CASA GHIRRI FRANÇOIS HALARD

dedicated to Luigi, Pao L a, a de L e e iL aria.

François Halard At C ASA G HIRRI

Luigi Ghirri was not a great traveller. Carried on the wings of his imagination, he preferred to limit his journeys to Italy, then to his region, the Po Valley, or to the shelves of his library. It was, by the way, at his large house in Roncocesi that his travels were interrupted, at forty-nine years old, the morning of 14 February 1992.

In spite of his starting in the 1970s, Ghirri’s work was far from the black and white so widely practised at the time. He developed a very personal language that was quite different from the neo-realist and humanist photography then still dominating the European scene. His freedom of vision, pioneering use of colour and of small format, interest in landscape, rock and blues, make his work more like that of American photography by Walker Evans, Robert Frank, William Eggleston, Stephen Shore and the like.

Like Ugo Mulas, another “Italian exception,” he would play a crucial role both in theoretical analysis of the image and looking for new ways to photograph.

Laura Serani July 2013Concerned with changes in the landscape, of contemporary society and the perception of the habitable world that had “become mysteriously unknown as if by enchantment”, starting with everyday places, family spaces,“i dolci luoghi”, defined and reassuring, Ghirri built his world, and in the end, his complete work.

In Portrait Robot 1 , he delegated the making of his self-portrait to household objects, giving them the mission of “showing” his imaginary, his passion for books and music, his travel plans. Later in Still-Life 2 , he wrote that certain objects were especially apt to hold memories and that, those which he photographed were true “realms of memory”.

