European Forum for Urban Security

Safe

and inclusive public spaces: European cities share their experience

Published by the European Forum for Urban Security (Efus), this docu ment is the result of the PACTESUR (Protect Allied Cities against TEr rorism in Securing Urban aReas) project, which ran from January 2019 to December 2022. It was written by Marta Pellón Brussosa (Programme Manager), Tatiana Morales (Programme Manager) and Nathalie Bourgeois (Copy Editor), and produced under the supervision of Elizabeth Johnston (Executive Director) and Carla Napolano (Deputy Executive Director), with contributions from the project partners, the 11 associated cities and the Expert Advisory Committee.

Use and reproduction are royalty free if the purpose is non-commercial and the source is acknowledged.

Translation: Nathalie Bourgeois

Proofreading: David Wile Layout: Marie Aumont

Printing: ONLINEPRINTERS GmBH, Fürth, Germany

Printed in November 2022 ISBN: 978-2-913181-90-2 EAN: 9782913181908 Legal deposit: November 2022

European Forum for Urban Security 10, rue des Montiboeufs 75020 Paris - France Tel: + 33 (0)1 40 64 49 00 contact@efus.eu - www.efus.eu

This publication was funded by the European Union’s Internal Security Fund — Police. The content of this publication represents the views of the author only and is his/her sole responsibility. The European Commission does not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains.

uropean Forum for Urban Security

E

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Safe and inclusive public spaces: European cities share their experience

Acknowledgements

The PACTESUR project was completed successfully thanks to the mo bilisation and commitment of the partner cities, associated cities and experts who contributed to its various components and to the prepara tion of this publication. We would like to thank them for their commit ment throughout the project and for generously sharing their knowledge, experience and expertise. They have thus contributed to achieving our common goals.

We would also like to thank all those who contributed to the many face-to-face and online events, meetings, police academy and general discussions organised as part of the project.

Finally, we would like to thank the European Commission, and in particular the Directorate-General Migration and Home Affairs for its financial support through its Internal Security Fund (ISF) — Police Programme, without which this project and publication would not have been possible.

The PACTESUR project was carried out with the participation of the project partners, the 11 associated cities and the Expert Advisory Committee. We would like to thank the following for their commitment and enthusiasm:

Project coordinators

Florence Cipolla, Jean-François Ona and Sebastian Viano (Nice, France).

Project partners

Benedicte Biron and Bernard Frederick (Liège, Belgium), Elena Ciarlo and Edoardo Mattiello (ANCI Piemonte, Italy), Gianfranco Todesco, Elena Ghibaudo and Federico Dellanoce (Turin, Italy).

Associated cities

Paul Seddon (Leeds, United Kingdom), Claudia Beck (Munich, Germany), Francisco Javier Espinosa and José Ramon Carrasco (Madrid, Spain), Martyn Holt (London, United Kingdom), José Antonio Monfort Pons and Fernando Gaona de Sande (Xàbia, Spain), Raimonds Nitišs and Staņislavs Šeiko (Riga, Latvia), Ana Veronica Neves (Lisbon, Portugal), David Robertson (Edinburgh, Scotland), Dominic Seth (Essen, Germany), Leszek Walczak (Gdańsk, Poland), Thanos Tatsis (✝︎) (Athens, Greece).

Expert Advisory Committee

Isabella Abrate, Mariusz Czepczynski, Susanne Diemer, Karine Emsellem, Lina Kolesnikova, Michaël Nicolaï, Gian Guido Nobili, Petia Tzvetanova, Eric Valerio, Christian Vallar, Yves van de Vloet, Nicolas Vanderbiest, as well as a representative from the Centre for the Protec tion of National Infrastructure (CPNI), who has requested anonymity for security reasons.

Other Contributors

A special thanks to Laetitia Wolff, design impact consultant and in structor, who led the partnership-based course between the Sustaina ble Design School of Nice (now called Besign School) and the PACTESUR project. We would like to thank the students who partici pated in the In/pact and Project Citiz projects, Grant Linscott, academic director, and Maurille Larivière, director.

Student designers: Mathieu Andries, Holly L. Bartley, Jules Baudrand, Ibrahim Benouna, Owen Cartau, Maxime Chef, Julian Coiffard, Juliette Dunand, Romain Desrez, Enzo Jamois, Marine Jean, Lola Mangot, Tarushee Mehra, Sacha Nouviale, Pauline Poirot, Clément Pheulpin, Arjun Rao, Fanny Ricciardi, Noémie Rocheteau, Manon Roulan, Matthew Slack, Stefani Takac, Tristan Terrusse, Nicolas Thomas, Agatha Verlay, Baptise Viot, Emma Weber, Eva Zortich.

4 5

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Table of contents

Foreword ........................................................................p. 8

Part 1 - Public spaces at the heart of the city ................ 11

The complex challenge of protecting public spaces .......................... 13

The protection of public spaces, a priority for the European Union .. 13

Preventing and protecting public spaces against terrorism 14

The key role of local and regional authorities ................................... 14

The PACTESUR project: a global and integrated approach to public space protection ................................................................ 16

Part 2 - A multidisciplinary, cross-sector approach to the protection of public spaces .............. 21

Community involvement .................................................................. 26

Security by Design: how to render public spaces both safe and open to all ................................................................................. 31

Urban planning and design: inclusive and safer public spaces ......... 36

The importance of art ....................................................................... 43

Part 3 - The use of technologies for protecting public spaces: efficient but not sufficient .................. 47

Part 4 - Planning in advance.................................................. 61 1. Correctly assessing the situation and needs on the ground .......... 62 2. Building the capacities of local and regional stakeholders to minimise the impact of a crisis .................................................... 66 3. Exchanging practices, knowledge and ideas with peers 75 4. Engaging local businesses............................................................ 78

Part 5 - Communicating efficiently with citizens in case of a crisis .................................... 81

Roles and responsibilities in crisis communication .......................... 82

Taking into account what can or does go wrong ...... 87

Conclusion ..................................................................... 91

Recommendations ........................................................................... 92 Annexes.......................................................................... 95

Annex 1: Twenty-five techniques of situational prevention .............. 95

Annex 2: Standardisation in crime prevention can be effective and fun .................................................................... 96

Annex 3: Preventing vehicle attacks: the experience of the UK’s Centre for the Protection of National Infrastructure .... 104

Annex 4: The example of the ALARM project 108

6 7

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

The management and protection of urban public spaces remains one of the top priorities of local and regional authorities, and a key mandate from the electorate, given their central role in the attractiveness of cities and in fostering the social inclusion of all groups of the popula tion, as well as cities’ offer of culture, leisure and trade opportunities. Unsurprisingly, this has long been a key area of work for the European Forum for Urban Security (Efus), as a network dedicated to urban security gathering some 250 cities of all sizes from 16 European countries.

The waves of terrorist attacks against European cities since the mid2010s have sent shockwaves in European local authorities, which found themselves confronted with the complex challenge of securing their urban public spaces without turning them into “bunkers”. What can cities do to render their public spaces more safe, inclusive and open to all? How to collaborate more efficiently with national authori ties, in particular on counter-terrorism, but also local police forces and all the other relevant local stakeholders? How to take into account new technological developments? How to better involve citizens and civil society?

One of Efus’ members, the City of Nice (France), was the target in 2016 of a particularly deadly terrorist attack on its famous public space the Promenade des Anglais on Bastille Day, a particularly symbolic day for the French. In the following years, the city took a series of initiatives to better prevent such attacks and protect its public spaces, some of which were supported by the European Commission and Efus. In 2019, Nice took the lead of a wide-ranging, EU-funded project titled PACTESUR (Protect Allied Cities against TErrorism in Securing Urban aReas), which aimed to empower cities and local security actors, mainly in the face of terrorist threats, but also against other risks inherent to public spaces. Efus was one of the project’s partners, along with the City of Liège (Belgium), the City of Turin (Italy), and the National Asso ciation of Italian Municipalities (ANCI) Piemonte (Italy).

