elio ciol RESPIRI DI VIAGGIO

Progettazione grafica / Graphic design

Carolina Tomasin per

Foto / Photos

Elio Ciol

Traduzioni / Traductions

British School of Verona

Stampa / Print

Grafiche Silz, Verona

Finito di stampare nel mese di febbraio 2021

First published February 2021

Edito da / Edited by Punto Marte editore

ISBN 978-88-94875-34-8

Copyright by Elio Ciol / Punto Marte edizioni

elio ciol

RESPIRI DI VIAGGIO BREATHING IN THE SCENE

CASARSA DELLA DELIZIA, SPAZIO ESPOSITIVO EX SALA CONSILIARE MARZO-GIUGNO 2021

Promosso da Città di Casarsa della Delizia

Con il sostegno di Camera di Commercio di Pordenone - Udine

Confcommercio Imprese per l’Italia Ascom Pordenone

Unione Artigiani PordenoneConfartigianato Imprese

Consorzio di Sviluppo Economico Locale del Ponte Rosso - Tagliamento ITAS Mutua

Con la collaborazione di Pro Casarsa della Delizia

Testi di Fulvio dell’Agnese

Allestimento sala espositiva

DM+B & Associati

Organised by The Municipality of Casarsa della Delizia

With the support of Pordenone – Udine Chamber of Commerce Confcommercio Imprese per l’Italia Ascom Pordenone Unione Artigiani PordenoneConfartigianato Imprese Consorzio di Sviluppo Economico Locale del Ponte Rosso - Tagliamento ITAS Mutua

With the cooperation of Association for the Promotion of Casarsa della Delizia

Words Fulvio dell’Agnese

Exhibition hall setup

DM+B & Associati

A proposito di viaggi…

Questa mostra dal titolo “Respiri di viaggio” è una raccolta di foto che ho avuto la fortuna di scattare durante i miei viaggi all’estero. Fissavo nella pellicola quello che mi colpiva come cosa nuova, inaspettata, esuberante e in armonia con il luogo che visitavo, sempre così lontano dal mio Friuli.

E già gioivo di poter poi mostrare le immagini a tante persone, amici, e far godere anche i loro occhi. Ora è arrivato questo momento grazie alla collaborazione e al sostegno del Comune del mio Paese, Casarsa Della Delizia, che ringrazio molto e che nonostante la terribile situazione del Coronavirus è riuscito a realizzare questa mostra.

Ed è del tutto casuale che questo evento si realizzi in un tempo assai prossimo, voglia o non voglia, al grande viaggio che mi aspetta.

Un grande viaggio verso il mistero dell’Infinito e all’incontro con il creatore della luce, delle stelle -di una immensità di stelle- e della nostra terra.

Ma soprattutto con l’Autore dell’amore fraterno.

Un incontro che spero avvenga in tanta luce e pace.

About journeys…

This exhibition, titled “Breathing in the Scene”, is a collection of photos I was lucky enough to take on my travels around the world.

I captured on my rolls of film what struck me as being new, unexpected, bright and in harmony with the place I was exploring, far from my beloved home region of Friuli in the north-east of Italy. It was joy enough for me to show my pictures to my friends and other people, and see their eyes light up as mine did, but now, thanks to the cooperation and support of the Municipal Council in my hometown of Casarsa della Delizia, I have the opportunity to show these images to a wider audience. My sincerest thanks go the Council for managing to organize this event despite the terrible Coronavirus pandemic.

It’s totally coincidental that this event is being held so close to the great journey which awaits me, whether I want to make it or not.

My last journey will take me towards the mysteries of the infinite and a meeting with the Creator of light, of stars – an infinity of stars –, of our earth and, above all, of brotherly love.

I hope this meeting will be filled with light and peace.

Elio Ciol Casarsa, marzo (march) 2021

Respiri di viaggio è il percorso espositivo con il quale la città di Casarsa della Delizia intende rendere omaggio ai traguardi di vita e professionali di Elio Ciol, da oltre settant’anni sublime tessitore di luce, maestro della fotografia contemporanea.

Stima e gratitudine si uniscono in questa azione culturale all’impegno volto ad onorare la generosa donazione effettuata dal maestro nel 2016: oltre settecento opere, ora patrimonio del Comune, tra le quali si contano numerose fotografie già acquisite dalle collezioni permanenti di alcuni tra i importanti musei del mondo, quali il Metropolitan Museum of Art di New York, il Center for Creative Photography di Tucson, il Victoria and Albert Museum di Londra sino al Museo Pushkin di Mosca. Nel 2017, con una mostra di grande successo di pubblico e di critica, ha preso avvio un progetto culturale di lungo respiro che si propone, nel nome di Elio Ciol, di promuovere Casarsa come punto di riferimento regionale dell’arte fotografica.

A questo intendimento risponde la presente proposta espositiva, che non mancherà di sorprendere ed emozionare. In mostra, accanto ad opere presenti nel fondo comunale, susciteranno certamente interesse le numerose fotografie inedite, non solo in bianco e nero ma anche a colori, riprese dal maestro nei tanti viaggi in molti paesi del mondo.

‘Breathing in the Scene’ is the exhibition organised by the municipal council of Casarsa della Delizia to pay homage to the professional and personal achievements of Elio Ciol, our homespun master of contemporary photography who has been making tapestries of light for over seventy years.

The exhibition is a demonstration of our respect and gratitude for the generous donation made by Ciol in 2016 –more than seven hundred works are now owned by the town, many of which have been added to the permanent collections of some of the most important museums in the world: the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, to name a few. In 2017, an exhibition which met with the appreciation of critics as well as the general public marked the starting point of a broad-ranging Arts project using the name of Elio Ciol to promote Casarsa della Delizia as the flagship for the photographic arts in our region. This new exhibition is the product of the same desire, and we’re sure it won’t fail to surprise and delight. The photographs on show are not only from our collection – there are also a number of previously unseen works which will certainly be appreciated. Some are in black and white, while others are in full colour, but all of them were taken by Ciol on his many travels around the world. At a time like this, when we are faced with unprecedented restrictions on our movements, our natural desire to

In un tempo di costrizioni nel quale ci misuriamo con un’inusuale esperienza di limite, si agita in noi più urgente che mai il bisogno naturale di movimento. La vita ha sete di viaggio e la mostra osa una risposta con un’esperienza culturale attraverso un suggestivo itinerario fotografico attorno a questo tema. Un rincorrersi di architetture, paesaggi e colori lontani conquistati da Elio Ciol, la cui grazia è capace di vedere e custodire. I luoghi hanno bisogno di qualcuno che li racconti. E il maestro con la sua sensibilità ci accompagna in questa narrazione visiva che provoca in noi la reazione desiderata dello stupore, di un nuovo inatteso, di una gioia che sgorga dal vedere cose mai viste, dal conoscerle, dal saperle vere. Ed ecco il miracolo. Il cammino fisico impossibile si invera in noi nel viaggio più difficile e trasformativo, quello da noi stessi a noi stessi.

Un sincero ringraziamento agli enti e alle realtà economiche che hanno scelto di sostenere la realizzazione di questo evento, certi che investire soprattutto oggi in cultura significhi investire nel futuro.

Un grazie particolare al prof. Fulvio Dell’Agnese, curatore della mostra, al quale è toccato il privilegio di affiancare il maestro Ciol nel minuzioso e sistematico lavoro di selezione degli scatti e di ideazione del percorso espositivo, consegnando al visitatore parole leggere e vibranti, preziosa bussola di orientamento. Ogni viaggio inizia con la partenza, prepariamoci ad avere occhi nuovi e facciamo il primo passo. Buon viaggio!

move and explore is felt more strongly than ever. Life is hungry for journeys and with this exhibition we hope to provide a cultural experience which speaks to this need through a series of art photographs about travel. It’s a procession of architecture, landscapes and colours from the far-off lands Elio Ciol has conquered with his lens and whose grace he has always captured with mastery. Places need someone to talk about them, and Ciol’s sensitivity guides us through this visual story, arousing the desired reactions in us: amazement, wonder at unexpected sights, the joy of discovering new things and of feeling their realness. Herein lies the miracle: the physical journey we can’t make at the moment is transformed into a more difficult one – our own inner journey. We would like to express our sincere thanks to the public bodies and private enterprises which have given their support to this event, knowing that investing in the Arts more than ever means investing in the future.

Special thanks must go to Prof. Fulvio Dell’Agnese, the exhibition curator, who has had the privilege of working closely with Ciol in the painstaking task of systematically reviewing his works in order to decide on the exhibition theme and select the works for display, and whose words will provide visitors with a precious compass orientating them as they walk with Ciol on his travels. Every journey begins with a departure – let’s get ready to look at the world from a new point of view and set off. Enjoy the journey!

Lavinia Clarotto

Sindaca della Città di Casarsa della Delizia Mayor of Casarsa della Delizia

Fabio Cristante

Assessore alle Politiche Culturali e del Territorio Spokesman for the Arts and the Municipal Territory

Sindaca della Città di Casarsa della Delizia Mayor of Casarsa della Delizia

Fabio Cristante

Assessore alle Politiche Culturali e del Territorio Spokesman for the Arts and the Municipal Territory

8

LO SGUARDO SELETTIVO DEL VIAGGIATORE

di Fulvio Dell’Agnese

Ci sono differenti maniere per girare il mondo in compagnia di una fotocamera. Quella attualmente più in uso è la pratica dei selfie, e la conosciamo tutti. Basta avere uno smartphone in tasca, impugnarlo, estendere al massimo il braccio – ma se volete una prolunga in alluminio la gamma di soluzioni va da Amazon agli ambulanti sul Ponte degli Scalzi, a Venezia – e scattare. Il risultato sarà la vostra faccia che occupa un terzo dell’inquadratura e, sullo sfondo, un brandello di realtà turistica che viene riscattato dal suo torpore – talora millenario –, dalla sua grigia esistenza di monumento, opera d’arte o paesaggio grazie alla vostra presenza, la cui attestazione visiva è a quel punto pronta per essere “postata” e condivisa con un mondo di frequentatori dei social sicuramente ansioso di sapere dove siete e cosa state facendo.

Un’alternativa valida anche se un po’ fuori moda ai selfie è costituita dall’approccio fotograficamente bulimico al viaggio, di cui oggi ricordiamo – non senza una certa tenerezza – le prime comparse nel secolo scorso, con le comitive di Giapponesi che erano in grado di attraversare città come Roma o Firenze traguardando costantemente i Fori imperiali o la Galleria degli Uffizi attraverso il mirino della reflex. La loro era una ingenuità fanciullesca che – anche prima di facebook e instagram – impediva di ritenere posseduto un luogo o vissuta un’opera d’arte fino a quando questi non fossero stati registrati sulla pellicola, più o meno rumorosamente deglutiti dall’apparecchio fotografico e dal suo otturatore.

Ovvio che il digitale abbia dilatato i termini possibili dell’abbuffata: il mondo circostante si offre all’obbiettivo senza più i limiti dettati dal criterio di contenimento degli scatti, una volta eliminati i costi della pellicola e l’ingombro dei rullini. Ne sono conseguenza collaterale i grumi di spazzatura visiva che si accumulano, in formato jpeg, nelle memorie dei computer; ma anche la scomparsa delle chilometriche sessioni di diapositive con cui le conquiste del viaggiatore venivano partecipate ad amici e parenti. Per rinfrescare la memoria al riguardo – o per evocare i tratti della situazione a vantaggio dei più giovani – basti pensare alla geniale scena di Playtime (1967), in cui Jacques Tati, nelle vesti di Monsieur Hulot, a casa di un amico impiega tutte le proprie energie per sottrarsi con eleganza al rito del telo bianco e del proiettore, prima che il caricatore venga inserito e che sullo schermo compaiano – cadenzate dal cla-clac del braccio meccanico – le prime immagini delle vacanze estive: fotografie sicuramente innocenti nella loro vacuità, ingenue come quelle che nello stesso film una giovane turista, appena scaricata da un pullman a Parigi, cerca di scattare a una fioraia al primo angolo di strada, mettendola in posa con dolcezza come se si dovesse ordinatamente integrare in una scenografia predisposta.

9

Esiste infine una terza via per vivere il viaggio attraverso la fotografia, incentrata sulla selezione. Alla portata del viaggiatore comune, essa delinea i contorni di una dimensione comunque popolare dell’esplorazione, ma pretende normalmente un grado maggiore di attenzione, una concentrata disponibilità percettiva: a Siena entriamo tutti, prima o poi, in Piazza del Campo, ma forse è solo se ci rendiamo conto di avere trovato in quella conca il «gheriglio stesso della città»1 che – avendo una fotocamera a tracolla – decideremo di cercare un’inquadratura che testimoni una simile sensazione; che racconti – se ne avremo il coraggio e sentiremo il bisogno di tentarlo – la nostra intimità di quell’istante con il luogo, «come se fossimo entrati in uno spazio che ci apparteneva, uno spazio dove eravamo attesi»2

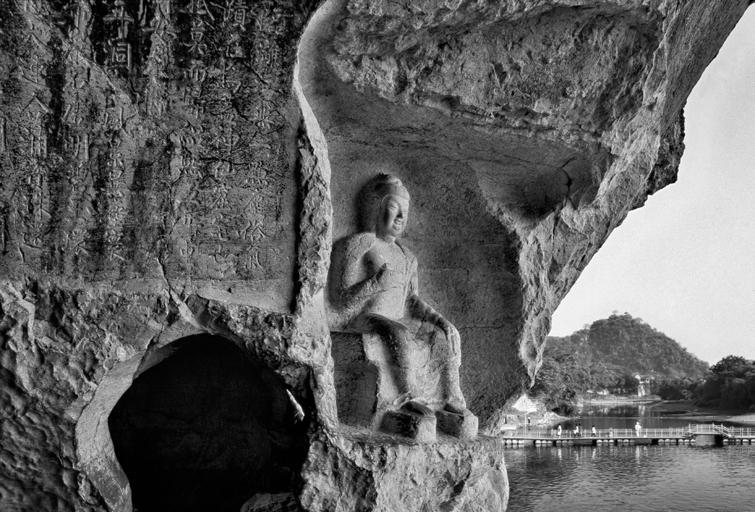

Il caso su cui verte questa mostra non è diverso nella sostanza, ma assai differente dalla media nel risultato formale. Fotografo di professione, ma in giro per diletto, fuori da ogni logica standard di reportage, Elio Ciol ha realizzato nel corso degli anni e dei suoi molti viaggi centinaia di immagini che hanno catturato – con la maestria che da sempre gli viene riconosciuta, e che pure continua a stupire – momenti di privato incanto di fronte a un edificio monumentale, a un paesaggio urbano, a un graffito rupestre o ad una parata militare. Immagini di grande tensione espressiva, capaci di eludere il brusio turistico che solitamente appanna le lenti, e che sembrano frutto di un miracoloso arrestarsi del tempo: non solo quello insito nel processo fotografico – la realtà che si incide sulla pellicola e viene sottratta in fragmento alla quotidiana cronologia del divenire – ma anche quello, altrettanto decisivo, che pare aver consentito all’autore di operare in contesti non pienamente governabili, ben distanti dalla docilità di un set preordinato. Come sarà stato possibile, in pochi minuti rubati al gruppo dei compagni di viaggio, trovare il tempo e la sospensione del respiro per scatti così calibrati, che sembrano frutto di calcolate esposizioni e studi compositivi, attuati con ponderazione al cavalletto?

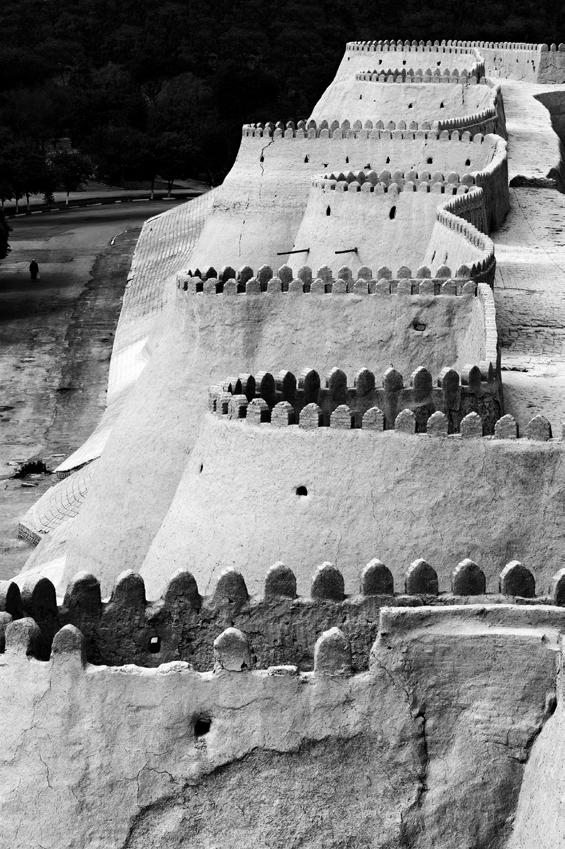

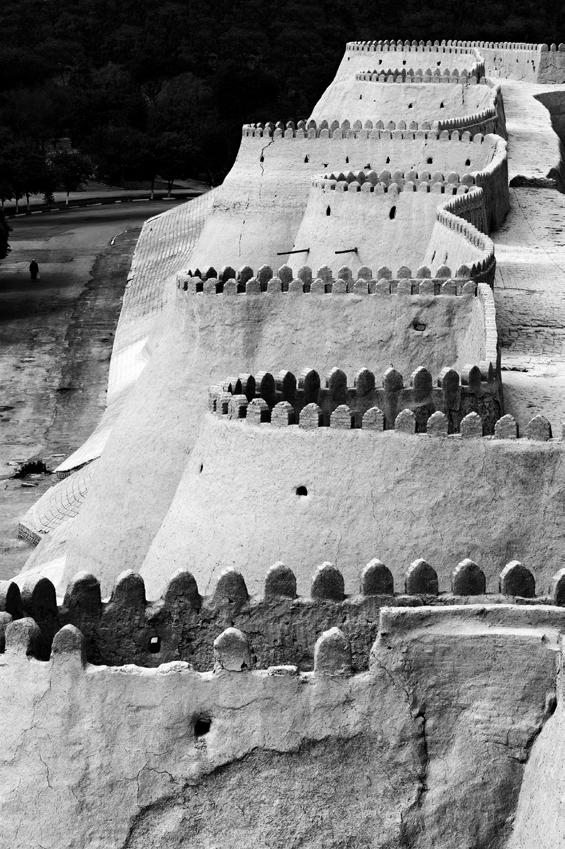

Due casi esemplari sono quelli di Khiva e Santorini. Le mura di Khiva, con le loro merlature, costruiscono nella vista dall’alto un serpeggiante merletto che fa venire in mente le panche del Parco Güell di Gaudì, in versione metafisica: niente trencadis coloratissimi, niente persone. Su questi bastioni, o ai loro piedi, pare esserci spazio solo per uno stupore contemplativo, di fronte ai perfetti innesti delle masse architettoniche. Al punto che non sarebbe poi così strano veder sbucare all’orizzonte il pennacchio di fumo di una locomotiva coi suoi vagoni, come in un De Chirico degli anni dieci…

«E tuttavia le immagini di Ciol, sempre per merito di un calibratissimo uso delle risorse della fotografia, mettono anche in risalto la scabra superficie di quelle fortificazioni, per così dire la loro pelle. Allora tutta quella imponenza, quella forza e quella apparente robustezza, finiscono per lasciare intravvedere, tra le screpolature e fessurazioni del fango con cui sono state costruite quelle mura, un’interna fragilità, una nascosta debolezza, un’inesorabile precarietà di fronte al flusso della storia che erano state comandate a contenere. Il vero nemico (lo comprese alla fine anche Giovanni Drogo, il giovane ufficiale protagonista

10

1 H. MATAR, Un punto di approdo, Torino, Einaudi, 2020 [2019], p. 12.

2 Ibidem

del Deserto dei Tartari) non verrà ormai né da Sud o da Nord, né da Est o da Ovest, è già dentro le mura e aspetta che giunga il suo momento. Ecco perché, al di là delle più solide apparenze, le fortificazioni costruite nei secoli dagli uomini ci ricordano comunque, per una sorta di ironia romantica, il nostro effimero essere nel tempo» (A. Bertani)3

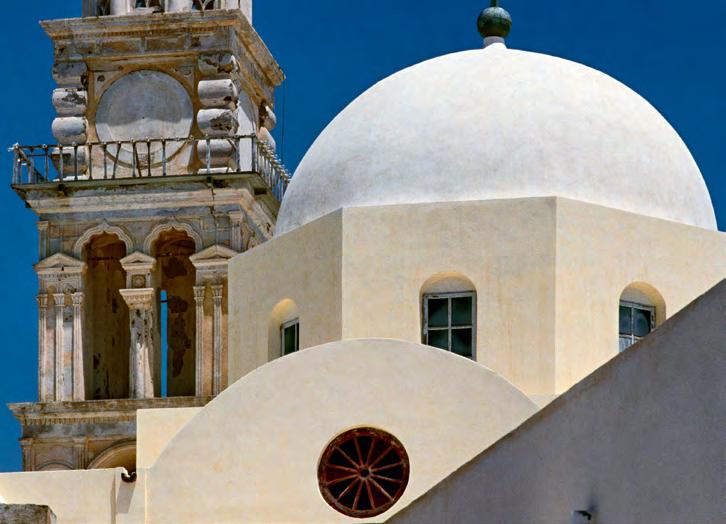

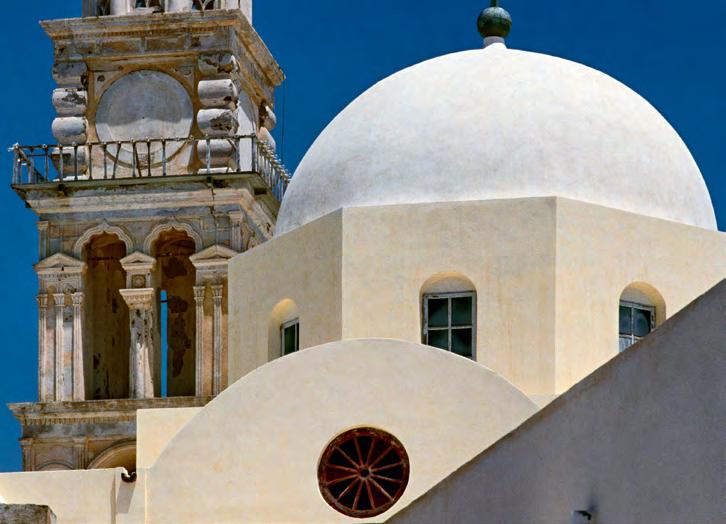

La purezza delle forme dei bastioni di Khiva si può apparentare a quella, diversamente sospesa nella luce, degli edifici di Santorini: dicromie di muri a calce e azzurri intensi, di bianchi intonaci sullo sfondo di cielo e mare. Architettura del sole, la definisce l’autore.

Qui il gioco dei riferimenti pittorici condurrebbe dalle parti di Magritte e delle sue tele dai colori compatti eppure ingannevoli: nulla ci garantisce che dietro a certe porte inquadrate da Ciol si sviluppi uno spazio realmente praticabile, che le scale sullo sfondo conducano davvero a un piano superiore della casa o comunque a una dimensione temporalmente in linea con quella di chi, come noi, osserva da fuori dell’uscio. Il battente incorniciato di giallo, una volta spalancato, non ci precipiterà dall’ombra del suo arco direttamente nella luce azzurra screziata di nubi cremose come latte? Neppure i vasi in terracotta di un’altra immagine, che la meccanica razionale della visione colloca in angoli prospettici perfettamente scanditi, sono soltanto quello che appaiono essere; antichi nel loro materiale, lo sguardo di Elio sembra scoprirli a vigilare sul blu profondo delle acque, su equilibri che affondano nel passato. «Il suo pensiero fotografico s’è immedesimato nel significato remoto, ancestrale, che l’uomo cicladico aveva dell’esistenza. Significato che Ciol ha recuperato dall’architettura recente di Santorini, segno di una continuità ideale non determinata da acritica fedeltà ai propri trascorsi, ma dall’ambiente, che, sostanzialmente, è depositario di situazioni immemorabili, che riposano, atemporali ma sempre vive, sugli assi cartesiani dei netti profili degli edifici sacri e profani: impaginazioni costruite per proporsi all’abbaglio della luce, dove il bianco delle pareti s’alterna a cielo e mare, a vegetazione e strapiombi, oggettivando la legge ottica della complementarietà dei colori. […] Terra, mare, sole, sono unici, incontrastati protagonisti di una realtà che sgomenta ed esalta e nella quale l’architettura s’è inserita senza essere sopraffatta e senza sopraffare» (L. Perissinotto). In queste immagini leggiamo, alla fine, i modi di un rapporto dell’uomo con la natura e i suoi ritmi oggi ampiamente compromesso, se non irrimediabilmente perduto.

I luoghi visitati vengono insomma sottoposti, attraverso la fotografia, a una sorta di decantazione. Viene perfino da pensare che lo sfasamento fra realtà fisicamente sperimentata e immagine stampata si sia prodotto un po’ per volta, nel buio della sacca, mentre la pellicola viaggiava verso casa per giungere al bagno di sviluppo. Trovo l’idea estremamente poetica, anche perché l’odore dei rullini fotografici e la microcorazza del loro involucro mi hanno sempre affascinato, suggerendomi la costante sensazione d’avere a che fare con qualcosa di vivo.

Non fosse che, con Elio Ciol, le cose vanno allo stesso modo anche con le immagini digitali. Il miracolo,

11

3 Il brano è tratto dal testo Le mura di Khiva, scritto da Angelo Bertani per il progetto di pubblicazione di una cartella fotografica firmata da Elio Ciol, poi rimasta inedita. Medesima sorte ebbero, in anni passati, altri scritti più avanti citati nel testo: Tosh Hovli, la Via della Seta, sempre di Angelo Bertani; Alhambra. Il Tempo incarnato di Elio Ciol e La Cattedrale di Siviglia Visioni circolari di Alessandra Santin; L’architettura del sole di Luciano Perissinotto.

dunque, non è strettamente alchemico, avviene anche in assenza di sentori ermetici; e allora non stupisce che il fotografo, oltre ad accogliere senza remore le nuove tecnologie, si dimostri pienamente disponibile al dialogo con la storia contemporanea.

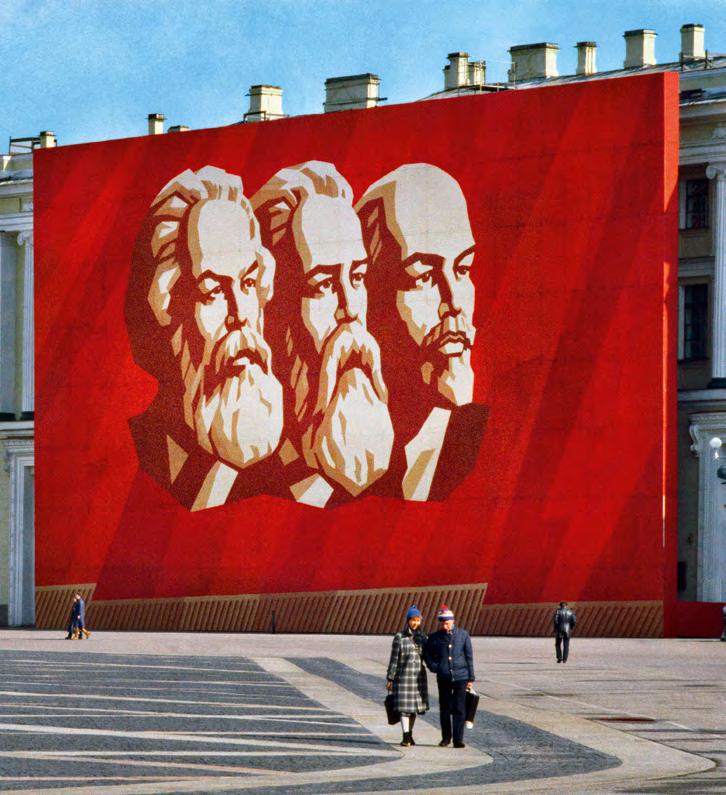

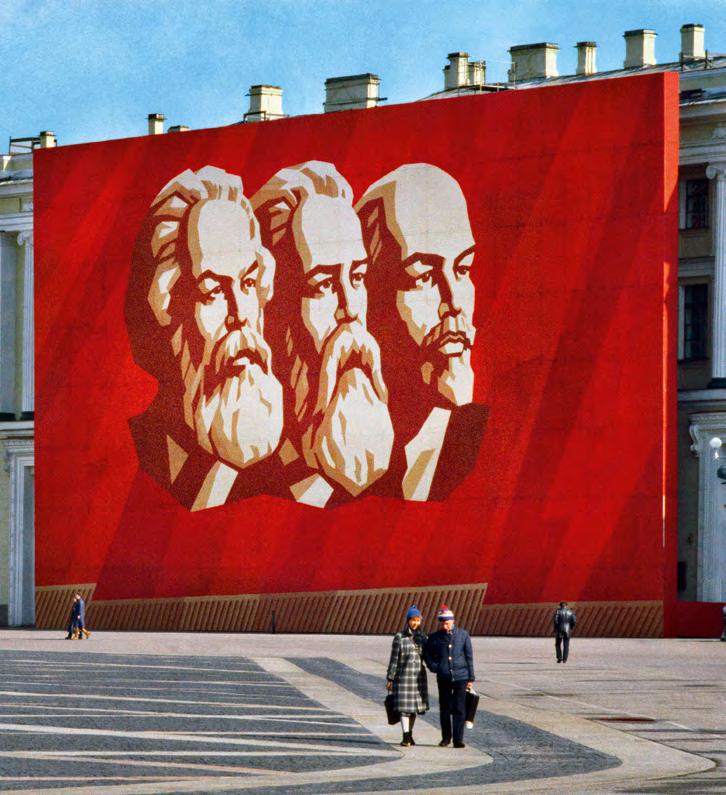

Anche se oggi è tornata a chiamarsi San Pietroburgo, la città fotografata da Ciol nel 1985 è più che mai Leningrado.

