Mitigating Carbon Risk in an Uncertain Market

TITLE SPONSOR:

PREMIER SPONSOR:

THOUGHT-LEADER SPONSOR:

DINNER SPONSOR: LUNCH SPONSORS:

LANYARD SPONSOR:

SESSION LEADERS:

EXHIBITORS:

EXHIBITORS:

LEAD SPONSORS:

BAR SPONSOR:

NETWORKING DRINKS PARTNER: BARISTA SPONSORS:

BREAKFAST BRIEFING SPONSORS:

SUPPORTING SPONSORS:

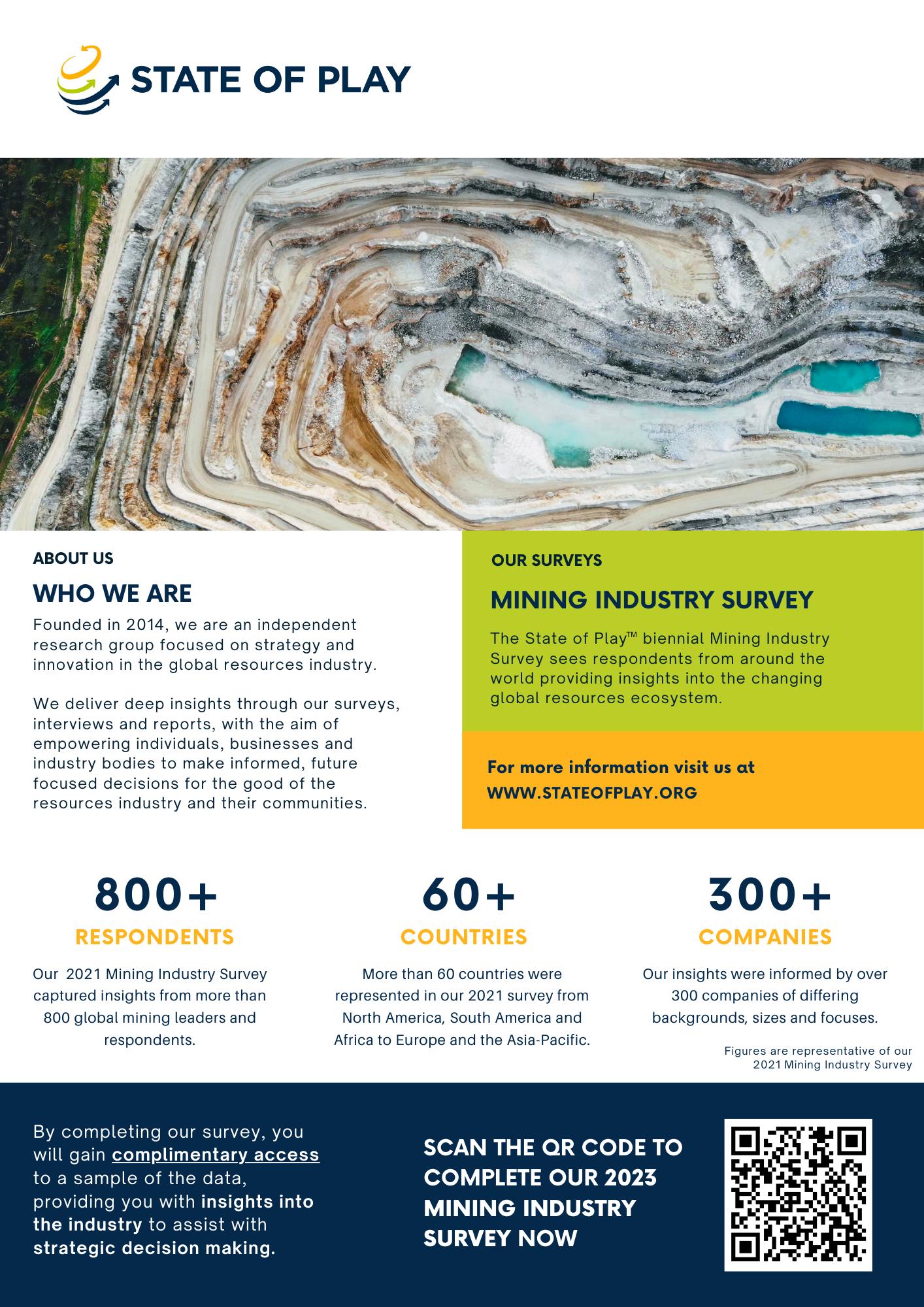

No one company can tackle the decarbonisation challenge alone. Discover how Shell works closely with both partners and customers, mine-by-mine, to identify and develop innovative electrification solutions.