Over the course of four years, the project organised a wide range of ac tivities, including, but not exclusively, the deployment of pilot security equipment in the project’s partner cities, police academies for various European local police forces, and European Weeks of Security aimed to give a voice to European local stakeholders, police representatives, experts and civil society in the conversation about the security of public spaces.

This publication, presented during the PACTESUR project’s final conference (Brussels, 23-24 November 2022), presents the main insights Efus has drawn from this large project. To be clear, this publication is not meant to be a comprehensive description of all the work carried out by the project, but rather takeaways that we hope can be useful for European local and regional authorities.

We’ve looked at the main challenges faced by local authorities in pro tecting their public spaces; how this issue is approached by EU institu tions; why it matters to involve a wide range of stakeholders but also, directly, citizens; what technology can bring and the main pitfalls to avoid; how to correctly assess public spaces’ vulnerabilities and prepare for all eventualities; and how to communicate in case of a crisis.

We have strived to include as many practical cases as possible, drawn from the PACTESUR project, but also from other EU-funded projects that tackled the issue of the protection of public spaces and in which Efus took part.

We hope this publication will be of interest to you, and that you will join us in keeping this conversation alive by sharing your views and experience through our website and our regular on- and offline confer ences, workshops and other types of meetings and platforms. There is no single or simple answer, but it is clear that directly exchanging between cities on such an important issue can only benefit us all, local authorities and citizens alike.

Elizabeth Johnston Executive Director

8 9

Foreword >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Part 1

Public spaces at the heart of the city

10 11

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Public spaces have changed throughout history. The traditional role of the central square as a gathering place for trade, political and religious expression has evolved into a multitude of other uses and new interac tions. The ways in which citizens access, engage and relate to public spaces have changed, and urban public spaces have become vital areas of urban life: places for communication, gatherings, political demon strations, artistic and cultural performances and all sorts of entertain ment. They represent places where people come together, interact and encounter differences .

The political discourse about public spaces has changed over time as politicians now generally consider them as “public goods” and recog nise the leading role played by local authorities in managing them. Local and regional governments are committed to investing in public spaces as a means to strengthen social cohesion, improve the quality of life, and enhance the image and attractivity of cities. Indeed, numerous studies have shown that well maintained, healthy and safe public spaces improve security and people’s feelings of insecurity.

What is a public space?

As defined by UN-Habitat, “public spaces are all places publicly owned or of public use, accessible and enjoyable by all for free and without a profit motive”.2 They are a key element of individual and social well-being, the places of a community’s collective life, ex pressions of the common natural and cultural richness in all its diversity and a foundation of cities’, and hence citizens’ identity, as expressed by the European Landscape Convention.3

Public spaces can be defined as any open place that is accessible to all without direct cost, such as streets, roads, public squares, parks, shopping centres and beaches, as well as closed places accessible to citizens, such as government and official buildings.

1- Barker, A. (2017). Mediated Conviviality and the Urban Social Order: Reframing the Regulation of Urban Public Space, British Journal of Criminology, 57(4), 848-866.

2- UN-Habitat (2015). Global Public Space Toolkit: From Global Principles to Local Policies and Practice.

3- The first international treaty devoted exclusively to all dimensions of the landscape, the Council of Europe Landscape Convention promotes the protection, management and planning of the landscapes and organises international co-operation on landscape issues.

1.1. The complex challenge of protecting public spaces

Because they are highly frequented and by nature open, public spaces can be the target of a number of threats, such as terrorism, the presence of large crowds and panic movements, or other types of malicious ex tremist attacks. Ensuring that they remain safe, inclusive and open to all is a complex challenge.

Being the level of governance closest to citizens, local and regional au thorities are best placed to understand their concerns in relation to safe and open public spaces and implement appropriate measures to reduce feelings of insecurity. Public spaces require a security policy that is based on cooperation between the different organisations, the private sector and institutions concerned (local authorities, police, emergency services, urban planners and user representatives), in other words, genuine co-production of security that guarantees that public spaces remain both safe and accessible to all.4

of public spaces should be based on a holistic and horizontal approach, connecting EU and relevant national and local strategies, as well as public-

Council of the European Union (2021). Council Conclusions on the Protection of Public Spaces of 7 July 2021

4- Efus (2017). Manifesto: Security, Democracy and Cities – Co-producing Urban Security Policies.

12 13

1.2 The protection of public spaces, a priority for the EU

“The protection

private partnerships”

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Preventing and protecting public spaces against terrorism

As stated in the new EU Security Union Strategy, adopted in June 2020, responsibility for combating crime and safeguarding security primarily lies with Member States. This publication is not intended to be an ex haustive account of the international and national efforts in the field of counter-terrorism. Rather, we will present and discuss the main insights and learnings we have garnered in this domain through PACTESUR and other EU-funded projects that we have led or in which we have been a partner, such as PRoTECT, Secu4All and IcARUS 5

Although European cities have been experiencing acts of terrorism for decades, it can be argued that the modern-day face of terrorism emerged in the wake of the 9/11 attack in New York in 2001.6 Together with the attacks in Madrid (2004, 193 killed) and London (2005, 56 killed), these events have marked a “before and after”. While in the past, terrorist attacks in Europe used to be mainly perpetrated by sepa ratist and political extremist movements acting independently from one another, the phenomenon is now more transnational in nature, which highlights the importance of a shared European response.

As a consequence, the role of local and regional authorities in safe guarding their residents and public spaces from such attacks has become more prominent, along with the traditional role of national governments and police. Indeed, we at Efus have noted over the past two decades the increasing mobilisation of our member local and regional authorities to directly act to safeguard urban public spaces. Efus members are particularly keen to explore the role and responsibil ities of local and regional authorities when faced with terrorist threats.7

spaces, affirming that they, “alongside national governments and inter national organisations and agencies, have a clear responsibility to protect their citizens against terrorist attacks and threats to a democratic way of life.”8 In the wake of the terrorist attacks in France and Belgium in January 2015,9 the EU (re)emphasised the need to enhance public space protection and community resilience. It developed several initia tives, guidelines and tools to support the sharing of knowledge to better understand and anticipate threats in public spaces. These initia tives are based on a holistic and horizontal approach, connecting EU and relevant national and local strategies, as well as public-private partnerships.10

In 2017, the European Commission adopted an action plan to support EU Member States in the protection of public spaces through funding, the exchange of promising practices and lessons learnt, enhancing co operation and facilitating networks. Thanks in part to Efus’ lobbying work to convey to European institutions the need to tackle urban security questions through a multi-stakeholder, local approach involv ing all relevant parties, a Partnership on the Security in Public Spaces of the Urban Agenda for the EU was established in 2019. Led jointly by Efus and the cities of Madrid (Spain) and Nice (France) and gathering 10 European cities, the Partnership sought to “provide concrete European responses to real needs identified at the local level, encourage the exchange and dissemination of good and innovative practices and allow better targeting of interventions as far as legislation or funding instru ments are concerned.” It produced a six-point action plan on issues such as evaluating artificial intelligence or developing security by design guidance (to name a couple), which is now being implemented.11

The key role of local and regional authorities

Since the early 2000s, the European Union has increasingly acknowl edged the key role of local and regional authorities in protecting public

5- Respectively, Public Resilience using Technology to Counter Terrorism (PRoTECT), Training local authorities to provide citizens with a safe urban environment by reducing the risks in public spaces (Secu4All), and Innovative Approaches to Security (IcARUS).

6- European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS) (2017). Trends in terrorism.

7- Efus, Cities Against Terrorism (2007). Secucities: Training local representatives in facing terrorism

The Commission also developed different guidance materials and compiled available guidance. As a result of an extensive consultation process, good practices were identified to improve the protection of public places against terrorist attacks.12

8- Council of Europe. The Congress of Local and Regional Authorities. Resolution 159 (2003) on tackling terrorism the role and responsibilities of local authorities.

