Do you know the median household income and the percentage of households who are living below the poverty line in your county? How about the percentage of adults with a college degree, or 9th graders on track to graduate from high school? How many child care slots are there per 100 children? How many electric vehicle charging stations?

Thanks to The Ford Family Foundation’s publication, “Oregon by the Numbers,” all this data and more is readily available and updated annually.

As a self-proclaimed data geek, I look forward to getting my copy of OBTN in the mail. It comes out in print in even-numbered years, and is updated online in between at www.tfff.org/oregon-numbers.

If you are an elected official, or if your work involves local or statewide policy, this is essential data. For everyone else, it’s important and interesting info that is displayed with easy-to-understand graphics.

This data helps explain many differences between the lives of urban and rural Oregonians. Some examples:

In Multnomah County, only 1.6% of housing units are mobile homes, but in most rural counties, 15% or more are mobile homes.

It’s not surprising that a one-bedroom apartment in Harney County goes for $575, while the same size apartment costs three times more in urban counties.

In urban counties, over 90% of households have broadband internet vs. fewer than 50% of households in Morrow, Wallowa, Lake, Gilliam, Grant and Wheeler counties.

Some may be surprised to learn that rural Wheeler, Wallowa and Gilliam counties have the highest vaccination rates for 2-year-olds in the state, well above the state average of 69% But then, rural Grant, Curry and Lake counties have the lowest rates. Hmmm.

Job growth, year-over-year, is generally highest in urban counties, with Multhomah County leading the pack. Four rural counties — Jefferson, Malheur, Lake and Sherman — lost jobs between 2022 and 2023.

These numbers alone don’t tell the whole story. But they do provide points of comparison and indicate where policymakers and philanthropists need to focus to make sure the needs of rural Oregonians are not forgotten.

— Kathryn B. Brown

Publisher Kathryn B. Brown

Editor Joe Beach

Contributors Carolyn Campbell

Justin Davis Bennett Hall Jayson Jacoby

David Jasper

Kyle Odegard

Evan Reynolds

Berit Thorson

Designer John D. Bruijn

COVER STORY Purple urchin farming » 4

FEATURES

On the Falls Fire line » 8

Temporary camps give firefighters a home » 12

Writing their way out from inside » 16

MAKING A LIVING

Flower farms thrive in Southern Oregon » 20

THE LAND

Hikers share love of eastern Oregon trails » 22

Invasive tree of heaven spreads » 26

THE CULTURE

Oregon’s new Poet Laureate » 30

Publisher Kathryn B. Brown, kbbrown@eomediagroup.com

Editor Joe Beach, jbeach@eomediagroup.com

On the cover: Commercial urchin divers Charles Cupell and Nate Jones PHOTO COURTESY BRAD BAILEY

Published quarterly by EO Media Group © 2024

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to The Other Oregon, PO Box 1089, Pendleton, OR 97801

The Other Oregon is distributed to 5,000 influential Oregonians who have an interest in connecting all of Oregon. As we strive to close the urban-rural divide, please help us with a donation. If you are a business leader, you can support our efforts by advertising to our unique audience. To subscribe: TheOtherOregon.com/subscribe. For advertising information: TheOtherOregon.com/advertise

THANKS TO OUR SUSTAINING SUPPORTERS, WHO MAKE IT POSSIBLE TO DISTRIBUTE THE OTHER OREGON TO 5,000 INFLUENTIAL OREGONIANS AT NO CHARGE

STORY & PHOTOS BY CAROLYN CAMPBELL

On a sunny afternoon, Port of Bandon director Jeff Griffin pulled back black shade cloth from the corner of one of nearly a dozen aquaculture tanks lining the dock. Spiny, purple urchins clung to the sides. Down below, others slowly crept along the bottom of the tank.

“We’ve been testing out different feeding systems. They seem to like cabbage along with red algae the best,” Griffin said. “In kelp beds, without a predator, they chew through the kelp forests without restraint. Here, when we drop in cabbage, they seem to courteously pass pieces down for those below.”

Griffin and his team are part of ambitious statewide efforts led by divers, researchers, tribal leaders, entrepreneurs, chefs and visitor associations, all scrambling to prevent further decimation of once towering kelp beds by ravenous purple urchins.

Steve Rumrill, Shellfish Program Leader for Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, said 70% of Oregon’s kelp has been lost in the last eight to 10 years.

“We had what we call the perfect storm,” Rumrill explained. “Due to shifting ocean climate, unusually warm seawater, and the mass mortality of sea stars, the dramatic increase in the purple sea urchins has led to dead zones where thousands and thousands of emaciated, ‘zombie’ urchins carpet the barren sea floor.”

Tom Calvanese, Oregon State University’s Port Orford Field Station manager and Oregon Kelp Alliance (ORKA) director, asserted that restoring Oregon’s ocean habitat is an “all hands on deck” moment requiring as many resources as possible to stabilize the kelp forests and the ecosystems they support.

“We need citizen divers to cull urchins. We need research divers to garner a better understanding of the crisis at hand. We need commercial divers. And we need resources to support restorative commercial enterprises that can provide opportunities for small business owners.”

In 2021, Griffin was one of Oregon Kelp Alliance’s divers, culling urchins overpopulating Nellie’s Cove in Port Orford. After an afternoon of culling, Griffin began mulling another solution.

“Due to shifting ocean climate, unusually warm seawater, and the mass mortality of sea stars, the dramatic increase in the purple sea urchins has led to dead zones where thousands and thousands of emaciated, ‘zombie’ urchins carpet the barren sea floor.”

— Steve Rumrill

Shellfish Program Leader for Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife

“What if instead of killing these urchins, we harvested them, fattened them up, and sold them for their uni, an international seafood delicacy of the once prolific red urchin population?” Griffin believed that purple urchins, under the right conditions, could produce a delicious uni comparable to the more highly prized red urchins.

