The last couple of years have not been easy ones for the Estonian fisheries and aquaculture sector. Just as the government lifted restrictions brought in on account of the pandemic, and travel and trade resumed, war broke out in Ukraine unleashing a new set of challenges. Sales of fish to Ukraine, a key export destination, were affected negatively early in the conflict for a few weeks. More lasting has been the impact on energy prices. Costs for fuel for vessels, gas, and electricity have shot up affecting fishing and fish farming companies as well as processors. The government is helping with an initial package of measures for SMEs and now a further measure for larger companies. These initiatives are intended to mitigate the increase in fuel prices for vessels and in electricity prices for processors and fish farmers. Higher energy prices also contribute to inflation, which in turn forces companies to rethink their investment plans. Some projects are likely to be delayed as a result. Estonia’s programme for the European Maritime, Fisheries, and Aquaculture Fund (EMFAF) was recently approved. It aims to make the sector more sustainable, help it fight climate change, and preserve biodiversity among other objectives. Aquaculture is due to get a boost that should see production increase several-fold by 2025. Read more from page 14

Biodegradeable fishing gear may contribute to reducing the volume of plastic that accumulates in the sea, a huge problem that is still growing. The fishing and aquaculture industry, according to a WWF study, is responsible for a tenth of marine waste globally. Not only do fishing nets discarded at sea remain in the water for years, but during that time they damage habitats and kill marine wild life. There are many good arguments to switch to biodegradeable plastic. Made from biofibres that originate from potato or sugar cane, they break down in 2-3 years rather than the 500-600 years it takes for conventional plastics to degrade. They do not contain the harmful chemical compounds seen in plastic, their carbon footprint is smaller, and their use would help to achieve two or three of the UN’s sustainable development goals. On the other hand, biodegradeable nets are currently not as tough, durable, cheap, or reliable as regular plastic nets. In the EU, policies are aimed at reducing pollution with plastic nets by making it easier to recycle them and efforts to retrieve those lost at sea are being increased. In addition, several projects are testing biodegradeable nets with the aim of improving them to the point where they can compete with conventional plastic. Read Dr Manfred Klinkhardt’s article on page 36

In Poland too the fisheries and aquaculture sector can feel the effects of Russia’s aggression in Ukraine. As in Estonia, exports to the east shrank, energy prices spiked, and Poland offered shelter to huge numbers of Ukrainians fleeing the war. The Polish fishing sector has made infrastructure such as fish boxes and coldstores available to Ukrainian fishers leading to a increased prices for these services in Poland. Wage costs have increased as Ukrainians employed in Polish processing or fishing companies returned home to defend their country. Replacing these employees has been expensive. The inland fisheries and aquaculture sectors noted a marked increase in the price of materials, notably fuel and feed, and in inputs such as oxygen. In the processing sector disruptions took the form of reduced demand from certain markets, and also supply chain interruptions making it more difficult and more expensive to get hold of key raw materials including salmon, mackerel, trout, and sprat. The Polish government is making use of EU funds to reduce the impact of market disturbances by compensating companies for additional costs they incur. Read more on page 45

Rapa whelk, a marine snail, has invaded the Black Sea from its home range in the Indian Ocean and the Sea of Japan. Thanks to its high fertility as well as its tolerance for a variety of salinities, temperatures, oxygen levels, and pollution intensities, the animal has been highly successful at colonising the areas it invades. In the Black Sea it has established itself so thoroughly that it has become a resource that is caught, processed, and exported by companies in Bulgaria, Romania, and Turkey to destinations in east Asia. The snail is prized not only for its meat but also for its decorative shell and it is hunted by artisanal fishers in Turkey and in Bulgaria. Rapa whelks are highly predatory feeding on shellfish including mussels, oysters, scallops, cockles, and clams, as well as on carrion such as dead fish or crabs. It has few predators of its own, mainly starfish and blue crabs (in the Chesapeake Bay). The snails proliferate at a very high rate—older animals can produce up to a million eggs four times a year, a number that allows the animal to spread rapidly despite the high mortality of the larvae. Read more about this invasive species from page 56

13 Sustainable fisheries in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea come a step closer

GFCM celebrates its 70th anniversary

14 Estonian fisheries and aquaculture State support partly offsets cost increases

18 Sustainably exploiting Estonian resources of the algae Furcellaria lumbricalis

Strong environmental focus resonates with customers

21 A thesis seeks to improve coastal environments and offer an alternate income source

Inventing uses for mussels too small to eat

24 Owner of Peipsi lake processing company welcomes change in fishing system

Greater transparency will benefit the fishery

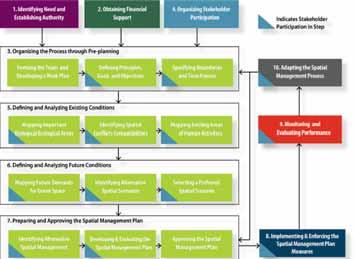

27 M.V. Wool processes fish for international and Estonian consumers

Increased input costs start to bite

30 Good catches of coldwater prawn help offset the rise in fuel costs

Decent prices contribute too

32 The Center of Food and Fermentation Technologies has created an international reputation

Research and development for the food sector

34 Power Algae designs equipment and protocols to cultivate microalgae

Optimising strategies to produce at scale

36 New ideas to reduce ghost nets in the sea

Fishing gear made from biodegradable plastic

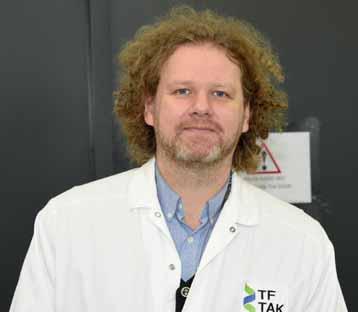

40 A brief overview of maritime spatial planning (MSP) in Europe

MSP can help solve conflicts between maritime activities

42 Russian fishing sector faces shortage of new trawlers as sanctions bite

Lack of new vessels could impact future catches

45 The impact of the war in Ukraine on the Polish fisheries and aquaculture sector Costs increase across the board

48 Turkish delegation travels to France to study shellfish cultivation

A new farming activity calls for thorough groundwork

50 Mussels sold under the protected designation of origin label Amphibious vehicles greatly facilitate harvesting

52 Planting bouchot further offshore will allow mussels to grow larger New farming techniques are not always popular

54 Online meetings and working from home not conducive to oyster consumption Covid brings lasting change to the French oyster market

56 Rapana – the predatory and highly invasive marine snail An uninvited guest in the Black Sea and elsewhere

59 Replacing plastic is currently very difficult Fish packaging is becoming a high-tech product

Guest Pages: Jarek Zielinski,

62 The head of the Baltic Sea Advisory Council executive committee has his work cut out Mitigating the socioeconomic impacts of declining fishing opportunities

Service

65 Diary Dates

66 Imprint, List of Advertisers

A plan determining renewed short-term access for EU fishing boats for important fish stocks shared between the EU and the UK was approved by the EU Council in late December, the Commission announced. The deal on “fishing opportunities” sets total allowable catches (TACs) for EU and UK fishermen, separately, for 2023, and for certain deep-sea stocks for 2023-2024.

In the North Atlantic and North Sea, the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of the EU abuts that of the UK, creating a boundary that

fishing boats normally cannot cross but that fish populations normally can and do. Managing these fish stocks therefore requires bilateral EU-UK cooperation in the setting of TACs and other management tools.

