AFoodie’s Paradise

We knowwhere toget a bite—whetherit’s fresh, farm-to-tablefoodsservedatlocally-owned restaurantsor a closeencounterwith a sharkat WondersofWildlifeNationalMuseum & Aquarium. We loveourcityandknowthebestplaces toeat,drinkandplay.

know where to get a bite—whether it’s

PRE-ROLLS CARTRIDGES

“Justright”momentsdon’thappenbyaccident.TealCannabis existstomakecannabisfitforyou.DiscoverhowTealcan helpyougetdialedinwith a choiceofproductsallexpertly craftedwithprecision.

DISPOSABLES CONCENTRATES

tealcannabis.co/locate

Thekingofragtimecelebrateshisqueen The king of ragtime celebrates his queen

By SCOTTJOPLIN

By SCOTTJOPLIN

Re-imaginedwith a newprologueandepilogue

Re-imagined with new prologue and epilogue by DAMIENSNEED & KARENCHILTON

Inspired

SUMMER 2023

VOLUME 13 / ISSUE 5

EDITORIAL

EDITOR IN CHIEF

Emily Adams, emily.adams@feastmagazine.com

MANAGING EDITOR Mary Andino, mandino@feastmagazine.com

DIGITAL EDITOR Shannon Weber, sweber@feastmagazine.com

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Charlo e Renner, crenner@feastmagazine.com

ASSISTANT EDITOR Emily Standlee, estandlee@feastmagazine.com

PROOFREADER & CONTRIBUTING WRITER

Alecia Humphreys

SALES

VICE PRESIDENT OF SALES

Kevin Hart, khart@stlpostmedia.com

MEDIA STRATEGIST

Erin Wood, ewood@feastmagazine.com

ART ART DIRECTOR Dawn Deane, dawn.deane@feastmagazine.com

ASSISTANT ART DIRECTOR Laura DeVlieger

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Christina Kling-Garre , Jennifer Silverberg

CONTRIBUTING ILLUSTRATOR Jillian Kaye

CONTACT US

Feast Magazine, 901 N. 10th St., St. Louis, MO 63101 | 314.475.1260 | feastmagazine.com

EDITOR’S letter

Get ready, St. Louis. The next generation of Feast is coming –and we want you along for the ride.

Beginning this month, we are excited to announce that Feast will be taking our local food coverage to new heights with a digital-forward approach designed to meet our readers where they are. With a reinvigorated investment online, our team will be providing more innovative, engaging and timely journalism on feastmagazine.com than ever before.

Our newly revamped suite of newsle ers will deliver breaking news, top food trends and weekly events straight to your inbox. Our social media platforms will move with the pulse of the metro area food community with regular on-the-go and multimedia content, and our website will act as a hub for specialty guides to food and drink destinations in and around St. Louis. Sign up at feastmagazine.com/newsle ers and follow @feastmag on social media to be sure you won’t miss a thing!

This digital expansion will be complemented by a high-quality, quarterly print publication that curates the hottest crazes and personalities in local food culture each season. Our fall edition, to be released in the Sunday St. Louis Post-Dispatch on September 3, will include holiday entertaining tips, thought-provoking features, recommendations for the best eats and treats of the moment and much more. Visit STLtoday. com/subscribe to get the quarterly delivered to your home in the Sunday paper, or buy your copy in

the September 3 edition of the PostDispatch at the retail locations listed at STLtoday.com/newsstands.

As we look ahead to this next era, we thought it only fitting to dedicate this, the last monthly edition of the magazine, to the culinary history that built the city we love. On each page, you’ll discover fascinating nuggets of information about the foundation of St. Louis’ food community, from the city’s original Chinatown (p. 30) to the region’s Indigenous ingredients still being used today (p.20) to the roots of food deserts across the area (p. 25) to the infamous dressing that’s getting new life (p. 19). Meet the young leaders taking on their family’s legacy on p. 12, and check out the famous cookbooks you might not have known were written by St. Louis women on p. 11.

As we revere and appreciate St. Louis’ deeply rich history, a big thank you to you for being part of Feast’s bright future.

Cheers,

Emily Adams emily.adams@feastmagazine.com

1770s: Settlers to Missouri from Pennsylvania bring the first seed potatoes to the state.

1901: William Straub opens his first grocery store, Straub’s. The company has four locations in the St. Louis area today.

1901: The Piccadilly at Manhattan in Ellendale opens. The restaurant has been owned by the same family since the 1920s.

1901: William Straub opens his first grocery store, Straub’s. The company has four locations in the St. Louis area today.

1901: The Piccadilly at Manhattan in Ellendale opens. The restaurant has been owned by the same family since the 1920s.

1890s: Italian immigrants begin populating a growing blue-collar neighborhood en masse to seek jobs at nearby plants. This neighborhood is later established as The Hill, named for its proximity to the highest point in St. Louis

1840s: Soulard Market opens. Julia Soulard, widow of Antoine Soulard (the Surveyor of Upper Louisiana and a major early landholder in the city), donated two blocks to the city in 1838 on the condition that the site be used as a public market in perpetuity.

1852: Anheuser-Busch Brewery is founded in St. Louis.

1903: Dr. Ambrose Straub of St. Louis patents a machine to make peanut bu er.

1854: Dierbergs opens as a general merchant exchange on Olive Street Road. The original operation sold kerosene, flour, sugar, boots, shoes and more.

1917: The Bevo Mill Restaurant building opens with its iconic windmill. It was commissioned by August Busch Sr. to replicate European beer gardens.

1918: Charles Gioia opens the first Gioia’s Deli on The Hill.

1918: Charles Gioia opens the first Gioia’s Deli on The Hill.

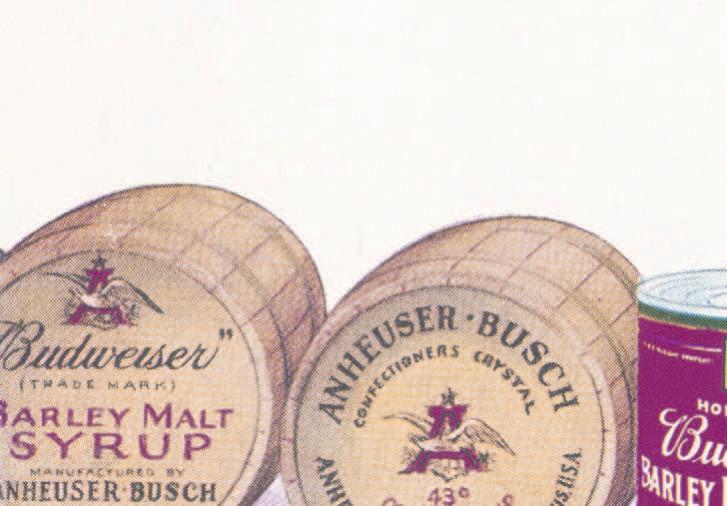

A Brewery Without Booze?

How Anheuser-Busch pivoted to survive Prohibition

WRITTEN BY EMILY STANDLEE PHOTOS COURTESY OF ANHEUSER-BUSCH

WRITTEN BY EMILY STANDLEE PHOTOS COURTESY OF ANHEUSER-BUSCH

Support for Prohibition had been building for decades before the law went into effect in 1920. The 18th Amendment forced many businesses, including St. Louis mainstay Anheuser-Busch, to pivot quickly and creatively to stay open.

“I think it’s important to note that at the height of the pre-Prohibition era, there were about 1,500 breweries in the United States,” says Tracy Lauer, manager and curator of collections at Anheuser-Busch. “When Prohibition was finally repealed, only about half of them [had] survived.”