Le bandiere si muovono nella piazza – enorme scacchiera – portandosi dietro le persone, inevitabilmente ridotte a soldatini colorati nella strategia visiva della manifestazione di regime di cui osserviamo le prove. A turbare è lo scarto di scala, la sproporzione, che schiaccia anche i passanti di fronte ai giganteschi pannelli inneggianti agli eroi della rivoluzione. Che rapporto hanno le persone vere con quelle mascelle volitive dipinte su fondo rosso, con le immagini dei soldati che esibiscono le armi? O meglio, esiste un rapporto fra individuo e ideale politico – qualunque esso sia –, quando questo si declina in ideologia?

È un simile interrogativo che si snoda, sottile come un filo, lungo le linee in cui si dispongono le comparse dello spettacolo di massa, a cucire la città e la grande spianata sulla quale si svolge la celebrazione. Un disegno complesso, restituito con particolare sensibilità al colore da parte di Ciol, che “osserva” invece in bianco e nero quando davanti a lui si presentano differenti arabeschi.

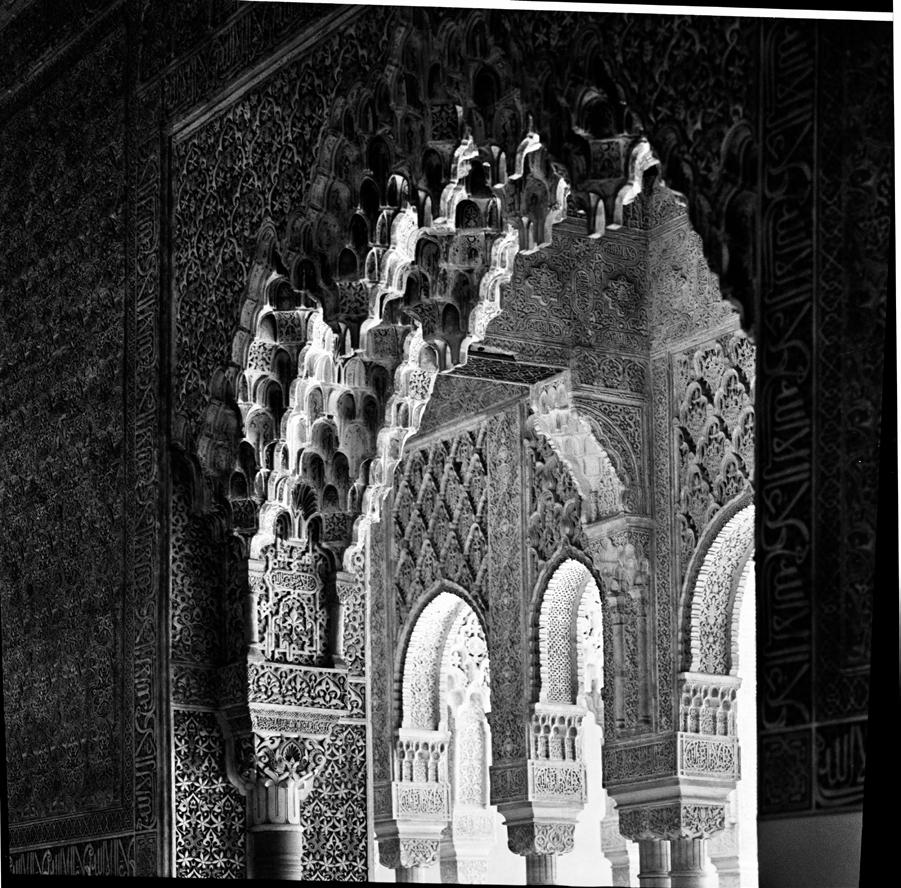

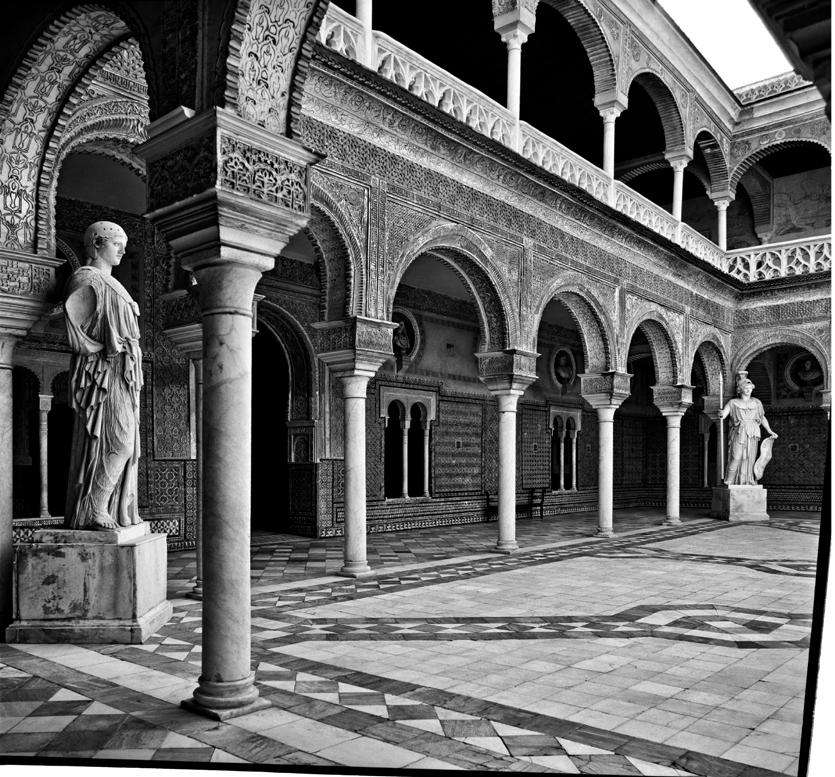

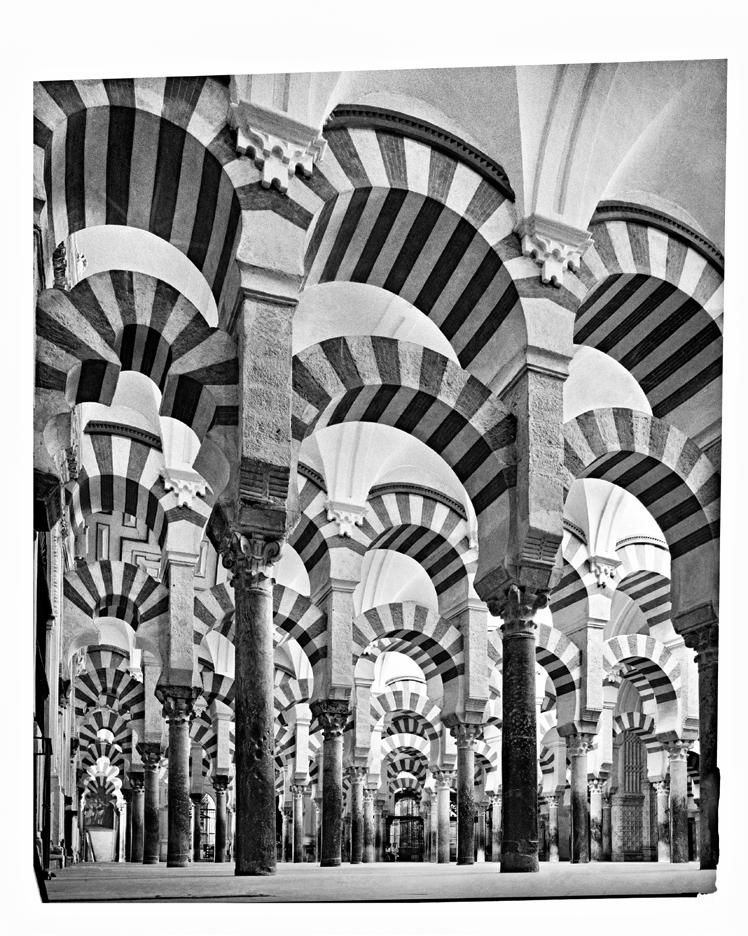

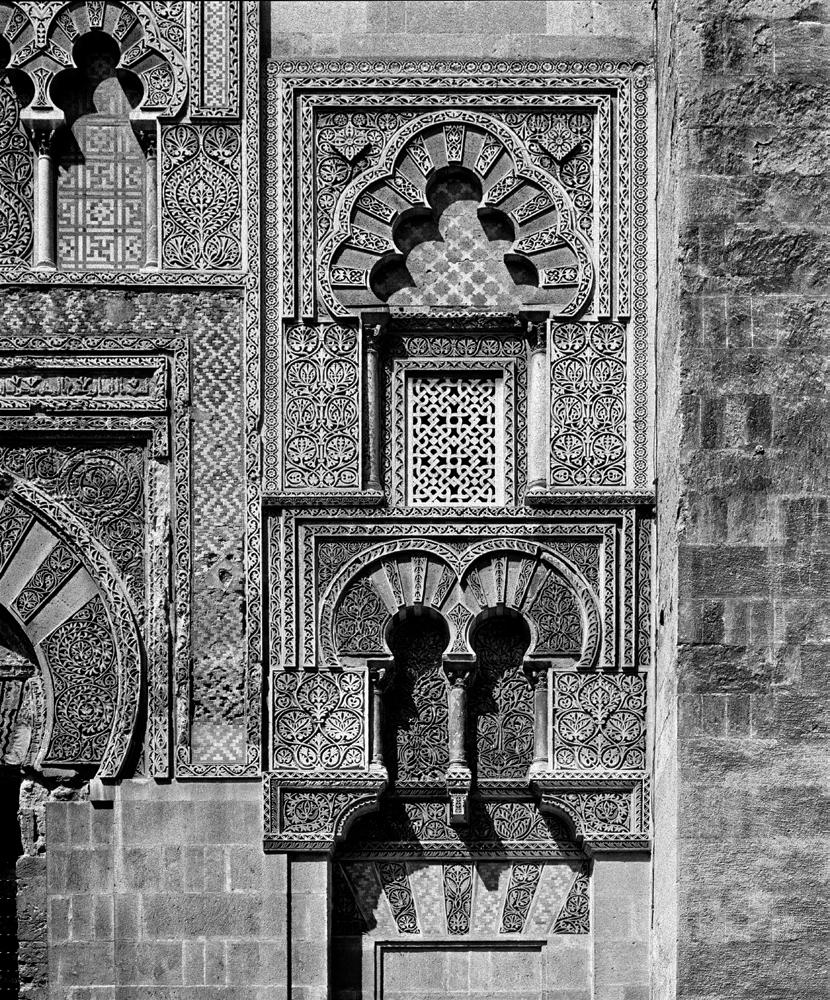

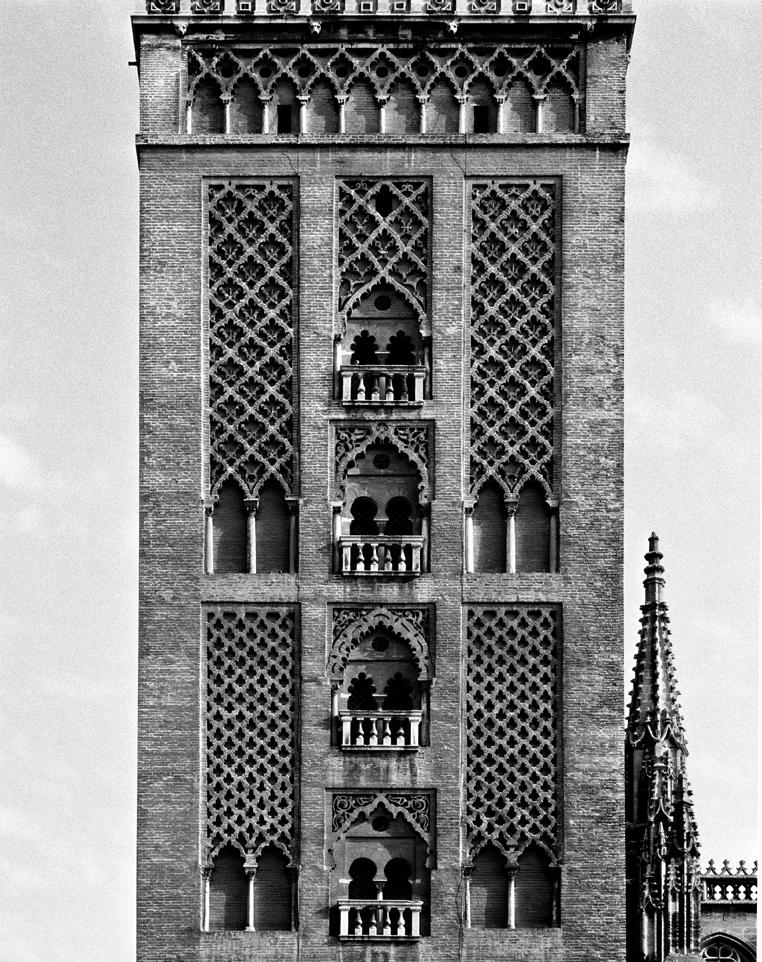

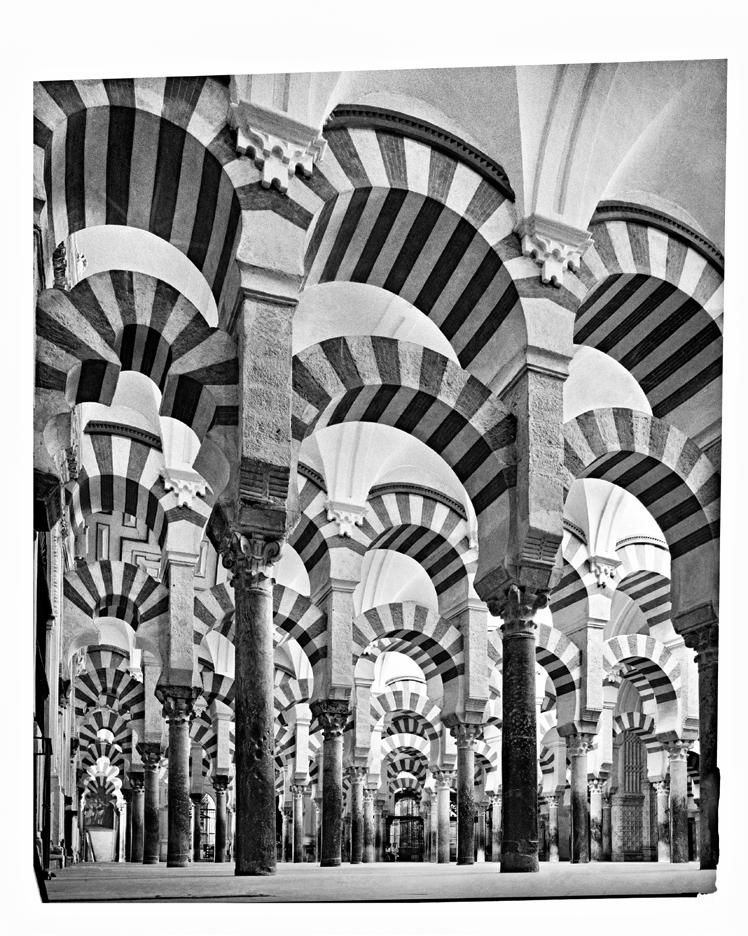

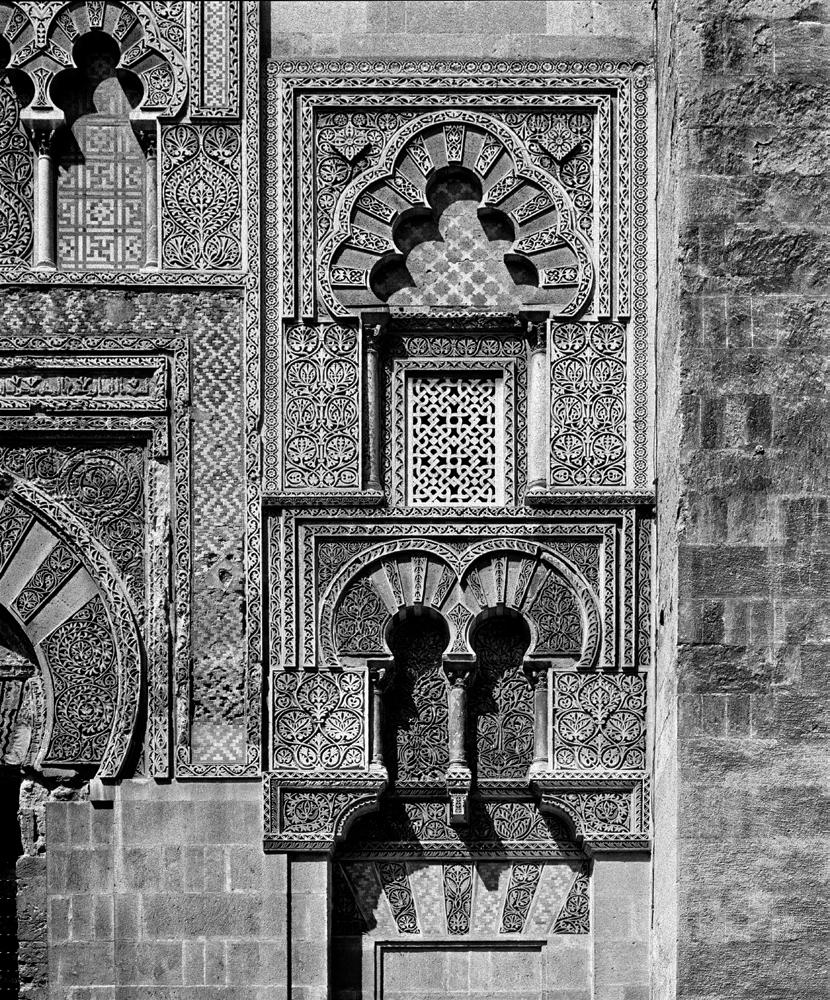

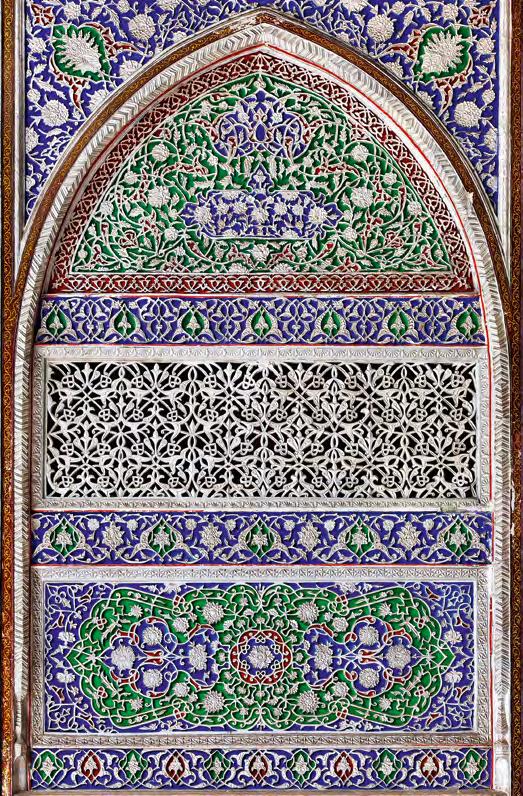

Da San Pietroburgo alla Spagna, lo stacco è marcato. Nella Moschea di Cordoba il rigoglio mozarabico degli ornamenti procede parallelo all’eco di stilemi occidentali. E il sovrapposto moltiplicarsi in profondità degli archi dai conci dicromi trasforma la selva di navate – specie di palmeto pietrificato – in un meccanismo ottico alla Escher, in un ritmo di forme architettoniche che l’inquadratura dal basso esaspera sino a renderlo astratto.

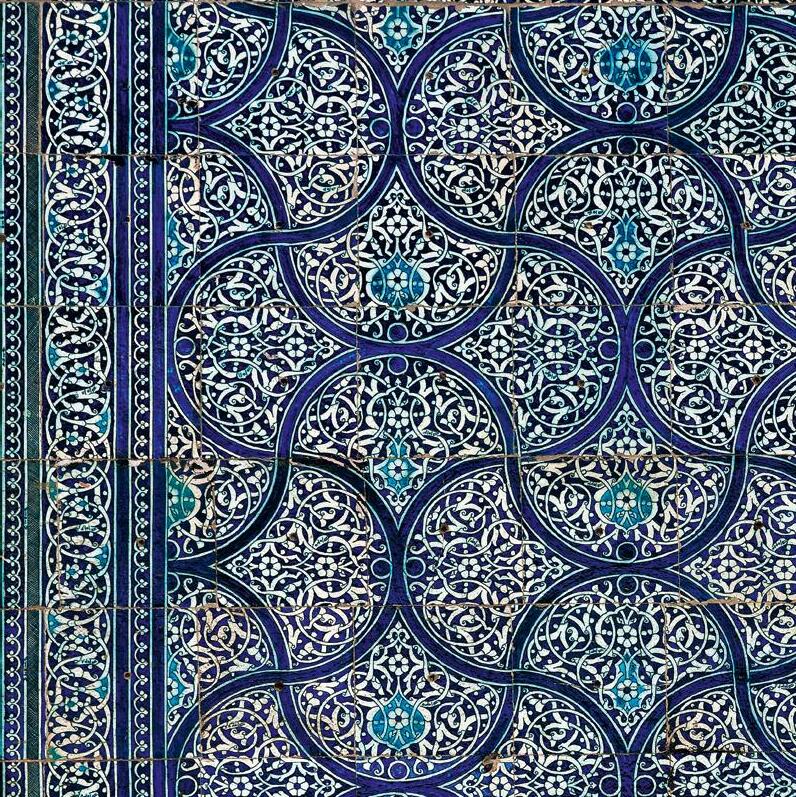

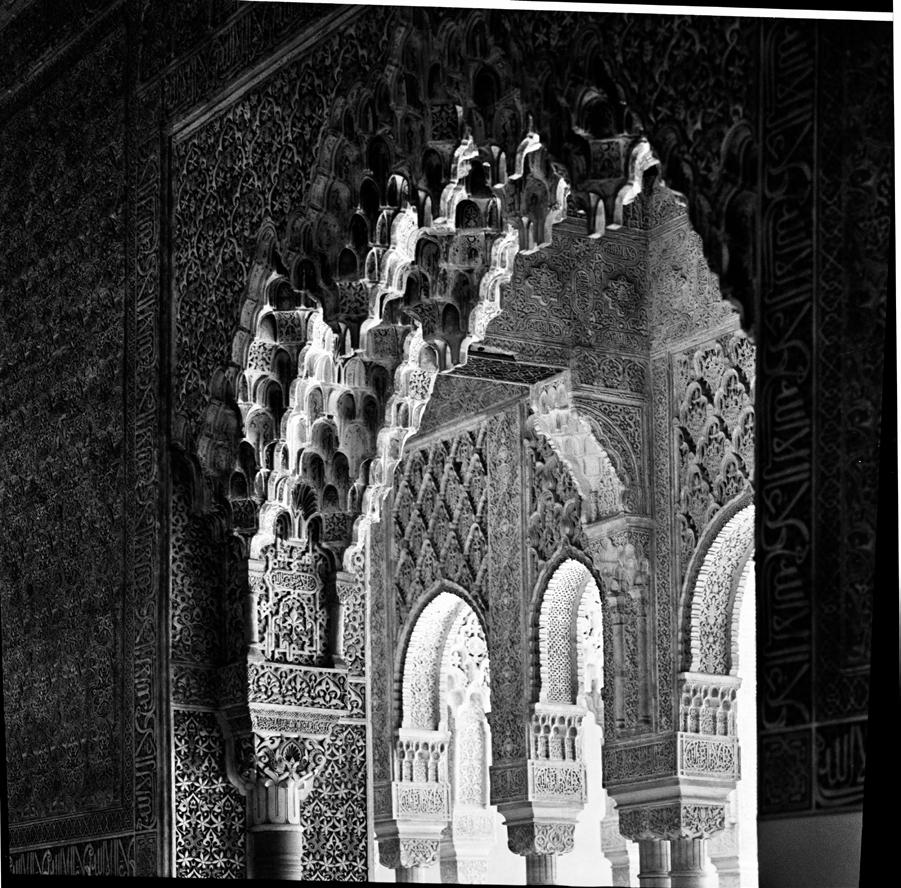

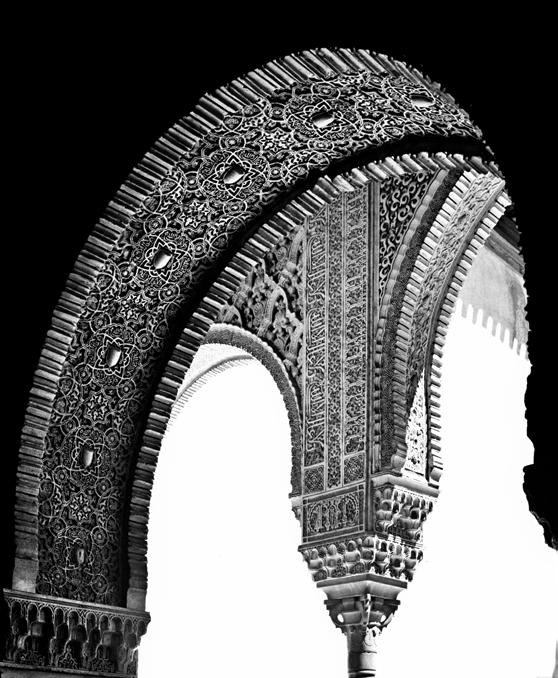

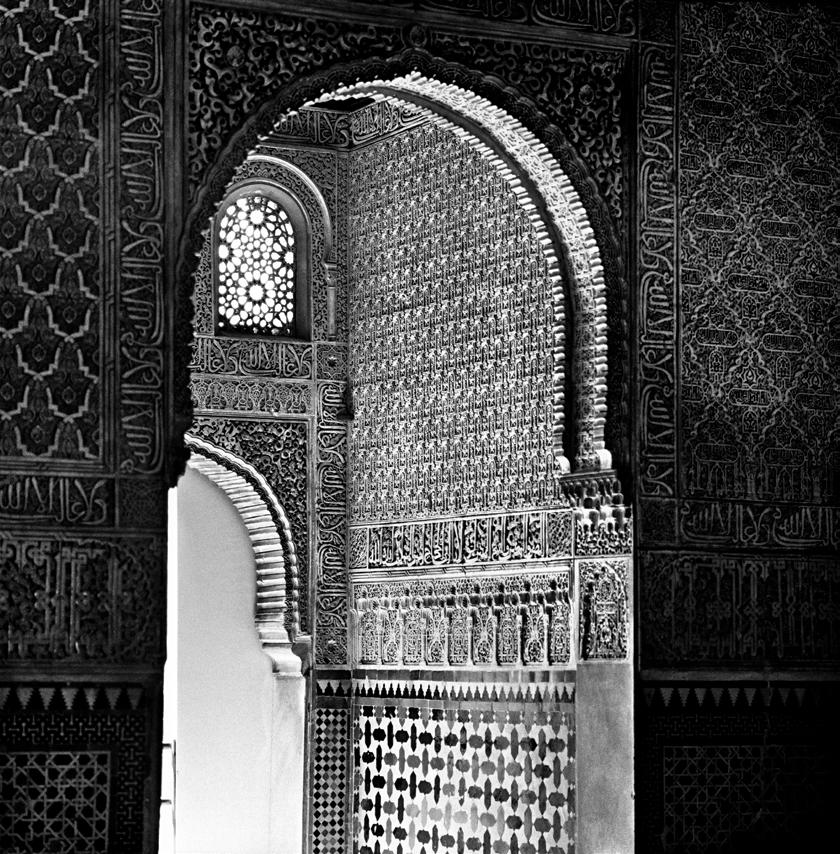

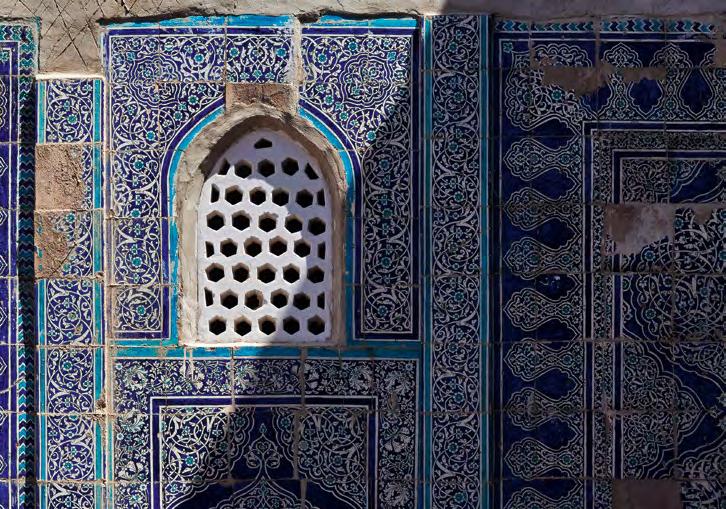

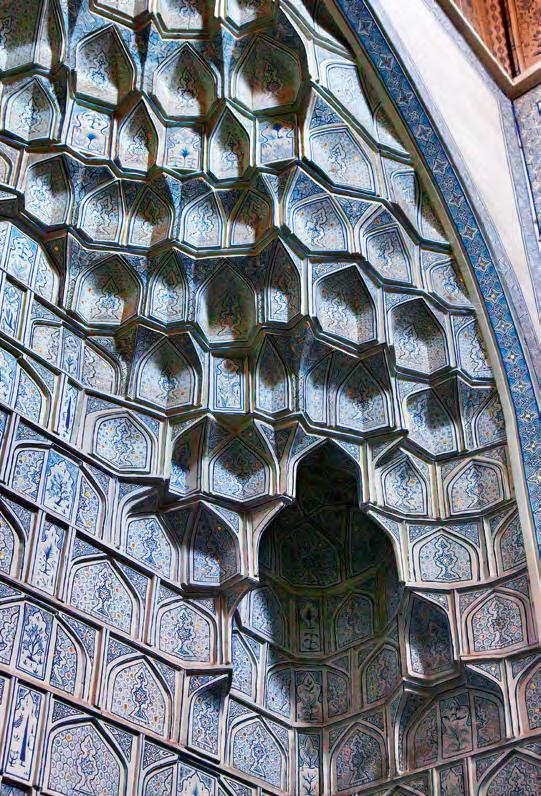

Lo sviluppo dello spazio si fonde allora con il labirinto decorativo delle superfici, esplorato in altre fotografie, in cui bifore e trifore polilobate vengono assorbite dal tessuto complessivo dei rilievi.

