Zurich, an apartment building designed in the mid-1930s by Marcel Breuer and the Roth brothers. The period elements—faucets, sculptural radiators, terrazzo flooring on the terrace—contrast with contemporary background music: the original soundtrack to the film Annette by Leos Carax, composed by the Mael brothers of the group Sparks. Beda Achermann has François Halard over for dinner. On the menu: their latest book.

APERITIVO

toasting to a special understanding between collectors

A glass of Etna rosso in hand, the photographer admires the artistic director’s latest acquisitions of cherished antique plates from Spain, Italy, and Portugal. Then the two of them flip through a Richard Prince portfolio purchased after an exhibition in Bregenz. They rave about the print quality, which is “almost like painting.”

FRANÇOIS HALARD Beda and I have an understanding as collectors, especially of photographs. It isn’t just the fact of having worked on projects together that brings us together. We share a certain spirit. He’s more into fashion, and for me, it’s art. But we both have this love of the beautiful—furniture, books....

BEDA ACHERMAN François knows the aesthetic value of photos.

FH: I love living surrounded by photos that stimulate me every day. Images I have never let go.

BA: It’s like a diary. We live in the things we love.

FH: It’s essential.

BA: We work together so well and so often because we have the same...

FH: …purpose.

BA: We always have a personal story with the photos we acquire.

FH: Plus, our connection goes beyond just work. We also go to the flea market together...

BA: We’re very similar in the way we live with photos. And with artworks in general. Because I also surround myself with vases and plates, with books and chairs...

FH: …And I collect paintings, drawings, and objects…

PRIMO PIATTO

delighting in new visions

They move to the dining room, which has a very masculine appearance. The wooden table, both rustic and chic, holds a plaster cast by Giacometti discovered at Paul Bert Serpette, the largest antiques market in the world, located north of Paris. Framed and leaning against the walls are platinum palladium prints by Beda’s friend Irving Penn. Beda apologizes for the harsh light—”but the lamp is beautiful”— and serves a puntarelle salad with anchovies and mustard.

FH: From our understanding, there grew a collaboration, a friendship, and a series of books. It’s all connected...

FRANÇOIS HALARDFRANÇOIS HALARD FRANÇOIS HALARDFRANÇOIS HALARDBA: …travels, food—everything! What’s important isn’t to always like the same thing. It’s to have the same artistic sensibility. Our original collaboration was a still life shoot for Männer Vogue [of which Achermann was artistic director from 1984 to 1989]. We had used a photo of cowboys in the background, an image by Kurt Markus. At the time, I didn’t know him yet—he later became a friend.

FH: After this first encounter, we saw that we had aesthetic friends in common. Beda loved Günther Förg, the Bavarian painter and photographer who died in 2013.

BA: I had worked with him several times when I was at Männer Vogue. He was a very special artist, who created with both a brush and a camera.

Twenty years ago already, François and I collaborated on several artistic subjects such as Brancusi, the house of Carlo Mollino, which is very chic today, but at that time…

FH: …on Man Ray, too, Hans Bellmer, the Maison de Verre, and other things.

BA: These are important reference points for us. We always found stories from the past to treat in the style of the present. Stories we dream of today...

FH: …about artists who were less relevant at the time, less recognized than they are today. This was before the internet, before Google. You had to do research—it took a lot of time.

BA: But unlike most things today, we were really inside it.

FH: At that time, if you were interested in Man Ray, if you didn’t collect his books or auction catalogues or the publications he worked on (like the Surrealist magazine Minotaure), you couldn’t have access to his work. I lived in New York for almost thirty years. Three or four nights a week, I’d stop by the Strand bookstore, which stayed open late, to find old books. If I hadn’t been autistic in my childhood, locking myself away in my parents’ library looking at books and newspapers, I wouldn’t have had the same intensity of looking at images. I never would have evolved in the same way. It saved me.