Combining Oregon State University (OSU) research permits with Hatfield Marine Science Center (HMSC) Sea Grant funds, Griffin’s team embarked on a study testing whether barren urchins could be made commercially viable.

Dividing the zombie urchins into various tanks along the dock, they began their tests. What conditions would the urchins need to stay alive? What would they eat? What wouldn’t they eat? How long would it take for emaciated urchins to become edible? And could they become tasty enough that people would want to eat them? After months of experimenting, the team developed a system where the zombie urchins could be fattened into delicious commercial grade uni within 10-12 weeks. »

While his aquaculture team experimented with how to best “grow” uni in these starved urchins, Griffin networked with divers, chefs, other researchers, and the Oregon Coast Visitor Association.

Brad Bailey, a commercial diver, was one of the first to partner with Griffin. Using Bailey’s commercial permit, Griffin began a new experiment. In a still thriving kelp forest, the pair harvested healthy urchins while purposely creating an urchin-free “moat” around the edge of the forest. Their hope was to slow the pace of destruction. A year later, the forest was still flourishing.

Nearly two years after Griffin began his trials, Port of Bandon hosted a community tasting event. Rory Butts, executive chef at Bandon Dunes Golf Resort, attended.

“Cabbage-fed urchin was the winner, hands down,” Butts said. “Uni is not for everyone. Many of our guests have never even heard of it.” Butts’s chefs began experimenting with dishes that would be ‘accessible’ to their diners. Uni carbonara served with crispy fried dulse was the first to reach the menu.

“It was quite dramatic,” said Butts. “When the dish was served, a couple from another table asked what it was.” Recognizing that his efforts won’t solve the kelp crisis, Butts believes serving uni introduces golfers from around the world to Oregon’s coastal challenges.

Marcus Hinz of the Oregon Coast Visitor Association (OCVA) agrees with Butts.

“Uni is not going to be for the average local person. But, if it brings in visitor dollars to support our communities, that’s a start.”

According OCVA’s latest figures, some $840 million is spent each year by visitors to the coast on food alone, but very little of that fortune is spent on locally landed seafood. In fact, 90% of seafood sold and consumed along the Oregon Coast is not from Oregon.

To keep more seafood in their community and support a local seafood economy, OCVA launched its ocean cluster initiative focused on enhancing the use of local sustainable seafood in small businesses through infrastructure investments, workforce training, and partnership development. Partnering with the Port of Bandon and nearly a dozen entities who share their vision, OCVA’s ocean cluster initiative aims to improve local seafood access to local markets, impacting fishermen, processors, wholesalers, retailers and consumers.

One of OCVA’s partners, Newport-based Central Coast Food Web (CCFW), was recently awarded a $477,000 federal grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Local Agriculture Market Program. Founded by restaurateur and sustainable fishery leader Laura Anderson, the Central Coast Food Web provides services and support to small, independent food producers to make it easier for all people to eat local food.

Griffin’s Port of Bandon project and Bailey’s newly launched enterprise, OoNee Sea Ranch, were both awarded funding assistance from CCFW.

Aaron Huang, OoNee’s cofounder and chief executive officer, asserted, “Prior to the opening of Central Coast Food Web there was no place to locally process our urchin. They can survive for

decades nearly starving, but once harvested urchins need to be processed quickly. OCFW’s equipment alone has been a godsend. But perhaps equally importantly, they’ve helped us navigate complicated and confounding regulatory requirements.” Huang emphasized, “There are millions of urchins devouring kelp, ready to be harvested. If we can scale our business and bring processed uni to market quickly, we can start to bring our ocean ecosystem back into balance, provide a great product for an expanding market, and make a sustainable livelihood.”

Huang believes regional leaders like Griffin, Hinz, Calvanese and Anderson are the vital connective tissue needed to ensure success of emerging regenerative aquaculture businesses.

“These people see what’s needed. They are the ones connecting with legislatures, regulators, and also the local community. They know what needs to be done.”

Frustrated by the slow pace of change, Huang added, “But is it percolating up to the state level? Can the necessary changes in licensing, permits and other regulations move fast enough?” Huang paused.

“Without a clear framework and sufficient funding from the state, many restorative aquaculture businesses won’t succeed. We’re hoping people like Jeff will encourage the state to help businesses like ours turn zombie kelp destroyers into delicious delicacies.”

Carolyn Campbell is a freelance writer.

Tour of the Falls Fire on July 16 showed the power and unpredictability of a big blaze

STORY & PHOTOS BY BENNETT HALL

The Falls Fire began on July 10 in the vicinity of the Falls Campground, about 25 miles northwest of Burns on the Malheur National Forest’s Emigrant Ranger District.

On July 13, the fire started out at around 5,000 acres — and then it just took off. By day’s end, the fire had grown more than tenfold, to 55,000 acres, with zero containment.

“When that happens, there’s not much you can do — the fire’s in charge,” Incident Commander Kevin Stock told a group of local residents in Seneca on the evening of Tuesday, July 16, when the blaze had grown to 91,000 acres.

“That day when the fire took its big run, the most important thing was luck — and trying to get people out of the way.”

Crossing the line

On July 16, Grant County Sheriff Todd McKinley took me

on a tour of the fire zone. Driving southwest on the Izee-Paulina Highway, he pointed out some of the Grant County ranches that could be at risk if the fire spreads farther north.

He and some of his deputies had spent the past few days checking campgrounds, advising campers to leave the area and checking in with ranchers.

“We’ve got everyone evacuated (from the campgrounds),” he said. “The only people that should be out there are firefighters and landowners dealing with their own property and cattle.”

At that point, he said, ranch hands had gathered as many cattle as they could from grazing allotments in the path of the fire and put them on pastures on their home ranches. But with the fire ravaging the grazing allotments on national forest land, that meant summer forage was going up in flames.

“It’s going to put a big hurt on cattlemen in the area because they’re going to have to go to fall grass,” McKinley said.

On July 13, the Falls Fire started out at around 5,000 acres — and then it just took off. By day’s end, the fire had grown more than tenfold, to 55,000 acres, with zero containment.

Still, he said, things were much worse south of the county line.

“There’s whole ranches in Harney County that have burned up.”

His biggest concern was that the fire would start moving north. Turning south on Grant County Road 68, he steered his pickup toward the fire, continuing south as the road transitioned to Forest Service Road 47 and driving up to the northwest edge of the blaze.

“Right now we are just about 3½-4 miles below the county line,” he said. “Everything below here is just nuked. ... This burning up here, if left unchecked, will be all up in those ranches.”

Heading north again, the sheriff turned east on FSR 3750, which runs just below the Grant County line before meeting up with FSR 37.

“This is the road I do not want to see it get past,” he said.

Noting the absence of firefighting personnel on the fire’s northern front that day, McKinley wondered why trees near the road hadn’t yet been limbed or felled.

“They could prep this whole thing, and then that becomes your containment line.”

McKinley turned northeast on FSR 37, then southeast on FSR 31, aiming to get around the fire’s eastern flank. But then, rounding a corner, his fears were realized: The fire was burning on both sides of the road.

“It has jumped the 31, right here,” McKinley said, stopping his truck. “This is going to mess up somebody’s day.”

A Forest Service vehicle with two men inside approaches McKinley’s truck, heading the other way. They stopped to talk to the sheriff and exchange information, and then one of the men got on the radio.

“He’s yelling at them on the radio,” McKinley said, returning to his vehicle, “trying to get someone up here and get this thing lined.” »

The next stop was an old gravel quarry just west of Highway 395 near the Idlewild Campground, about 20 miles south of Seneca. It was being used as a staging area for fire crews.

There were a couple of bulldozers on flatbed trailers hitched to big trucks, some small wildland fire engines and a number of trucks and vans for transporting fire personnel. Fire crews were standing or sitting near their assigned vehicles, waiting for orders. They were wearing hard hats and yellow, fire-resistant Nomex shirts, and most of them are grimy with accumulated soot.

Derek Jensen is part of Washington Task Force 1, an 11-person team of firefighters from Thurston and Grays Harbor counties in Washington who arrived at 4:30 a.m. the previous day with four brush tenders, a water tender and a command vehicle to help fight the fire.

Their main task to that point had been clearing vegetation around buildings in the fire area as a preventive measure, but they had been forced to fall back earlier in the afternoon.

“We were up the road yesterday and today, and the fire got pretty intense,” Jensen said. “We were up there prepping structures and (the fire) started moving pretty quick, so we had to pull back.

“In about 30 minutes we go back to camp,” he added. “The night shift will come on and take over.”

Meanwhile, there was activity in another part of the staging area. A big truck had fired up its engine and had begun hauling one of the bulldozers toward where the fire had crossed the 31 road.

A public meeting had been called for that evening in the Seneca Community Hall. By the scheduled start time of 6:30 p.m., around 80 people had packed the sweltering room to hear an update from Stock, the incident commander of Pacific Northwest Complex

Incident Management Team 8, and other fire managers.

Since the fire’s big run on July 13, he said, the team had brought in significant reinforcements and had made some headway on building containment lines and prepping structures during lulls in the fire’s growth.

“We’re up over 1,000 (firefighters), probably around 1,200 now,” he said.

“We’re much more set up to handle the size of the fire and much more set up to take advantage of those opportunities when they happen.”

After presentations from half a dozen fire managers, the floor was opened up to questions. In the audience are residents from around the area — Seneca, Bear Valley, Izee — and, not surprisingly, they had concerns.

They wanted to know where the fire was and where it might go next. They wanted to know where the firefighting crews were. They wanted to know what the team’s firefighting strategy was. They wanted to know if they and their families would be safe.

Stock did his best to allay their fears. At that moment, he told them, the fire was moving mostly south and southeast, toward Burns, which is why they hadn’t seen a lot of activity in their area.

But fires — especially big fires — can be unpredictable, he cautioned. All he and his team could do was to concentrate the resources they had where they would do the most good, and make as much headway as possible on containing the blaze.

And that, he added, is exactly what they were doing.

“I feel very good about where we’re at today — today was a good day,” he said.

“I am feeling pretty good about the plan and the resources coming in to execute the plan.”

Bennett Hall is editor of the Blue Mountain Eagle.

• Data-driven insights

Content development •

Targeted messaging •

Predictive analytics •

• Sentiment analysis

• Influence mapping

• Policy tracking

Artificial intelligence is the future, and it’s here. That’s why our team is earning certifications to harness the power of A.I. technology and meet our clients’ needs.

STORY & PHOTOS BY JUSTIN DAVIS

The tiny town of Long Creek saw its population temporarily rise to one of the largest in Grant County with the construction of a fire camp this summer.

The fire camp, just up the road from Long Creek School, was divided into three smaller units on separate fields and served as home to anywhere from 800-1,300 camp staff and firefighters from all over the country who fought the Battle Mountain Complex and Courtrock fires in northwestern Grant County and southwestern Umatilla County.

Construction of a fire camp is a massive logistical undertaking that begins many hours before the first tents are erected and the meals served.

Consisting of several hundred tents, a fire camp resembles a colorful nylon city with its own portable kitchen, laundry service, showers, garbage pickup, medical facilities and internet connectivity.

At the same time, it’s not entirely self-sufficient. One of the challenges of operating a fire camp is to be careful not to exhaust the camp’s own resources or those of its host community.

A constant game of supply checks and coordination takes place in the camp, ensuring those who call the camp their temporary home have everything they need to effectively tackle whatever wildfire they fight, whether they’re resting and recovering at the camp itself or out working on a fire line in the remote wilderness.

The most critical time in setting up a fire camp is the 48-hour prep period before any actual construction begins. The first steps toward constructing the fire camp in Long Creek actually happened in Monument, where the camp was originally slated to be built. David Allen, a fire cache manager with the Oregon Department of Forestry, said he and his team started scouting fields near the Monument School, which was set to be the camp’s command and control center. »

Consisting of several hundred tents, a fire camp resembles a colorful nylon city with its own portable kitchen, laundry service, showers, garbage pickup, medical facilities and internet connectivity.

That plan changed after a Level 3 “go now” evacuation notice came July 22 for the town of Monument.

“That’s where the team looked to Long Creek because of past experiences here in this town, at this school, and then fields right across the street where we’ve had previous (fire camps),” Allen said.

Once the location and size of a camp is set and the fields are prepped, Allen puts in a request for one of 24 caterers contracted to provide food to fire camps. Then he goes on the hunt for three things: potable water, ice and Gatorade.

“Right off the bat, the kitchen comes in with 400 gallons of potable water,” he said, but that goes fast. He also has to line up water tenders to keep a steady stream of clean water for drinking, cooking and cleaning coming into the camp.

“That’s really, really important,” he said.

Gray water, or water that has been used to wash dishes or shower with, also requires disposal, and that means working with local public works officials and wastewater treatment plants so as to not stretch a municipality’s resources too far.

Allen said the key is being aware of what a city can and can’t produce. This dynamic caused Allen to reach outside of Grant County — and, in some cases, outside the state — for suppliers who provided what the Long Creek camp needed.

The camp’s ice came from Kennewick. Trucks from Boise came every few days with Gatorade and Powerade. And vehicles at the camp relied on gasoline and diesel fuel delivery trucks to ease the burden on Long Creek’s only gas station.

Once the kitchen was set up, the shower trailers came in. As the number of camp residents increased, the number of shower trailers also grew, peaking at three plus a laundry trailer to support a population of 1,300 firefighters and camp staff.

Portable toilets, handwashing stations and air-conditioned group tents for night shift firefighters who sleep during the day also made their way to the camp.

“We basically are able, within 24 hours, to launch a fleet (of supply trucks) out of Salem where I work at the headquarters and bring it to any city in Oregon,” Allen said. “And, within another 24 hours, set up a mobile city.”

Justin Bush was the Long Creek camp’s receiving and distribution manager. The Astoria native is in his sixth year with the Oregon Department of Forestry and is responsible for outfitting firefighters with whatever they need while they are toiling on hot fire lines.

Bush said he has an initial cache of supplies that arrive by van, and extra supplies are ordered as needed. Those supplies are bound for firefighters on the front lines.

As those orders come in via radio, Bush coordinates runner trucks to make deliveries to any of more than 90 drop points. Commonly requested items such as hose kits are ready to go out to fire lines immediately, while more unusual requests can take time, Bush said, although he added emergency needs can be fast-tracked.

Unforeseen circumstances can create logistical challenges. On one recent fire, for instance, Bush had to place an emergency order for extra cold weather sleeping gear.

“We had a cold snap,” he said, “and burned through all of our sleeping bags.”

Bush described supply distribution as “organized chaos.” What makes that chaos work, he added, is his crew, saying they are prepared, motivated and work as a team.

“This can’t be done by myself,” he said.

When the time comes to pack up and head out of town, Bush and his crew will reacquire the resources they issued to firefighters and move on to the next fire.

“The most fun about this is knowing we’re getting people what they need,” Bush said.

By the beginning of August, the fire Long Creek camp’s population had shrunk from a high of around 1,300 to just about 800 as crews gained more control of the Battle Mountain and Courtrock fires and some resources were demobilized or reassigned.

“We have the ability now to start packing some of that (equipment) up and sending it back to Salem for rehab,” Allen said at the time, “so my guys in Salem can get the fleet turned around, replenished, counted and ready to go to the next fire.”

Planning begins several days prior to teardown to ensure demobilization of a camp goes as smoothly as possible. When the incident management team decides a fire is going to be turned back to the local fire district, Allen sends a group from the cache to help break down the tent city and transport it back to Salem to rehab it before it gets sent out again.

Justin Davis is a reporter for the Blue Mountain Eagle.

Both can be donated to charity through your Oregon Community Foundation. No matter what type of asset you have to share, OCF can guide you through an easy, enjoyable and successful process to assure your gift is received and you get the best tax benefits possible. As your statewide community foundation we help you, help others . Let’s get started.

STORY AND PHOTOS BY BERIT THORSON

hillip Luna, like other editors-in-chief of news outlets, spends his days researching topics, interviewing people, writing articles and editing his staff writers’ stories.

Unlike other editors, he does all of that from prison.

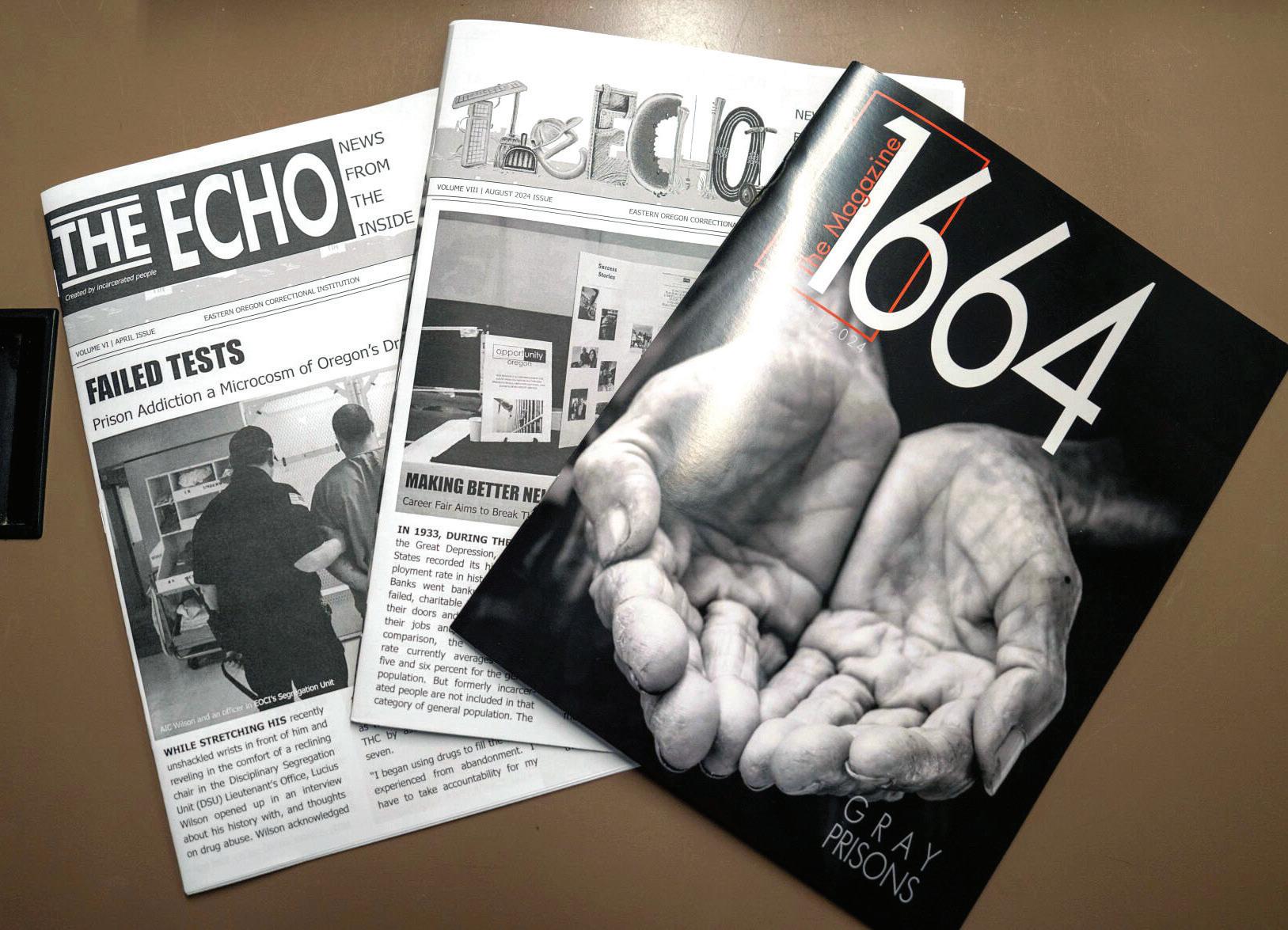

Luna is incarcerated at Eastern Oregon Correctional Institution in Pendleton and runs the Echo, the monthly prison newsletter for other adults in custody. Stories range from profiles of other men in prison and correctional officers to how the fentanyl crisis has made its way into prisons.

The Echo started as a way to keep people up to date with upcoming events or opportunities around the prison, but it has expanded since being established in 2018.

Today, the Echo also reports on topics such as sports, clubs, educational programs and rehabilitative initiatives. It’s one of only a few dozen known prison newspapers across the country.

Each month, the team of writers — which reached a new peak of five this spring — produces enough content for a 25- to 40-page newsletter, which also features a few press releases, job notices, a recipe and a crossword at the end of each edition. But for Luna, it’s as much about the content as it is about who’s making it.

“I want more writers because there are different voices than mine, and that’s important,” he said.

Different people are tuned into different parts of prison life, Luna said, so having more staff members helps broaden the coverage and highlight stories that might otherwise be overlooked.

Ray Peters, who runs EOCI’s institutional work programs, added that news in prison spreads quickly despite the newsletter only coming out once a month.

“The name was a little bit tongue-in-cheek because we report on things that everybody already knows about because it’s such a small place,” Peters said.

Because the staff members live alongside everyone else, Luna said, they hear the rumors and it makes it a little easier to chase a story down. However, despite a small population possibly making it easier to be aware of what’s going on around the prison, it has its drawbacks.

Luna said his reporters have to be aware of the impact of their roles and how they fit into the community there, which is true of journalists everywhere, but especially in a place where there’s so much rigidity and hierarchy involved in daily life.

“You have to be careful because whatever you say, at the end of the day you have to live here,” he said. “And if you say something that offends people or you say something that labels you a certain way, it could be a really negative thing.”

After about six years of publishing some form of the newsletter, Luna and Peters decided to expand their efforts to include a quarterly magazine, 1664. The name refers to the 1,664 state and federal prisons nationwide that were open when they started the magazine.

1664 will focus less on news and more on arts and culture, human interest and feature stories that emphasize the humanity of people who are incarcerated, Luna and Peters said.

For example, the magazine’s first edition, “Gray Prisons,” includes a profile about the only hospice care volunteer left at EOCI, despite there being a desperate need for more help since prisons nationwide have aging populations. »

The stories capture humanity and question basic assumptions about what it means to be someone who is incarcerated.

“It’s humanizing the environment,” Peters said. “This is a way to say, ‘Hey, maybe he’s wearing blue, but he’s got this whole life story. He’s a person, he has dreams, he has hopes, he has things he wants to do, he has things that made him the way he is. He’s trying to overcome his struggles.’”

Highlighting the good

EOCI has 1,682 beds and housed 1,297 people as of Aug. 1. People inside can access the Echo in

“Also, I have found that I really care about the people here,” he said. “I want their stories in the newsletter. I want people to know the people that I’m seeing.”

Before he came to prison, he said, he would have assumed prison was for bad people who’ve done bad things.

“But that’s not all they are,” he said, “and I think that’s really important.”

Berit Thorson is a reporter for the East Oregonian.

Wanda Exec.

Director,

Turtle Cove Created a comfortable home and haven for her community, and families in need.

Flowers can improve small farms’ bottom lines, helping them blossom and survive.

STORY & PHOTOS BY KYLE ODEGARD

When Beth Wismar started working for Fry Family Farm about 20 years ago, the ag operation was the only booth selling bouquets of flowers at Southern Oregon farmers markets.

“In the past five to 10 years, we’ve had so much more competition,” Wismar said, as she wrapped flowers destined for local grocery stores.

But Wismar, the farm’s greenhouse manager, said it’s great to see more businesses dabbling in blooms.

Diversifying with flowers can boost small farms’ bottom lines, helping them blossom and survive, she added.

At the Ashland Tuesday Market on Aug. 13, several farms sold flowers along with fruits, vegetables and other products.

Steven Gidley, owner of Lakota’s Garden near Jacksonville, Ore., offered peaches and squash, but posies pushed profits.

Patrons purchased most of his bouquets and garlands, and the $250 from flowers was about 75% of his sales that day.

Gidley has been growing flowers for the 25 years he’s been farming, but he started focusing more heavily on them in the past five years or so.

“Since we’ve been doing this pretty consistently, people know and we have several repeat customers. … We usually have one of the more colorful booths,” Gidley said.

He estimated that flowers now encompass about 20% of his business.

Nora Kendall said Runnymede Farm, near Rogue River, tries to keep flower bouquets affordable at around $10.

“We sell a lot of them,” added Kendall, a Runnymede employee.

Siskiyou Seeds, an organic grower near Williams, offers seeds for about 250 varieties of flowers, said Wali Tipping, son of owner Don Tipping.

But the business’ booth also sold marigold garlands, dahlias and Australian everlasting flowers.

“I’ve probably pulled in $200 off of flowers today,” Tipping said.

That represented about a third of the booth’s sales — flowers alone justified coming to the Ashland Tuesday Market for Siskiyou Seeds, Tipping added.

Joan Thorndike runs Le Mera Gardens, which started 32 years ago as an independent wholesaler but merged with Fry Family Farm to become its flower section.

For Fry Family Farm, flowers are just another important aspect of diversification, another crop to sell to retailers, at the farm store — which has a kitchen to create value added products — and at farmers markets. Local weddings also are a critical component of flower sales.

Thorndike, a Chilean immigrant, said community members initially considered her strange because the U.S. didn’t have a strong fresh, seasonal flower culture.

“In Chile, we always have flowers around,” Thorndike said.

She wanted to make flowers a part of daily life in a region with an incredibly rich and long growing season.

That cultural shift has gradually occurred, Thorndike said, in large part due to local farmers markets and growers providing posies.

Thorndike is glad so many ag operators are growing flowers now in Southern Oregon.

STORY BY JAYSON JACOBY

Helen Loennig’s earliest memory of hiking in the Elkhorn Mountains near Baker City involves a heavy tent and a temper tantrum.

But her affinity for the range has proved more influential than that unpleasant introduction.

She was about 2½.

She accompanied her father, Frank Loennig, to an alpine jewel that her dad knew as Green Lake but is shown on maps today as Red Mountain Lake.

As she climbed the steep switchbacks that lead to the lake, she decided the tent was too great a burden.

There was something of a scene.

Decades after that difficult hike, Loennig spends as much time as possible in the Elkhorns and other local mountains.

She continues to be inspired by her dad, who died in 1993.

“He just loved these mountains, and I guess that love transferred to me,” she said. “He took me all over those mountains as a kid.”

But Loennig has used that affection to do something that wasn’t available to her father.

In May, she and her daughter, Kate, who’s 11, started a website designed to introduce other hikers to the Elkhorns.

The site — hikingbaker.com — includes maps, descriptions, difficulty ratings and other information for more than two dozen hikes.

And the Loennigs aren’t the only Baker City hikers going online to help fellow wanderers.

Amy Hindman started her website, Eastern Oregon Family Hiking Guide — easternoregonfamilyhikes.com — about four years ago.

Hindman and Helen Loennig had similar motivations — filling an online void.

“There’s not a lot of great resources for our area,” said Hindman, who moved to Baker City in 2015 with her husband, Jeremy, who grew up in the area.

Loennig said she noticed the relative scarcity of detailed information about trails in the Elkhorns last year when she sought to fulfill what she called a “bucket list” item — hiking to all of the lakes that she first visited decades ago with her dad.

Although Loennig found quite a lot of sites describing trails in the Eagle Cap Wilderness — Oregon’s biggest, at 350,000 acres — the situation was vastly different with the Elkhorns, most of which are not designated wilderness.

She became frustrated.

“And when I get frustrated about something, I tend to try to do something about it,” she said.

Loennig and her daughter started to gather information about their hikes.

Then they decided to create a website.

Hindman said her family started hiking more in 2020, during the pandemic.

“Since everything was closed, it was a good year to start exploring more,” she said.

As with the Loennigs, hiking — and gathering information for the website — is a family activity for the Hindmans.

They have four children: Anne, 14, Will, 12, Levi, 10, and Jack, 7.

Neither website is a money-making venture.

“I just really love hiking and I enjoy sharing this information with people,” Hindman said. “I hope it helps people out.”

She said she relishes receiving comments on her site from people who have used the descriptions to find a hike they liked.

Loennig’s motivations are similar.

“I want people to get out and exercise,” she said.

Loennig said the topics on her site have “snowballed” in the two months or so since she started it.

She decided that in addition to posting details about local hikes, she would turn the site into “sort of a base camp for Baker.” »

That led Loennig to add nonhiking sections, including lodging options, gear recommendations, local restaurants, a list of businesses she and her daughter have patronized, and one she’s especially excited about — a calendar of local events.

Although both Loennig’s and Hindman’s sites focus on the Elkhorns and the Phillips Reservoir area, each has featured hikes elsewhere in the region.

Hindman, for instance, has information about hikes in the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, in the La Grande area and a couple in the Wallowas.

Energy Trust of Oregon offers cash incentives when you upgrade your aging equipment to energy-saving models. From efficient ductless heat pumps to top-of-the-line insulation, energy-efficient equipment will keep your business cool and comfortable, even on the hottest days. Upgrade today to start saving energy and money. Learn more at www.energytrust.org/existingbuildings

Loennig’s choices include hikes around Olive Lake and in the Ben Harrison Mine area, both on the Umatilla National Forest west of Granite.

Hindman, whose site reflects her preference for hikes that are suitable for families, said her favorite spot in the Elkhorns is Crawfish Lake, southwest of Anthony Lakes.

“My kids love Crawfish Lake,” she said.

Swimming in the lake isa reward for kids after the hike.

Jayson Jacoby is editor of the Baker City Herald.

STORY BY EVAN REYNOLDS

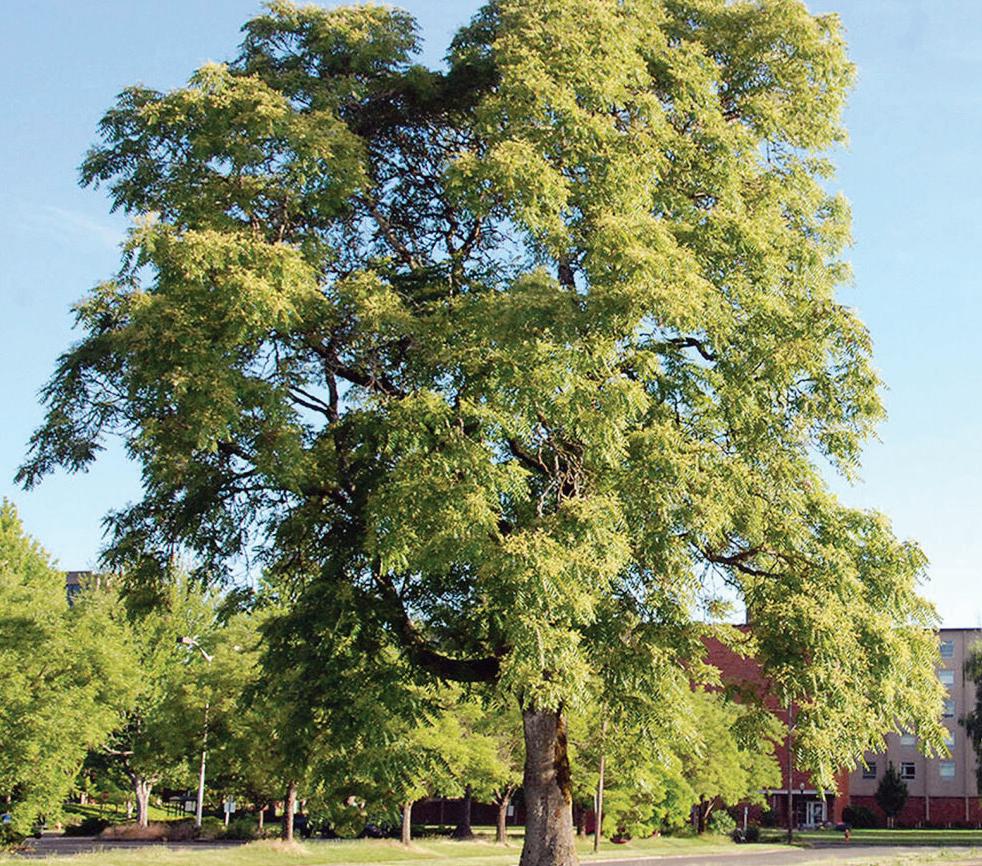

Tree of heaven, a noxious weed and invasive tree, is making an indelible mark on the Pacific Northwest — and confounding the officials attempting to control its spread.

“Something is definitely triggering more fecundity, and we’re not sure what it is,” said Beth Myers-Shenai, a noxious weed specialist at the Oregon Department of Agriculture.

A female tree of heaven can produce more than 300,000 seeds annually, and the trees can’t be removed via simple cutting methods. Their roots will sucker into the soil, resprouting as far as 50 feet from the parent tree. It is native to China and Taiwan. When crushed, its leaves produce a smell comparable to rotten peanut butter.

The tree has spread to the Pacific Northwest, where it is commonly found along riverbanks and is especially prevalent along the Interstate 5 corridor and east of the Columbia Gorge, Myers-Shenai said.

“As a non-native to the northern U.S., it doesn’t have a natural enemy, so it doesn’t have any natural controls keeping it in check, like other native plants do,” Myers-Shenai said.

Tree of heaven was first added to ODA’s noxious weed list in 2013, as the weed became more prevalent across the state. It’s listed as a “B” weed — more intended to raise awareness about the plant than to control or eradicate it, given how widespread it is throughout the region, Myers-Shenai said.

Nevertheless, some jurisdictions have made attempts to combat the plant, like Wheeler County, home to the John Day River Basin.

Cassandra Newton is the district manager of the Wheeler Soil and Water Conservation District.

Newton submitted a grant application to ODA that attempted to eradicate tree-of-heaven in Wheeler County, but was denied.

“Compared to other areas in Oregon, we felt we had a small enough infestation that it was able to be eradicated,” Newton said.

“In the Columbia Gorge area, or over near Umatilla on Highway 730, those infestations are so massive that you’re talking millions of dollars and multiple years of work.”

Newton did say the county has used some of its Bureau of Land Management funding to treat tree of heaven, in collaboration with ODA.

Complicating efforts to fight tree of heaven is the spread of the spotted lanternfly, which has been detected in at least 18 states as of 2023. The invasive insect can infest and destroy numerous crops, including stone fruit orchards and vineyards — and tree of heaven is its primary host.

While there have only been isolated sightings of the spotted lanternfly in Oregon and Washington, some officials say its arrival is a question of “when” — not “if.”

A female tree of heaven can produce more than 300,000 seeds annually, and the trees can’t be removed via simple cutting methods. Their roots will sucker into the soil, resprouting as far as 50 feet from the parent tree. It is native to China and Taiwan.

“It’s estimated that (spotted lanternfly) will be here in two to four years,” said Renee Hadley, the conservation district manager in Walla Walla County, Wash. “We don’t want to have it find the tree of heaven and propagate like crazy.”

Hadley recommended eradicating any tree of heaven within half a mile of orchards and vineyards to provide a future “buffer” against the spotted lanternfly.

While solutions for tree of heaven infestations are slim, a new approach could soon be introduced, said Joel Price, a biological control entomologist with ODA. Introducing the snout weevil, also native to China, could do significant damage to the tree — its larvae tunnel underneath the bark and help it become susceptible to disease. The weevil is currently in the federal permitting process, Price said

“There is an added importance to controlling both an invasive weed species and insect pest all at once,” he said.

Evan Reynolds is a Snowden intern at the Capital Press.

Nonprofit behind The Oregon Rural End of Life Doula

Nonprofit behind The Oregon Rural End of Life Doula Initiative

The Peaceful Presence Project, based in Central Oregon, provides end-ofplanning and care and for families in collaboration with palliative and hosp They offer end-of-life doula training and provide support to people living Oregon The fees for services are offered on a sliding scale and they also o "compassion funds" to help make care accessible for many low-income fam

The Peaceful Presence Project, based in Central Oregon, provides end-of-life education, planning and care and for families in collaboration with palliative and hospice services They offer end-of-life doula training and provide support to people living in rural Oregon The fees for services are offered on a sliding scale and they also offer "compassion funds" to help make care accessible for many low-income families

This spring, with funding from The Roundhouse Foundation, The Peacef Project was able to recruit and train a cohort of 15 individuals in Southern of The Oregon Rural End of Life Doula Initiative Participants learned pra information about advance care planning, end-of-life care resources, and l well as how to plan and coordinate vigils among loved ones so people can during a dying person’s final hours Participants also learned how to provi

This spring, with funding from The Roundhouse Foundation, The Peaceful Presence Project was able to recruit and train a cohort of 15 individuals in Southern Oregon as part of The Oregon Rural End of Life Doula Initiative. Participants learned practical information about advance care planning, end-of-life care resources, and legacy work, as well as how to plan and coordinate vigils among loved ones so people can be together during a dying person’s final hours Participants also learned how to provide psychosocial and practical support to dying individuals and their care partners during and after death.

Those who participated were recruited from Coos, Curry, Douglas, and Josephine counties in Oregon. Counties which have a disproportionately high percentage of residents over the age of 65 in comparison to the rest of the state. There are only three small hospitals each serving a maximum of 50 patients a day. In these locations hospice and palliative services are limited, and in some cases non-existent. The presence of these new doulas, who can provide some of the social support dying patients require, is vital

Learn more about The Peaceful Presence Project at ThePeacefulPresenceProject.org

The Roundhouse Foundation is proud to support The Peaceful Presence Project’s work in Southern Oregon through the Oregon Rural End-of-Life Doula Initiative and the organization’s continued work throughout Oregon in 2024

STORY BY DAVID JASPER

Longtime Bend poet and nonfiction author Ellen Waterston has been appointed Oregon Poet Laureate by Gov. Tina Kotek.

The Oregon Cultural Trust, which funds the award, announced Waterston’s two-year appointment on Aug. 15

“It’s an honor. It’s a challenge, and I’m very, very excited that Tina Kotek has recognized the vibrant literary community on the east side of the Cascades with this,” Waterston said.

“My father used to say, ‘If you paddle in milk long enough, it turns to cream,’” Waterston said. “I’ve been preaching poetry and prose in the Oregon outback for a long time. The work is its own reward for sure, but I have to say, with this appointment, things just got a lot creamier.”

Waterston’s accomplishments in the literary world are many. Her poetry collections include “Hotel Domilocos,” “Vía Lactéa” and “Between Desert Seasons.” Her nonfiction writings include “Walking the High Desert,” “Where the Crooked River Rises” and “Then There was No Mountain.” A new book of essays, “We Could Die Doing This,” is slated to publish in the fall.

Waterston founded and directed the Bend literary festival The Nature of Words for over a decade and, more recently, founded The Writing Ranch, a for-profit concern offering workshops and retreats for emerging and experienced writers.

Her recent honors include receiving, in April, Literary Arts of Oregon’s Stewart H. Holbrook Award for significant contributions enriching Oregon’s literary community. In March, Waterston was given Soapstone’s Bread and Roses Award, which honors women who have sustained the writing community.

The poet laureate fosters the art of poetry, encourages literacy and learning, addresses central issues relating to humanities and heritage, and reflects on public life in Oregon, according to the Oregon Cultural Trust. Waterston is the state’s 11th poet laureate, succeeding slam poet Anis Mojgani, who was appointed in 2020. An official laureate ceremony will take place in the early fall.

“My hope is to touch every county in that time in some way, shape or form,” she said.

David Jasper is a reporter for The Bulletin in Bend.

this for the long run.

Since 2012, Coordinated Care Organizations have improved health outcomes for Oregonians while saving taxpayer dollars.

This is because CCOs are making community based investments in preventative care, maternal health, early childhood services, and other social determinants of health that create a healthier future for Oregon.

Oregon Farm Bureau is the state’s most inclusive agriculture organization, representing about 6,300 family farmers and ranchers who raise everything from cattle to hazelnuts. First established in 1919, Farm Bureau is a grassroots, nonprofit organization representing the interests of family farmers and ranchers in the public and policymaking arenas. We aim to keep agriculture thriving for future generations, expand its economic opportunity and viability, and educate society about why ag is important.

Our policy and political priorities develop from a democratic process, beginning at the county level. Positions, ideas, and initiatives then make their way to the OFB annual convention, where Farm Bureau members from around the state meet to discuss and vote upon the organization’s goals for the coming year.