7 minute read

The History of Estimating

The estimating profession has a long history. It seems that the first forms of “writing” were developed primarily to allow rudimentary systems of accounting. So, estimating probably goes pretty far back.

My career in estimating began in 1963. It started when I received a letter from Fruin-Colnon Contracting, which was the biggest contractor in St Louis at the time, asking if I would be interested in applying for a program that they were starting to train estimators for their company. Before then there was no organized formal training for estimating.

After that training, I started as an estimator. I started by doing the counting tasks related to takeoff work. Counting toilet accessories and tabulating each specific item. Then we moved on to takeoff/quantify excavation, concrete, masonry, carpentry, structural and miscellaneous steel, tile work, etc. The major tools an estimator had then were pencil and paper, scales, (engineering and architectural) along with a slide rule, which was the high-tech calculator of the time. Imagine using paper and pencil now for all of that.

The basic way of tabulating information was using what were called columnar pads, which were primarily used in accounting. All calculations were manual: multiplication, addition, subtraction, division, square root, and area calculations were completed using basic math skills, using algebra, geometry, trigonometry, and logarithms. It was very important that all entries were legible, easy to read and in a logical order. The columnar pads had individual cells in which a single digit was allowed so to some degree it forced you to be legible.

Eventually adding machines came along, which seemed like a godsend. Prior to that you added long columns of figures by breaking them into groups and then adding the groups so that it was easier to find mistakes.

Takeoff was very tedious and usually took 4- 6 weeks to prepare. All of your work was written down and calculations recorded so that it could be reviewed by a “senior or chief estimator” and any mistakes corrected. Generally, calculations were checked by a clerical person who did nothing but check the math.

One of the most tedious tasks was “cross sectioning” which was the process for computing the excavation quantities using graph paper. After the grades were plotted, you counted the boxes within the areas enclosed. Each box corresponded to a square footage based on the scale that you established when you began the cross sectioning. You then multiplied the number of squares by the square footage in each square which gave you an area. The cross sections were usually taken every 10 feet. The average area was multiplied by the distance to give you a cubic footage/cubic yardage for that area. I know it sounds complicated but that is the way things were done. It was like getting nibbled to death by ducks.

A new device that could compute the area without counting the boxes was the planimeter, which was a godsend in my mind. The next step in the advent of the planimeter was when they created one that was self-zeroing. Prior to that you had to manually set the device to zero every time you calculated an area. The planimeter had to be recalibrated from time to time to make sure that it was still accurate. But it beat the old method of counting squares. I am sure someone out there remembers the onerous task of cross sectioning.

This is a picture of the planimeter that we used. It made things a lot easier and faster.

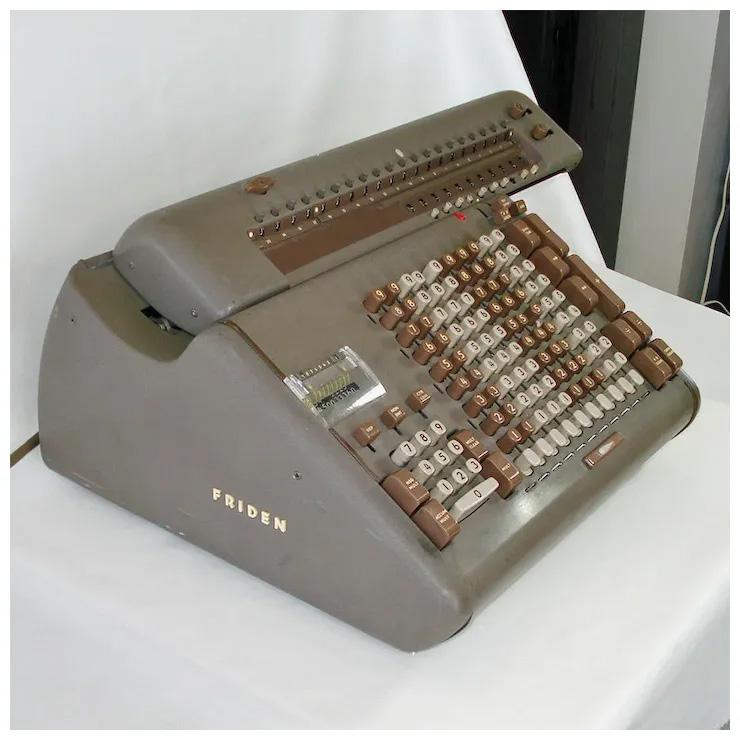

About 1965, the company purchased the first mechanical calculator, a Friden, which was very expensive. We shared it with other estimating departments. The next year the company purchased another Friden calculator because it proved to save so much time and was much more efficient. I think it cost $1,800.00 - the average cost for a new car was $2,250.00 to put it in perspective.