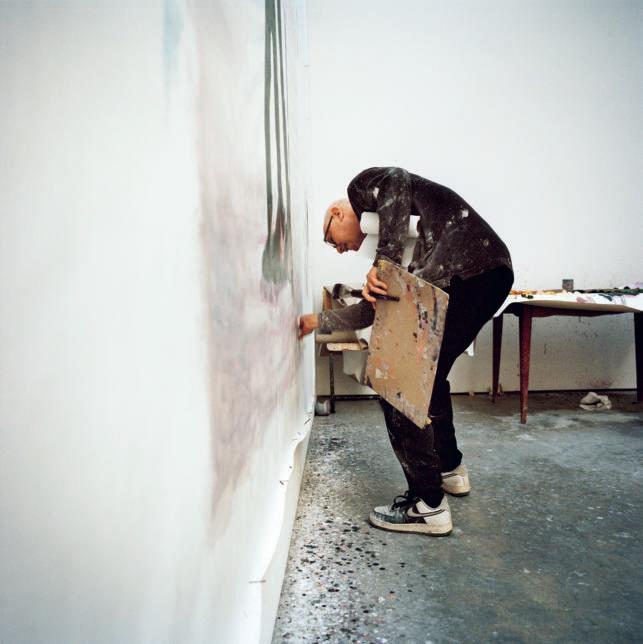

BA: New Vision is along the same lines as the two books we already published with Rizzoli

FH: This third book continues even further into my artistic vision. The most important thing for me is to be in the emotion when shooting. There is never strong photography without emotion. Without light, there is no strength. The camera must be guided by beauty. The admiration I have for Antonioni or Twombly has never inhibited me, on the contrary: it stimulates me. It’s an incredible challenge. For instance, I had wanted to photograph Luc Tuymans for a long time. Almost twenty years ago, I had cut out photos of his studio. I said to myself: one day I’ll be there! Those twenty years of waiting were condensed into an hour of shooting.

FRANÇOIS HALARDFRANÇOIS HALARDBA: These photos exude the same silence, the same interiority as his paintings...

FH: When I photograph an artist in the studio, I think of the photographs that Ugo Mulas took of Lucio Fontana in his studio. I collect views of artists’ houses —by Brassaï, by Man Ray, of the studios of Picasso, Brancusi. Those are my references.

BA: You often worked with a sense of urgency.

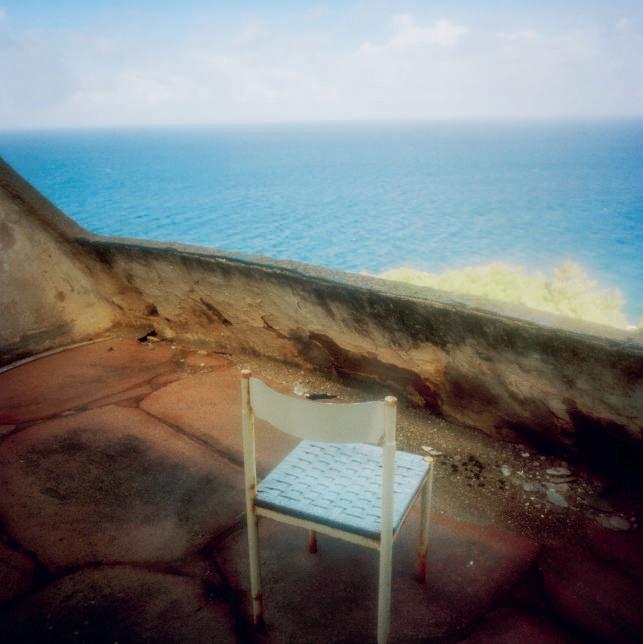

FH: With a sense of urgency, I get to the essen-tial. Like the photographs of La Cupola in Sardinia.

BA: That’s also a very personal story.

FH: Michelangelo Antonioni is one of my favorite filmmakers. In the second half of the 1960s, out of love for Monica Vitti, he asked the architect Dante Bini to design a “spatial” villa, called La Cupola, in Costa Paradiso, on the northern coast of Sardinia. But the couple split up before the villa was completed, and Antonioni ultimately moved into it with Enrica Fico during the next decade. When she became ill, the extraordinary building was pretty much abandoned. The only period photos are Polaroids by Andrei Tarkovsky who visited there! Everything was still in its original state, the furniture and the rat droppings. I dreamed about this place so much that I even imagined buying it with friends. In the same way, the house where I live in Arles attracted me because it evokes Cy Twombly’s house in Bassano in Teverina. In the 1980s, I had endlessly

contemplated the photos that Deborah de Turbeville had taken of it.

BA: With Lindbergh’s studio in Paris, it was a different situation. You and I were among his close friends.

FH: This series is a personal homage that has almost no panoramic views. I tried to find revealing angles, close-ups, significant details. Like for the series on Isamu Noguchi’s garden and house.

