in the availability of education in the Polish language during this time. As a result, literacy rates among the Polish population suffered, which hampered cultural development

Despite these restrictions, the Polish language remained an essential cultural treasure, preserved in clandestine schools and through oral traditions, reflecting a deep-rooted sense of identity These secret educational institutions played a vital role in passing down the Polish language and culture to younger generations. During this period, oral traditions and folklore, including storytelling, songs, and poetry, became important means of preserving the Polish language and identity These traditions thrived despite official restrictions in the country.

NAZI CRUELTY AND THE POLISH LANGUAGE

During World War II, the Nazis embarked on a brutal campaign to replace the Polish language with German. This oppressive regime involved the closure of Polish schools and severe punishment for Polish people speaking their native language. Statistical data provides insights into the extent of this linguistic suppression.

26 THE NATURAL WORLD – OPTION 8

Historical records indicate that the Nazis closed over 93 per cent of Polish schools in the occupied territories, effectively dismantling the Polish education system. This disrupted access to education through their native language for generations of Polish students. Records also reveal the harsh consequences faced by those found speaking Polish. Punishments included imprisonment, forced labour, and even execution in extreme cases These measures aimed to erase Polish identity and culture The Nazi Party’s attitude to cultural destruction is summarised by a quote by Joseph Goebbels, a high-ranking member of the Nazi Party at the time: ‘The Polish nation is not worthy to be called a cultured nation.’

2.4

During the German occupation of Poland in World War II, Warsaw residents were forced to bury their dead in parks and streets, after mass killings and bombardment.

Furthermore, the cruelty of the Nazi regime led to the deaths of around 6 million Polish citizens, devastating families and communities. World War II also caused significant material losses, as around 85 per cent of Warsaw was destroyed. Following the war, Poland fell under Soviet influence, enduring communist rule until 1989 The Soviet occupation stifled cultural expression and limited political autonomy, indirectly affecting the Polish language. However, despite these hardships, the Polish language prevailed as a symbol of resistance and unity.

RESTORED INDEPENDENCE AND EUROPEAN UNION MEMBERSHIP

Today, Poland’s restored independence and membership in the European Union signify its place on the global stage. As of 2022, Poland stands as the sixth most populous EU member state, with over 38 million citizens. Its EU affiliation, acquired in 2004, underscores its integration into a unified Europe, enhancing economic cooperation and cultural exchange. Additionally, the Polish language, recognised as an official language of the EU, symbolises not only Poland’s identity but also its contributions to the world’s cultural fabric. With a thriving literature and a secure future, the Polish language continues to shine as a beacon of cultural significance, reinforcing the lesson that language is not just a means of communication, but an essential thread in the fabric of a nation’s identity.

27 CHAPTER 2 | CULTURAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

Figure

CONTEMPORARY SIGNIFICANCE

The Polish language continues to play a significant role in Poland’s identity, both nationally and internationally.

• Official language: Polish is the official language of Poland, which reflects the enduring importance of the language.

• Preservation of identity: Despite globalisation and the dominance of English, Polish people continue to prioritise the preservation of their language and culture.

• Global diaspora: The Polish diaspora also maintain the language, connecting with their heritage and contributing to a global Polish identity.

Figure 2.5

Approximately 91 per cent of Polish people support Poland’s membership of the EU.

The Polish language stands as a remarkable indicator of identity, tracing a path through Poland’s tumultuous history. It has survived centuries of foreign dominance, Nazi oppression, and emerged stronger with the restoration of independence and EU membership Today, the Polish language is more than a means of communication; it symbolises the unwavering spirit of a nation that has refused to let go of its linguistic and cultural heritage, and that has reaffirmed its identity on the world stage.

CASE STUDY: The Hebrew Language as a Cultural Indicator

In the late 1800s a movement called Zionism emerged among the Jewish people. It aimed to establish a national homeland in Palestine, the ancestral land of the Jewish people. This aspiration was challenged by the linguistic diversity within the Jewish communities, hindering effective communication and unity.

The diversity of languages spoken among Jewish communities posed a significant challenge to their goal of establishing a singular identity. In response, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, an educator and editor, took upon himself the task of reviving Hebrew as a common language. Hebrew, once confined to ancient texts, became the linchpin for Jewish unification because of its historical and cultural significance.

Having lain dormant for over two hundred years, Hebrew faced vocabulary limitations that rendered it unsuitable for modern discourse. Ben-Yehuda diligently expanded the language by inventing thousands of words, integrating them into daily usage through his newspaper.