9- Attack against Charlie Hebdo magazine followed by an attack on a kosher supermarket in Paris, as well as an attack on police in Belgium.

10- Namely, the 2017 EU action plan to improve the protection of public spaces; European Commission staff working document on good practices to support the protection of public spaces 2019; the EU Security Union Strategy 2020-25; the EU counter-terrorism agenda.

11-Urban Agenda (2020). EU Partnership on Security in Public Spaces (2020), Action Plan.

12- Communication from the Commission of 20 March 2019 on good practices to support the protection of public spaces.

14 15

1.3 The PACTESUR project: a global and integrated approach to public space protection

Initiated in the wake of the 2015 terror attacks in Europe, and in par ticular the 14 July 2016 attack against the Promenade des Anglais in Nice, the PACTESUR project follows a series of initiatives by the City of Nice, with the support of the European Commission and Efus, in the field of the prevention of and protection against terrorist threats affect ing public spaces. As a member of Efus, this municipality promoted the Declaration of Nice on the role of cities in preventing violent extremism and terrorism, which was co-written by the Euromed network of European and Mediterranean cities and Efus and adopted by both networks alongside 60 mayors from 18 countries.13

While there has recently been a slight decrease in terrorist attacks in the European Union (EU), the latest wave of attacks in France (Conflans Ste Honorine and Nice, October 2020), Germany (Dresden, October 2020) and Austria (Vienna, November 2020) show that the terrorist threat remains high in Europe.14 Public spaces continue to be targeted and criminals have adapted to heightened security measures by modi fying their modus operandi and using means that are more difficult to detect because they are part of everyday life, such as using a common vehicle (van or lorry) to ram into a place, or knives rather than guns. The evolution of this threat, which has become more diffuse and there fore more difficult to anticipate, remains a major challenge for EU Member States.

The PACTESUR project (January 2019–December 2022) aimed to empower cities and local actors in the field of public space security, mainly in the face of terrorist threats, but also against other risks inherent to public spaces. Through a bottom-up approach, PACTESUR gathered local decision makers, security forces, urban security experts, urban planners, front-line practitioners, designers and other profes sionals in order to shape new European local policies to secure public spaces against different types of threats.

Based on four pillars

13- It was published at the end of the Conference of Mayors of the Euro-Mediterranean region organised in September 2017 by the City of Nice and Euromed with the support of Efus, the University of Toulouse Jean Jaurès and the University of Nice Sophia Antipolis.

14- In 2021 there were 15 failed, foiled or completed terrorist attacks in the European Union, compared with 57 in the previous year. For more information: Europol (2022), European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

IN-DEPTH REFLECTION

An in-depth reflection on standards, legal frames and local governance.

SPECIALISED TRAINING

The development of specialised training for local security practitioners.

AWARENESS-RAISING

Raising awareness among citizens and politicians of their role in prevention and as security actors.

IDENTIFICATION

Identifying the most suitable local investments for securing open public spaces by sharing field experience.

16 17

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

A multi-stakeholder and interdisciplinary approach to public spaces

PARTNER CITIES AND REGIONS

Led by the City of Nice, the PACTESUR consortium included the City of Liège (Belgium), the City of Turin (Italy), the National Association of Italian Municipali ties (ANCI) Piemonte (Italy), the European Forum for Urban Security (Efus) and Métropole Nice Côte d’Azur.

THE EXPERT ADVISORY COMMITTEE

A group of 14 specialists from various disciplines, including architects, cultural geographers, security and cross-border cooperation experts.

A WORKING GROUP OF 11 CITIES

To exchange knowledge and promising practices relevant to security in urban public spaces.

Europe’s two latest crises – the Covid pandemic and the war in Ukraine – have (re)shifted citizens’ concerns. European citizens identify the economic situation as their top concern at EU level, followed by the environment and climate change and immigration. Health is still the main issue at the national level, slightly ahead of the economic situa tion of the country.

A PARTNERSHIP-BASED COURSE

A partnership-based course between the Sustainable Design School of Nice (now called Besign School) and the PACTESUR project focused its research on the need to apply human-centred design approaches to security.

Understanding threats and perceptions

Security, notably terrorism, was one of the main matters of concern for European citizens as per the December 2017 Eurobarometer of the European Commission. The October 2020 Eurobarometer shows, however, that it is now less of a concern, ranking in ninth place, with only 7% of respondents mentioning it as a top priority compared to 44% three years earlier.15

As stated in the new EU strategy for the Security Union, adopted in June 2020, the Covid-19 crisis “reshaped our notion of safety and security threats” and “highlighted the need to guarantee security both in the physical and digital environments.”16 The pandemic also changed the way we think about and use public spaces. During the pandemic, cities and their users favoured open-air events, pavements were widened to ensure social distancing, and temporary terraces were set up, some times too close to the road. These changes, some of which have remained, have created new situations that cities need to tackle in order to ensure they do not create new vulnerabilities in public spaces.

In order to understand the security challenges in public spaces, any other type of incident that has an impact on these spaces and that is likely to mobilise various security actors must be taken into account. The PACTESUR project has naturally evolved to not only include ter rorist attacks, crowd management and panic movements, but also climatic risks, such as fires or floods. Indeed, events such as wide spread floods in northern Europe in 2021 and wildfires that swept through huge swathes of Europe in the summer of 2022 (including, for the first time ever, London) show how exposed European cities are now to the consequences of climate change. How do they prepare for such disasters and increase the resilience of the public?

Another factor at play now (at the time of writing) is the energy crisis resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has led a number of European cities to dim down public lighting, which in turn can have an effect on urban security at night, and on citizens’ feelings of security, in particular women and girls.

18 19

15- Eurobarometer 2020 of the European Commission – European citizenship.

16- Communication from the Commission of 24 July 2020 on the EU Security Union Strategy.

Consistent with the EU’s priorities

In line with the strategic priorities of the European Union, particularly the Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs (DG HOME), on the protection and management of public spaces, Efus contributed to designing prevention schemes through the PRoTECT project, and to training local authorities through the Secu4All project. Efus also voiced the concerns of local and regional authorities on this issue through the Partnership on the Security in Public Spaces of the Urban Agenda for the EU, and through the URBAN intergroup at the European Parlia ment, of which it is an official partner.

Efus’ positioning

Ensuring that urban public spaces remain safe, inclusive and open to all is a complex challenge for local authorities. For 35 years, Efus has been working to support local and regional authorities in the planning, design and management of public spaces.

In its Security, Democracy and Cities Manifesto, Efus notes that “numerous studies and experiments have shown that the design and management of public spaces have an impact on security and feelings of insecurity”. It recommends considering the various ways public spaces are used based on objective and subjective data; involving the public, including women and minorities, in co-producing security policies; and maintaining a healthy balance between security and the respect of fundamental rights.

Efus’ experience as well as the insights garnered through PACTESUR all point out that for public spaces to remain vibrant and desirable, citizens need to be and feel safe, and to be able to express themselves regardless of racial or ethnic origin, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity or socioec onomic status.

A multidisciplinary, cross-sector approach to the protection of public spaces

20 21

Part 2

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

“First, adopt an open, transdisciplinary, cross-sector approach to the understanding of the problem, not topdown, not just tech, not expert only. Think of a public space as a canvas that is never completely white or neutral. Start with understanding the context and take into account all of it: physical site specs, recent history, background stories, trauma, cultural identity and iconic markers that make it a memorable space.”

(EAC), a group of 14 specialists from various disciplines including ar chitects, cultural geographers, security and cross-border cooperation experts. It also included a partnership-based course between the Sus tainable Design School of Nice (now called Besign School) and the PACTESUR project, which focused its research on the need to apply human-centred design approaches to security.

For 35 years, Efus has been advocating the co-production of security policies involving a wide range of local stakeholders from the public and private sector as well as citizen participation.