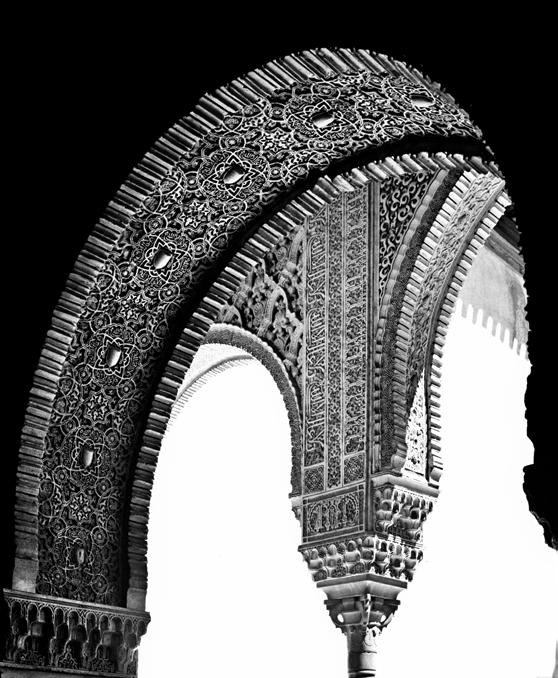

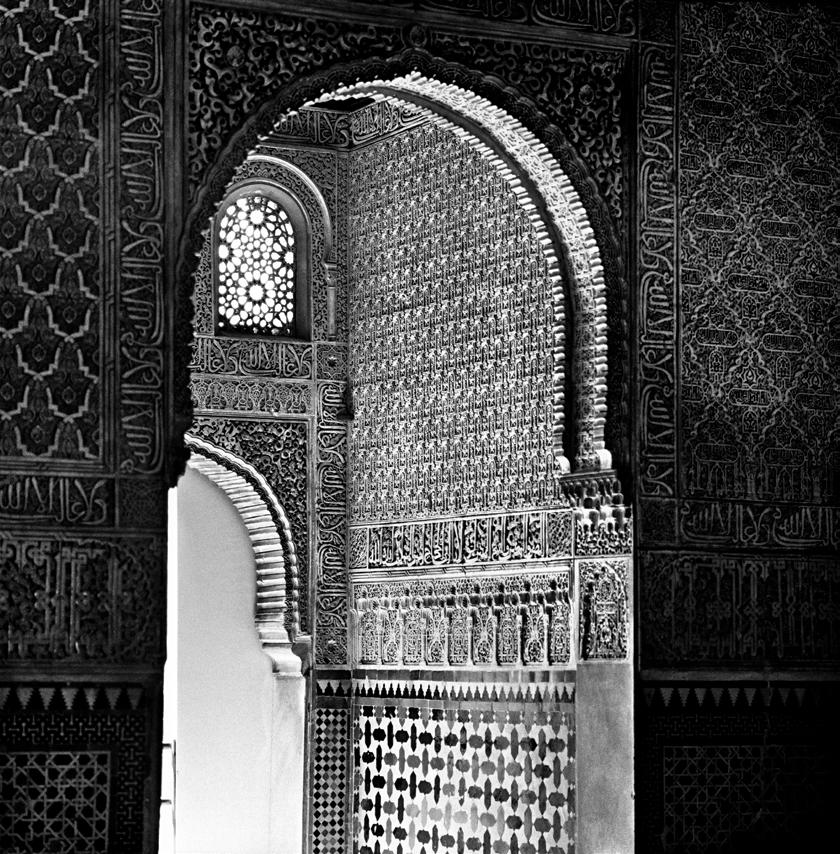

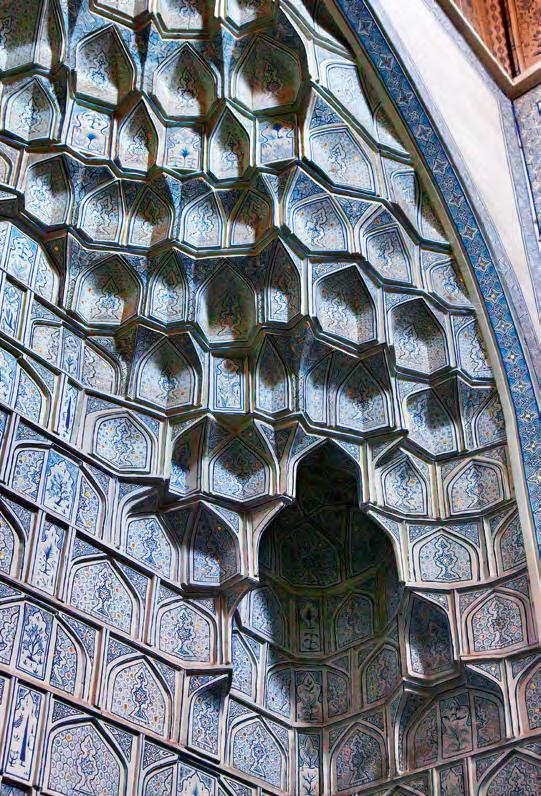

Anche all’Alhambra di Granada, nelle fotografie del 1994, i ritmi del paramento si fanno trina che smaterializza la struttura; l’autore ne ritaglia scorci che sono “recinti dinamici”, al cui interno l’occhio è invitato a un’appagata deriva, mentre il brulichio di linee, sporgenze e concavità assorbe la geometria di fondo e trasmette quasi una sensazione di fremito pulsante, di fertilità innescata dalla luce.

Le superfici «giocano con le ampie finestre ad arco acuto e con gli usci, i cui lati non poggiano al suolo, ma lo sorvolano. Intorno e al di là preludono l’indicibile. […] Gli archi e le ogive indicano luoghi possibili in cui la dimensione temporale riacquista pienamente la dimensione estatica, […] definiscono un orizzonte di attesa. Foreste di colonne, labirinti spaziali, grafie straniere, cieli candidi, alludono al viaggio, tematizzano la visione come possibilità di riflessione e di piacere, che invita ad abbandonare la separazione tra la sfera delle emozioni e quella razionale della conoscenza» (A. Santin).

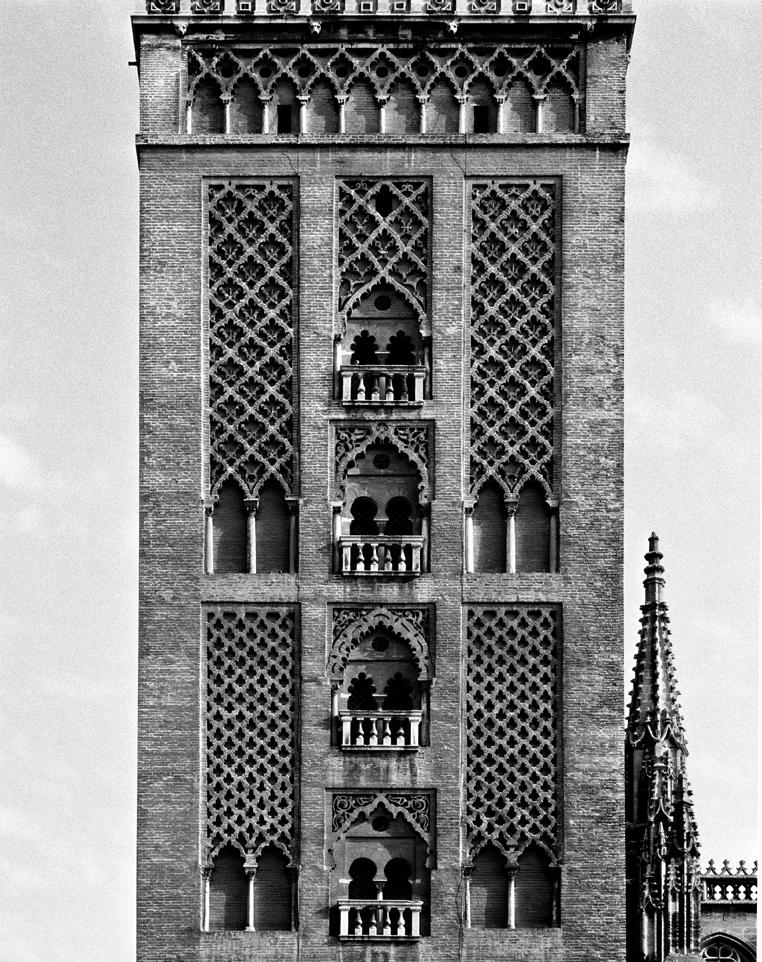

E non diversamente vengono allestiti quei “luoghi di simmetria” che sono le fotografie di Ciol della Cattedrale di Siviglia: la sua «descrizione non si interessa della globalità del corpo architettonico, ma si sofferma sul

4 «Il dettaglio, come residuo di un passato glorioso si confronta con il presente effimero, e riconduce la Storia all’Uomo. Egli è invisibile ma presente nel tondo, nella luce che rimbalza e si riflette nel buio circolare e nero; egli respira nelle soluzioni tecniche, nell’uso degli infrarossi, nell’allinearsi dei mattoni; nei marmi abilmente scolpiti che incorniciano ciò che c’è: il vuoto della finestra, il nero invisibile degli interni, il bianco piatto degli orizzonti a ridosso dello sguardo. L’assenza di profondità rende la bidimensionalità di queste opere una scelta di metodo. La statua di San Pietro, unico elemento naturalistico ritratto, conserva

12

frammento»; è «immersa in un silenzio contenente, costruita in una composizione quasi grafica” (A. Santin)4, e anche di fronte alla Giralda – eretta nel XII secolo come minareto e poi convertita a torre campanaria –Elio sceglie di ignorare il monumento e di ritagliare la simmetria di un pensiero fatto ornamento.

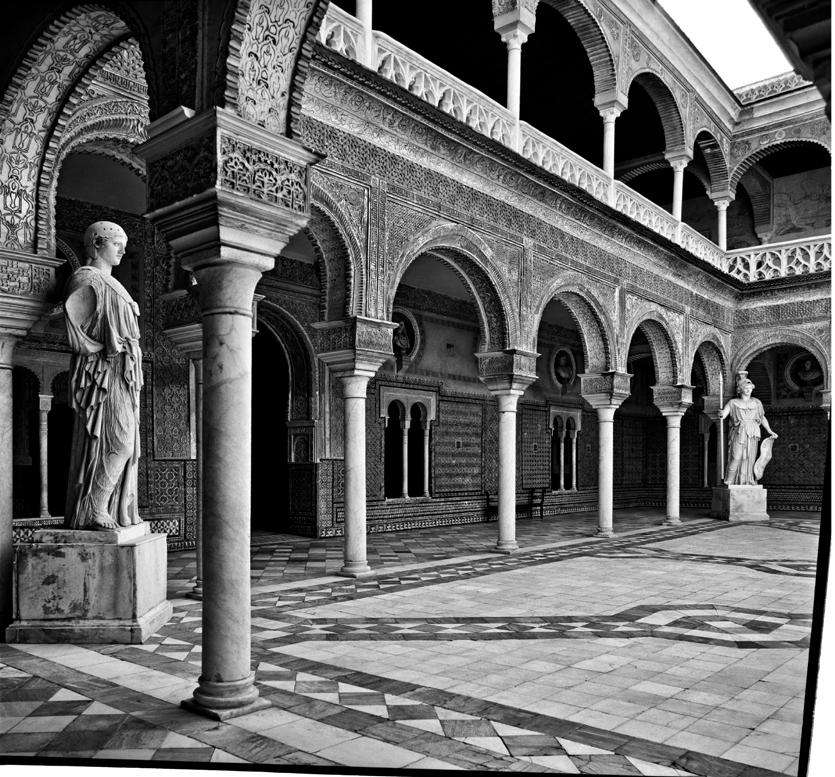

A stimolarlo non sono però solo contesti di così alto coefficiente estetico e spirituale. Anche in edifici meno fondamentali per la storia dell’arte, come – per restare a Siviglia – la Casa di Pilato, il fotografo rintraccia le condizioni per cui dal piano del vedere si operi lo scarto della “visione”. Formidabile l’assemblaggio di ombre, volumi e retrogusti storici nell’immagine in cui una figura femminile scolpita è distesa sotto a una panoplia di scudi e faretre. Chi sarà la donna? Sembra una Arianna addormentata, ma il rilievo che la sovrasta – e che pare dar corpo al suo sogno – non ha nulla di dionisiaco: le armi si attaglierebbero piuttosto all’immaginario dell’uomo che, in forma di busto imperiale, dal piedistallo a sinistra la osserva meditabondo e incombe con la sua ombra, come un amante incerto del controllo esercitabile sui pensieri e sulle passioni della sua compagna.

Ed è soprattutto il bilanciamento delle luci a trasformare il libero allestimento escogitato dal collezionista –che in tutta la casa accosta in beata incongruità classico, mudéjar e rinascimento – in metafisica suggestione del taglio d’inquadratura.

Il viaggio nella penisola iberica prosegue poi nei Paesi Baschi, ma con una creatura insolita e nata dalla voluta alterità rispetto al contesto: il Museo Guggenheim di Bilbao5

Ciol fotografa la struttura secondo gli stessi parametri visivi su cui ha basato la sua interpretazione della cattedrale di Siviglia o delle vertiginose trame moresche di Cordoba: non dà conto di un’architettura, ma elabora un paesaggio. Un lembo di natura fitto di scisti, depressioni e crode cangianti, su cui lo sguardo si muove vigile, inquieto, con quella capacità che è della visione laterale – limis oculis – di cogliere asperità e riflessi altrimenti destinati a sfuggire alla centrata pienezza di un’osservazione propriamente statica. Le masse vengono catturate in angolazioni d’un libero fluire che ne costituisce la più autentica ragione progettuale, ma che al contempo le proietta in una dimensione di musicali, astratte collisioni. Le lastre di titanio del rivestimento divengono elementi di una costruzione ritmica. Pura estensione della materia nella luce. Volume addensato nella compressione temporale di uno scatto dell’otturatore, espresso nella solida ambiguità del proprio status di energia sopita, pronta tuttavia – possiamo immaginare – a innescare una nuova torsione. Sopra al mobile cumulo in cui la struttura pare collassare, in alcuni momenti il cielo smarrisce i propri connotati atmosferici: azzera la sua dimensione naturale in una luce metafisica o sprofonda in un silenzio oscuro, preparando la via all’avanzare di giganteschi aracnidi dalle lunghe zampe, concepibili solo nel contesto d’una simile alterazione del visibile.

L’architettura fa propria la logica della spettacolarità che indirizza le sorti del sistema artistico contemporaneo; ma il guscio del museo-cenotafio – di quello che «non è più il luogo dello sguardo», della contemplazione posata sulla sacrale ostensione del dipinto o della scultura, ma è divenuto «il luogo dell’inversione dello la chiave di una circolarità della Natura e della Storia, dell’azione e del pensiero, dello spazio e del tempo».

5 Nelle righe che seguono, sono inglobate ampie parti del testo Fluide architetture, che chi scrive redasse per la mostra di Elio Ciol alla Galleria San Maurizio di Venezia, nel 2008.

6 J. CLAIR, La crisi dei musei La globalizzazione della cultura, Milano, Skira, 2008 [2007], p. 102.

13

sguardo»6, della stupefacente e irrelata rifrazione dello spazio espositivo e delle sue dinamiche interne –viene ricondotto da Elio Ciol ai termini di una visione discreta, priva di enfasi.

L’occhio del fotografo, in altri casi rispettoso del contesto e del suo ordine d’uso, avverte il prevalere della forma sulla funzione. L’edificio, contenitore di oggetti d’arte per accidente – specie di recipiente elastico che, mentre lascia libero lo spazio di espandersi in anarchico volume, tende a oscurare formalmente ciò che sta nel suo ventre, ovvero le opere –, si propone quale autonoma presenza geologica. Immane e irriducibile a una percezione unitaria, creatura ciclopica e proteiforme, è come se fosse diga e montagna assieme.

Poi ci sono le nuvole.

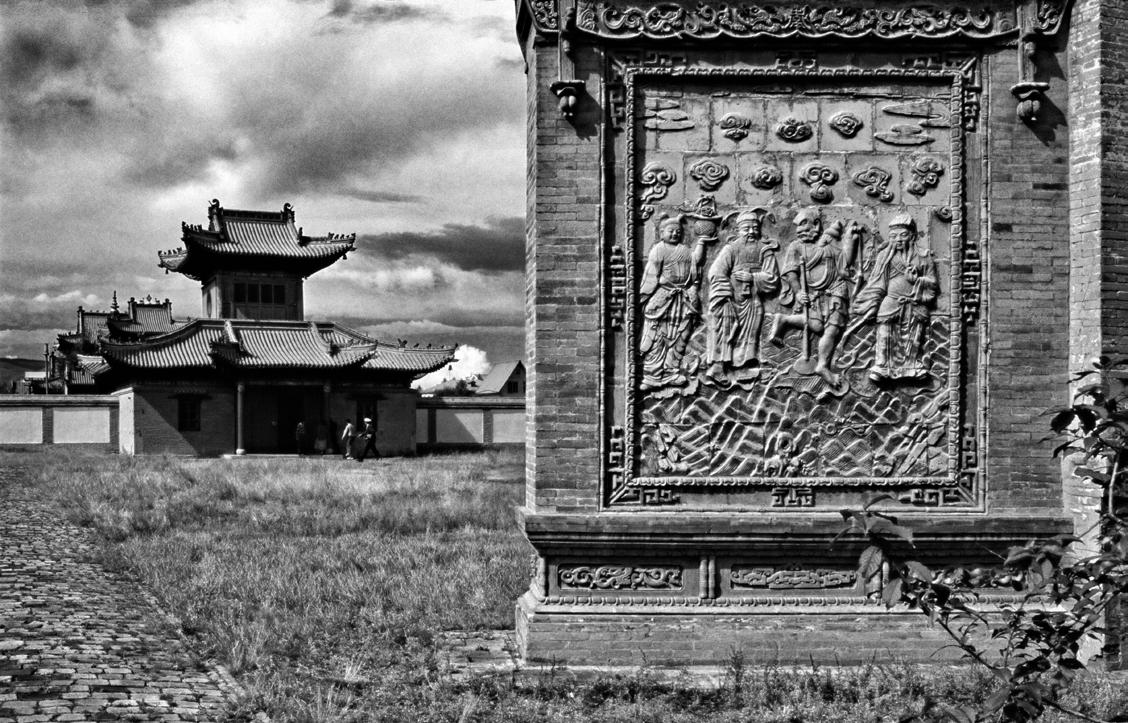

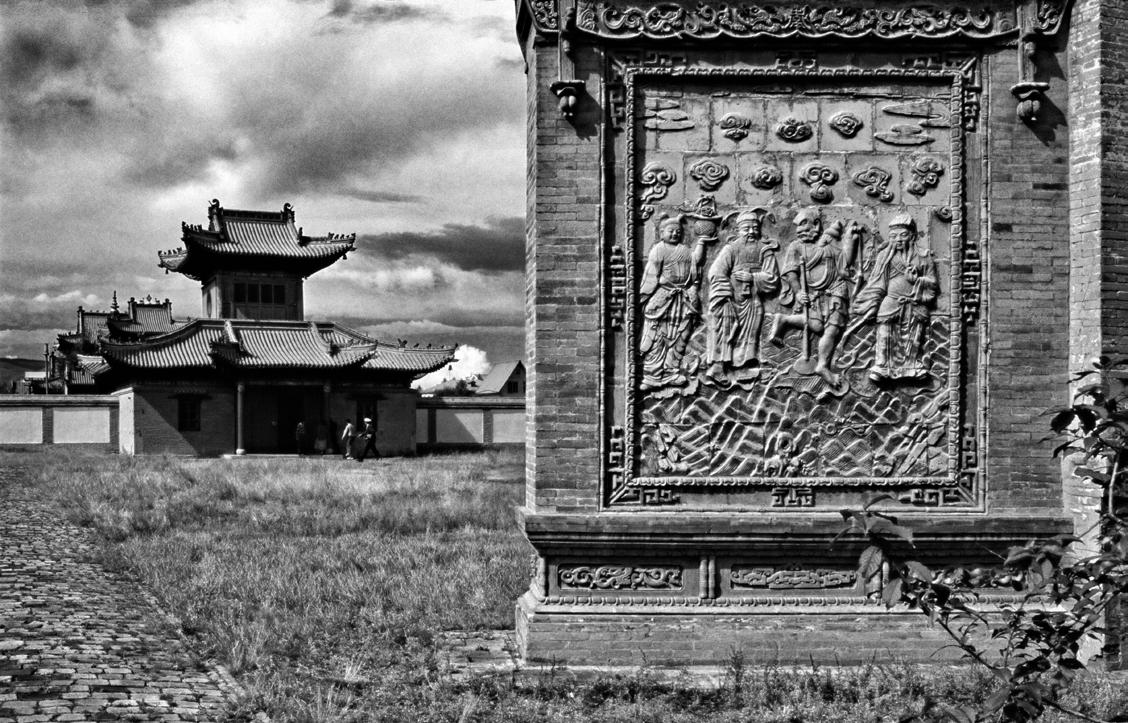

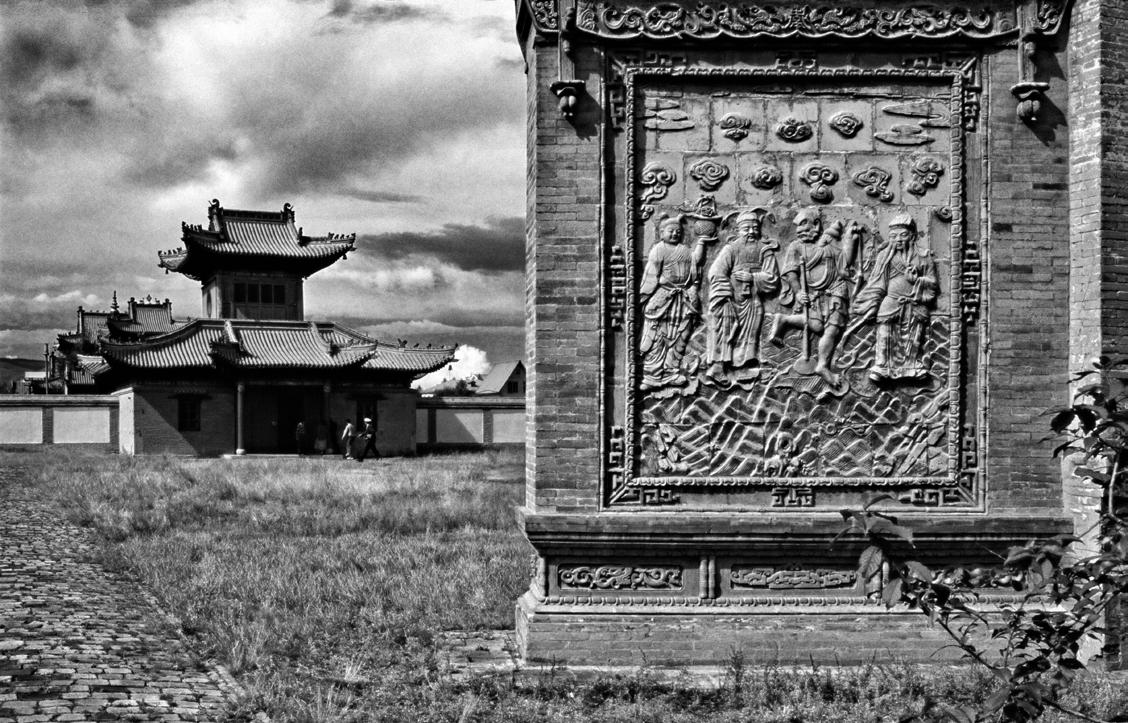

Quelle della Mongolia a Karakorum, ad esempio, che nelle fotografie del 1987 sovrastano templi, bocche di gronda e mura di cinta, ritmate da torri-padiglione quadrangolari, che sembrano cucire fra di loro con lunghe imbastiture terra e cielo.

Sbuca persino, fra le sterpaglie, un’imprevista tartaruga, docile monumento in pietra alla paziente attesa del farsi e disfarsi delle cose.

Ma sopra a tutto rimangono quei bioccoli di vapore, in grado di conferire a ogni panorama la sospesa modalità della visione. Neppure se un’anima derelitta ci passa sotto a cavalcioni d’un mulo, le nubi accettano di farsi ricondurre alla semplice registrazione atmosferica di un transitorio momento d’esistere. Stanno lì, ierofaniche, a sottintendere quanto di mistico e rituale può essere rimasto, come gromma, in uno sbrecciato calderone di bronzo; dialogano con i simbolici inquilini di un tempio – digrignanti protomi dei cornicioni – in un equilibrio di orizzontale condivisione della trascendenza7

Ed anche il monastero di Ulan Bator beccheggia sotto un cielo corrusco; i suoi tetti a pagoda sembrano una flotta di scafi incurvati, consapevoli della traversata che si prepara loro fra le nuvole- flutti, con l’equipaggio di piccoli idoli in coperta a scrutare fiducioso segnali del placarsi della tempesta, all’orizzonte.

