11 minute read

Definitions of Circularity Carlos Arroyo (ES), architect, urbanist, linguist, teacher

Definitions of Circularity

Analysis article by Carlos Arroyo (ES) — Architect, urbanist, linguist, teacher in Madrid’s Universidad Europea. He is the founder and director of Carlos Arroyo Arquitectos www.carlosarroyo.net

Advertisement

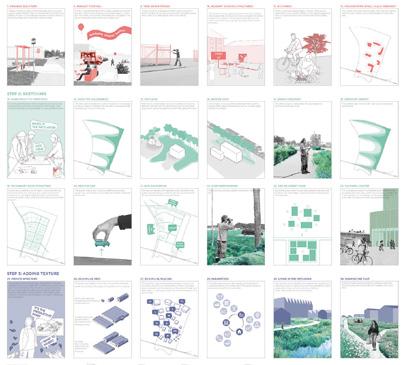

The declared purpose of this text is to explore, describe and categorize the different strategies and tactics proposed in this Europan session to introduce the principles of circular economy in productive cities. The sites in this category share an aspiration to incorporate a multiplicity of uses and resources that may create synergies in a network of interactions, to substitute an existing linear or monofunctional approach that is deemed to be obsolete. While there are differences between them, all sites are relatively large and can convene a complex set of agents, human and non-human, that relate in networks that range from the far-reaching cycles of ecology in the territory to more local short-term cycles. As a consequence, the proposals differ widely in scope and focus, and in order to establish comparisons it seems necessary to gage the scales of ambition in relation to our disciplines. Exploring the strategies, not only do we encounter differences in scope, but we also find ourselves collecting a range of definitions of circular economy as implied or stated by the winning teams in this set. Some proposals focus on natural cycles, and work on the circularity of water, fertile soil, wind or energy. They may study, for instance, a general cycle of water, visualizing how evaporation of sea water produces rainclouds that water our fields before returning to the river, and then working on the site to ensure that there is a balance between the use of the water for local activity and the contribution of the site to the general flow of the cycle of water in the territory —we have called this approach “Biosphere Circularity”. Another set of proposals look at the industries of production and manufacture in order to find synergies between different actors that may increase the efficiency of resource management. They may look into, for

4, 5, 6 — CHARLEROI (BE), RUNNER-UP — FORGING THE FALLOW > SEE MORE P.75

example, the possible transformation into fertilizer of organic matter resulting from a food transformation industry, and then propose a platform for such an exchange to take place without effort —we have called this conception “Industrial Circularity”. A group of proposals study the site to find opportunities of transformation with the minimum input for a maximum result, changing the way Incorporating a we see existing elements, bringing value to what multiplicity of uses and can already be found on resources that may site. They may find a new use for such elements, create synergies in a or transform them to enhance their value, reframe network of interactions, them within an improved to substitute an existing background, or re-describe them to change linear or monofunctional our perception —we have called this attitude “Mateapproach that is rial Circularity”. deemed to be obsolete When we look at each of these groups, arranged by definitions of circularity, and attempt to categorize the strategies and tactics that are proposed in each case, we find the following five categories:

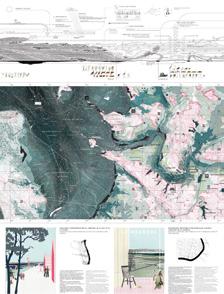

BIOSPHERE CIRCULARITY, MANAGING THE FLOWS OF NATURE We begin with L’escargot, la méduse & le bégonia, co-winner at Rochefort Océan (FR), a proposal that declares to avoid urban-centric and anthropocentric visions, engaging in a study of the territory with beautifully drafted cartography in plan and diagrammatic section at a scale of 1:60.000 that spans over the three panels of the entry, in an effort that can be described as geographic (fig. 1, 2, 3). At the same time, the text departs from a traditional idea of scale by simultaneously inquiring into the infinitely small and the infinitely large, from the behaviour of small crustaceans to international trade, or the conflict between biodiversity