Find us at: Energy & Mines Booth 22

With decarbonisation deadlines looming ever closer, time is ticking for miners to analyse their carbon exposure and mitigate carbon risk. But the complexity of carbon calculation across mining operations and supply chains, combined with a certain lack of consensus around how exactly to quantify emissions, can make it difficult for miners to define a clear pathway to net zero.

The Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Protocol published its first corporate emissions accounting standard in 2001, and carbon calculation has become even more common practice in large companies since the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015. And yet, researchers are still writing papers assessing different carbon emissions models for the

mining industry: in 2022 at least two Chinese academic studies looked at carbon calculation models: one for underground fully mechanised mining processes, and the other specifically for coal mines.

A clear example of the lack of consensus affecting carbon assessments is the divide between analysing exposure in terms of absolute emissions (the total amount of GHG emissions across operations) or emissions intensity (the amount of emissions per unit of output, such as tonnes of metal produced). According to

Jun Song, Vice President, Global Carbon at Macquarie Group, there is no clear answer as to which option miners should choose.

“Absolute emissions and emissions intensity present two different metrics in terms of tracking a net zero commitment which might be in line with whatever ‘best practice’ governs how miners would like to meet their net zero targets on a voluntary basis,” he told Energy and Mines. Song recognises that the biggest challenge is around calculating scope three emissions, and advised miners to seek help where needed. “There’s a lot of ecosystem services that exist out there to help miners to calculate the overall carbon footprint of their operations from source all the way to the end customer,” he added.

The most important step at the beginning of a mine’s decarbonisation journey is to choose a standard to align with, whether it be the GHG Protocol, the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative (VCMI), the Science-Based Targets Initiative (SBTI), or another recognised initiative. These are always evolving, so it is crucial to stay up to date with their requirements.

“On the voluntary side, the sheer number of initiatives, councils, science-based targets and guidelines has potentially created some confusion among participants. There’s still effectively a lack of consensus as to what is accepted and to navigate that (net zero best practice),” said Song. As the carbon market matures, all these initiatives should converge into generally accepted best practices, but for now keeping a finger on the pulse of new developments is important.

For large emitters that fall within the threshold of their jurisdiction’s carbon regulation, the rules to follow are clearer — though the process may not be easier. “On a compliance front, it’s very clear what sort of thresholds are required, what scope is required, and therefore the challenge there may be around not

having the experience, systems or dedicated team to monitor and make the calculation. Here, they may rely on advisers such as Big Four and other environmental consultants to help them get started on that journey,” added Song.

Once miners have clearly mapped and understood their carbon footprint, they can put in place a reduction and mitigation strategy to lower their carbon risk. Carbon offsets, which companies can purchase from sustainable projects to compensate for hard-to-abate emissions, have a role to play here, as long as they are part of a holistic strategy. Song explained that miners who do not have any direct activities to reduce their carbon footprint and solely rely on offsets are at risk of being criticised and potentially associated with greenwashing. The key is to avoid emissions wherever possible, reduce the emission intensity of operations, and finally use offsets to bridge the gap between reductions and net zero targets.

Recent standards and regulations make it clear just how much decarbonisation can be achieved through offsets. That’s the case of the upcoming revamped Safeguard Mechanism in Australia, which covers 215 sites, each emitting more than 100,000 tonnes of CO2 a year, and is expected to be finalised this July. Most of the companies in the scheme will have to cut their emissions intensity by 4.9% a year, and will be allowed to use offsets to meet part of this decarbonisation target. And while the legislative proposal does not explicitly limit the use of carbon credits, it does state that if more than 30% of the emissions reduction requirement is achieved through offsets, the company in question will be required to justify “why onsite abatement hasn’t been undertaken” to the Clean Energy Regulator. It doesn’t mean the decarbonisation strategy will be rejected, but this trigger point is an indication of the amount of carbon offsetting that is

considered acceptable by regulators.