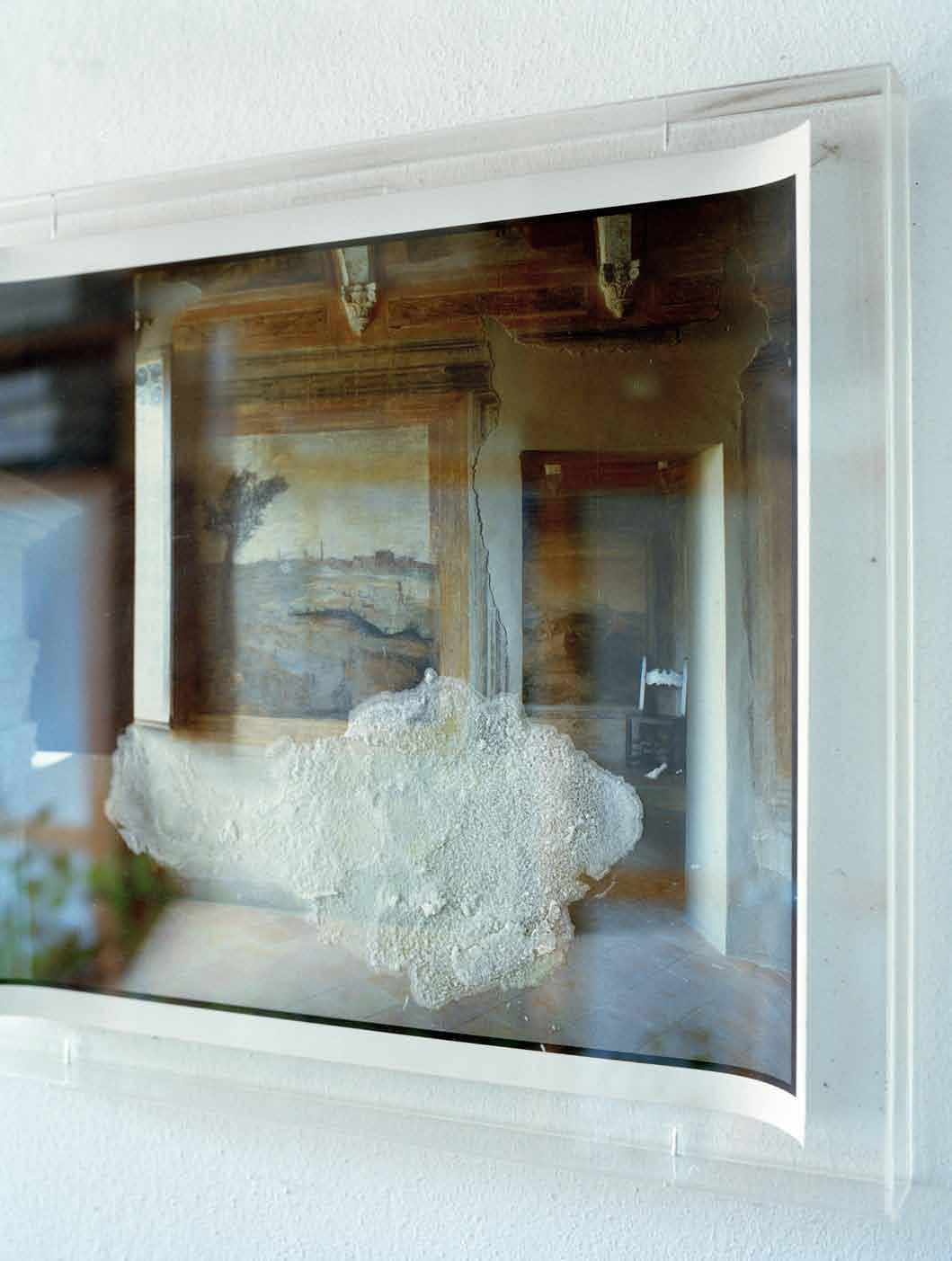

François Halard also likes to photograph private spaces, to capture the spirit of houses, and he is a master in the art of creating portraits of their inhabitants through their surroundings. When he met Paola, Luigi Ghirri’s wife, at his 2011 exhibition in Reggio Emilia, his admiration for Ghirri’s work turned into a desire to photograph the places where it had taken shape and the idea of photographing the house at Roncocesi was born. These images are the subject of the book Casa Ghirri, which follows that of Casa Malaparte, two works inspired by the world of a photographer and of a writer, both essential in Italian culture and still not well-enough known on the international scene.

Luigi, Paola and their home are no longer, and François Halard’s book thus becomes a double homage to their history and to their realms of memory, so dear to Ghirri. In the end, Casa Ghirri not only speaks of a home, but of a paradigm, a place of privacy, of memory and of the imaginary, that reflects and contains the whole of an œuvre. Photographs of artists’ and writers’ homes and studios are quite frequent, but those that feel lived-in as with François Halard are rare. His extreme sensibility brings out an empathy with places and their history, making them “habitable” and leads Halard to identify with those who have lived in them.

François Halard says that he wanted to work in the tracks of

“Still-Life, topographie – iconographie”, in Camera Austria, n° 7, pages 23–33, 1982

Luigi Ghirri, in his wake, in order to get as close as possible to his work, to the images that inspired, fascinated and deeply moved him, in a process going from admiration to a sort of discreet desire of appropriation. In the footsteps of his “notable figures” known through images or writings, François Halard attempts to draw their intimate portraits, with modesty and respect, while searching for links between their spaces and their works.

In situations dominated by absence, he thus sets up strange silent dialogues, almost establishing an exchange of roles and the places seem to vibrate, as in Ghirri’s images of Morandi’s studio.

At Roncocesi, Halard begins to see through the eyes of the other, whose place he seems to occupy, to produce that which Ghirri could have photographed himself; these new images slip harmoniously, spontaneously, into the pre-existing work. Reinterpretations, replicas, substitutions, all highlighted and claimed in the legends that refer directly to Ghirri’s work. An informed explorer and tactful observer, Halard glides from one room to another in search of the atmosphere and objects encountered in the books Kodachrome, Atlante, Il profilo delle nuvole.

Master of the house for the time it takes to accomplish his dream, with respectful affection and attention, he seeks the perfect lighting, the angle that does justice to the setting, by in his turn recreating little theatres. The frieze of a door, the corner of a window, a bouquet of flowers, toys, stacks of 33 rpm records with that of Dylan pulled out, souvenir photos, an old globe, little prints, and large portraits of women from the nineteenth century, each detail becomes an element in a lessico familiar that talks about the artist and his life. An old album placed on a table next to a pair of scissors, seems to be an allusion to the process of layering the past and the present, so common in the approach of both artists.