The plan recently announced is required by the 2020 EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement, a result of the Brexit negotiations. With respect to bilaterally shared fishery resources, the Trade and Cooperation Agreement provides for annual modifications of the joint

management of shared fisheries by the EU and the UK, in particular annual changes in TACs. The annual fisheries plan must take into account:

• international obligations

• the recommended maximum sustainable yield (MSY) for each species, to ensure the long-term sustainability of fishing in line with the common fisheries policy

• the best available scientific advice, with a precautionary approach taken where such advice is not available

• the need to protect the livelihoods of fishermen and women.

as the English Channel, the Irish Sea, and the North Sea. For example, there are separate TACs for haddock in the Irish Sea and those in the waters of Portugal, and separate TACs for herring in the Eastern English Channel and those in the Irish Sea.

Jousting over the EU-UK fisheries deal is not yet over: during the “adjustment period” until 30 June 2026 part of the EU quota share will be transferred to the UK. After 1 July 2026 EU-UK access to waters and fishing opportunities will be negotiated annually.

The annual plan negotiations normally also include Norway and the Faroes to avoid a separate agreement between those countries and the EU and one with the UK on much of the same fish stocks, and for the first time the latest negotiations were joined by Greenland and Iceland for the same reason. About 100 species are included in the access agreement, ranging from Norway lobster and other shellfish to cod and other demersal species, to mackerel and other pelagic species. Following ICES advice, TACs are traditionally set for each species in each of several geographic areas, such

Aside from the controversial but real question about Member States adequately enforcing the TACs, the agreement is a step forward, according to the EU Council. The deal helps protect the health of both the fishing industry and the fish stocks. If the continued downturn in the latter is not arrested, the former will continue to suffer too. Many TACs in the new agreement represent reductions in previous years’ TACs, which in principle will allow some severely stressed fish stocks to recover. Overall, the EU-UK deal provides EU fishers with over 300,000 tonnes of fish and shellfish “fishing opportunities,” in the words of the Council. UK fishermen have access to 140,000 tonnes of fish, which the UK Fisheries Minister claimed makes UK fishermen “30,000 tonnes better off now that we are outside the EU than we would’ve been if we’d remained as a member state,” referring to an estimated total UK TAC for 2023 had the UK remained in the EU.

The fifth Baltic Sea Fisheries Forum will take place in Tallinn, Estonia on 12 April 2023. This year’s event will take place at the T1 Mall of Tallinn, and it is also possible to participate remotely. The forum will focus on managing fleets to achieve the objectives of the Common Fisheries Policy.

According to the European Union’s Common Fisheries Policy, the purpose of adjusting fleet capacity to fishing opportunities is to achieve economically viable fleets. At the same time, to ensure that fishing activities are environmentally sustainable in the long term,

total allowable catches (TAC) are set based on maximum sustainable yield (MSY). Given this, is the management of fishing fleets then necessary? Fisheries experts from different countries will share their experience with modern fisheries management system and try to answer to this

question. EU policy makers, scientists and representatives from the fisheries sector are welcome to participate in the forum. More information will shortly be available on the Baltic Sea Fisheries Forum website (https://worksup. com/app?id=balticfi shery2023), so save the date!

Recognising the need for a single registry of the national fishing fleet, the Spanish government’s Council of Ministers recently approved a royal decree regulating, for the first time, the structure of the General Registry of the Fishing Fleet. Until now, autonomous communities shared with the national Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food the rights and responsibilities concerning vessel registration, leading to inefficiency. An effective single registry of vessels is a key element in fisheries management.

Each EU nation’s fishing capacity is regulated by the EU Common

Fishery Policy, and nations must ensure their own fishing capacity conforms to the rules. Fishing vessel replacement -- and entry of new vessels -- must match CFP obligations. The new royal decree makes it easier to ensure Spain’s fleet is properly managed. In recent years, some concerns have emerged that make fleet management more challenging, including environmental impacts of fishing and energy efficiency of vessels. By consolidating vessel management into one regulatory process the government intends that the royal decree will help managers and the industry alike.

Sea clam producers in Italy’s Veneto region welcomed a recent confirmation by the EU that clams from Italian waters are subject to a minimum size of 22 mm in contrast to the 25 mm limit in Spain and elsewhere in the EU. The difference is due to the nature of the ecosystem in the waters of Veneto and other Italian regions, which affects the growth of sea clams there. Opposing the EU decision was Spain, who argued that the disparity in the legal clam size puts Spanish producers at a competitive disadvantage vis-àvis their Italian rivals. In assessing the relation between clam size and ecosystem characteristics, the EU put weight on the question of sustainability of the species and the ecosystem. The minimum clam size rules are aimed at sustainability, not market characteristics or competitive forces, and they are intended to make sure a species is not harvested when reproductively immature, regardless of shell size or market value.

The new regulatory framework combines existing management tools with new ones, making the former more flexible. Such a combination will help the Spanish fishing fleet adapt to the modern requirements of the sector.

When two groups of predators compete for the same food supply, one group can benefit by reducing the size of the other. For the fish off Estonia’s coast, harvested by both grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) and fishermen, this is exactly the proposed plan: a cull of the seal herds. Seals not only eat fish that swim free, but more detrimental to fishermen, they also eat fish in fishermen’s nets, damaging gear in the process. Seals also often take just a bite out of a fish, and the injury to the fish can cause parasite infection, threatening other fish within a population. Baltic fisheries are already in peril, according to ICES, with stocks of cod and other important species continuing their long-run decline. The grey seal population, on the other hand, is thriving, with an estimated growth rate of 5-6 annually and a Baltic population

of about 30,000 animals. Within Estonian waters, researchers counted a 20-year high of 6,000 grey seals in the most recent aerial survey, according to the fisheries department of Estonia’s Ministry of Environment.

An annual quota for grey seal hunting is already in place in Estonia, set at one percent of population size, or currently 55 animals. But because the quota is not currently being met (the quota has been 25-50 filled in recent years), simply increasing the quota would be ineffective. A managed cull, perhaps with incentives, might produce more results. The possible opinion of the seals with respect to the proposed idea is expressed by many, including an expert on seal biology who argues that seals are blamed too quickly for the gear damage. More study of

the fishing industry is urged, to possibly identify problems in the industry itself instead of blaming seals, cormorants, and other wildlife that feed on fish in fixed nets.

Other opponents of a simple cull include experts sympathetic

A member of Parliament from Denmark’s Venstre, the second largest party in the coalition, has been appointed the new Minister of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries, Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen (Social Democrats) has announced. Jacob Jensen, 49, has been an MP since 2005, representing Zealand, including Copenhagen, and was the parliamentary spokesman on environment from 2017 until his ministerial appointment, his first ministerial job. Prior to election to Parliament, Mr Jensen worked in various capacities for the A.P. MøllerMaersk container logistics company from 1998-2007; he obtained an MSc degree in business administration and mercantile law from Copenhagen Business School in 1998.

As Minister of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries, Mr Jensen oversees the Danish Agricultural Agency, the Fisheries Agency, and the Veterinary and Food Administration. The Ministry previously (2015-2020) included the Environment Agency, which was split off as a separate ministry (as it was prior to 2015). The Fisheries Agency supports and regulates commercial and recreational fishing in Denmark. It promotes Denmark’s green transition, in part using resources from the European Fisheries Fund, working to develop sustainable fisheries and aquaculture and associated maritime activities. Mr Jensen faces a disgruntled commercial fishing sector, who have had to endure ever-tightening fishing quotas in the North and Baltic Seas, and

Fisheries

loss of access to British waters in the North Sea following Brexit. Other issues affecting fishermen,

to the fishermen’s plight. One suggestion is a cull limited to immediate areas of fishermen’s nets, because it is believed that a minority of the seals are responsible for the gear damage -- “the smart ones,” in the words of an expert, i.e., the ones who know where the easy fish are.

including fuel prices and the North Sea II pipeline, are outside his ministry’s purview.

