Publicness in Mumbai through Food Cultures

Food, Space and City Publics

School of Environment and Architecture

University of Mumbai

2023

Dissertation Supervisors: Prasad Khanolkar and Milind Mahale

Abstract

To begin with the thesis, my primary question was, does food shape architecture? And if yes, how? These questions became relevant for Mumbai city, as now and then, almost daily we are subjected to spaces that serve food, and we inhabit different spaces of food differently. The research is thus, situated in the context of Mumbai and understanding enterprises that serve food, “the eateries”

It became crucial to understand how food culture is produced and how it shapes the spatial organization and experience of eating. It was not so evident in the eateries that were newer in age as the forces that were driving these were different than the ones that were needed to understand, “food cultures”. Hence, I studied significantly older eateries, where the primary force that was driving it, was the “food”. As I mentioned in the first paragraph, this becomes highly relevant to Mumbai City. Mumbai is a city of migrant settlers, every location in Mumbai changes in its characteristics because of where the ‘public’ are migrating from.To study this, I chose a smaller locality of Mumbai, the Dadar-Matunga scheme. It enabled me to observe closely the specificities that were related to the eateries.

This publicness gets manifested through multiple things like networks, histories, spatial organizations, and the public who come to the eatery. Different cultures allow different type of publicness to happen. In one case it happens through their ethics about mass food production. The resultant space thus becomes a space that caters to a large population, which organically changes according to the increase in demand for food. While the other one is a regimental space associated with working class and nostalgia. These spaces are usually undesigned and do not hold value in terms of their stylistic appearances. But there is an idea of the “public” that emerges out of these interactions with the food itself. There is an exchange that takes place between the space, the food, and the public who come there to eat food. The food culture brings in the logic to formulate the space and the public brings their networks, associations, and friendships. These eateries, thus become important micro-public interventions in the city itself. They are not necessarily designed with the idea of the aesthetics or theme but they bring about a sense of care and friendship among the moving public of the city.

Further, the study will also be an archive for the city to think about eateries or restaurants as public spaces. The process of documentation for the fieldwork included eating at these spaces, spending time, and experiencing the flux. Also informal interviews of the owners or managers and the usual customers of these eateries were taken, and a study of the media and literature archival material about these eateries, to get a historical sense.

1. Food, and the City Public

Introduction, Exploratory Questions and Research Agenda

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Terms to Explore

1.3 Research Agenda

2.What is Food Culture?

Theoretical Framework and Research Methodology

2.1 Theoretical Framework

2.1.1 What constitutes Food Culture?

2.1.2 Public Culture of the City

2.2 Research Methodology

2.2.1 Methodological Approach

2.2.2 Field Selection

2.2.3 Drawing Methodolgy

3. Locating the Food Culture?

History of the Dadar-Matunga Scheme, the area of study

4. City and the eateries

Stories of eating cultures

4.1 Of fast-lives (Rama Nayak Udupi)

4.2 Of residential cafe (Cafe Colony)

4.3 Of working class and nostalgia (Mama Kane Upahar Gruha)

4.4 Of leisure,market and transit (Gomantak Boarding House)

5. How,Why, and Where? Food Cultures and publics

Analysis and Spatial Argument

5.1 Analysis

5.1.1 Fastness and Shifting nature of space

5.1.2 Slowness and Cosmopolitanism

5.1.3 Regimentality, Entrepreneurship and Nostalgia

5.1.4 Leisure and Market economy

5.2 Spatial Argument

6. Interlocuters

Bibliography and Appendix

6.1 Bibliography

6.2 Appendix

1. Food and the City

Introduction, exploratory Questions and Research Agenda

1.1 Introduction

During the recent pandemic of 2020 followed by the lockdown, food production, and food culture saw a shift, there was a change in the relationship between food and people. It might be because of the rise of certain, social media apps, that almost force us to adhere to certain aesthetics, which seeps into our food choices. With this a heavy focus on consumer marketing, because during the lockdown, the target audience for the brands were the classes who were working from home, yet generating a fair amount of revenue, their pastime became surfing for commodities and food. It also resulted in the emergence of a particular kind of restaurant in the city. These ranged from cafes, delis, and theme-based cuisines, particularly East Asian or as it is said, pan-Asian restaurants, patissiers, boulangerie, cloud kitchens, and vegan and healthy food options. Not to disregard any of these, because most of us now as friends started visiting these places with peers, however what it lacked was the specificity in terms of the kind of public culture it gave rise to. It became highly classist and inclined towards a particular social media aesthetic, the food did not become significant to the place and everything became almost sanitized in the way the restaurants were set up. A cafe in Colaba would not be much different from a cafe in Bandra or Dadar. The kind of public coming to the restaurants belonged to a certain economic background and the space of the restaurants limited itself to it being an interior project. Barring a few of them that did try to evoke a certain contemporary culture like the chain, Socials, which gave rise to a certain new age idea of publicness, but then again when people were asked to sit next to each other, it almost became forceful at times, unlike at the Udupi or the Khanawal where the kind of food that was served, made the public sit in a certain way. In Socials, there also wasn’t much connection between what happened inside the eatery or outside the eatery.