When it comes to carbon offsets, it’s not just quantity miners should worry about: recent controversies have highlighted discrepancies between the carbon avoidance or absorption projects claim to achieve and their actual results. In light of these, it can be stressful for miners to choose the right offsets for their company. The exercise is made even more difficult by the fact that in the carbon world, quality remains a subjective term, with no clear consensus as to what constitutes a quality carbon credit. Initiatives like the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM) and its Core Carbon Principles are actively working to bridge this gap, but in the meantime, Song recommends basing offset purchase decisions on three pillars.

“The first is carbon integrity, which relates to the underlying inputs that underpin how the carbon reduction, removal or avoidance is calculated: not every ton equals a ton. The second is co-benefits, and other positive aspects for nature, or the communities in which the projects operate. Lastly it’s about

the alignment to the operation itself: how does this cohesively tie together for the actual use of the offset in the context of its removal and reduction efforts in the supply chain and social licence to operate,” he noted.

Once miners have chosen their offsets, they have several options to purchase them. As Anton Lovelle, Macquarie’s Vice President of Asian Gas, Power and Emissions, explained, the right choice will depend on each company’s specific requirements, such as price certainty, volume certainty, or even the business’s preference for methodologies or location.

According to him, one straightforward approach involves purchasing spot units from established market participants — units which can either be retired on behalf of the business or held on its balance sheet and retired as needed.

Another option is the forward purchase of carbon credits. “As companies gain more confidence in their liabilities, they can engage in forward transactions to secure a fixed volume

of offsets at a predetermined price and delivery date. The two counterparties involved in such transactions can arrange for the transfer and retirement of credits. If the credits are not required on the agreed-upon date, Macquarie can facilitate carrying them forward to a new agreed date, subject to an agreed interest rate, before retiring them,” said Lovelle.

Today, more complex structures such as options or hedging strategies involving variable volumes and prices are gaining popularity, particularly among commodity players already familiar with such practices. It is also possible for miners to invest directly into carbon offsetting projects by collaborating with upstream participants. “While this approach carries certain risks, such as unknown volumes or delivery timelines, it provides access to more affordable credits,” explained Lovelle. “By delving further upstream, businesses can tap into carbon abatement opportunities that align with the marginal cost of abatement, regardless of prevailing market prices.”

