My note in our Fall 2023 edition lamented the failures of Measure 110 in both urban and rural Oregon.

The Oregon Legislature focused on this issue in its recent session and leaders passed a measure that would again criminalize the possession of drugs such as methamphetamine and fentanyl, while encouraging and funding drug treatment.

Two weeks ago, I was walking past the Salvation Army in downtown Pendleton. I noticed the door of the portable toilet in the middle of the parking lot was wide open. A man was lying face up in the parking lot next to it. He was pale, not moving, and seemed to be barely breathing.

As I approached him, I reached for my cellphone and for the Narcan I carry in my purse, and looking around for help. There was no one in sight.

I shook his shoulder and yelled to try to wake him up, noticing a lighter and pipe inside the portable toilet and his belongings in a cart nearby.

I stood over him with phone in one hand and Narcan in the other, trying to decide what to do next. Should I administer Narcan and hope he didn’t wake up swinging at me? Call 911?

Then, after a minute, his eyelids flickered. I put my phone and Narcan away. A passerby — someone who knew this man from previous interactions — helped me get him up and over to a bench and said he would stay with him. I went on my way, believing there was no help or advice I could offer that would make a difference for him.

I know that hundreds of other Oregon public safety officers and citizens have been in a situation similar to mine over the past three years. Interacting with people deep in the throes of addiction is hard. If they want help, it’s hard to find. If they don’t want help, there have been no levers to pull to get them to a place where they will accept help.

Starting Sept. 1, law enforcement in Oregon will have a lever to pull when they find someone in possession of illegal drugs. However, the challenge ahead for counties is to create “deflection” programs to help break the cycle of addiction with the funding available. It will be an ongoing challenge for years to come.

— Kathryn B. BrownA VOICE FOR

TheOtherOregon.com

Publisher Kathryn B. Brown

Editor

Contributors

Designer

Joe Beach

Laura Kostad

Samantha O’Conner

Bennett Hall

Nella Mae Parks

Taylor Bayly

Carolyn Campbell

Kyle Odegard

Daniel Brooks

Paul Matli

John D. Bruijn

Advertising design Kevin Weidow

CONTENTS

COVER STORY

Air ambulance can be a lifesaver » 4

FEATURES

Baker County birth center closure » 10

Pine Mountain Observatory » 14

Combating the addiction crisis » 18

MAKING A LIVING

Helping fellow farmers and fishers » 20

Business development centers » 22

THE LAND

Ag census results » 28

THE CULTURE

Veteran offers free haircuts and more » 30

Publisher Kathryn B. Brown, kbbrown@eomediagroup.com

Editor Joe Beach, jbeach@eomediagroup.com

On the cover: A Life Flight helicopter waits on Interstate 84 as rescue crews load a crash victim.

JAMES VOELZ/LA GRANDE RURAL FIRE DEPARTMENT PHOTO

Published quarterly by EO Media Group © 2024

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to The Other Oregon, PO Box 1089., Pendleton, OR 97801

The Other Oregon is distributed to 5,000 influential Oregonians who have an interest in connecting all of Oregon. As we strive to close the urban-rural divide, please help us with a donation. If you are a business leader, you can support our efforts by advertising to our unique audience. To subscribe: TheOtherOregon.com/subscribe. For advertising information: TheOtherOregon.com/advertise

Air medical transport can be a lifesaver in remote Northeast Oregon, but it isn’t cheapSTORY BY LAURA KOSTAD, SAMANTHA O’CONNER and BENNETT HALL

Northeast Oregon is a land of wide-open spaces and natural solitude, far from the hustle and bustle of city life.

Most people out here prefer it that way. But in a medical emergency, the isolation that goes with the region’s rural lifestyle can be a problem.

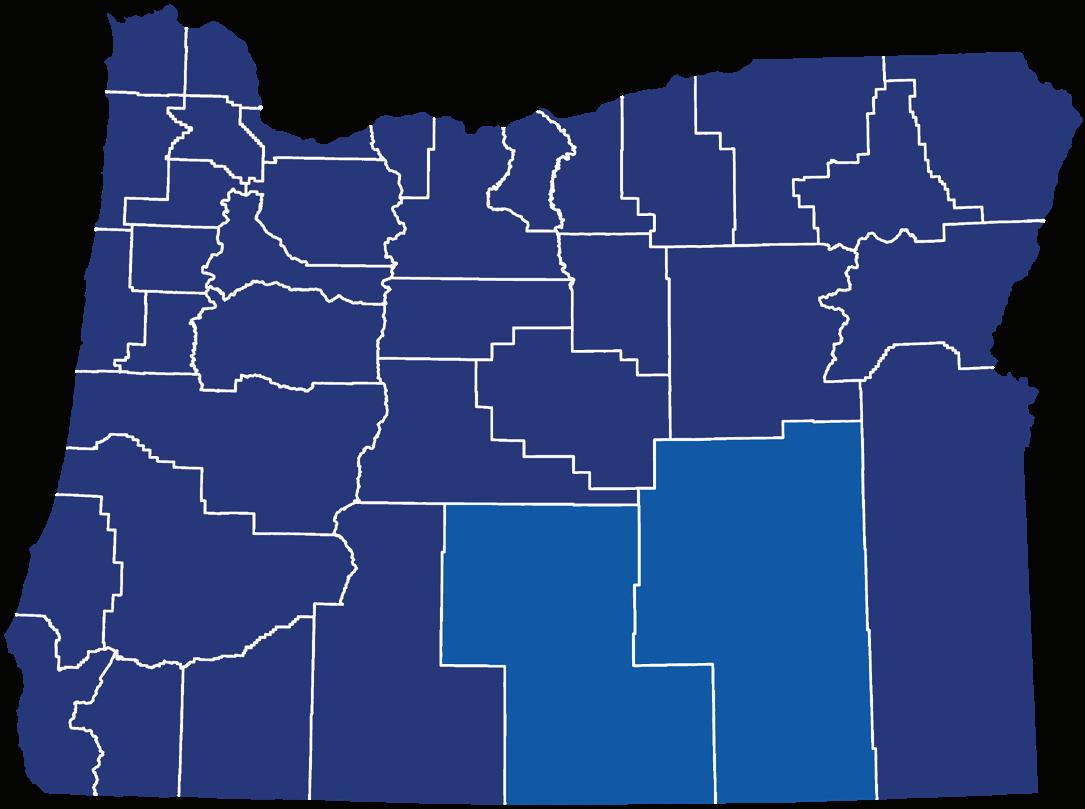

The six counties that make up Oregon’s upper right corner cover more than 18,000 square miles, an area two-thirds the size of West Virginia and larger than nine U.S. states. Scattered across this farflung region are seven critical access hospitals, each licensed for a maximum of 25 beds.

In Northeast Oregon, if someone falls gravely ill on a remote ranch or is severely injured in a car wreck on a lonely twolane highway, the nearest hospital can be an hour or more away by ambulance — if one is available. And if a patient’s medical condition requires specialized treatment, that can mean a three-hour

drive or more to get to a larger hospital in Bend, Boise or Portland.