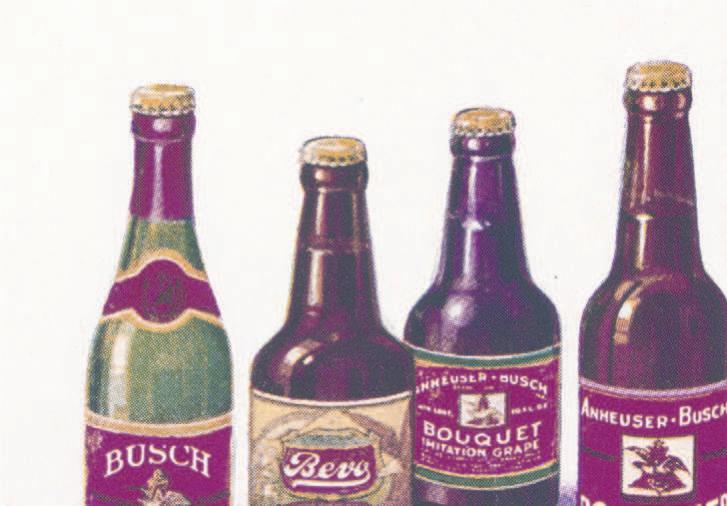

Although A-B lobbied against Prohibition, the

business’s leaders drew the line at breaking the law; instead, they experimented with a nonalcoholic beer called Bevo. This endeavor was successful at launch, and it provided funding to build an eponymous new bo ling facility in 1918 that’s still in good condition today. The brewery also created a nonalcoholic version of its bestselling Budweiser, but the product didn’t take off. Meanwhile, bootleggers all over the country were manufacturing liquor, which was easier to smuggle and didn’t have much of a smell when produced.

“When you’re [near the A-B campus], you can smell the hops and the barley,” Lauer says. “It’s not something you can easily make and

not have people smell. If I were a Prohibition agent, the first thing I would do is look around for illegal activity; I [would] use my nose.”

During this same era, to meet an increased demand for mixers, A-B began making ginger ale, which sold well. It also made grape- and chocolate-flavored sodas. “We found that consumers were looking for things they could mix; ultimately, the cocktail was born during Prohibition for that reason,” Lauer explains. Although the formal amendment wasn’t repealed until Dec. 5, 1933, beer became legal on April 7 of that year, giving A-B a leg up on liquor producers, who had to wait to restart their sales. At midnight on April 7, a crowd of 25,000

lined up in Soulard outside the Bevo bo ling facility, anxious to legally purchase beer again.

The brewery had one more surprise up its sleeve for the waiting group – a wagon hitched to six Clydesdales. A gi to the head of the company from his two sons, the horse-and-wagon combo was a metaphor of sorts and a genius marketing scheme meant to help consumers recall the “be er days” before Prohibition.

“It was so well-received, they used the Clydesdales to deliver the first case of postProhibition Budweiser to the President of the United States,” Lauer says.

1919: Lemp Brewery closes due to Prohibition.

1925: Al’s Restaurant opens as a tavern selling sandwiches to workingclass customers. Subsequent generations have since turned it into a fine dining establishment.

Prohibition FAST FACTS

During Prohibition, the tavern that now houses Square One Brewery & Distillery in Lafayette Park kept the lights on by operating as a soda fountain shop. It was owned by A-B at the time.

Lemp Brewery produced a “near beer” called Cerva, but it was unpopular, forcing the brewery to close in 1919.

According to author Suzanne Corbett, Hill Winery in Hermann, Missouri, survived by using its underground cellars to grow mushrooms.

Historic Cookbooks Written by St. Louis Women

Missouri History Museum assistant librarian Magdalene

Linck shares her top three female-authored cookbooks in the museum’s collection.

WRITTEN BY CHARLOTTE RENNER | PHOTOS SUPPLIED

WRITTEN BY CHARLOTTE RENNER | PHOTOS SUPPLIED

When COVID-19 hit and Missouri History Museum employees were sent home, assistant librarian Magdalene Linck had a new opportunity to pursue her intellectual interests. She stocked up on cookbooks from the Missouri Historical Society’s library and threw herself into food research. “Everyone is so familiar with ‘Joy of Cooking’ [by Irma S. Rombauer] and how big and important that cookbook is, but there’s so many other great cookbooks that were written by women from St. Louis,” Linck says. She even tried her hand at remaking some of the historic recipes she found, like “transparent pudding,” which Linck says turned out similarly to chess pie. “You’re literally able to taste what the past tasted like, to some extent,” she says. You can explore Linck’s three recommendations by visiting the Missouri Historical Society Library and Research Center on Skinker Boulevard during its open hours.

“St. Mary’s Guild Cook Book: A Collection of Tested Recipes”

compiled by St. Mary’s Guild of St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, 1915

“There’s a recipe for Russian dressing in there, and it’s credited to Mrs. Vincent Price, who’s Vincent Price’s mother, the actor; they were a member of that church. The other thing I really like about church cookbooks, aside from the fact that most of the recipes are submitted by female congregants, is that oftentimes they’re some of the only ways that you get parish histories. [Church] cookbooks are the only places that have information about certain immigrant groups, which I don’t think people think about at all.”

“Household Memorandum Book”

by Julia Clark, 1820

“It was kept by and written by Julia Clark, who was the wife of William Clark of Lewis and Clark fame. It’s a pretty interesting snapshot of what people were eating in St. Louis at that particular point in time – right as Missouri was gaining statehood. While it is obviously representative of an upper class family, it still is a really interesting cookbook, and there’s about 50 recipes in it.”

“Delicious Dishes”

by the Women’s Traffic Club of Metropolitan St. Louis, 1965

“Their goal was to educate women in the field of traffic, industrial transportation and transportation in general. I didn’t realize that such a thing existed, but I’m glad it does. I think it still is an operation as well. But what’s really fun about this one is that it has all sorts of different important female politicians and political figures at the time. So like Lenore K. Sullivan, who was a representative; the First Lady of Missouri is mentioned in there; Senator John Danforth’s wife Sally is mentioned in there.”

1931: The St. Louis Globe-Democrat estimates that St. Louis is home to more than 1,000 speakeasies.

1932: Authorities raid Appleton Brewery in Cape Girardeau and seize 6,000 gallons of beer. It is suspected of supplying St. Louis speakeasies with alcohol.

Photograph of the M-K-T Bowling Team of the St. Louis Women's Traffic Club League. Bille Graulich (top left) is featured in the Delicious Dishes cookbook. (Katy Employe's Magazine, August 1952) Portrait of Julia ClarkMetamorphosisTHE

SOUTH GRAND RESTAURATEURS LOOK TOWARD THE FUTURE

WRITTEN BY SHANNON WEBER | PHOTOS BY JENNIFER SILVERBERG

WRITTEN BY SHANNON WEBER | PHOTOS BY JENNIFER SILVERBERG

In the tight-knit community of South Grand’s business district, two legends in the restaurant industry are building from their past to forge a path forward, albeit in different ways.One is solidly grounded in the foundation his parents built and carefully expands and evolves their collection of establishments. The other is honoring her past by taking what she’s learned and creating something completely new to the St. Louis culinary landscape.