On the contrary, the older eateries became the heritage of the city. Heritage in ways not only related to stylistic approaches to the space, like the way the space is made, and the way the furniture is made. But the experience it holds in terms of the solidarities, the friendships, the negotiations, and the relationships that got built in and around the space of the eatery. The heavy layering of different histories that went into the restaurant, the way the type of food shaped the space, and the geographical location decided the pace and the atmosphere of the eatery, the public inside and the public outside always had something going on, be it through networks among the public or be it through commonalities in terms of what happened around the eatery The “Adda” that gave the bengalis their characteristic of promoting sheer laziness in the people, or the rise to the practice of friends getting together for long, informal, and unrigorous conversations, or the adda as an institution that stands beyond need or utility.(Chakraborty,2000). Similarly, these eateries gave characteristics to the public, they produced a culture of publicness in the city, that was not only planned through the urban planning logic but it took place in micro-forms in these eateries.

This made me question, what shaped the Public Culture of food in Mumbai. Throughout history, Mumbai has witnessed events of cultural mixing, civil revolutions, and as a result production of different public cultures. By quoting some experiences of older family members, it is often said that during the 20th century, families as a group did not venture outside their homes to eat. It was often the people in transit or the working class who had to fulfill their food needs outside of their homes.

The new Mumbai, post the economic and social revolution of the late 1800s and the early 1900s, had people who had to travel far away from their homes and outside the purview of their caste, class, and ethnic groups. This quotidian phenomenon resulted in the daily cycle of commuting and eating, further, the influx of migrant laborers and the increasingly changing geography of the city it was not possible to go home for lunch, and hence there needed to be someone to come and provide food to these people. Thus numerous eateries emerged through this trope of the working class that was a way that the city as a whole took care of their eating needs. However, these eateries did not limit themselves to places of just food production and consumption, they became spaces for the “City Public”, to engage in cultural production. Food is a highly condensed social fact and unlike houses, pots, masks or clothing food is a constant need but a perishable good, thus the daily pressure to cook food and the pressure to produce or acquire makes it suitable for everyday social discourse. (Appadurai,1981). Through my fieldwork, I mapped these eateries, through history and through personal observations to understand what sort of public is getting produced in these eateries, what food culture is getting produced, and how is it affecting the space of the eatery.

2.1.1 What constitutes food culture?

To begin with, identifying what food culture is, it will be important to define and identify the constituents of food culture. By definition, Food Culture is a type of culture that gets produced around networks of food. To be able to formulate a discourse, it will be necessary to know about what happens in the case of Mumbai, and what are the factors that lead to the production of certain food cultures.

Geography-

The geography in terms of how the location, in this case, the Dadar and Matunga scheme came into being. What were the factors that led to the formation of this scheme? What made the scheme a space for only specific things to happen?

Eatery and its history-

The history of the eateries’ existence, stories of the owners, and how the space is shaped due to that. What were the reasons for the establishment of the eatery? What were the ethics that were thought of when it came to the food type of that eatery?

Who comes to eat? The public of the City?

Food, here becomes an important agency to bring together different kinds of public. Mumbai being the city of migrants, and the city to find a livelihood, who comes to eat, at what places and why?

Culminating all these ideas, one gets a sense of the spatial nature of the eatery serving a particular kind of food and why it facilitates a certain kind of public. This culture does not fit into linear narratives of a timeline or a period. Instead, it is a layering of multiple stories that have happened across time and across networks, of which traces can be found in that space of the eatery. These traces become important, though they are tangible but they hold stories and narratives of the space that are intangible.

2.2.1 Methodological

Approach

The tracing of the food culture across the city was done through my perspective as a user (public), customer, thinker, and practitioner of space-making. This was done by studying the eateries through parameters of history, stories from the history, and current observations of the space and then conjecturing what idea of public space is getting generated.

I went there first to only eat and talk to people informally and tried spending as much time as I could to observe different timings. To document, I was constantly trying to photograph, though it was not allowed in the space but I took my liberty to be discreet with it. This method could not however find out the exact physicality of the space of the eatery in the historical sense. To follow this limitation, references from other authors, who then became the interlocutors in the study were used to conjecture the way certain activities were performed in the restaurant’s history. The advantage of this was, that the study did not limit itself to a bounded analysis of the space, it did not only remain in the physicality of the space but extended itself to form a discourse in itself. The study was not conducted through any specific lenses of difference as it did not lie in that realm only, it was more of a general study regarding the public, where I as the researcher might be taking a position of looking inside out but only to understand the way the food culture gets manifested spatially making it a public space.

I was interested in observing the history, family, networks, food types, eating cultures, politics, veg/non-veg, and class. With this, the cues from the space like, movement, conversations, furniture placement, and relationships.

2.2.2 Field Selection

Mumbai historically has been a fairly dense city, with blurred identities, that are not seen evidently but can be traced through micro-narratives of the city. Mumbai was a strong port city during the colonial period, it also was a base for the textile mills and the Bollywood industries to prosper during the early 1900s. It also became the financial capital for the country resulting in the migration of people from different states of the country and neighbouring countries. Similarly, when people migrated from different places in the city, to get a sense of home they established themselves in communities of their kind, that also permeated in the kind of food they ate and to serve food to their kind of people they established eateries. Thus, the homing instinct of the people made evident the kind of eateries that are found in Mumbai. These eateries were of different scales but to decide on a scale for studying, the important aspect was to choose places that were not highly romanticized or were extremely famous but stayed at a level of the neighbourhood or a locality. Hence, the mode in which the eateries were selected was through the idea of the ethnic community and the kind of food that a particular community ate and served.