That’s where air ambulance service comes in.

There are a number of private companies that provide medically staffed helicopter or fixed-wing aircraft to transport patients quickly in an emergency.

In remote rural areas like Northeast Oregon, that can mean the difference between life and death — but it can also mean a hefty bill, especially for people who lack the proper insurance coverage.

“There’s no two ways around it — air ambulance transport is expensive,” said Natalie Hannah, a spokesperson for Life Flight, a not-for-profit air medical transportation company that operates in Oregon, Washington, Idaho and Montana.

“The cost of 24/7/365 readiness, state-of-the-art medical and transport equipment, employing the foremost emergency care providers, as well as the level of care and medications administered, and distance of transport all contribute to the overall cost.”

In Northeast Oregon, there are three companies that provide air ambulance transport, either by helicopter for shorter trips or fixedwing plane for longer flights. All three offer membership plans at a cost ranging from $60 to $99 a year, depending on the provider.

Air ambulance memberships are not a form of insurance. Rather, when a member uses the service, the air ambulance company bills the patient’s primary medical insurance and, if applicable, the patient’s secondary insurance plan. This includes Medicare.

In remote rural areas like Northeast Oregon, an air ambulance can mean the difference between life and death — but it can also mean a hefty bill, especially for people who lack the proper insurance coverage.

Normally, a patient without a membership would then pay the balance of charges up to the allowed amount — a figure that could total in the tens of thousands of dollars, depending on the circumstances.

For example, under one Asuris Northwest Health plan, after the patient’s deductible is met, Asuris will cover 80% of the allowed amount for any air ambulance provider and the insured party is responsible for the remaining 20% of the bill. Coverage varies between insurance providers and individual plans.

However, the picture is a little more complicated than that. Not all air ambulance providers will sell memberships to those without primary medical insurance that includes benefit provisions for air ambulance transport, though they will still provide transport to uninsured patients. This does not pertain to Medicaid recipients, who, by federal law, cannot be held liable for air ambulance charges. »

In a study published in 2019, the U.S. Government Accountability Office analyzed air ambulance transport data among privately insured patients from 2017. GAO found that the median price charged by air ambulance providers at that time was about $36,400 for a helicopter transport and $40,600 for a fixed-wing transport.

For those living in rural areas, the cost of emergency transport can trend even higher due to the longer distances that must be traveled by air ambulance providers.

Out of 60 consumer complaints received by two states collecting data on individual balance bills analyzed by GAO, all but one complaint regarded a balance bill of over $10,000.

At that time, GAO found that over two-thirds of ambulance transports for patients with private insurance were out of network. Generally, out-of-network providers are covered at a lower rate by insurance companies than those they are contracted with — meaning consumers wind up paying more of the cost.

Unlike when one is browsing local health care providers and checking network status with one’s medical insurance, in an emergency medical situation, a patient doesn’t have a choice in which air ambulance provider is dispatched to transport them.

According to the GAO study, which air ambulance company is called largely depends on proximity or established relationships between hospitals and air ambulance providers, followed by who is available to provide transport. First responders or hospital personnel are the ones who ultimately make this decision, which can leave patients who might not even be conscious when the call is made holding a hefty bill if they don’t have a membership with the provider that responds.

Although the state does not regulate air ambulance membership programs, Oregonians enrolled in commercial health insurance are somewhat insulated from high air ambulance costs by a federal law that went into effect at the start of last year.

“Protections are in place to ensure coverage of air ambulance services and prevent consumers from receiving large out-ofnetwork bills,” said Jason Horton, public information officer for the Division of Financial Regulation at the Oregon Department of Consumer and Business Services.

“The No Surprises Act prohibits air ambulance companies from billing beyond the applicable in-network amount and requires the insurer or employer payer to reimburse an amount subject to binding arbitration. Out-of-network providers of air ambulance services cannot bill or hold liable participants, beneficiaries, or enrollees in group health plans or group or individual health insurance coverage who received covered air ambulance services for an amount greater than the in-network cost-sharing requirement for those services,” he explained.

Horton added that the cost-sharing requirement is generally based on the lesser of the median of contracted rates payable to in-network providers of air ambulance services or the billed amount for the services.

This, however, doesn’t resolve the issue of expensive in-network patient responsibility, the cost of which still has the ability to cripple many people’s budgets.

If one has a membership with the air ambulance company that provided transport, though, then there is no further patient responsibility beyond what one’s insurance pays. As long as membership is established prior to air ambulance transport being called, it will be honored. »

The Oregon Rural Teacher Corps (ORTC) is making significant strides in addressing the critical shortage of educators in rural districts across the state. Established as a collaboration between Eastern Oregon University (EOU) and the Oregon Community Foundation (OCF), this innovative program aims to recruit, train, and support teachers committed to serving in rural areas.

The Oregon Rural Teacher Corps (ORTC) is making significant strides in addressing the critical shortage of educators in rural districts across the state. Established as a collaboration between Eastern Oregon University (EOU) and the Oregon Community Foundation (OCF), this innovative program aims to recruit, train, and support teachers committed to serving in rural areas.

Moreover, the ORTC is committed to promoting diversity and equity within rural schools. By recruiting teachers from diverse backgrounds and providing training in culturally responsive teaching practices, the program seeks to create inclusive learning environments where all students feel valued and supported.

Moreover, the ORTC is committed to promoting diversity and equity within rural schools. By recruiting teachers from diverse backgrounds and providing training in culturally responsive teaching practices, the program seeks to create inclusive learning environments where all students feel valued and supported.

The ORTC recognizes the unique challenges faced by rural communities, including limited access to educational resources, small student populations, and geographic isolation. To combat these obstacles, the program provides comprehensive support to aspiring teachers, including scholarships, mentorship opportunities, and specialized training in rural education.

The ORTC recognizes the unique challenges faced by rural communities, including limited access to educational resources, small student populations, and geographic isolation. To combat these obstacles, the program provides comprehensive support to aspiring teachers, including scholarships, mentorship opportunities, and specialized training in rural education.

One of the key features of the ORTC is its emphasis on community engagement and cultural competency. Participants in the program are encouraged to immerse themselves in the local community, fostering strong relationships with students, families, and community members. By understanding the specific needs and values of rural communities, ORTC teachers can better tailor their approach to education and make a lasting impact on students' lives.

One of the key features of the ORTC is its emphasis on community engagement and cultural competency. Participants in the program are encouraged to immerse themselves in the local community, fostering strong relationships with students, families, and community members. By understanding the specific needs and values of rural communities, ORTC teachers can better tailor their approach to education and make a lasting impact on students' lives.

Since its inception, the ORTC has seen promising results, with a growing number of educators choosing to pursue careers in rural schools. By addressing the shortage of teachers in these under-served areas, the program not only improves educational outcomes for students but also strengthens rural communities as a whole.

