Port of Ilwaco.com

Annual Events

• Ilwaco Children’s Parade

Saturday, May 4th • Noon

• Firecracker 5K Run/Walk & Fireworks Show

1st Saturday in July

• Ilwaco Slow Drag

Friday of Rod Run Weekend

• Crab Pot Christmas

First Saturday in December, 12/7

Ilwaco Art Walks

Last Sundays, 1-4pm, May-September

Marine Supply

Englund Marine

Seafood

Safecoast Seafood

Sportsmen’s Cannery

Tre-Fin Foods

Fishing Charters

IllwacoCharterAssociation.com

Beacon Charters

Coho Charters

Pacific Salmon Charters

Seabreeze Charters

Shake-n-Bake Sportsfishing

Shopping

Don Nisbett Art Gallery

Luisa Mack Jewelry & Art

Marie Powell Art Gallery

Purly Shell Fiber Arts

Skywater Gallery

Time Enough Books

Dining

Salt Pub

Waterline Pub

Lodging

Salt Hotel At the Helm

Also at the Port

RiversZen Yoga

Freedom Market

Forest and sea bring people together.

illamook Head drops more than 1,000 feet from the summit of Clark’s Mountain to the Pacific Ocean below.

Our Coast T

Slopes of hemlock and spruce give way to basalt cliffs and then to piles of driftwood. Lewis and Clark were here 200 years ago. Now, people hike in their footsteps, making memories with friends and family.

The Columbia-Pacific region, which continues from the river’s mouth for some distance inland and along the coast, is home to many natural wonders. In its old-growth forests are ferns and fungi. On the shore, shellfish and sea stars cling to rocks. In Astoria, the oldest European settlement west of the Rocky Mountains, there is history around every corner. Yet this place owes its character most to the people who live here.

This edition of Our Coast looks at relationships with the land. These stories are about naturalists, foragers, loggers, historians, crabbers, artists, writers and community builders of this region, who are preserving the past and creating a future for the people and places they care about.

Photographer Lukas Prinos begins with hikers on the Oregon Coast Trail, who start a journey over 363 miles of the state's coastline at the Columbia River South Jetty. At sites along the first 60 miles, Prinos covers varied terrain, as well as hikers’ accommodations, water access and elevation, including the trail’s highest point.

“We Are Still Here,” a collection of photographs by Amiran White, bookends the issue with a powerful message. White began documenting the Chinook Indian Nation, whose members’ ancestors have called these lands home for thousands of years, nearly a decade ago after learning of their ongoing struggle for federal recognition. In these images, she shows ceremonial gatherings, traditional foods and partnerships for the benefit of the land.

Elsewhere, ecologist and author Robert Michael Pyle pens a survey of butterflies who make their home in the ColumbiaPacific over the course of a year.

Some stories focus on camaraderie in the field. Katie Frankowicz of KMUN writes about the community support that emerged after a fire damaged several thousand crab pots in Ilwaco. Meanwhile, Riley Yuan, a Murrow News Fellow with the Chinook Observer, offers narrative insight into modern-day logging.

Astorian reporter Olivia Palmer turns to accessibility, documenting progress toward a coast all can enjoy through projects like Seaside’s wheelchair-accessible beach mats, while also listening for where barriers and gaps remain.

Other stories are about memories. As the Liberty Theatre in Astoria marks its 100th year, people reflect on its role as a center for community life.

Lissa Brewer Editor Our Coast Magazine

The bilingual booklet “Raíces Clatsop” captures stories of heritage.

For my contribution, other than the great fun of painting butterflies, I hiked the Bayocean Peninsula several times and visited with people who remember growing up there before the elements reclaimed what was once imagined as a grand resort.

This

edition of Our Coast looks at relationships with the land, stories about those in this region who are preserving the past and creating a future for the people and places they care about.

I looked through photographs of their reunions, of children who roamed the beach together and continued to foster friendships even after the place they shared was gone.

As I drove there and back, I watched a century-old tree disappear from a sea stack, hit by a windstorm outside Garibaldi.

I called my mother. She remembered the tree, too. We talked until I pulled into Manzanita.

NUMBER 14 • 2025

PUBLISHER

Kari Borgen

EDITOR

Lissa Brewer

PHOTOGRAPHER

Lukas Prinos

DESIGN DIRECTOR/LAYOUT

John D. Bruijn

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Lissa Brewer

Jaime Britton

David Campiche

William Dean

Mike Francis

Katie Frankowicz

Ryan Hume

Peter Korchnak

Rebecca Lexa

Marianne Monson

Olivia Palmer

Robert Michael Pyle

Amiran White

Riley Yuan

ADVERTISING SALES MANAGER

Sarah Silver

ADVERTISING SALES

Heather Jenson

Hattie Sheldon

Inside Our Coast Magazine

GET CONNECTED

Interact with us and the community at DiscoverOurCoast.com

FOLLOW US facebook.com/ourcoast instagram.com/ourcoast

EMAIL TO US editor@discoverourcoast.com

WRITE TO US P.O. Box 210 Astoria, OR 97103

VISIT US ONLINE DiscoverOurCoast.com offers all the content of Our Coast Magazine and more.

FIND BACK ISSUES

Read up on back issues of Our Coast Magazine at DiscoverOurCoast.com

Our Coast is published annually by The Astorian and Chinook Observer. DailyAstorian.com • ChinookObserver.com

Copyright © 2025 Our Coast Magazine

MEET the CONTRIBUTORS

Lissa Brewer

Lissa Brewer is the editor of Our Coast Magazine and associate editor of The Astorian. She grew up hiking and beachcombing on the shores of Puget Sound and now lives in Astoria, where she writes about, photographs and illustrates life along the Columbia River and Pacific Coast.

Lukas Prinos

Lukas Prinos is the photographer of Our Coast and multimedia journalist at The Astorian. He first learned about cameras while exploring the Cascade Mountains in his childhood. After graduating from the University of Montana, he moved to Astoria, where he has enjoyed photographing the outdoors.

Amiran White

Born and raised in the United Kingdom, Amiran White began her photojournalism career stringing for The Associated Press in Portland. She spent 10 years as a staff photographer at newspapers in Oregon, Pennsylvania and New Mexico, and has received several awards for her documentary work, including the Golden Light Award and a nomination for the Pulitzer Prize.

John Bruijn

John Bruijn is the production director at The Astorian and has been with the Media Group for 25 years. He is the design director of Our Coast Magazine and does layout and design work of several visitor guides and publications.

Olivia Palmer

Olivia Palmer is a reporter covering local government and the environment for The Astorian. A graduate of Western Washington University, she now calls Astoria home. Olivia enjoys trail running, mountain biking and exploring the coast’s many beaches.

David Campiche

David Campiche is a potter, artist, poet, retired owner of the Shelburne Hotel in Seaview and author of the recent novel “Black Wing.” He is a lifelong resident of the Long Beach Peninsula who has contributed to The Astorian and the Chinook Observer over a couple of decades.

Ryan Hume

Ryan Hume is a freelance writer and editor who has been contributing to Coast Weekend and Our Coast for a number of years. He lives in Astoria and takes full advantage of the vibrant literary, arts and culinary happenings the North Coast offers.

Riley Yuan

Riley Yuan is a Chinese American writer and photographer and a Murrow News Fellow with the Chinook Observer. Prior to becoming a journalist, he fought wildfires with the Stanislaus and Baker River Hotshots, served as a Peace Corps volunteer in West Timor, Indonesia, and taught high school English in Hawaii and Vermont.

Marianne

Monson

Marianne Monson is the founder and president of The Writer’s Guild in Astoria and has authored several books about women’s history. Her titles include “Frontier Grit,” “Women of the Blue and Gray” and “The Opera Sisters.”

Katie Frankowicz

Katie Frankowicz is the news director at KMUN in Astoria. She has worked as a journalist on Oregon's North Coast and in southwest Washington for more than a decade, covering commercial fisheries, the environment, city government and whatever else comes up.

Robert Michael Pyle

Dr. Robert Michael “Bob” Pyle is a biologist, essayist, novelist and poet who has dwelled in deepest Wahkiakum County for 46 years. His books “Wintergreen,” “Sky Time in Gray's River” and “Where Bigfoot Walks” are Northwest classics. For his worldwide work in butterfly study and conservation, he was made a Life Fellow of the Royal and American Entomological Societies.

Jamie Britton

Jaime Britton is the acting director of the Lower Columbia Preservation Society in Astoria, where she specializes in education and resources about historic homes and buildings in the region. She loves finding connections between people and places to share their untold stories.

more CONTRIBUTORS

Peter Korchnak

Peter Korchnak is a regular contributor to Coast Weekend and The Astorian. He is from Czechoslovakia, a country that no longer exists. When he’s not writing, he explores the memory of another in the podcast “Remembering Yugoslavia.”