and tourism —as exemplified by the medusa in the heading: a wonder of biodiversity while a threat for seabathing tourists. As a consequence, the strategies are intertwined, multiscalar, and sometimes in apparent contradiction, with forces pulling in different directions in order to find a new balance. Such is the nature of the challenge as engaged by the team, moving away from onedirectional mentalities such as the polderification of the land, to more nuanced balances where the waters are allowed to flow freely in enough places for nature to take its course while ensuring the viability of the port and agriculture, and the safety of the urban environments. Circularity in this case is defined implicitly in relation to natural flows, the biosphere as understood by the theory of circularity, with diagrams showing the formation of rocks from oyster shells in a geological timescale in parallel to the effect of fertilization of arable lands on the limes transported by storm water into the river and towards the sea at the scale of a decade. Tactics combine landscape-scale interventions such as softening or hardening the water-land limits to engage with the territorial flows, urban-scale proposals often pertaining to transit of goods and people, and human scale opportunities mainly to enjoy the unfolding of such a choreography of flows, supported by an imagery of inviting scenes where one might want to go cycling, or just sit down and watch from a wooden chair.

BETWEEN BIOSPHERE CIRCULARITY AND INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTION: SUSTAINABLY HARVESTING RESOURCES IN THE BIOSPHERE Bridging the previous group and the next, a number of proposals make it their business to work with the biosphere, but mostly as a source for industrial or agricultural production. Such is the case of the runner-up in Charleroi (BE), Forging the fallow, striving to transform brownfields into green fields by promoting a new economy based on the life cycle of wood and the reuse of wood waste and more generally biomass for energy production (fig. 4, 5, 6).

7 — ENKÖPING (SE), WINNER — ROOT CITY > SEE MORE P.79

8, 9 — LATERZA (IT), WINNER — O’SCIUVILO > SEE MORE P.91

10 — ROCHEFORT OCÉAN (FR), WINNER — LET THE RIVER IN > SEE MORE P.100

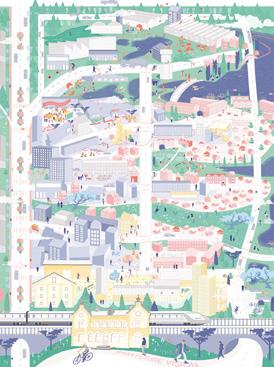

Greenery and agriculture are also instrumental in the winning proposal in Warsaw (PL), Feedback Placemaking; they are here integrated in a participatory process, making the project evolve step by step. Urban farming, productive parks and wood harvesting are proposed as tools to reintroduce people and to define recognizable places that will change the narrative of the site. In a different context, and creating a more densely inhabited imagery, the winning project in Enköping (SE), Root City, places a radical bet on urban agriculture, harnessing the forces of nature for the production of food with such conceptual strength that urban form and building typology —the substance and the image of the city— are generated by the technical elements of intensive agriculture (fig. 7). A sustainably harvested forest is at the base of the winning proposal in Port-Jérôme-Sur-Seine (FR), Boîtes à secrets, with a series of differently shaped but similarly conceived buildings, each of them a small forest of

11 — GRAZ (AT), WINNER — 47NORD15OST > SEE MORE P.83

pillars, to support a variety of activities that will change in time, a collection of “surprise boxes.” Then, despite its forest-evoking title, the winning project in Karlovac (HR), The Fantastic Forest Phenomenon: Testing a New Narrative focuses on neither greenery nor wood as the main productive aspect. The team proposes a set of infrastructural elements based on the water cycle —devices to harvest water as well as managing storm water— and renewable energy —to produce renewable energy as well as putting it to use, e.g. recharging electric cars—along corridors within a new forest that is meant to create a mythical environment to house buildings and other elements of program. The water cycle is further explored by the winner in Laterza (IT), O’Sciuvilo, also proposing an infrastructural element, in this case a hydraulic machine that intersects with public space in section to generate an urban landscape of water management and production (fig. 8, 9).

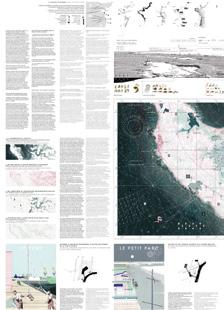

INDUSTRIAL CIRCULARITY, WORKING FOR LOCAL SELF-SUFFICIENCY Also territorial, but focused on human activity rather than on territorial ecology, the co-winner in Rochefort Océan (FR), Let the River in, plots a chart of stakeholders and products, starting with local actors, tracing their offproducts, proposing transit and transformation activities to generate outgoing produce associated to possible uses, then fed back to local actors (fig. 10).