Another significant event was when Construction Specifications Institute (CSI) created “divisions” in a consistent and orderly manner and became an industry standard. Those “divisions” were universally adopted. That meant that you could organize your takeofflists of subcontractors, assign takeoff tasks to various estimators, and many other aspects of creating an estimate. Previous to that an architect could organize the specifications however they wanted. Some architects put them in alphabetic order, others by how the building was built. Which means in one case you might start with asphalt or asphalt tile and in another other foundations or concrete

Contacting subcontractors was another ordeal. Again, it was done manually, with postcards and mimeograph machines. Once you selected the subcontractors you wished to submit bids, a secretary printed the list and made labels for the various contractors to be affixed to the postcards. There were no computers and a lot of the contacting subcontractors was by phone and mail. The days before the bid was due were spent calling to make sure you were going to get bids.

In the early days, it was common for general contractors to self-perform the majority of their work such as excavation, carpentry, concrete, and drywall, and some did their own masonry and steel and ironwork installation. It was not as common as it is now to have a majority of subcontractors on the job. As an estimator, you were expected to know how to takeoff and estimate every trade with the possible exception of the mechanical trades, HVAC, electrical, plumbing, and other specialty trades.

When I started in estimating, benefits for the union workers were not a significant part of the wages and the material was the most expensive part of the estimate. Accurate material quantities were very important since material made up 70% or so of the estimate and labor 30%. Over time we have seen the material vs labor percentages just about reverse. Some of that is the progress made in material manufacturing and ways and means of construction-but not all of it.

Bidding work out of town presented its own set of problems. Usually, someone went on a site visit and during the visit, you would go to the local telephone office and get a copy of the local phone book. You could then set up contact lists for subcontractors. It was important to get the local wage rates in order to price work in the area.

There were several ways that the estimators priced projects. Some estimators used unit prices from past projects and others used a method where you developed a unit price. That method required you to build a crew for a task. For example, say you had a crew of 3 carpenters and 1 laborer, you would price that crew out for a day and then divide that price by the amount of square feet that they would put in place on an average day, and viola you had a unit price. We also would generate a form material unit price by pricing the amount of material required and how many reuses you might get for the material and again divide it by the total square footage and develop a unit price for material. All of the self-performed work was priced by developing or using a unit price for labor, material and equipment. These were then used, if you were successful, for setting up cost books for tracking the cost by accounting. This might be the place where you got a unit price for future projects.

When bidding work out of town, it became important to understand the local markets and how you would receive pricing. In some markets, lathing and plastering was bid together by plastering contractors while in other markets lathers and plasters bid separately. On one project we started getting plastering bids that were significantly less than anticipated. Until we understood what was happening, it caused a great deal of angst. It might cause a major mistake in the estimate. There were a lot of nuances the estimator had to be aware of, which was one of the reasons that it was expected to take ten years to become a competent estimator.

After the Friden calculator and several adding machines, we started getting other calculators, although the slide rule was still the most used method for calculating. Then the explosive electronics market generated calculators from Texas Instruments, Victor, and other manufacturers provided calculators that could do all sorts of mathematic equations, like square roots, etc.

The next step was the computer, which at first was a basic, rudimentary model. But it was so much better than paper and pencil! As the estimate was put together, it soon became apparent that the usefulness of a computer capable of keeping a running total far outweighed the speed of entry, and avoiding mathematical errors far outweighed the cost of a computer. That was the end for paper and pencil estimates.

The next step was programs and the development of spreadsheets. The first spreadsheet that was most popular was Lotus 1-2-3. Lotus 1-2-3 was introduced in January of 1983 and quickly became an industry standard. Lotus 1-2-3 was so popular because it was extremely fast compared to other spreadsheet packages. 1-2-3 was written in assembly language, which was more difficult for programmers but the resulting programs ran much faster. In addition, Lotus 1-2-3 used special graphics routines that wrote directly to the IBM PC's video memory card. This design made the screen updates faster, making the program respond faster to user actions like scrolling. Lotus 1-2-3 initially displaced VisiCalc but was eventually surpassed by Microsoft Excel. IBM purchased Lotus and continued to sell Lotus 1-2-3 until 2013.

Then as time went on, Quattro Pro became popular because it used the same menu tree, or commands, that Lotus 1-2-3 used. At least until Lotus sued them for using the Lotus menu tree .

The next step was Microsoft Excel which became the standard for everyone. The issue was learning a new way of entering and setting up your spreadsheet. But once it was set up, and you learned the program, it was wonderful. You could set up commands to make your spreadsheet tell you if you had an error in the spreadsheet by comparing the column totals horizontally and vertically. So, it soon became the industry standard. Now there are a myriad of estimating programs and software for general contractors, subcontractors and specific trade contractors.

BIM (Building Information Management) was the next step. This step stemmed from the International Alliance for Interoperability (IAI), which is now called the Building SMART.https://www.buildingsmart.org

The original thought for this organization was, since designers and architects have entered information in the CAD programs, why should other users of that same information have to enter it into the software they are using?

This was the genesis of BIM.