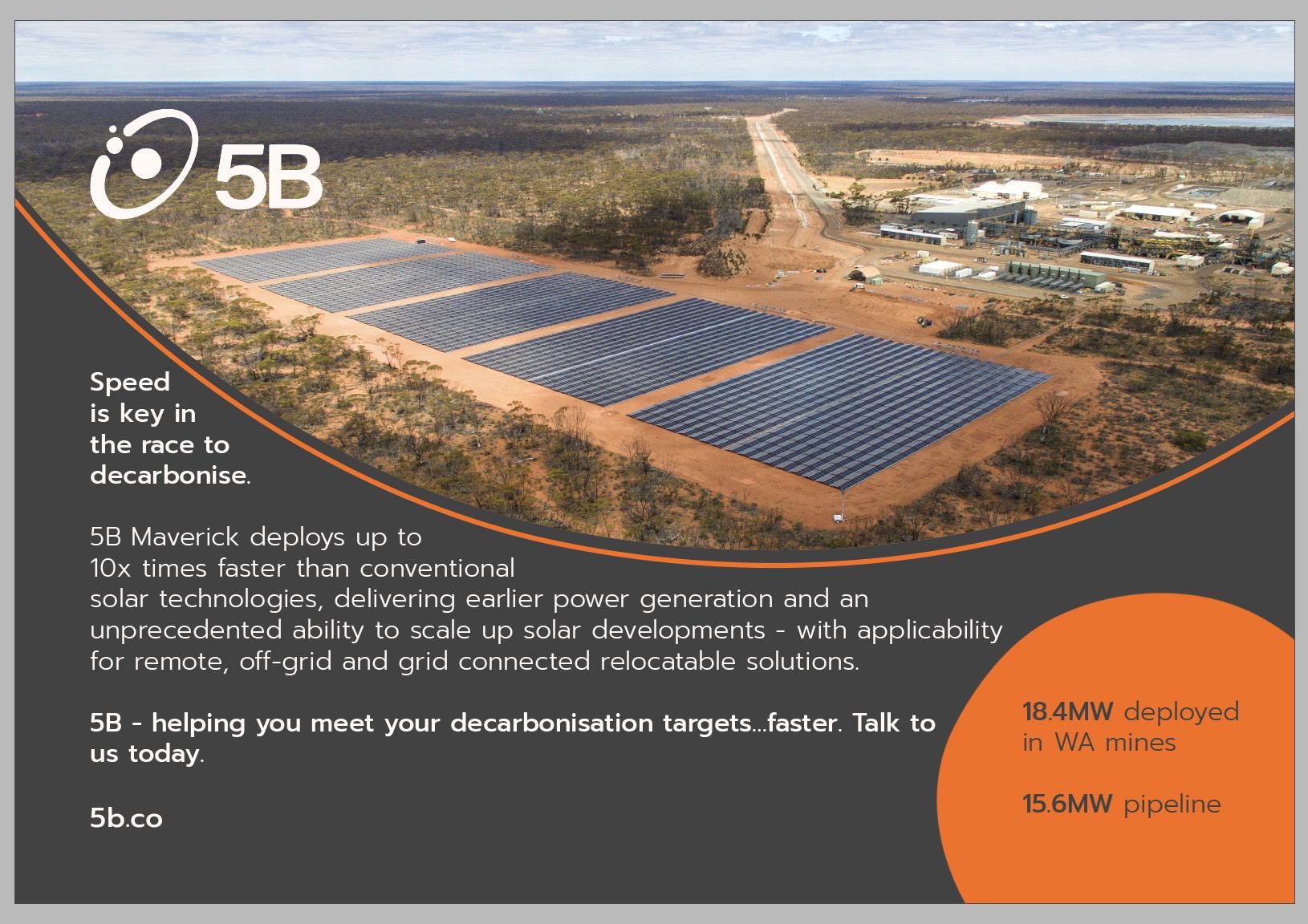

Save up to 30% in electricity costs with hybrid renewable energy solutions

CrossBoundary Energy ensures savings while also reducing your carbon footprint, power cost volatility, and technical risk through outsourcing your power needs. This means you can fully focus on mining to achieve your investors' returns.

Find out more: www.crossboundary.com/energy

The energy transition has well and truly arrived. With 88% of global emissions covered by net-zero emission targets in 2022 (up 35% since 2020) and 35% of Australia’s total electricity generation coming from renewable energy (which has doubled since 2017), the question is no longer if companies should rise to the climate change challenge, but how.

Despite these steps forward, there is still a disjoint between targets and progress when it comes to decarbonisation. Evidence suggests there is a gap between national commitments and efforts to enact those commitments, with countries needing to cut 45% off current greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 to limit global warming to 1.5°C.

Given how little time we have left to make change, the question then shifts to how we can achieve these goals and how can incentives accelerate change?

The risk and capital required for transition is high. In the State of Play Electrification report, 88% of industry see cost as being the major risk of electrifying a mine site and 42% of industry believe risk aversion is one of the biggest inhibitors to electrification. To overcome this is going to require more than just targets. It will require focussing on the value accrued to miners from the transition.

Electrification creates opportunities for both operational efficiencies and cost savings. The conversion efficiency of electric vehicles is significantly higher, around 77%, compared to 12-30% of internal combustion engines. In the current mine environment, energy costs contribute significantly, typically 25-30% of overall operational costs. Renewable energy costs continue to fall however, with almost two-thirds of the newly installed renewable power in 2021 having lower costs that the world’s cheapest coal fired option in the G20.

From a market perspective, there are a number of ways that companies and the broader industry can benefit from reducing the carbon intensity of their products. Examples include through premium pricing, social licence to operate, access to cheaper capital and green subsidies.

The concept of green premiums is a contentious topic. Industry is yet to see it play out at scale, however it is anticipated that if companies can produce their commodities with lower emissions and greater ESG stewardship, customers may be willing to pay a slightly higher price for the product. Industry agree that market segmentation based on carbon intensity is viable - 77% of the mining industry believe there will be a carbon-based price differential in the next 5 years. Most recently, South32 have seen European carmakers actively choosing to pay an extra $10 to $15 a tonne for their green aluminium.