The EU imports 65 of the seafood it consumes, a dependency that raises EU vulnerability to cost increases such as that caused by the transport disruption during the pandemic, an expert told attendees at a EUMOFA webinar recently. Mark Turenhaut of the Dutch Fish Federation said that the high import share of finished product and raw material exposes EU fish processors, downstream distributors, and consumers to price increases in seafood itself, and in transport such as ocean freight and fuel. These costs may not be caused by the industry but there are solutions within the industry in concert with national and EU governments.

For example, the management of fishing quotas can be improved. Quotas are necessary and are set based on scientific advice, but they are not always efficiently

managed. Some quotas are not completely filled, meaning EU-produced fish is less than it could be. Another example is aquaculture, where greater support by government, including investment incentives, would increase EU fish and shellfish production. Mr Turenhaut also recommended the development of alternative products from fishery and aquaculture, not only to grow more revenue per fish but also to spread that revenue across multiple product lines, to reduce total dependency on any one product market. Another action at EU policy level would be to expand trade agreements that provide tariff reductions on imports from developing countries, making imported raw material—and the products EU processors produce from them— cheaper, passing the lower costs on to consumers.

Boosting EU production of fishery and aquaculture products to shrink imports’ share of EU supply would contribute to the seafood sector’s ability to withstand import

supply fluctuations and volatile costs of transport logistics and of other inputs that are often global in nature, and not easily addressed by individual companies.

For the fishery and aquaculture industry of Hungary, times have been tough recently. Ponds and rivers are in the midst of the worst drought in a century; production costs of fuel and feed, like elsewhere in Europe, are at record levels; markets are yet to fully recover from the pandemic, and the Russian war against Ukraine is disrupting the industry in many ways.

December saw the organization of the general assembly of the Hungarian Aquaculture and Fisheries Inter-Branch Organization (MA-HAL), at which the industry was urged to carry on, even though 2022 saw some companies’ balance sheets turning red. New technologies are needed,

as well as improved marketing systems for value-added growth, and tighter enforcement of rules against excessive and illegal fishing and other activities. Technology and innovation support is forthcoming from the Hungarian University of Agricultural and Life Sciences, assembly attendees were informed. At government level, the recent adoption by the EU of the Hungarian Fish Farming Operational Programme Plus, covering the period 2021-2027, will provide needed support and development of the aquaculture sector. Over two thirds of that programme’s funding that comes from the EU is part of a larger package of EU funds for Hungary that is still being negotiated.

There is positive news for 2023 for large segments of the world’s aquaculture industry, including shrimp, salmon, tilapia, and pangasius. Experts from Netherlands-based Rabobank presented their predictions for 2023 at the Global Seafood Alliance’s recent GOAL Conference 2022 in Seattle, including estimates of output trends in major producing countries and demand or market conditions in large consuming parts of the world. Their presentation at the GOAL Conference was based on a report from Rabobank’s RaboResearch branch, “What to Expect in the Aquaculture Industry in 2023,” available at https://research.rabobank.com/ far/en/sectors/animal-protein/ what-to-expect-in-the-aquaculture-industry-in-2023.html.

Tropical shrimp looks to be a big winner, especially in Ecuador

where production in 2023 may grow by 30 in volume, an increase of 300,000 tonnes, on par with Thailand’s total annual production. Total Latin American output is expected to exceed 2 million tonnes. Total production in Asia, the world’s leading region led by China, saw a slight decline in 2022 but is expected to bounce back in 2023, with output exceeding 4 million tonnes. Overall, global shrimp supply is projected to grow by 4.2. “Normalise” is a market analysis codeword for “calm down”, and after a few volatile years, salmon producers in Norway and Chile will “normalise” salmon production in 2023 to historically lower growth rates, because markets need steady rather than fluctuating supplies. Thus, Norwegian output, which grew by 12 in 2021 before falling by 0.9 in

2022, will grow by 3.5 in 2023, closer to the long-run average growth rate. Chilean output fell by 8 in 2021 and 0.3 in 2022, but could grow by 2.5 in 2023, which again is closer to long-run trends.

Other important aquaculture species in global trade, including tilapia—with the highest production growth rates now seen in Latin America rather than Asia—and pangasius—still dominated by Asia— are also covered by the report.

In most of Europe, the value added tax (VAT) on seafood is considerably lower than the average applied to consumer goods generally. The tax is zero in the UK and in EU member states Ireland and Malta. Elsewhere in the EU, the VAT on seafood in France, Germany, Hungary, and Portugal ranges from 5 to 6. In Spain, however, seafood is subject to the 10 VAT applied generally to non-basic foods. Besides being a basic food, the most emphasised reason that much of Europe gives seafood a lower VAT is, it’s an especially healthy protein. On the other hand, almost everywhere -- including Spain -- the taxes on fuel used by fishermen have been cut to help them deal with the economic turmoil running through Europe in recent years. This has helped the industry weather the effects of the

pandemic, Brexit, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, among other international disasters.

Seafood consumers should get a financial break like the fishing industry does, says the Spanish Fisheries Confederation (CEPESCA). Household consumption of seafood in Spain has fallen by 25 in the last 14 years, the organisation reports, and a seafood tax that is double the average is a significant reason why. CEPESCA criticised the government for neglecting to lower VAT on seafood because the excessive tax drives consumers away from the healthy part of any balanced diet. The group noted seafood’s quality and nutritional properties, which give it a prominent place in the socalled Mediterranean and Atlantic “diets” that health experts around the world encourage. CEPESCA’s

The standard VAT rate in Spain is 21%, while the reduced rate of 10% is applied to all non-basic food. A super-reduced rate of 4% is applied to basic foods: bread, milk, eggs, cheese, fruit and vegetables, and cereals. Seafood is not considered a basic food.

calculations indicate that reducing the VAT on seafood would cost Spain’s treasury less than EUR 500 million, which the group indicated

might be completely offset by reduced government expenditures for citizens’ health problems caused by unwholesome diets.

Danish industry, from global shipping to reusable coffee cups, is known internationally for leadership in “green” or sustainable technology and practices. This innovative mindset has been given an added boost in the seafood industry with an outlay from the European Maritime, Fisheries, and Aquaculture Fund (EMFAF) “to achieve green transition, support sustainable and energy efficient fisheries and aquaculture, as well as to enhance marine biodiversity in Denmark.”

The programme, extending through 2027, is funded with EUR 287 million in contributions from the EU (70) and the Danish Government (30). Some 86 of this funding is allocated for sustainable fisheries and the conservation of aquatic resources: inducements for energy efficiency of fishing vessels through research and innovation and investments; investments to comply with the landing obligation; promotion and marketing; support to improve data collection and control and enforcement; and funding for river

restoration. Another 8 is channelled to sustainable aquaculture: including innovation, research, and investments in sustainable aquaculture to reduce negative ecosystem impacts and enhance energy efficiency; promotion and marketing. The remaining 6 is intended for technical assistance.

Denmark hopes to become a role model in the EU’s green transition with, among other things, a stated target of 70 reduction in CO2 emissions by 2030. Its EMFAF programme aims at improving gear selectivity for more efficient and sustainable fishing, and energy efficiency in both fisheries and aquaculture to reduce costs as well as ecosystem impacts. Measures that support the digital transition in fisheries and aquaculture are intended to improve economic efficiency and also environmental sustainability, with better fisheries management (e.g., setting, meeting, and enforcing quotas) and production and marketing of seafood from both fisheries and aquaculture.

Albania is home to Lake Shkodër, the largest freshwater body on the Balkan peninsula. On Albania’s northwest border with Montenegro and seasonally varying between 370 and 530 sq. km, the lake has historically been filled to the brim with carp. But in more recent years this important fishery resource has dwindled in size, suffering the same challenges faced in countless freshwater and marine areas: shoreside development and climate change, exacerbated by excessive and illegal fishing practices. Over time, the resource’s decline has driven people elsewhere in search of livelihoods.