Public spaces require that cities and local governments work in partner ship with different stakeholders and organisations, which should include urban planners, first responders, mobility services, local businesses, academia and civil society. Indeed, the security of public spaces is not only the prerogative of the police, nor just a matter of using more technol ogy or exclusively reserved to specialists. Rather, it is the responsibility of a variety of actors representing different disciplines and backgrounds.

The need for a multi-stakeholder and interdisciplinary approach to urban public spaces is highlighted by the very nature of the PACTESUR project, which involved not only partner cities and regions, but also a working group of associated cities18 and an Expert Advisory Committee

17- Laetitia Wolff is a design impact consultant and instructor. She led the partnership-based course between the Sustainable Design School of Nice (now called Besign School) and the PACTESUR project, introducing an experimental action-research and a creative, human-centred design approach to security. See also Chapter 2, Security by Design: how to render public spaces both safe and open to all

18- The PACTESUR project included a working group of 11 associated cities (Athens, Edinburgh, Essen, Gdańsk, Leeds, Lisbon, London, Madrid, Munich, Riga and Xàbia) that had specific issues and knowledge on the protection of public spaces.

Apart from discussing conventional or protective measures such as policing, technology, bollards or barriers, the PACTESUR project explored what could be termed as soft measures aimed at encouraging citizens to appropriate such spaces through art, the design itself of these spaces, or the involvement of local businesses and civil society organisations. The aim is to ensure that these spaces are inhabited, lively and attractive, which makes them reassuring, as opposed to deserted public spaces that citizens avoid because they seem aban doned, or on the contrary overly secured spaces where barriers and technology can seem daunting and deter attendance. This is an area where local authorities have plenty of margin to intervene by mobilis ing and coordinating a wide array of local actors from the public and private sector.

Ensuring a minimum threshold of security that enables other civic values

“Rather than asking how ‘to build (ever) more secure and safer public spaces’, we should perhaps be exploring ways to ensure a minimum threshold of security that enables other civic values, social pursuits and public goods to flourish; where regulation is parsimonious and non-intrusive in ways that, wherever possible, foster self-regulation by citizens.”

Adam Crawford, Professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice, University of Leeds

22 23

Laetitia Wolff, Design Impact Consultant and Instructor, Associate Partner of PACTESUR17

Designing and managing safe public spaces is one of the four areas of work of the four-year, Efus-led IcARUS project, which seeks to build on 30 years of urban security policies and practices to help local security actors better anticipate and respond to security challenges.

The University of Leeds conducted a research study that assessed the trends, tensions and fault-lines that have characterised shifts over time in the design and regulation of safe public spaces across Europe and beyond19. It points out four tendencies:

1. Tendency to alter the built and physical environment so as to “design out” criminogenic opportunities; often infused with logics of “preven tive exclusion”, and overt surveillance as deterrence.

2. The intervention logics have drawn attention away from the situated and contextualised features of local places – with less attention to “what works”, “where” and “for whom”. And simultaneously with little regard to which groups of people benefit from particular interventions or design features in a particular place/situation at a specific time.

3. Technological solutions outweigh human solutions in regard to ad dressing security concerns. There has been little attention to the inter section between social and technological processes.

4. Over-securitisation of public spaces: in the quest for security, the im plementation of solutions may foster perceptions of insecurities by alerting citizens to risks, heightening sensibilities and scattering the world with visible reminders of threat.

In practice: a multi-stakeholder, comprehensive strategy to protect public spaces in Gdańsk (Poland)

In practice: a multi-stakeholder, comprehensive strategy to protect public spaces in Gdańsk (Poland)

19- Efus, IcARUS (2021). The Changing Face of Urban Security Research: A Review of Accumulated Learning, University of Leeds.

Following the assassination of Mayor Pawel Adamowicz during a public event in 2019, the City of Gdańsk (Poland), one of PACTESUR’s 11 associated cities, developed a strategy aimed at increasing the capacity to respond to future security threats in public spaces.

Following the assassination of Mayor Pawel Adamowicz during a public event in 2019, the City of Gdańsk (Poland), one of PACTESUR’s 11 associated cities, developed a strategy aimed at increasing the capacity to respond to future security threats in public spaces.

The strategy included the rebuilding of the Municipal Crisis Manage ment Centre, the improvement of the communication and management system, the development of a CCTV network as well as other technical and architectural elements contributing to safer public spaces.

The strategy included the rebuilding of the Municipal Crisis Management Centre, the improvement of the communication and management system, the development of a CCTV network as well as other technical and architectural elements contrib uting to safer public spaces.

A number of municipal and national organisations were involved in the project, including the Department for Security and Crisis Management, the municipal police, the national police, the Internal Security Agency, the Municipal Security Agency, the fire brigade, Gdańsk Real Estate, the Gdańsk Road and Greenery Authority, private security companies, anti-terrorism specialists and volunteer groups. The PACTESUR project and the experience shared by the other partner cities were a great source of inspiration for its new strategy. This project will serve as the foundation for the whole safety manage ment system of the city for the coming years.

A number of municipal and national organisations were involved in the project, including the Department for Security and Crisis Management, the municipal police, the national police, the Internal Security Agency, the Municipal Security Agency, the fire brigade, Gdańsk Real Estate, the Gdańsk Road and Greenery Authority, private security companies, anti-ter rorism specialists and volunteer groups. The PACTESUR project and the experience shared by the other partner cities were a great source of inspiration for its new strategy.

This project will serve as the foundation for the whole safety management system of the city for the coming years.

24 25

2.1 Community involvement

The PACTESUR project, and also other European projects we as Efus are (or have been) involved in, as well our permanent work with our member cities on the issue of the security of public spaces, all point out to a recurring theme: the need to involve and associate citizens in the development and management of safe public spaces. Indeed, experi ence shows that when citizens are involved in the life of their neigh bourhood, including security, they feel a sense of belonging and attach more value to their own city and neighbourhood, including local public spaces, and this in turn tends to reduce disorder and crime. The question is: how? What means, or schemes, work best to encourage citizen participation?

The general consensus among Efus member cities and partners is that the first step is to identify community needs, existing resources and avail able support (for example civil society organisations and volunteer networks). Most, if not all, local authorities already collaborate with civil society organisations on a range of local public issues. These can provide a good starting point for engaging local communities in order to evaluate feelings of (in)security in a given public space, or before implementing any new preventive measure or scheme, or during and in the aftermath of an incident. The analysis should also include how dif ferent groups of population use a given public space.

A second step consists of directly engaging with individual members or representative groups of the local community, such as local residents who are well respected by the local community, faith leaders, leaders of vol unteer associations, etc. Some of these actors have the ability to engage with and influence multiple spaces, including domestic, professional, social and cultural.20

Yet another practice quite commonly used in cities is to organise ex ploratory walks whereby members of the public representing different groups of population (women, or senior citizens for example) walk through specific public spaces, generally at night, and note down all the elements that contribute to feeling insecure, such as poor or lack of street lighting, or threatening graffiti. These reports give local authori ties and urban planning decision-makers precious direct information on how citizens experience any given public spaces.

20- See also In practice: the Strong Cities Network’s detailed toolkit.

In practice: Crime Prevention Councils

In practice: a multi-stakeholder, com prehensive strategy to protect public spaces in Gdańsk (Poland)

Another avenue to engage citizens is through the establish ment of Local Security or Crime Prevention Councils (LCPC), a governance structure that has been used, notably in France, since the mid-1980s as part of national public policies on crime prevention in order to bring together a large array of stakeholders involved in local urban security.

Following the assassination of Mayor Pawel Adamowicz during a public event in 2019, the City of Gdańsk (Poland), one of PACTESUR’s 11 associated cities, developed a strategy aimed at increasing the capacity to respond to future security threats in public spaces.