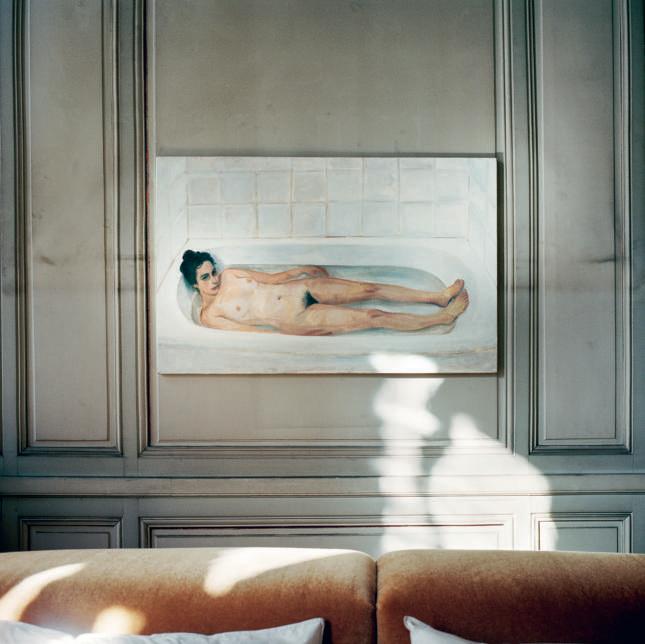

BA: You also have a personal and quirky relationship with the Villa Médicis.

FH: I was able to stay in the room adjoining the little Moorish-style room where Balthus, who was named director of the French Academy in Rome in 1961, posed his young Japanese wife Setsuko. The painting, like the room, is called The Turkish Room; it’s one of my favorite artworks. By photographing the interiors and gardens of the Villa Médicis, I tried to rediscover a kind of magic corresponding to the magic of my memory of this painting.

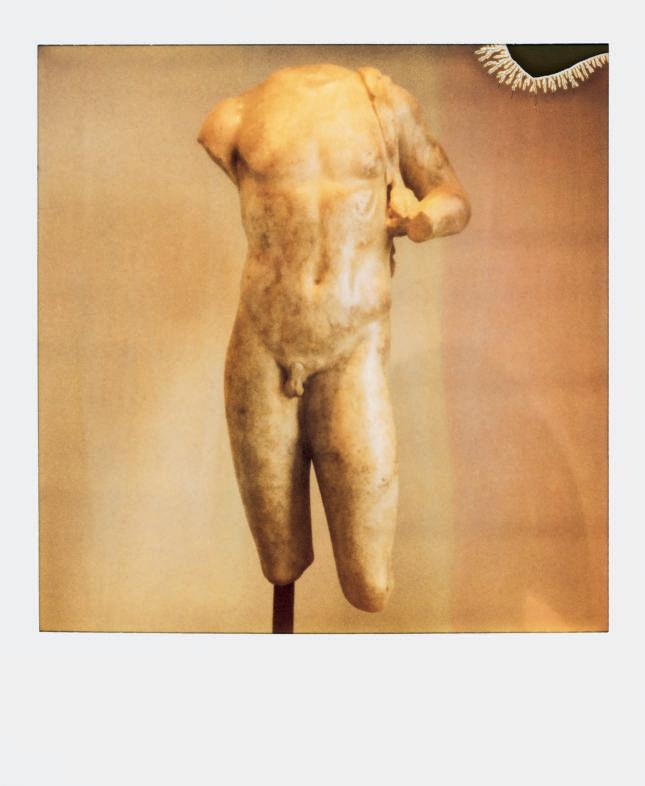

BA: The “new vision” of this book is expressed in two “experimental” series: one of Willem Dafoe (and Julian Schnabel) about Van Gogh and one on ancient sculptures at the very end of the volume.

FH: A few years ago, I took four photos of paintings by Julian showing Dafoe as Van Gogh.

BA: So I suggested that you take new shots based on the film that the two of them made about Van Gogh,

HALARDFRANÇOIS HALARDAt Eternity’s Gate. And, by doing this, to build a bridge toward art.

