Imet Nella Mae Parks more than six years ago at Oregon State University’s Small Farm Conference. She was a young farmer from Cove, Ore., who was also a freelance writer interested in doing stories for Capital Press, our agriculture publication.

We spoke briefly, but long enough for her to give me her back story. After college and a stint in the wider world, she returned to Cove with her husband to take over part of her family’s farm.

After we started The Other Oregon, I was looking for someone young and smart who could talk about the rural-urban divide from the perspective of a rural Oregonian who left and came back. She was apprehensive at first, but she came around once I explained why we thought it important to tell the story of rural Oregon from the point of view of people who live there.

It was something she had felt for a long time, and she thought she’d have something to contribute. She’s been working to bridge the rural-urban divide through her essays ever since.

When we spoke shortly after the election, her thoughts were on the partisan divide that splits communities, families and friends across the state.

Her solution: Find trust and understanding by joining your neighbors to work on the little problems close to home. National electoral politics doesn’t mean a hill of beans when you’re trying to get a pothole filled.

Kathryn Brown is no longer publisher of The Other Oregon. She took on the role shortly after we started the magazine. She was one of the owners of EO Media Group, the family newspaper company that traced its roots to 1908 and the East Oregonian in Pendleton.

The company has been sold, and so Kathryn takes her leave. I will miss her enthusiastic support of The Other Oregon and its mission. — Joe Beach

The Other Oregon is distributed to 5,000 influential Oregonians who have an

Editor/Publisher Joe Beach

Contributors

Editor/ Publisher Joe Beach, jbeach@eomediagroup.com

On the cover: The Tillamook Creamery is one of the top tourist attractions in Oregon with 1 million visitors in 2023. PHOTO BY KYLE ODEGARD

Published by The Other Oregon © 2024 POSTMASTER: Send address changes to The Other Oregon, P.O. Box 2048, Salem, OR 97308

in connecting

Oregon. As we strive to close the urban-rural divide, please help us with a donation. If you are a business leader, you can support our efforts by advertising to

audience. To subscribe: TheOtherOregon.com/subscribe. For advertising information: TheOtherOregon.com/advertise

STORY & PHOTOS BY KYLE ODEGARD

The Tillamook County Creamery Association has enjoyed a rapid rise from regional dairy brand to national powerhouse, with annual sales jumping nearly 250% to more than $1.2 billion in the past decade.

Executives said the cooperative isn’t done growing, but expansion already has provided stability for its 60 dairy farmers on the Oregon Coast.

“It’s making small farms sustainable, where a lot of other places throughout the country, small farms are struggling,” said Shannon Lourenzo, a farmer who is chairman of the association’s board of directors.

TCCA members get consistent pay that doesn’t follow the ups and downs of the market, Lourenzo said.

Tillamook farmers have always dealt with wet weather and higher hay and fuel prices, since goods have to be hauled to the northwestern Oregon coast.

Add in the recent inflation, rising interest rates and record feed prices and the dairies were under pressure.

Increased co-op distributions helped smooth out the downturn, Lourenzo said.

“Without that growth, we wouldn’t have been able to keep up,” he added. “That’s where the power of the brand has really got us through this.”

The TCCA formed in 1909 with 10 independent dairies each chipping in $10 and using a cheese recipe with just four ingredients that’s still followed today.

The cooperative is still owned by its farmers and has added ice cream, butter, cream cheese spreads, yogurt, sour cream and frozen meals to its lineup.

In 2012, when Patrick Criteser started as CEO and president, challenges were mounting.

Every day, the Tillamook Cheese Factory brings in 1.8 million pounds of milk and produces roughly 170,000 pounds of cheese.

Though cheese remains Tillamook’s top category, ice cream has grown faster in the past decade. The cooperative has made ice cream since the 1940s, but there was little distribution outside the Northwest until recently. CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

The TCCA formed in 1909 with 10 independent dairies each chipping in $10 and using a cheese recipe with just four ingredients that’s still followed today. The cooperative is still owned by its farmers and has added ice cream, butter, cream cheese spreads, yogurt, sour cream and frozen meals to its lineup.

“Being only regional wasn’t going to produce the growth or financial security needed to support the dairy families of Tillamook,” said Criteser, a sixth-generation Oregonian with experience at Nike and Disney.

Larger retailers had expanded nationwide and it was increasingly difficult to compete on a regional scale.

Leadership positioned Tillamook cheese as a premium yet accessible product, with more cream and natural aging. They believed consumers would recognize the value, pay more and put Tillamook in their shopping carts every week.

“We kind of tested our strategy first in what we called ‘Win the West,’” Criteser said.

The higher price point and additional regional distribution worked, and proceeds were reinvested in the brand.

“In 2018 we decided to pursue a national footprint,” Criteser said. That included the rollout of a new logo and packaging makeover. »

The Tillamook County Creamery Association’s nationwide expansion has helped make small dairy farms sustainable on the Oregon Coast, said Shannon Lourenzo, chairman of the cooperative’s board of directors.

Typically, big growth brands have introduced something new, TCCA leadership said. The cooperative, meanwhile, made traditional products, targeted mainstream success and pushed into new markets.