LCPCs aim to promote multisectoral and interdisciplinary col laboration and ensure that all voices are heard, not only those of security stakeholders but also those of citizens. As such, the LCCP in Piraeus (Greece) brings together various municipal departments, criminology experts, first-line practitioners and NGOs. It seeks to foster a climate of security and trust and to acquire a better picture of citizens’ daily lives in order to identify their needs and challenges.

The strategy included the rebuilding of the Municipal Crisis Manage ment Centre, the improvement of the communication and management system, the development of a CCTV network as well as other technical and architectural elements contributing to safer public spaces.

A number of municipal and national organisations were involved in the project, including the Department for Security and Crisis Management, the municipal police, the national police, the Internal Security Agency, the Municipal Security Agency, the fire brigade, Gdańsk Real Estate, the Gdańsk Road and Greenery Authority, private security companies, anti-terrorism specialists and volunteer groups. The PACTESUR project and the experience shared by the other partner cities were a great source of inspiration for its new strategy.

This objective is also shared by the City of Montreuil (France), where the Local Council for Security and Crime Prevention (CLSPD according to the French acronym) aims to encourage the participation of residents. However, this remains a chal lenge because it means identifying and operationalising effi cient communication channels with citizens as well as methods and tools to facilitate their involvement in the CLSPD’s work.

This project will serve as the foundation for the whole safety manage ment system of the city for the coming years.

More information on the BeSecure-FeelSecure project here.

26 27

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

In practice: Involving citizens in Turin (Italy)

Cities can also conduct time-limited projects that involve citizens, for example to rejuvenate a particular neighbour hood. This was done in Turin (Italy) through the ToNite project (September 2019–August 2022), which sought to dispel feelings of insecurity among residents of two neigh bourhoods situated near the Dora River and more generally improve the quality of life, especially at night. The project relied heavily on citizen participation to design a range of local projects, initiatives and local services that improved quality of life. It also undertook an ethnographic and social research aimed to gain deeper understanding of behaviours, attitudes and values regarding how the neighbourhood is ex perienced and lived, with a particular focus on the areas of interest (including green areas and public spaces), and the differences in the perception of security and liveability during the day and at night. Exploratory walks organised by residents were part of the methodology used for the research.

> More information on the ToNite project here.

In practice: crime prevention grassroots movements

Citizen participation in the protection of public spaces can also be directly led by citizens themselves, and there are many examples in Europe of grassroots initiatives. A well-known example is the UK-based charity Neighbourhood Watch, which presents itself as “the largest crime prevention volun tary movement in England and Wales with upwards of 2.3 million members.” They offer local communities advice and guidance on a wide range of crimes, such as antisocial behav iour, burglary, street harassment, domestic abuse, and cyber crime, to name a few.

Another example can be found in Setúbal (Portugal), where the municipality has enrolled senior citizens to “patrol” the city, first one of the main streets and later in a public park located in a neighbourhood marred by acts of vandalism, such as graffiti or damage done to trees and urban furniture. The experience is doubly beneficial: on the one hand, it en courages seniors to go out, be active and feel they contribute to society, and on the other it prevents incivilities.

In Bologna (Italy), the Civic Assistant scheme is composed of volunteers who “patrol” around schools, public gardens and parks. Their task is to improve the citizens’ safety and offer an attentive, reassuring presence. They cooperate with the City Council and Law Enforcement, in close relation with the Mu nicipal Districts and the Municipal Police territorial units. This strategy is now reproduced in many other Italian cities, such as Brescia, Forli, Genova, Legnano and Parma, Forli, etc.

> More information on Neighbourhood Watch here

> More information on the Setúbal scheme here.

> More information on the Bologna scheme here.

28 29

In practice: the role of citizens in emergency planning

Recent climate disasters, such as the summer 2021 floods in Belgium and the 2020 Storm Alex in the south of France, showed the importance of involving citizens as early as possible in the prevention and response to such crises. The ALARM project (2017-2021), in which Efus was a partner, devoted much of its work to the role of citizens in emergency planning. The project thus organised a seminar on the Communal Reserves for Civil Protection (Réserves Commu nales de Sécurité Civile) created by several French towns and cities, including Nice, which led PACTESUR21.

These are groups of volunteers who can support professional responders, such as nurses, radio technicians, electricians, plumbers and carpenters who can, for example, set up a shelter, help clear up debris, or cordon off damaged buildings. Volunteers played a big part in the relief effort during the floods in Belgium and actually saved lives. However, this type of intervention must be well organised. Volunteers should be trained and their role should be clearly defined as part of the emergency response. It should be noted that they are also potential future recruits for the emergency services.

As such, direct citizen initiatives should be complementary to policies and schemes implemented by the local/regional authority (mayor or other), rather than supersede them. This requires that the local author ity monitor such initiatives and ideally is in contact with their promoters.

Furthermore, some types of citizen schemes or initiatives call for proper training, notably those that touch on civil protection such as the above-mentioned Communal Reserves for Civil Protection. More broadly, citizens or local businesses who volunteer in activities of sur veillance, control, and assistance to the public in case of an accident, an attack or a disaster should be known to public authorities, and duly informed and trained.

2.2 Security by Design: how to render public spaces both safe and open to all

Some points of attention

This said, involving citizens in public space protection can be complex. Not all grassroots initiatives are necessarily legitimate and should be supported by the local authority (an obvious example is that of vigilan tes). It is important to always keep a healthy balance between the public authority that has received a mandate from the electorate and initiatives pushed by groups of citizens who do not necessarily repre sent the population as a whole.

21- See Annex 3 for a more detailed description of the ALARM project.

Numerous studies have shown that the planning, design and manage ment of public spaces have an impact on security and on people’s feelings of insecurity. This is commonly referred to as Security by Design (SbD), whereby security features are addressed from the very beginning of the conception and design of a public space, taking into account its inherent openness and integration in the urban landscape. This approach can help balance efforts to increase urban resilience whilst promoting the open and inclusive character of public spaces.22 A different iteration of this approach is Crime Prevention through Urban Design and Planning (CP-UDP), a concept applied in the Cutting Crime Impact (CCI) European project, in which Efus was a partner.23 CP-UDP seeks to positively impact the behaviour of users by embedding protec tive physical features and encouraging prosocial behaviour through good design and place management.

22- Urban Agenda (2020). EU Partnership on Security in Public Space.

23- Efus, CCI (2020). Factsheet on Crime Prevention through Urban Design.

30 31

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

What is the Security by Design (SbD) approach?

As defined by the Partnership on the Security of Public Spaces of the Urban Agenda for the EU, Security by Design (SbD) is an “all-encom passing concept and a new culture that needs to be developed across European cities. It deals with the conception of city planning, urban archi tecture and furniture, flows, and infrastructures in accordance with security issues from the start. It concerns the protection of buildings, public spaces, critical infrastructures, detection methods and technologies.”

In other words, this approach builds on knowledge from physical pro tection, site and target hardening, access control, and surveillance techniques such as CCTV. It is based on the principles of urban resil ience, quality of life in cities, inclusiveness, feelings of (in)security, the co-production of security, and the use of new digital technologies or behavioural sciences.

SbD is also known as Defensible Space, Crime Prevention through Urban Design, Planning and Management, Secured by Design, Design Against Crime, and – worldwide the most widely used term (see ISO 22341:2021)

– Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED).

What is Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED)?

This approach aims to prevent crime, including terrorism, as well as anti-social behaviour and feelings of insecurity. CPTED implies two concepts, both physical and social, which must both be thoroughly tackled in order to implement effective solutions. The approach must always include all stakeholders and actors from all levels of society and from diverse professional backgrounds and expertise. CPTED focuses on a specific area/environment and involves evidence-based action. To function effectively, the approach must be both time and site specific, focusing for example on a particular building. It has proven effective when carefully and accurately targeted, as seen for example in the Netherlands and the UK.24

24- Efus, CCI (2020). Factsheet on Crime Prevention through Urban Design.