Since its inception, the ORTC has seen promising results, with a growing number of educators choosing to pursue careers in rural schools. By addressing the shortage of teachers in these under-served areas, the program not only improves educational outcomes for students but also strengthens rural communities as a whole.

Roundhouse Foundation is proud to support the Oregon Rural Teachers Corps student cohort.

Roundhouse Foundation is proud to support the Oregon Rural Teachers Corps student cohort.

The second class of the Oregon Rural Teacher Corps at the Eastern Oregon University campus in La Grande. Pictured left to right are in

Another complicating factor in this equation, though, is that there are often multiple air ambulance providers operating in a given area, all owned by different companies. Depending on where one lives, it begs the question: Which memberships do I need to be reasonably protected in the event of an emergency medical situation?

In Northeast Oregon, there are three companies that might be called: Aurora-based Life Flight Network, Air St. Luke’s of Boise or Bendbased AirLink Critical Care.

Some providers have multiple bases strategically placed around the state to respond to calls. For those affiliated with a hospital system, transport is not solely tied to that hospital; air ambulances will deliver patients to wherever staff conducting the transfer specify.

Fortunately for prospective patients, some of these providers honor one another’s memberships through reciprocal agreements. For example, Life Flight and Air St. Luke’s both belong to the Association of Air Ambulance Membership Programs. Essentially, if a patient is a member of one AAMP company, that patient is a member of all. So if a patient has a Life Flight membership but Air St. Luke’s shows up to provide transport, Air St. Luke’s will honor the Life Flight membership and not hold the patient responsible for any additional billing beyond what their insurance pays.

In Northeast Oregon, AirLink is the exception to that rule. While AirLink is part of AirMedCare Network, which provides members with protection at over 320 locations across 38 other states, the company does not have reciprocal agreements with all of the other providers in Northeast Oregon.

That can be an issue in places like Grant County, where air ambulance coverage is provided by both AirLink and Life Flight.

Rebekah Rand, director of emergency medical services for the John Day-based Blue Mountain Hospital District, said people who live in the area need a policy for each provider.

If someone were to be in an automobile accident and that person has a Life Flight membership but is picked up by AirLink, Life Flight will not cover the cost of the transportation. It is the same for an AirLink member being transported by Life Flight.

“We recommend people have coverage with both agencies,” Rand said.

Membership services representatives at all air ambulance providers contacted for this story recommended that individuals reach out to their local hospital to find out in what order air ambulance providers in their region are contacted to determine which memberships would be most advantageous for them.

All providers operating in Northeast Oregon offer one-year, multi-year and, in some cases, even lifetime memberships which can discount the annual cost of renewal.

Why is air ambulance service so expensive? It’s not just the high cost of aviation fuel.

The helicopters and airplanes used to transport critically ill or severely injured patients are not simply flying taxis — they’re airborne treatment centers with the sophisticated equipment and trained medical personnel needed to keep people alive while they’re being transported to the hospital.

Take the Life Flight Network as an example.

“Our aircraft (both helicopters and fixed wing) are mobile intensive care units, featuring the same state-of-the-art equipment that you would find in a hospital ICU,” said Hannah, the company spokesperson.

“Our aircraft are staffed by highly trained pilots, flight nurses, flight paramedics and flight respiratory therapists who undergo regular advanced training to remain proficient in their skills and to ensure that we are operating at the highest levels of safety.”

From the moment the patient comes aboard the aircraft, the medical personnel can provide treatment and stabilization for a host of lifethreatening conditions, ranging from heart attack to stroke, trauma, airway obstruction and blood loss, among others, Hannah said.

Another cost factor is the overhead that goes into making sure those services are available when they’re needed.

Life Flight maintains helicopter bases and 10 fixed-wing bases across four states. Pilots and medical crew members are required to be available 24 hours a day and are housed at the company’s bases to ensure rapid response times.

“Our helicopters are typically off the ground within 8-10 minutes from the time of dispatch, and this state of readiness is costly,” Hannah said. “It includes the behind-the-scenes operations of our communications center, our maintenance staff, training personnel and administrative operations.”

Oregon Money Watch is a campaign finance database with muscle. It converts raw data into useful and actionable information, using graphs and illustrations to demonstrate how money flows into and out of campaigns over time.

By aggregating data and providing head-to-head district matchups, Oregon Money Watch not only helps political professionals better understand the integration of money in politics, but helps inform sophisticated strategies for their own investments.

The next time you’re driving through Eastern Oregon, try not to be pregnant or get in a car crash in Baker County. We can’t help you anymore.

On Aug. 26, 2023, the only birthing center in Baker County closed.

It was proceeded in death by Baker County’s only ICU and pediatric care center earlier in 2023.

The closures were opposed, mourned, and are now suffered by the community of 16,000 people they served.

The decisions to close the ICU/pediatric center and birth center were made by MBAs, not MDs, in the St. Alphonsus and Trinity Medical network. The decisions were made by people who will never know someone who was in a car wreck in North Powder or a baby in Sumpter — but I do.

This is a story of one family I have known most of my life, and how they are living through the loss of critical medical care in Eastern Oregon.

This is only one story. It doesn’t capture the experiences of the other rural folks, people of color, poor folks — those most affected by health care deserts.

There’s just no way I can explain how it feels when someone far away looked at some numbers and decided to close your ICU,

your pediatric care center, and your birthing center knowing their decisions would certainly kill some of us.

I called my friend Dallas Defrees as she recovered at her home and family ranch in Sumpter from a high-risk pregnancy and hard birth. In the background new baby Clementine cooed.

Clementine is Dallas and her husband Riley Hall’s second child. Their son, Roby, was born a few years ago at the St. Alphonsus Medical Center in Baker City. While her first pregnancy was tough, Dallas said it was made easier by the fact she had a long relationship with her doctor.

“My doctor saw me go through years of infertility, then get pregnant, then she saw me through a traumatic birth, and now she cares for me and my son.”

Dallas anticipated the same “circle of care” in Baker City with her second birth. But his time her doctor would not see her through delivery.

In August, Dallas and Riley had to start planning how to have a baby in the winter in a rural county. The next closest maternity care options were in La Grande, 70 miles away, and Ontario, 100 miles away, from their home in Sumpter Valley.

“First, we thought of delivering in La Grande but with the closure of the Baker ICU and birthing center, they are taking on a huge patient load,” said Dallas.

The couple considered Pendleton, two snowy mountain passes away, as well as Boise, Idaho. They knew with Dallas’ high-risk pregnancy they would have to find a new doctor and move temporarily to be near a birthing center.

“The week before we moved to Boise, I sat in my living room and watched the storm outside,” said Dallas. The freeway was closed in both directions meaning she couldn’t go to La Grande or Boise. “I thought, ‘I don’t know what would happen if I went into labor now.’ I didn’t know if I could even make it to the Baker ER or if Life Flight would be available.” Dallas worried about all the scenarios.

But she is fortunate to have a nurse (her husband Riley) and a doctor (her brother Dr. Nathan Defrees) to lean on.