Introducing a new brand to consumers is expensive and risky, Criteser said.

“It was not a foregone conclusion or straightforward that we would be able to almost triple the business in a decade,” he added.

Today, Tillamook is the fastest-growing cheese, ice cream and cream cheese brand in the country. Nearly 1 in 4 U.S. households buy Tillamook products.

On top of that, there’s still growth potential across the nation that will make margins better, Lourenzo said.

Success has allowed the TCCA to make new and larger investments. In early 2025, the cooperative is opening a new plant in Decatur, Ill., that will employ 45 people.

“That will be our first facility that just makes ice cream,” said David Booth, who became Tillamook’s new CEO and president this summer.

He’s been with the cooperative for about a decade, and his previous role was as Tillamook’s executive vice president of brand growth and commercialization.

Though cheese remains Tillamook’s top seller, ice cream sales have grown faster in the past decade.

The cooperative has made ice cream since the 1940s, but had little distribution outside the Northwest until recently, Booth said.

The cooperative recognized ice cream products as a growth segment and a gateway to other dairy categories.

Booth said the new Illinois plant is the next logical step in Tillamook’s growth, as it puts a supply chain underneath national distribution.

Three Tillamook managers from Oregon moved to Illinois to start the facility, bringing with them the cooperative’s culture and values.

The Decatur facility is Tillamook’s third plant and its first outside Oregon.

The Tillamook Cheese Factory operates on Highway 101, just north of the city of Tillamook.

In 2001, the cooperative opened a new plant at the Port of Morrow in Boardman, Ore.

That Eastern Oregon facility brings in milk from partners such as Threemile Canyon Farms, the state’s largest dairy, as well as Darigold cooperative farmers.

Tillamook also partners with contract manufacturers to make some of its products.

Booth said additional plants will create more efficiency for TCCA and a better return for dairy farmers.

But the cooperative won’t make wild bets, and more measured growth is the goal, he said.

Booth said it was better to think of Tillamook as adding depth rather than expanding during its next decade.

The brand won’t stray from its dairy footprint, but needs to leverage growth that’s already occurred, he added.

There are also possibilities with new domestic sales channels and international markets.

Convenience stores are a target, and Booth said the cooperative can utilize its success with cheese for snack products. Tillamook also recently launched pint-sized ice cream cartons.

TCCA has a small international presence, but Booth believes the brand can expand outside the U.S.

Criteser said U.S. and Northwest dairy products have an advantage internationally, thanks to their reputation for quality.

Tillamook also already has a positive reputation as well, said Erick Garman, Oregon Department of Agriculture trade manager. “As they look to expand into international markets, they are already known and respected by importers and distributors, even without a significant export presence,” he added.

Marcia Walker, director of Oregon State University’s Food Innovation Center in Portland, said Tillamook’s national impact brings attention to Oregon’s food and beverage sector.

Tillamook helps build and is emblematic of Oregon and the Pacific Northwest’s identity as a region that produces premium but approachable agricultural products.

The co-op also touts Oregon ingredients such as berries in its ice cream and other value-added products, reinforcing the region’s bounty, Walker said.

Walker said Tillamook has set trends for other companies to follow with exciting flavors that have become mainstream.

“Pepper Jack was considered a specialty cheese, and now you can buy the big 2-pound block of it. It’s simple innovation like that, but it’s paying big rewards,” Walker said.

Tillamook’s sales climb is significant, but so is the brand loyalty.

“It would be different if it was a company that people didn’t care about, but Tillamook is really well-regarded and wellrespected,” Walker said.

The cooperative has won a plethora of awards for its cheeses and pushed into the super premium ranks with some products.

Tillamook’s upswing brings other benefits for communities. The cooperative has 1,100 employees, up 69% from 2012.

It’s also a tourism driver, philanthropic force and environmental leader on the coast, said Nan Devlin, executive director of Visit Tillamook Coast. »

EIzzayah Dobbs, 9, of

Ore.,

Tillamook increased environmental initiatives under Criteser’s leadership, adopting a stewardship charter in 2017.

That was partly to meet consumer expectations, but TCCA farmers care deeply about their impacts, Criteser said.

In 2020, Tillamook became a certified B Corporation for its efforts to save water, improve animal welfare and assist communities battling the COVID pandemic.

The Tillamook Creamery visitor center is one of the most popular tourist attractions in the state, with 1 million visitors in 2023.

That helped drive nearly $300 million in visitor spending for Tillamook County in 2023, creating ripples throughout the local economy, Devlin said.

“It’s huge,” she added.

Every day, the Tillamook Cheese Factory brings in 1.8 million pounds of milk and creates roughly 170,000 pounds of cheese — workers on the production floor are watched by guests from throughout the country.

Abel Adams, 7, of Hillsboro, Ore., likes finding new license plates, and the visitors center parking lot was a bonanza with vehicles from Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan and elsewhere.

“There are so many different ones here. Even Canada,” exclaimed mom Lacey Adams.

Married couple Morgan Bernard and Craig Morgan of Port Townsend, Wash., were on a beach vacation and purchased 2012, 2014 and 2017 editions of Tillamook Maker’s Reserve Cheddar Cheese.

“We try to buy things here we can’t find anywhere else,” Bernard said.