28 THE NATURAL WORLD – OPTION 8

He drew inspiration from the roots of existing Hebrew words, cultivating a language that bridged the gap between the past and the present.

As Jewish settlers established themselves in Palestine, learning Hebrew became pivotal in fostering a distinct cultural identity. In predominantly Muslim surroundings, the Hebrew language united the settlers, underscoring their connection to their historical roots and fostering a sense of belonging.

In 1948 the United Nations recognised Israel as a sovereign nation, validating the Jewish people’s long-cherished dream. Israel officially embraced Hebrew, along with Arabic, as its languages, solidifying its cultural significance. A staggering 80.9 per cent of native-born Jews in Palestine had adopted Hebrew as their sole language by this time, reinforced by the works of modern Jewish writers who enriched its expressive potential.

Presently, nearly all 8.8 million Israeli residents converse in Hebrew, although it serves as the primary language for less than half due to diverse waves of Jewish immigration. Beyond Israel’s borders, approximately one million individuals possess Hebrew-speaking skills. Hebrew is acknowledged as a minority language in Poland, for instance.

Hebrew’s revival stands as a remarkable achievement, as it remains a singular instance of a ‘dead’ language being fully resuscitated. It owes its success to the support garnered from the Jewish diaspora spread throughout Europe, along with the robust endorsement of the Israeli government.

Hebrew’s transformation from ancient scriptures to a vibrant spoken language embodies the potent role language plays in shaping cultural identity. The journey of its revival underscores how linguistic unification can transcend time, connecting generations and nurturing a sense of belonging. As Hebrew continues to thrive, it stands as a testament to the enduring power of language in preserving and redefining cultural heritage.

29 CHAPTER 2 | CULTURAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

Iraq Syria Lebanon Israel Jordan Egypt Sudan

Arabia UAE Oman Yemen Eritrea Ethiopia Aramaic Languages Hebrew Arabic Old South Arabian South Semitic

Saudi

Figure 2.6 Hebrew is an important indicator of identity for people living in Israel.

Figure 2.7

Road signs in Israel in Hebrew, Arabic and English

IMPACT OF JEWISH SETTLEMENTS ON PALESTINIAN CULTURAL IDENTITY

The presence of Jewish settlements in Palestine has significantly impacted the cultural identity of the Palestinian population, causing concerns about the erosion and shrinking of their cultural heritage and traditions.

The establishment of Jewish settlements often involves the confiscation of Palestinian land, altering the physical landscape and disrupting historical connections to the territory As of 2023, there are over 130 official Israeli settlements in the West Bank, with an additional 97 outposts This expansion has resulted in the appropriation of thousands of acres of Palestinian land.

According to the United Nations, over 45,000 acres of Palestinian land has been confiscated for settlements since the Oslo Accords in 1993. This process contributes to the displacement of Palestinian communities and the alteration of traditional land use practices.

The expansion of settlements and neighbourhoods by the Israeli people, and the displacement of Palestinian communities, has caused fragmentation of traditional neighbourhoods, and has disrupted social cohesion.

The encroachment of settlements can lead to the appropriation of cultural sites, limiting Palestinian access to places of historical and religious significance.

New prefabricated homes under construction in the West Bank The construction of these homes for Israel settlers on Palestinian land is illegal.

Settlements often receive more resources and more investment in infrastructure. This leads to economic and social disparities between Israeli settlers and Palestinian residents. Israeli settlements receive more public funding per capita compared to Palestinian communities in the West Bank. The Israeli government has allocated significantly larger budgets for settlements, contributing to disparities in infrastructure, education and services. Reports show that settlements have better access to water, electricity and transportation networks. In contrast, Palestinian communities face limited infrastructure development due to restrictions on movement and the allocation of resources.

The domination of Israeli culture and language in settlements can undermine the preservation of Palestinian language, heritage and traditional practices.

30 THE NATURAL WORLD – OPTION 8

LEBANON

SYRIA Golan Heights

West Bank

Tel Aviv Jerusalem ISRAEL PALESTINIAN TERRITORIES

EGYPT

Gaza Strip

Mediterranean Sea

Dead Sea

JORDAN

Figure 2.8

The settlement of Jewish settlers in Palestine has also impacted Palestinian cultural identity.

Figure 2.9

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING

Basic Knowledge

1. What is the relationship between language and cultural identity?

2. Name two major language groups and provide examples of languages from each group.

3. Why is linguistic homogenisation a concern for cultural diversity? Developed Knowledge

1. Describe the role of language in influencing a sense of belonging within a community. Provide one example from the topic.