Cafe Natasha was born from necessity; a recession and a layoff led a husband and wife with a young daughter to open a café, despite having no prior restaurant experience. Their venture began in 1983 as a downtown St. Louis cafeteria and eventually became a Persian restaurant called “Kabob International” in the Delmar Loop a decade later. By 2001, Behshid and Hamishe Bahrami landed in their forever home of South Grand with Cafe Natasha, named for their only child and perhaps the catalyst for the entire endeavor. Natasha Bahrami recently transformed her parents’ legendary restaurant into something wholly her own, and to much acclaim: Her restaurant Salve Osteria has garnered multiple accolades since opening in 2022, and The Gin Room, adjacent to Salve, was named a semifinalist for a

of FAMILY LEGACY

2023 James Beard Foundation Award for Outstanding Bar. For Bahrami, one of the most notable changes over time has been the increased closeness of the restaurant community. “We have a much tighter-knit community in the last 10 years,” Bahrami says. “When we started, it really felt like every restaurant for themselves, and it’s amazing to see how the community has come together.” Decades of time in the grueling restaurant world has demonstrated the importance of work-life balance to Bahrami. “This industry takes an emotional and mental toll on you, despite how amazing it is,” Bahrami says. “Making sure we take care of ourselves as we take care of our guests is important.” This ethos, one she shares with her life and business partner Michael Fricker, is part of what’s driven their success as they navigate multiple spaces on South Grand, including Fricker’s Grand Spirits Bo le Company a few doors down, and the launch of his upcoming speakeasy, New Society, in the basement of Grand Spirits.

Less than 800 feet away sits King and I, which began in 1983 when Suchin Prapaisilp opened the first-ever Thai restaurant in St. Louis. By then, Prapaisilp had been in the industry for a decade, bringing international ingredients to the city with Global Foods Market, one of the first of its kind in the area. With King and I, Prapaisilp firmly planted his flag on South Grand and introduced the region to his family’s beloved cuisine.

“The breadth and diversity of international cuisine here in St. Louis would not be possible if not for him being one of the first international grocers here,” Shayn Prapaisilp, COO of STJ Group Holdings and son of the elder Prapaisilp,

Salve Osteria 1934: Lombardo’s Tra oria opens in North County. Legend says the restaurant invented the toasted ravioli. 1939: Anna Schnuck establishes a confectionary in North St. Louis. It is the first of what will eventually become the local Schnucks Markets chain.1964: The first Imo’s Pizza opens in The Hill. The business eventually expanded to have more than 100 locations in Missouri, Illinois and Kansas.

1970s: St. Louis company Old Vienna introduces Red Hot Riplets. The product has since grown to account for 80 percent of the company’s sales.

Natasha Bahrami and Michael Fricker at The Gin Room

Natasha Bahrami and Michael Fricker at The Gin Room

1988: In response to the U.S. AIDS epidemic, a group of individuals founds grassroots nonprofit Food Outreach. They provide meals to area residents living with HIV/AIDS.

1990s: Immigration of Bosnians to St. Louis begins as a result of the Bosnian War. The city has since grown to have the largest Bosnian population outside of Europe, who created a robust Bosnian restaurant scene.

IT’S BEEN AMAZING TO SEE WHAT SOUTH GRAND HAS BECOME OVER THE LAST 30 YEARS.‒ Suchin Prapaisilp pictured with Shayn Prapaisilp

says. Shayn oversees operations on his family’s portfolio of restaurants and retail stores, including United Provisions and Chao Baan, among others. Shayn, who grew up in the industry, has seen a shift over time in how people view Thai food. “I think you’re seeing a lot more interest from a wider group of people who are interested in Thai and international cuisines,” he says. “Thai food in particular is now a regular part of people’s weekly dining plans, where before it was looked at as something only for special occasions.”

For all four individuals, it’s about the layers of work that go into their craft. It’s about sourcing the best ingredients, fostering relationships within the community and actively listening to feedback from their guests to optimize the experience at all of their establishments. And at the forefront, it’s about education. For Fricker and Bahrami –the self-proclaimed “Gin Girl” who has made it her mission to help others appreciate the spirit – it’s essential. “If we aren’t trying to grow the environment around us with the knowledge we have, then what are we really doing?” Bahrami says. “It’s important to us to continue to learn and share that joy that comes with knowledge. We love the people we work with and are firm believers that knowledge is power.” For the Prapaisilps, education has always been at the core of what they do. “We try to make international foods a part of people’s everyday cooking: It’s just an exploration of other people’s ‘normal,’” Shayn says, adding that customers continually come up and ask what a product is and how to use it, and the father-son team never wants that to change.

What they do see changing is the dining industry itself, and they’re embracing it. For Suchin, it’s meant shifting South Grand mainstay King and I to Richmond Heights, a central location designed to retain both their current customers

and welcome new guests alike. “It’s been amazing to see what South Grand has become over the last 30 years,” Suchin says. “We hope that we’ve been able to contribute to the vibrant community that the neighborhood has become today.” For Bahrami and Fricker, the neighborhood continues to be their home, both personally and professionally. “South Grand and the Tower Grove area is an absolutely incredible community; the way it embraces all peoples is everything I want out of where I live and work,” Fricker says. What’s on the horizon is exciting for the duo. “We are in an integral transition from legacy restaurants that have been here 25-plus years to the fresh new energy that is hitting the district,” Bahrami adds. “It’s amazing to be directly part of that step forward.”

Now, from different vantage points in the city, all are eager for what’s to come, and even more eager to be a part of it. That new energy Bahrami alludes to is evident in things they’re all excited about, from large-scale food hall concepts like City Foundry STL,; to bar concepts solely focused on creativity and craft of mixology; to the proliferation of younger and more diverse chefs and restaurateurs throughout the metro area. No matter what form things take, St. Louis as a whole is ready for the next iteration of the restaurant industry.

Chao Baan

Chao Baan

1994: The first Kaldi’s Coffee opens in Demun. It later opened multiple locations across the city and in Atlanta.

1999: St. Louis Community College launches its culinary arts program. It becomes a premier program and has since trained many well-known chefs.

Chao Baan

Chao Baan

1994: The first Kaldi’s Coffee opens in Demun. It later opened multiple locations across the city and in Atlanta.

1999: St. Louis Community College launches its culinary arts program. It becomes a premier program and has since trained many well-known chefs.

The Amighetti’sSpecial

AMIGHETTI’S MAY HAVE BEGUN AS A SMALL BAKERY IN 1916, BUT THE RESTAURANT WAS LATER REVOLUTIONIZED – ALL THANKS TO ONE SPECIAL SANDWICH.

“To put it simply, Marge Amighetti's ambition inspired the sandwich,” Amighetti’s owner Anthony Favazza says. “In 1969, Mrs. Amighetti saw the potential for her husband’s business to expand to more than just a bakery. She told Junior that his bread was wonderful and insisted [they were] going to do more than just sell it over the counter. [So, they] began work to create a one-of-a-kind sauce.”

According to Favazza, Amighetti spent eight months perfecting this unique condiment.

“She offered the neighborhood kids tastes of her concoctions, and she knew she had a winning spice mixture when the kids kept coming back for more,” Favazza says. “Once the sauce was right, Mrs. A set out to pick the best combination of meats and toppings.”

She ultimately chose ham, roast beef, salami, Provel cheese, lettuce, tomato, pickle, onion and pepperoncini, all stacked high on Amighetti Italian bread.

“The sandwich is still made the same way as it was in 1969,” Favazza says. “Mrs. Amighetti insists that the order of the ingredients is crucial to its taste, so we make every Amighetti's Special exactly the way she did.

