12 minute read

Towards Regenerative Eco-Productive Milieus Didier Rebois (FR), architect, teacher and Secretary General of Europan + Chris Younès (FR), anthro-philosopher, researcher and professor

Towards Regenerative Eco-Productive Milieus

Introduction article by Chris Younès (FR) — anthro-philosopher of inhabited milieus, professor at Paris’s École Spéciale d’Architecture (ESA) and member of Europan’s Scientific Committee. Founder member of ARENA (Architectural Research European Network). Founder and member of the Gerphau research laboratory www.gerphau.archi.fr and Didier Rebois (FR) — architect, teacher at Paris’s École Spéciale d’Architecture (ESA). General Secretary of Europan and coordinator of the Scientific Committee www.europan-europe.eu

Advertisement

How can urbano-architectural projects achieve a more synergistic combination between ecological transition and productive activities? In his book The Great Transformation, the economist Karl Polanyi called for a disembedded market economy to be reembedded into society 1 . There is a real need to move beyond predatory activities and to imagine other ways of regenerating inhabited milieus. Many of the winning projects seek to establish conditions for a complementary encounter between natural and cultural ecosystems. The interlinking of uses and mobilities is a key parameter for this, incorporating various degrees of interaction with natural and metabolic conditions. And all this encourages consideration of how life cycles operate at their different spatiotemporal scales.

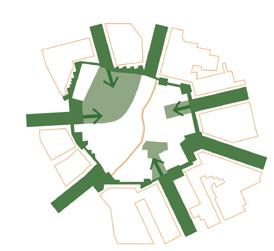

I — HYBRID AND REVIVED USES This refers to strategies that support ecological and economic transformations through territorialised sociopolitical means with the aim of reshaping society. Three projects emphasise the importance of changes in uses, seeking to construct assemblages around mixedness and social life, bringing together productive and geographical spaces employed at different scales: rivers, clusters, buildings. Priority is placed on collaborative and inclusive approaches. Hybrid Parliament, winner in Rotterdam Kop Dakpark (NL), for example is presented as a refuge for the unconventional, for the anti-patriarchal, for feminism, for transgender. This manifesto architecture is advanced as a foundation for democratic and horizontal productive projects (fig.1).

2 — ROTTERDAM GROOT IJSSELMONDE (NL), WINNER — HARTLAND > SEE MORE P.203

3 — BORÅS (SE), WINNER — MADE IN BORÅS > SEE MORE P.35

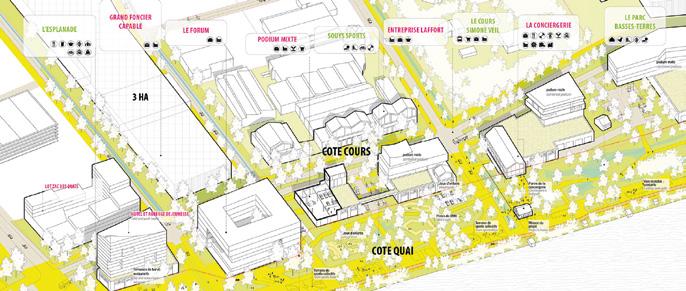

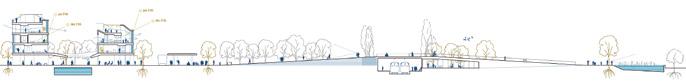

4 — FLOIRAC (FR), WINNER — SOUYS-LAB > SEE MORE P.163

For the winning project, Hartland, in Rotterdam Groot IJsselmonde (NL), a mixed programme transforms a lost estate into a dynamic neighbourhood, inspired by the socialist and economic ideals of a utopian gardencity based on commons and co-creation principles. Different scales of sharing are translated into different spatial scales, by adding new layers to the existing fabric. This is the idea of a community attached to its surroundings, offering a healthy life on the fringes of Rotterdam (fig. 2). Connective landscape In Borås (SE), the features that form hybrids winning project, Made in Borås —in keeping between natural systems with its textile industry history— explores the and mobility, water and vision of a change in the density of the site, power infrastructures with the objective of a good quality of life and climate adaptation. Restoring the emphasis on the river landscape as a substrate in the renewal of the site, with the creation of an active metropolitan park, is the approach proposed for tackling pollution and flooding while fostering biodiversity and a mixed programme of homes, shops and cultural amenities (fig. 3).