Help is at hand, thanks to an FAO initiative begun in 2022 and aimed at restoring Albania’s inland fish resources through development of much-needed sustainable fishing practices, supplemented by aquaculture to rebuild breeding stocks. The initiative is part of

FAO’s AdriaMed Project, which is funded by the Italian Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Forestry Policies. Working with the countries along the Adriatic and Mediterranean, AdriaMed promotes scientific and institutional cooperation to improve the regional management of the fishing and aquaculture sectors. In this case, FAO is partnering with Albania’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. The project brings young people into contact with older fishermen and women, to be inspired and to “learn their ways.” FAO staff use this approach with older fishers to keep their traditions alive and to use them to support sustainable practices that will create industry opportunities for jobs, environmental protection, and support for livelihoods in the long-term.

A vital part of the Lake Shkodër project has been the establishment of an aquaculture

programme to replace the lake’s dwindling hatchery capacity. Carp broodstock were collected for breeding and transferred to enclosures for induced spawning. When the eggs hatch the larvae are raised to young fish, big enough to ensure a good rate of survival. These fish were released

into the lake for the first time in June 2022. Roland Kristo, Deputy Minister of Albania’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, who is in charge of fisheries and aquaculture, says the project has already delivered results and that the lake’s fisheries now have a future.

Throughout history and across the globe, leadership positions in the seafood industry, from vessel captains to corporate CEOs, have been dominated by men. Around the world, fish and shellfish processing plants mostly employ women on the factory floor but men in the management. In North America and Europe, women who captain their own fishing boat are famous (some have Youtube channels) solely because there are so few of them. All the world’s women who chair an international seafood corporation could hold a meeting in a small boardroom.

In the last several years women have gained enhanced recognition

and gender acceptance in this “masculine” industry, and one body to thank for this is the International Organization for Women in the Seafood Industry. WSI was founded in 2016 by a group of gender and seafood experts as a feminist organization to join the battle for gender equality and women’s empowerment in the seafood sector. “Over the past six years, WSI has been an influential international feminist organization and recognized as a first-class source of reliable scientific information on gender issues in many publications, fora and events,” as described on WSI’s website.

However, increasing financial constraints have put pressure on

WSI, and in a statement issued in December its board announced that WSI is reluctantly ceasing operations. “The decision was made with much regret and following long deliberations,” WSI’s board said in a news release. “However, the spirit of the work remains. Hence, WSI is hopeful that other organizations, companies, and institutions – working in fisheries and aquaculture, human and social rights, feminism, and gender equality – will start or continue to build on WSI’s legacy to keep the fight for a seafood industry free of gender inequalities, free of sexism and gender-based discriminations, where everybody enjoys equal opportunities and working conditions.”

Women account for almost half the workforce in the seafood industry; however, less than 15% of them hold high and well-paid positions. WSI has shown the way and now other individuals and institutions must step up as the move towards greater equality between genders must continue for the sake of future generations.

Sustainable fisheries in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea come a step closer

The 45th session of the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM) of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) was held in Tirana, Albania, from 7 to 11 November 2022 and was attended by delegates from 22 contracting parties, 2 cooperating non-contracting parties, 2 non-contracting parties, representatives of 13 intergovernmental organisations, non-governmental organizations, FAO, and the GFCM Secretariat.

The 45th session also celebrated the 70th anniversary of the GFCM. Ms Frida Krifca, the Albanian Minister for Agriculture and Rural Development, and Dr Manuel Barange, Director of the FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Division, opened the event presenting the evolution of the GFCM into its current form as a modern regional fisheries management organization. Their speeches acknowledged the role of FAO, under whose auspices GFCM was founded and managed.

During the session contracting parties including the European Union adopted a series of binding recommendations and resolutions addressing reinforcement of a research programme on rapa whelk, measures for the management of European eel, red coral, blackspot seabream, giant red shrimp, blue and red shrimp and turbot, as well as catch limits, temporal or spatial closures, and restrictions on recreational fisheries. Of 21 measures, 19 were presented by the European Union—for the management and control of fisheries, aquaculture, and the protection of sensitive habitats in the Mediterranean and Black Sea. The EU also supports the implementation of measures and the new ‘GFCM 2030’ strategy with an annual grant of EUR 8 million. For the first time ever, countries have fixed general rules regulating

transhipments at sea in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, entailing a complete prohibition except in cases of force majeure

Furthermore, upon the successful completion of a pilot phase, management measures to curtail Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing were reinforced with long-term permanent inspection schemes valid until 2030. The schemes encourage joint efforts among countries to organize inspections and surveillance, provide means and human capacity, and harmonise practices and procedures. Finally, the GFCM logbook established in 2010 was updated with new requirements in line with recent GFCM objectives and priorities. Fishers now play a more essential role in providing information reported in vessel logbooks on the bycatch of vulnerable species (seabirds, sea turtles, marine mammals, Chondrichthyans, sponges, and corals) during fishing operations. Moreover, more than 1,000 non-indigenous species have been identified in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Over half of these fish, jellyfish, prawns, and other marine species have established permanent populations and are spreading, threatening marine ecosystems and local fishing communities. GFCM members agreed to launch a pilot study in the eastern Mediterranean that is considered a hotspot for non-indigenous species, towards developing a model to be exported to the rest of the region.

A Mediterranean-wide observatory will be created in Turkey.

Based on a proposal made by Egypt, the session adopted

a resolution on empowering women in the aquaculture sector aiming to encourage CPCs (cooperating non-contracting party) to develop national and sectoral strategies and policies to support the empowerment of women in the aquaculture sector.

After a selection process overseen by the FAO management and GFCM members, the FAO Director-General proposed Dr Miguel Bernal as the new GFCM Executive Secretary. The nomination of the Spanish national was unanimously approved by the GFCM Members this week. As Executive Secretary, Miguel Bernal will be responsible during five years, for the implementation of the policies and activities of the GFCM. On behalf of GFCM contracting parties, he will manage the Secretariat, administer the GFCM autonomous budget, ensure coordination with relevant FAO Divisions and Units, promote the role of the GFCM in relevant fora, secure extra-budgetary funds, and maintain formal relationships with contracting parties, partners, and other stakeholders.

The 45th session of the GFCM adopted several measures that should make fisheries in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea more sustainable.The Estonian fisheries sector has returned to business following the pandemic apparently without facing any serious long-term effects. E-commerce, which flourished during covid, is likely to continue in one form or another as consumers have accustomed themselves to the convenience of buying fish online. Export markets, the main focus of Estonia’s sprat and Baltic herring producers, largely remained open after initially closing borders at the beginning of the pandemic. Fish shops, restaurants, catering establishments, and hotels function without restrictions so, in general, ways of doing business within th e fisheries sector have not changed.

As the market recovered from the covid crisis, the war broke out in Ukraine. For Estonian processors of sprat and herring this was another emergency following on the heels of the first. Ukraine is the most important market for Estonian suppliers of these pelagic fish and immediately after the onset of hostilities all shipments stopped. Belarus, a transit destination for supplies to Ukraine, was targeted by sanctions and was no longer accessible. Shipments to Ukraine through Poland were put on hold as both exporters and importers waited to see how the situation would develop. Siim Tiidemann, Deputy Secretary General for Fisheries Policy and Foreign Affairs in the Ministry of Rural Affairs, adds that some Ukrainian fish shops closed and buyers of Estonian fish delayed settling their bills due to the situation.