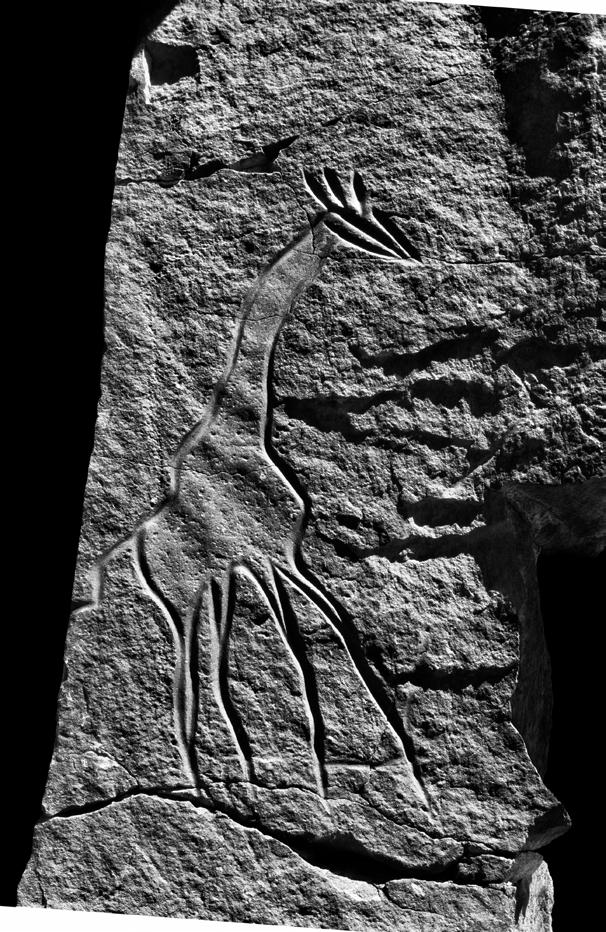

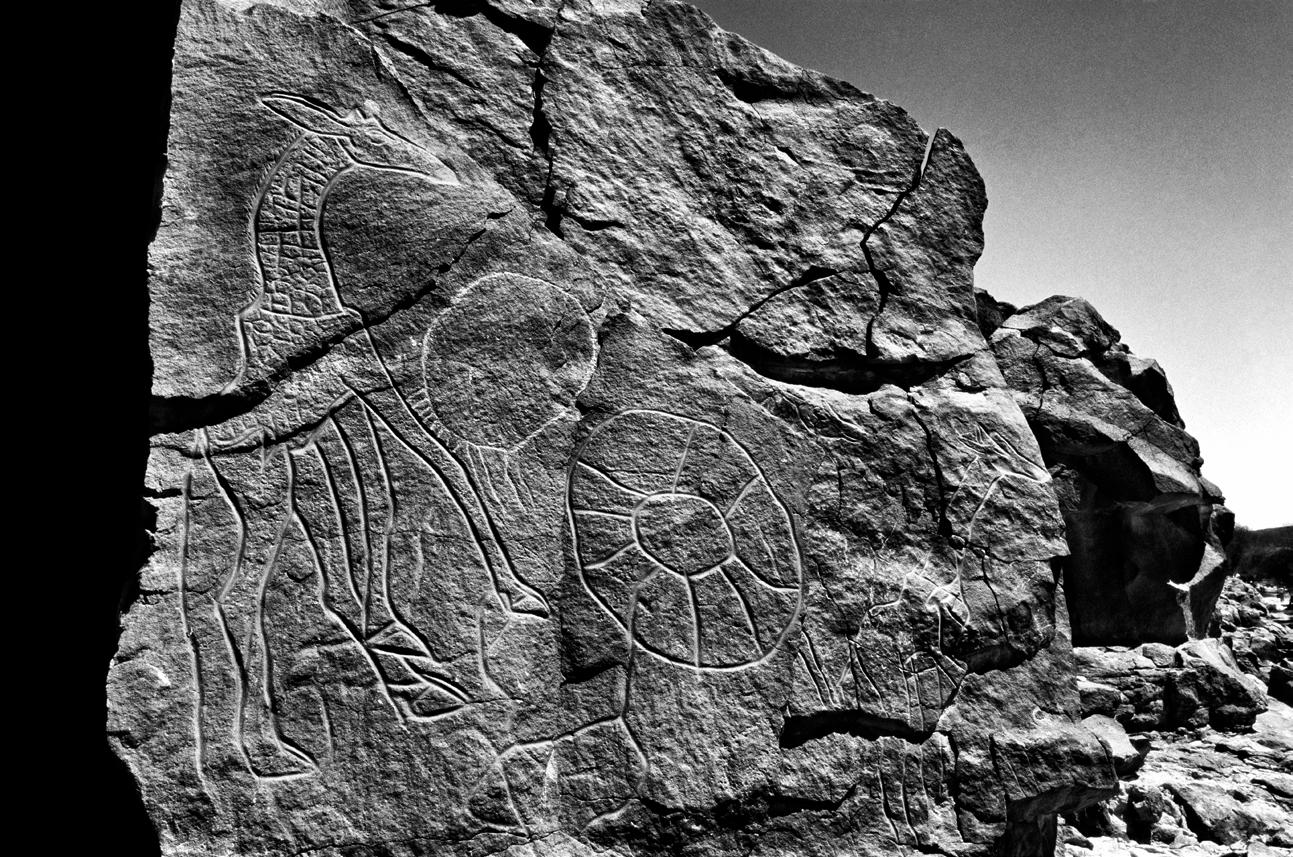

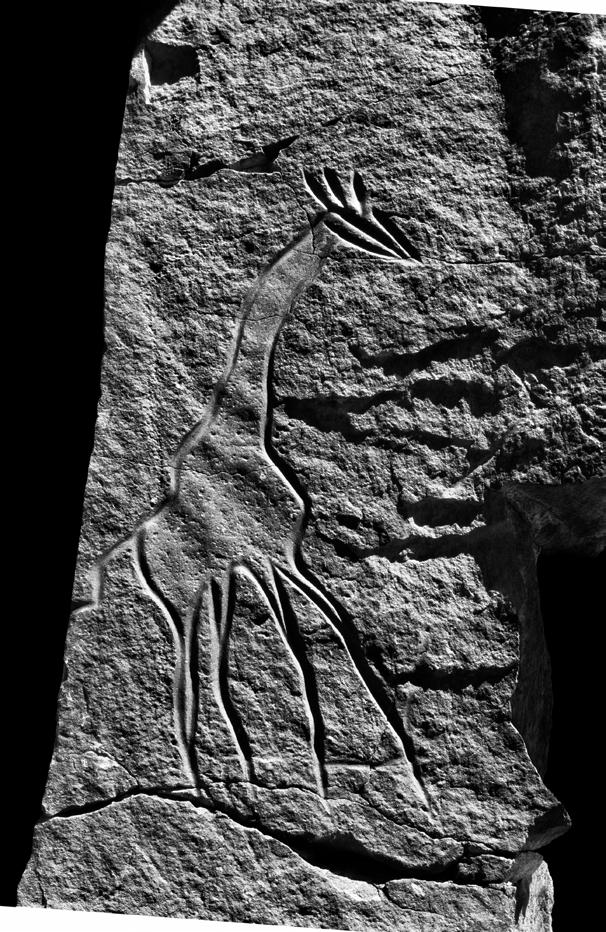

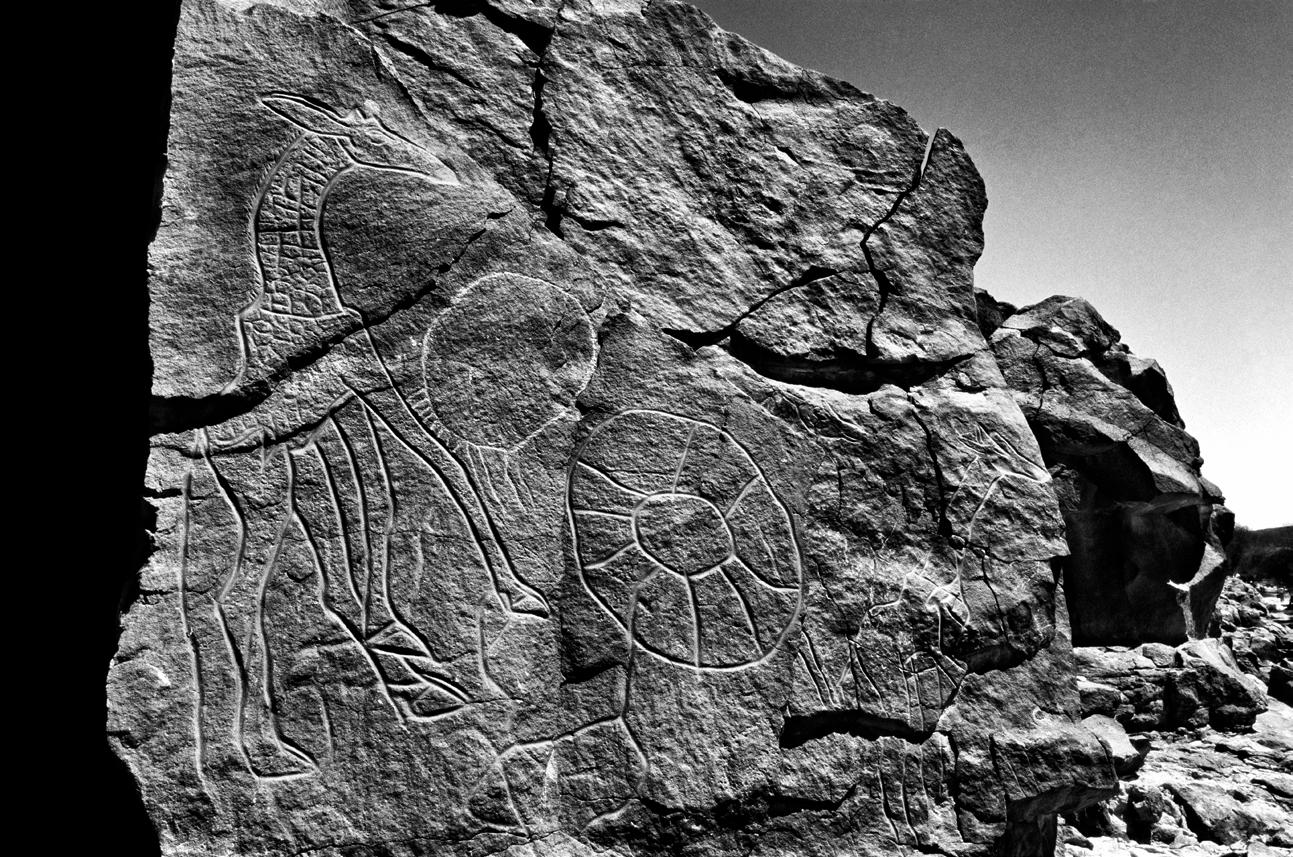

In alcuni casi, il viaggio sotto cieli striati di bianco conduce il fotografo ancora più distante dai centri urbani. In Armenia, ad esempio, a percorrere gli allineamenti di Zorats Karer, dove le nubi amplificano la prospettiva delle infilate di megaliti: gigantesche selci preistoriche che ritagliano la pianura da millenni e lasciano ora, docili, che il fotografo sancisca nelle sue inquadrature il controllo visivo che esse esercitano sul paesaggio. Oppure a Wadi Mathendush, in Libia, dove i graffiti disegnano sulla roccia le sagome dei progenitori di rinoceronti, elefanti e coccodrilli: i grandi animali che erano padroni del territorio, prima del deserto, e che le popolazioni del tempo evocarono con rispetto in immagini ingenue quanto icastiche. Che poi sulle pareti del fiume fossile compaiano anche dei bovini e una giraffa, che lo scalpello ha scavato nella pietra con la spigolosa immediatezza di una xilografia espressionista, ha a che vedere con finalità propiziatorie per la loro cattura.

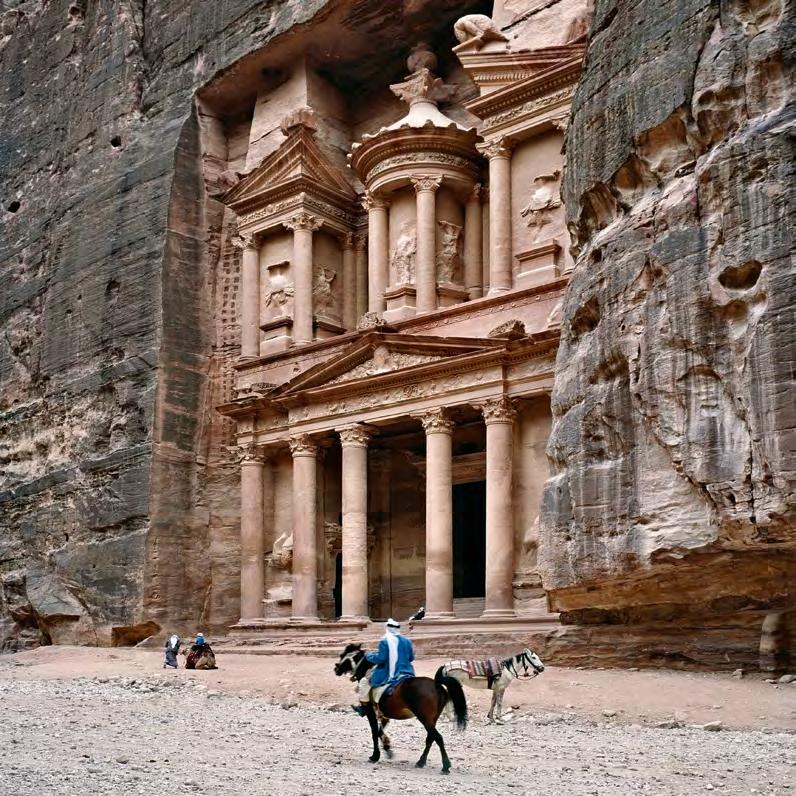

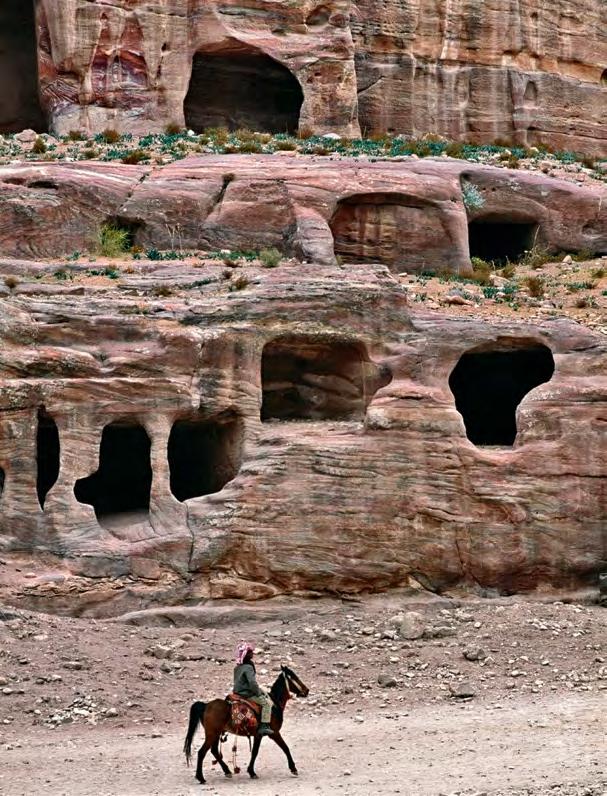

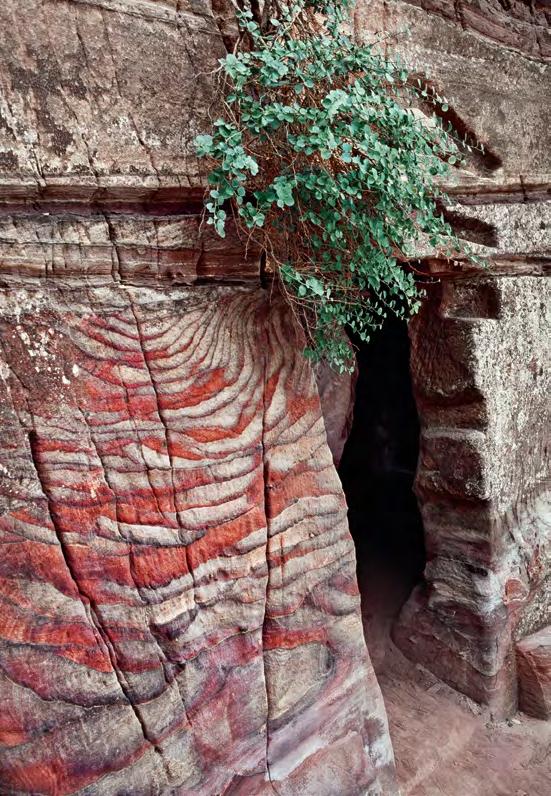

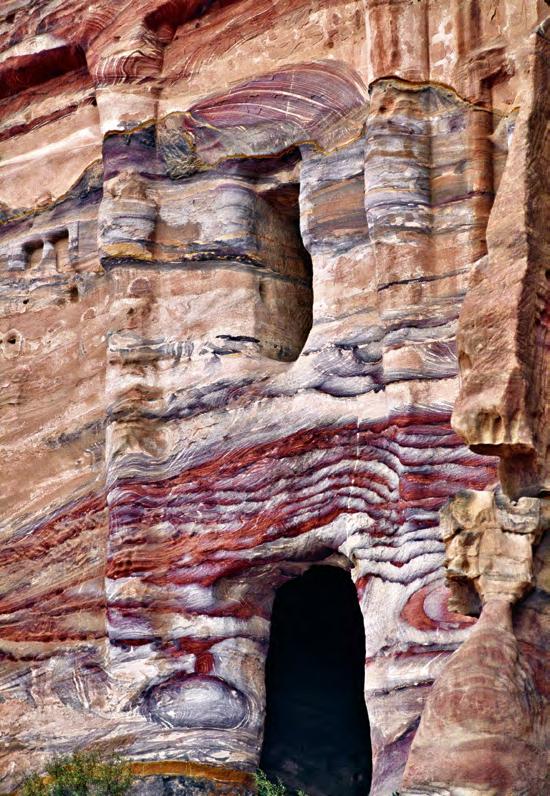

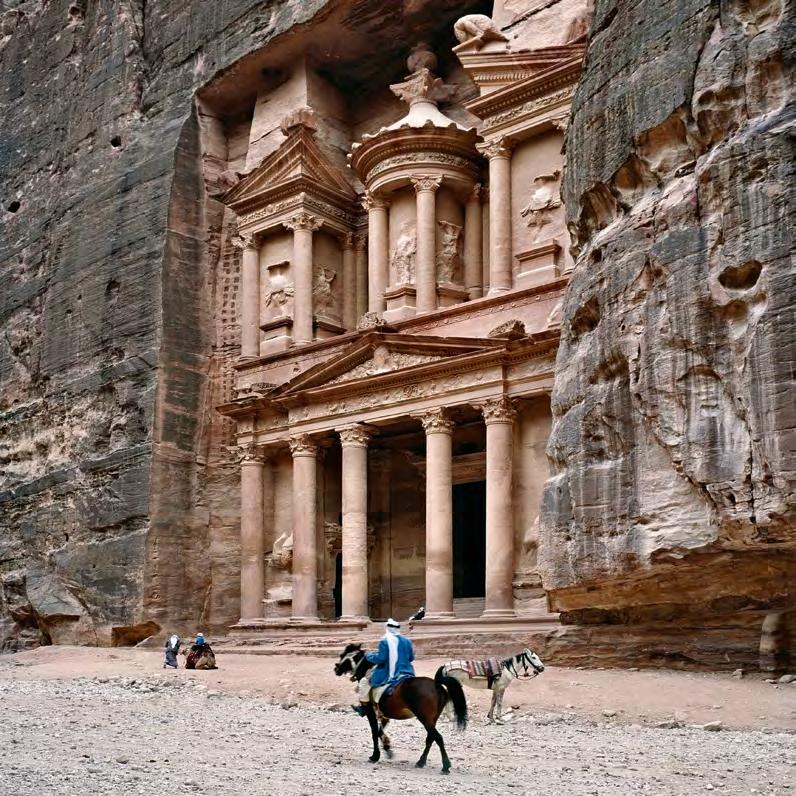

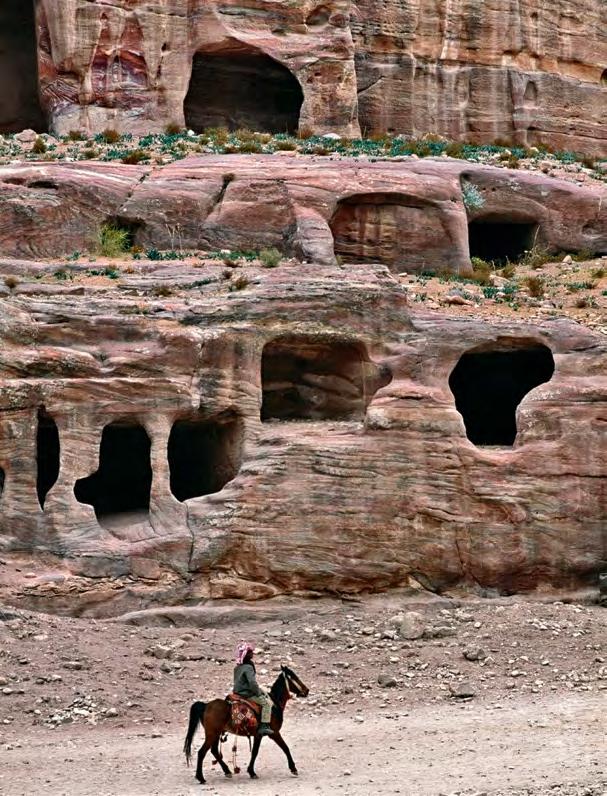

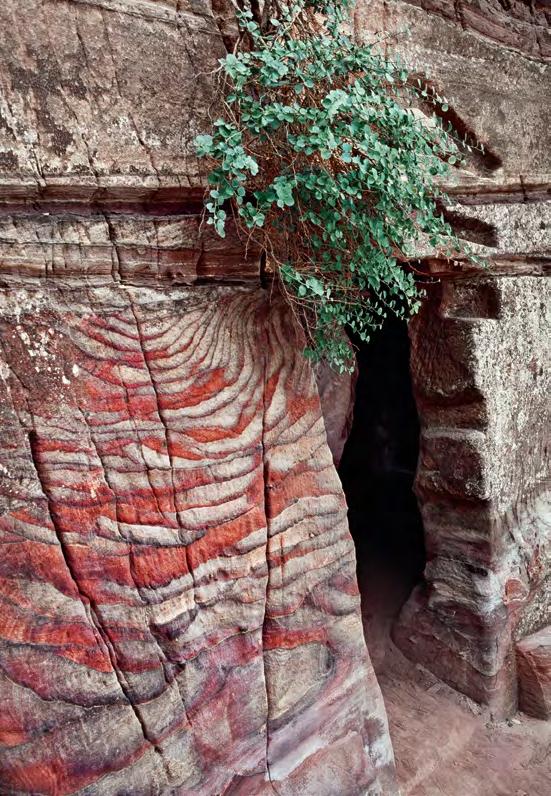

La materia si fa invece pittura a Petra, dove le increspature geologiche si offrono allo sguardo come un

7 Cfr. H. DAMISCH, Teoria della nuvola, Genova, Costa & Nolan, 1984 [1972], pp. 67-68: «[…] I segni del sacro non fanno eccezione rispetto a qualsiasi altro segno: essi appartengono a degli insiemi, a dei sistemi storicamente costituiti, in cui il rapporto laterale da segno a segno prevale sulla relazione diretta, verticale, tra significante e significato, che dovrebbe definire il simbolo. […] La nuvola non ha significato che le sia assegnabile per se stessa; non ha altro valore che quello che le viene dalle relazioni consecutive, oppositive e sostitutive che essa intrattiene con gli altri elementi del sistema».

14

tessuto vivente, le cui fibre dipingono un reticolo surrealmente elastico di rossi e di aranci; su di esso la vegetazione si installa come in una carne silicea, screziata e pulsante.

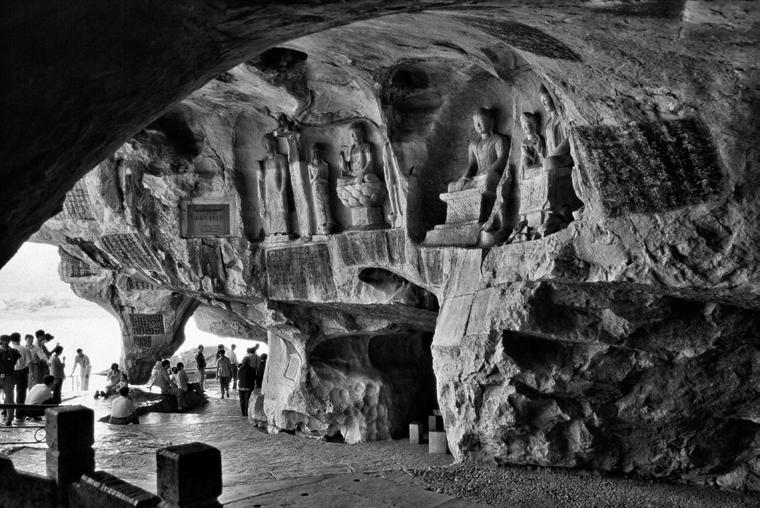

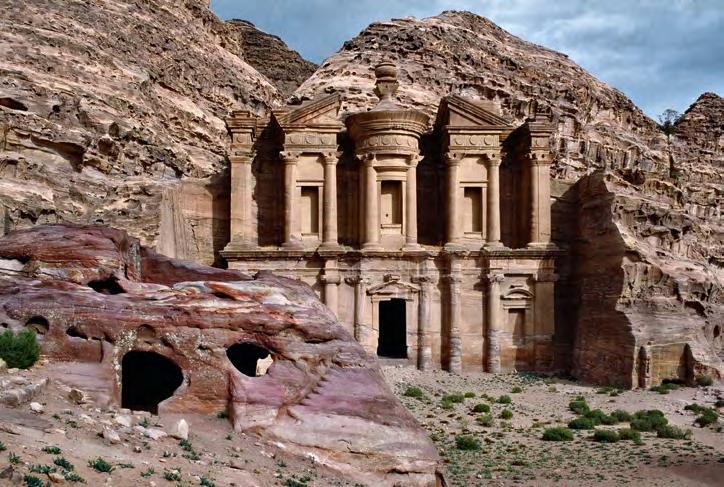

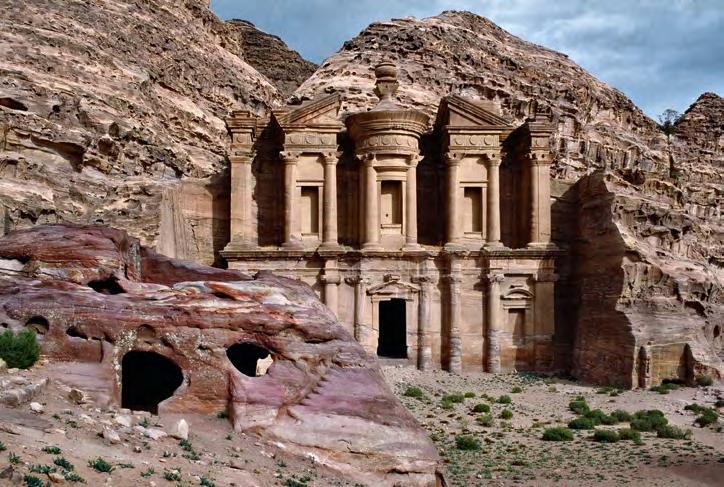

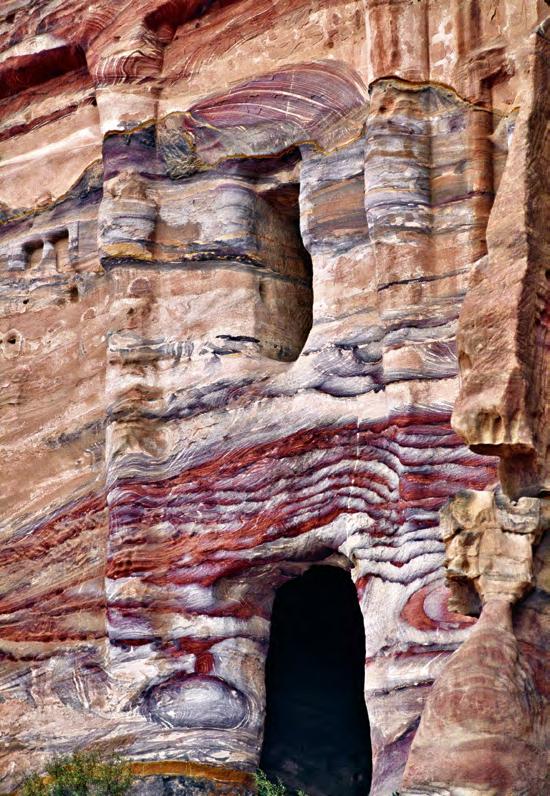

Ma le rocce rosate di Petra diventano a loro volta architettura, senza soluzione di continuità rispetto al paesaggio. I templi, con i loro sistemi di colonne, timpani e trabeazioni, sembrano le vestigia di una città che la natura ha riassorbito, inglobandola nel profilo delle colline; pare che un sipario di pietra stia per calare definitivamente sulle facciate monumentali, che invece in quella pietra sono state scavate, simulando l’architettura come in un colossale rilievo scultoreo.