Analytical Categories

Irani Cafe (Cafe Colony) estb-1930

Udupi (Rama Nayak Boarding) estb-1920

Analytical Cases

Khanawal (Mama Kane Upahar Gruha) estb-1910

Sea-food restaurant (Gomantak Lunch home) estb- 1952

1 history of the eatery type

2 sense of the actual space

History of how the Iranis migrated to Bombay, what were their networks how did the first food types start in which cafes history of a few other Irani eateries, through articles

The moving of South Indian Brahmins from southern towns to Bombay for a livelihood, Rama Krishna mission, Matunga being concentrated by this population other food institutions at that time the idea of the fast-paced tiffin items vs meals (vegetarian)

History of women cooperatives khanawal, Annapurna mill laborers and textile mills

Portuguese preparation and malvani preparation eateries other sea-food khanawals

history of how family-run khanawals came into being migration from the villages in Goa and Maharashtra along the Konkan coast

Key elements in the actual space, that has connections with the stories, networks and histories and also that seem significant to the actual space

3 history of the space,owner

History of the space in terms of what was the space before and changes that took place in the space because of the history. Also, the history of the owners who set up the restaurant, taken over by different people

4 food culture

What was the food that the eateries started serving? Specificities in terms of preparation that connect to their stories? How and why did the food transform?

Who comes to the eatery? Who are the usuals? Where do they come from? What happened in history that allowed the specific public to inhabit a specific eatery? Connections with the locality

5 publicness

3. Locating the Food Culture

History of the Dadar-Matunga Scheme, the area of study

The question of locating the food culture and the location or the geography became apparent, during the fieldwork when I was visiting different eateries across the city During this time, it became evident to me that an eatery far down south of the city functioned differently than an eatery that was slightly up north. These terms sound very relative, hence to emphasize the locality, I compared the eateries located in and around Churchgate station in the south and then compared them with the eateries in the Dadar- Matunga scheme, which is slightly up north. This made it evident that the urban planning or the forming of the city and parallel historical events that take place in that region influence the way people eat and inhabit, an eatery. To understand a specific location and how the eateries performed at that specific location, it was important for me to narrow down to one geographical location in the city that had significant similarities in its formation. Hence, I chose to study the eateries at the Dadar-Matunga Scheme.

Thus, to understand this location’s influence on the eateries, it will be important to historicize them, from their planning to the inhabitation and events that followed. At the beginning of the early twentieth century, the document of the city that was put out by the Bombay Improvement Trust, involved the suburbanization project of the city which became important to think about practices of land and space in the then colonized India. It got manifested in ways that became evident in suggesting the geography of the city from the far south to moving slightly up north in the areas of Dadar- Matunga-Sion, where the hills disappeared, low-lying grounds are being raised and the sea is being excavated, and reclaimed and the the barren lands being converted to gridded building plots. The suburbanization project suggests the vision of planning.

With this, there was also a question of who would live in the new suburbs. There was a survey undertaken and sent to the usual stakeholders, the Port Trust, Municipal Corporation, Mill owner’s association and so forth. After debates between, the rich class the working class and the middle class, the decision was taken that the middle class would be appropriate to be housed in the suburbs and also could afford the cost of living.In turn, multiple kinds of middle-class communities settled in these areas. The south Indians, in Matunga, the Maharashtrians or the Marathi-speaking households in Dadar and Hindu colony, and the iris or the Parsis in the Parsi colony. Urban ethnic identity was not a result of an erosion of difference, but, rather because of the specific economic and political imperatives that led to the emergence of the specific communities. (Rao, 2013).

As a result, various other infrastructures were built around these suburban neighbourhoods, that were specific in terms of the community and their nature affected the kind of public that also came into these areas.

4. City and the eateries

Stories of eating cultures

4.1 Of fast-lives

(Rama Nayak Udupi)