At times, Halard plays with direct and indirect references to Ghirri’s iconic images: the photo of the Château de Versailles park,

pale like a watercolour, as if it should take up the whole frame, shot in full light, seems to be even more evanescent. On the other hand, that of New York, taken from a low angle behind a fence made of shadows, is strengthened in its modernist vision.

The exhibition posters recall the stages of Ghirri’s development, which each time upset the codes of photography and made his emotional and cultured, spontaneous and refined vision indispensable, as was his input into critical thinking on the image.

Halard’s work gives the impression that, finally, all of Ghirri’s images are only one expression, in different forms, of the same inner mental image. By restoring to the premises an everyday poetics and an intelligence of light and colour, with a sensitivity “à la Ghirri”, Halard creates a mirror play, where the images could very well have been made by Ghirri himself. Sometimes we see, placed on a bookshelf or hung, photographs by Ghirri, who in turn liked to play with these mises en abyme by shooting post cards, drawings or pages from his Atlas.

This world of Luigi Ghirri, with reverberations of fairy tales and childhood memories, where reality recalls the imagery of an illustrated album, is very close to that of François Halard, inhabited by poetry and melancholy. Hence the complicity of their images and Halard’s original fascination with Casa Ghirri, where as the pages turn, nostalgia materialises in the places and the objects, once again protagonists in little magical theatres.

“Taking pictures, to me, is like looking at the world in a state of adolescence, renewing my stupor on a daily basis, a practice that reverses the motto of Ecclesiastes: nothing new under the sun. Photography seems to remind us that ‘there is nothing old under the sun’.”

Luigi Ghirri Paesaggio Italiano, 1989.

The house of Lu IGI G HIRRI

July 2013

The work of Luigi Ghirri, from his earliest explorations up until the early 1990s, reveals a constant that constituted one of the most salient and intriguing elements of his aesthetic: the reversal of point of view. In 1979 Ghirri wrote: “I have photographed many people from the rear ... I have sought to give each person an infinite number of possible identities, from my own as I am taking the photograph to the final one – that of the observer. The point of being actors in this way is to remind us that the search for an identity is always a difficult path.... My role, as the photographer, does not try to be that of the author, the chronicler, the spectator, or the prompter; mine is a role identical to the role of those who are photographed.” 1

In this reversal of position, in which the denial of the status of author undeniably affirms Duchamp’s theory and especially the work of Franco Vaccari, Ghirri addresses and develops the themes that became constants in his thinking. What are these themes? The exterior that becomes interior, the landscape, the image of the external world that becomes the world of the inner landscape, the site of deep feelings and sensations where photography acquires new capacities for expression, abandoning its documentary and hence merely descriptive function. Ghirri and the other photographers of his generation introduced and developed close attention to simple, everyday things. Their starting point was a model, an illustration of how to investigate a section of the visible world to be explored and in some way appropriated, which they found in certain American photographers, most particularly Walker Evans and later Robert Frank and Lee Friedlander. Photography, whether of landscape or of interiors, thus becomes an intimate document, narrating precisely the relationship between its creator,

as an individual, and the environment that surrounds the individual. We can no longer speak of a single topic of inquiry, such as landscape photography as a genre or the photography of interiors; we have to speak of a complex of intellectual and emotional relations between the external and the internal, the relations between things and the space that surrounds them. These dynamic relationships describe an internal situation, that of the artist, and a more intimate reality, the sensibility of photographers who by way of the gaze, the choice of frame, bear witness in some sense to their presence and their awareness. Luigi Ghirri’s library, in his house in Roncocesi in Reggio Emilia, contains a numbered edition of Walker Evans’ 1966 Message from the Interior. 2 This prized work surely testifies to a long-standing attention to the world of things and to the interiority of individuals from which Ghirri drew his inspiration.