“I want to make clear how lucky we are,” said Dallas. “As hard as this was for us, this would be devastating for people in our community who don’t have the funds, means, transportation or familial and friend support to have a birth somewhere else.”

At 36 weeks she started having early labor. Dallas and Riley made the move to Boise, leaving Roby with his grandparents. “It was so hard to leave him,” she said. “I felt like I didn’t know if I would see my son again.”

Four days after they arrived in Boise, Dallas went into labor. The birth had complications. Baby Clementine aspirated blood and needed medical care. Dallas had placenta accreta, a serious condition where the placenta grows into the uterus.

“I was having blood loss and had to have an emergency hysterectomy and a blood transfusion.”

She imagined what might have happened if she had been driving from Baker to Boise in labor.

“I have quick labors so even if the roads had been open, I could have had a baby on the side of the highway. In that scenario, I probably would have died.” »

Nathan’s wife Jess Defrees, a teacher in Baker City, had two of their three children at St. Alphonsus in Baker.

“I knew what we had in Baker was really special. It wasn’t just convenient; it was really quality care,” she said. “I didn’t take for granted the quality of care in Baker, but I took for granted the access.”

Idaho’s ban on abortions adds greater uncertainty. The ban has put a lot of Idaho physicians in a tough spot, not knowing what care is legal or allowed. That affects Oregonians too, as fetal medicine doctors and OB/GYNs leave Idaho.

As Jess’ husband, my friend Dr. Nathan Defrees explained, “In rural communities we rely on urban centers for advanced health care access. To not have that access [in nearby Idaho] makes it more dangerous to be pregnant in Eastern Oregon.”

Eastern Oregon women with high-risk pregnancies or labor complications must make a new calculation.

If they need a “big city hospital,” do they go to Boise or Portland? Boise is closer, but doctors may be restricted from providing life-saving care in the wake of the confusion and fear of the abortion ban. Portland doctors can provide care, but in an emergency, they may be too far away to provide it in time.

The Defrees’ see the lack of local decision-making power as a primary reason St. Alphonsus closed the ICU, pediatric care, and birthing center in Baker City.

“What has happened in Baker is a cautionary tale — don’t give up local control of your hospital,” Dr. Defrees told me.

He points out that while birth centers have been closed in big hospital chains in Springfield, Redmond, and Toppenish, Wash., independent hospitals in John Day, Enterprise, La Grande, and Burns still have maternity care.

Nathan and I went to OSU with another rural family physician, Dr. Eva McCarthy, who spent three years at Burns’ communitycentered rural hospital. Dr. McCarthy served some of the most remote Oregonians at the Harney District Hospital where people may have to travel two hours one way to see a doctor. During pregnancy this is a huge burden.

“A ‘normal’ pregnancy requires at least 14 check-ups but people over age 35 or who have high blood pressure or other medical conditions need more frequent visits,” she said.

She worried about her patients spending so much time on remote roads where cell service is spotty.

“It could be 45 minutes before another car comes upon you,” she said, “and if you need medical care on the highway, it could take an ambulance an hour to reach you.”

Dr. McCarthy also enumerated other challenges in rural hospitals besides distance including weather and lack of access to specialists. But she also emphasized the resiliency of rural health care and strong relationships in rural communities.

“People in Burns had a wide range of skills they built up intentionally to weather challenges. I don’t see that in suburban and urban communities where people just fill their singular role. It is just a different mindset — to equip yourself to be useful in lots of different ways for your community.”

Dr. Defrees sees Harney District Hospital as an example of the local control and decision making that is needed now.

“In Baker we need to move toward a county health district and a

community-run hospital. We have an opportunity to provide better local care.”

The challenges for Baker City and rural and underserved communities are growing. Dr. McCarthy worries we will see more loss of medical access in Oregon.

“When other large healthcare systems see how easy it is to shut down maternity care in Redmond and Baker, it could become a domino effect.”

But she says these closures shouldn’t continue — they should trigger a bigger conversation.

“Shutting down maternity wards is absurd. It is the canary in the coal mine for our health care system.”

For large hospital systems, the cost of 24/7 birthing center staff in small hospitals is the problem. Most rural hospitals lose money on maternity care, and many rural communities are aging.

I want adequate, robust care in rural communities, so I started spitballing ideas to Dr. McCarthy about using telemedicine or volunteer rural fire departments to fill the maternal care gap.

She stopped me.

“I admire how rural communities are good at making do, but people in power should know better and do better for rural people,” she said. “Decision makers take advantage of the resilience and selfefficacy of these rural communities.”

“We should not accept solutions for rural people and underserved communities that do not provide the proper standard of care,” she said.

Dr. McCarthy illuminated the downside to a tightknit community that scrambles, fundraises, problem solves with limited resources. My whole rural life I haven’t expected better or more. I realized that at some level, I believed part of living out here was accepting less and getting by.

Or as Dallas put it, “rural women pride ourselves on being hardy.” But her recent birth experience is not something we should accept or expect for anybody.

“The big health care systems are deleterious to our welfare and well-being. We don’t matter to them. Literally, Dallas and Clementine don’t matter,” she said. “They are more worried about losing money than losing people.”

The money versus life tension of health care is hard to take. Health care has a dollars and cents cost, but we don’t value life that way. Health care should be about people, but it is so often about money.

“Hospital administrators and MBA’s make decisions about health care using business models, but health care isn’t Amazon or Microsoft — it’s people’s lives,” Dr. McCarthy told me. “The value proposition should be focused on basic human rights.”

I am mad as hell about the situation in Baker County, but the same disparities and worse are unfortunately shared. We know by the numbers people of color, poor people, and rural people have some of the worst outcomes under this harmful healthcare model.

As Jess Defrees put it, “I watched Nathan go through his medical training with the oath to ‘do no harm.’”

“But health care decisions are in the hands of people far away, and their choices are actively doing harm to my community.”

Nella Mae Parks is a farmer and freelance writer from Cove, Ore.

“I give because I saw what an impact one person can have in our community.”

— BRIAN R ESENDEZ, DONOR SINCE 2021

In 2020, a project was launched that turned empty hotels into homes for the unhoused, including people who’d lost their homes in the recent wildfires. Brian Resendez, a broker bringing hotels into the fold, was so moved by the experience that he became a donor to support organizations providing critical services to the unhoused. Thank you, Brian. Want to find the perfect match for your generosity? Oregon Community Foundation can help. Let’s get started.

About 30 miles southeast of Bend, the Pine Mountain Observatory offers a stunning glimpse into the dark skies of Oregon’s High Desert.

Operated by the University of Oregon Department of Physics, the observatory integrates university-led research, public outreach and private research efforts. The observatory is set to reopen to the public this spring, and here’s your guide to visiting.

“Our core mission is undergraduate research,” said Alton Luken, the observatory’s head of operations.

Right now, students at the University of Oregon are using the observatory’s telescopes to examine the brightness of stars — focusing on changes in brightness that may suggest a planet passing in front of them. The recorded change in brightness, also known as luminosity, is shared with organizations that search for planets outside our solar system.