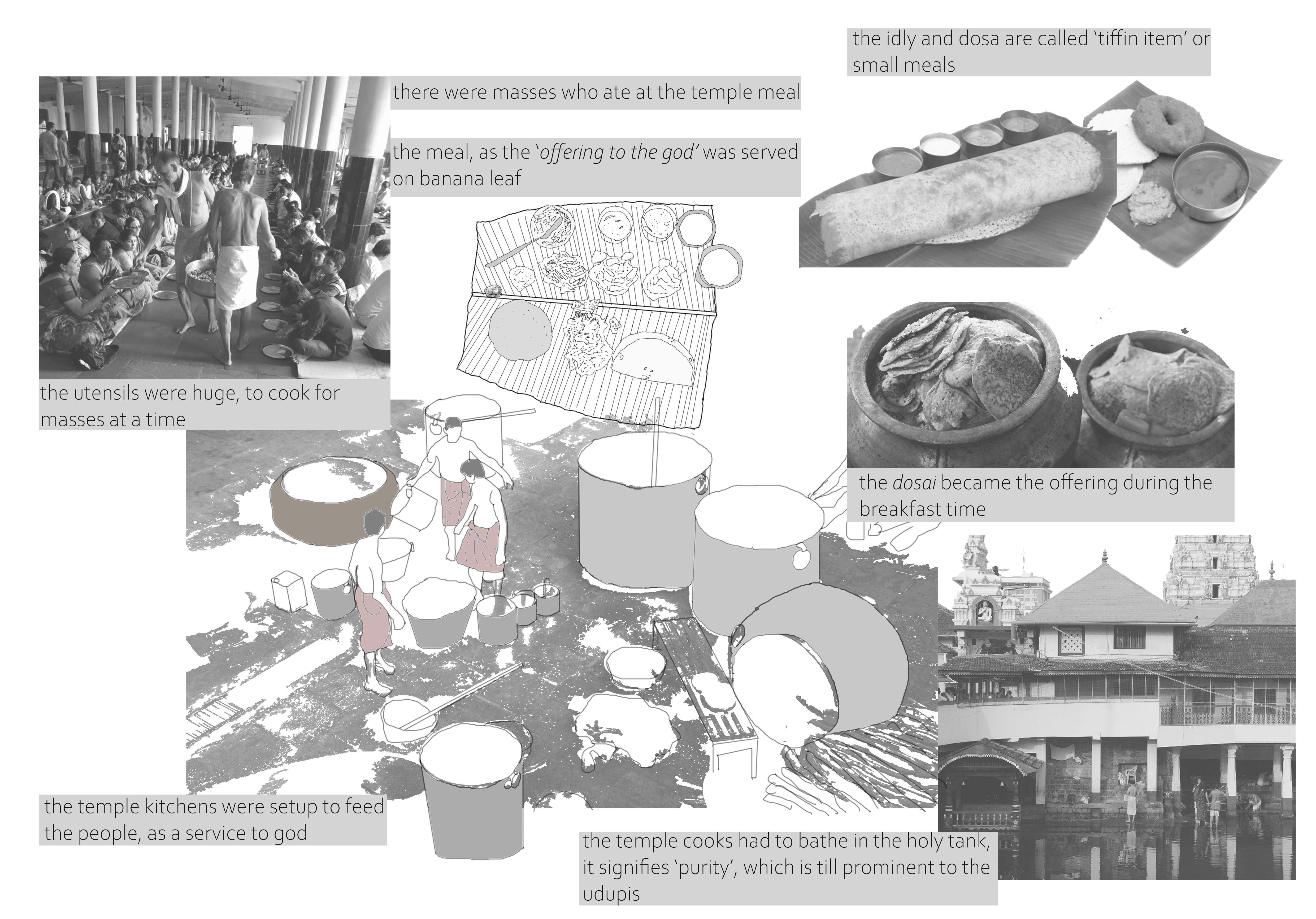

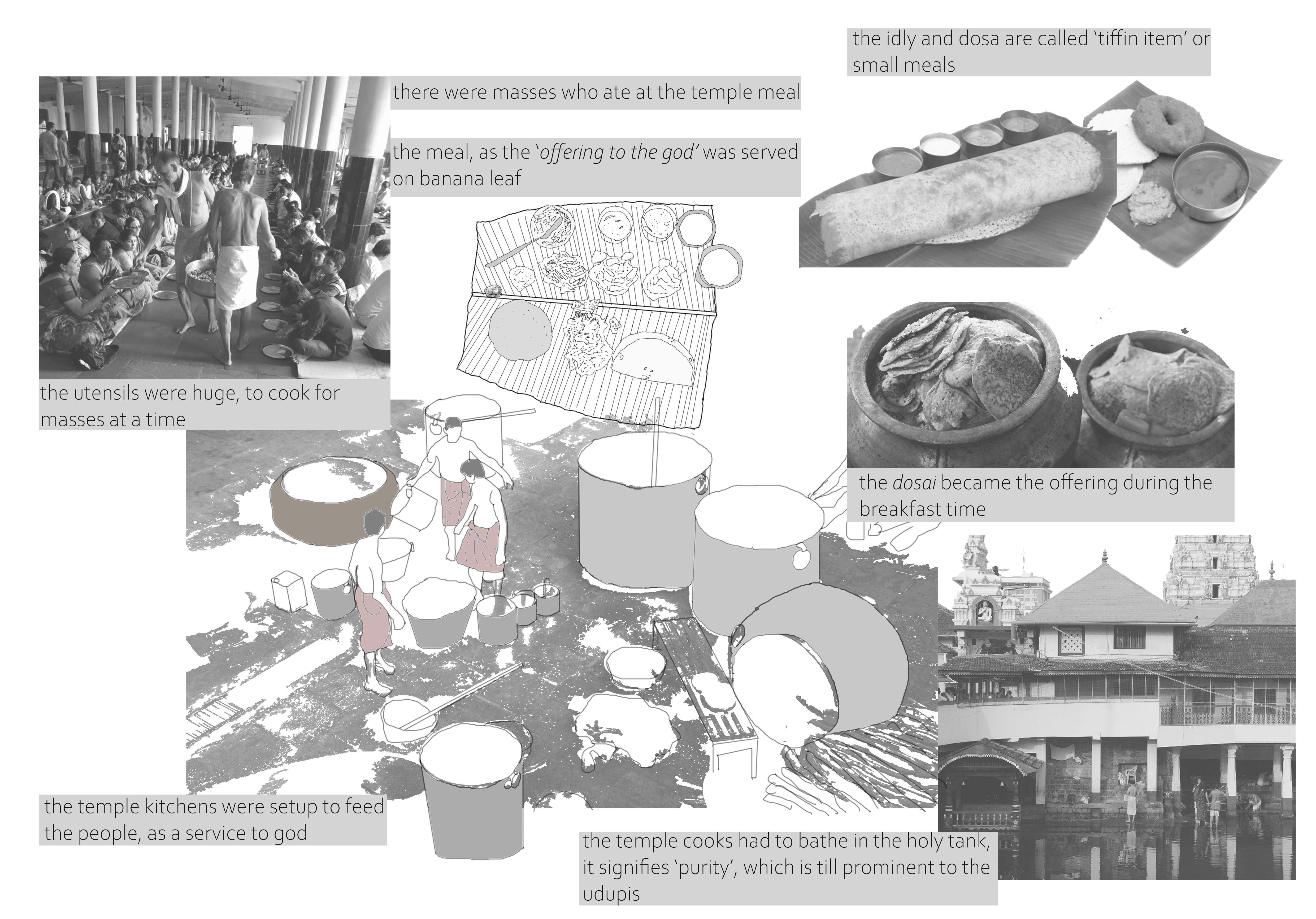

Geographically Udupi is associated with the southern peninsular states of India. Though it is a city in Karnataka, its association comes with the heavy establishment of Udupi eateries across the country and even the world. The mainstream ideas of the Udupi hold relevant, it includes the eateries that typically serve the food that is prepared mostly in southern India. In the case of Mumbai, since the early 1900s, there are hundreds of Udupi restaurants that are established in this city. They cater to the fast public, the public who want to eat rapidly and not spend much time on their food. These Udupis, migrated from their homes to Mumbai, to seek better livelihood. Most southern towns were temple towns, and the people felt that Mumbai would let them make more money simply. It is said that one of the earliest Udupi establishments in Mumbai, was the Rama Nayak Sri Krishna Boarding, at Matunga.