2. Explain the significance of the Polish language in preserving Polish identity throughout history.

3. Discuss the challenges faced by the Jewish people in establishing a unified cultural identity due to linguistic diversity Advanced Knowledge

1. Analyse the impact of linguistic diversity on the preservation of cultural heritage.

2. Consider the broader implications of language revival for cultural identity and global understanding. How might the successful revival of a ‘dead’ language such as Hebrew inspire other efforts for linguistic and cultural revitalisation?

WRITE LIKE A GEOGRAPHER

1. Examine the importance of language for cultural identity. Success criteria:

Your answer must:

• Define language as a cultural indicator and establish its importance in shaping identity.

• Use evidence from the text, such as key events and statistics, to support the importance of language as a cultural indicator.

• Address the core elements of the question by drawing on examples from the provided text, such as the role of the Polish language and Hebrew in preserving cultural identity.

Your answer should:

• Provide a detailed analysis of how the Polish and Hebrew languages have acted as powerful tools in preserving and shaping cultural identity in the face of adversity.

• Explore the challenges faced by Poland and the Jewish community and how language played a pivotal role in uniting and defining these communities.

• Discuss the broader implications of language as a cultural indicator, linking it to the themes of resilience, resistance and unity highlighted in the text.

Your answer could:

• Make comparisons between the Polish and Hebrew languages, identifying similarities and differences in their historical journeys and roles as cultural indicators

• Examine the potential threats to cultural identity by referencing the impact of Jewish settlements on Palestinian cultural identity, providing a perspective on the intricate relationship between language, land and identity.

31 CHAPTER 2 | CULTURAL INDICATORS OF IDENTITY

3

TOPIC 2.2: The Influence of Media on European Languages

Mass media encompasses various communication platforms such as television, radio, print and the internet. It holds a significant sway over the development and evolution of languages across the European continent. It has played a pivotal role in shaping linguistic trends, altering vocabulary, and even facilitating the spread of certain languages, especially English.

2.10 Simplified map of languages in Europe

Mass media refers to a wide range of communication channels that reach a large audience simultaneously These channels include television, radio, newspapers, magazines and the internet They serve as vehicles for disseminating information, entertainment, and cultural content on a grand scale.

IMPACT OF MASS MEDIA ON ENGLISH SPEAKERS

Mass media profoundly affects people who speak English, particularly due to its widespread use in global media. English is often chosen as the ‘official language’ in multinational media productions, making it accessible to a global audience. As a result, English-speaking individuals are exposed to a broad range of content, from movies and TV shows to news and social media platforms.

32 THE NATURAL WORLD – OPTION 8

Galician Portuguese Icelandic Irish Scottish Gaelic English Faroese Scots NorthernSámi Skolt Sámi InariSámiKildin Sámi LuleSámi PiteSámi UmeSámi NorwegianSouthernSámi Finnish Karelian Karelian Nenets Mansi Khanty Komi-Zyrian Komi-Permyak Tatar Udmurt German Mari Bashkir Tatar Chuvash Erzya Russian MokshaUkrainian Ukrainian Armenian Swedish Estonian South Estonian Latvian Danish Lithuanian Frisian English Russian Dutch Belarusian Welsh Breton Basque German Polish Sorbian Luxembourgish Czech French Slovak Rusyn Romansh Ladin Hungarian Friulian Slovenian Gagauz Italian Greek Aromanian Serbian Romanian Crimean Tatar Bulgarian Turkish Azeri Spanish Catalan Maltese Turkish Greek Armenian Kazakh Kalmykia Laz Kumyk Svan Tat Ossetic Georgian Nogai Abkhaz Mingrelian Kurdish CaspianLanguages A r menian Bosnian Croatian A r m en ian K arachay-Balkar Circassian Macedonian Montenegrin Kabardian Meglenitic

Figure

THE ROLE OF GLOBALISATION IN SPREADING ENGLISH

The process of globalisation has facilitated the spread of English. In the fields of multinational corporations, diplomacy, and international communication, English is commonly deployed as the common language. This global reach amplifies the influence of English media, contributing to its pervasive presence and impact. Approximately 1.5 billion people worldwide speak English, and it is the official or second language in over 70 countries. This linguistic domination encourages multinational corporations to employ English as the lingua franca for business transactions and negotiations, fostering smoother cross-border operations.

Furthermore, the pivotal role of English in international diplomacy is underscored by the fact that it is the primary language of major global organisations such as the United Nations, where it facilitates effective dialogue between nations This linguistic unity enhances collaboration and understanding in addressing global challenges.

THE INFLUENCE OF THE INTERNET