Inside:

Seafaring stories

Columbia River Maritime Museum looks to include more perspectives

Columbia River Maritime Museum looks to include more perspectives

Dozens of vessels now in storage at the Columbia River Maritime Museum's warehouse are slated for Mariners Hall, including a 60-foot racer shell.

Jeff Smith answers many calls from owners of historic boats interested in adding to the Columbia River Maritime Museum’s collection. But as the museum’s curator, he knows only a few will make it into exhibit halls.

He’s looking forward to seeing more on display in the next few years.

Many vessels are now in storage, like the Merrimac, a wooden yacht constructed in 1938 by Astoria Marine Construction Co., which will undergo further restoration before moving into Mariners Hall, a new addition to the museum set to break ground in September and open in the summer of 2026.

The new building will add more than 24,000 square feet of exhibit and education space to the museum. That means dozens of boats and other artifacts will move from storage onto public display.

“ It’s about the human experience, the mariner, hence the name Mariners Hall, just to show we’re really focused on the people that built these boats and other craft, that operated them, that maintained them, how it impacted our community. “

Bruce Jones

Columbia River Maritime Museum executive director

'It’s about the human experience'

Museum leaders see the expansion as a chance to broaden their focus on the human side of the Columbia River’s maritime culture.

“It’s about the human experience, the mariner, hence the name Mariners Hall, just to show we’re really focused on the people that built these boats and other craft, that operated them, that maintained them, how it impacted our community,” said Bruce Jones, the museum’s executive director.

Jones, a former commander of U.S. Coast Guard Sector Columbia River and a former Astoria mayor, stepped into the position last year after serving as deputy director. He’s the sixth to hold the title since the museum was founded by illustrator and collector Rolf Klep in 1962.

With Mariners Hall, Jones sees an opportunity to build on a long-standing vision, to add to storytelling in place and touch on more elements of maritime life, like recreation, logging and aviation.

Exhibits planned for the wood-framed structure include a 60-foot racing shell built by George Pocock, a salmon tender built by Wilson

Brothers in Astoria and a log bronc, which was used to corral lumber for transport along the river.

Another area of focus will be aviation, with plans to suspend a Coast Guard search and rescue helicopter 15 feet above the ground floor.

“Aviation is a huge part of the maritime world,” Jones said. “During World War II, the Navy had a seaplane base at Tongue Point. Of course, the Coast Guard came here with helicopters in 1962 and has been here ever since, and now the bar pilots operate a helicopter.”

Visitors will get an eye-level view of the helicopter from a mezzanine deck, where they’ll also get an aerial view of boats on the ground level.

“When you’re on the mezzanine, you’ll be able to look right into the cabin of the helicopter. You’ll see the pilot, and see the hoist operator and the rescue swimmer. They’ll all be sculpted figures,” Jones said.

A similar concept is planned for the boathouse, an area at the southwest corner of Mariners Hall that will fit floating docks on two levels. Those will be arranged for views above and below the waterline.

“You can look up and see the bottoms of the boats from the ground floor, and then when you get up on the second floor, you’ll be looking at them straight on,” Jones said.

Some exhibits will be interactive, like the 52-foot motor lifeboat Triumph II, which was a lifeline for fishermen at Point Adams and Cape Disappointment for more than 60 years.

“We’re going to let people get on the back of the Triumph, on the stern, and when they look behind the boat, they’re going to see a big wraparound monitor with a video of towing a disabled boat in heavy seas, so you’ll get a sense of motion,” Jones said.

Another restoration project underway is on a first-order Fresnel lens that once beamed from Cape Mendocino Lighthouse in Humboldt County, California. In recent years, the lens was placed in storage by the Coast Guard after it spent decades housed in a replica at the county fairgrounds in Ferndale, California.

“It’ll be restored in pieces in the warehouse and eventually put back together, reassembled one piece at a time,” Jones said. “The few places you can go to see a first-order Fresnel lens on display, they’re really breathtaking.”

In addition to the exhibits, plans for the second exhibit hall include space for indoor and outdoor education programs.

“This has been a long-awaited opportunity to actually build a classroom,” Jones said. The museum’s education programming, he added, reaches more than 20,000 people each year, including thousands of local students who are learning about the Columbia River.

It’s a subject so vast that even with a new building, Jones said, “there’s still lots of stories we won’t be telling.”

Some of those could appear sooner as temporary and semipermanent displays.

In September, the museum will close two exhibits along the south wall of the main building to open the Gallery of Opportunity, a corridor that will eventually connect the main museum with Mariners Hall.

The gallery could provide space to rotate exhibits and stand-alone artifacts.

“The wall separating this gallery from the other galleries is about 3 feet deep, and we’ll have built-in casework, so we’ll be able to feature isolated items along that wall and tell more specific stories about specific objects,” Smith said. “Sometimes you have an object that has got a terrific story, and it’s just one object.”

A permanent exhibit in the gallery, created in collaboration with the Chinook Indian Nation, will welcome visitors to Chinook land and acknowledge other Indigenous tribes represented in the museum.