Visitors also can get ice cream and other food, pose at photo stations and purchase Tillamook branded apparel.

During a guided tour, guests laughed upon learning Tillamook County has more cows (30,000) than people (29,000).

The number of cows and acreage has stayed steady, but TCCA farmer members declined by about 30 in the last five years.

John Seymour of Cloverdale, Ore., a fifth generation farmer whose family helped form the cooperative, said that’s because of retirements.

“I don’t see farms going out of business because of financial stress here. It seems more aging out, and their sons and daughters don’t want to do it,” said Seymour, a TCCA board member and chairman of the Oregon Beef Council.

“The next, best person to purchase their land and continue the operation is a neighbor,” Seymour added.

His family’s dairy farm grew that way.

Farmers might experience rough patches and new challenges such as new state overtime regulations and avian influenza, but dairies are more likely to survive in Tillamook County, Lourenzo said.

Because the cooperative grew organically without outside capital, TCCA’s expansion feels solid, he added.

The succession also has gone smoothly and was well received because leadership transferred from a long-tenured CEO to a familiar executive, Lourenzo said.

The future looks bright for Tillamook and its farmers — even with 100 inches of rain every year — and expansion is a major reason.

“There is nobody that has done or is doing what we’re doing as far as the growth and the distributions for members,” Lourenzo said.

Seymour discussed how farms evolve and adapt to thrive, how his grandfather installed one of the first milking parlors in the area, how his parents were pioneers with intensive rotational grazing systems.

“As a farmer, I have to grow, innovate and be more efficient, and challenge the status quo to survive. I think our co-op is the same way,” Seymour said.

“We’re going to have to keep going and moving into the future,” he said.

Kyle Odegard is a reporter for the Capital Press.

With the completion of its state-of-the-art 8,000-square-foot community makerspace, Talent Maker City (TMC) is poised to become Southern Oregon’s center for inspired innovation.

Based in Talent, Oregon, the $4.4-million building sits on the lot where commercial buildings burned to the ground during the 2020 Almeda Fire. Talent Maker City’s new makerspace will serve communities throughout southern Oregon offering STEAM-based education (combining science, technology, engineering, art, and math), as well as classes and programing to strengthen creative and economic innovation.

The Maker Movement, which emerged in the U.S. over a decade ago, features community-based maker spaces that encourage people to create, share, and learn through making. Designed to cultivate creativity and collaboration, and inspire innovative solutions, Talent Maker City provides space, tools, and resources to better equip southern Oregon communities with the skills to participate in a rapidly changing global economy.

“I still choke up a bit when I walk in the building,” said Executive Director Alli French. “After the Almeda fire ravaged downtown and displaced many from our most vulnerable communities we wanted to bring hope to those who lost so much and provide more programming and support for our struggling region.”

In 2021, as part of American Rescue Plan Act Funding passed through the state legislature for specialized projects in communities throughout Oregon, TMC received a $1.8 million grant directed by Rep. Pam Marsh. An ardent supporter of the TMC, Marsh believes Talent Maker City’s ability to listen to diverse voices of the community has enabled them to become a regional hub for creativity, collaboration, and innovation. “Talent Maker City is kind of the soul of Talent in some ways,” she said.

Project costs, including solar panels for the roof, a public art walkway, and a welding studio, total $4.4 million. In 2023, Talent Maker City launched an ambitious capital campaign to raise $2.5 million to purchase a higher-powered laser engraver, a water jet cutter and a large CNC machine, which uses preprogrammed

Talent Maker City’s new makerspace will serve communities throughout southern Oregon offering STEAM-based education (combining science, technology, engineering, art, and math), as well as classes and programing to strengthen creative and economic innovation.

computer software for machining metal and plastic parts. To generate curiosity in the trades, some walls were made of Plexiglas instead of drywall so visitors can see how things are put together. Formulas for concrete were stamped into the floor.

A month after the opening, French celebrated the support of the community.

“We couldn’t have created such an amazing space without generous donations from our community, builders and suppliers. The building is a bit larger than we initially planned but the community wanted us to design a maker space that honored the agricultural history of our community while still providing us space to grow. We are on track to have loans paid off within the next few years.”

This ‘can do’ attitude is at the heart of Talent Maker City’s

mission. Reflecting back on Talent Maker City’s inception in 2016, French took a moment to acknowledge the creators who started the maker space.

“After our four founders wrote a proposal, our Town of Talent was named an official Etsy Maker City — one of just 13 invited to their inaugural summit.”

In 2017, TMC began running STEAM-based maker workshops for middle and high school youth at schools from Talent to Grants Pass. Workshops for adults were held at wine bars, goat farms, and Ashland High School. By 2018, they’d leased a 3,700-square-foot space in downtown Talent offering public workshops, after-school programs, and Summer STEAM Camps. »

When the COVID-19 pandemic closed their doors, TMC pivoted. 3D printing machines churned 24 hours a day printing face shields, ventilator parts, and other personal protective equipment (PPE) for local hospitals.

Less than a year later, after the 2021 Alameda fire displaced a third of the town’s residents, Talent Maker City pivoted again.