Mike Francis

Mike Francis is a longtime Oregon journalist who has extensively covered military and veterans issues. He serves on the Astoria Planning Commission and resides on the South Slope.

William Dean

William Dean is a retired investigative journalist who left newspaper work to take on the new challenge of writing novels. Since moving to Astoria, he’s published three suspenseful tales set in the Pacific Northwest and also writes about the local craft brewing scene.

Rebecca Lexa

A naturalist, educator, writer and tour guide living in the Pacific Northwest, Rebecca Lexa connects people with the natural world. Her forthcoming book, “The Everyday Naturalist: How to Identify Animals, Plants, and Fungi Wherever You Go,” will be published by Ten Speed Press in June 2025.

Clatsop

Skilled Nursing Facility

Short-term & long-term rehabilitation.

Clatsop Care Retirement Village

Assisted Living Facility

Studio, 1 & 2 bedroom units available.

Memory Community

Living community with 3 separate garden areas, dining and activities.

In-Home Services

Available 24 hours, 7 days/week

503.325.0313

info@clatsopcare.org 646 16th St., Astoria, OR www.clatsopcare.org

Do & See

Columbia-Pacific butterflies

Accessible recreation

‘The Goonies’ turns 40

Our Picks Do & See

Wings Over Willapa

By Lissa Brewer

One by one, hikers stepped off the metal barge, peeled away their life jackets and set out, supplied with backpacks and walking sticks, on a 6-mile round trip up the center of Long Island, a lush and wild corner of the Willapa National Wildlife Refuge accessible only by boat.

Their destination was the Don Bonker Cedar Grove, a towering stand of 1,000-year-old western red cedar trees, and one of the last remaining patches of old-growth forest in this part of Washington state. Most people get there by kayak. For those staying the night, the island is dotted with 20 tent campsites in five locations.

But this trip was for an afternoon. It’s a signature event of Wings Over Willapa, a weekend of birding and nature immersion organized by the Friends of Willapa National Wildlife Refuge, and one of only a few such opportunities to visit the island.

The three-day festival is timed each year to align with the peak of the fall migration season along the Pacific Flyway, typically in late September, when millions of birds travel south between Alaska and Patagonia, stopping by the pristine waters of Willapa Bay.

In 2024, Wings Over Willapa offered nearly two dozen events. Kyle Smith, a forest manager with The Nature Conservancy in Washington, led hikers through the 7,600-acre Ellsworth Creek Preserve near Teal Slough, where the conservancy and refuge have formed a partnership to restore habitat for salmon, black bear, cougar and elk.

Nearby, the Port Townsend, Washington, based Discovery Bay Wild Bird Rescue brought live owls, hawks and falcons to greet visitors. Naturalists also took to parks and sloughs for early-morning bird hikes, authors prepared talks and kids enjoyed wildlife-themed crafts.

On Long Island, sunlight filters through the forest canopy onto soft beds of moss and fern. Coral mushrooms sprout below the trees. And between the push and pull of the tides, you may just find yourself alone with a song sparrow, humming a tune from a wooden post.

Hoffman Center for the Arts

By Marianne Monson

When Myrtle and Lloyd Hoffman, a musician and a painter, left their home, property and modest savings to the coastal community of Manzanita after their deaths in 2004, it was a first step in establishing a local center for arts and culture.

More than 20 years later, the Hoffman Center for the Arts offers a gallery and performance space, clay studio and sculpture garden. The place is envisioned as a home for artists, writers and horticulture enthusiasts, where people of all ages and backgrounds are invited to connect through creativity.

The center is run by a nonprofit board of 12, numerous volunteers and by executive director India Downes-Le Guin, who brings a background in creative writing and arts programming.

Classes offered range from life drawing to basket weaving, with scholarships available. In the gallery is a rotating cast of work by artists with ties to the North Coast. Exhibits are typically displayed for a month and may include paintings, photographs, collages, ceramics and textiles.

For writers, the center awards the annual Neahkahnie Mountain Poetry Prize. The North Coast Squid, its literary journal, is published in odd years. Even years see the Word & Image project, pairing visual artists with writers to respond to each other’s work. The resulting creations are displayed on gallery walls and printed in a keepsake book.

A clay studio features five electric wheels, two slab rollers, a glaze room and two electric kilns. Courses are offered for beginning to advanced potters, with kiln services also available. Outside in the Wonder Garden, volunteer horticulturalists work with native plants. The garden is also a meditative space for people to sketch or write, and poetry is regularly sought for display.

Whether you consider yourself a writer, a visual artist, an art enthusiast, or a beginner on your creative journey, this is a place to build upon an interest or explore something entirely new.

Long Beach Peninsula

Manzanita

Artistry. Outdoors. Adventures.

Banks-Vernonia State Trail

By Rebecca Lexa

Over 21 miles between two quiet towns in the foothills of the Oregon Coast Range, hikers, cyclists and equestrians share a trail where a railroad bed once opened up stands of Douglas fir and cedar to lumber-hauling trains.

Banks-Vernonia Trail, which was recently designated a National Recreation Trail, was Oregon’s first “rails-to-trails” park, part of a growing movement that promotes turning abandoned or otherwise unused railroad beds into multi-use recreation areas.

The railroad line was in use through the early 20th century until it was abandoned in 1973. Oregon State Parks later took over the right of way and, with encouragement from local trail enthusiasts, began converting the former railroad bed in the early 1990s. Last year, it was designated a National Recreation Trail.

Most of the route is graded, though there are some slopes along the way, and it gains about 1,000 feet of elevation in the 7 miles between Manning and Tophill. The main trail is 8 feet wide and paved, but there are also gravel sections that are easier for horses, such as the alternate route at Buxton Trestle. Well-maintained trailheads include accessible entry points, and most have restrooms. Leashed dogs are also welcome.

The trail wanders through forests of varying ages, from fresh clearcuts to mixed conifer and maple. Now and then, the route may be punctuated by fall fungi or an old apple tree, linking the area to an agricultural history. As it parallels Highway 47, traffic noise is a constant, but this doesn’t prevent ample birding opportunities, including where the route follows or crosses the Nehalem River.

Banks-Vernonia is the northernmost section of the Tualatin Valley Scenic Bikeway, a 50-mile route that starts at Rood Bridge Park in Hillsboro and ends at Vernonia Lake City Park. For an extended ride, cyclists can commute a few miles up the highway to Pittsburg onto the Crown-Zellerbach Trail, another railroadturned-National Rail Trail that stretches to Scappoose.

Trail use is largely limited to daylight hours, so plan accordingly, and keep in mind that both trails have bike repair stations along the way.

FisherPoets Gathering

By David Campiche

As spectacular as an ocean storm itself, the annual FisherPoets Gathering blows into Astoria on the last weekend in February, gathering people of the commercial fishing industry for a weekend of poetry, music and salty storytelling.

Big water and back-breaking work are part and parcel of these dangerous professions, whether fishing for Dungeness crab, Chinook salmon or winching up a 200-pound halibut from the bottom of the sea.

Those who read share their love of the big water, fishing and the dangers of the Pacific Ocean with skill, humor and delight. And if sometimes there is an element of pain or danger in their offerings, listen carefully as they express their souls. Their travails are the stuff of big hearts and solid fortitude.

Fishermen display their deepest feelings with self-effacing modesty. Time and tides support the legacy. Discipline has shaped these hearty men and women of the sea. Certainly, Mother Nature can swing with a hard fist, only to lay down hours later, softly as the flutter of a seabird’s wings.

Each year, crowds wrangle over who wears the poet’s crown. Everyone has a favorite. Crowd-pleasers like Dave Densmore and Geno Leech draw gasps, foot-stomping and laughter, year after year. But there are so many. This gathering fills the town, with readings at theaters, breweries and bars, plus music and art. Fighting storms on the water from Cape Disappointment to the Bering Sea, one forms alliances.

Then there are the nights on a placid sea when the sun sets like golden thunder and, at that very moment, none on the water would trade their lifestyle for riches or hard cash. These poets will tell you stories in heart-futtering detail. They will laugh and hoot, blush and cry. You will, too.

Come listen when the clouds open over Astoria and you expect nothing from the readers but the pride in their voices, or just maybe, comradeship over a good beer. This is a proud and talented bunch.

Banks-Vernonia

Astoria

Do & See

Butterflies OF THE COLUMBIA COAST

Let it be said from the outset that we privileged ones who dwell near the mouth of the Columbia River, on either side and for some distance inland, do not occupy butterfly nirvana. If you have been under the impression that the rainforests of the world are populated by scads of beauteous butterflies, then revise your view slightly: this is true of tropical rainforests — but not temperate rainforests.