However, by the middle of April 2022, some five weeks after the war began, exports of sprat and herring picked up again, says Eduard Koitmaa from the Ministry of Rural Affairs after

studying the data from Estonian Tax and Customs Board. Ukraine is a big country and the aggression focused on certain areas. Estonian processors and traders and their Ukrainian counterparts found ways to resume the movement of sprat and Baltic herring into those parts of the country that were less affected by the war. In fact, the trade was better than it was during the covid years and therefore the ministry did not have to enact measures to support the industry. Logistics were an issue, however. The border crossing between Poland and Ukraine was used not just for the transport of fish but also other goods, including humanitarian aid, resulting initially in queues and delays due to the sheer volume of goods that was crossing the border. According to Mr Koitmaa, another contributory factor was the switch from EU trucks to Ukrainian trucks that was made at the border to meet insurance requirements. But even under difficult conditions people continue to eat so demand picked up again and factories continued to work. In March the Ukrainian hryvnia had not yet depreciated to the extent that it did a few months later, so imports were still affordable.

Of the three fishing producer organisations in Estonia, one sends almost its entire production to Ukraine and while it has also started looking for new markets it still supplies Ukraine as despite the war the country is open. The three POs, which catch some 95 of Estonia’s sprat and Baltic herring quota, have found ways to operate in

these new circumstances, says Kairi Šljaiteris from the Ministry of Rural Affairs, but they have also had to adapt. For example, a marketing campaign prepared between the Estonian Fisheries Information Centre and the Estonian Association of Fisheries to promote fish under the label “Baltic Premium Fish” in Ukraine has now been shelved.

The product imported from Estonia is block frozen Baltic herring and sprat that is then made into products for human consumption in Ukrainian factories. Another popular item is spiced sprat. The analysis of the data from the Estonian Tax and Customs Board also revealed canned fish products being exported from Estonia for humanitarian purposes and dried sprat and Baltic herring being sold in the UK for petfood.

Another fallout from the Ukraine war is the rise in energy prices. While the high gas prices have affected the processing industry to an extent it is the high cost of electricity that causes the real suffering. Some companies have benefited from fixed price contracts with long durations that they signed before the war, but others have seen their costs rise as electricity prices increase. The ministry is in the process of

approving a new measure that will offer support to companies hit by higher electricity prices. Ms Šljaiteris says that several national measures have already been approved and are bringing relief to small and medium companies, but the measure currently being processed by the ministry is funded under the EMFF (European Maritime and Fisheries Fund 2014-2020) and will support companies retrospectively. The compensation comes from money in the fund earmarked for extraordinary

measures as the EMFF period is closing at the end of 2023. Disbursal of the aid is likely to start in February 2023. The support targets the Baltic Sea trawling fleet and the long-distance fleet which are the two segments that use the most fuel. The support scheme compares the average price of fuel over a period before the war with the average price after the war started and offers the difference as compensation. Consumption of fuel by the coastal fleet is relatively modest and setting up a system of compensation for the small volumes of fuel used by individual coastal fishers would be too onerous. Coastal fishers benefit therefore only from national schemes that reduce taxes on fuel. The second part of the scheme supports companies that experienced steep increases in their electricity bills. Here again electricity costs before and after the onset of the war are compared and companies are entitled to the difference in the form of support for the period March to December 2022. This aid flows mostly to processing and fish farming companies.

Companies also invested in diversifying their energy supplies, for example, by establishing solar parks. The EMFF

offered support for this activity, but interest from the sector was only modest. Now, with electricity and gas prices rising significantly, there has been a surge of interest in greener options from businesses in the sector, says Mr Koitmaa. In addition, during the covid crisis getting hold of solar panels was difficult and companies were more wary about investing due to the unstable situation.

The Estonian programme for the European Maritime, Fisheries, and Aquaculture Fund 2021-2027 (EMFAF) was recently approved by the European Commission. The EU contribution amounts to EUR 97m and the national contribution to EUR 42m. Virginijus Sinkevi ius, Commissioner for Environment, Oceans and Fisheries noted that the programme would focus on stimulating research, innovation, and investments in energy efficiency. The biggest chunk of the allocation (38) goes towards sustainable aquaculture and processing, while sustainable fisheries receives a third, and blue economy activities, which include the

implementation of communityled local development (CLLD) strategies, receive 22. The goals of the programme are to boost the sector’s resilience by making it more sustainable, to fight climate change, to preserve biodiversity, and to combat marine litter among other targets. The new programme will continue from the old (2014-2020) which also had a heavy focus on the environment in relation to fisheries, aquaculture, and local community development, says Mr Tiidemann. Among the bigger changes he mentions is the way scientific projects within fisheries are dealt with. Estonia has decided to create three different research programmes where the issues to be studied are defined by the ministry in discussion with scientists and the fisheries sector. This way resources can be directed towards projects, more environmentally friendly fishing, for example, to ensure that the outcomes will be useful for fishermen. Another area of focus is the aquaculture sector, production from which like European production as a whole, has tended to stagnate. We want our aquaculture to move more towards the sea, he says, because costs in land-based aquaculture are relatively high and output has not shown any significant increase. The goal now is to increase production to 10,000 tonnes by 2025 (from 850 tonnes

in 2021). Mr Tiidemann admits this is an ambitious target but points out that there are several project applications to produce fish in the sea. The environmental impact of farming fish in the Baltic Sea and ways to compensate for these effects, for example by growing mussels or algae, will necessarily be taken into account when evaluating projects. A further plan is to pre-grow the fish on land to a certain size to create a market for juvenile fish which can then be introduced into cages in the sea. This reflects a change from the last programme period when investments in new farms were not funded but existing farms could apply for support. He is aware that for any operator costs will have to be kept down as competition from Norwegian salmon and trout will be fierce.

Today, with the highest inflation in the euro zone, Estonian producers are struggling with ballooning costs. To some extent these can be passed on to consumers, but they too are switching to cheaper alternatives. However, most of the production is exported and the export figures have remained strong suggesting that buyers abroad are absorbing the increased prices. Mr Tiidemann points to the other impact of inflation which is that companies are deferring their investments because prices have increased so much. Even plans that have been approved for support from the EMFF are being put on hold for this reason. Additional support to compensate for increased prices in not available,

according to fund rules, he says. Groundfish such as cod have not been targeted by Estonian fishers for the last several years so they have not been affected by the slashed cod quotas in the Baltic Sea. Decommissioning of vessels is not encouraged by the administration as the removed capacity is difficult to reinstate when stocks recover. Instead, Mr Tiidemann would rather put money into measures that help the stocks such as habitat regeneration, or establishing spawning and nursery areas. This is in line with the goals of the CFP and also more in tune with Mr Tiidemann’s personal convictions.

The lack of interest in a fishing career among young people is another ingredient in a complex situation of struggling stocks, excess fishing capacity, and ageing fishermen. A young fisher has to make substantial investments in a vessel, equipment, and fishing rights before he can start fishing. In addition, the job is physically highly demanding and there are lots of rules to

follow. These factors contribute to young people’s preference for careers in other industries. The administration is trying to encourage fishers to add more value to their catch and sell it locally through direct sales to consumers rather than to middlemen. This will give the fishers a greater share of the value and increase the local consumption of fish as well as contribute to the economy of coastal communities. If young people see how money can be made through fishing and further processing they may also be more inclined to join the trade. At the same time the administration has to balance the need to encourage young people to join the trade with the excess capacity that exists already.