The chart on panel one implies a double definition of circularity. On the one hand, the synergies of different actors are studied so that the would-be waste of one actor becomes a resource for a different use; this is in line with definitions of circularity based on material production, such as the main ideas behind the Cradle to Cradle movement. On the other hand, local actors are both at the beginning and at the end of the loop, with a marginal note for the possibility of resources being exchanged with other Creating a flexible territories; this introduces a different nuance to platform for industrial circularity, to propound circularity, by designing local self-sufficiency. The strategy focuses on a material base that logistics, proposing an enhanced system of fluvial allows for unexpected transportation, linking a series of nodes (an ecoexchanges campus, a biosource technology park, etc.) to manage the exchange of not-waste-but-nutrients between the different actors in the network. Proposed implementation tactics are based on what is generally known as research by design, envisaging a course of action based on reduced scale devices and prototypes implemented over time to evaluate its impact and to decide on its generalization or not and possibly develop industrialized procedures for further implementation.

MATERIAL PLATFORMS FOR CIRCULAR INDUSTRIES: DESIGNING FOR THE UPCYCLE Another in-between category emerges, with proposals that want to create a flexible platform for industrial circularity, by designing a material base that allows for unexpected exchanges and withstands change towards directions yet unknown. This is the case of the winner in Graz (AT) 47Nord15Ost, that considers the ground surface as a large-scale platform for exchange, and then proposes The Hub as a building-scale platform for unknown uses. They describe it as a radical machine designed for its almost infinite re-use. Services, technical rooms, vertical distribution elements (such as stairs and workers and vehicle elevators) are placed outside the main volume as autonomous and easily identifiable structures. The volume itself is built with hollow core slabs for maximum clear spans, assembled on a modular mesh that allows maximum potential of internal reconfiguration, or even —in a future scenario of strong demographic growth crisis— a possible reconversion into a residential building (fig. 11, 12).

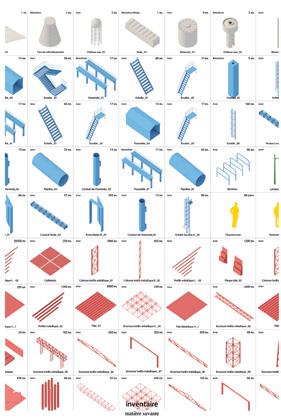

MATERIAL CIRCULARITY, UPCYCLING MATERIALS AS FOUND The Special Mention in Charleroi (BE), Matière Savante, proposes a simple, yet effective way to transform and remobilize the industrial heritage and its local context by applying a coat of paint, proposing the inventory and colour coded census of four major elements that make up the site today. A structural inventory in red (steel beams, bricks and masonry elements, sheets, etc.); an inventory of flows in blue (pipeline, bridges, railway tracks, stairs, ladders, etc.); an inventory of

immutable infrastructure in gray (extraction chimney, cooling silo, etc.); and finally human know-how in yellow, recruiting and re-mobilizing a savoir-faire that had been abandoned since the closure of metallurgical sites (fig. 13, 14). The aim of this colour coding is to underline the qualities of the existing elements, creating a valuable context In order to introduce for a program that the team, like a modern Bartleby, would a circular economy prefer not to establish, while being confident that it would you need to think of spontaneously emerge in such improved conditions. a process over time The runner-up in Enköping (SE), Painting Greyfields, uses the same tactics for a different strategy, with painting as a tool for participation in the reimagining of greyfields, proposing a version of hands-on city planning that uses paint to think, decide and eventually transform the existing elements into a joyful productive city (fig. 15, 16).

COROLARY Most of these designs are process-based and could also be categorized according to the process strategy they propose. Some are based on participation in the design process, others encourage iteration in the proposed steps, or introduce the idea of graduality in the implementation in order to transform the narrative, while the more defined architectural designs propound an open design that may change in time or may easily change purpose. A conclusion of this observation is that there seems to be a consensus amongst the prize-winning teams that in order to introduce a circular economy you need to think of a process over time, to allow for the necessary synergies to emerge, to facilitate the correction of possible dead ends, and to provide the most open design in order to allow for future re-use.

14 — CHARLEROI (BE), SPECIAL MENTION — MATIÈRE SAVANTE > SEE MORE P.76