“There are countless Amighetti's Special dupes,” Favazza continues. “Anyone can source high-quality ingredients like we do if they really want to, but no one can replicate our signature special sauce. This phenomenon inspired the slogan, ‘Often Imitated, Never Duplicated’ that Mrs. Amighetti came up with after being frustrated by every corner sandwich shop imitating, albeit poorly, her sandwich.”

Amighetti’s, multiple locations, amighettis.com

MRS. AMIGHETTI INSISTS THAT THE ORDER OF THE INGREDIENTS IS CRUCIAL TO ITS TASTE, SO WE MAKE EVERY AMIGHETTI'S SPECIAL EXACTLY THE WAY SHE DID.

– Anthony FavazzaMarge Amighetti

Casa de Tres Reyes

Casa de Tres Reyes opened in the beginning of November in Des Peres. If you know even a little Spanish, you might have guessed the restaurant’s link to a well-known St. Louis spot: This is the new venture from the team behind Three Kings Public House. Tacos are among the featured dishes at Casa de Tres Reyes, but the appetizers also offer some gems.

Where Casa de Tres Reyes, 1181 Colonnade Center, Des Peres, Missouri

More info 314-394-0214; casadetresreyes.com

West Bank Street Eats

At a reader’s suggestion, we visited West Bank Street Eats, a new O’Fallon, Illinois, storefront where Milad Hamed and his family are focused on beef and chicken shawarma. Ian Froeb declares it the best shawarma in the St. Louis area.

Katsuya

At Katsuya in the Delmar Loop, you will find the rare intersection of convenience, efficiency and elegance. The restaurant serves its signature dish, katsu, as a bento box.

PRESENTED BY

HOOKUP YOURDIETWITHMORE FISH

Veggieand Rice Bowlswith Grilled Tuna

FORBOWL

2 scallions

2 sweetpotatoes

16oz broccoli florets

1 lime

2 cups jasminerice

4 Tbsp mayonnaise

2tsp rooster sauce (totaste)

Salt and pepper (totaste)

SALMON

Salmonis topsforhearthealth.

Ithasanabundance ofomega-3 fatty acids,which candecrease theriskofbloodclots, heart attacks andstrokes, as wellas vitamin D andprotein,both terrific forstrongbones.Salmon has a pronouncedflavorthat canholditsownagainstpiquant seasonings, suchaschilepowder and garlic.Pairitwith a mellow sidedish,likeroasted vegetables orlemon pasta.

SNAPPER

Many mild-tasting whitefish, suchastilapia,aretoodelicateto grill,butthat’s notthe case with snapper. Itisfirm yet retains moisturewhen cooked,andit hasanalmost sweet taste.Plus, it’s often a more sustainable choice thantilapia look for a labelindicatingthatit’sU.S wild-caughtsnapper Thefish ishighinprotein,low in fatand sodiumandan excellentchoice forhearthealth.

SWORDFISH

Servingup a thickcutof swordfishmightbethebest way to win over avowed carnivores. Swordfishmanages to beboth mildandmeaty, anditholdsup wellonthegrill.It’saparticularly greatchoicefor kebabs:Thread chunks of swordfishonto skewers alongside colorfulbell peppers and topwith asqueeze oflemon.It’s highin selenium, anantioxidantthat contributes mightilytocellhealth. Beaware that swordfish containsmore mercury thanmany otherkinds of seafood, so kidsandpregnant womenshould avoidit.

YOURHEALTHTIPS

Fish,especiallyfattyfish,hasfamously beencalleda“hearthealthyfood,”andthe American HeartAssociationrecommends eating2servingsoffishperweek.Fattyfish suchassalmon,herringandsardinearehigh inomega-3fattyacidsthatreduceriskofheart disease andstroke and alsomaintain brain health.

Butthepositivesdon’tstopthere.“Instead ofjusteatingredmeatthatishighin unhealthysaturatedfat,eatingfishhasmany healthbenefits, includinghealthyheart andbrain,”saysYikyungPark,doctorof science,aWashingtonUniversitynutritional epidemiologistatSitemanCancer Center.

“Fishisalsohighinproteinandagoodsource ofvitaminsandminerals,whichcanhelp preventbecomingfrail.”

Evenwithallofthesebenefits,it’sestimated thatonlyabout20%ofAmericansconsume therecommendedtwoservingsof4ounces offishperweek(roughlythesizeofacanof tuna).Parksayswhiletherearesomerisks frommercuryandotherenvironmental contaminants,thatamountissafefor everyone—includingpregnantwomenand children.Onewaytogetclosertothatgoal istoexperimentwithsomelighter-tasting fish,suchascodortilapia.Grilling,baking orsteaming—ratherthanfrying—arethe healthiestpreparations.Parkalsosuggests incorporatingfishintomixeddishes,suchas curries,stewsandcasseroles,wheretheflavor ismorelikelytoblendinseamlessly.

Overfishingremainsaproblem,andtheway thatimportedseafoodisharvestedcanhave

TUNA

Tunaalready has a lot going forit.Low in fatbuthighin vitaminsandminerals, tunais availableasbothhigh-endcuts andinaffordabletins. While it’s hardto beat cannedtuna for convenience, considergrilling ahi(yellowfin)tunasteaks. Get thegrillashotaspossible, season tunawith saltandpepper,sear about60 secondspersideand dinner’sready!(Justbesure that theinternal temphits 115°F.)

Olive oil

FORTUNA

2 tuna fillets

Soysauce

Garlic

Ginger

Sesameoil

PREPARATION

Preheat oven to 425°F.Heat grill to highheat(atleast 500°F). Combine soysauce, garlicandgingerinshallow dish. Pattunasteaks dry with paper towel. Addtunasteaks and setaside to marinate. Washanddry allproduce.Cut broccoliflorets into bite-size pieces. Cut sweetpotatoesin halfandthenslice into ¼-inch thickcrescents. Slicescallions, separating whitesfrom tops. Quarterlime. Toss broccoliand sweetpotato with a drizzleof olive oiland seasonwith salt andpepper Place on baking sheetand bakefor20minutes Add a drizzleofolive oil toa smallpotalongwith scallion whites.Cookuntil softened, about 1 minute. Addrice and 2 cupswater to potandbring toa boil. Reduceto low simmerand cover.Cookabout18minutes.

serious environmentalrepercussions.Opt forwildcaughtfishorfishthathasbeen sustainablyfarmedintheU.S.TheMonterey BayAquarium’swebsitehasawell-regarded guidetoresponsibleseafoodchoices.

Whilericeandveggiesare cooking,mixmayoandrooster sauceinsmallbowl.Add1tsp wateratatimeuntilitreaches adrizzlingconsistency.Place tunasteaksonhotgrillandsear for1minuteperside.Remove fromheat.Sliceagainstgrain½ inchthick.(Theinsidewillstill bepink.)Addriceandveggies tobowls.Topwithslicedgrilled tuna.Drizzlespicymayoover top.Sprinklewithscallion greens.Servewithlimewedge.

Mayfair but make it 2023 Dressing, THE DISH

MAYFAIR DRESSING WAS CREATED AT THE MAYFAIR HOTEL IN ST. LOUIS BY CHEF FRED BANGERTER AND INTRODUCED TO AN INTERNATIONAL CROWD AT THE 1904 WORLD’S FAIR. It has largely faded into the background over time, likely for several reasons. Similar to a Caesar, but not as widely known, Mayfair borders on gloopy, thick and texturally off-pu ing, thanks to the inclusion of blended raw celery and onion. Creamier dressings have fallen out of favor, with the acid hit of vinaigre es stealing the show.