Ci sono fotografie in cui il processo di trasformazione viene smascherato: la materia rocciosa, modellata in impasti geologici che immaginiamo profumare di pasticceria, tanto appaiono cremosi, mostra di essere sostanza dell’edificio; i fusti delle colonne confessano di essere parte della montagna e di non sostenere nient’altro che il fantasma di un architrave. Ma rimane, visivamente, il dubbio che la metamorfosi possa funzionare al contrario: che quel colonnato stia perdendo i suoi connotati originari di costruzione, risucchiato sotto i nostri occhi dall’energia della natura, che insidia e va ormai assimilando al proprio corpo il volume dei capitelli e il profilo del portale.

Non è molto diversa, in fondo, la sorte di quelle città che, sgretolate da un declino storico, vengono fatte rivivere dall’archeologia trattenendole in bilico sul limite che separa il sito di interesse naturalistico e la testimonianza culturale. Città che nella loro suggestiva disgregazione tornano ad essere il paesaggio da cui erano sorte.

A Gerasa – per restare in Giordania – l’infilata di colonne del foro, nel suo insolito emiciclo, ha ancora la forza di legare i resti di età romana a un riverbero di identità urbana. Ma i capitelli corinzi del Tempio di Artemide si profilano all’orizzonte, fra i sassi e gli arbusti, sullo sfondo di un cielo azzurrissimo, come reali piante d’acanto radicate al suolo.

E poi, soprattutto, c’è Leptis Magna. La città di Settimio Severo, in Tripolitania, nella quale Ciol ha realizzato una delle sue più memorabili serie fotografiche. Il suo obbiettivo indugia sull’angolo di una strada che si perde nella luce, carezza il volume di una trabeazione solcata da un girale fiorito, che nel foro della più bella colonia romana d’Africa si dimena ancora – tra sbrecciati binari di ovoli e perline – quasi fosse una delle ciocche anguiformi della terribile Medusa che gli giace accanto. E, così facendo, la fotografia di Elio contraddice ancora una volta la prima istantaneità del suo divenire, proprio come certi luoghi in cui il tempo delle cose si blocca dilatandosi; lo sguardo è costretto allora a sostare nella contemplazione di una Leptis Magna in bianco e nero, quasi che le sue Gorgoni avessero fissato la dimensione estetica della propria trascorsa, vitale esistenza in una durevole sospensione.

«Quando le ombre si stampano, e avviano / la loro graduale esalazione del passato»8, sono le geometrie che pulsano sotto la pelle dell’immagine a raccordare il relitto a ciò che esso fu e al passo ulteriore di astrazione cui lo sguardo dell’artista ci conduce.

15

8 C. WRIGHT, Mezzogiorno [da China Trace, 1977], in Breve storia dell’ombra, Milano, Crocetti Editore, 2006, p. 93: «When shadows imprint, and start / their gradual exhalation of the past».

Dico di ciuffi di sterpaglia che replicano e avvolgono spire di pietra, o che – appena più probabili di quelli che abitano le rocce fratturate di Mantegna – segnano diagonali di resistenza della natura al levigato sigillo della storia. Dico di colonne sdraiate nel deserto ventre di un mercato: cilindri a lambire spigoli d’ottagono e convessità circolari, in intatti equilibri che paiono durare da sempre, come bottiglie in una natura morta di Morandi. «Parlo d’immobilità, del silenzio / […] Parlo di colore, di forma, del vuoto / che vigilano questi oggetti, e da cui sorgono»9

Forme, volumi, vuoti…

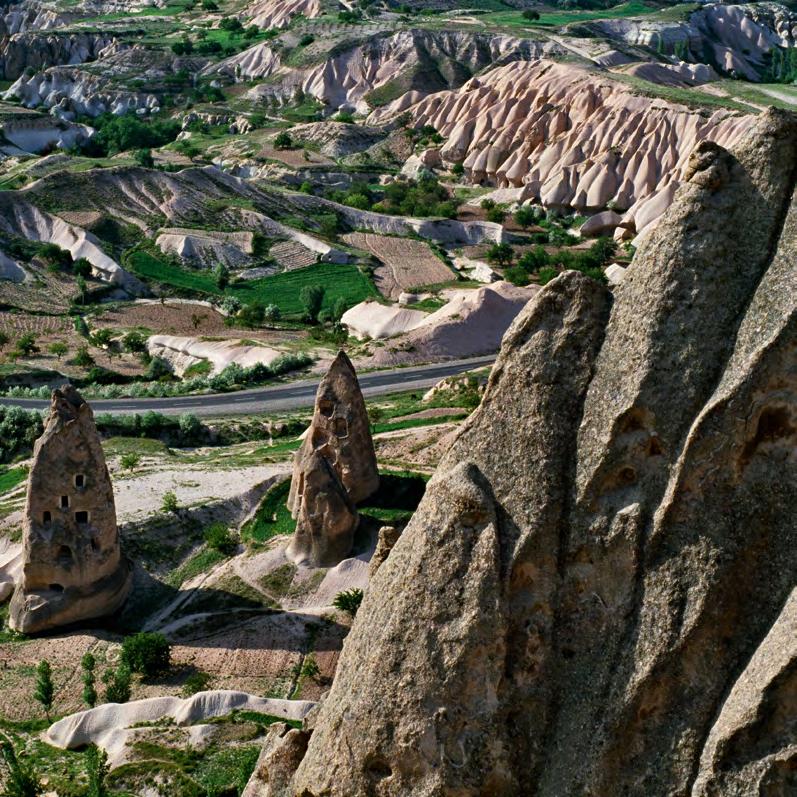

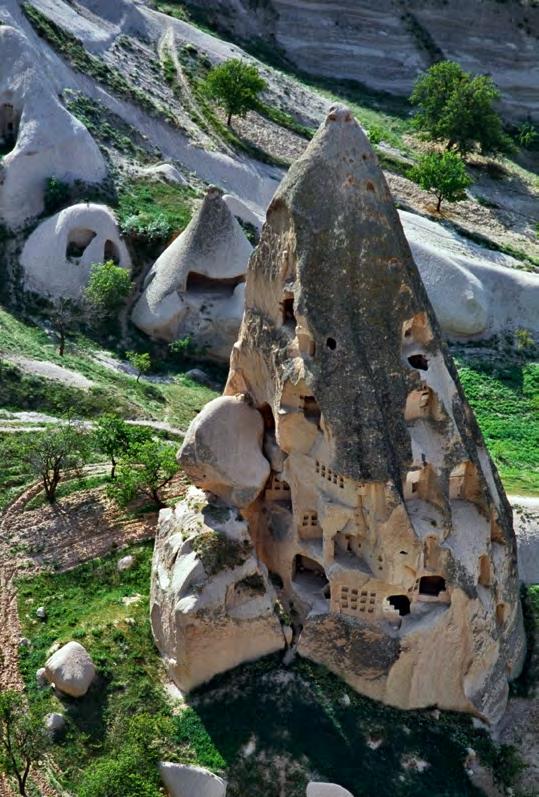

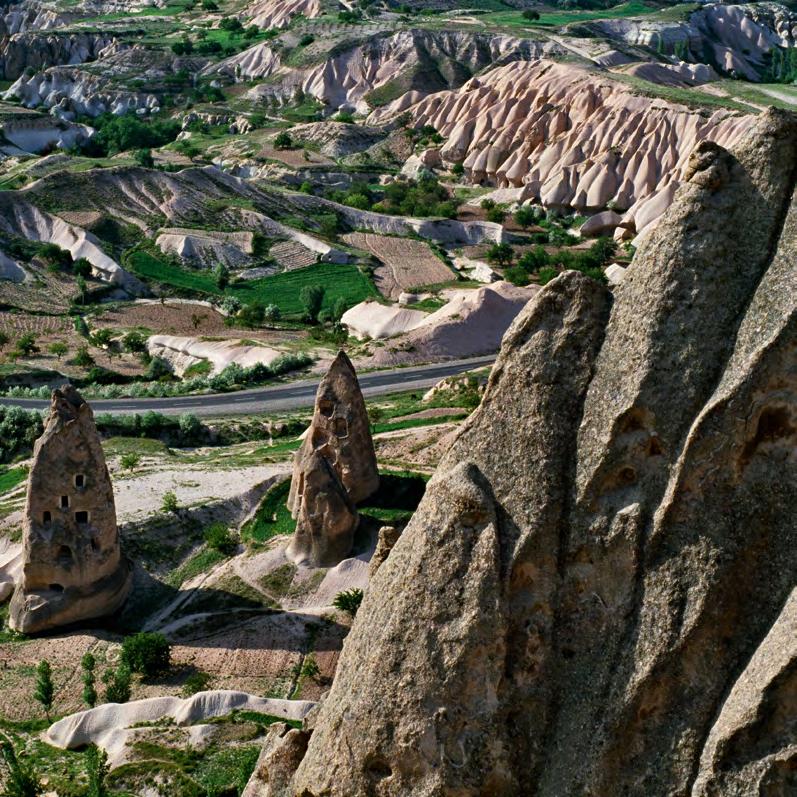

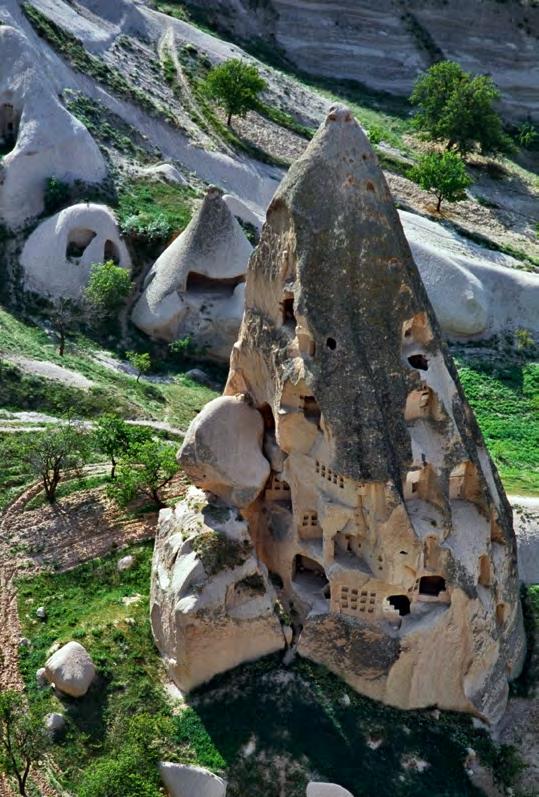

Sono tali anche i segni dell’uomo nel paesaggio: le abitazioni rupestri della Cappadocia (i “Camini delle fate”: tane umane che convivono con l’antitesi dell’idea di anfratto, sospese come sono su friabili pinnacoli, versione in positivo degli imbuti di Laudomia, sulle cui pendici «in ogni poro della pietra s’accalcano folle invisibili» di non nati10), o i terrazzamenti fotografati in Nepal.

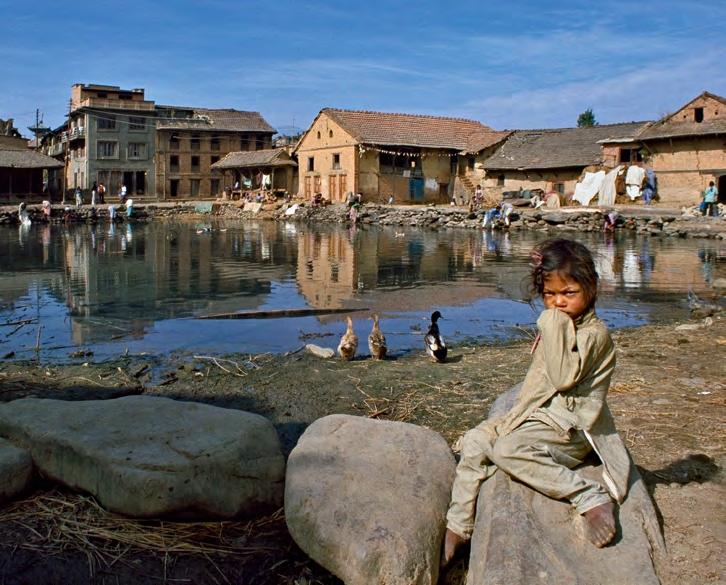

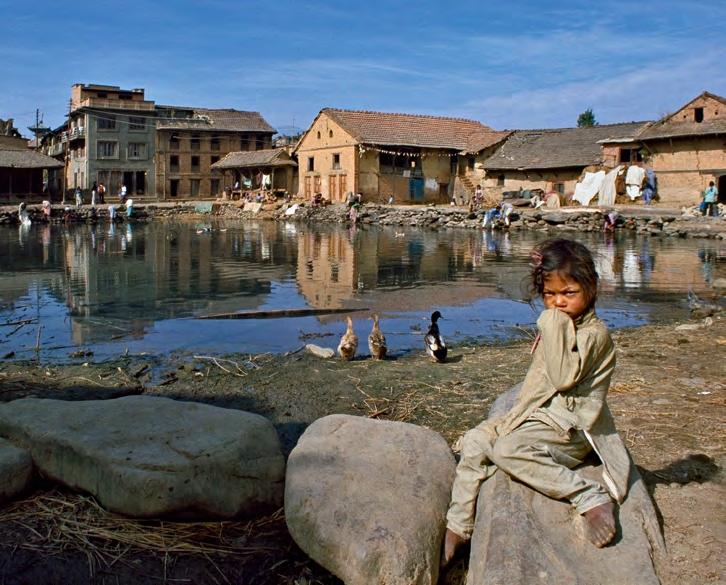

Qui la mano dell’uomo, nei secoli, ha saputo modellare con dolcezza i declivi d’altura tracciandovi digradanti screziature, portandoli ad assumere la grafica sinuosità di un verde arenile segnato dall’andare e venire delle acque. Ma in quel medesimo, altissimo angolo di mondo il fotografo – lo stesso che ha appena realizzato vedute degne di un giardino zen per la loro compostezza e rarefatta astrazione, immagini che potrebbero formalmente dialogare con le superfici scolpite da Tony Cragg – sa anche riassaporare l’odore della terra quotidianamente abitata, le ineleganze dell’esisterci sopra; e allora gli basta lo sguardo intenso di una bambina per catturare i segni della dignitosa fragilità dei suoi simili: la piccola è seduta su una roccia come una ninfa di Poussin, ma la pozza d’acqua sullo sfondo, intorno alla quale si svolge tutta l’umile e circolare vita del suo villaggio, ci accompagna nella consistenza melmosa di una faticata sopravvivenza, che nessuno scrupolo estetico induce l’artista a ignorare. Si tratta solo di innescare un differente processo di scandaglio del visibile, che accompagna l’emergere di proporzioni di luce in situazioni più dense di umanità.

Non c’è il tempo per condividere con chi è inquadrato un po’ di esistenza, ma per averne rispetto sì. Sono poche, in queste fotografie, le persone; Ciol le ritrae solo quando è certo di non scivolare nell’aneddotico, nell’esotismo addomesticato. Perché troppo spesso «là dietro, in fondo alla figura nel mirino, l’individuo inquadrato diventa un’immagine dell’individuo. Perde la sua personalità per acquistare quella che il fotografo intende assegnargli: mistico, esotico, pittoresco, selvaggio, ma soprattutto statico»11

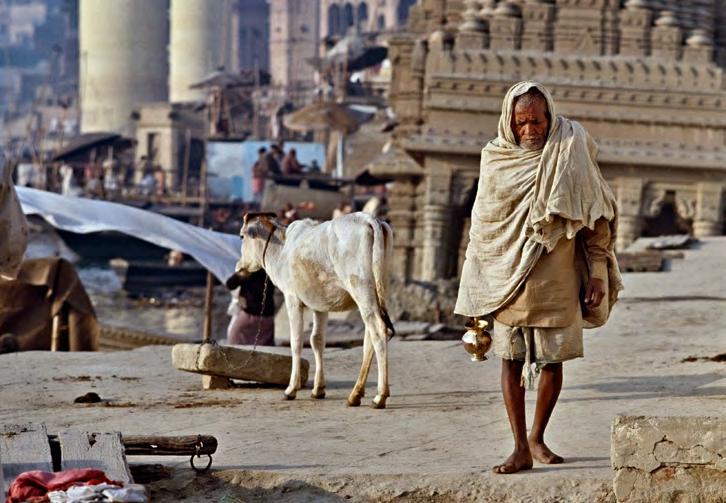

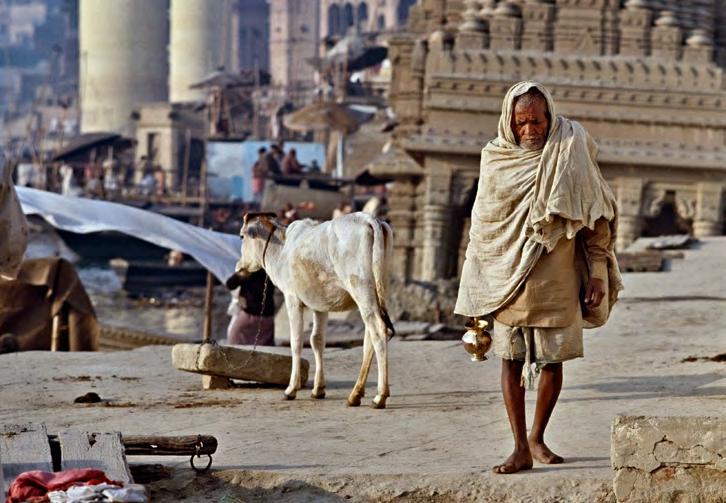

È il genere di pericolo che viene accuratamente evitato anche nelle fotografie scattate in India, a Varanasi, in cui l’artista procede escludendo sia l’imposizione di modelli sia un giudizio di valore12. Le figure dei devoti sono in equilibrio fra la geometria delle scalinate e il suo sciogliersi nel mobile riflesso delle acque

9 C. WRIGHT, Morandi [da China Trace, 1977], in Breve storia dell’ombra, cit., 2006, p. 81: «I’m talking about stillness, the hush / […] I’m talking about paint, about shape, about the void / These objects sentry for, and rise from». La parte di testo qui dedicata alle fotografie dell’antica città romana è in buona parte tratta da F. DELL’AGNESE, Leptis Magna, in E. CIOL, Leptis Magna, Venezia, Edizioni del Cavallino, 2007.

10 I. CALVINO, Le città invisibili, Milano, Mondadori, 2002 [1972], p. 143.

11 M. AIME, D. PAPOTTI, L’altro e l’altrove, Torino, Einaudi, 2012, p. 109. «Infatti, in molti casi i locali mettono in mostra aspetti della loro cultura per i turisti, estraniandoli dalla pratica quotidiana per trasformarli in pura rappresentazione, seppur fedele all’originale» (ivi, p. 108). Specificamente riferite a Varanasi, e alla cerimonia dei lumi galleggianti fatti scivolare sulle acque del

16

del Gange. Sono loro a tenere insieme il fiume e la città. E anche dal profondo della vita popolare l’occhio recupera assetti compositivi che sembrano calcolati a priori: il vecchio che avanza lentamente, di ritorno dalle abluzioni, calca esattamente l’ultima porzione di terreno che lo separa dal gradino e da noi – sottolineata da una serie di elementi orizzontali –, mentre l’incedere di qualche centimetro in senso opposto dell’animale sacro indirizza il nostro sguardo alla comunione di cenci e bacili d’ottone da cui l’uomo si è appena separato e dilata il tempo dell’immagine nella nostra percezione. E in quella trasposta durata, «incompreso aleggiava ovunque un significato»13.