The observatory, while small, plays a crucial role in completing research conducted by larger telescopes, Luken said.

“In all the vastness of our galaxy alone, we have found thousands upon thousands of planets. These planets are looked at for whether they could be life bearing. It’s the burning question,” Luken said. “It boils down to human curiosity. Knowledge is good. Knowledge helps us understand our place in the galaxy. Every day, astronomers wake up and chip away at that big question – it’s in our DNA.”

The observatory’s main attraction is a 24-inch telescope, though the observatory also operates a 15-inch telescope and several smaller portable telescopes that are used depending on the number of visitors.

Amateur astronomers often set up their personal telescopes, too. The observatory encourages people to bring their own telescopes or binoculars, and electrical power is available if required. »

The observatory’s main attraction is a 24-inch telescope, though the observatory also operates a 15-inch telescope and several smaller portable telescopes that are used depending on the number of visitors.

The observatory opens its doors to the public on specific Fridays and Saturdays from late spring through early fall, depending on moon phases and weather. The observatory plans to release its schedule around late April, Luken said.

Midweek tours are available by appointment, but can be limited to school and other educational groups, according to the observatory’s website. The observatory also organizes a research science camp during the summer that hosts astronomers and students from across the West Coast.

After visitors park, the greeting center can provide details about the evening’s tour. As daylight fades, tour guides use the telescopes to point out constellations and other information about the celestial objects visible that evening.

There’s a U.S. Forest Service campground — Pine Mountain Campground — across the road from the observatory that’s available on a first-come-first-served basis. The camping area includes four drive-in spots for trailers up to 27 feet and 10 sites for tents. Facilities are simple; there’s an outhouse but no power hookups, water sources or trash services. There are no camping fees, and campfires are regulated according to the danger levels set by the Forest Service.

“You know, we’ve all been camping, and in the middle of the night came out of the tent and looked up. Your jaw drops at how incredible the Milky Way looks and the sheer quantity of stars. It’s always very impressive,” Luken said.

Luken recommends that guests arrive shortly after sunset. Arriving after 10 p.m. is discouraged. On clear, moonless nights, the 24-inch telescope can run until midnight, however depending on weather conditions or attendance, telescopes may close earlier. A donation of $5 is suggested.

Driving instructions: Take U.S. Highway 20 east from Bend. In approximately 26 miles, arrive at Millican (closed general store on the right). Just past the old store, turn right at the green Pine Mountain Observatory sign onto the gravel road. Follow the road south (no turnoffs) 8 miles to the parking lot. If arriving at night, use parking lights to avoid light pollution.

Taylor Bayly is a reporter for The (Bend) Bulletin.

On a gray cold morning in central Oregon, Barrett Hamilton watched his coworker, Olen Grimes, hand out warm clothing from the back of Taylor Center’s community outreach van.

“People suffering from addiction don’t care if it’s a felony or a misdemeanor. They’re gonna do it regardless,” he said. Chuckling in a self-effacing way he continued, “When I was using, I didn’t care. That’s why addiction is not good. We just don’t think about the consequences of our actions. Out here, our goal is to build trusting relationships so when people are ready go into recovery, they know we are here to help.”

The debate whether to recriminalize small amounts of drugs in Oregon may be over, for now, but many wonder if the state can meet the financial burden and work force required to combat surging rates of addiction and homelessness. Ranking among the highest rates of illicit drug use nationwide, Oregon ranks nearly last for providing access to addiction recovery and mental health treatment.

While Grimes pulled sweatshirts from plastic bins Barrett stated, “We bring our laptop with a hot spot. We help expunge criminal records. We help people apply for SNAP benefits and personal IDs. We help people get into shelters and recovery programs. By asking ‘What can we do to help?’ we let them choose what they need.”

Now 12 years sober, Hamilton is the program manager for Best Care’s new Taylor Center recovery resource center in Bend.

After decades of underfunding and divestment from addiction treatment resources, Hamilton is beginning to see the impact of the measure’s major funding efforts in his region. In addition to the Taylor center and outreach van, Measure 110 funded a sixbed sober living facility serving mothers before and after giving birth, and an eight-bed facility for men and women with Substance Use Disorder (SUD) going through medication-assisted treatment (MAT).

“Since we started our community engagement outreach a little more than year ago, over a hundred people have begun substance use disorder recovery,” Hamilton acknowledged.

Reflecting on their success, Hamilton credited the overlapping programs and systems intentionally designed to break the cycles of addiction and homelessness. Peer mentors who are in long term recovery have built strong trusting relationships.

“Having been there ourselves, we understand the challenges people face. In turn, they know they can trust us,” Hamilton said.

The low-barrier approach, including not requiring abstinence, lets people break the cycle of addiction on their terms. Working within a network of readily available services has reduced waiting times and provide detox and recovery services swiftly.

For Hamilton, the Center’s model is a welcome change to premeasure 110 mandates to push recovery, get people to meetings, and make them go to treatment.

“They were forced into it for one reason or another. The people I serve now, I get to see what they need in their life to better their life.”

Three hours away in Clatsop County, one out of every 40 individuals is homeless. With fentanyl flooding his region, Sheriff Matthew Phillips believes court-enforced treatment is needed to curb the rising tide of addiction in his county.

“The vast majority of us in Clatsop grew up together. We raised our kids together. We coached together. There isn’t a one of us who doesn’t have a friend or a relative or a co-worker who has struggled with addiction.”

For Phillips, criminalizing the startling influx of fentanyl and other drugs into his county, and using drug courts to mandate treatment, is a very important component to protect his community.

“Sometimes having a social statement in the form of a law about what’s appropriate behavior or not is a good thing. We need a line that says, this behavior is not acceptable. When Measure 110 decriminalized drugs it removed that bright line. The measure’s changes will help us reclaim that bright line.”

In Southern Oregon’s Jackson County, Rep. Pam Marsh (D) voted against Measure 110. Explaining her choice, she said, “There weren’t enough resources, statewide partnerships, and tools in place to prepare the health care and legal systems to effectively implement the new law.” She quickly added, “But, the system was broken long before Measure 110.”

Though these three have diverging views about criminalizing possession of small amounts of any drug, they all agree funding must be funneled into recovery efforts if Oregon is to effectively tackle the crippling rates of addiction, overdoses, mental health issues, and homelessness in towns throughout Oregon.

Marsh said Jackson County has been grappling with poverty, addiction, substance abuse and mental illness for decades.

“We have generations of people who have been born into addictive situations and not finding their way out. Young parents who are being treated in our pregnancy and addiction clinics are not new to addiction. They are people who grew up in addicted households. Unless we figure out some effective ways to just interrupt that cycle, it just continues.”