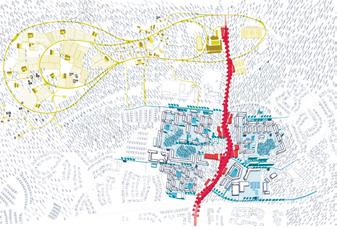

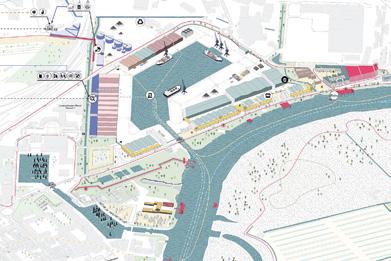

II — RENEWED AND ENRICHED MOBILITIES The fast-changing lines of travel that irrigate inhabited milieus are connective landscape features that form hybrids between natural systems (topographical, hydrographic) and mobility, water and power infrastructures. Green or active forms of mobility —walking and cycling — combined with other more rapid modes and digital mobilities, as well as vegetation, biodiversity and asphalt abstinence, are fundamental structuring elements. Mobility and the territory of mobility —the location of the project— can be the starting point. This is the case for the winning project, Souys-Lab, in Floirac (FR), where mobility is used as a structuring framework connected with the geography of the site which, in a context of metropolitan development between the city centre and the periphery, is becoming an urban area of Bordeaux. Souys-Lab is thus based on a richly networked infrastructure. Roads, railway lines, high-voltage power lines are seen as opportunities to generate habitat spaces along with ecological and economic improvements that establish new relations to the Garonne (fig. 4). In Beginning at the End, winner in Palma (ES), mobility is treated as a territorial system that links a campus

5 — PALMA (ES), WINNER — BEGINNING AT THE END > SEE MORE P.245

6 — PORT-JÉRÔME-SUR-SEINE (FR), RUNNER-UP — LA VILLE ÉCOLE > SEE MORE P.96

7 — UDDEVALLA (SE), WINNER — JALLA! > SEE MORE P.207

with a natural park. The new metro station at Parc Bit provides an opportunity to generate a new hub and also a gate to the agricultural park and the Unesco site at Serra Tramuntana. The plan is to create a new landscape with the land excavated from the digging of the metro, the water channels and the food and solar energy production and consumption cycles, while at the same time reducing greenhouse gas emissions (fig. 5). In Port-Jérôme-sur-Seine (FR), the runner-up project, La Ville École, proposes Nature considered as a third type of mobility, conceived as an axis a source of life and of multiple synergies based on an adaptable productivity becomes structure. The goal is to a resource once support the much-need ed conversion of indus capacities for symbiosis try in this town, which was shaped by the oil inare activated dustry in the 1930s, but could become a laboratory for the resilient city based around a green corridor that brings together habitat diversity, the circular economy and nature (fig. 6).

III — NATURE RECONSIDERED Nature considered as a source of life and productivity becomes a resource once capacities for symbiosis are activated. The resilience of the natural elements present on a site, which is central to the structures of certain projects, is also a source of revival for forgotten memories and uses, as well as proximities, since the realm of nature exists at the point where reality, imagination and symbol meet. Operations on the existing built and unbuilt fabric thus reveal the importance of paying close attention to material and nonmaterial resources. Once again in this session, we see the importance of these preoccupations. For example, if we consider the winning project, Jalla! in Uddevalla (SE), the archipelago city is reimagined as an infrastructure made up of buildings, woodland, timber production and recycling cycles, but also with the intention of using existing resources through participation by the local community. The scenario considers both the site and the milieu as a whole, offering not a finished solution but a flexible, adaptable and multiscale project-process that adopts an economic, social and cultural perspective involving all the public and private stakeholders (fig. 7). The interweaving of scales that is central to Europan culture is now spreading widely through the revival of proximities. For example, the runner-up project in Täby (SE), Living Proximities, proposes a human scale urban model that integrates territorial elements into a single macro system. What it promotes is a city in which modern life, public spaces, productivity and natural life can coexist, bringing a stimulating variety of services and experiences that are “within reach” of both residents and visitors (fig. 8). The question of the legacy of a place, which proves transversal, is the guiding thread in Productive Memories, the winning project in Oliva (ES). The future reshaping of the area is conveyed to us through the milieu itself and its history, which are reactivated to consolidate its specificities, its natural continuities understood as a model of production. The strategies pursued cover three scales of intervention in different phases, three memories reinterpreted in a contemporary language in order to reintroduce three new modes of production which in reality have always been there. The re-connections are handled by reintegrating the milieus of the living world with green mobilities, public space, sustainable water networks, targeted demolitions, and temporary productive activities (fig. 9).