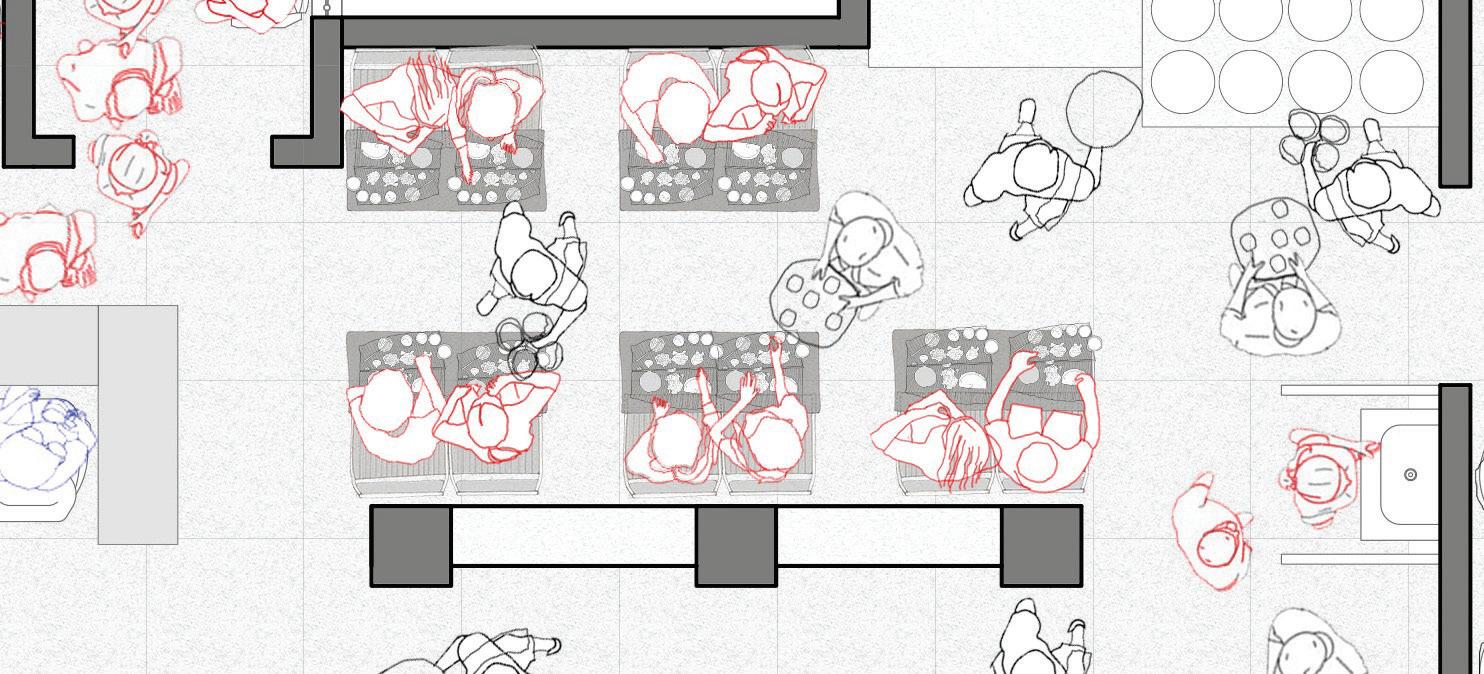

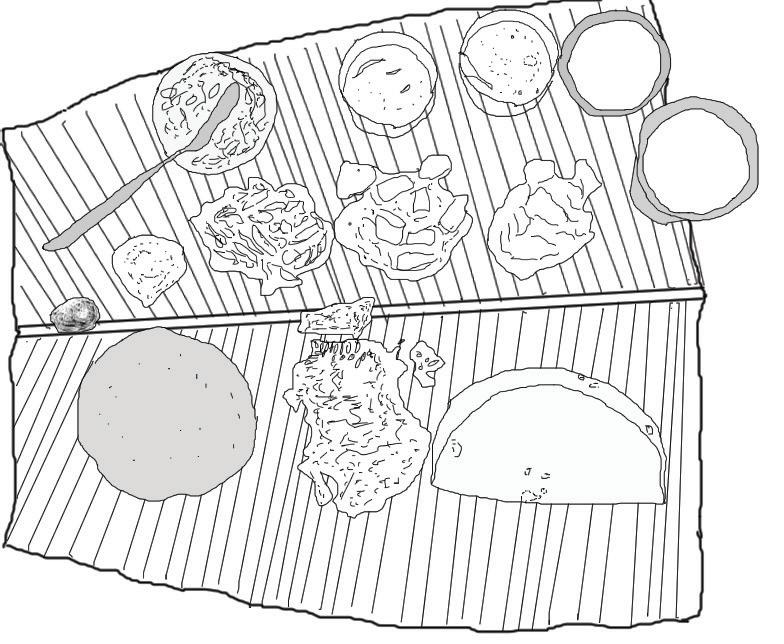

Rama Nayak, is at King’s Circle and is right behind the Central Railway station. It is located on the first floor of a building, which has a wholesale market under it. It has metal tables with formica tops, and tables aligned in straight lines, and everyone sits next to each other in lines and eats. They serve the meal on banana leaf mostly but these days they also have a thali option. The food comes as a set of curries and other condiments with a heap of rice, followed by a dessert dish. The waiters are all dressed in lungis and a shirt, and they are always waiting. They keep coming by your table and keep asking if they need more, the food is unlimited, except the dessert which is charged on quantity. The food is served in straight lines, and one after the other people come and eat. Because they have such a high density of people coming for lunch, they cannot allow people to do anything else but eat. They ask everyone to keep their bags and belongings on a rack before sitting at a desired table, they are very strict with their rules, and everyone needs to remove their shoes before entering the eatery. They allow tables based on token numbers, if families come to eat then they give the numbers that are close to each other, but if you come alone, you can be seated beside anybody. Thus, they call themselves cosmopolitan, as the owners claim, that anybody can be seated next to anyone as the only task there is to eat. To cater to such a fast pace and high density, the kitchen needs to be extremely efficient, which is so. The kitchen has highly efficient divisions based on what they are preparing, and each cook is assigned to a specific kind of food, like one person, assigned to prepare batches of place rice, then someone else to make sambar and other curries, someone for puris and other bread, someone for the sweet dishes and an equal number of people to take over in shifts. The food-making process is divided into batches according to timeslots, during the day. They only serve during the day, their prepping happens in the evening and the following day, they just cook. The cooks are also dressed in lungis. Once you are done with lunch, you are immediately asked to step out while the next person comes and sits at your table.

Waiting Area

The founder, Rama Nayak, came to Bombay in the 1930s, when he was 11, he was a pauper of a high-caste Brahmin from Udupi. He came to Bombay and got a job as a kitchen worker at the Ram Krishna Mission Center in Mumbai. While he gathered experience from his work, he also gathered enough capital within a decade to open his eatery in the same neighborhood. During that time, Matunga was occupied primarily by poor migrants from South India. Thus, the menu he created was to cater to the needs of these people, which was two meals a day. As the stories say, the name Udupi is associated with a “strict tradition of ritual purity, cleanliness, neutral dining space for patrons from all classes and castes”. Unlike most Udupi restaurants, which serve food that is mostly rice-based “tiffin dishes”, like dosa, uttapam, idli, and vada, this eatery serves slightly elaborate meals.