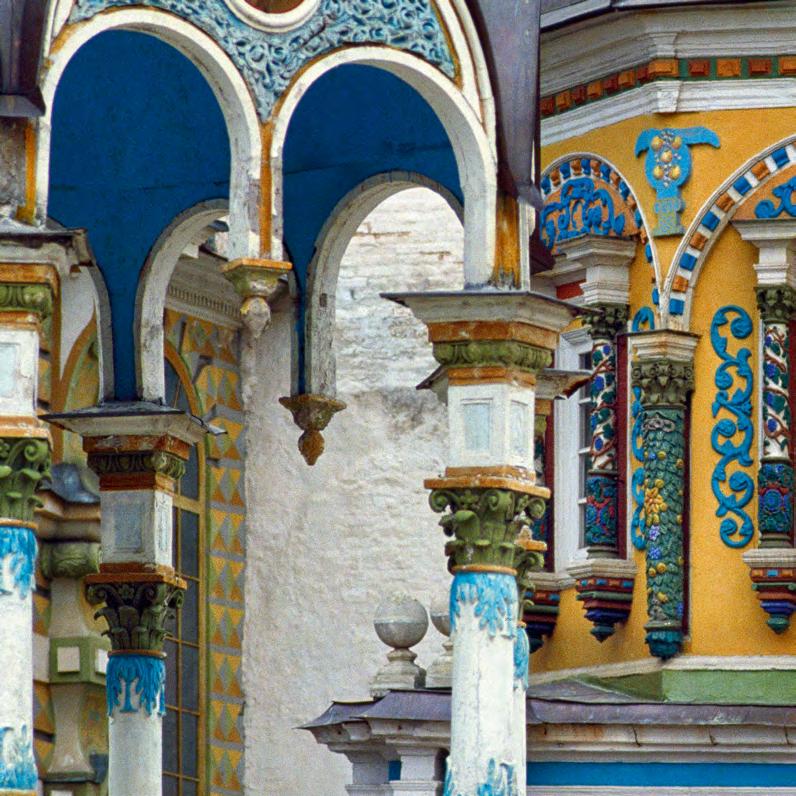

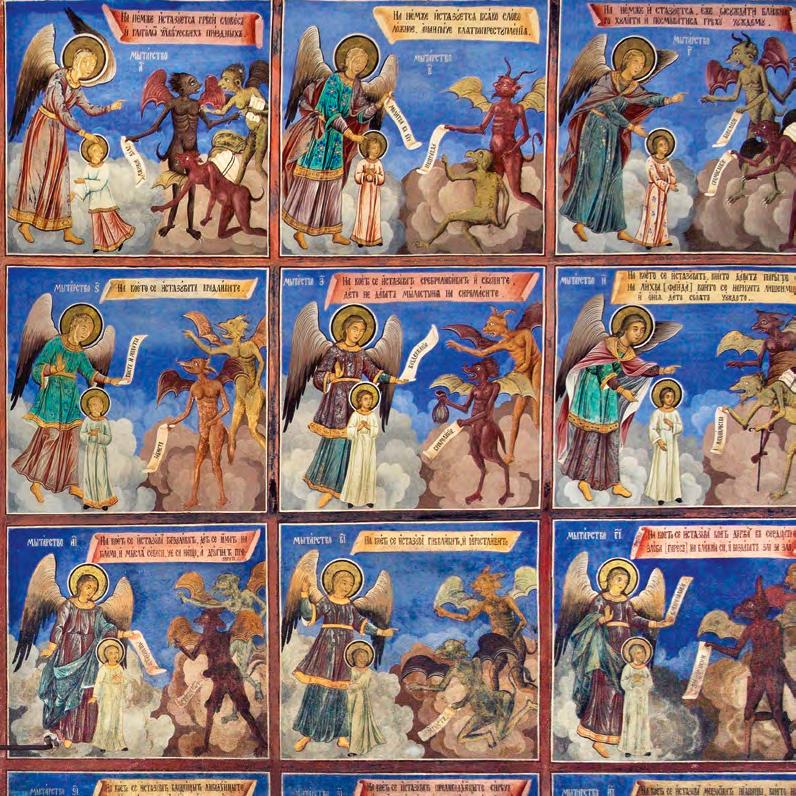

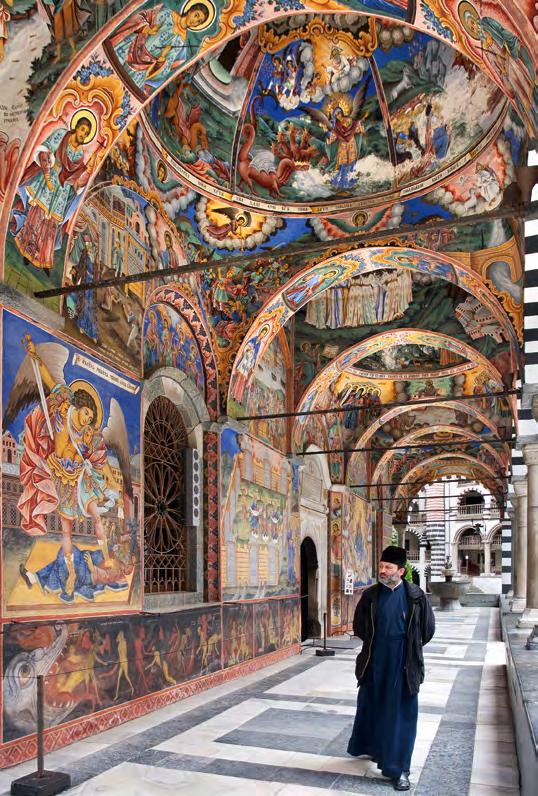

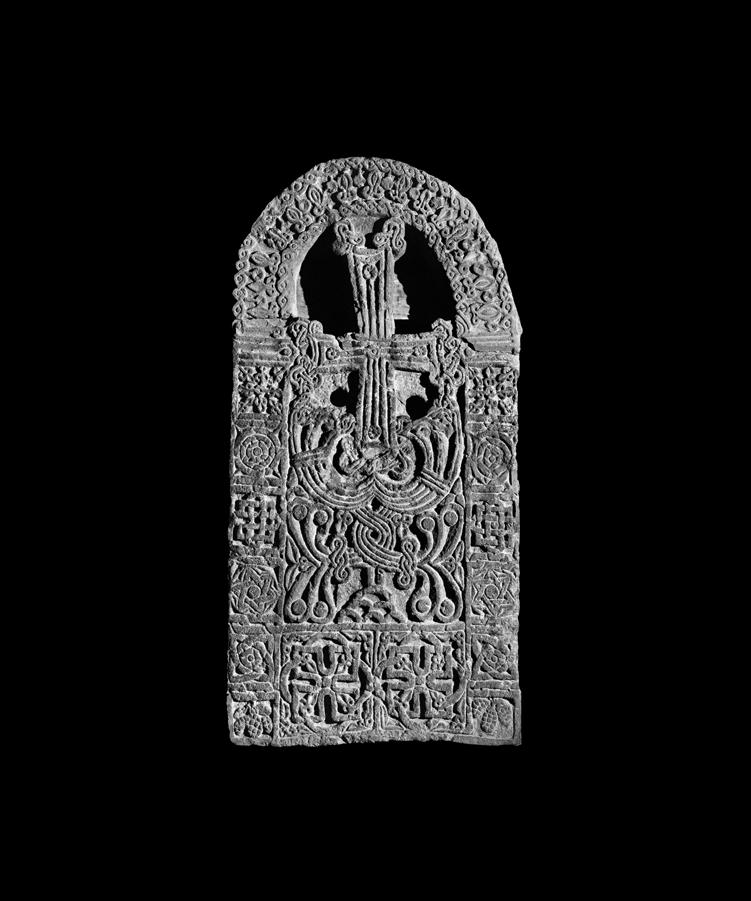

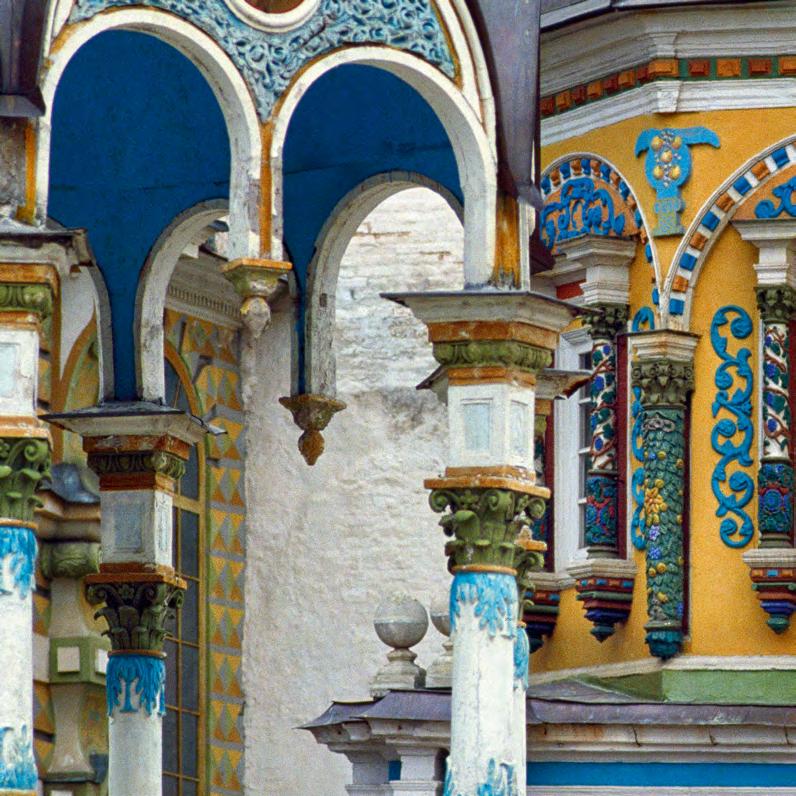

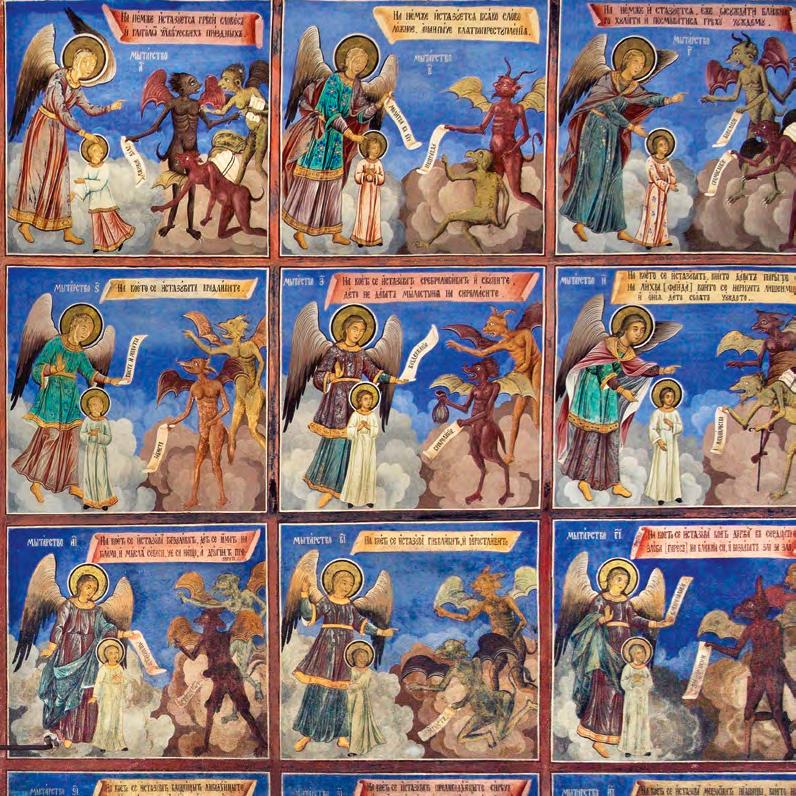

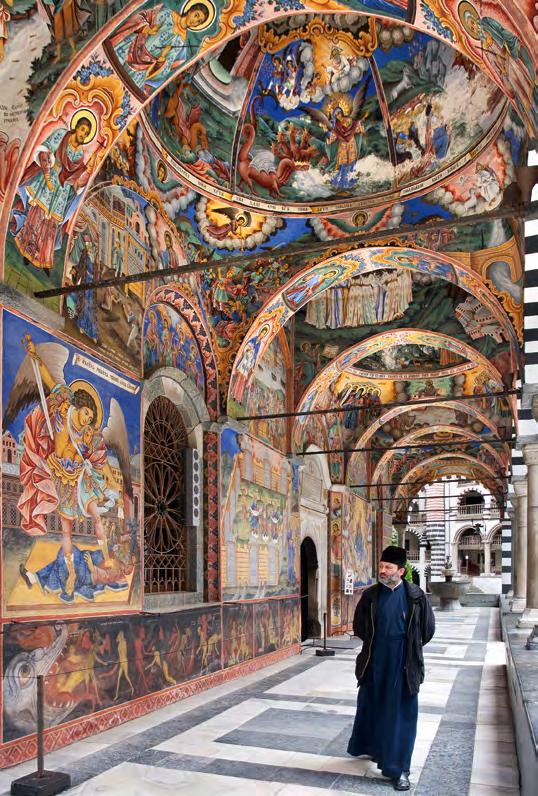

Altra, nelle sue liturgie e dunque nel modo di tradursi in spazi e immagini, la religiosità del Monastero di Rila in Bulgaria. Qui il vociare che pareva di sentir arrivare dal fiume nella foto di Varanasi si è completamente sopito; sui muri scorre – in forma di pittura – un film muto, i cui sgargianti fotogrammi si incasellano ordinati, ognuno con la propria didascalia.

Se nella ritualità induista a stordire era il moltiplicarsi di gesti e suoni individuali nel grande collettore urbano della quotidianità, nella cittadella ortodossa regna – altrettanto pervasiva – una geometrica proliferazione del segno architettonico (gli archi di portici e logge, la dicromia “optical” degli intradossi) fronteggiata dall’esuberanza narrativa e simbolica di una Bibbia parietale dipinta in rosa, oro e azzurro. Nel mezzo, a dispetto di qualche rado turista, il vuoto; e un silenzio increspato solamente dallo zampillo defilato di una fontana, dai passi di un monaco che viene verso di noi, in parallelo ai dannati degli affreschi spinti tra le fauci di Lucifero; in tanto repertorio di iconografia cristiana, egli incrocia quasi lo sguardo del bellicoso Arcangelo Michele sulla parete, ma a porre in discussione per un attimo la certezza del suo cammino interviene qualcosa fuori campo... Un piccolo accidente quotidiano, forse, al quale la fotografia allude in una meccanica da Blow up in cui l’invisibile ha il ruolo di determinare un possibile significato alternativo della scena.