Butterflies tend to do very well, in both abundance and diversity, under conditions that are hot and wet (the tropics), hot and dry (the desert) and cold and dry (the Arctic). Cool and wet, not so much. And those are the conditions that prevail here, in our beloved temperate rainforest. The persistent rain and heavy forest cover tend to discourage these sun-loving insects, whose immature stages are likely to rot in the wintertime. Our diversity is better expressed in ferns, mosses, mushrooms, conifers and other organisms that thrive under cool, shaded, moist conditions, or else migrate. So the butterflies here are subtle, compared to elsewhere.

That said, a modest array of species from across the spectrum of butterfly families has adapted well to the plants and climate of the lower Columbia, and they do very well here. Happily, many of these are both beautiful and fascinating, and may be found with moderate searching and attention to the landscape. So we are not at a loss for butterflies here, even if there are far fewer than we might find in the Cascades, Olympics, or Willamette Valley and points south to the Siskiyou and beyond.

Here I will acquaint you with a number of butterflies that you might well encounter here along Our Coast and its adjacent inland areas, and give some tips as to how you might go about spotting them. Since butterflies have different life histories and particular emergence times, it might be best to do this by running through the butterfly year along the Columbia Coast.

Butterflies tend to do very well, in both abundance and diversity, under conditions that are hot and wet (the tropics), hot and dry (the desert) and cold and dry (the Arctic). Cool and wet, not so much. And those are the conditions that prevail here, in our beloved temperate rainforest.

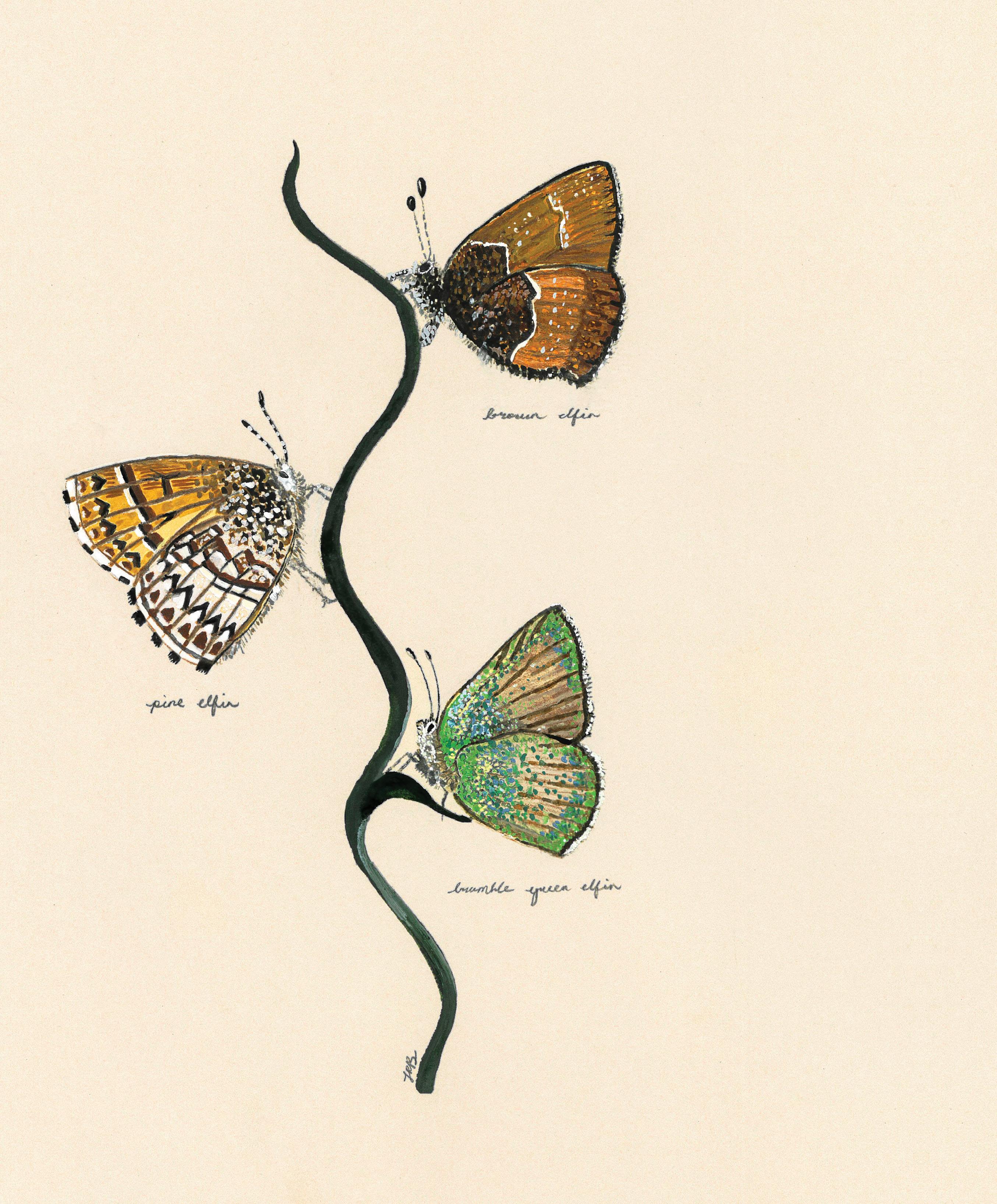

Words: Robert Michael Pyle • Illustrations: Lissa Brewer

As winter turns toward spring, with hazel catkins bursting and pussy willows not far behind, the very first butterflies of the year are posed to emerge — not from their chrysalis, but from a hollow tree, shed or other shelter. Eight Northwest butterflies overwinter as adults, and may be seen on the wing even in January or February, or certainly in March, when the sun is allowed to shine enough to warm the air and bring out these hibernators. Around here, the most likely ones to see are mourning cloaks, California tortoiseshells, satyr anglewings and green commas. Watch for these sizable, often rustycolored butterflies taking their hungry sustenance at sapsucker holes or pussy willows. They may look tatty after their long winter in-dwelling, but their bright offspring will appear again in the fall.

Usually the first fresh emerger to pop out of its pupa is the echo azure, related to the eastern spring azure, which Robert Frost described as “sky-flakes/down in flurry on flurry.” Members of the gossamer-winged family, the blues, coppers and hairstreaks, azures are a lovely lilac-blue on the upper side, silvery white below. Their caterpillars feed on flower buds of many kinds of shrubs, especially osier dogwood, ocean spray and ninebark around here. The adults visit early flowers such as sweet coltsfoot, and the males collect on sandy riverbanks and muddy logging roads to sip salts from the soil. So when you spy bright blue fliers on early spring days, your eyes are not playing tricks on you.

These increasingly rare warm and sunny spring days may also reveal relatives of the azures called elfins. The tiny, chestnut-and-mauve brown elfin haunts kinnikinnick and salal in seaside woods, while the (actually pine-feeding) pine elfin patrols shore pines among beach dunes at Leadbetter Point and Fort Stevens, and the bramble green elfin seeks out rosy lotus flowers higher in the Oregon Coast Range. All of these are thumbnail-sized, as is our earliest skipper — the buzzy gray two-banded checkered skipper, which lays its eggs on flowers of big-flowered geum and trailing blackberry in woodland glades and roadsides.

Eight Northwest butterflies overwinter as adults, and may be seen on the wing even in January or February, or certainly in March, when the sun is allowed to shine enough to warm the air and bring out these hibernators.

In April, the forest and rural roads begin to be spattered by lots of margined whites floating along like bits of tissue paper. These nearly pure-white butterflies with darker veins beneath favor the flowers of ladies' smocks (Dentaria or Cardamine) on which to lay their eggs, like most of the whites requiring hosts in the mustard family. They are native to our temperate rainforest and very well adapted to it, doing well in clearings among both old-growth and managed forests, if not sprayed. But when you leave the wilder places for the towns and gardens, the species of white shifts from margined to European cabbage white. This familiar butterfly, introduced into Quebec in 1861, covered the whole continent extremely successfully, feeding as larvae on cabbages, broccoli and other crucifers. It is by far the commonest species in Astoria, flying from spring through fall in successive generations. I love it, as it is often the only butterfly to be seen on a sunny day in town or farmland.

The late spring brings some real warmth, and with it the tide of swallowtails. The first to mention is another white butterfly, but bigger and floppier than the actual whites. This is the Clodius parnassian. Though classed as a swallowtail by morphology and DNA, it looks nothing like the others. It is a biggish, rounded butterfly of waxen white with sharp inky-black and cherry-red spots. Its caterpillars feed on wild bleeding heart, so you can spot it floating along many a woodside road or path all summer long. Usually by May Day or so, the more obvious true swallowtails will be out too. We are graced with three species here: the pale tiger swallowtail, first out, often in time to nectar on your lilac bushes. It is quite whitish too, banded in thick, black tiger-stripes. A week or two later come the western tigers, lemon-yellow with narrower black tiger-stripes. Both of these feed on broad-leaved trees like willows, cherries, red alder and cascara, and can be truly abundant when conditions are right, even in the city. (Many people call them monarchs, which do not occur here because of the absence of milkweed.) Our final species of the family, the anise swallowtail, has two distinct broods, in spring and late summer to fall. It sports yellow bands across black wings and it lays its eggs on seaside angelica, cow parsnip, dill, parsley and other members of the carrot family. Look for them on lilacs in the spring and butterfly bushes in August, and along headlands, breeding almost down to tidewater at Leadbetter Point.