In recent years some European countries have carried out tests with remote electronic monitoring which refers to a system of cameras on board fishing vessels which monitor the fishing operations. Many fishers are against the idea of being watched as they work, so trials have offered incentives (such as a bigger catch quota). The idea is to discourage discarding or other illegal activities while fishing. In Estonia the administration places more value

on educating the fishermen to abide by the legislation. The measures in place should be sufficient to prevent such activities. If cameras are to be deployed it should be based on risk assessment and the results should be analysed to establish whether such tools influence fisher behaviour. In the pelagic trawling fleet which is responsible for the bulk of the Estonian catch discards are hardly an issue. That said Estonia has an ongoing trial where three Baltic trawlers targeting sprat and herring have been equipped with cameras. Another measure to monitor fisheries is the introduction of an app PERK through which fishers register their catches. Use of the app is voluntary at the moment but will be obligatory from 2024 and it will be particularly useful to monitor the activity of fishermen on the Peipsi lake where individual transferable quotas have just replaced the previous “Olympic” method. Under the latter system fishers catch their quotas as fast as

possible and then stop fishing. To ensure the app is used, the ministry also offers support to fishers to purchase a suitable mobile phone in case they do not have one and has organized training sessions to use the app.

The impact of climate change on water temperature has not been a serious issue for several consecutive years in Estonia but that may be changing. Summer temperatures were higher than normal in 2018 to 2020 and precipitation was lower, according to the meteorological office. This trend if it persists is likely to have an impact on the aquaculture sector. Some adaptation measures are planned, for example, investments in oxygenating systems and deep wells which should help in dry periods, and the positioning of cages in deeper water in the

Baltic, so that the fish can avoid warmer surface water. With support from the EMFF and EMFAF companies are also reducing their contributions to greenhouse gas emissions by investing in new energy-saving equipment, and by setting up solar panels to produce energy for their own use. Under the EMFAF 2021-2027 programme fishermen can invest in new engines for their vessels if they emit 15 less carbon dioxide than the old engines. Fishers are happy with the fund and the opportunities it offers, says Mr Tiidemann, though there are a couple of things they would like to change including the high administrative burden and the proportion of the allocation that goes to local action groups as well as into administration either as technical aid or for fisheries control and data collection. Some grumble about the need for energy audits which are necessary to unlock support for energy- and resource-saving equipment, for example. But in general, there have been no major differences in opinion about the support and how it is used, and fishers appreciate that it covers some of the increased costs they face due to the war.

The Estonian fisheries and aquaculture sector has shown its ability to cope with crises of different kinds. Support from the EMFAF to make the industry more environmentally and economically sustainable will further increase its resilience to shocks, so that it is less affected and quicker to recover when faced with headwinds in the future.

Algae cultivation forms part of the EU vision for a more sustainable and competitive aquaculture sector. The production of algae is also highlighted in the EU’s farm to fork strategy, a blueprint for a healthy and environmentally friendly food system . The reasons for the official interest in algae are manifold. In a broader context, population growth, climate change, resource depletion and environmental factors call for a new approach to food systems.

One of the ways to address these pressures is to use Earth’s seas and oceans more to produce human food. These vast resources only contribute 2 to human food despite covering 70 of the globe. More immediately, the Russian aggression in Ukraine has affected supplies of fertiliser, animal feed ingredients, and energy. Algae, both macroand microalgae, can contribute to mitigating some of these shortages and also offer several other benefits including decarbonisation, the preservation and restoration of biodiversity, protection of ecosystems. Algae can be used as food, fuel, feed, and fertiliser and serve as a raw material for biostimulants, biochemicals, and other materials including packaging.

With their content of micronutrients, bioactive compounds, dietary fibre, and pigments algae have applications in the field of pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, cosmetics. They can also remove nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus) from aquatic ecosystems. Macroalgae (seaweed) when cultivated at sea removes carbon thereby mitigating ocean acidification. Despite the benefits that algae offer, production in Europe is virtually non-existent being still based on harvesting

from the wild rather than farming. In Asia, by contrast, algae accounts for about half the production from aquaculture. However, the potential for algae production in the EU is high—the bloc is already major imported of seaweed and demand is forecast to increase in the future in line with increased focus on health and sustainability. In Estonia the company Est-Agar is exploiting the growing demand for algae products. The company produces furcellaran, a gelling agent, from the red seaweed Furcellaria lumbricalis. As a gelling agent and texturiser furcellaran is used in the food industry, but it also has a number of other applications in cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, feed for animals and fish, fertiliser and soil conditioners as well as bioplastic applications.

The company has been through different economic and political times, as it was established in 1966 under the Soviet regime but has functioned uninterrupted from its inception. Today it is privately owned by four seaweed enthusiasts. Co-owners Urmas Pau and Mart Mere, act as the CEO and business development officer respectively. The Soviet Union could not import agar agar, a commonly used gelling agent also derived from seaweed, and needed therefore to produce it domestically. Three factories were established each in

Latvia, the Russian Far East, and Estonia, of which the plant in Estonia is the only one remaining. The factory was built specifically to exploit Furcellaria lumbricalis and is today, according to Mr Mere, the only factory in the world producing furcellaran, a product that can only be extracted from this variety of seaweed. Currently, rather than growing it, the company harvests the seaweed from the wild. For this it is licensed by the government which allows it a quota in the Baltic Sea. The estimated biomass present in Estonian waters is over 200,000 tonnes wet weight mostly between the Estonian islands. The resource is managed by the Estonian Marine Institute and the company’s quota is 2,000 tonnes, it may be possible

to increase the quota over time, but the goal is to start farming the seaweed, says Mr Mere.

Trials have been carried out over the last five years and the technique has now been tested in the sea. In addition, Estonia’s marine spatial planning strategy was recently approved which identifies sites for different farming activities, bringing commercial farming of seaweed by the company a step closer to fruition. The factory is located on the island of Saaremaa, the biggest

Estonian island. The building is the one built nearly 60 years ago and even some of the equipment, custom built in Estonia, dates back to that time. The current owners of the company bought the factory from the previous owners six years ago and have since then invested considerable sums in modernising it, including making it more environmentally friendly. One of the measures was to use switch from oil to LNG as a source of heat, but as prices shot up it was substituted with LPG. The factory can now run on four sources of energy including biogas. The waste water treatment process was also upgraded both to increase efficiency, but also to send a message to the company’s customers, the food industry,

cosmetics, and some pharmaceutical companies, that it takes its environmental obligations seriously. This is also reflected in the solar panels that have been installed on the roof of the building and which, in summer, cover about a third of the company’s consumption of electricity.

The image that Est-Agar wants to convey of an environmentally conscious company partly explains why it wants to start farming. It is another reason why the proper management of the wild seaweed biomass is so important. Part of the material the company uses is the biomass that drifts ashore when there is a storm. Some 20 families from the local community are contracted

by the company to gather the seaweed from the beach after a storm and dry it. The final product is then sold to the company. This arrangement goes back many years—it is the second or third generation of these families that is carrying out this work today. While initially the work was done manually some families have now invested in tractors and other equipment making it a commercial undertaking. This integration into the community and the support that it can offer local workers is an important aspect of the business for the company. However, the material collected this way is not enough to sustain the company’s operations, but just to supplement the biomass from harvesting. The frequency and

intensity of storms vary greatly and the biomass available for collection can be 30 tonnes one year and 300 tonnes the next. But usually whatever volume the families supply, the company buys it all.

Extracting the furcellaran is done by adding freshwater from a well to the seaweed and then boiling it, a process that demands a lot of heat. Some of the machinery runs on steam which the company generates itself. And, as far as possible, the heat is recycled and used to warm the factory. Another environmental measure is the collection of rainwater to

wash the seaweed. Resource efficiency has been baked into the upgrades and the investments that that have been made to reassure buyers that the environmental footprint of the product is as small as possible. The company has now started a process that will assess each operation for its carbon production to get a granular picture of overall emissions so that it can implement measures to reduce them further.