If the differential does not come in the form of pricing, it will likely morph into a condition of supply. As downstream customers are forced to reduce scope three emissions, they will prioritise lower carbon intensity material supply, leaving

producers that have a higher emissions profile with a smaller customer pool. This will only intensify as more global policy support and government mandates are implemented. The EU has already released mandatory requirements on the carbon footprint in lithium-ion battery production, requiring all lithium-ion batteries to have a label showing carbon intensity performance from 2026. Northvolt, the leading European battery maker, has announced it will carry a carbon footprint which is approximately one third that of comparable industry producers, with an aim of targeting a 25% share of the global battery manufacturing market by 2030.

The finance sector’s role in decarbonisation has become increasingly important. Investment must triple for the rest of the 2020s to achieve net zero. Commercial banks need to look past the immature nature of some markets, which is currently preventing them from funding projects due to their risk profile. Institutional investors need to look past short-term returns and their scepticism about climate risk exposure.

Despite all that needs to be overcome, the sector is becoming increasingly aware of its role in shifting the cost of capital to being favourable for green projects. Investment in the energy transition exceeded $1.1 trillion dollars in 2022, for the first time equalling investment in upstream oil and gas and unabated fossil fuel projects. The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero has seen its membership grow by over 20% and it is estimated that bad emission projects can expect to pay up to 25% more for their capital than good ones.

Aside from capital costs, carbon pricing mechanisms (both voluntary and compliance) will continue to play an

increasingly important role in the transition. More than 40% of greenhouse gas emissions were covered by carbon prices in 2021, and the voluntary carbon offset market is predicted to grow from around $2 billion in 2022 to about $100 billion in 2030.

With the recent updates to Australia’s safeguard mechanism, more producers will be subject to financial penalties for producing carbon. In addition, companies who fail to deliver emission reductions within their operations will have to purchase carbon offsets within the voluntary carbon market in order to meet their decarbonisation targets.

Accreditation will become increasingly important to allow the benefits of decarbonising to come to fruition. The industry requires precise performance measurement, validation of performance and transparency and benchmarking for companies to differentiate on the basis of the embedded carbon of their products. Carbon measurement technologies that track lifecycle emissions of products are relatively mature in other industries (such as fast-moving consumer goods), however considerable development is still required to produce a solution that services mining.

The ability for companies to be transparent in their carbon emissions will result in accountability and creates real value for those involved. Accessing finance at a cheaper rate will become more viable as banks and investors will be able to accurately track emissions, and we may see even more of an emergence of premium pricing and preferential supply. Several exchanges have introduced their own certification bodies, including the London Stock Exchange, who have

introduced a ‘Green Economy Mark’ for those who constitute a ‘green’ business, however a more sophisticated and specific approach for mining is required.

There is much to be done in the transition to net zero. Decarbonisation requires more than just effort from a single party, but rather a collective effort from all aspects of industry. Mining companies must recognise the true value of decarbonisation, both from an improved efficiency and reduced cost perspective, as well as the value that can be accrued from greater environmental stewardship. The government and finance sectors must put the right policy and accreditation levers in place to make sure emissions reductions are incentivised and rewarded.

The State of Play Mining Industry Survey is now open. Every person who completes the survey receives free access to a sample of the data. You can access it HERE.

genus.com.au

As miners move towards fully decarbonised mine sites, Caterpillar’s Asia Pacific Hybrid Energy Solutions Manager, Adrian Constable, tells Energy and Mines how to best prepare for renewables-run electric fleets.

Energy and Mines: What are some of the main elements miners need to consider when working towards decarbonised power and mobility?

Adrian Constable: To decarbonise a mine, a good first step is to analyse the current carbon emissions from all processes and categorise these into Scope 1, 2 & 3 emissions. Pay careful attention to analyse each electrical load and mobility process in detail. Then, prioritise the areas where the biggest impact can be achieved.

Some of the main elements miners may need to consider when working towards decarbonised power and mobility are:

• Feasibility and affordability of using renewable energy sources and energy storage systems to reliably power operations and mobility on site, considering the space and solar/wind resource available.