Do & See

As spring goes on, watch for western meadow fritillaries in the forest clearings. Like all fritillaries, they feed on violets. When they fly, their brilliant orange, black-dotted wings, and their violet-and-rust undersides when at rest, leave little question of their identity. Another softer orange small one — actually Dreamsicle-colored — may be seen haunting the backbeach grasses on the Oregon side about this time. Known as the ochre ringlet, it is often seen tucked up under spiderwebs beneath Queen Anne's lace along seaside dunes. The related large wood nymph may be spotted flip-flopping through pasturelands and woodedges some distance inland from the shore. The males are dark chocolate and the females cocoa, each with conspicuous eye-spots on the wings to draw birds' attention away from their bodies. Both ringlets and wood nymphs feed on grasses as green, camouflaged caterpillars.

Summertime sees the flights of several colorful members of the brush-footed family. A common resident of towns, countryside and anywhere with willows and ocean spray, the very handsome Lorquin's admiral soars back and forth between occasional flaps. Flying out from a chosen branch, males patrol particular territories where they are most likely to encounter females. Jet-black with broad white bands and cinnamon wing tips, they are unmistakable and unforgettable. Another butterfly commonly called an admiral, the red admiral (or red admirable), is not closely related. It too is black, but its wing bands are scarlet or fire-engine orange, not white. Look closely and you will see its resemblance to the several species of ladies — painted lady, West Coast lady and American lady, each with salmon or citrus-orange wings with distinctive black, tan and white variegations. All three species fly into our area in the summer from farther south, so their numbers are highly irregular and their appearance unpredictable year to year. They especially love to nectar on zinnias and butterfly bushes.

A much-smaller brush-foot appears sparsely in spring but much more abundantly in its summer generation. This is the bright orange-and-black spackled mylitta crescent. A mother-of-pearl crescentspot at the outer edge of the underside of the hindwing gives its group the name "crescents." The brighter orange males, just an inch across, glide and flap, glide and flap, close to the ground, patrolling roadsides, edges of rutted tracks or fields and country lanes, all through late summer into fall. The slightly bigger females are a duller orange. They spend their time visiting flowers and seeking their host plants to lay eggs. They feed exclusively on thistles — native or introduced. So if you do not have a compelling reason to eliminate thistles, by all means keep them around, because they are also the caterpillar host for painted ladies and a favorite nectar source of swallowtails, fritillaries and others.

Another tiny flier of summer is the purplish copper. You will find it in damp spots or waste areas in fields where pink knotweed or smartweed grows (not the big Japanese knotweed). Females are orange- and black-spotted, while the males are tarnished-penny brown with an extraordinary purple sheen when seen in the right light. They occur through much of our area, though seldom commonly unless you come upon a good big knotweed patch.

One other, very special species of copper can be claimed by the Columbia Coast, but it is very rare and few have seen it. A newly described subspecies of the mariposa copper (more common in the Cascades), it is known as June's copper. Found at Ilwaco in 1918 and never since on the Long Beach Peninsula, it was discovered among the Gearhart Fen Complex in recent years by local naturalist Mike Patterson. Efforts to find more and to protect their fen-cranberry bog habitats are underway. The uncommon, sedge-feeding dun skipper may be spotted here as well.

Which brings us to late summer, and the most famous of our Columbia Coast butterflies, the Oregon silverspot. This silver-dollar sized, silver-spotted brush-foot was first found near Ocean Park in the nineteen-teens by early lepidopterist Agnes Veazey. After many years of its anonymity, I found it again near Lake Loomis in 1975. The butterflies' federal listing as a threatened species was one of the Portland-based Xerces Society's first campaigns, nearly 50 years ago. Since then, despite lots of monitoring and habitat conservation efforts, it has dropped out of Washington and persists only in a few Oregon coastal remnants of the old, native-fire dependent salt-spray meadows and Mount Hebo. Recently, it was introduced to Saddle Mountain, and the hope is to reintroduce it to restored Washington habitats in coming years. One colony, at Cascade Head Preserve north of Lincoln City, survived thanks to the nectar of the despised exotic weed tansy ragwort, until native nectar sources were reestablished.

Shifting now from rare to common species, there is no more widespread or successful butterfly along the Columbia Coast (and indeed throughout the region) than the woodland skipper. There are many species of grass-feeding little skippers of tawny coloration and rapid flight, but most of them fly in spring and in specialized habitats outside our purview. This one emerges in late summer, in almost every open, sunny habitat available. Many people know them in their gardens, zipping around among herbs, asters and many other flowers. They seem like familiar neighbors or garden sprites. Their orangey-gold wings marked with black dashes are short and triangular, and their bodies thick with powerful flight muscles. Try to get a peek at their confiding and, frankly, cute faces, with their big eyes, short antennae and furry palpi. They thrive on many kinds of grasses, native and nonnative, so long as they are not cut too short and never, ever sprayed. Woodland skippers, prolific everywhere but deep woodland, are on the wing from Aug. 1 to Oct 1.

As summer wanes, two members of the whites and sulphurs family may appear, one of each. First, only among the shore pines at the beach, seek out the ghostly, lovely pine white. You may see them floating about the tops of the pines or Douglas firs, whose needles their exquisitely cryptic larvae consume; or they may come down to nectar on the flowers of hawkbit, late-blooming wild strawberry or garden lobelias, among others, especially in the mornings and later afternoons. The males are milky white with crisp and narrow black veins and black-chained tips. The females are more lineny, with smudgy black veins, and very striking crimson markings below. How lucky we are to have two of the few pine-feeding butterflies right here, both very beautiful — the western pine elfins in spring, and the pine whites in late summer into early autumn. Head out the piney strip behind the sea and dunes, and try to see them both.

To find ways to help with butterfly and pollinator conservation visit www.xerces.com

To identify and get to know all of the butterflies of our Columbia Coast and surrounding regions

Pick up a copy of the Timber Press book, “Butterflies of the Pacific Northwest” by Robert Michael Pyle and Caitlin C. LaBar from one of our local booksellers.

Meanwhile, the orange sulphur (or alfalfa butterfly) shows up from the east side and the Cascades some summers — just a few, or in certain years, hundreds or thousands, laying their eggs on red clover for one final generation. They last as long as the weather permits — I saw one big female here in Gray's River on Thanksgiving one year — and then die back until next year's recruitment. Seek them in hayfields and pastures, and be prepared for shocking oranges.

Finally, the last warm days of autumn see the fresh new tortoiseshells and anglewings flitting about in search of late nectar or rotting fruit to tank up on prior to their long winter hibernations. The bright satyr anglewings will be seen especially near nettle patches. In fact, three of our loveliest common butterflies depend entirely upon stinging nettles for their caterpillars' development: the satyr anglewing, the red admiral and Milbert's tortoiseshell. Nettles are the sine qua non for these spectacular residents. The caterpillars of California tortoiseshells, however, feed on buckthorns, mountain balm and mountain lilacs in the Cascades. Adults move down into western counties in late summer, having defoliated their hosts. Sometimes they breed here on ornamental Ceanothus or maybe Cascara, and some years they build to such numbers that Patterson has seen them migrating south along the seawalls and shorelines. It is not uncommon, but always delightful, to find one overwintering in one's woodshed or cellar. But the finest sight of autumn butterflying might be to witness a bright, fresh mourning cloak basking or nectaring on mums or asters before turning in for the winter — all dark chocolate, French vanilla and blueberries, a butterfly for the ages, wherever you see it.

I hope this little excursion through the year with our local butterflies might encourage readers to seek out this rainbow resource for themselves. In order to optimize your butterfly-spotting opportunities, follow these simple rules: visit open, flowery, sunny places with your eyes wide open. Grow all the food and nectar plants you can in your garden or spare land or flowerbox for butterflies and other pollinators. Make sure the plants you buy have not been pretreated with neonicotinoid pesticides, and never, ever spray these or other butterfly-toxic products yourself. Happy butterflying!

On the Oregon Coast Trail

A photo essay by Lukas Prinos

The journey begins

Evening light hits the observation tower at the Columbia River South Jetty, where the Oregon Coast Trail unfolds into the mist. The trail follows Oregon’s 363-mile coastline south to Brookings. Hikers typically set out from the north.