Background: the situational crime prevention approach

In the 1980s, Ronald V. Clarke developed the situational crime preven tion approach.25 It focuses on systematic and permanent management, design, or manipulation of the immediate environment, and is directed at specific types of crimes. Situational crime prevention focuses on the settings where crime occurs, rather than on the people committing specific criminal acts. Within the situational crime prevention approach, Cornish and Clarke (2003) proposed 25 strategies and tech niques to prevent and reduce crime.26

In practice: identifying the most suitable local investments for protecting public spaces

The SbD approach was central in all the work carried out by the PACTESUR project. One of the four pillars of the project was the identification of the most suitable local investment for securing open and tourist-friendly public spaces through the development of pilot security equipment/infrastructure in the project’s partner cities – Nice, Liège and Turin – that could be transferred to other European cities. Particular at tention was given to their integration into the urban land scape, natural and cultural heritage, aesthetics, design and urban mobility to avoid the so-called “bunkerisation” of cities. These security devices were considered as complemen tary tools that contribute to security in public spaces but by no means a solution per se.

25- Clarke, R. V. (1995) Situational Crime Prevention, Crime and Justice (Vol. 19), Building a Safer Society: Strategic Approaches to Crime Prevention, pp. 91-150.

26- Cornish, D.B., and Clarke, R.V. (2003) Opportunities, Precipitators and Criminal Decisions: A Reply to Wortley’s Critique of Situational Crime Prevention. See Annex 1 for a more detailed description of the 25 techniques of situational prevention.

32 33

�In Nice, a reinforced anti-intrusion device to protect the Promenade des Anglais was developed, notably to prevent attacks similar to the one perpetrated on 14 July 2016 by a ram lorry.

�In Liège, a mobile vehicle barrier to protect the Place Saint Lambert and Le Carré was set up.

�In Turin, a high-tech crowd control system was installed in Piazza Vittorio Veneto with the aim of avoiding panic move ments, in the wake of the June 2017 disaster during an outdoor projection of the Champions League football final.

In practice: guide for the integration of security systems in public spaces, Brussels-Capital Region

The Brussels-Capital Region, represented by safe.brussels, developed a guide for public space operators, managers and designers explaining the main principles of public space physical security, with a particular focus on terrorist and ex tremist threats and, more specifically, on ram vehicle attacks. It highlights the need to carry out two audits: one on security (threats and risks) and the other on the use value of a particular place. Cross-referencing these audits makes it possible to inte grate safety requirements as effectively as possible into the layout of a public space and the urban furniture. While these audits may be limited to a particular public space, it is never theless recommended to choose a larger scale – a district or municipality – to achieve a coherent overall vision, or even the implementation of perimeters that allow cases to be dealt with

in an organised way. Once the audits have been carried out, the design phase begins.

The guide reviews four types of public spaces and the recom mended design principles for each: streets, pedestrian areas, squares and parks.

> More information here

Security by Design: SecureCity –10 Rules of Thumb

The Partnership on the Security in Public Spaces of the Urban Agenda for the EU developed guidance material for local and regional authorities on architectural and spatial design (the Security by Design, SbD, process).27 Their 10 Rules of Thumb report (2021) aims to support cities and regions in their im plementation of the SbD approach by providing a checklist for its effective application.

> More information on the report here.

27- Urban Agenda (2019). Security by Design: SecureCity, 10 Rules of Thumb for Security by Design (Action 6).

34 35

2.3 Urban planning and

design:

inclusive and safer public spaces

“It is crucial to take into account the influence of urban development on citizens’ feelings of insecurity. If crime can be prevented primarily through social and educational programmes, an interesting approach is also to act on the physical environment itself. Architectural measures, even if they are not sufficient to curb the phenomenon of crime, can limit both the risk of harm and the fear of being a victim of crime.”

2. Diversity

When designing and developing an urban space, the concentration of varied activities (housing, employment and recreation) should be en couraged in order to attract different kinds of public at different times of day and night. It is also important to create rest areas, where resi dents can stop and chat.

Another important aspect is to encourage the mixing of generations: when older residents and younger families share a neighbourhood, older people feel safer.

3. Penetrability

Penetrability means there should be different access routes available, and the “journey” to get to a given public space should be as pleasant as possible:

By providing secondary functions along the route (reinforcing activity, attractiveness, but also social control).

By having a clear definition and structure of the area being travelled through by providing lighting.

Key principles for designing safe public spaces through environmental measures

It is important to bear the following principles in mind when renovat ing or creating a public space: footfall, diversity, penetrability, clarity and visibility, sufficient lighting and attractiveness.

1. Footfall

The number of users in a given public space appears to be the most important factor contributing to general feelings of security. Ensuring that different groups of users are present in a given public space at dif ferent moments of the day and the evening creates a back-and-forth movement that will reinforce social control.

As a whole, a less penetrable environment will result in less social control, which will have an impact on the safety and feelings of insecu rity among residents and users.

4. Clarity and visibility

The public space should be clearly signed and clear to its users: in a structured public space with clear signage, people feel safer and more secure.

Visibility refers to “seeing and being seen”. This means that a sufficient number of people must be present in a given space to see and hear everything, while there must be a certain degree of contiguity, i.e. resi dents can easily get to know their neighbours and the nearby environment.

36 37

Eric Valerio, Architect at the Belgian Ministry of the Interior, and member of the PACTESUR Expert Advisory Committee

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

It is also important to include vegetation, but also to be mindful about its volume and growth to ensure it can be properly maintained and doesn’t obscure the space.

5. Sufficient lighting

A well-lit neighbourhood influences residents’ well-being, comfort and therefore feelings of security. In particular, it helps reduce crime. As a general rule, lighting should only be installed where necessary. The site should not be illuminated blindingly but evenly. People must be able to recognise each other at a minimum distance of four metres.

6. Attractiveness

Other urban design elements can influence feelings of security:

Aesthetics. Citizens appreciate different shapes, sizes and textures. However, universal values apply: for example, nature attracts (greenery, water, warmth, sunshine). On the other hand, wide areas tend to create a feeling of insecurity.

Maintenance and management largely determine the attractive ness of an area. However, the aim is not to create a perfectly main tained neighbourhood either.

Legibility and cleanliness: all the elements that could suggest that the space is deteriorated or abandoned directly affect feelings of (in) security.

Technical sustainability. The design of urban furniture (benches, rubbish bins, etc.) must be sufficiently solid to withstand intensive use and acts of vandalism.

Social sustainability. Social cohesion in a neighbourhood largely determines residents’ feelings of security. Involvement in the neigh bourhood should be encouraged. A sign of recognition, such as offering plants for the garden, is usually enough to encourage people to take care of green spaces or of the cleanliness of their neighbourhood.

> These guidelines are taken from Eric Valerio’s guide for the PACTESUR project. The full version is available here

In practice: the experience of Lisbon, in Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design

The city of Lisbon began to invest in Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) in 2011 with awareness activi ties such as workshops, training for community and other officers of the Lisbon’s municipal police, as well as municipal staff specialised in public space management.

This approach of including CPTED in the community police model seeks to provide local police officers with the following knowledge, tools and skills:

1. Team empowerment with strategies and tools aimed at ensuring that foot patrols actually contribute to improving residents’ feeling of security and well-being.

2. Development and training of technical, relational and insti tutional skills in the community, as well as team reflection about the difficulties and potential in the implementation of this policing model.

3. Enhancement of the quality of the work to be carried out in the territory, providing action lines based on preventive strategies and participatory methodologies for community involvement in security at the local level.

38 39

The CPTED training has improved the identification of problems and their solution and contributed to promoting a more positive and healthier use of public spaces. The coordi nation with other municipal departments such as public space maintenance, urban planning, public lighting, munici pal housing and social services works much better and together more sustainable results are reached.

> More information here.

Case study: exploring human-centred design approaches to public space protection

The Sustainable Design School of Nice (SDS) was tasked with evaluat ing security equipment deployed in the project partner cities of Nice, Turin and Liège, as well as creating innovative security devices and strategies and imagining ways to engage citizens in the process. Since then, this partnership-based course has been exploring the role of design in the protection of public spaces and the need to apply hu man-centred design approaches to security.