• Current price of storage and potential for load shifting

• Technological innovation and adoption of electric vehicles and machinery that can lead to reduced fuel consumption, maintenance costs, and emissions

• Automation of vehicles and intelligent management of their charging to enable efficiency and electrical load stability

• Scalability of the solutions and optimal size for financial and environmental benefits with ease of expansion as factors allow

• “In-the-pit” charging electrical infrastructure and its potential mobility requirements

• Efficiency optimisation, such as optimising load processes to enhance productivity or spinning reserve that can be replaced with virtual spinning reserve from energy storage systems like the CAT Power Grid Stabiliser while also providing transient assist for grid stabilisation

• Exposure to fossil fuel price fluctuations and the motivation to reduce it

• Market demand and price fluctuations for critical minerals that are essential for the energy transition, such as copper, lithium, cobalt, and nickel

• Regulatory and policy frameworks that support or hinder the decarbonisation efforts of the mining sector, such as carbon pricing, subsidies, standards, and reporting requirements.

• Training – for example, updated and expanded electrical skills.

E&M: Mines are now incorporating an increasing percentage of renewables into their hybrid plants: how could this impact their electrification ambitions?

AC: On the positive side, incorporating more renewables into hybrid power plants could help mines reduce their dependence on fossil fuels, lower their operating costs and emissions, improve their energy security and reliability.

Incorporating a high percentage of renewables could also pose some challenges for mines, such as the intermittency of renewables, the integration and management of complex energy systems to balance both this intermittent renewable power and potentially newer mobile fleet variable charging loads, the higher upfront capital costs and payback periods, and the potential trade-offs between land use for mining and increased renewable energy production.

One example of a solution that can address some of these challenges is leveraging fast response and flexible Energy Storage Systems to provide power stabilisation to smooth both the intermittent renewable power and variable electrification charging loads. Caterpillar designed the BDP1000 inverter with an ultra-fast automatic response and patented transient assist non-linear droop algorithms with this type of application in mind. One then can combine this with intelligent load controllers and charging infrastructure. Caterpillar’s advanced hybrid energy controls and distributed power generation expertise combined with learnings from our zero-emissions battery electric mobile equipment, allows us to enable mines to integrate more renewables into their hybrid power plants and electrify their mobile mining equipment. Having a single vendor providing both mobility electrification and hybrid energy solutions with integrated control systems can be a positive advantage for mines.

E&M: How can mines prepare their power systems and

AC: Mines can prepare their power systems and operations for a move towards fleet electrification by:

• Conducting a comprehensive assessment of their current and future energy needs, demand profiles, load factors, and emission levels.

• Developing a clear electrification strategy and roadmap that aligns with their business objectives, environmental targets, stakeholder expectations, and regulatory requirements.

• Identifying and evaluating the most suitable renewable energy sources and storage options for their site-specific conditions, such as solar PV, wind turbines, batteries, hydrogen fuel cells, etc.

• Investing in upgrading or building new infrastructure and equipment that can support the electrification of their mining fleet, such as electric trolley lines, charging stations, electric vehicles and machinery, smart meters and controllers, etc.

• Engaging early with relevant stakeholders and partners to facilitate knowledge sharing, collaboration, innovation, financing, and policy support for their electrification initiatives.

Mine sites are complex, and each operation is unique. So, in our relationships with customers, we focus on a specific and collaborative approach to address customers’ unique challenges. In some cases, a customer’s goal requires a product that does not yet exist, so we focus on frontline customer input as Caterpillar designs and develops nextgeneration solutions to meet their needs. For example,

Caterpillar signed a series of transformative agreements with key mining customers in 2021. Through these collaborative agreements, we are developing and deploying customised, site-specific solutions to achieve our customers’ bold sustainability objectives to reduce or eliminate greenhouse gas emissions at their sites.

Caterpillar’s engineers are reimagining our machines at mine sites, enhancing them with alternative power sources and ensuring compatibility with renewable fuels. These solutions help customers run more fuel-efficient sites—reducing greenhouse gas emissions while supporting their total cost of ownership objectives.

What customers really want are sites that are safe, predictable and productive. That’s where Caterpillar stands apart from competitors, delivering key autonomy, alternative fuels, connectivity and digital, and electrification (AACE) technologies. Our MineStar technology suite enhances safety, productivity and profitability. It also allows for optimised energy management, as the site functions as a connected system.

E&M: What is the best way to integrate all infrastructure requirements to become all-electric?