According to the United States Census Bureau, around 15% of Oregonians have some type of disability, and around 7% have a mobility-related disability. Despite that, many still face barriers to accessing the trails, parks and beaches that draw swaths of visitors to the coast.

an accessible COAST

Moving the needle on recreation for all

For Tom Sayre, a typical bike route spans at least 20 miles.

On most rides, Sayre hits the pavement in his neighborhood before dropping down to Skipanon River Park to pick up the Warrenton Waterfront Trail. From there, he takes in sweeping views of the Columbia River, passing through Carruthers and Seafarers' parks and on to the trails at Fort Stevens. Often, he’ll stop by the ocean before looping past Coffenbury Lake to return home.

In this corner of the North Oregon Coast, the rides are sometimes sunny, sometimes soggy, but always keep him coming back for more.

“I mean, where else can you ride 20 miles and ride through forests, along a big river, see the ocean, stop at a lake?” Sayre said. “I don't know, that's probably one of the best routes you could ask for.”

There’s more at play than picturesque views, though.

Sayre broke his back decades ago, and has used a wheelchair ever since. It wasn’t until after college that he discovered handcycling, a sport where riders use their hands, rather than their feet, to pedal. These days, he gets out once or twice every week on a custom-made, three-wheeled handcycle.

Sayre has been advocating for increased accessibility in outdoor recreation for the past 35 years — and in some ways, that type of advocacy has paid off: a few dozen years ago, even an accessible outdoor restroom might have been hard to come by. Now, more and more ADA-compliant facilities and adaptive gear suppliers are dotting the map. But the work is far from complete.

According to the United States Census Bureau, around 15% of Oregonians have some type of disability, and around 7% have a mobility-related disability. Despite that, many still face barriers to accessing the trails, parks and beaches that draw swaths of visitors to the coast each year. Gradually, cities, agencies and individuals across the state are taking steps to move the needle.

Words: Olivia Palmer • Images: Lukas Prinos

Left: Tom Sayre speeds along the Warrenton Waterfront Trail. With a handcycle, he can access a variety of terrain for a ride, including grass and gravel.

A tug passes by along the Warrenton Waterfront Trail.

Addressing barriers

When Sayre gets out on his handcycle, it’s an escape from the ordinary.

“It’s a rare occurrence that somebody that's in a wheelchair, underneath their own speed, can go fast enough to feel the wind blow through their hair, their eyes water,” he said.

There’s a wealth of places nearby to make that escape, too — among his favorites, the Astoria Riverwalk, the Banks-Vernonia Trail, the Discovery Trail and the winding paths of Fort Stevens State Park. On slower days, when he feels like getting farther from the crowds, he might go with his family to the Willapa National Wildlife Refuge, Cedar Wetlands Preserve, Kilchis Point Reserve or Cascade Head Preserve.

Still, there are other places Sayre can’t get to. On a recent ride, he pulled up to a trail off of Perkins Road at the edge of Lewis and Clark National Historical Park. It’s one he might have kept going on, except for an obvious obstacle: a brown metal gate, stretching from one side of the entrance to the other

Sayre calls this kind of physical barrier a showstopper — and for good reason. Although hikers and dog walkers can usually slip through the space between a gate and the edge of a trail, someone using a mobility device often can’t.

He doesn’t have to look far to find similar issues nearby.

Off an overlook along the Fort to Sea Trail, a set of boulders stands as an impassible barrier. In Warrenton, gates cut off access to much of the Airport Dike Trail. Sayre said he can name plenty of other examples.

Part of the issue comes down to funding — if cities and parks have limited budgets, they can’t always prioritize addressing outdated infrastructure. They also need to consider trail maintenance. Physical barriers like gates are often used to keep all-terrain vehicles and cars out.

“I understand that, and that's a good thing that they're protecting our park like that, but you can't block out a whole population because of that issue,” Sayre said. “You’ve got to manage it a different way.”

There’s a wealth of places nearby to make an escape, too — some of Tom Sayre's favorites are the Astoria Riverwalk, the Banks-Vernonia Trail, the Discovery Trail

and

the winding paths of Fort Stevens State Park.

Sayre has served on dozens of boards and citizen advisory committees, including with the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department, which released its first-ever accessibility design standards for all future projects in 2023.

Other agencies have made similar efforts. In 2020, for example, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park completed an accessibility self-evaluation and transition plan to document barriers and make recommendations for improvements. The Oregon Coast Visitors Association, on the other hand, is working with partners to increase accessibility along the coast through the Oregon Coast Travelability Group.

Laws like the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Architectural Barriers Act provide important standards for that kind of work — but Oregon Coast Visitors Association deputy director Arica Sears said she’s learned they’re often just a starting point.

“Accessibility is a lot more than that, because there are a wide range of disabilities, cognitive and physical,” Sears said. “So I think it's an important conversation when anybody is looking to improve, especially outdoor recreation, that maybe the kayak launch is ADA accessible, it passes that law, but is the parking lot to get to it? Is the bathroom at the parking lot accessible? And if those answers are no, then really that kayak launch is not accessible to disabled people.”

To Sayre, accessibility starts with how people get to a park or recreational facility, like whether there is accessible parking, or whether there are accessible public transit stops and accessible routes to the entrance. From there, he looks at signage, taking note of whether signs include accessibility symbols and adequate information on slope, cross slope and ground treatment that might exceed expectations. Accessible trails will be wide and shallow enough for a variety of users, and have a firm, even and continuous trail surface that connects to other trails and amenities.

The list goes on — but before he even gets to a facility, Sayre wants to know what to expect, and how to prepare. Having detailed information online about trails, parking and amenities goes a long way.

“When you spend a lot of time in the outdoors, you realize that there's a whole bunch of barriers that are going to try to keep you from recreating, right?” he said. “And after experiencing it over and over and over again, you start to think, ‘How can I find out information before I go, getting all the gear put in the rig, driving out to somewhere and getting out and finding out there's a barrier, you know, right at the entrance?’”

A handcycle is a type of bicycle powered by the rider’s arms.

Tom Sayre gazes out over the Columbia River at sunset.

Do & See

Accessing the beach

From the sandy shores below Haystack Rock to the tide pools of Oswald West State Park, the Oregon Coast is incomplete without its beaches. But as Sayre knows, beaches often don't bode well for wheelchairs, especially when there’s dry sand. For him, most outings include parking on the beach, finding a spot to sit, and watching as his family plays and walks around.

For families like April Foster’s, beach access mats have opened a door to something more.

Foster has been visiting the coast for years with her daughter, Eilish, who uses a wheelchair. When Eilish was younger, she would carry her to the beach, but with time, that became less and less practical.

For at least a decade, Eilish stopped going to the beach, settling instead for views from the road or the parking lot.

“It became like scoping out where we could park and watch versus participate,” Foster said. “And especially during COVID, when I moved to Manzanita, I was like, ‘It's really sad that we live, like, four blocks from the beach and we can't get on the beach at all.’”

Then, in September 2022, April and Eilish visited Lincoln City for its first season rolling out hundreds of feet of Mobi-mats at local beach sites.

Foster remembers the spark of excitement that flickered as she watched an elderly couple make their way up the mats, one in a wheelchair. She wasn’t sure how long they’d been out on the beach, or what they’d been up to, but she could sense how palpable their joy was.

As she pushed Eilish along the blue plastic mat, the same feeling washed over them.

“I was like, ‘We get to touch sand, we get to feel that salt air. We just get to hang out, you know, and be around other people who are enjoying the beach,’” Foster said. “And that was so nice, and that's what I hope for every beach community, is for people like Eilish to be able to get down, to be with their family, be with friends, to go have a picnic, whatever it may be.”

Since Lincoln City’s roll-out, the City of Seaside has also added over 1,000 feet of Mobi-mats to two of its beach access points — one off 12th Avenue and the other off Avenue U. Now, when April and Eilish are in town, they often make a stop by the water, sometimes continuing along the promenade for a longer walk with ocean views.

The mats aren’t just for wheelchairs, though. Joshua Heineman, Seaside’s director of tourism marketing, said he often sees families with strollers and wagons, visitors with canes and other beachgoers use them, too. “It's been surprising how much it's used actually,” Heineman said. “I mean, even I am somebody who likes walking in the sand, but there's just something about when you see that road laid out in front of you. You just gravitate towards it.”

Seaside and other cities along the coast also offer free beach wheelchair and track chair rentals. Meanwhile, the Oregon Coast Visitors Association has created a Mobi-mat toolkit to help provide jurisdictions with practical resources for creating a project plan, securing funding and permits and implementing a Mobi-mat program.

Of course, for as many feet of mats extend along the beach, miles of shoreline elsewhere remain inaccessible. Many cities only keep their mats out during the summer months, and those that keep them out for longer can face challenges during events like the king tides. Sayre worries the mats could create an obstacle for vehicles on the beach.