Kärla Village Saare County 93501 Estonia

Tel. +372 454 2205 info@estagar.ee estagar.ee

Owners: Urmas Pau CEO; Mart Mere, BDO; UG Investments

The fact that furcellaran is a plant-based food ingredient is a very useful attribute as this market is rapidly increasing. The cosmetic industry, in particular, is focused on using plant-based materials and when it originates in the sea this is even better. Seaweeds, in general, have several useful components and F. lumbricalis is no exception. For now, Est-Agar is looking at extracting pigments and antioxidants The plan is to use a multi-extraction process that allows different components to be extracted one after the other. While the technique has shown promising results in the laboratory, it needs to be tested at scale. Another idea is to create a product from the material left over from the boiling process. This could be formed into small pots that can be used to grow salads or herbs. The residual furcellaran content would allow the material to act as a membrane that controls the water content of the pot.

The company already exports over four fifths of its production to 10 countries. The product takes two forms—furcellaran flakes and powder but going forward more of the powder will be produced as it is easier to mix with other products. Powder is the future, says Mr Mere.

Product: Furcellaran (a gelling agent and texturiser from the seaweed Furcellaria lumbricalis)

Production: Up to 150 tonnes per year

Applications: Food, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical industries

Volume of raw material: 2,000 tonnes of seaweed harvested from the wild

Mussel farming in the Baltic Sea could potentially help to counteract eutrophication while at the same time providing economic opportunities for small and medium enterprises using mussels as food, feed, and fertiliser.

Exploring the potential of mussel as feed is an academic with an unusual background. Indrek Adler is earning his Ph.D at the Estonian Maritime Academy, a part of the Tallinn University of Technology. His interest is potential applications for mussels as feed or in the pharmaceutical, cosmetic, or nutraceutical industries.

He comes to his doctorate with a degree in business studies and a working life spent on the commercial side of different companies. But he wears a second hat too, that of a coastal fisherman, an identity he has carried for many years having fished recreationally since he was a child. He represents the fourth generation of fishers in his family, his grandfather was in fact a full-time professional fisherman, and for his father too it was almost an occupation. Today, Mr Adler lives on the Pärispea peninsula, the northernmost tip of Estonia, where he has ready access to the sea and can indulge his hobby whenever possible.

Fishing even for sport has over the years showed Mr Adler how the stock status of the species he targets has been changing. Catches fluctuate from year to year with some species in abundance one year and absent the next, new

species enter the area and gradually take over, but the overall trend has been one of decline. So, three or four years ago Mr Adler began to wonder how he could contribute to improving the situation for the benefit of fishers and the wider coastal community. He recognised that catches were not big enough for a fisher to make a living and part of the reason for this development was pollution in the water. Solving the pollution problem would contribute to rebuilding the fisheries so that coastal fishers could once again expect to catch enough fish to support themselves. Researching possible ways to improve the coastal environment, Mr Adler came across aquaculture but noted that it too tended to add to pollution levels unless it related to the production of macroalgae or mussels.

However, the low salinity levels in the Eastern Baltic meant there were not many species that thrive in this environment. Further research showed that the blue mussel (Mytilus edulis/M. trossulus) was about the only species that would be feasible. Mr Adler then joined the masters programme at the Estonian University of Life Sciences with a view to gaining a better understanding of the issues and to identifying a possible solution.

Eutrophication in the Baltic Sea

is widespread; Helcom assesses over 97 of the sea to suffer from eutrophication due to past and current inputs of excess levels of the nutrients, nitrogen and phosphorus. The nutrients boost the production of algae, cyanobacteria, and benthic macro vegetation leading to greater turbidity and increased creation of organic material that in turn depletes oxygen levels at the sea bed as it decomposes. Nutrient inflows from land have decreased significantly over the last decades, but the effects of this decline have not yet manifested themselves. A more recent source of nutrients is the aquaculture industry where uneaten feed and faecal matter contribute to eutrophication locally as well as in a wider area as the particles spread.

However, addressing the problem by farming seaweed or mussels is still a challenge, partly because low salinity hinders the rapid growth of the biomass, but also because there is no regulatory framework in place that will enable the allocation of space in the sea for this activity. More importantly, though, farming mussels is not economically viable because the biomass produced has no value. It could be used as fertiliser on fields, but that has little or no added value. It cannot be used for human consumption because the mussels in the Gulf of Finland are too small due to the low salinity. Extracting the meat is very expensive because of the small size of the mussels. It can be done with, for example, enzymes, but that

pushes the price up. So, there are few uses to which the biomass can be put unless a valuable and easily extractible ingredient can be identified in the mussel. Mr Adler’s research at the masters level focused on finding suitable techniques to extract the meat from the shell simply and economically. This area had not really been explored before as countries where mussels are grown in the Baltic Sea do not use the biomass as food for human consumption.

He developed a method in which the mussels were first ground

in a meat processor to create a paste. When mixed with water the particles of shell in the paste sink faster to the bottom than the meat. The meat and water can thus be decanted while most of the shell will stay back. For a small or medium enterprise this would be an economically viable way of separating the shell from the meat. The end products at this stage of the experiment are the crushed shell, and the meat and water mixture. The crushed shell also contains a certain level of protein and Mr Adler thinks it could be used as poultry feed either on its own or as an ingredient. It offers calcium, nutrition in the form of protein, and the grit that birds need to digest their feed. The water is another

potentially useful product as some studies have shown that it contains a compound that could, for example, prevent the oxidation of cut fruit (the discolouring that occurs when the cut piece is exposed to air). This may be useful to the retail sector as the water is organic and has no side effects. However, the water has a certain off taste. To remove it Mr Adler is experimenting with the addition of citric acid to the mixture of mussels and water. The really interesting end product, however, is the meat which, after centrifugation and drying, appears as a powder with a very high (65-70) content of protein. It can potentially be used as a standalone product or more likely as an ingredient in

other products to increase their protein content. This powder is intended for human consumption as it will earn a higher price than if it were used for animal or bird feed.

The experiments have also resulted in several other interesting observations. One is that the harvest season influences the yield from the mussels and the colour of the final protein powder. Powder samples from the spring and fall batches of the mussels have now been sent for chemical analysis to investigate the reasons for these differences. That there should be a difference is not surprising as in the spring the mussels are coming out of the winter season, they have not

been feeding, while in the fall they are well fed, the water is a bit warmer, and this could lead to differences in the chemical composition. In addition, the spring harvest has a much higher proportion of barnacles in the biomass compared with the autumn

harvest. Currently Mr Adler removes the barnacles (manually) as they do not add any nutritional value to the final product. The yield of protein powder from a batch of spring mussels is 5-8, while an autumn batch delivers better than 8.

The overall goal of the experiments is to identify readily scalable ways of producing useful products from the mussel biomass. This means that fancy or expensive ingredients or techniques are ruled out. The off-taste issue is an example of a challenge that can be addressed in different ways, but for Mr Adler the solution needs to be industrially scalable. The protein powder can be marketed as a sustainable product as it is produced without harming the environment. On

the contrary, the raw material (the mussels) from which it is derived has a beneficial impact on the environment. Even the ropes to grow the mussels will be made of coconut fibre to ensure the sustainability of the operation, while buoys and anchors will also be made of environmentally friendly material. If everything works out as planned farming mussels could be a way for communities to cheaply improve their coastal environment and at the same time earn something from it—which was the outcome Mr Adler hoped to achieve when he embarked on this journey.

Estonia has an inland water fishery concentrated on the lakes Võrtsjärv, Peipsi and Lämmijärv. The latter two lakes are connected to each other and form a transboundary water body shared with Russia. The total inland fisheries catch in 2021 was 2,700 tonnes, the vast majority of which comes from Peipsi and Lämmijärv. The main species caught in Peipsi and Lämmijärv are pikeperch, perch and bream together with smaller volumes of roach, while in Võrtsjärv the catch is primarily bream, pikeperch, and pike as well as eel.