To address the housing crisis and ongoing gaps in student learning, the maker space partnered with Medford local schools and The Skoolie Home Foundation. Working with Career Technical Education (CTE) educators and industry experts, students converted two retired school buses into homes for families displaced by the fire.

Partnering with Girls Build, TMC hosted free workshops to build wooden bed frames. In collaboration with Phoenix-Talent School District, and Phoenix-Talent Rising Academy (PTRA), middle school students built bookcases, picnic tables, benches, planter boxes and stairs for RVs where survivors are staying.

Kathy Deggendorfer, an eastern Oregon resident and founder & trustee of Roundhouse Foundation, became aware of the work of TMC in the aftermath of the Alameda fire. Struck by French’s ability to identify and articulate a need and use art, technology, and creativity to bring people together to recover their community, Deggendorfer compared TMC’s approach to regenerative agriculture.

“Alli and her team were able to take quick action and serve the needs of those most impacted. That’s what we need in rural

communities, people who take a step forward, even if you fail. If it doesn’t work, you learn something. And then you build something else. You try to see what plants work in your soil and adapt to the needs at hand.”

As crisis after crisis befell her region, French and TMC pivoted and kept pivoting, kept offering new programs, believing a connected, prosperous, and resilient community gets stronger by making things together.

Today, the little corner of Talent devastated by the Almeda Fire of 2020 is starting to show signs of hope and growth. Humbled by the outpouring of support, French stated, “We’re already seeing a huge spike in numbers as people participate in our public workshops. We’re growing new partnerships with organizations including the Oregon Spinal Cord Injury Connection (OCSI) while expanding programming for current partners including Maslow Project, Rogue Food Unites, Jackson County Juvenile Justice, and Southern Oregon University. We want our new maker space to create a place of belonging where people not only learn new skills but get to know their neighbors, to find out new ideas, to talk about life, and collaborate in ways we haven’t yet dreamed of. If there’s anything we’ve learned over the last few years, it’s that the only way to get through all the challenges facing our region is to work together.”

To find out more, visit TalentMakerCity.org.

Carolyn Campbell is a freelance writer.

STORY BY CLAYTON FRANKE • PHOTOS BY DEAN GUERNSEY

att Wiederholt remembers the boom days of the sawmills in Prineville.

Trucks hauled logs out of the Ochoco National Forest to seven mills in town. Multiple trains a day rolled through town, blowing a whistle every morning at 5 a.m., on the short 18-mile track to the Redmond switchyard and beyond.

“Growing up in Prineville, the railroad was just always there,” Wiederholt said.

Those logging boom days are long gone. But the city’s railroad never faded away, and the city is set to make a multimillion-dollar investment as it continues to evolve.

“It’s neat to come full circle,” said Wiederholt, Prineville’s railroad manager.

The City of Prineville Railway is the oldest continuously operated municipal short line railroad in the United States. With a recent $1.6 million federal grant and $400,000 of its own funds, the railroad will purchase equipment for maintenance and preservation. City crews will also replace 10,000 railroad ties — about one-sixth of the line — after moving through with the equipment to tamp and level the tracks.

“What’s really exciting is it’s going to allow us to purchase equipment to maintain our line, equipment that we don’t have right now,” Wiederholt said.

That will allow the railroad to be more self-sufficient without having to rely on subcontractors. City and railroad officials are confident the investment will keep the railroad on a rising trajectory 20 years after Prineville considered cutting ties with its beloved asset.

Wiederholt joined the Prineville Railway staff in 2004 during some of the railroad’s darkest days.

That year the railroad sent an all-time low 87 cars from Prineville to Redmond, a fraction of the historic highs of the ’60s and ’70s, when more than 10,000 cars left the depot each year, mostly filled with logs. At the low point, Prineville-based Les Schwab Tires was the sole client of the railroad.

Prineville historian Frances Juris writes in a history of the railroad that city officials wrestled with the dilemma of what to do as financial reserves dwindled, and considered both selling and scrapping it.

At the turn of the 20th century, Prineville, population 600, served as the economic hub of Crook County, which at that time included all of what’s now Deschutes and Jefferson Counties as well. That changed about 10 years later when the Oregon Trunk Line, the main railroad in Central Oregon now operated by BNSF Railway, bypassed Prineville, connecting instead to Redmond and Bend.

City leaders feared Prineville would become a ghost town without access to the trunk line. Voters overwhelmingly approved a bond to fund the construction of a city-owned short line to Redmond, and the railroad was operational in 1918.

Some ups and downs followed, but by the 1950s the railroad was so prosperous from log shipments the city built parks, a swimming pool and a city hall, and started to build reserves.

For five years in the 1960s, Prineville residents paid no property taxes because of revenue from the railroad.

Juris chronicled the railroad’s importance: “Without the city of Prineville Railroad, the timber from the Ochocos would have been hauled to Redmond, and Prineville would surely have met the same fate as Shaniko and Antelope.”

But the timber industry didn’t last. Prineville-based Ochoco Lumber Co. shuttered in 2001, taking with it more than half of the railway’s business.

“We knew we were losing money; there was no question about it,” said Steve Uffelman, who has served on the Prineville City Council and city railroad commission since 1985. “The question was, what do we need to do to get it to essentially reinvent itself and find a means to regenerate a revenue stream.”