It doesn’t have to be this way: Mayfair dressing is flavorful at its core, but the issue lies in how the pieces fit together. In this recipe, celery leaves replace stalks, and shallots – more at home in dressings than other alliums – take the place of onion. Safety and convenience have shi ed the original backbone from raw egg yolk and oil to store-bought mayonnaise; we’re shi ing it back with a simple garlic aïoli as the base. I’ve added a li le more acid here in the form of Champagne vinegar – a callback to the Champagne in the original recipe – that bumps up the tartness and thins the mixture out beautifully. If you’re concerned about the raw egg, purchase pasteurized eggs, which have been heated to kill bacteria that can cause food-borne illnesses. Bo om line? With a few shi s and substitutions, the once-maligned Mayfair dressing gets a second chance at life. Try it on its namesake salad, composed of iceberg and romaine le uce, sliced ham, Swiss cheese and croutons.

MAYFAIR DRESSING

YIELDS | ONE CUP | GARLIC AÏOLI

1 -2 cloves garlic, grated

¼ tsp kosher salt

1 large egg yolk

1 Tbsp lemon juice, freshly squeezed and strained

¼ cup grapeseed oil

¼ cup olive oil

MAYFAIR DRESSING

1¼ cups celery leaves, roughly chopped and loosely packed

¼ cup shallot, minced

2 oz tinned anchovies, rinsed, roughly chopped

1½ Tbsp Dijon mustard

2 Tbsp Champagne vinegar

1 Tbsp lemon juice, freshly squeezed and strained

¾ tsp black pepper

½ cup garlic aïoli

kosher salt, to taste

/ preparation– garlic aïoli / Add garlic, salt, egg yolk and lemon juice to the bowl of a food processor and pulse a few times to blend. With the motor on, stream in grapeseed and olive oils slowly until mixture emulsifies.

/ preparation– mayfair dressing / Add celery leaves, shallot, anchovies, mustard, vinegar and lemon juice to the same food processor bowl with the aïoli still inside. Pulse to incorporate and break down; scrape sides of bowl and turn motor in to blend until smooth. Season with salt to taste, if needed.

LAND FROM the

THE INDIGENOUS FOODS OF ST. LOUIS

The culinary history of the St. Louis area began long before the French se led here in the 1700s. It started thousands of years ago with the land’s Indigenous peoples. They hunted for deer, gathered nuts and fruits and grew corn and squash. Still today, Native Americans from the Midwest continue to cook with these foodstuffs to nourish their communities.

Rooted in the Earth

To understand what Indigenous communities in the St. Louis area ate and why, there’s no be er place to start than the archaeological record. Julie Zimmermann, an anthropology professor at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, explains that Native peoples from the region ate a lot of deer and nuts roughly 8,000 years ago. They began to domesticate plants about 4,000 years later. One of the most important plants – Chenopodium berlandieri, commonly known today as goosefoot – is similar to present-day quinoa. Although other Indigenous groups typically used beans as a key source of protein, Zimmermann explains, Native Americans in the St. Louis area used Chenopodium berlandieri as a critical ingredient for this nutrient.

Other vital domesticated crops included sunflowers, squash and sumpweed (a spiky herb with an edible seed). These crops helped form what academics call the Eastern Agricultural Complex. In 900 A.D. – about 1,100 years ago – the EAC was a critical source of food. Maize was first introduced around this time. “I would make the argument that Cahokia [Mounds] would not have been possible without corn,” Zimmerman says. This cheap, readily available carbohydrate helped sustain the large population that developed at the Illinois se lement.

A er the decline of Cahokia Mounds around the 13th century, the Oneota (who evidence suggests were bison hunters) and Illini peoples se led in the same area. On the Missouri side of the river, the Osage moved to this area in the same time frame. Other important Missouri foods Indigenous people ate included pawpaws, persimmons, sumac and yonkapin (wild lotus root).

Sunflower

Sumpweed

Goosefoot

Persimmon

Corn

Sumpweed

Goosefoot

Persimmon

Corn

Foodways to the Forefront

Each year, the Kathryn M. Buder Center for American Indian Studies at Washington University in St. Louis hosts an event called “Hunt. Fish. Gather.” The center invites an Indigenous chef to showcase Indigenous ingredients and speak about food justice. Eric Pinto, who is connected to the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and the Zuni tribe, serves as the assistant director at the center and helps put on the annual event. “We focus on the foods that would have been hunted, fished and gathered in this region right here,” Pinto says. Past years’ dishes have included roasted quail with pumpkin seeds and amaranth, as well as fish stew with catfish, mussels, crayfish and wilted chard.

The culinary team also focuses on highlighting traditional Indigenous ingredients that o en get overlooked, including spicebush, sumac and sassafras. At the 2022 event, Pinto put together a tea station that offered teas brewed from these plants. “They’re not just to drink; [we can use] a lot of our teas as medicine for ourselves and for healing purposes,” he says.

The idea of food as medicine is deeply rooted in Osage communities today. In a video series on cooking from the Osage Nation, members express how they approach cooking. “For us, food was medicine, and when we cook, we’re pu ing prayers into that food – and that makes that food extremely powerful,” member Paula Stabler says. “It’s a spiritual act to cook food for people.” Dishes common among the Osage Nation today include chicken dumplings, candied squash, grape dumplings and pork steam-fry.

Learn

by by“Decolonizing Diet Project Cookbook”

by

Presenter Eric Pinto

Chef Nephi Craig

Hunt. Fish. Gather. Dinner

by

Presenter Eric Pinto

Chef Nephi Craig

Hunt. Fish. Gather. Dinner

“New Native Kitchen”

Freddie Bitsoie and James O. Fraioli

“The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen”

Beth Dooley and Sean Sherman

Martin Reinhardt, Leora Lancaster and April Lindala

about INDIGENOUS CUISINES with these cookbooks.

Reclamation After Removal

In the 1830s, the U.S. government forcibly relocated the Osage, Illini and other peoples to Kansas and later Oklahoma. Forced removal not only made traditional ingredients inaccessible to Indigenous groups, but also placed them on agriculturally less productive land, creating impacts that are still felt today. The reservation system reduced their access to land and water, and they often had to turn to premade ration foods provided by the government. “The government was giving commodity-type foods … basically, think of those as survival foods; they’re generally very high in refined carbohydrates and high sugars,” Pinto says. “They keep us alive, but we know long term-wise, it’s not good for our health.”

The legacy of that policy is evident in the current health issues Native American communities are facing. According to the Department of Health and Human Services, 48.1 percent of Indigenous people are obese; with an adult diabetes rate of 23.5 percent, Indigenous adults are almost three times more likely than the non-Hispanic white population to be diagnosed with diabetes. “On top of it, in these rural areas, you don’t have access to stores – the nice grocery stores we have in St. Louis,” Pinto adds.

Many Indigenous communities and activists have developed food sovereignty projects to address these long-running problems. The National Congress of American Indians defines food sovereignty as “the right to … cultivate, access and secure nutritious, culturally essential food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods.” These projects often happen on the local level.

For example, take the Osage Nations’ Harvest Land: a plot of land used to grow fruits and vegetables for tribal members. The project supplies an elementary school and an Elder Nutrition Program with fresh produce. “A lot of tribes are starting to now dive into food sovereignty; it’s just really bringing back a lot of those practices and the foods that were kind of lost,” Pinto says.

Events like “Hunt. Fish. Gather.” help raise awareness about Indigenous food justice in the wider community. Pinto is hopeful that people will continue to learn more about these systemic issues. “There’s just a lack of awareness and education about native peoples or cultures in St. Louis,” he says. “Our people have been here for thousands of years. We know how to live with the environment.”