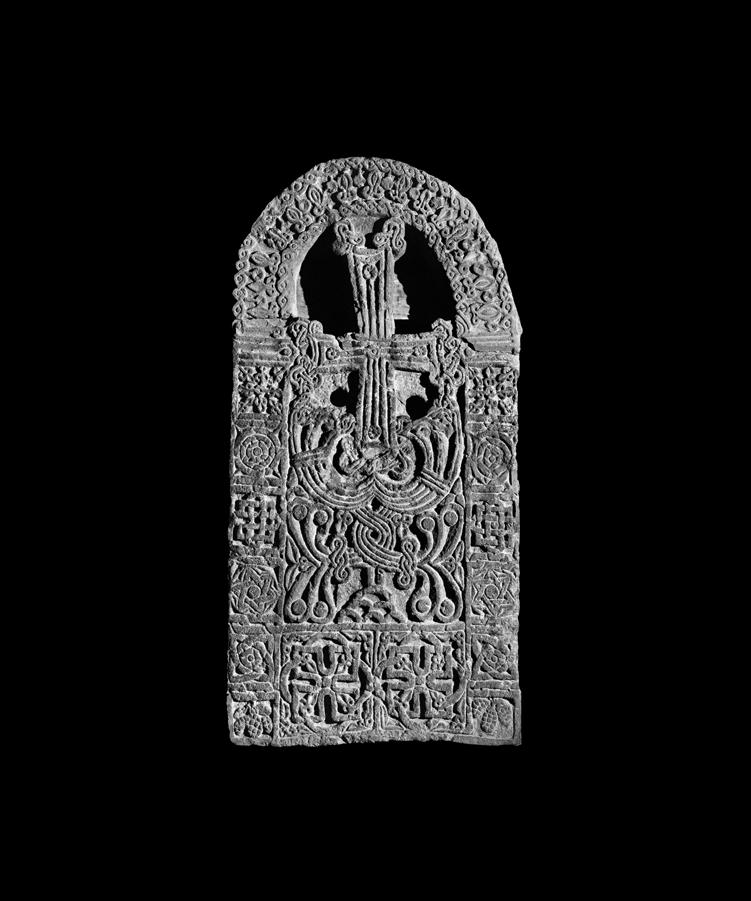

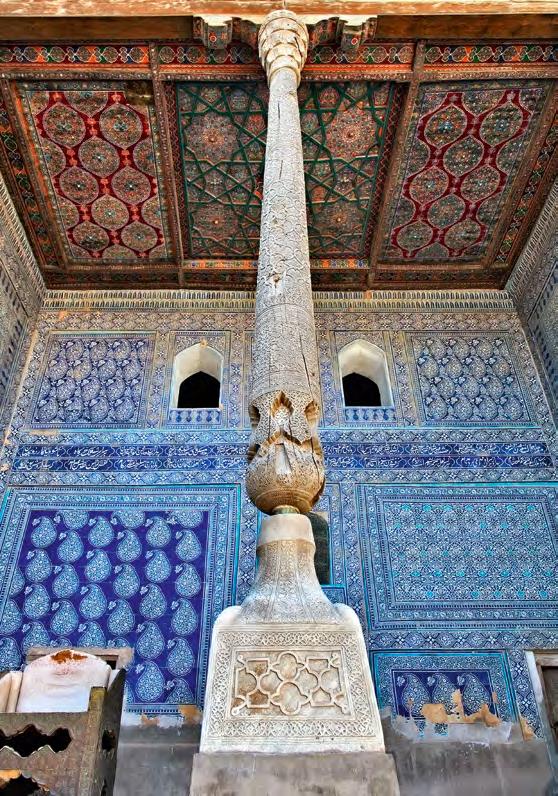

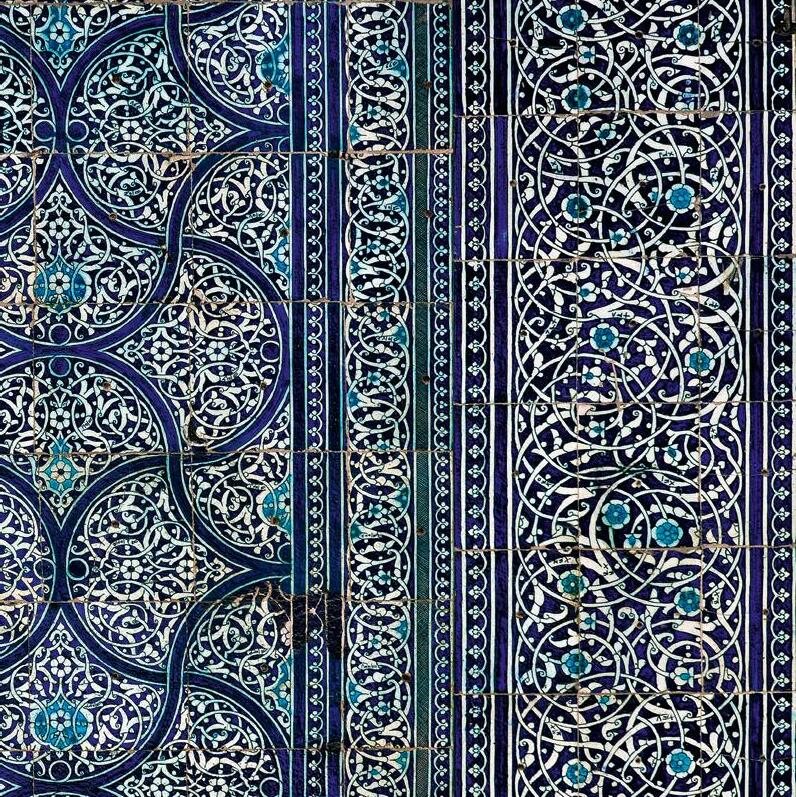

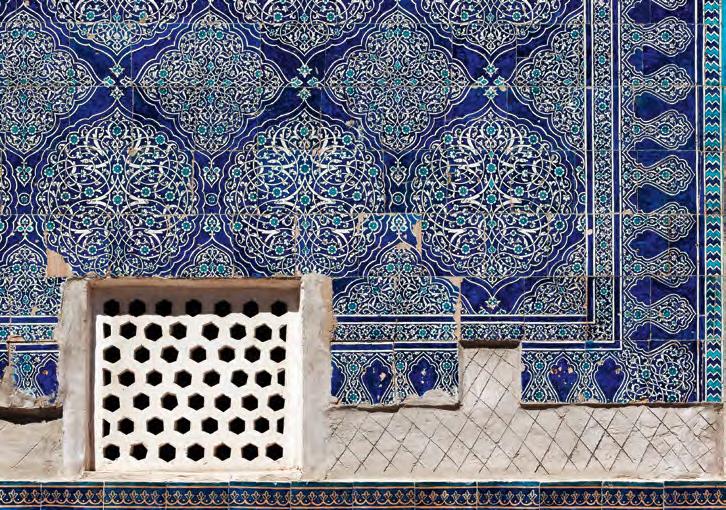

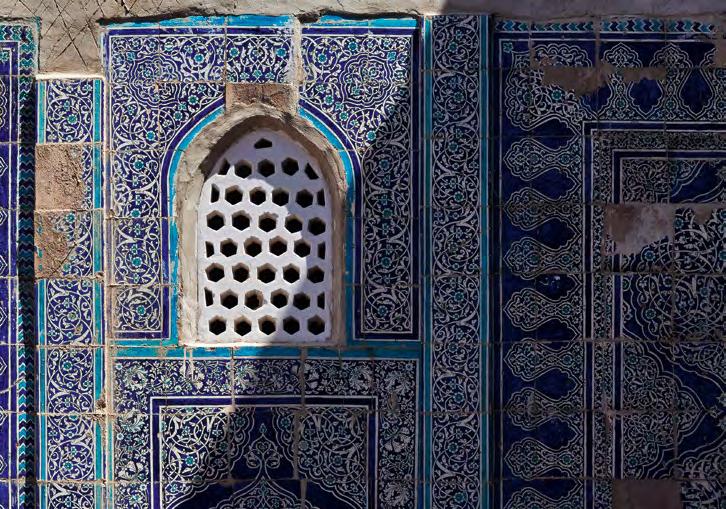

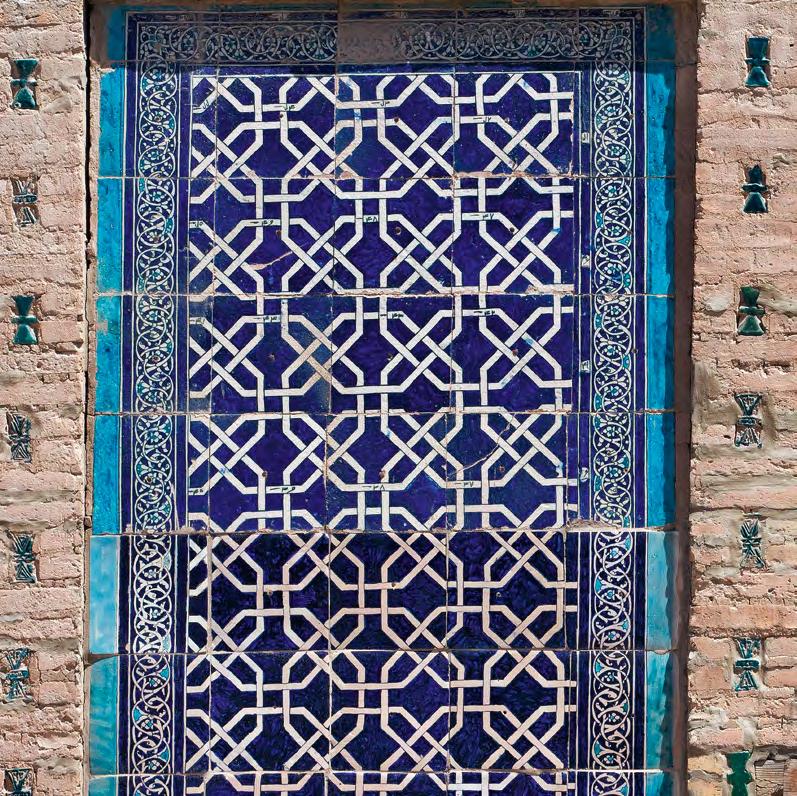

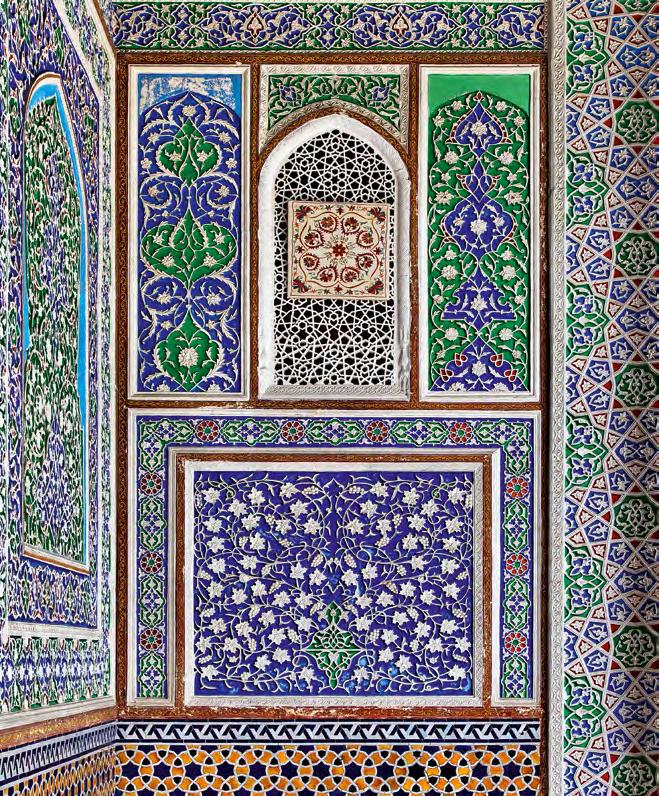

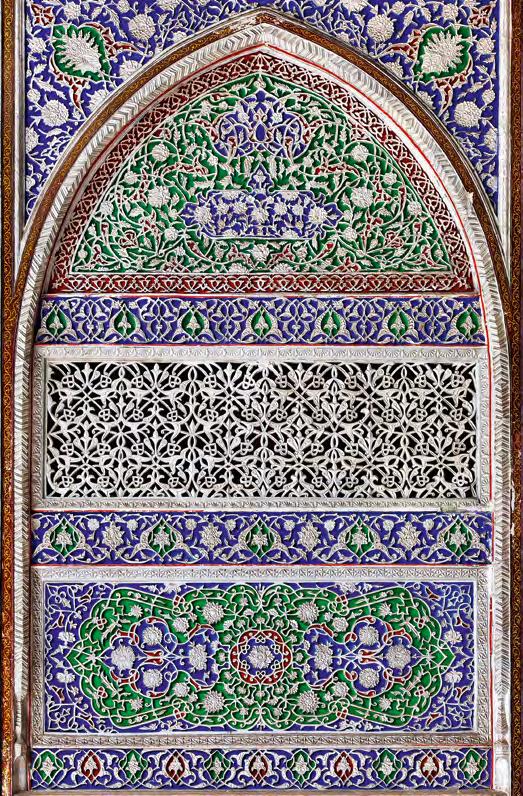

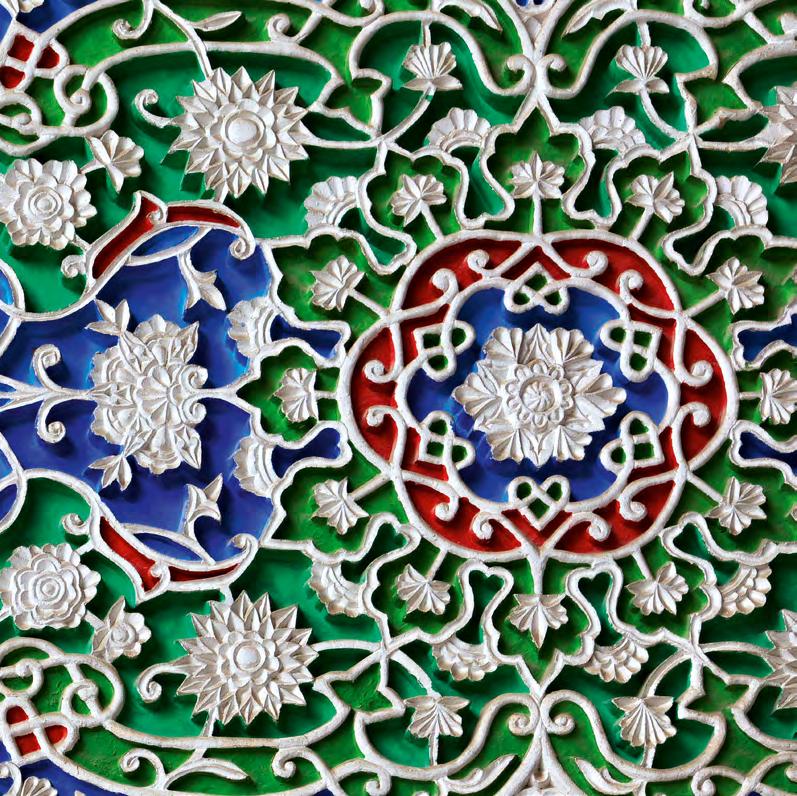

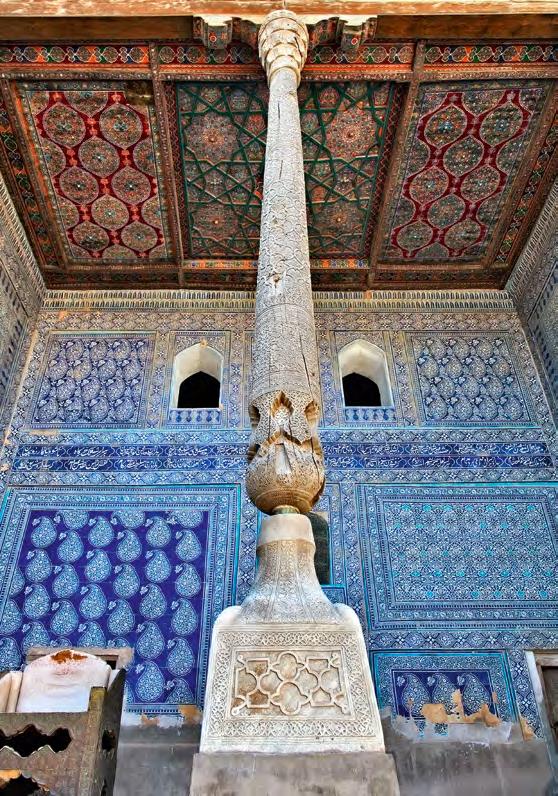

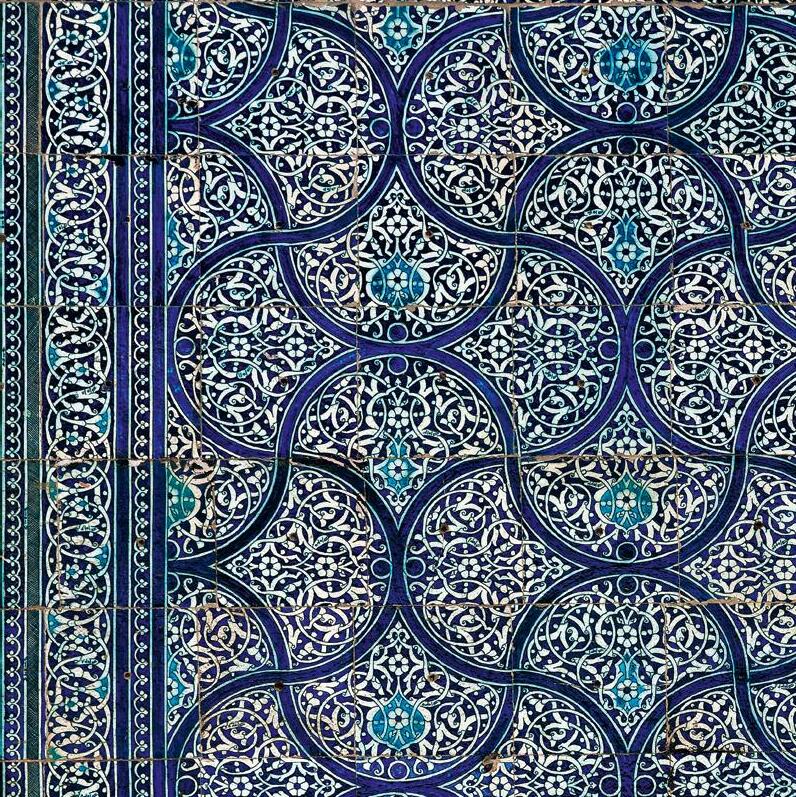

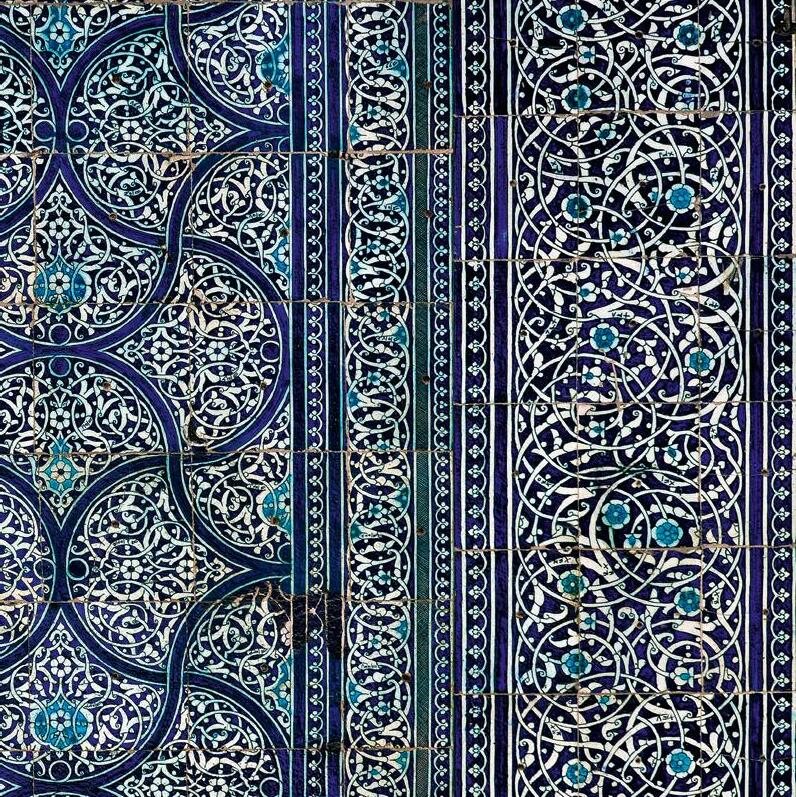

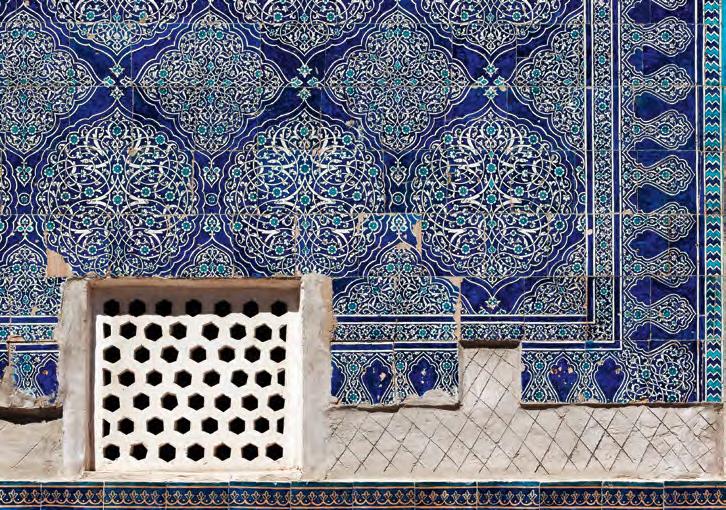

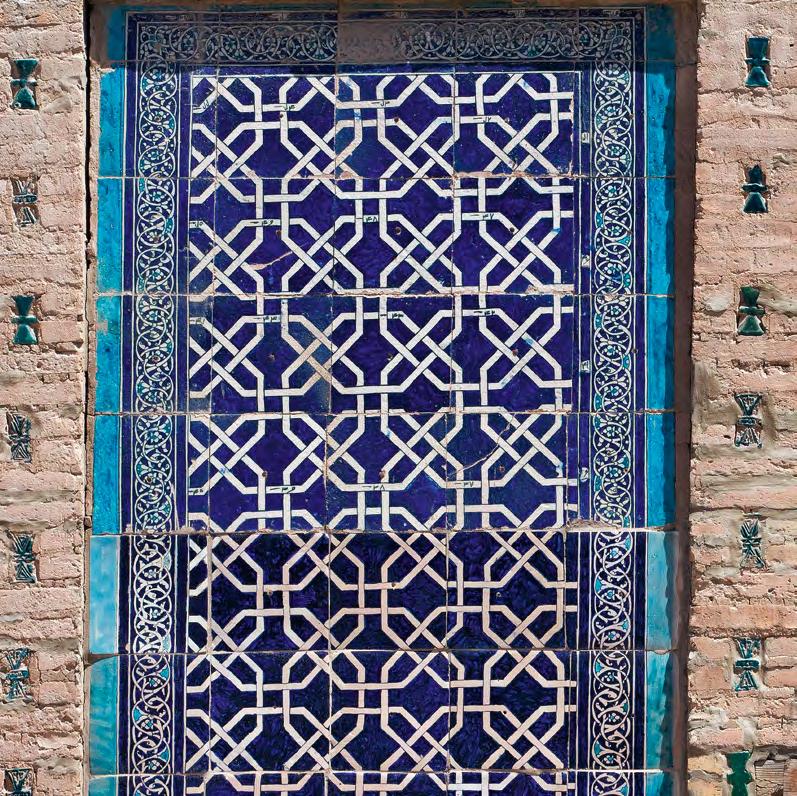

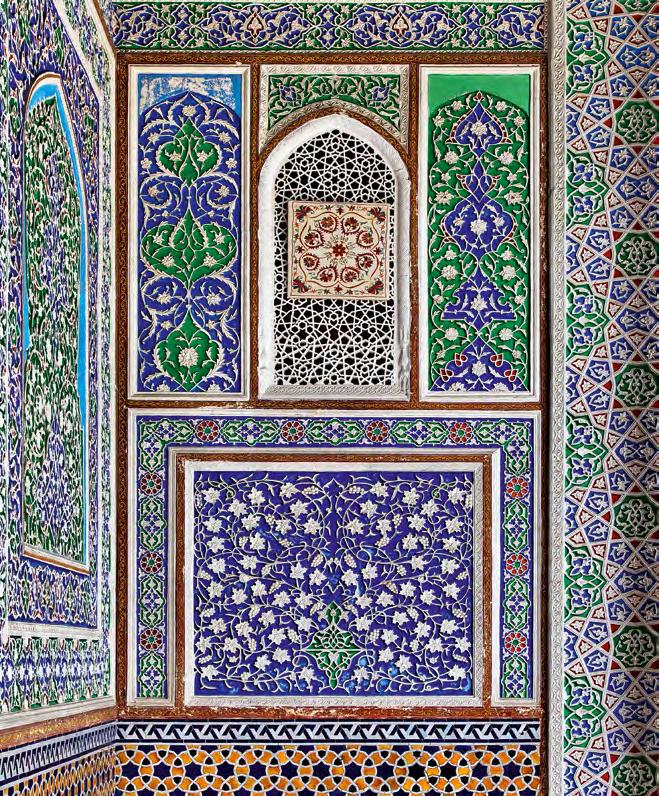

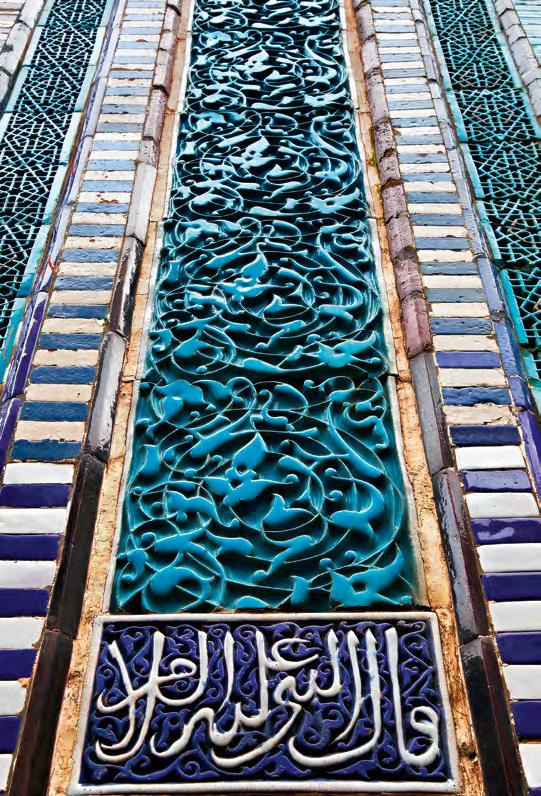

Da un labirinto all’altro, ci si reimmerge infine nel dedalo di ornamentazioni che negli edifici religiosi dell’Asia si impone quale unica via di omaggio visibile all’ineffabile, ma che pure nei palazzi e sulle loro pareti, su cui dovrebbero proiettarsi le ombre della concreta vita civile, diventa ritmo colorato e trina in rilievo.

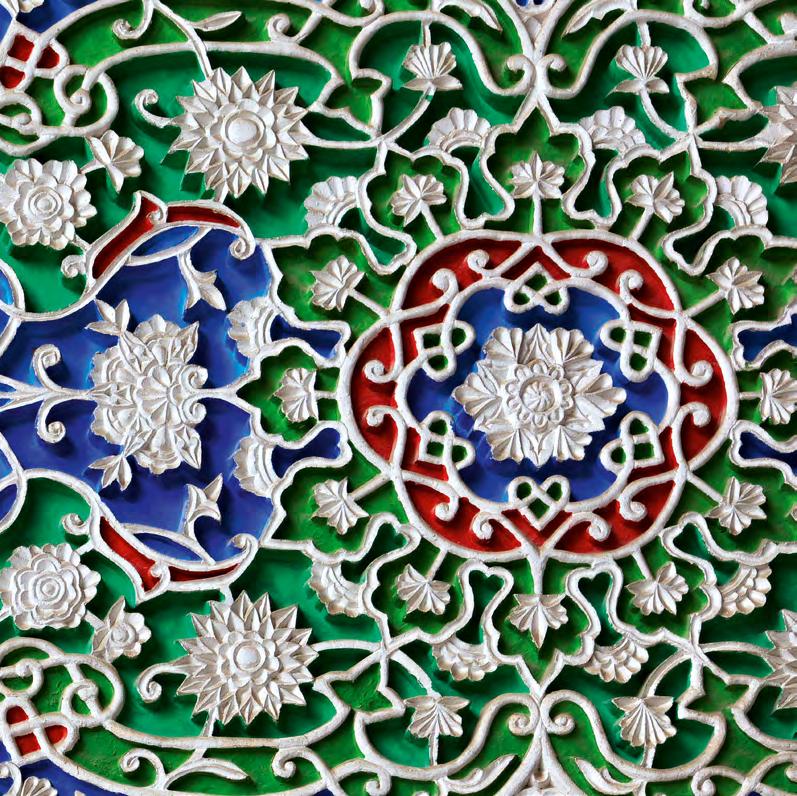

A Tashkent, la Casa dell’Ambasciatore vede dissolversi la sua grammatica architettonica sotto un fiorire di tralci, un colorato spolverio di fiori e gemme che dev’essere precipitato da un tappeto volante – da dove altro? –, e che le fotografie costringono dolcemente in geometria, facendo attenzione a non alterarne il soffice spessore di polline, come in una scultura vegetale di Christiane Löhr. Solo materia impalpabile, dunque? No.

Gange, sono le righe seguenti, di Geoff Dyer: «Non bisognava essere turisti particolarmente scaltri per capire che lo spettacolino era trito e ritrito, messo su a bella posta per i turisti, un son et lumière con centinaia di interpreti. Qualunque significato dovesse avere, gli era stato ormai sottratto, verosimilmente da molto tempo, o solo il giorno prima, o forse gli veniva sottratto ora, sotto i nostri occhi. La cerimonia mostrava ormai il pallore del dissanguamento, ma ogni sera doveva sanguinare di nuovo, riuscendo così solo ad apparire più vieta e esangue» (G. DYER, Amore a Venezia. Morte a Varanasi, Torino, Einaudi, 2009, p. 186).

12 Cfr. T. TODOROV, La conquista dell’America. Il problema dell’“altro”, Torino, Einaudi, 1992 [1982], p. 225.

13 G. DYER, Amore a Venezia. Morte a Varanasi, cit., 2009, p. 180.

17

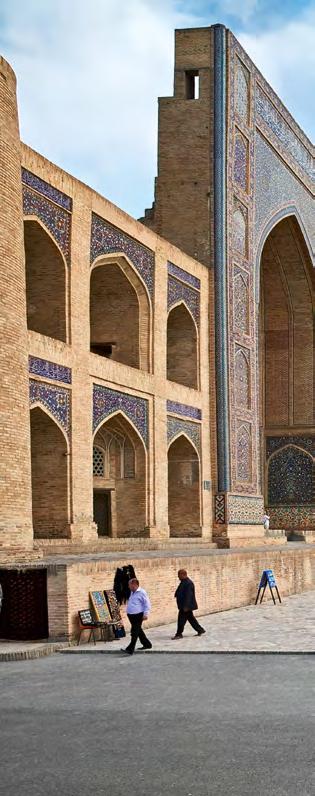

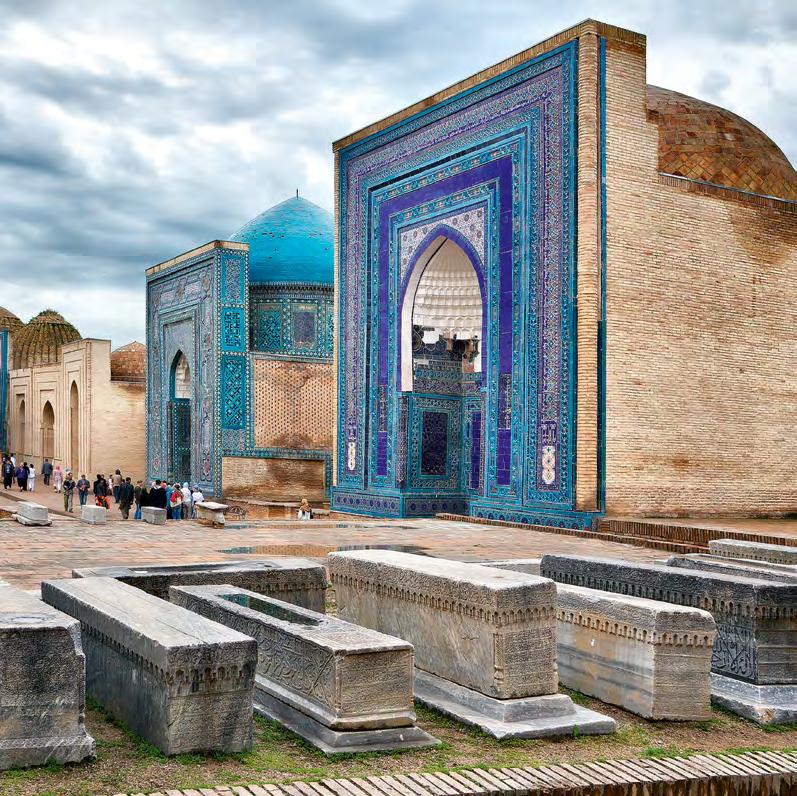

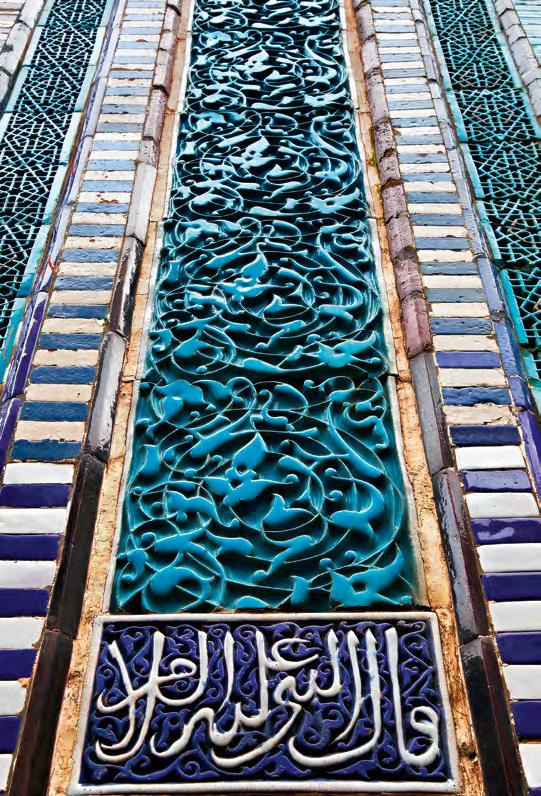

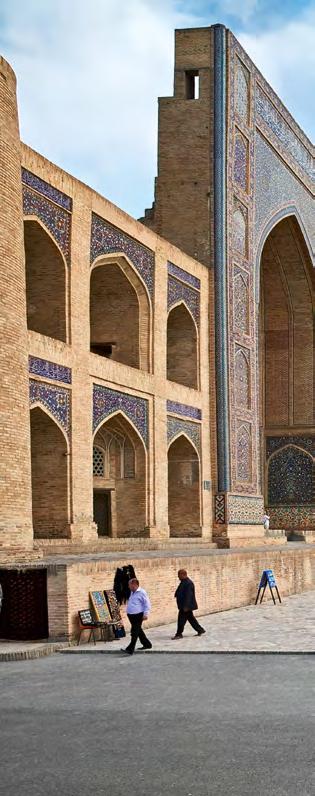

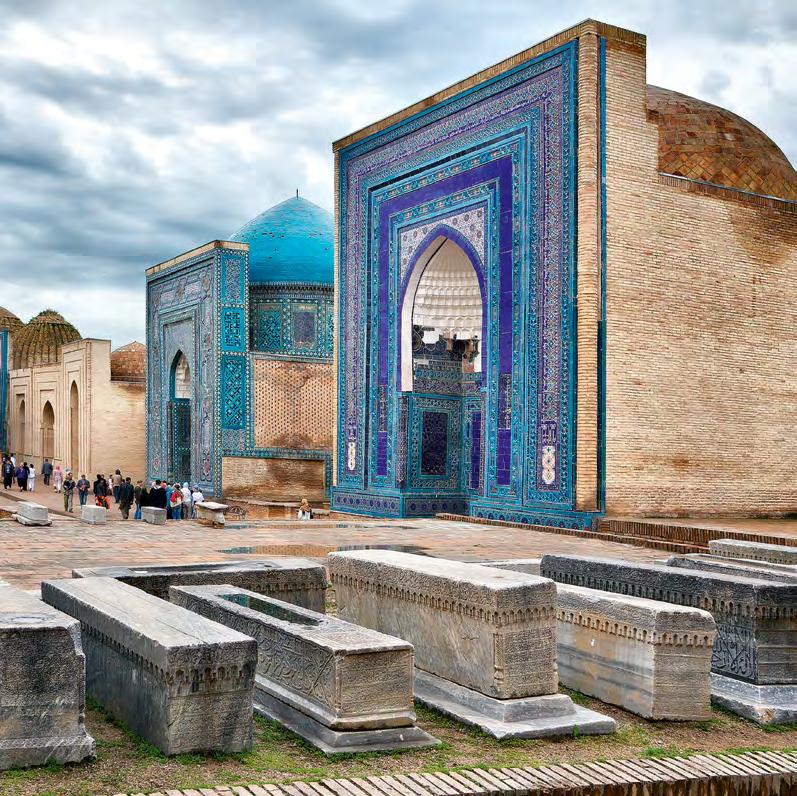

«Ancora oggi i soli nomi delle città di Samarcanda e di Bukhara richiamano alla mente antiche carovane e brulicanti caravanserragli, tappeti coloratissimi e sete preziose; ma si sa, si viaggia sempre inseguendo un miraggio o ciò che si vorrebbe vedere più di ciò che si vede» (A. Bertani). Eppure, quelle “memorie fantastiche” sotto le lenti di un 50 o 24 millimetri prendono corpo. Nella Medressa di Mir-i-Arab a Bukhara le presenze umane si muovono ai bordi di un selciato che pare condividere con gli edifici che lo circondano una perfetta planarità; ancora una volta, quasi impossibile immaginarsi dei volumi, al di là di quei brulichii fioriti in viola e blu, facciate come arazzi. E a Samarcanda, nel complesso di Shah-i-Zinda, il fotografo esalta dell’arabesco lo sviluppo in verticale, accompagnandolo a sconfinare nella vertigine. La prospettiva si fonde con la sua antitesi, con il segno che nega la realtà dello spazio. E tutto precipita verso l’alto nella profondità di un pozzo luminoso, interminabile broderie osservata a volo radente, non poi così distante dagli effetti psichedelici alla Huxley delle sequenze di raccordo finale del viaggio di 2001 Odissea nello spazio

Anche «all’interno del Palazzo Tosh Hovli, le incantevoli decorazioni delle piastrelle in ceramica smaltata ci accolgono sotto forma di un grande tappeto steso in onore degli ospiti: come un tempo le popolazioni nomadi che fondarono e ricostruirono più volte Khiva facevano nelle loro tende all’arrivo di genti amiche, così i loro discendenti hanno srotolato sulle pareti degli edifici più importanti della città una trama di segni che disseta e ristora lo sguardo. Elio Ciol, sia pure con l’occhio selettivo di un europeo, si è accorto di questa analogia e dunque con il suo obiettivo ci ripropone, ricavandoli e isolandoli dall’insieme, tanti sontuosi bukhara e tabriz. In fondo quello che viene dispiegato dinnanzi a noi, scettici uomini d’Occidente, è un grande giardino fiorito, fatto di forme stilizzate e di colori: ogni sua parte è una sorta di recinto riservato e protetto in cui poter trovare armonia e serenità. In questo giardino verticale predominano il blu, l’azzurro e il verde smeraldino, i colori assolutizzati del cielo, delle polle d’acqua e dell’erba che vi cresce attorno, ma anche quelli di un paradiso in terra che piedi profani non possono calpestare». Alla fine, osservando «quei segni quasi ipnotici, quegli arabeschi smaltati tra i quali si aprono arcane finestre, ci accorgiamo che in effetti ci troviamo per davvero nel nucleo segreto della Via della Seta: ecco davanti a noi le sue mille diramazioni, i suoi mille nodi, le sue mille oasi rigogliose. Magari l’abbiamo tanto cercata inutilmente nelle guide di carta, nei segni comuni per via, e ora invece ce la troviamo dinnanzi, la stiamo percorrendo con gli occhi, con l’immaginazione, forse anche con la suggestione di un miraggio lontano» (A. Bertani).

Curioso il destino di questa mostra: arrivare dopo l’esperienza che tutti abbiamo vissuto negli scorsi mesi, radicalmente alternativa all’idea di viaggio che – alla maniera di Ciol – si respira nelle fotografie. Nei giorni di isolamento abbiamo sperimentato in molti una immersione nel digitale senza limiti: gli incontri in videoconferenza sono divenuti abituali; ci siamo trovati – per lavoro o nello sbigottimento di non averlo più

18

– a indugiare ossessivamente fra le magiche finestrelle azionate dal mouse, lì a prometterci l’accesso al mondo che le circostanze ci avevano fisicamente precluso. Ne è scaturita, nel migliore dei casi, una sorta di serendipity digitale. Ma le sue dinamiche non equivalgono all’aggirarsi tra gli scaffali di libri caro a Carlo Ginzburg, condizione di curiosa e in parte casuale ricerca rispetto alla quale mancano sia il contatto fisico con i testi, sia la selezione a monte delle informazioni, che ora sono un’opaca valanga.

E il distinguo vale anche per i luoghi del mondo: visitarli in prima persona rimane esperienza insostituibile. E ancora più importante è saperli vivere, anche se per pochi momenti; riuscire a non transitarvi come dei corpi estranei, trovare un modo per partecipare – seppur minimamente – della loro essenza. Che significa? Vuol dire ribellarsi alla “filosofia” standard dello sbarco dalla nave da crociera; non vivere il mondo come troppi turisti al mondo vivono Venezia, scaraventati indifferentemente dentro il Fondaco dei Tedeschi o al cospetto dei mosaici di San Marco come pura massa consumatrice (e che sberleffo allo stolido affollamento, la limpidezza riguadagnata per qualche giorno, durante la “quarantena”, dalle acque dei canali!).