The gear used are trap nets (mainly bream, eel, and pike) and gill nets (mainly pikeperch). In Peipsi and Lämmijärv the main gear used are also gill nets and trap nets of different kinds. Danish seines and pound nets are also used mainly for perch and vendace respectively.

On Võrtsjärv the number of fishing permits issued over the decade ending 2020 increased 43 to 63. In contrast, the number of fishers on Peipsi and Lämmijärv fell by over 40 over the same period from 406 to 238.

Processing companies on Lake Peipsi are organised into a producer organisation (PO), Peipsi Kalandusühistu. The PO is headed by Margus Narusing, who also owns the company OÜ Latikas, a processor of freshwater fish. The company is the biggest member of the producer organisation. The PO is located at the port of Mehikoorma on Lake Peipsi where it has reception facilities for the fish landed and a cold store. The PO sells the fish caught by its members under its own brand and has opened dedicated shops in Tartu and Tallinn to sell the fish caught by its members.

The main activity of the company is to catch and process fish into fillets, and other cuts, steaks, portions, whole fish head on or head off, as well as smoked items, and delicatessen products. The waste from the processing operation, heads, guts, tails, fins, backbones, etc., are frozen and transported to Latvia, where it is used to feed animals bred for their fur, such as mink. The main species targeted are bream, perch, pikeperch, and pike with annual volumes ranging from 150-200 tonnes of bream, 50 tonnes of perch, 30-40 tonnes of pikeperch, and 10-15 tonnes of pike. There are also small catches of burbot and roach.

Most of the fish is sold whole, fresh, but if the catches are too large or there is little demand for fresh fish then it is frozen or further processed into cuts or smoked pieces. Frozen bream, however, is the product that sells most. The catch is sold through the supermarket chain, Coop, through fresh food markets, and through the PO’s own stores. These stores do not only sell the PO’s products, but also other fish, such as Arctic charr farmed in Poland and processed at the PO’s facility, and wild-caught eel. The catching season is in spring, summer, and autumn, and during the winter catches depend on whether the lakes are frozen over or not.

But, in general, if the catches are good then all this fish is available throughout the year either fresh or frozen, Mr Narusing confirms. Most of the fish stocks are managed with quotas. But this (2023) is the first year where Mr Narusing expects the quotas to last until the end of the year. In the past they tended to be used up by September

or October. The difference is the catching regime: until 2022 fishing followed an Olympic system where fishers competed against each other catching as much as they could until the quota was filled. From 1 January 2023 this system will be replaced by individual quotas. Fishers can distribute their catches to ensure they have fresh

fish all the year round. Mr Narusing feels the change is positive and will result in a certain stability to the activity. The Olympic method meant that at the start of the year fishers would set out on the lake as fast as possible with all their capacity to catch as much fish as fast as possible. This resulted in the quota being filled already before the end of the year and the fish having to be frozen. The frozen product was fine if it was to be further prepared or preserved—smoked, dried, marinated etc.—but customers preferred fresh fish if they were to prepare it themselves; the frozen product tasted different.

The Olympic system divided the processor and the fishers in the

sense that processors disliked the system for the lack of stable catches and the need to freeze fish, while fishers appreciated it. Mr Narusing’s company, Latikas, both employs people to fish and signs contracts with independent fishers. Other fishers operating in the lake catch and sell fish to other companies. The change in system will mean that there is greater monitoring and control of the fishing activity which is likely to become more transparent as a result. Not all fishers consider this an advantage which is why some fishers prefer the Olympic catching system. For Latikas, apart from the greater stability that an individual quota system brings, the greater transparency from such a system means that all fishers operate on a level playing field. The total allowable catch

(TAC) for the lake is divided into individual quotas for the fishers including those that are employed by Latikas. The company is aware of the quotas owned by the fishers it employs and calculates on getting that volume of raw material for its production. The fishers have a certain number of gear which determines the quotas they are allocated of the different species. With some gears more than one species can be caught, while other gears are intended to catch a specific species.

The fishers are equipped with a log book in which they record their catches. Before landing the fisher has to inform the Environmental Board which may send an inspector to check the catches and ensure they tally with the logbook records.

However, not every landing is inspected so there is some scope for misreporting of catches. The fisher also takes a photo of the log book and sends it to Latikas, so that the company knows the size and composition of the catch that is coming in. The production manager then enters the information from the log book image into the official catch register. In the second half of 2023 an electronic reporting system will be introduced, and fishers will be able to use their mobile phones to report their catches. The company works with fishers who catch under the company’s fishing permits of which it owns 20 or 25. These fishers are obliged to sell the fish they catch to the company. Fishers who have their own permits also sell to the company, but they are also free to sell to anybody else.

At -5 degrees the cold store was a decidedly more pleasant temperature than the outside, where it was -16!

There are about one hundred companies of different sizes fishing in Lake Peipsi. A company can have several fishing permits and behind a fishing permit there may be a whole team of fishers. In 2022 there were 90 fishing permits and 300 fishers. The permits give fishers the right to fish when it is allowed to fish, that is, when there is unfulfilled quota. The permit also identifies the gear the fisher can use, which the fisher himself chooses as he might prefer one type of gear over another.

The fishers working for Latikas are generally all in their 50s. The number of fishers on the lake is declining, says Mr Narusing—the work is hard and it puts off young people. So there are fewer fishers in each generation. When they stop or retire they sell their permits or more seldom pass it on to the next generation.

There are 9 processing companies working with raw material sourced from the lake, which are members of the producer organisation, Peipsi Kalandusühistu, to which Latikas also belongs. But each of the companies also has its own processing unit. The PO’s role is to facilitate sales by providing the volumes and the products that make it interesting for companies in the next link of the value chain. However, at Latikas only half the production is sold through the PO, the other half is sold directly to customers or exported (mainly to Romania, Georgia, Ukraine, and Azerbaijan). The PO offers stability, says Mr Narusing, which is an advantage for the business. In addition to the fish shops that the PO opened a couple of

years ago it also has a mobile fish shop that sells products from the lake to customers spread over a wide area. This helps popularise locally-caught fish in the area and encourages people to buy fresh product. In the future the PO plans to build a common warehouse where the frozen fish can be stored and a common wholesale centre which will take care of the clients who buy small quantities so that the member companies are spared from having to deal

with the paperwork that goes with these small orders. The PO is also considering an internet-based auction to sell fish on its own behalf and on behalf of the companies to a wider range of buyers both nationally and internationally. Another initiative being considered by the PO is to invest in their own trucks to transport the fish. If all these plans are implemented Peipsi Kalandusühistu will be a very different organisation in three or four years.

Owner: Mr Margus Narusing

Species: Bream, perch, pikeperch, pike, other locally caught freshwater species

Products form: Whole, gutted, fillets, steaks, portions

Processing type: Fresh, frozen, smoked, fried

The fish processing industry in Estonia serves both the domestic and export markets with some companies focusing more on one than the other, while others offer different products to the two markets. M. V. Wool started its processing operations in 1988 supplying marinated eel to domestic customers and has since grown to one of the biggest family-owned companies in Estonia. The main raw material has changed from eel to salmon and trout sourced in Norway which accounts for about three quarters of the company’s turnover.

Meelis Vetevool, the son of the founder, and chairman of the board, is easing the third generation of the family that founded M.V. Wool into place. Hendrik Rajangu, Mr Vetevool’s nephew, has been rotating through the different departments in the company and is currently the sales manager. Sales cover the salmon and trout items which are produced in a dedicated factory established just outside Tallinn in 2010, but also a range of items produced from other fish species, such as mackerel, herring, and hake.