During the 1960s and 70s, the migration of people from the south reached its peak and thus had to cater to the needs of everybody migrating to the city. Thus, they started to take over the spaces that were earlier occupied by the older Irani cafes and turn them into Udupi eateries. The Udupis faced tension with the then-ruling parties of Maharashtra, as the parties claimed that the south Indians were stealing jobs from the “people of the soil”, however, the space of the Udupi was so ubiquitous to the city that it did not face any difficulty in confronting the political upheaval. Like the Irani cafes, the Udupis were also cheaper, thus they allowed a range of public to come and eat at the restaurant. Mainly because it was devoid of meat, people of different religions came and sat together, the high-caste Brahmins and the lower castes sat next to each other at the Udupi. By the 1980s and 1990s, the Shetty’s started taking over the Udupi business, however, the Rama Nayak brand was highly established, thus nothing came in the way. With the Lunch home, the Udupi also ran a boarding home, which is not functional as of now, but there used to be some space for people to retire after a journey or after work. The Matunga central station being at such close proximity, again made it a place for the people in transit to come there and eat. Many people spent their time, outside the restaurant after eating, discussing about politics and sports, some even made small bets on cricket. Some people came to visit the wholesale market underneath and then decided to have lunch at the Udupis.

4.2 Of residential cafe (Cafe Colony)

The Story of the Iranis in Mumbai begins somewhat at the beginning of the 20th century. Iran at that time was under the rule of the Qajar dynasty, and it was the final decadent age of their reign. The people wanted to flee the deprivation and repression of this dynasty. Mumbai, which was shifting economically, and there were changing patterns of social structure, could accommodate taking in refugees, thus for Iranis Mumbai became their refuge. Thus as a result, a large number of Zoroastrian Iranis, from the eastern provinces of Yazd(Tehran) and Kerman, migrated to Mumbai.

One of the many Iranian restaurants is Cafe Colony, which is still in the running at Dadar. It is located right at the beginning of the Hindu Colony opposite the Parsi Dairy farm. It is on the ground floor of the apartment building in the Hindu Colony. It serves predominantly breakfast and bakery food, but it also has a counter with all the home essentials. Most prefer ordering the Kheema Pav and the Bun Maska and Chai. The portions serve one person and the food comes in small ceramic or plastic plates and the sweets are served in disposable tin containers. It is like the other Irani cafes with, typical bent-wood furniture with marble tops, checkered table cloth, mirrors on the walls on the columns, glass jars with Khari biscuits, etc. The space is mostly not very congested except during weekends. The habitue includes students or groups of colleagues at formal or informal meetings. Groups of old men and women from the nearby colonies come there to pass their time and discuss gossip. The eatery was started in the early 20th century and its age permeates the space. There are exposed metal columns and girders that are not concealed. The mirrors on the wall and columns make the space appear bigger than it is. Bakery items are mostly sold at a small display nook showcase at the entry. Soda bottles are stored in the industrial metal refrigerator. The old wooden cabinet hosts the metal tin boxes for storage. The small square tables are all arranged at a 45-degree angle to the lines of the space, covered in a tablecloth topped by a glass plank to save the wood from being damaged. Some posters suggest how to maintain order in the restaurant.

The Irani migrants, now in apparent search of income, were trying to find jobs. They started working at small tea stalls and provided tea to the officials working at government offices. The Iranis caught the attention of the Colonisers, since both of them were new to the country and its culture, making them friendly with each other As time passed this friendship allowed them to acquire corner plots of buildings at much cheaper prices, one because the Hindu superstition disapproved of the corner plots and second because they were able to make friends with the British. The Iranis then started establishing Cafes at these plots, Most of these cafes were cooperatives between different Irani families, which means more than one family was involved in the cafe process. The Iranis were outsiders and purely interested in business initially because of neutral ground, everyone was welcome there, and no social or political differences played a part.

The Irani cafes, were a social necessity at that time, in the heat of the revolution of the pre-independent India and the ever-changing city of Mumbai. They created a platform for individuals to eat together in a space that was not marked by any boundaries, of class, caste, or ethnicity. These cafes changed the rules of commensality. Further, in time, the Cafes became spaces for creative discussions, conversations, contemplation, or just as a space of transit. Journalist, Meher Mirza, in one of her essays says, “The Irani cafes had the idea of the Modern Day Starbucks”. The irony was, even when the cafes had boards like “Do not Discuss”, “No Lingering Around”, and” Do not talk to the Cashier and the Waiters”, the cafe became a space for all sorts of discussions, among different people.

Rashid Kohinoor, owner of the Brittania restaurant at Ballard Estate says, when the Irani, would set up a restaurant, the first thing he would buy was chairs and tables. Those chairs and tables would be imported from Europe, from places like Belgium, Czechoslovakia, or Poland. The chairs were called Back-bent chairs, Bent-wood chairs, or Welcome Chairs. When Britannia was first opened in 1923, they leased the space for 99 years and first opened it for the British officials, to please them, which was with most of the Irani cafes. Initially, they used to serve food that was liked by the British. The British set up the Military headquarters in the restaurant, during World War II and only returned the restaurant to its owners in 1947. Post-Independence there was a law that was formed, that everyone should be allowed to it in a restaurant That is when they opened it up to the public and started giving out food of the Zorastrian make.

During the early, 1900s Mumbai had more than 150 Irani restaurants, Journalist Busybee says, “That is more number of restaurants than in Tehran, Irani”. The Stories of the Irani migration were a thrill. Some say they came to Karachi by Bus and then came to India. Another story says that people came from Arestan to Mumbai on the back of the donkeys. Not only the stories of their migration but the spaces that the Iranis occupied as restaurants were thrilling. The Brebourne restaurant was a horse stable before, and not just that post that people used to bet on Horse races in the restaurants, this is not only in the case of Brabourne but also most other Iranian cafes. In the late 90s, there was a raid on some Irani cafes, accusing them of carrying out business as “bucket shops”, under the cover of legitimate trade, and extensive gambling in New York cotton futures.