Kathryn M. Buder Center for American Indian Studies, sites.wustl.edu/budercenter Osage Nation, osageculture.com

Kathryn M. Buder Center for American Indian Studies, sites.wustl.edu/budercenter Osage Nation, osageculture.com

Decades of Damage

THE ORIGINS OF FOOD INSECURITY IN ST. LOUIS TODAY

WRITTEN BY CHARLOTTE RENNER |THE FIT & FOOD CONNECTION PHOTOS BY CHARLOTTE RENNERThe USDA divides food insecurity into two categories:

LOW FOOD SECURITY: Lower quality, variety or desirability of foods

VERY LOW FOOD SECURITY: Multiple cases of missed meals and decreased food intake

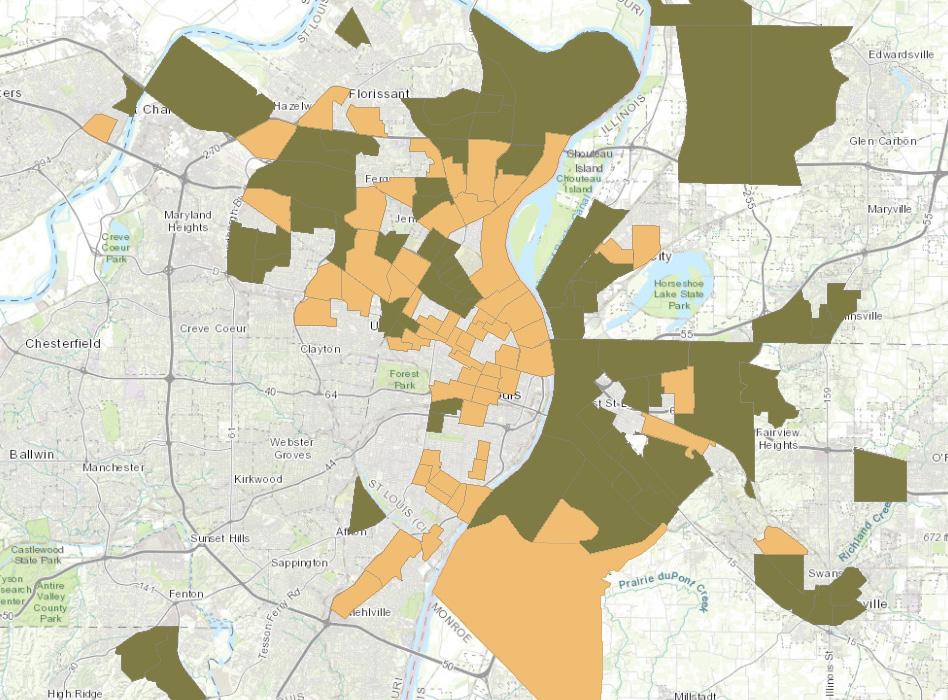

Map

This map details the areas of St. Louis that have a poverty rate of 20 percent or higher, low access to supermarkets and low access to vehicles, according to the 2019 USDA Food Access Research Atlas. For more information, visit ers.usda.gov.

Yellow: Low-income census tract where more than 100 housing units do not have a vehicle and are more than a half-mile from the nearest supermarket.

Green: Low-income census tract where more than 100 housing units do not have a vehicle and are more than 1 mile from the nearest supermarket.

Plastic bags rustle and footsteps pound on the floor on a Sunday morning inside a North County church. Teresa Ramsey and other volunteers from local nonprofit The Fit and Food Connection rush to prepare food for almost 50 families. In each bag, volunteers place a set amount of healthy food products – bunches of kale, cartons of eggs and cans of vegetables – based on the family’s size. Ramsey’s pace quickens, and in a matter of minutes, the bags are transported to the church’s entrance hall, where they await delivery drivers who will take the pantry’s food directly to families in need. After a few minutes, Ramsey loads up her own car with bags to deliver on her own. “I’m here almost every Sunday,” she says. This program is just one way that the nonprofit aims to fight against food insecurity in its community.

According to The Fit and Food Connection, access to healthy food is far from a guaranteed resource in St. Louis – as of 2020, more than 200,000 individuals in the metro area are food insecure. On the surface, food deserts might appear to be a reason for this. But in reality, they’re just one symptom of a larger systemic problem that intersects with public health, housing, crime and racial equity.

“The kind of food that folks are able to consistently access is really one of the building blocks of health,” Katie Kaufmann, senior strategist at Missouri Foundation for Health, says. “[Lack of access to healthy food] is a problem that’s been going on for generations.”

The historical policies that ultimately led to food insecurity in St. Louis also had enduring racially discriminatory impacts, Kaufmann adds. Today, activists and organizers are using innovative methods to reverse the decades of damage.

Although it might seem as though food deserts just “exist,” according to Webster University cultural anthropology professor Jong Bum Kwon, these inequities are anything but happenstance.

“People who are a bit more progressive or radical in their political orientation would actually call food deserts more like food apartheid, or an issue of food justice, which is then related to these larger issues around racial justice,” Kwon says. “A lack of affordable and nutritious food is simply one consequence or symptom of a broader system of structural or institutionalized racism. And I think that is actually the more appropriate way to look at it.”

UNDERSTANDING THE CAUSES OF SEGREGATED FOOD INSECURITY IN ST. LOUIS REQUIRES A LOOK BACK AT PAST HOUSING AND REDLINING POLICIES.

1916: St. Louis Real Estate Exchange successfully gets a racial zoning ordinance placed on the 1916 citywide ballot. It passes, prohibiting Black residents from purchasing homes or residing on blocks with more than 75 percent white residents.

1917: In Buchanan V. Warley, the Supreme Court finds racial zoning unconstitutional as a violation of the 14th Amendment.

1920-40: Deed covenants are established by local developers; they bind homeowners to restrict certain land use, including race of occupant. These covenants prevent a growing Black population in St. Louis from purchasing homes.

1934: The Federal Housing Administration is established to insure bank loans for housing; it makes funds available for a massive surveying and evaluation of existing housing stock. It develops residential security maps to assess whether housing in a neighborhood is a good or bad financial risk, which ultimately sustains segregation.

1937: St. Louis is redlined. The residential security map divides the city and county into four categories labeled A through D and gives areas with increasing Black populations a lower grade. This discourages mortgage lenders from offering financial assistance for purchasing homes in lower grade – usually minoritypopulated – areas.

1959: The city demolishes the predominantly Black neighborhood Mill Creek Valley to build Highway 40 and industrial zones.

St. Charles Hazelwood Florissant Ferguson Berkeley Jennings St. Louis Affton Mehlville Fenton Cahokia Dupo Swansea Belleville East St. Louis Granite City Collinsville Columbia Bottom Map source: USDA Economic Research Service, ESRI. ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/go-to-the-atlas Heather Zago, The Fit and Food Connection program directorImportant Food Access Definitions to Know

food desert: an area that has limited access to affordable and nutritious food (Oxford Languages)

food apartheid: a term used to highlight the lack of access to healthy food caused by a system of institutional racial segregation and discrimination (Stray Dog Institute)

food justice: a grassroots initiative that began in response to food insecurity and economic pressures that prevent access to healthy, nutritious and culturally relevant foods (“Cultivating Food Justice”)

1968: The Fair Housing Act passes. It prohibits discrimination in the sale, rental and financing of housing based on race, religion, national origin or sex.