In a pivotal move, the city swapped land with an old sawmill along the railroad, acquiring two new warehouses. That gave shippers a place to store product at the freight depot, and the railroad no longer had to run tracks to each separate business.

The model took off, and the railroad piled up $9.4 million in state grants over the next several years to build two more warehouses.

“By building the warehouses and the transload facility, somebody down the street, they can bring the product to us and they can take advantage of that bigger transportation web and be more competitive on the national level by using rail,” said Wiederholt, who was tasked with managing the new facility in 2004 and took over as railway director in 2013.

Today the railroad serves 34 businesses and runs more than 1,000 cars a year, a little more than one-tenth of its historical traffic.

A small portion of cars still carry lumber, but the railroad has survived by diversifying its cargo: raw materials for asphalt and deicer, barley for breweries, materials for truss and pipe manufacturing and others.

“Golf course sand comes by rail. Who would’ve thought we would’ve been bringing in golf course sand?”

Unlike the old days, most of the product is inbound, not

outbound, to Prineville, where businesses have set up shop because of the rail access. Products come from as far away as Mexico and Canada, Wiederholt said.

Wiederholt estimates those businesses have brought about 200 jobs to Prineville.

Businesses that rely on efficient logistics and supply chains are particularly interested in shipping with the railroad, said Kelsey Lucas, Prineville director for Economic Development for Central Oregon. Rail is ideal for rural areas, where shipping distances are longer and loads are larger, she said. Rail prevails when snow and ice cover Central Oregon and the mountains or congestion blocks car traffic, she said.

Along with the proper infrastructure, Uffelman said, the railroad’s level of customer service has put Prineville on the map.

Though it’s growing, Prineville was, and still is, a blue collar community — largely due to the railroad, he said.

“Let’s face it, that’s what we are,” he said.

“We provide resources so industry can move in and provide jobs, family-wage benefits and full-time jobs, so that people can afford to live and raise their families. That’s what this town was 40 or 50 years ago when there was a timber industry.”

The railroad is not close to returning to the point where it could subsidize Prineville’s property taxes. But it pays for its own maintenance and operation — including matching funds for the recent grant — and contributes to paying city administrative salaries.

City leaders see a bright future for the city’s old railroad. Uffelman sees it as key support for a planned $120 million biomass facility in Prineville, which he said will rely on rail shipments of woody debris from across the state and region to be burned for energy.

STORY & PHOTO BY JAYSON JACOBY

ne of Baker City’s beloved Christmas traditions — a giant, lighted cross — was sprawled across a good portion of Mike Voboril’s shop on the second morning of December.

The sunshine was bright, the sky unblemished.

But it’s what would happen several hours later, when the sun descended behind the sagebrush-studded ridge that rises above, and the chilly dusk fell, that Voboril was thinking about.

It’s why he felt a bit of pressure to finish the task he’d set for himself.

It’s a job that involved more than 40 feet of aluminum and galvanized steel pipe.

More than 250 feet of plastic tubing studded with bright white lights.

Dozens of pieces of copper wire.

When Voboril twisted the last wire on Dec. 4, snugging the final section of lights in place, he got in his forklift and haul the cross to its perch a couple hundred feet above his home.

Soon after, the cross brightened the winter sky, a beacon visible across Baker City and beyond.

Voboril, who has lived in Baker City since 1984 and on his property above the drinking-water reservoir at the southwest corner of the city since 1989, assembled the cross many years ago.

Each year during the Christmas season, and again for Easter, he switches on the lights.

In 2020 the cross was lighted much of the year.

His original inspiration, and what continues to motivate him, is simple.

“I thought it would be nice to have something that gave us a little bit of peace,” Voboril said.

This year he turned on the lights a couple days before Thanksgiving.

But there was a problem.

Only one strand of lights was illuminated.

Voboril quickly diagnosed the issue — and it wasn’t a new one.

When the company that owned the tower told Voboril they intended to remove it — it stood on his property — he asked if they could leave it. He said he had been thinking about building a lighted cross.

CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

Although the lights are encased in flexible plastic tubing that’s supposed to defy the weather, the material isn’t as durable as Voboril would prefer.

“Water gets in, and that causes problems,” he said.

He pointed to a section of tubing that is scorched black rather than translucent.

Moisture, of course, does not mix well with electricity.

(A subject on which Voboril is an expert — he has installed and repaired electric pumps for wells, irrigation systems and other purposes for more than four decades. He sold the pump part of his business, MMW, about a year ago, but continues to repair motors.)

Voboril said water that seeped into the tubing caused an electrical short that in one place actually blew apart a section of lights.

The damage required replacement rather than repair, so Voboril took down the cross and hauled it to his shop.

The first spool of new lights arrived on Nov. 30.

The following Monday morning the dismantled cross was in Voboril’s immaculate shop.

The aluminum tower, about 35 feet tall, that forms the upright part of the cross was installed for an antenna for wireless internet, Voboril said.

When the company that owned the tower told Voboril they intended to remove it — it stood on his property — he asked if they could leave it.

He said he had been thinking about building a lighted cross, knowing that from its lofty vantage point it would be visible to almost all parts of Baker City.