Still, they offer one experience that otherwise might be out of reach — and for Foster, that’s no small thing.

“Obviously there's limitations, but to have an opportunity to experience it, I think, is pretty special,” she said.

Seaside and other cities along the coast offer free beach wheelchair and track chair rentals. Meanwhile, the Oregon Coast Visitors Association has created a toolkit to help provide resources for Mobi-mat programs.

Seaside has installed mats that can extend up to 1,600 feet depending on tides and ocean conditions.

Centering community voices

Efforts to increase accessibility extend beyond the coast’s beaches. At Westport County Park, an ADA-compliant boat ramp and kayak launch recently won Clatsop County a national award from the States Organization for Boating Access. At state parks like Cape Lookout and Nehalem Bay, accessibility improvements are underway thanks to the support of a general obligation bond.

But without the input of people with lived experience, those types of efforts can miss the mark.

“That advocacy is really important,” Sayre said, “and if you don't have a seat at the table, it's much harder to make the change.”

That isn’t lost on groups like the Oregon Coast Visitors Association and the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department. Helena Kesch, the department’s ADA and tribal relations coordinator, said working with people from the disability community has played an essential role in informing work like the agency's accessibility design standards.

Eilish Foster, left, and her mother, April Foster, greet a dog at the beach in Seaside.

A gate stands in the way of a National Park Service path off Perkins Road. The gate has an access point on the side that cannot be navigated by a wheelchair or handcycle.

“Sometimes, if you're not working with people with lived experience, you don't know and you're making assumptions,” Kesch said. “So it's really important to engage with people with lived experience in the project design and planning phase, even at conception, because there's things that you just don't think about when you're not a person with a disability.”

The Oregon Parks and Recreation Department’s new standards aren’t all-encompassing, though. Rather, they’re a starting point to continue to add to and improve upon. The reality is, increasing accessibility is less of a box to check off and more of an ongoing process of listening, noticing and taking action.

More than anything, Sayre wants to see more people with disabilities communicating their needs to their local jurisdictions — and not just informing accessibility work, but leading it.

“I think that you have to have that population representing themselves and not somebody else representing for you, because while they might be really well-informed, they're not living the life,” Sayre said. “I'm getting older, and I'm not going to be doing this for much longer, and I had hoped that there would be, you know, 10 people that could take my place, or 20 people that could take my place.”

That kind of involvement, he added, allows for a proactive approach to problemsolving — and a more accessible coast for all.

Efforts to increase accessibility extend beyond the coast’s beaches. At Westport County Park, an ADA-compliant boat ramp and kayak launch recently won Clatsop County a national award from the States Organization for Boating Access. At state parks like Cape Lookout and Nehalem Bay, accessibility improvements are underway.

Miles of sand

Fishermen gather at Fort Stevens State Park. The first 16 miles of the Oregon Coast Trail follow a flat, wide beach past the Peter Iredale shipwreck until an inland turn at Gearhart.

Coho salmon

Fishing grounds

Larry Smith inspects a coho salmon in his cooler

From left, longtime friends Larry Smith, B.K. Srinivasan and Al Onkka share a laugh while they wait for the fish to bite.

The Oregon Film Museum in Astoria, where cardboard cutouts of characters from “The Goonies” line the halls.

Do & See

‘It’s our time’ “The Goonies” is turning 40.

This year, the best-known Hollywood production filmed in Astoria will celebrate four decades since its June 7, 1985, release, and fans from around the world are expected to shuffle in for a weekend of special events celebrating the cult classic.

Words: Peter Korchnak • Images: Lukas Prinos

Held over four days, from June 5 to June 8, Goonies Weekend is being put on by the Clatsop County Historical Society in collaboration with the Seattlebased event planning company Gilly Wagon.

The milestone celebration is planned rain or shine. Registration is free, though some events will require a ticket. Most activities will be in Astoria, while others could extend into surrounding areas, such as Ecola State Park in Cannon Beach, where exterior scenes of the movie were filmed.

Tiered tours of the Goonies House in Astoria will be offered throughout the weekend. Regular visits on Thursday, Saturday and Sunday will be free for all.

Visitors can purchase additional tickets for a bus tour, a porch visit, the truffle shuffle stump, as well as a full tour package with all of the above. The VIP Cocktail Hour ticket will offer 40 guests access to the house, drinks and a mix-and-mingle with the attending cast and crew. This will be only the third time that access to the house has been open to the public.

June 7 continues to be celebrated as Goonies Day in Astoria, an official holiday by city proclamation.

Do & See

The house at Duane and 38th Streets recently changed hands. The new owner, Behman Zakeri, of Kansas City, is a selfprofessed Goonies superfan.

“I love the humor, the adventure and the endless pursuit to find the treasure,” he wrote in an email. “It’s a representation of my childhood in the ’80s. I've recited Goonies lines throughout my life.”

The movie also inspired him as a kid, he added. “It had so many teachings and messages throughout the movie: never say die … what true friendship is, don't judge a book by its cover, stick together, and the list goes on,” he said.

Zakeri has carried his love for the film since childhood.

“It takes a big fan that loves the movie so much to buy the Goonies House and share it with the world,” he said. “I always wanted to own the one and only Goonies House. I believed in my heart that I would be the best steward that would not only take care of the house, but also make it welcome for fellow Goonies all around the world.”

When he purchased the property in 2022 for $1.65 million, Zakeri also announced plans to renovate the house to match its appearance in the movie. While the transformation is still in its early stages, Zakeri has been working to equip the house with “gooniesbilia.”

The Rube Goldberg machine that opens the yard gate after Chunk does the truffle shuffle is about halfway built. And Zakeri has been collecting replica props to place inside the house, including film merchandise and memorabilia like action figures, toys and posters, as well as a model of Michelangelo’s David statue with Mikey’s mom’s “favorite piece” rendered as a magnetic appendage.

Organizers are asking visitors to remember the Goonies House is in a residential neighborhood and to keep disruption to a minimum by obeying parking signs and street closures and not littering. Walking or using the event shuttle is encouraged.

Zakeri is also assisting the museum in hopes of bringing members of the original cast to town for the festivities, to speak at events, sign autographs and take photos with fans.

As of February, no appearances had been confirmed. But weeks earlier, several Goonies alumni, including Josh Brolin and Corey Feldman, attended a hand-andfootprint ceremony at the Chinese Theatre in Los Angeles for Ke Huy Quan, who portrayed Data in the film.

Not only do the cast members still support each other, but many have expressed a desire to reunite for a sequel, which has been rumored over the years. In February 2025, Variety reported “Goonies 2” was “officially in the works,” with a scriptwriter hired and Steven Spielberg returning among the producers.

In June, guided tours of filming locations around Astoria will immerse visitors in the making of the original. Multiple screenings are also planned across town, as is a costume contest and various movie-related challenges, including geocaching and a treasure hunt. No word on whether any of the hidden treasures include truffles.

A special sweepstakes will also offer a night for two at the Goonies Jail, sleeping in the cell featured in the movie located in the old Clatsop County Jail, which houses today’s Oregon Film Museum.

Goonies Weekend will double as a fundraiser for the museum, with proceeds from the four-day bash supporting an ambitious expansion project.

"I believe I am the best steward that to not only take care of the house, but also make it welcome for fellow Goonies all around the world.”

According to McAndrew Burns, executive director of the Clatsop County Historical Society, which operates the museum, the 800-square-foot facility welcomed 53,400 people in 2024, an average of almost 150 visitors each day.

The museum is dedicated to promoting Oregon's film legacy. But, Burns said, in the current facility, “we just can't fulfill our educational mission the way we should. There are aspects of the story of filmmaking we aren't able to tell in that space. We want to tell the story of behind the scenes.”

Behman Zakeri unfolds a ladder to the attic of the Goonies House. He purchased the home in 2022 and is planning renovations to match its appearance in the movie.

In addition to exploring the mechanics of filmmaking, plans for the expanded museum include immersive exhibits concerning the state’s animation industry and liveaction movies filmed in Oregon.

“Five hundred major motion pictures and television shows have been filmed in the state of Oregon,” Burns said, including “The Fisherman’s Bride,” which in 1909 was the first commercial feature with a plot shot in the state, and the first to be made in Astoria. “We didn't name this facility the Astoria Film Museum or the Clatsop County Film Museum. We named it the Oregon Film Museum, and there’s a rich story to be told.”

Once the expansion is complete, the original jail location will become fully dedicated to “The Goonies,” which was added in 2017 to the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress.

The historical society has raised about 70% of the funding needed for the $10.1 million expansion project, according to Burns. The new, twostory 13,000-square-foot building at Seventh and Duane Streets, on the site of the former Morris Glass building, will resemble Astoria’s pier buildings on a footprint reminiscent of a camera aperture.