It is not by chance that this inspiration is central to the earliest images in his explorations, published together in a section of his work entitled Periodo iniziale (1970), and to the images that compose his first organized projects, including Kodachrome (1970-1978), Colazione sull’erba (1972-1974), Diaframma 11, 1/125, Luce naturale (1970-1979), and in particular Identikit (1976-1979). The title chosen by Ghirri for the last of this list of projects is an emblematic one: the identikit, of course, is the technique of combining the different parts of a face to reconstruct a person’s identity. It is an attempt, with more or less plausible results, to sketch a portrait by way of an image constructed out of fleeting memories, sensations, and emotions. Ghirri’s project is to talk about himself, his own inner world, through his books, his record albums, his collection of old postcards and photographs, the objects he cares for. These items certainly have more significance than the decor selected for traditional portrait painting to show the social standing of the person portrayed: they are in fact traces, creating a breadcrumb trail that leads the spectator to unmask the artist’s personality, interests, enthusiasms, and emotions.

For Ghirri, photography is a tool for talking about himself and the places that matter to him.

The theme of the house of one’s own, as distinct from that of one’s parents, has been a central and recurrent one in Ghirri’s aesthetic. In the enormous archive of his negatives and slides in the photography collection of the Biblioteca Panizzi in Reggio Emilia one may view shots of his bedroom in the house in Sassuolo where he settled with his family in 1946 in the aftermath of World War II: he made a return visit in 1970 in order to photograph it. There are several shots of his first house in Modena, where he lived with his wife and their daughter Ilaria.

There is extensive documentation of the house in Via San Giacomo in Modena, where with his new companion Paola he took up the challenge of planning and making photographs as a profession. Different again are his shots of the house in Formigine, a modest row house in what Gianni Celati would call a perfect “geometrile” style: here it is inte -

riors that are portrayed, with details of the paintings on the walls, and again the books, postcards, and objects. And finally we reach the house in Roncocesi, close to Reggio Emilia, which for once he also photographed from outside, on a winter night, with the snow blotting out the surrounding landscape.

Moving from house to house in the course of his short life, Luigi Ghirri never set up a darkroom (he photographed chiefly in color because, as he said in 1984, “The world is in color and I photograph in color”), and never had a studio with lighting equipment (“I prefer natural light,” he said in 1990).

When he founded the publishing house Punto&virgola in 1977 he had no editorial or office staff and no storage facilities for the books. When he was in charge of events such as exhibitions or conferences, Ghirri worked at home, meeting with the photographers and writers in his dwelling, which was plainly furnished with large shelving units that housed books, magazines, prints, samples, and mock-ups.

Sometimes his house became the birthplace of ideas and projects by other artists, friends with whom he collaborated, as in the case of the 1968 work by Claudio Parmiggiani, Pellemondo. The 1973 photograph of Pellemondo, a fuzzy black-and-white globe placed on a wicker chair next to a dog whose coat resembled the globe, perched on an armchair just a few inches away, was taken in the living room of Ghirri’s house in Modena. This image became the “documentation” of Parmiggiani’s work, as he himself testified.

The house is the space that functions as the birthplace and schoolroom of intuition, in which the idea becomes a real project; its atmosphere is at once that of private life, work-space, and meeting place. Ghirri’s houses in Modena, Formigine, and finally Roncocesi were the meeting places of many friends – photographers, writers, journalists, musicians, and poets. His home thus also became a site of cultural reference and exchange accompanied by generous, warm hospitality. His library and his collection of images, photos, and postcards, vinyl records, and later music CDs were the locus of these encounters, the sources and the occasion of the exchange of ideas and opinions and of intense, heated discussion. It may be that instead of looking at Ghirri’s library and its collections in isolation, a closer study of them would tell us a great deal, revealing ar hitherto unknown side of its creator and helping us to understand much about the relations between Ghirri and his books and between him and the postcard images he selected. But that would be another chapter in a story still to be told in its entirety.