Voboril said he had to sign a liability release, but the tower remained.

He built the crosspiece from sections of electrical metal tubing, which is made of galvanized steel and is used to protect electric wires.

Given his longtime business, Voboril had plenty of the material in his shop.

At first he attached the tube lights with electrical tape.

But he later replaced the tape with copper wire, which is more stable and also makes it easier to maintain equal spacing between the rows of lights.

Voboril said he would prefer not to have any publicity about his cross.

But he understands that Baker City residents anticipate its return each year.

When his wife, Andie, posted on Facebook on Nov. 26 that the cross was down but would be back once her husband installed new lights, there were more than 200 reactions to the post in less than a day.

Voboril has quite a different perspective of the cross than people down in the city, of course.

But he said he enjoys the view when he’s in town.

More important, though, he’s gratified that the cross pleases people.

“It makes me happy that it makes somebody else happy,” he said. “It gives me a nice, warm feeling.”

Jayson Jacoby is the editor of the Baker City Herald.

• Data-driven insights

Content development •

Targeted messaging •

Predictive analytics •

• Sentiment analysis

• Influence mapping

• Policy tracking

Artificial intelligence is the future, and it’s here. That’s why our team is earning certifications to harness the power of A.I. technology and meet our clients’ needs.

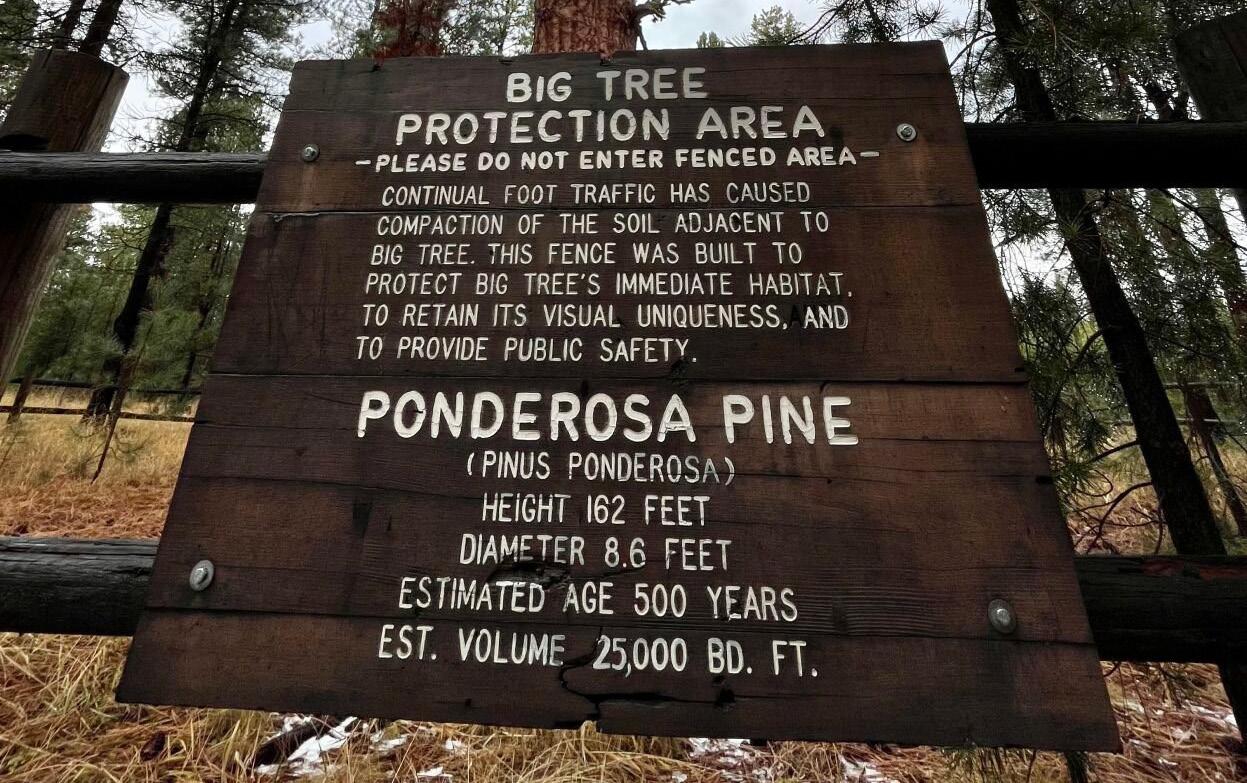

The ponderosa pine with the largest circumference on record is in La Pine State Park.

At one point, it was also designated the world’s tallest at 191 feet, but weather damaged its crown, lowering the stature of Big Tree to 162 feet. I’m not convinced, however, an extra 30 feet or so has made a dent in this specimen’s majesty.

Big Tree ascends into the sky, relatively short branches carpeted in glowing green moss jutting from its trunk.

It’s a sight to behold. The ponderosa is a wonder of nature, worth the respect and awe commanded by its lofty stature.

The tree is accessible via Cougar Woods Trail, a 1.5-mile outand-back trail that hugs an offshoot of the Deschutes River. The hike may be extended by adding a half mile with Big Tree Loop, or another mile by following an arm of the Cougar Woods Trail opposite the Big Tree Day-use area.