Marsh stated that if the state is going to reduce addiction, it must also address the underlying systemic issues pervasive in rural regions across the state. Citing Oregon’s increasing rates of homelessness and rent-burdened households often paying 30

to 40% of their wages for housing, Marsh added, “It’s hard to be stable when you don’t have money. When people’s lives start to topple and communities fragment, so does their ‘social capital’.”

Both Phillips and Marsh say this breakdown of “social capital” — the networks of generational relatives, school, churches and institutions providing stability — is in part due to the rise of fentanyl, underemployment, and changing demographics due to the lack of living wages in industry.

While drug criminalization efforts were debated and scrutinized, Rep. Rob Nosse, a member of the Joint Interim Committee on Addiction and Community Safety Response Oregon, expressed future-pending concerns. Driving past a homeless camp, watching people lean over burn barrels to stay warm, Nosse reflected on the financial demands needed to make a significant dent in skyrocketing rates of substance abuse and houselessness.

“The problem Oregon is really facing is that we’re not going to put enough resources into the treatment system to meet the moment. We need such a massive influx of cash, and then the workforce that that cash would support. And we just don’t have it. That’s what I’m worried about. We will pat ourselves on the back as legislators if we make a $300 million investment above what we’re already doing, and that is a drop in the bucket of what’s needed.”

Nosse prefers a more pragmatic, money-wise method. Echoing Hamilton’s community engagement approach offering low-barrier access to safe shelter and recovery, Nosse stated, “We have so many people who want treatment but can’t get in because we don’t have enough beds available. I think, let’s focus on those folks first. Provide safe shelter where there’s security and sanitation. Provide access to care. Give the resources to wean themselves slowly. Help people believe their circumstances can get better. I think that is where our limited dollars need to go.”

As rural towns struggle to quell the fentanyl overdoses and rising rates of addiction, the question remains whether the state has the financial resources and the human capital to meet the complex, immediate needs of addicts while also addressing deeply-rooted systemic issues within increasingly fractured communities.

Carolyn Campbell is a freelance writer.

Central Coast Food Web is making business easier for local farmers and fishersSTORY BY KYLE ODEGARD

Sara O’Neill, the co-executive director of the Central Coast Food Web, wants to make business easier for local farmers and fishers.

“Our producers need reliable and positive marketing experiences, and we’re going to create those so we have viable food businesses here,” she said.

As the owner of Euchre Creek Farm outside Siletz, Ore. — O’Neill raises sheep and cattle, and produces hay, wool, beef, produce and flowers — she’s familiar with those issues.

The food web recently started an online market for food grown or landed in Lincoln County. Six businesses are involved, and more are welcome, O’Neill said.

O’Neill is participating by selling beef.

“It’s a welcome thing for farmers like me that don’t have employees and don’t have the bandwidth to sit at the farmers market all summer,” she said.

The Central Coast Food Web also offers seafood processing and storage options for 10 fishermen and other businesses, including Local Ocean, a well-known restaurant and fish market on Yaquina Bay, and OoNee Sea Urchin Ranch.

The organization is developing a commercial kitchen space for residents to make value-added products.

The USDA recently announced a $376,000 grant, with a $102,000 match required, for the food web to expand its efforts.

While Lincoln County has a rich food culture — Newport is an Oregon seafood stronghold — it also has the fewest farms of any county in the state, O’Neill said.

That’s because it’s difficult to farm in an area of seasonal wetlands with 80 inches of rain every year.

Access to land also can be difficult, as most acreage is designated timber, and the housing market can be dominated by tourists and people seeking vacation homes.

“A lot of adaptable folks are putting in greenhouses to extend seasons,” O’Neill said.

Access to land also can be difficult, as most acreage is designated timber, and the housing market can be dominated by tourists and people seeking vacation homes.

Then there are elk herds that can devastate high value crops. “They can wipe out tens of thousands of dollars worth of product overnight,” O’Neill said.

Robust electric fencing is needed to keep elk away from vegetables and fruit.

“We can grow a lot here, but we do have these structural barriers that take time and money and expertise to overcome,” O’Neill said.

And there is demand for local, sustainable food from restaurants, residents and visitors.

“I want to match the really talented growers and harvesters and fishermen with some of those people who celebrate what they do,” O’Neill said.

She also hopes to educate people how to take advantage of seasonal food, including by maintaining a pantry and stocking a freezer.

O’Neill hopes the food web will build partnerships with other food hubs both in the Willamette Valley and along the coast, but she’s focused on Lincoln County.

O’Neill is originally from central Texas, where her family raised registered black Angus.

She said she found her way to Oregon “as fast as she could” and loves the coast.

“I’m really interested in the climate, this sort of tail end of that temperate rainforest is absolutely gorgeous. I don’t think there’s any more beautiful place I’ve ever been,” O’Neill said.

Kyle Odegard is a reporter for the Capital Press in Salem.

When Emily and Josh McGraw decided to open

The Studio Pendleton in 2022, the couple had a vision for what they wanted the business to be: an art supply store and gallery that offered classes for kids and adults and private functions like birthday parties and team-building events.

Their vision was clear, but the details of how to make that vision a reality were a little fuzzy.

That’s when they turned to the Small Business Development Center at Blue Mountain Community College.

“Cindy Henderson was our adviser, and she was great to help us knock through all the things that we needed to create our business plan,” Emily McGraw said. “I don’t have a business background or anything like that, so she’s been super helpful with that sort of stuff.”

The McGraws’ story is not an isolated one. Every year, entrepreneurs all over the state get help launching, managing and expanding their ventures from Oregon’s network of Small Business Development Centers, creating and sustaining jobs while boosting the state’s economy.

For new business owners like the McGraws, the assistance provided by the SBDCs (as the centers are known for short) can be a godsend.

“The business plan creation part was huge for us because it answered a lot of questions beforehand that we didn’t expect to run into,” Emily said. “But because we had our business plan and had that knowledge from the Small Business Development Center, we were kind of ahead of the curve when we ran into the questions that we did.”

The Small Business Development Center network was created by a law signed by President Jimmy Carter in 1980 with the goal of supporting small businesses and entrepreneurship across the country.

There are nearly 1,000 SBDCs around the nation with more than 40 across Oregon, including two serving the northeastern corner of the state: one housed at Blue Mountain Community College in Pendleton and the other at Eastern Oregon University in La Grande.

Many of the centers are affiliated with universities or community colleges. All advising services are free, and efforts are made to keep the cost of classes and training sessions as affordable as possible.

Many of the centers are affiliated with universities or community colleges. All advising services are free, and efforts are made to keep the cost of classes and training sessions as affordable as possible. Funding for the program is provided by the U.S. Small Business Administration in partnership with states, local governments and the host institutions.

The Oregon SBDC network’s core services include free, confidential advising sessions from experienced mentors on a host of issues, from business planning to analyzing cash flow, accessing capital and hiring good employees, among other things. The centers also offer free or modestly priced training sessions on topics such as tax planning, computer skills, bookkeeping and human resources.

The network’s Capital Access Team can help small business owners find the investment they need to grow, and the Global Trade Center can help connect them with international markets for their goods.