Benjamin said that “Every passion borders on the chaotic, but the collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories” 3: has anyone worked more than Ghirri on the theme of memory, on the traces of the memories made manifest in various forms – objects, postcards , newspaper clippings, atlases, drawings, books, notebooks, and all the rest? His collections and consequently his house as well become sites of creativity par excellence. The objects and images from his collection find their own order as if by magic,

— 5 ]

thanks to Ghirri’s attention to them, to the gaze he focused repeatedly and at length on these images, the gaze that voraciously and energetically devoured almost all the books in his library. It was this gaze that brought his collections together in a sphere that was entirely personal, with an aura of the fairytale. Benjamin says in his essay on collecting that this gaze is the gaze of childhood, and suggests that what regenerates the materials is their protean character: combining them in one space, the space of the collection and of course that of the house, thus restores them to life.

It is that same gaze, Ghirri’s, that broke down the differences between genres in photography and made us look at the apparently insignificant landscapes of the urban periphery, as well as the interior landscapes of the studies of Giorgio Morandi and Aldo Rossi and the interior of the house of the brothers Benati, to mention only a few of the best-known of many examples.

With affection and admiration Daniele Benati writes: “But Luigi liked interiors, especially those with natural light coming in from the left side, as in the paintings of Vermeer. He could not have cared less about the history of the house, what interested him was the disorder inside, the piling up of the objects and the arrangement of the spaces. For example, the room that used to be my bedroom.... Luigi’s photo of that room is one of his most famous and beautiful ones, and if Vermeer were alive today he would like it too. But for me it has a special meaning because that picture taught me several things that I was to say later. And this, everyone says, is a really great photo.... my old room. I had it before my eyes all day and I had never seen it, I had not even thought that you could take a photo in there. But Luigi did take it, just as he took three hundred thousand other photos, because there is nothing in the world that in itself is worthy or unworthy of being photographed or painted or talked about or described or set to music. It all depends on you, on what you know how to see or hear and on how your heart responds when you see or hear.” 4

The images shot in 2011 by François Halard in Ghirri’s house, almost twenty years after his death, capture not only the atmosphere but the world in which Ghirri lived. But these images tell us something more, as Quentin Bajac says. 5 Luigi Ghirri, an artist whose work was produced at the height of the analog era and of print photography, fully anticipated future technological changes and the proliferation of digital images; as early as the 1970s his work heralds these changes, expressed through the deconstruction of the photographic language and through the use of highly varied supports, from the form of the book to that of the album, from vinyl records to postcards. This is a world that Halard recreates for us with deep affection.

© 2013 F RANÇOIS H ALARD , Ke HR e R Ve RLAG He ID e L be RG

b e RLIN

— Texts ]

L A u RA Se RANI , Lu IGI G HIRRI , LA u RA G AS pARINI

— Proofreading ]

XXX XXXXXXX

— Translations ]

L INDA G ARDIN e R italian/english, XXXX

frensh/english

— Image processing ]

Ke HR e R De SIGN He ID e L be RG /Jü RG e N H OF m ANN

— Art direction & Design ]

tOGO www.togostudio.it

— Production ] Ke HR e R De SIGN He ID e L be RG

— Cover illustration ]

FRANCOIS HALARD m OD e N A FRO m Lu IGI G HIRRI . .???

R ONCOC e SI , 2011

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication In the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de.

— Printed in ]

Ge R m AN y

— ISBN ] 978-3-86828-397-6

Ke HR e R He ID e L be RG b e RLIN

www. K e HR e RV e RLAG CO m

— TANK YOU ]

Paola Bergonzoni, Adele e Ilaria Ghirri, Arrigo Ghi, Laboratorio Ghi, Laura Serani, Robert Morat, Robert Morat Galerie, Jessica Backhaus, Bartolomeo Pietromarchi, Isabelle Dupui Chavanat, Togo, Francesco Forti, Patty Di Gioia, Nicole Forti, Roberto Rabitti, French Fiocchi, Enrico Forti, Elena Rossi, Frank Cavallari, Pier Paolo Ascari, Laura Gasparini, The Fototeca of the Panizzi Library, Fotografia Europea, Comune di Reggio Emilia - Assessorato alla Cultura e Università, Ilaria Campioli, Francesca Monti, Filippo Franceschini, Elisabetta Farioli, Franco Guerzoni, Franco Vaccari, Giulio Bizzarri, Giorgio De Mitri.