During the warmer months, a road connects trail users to the day-use area, which is outfitted with a few picnic tables. It is currently closed for the winter season. A 0.2-mile paved walking path descends from the day-use area parking lot to Big Tree.

The fence that surrounds Big Tree is a protective measure, as foot traffic compacted the soil around the tree before the fence was built.

The Heritage Tree Committee dedicated the tree in 2000, with a measured circumference of 28 feet and 11 inches. It’s estimated Big Tree is 500 years old, meaning it has endured centuries of weather events and human impact.

Pictures simply don’t do the tree justice. Elevation gain from the Cougar Woods Trailhead to Big Tree and back is a mellow 80 feet.

Find the trailhead by driving Highway 97 to La Pine State Park. Oce inside the park, follow signs for Cougar Woods Trailhead.

Janay Wright is a features reporter for The Bulletin in Bend.

STORY BY MICHAEL KOHN • PHOTOS BY JOE KLINE

On an exposed hilltop in the Ochoco Preserve outside Prineville, Gabriel Juarez carefully places palm-sized forbs inside shallow holes in the soft earth. He puts the herbaceous plants in strategic spots between the invasive cheatgrass and then sprinkles water over their tiny green leaves.

“We are trying to water these plants in after they are transplanted to give them the best shot at pulling through the transplant shock,” said Juarez, a stewardship associate with the Deschutes Land Trust, the Bend-based non-profit rehabilitating the preserve.

The collection of newly planted forbs is a portion of the nearly 200 plants put into the preserve recently. The planting is part of a landscape rehabilitation project that will see many more thousands planted by the Land Trust, which is attempting a stream restoration of this former agricultural landscape.

The 185-acre Ochoco Preserve sits three miles from downtown Prineville on land that only a few years ago served as hay fields owned by two families. It is located where McKay and Ochoco creeks join the Crooked River.

The farmland-to-floodplain conversion provides habitat and cover for animals and also helps clean local soil and water resources. When complete, it will also offer a convenient walking area for Prineville residents wanting to experience nature in their city’s backyard.

For most of the 20th century, the soil here was plowed up to grow crops, but that proved difficult due to the high groundwater table, uneven topography and springs, said Rika Ayotte, Deschutes Land Trust’s executive director.

In 2017 the Land Trust purchased the farmland for an undisclosed amount, intending to convert the land back to its natural state and connect it with the Crooked River Wetlands Complex on the opposite bank of the Crooked River, about half a mile away from the rehabilitation sites. The wetland complex itself is a landmark environmental project, providing wildlife habitat while doubling as a municipal wastewater treatment facility.

“We will build a bridge over the Crooked River that connects to the wetlands complex, extending that trail network that is beloved by the community,” said Ayotte.

Plans also include the construction of a bike path from Prineville, allowing residents to reach the wetlands complex without a car.

Work on the ground also required rerouting the creeks to rebuild the floodplain into a natural habitat that can attract fish and wildlife.

Felled juniper trees were placed into the streams, mimicking beaver dams to back up water and create habitat for wildlife.

The stream channels are designed to move around the property as natural forces shift the landscape over time.

“We have already had some high flow events and some rain on snow events that have changed the way the first phase looks,” Ayotte said.

Complicating the Land Trust’s effort is the large amount of soil piled up at the site, brought here in a failed attempt by the previous landowners to cover over the springs. Instead of hauling away the overabundant soil, the work crews have molded the dirt into small hills.

In addition to reshaping the landscape and improving streamflow, Juarez said a key part of the current restoration work is increasing the number of native flowering plants, which introduces competition to the weeds that have exploded on this landscape.

“Yarrow, penstemon, flax. Those are going to contribute to higher native plant densities and as a result, hopefully out-compete some of the invasive weeds,” he said.

Other native vegetation being planted here include fleabane, globemallow and scarlet gilia.

Juarez, with the Land Trust for three years, said removing the invasive weeds is particularly challenging when native plants are mixed into the area. The best strategy, he said, is to plant more native plants with the idea that they can eventually crowd out the invasive plants.

The replanting project is being done piecemeal “in small, manageable chunks,” said Juarez.

It’s a strategy employed by the Land Trust on similar projects in Central Oregon. The trust has been working with partners on the restoration of a 6-mile section of Whychus Creek near Sisters, where agriculture and flood control manipulated the landscape for decades. The project has occurred in phases over seven years, with at least one more phase remaining.

At the Ochoco Preserve, Ayotte said the battle to control weeds could take years. The amount of work that can be done is based on available resources and funds.

For now, most of the hills on the Ochoco Preserve remain barren. But Ayotte says the transformation of the land occurs with remarkable speed, pointing out one grassy hill planted only a year earlier. Over the next two years, the remaining acres will also be mulched, seeded and sown with native plants.

Trails are planned to meander through the area and along the creeks, allowing visitors a close-up view of the rehabilitation work. Ayotte expects most of the work to be completed by 2026.

Michael Kohn is a reporter for The Bulletin in Bend.