The most requested food by the clientele is the Brun or the Bun, and Chai or with Kheema. The technique of making this “Guttlipao”, came to the Iranis from the European technique of Baking, however, the yeast “Khamir” that was used in the process was from Iran. The bread was made using the sourdough process. Zand Merwan Abadan, the owner of the Yazdani bakery, keeps mentioning how his grandmother, Jerbanoo, started kneading the dough at 3 a.m., and she kept kneading the dough throughout in batches. Their Brun used to be delivered from Colaba Military camp to Chembur in bullock carts, the unsold bread was made into toast and eaten with papeta ma gosht (mutton curry).

Cafe Colony was owned by Multiple owners, in the early days, it was owned by Mr. Mohammed, who ran the cafe with his family, his wife, and two children. At the time that he ran the cafe, it was easier for the cafe to be run, the labour and the raw material were easily available, though the cafe was small and it offered fewer things. Then Mohammaed left the cafe and then it was taken over by Agha, says he took over the cafe with slight difficulties but the Iranian boys who waited at the table were loyal and did many odd jobs. There was personalized service if one was staying nearby. They used to personally deliver eggs bread and other items. People were friendly and the crowd was motley. They even had a jukebox and a weighing machine. Many residents from the Parsi colony too would come to the cafe and enjoy the music and sit around till late. But soon all this disappeared as the suburb began to grow and old structures gave way to new ones. The footpath in front of Cafe Colony widened as traffic increased on the Tilak Bridge. Cafe Colony was no longer the same where one could sit quietly and enjoy a cup of chai without the blaring of horns. But with it, the cafe too began to expand and many more things were added to the cafe besides bakery products and tea accompaniments. Nearer to Cafe Colony (two shops away) Agha’s family purchased another corner shop called Bakery and Candy Store, which did a brisk business for a short period but ran into a considerable loss and was sold off. But Cafe Colony soldiered on. The Irani boys keep changing and one has to keep a hawk eye on them.

It lies on the intermediate street junction, between the residential schemes of Hindu and Parsi Colony. The “usuals”, or the daily customers, include the demographically older population from the residential colonies. They have mostly seen the cafe since it started and they frequent the space, for their club meetings, discussions about the cooperative housing colony unions and general meetings, forming unions among the different cooperatives in the colonies for certain city issues, etc. The older fandom related to Dadar and cricket also grows here, the “oldies” make bets around crickets, etc. The cafe is fairly close to the Dadar TT. The people who work in places in Dadar or are switching from one railway line to another line, often find places to seek respite between their moments of transit, such people also become the usuals of the cafe but they are in a rotation according to their work timings, etc. They mostly visit the cafes for a cup of chai, and to find some stranger friends who also are in transit. There are also chances that a certain someone comes on a random day and makes a business deal or a young couple who has sneaked out from their homes in the colonies comes here and spends time only to avoid the gazes of their families, but the entire neighbourhood knows about their endeavours.

5. How,Why, and Where? Food Cultures and publics

Analysis and Spatial Argument

5.1. Each case speaks of a certain spatial relationship that gets developed with the food culture, the space and the publicness of that eatery. These spatial relationships are built around ethnographies of the eateries, the spatial organisations and emerging food culture.

5.1.1 Fastness and shifting nature of space

The driving force leading to the shifting nature of the space is the fastness in the food culture and the way the space is thus organised. The ethics by which the eatery runs are logics that lead upto a space that has to cater to the mass production of food. This affects the way that the public culture really gets shaped in the eatery. The space is subjected to everyday changes, ranging from quick addition of furniture if the eating crowd increases. This creates awkwardities in the space of the eatery.

It does not happen in a manner that is designed in terms of ergonomics or utility It appears that it is purely based on the idea of ‘providing food’ to the masses, that emerges from the culture of the Udupis.

10/12 mins per person to finish

token system - sitting next to strangers

ethics: feeding the poor temple: mass food production space setup only as a space to eat

as space demands, more furniture is added

Rama Nayak Udupi

5.1.2 Slowness and Cosmopoltianism

Cafe Colony

The ‘cosmopolitianism’, comes from the idea of inhabiting the space of the cafe to “pass ones time”, to engage in discussions. The table set-up allows the people to inhabit the eatery in a way that brings about a slowness in the space. One is allowed to spend as much time as they want in the space, thus fascilitating discussions, conversations and meetings.

The food which is served is are not elaborate meals, instead small plates. Which means that the primary idea of the food culture, is not only with this idea of providing food, but allowing the space to afford different forms of ‘get-togethers’.

open kitchen - food is made only once a day

became a space to pass time- thus the occasional satta bets

cosmopoltian

migrated from Iran space setup first for the British, serving continental food

one can spend as much time as they want, in the cafe tea stall outside government offices

small plates- kheema pav, bun maska, omlette pav, irani chai (limited)