The first part of the SDS In/Pact project devised interactive street in terventions, board games and citizen engagement strategies. They questioned the traditional top-down decision-making process in favour of a participatory approach to urban design, shifting perspectives by involving migrants in their user journey.

Occupy is a participatory game inspired by the famous game of pétanque that explores people’s idea of terrorism.

The Citiz Project invited students to focus on Turin’s Piazza Veneto and Liège’s Place Saint Lambert. With no travel possible due to Covid, they conducted their research online by interviewing a wide network of people – local residents, architects, criminologists, designers, police force representatives, psychologists, prevention educators, and urban labs directors.

Students arrived at a strategy of four complementary design solutions organised around simple action verbs: Be informed, Notify, Act and Commit yourself. The solutions presented include an app, a warning bracelet and a shield-like barrier system for public events. The students included in each of their proposed design solutions an evaluation of its impact so that municipal services and police forces would be equipped with an automatic feedback loop integrated in the new devices.

40 41

2.4 The importance of art

“Security professionals, architects, local charities, urban planners and artists must work in a coordinated manner with cities to create secure and peaceful public spaces. Rethinking and reflecting on public spaces’ visual design is vital to increase local residents’ feeling of security.”

Concerning the management of crowd behaviour and movements, students tried to look for solutions that would prevent “tunnel vision” and the “arch phenomenon” that typically creates dangerous bottle necks during large crowd movements. They sought to devise security devices that would be instinctively recognisable, visible, and help fluidify the movement of people towards the exit. The use of sound and smell effects, water projections, visual codes and particularly light as a medium for messaging and directing crowds was at the heart of their early research.

The idea of protective furniture and how the design of street furniture could be used for hiding during a possible attack was also explored in the project.

The PACTESUR Expert Advisory Committee reflected on the role of art in improving public perceptions of the liveliness, safety, image and so ciability of a public space. Indeed, temporary art installations are forms of appropriation of public spaces by citizens.28 Street art is a way of promoting cities' identity and reinforcing social cohesion. It includes a wide range of media in public locations, such as graffiti art, mural painting, flyposting and collage, mosaics and stencilling. Street art opens new avenues for exchange and integration between neighbour hoods and promotes civic participation. Because it is immediate, ac cessible and free, it democratises culture by taking it to the streets.

According to Laetitia Wolff, who led the partnership-based course between the Sustainable Design School of Nice (SDS) and the PACTESUR project, “The notion of security stands at the intersection of multiple dimensions that are all equally meaningful – whether it’s about human needs, ethical values, democratic duties, urban life, environmental standards, or cultural values.”

> This is taken from Laetitia Wolff’s interview for the PACTESUR project. The full version is available here

28- Robazza, G. (2020) Build Art, Build Resilience. Co-creation of Public Art as a Tactic to Improve Community Resilience, The Journal of Public Space, 5(4), 283-300.

42 43

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Michael Nicolai, a Liège-based specialist in street art and a member of the PACTESUR Expert Advisory Committee

In practice: the experience of Street Art in Liège, Belgium

In the spring of 2002, the City of Liège commissioned the non-profit association Spray Can Arts to create a mural painting in a derelict area situated in a densely populated neighbourhood, where various dilapidated houses and sheds had been torn down to build a temporary parking lot. Over time, the space had become filled with litter, rubbish and graffiti.

Spray Can Arts created a monumental fresco of a cheerful scene representing a girl reading a book. A few weeks after the mural was completed, some of the charities operating in the neighbourhood reported that local residents and pas sers-by felt safer and that fly-tipping had significantly de creased. The residents had appropriated the artwork, which had become a rallying point for the neighbourhood. This mural was on display for seven years.

> You can read more here

44 45

© Artists 2SHY (2017), Okuda (2014), Felipe Pantone (2015), Spray Can Arts

In practice: involving citizens in a renovation project, Dunkirk, France

The En rue (“in the street”) project was established through a partnership between the Art and Public Space department of the Dunkirk City Council and the Les Alizées specialised crime prevention charity. The project gathered local residents, social workers, architects, sociologists and local associations.

Part of an overall urban renovation project, its objective was to enable local residents to directly contribute to the develop ment of a public space according to their needs.

A series of meetings were organised with local residents to draw maps and identify the existing resources, the different uses of the public space, and what was missing. With this diagnostic in hand, local residents and other members of the collective developed features such as seating, picnic and play areas, a pétanque pitch and other urban furniture. Local businesses contributed by providing staff and machinery.

Several months after the renovation, the public space has been appropriated by local residents and there has been no damage to the newly installed furniture. > More information here.

Part 3

The use of technologies for protecting public spaces: efficient but not sufficient

46 47

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

The rise in surveillance technologies over the past 20 years has given local and regional authorities a whole new range of tools they can use to better protect their public spaces, notably by enabling 24/7 moni toring, controlling access, or “nudging” public space users’ behaviour. The question for local authorities now is not so much whether to use technology, but rather which technology to use, where, when and how. This is a vast field that can appear a bit daunting in particular for medium and small municipalities that do not have the resources to keep abreast of fast-evolving technological developments. The chal lenge is to use technologies in such a way that public spaces are safer, but also remain open and inclusive while respecting fundamental freedoms and the right to privacy.

Efus’ positioning

Efus helps local and regional authorities to innovate, not only by better using new technologies but also by bringing social innovation to their crime prevention and security policies. Efus’ approach is based on the key principle that such policies, whether they concern the digital or the physical space, must include the respect of human rights, privacy and fundamental freedoms. Even though technologies transform the way police, public authorities and civil society act and react to crime, they do not change the fundamental princi ples that prevention is an effective approach to crime and that social cohesion is key to safeguarding security.

Smart technologies

Smart technologies such as facial or sound recognition are increasingly used by local authorities and other security stakeholders, notably law enforcement, to better protect public spaces. They can also be used to identify the location of victims of floods and landslides or to find people reported as missing. Efficient, although far from infallible, smart tech

nologies should not be considered as a stand-alone solution, but rather be part of a coherent, holistic security approach. They should always be used within a framework that guarantees the respect of privacy and fundamental rights.

The main smart technologies (to date) being used in public space pro tection are:

Intelligent Cameras

• Body cameras (body worn video)

• CCTV (closedcircuit television)

• Drone cameras

Biometric Technologies

• Face recognition

• Fingerprint scanners

• Voice recognition

• Iris scanners

Digital Technologies

• Algorithms, big data

• Predictive policing

Technologies that rely on data generated by citizens

Another aspect of the use of technology for public space security is that of citizen participation. Growing numbers of local authorities through out Europe, as indeed national police forces, are using social media and mobile technologies (apps) that foster direct exchanges with citizens. They can be useful in case of a crisis for authorities to gather information on the ground and inform the public in real time about an evolving situation. They can also help spot an incident and track wrongdoers. But like all other security technologies, they must be used within a clear ethical framework that guarantees fundamental rights for all and the respect of the rule of law.

Predictive tools

Even more sensitive are predictive policing tools, which rely on algo rithms to predict where crime can happen and even who could commit an offence or a crime. These technologies, which are still quite new and bound to undergo many iterations in the years to come, are beyond the remit of municipal or other local authorities as they are intended for

48 49

police. Nevertheless, local authorities should be aware of their advan tages and pitfalls because they are directly concerned by how policing is conducted on their territory and among their resident communities.

Following are some practices and insights Efus has garnered while working on this vast topic of security technologies, either through European projects (PACTESUR, Secu4All, PRoTECT and CCI) or through its ongoing, daily work, in particular its working group on Security & Innovation. The aim of this chapter is to go beyond easy narratives that are either exceedingly optimistic or pessimistic – a common pitfall when it comes to polarising topics such as predictive policing, facial recognition or subjective feelings of insecurity.