Maybe you’ve finally figured out who or how you’d like to help. Or you’ve reached that magic age — or financial level? Or perhaps you’re beginning to think about estate planning and life income gifts. Whatever stage you’re at, we’re your Oregon Community Foundation, and we help you, help others . Today could be the day. Let’s get started.

STORY BY NELLA MAE PARKS

The recent presidential election confirmed what we already know — politically, the country is half and half; divided; polarized; fractured; split.

Many folks are concerned about the split and how it shows up at work, with friends, or at Thanksgiving. But every day is a little bit of awkward Thanksgiving Day for me where I live. Rural people must navigate the divides since it is harder to post up in a bubble here.

Since the election I have had the same thought many times — now is our time. Now is the time for rural people to share what we know about how to operate in small spaces where we don’t all agree.

This is not an essay asking, “why can’t we all just get along?” We don’t. It is not asking “how on earth could someone vote for her? For him?” We did. It is not an essay excusing awful behavior or opinions. It is about the small things we must do to slowly, slowly eek our way back to trusting our neighbors. This essay is about making things better by “joining the local pothole committee”— in other words, doing something small that’s nearby with other nearby folks.

I believe we are looking for a few things: trust, belonging, purpose, and meaning. Sure, that sounds abstract but what it means is this: I feel safe, I belong to a group, I have something to do, and I understand why.

I believe we also are looking for purpose.

My dad told me when I left home and when he retired were both difficult at first because he didn’t feel useful or needed in the same way. It took time to reorient outside family and work, but now he’s busy growing vegetables for his neighbors, helping an immigrant neighbor remodel his house, and hosting a weekly jam night downtown.

Like my dad, I think most of us need direction, a place to put our time and talents, and something to do for and with the group. My dad is doing the small, purposeful things that are nearest to him with the people nearest to him.

Trust doesn’t mean agreeing on everything. For me in a small town, trust means my neighbors and I probably voted differently, and we both know the other will always stop to help change a tire.

Belonging is how we survive. I heard social psychologist Jay Van Bavel say in an interview recently we are the decedents of decedents of decedents of people who belonged. The people who didn’t belong to the group were eaten by the saber-toothed tigers or died of a minor infection.

Belonging is something we share with others, and a lot more folks need it. That means helping others belong. It means moving from a tight knit to a looser weave that includes folks up and down our streets and throughout our communities. It means seeing who’s not at the table and understanding why and for how long.

I believe when we have trust, belonging, and purpose we get meaning.

I get a lot of meaning from my “local pothole committee”— the Cove Community Association (CCA.) We host community events like the Cove Cherry Fair, Tree Lighting, clean-up day, and self-defense and NARCAN classes.

These things aren’t political, but they are meaningful. They slowly create the thousands of threads that bind us and make us belong to each other. Yes, community meetings can be long and boring — I don’t always want to go to CCA on the first Monday of the month. But I show up and I leave with my cup filled. We aren’t sitting around just drinking beer, talking about shows or complaining about politics. We are making things together. We are together working beyond ourselves. I see a lot of efforts to bridge the divides with big dialogues or efforts to just explain “these people” to “those people.” But I think every unit of change must be measured in relationships. With relationships we can call each other to better things; we can hold each other accountable; we can change and move forward; we can invite and include more people; we can find the oh-so-elusive common ground (aka the potholes.)

The big things we must do will take a lot of us and a lot of trust. If we start by building trust, belonging, purpose, and meaning in doing the small, pothole-like things, we can become something different than we are now.

Nella Mae Parks is a farmer, parent, and rural community organizer in Cove, Ore.

Since 2012, Coordinated Care Organizations have improved health outcomes for Oregonians while saving taxpayer dollars.

This is because CCOs are making community based investments in preventative care, maternal health, early childhood services, and other social determinants of health that create a healthier future for Oregon.

hile many of Oregon’s trade electives like shop and welding have phased out the class offerings over the years, Tillamook High School has been able to ep these programs alive, thanks to dedicated staff like Johnny Begin He is nning the most requested elective at Tillamook HS: the mechanics program r. Begin teaches approximately 200 students in the program and coaches the hool’s Drag Racing Team, an elite selection of the top mechanics students.

ck in 2019, a group of students approached Mr Begin with an idea, to build a ce car. “That started the whole project,” says Mr. Begin. Today, the club has o cars, one of which is a rebuilt, classic race car: a 1965 Ford Mustang.

he team not only gives students an extracurricular activity and the social nefits of a team, but also helps them to develop professional skills. Becoming reer-ready is the goal, and representatives from the professional community d technical trade schools regularly visit the shop

dditionally, students learn to budget and fundraise for the parts and equipment the club needs Students, Mr Begin and the school’s ministration collaborated this year to secure donations from the community and grants from partners like The Roundhouse undation to install a dynamometer on campus. The dynamometer is a game-changer for the program and will enable cars to be ted on-site daily, which was previously only possible on the Raceway in Portland a two hour drive north with an uncertain rformance outcome Now with a dynamometer at the school, students will be able to diagnose problems with any car, right from eir shop.

ollow THS Drag Racing Team on Facebook for updates and more information

A podcast about how philanthropy can better serve rural communities

Listen on your favorite streaming platform

Over100booths!

EarnOSHASafetyCredits! Over100booths!