AC: There is no single best way to integrate all infrastructure requirements to become all-electric, as different mines may have different needs, constraints, and opportunities. However, some possible ways to integrate all infrastructure requirements are:

• Adopting a modular, scalable, and flexible approach that allows for incremental expansion, adaptation, and optimisation of the infrastructure over time

• Recognising mobile “in-the-pit” distribution, power and load infrastructure may be required

• Having an intelligent re-deployable grid forming, high inertia battery energy storage system and mobile equipment charger package

• Leveraging digital technologies to monitor, control, and optimise the performance, efficiency and reliability of the infrastructure

• Collaborating with other mines or local communities to share or co-locate infrastructure assets, such as renewable energy plants, storage facilities, transmission lines, etc., to reduce capital expenditures and operational risks

• Engaging the mobile equipment and power OEMs early. Those that understand renewable energy, energy storage, electric energy distribution, local industry standard and

ambient condition, electric mining machine capability and charging, operating, maintenance.

E&M: What are the inputs that can help mines determine electrical loads and sizing for renewable energy and storage systems to move to electrified sites?

AC: To determine electrical loads and sizing for renewable energy and storage systems to move to electrified sites, mines can consider the amount of energy required by the mine site (which may be a combination of today’s electrical load and fuel consumption for traditionally powered mobile fleets), as well as electrical and haul load profiles, productivity targets, details of mobile fleet, power quality targets, renewable energy resource and available space, the type and size of bi-directional power inverter to support high intermittency of both load and power sources, and combined renewable energy and load modelling with financial parameters.

Some examples of technologies that can help decarbonise power and mobility are electric mining trucks such as the battery electric Cat® 793 zero-exhaust emissions autonomous haul truck; Cat® R1700XE underground battery electric loaders, Cat® MEC500 mobile equipment chargers, automated energy controls and power management, moveable distributed power and energy storage systems, eg. Cat® PGS1260HD. Caterpillar’s MineStar technology suite for staffed and automated mines converges to create and maximise value and safety for our customers at the site level.

With the introduction of Cat® Hybrid Microgrids that incorporate solar, wind and battery energy storage, and generator sets capable of running on green hydrogen, Energy Power Systems Australia (EPSA) is helping customers transition to renewable energy, mitigating the risks and maximising the commercial and environmental benefits of emerging technologies.

EPSA rents, sells, designs, engineers and commissions Cat® engines, generators and custom-built power solutions – from individual units to multi-megawatt power stations. Talk

Between ambitious decarbonisation targets, fast-changing technologies and increasingly unstable weather, long-term business planning is more challenging than ever for mines. ENGIEImpactWALeaderAmySteeloffersstrategiestohelp minersmanagetheclimatetransition.

EnergyandMines:Howaredecarbonisationgoalsbeing integratedintobusinessplanning?

AmySteel:Integratingdecarbonisationgoalsintobusiness planningistypicallyphasedduetoorganisationalsilos. Organisationsneedtoensuretheirdecarbonisation commitmentsarecomplementarytotheirwidercorporate aspirationstounlockcompetitiveadvantage.

AccordingtoENGIEImpact’sresearch73%ofleadersresponded thatthelackofcross-functionalapproachwasabarrier. Organisationscanovercomethisbyinvolvingthebusiness planningteamintheassessmentandroadmappingprocessfor decarbonisationoptions.Activeparticipationfromtheteamin meetings,wheretheycan askquestionsandchallenge assumptions,fostersabetterunderstandingofdecarbonisation technology,risks,timing,andcosts.Thisleadstotheintegration oftheseassumptionsintothebusinessesimplementationplan overtime,helpingtofacilitateasmoothtransitiontowardsa moresustainablefuture.

E&M:Whataretheprosandconsofaphasedinapproach todecarbonisingpowervs.investinginthehighest penetrationofrenewablesandstoragefromtheoutset?

AS: A phased approach to decarbonising power offers a range of pros and cons compared to investing in the highest penetration of renewables and storage from the outset.

Pros of a phased approach:

No-regrets investments: A phased approach enables businesses to make no-regrets investments while there is still uncertainty about the ideal zero-carbon end game. Companies can invest in renewable energy technologies with confidence, knowing they are making progress toward their decarbonisation goals, even if the exact path to a zero-carbon future remains unclear.

Technology cost reductions: Deploying the system in phases can result in a more favourable overall net present value (NPV) because technology costs are expected to decrease over time, especially in the harder-to-abate and emerging technology categories. Waiting for more cost-effective solutions can make

large-scale decarbonisation projects more financially viable.