Construction is estimated to take about 20 months. While the ground is yet to be broken and the timeline set, the historical society has been doing preparatory work for the site, including a geotechnical survey required in the permitting process.

“In an ideal world, we’re opening at Goonies Day 42,” Burns said.

The campaign is still in its quiet stages, working with donors to supply the bulk of the funding. The museum was awarded a $1 million state grant last year.

As supplemental events, the historical society is also planning an ‘80s car show as well as an ’80s’ con at the Astoria Armory, replicating a popular convention event from the film’s 30th anniversary. The Clatsop County Heritage Museum will also feature a special exhibit about the old county jail, a key filming location that has become a pilgrimage site for fans worldwide. .

A treasure map and letter from Warner Bros. hang on an upstairs wall in the Goonies House.

Photo Credit: Joni Kabana

Bull kelp

An annual seaweed, bull kelp can reach heights of more than 100 feet each season, forming an underwater forest canopy. In recent years, about two-thirds of Oregon's kelp forests have disappeared.

Eat & Drink

A foraging journey

Crabbers come together

Eat & Drink

Our Picks

Fedé Trattoria

By Marianne Monson

In Italy, a trattoria is a neighborhood restaurant serving simple, regional dishes in a rustic setting. They’re often family-owned, with a focus on local ingredients. You don’t have to get on an international flight to experience one, though. On Astoria’s Pier 12, you can try Fedé.

The trattoria is a partnership between wife and husband Faith Davenport and Sean Hammond, who brought decades of restaurant experience to opening an eatery of their own. Initially drawn to the cuisine of Italy, it wasn’t until they visited the country that they fell in love with the food and ambience of small, regional dining spots and decided to bring that spirit back home.

Fedé’s ambience is decidedly cozy, with views of the Columbia River from both sides of the restaurant. A dozen tables are arranged around an open kitchen at the center, so diners can observe Hammond as he seasons a dish or places house bread into the stone oven.

The waterfront restaurant has cultivated partnerships with local farmers and fishers in order to create a cuisine with a strong nod toward seafood and other specialties of the lower Columbia. In traditional Italian style, the menu is arranged in four course offerings: antipasti, soup and salad, pasta and meat, fish and veggies — so the dining is fully customizable, ranging from small bites and drinks to multi-course meals.

Highlights include radiatori pasta with braised lamb, chanterelle fettuccine, mussels served with saffron, and a creamy burrata cheese laced with pesto sauce. For dessert, offerings include flourless chocolate cake, lemon tart or panna cotta finished with pine bud syrup.

Fedé does not accept reservations, so arrive early on weekends and summer days to get on the waitlist. Their largest table seats six, so it’s best for small gatherings.

In Italian, the word “fedé” translates as “wedding ring,” but the word also carries connotations of faith, belief and trust — a nod to the partnership that centers the restaurant, and the bravery it takes to open one in a small, coastal town. With loyal customers and strong reviews, that faith appears to have paid off.

Ilwaco Cider Co.

By William Dean

At this craft cidery in downtown Ilwaco on the Long Beach Peninsula, Vinessa Karnofski, a former chef, is forging a reputation as one of the most creative cider makers in the Pacific Northwest.

She and her husband, Jarrod Karnofski, opened Ilwaco Cider Co. last year with modest expectations. In a short time, they’ve surpassed initial goals thanks to strong regional support and a spacious, family-friendly taproom on Spruce Street. Live music is featured on Saturdays, and a long list of fun events is always in the works.

The star attraction, though, is the tantalizing array of hard ciders made with natural ingredients. The brews run the gamut from sweet to tart, in colors from straw to burgundy, but they all have something in common: complex flavors and aromatics.

One local favorite is Springrider Cran, made with locally grown cranberries, lime and wildflower honey. Another must-try is Columbia Fog, made with oolong tea, lavender, vanilla and orange blossom honey. For those wanting something zestier, there’s Ancho Libre, made with ancho and serrano chilis, pineapple, guava, papaya, fig and fennel.

“Blending is my absolute favorite,” Vinessa Karnofski said when asked what part of her new career she enjoys most.

She attended the Western Culinary Institute in Portland and worked for years as a chef, but with young children to raise, she wanted to rein in her runaway hours and turned to the hobby of home-brewing ciders.

“I needed to find something in line with my passion, which is cooking,” she said shortly before the cidery’s opening. “Something where I could be creative.”

Distribution of the ciders is already robust on the peninsula, where many restaurants and bars offer different flavors on tap. Fort George Brewery has also added it to the lineup. With no other craft cidery closer than Portland, expect the footprint to expand further onto the Oregon Coast.

Astoria

Ilwaco

Anna’s Table

By Peter Korchnak

Hailing from a local family of fishermen and restaurateurs, owner and executive chef John Nelson’s menu at this new Cannon Beach restaurant merges culinary traditions of the Oregon Coast with a nod to his Scandinavian heritage.

Regionally sourced — hunted, fished, farmed and foraged — ingredients sing in an interplay of old-world techniques, including brining, pickling, curing, grinding and smoking, to create simple, seasonal dishes prepared with thoughtful intention.

One menu mainstay, Manila clam linguine, lets the titular mollusk shine alongside fresh pasta. Another, lamb shank brined and braised with glögg, a Swedish mulled wine, and accompanied by lingonberries, harkens to the chef’s family origins.

Sturgeon from a seasonal tribal fishery on the Columbia River cassoulets with white beans and smoked pork. Crab cakes on a bed of watercress and radish salad awash in dill lemon creme fraiche highlight one of the Pacific Northwest’s most prized bounties.

The restaurant’s name is an homage to the chef’s mother and daughter, and its location — an unassuming residence-like building on Cannon Beach’s Hemlock Street — signals family comfort and coastal features. Diners at the source-to-table restaurant enjoy space to slow down and connect with the best that the wild nature of the North Coast yields in a clean, intimate interior.

A small, sommelier-curated wine list rotates Pacific Northwest and French creations, complemented by local microbrews and nonalcoholic beverages like pear cardamom shrub soda. The akvavit flight pairs well with Swedish cream to round out the experience.

Guests can also take the restaurant’s techniques and recipes, as well as Nelson’s stories, home in the chef’s cookbook “Dig a Clam, Shuck An Oyster, Shake a Crab.”

Feasts. Eateries. Libations. Recipes.

Long Beach

Cranguyma Farms

By Ryan Hume

October is well-known for its fall foliage. On the Long Beach Peninsula, there’s more to see, and much of it comes from the ground up. Shy chanterelle and porcini mushrooms peek out from their hiding spots on the forest floor. October is also when the many cranberry bogs on the peninsula are flooded.

Washington state is responsible for 3% of the United States cranberry crop, ranking it fifth in the nation. In 2023, the state pulled in over $10 million worth of the bitter berry most famously associated with Thanksgiving and Christmas. With its plentiful peat bogs, cool climate and specific latitude, the peninsula is one of the major producers in the state.

No wonder the Cranberry Museum is located in Long Beach.

Cranguyma Farms is the largest cranberry farm on the peninsula, with over 200 forested acres. The odd name is a sort of tortured portmanteau: “cran” obviously comes from cranberry, “guy” refers to the original owner, Guy C. Meyers, and the “ma” is his wife Amy’s name spelled backward so that the “y’s” overlap.

First established in 1940, Cranguyma is now under fifth-generation ownership. They have roadside stands in Seaview and Chinook that sell readypicked berries for $8 a gallon, but the fun is really to be had at the farm just north of Long Beach proper, where there is a dedicated bog for U-Pick cranberries throughout October. Pick what you want for 75 cents a pound.

If you visit the farm at other times of the year, Cranguyma also offers U-Pick blueberries throughout the summer and into the fall.

Nearby, the Cranberry Harvest Fair is a long-cherished annual event put on by the Pacific Coast Research Foundation at the Cranberry Museum. Usually on the second weekend of October, come see a wet harvest at the research center’s bogs behind the museum and stay for live music and cranberry-heavy breakfast and lunch items.

Cranberry harvesting also coincides with the peninsula’s annual wild mushroom season, when many of the area’s finest restaurants offer special menus featuring the region’s delectable forest fruits. Plan accordingly and a feast of earthy bounty awaits.

Cannon Beach

One wild weekend

Forging friendships through foraging

Imagine living in a land where the fruits of the forest and the sea can be plucked at will and transformed into a gourmet dinner, and then realize that, in fact, you do. The bounty of the Pacific Northwest is well-known, and celebrated for good reason.

Words: Ryan Hume • Images: Lukas Prinos

Plates are garnished with the lichen old man’s beard, or Spanish moss.

Fresh chanterelle mushrooms can go for $40 a pound during peak season. Willapa Bay oysters are shipped around the world. But the forest and the bay can be deceiving, offering plenty of poisonous alternatives to the good stuff, so it doesn’t hurt to have an expert on hand.