The legacy of redlining and discriminatory housing practices lives on in St. Louis today in many ways, including through the availability of quality food in primarily Black neighborhoods, especially in north St. Louis city and North County. Erica Williams, founder and executive director of nonprofit A Red Circle, experienced this disinvestment firsthand. Growing up in North County, Williams watched as three major supermarkets – Schnucks, Kroger and National – closed their doors, which left her neighborhood without access to healthy food.

Now, A Red Circle provides fresh produce from its community garden and urban farms to these areas and offers programming designed to educate the community about healthy eating and cooking. “When you have a region that’s a food desert, it becomes other types of deserts – an opportunity desert, a jobs desert,” Williams says. “We really want to bring up the region of North County, not just grow food and give it out.”

The organization’s next move is to open a community-owned and -run grocery store, which will create more job opportunities. This holistic approach is the one that will be the most beneficial for the communities themselves, according to Kwon.

“What would it mean if we actually have a worker-owned and -run

grocery store, in which the people who live in the neighborhood work there and take care of these things – to empower neighborhoods, rather than simply serve?” Kwon says. “[The service provision] is a model of charity rather than a model of empowerment. Part of it is we need to empower communities to do what’s right for their own communities, give them the opportunity to grow and develop and give them the resources to do so.”

Just as it took decades of discriminatory policies to create the issues we have today, it will take decades of positive change to dismantle them. That’s why the Missouri Foundation for Health recently launched a 20-year food justice initiative with the goal to support existing organizations dedicated to the cause (like A Red Circle); remove barriers to access programs like SNAP (formerly known as food stamps); and build up community-run, equitable and resilient food systems.

With these methods, MFH hopes to provide healthy, affordable and culturally relevant food to Missourians in need. “We really believe that this is an issue that undercuts many of the health challenges that Missourians face,” Kaufmann says. “It’s one that we want to take on because we think that that will help accelerate some of the other changes that the foundation is invested in, like infant mortality, behavioral health and well-being – even things like our violence prevention work.”

Another organization dedicated to looking at the whole picture is The Fit and Food Connection, which realized that because many

as likely as white residents to live in census tracts with low access to healthy food.

Black St. Louis city residents are nearly

St. Louisans are 1 in 6 1 in 6 which is more than 200,000 individuals.

food insecure,

(The City of St. Louis)

(The Fit and Food Connection, 2020)Teresa Ramsey, The Fit and Food Connection volunteer

Culturally Relevant Food

We know there’s a variety of different palates in our state and a variety of different considerations that folks navigate, whether it’s a diet you’re trying to maintain for health reasons like diabetes or high blood pressure or a choice you’ve made about being vegetarian or vegan. We also recognize that there are a variety of cultures that are present in our state: folks who may want access to food that is kosher or halal. Diet, preferences and choices are valid across the spectrum but may not be able to be consistently served by our traditional system.

− Katie Kaufmann, MFH

− Katie Kaufmann, MFH

of its community members don’t have cars, simply getting to the organization’s food pantry was an obstacle. So every other Sunday, the nonprofit’s staff and volunteers gather healthy food products and fresh produce from their community garden and deliver them directly to their members’ doors.

Executive director and co-founder Gabi Cole says the nonprofit focuses on not only getting healthy food to its community members, but also providing information on healthy lifestyles and empowering people to incorporate healthy choices into their daily lives. To do this, The Fit and Food Connection offers classes that range from exercise and gardening to strategic shopping and cooking. “We want to put little, small pieces in where you are eating better and talking to yourself well, and it’s not just about the things you eat,” Cole says. “It’s about how your mobility, your mindset, the environment you’re in, and the people you have around you play a part in your overall healthy lifestyle journey. It’s very important to this community because it’s been vacant and left behind for so long.”

To help organizations like The Fit and Food Connection and A Red Circle, donating your time or money is the best way to continue moving these vital efforts forward. But more than anything, Kaufmann hopes people will continue to educate themselves on what food insecurity truly looks like in St. Louis and Missouri as a whole. “Recognize that this is a challenge that Missourians across the state are facing – not because they’re not good, hardworking people, but because the system is set up to disadvantage some of our community members.”

People's Harvest illustration courtesy of A Red Circle, architect Koupa + Knoop

Community garden photo courtesy of A Red Circle

People's Harvest illustration courtesy of A Red Circle, architect Koupa + Knoop

Community garden photo courtesy of A Red Circle

Hop

Alley

WRITTEN BY MARY ANDINO | PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE MISSOURI HISTORY MUSEUMThe legacy of St. Louis’ Chinatown

Close to the location where Busch Stadium stands today was once a thriving Asian community of people and businesses. From 1869 to 1966, the area between 7th and 8th streets from Walnut to Market was known as “Hop Alley” – St. Louis’ Chinatown. Although the neighborhood no longer stands, its history and legacy hold many lessons about immigration, food culture and displacement in the metro area.

AN IMMIGRANT COMMUNITY

Beginning in the mid-19th century, people from China (mainly men) began to immigrate to the United States in large waves, according to Magdalene Linck, assistant librarian for the Missouri Historical Society. The first Chinese immigrant came to St. Louis in 1857, and the Chinese population gradually increased over time. By 1890, there was a population of 170 Chinese people in the city and, by 1910, there were 423 people. One might think that a population of hundreds in a city with a population of hundreds of thousands might not have a significant impact, but Hop Alley and its many businesses proved otherwise.

Hop Alley was home to a variety of shops, merchants and businesses, especially laundries. By 1914, there were more than 12 Chinese grocers in the few blocks that comprised Hop Alley. These businesses offered fresh vegetables and imported ingredients from China that residents couldn’t source anywhere else, like dried shrimp, fish and noodles. These small stores and grocers were not only a source of foodstuffs, but also, a reminder of home for many. Annie Leong owned one such grocery store, Asia Food Products, along with the popular Hop Alley restaurant Asia Café. Her brother Wing Leong shared his memories of the area in an oral history for the Missouri History Museum. “People – especially the natives that grew up in China that moved to the United States – wanted something that reminded them of their home,” Leong said.

COMMUNITY LEADERS

Owners of these restaurants were important leaders in the Chinese community. Joe Lin, who owned The Orient Restaurant, was referred to as “the unofficial mayor of Chinatown.” He was president of the On Leong Merchants Association, a major community organization in Hop Alley. He assisted Chinese residents who didn’t speak English by acting as an interpreter in legal ma ers and court cases.

According to Wing Leong, his sister Annie fulfilled a similar role and acted as a representative for the neighborhood to the media.

“Most of these people didn’t speak English, so the people that owned the big Chinese restaurants, laundries, businesses would rely on her as a communicator/spokesperson for Chinatown,” Leong said. “She was the one who would tell the reporters, so they always quoted her in the newspapers. I look at her kind of as the pacifier of any controversy that comes up. She was able, always, to explain it in such a way that it calmed everything down.”

c.1930s

1960s St. Louis Post-Dispatch news clipping

1904 map of Hop Alley

Joe Lin

c.1930s

1960s St. Louis Post-Dispatch news clipping

1904 map of Hop Alley

Joe Lin

CHANGING TASTES

Initially, restaurants in Hop Alley catered to single male immigrants by offering them authentic food and a taste of home. Over time, Chinese restaurants shifted to cater more toward an American palate, Linck explains. By the 1920s, food like chop suey had become the in vogue cuisine for the general American audience. “In those days, the popularity was chop suey, chow mein, egg foo young,” Leong said.

Restaurants like Asia Café attracted a bevy of non-Chinese customers, from local policemen and government officials to singers and performers. An ad for The Orient Restaurant in a 1917 edition of the St. Louis Post Dispatch reads, “We take pride in announcing to the public the opening of our beautiful Chinese Chop Suey and American Restaurant, where you can enjoy good things to eat, prepared by the most famous Chinese chefs in the country.”

The Orient served dishes we recognize today as Chinese American classics, from fried rice to war mein (stir-fried noodles with mushrooms, bok choy, bean sprouts and meat). Another restaurant, Chu Wah, served egg rolls, wonton soup, pineapple chicken and sweet and sour shrimp. Over time, Chinese restaurants conformed to American palates by embracing more meat and fried dishes to attract more business.

ENDINGS AND NEW BEGINNINGS

Asia Café operated until 1965, when residents had to move to make way for the creation of Busch Stadium and other construction. The development project might have been the last straw for Hop Alley and may have shut down Asia Café, but the area had been losing residents for years beforehand. The children of the area’s immigrant residents had gradually moved away to other parts of the city. “The children were so Americanized; they went to college, they moved to the suburbs,” Leong said. “In the end, [by the time] Chinatown totally disappeared, all of the old folks [had] died and all of the offspring moved away.”

This displacement, however, was definitely not the end for Asian-owned businesses in St. Louis. By the 1990s, a new sort of Chinatown was developing in St. Louis along Olive Boulevard near Interstate 170. Today, it hosts restaurants offering a wide variety of Asian cuisines, including Korean, Sichuan, Cantonese and Vietnamese food, plus bubble tea, dumplings, hot pot and more. Cate Zone Chinese Cafe, ChiliSpot and Soup Dumplings STL have all become fan-favorite restaurants.

Xin Wei, owner of Corner 17 in University City, says Chinese restaurants today still walk a tightrope of balancing between American audiences and traditional ingredients. For instance, Wei might tone down the spiciness of a dish but will continue to make fresh noodles by hand through traditional techniques. “If you only served authentic Chinese, yes, you would get customers, but it’s just unlikely for you to make money in the long term to be sustainable,” he says.

Today’s Asian-owned businesses face challenges similar to the ones in Hop Alley did: forced displacement and generational change. In 2022, Olive Boulevard became home to a new Costco wholesale retailer; developers and U-City officials worked in conjunction to compel residents and businesses owners to move or close up shop using a variety of tactics, including buying properties and changing policies on leases. Other recent challenges have included rising food costs and labor shortages. Wei also notes that the children of some area Asian-owned restaurants want to embrace different careers. “My friends’ parents own a Chinese, small carryout restaurant that’s really busy, but my friend doesn’t want to take it over … so their parents have to close down the restaurant,” he says.

Although the business landscape on Olive Boulevard is full of obstacles, there are bright spots. The area near Washington University in St. Louis has been a boon for these restaurants. “When school is in [session], you see Asian students come to your restaurant,” Wei says. International students comprise nearly 24 percent of Wash U’s student body; this diverse student population has embraced the wide array of cultural cuisines close to their campus. “International students bring you more business, and that way, it’s possible to keep more traditional dishes,” Wei adds.

Take a drive down Olive Boulevard or visit one of the many restaurants there, and you’ll see why the legacy of Hop Alley has never truly left St. Louis. From tasty Americanized takeout and St. Paul sandwiches to traditional, family-owned spots, a variety of Asian-owned businesses have made their home in this city, and they’re here to stay.

CHILISPOT

CATE ZONE CHINESE CAFE

SOUP DUMPLING STL

CHILISPOT

CATE ZONE CHINESE CAFE

SOUP DUMPLING STL

There’snothinglikeenjoyinga Missouriafternoonorbeautifulsunset eveningwithoneofMissouri’smost uniquewinesinhand.That’soneof themanyperkstheWildSunWinery &BreweryinHillsboroofferswhen youvisittheirbreathtaking10-acre estate.Openyear-round,thishistoric propertyhasplentytoenjoyfrom seasontoseason.

“Themainhousedatesbackto1870, soithasaveryhistoricalaspect,” saidMarkBaehmann,winemaker andco-ownerofWildSunWinery& Brewery.“Thepropertyalsohasalot ofold-growthtreesthatarehundreds ofyearsold.Tiethatinwiththeopen fieldsandthelake,anditevokesavery comfortableyetelegantfeeling.”

Duringwarmermonths,guestsare invitedtobringblankets,lawnchairs andsmalltablestopicniconthe

property’sgrassyknolls.Inthewinter, visitorscandrinkintheviewsfromthe comfortoftheheated,enclosedareas.

DISCOVERNEWWINES ORSAVOROLDFAVORITES

UniquetoWildSunisanatmosphere that’saseducationalasitisrelaxing. Whetherapproachedbyanowner orservedbyabrandaficionado, patronslearnaboutthelocation’s extraordinarywinevarieties.Atthe tastingbar,a$10sampler(fourwines servedinsophisticatedglasses) comeswithanintriguinglessonon thehistoryandflavorprofileof eachglass.

Don’tbesurprisedif,duringatasting, youfallinlovewithoneofWildSun’s drywines.Missouriansfamiliarwith thearea’ssweetervarietiessayWild Sun’sextensivelistofdrywhitesand redsarearevelation.Thebrandeven

offerssparklingchampagneinthedry styleforoccasionswhentoastingisin order.Buttheirsweetwineshavealot ofloyalfans,too.

“Whilewespecializeindrywines,we alsoofferaselectionofsweetwines inordertoaccommodateall ofour guests,”saidEdWagner,coowner ofWildSunWinery&Brewery.“Our goalistoprovidepremiumproducts acrosstheboardwhileeducatingour guestsinafriendly,nonintimidating atmosphere.”

ENJOYEVENTS,CRAFTBEERS ANDGOURMETCOMFORTFOOD

Inadditiontotheiraward-winning wines,WildSunservesanimpressive selectionofcraftbeersaswellastheir ownlineofspringwater.Although guestsarewelcometopackabasket ofsnackstoenjoyalongsidetheir qualitybeverage,amenuofgourmet

pizzas,savoryentreesandartisan breadsisavailable—amustduring specialcelebrationsandthemed events,includingon-propertyyoga sessionsandpaint-and-sipclasses.

WildSunofferslivemusicontheir WildSun-SetFridaynights,aswellas SaturdayandSundayafternoonsMay throughOctober.Justliketheirgrapes, themusicaltalentishandselected toshowcasethebestMissourihas tooffer.

SEETHEGARDEN INAWHOLENEWLIGHT.

PRESENTING CHIHULYINTHEGARDEN2023

There’ssomethingnewbloomingatthegardenandit’sunlikeanythingyou’ve everseenbefore.Experienceanall-newexhibitbyworld-renownedartistDaleChihuly curatedexpresslyfortheMissouriBotanicalGarden.Oncethesungoesdown,joinus forChihulyNights—illuminatedeveningsfeaturingart,livemusic,andcocktails allsummerlong.Formoreinformation,visitmobot.org/chihuly

DaytimeViewing,May2–October15|9AM–5PM ChihulyNights,Thursday–Sunday|May13–August27|6–10PM Advanceticketpurchaseisrecommended.

DaleChihuly EndofDayPersianPond (detail),2022. ©2023ChihulyStudio.Allrightsreserved. ©2023MissouriBotanicalGarden.

Presentedby

Sponsors

DaleChihuly EndofDayPersianPond (detail),2022. ©2023ChihulyStudio.Allrightsreserved. ©2023MissouriBotanicalGarden.

Presentedby

Sponsors