IV — INVOLVED METABOLISMS In some cases, the presence of living nature is also extended to the metabolisms involved, helping to establish a coexistence between different rhythms and cycles and hence patterns of bioterritorial production that work with the irreversible time of the generation and transformation of lifeforms. This type of prospective approach is a new departure, since it seeks to bring together and doubly implicate life cycles and situational factors in planning. From this perspective, the aim is to “make do” with ecosystems, living fabrics that entail relations between species, including human beings, and their environments. They are directly under the influence of biotic factors (other species, other ecosystems…) and abiotic factors (the soil, the atmosphere, water…). The new projects around recycling, reuse, biosourced materials, renewable energies, incorporate climate changes and the rhythms and flows of a bioregional scale to imagine possibilities for productive economies, in harmony with clusters characterised by high environmental, economic, social and cultural potentials. A major bifurcation is at work with P2P – Plugin 2 produce, the runner-up project in Borås (SE). It takes the view that a city that produces a broad fund of knowledge for future generations and is open to a diversity of skills, ages and experiences, will have the capacity to contribute to a commonality in which the natural and built environment can coevolve harmoniously, at a larger scale than the individual, the family or the city (fig. 10). Building this kind of resilient community will take time and require orientations that challenge customary lifestyles and ways of working. Drawing on the biodiversity and industrial legacy of the site, the challenge is to involve stakeholders who act at the local level but whose impact is global. Different metabolic scales are engaged, from a project for decentralised collective production, in which brownfield sites and the riverbanks are converted into public spaces, a water system capable of incorporating flood zones, through to shared kitchen and rest areas for coproduction and co-working. Such a positioning, based on inhabited milieus operating in cycles and rhythms that are both bioregional and everyday, is precisely what is claimed by the winning project, The Productive Region, for Bergische Kooperation (DE). The team itself presents its project as a strategic regional concept, a level at which intermunicipal cooperation is absolutely imperative, but also one that is local in that it emphasises sustainable, inclusive and high-quality interventions. In their approach, productiveness is about more than simply combining habitat and work, it is the crucible of a situational intensity that arises from a mix of different uses and living environments (fig. 11).

8 — TÄBY (SE), RUNNER-UP — LIVING PROXIMITIES > SEE MORE P.60

9 — OLIVA (ES), WINNER — PRODUCTIVE MEMORIES > SEE MORE P.193

In Rochefort Océan (FR), the co-winning project, Let the River in!, turns its attention to a circular economy of regeneration with local resources and the revival of the river as a mode of transport. Reintroducing water into the city in its multidimensional facets contributes to a new “symbiotic economy” that seeks to reinforce existing production through a macIn the era of ecological rosystem. This generates transition, plans for interaction between every stakeholder and every eleproductive cities need ment in the chain, helping to bring mutual benefit to to be directly responsive all (fig. 12). Bifurcation is also driven to cycles the climate emergency and the risks of global warming, motivation for a new perspective on intervention. In Rochefort Océan, these factors are tackled head-on with the co-winning project, L’escargot, la méduse et le bégonia, which draws on the

12 — ROCHEFORT OCÉAN (FR), WINNER — LET THE RIVER IN! > SEE MORE P.100

contemporary sciences of nature but also on Pliny the Elder and Buffon, to develop a methodology of action at different scales: taking advantage of the potential for renewable energy resources in the Charente Estuary, limiting submersion by installing jetties and sand retention measures, embedding the coastline into an Atlantic production chain, building a city-island-port that marries the dynamics of oceanic production with freshwater networks and trails (fig. 13).

CONCLUSION Committed to a recognition of existing ecosystems as well as a rethinking of our modes of intervention, the productive city regeneration project resonates with the ideas of great figures like the town planner and biologist Patrick Geddes, and his views on life cycles and the environment, or the philosopher and sociologist Henri Lefebvre, with his emphasis on rhythmanalysis as a way to bring social and individual rhythms into harmony with cosmic and biological patterns. Today, the urgent challenge is to identify what needs to be done to create eco-productive milieus at local and trans-local scale. In the era of ecological transition, plans for productive cities need to be directly responsive to cycles. Indeed, the revitalisation of cities is indissociable from environmental and social synergies, which have moved to the forefront of the priorities for territorial transformation, generating resonances between naturo-cultural, metabolic and transcalar cycles 2 . These cycle-based approaches entail the inclusion of the different human and nonhuman stakeholders, and generate an emphasis on metaphorical perspectives in our vision of the bio-geopolitical future, with its mix of solidarity and commonality. The need for platforms of theoretical and practical experimentation around cycles, flows and people is therefore crucial in activating and regenerating inhabited milieus. Realising the possibilities of revitalisation demands better connections between human productions and tectonic, climatic and biological forces. The new projects around recycling, reuse, biosourced materials, renewable energies, flexibilities/reversibilities, but also around sharing, contribute to these efforts to establish lively co-rhythms. Across the board, therefore, we are seeing the emergence of a new, regenerative strategic framework, composed of contextualised re-connections and open processes.

1. Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation, USA, Farrar & Rinehart, 1944.

2. Hartmut Rosa, Résonance. Une sociologie de la relation au monde, La découverte, 2018.

1/ CHANGING METABOLISM

A new balance must be found between the relations, processes, flows and multiple forces of the sites that are large and contain a variety of agents (human and nonhuman) with long–and short-term cycles, and far-reaching ecological, economic and territorial implications.

1/ CHANGING METABOLISM

1/A Multiplying and connecting agencies

By defining and connecting the future agencies regarding air, water, soil, flood, programmes, activities and users, and new layers of functions, it may lead to a balanced growth on these sites. The final design will be something more than the sum of circular urban economies.