In 2022, Oregon’s SBDC network served more than 5,200 clients, held 623 training events attended by a little over 6,000 people, and helped launch 198 startups, according to the most recent annual report for the state. Businesses supported by the network created 719 new jobs and retained another 869 while accounting for $83.1 million in capital formation.

The two Small Business Development Centers in Northeast Oregon recently published their annual reports for 2023.

Over the past year, the Blue Mountain SBDC assisted in the creation of seven new businesses. It also counseled 108 startups and 121 existing businesses. Eighteen new jobs were created and 357 were supported, the center reported.

The center’s client list included 148 female business owners, 46 minorities, 26 Hispanics and 22 military veterans. Small businesses working with the center saw a sales increase of $691,189 and a capital infusion of $441,115 in 2023.

Eastern Oregon University’s Small Business Development Center, meanwhile, helped launch one new business last year while providing advising services to 56 startups and 29 going concerns. Its 85 clients included 46 female-owned businesses, 17 with minority ownership, and six apiece with Hispanic or veteran owners.

Businesses advised by the Eastern Oregon SBDC created five new jobs and retained nine more, reported a sales increase of $590,000 and experienced $2.7 million in capital infusion, according to the center’s 2023 economic impact statement. »

What makes small business such a big deal? Because, experts say, small business is a key driver of the economy, especially when it comes to job creation.

According to the most recent data from the Small Business Administration’s Office of Advocacy, the nation’s 33.2 million small businesses account for 62.7% of all new jobs created in the United States and 43.5% of gross domestic product.

Closer to home, the agency’s most recent profile for Oregon found that 99.4% of all businesses in the state fit the SBA definition of a small business (meaning fewer than 500 employees) and employed 893,405 workers, or 54.4% of all Oregon employees.

That’s a generous definition of “small business,” to be sure. But even really small firms play an outsized role in job creation, especially in rural areas such as Eastern Oregon, according to a September 2023 summary by Oregon Employment Department regional economist Tony Wendel.

Wendel’s analysis of economic data showed that roughly 93% of all private companies in Eastern Oregon (defined as Baker, Grant, Harney, Malheur, Morrow, Union, Umatilla and Wallowa counties) have fewer than 20 employees.

While the bigger firms employ more total people — some 59% of the region’s 60,600 private sector jobs are with companies that have 50 or more employees — that still leaves a big chunk of Eastern Oregon’s labor pool (41%) working for the area’s smaller companies.

Many Northeast Oregon entrepreneurs feel they were set up for success by training, coaching and tools provided by a Small Business Development Center. Having an adviser walking them through the process of writing a business plan, raising funds via loans or grants and promoting their new venture, they say, has been a key factor in getting their fledgling business off the ground.

Lee Chapman, owner of Blue Lotus Tattoo in Baker City, said the shop was her first foray into running a business.

“I was very new coming into this whole idea of starting my own small business,” she said.

The Blue Mountain SBDC helped arrange a grand opening and ribbon cutting for the startup.

“It was a really successful event,” Chapman said. “I feel like I had, probably, 50 people who showed up, which is way more than I expected.”

Chapman said her adviser, Jeff Nelson, helped her coordinate multiple social media platforms and provided training on marketing.

Nelson also helped Chapman improve her knowledge of Google Maps, Instagram and Meta to promote her tattoo parlor to potential customers. The SBDC supported her online presence and helped her manage her social media marketing in ways that avoid spreading her focus too thin.

“And then he’s also been really helpful at giving me information about possible grants,” Chapman added. »

Deana Tarantino took over an existing business in the Baker County community of Haines in January.

Stagecoach Gifts offers a variety of goods from local crafters, builders, small-business owners and others. Tarantino rents the space from the building owner and has 15 vendors who sell their wares in her store.

Nelson has been helping her home in on the areas she is good at and getting her help where she needs it.

“He’s awesome,” Tarantino said. “He streamlines it exactly for your needs and sends you what you need to learn those things and gives you the links to everything and helps hook you up with business planning.”

In addition to helping her get her new business off on the right foot, Tarantino said, she’s counting on Nelson to guide her through the process of hiring her first employees as the operation grows over time.

“He’s like your right hand guy,” she added, “and it is really nice to have somebody that I can be like, ‘I don’t get this, what do I do?’ ”

Like Chapman and Tarantino, McGraw said Small Business Development Center support was crucial in launching The Studio Pendleton. Not only did she and her husband get smart advice from the SBDC, but they also got smart tools, such as a software application called Live Plan to help flesh out a business plan and manage their fledgling enterprise.

“It’s a great program that integrates with a lot of things,” McGraw said. “It’ll integrate with your QuickBooks and everything, and it takes all the information that you’ve input

and then creates your business plan into a professional-looking document. (It) creates charts, projected profit-and-loss statements and everything.”

And the assistance didn’t stop once the business opened its doors. According to McGraw, her SBDC adviser has continued to provide wise counsel on tax issues, accounting procedures and other areas where she needs help.

Energy Trust of Oregon offers cash incentives for energy-efficient equipment installations and property improvements. Upgrades can lower energy use so you can save money!

Learn more at www.energytrust.org/existingbuildings

The number of Oregon farms and ranches has dropped, but the state’s agricultural industry remains dominated by family-owned and -operated businesses, according to the USDA’s 2022 Census of Agriculture.

The ag census showed 35,547 farms and ranches in Oregon, down 6% from 2017.

Family businesses accounted for 96% of all Oregon farms and operated 84% of ag land.

Overall, farms covered 15.3 million acres of farmland in 2022, down 4% from 2017.

Despite the decrease, that still represents 25% of the land in the Beaver State.

The average size of Oregon farms and ranches grew 1% to 430 acres.

Oregon farms and ranches produced $6.77 billion in agricultural products, up from $5.01 billion five years ago.

With expenses of $6.35 billion in 2022, Oregon farms had net cash income of $930 million.

Average farm income rose to $26,172, and 31% of Oregon farms had positive net cash farm income in 2022.

Oregon farms with internet access rose slightly, hitting 88%, up from 86% in 2017.

About 3,500 farms and ranches used renewable energyproducing systems, a 23% increase over five years before. Of those ag operations, 90% reported using solar panels.

In 2022, 4,550 Oregon farms sold directly to consumers, with sales of $117 million. The value of sales increased 38% from 2017.

More than 1,200 Oregon farms, or roughly 3%, had sales of $1 million or more. Those farms sold 76% of all ag products in the state.

The average age of all Oregon producers was 58.6, up 0.7 years from 2017.

About 21,900 Oregon farmers had 10 or fewer years of experience, a 14% increase. Beginning farmers had an average age of 48.2.

Oregon farms and ranches produced $6.77 billion in agricultural products, up from $5.01 billion five years ago. With expenses of $6.35 billion in 2022, Oregon farms had net cash income of $930 million.

Almost 4,900 Oregon producers, or 7%, were under age 35.

The 3,709 Oregon farms with young producers making decisions tend to be larger than average in both acres and sales.