Predictive policing is the application of analytical techniques –particularly quantitative ones – to identify likely targets for police intervention and crime prevention or to solve past crimes by making statistical predictions. Predictive policing could be con sidered as a method to predict in which geographical areas there is an increased chance of criminal behaviour, but also which in dividuals and groups – through predictive profiling – are more likely to be involved in criminal activities. 29

Case study: the use of drones for public space protection in Europe

In recent years, the use of drones, or Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS), by public services in urban areas has significantly increased. These systems can carry out effective monitoring and surveillance functions in public spaces. They can be used to prevent potential physical attacks on critical infrastructure (power, water and life systems), airports, open-air events and concerts. Some European cities have established drone units within their municipal police to develop, implement and improve their use in public spaces. However, research is still needed to identify the best way to obtain optimal results. The use of these technologies raises concerns about the right to privacy and data protection. Additional risks are related to potential cybersecurity breaches and malicious uses, such as when drones are used for trans porting drugs or worse, weapons and bombs, or for espionage.

(1) The Drones Unit of the City of Turin (Italy)

“Drones must be considered as one among a whole range of tools and measures used as part of an overall strategy. They must be integrated with actions and technologies that already exist on the ground.”

Prediction-led process (Perry et al., 2013)

The City of Turin coordinates the DronEUnit Network, a European Drone Unit network gathering various Law Enforcement Agencies (LEAs), private companies, universities, academia and research centres whose aim is to discuss how to best use drones to improve certain services offered by municipalities to the public. It uses drones to monitor large events and large crowds, notably to spot individuals in distress and inform emergency services.

50 51

Gianfranco Todesco, Chief Commissioner, Local Police of Turin

Altered

Data

Data Fusion Prediction

Intervention

29- Efus, CCI (2020). Factsheet on Predictive Policing.

Environment

Collection

Assessment

Data Collection Analysis Police Operations Criminal Response

Turin is the first city in Europe that has two drone testing areas (one indoor, the other outdoor):

1. DoraLab, an urban park with an optimal position that guarantees security conditions for the flight of drones.

2. Città dell’aerospazio (“aerospace city”), where pilots are trained to face difficult outdoor conditions such as heavy winds.

(2) The use of drones to monitor public spaces by Police Scotland, City of Edinburgh (United Kingdom)

“All police drone activity is overt and transparent. Deployment must be for a legitimate policing purpose, be safe, legal, proportionate and necessary.”

In Police Scotland, there are two distinct and separate capabilities:

1. The Police Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS) Unit uses drones to keep people safe across Scotland. Drones are used as a quick and effective way to search large or sometimes inaccessible areas that would otherwise take a search team on the ground signifi cant time and resources. The RPAS Unit is of the opinion that drones are not best suited to urban areas due to building dynamics and proximity to people. Public space CCTV and ground resources are found to be the most effective in an urban search. However, drones were used to monitor airborne threats during the COP26 Climate Summit in Glasgow (November 2021)

2. The Aviation Safety and Security Unit (ASSU) employs a range of techniques to protect the public and partners from potential aerial threats. Such mitigations include airspace restrictions, geofencing and trained responders to support and protect legal drone users and to help local police with growing illegal use of drones. Such methods are deployed at sites and for events, operations and incidents.

All Police Scotland drone operations are conducted in line with a Data Protection Impact Assessment (Privacy Assessment), the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and an Equalities & Human Rights Impact Assessment. Police Scotland informs the public or communi ties of a particular area of proposed police drone activity using social media, face-to-face engagement and sometimes leafleting. Community engagement is crucial as it builds trust, reassurance and confidence. All police drone activity is overt and transparent. Deployment must be for a legitimate policing purpose, be safe, legal, proportionate and necessary.

> This analysis is part of the joint interview of the cities of Edinburgh and Turin for the PACTESUR project. The full version is here

(3) The use of drones by the Municipal Police of Madrid (Spain)

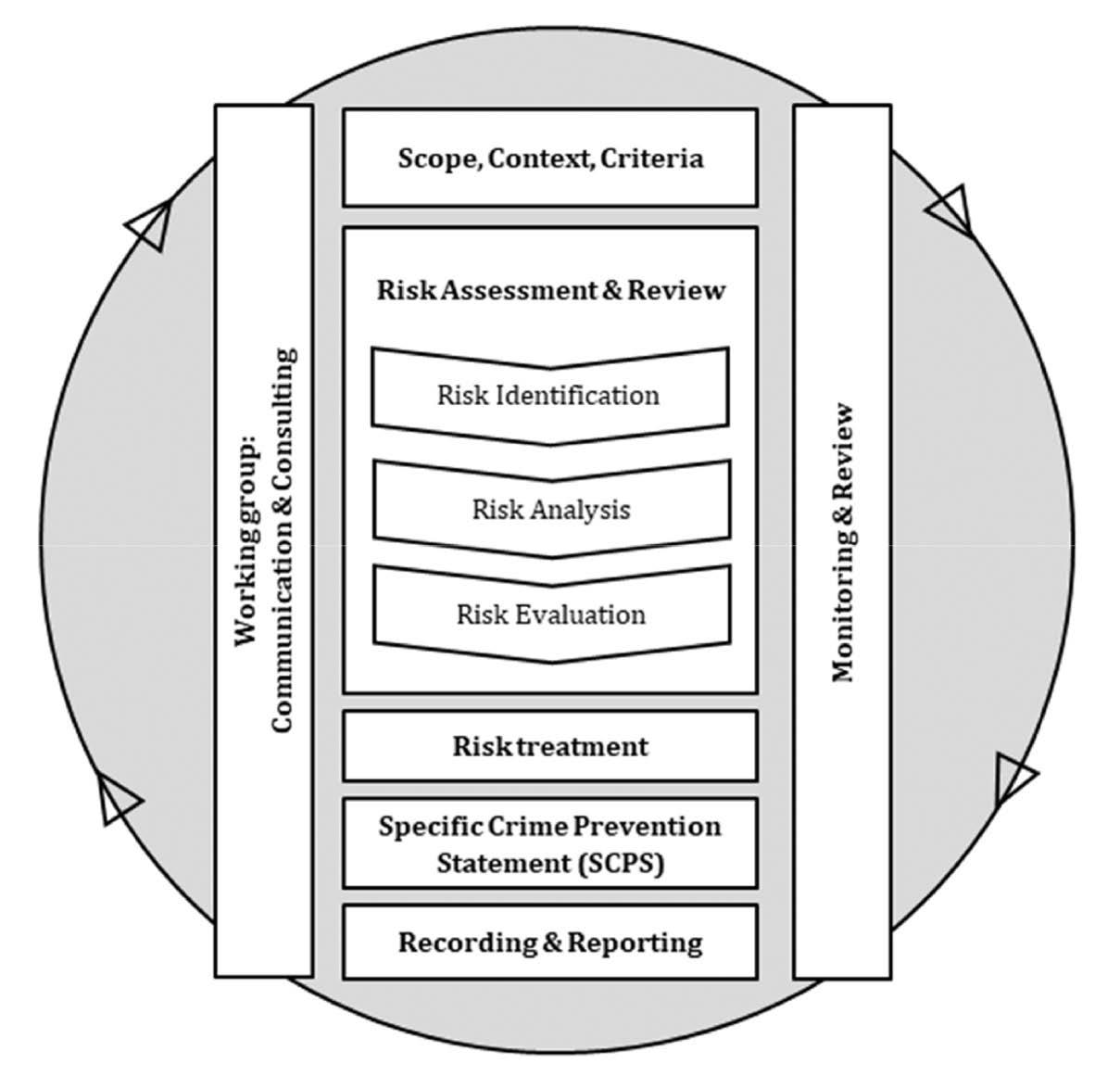

In Madrid, the Air Support Section provides service across municipal departments and areas (including urban planning, firefighters and emergency medical services) and uses drones as follows: