Exceptional Needs TODAY

J.D. BARKER'S INSIGHT ON

WRITING AND AUTISM

HELPING CHILDREN CONQUER ANXIETY

UTILIZING MUSIC TO CALM, ENCOURAGE, AND TEACH

UNLOCKING MY CHILD’S VOICE THROUGH AAC

DIAGNOSED WITH DYSLEXIA, NOW WHAT?

WRITING AND AUTISM

HELPING CHILDREN CONQUER ANXIETY

UTILIZING MUSIC TO CALM, ENCOURAGE, AND TEACH

UNLOCKING MY CHILD’S VOICE THROUGH AAC

DIAGNOSED WITH DYSLEXIA, NOW WHAT?

1. Who is going to take care of your child after you are gone and where will they live?

2. How much will that care cost and how are you going to pay for that care?

3. Do you have a special needs trust and do you know how much money you will need in it? How are you going to fund it? How are the funding instruments taxed when you die?

4. What government benefits are available to your child and how do you apply for them?

5. What is the Medicaid waiver and how do you apply for it?

6. How will you communicate your plan to family members?

October 2024, Issue 18

8 EMPOWERING NEURODIVERSE YOUTH: STRATEGIES FOR PREVENTING BULLYING

Jan Stewart and Kathleen Hilchey, MEd, OCT, Q.Med

A mom to an exceptional child and an anti-bullying expert join forces to share ideas on how to prevent children from being targeted.

12 ALL THINGS OT RECOGNIZING OUR AMAZING STRENGTHS AS A NEURODIVERGENT

Laura A. Ryan, OT, OTR, OTD

An occupational therapist highlights The Brain Forest, a book recognizing neurodivergent qualities can be strengths.

OUR COVER STORIES

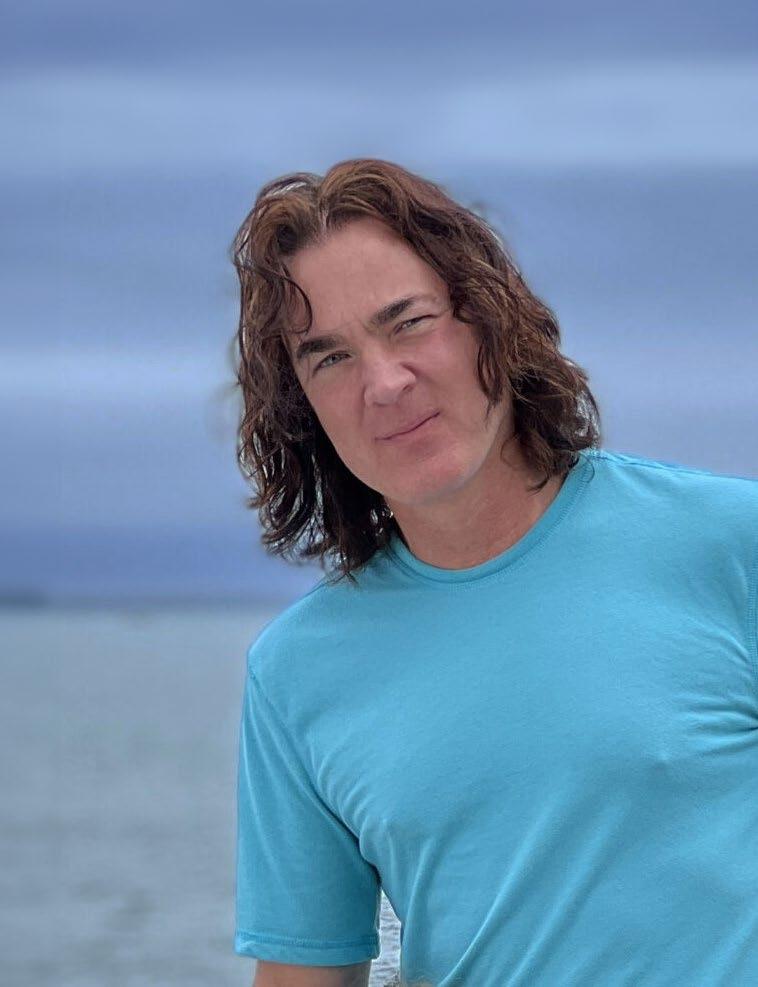

BESTSELLING AUTHOR J.D. BARKER’S INSIGHT ON WRITING AND AUTISM

Ron Sandison, M Div

This exclusive interview with successful autistic author J.D. Barker highlights how a neurodivergent brain can be a real asset for writing

UTILIZING MUSIC TO CALM, ENCOURAGE, AND TEACH CHILDREN WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

Karen Kaplan, MS

Tips for using music as a sensory and learning tool to support children with exceptional needs.

44 YOUR CHILD JUST GOT DIAGNOSED WITH DYSLEXIA, NOW WHAT?

Amir Arami, BSc, MEd

An education expert shares tips for navigating the path forward after a child receives a dyslexia diagnosis.

54 SHAPING OUR FUTURE RECITAL READY! HELPING CHILDREN CONQUER ANXIETY BEFORE MUSICAL PERFORMANCES

Rose Adams, OTD, OTR/L

For children who choose to take part in musical activities, here are some tips to get them ready for performing.

72 UNLOCKING MY CHILD’S VOICE THROUGH AUGMENTATIVE AND ALTERNATIVE COMMUNICATION

Dr. Kimberly Idoko, MD, MBA Esq

A look at how AAC can not only facilitate communication but open doors to education, social interaction, and a more independent life.

20 LIVING WITH AUTISM IN AN INSIDE, OUTSIDE, TOPSY TURVY WORLD AT WAR

Marlene Ringler, PhD

An intriguing look at the life of an adult diagnosed with high-functioning autism living in the Middle East as told by his mother.

22 BOOKS AND PLAY ARE A HUGE INFLUENCE ON LEARNING LANGUAGE

Lavelle Carlson, MSLP

A look beyond the concept of reading to discover how books can help children learn words and language.

25 EMPOWERING STUDENTS WITH AUTISM THROUGH EDUCATIONAL ADVOCACY

Jake Edgar, MS

A special education professional shares how involving students in their IEP or education plans can promote their growth, self-awareness, and educational success.

28 EXCEPTIONAL ADVICE FROM MESHELL HELPING THE EXCEPTIONAL PARENT IN DENIAL

Meshell Baylor, MHS

An advocate and mother of four children, two of whom are on the autism spectrum, offers guidance for helping families and caregivers navigate a child’s new diagnosis.

30 AN AUTISM DIAGNOSIS IS NOT A LABEL; IT’S LIFE’S ULTIMATE CHEAT CODE

Jeremy Rochford TI-CLC, C-MHC, C-YMHC

Learn from a self-advocate how receiving an autism diagnosis can be the secret code to understanding yourself and living your best life.

34 HOW CAN A SCHOOL COUNSELOR ASSIST MY CHILD WITH A DISABILITY?

Dr. Ronald I. Malcolm, EdD

An education professional overviews how a school counselor can assist children with disabilities.

36 SAFETY GOALS WITH NICOLE MAKING OUR SEASON BRIGHT: EASING HOLIDAY STRESSORS FOR CHILDREN WITH EXCEPTIONAL NEEDS

Nicole Moehring

This article provides guidance on ensuring that the holidays, which often deviate from routine, are comfortable experiences for children with exceptional needs.

38 THE DATING DUO CONQUERING SOCIAL SHAME TO BUILD YOUR SOCIAL LIFE

Jeremy and Ilana Hamburgh

This article examines how to overcome social shame, a familiar feeling among those who fear not experiencing the same relationships as their peers.

48 NATURE NOTES GOING DOWN A SENSORY PATH TO HELP CHILDREN REGULATE

Amy Wagenfeld, PhD, OTR/L, SCEM, EDAC, FAOTA

Ideas for creating interactive walks, paths, and stations to support a child’s sensory needs.

52 HOW TO DEVELOP SHARING WHEN THERE ARE LEARNING DIFFERENCES

Karen Kaplan, MS

A special educator offers ideas for building the concept of sharing in children with exceptional needs.

54 WE LEARNED ALL THE WRONG LESSONS FROM THE PANDEMIC

Madeline Richer

Following the pandemic, in-person learning and penalizing absence have become commonplace, and a teacher questions why we haven’t learned from the past.

56 EXCEPTIONAL SPOTLIGHT MEET DR. MORÉNIKE: ADVOCATING FOR THE NEXT GENERATION

Haiku Haughton

An interview with educator, author, autism and HIV advocate Dr. Morénike Giwa Onaiwu.

60 AUTISM-FRIENDLY FAMILY TRAVEL: TIPS FOR A STRESSFREE JOURNEY

Brianna Hillison, BCBA

How to ensure family trips are fun and exciting when disrupting your child’s routine.

68 SUPPORTING A HARD-OFHEARING CHILD AT SCHOOL

Dr. Ronald I. Malcolm, EdD

An educator shares guidance for helping hard-of-children to thrive in the classroom.

77 REFLECTIONS COME TOUCH HIS CHEEK©

Gary Shulman, MS, Ed

A retired special needs consultant shares a moving poem offering insight into those with exceptional needs.

78 VISTA DEL MAR HELPS PEOPLE ON THE SPECTRUM NAVIGATE THROUGH SELF-ACCEPTANCE

Kate Foley

Dr. Joshua Durban talks to Kate Foley about Vista Del Mar’s new autism clinic, which is at the forefront of its latest venture.

82 A MOTHER AND DAUGHTER’S FIGHT AGAINST DISABILITY DISCRIMINATION

Susan Russell

A young woman’s challenging journey to receiving the degree diploma she earned is shared by her biggest cheerleader: her mother.

86 FINANCIAL FOCUS THE VALUE OF AN EXPERT GUIDE FOR EXCEPTIONAL NEEDS FAMILY PLANNING

Ryan F. Platt, MBA, ChFC, ChSNC, CFBS

Discover the value of working with an expert guide who understands government benefits, taxation, legal structure, and financial strategies.

Our mission is to educate, support, and energize families, caregivers, educators, and professionals while preparing all families for a healthy future.

exceptionalneedstoday.com

Founder/Publisher

Amy KD Tobik, BA

Lone Heron Publishing, LLC

Magazine Staff

Editor-in-Chief: Amy KD Tobik, BA

Editorial Assistant: Margo Marie McManus, BS

Editorial Intern: Haiku Haughton

Copy Editor: Emily Ansell Elfer, BA

Digital Marketing Coordinator & Social Media: Dione Sabella, MS Graphic Designer: Annie Rutherford, BA

Professional Consultants

Chris Abildgaard, LPC, NCC, NCSP

Debra Moore, PhD

Brett J. Novick, MS, LMFT, CSSW

Annette Nuñez, PhD, LMFT

Amy Wagenfeld, PhD, OTRL, SCEM, EDAC, FAOTA

Contact

editor@exceptionalneedstoday.com

advertising@exceptionalneedstoday.com submissions@exceptionalneedstoday.com editorial@exceptionalneedstoday.com

Exceptional Needs Today is published quarterly and distributed digitally by Lone Heron Publishing.

Disclaimer: Advertised businesses and products are not endorsed or guaranteed by Exceptional Needs Today, it’s writers or employees. Always follow medical advice from your physician.

Life is beautiful, but it can be hard; there is no other way to put it. Perhaps my advocacy role in the disability community magnifies my perception. Or maybe it’s my disability diagnosis that affects my view. But even on the most challenging days, when we listen to one another, share our experiences, and provide grace, I see a world of possibilities.

Revealing our lives can be challenging, especially when we are knee-deep in handling a child’s diagnosis or our own. Or perhaps we feel consumed by the idea of providing a lifetime of support when there are significant disabilities. According to the World Health Organization, millions of people act as unpaid caregivers to an estimated 1.3 billion people with disabilities worldwide.

Issue 18 is a unique edition offering a rare glimpse into the challenges within the exceptional needs community. It provides valuable strategies and support, acknowledging that everyone's situation differs, so approaches and solutions will always vary.

It’s an honor to feature J.D. Barker on our cover—a New York Times and international best-selling author whose books have sold in over 150 countries, to include a collaboration between ubiquitous thriller writer James Patterson. In an exclusive interview, autism advocate and author Ron Sandison, M Div, highlights J.D.'s fascinating college and corporate employment journey, which ultimately led him to his late autism diagnosis. Today, J.D. believes his neurodivergent mind is an asset to his writing career and key to developing his books. Read Bestselling Author J.D. Barker’s Insight on Writing and Autism to learn more about what has inspired his work and what he wishes everybody knew about autism.

Did you know an estimated 1 out of 10 people have dyslexia? Early diagnosis and intervention are crucial in learning the skills to improve reading and develop life strategies. If you or someone you know has difficulty decoding words, which can impact reading fluency and comprehension, read Your Child Just Got Diagnosed with Dyslexia, Now What? by education expert Amir Arami, BSc, Med. Amir, who, following a traumatic brain injury, dedicated himself to creating solutions to empower people with communicative difficulties through assistive technology, shares tips for navigating the path forward after a child receives a dyslexia diagnosis. He says

recognizing that dyslexia is a specific learning disability, not a reflection of a child's capabilities, is crucial in shaping an approach to support.

Sticking to a routine can be critical when someone is diagnosed with autism. Brianna Hillison, BCBA, says a long trip and a new environment can be overwhelming sometimes. Be sure to read her piece, Autism-Friendly Family Travel: Tips for a Stress-Free Journey, where she provides strategies for managing sensory overload, communication difficulties, and unexpected plan changes.

We hope you find the reassurance and support you need as you read Issue 18. Our articles contain excellent strategies for conquering relevant issues, such as managing holiday stressors, overcoming social shame to build a social life, finding ways to prevent bullying, and unlocking a child’s voice through Augmentative and Alternative Communication. Be sure to read guidance for helping families and caregivers navigate a child’s new diagnosis and ideas for creating interactive walks to support a child’s sensory needs.

Be sure to also look for our newest column, Exceptional Spotlight, which highlights the extraordinary stories, achievements, and perspectives of those who have made significant contributions to the special needs community. Don’t miss Haiku Haughton’s fascinating interview with educator, author, autism, and HIV advocate Dr. Morénike Giwa Onaiwu.

As always, we thank our contributors, advertisers, and subscribers who continue to support and play an integral part in our award-winning magazine. Let's continue to work together to bring awareness, acceptance, and inclusion.

Best,

Amy KD Tobik

Editor-in-Chief, Exceptional Needs Today Publisher, Lone Heron Publishing

By Jan Stewart and Kathleen Hilchey, MEd, OCT, Q.Med

My daughter Ainsley is my hero. She faces significant challenges with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Tourette’s syndrome, learning disabilities, and mood and anxiety disorders. She cannot read social cues, leading her to misinterpret what others say or do and to blurt out inappropriate comments.

When she was in middle school, her behavioral challenges led to teasing, bullying, and exclusion. She yelled out of turn, jumped on desks, and took other students’ lunches if she felt they weren’t friendly to her and could be rude.

Those middle school years were tough enough for every adolescent, but for Ainsley, they became unbearable. At first, some students made fun of her and imitated her. The teasing escalated to bullying, to the point that one day, three girls cruelly locked her in a locker. Fortunately, the principal was nearby and heard Ainsley’s calls for help. And while the school intervened on her behalf, Ainsley often cried at night and had trouble believing in herself. My heart broke when I came home one afternoon and found her curled up in a ball, sobbing, “Why don’t I have any friends? Why is everyone so mean to me?”

The good news is that we can help our children learn to prevent bullying!

Meet Kathleen Hilchey

Kathleen Hilchey is a highly regarded anti-bullying and conflict specialist. She is also a teacher and the mom of two neurodivergent children who were targets of bullying. She has seen first-hand the pain that bullying creates and the lasting impact of these traumatic school or work experiences, and she knows the need for our kids to find a voice in friend-tofriend conflicts.

These experiences have led her to two foundational beliefs:

• Bullying is a global issue with impacts that extend far beyond the moment of aggression.

• If we can teach people the skills to handle conflict better, bullying ends.

Based on the work of Adele Faber and Elaine Mazlish in the classic book Siblings Without Rivalry, Kathleen has devised a simple problem-solving method to help our children find their voices in friend-to-friend conflicts. This proactive process bully-proofs our kids by teaching them effective conflict management strategies.

Please read Kathleen’s own words below:

We know that neurodiverse kids get more easily tangled in the web of toxic relationships. My goal is to help them find a voice to stand up for themselves in a way that drastically decreases their chance of being bullied.

A significant part of this process relies on adults guiding while allowing the child to explore and select the best solution. This might mean they will identify a solution that seems odd, wacky, and ineffective to you. If your child seems confident in their solution, it is the right one for them: confidence is the key ingredient for success!

This is because we have the bullying theory wrong. Humans who bully aren’t looking for the weakest, smallest, or nerdiest kids; they are simply looking for someone they can scare.

Once they sense fear from another person, they attach themselves to them and repeat whatever action or words make them afraid.

Yet, suppose our neurodiverse kids are given easy tools to extricate themselves from these tricky social situations with grace. In that case, they empower themselves not to give the bully the fear response they crave. The aggressor will simply look for another target.

It’s okay if you disagree with your child’s chosen strategy. The key is that it must feel authentic to them.

This method is most effective as a prevention strategy before your child is bullied. It is best used in general peer-to-peer conflict: unkind words, jostling, play-fighting gone sideways, or unkind choices. Once bullying has developed, it’s less effective because it doesn’t address the power dynamics and trauma that develop in these toxic relationships.

Let me share a situation in which it DID work. A few years ago, schoolmate Charlotte shoved eight-year-old Eve in the schoolyard a few times. Eve had ADHD and autism, and her parents were concerned that she was being picked on because of her diagnoses. This situation hadn’t quite hit the threshold of bullying, but left unchecked, it could easily have gotten there.

I taught Eve and her parents The Problem-Solving Method:

Step 1: Write a one-sentence statement about what you’ve noticed

“I noticed Charlotte has shoved you a couple of times. What’s up?”

Listen carefully and ensure you truly understand the situation. Take notes so you can refer to this statement as needed.

Step 2: From the information in Step 1, create two sentences

“I want you to be able to feel safe in the schoolyard. AND I want Charlotte to be stood up to in a way that is respectful.”

“What are some ways to help you feel safe AND stand up to Charlotte respectfully?”

Work with your child to come up with as many solutions as possible.

Write down every solution (even the terrible ones!).

Ask: “What else?” in a neutral tone every time you have written a solution.

Suggest no more than 50% of the solutions.

This is not the time to eliminate ideas or lecture your child on good or bad strategies. The quieter you are, the more your child will learn what your voice sounds like.

Eliminate every answer that doesn’t accomplish BOTH goals: feeling safe in the schoolyard AND respecting Charlotte. (This is where you get to eliminate all the solutions that don’t sit well with you!)

This is the most crucial step. You are entrusting them with problem-solving. Remember that they are the experts in their lives.

When Eve saw Charlotte coming towards her, she decided she would giggle and then make the motion of swimming away. Swimming was her favorite activity, and it made her feel strong. When she chose this plan, she lit up like the sun! I asked her, “Do you think you can do this?” She said, “Yes! I’m actually excited, too!”

Eve’s parents were extremely nervous. They worried that her response would lead to more teasing. I told them to trust her (and me!). I noticed the utter happiness on her face as she practiced her swimming plan, and I reminded her parents that Charlotte’s goal was to instill fear. Eve couldn’t be scared while swimming; this is where she felt the most confident. This gave them the resolve they needed to let her go through with it.

The next day, Charlotte approached Eve in the yard with a mean look on her face. Eve giggled and “swam” away from her with all the joy in the world. Charlotte tried several more times, leaving Eve to splash and swim around the schoolyard. And soon, Charlotte left her alone!

Consider Eve’s underlying message to Charlotte as she was swimming away from her: “You don’t scare me!” This led Charlotte to shift her gaze away from Eve since she wasn’t getting the desired fear response.

I am astounded by the solutions my clients and students devise and often surprised that they work. The “swimming away” strategy seemed so wacky that even I couldn’t believe it would succeed…but it did!

Step 6: Keep the brainstorming paper

Touch base in a day to see how the chosen solution is going. If it hasn’t worked, go back to the brainstorming sheet, add some new options, and choose the next best one to try.

Like Eve’s parents, I was skeptical when Kathleen told me about the swimming strategy. I believed Charlotte would simply make more fun of Eve and escalate the situation. But, as Kathleen found, it worked!

Now, let’s think about Kathleen’s process. She taught us to:

• Empower our child to take stock of a problem

• Together with our child, narrow it down to two main points

• Think of potential solutions together, and let our child select the one to try

As parents and caregivers, we can empower our neurodiverse youth not to fall victim to bullies. In doing so, we help them build confidence and believe in themselves. And doesn’t this sound just like an adult solving a problem? What could be better?

Faber, A., & Mazlish, E. (1987). Siblings without rivalry: how to help your children live together so you can live too. New York, Norton.

Jan Stewart is a highly regarded mental health and neurodiversity advocate, author, and parent. Her award-winning memoir Hold on Tight: A Parent’s Journey Raising Children with Mental Illness is brutally honest and describes her emotional roller coaster story raising two children with multiple mental health and neurodevelopmental disorders. Her mission is to inspire and empower caregivers to have hope and persevere, as well as to better educate their families, friends, healthcare professionals, educators, and employers. Jan chairs the Board of Directors at Kerry’s Place Autism Services, Canada’s largest autism services provider, is a Today’s Parent columnist, and was previously Vice Chair at Canada’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. She spent most of her career as a senior Partner with the global executive search firm Egon Zehnder. Jan is a Diamond Life Master in bridge and enjoys fitness, genealogy, and dance.

�� janstewartauthor.com

AMAZON Hold on Tight: A Parent’s Journey Raising Children with Mental Illness

Kathleen Hilchey, MEd, OCT, Q. Med is a conflict specialist in Ontario, Canada. She works from a trauma-informed lens with families, camps, schools, and workplaces to stop cycles of bullying and infuse conflict management skills into our systems. She spent 10 years teaching in the secondary public system but started her career in Outdoor and Experiential Education. She has an MEd in Peacebuilding Techniques from Brock University and is a Qualified Mediator.

�� strongandkind.org

INSTAGRAM @kathleen.hilchey.antibullying SQUARE-FACEBOOK kathleen.strongandkind LINKEDIN kathleen.strongandkind

By Laura A. Ryan, OT, OTR, OTD

Neuroaffirming culture not only recognizes one’s differences as strengths but also how those strengths can be assets. This article highlights a wonderful book called The Brain Forest, written by Sandhya Menon, a neurodivergent pediatric psychologist. This picture book illustrates how different neurodivergent brains function and the advantages each neurodivergent profile brings to the table. So, let’s take a walk through The Brain Forest!

The Brain Forest is written in rhyme, which makes it fun to read and listen to. Each tree in the “forest” has a different leaf pattern, illustrating how each brain is wired or physically created. For example, the tree that depicts a dyslexic brain is drawn with patterns because that is how someone with dyslexia may best learn. Since we are often made up of combinations of different profiles, the brain of someone with more than one diagnosis is patterned after the trees drawn with those particular patterns. This is important because we rarely have just one patterned profile; we are often a kaleidoscope of many patterns. Each page is dedicated to a neurodivergent profile, including autism, attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and dyslexia.

Other neurodivergent profiles, including intellectual disability, Tourette’s syndrome, situational mutism, giftedness, pathological demand avoidance, and OCD, are referenced. Each illustration and rhyming description indicates how that brain works.

Throughout The Brain Forest is a thread of affirmation for the value of each brain style and the importance of inclusion and universal design so ALL brains can sing. As an occupational therapist, I particularly like the pages at the end of the book that relate characteristics to occupations that one could find meaningful or succeed in. For example, one picture

depicts a young person describing themselves as good at “understanding animals” and suggesting they may be a future veterinarian. This opens an opportunity to discuss the wants, hopes, and needs that lead to a meaningful and fulfilling life.

Recognizing one’s strengths and the functional application of those strengths is the focus of Autism Level UP’s tool

I particularly like the pages at the end of the book that relate characteristics to occupations that one could find meaningful or succeed

in.

titled Person Specific Sensory Factors: Generic Challenges and Strengths. While not exhaustive, this document nicely separates the different senses; auditory, visual, tactile, olfactory, proprioception, and vestibular into two categories: hypersensitive (more sensitive) and hyposensitive (less sensitive) if it is applicable to that particular sensory system.

The document then lists the potential strengths and challenges of each sensory profile and what activities and environments can be supportive or disadvantageous for that sensory profile. For example, for an individual with heightened hearing, a strength may be the ability to discern the nuances of a particular sound, such as pitch, and a challenge may be the large amount of auditory processing that needs to be filtered and the potential to become overwhelmed.

Vocational areas where this individual may be successful could include tuning musical instruments, and leisure/social areas supporting this strength could include relaxing with friends while listening to music. Environments that could be less supportive for an individual with this profile could be noisy settings, such as a mall that could echo sounds, or a spot with many people, such as an airport. Looking at this chart from a strength perspective, one can build their talent in an area that is supportive of their profile, thereby leading to a greater percentage of success and happiness.

Looking at this from an affirming perspective, one can predict what they may need for self-support and proactively support that need. There are some important caveats to this chart, however. The authors of Autism Level UP! clearly state that every person is different, and this chart is not “one size fits all.” Every person is unique and may have a mix and match of each descriptor. Lastly, one should consider the context that the strengths and challenges may present and that certain vulnerabilities may occur only in a certain setting.

Understanding how our brains work and how to use our strengths authentically, meaningfully, and productively is a building block to a healthy and happy future. Take a meander through The Brain Forest and see how you can use your talents!

Resourcess

The Brain Forest https://www.onwardsandupwardspsychology.com.au/product-page/ book-the-brain-forest

Autism Level UP! Sensory Factors Strengths/Challenges https://www.autismlevelup.com/#tools

Laura A. Ryan, OT, OTR, OTD, is an occupational therapist who grew up on a large horse farm in Massachusetts. She has been practicing for over 30 years and has been using hippotherapy as a treatment tool since 2001. She enjoys seeing the happiness and progress each person has achieved through the therapeutic impact of the horse. Laura has also developed a program for breast cancer rehabilitation using therapeutic input from the horse.

✉ hooves4healingot@gmail.com

Exceptional Needs Today meets J.D Barker, an author who believes his neurodivergent mind is an asset to his writing career and key to developing his books.

How did your childhood experiences prepare you to be an author?

I grew up without a television, so I read from a very early age. My mom would take us to the library all the time, and I began to read by age three. By kindergarten, I had read every Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew mystery. I moved on to the classics like Charles Dickens and Mark Twain, and I read my first adult book, Dracula, by age eight. I really feed my imagination by getting lost in books and stories.

Our house was in the middle of a forest, which was a scary, creepy location to begin with so that fueled the horror side of it. I had a sister who was 15 months younger than me, so we

would write stories to each other. We created a little library in our house. She would check out my stories; she returned them; if she didn’t, I charged her a late fee. I think my sister still owes me money. My writing began basically by reading and creating stories of my own.

Before writing, what jobs did you have, and how did you get your first agent? Also, what was your college major?

I have loved to write my entire life, but my parents said you cannot make a living from it. [I was told] it’s a fun hobby and something you can do on the side. My parents wanted me to focus on a desk job, so I went to college for finance. I got degrees in business and information technology and finished halfway through a psychology degree. I focused mainly on finance. At night, I would write to keep my sanity because that’s what I enjoyed doing. I ended up in the corporate world.

In college, I worked for RCA Records in Fort Lauderdale and the Miami, [Florida] area. I was a glorified babysitter; when a

recording artist came to town, I would pick them up from the airport and drive them to their interviews, the radio stations, or concerts. Artists like Tiffany, Debbie Gibson, and bands like New Kids on the Block, Poison, and Guns and Roses. I realized that I had these very famous people “captive” in a car for four to five days, so I started to interview them and sell those interviews to magazines like Seventeen and TeenBeat.

I learned that people who work in newspapers and magazines have a novel in their desk drawer, which they have been working on forever and is 500,000 words, and after a decade of writing, they are almost finished. They would hand their novel over to me because I am very good at grammar and punctuation, and I would get to the meat of the story, finetune it, and help them publish it. This turned into a side gig. During the day, I worked in finance and by night as an editor. As word spread, I received calls from agents to help their authors fine-tune their manuscripts. I did this for 20-plus years, and I ended up with six different books that hit the New York Times Bestsellers list, all of which had other people’s names on the cover—this gets old after a while.

At one point, my wife took me aside and said, “I know you want to be a writer; let’s find a way to make this happen.” We were kind of stuck; we had a big house in Florida, a boat, and all the expenses. Our monthly bills were around $12,000, so I could not just walk away from the corporate job without making drastic changes. We sold everything and bought a tiny duplex in Pittsburgh; we rented out one side and lived on the other. This helped us get our expenses down to almost nothing and live off the savings until I finished my first book.

What are two qualities that make a great thriller or horror book?

In a great thriller, the readers need to want to keep turning the page. With a horror novel, they have to be scared to turn the next page. My stories, I like to think, are primarily suspense novels, and I may include science fiction, horror, or some other element in them.

What format do you follow when writing a book?

My format has changed over the years; when I first started, I would write up the scenario and run with it, and I did not know exactly where the story was headed. This is how Stephen King writes. King famously says, “If you don’t know how the story will end, your reader will never figure it out.” It’s a fun way to write a book, but you have a lot of wasted words at the end of the process. I write a lot with James Patterson, the first book we co-wrote, we made it up as we went. At the end of the writing, James showed me all the extra work we had done to reach the finish line. To contrast that method, he sent me an outline for The Noise, and we wrote that book together with the outline. I saw how quickly the process went and how much easier it was.

In today’s world, I write the background blurb in 200 words, describing what the story will be. I come up with the title, and I create my characters. And once I have that I create a detailed outline and write as much down on paper. By doing this, I can write the book much faster, and if I don’t know where the story is going, I go for a five-mile run, and while running, I think about what comes next. With the outline, I know what comes next, so I can use my running time to think about how I can make what comes next even better. I end up with a tighter, faster, and stronger story.

What challenges did you experience when publishing your first novel?

My first book was Forsaken, and when I wrote this book, I knew how to write a story because I had been doing it for a very long time. In the book, I had to explain where the wife bought a journal, so I had her walk into Needful Things and buy it there, which is from Stephen King’s novel, and I got King’s permission to use it in the book. When I was seeking a literary agent, I thought I had a slam dunk, I had a strong story, and Stephen King’s blessings to use characters from his writing. I made a big mistake when I used a form letter for querying agents. I did not check the agent’s format for submitting a manuscript. I sent

out 200 queries and did not get much of a response; I learned you need to follow the agent’s format. I decided to self-publish and sold 250,000 copies. With my second book, I sent out 53 queries and received 14 offers. This time, I followed the agent’s instructions for a query.

How has autism helped you write your books? At what age were you diagnosed, and what led to your diagnosis?

Having autism has helped me write books; they are very detailed, they have crazy plotlines, and I am able to keep it all straight in my head, and I know it’s because I am autistic.

I was born in 1971, so they did not really diagnose autism much back then. I was the quiet little “problem kid” in the corner. I went my entire young adult life with autism, not knowing that I had it, but I knew that I was different and did not understand why. When I was in the corporate world, I had a lot of trouble getting along with the people I worked with. I was extremely good at my job, which is why they kept me. So, the company sent me to anger management classes. I was in one of those classes with a therapist, and 30 minutes in, she asked me, “Have you been assessed for autism?” She gave me a couple

of tests and explained to me what autism was, and everything began to click. Once I had the diagnosis and worked with people who specialized in autism, that’s when things really began to change for me. I was able to get a handle on my life and my career and move forward with focus.

Having autism has helped me write books; they are very detailed, they have crazy plotlines, and I am able to keep it all straight in my head, and I know it’s because I am autistic.

Do you have any writing rituals or favorite places to write your books? My ritual is having my cat Frishma or dog Rudy next to me on the floor as I write my manuscript on my laptop.

For me, I started to write while in the corporate world, and I worked 60-80 hours a week, and I tried to write in between. I would listen to a thunderstorm soundtrack, and this would prepare my mind for writing. The soundtrack would kick my brain into the writer’s mold. When I was working corporate, I would put on the headphones, play the thunderstorm, and quickly pound out 200 to 300 words in a few minutes.

Now that I write full-time, after I get my coffee early in the morning and turn off the internet, I write at the same time and place each day. I write about 2,000 to 3,000 words a day. Once I hit that number, I turn the internet back on and do the business side of being an author. My books are in 150+ countries, so I have emails coming from everywhere and a lot of interviews.

What tips would you give to a young adult with autism who desires to write a thriller or horror novel?

Definitely read a lot. I had no formal training in writing, but I learned how to tell a good story because I read a lot of good stories. There’s a structure in the story, and as a person with autism, you will pick up on that structure, you will see the pacing elements, a twist happens here, and this is where we go into the climax of the story. My mind grabbed all that. If you read a lot, that structure will get stuck in your head.

You have to practice writing and do it every day. It’s no different than exercising at the gym. I feel that there’s a writer’s muscle, and if you work it every single day, you get better and better; if you tackle it once or twice a week, you won’t get the results you’re looking for.

What advice would you share with a writer struggling with finding an agent or publisher?

You gotta keep at it. Definitely listen to literary agents or publishers’ advice. If somebody tells you no, see if you can get the reason, they said no. This can be tricky because a lot of agents will just ghost you and not respond. I read every one of my reviews, especially the bad ones, because they point out what’s wrong with the story. If something is worthwhile, I want to make the corrections and work it into my next book.

How does your wife encourage your writing?

If my wife had not pushed me to make the financial changes, I would probably still be working the corporate job I hated because that was safe. Autistic people love patterns, so changing my pattern was very scary to me because I was making decent money. So, having someone in my corner pushing was huge. She has a real estate business, and we work together to bounce ideas off each other. Sometimes, I have an idea for a book and write a few chapters; she is the first person to read it. If she likes it, I keep going; if not, it goes in the trash, and I try something else.

What are some unique methods you use to market your books?

Wow, that is tricky. It changes all the time. That’s one of the reasons I love working with James Patterson. He comes from a marketing background. He was in advertising before writing books. One of his early marketing strategies for a book was using a Toys R Us theme song. He comes up with crazy ideas, and that’s what I also do.

I interviewed Madonna and asked her what she does to market her products, and she said, “I make a list of what everyone else is doing, and once I’ve composed that list, I create a list of what no one else is doing, and that’s what I do to promote my albums and books.” I look at what everyone is doing and come up with something no one else is doing. I find in today’s world one of the best ways to promote your book is through social influencers with blogs and videos on TikTok or Facebook. You give them a copy of your book; they will write a review and share it on their platform in videos and it generates clicks. I’ve seen a blogger sell more books with a review than The New York Times

What did you enjoy most about writing The Noise with James Patterson? And how did you build that connection and make your different writing styles synchronize?

It was fun for me and was the first book I wrote off an outline he gave me. The Noise is such a fast-paced, crazy story. Patterson told me, “I’ve come up with an idea for a horror novel that no one has done yet.” I didn’t believe him until I saw the outline. We wrote six different endings and voted to decide the ending.

Your latest thriller is Behind a Closed Door; what are some twists in this book and why did your publisher use puzzle pieces for the cover?

It was originally sold as 50 Shades meets David Fincher's The Game and both of those have puzzle pieces. This story has a lot of different elements coming together that most people would not expect. It’s about a husband and wife who are having marital problems and they see a therapist. During the therapy session the therapist recommends they download an app. It’s essentially Truth or Dare for adults, so they download this app, and the app gives tasks; the first few are pretty tame, but the tasks keep getting more taboo as things go on. Ultimately, the wife gets one that says, “Would you kill a stranger to save someone you love?”. Her friend clicks yes because he thinks it’s a joke, and a map comes up with a pen and a timer. From there, things really escalate and get out of control.

What was the inspiration for Behind a Closed Door? How did you develop the characters in the book?

What actually spawned the story? I had the characters in mind, Abby and Brandon, for a really long time, but one night, as my wife and I were talking over dinner about a house she had just bought in Georgia with seven bathrooms, I remarked, “You

should use the company Bath Fitter. They come in and give a facelift to a bathroom.” I just mentioned it casually at dinner that night, and later, my wife and I both noticed advertisements for Bath Fitter on our phones and social media feeds. We did not type it into anything; we only spoke it out loud.

I researched and discovered that in our phone contracts, we give providers permission to listen and use the information they gleam for advertising. That’s creepy as hell! Your entire life is on your phone. Where you go, where you’ve been, what you’ve viewed, every conversation, your phone knows more information about you than you know. The idea of the book is what happens if that information falls into the wrong hands.

What are some characteristics that make an amazing author?

In the thriller world, you have to keep the reader turning the pages. I have a cliffhanger in every chapter, and if it does not have one, I turn it around and make sure it does. You have to be a prolific writer and put out a lot of books. You cannot write one book every five or six years. You need to be in front of people on a regular basis. In addition to being a good writer, you need to get your name out there.

How have you been able to avoid settling into one genre but bounce between thriller, suspense, and horror?

I knew I wanted to do that from the beginning. I know quite a few well-known writers, and I asked them about this. Dean Koontz gave me spectacular advice, “If you want to use multiple genres as a writer, you’ve got to do it from the beginning and find a common thread.” My first book was a horror, my second was a thriller, my third one was a horror, and then I went back to thriller; by bouncing back and forth, my audience came with me, so Dean was right. Patterson gave me the same advice; his first book was The Thomas Berryman Number which nobody has a copy of, but his second book was Along Came a Spider, which was one of the top-selling books ever. He followed that with a book about a serial killer,

followed by another serial killer, and he kept following that formula because that’s what everybody wanted but he got burnt out and decided to write the book When the Wind Blows about a girl with wings, and his fans completely turned on him because it was so different and they didn’t expect it.

Who are some authors you have had on your podcast, Writers Ink? What have you learned from those authors that enhanced your writing?

I picked everybody’s brain. We had Dean Koontz, James Patterson, Karin Slaughter, Lisa Gardner, and just about everyone you could possibly think of on Writers Ink. One of my books, A Caller’s Game, was picked up for a movie, and I was asked if I could write a screenplay, so I booked Gillian Flynn to learn how she wrote the screenplay for Gone Girl. I wanted to hear Gillian’s entire experience with writing a screenplay to understand the process.

What is something you wish everybody knew about autism?

For me, eye contact has been a big thing; for me to follow a conversation, I cannot look a person in the eyes. I have to look off to the side and focus on something else. If I do look someone in the eyes, I have to say to myself repeatedly, “Keep eye contact. Keep eye contact.” And because of this, I am not paying attention to the actual conversation, which is the opposite of what neurotypical people do. People think because I am not looking at them or my eyes are jumping around, I am not paying attention to them; I wish people would realize that is not the case. If I am not looking at you in a conversation, I am paying attention.

Video interview lightly edited for publication.

J.D. Barker is a New York Times and international best-selling author of numerous novels, including Dracula, The Fourth Monkey, and his latest, Behind a Closed Door. He is currently collaborating with James Patterson. His books have been translated into two dozen languages, sold in more than 150 countries, and optioned for both film and television. Barker resides in coastal New Hampshire with his wife, Dayna, and their daughter, Ember.

�� jdbarker.com

SQUARE-FACEBOOK facebook.com/TheRealJDBarker

Ron Sandison, MDiv., works full-time in the medical field and is a Professor of Theology at Destiny School of Ministry. He is an advisory board member of the Autism Society Faith Initiative of the Autism Society of America, the Art of Autism, and the Els Center of Excellence. Ron holds a Master of Divinity from Oral Roberts University and is the author of A Parent’s Guide to Autism: Practical Advice Biblical Wisdom was published by Siloam, and it is about Thought, Choice, and Action He has memorized over 15,000 Scriptures, including 22 complete books of the New Testament. Ron speaks at over 70 events a year, including 20-plus education conferences. Ron and his wife, Kristen, reside in Rochester Hills, MI, with their daughter, Makayla.

�� spectruminclusion.com

✉ sandison456@hotmail.com

SQUARE-FACEBOOK facebook.com/SpectrumRonSandison

By Marlene Ringler, PhD

My son recently celebrated his 50th birthday—a time to celebrate his achievements, to help him continue to deal with his sense of who he is in today’s troubled world, and to honor his wonderful collection of family members, work colleagues, and friends. He embraced the moment with an elevated sense of joy and happiness. Given that my son lives in the Middle East, his ability to express such immense happiness and pride was moving in a way that deeply affected me as he was diagnosed nearly 30 years ago with high-functioning autism (HFA).

We know that HFA is a subcategory of autism. A person with HFA usually displays high levels of cognitive functioning but is stymied when trying to understand what we would describe as typical social encounters, often struggling to make sense of social interactions and behaviors. Social communication skills, including deciphering nuances, often frustrate those on this end of the autism spectrum, and my son expresses his frustration so often, especially when he is with his family. Messages, cues, and subtleties often confound and frustrate my son, who is an excellent problem solver, capable of intellectualizing and explaining even the most complicated issues, such as political positions and the behavior of world leaders.

So, imagine what it must feel like to a 50-year-old autistic adult when sirens blast, warning of incoming missiles, when going to the grocery store only to find the usual supply of basic goods suddenly disappearing from the shelves, when public transportation is ground to a halt, or schedules change abruptly due to concerns of terror attacks. Imagine what it feels like when order, predictability, and rules are abstract concepts that guide and influence our behaviors during times of peace but are certainly not reliable markers during war times. What we depend on to give our lives a sense of purpose and stability has disappeared, and our daily routines need to be revamped and changed almost daily.

Disruptions in work schedules, medical services, and the availability of goods and services have become the norm for my son, who often shares with his family his utter frustration at not being able just to do what he does on any ordinary day.

Living in a war zone, there are no such things as ordinary, routine, or typical, and the threat of harm and the existential threat to living haunt him each day.

My son struggles to make sense of it all, to try to function in a topsy-turvy world that has become upside down. And yet, ironically, as an autistic child, adolescent, and young man, this pretty much has defined his world, at least as he has described it to his family, therapists, and social workers over the years. His perception of the world, as much today as it has been as he was growing up as an autistic, is different but not damaged or wrong or sick, as it is his world. We, the neurotypicals, must and should learn to understand, respect, and accept that autistics, like my son, are not mentally incapacitated but are widely neurodivergent in their understanding of life and their world.

Living in a country at war changes us in ways we never thought possible. Trust, confidence, and a sense of well-being seem to be elusive as we, the neurotypicals among us, make a supreme effort to come to terms with the reality that our world and its citizens are sadly flawed and that what we had always assumed to be true is now questionable.

And so, for my HFA 50-year-old son, his world, living in a country at war, is even more precarious, fragile, and threatening.

And yet, despite it all, my son remains an optimist. He truly believes that people are good and do not mean to cause harm to him or anyone else. My son believes that at the end of this conflict, his homeland will be a safer, happier, and more secure place to live. He believes that the people who are confrontational and aggressive today are reacting to the dreadful daily pressures and that when this war ends, these same people will be kinder and gentler. This is his world perception, naïve, perhaps, but touching nonetheless because of and perhaps despite this naivety, so typical of persons on the spectrum, his country can become, once again, a happier, more comfortable place to be.

So happy birthday, dear son, and may your dreams of a world at peace come to be.

Marlene Ringler, PhD worked as a professional in Maryland before moving to Israel in 1986. While living in the United States as the mother of a child on the autism spectrum, she devoted much of her personal and professional time to learning about the special needs and challenges of children on the spectrum. Her book, I AM ME, My Personal Journey with my Forty Plus Autistic Son, published by Morgan James and available on Amazon, addresses the issues involved in raising an autistic child into adulthood. As her child aged, Dr. Ringler learned to identify and take advantage of both public and private services available to support people with exceptional needs. In the process she became aware of the critical absence of support systems and services for adults on the spectrum. These and other related matters have become the focus of her research and writing over a period of several decades. Her articles addressing a variety of vital issues have appeared in professional and national publications in the United States and elsewhere. She is a public speaker who speaks passionately about persons on the autism spectrum. Dr. Ringler is recognized as an advocate for persons with disabilities..

SQUARE-FACEBOOK facebook.com/AuthorMarleneRingler SQUARE-X-TWITTER @MarleneRingler

LINKEDIN linkedin.com/in/dr-marlene-ringler/

By Lavelle Carlson, MSLP

Books are so important for learning. But before discussing books, it is important to discuss how children learn words and language. Then, we will consider how to use books to facilitate this learning.

Children are born with an innate ability to learn language. However, several things must happen for a child’s language to thrive.

1. They hear words.

2. They hear the same words repeated many times.

3. They hear words related to a person or thing.

4. Emotion must be attached to the words.

What are the stages of words and language development?

1. Babbling and cooing

2. Creating repetitive sounds that have meaning, as in “dada” and “mama”

3. Combining words (more milk) and creating short sentences (“go park” for “go to the park”). The grammar aspect of language will kick in later (subject + verb + object, as in “I want milk.”

Parents and caregivers are crucial for setting their children up for success in literacy. Yes, television will give children access to sounds and language. However, the parents and caregivers are more important. Why? The parents/caregivers will respond to the babbling in a personal and loving way—smiling, pleasant physical loving, and a back-and-forth babble. They will teach back-and-forth communication in which one says something and the other responds.

Okay, here is the biggie! Books have a huge influence on learning language and preparing children for school. According to Brigham Young University, a five-year-old who has not been

read to daily will enter kindergarten with far fewer hours of “literacy nutrition” than a child who has been read to daily from infancy.

Reading books in a fun way for children does three things:

1. Social interaction combined with reading books and fun play provided by the caregiver gives children a head start in learning speech, language, and pre-reading. Listening to books daily, a child will hear animal sounds, speech sounds, and language. This is very evident in the story Corky the Quirky Cow and the Cuckoo Concert. When listening to the book, the children learn animal sounds that will later translate into manipulating speech sounds for reading. Young children will understand that they see a cow but hear “moo.” In the same way, later in school, they will be able to associate, “I see the letter ‘b,’ but I hear the sound /b/.

2. Another asset of caregiver book reading to the child is that the child who has been reading books about farm animals will associate the word cow with the picture of a cow even if they have not seen an actual cow on a farm. This gives them the knowledge they would not have if they had not had books read to them. Associating words with pictures in one’s mind (visualization) increases reading comprehension later.

3. Another important aspect of reading beyond learning words, language, pre-reading, and knowledge is socialization, empathy, kindness, and dealing with daily problems. Look at the old fairy tale of Little Red Riding Hood. That story was filled with words to warn little children of strangers. Books written today do that as well. For instance, in the book Do Not Snuggle with a Puggle, Wally, the wallaby, had to learn the hard way to be careful with whom he could trust, just like Little Red Riding Hood

How to choose books to read to children

Consider books with the following elements:

• Rhyming (Eek! I Hear a Squeak and Corky the Quirky Cow)

• Repetitive dialogue (Slowly Slowly Goes the Sloth)

• Large print

• Humorous (Corky the Quirky Cow)

• Bright Colors (Bee, Honey Bunny and Me)

• Not too much text on the page (Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus)

• Life lessons (Do Not Snuggle with a Puggle)

Reading tips:

• Make reading an interactive experience. Use mini toys, coloring pages, cut-outs, and games like mazes. These can often be downloaded on the author’s website.

• Choose books of interest to the child

• Wordless books can also be effective, depending on the child and the adult reader

• Point to words, particularly those that represent sounds. For instance, in Corky the Quirky Cow, point to the word “moo” as you read the sentence that has it. Pause and wait for the child to respond.

• Allow children to help turn pages as that teaches them the directionality of page turns.

On a side note – caregivers and teachers should always remember that not every child is drawn to books. Here are a couple of suggestions for those who are not drawn to reading:

• Allow the child to choose books on topics that interest them. For example, if they like tractors, choose a book that

features tractors/farm equipment like Corky the Quirky Cow.

• Make story time interactive. Use some of the ideas I’ve previously mentioned and, occasionally, ask the child, “What do you think ______ will do on the next page.”

• Expanding on point 2: Allow the child to turn the page. Ask the child what will be on the next page. Download activities and coloring books related to the storybook from teaching sites or check to see if the author provides coloring pages and downloadable activities on a subscription website https://www.slpstorytellers.com/ register-2/

Learning to read begins early and is facilitated by children hearing books read to them daily by caring caregivers. Read, read, read, and play today!

Lavelle Carlson is a retired speech/language pathologist. She began her studies at the University of Tulsa, was married, and then traveled the world, living in England for one year and Norway for nine years. She lived in several states after returning from overseas. It was at that time that she went back to school in Oklahoma, receiving her Masters in Speech/ Language Pathology at the University of Tulsa. When she began working with young children, she began writing for speech and language. After her retirement in Texas, she has continued to write poetry for her own satisfaction and children’s storybooks to, hopefully, increase literacy in young children. She also continues to develop materials for her website to provide inexpensive teaching materials for speech/language pathologists and teachers �� slpstorytellers.com

By Jake Edgar, MS

Navigating the educational landscape can be particularly challenging for students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and their parents. From ensuring access to appropriate resources to fostering understanding among educators and peers, educational advocacy plays a crucial role in supporting these students. By collaborating with flexible school systems, parents can build a support system that is best for their students' academic needs and beyond.

Educational advocacy highlights the collaboration between educators and parents to serve students who need attention, accommodation, and adaptability. To understand how educational advocacy can empower students with ASD, it is important first to understand the risks of staying silent on their development.

Many students with autism struggle to succeed in educational environments that assume they can learn with the same

attention as neurotypical children. Without proper advocacy, they may struggle to succeed in environments that do not account for their specific strengths and challenges. Challenges students with ASD may face inside the classroom include:

• Difficulty engaging and socializing with peers

• Experiencing sensory overstimulation

• Cognitive difficulty with understanding course material

• Facing unexpected changes in routine

By not addressing the challenges of a traditional learning environment proactively, students with ASD may experience long-term consequences in their skill development. This neglect can result in academic frustration, social isolation, and diminished self-esteem. Many students with ASD require support in traditional educational systems to reduce the barriers they face and foster their academic and personal growth effectively.

Effective educational advocacy involves collaborative efforts to ensure the student's needs are met. One way educational advocacy can be utilized for students with ASD is through creating an appropriate educational plan tailored to their best interests. Another avenue for educational advocacy consists of staying aware of special education laws and policies to ensure students with ASD receive the necessary support and accommodations.

Students in special education tend to benefit significantly from educational advocacy for the following reasons:

• Tailored support: Educational advocates work closely with students, parents, and educators to meet individualized needs. They help create personalized learning plans, identify appropriate accommodations, and address any barriers to learning.

• Navigating systems: Special education can be complex, involving various legal and administrative processes. Advocates guide families through these systems, ensuring they understand their rights, options, and available resources.

• Promoting inclusion: Advocacy encourages inclusive practices within schools. By advocating for accessible classrooms, adaptive technologies, and supportive environments, students can fully participate in academic and social activities.

• Building self-advocacy skills: Advocates empower students to express their needs, preferences, and goals. As students learn to self-advocate, they gain confidence, independence, and a sense of ownership over their education.

• Enhancing communication: Effective advocacy fosters open communication between students, parents, teachers, and school staff. When everyone collaborates, students receive consistent support and encouragement.

In summary, educational advocacy ensures that students with special needs receive the best education tailored to their unique abilities and aspirations.

Structured expectations can greatly benefit students with autism. A classroom environment with supportive practices can provide that opportunity.

An Individualized Educational Plan, known as an IEP, can provide your student with the most practical care for them. An IEP serves as a formal contract between the parent of a student and the school the child attends. The general objective of an IEP is to set learning goals for the student, understand the student’s needs and limitations, and clarify what services the school will provide for that student. IEP goals for students with ASD can include:

• Educational and learning requirements

• Social and communication goals

• Behavioral and emotional needs

Parents of children who struggle with ASD should contact their school about an IEP as early in the child’s educational career as possible. When attending meetings for an IEP agreement, parents should consider the ability and skill of the school's special educator(s) to meet their students' needs.

If an IEP seems more assistance than your student needs, a 504 plan is another potential avenue (more on this option below).

Advocacy is crucial for students with an IEP during meetings. Here are some reasons why:

• Empowerment and self-advocacy: When students actively participate in their IEP meetings, they learn to advocate for their specific educational needs. This empowerment fosters self-advocacy skills, which are essential for their future success.

• Understanding and ownership: Students who understand their IEPs are more likely to work toward accomplishing their goals. By participating in the process, they gain a deeper understanding of their classification, modifications, and accommodations. This ownership leads to better outcomes.

• Post-secondary transition: Active participation during IEP meetings correlates with positive post-graduation outcomes. Students who engage in their IEP discussions are more likely to be employed or enrolled in higher education after graduation.

• Individualized approach: Advocacy ensures that the student’s unique needs, abilities, and goals are considered. It allows for tailored support and accommodations, promoting a more effective learning experience.

Remember, involving students in their IEP meetings is a powerful way to promote their growth, self-awareness, and educational success.

Students who can participate in a general education setting with their peers but may need some accommodations could benefit more from a 504 plan. With a 504 plan, students with autism attend regular classes, only receiving support as necessary. For example, accommodations provided by a 504 plan may include:

• Assistance carrying school supplies

• Larger fonts on coursework for accessibility

• More time on tests

• Preferential seating to reduce distractions

Unlike IEPs, parents are not as involved in the decision-making. 504 plans vary by state and school district and are determined based on the student’s diagnosis; however, both 504 plans and IEPs can be reevaluated and readjusted as needed.

If your student with ASD would benefit more from another resource, alternatives like involving students in behavioral intervention services, employing occupational therapy, or other support systems might be necessary. Parents should research the resources available to them and reach out to their community for recommendations.

Special education laws ensure schools across the country provide care for students with learning disabilities. The most notable one is the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Parents of children with special needs should become familiar with special education laws.

Knowing the laws for special education is essential for effectively advocating for the rights of children with ASD and ensuring they receive the appropriate support and accommodations in school. For example, IEPs should be a collaborative effort between parents and educators in which both parties agree on the best practice for that student. The final IEP should be high quality and reflect the student’s needs. Parents of children with ASD should check each state’s

Remember, involving students in their IEP meetings is a powerful way to promote their growth, self-awareness, and educational success.

procedure for filing a dispute if the school system does not comply with special education laws.

Not every student can learn the same way within general education, so empowering students with ASD through educational advocacy can significantly impact their well-being. By advocating for tailored support and accommodations, students with ASD can pursue equitable access to education and opportunities for growth. This proactive approach not only enhances their academic progress but also fosters a supportive environment where they can thrive.

Springbrook Autism Behavioral Health offers special education for children and adolescents with ASD using applied behavior analysis-based treatments. Contact Springbrook to learn more.

References

Al Jaffal, M. (2022). Barriers general education teachers face regarding the inclusion of students with autism. Frontiers in psychology,13, 873248.

deBettencourt, L. U. (2002). Understanding the differences between IDEA and Section 504. Teaching Exceptional Children, 34(3), 16-23.

Gargiulo, R. M., & Metcalf, D. (2015). Teaching in today's inclusive classrooms. Cengage Learning

Kurth, J. A., Love, H., & Pirtle, J. (2020). Parent perspectives of their involvement in IEP development for children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities,35(1), 36-46.

Mulick, J. A., & Butter, E. M. (2002). Educational advocacy for children with autism. Behavioral Interventions: Theory & Practice in Residential & Community-Based Clinical Programs,17(2),57-74.2

Ruble, L., McGrew, J., Dale, B., & Yee, M. (2022). Goal attainment scaling: An idiographic measuresensitive to parent and teacher report of IEP goal outcome assessment for students with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1-9.

Wangmo, K., & Wangmob, T. (2021). Lived-Experiences of Parents’ Involvement in Individual Education Plan Development for a Child with Autism Spectrum Disorder. European Journal of Medicine and Veterinary Sciences-Novus,2(1), 33-63.

Jake Edgar is the Director of Education at Springbrook Autism Behavioral Health in Travelers Rest, South Carolina. Jake began his career at Seneca High School as a Special Education Teacher, directing the Transition to Independence Program. This program works with students with severe intellectual delays to develop adaptive, functional, and employment skills to help them lead independent and successful lives. Jake oversees all educational services Springbrook provides and leads the educational team to provide the individualized education and curriculum the students need to succeed. In 2021, Jake founded the Carolina Special Education Advocacy Group. This group works to provide advocacy to families to guide them through different processes, such as Individualized Education Plans and other areas where support is needed. �� springbrookbehavioral.com

By Meshell Baylor, MHS

"The attempt to escape from pain is what creates more pain."

– Gabor Maté

–

There is a joy in loving your child every day you watch them grow and transition from one milestone to another; it almost feels like watching a miracle daily. It is a journey of watching them reach one level of growth to another, from saying their first word, taking their first steps, and actively playing with you. These milestones are huge to a parent, but there are also times when a child has yet to make those milestones happen, and the exceptional parent becomes worried.

According to the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC), milestones are considered a checklist to help identify

a need for screenings or interventions. When a child is not meeting those developmental benchmarks, they are assessed, screened, and evaluated. In the middle of gathering data, trying to remember when your child did any form of a milestone, a sense of grief and denial can impact a parent. It is common for a parent to feel there is nothing wrong and their child is perfect, but not allowing them to accept a diagnosis can be challenging for the parent or caregiver to overcome.

Denial is defined as the action of declaring something untrue. There are times when a parent struggles to come to terms with

the fact that their child may be unique. They tend to challenge what the professionals say and not heed the warning signs of what family members and close loved ones are trying to say in advocating for the wellbeing of the child. The parent/caregiver is often trying to fight against the diagnosis because they are in a state of shock. Many times, loved ones and professionals see the warning signs of developmental delays before the caregiver does, and some families decide to turn a blind eye to their child's delays. If you are a family member or caregiver who wants to help ease the parent or guardian into the transition of acceptance, here are some tips.

1. Be receptive

In addressing the concerns of advocating for your exceptional loved one and parent, the best answer is to talk to them about their feelings and be open and receptive to their dialogue.

2. Be supportive

Never force a parent into acceptance if they are still coming to terms with the idea that something may or may not be impacting their child.

3. Be respectful

Every parent is different when going through a particular stage. Learning how to navigate the next step in forming an intervention is challenging. So, be receptive to their concerns, be supportive of their decisions, and be respectful when addressing any form of concern. This is not easy, so try to be respectfully delicate when helping.

4. Be resourceful

Learning how to track your child's milestones and developmental stages can be challenging. For resourceful information, such as the Ages Stages Questionnaire (ASQ), check the CDC, or consult your primary care physician.

5. Be present

Sometimes, there is power in just being present. Being present might involve attending the child's doctor appointments, sitting with them when they get the news of a diagnosis, and encouraging the parent by being their soundboard. Be present when they go to their local agencies for assessments; the goal is to be there so that they do not feel alone.

While being present, it is okay to establish a family intervention for the exceptional parent. It is okay to let them know that whatever they may feel in the presence of trying to navigate which steps to take for their child, they are loved. There are no expectations to be placed upon them nor judgment; allowing them to see the many faces of their village is the biggest support any parent can receive.

When we rest in a state of denial, it can hold the ones we hold dear back from receiving the support they need. The initial response to detect, react, and advocate for your child is being a caring guardian. When questioning whether a child is making developmental milestones, keep a notebook of their milestones, record them, and find activities online that you can use at home to ensure they are on the right track. Take comfort in knowing that being alert, assertive, and supportive of your loved ones does not make you a bully but an ally. Caring about the needs of your exceptional family is considered a high priority, so if you are a caregiver or aunt who identifies a concern the parent has yet to see, speak up. When a milestone is not reached, it is not the end of the world. It only means that we need to work on it, evaluate it, and implement strategies to help the child achieve it.

It is considered a red flag when a child is not sitting up, talking, or making any connection. The red flag is not bad but a notice to act accordingly. As a parent of two children on the spectrum, there were times that I as a parent did not see the warning signs when my sister did. In my eyes, my child was healthy, but he had limited eye contact, and he was not speaking or conveying his wants and needs. I was enraged when my sister, a special education professional, said he needed an assessment. Like many parents who struggle with the denial stage, I stayed in a state of denial and shock. It took time to say the word “assessment” without bursting into tears. Once we identified my child’s autism, I looked and noticed my village was there to support every decision and action I took to help my exceptional child achieve every developmental milestone. Remember, it takes a village to raise a child.

References and Resources

CDC's Developmental Milestones https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/milestones/index.html

ASQ.-3 Ages and Stages Questionnaires https://agesandstages.com/products-pricing/asq3/

Meshell Baylor, MHS, is a mother of four children—two of whom are on the autism spectrum. She serves her community as a social worker and advocate in the Los Angeles area. She has a Bachelor’s degree in human services from Springfield College and a Master of Science degree in human and social services. Meshell continues volunteering and giving within her local area while serving the special needs community.

�� meshellbaylor.wixsite.com INSTAGRAM @imalittlebigb

�� Center for Autism and Developmental Disabilities

By Jeremy Rochford TI-CLC, C-MHC, C-YMHC

Up-Up.

Down-Down.

Left-Right.

Left-Right.

B-A

Start….

Growing up in the 80s and 90s, there weren’t too many things that mattered more in my life than playing Nintendo after school and on the weekends. One game in particular, Contra, was my absolute favorite. Beyond its spectacular gameplay and the purely awesome 8-bit graphics, Contra had something genuinely unique to offer.

It was the first game I ever experienced that came with a cheat code.

A cheat code?

Yes, a cheat code.

And not just any cheat code, but the most epic of cheat codes ever!

If you entered the keypad sequence up, up, down, down, left, right, left, right, B, A, start at the main menu as it was “booting” up, you would begin the game with 30 lives.

Think about that: when most Nintendo games started you off with a measly three lives, finding a way to 10x your existence was pure magic.

Especially in a game where you’re being shot at.

If we relate that to being an “adult,” imagine going to get your paycheck, and it’s 10 times what it’s supposed to be because someone taught you a more creative way to enter your bank’s log-in and passcode.

You’d feel pretty good about your current situation, right? Right indeed!

But, alas, those were simpler times.

And as my childhood gave way to my 20s, which gave way to my 30s, which now has given way to my 40s, I’m not going to lie; there are times I wished for a cheat code to become a better parent, spouse, and overall adult.

Unfortunately, it seems one doesn’t exist.

Yeah, sure, there’s the lottery. But let’s be honest, if you’re bad with money, having more of something you’re bad at isn’t going to make you better. So, playing “Grandma’s lucky numbers.” isn’t a sustainable “cheat code” strategy.

But then, my children entered the conversation.

First came my son’s autism diagnosis, which led my wife and I to start exploring a world we knew very, VERY little about. And, while trying to understand better our son’s diagnosis and how to best parent him within it, we started to notice a lot of similarities between our daughter’s behavior and what was being quantified as ASD-1 or Asperger’s syndrome.

Needless to say, we were growing more intrigued.

So, we decided it might be helpful to get her tested as well, and within a few minutes of her appointment, we discovered that both our children were on the spectrum.

Apparently, we had unlocked the bonus level of parenting!

If I’m being honest, I was a little taken aback at first, like most people who would find themselves in this situation. It was a smidge overwhelming to realize that 98% of the parenting resources I’ve ever read, watched, and consumed were now irrelevant because you cannot parent a neurodiverse child the same way you would parent a neurotypical one.

It’s not better, it’s not worse, it’s simply different.

With that reality now evident, my feeling(s) of overwhelm started to fade because having a diagnosis FINALLY gave us a clear path on how to parent our children in a way that best suits their needs, emotions, and strengths. Interestingly enough, though, the more I learned about my children, the more I began to learn about myself. The more answers I had

about their behaviors, the more questions I had concerning mine. And the more I recognized the traits of autism in my children, the more I noticed similarities in me.

This begged the question: Am I autistic, too?

With all the evidence that suggested it, I felt I owed it to myself to get tested as well.

If only for my peace of mind.

So, I did, and the result would show that I’m autistic as well.

I’m not going to lie; there were certain things I expected to happen in my 40s: bifocals, a slower metabolism, and the music of my youth creeping into “classic rock” playlists. But an autism diagnosis? This was not something I planned for.

However, upon receiving it, almost every aspect of my life has improved.