In 2022, 30,150 female farmers and ranchers accounted for 44% of all Oregon producers. Seventy-six percent of all Oregon farms had at least one female decision-maker.

Our family of organizations needs your help to continue building relationships and getting things done in the Mid-Columbia region of Oregon

The Northeast Oregon Water Association (NOWA) formed in 2012 to build and enhance relationships with Oregon agencies and legislators in support of our sustainable natural resourcebased economy that generates billions annually for the region, state, and nation. The founding members of NOWA include the counties, cities, ports, private businesses, and landowners of the region who mutually committed to a list of solutions to move the region’s water sustainability goals forward. These relationships have yielded the following results over the last 10 years:

$25 million in state investment since 2015 into three regional Columbia River pipeline projects. This funding has led to over $200 million in private infrastructure investment in the region.

Certification and Protection of existing water rights for cities and private citizens, and development of the first mitigated Columbia River water rights in Oregon history.

$1 million in state investment to develop the first basalt groundwater savings and banking program in Oregon history.

Pressure on agencies to address elk depredation, impacts of energy transmission development, and impacts of baseless policy changes on irreplaceable irrigated land in the MidColumbia region.

In addition to state and federal efforts, NOWA has fostered local efforts to create capacity to keep the region moving forward. These efforts have led to the formation of the MidColumbia Water Commission to administer Columbia River efforts and the SAGE PAC, which advocates for our region and our sustainability needs.

Together these organizations will work on the following to advance short and long-term goals of the region:

The next 7 years of work to sustain our next 7 generations

1) Tell OUR story and prevent rogue agencies, extreme interest groups and legislators from pushing misinformation and half-truths that cloud the economic and environmental sustainability goals this region has invested in and fought hard to preserve for decades.

2) CONTROL our agenda, and minimize reliance upon outside groups that may or may not have our best interests in mind.

3) CONTINUE progress on groundwater quality remediation strategies and get our region out of the legacy issue of nitrates in groundwater.

4) PROTECT landowners and local communities from over-regulation and baseless policy changes.

5) ADVOCATE for sound, peer reviewed data in statewide decision making so we all know where we are and where we need to go.

6) FINISH the Plan to secure permanent Columbia River mitigation water through investments in policy and projects in Oregon and in our neighboring states.

7) FACILITATE a funding program for recharge testing and groundwater banking in Morrow and Umatilla Counties.

We need your financial support to build the relationships to move our region forward

To learn more about how you can help NOWA, be a part of the sustainability movement or donate to the efforts please contact J.R. Cook, NOWA Director at jrcook@northeastoregonwater.org

Stefano Tighe can often be seen sitting courtside at Astoria, Warrenton and Seaside basketball games, where parents, players and others come by to shake his hand.

Tighe has become a fixture in the local sports scene, taking on the role of mentor for many young athletes.

Either through parents reaching out or by reputation, Tighe has around 70 young people in and out of his home hair studio. He started cutting his own hair in 1990 and has made it into his business.

“I retired fully in 2020, so I do everything for free,” Tighe said. “Sometimes kids on their first visit try to give me a tip, but I don’t take it. I want to teach these kids the right way to do things, and something like free haircuts and a mentorship is something I hope these kids will understand more as they get older.”

Tighe was born and raised in Astoria and attended St. Mary’s, Star of the Sea School and Astoria High School. He joined the U.S. Navy in 1989 and served until 2010. But it was a back injury in a boating accident two decades ago that led Tighe to his real passion.

the NFL reached out wanting to see where the Buffalo Bills safety grew up.

He spent his last several years in the Navy as a counselor in recruiting offices, building connections with young men who were considering the military. He realized this work was what he enjoyed.

“Kids have so many more distractions today,” he said. “When I grew up it was just skateboards and bicycles, but kids now have access to all kinds of technology, which in my opinion has made it much harder for them to enjoy life. I take it upon myself to be a mentor for these kids and help them stay on the right path and enjoy this community.”

Tighe likes being a bridge between so many different athletes. Young people from Seaside, Warrenton and Astoria might text him about upcoming games they want him to attend, while parents will approach him with updates on how their children are doing.

Something else that Tighe enjoys doing is giving tours of the city. He told a story about how one of Jordan Poyer’s friends from

“I want to give a tour of Astoria through my eyes,” Tighe said. “As someone who’s lived in a number of different places, there’s no place like Astoria and the Oregon Coast. I’m proud to be a ‘Goonie’ and want to share that experience with anyone who reaches out.”

While the Navy showed him different places, Tighe was drawn to home, and he moved back to Astoria for good in 2020.

“My daughter (Ava) wants to graduate from my alma mater,” he said. “I’m also someone who plays a lot of golf and whoever I end up playing with, I will make it a point to promote their business and just spread love to everyone I encounter.”

Tighe’s message is simple: always be positive.

“We’ve got a bad enough world already, so the goal for me is to be positive and understand how lucky we are to live in Astoria,” he said.

Paul Matli is a reporter for The Astorian in Astoria.

This solar project helped keep a family ranch profitable during the 2021 Bootleg Fire, when alfalfa and beef prices collapsed.

Renewable energy projects not only create clean energy, they give family farms and ranches long-term fixed income sources to blend into their finances — and protect them when there’s a drop in commodity prices or a spike in diesel and fertilizer costs. NewSun Energy’s investments in Lake and Harney Counties do good things for their communities:

▶ Local Jobs. Local Contractors. Local Benefits. Over $50 million in rural wages paid on four projects; filling local restaurants and hotels; and millions spent with Central & Eastern Oregon contractors, consultants, shops, and suppliers.

▶ Tax Income for Cash-Strapped Rural Counties. $560,000 in annual property tax revenue funds rural services and county governments.

▶ Community Investments, College Scholarships. Harney District Hospital Specialty Care Clinic; Scholarships; FFA and 4H auctions; Food Share roof project; public art; resurfacing county roads; and much more.

To learn more about NewSun Energy’s community benefits program, or apply for NewSun’s 2024 Climate Change & Agricultural Communities Scholarship opportunities, email us at communitybenefits@newsunenergy.net.

Oregon Farm Bureau is the state's most inclusive agriculture organization, representing about 6,300 family farmers and ranchers who raise everything from cattle to hazelnuts. First established in 1919, Farm Bureau is a grassroots, nonprofit organization representing the interests of family farmers and ranchers in the public and policymaking arenas. We aim to keep agriculture thriving for future generations, expand its economic opportunity and viability, and educate society about why ag is important.

Our policy and political priorities develop from a democratic process, beginning at the county level. Positions, ideas, and initiatives then make their way to the OFB annual convention, where Farm Bureau members from around the state meet to discuss and vote upon the organization's goals for the coming year.

MORE THAN 97% OF OREGON FARMS AND RANCHES ARE FAMILY-OWNED AND OPERATED.

NEARLY 1 OUT OF EVERY 8 JOBS IN OREGON RELIES ON AGRICULTURE