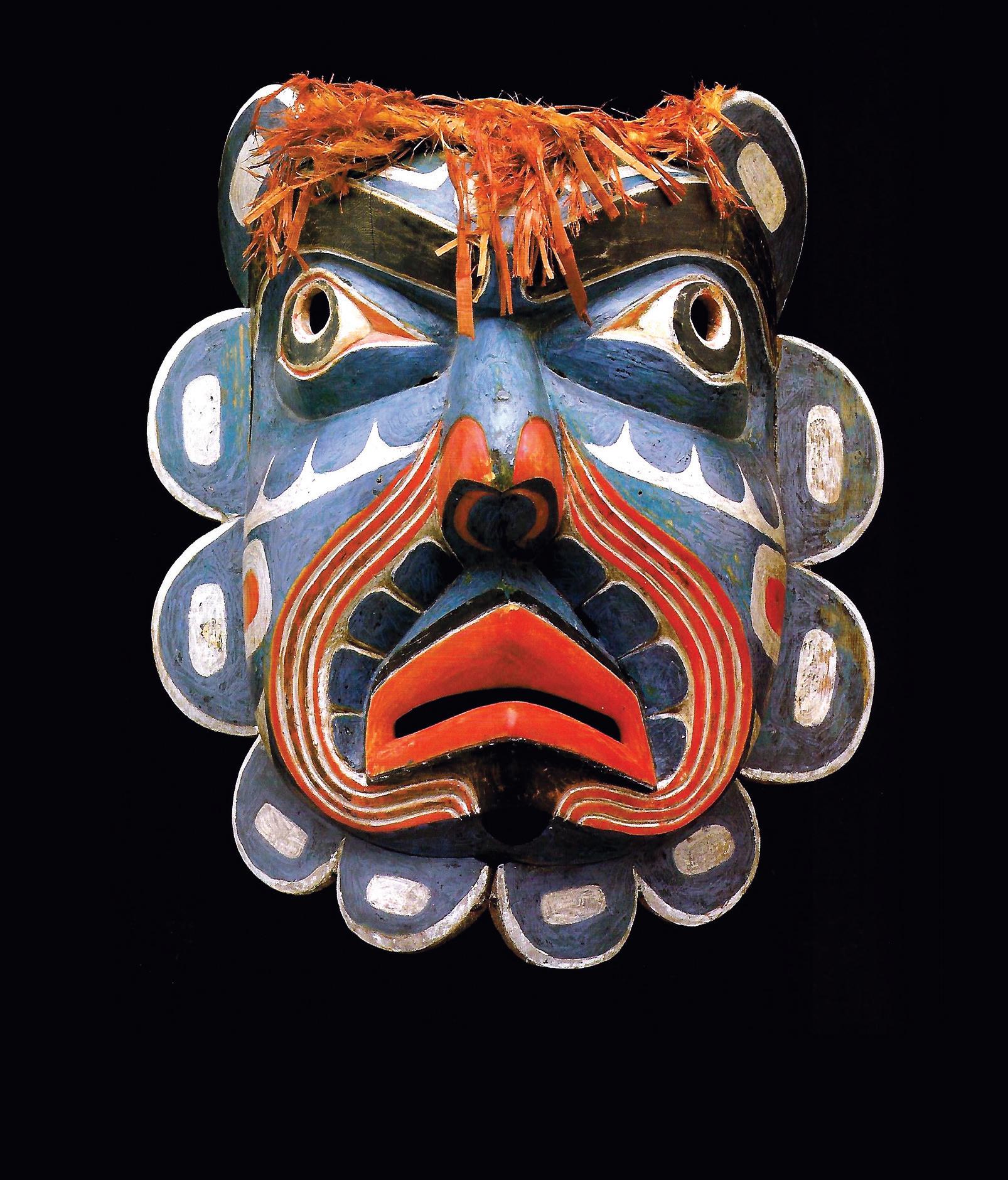

Much of that representation will appear in Cedar and Sea, a permanent exhibit that will open in September.

Smith described the exhibit’s scope, which focuses on the maritime culture of Indigenous groups ranging from Alaska to southern Oregon, as reaching “the Northwest Coast wherever the cedar grew.”

The cedar tree has traditionally been used to construct canoes, longhouses and tools. “It provided clothing, it provided housing and transportation,” Smith said. “That developed in this specific region because that’s where these trees grew.”

The exhibit begins with a forest scene and moves through creations made from cedar.

“There’ll be sounds and a panoramic photo that shows the forest and a simulated tree that you walk past and it talks about the significance of the cedar tree to Indigenous cultures,” Smith explained.

From there, three walls will be dedicated to showing materials like shells, bones, bark and plants often harvested near the coast.

Displays of early tools and handcrafted items will illustrate ways of working with cedar and how methods have adapted over time. A half-dozen monitors will introduce contemporary artisans, including a woman harvesting cedar bark.

“We talk about the wherefores and whys and the material and how it’s done, and then there’s a contemporary story that features a contemporary living artist who is practicing those traditions today,” Smith said.

One of those artists is Joe Martin, a Tofino, British Columbia, carver whose Nuu-chah-nulth-style canoe is planned as a centerpiece of Cedar and Sea.

“There’s two large cases in the middle, flanking the canoe, that will feature all these different art forms and cultural materials,” Smith said.

Other displays will feature weaving, knife-making and carving processes. One will introduce David Boxley, a Tsimshian carver living in Seattle, who makes traditional cedar bentwood boxes together with his son.

The conclusion of the exhibit will show historic and contemporary Indigenous methods of fishing.

By doing so, it’s filling in a gap, one that the museum hopes to continue to close as it works with the Chinook Indian Nation on an exhibit for Mariners Hall, which could feature an oceangoing canoe.

“We tell a good story about the immigrants that came here and fished the river and the oceans, but we really haven’t done justice to the subject of the Indigenous people who were here and developed a lot of these things long before Europeans came,” Smith said.

“We’re hoping that our visitors will gain some insights.”

In September, the museum will open an exhibit on Indigenous maritime culture of the Northwest. Images courtesy Seattle Art Museum