Enter Matt Nevitt, purveyor of all things wild. Formerly an engineer at Nike, Nevitt decided to exit the rat race more than a decade ago to pursue his lifelong passion of living off the land, a different sort of hand-to-mouth existence that he learned growing up in Raymond, Washington.

Nevitt has cultivated a reputation as one of the premier foragers in our region, providing restaurants throughout the Pacific Northwest with wild mushrooms and other found goodies. Chances are, if you are a fan of fine dining on the coast, you have nibbled on one of Nevitt’s treasures.

His company, Wild Foragers, also sells directly to the public through the North Coast Food Web in Astoria. Foragers, by nature, are notoriously secretive. They have to be to protect their special spots.

“I see myself as a farmer,” Nevitt said. “Or, more accurately, a caretaker of the land. All of the patches I visit tend to become more abundant each year, because I’m doing things to promote propagation and spreading seeds and spores as much as possible.”

So it was indeed a rare opportunity for Nevitt to offer a two-day guided tour of his choice patches among the waterways that slip through the trees off of the pristine Willapa shores. The spoils of this adventure would go home with the lucky participants. The apex of the experience — an allinclusive trip with a cost of $425, including tent camping on-site — was a Saturday night pop-up dinner at Wild Foragers’ Raymond headquarters, a celebration of the abundant wild foods of the area.

This event had gestated for more than three years, ever since Nevitt met Kenneth “Kenzo” Booth, chef and owner of Būsu in downtown Astoria. Būsu’s playful, Northwest-driven, Japanese-inspired menu relies heavily on local, foraged ingredients.

Nevitt was one of Booth’s first vendors, and the two soon became fast friends, dreaming up a way to combine their talents.

“(Matt) is incredibly kind,” Booth said. “And those are exactly the kinds of humans I want to be around, work with, and (I) consider him family.”

Jonathan Jones cooks up mushrooms on a Kasai Konro grill.

The planning

The October sky was shockingly blue and crisp above the Willapa River on the first morning of the event. These were good omens for the campers as they arrived to pitch their tents on the lapping waterfront of Wild Foragers headquarters, a property bought by Nevitt in 2014 on the original site of the Pacific County Marina.

“I’ve heard old stories of giant ships from Japan that once docked here to unload oyster seed and load up with our local trees to take back to Japan,” Nevitt said.

The property had also been an oyster cannery and a boat shop before Nevitt and his father helped build the house that now stands on the shore.

“Our area has long been known as one of the epicenters of the best wild mushrooms in the Pacific Northwest,” Nevitt said. “Also, Willapa Bay is considered one of the cleanest natural estuaries in the world due to many factors, including all the oysters filtering the water.”

The weather was just sheer dumb luck, but everything else was meticulously planned. Nevitt called on friends and family months ahead of time to arrange everything just so. Two long, live-edge tables on the dock that spilled out over the river had been harvested from an old-growth tree by Kaley Hanson, a friend of Nevitt’s who is a woodworker and owner of Raymond’s Pitchwood Alehouse.

The warehouse on the dock had been transformed into a semi-outdoor kitchen, though the structure itself had plenty of room for prep work, and a walk-in fridge Nevitt designed himself. Jessaid Pagán Malavé, a project manager from Seattle, was on hand with his partner, Cerena Gonzalez, to help make everything go smoothly.

Pagán Malavé had met Nevitt not even a year before, having taken one of his foraging classes. He soon took another.

Born in Puerto Rico, he spent years in New York City in the finance industry before heading west. “I used to think people who picked berries out of a bush were crazy,” he said.

Consider him a convert.

“I worry for a living,” Pagán Malavé said. “We needed a plan and needed to work backwards. He trusted me with helping to bring his vision to fruition.”

Soon all that worry would pay off as three borrowed boats were attached to a small convoy of trucks and the 20-odd foragers in muck boots were whisked away to undisclosed locations along the estuary that

Nevitt has sniffed out, cultivated and nurtured for years.

The group of hunters was diverse, hailing from all over the Northwest. Some were chefs Nevitt has supplied, others were foodies, or naturalists. They ranged in age from early 20s to early retirement. Most were novices, so Nevitt’s advice was on full display, teaching the participants how to clean mushrooms with a knife before placing them into a basket.

That first day’s haul was impressive. “We were able to find some great varieties of wild mushrooms that I was hoping to find. In particular, we found some of the most photogenic chanterelles and hedgehogs I’ve ever seen, and they were also some of the largest specimens I have ever found,” Nevitt said. “I led the group into the patches and they found them and they were so excited to find such amazing mushrooms.”

The Willapa Bay area has long been known as one of the epicenters of wild mushrooms in the Pacific Northwest.

Matsutake mushrooms grilled with salt and pepper on a bed of lichen and a splattering of chili garlic oil.

Eat & Drink

The kitchen

Back at the warehouse, jutting out above the river, prep had been ongoing throughout the day while the foragers had been hiking through the woods. Booth had enlisted his old friend, Thomas Carey, to pull off the big meal. The two had met nearly two decades ago in the now-closed kitchen of Le Bistro Montage in Portland.

Nevitt delivered all of the mushrooms to Būsu a few days earlier. Booth gauged it was about a week’s worth of prep for the main courses, though pickling started in the spring.

Nevitt estimated that over 90% of the ingredients used in the sevencourse menu arrived in the kitchen from less than a 20-mile radius.

There was a gas grill on the dock and propane burners for pots and pans, and, of course, an oven and stovetop up the hill in the house.

Booth and Carey were later joined by Jonathan Jones, the executive chef of the Astoria Golf & Country Club, who showed up with a very large piece of kitchen equipment. A Kasai Konro grill is a monster of a

box typically used in Japanese cooking, like yakitori, where small pieces of meat or vegetables are grilled inches away from a special type of smokeless charcoal called Binchōtan, which reaches impossibly high heats and can be used indoors.

“I was fortunate to get the third released in the United States,” Jones said. “I could not wait to use it so I thought it would be a great opportunity to break it in and put it out and see how it performed.”

This was only half of the grill. Jones and his wife, Stacey, hope to utilize the whole beast with a new cocktail and small-plate eatery called BAR X.O., which they plan to open in Astoria.

“I have not worked with Kenzo before,” Jones said. “But my wife and I are huge fans of his craft. To be honest, his izakaya is one of the main inspirations that made us feel like we can come out here and create a dining experience for the great community of Astoria.”

Everyone in the kitchen fell into a rhythm and spirits remained high through all the chopping, sauteing and grilling.

Chef Kenneth “Kenzo” Booth holds a bowl of black truffle miso mushroom soup with rice noodles and pork at Būsu in Astoria.

The feast

After a very long day, the whole crew was ready to sit down on the dock and eat through the dusk. The vibe was certainly camp casual — muddy boots, jackets, rain gear that never saw a drop. More people showed up, friends of Nevitt’s, including the tablemaker, Hanson, whose gorgeous work was now lined with an assortment of pickles and glass bottles of fresh Willapa Hills spring water that had been pulled straight from the source that afternoon. Nevitt produced a keg of Culture Shock kombucha, out of Seattle, frothy with a bit of bite.

Booth’s cooking philosophy is to follow the seasons and the pickles on the table reflected these transitions. Pickled fiddlehead ferns and oxeye daisy buds — bright, salty bursts done in the style of a caper — represented spring, while curried pickled chanterelles and rehydrated shiitakes seasoned with soy, ginger and apple cider vinegar spoke of autumn.

Soon, large platters of freshly shucked Willapa Bay oysters arrived — briny and pungent under a punch of mignonette — and the crowd turned ravenous. Looking down into the water surrounding the dock, you could see there were plenty more to be had.

“They are mother nature’s gift to us,” Jones said. “They are packed with so many great flavors and also they are super healthy and very abundant.”

But this was October in the Pacific Northwest, when the wild mushroom is king. Following the luxury of eating oysters on the dock, the remaining courses would be vegan and prominently feature mushrooms, each attached to its own wine pairing prepared by Jones, who was the evening’s sommelier, having won multiple awards at a winery before moving to Astoria.

“Personally, I’m a meat eater,” said Jordan Probasco, a longtime friend of Nevitt’s and a chiropractor in Astoria. “I was a little skeptical about a completely vegan meal coming at me and making my tummy tickle with excitement, but it did. Literally everything they put in front of us was epic. I tend to be a picky eater, but remained open to whatever came my way that night. And I’m glad I did. It was phenomenal.”

The first soup of the night arrived and set a high bar. Thai red curry paste and coconut milk were blended with five pounds of lobster mushrooms and a kelp dashi. The flavor was intense with just an edge of heat.

Next, thick slabs of matsutake mushrooms were grilled and served with a

crispy chili garlic oil on top of a spindle of old man’s beard, a stringy type of lichen that’s high in Vitamin C.