FH: Ever since I studied film at the Arts Déco [L’Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs] at age twenty, I’ve always loved images from movies. It was my habit to look at every shot of a movie, image by image. Back then, there were no computers, so I did this on a Trinitron TV set. Then I took Polaroids of a computer screen showing images of Dafoe in At Eternity’s Gate. This created a different dimension. It wasn’t like a freeze-frame, but more like a “real” photo. That created a link with this film shoot, which I attended at the end of 2017 in Arles. It was like period photos—but taken with years in between!

BA: The “new vision” is also a new freedom and a new thirst for experimentation. You discovered the chemical accidents that can happen to Polaroids a while ago....

FH: At first, I appropriated drips and spots, which weren’t planned out in advance, when I liked them, like in the series of Polaroids of Baalbek. Here, in the last chapter of the book, I recreated them with a different technique. In fact, these enlargements of my Polaroids, like those of ancient statues, include accidents—this time, very controlled ones—created by hand, with diluted beeswax, after countless attempts.

BA: The photo as a starting point for something else, something painterly…

FH: …I’ve been thinking about this for thirty or forty years. But I only dared to

get started on it now. Maturity makes you bold. It’s very new for me to stay in the studio for weeks doing experiments.

BA: What’s astonishing is that all these new works are like a mirror, a reflection of the house in Arles and of what François is. It’s like a Rorschach test!

SECONDO PIATTO

filling one’s belly with complementarity

Beda serves orecchiette alle cime di rapa covered with a lemon-anchovy sauce and topped with freshly grated zest.

FH: We planned this book a long time in advance. For a year or two, we talked a lot about what directions to go in. At every shoot, I thought about the book. What’s funny is that we didn’t take a single shot together. I experimented all on my own, but always thinking about our conversations, our project

BA: The intention of the third book was to go even further into the artistic vision.

FH: My vision evolves, but in the studio, it goes off in every direction. Beda helped me to find a form. It’s like a painter and their dealer, a musician and their impresario. It reframes things.

I’m not the best editor of my own photos. I need an expert point of view from outside that I trust completely. If Beda thinks that associating two images that I wouldn’t have dared to put together will make sense, I follow him. He knows how to highlight emotion through a layout. How to create something different by the arran-

FRANÇOIS FRANÇOIS HALARDFRANÇOIS HALARDgement of the images: strength, questioning. An artistic director may not be a good photographer, and a photographer may not be a good artistic director.

BA: The major difference between François and me is that I see and think with other people’s eyes. I’ve worked with great photographers like Lindbergh, Newton, or Penn and with young people who are twenty-five. When I walk in the street in Paris, I see a Jack Pierson or a François Halard. I couldn’t be an artistic photographer— I don’t have my own vision. However, I know the styles of the different photographers I work with like the back of my hand. I know exactly what François will do when he enters a room.

FH: With my new work, you may be surprised!

BA: He enters a room, and right away he has the “tripod” reflex. He holds the camera at a normal height, blindly—I’m sure it’s always at the same height, down to the centimeter!

FH: One day, I wanted someone to tell me about a room, the dimensions, the furniture, the location of the windows. I went to take a photo without looking: it was basically the same thing! I had planned where I would stand, the height of the shot, the lens....

BA: We both talk a lot about photography, about what the next photo will be, about other people’s photos....

FH: A good artistic director is someone...

BA: Watch what you’re going to say!

FH: ...Someone who takes you further, who makes you freer. Since he knows your work intimately, he knows just how far you can go, and he pushes you to leave your comfort zone, to enrich your vocabulary, to become stronger, truer, more incisive.... He’s like a midwife.

BA: Finding new paths, pushing you to go further...without abandoning your style....

FH: There is also the fact that Beda and I deeply love books. We think they’re always the best way to communicate your soul, your image, and the story you want to tell.

BA: It’s important to see photos that are not small-scale, like on phone screens. System Magazine, for example, has special issues that are very large. The editor Gerhard Steidl likes to say: “Everything in print should be big— the rest is for the web.” It’s important to make big books with beautiful print quality.

FH: Beda and I also decided to make long stories. Subjects with 14, 16, 20, 28 pages! To make people get inside them, live with them. Not just switch to the next thing.

BA: The layout is radical, rough. It’s not a pretty magazine, a pleasant coffee-table book. We take things to the extreme to clearly show the difference between a documentary photo and an artistic photo.

FH: I want to provoke emotion. That’s the only thing I’m interested in.

BA: It goes well with red wine, food, conviviality—life, basically!