Capital allocation: Implementing a phased approach can help manage the challenge of finding the large amount of capital required to deploy a 100% renewable energy system. By breaking down the investment into smaller, incremental steps, companies can more effectively allocate resources and manage their capital expenditure.

Adapting to system changes: As various components of the energy system change, such as the electrification of vehicle fleets, new load profiles will emerge. A phased approach allows for adjustments and reinvestment to accommodate these evolving load profiles, preventing potential inefficiencies or disruptions in the system.

Cons of a phased approach:

Locking into fossil fuel contracts: Phasing may be less effective if it results in locking into long-life contracts for fossil fuels, which can delay decarbonisation efforts and run the risk of higher carbon price exposure or stranded assets. Companies must carefully evaluate their long-term commitments and consider the potential implications for their decarbonisation objectives.

Greenfield site opportunities: For greenfield sites, the entire plant may be designed for zero carbon from the outset, which can save incremental switching costs as technologies and systems change or come online. In such cases, a phased approach may not be as advantageous as building a fully decarbonised system from the start.

Insufficient initial impact: If the initial renewable energy system size is too small, it may not have a noticeable impact on emissions, leaving the company lagging behind its peers. A phased

approach needs to ensure that each stage of implementation contributes meaningfully to emissions reductions to maintain competitiveness and credibility in the market.

Potential inefficiencies: A phased approach may create inefficiencies in system design and integration, as new technologies are added over time. Companies need to carefully consider the long-term implications of each phase and its impact on the overall system to minimise inefficiencies and maximise the benefits of their decarbonisation investments.

E&M: How can mines plan and design around technologies not yet available?

AS: Mines can utilise scenario-based planning to analyse different technology options and combinations through modelling various alternatives to plan and design around technologies not yet available. This method helps identify essential technologies, create stage-gates and decision points, and provide price signals indicating favourable technologies for deployment in the mine. By using scenario-based planning, mines can effectively navigate uncertainty and make informed decisions about the best course of action for their decarbonisation efforts.

E&M: How are miners taking into account and integrating climate risk into their decarbonisation plans?

AS: The mining industry is no stranger to harsh climates, but forecasts of hazards such as heavy precipitation, drought, and heat indicate these effects will get more frequent and intense, increasing the physical challenges to mining operations as well as power outage events across both variable renewable energy and traditional energy generation. However, integrating physical climate risk into decarbonisation has been rarely done to date.

As extreme weather events grow in both frequency and magnitude under the changing climate, decarbonisation plans should be adapted to build resilience to these more potent extremes. Mining companies should also be planning for shifts in chronic conditions such as wind patterns, solar irradiation and temperatures which can impact the generation profiles of solar PV and wind.

E&M: What are the challenges of developing strategies for Scope 3 emissions and how can mining companies navigate these?

AS: The mining industry is one of the largest industrial contributors to global greenhouse gas emissions — accounting for 4% to 7% of scope 1 and scope 2 emissions globally. This number goes up to approximately 28% of global GHG emissions when indirect scope 3 emissions are considered.

Mining companies must take a stewardship role in reducing Scope 3 emissions, even if they have no direct control over them and approach this challenge as an opportunity to gain a competitive advantage. To effectively reduce scope 3 emissions, mining companies must:

Have an accurate understanding of their scope 3 footprint and set an ambitious yet attainable scope 3 target in line with leading frameworks.

Engage with suppliers and customers within their value chain to improve data accuracy and support value chain decarbonisation efforts.

Identify and implement mitigation efforts that reduce scope 3 emissions and business risk, while demonstrating financial returns where possible.

Get all levels of the company on board. It is impossible to make lasting changes without organizational buy-in at every level of the company.

Improve reporting and transparency of scope 3 emissions.

Tackling scope 3 emissions is challenging and requires coordination across a number of players within the value chain. Developing partnerships to reduce emissions and align reporting requirements is therefore an opportunity that the industry should embrace.

We help you progress your business with better and cleaner energy solutions throughout the life of your mines.

As mining specialists, we understand the energy you require to operate effectively, no matter where your mine is located or how complex your need. We also understand the practical challenges of reducing your carbon emissions. That’s why we’ll work with you and use our deep expertise to develop the right choice of solutions and services that gives you the energy you need.