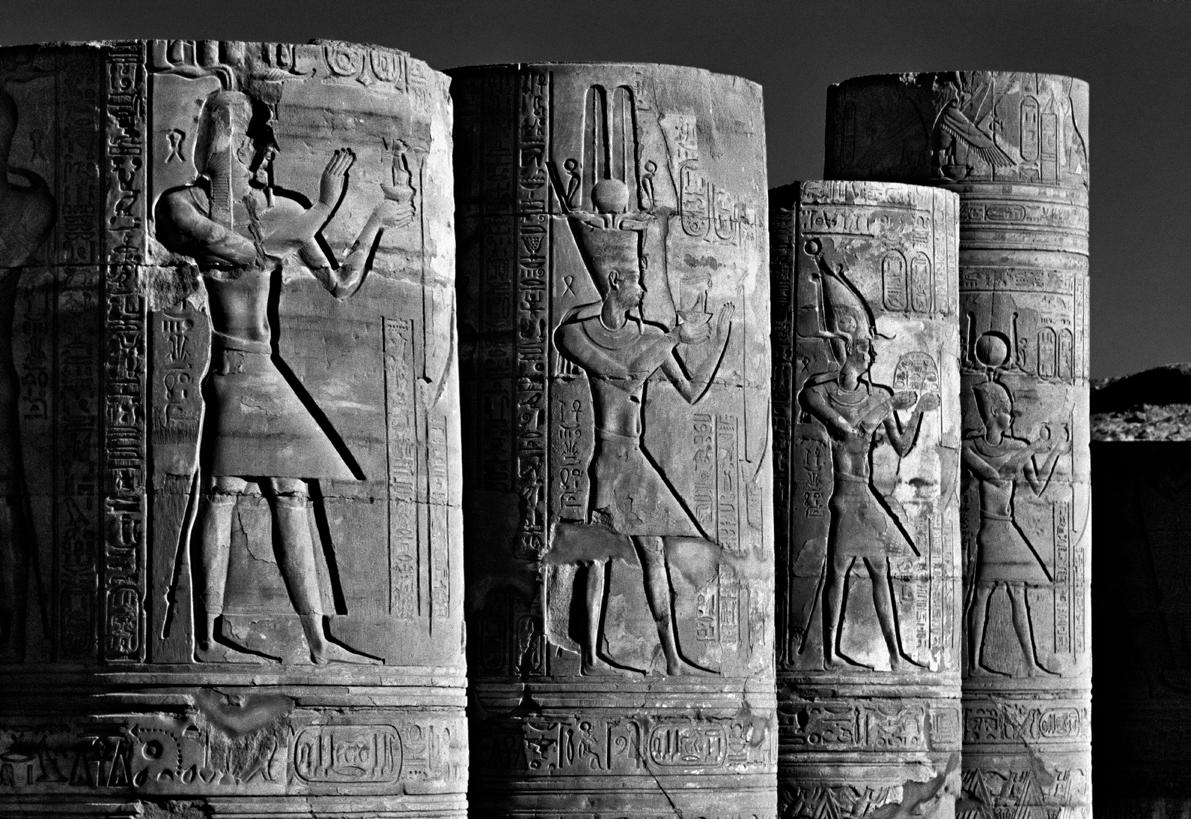

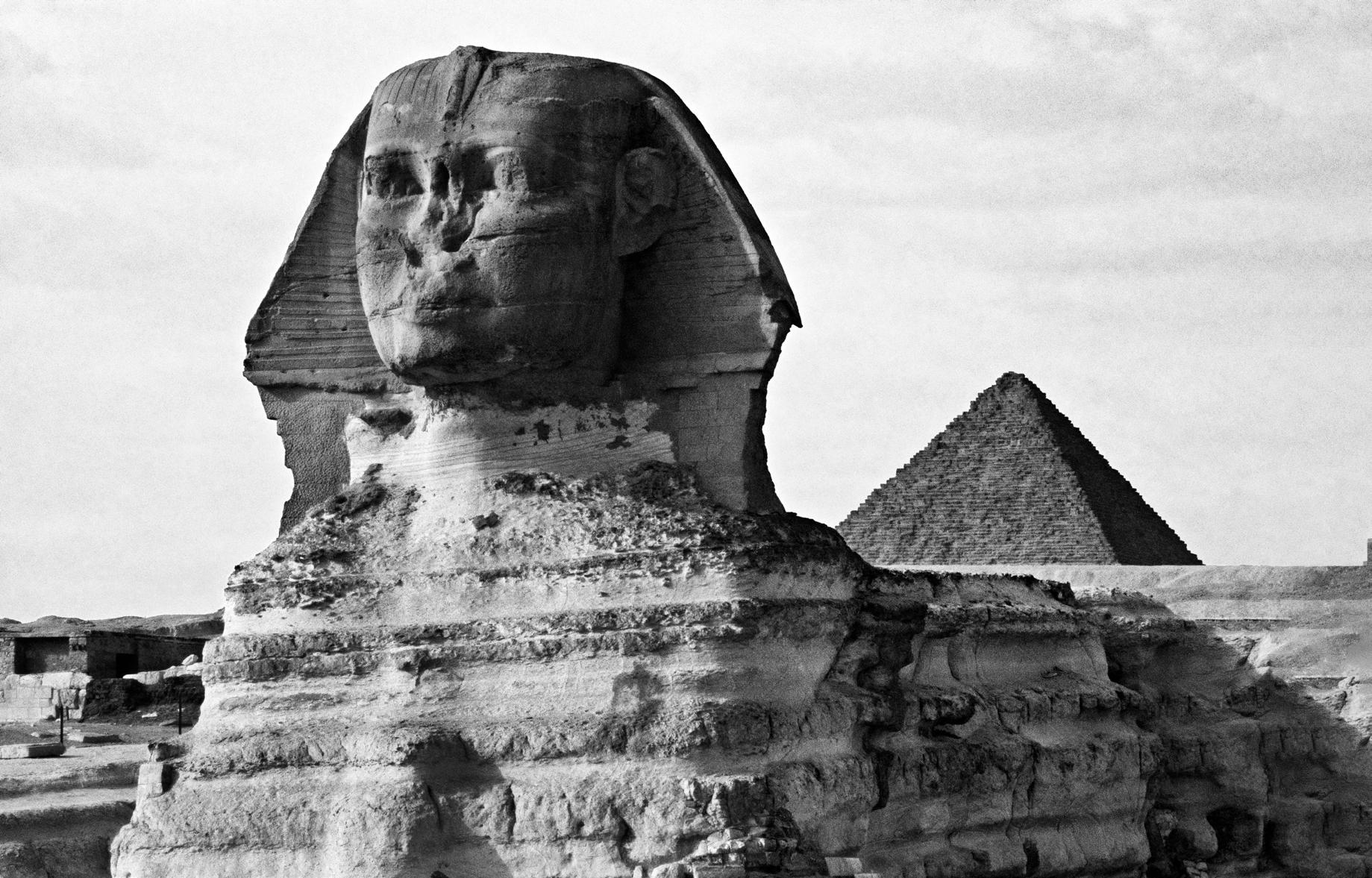

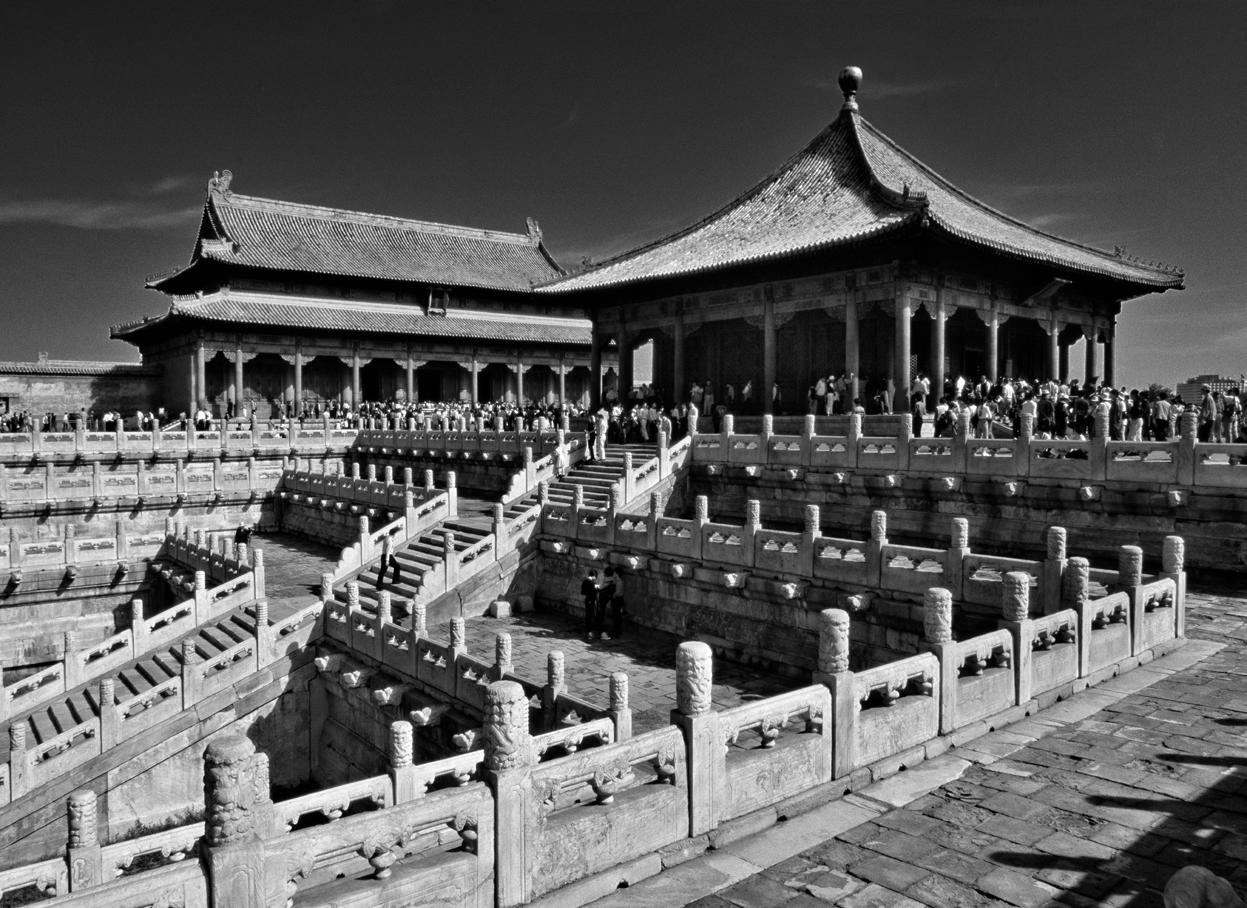

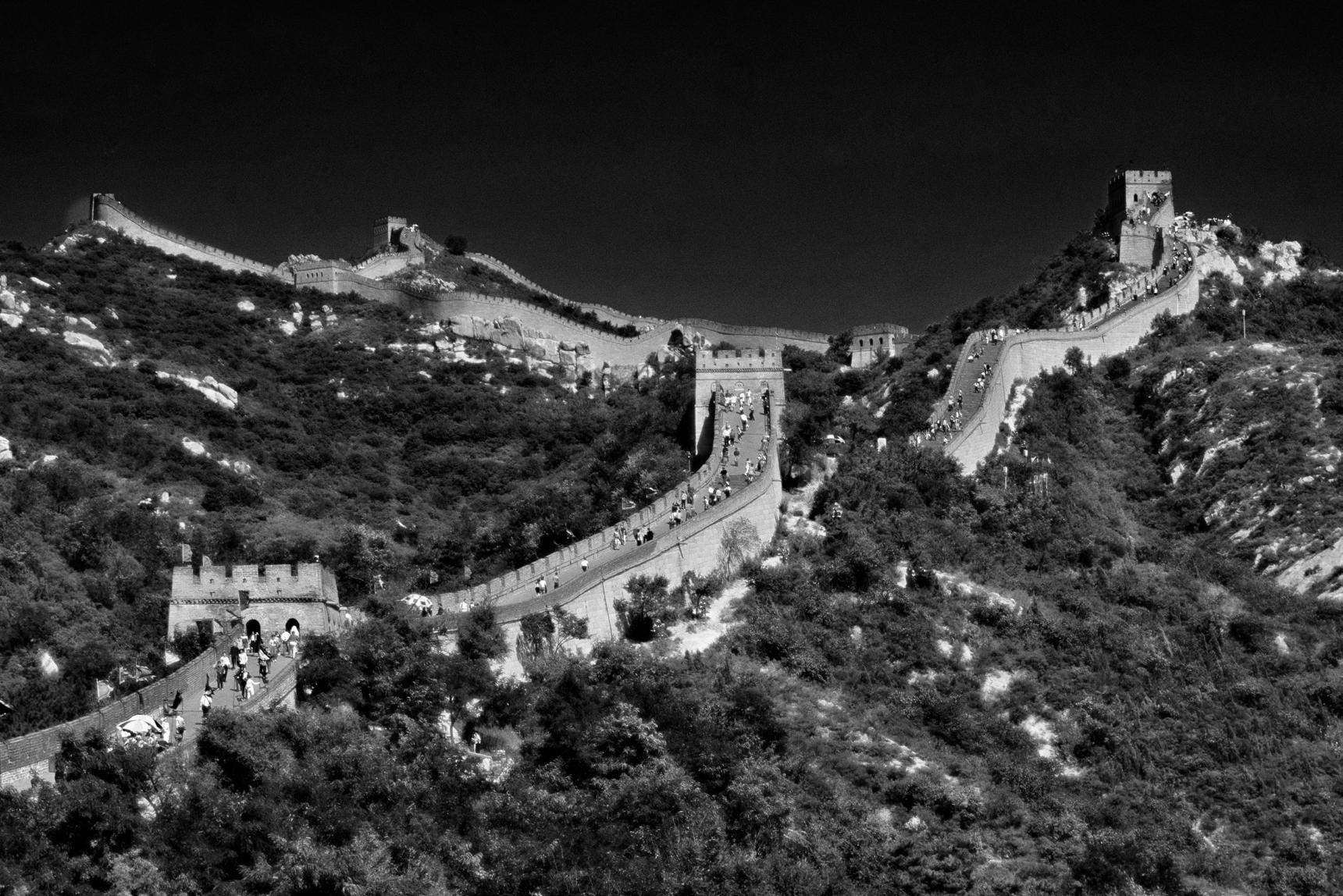

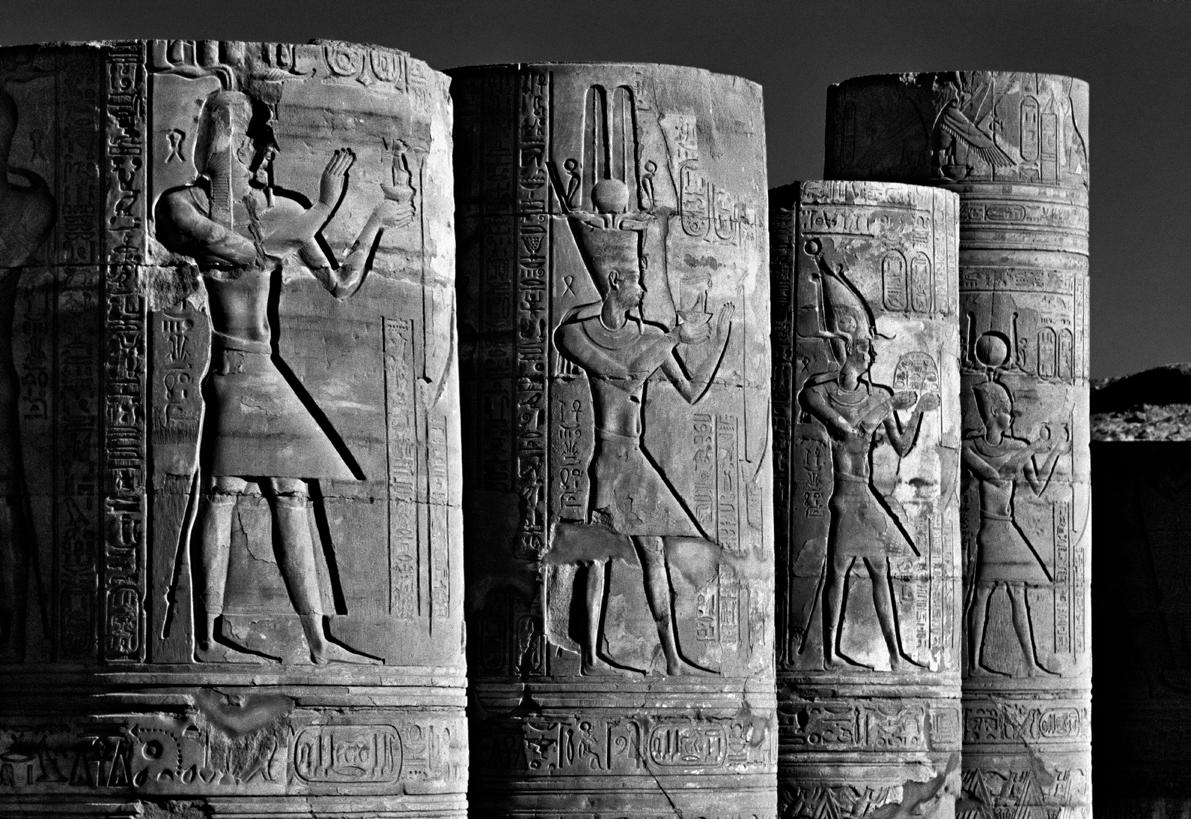

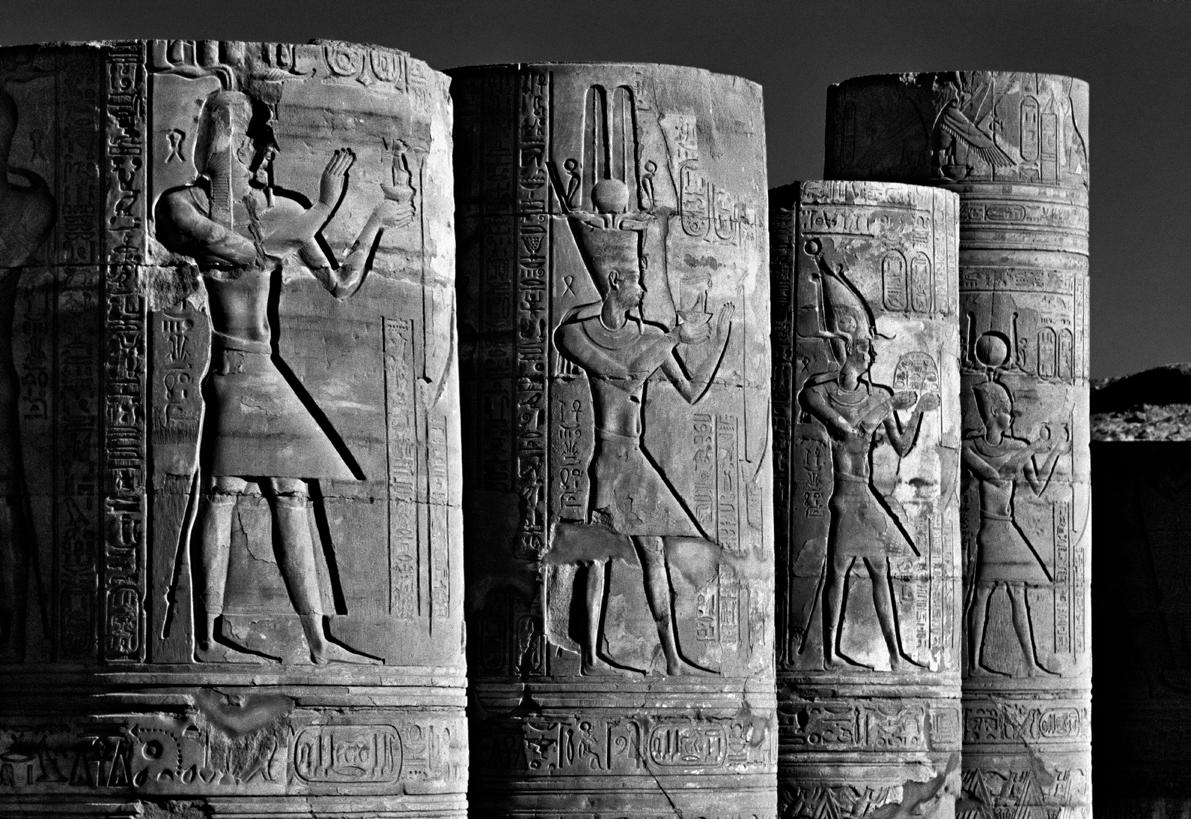

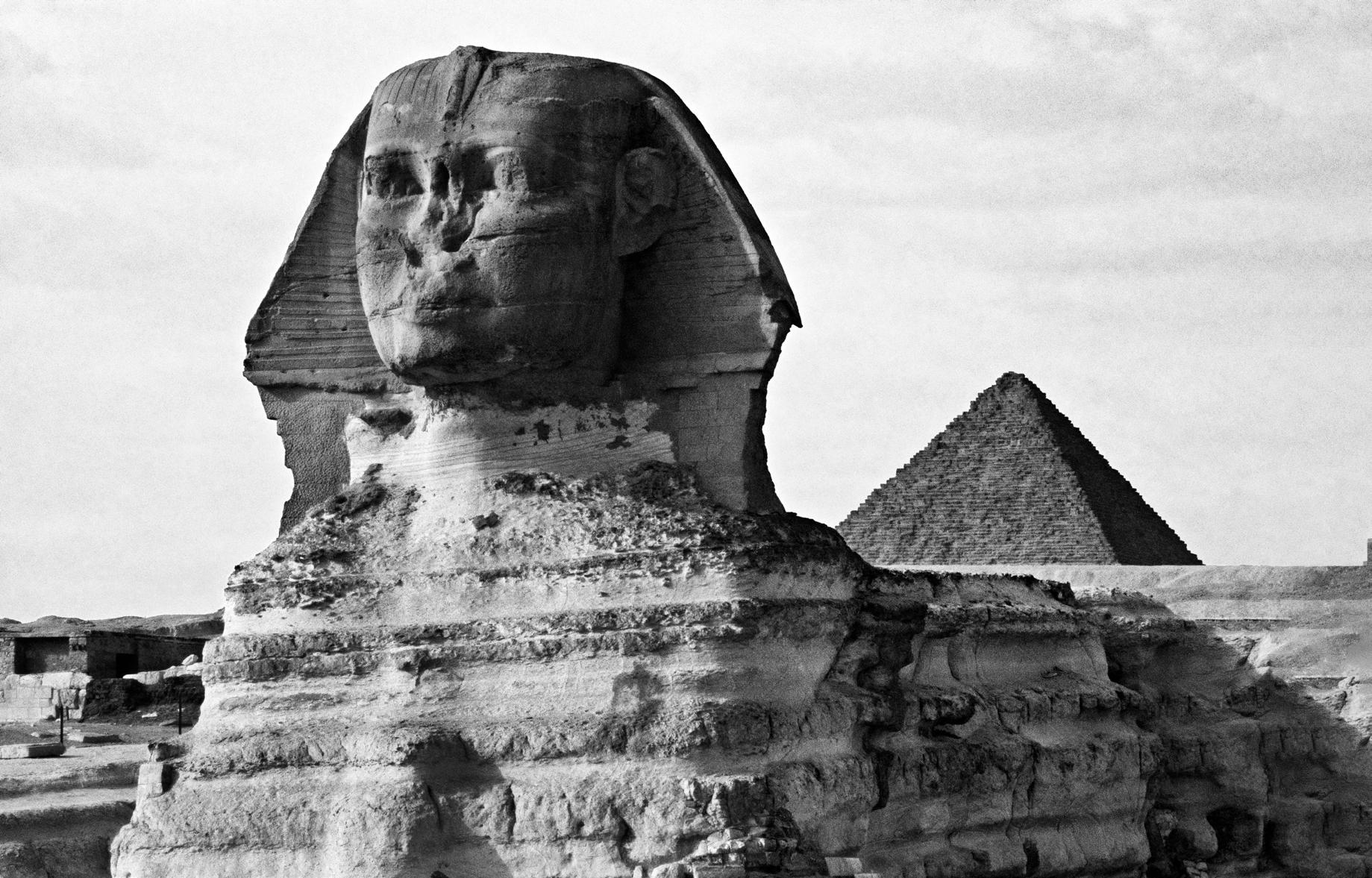

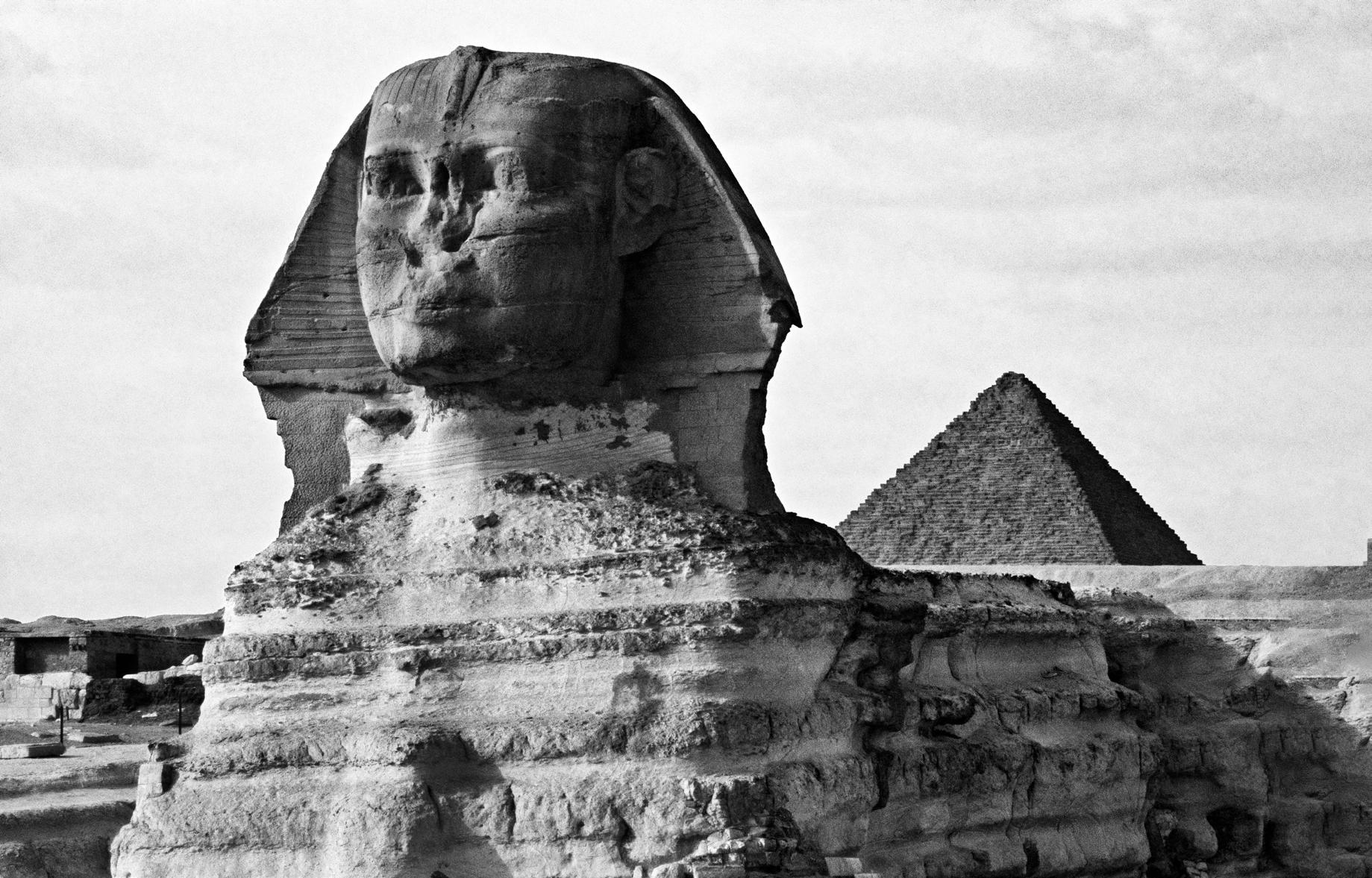

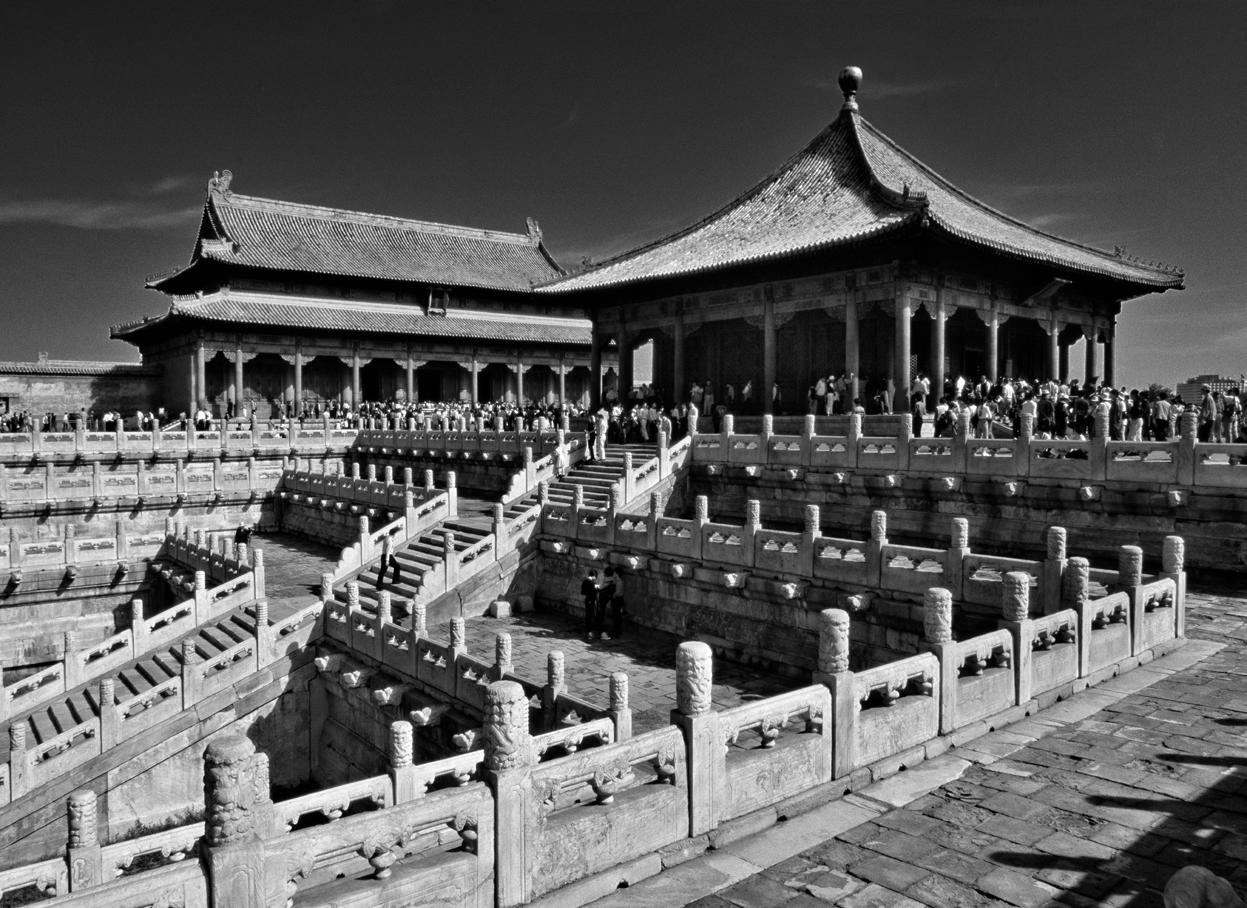

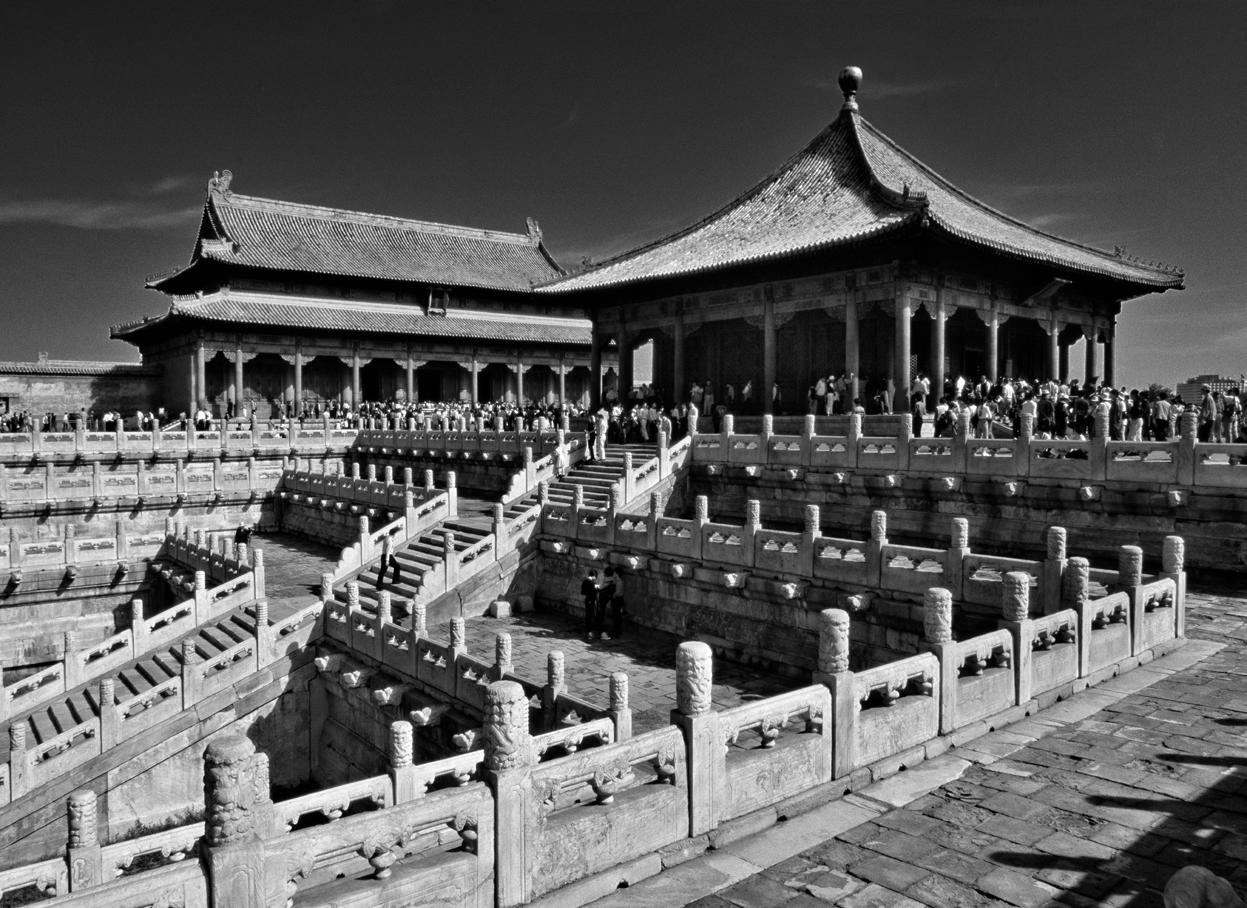

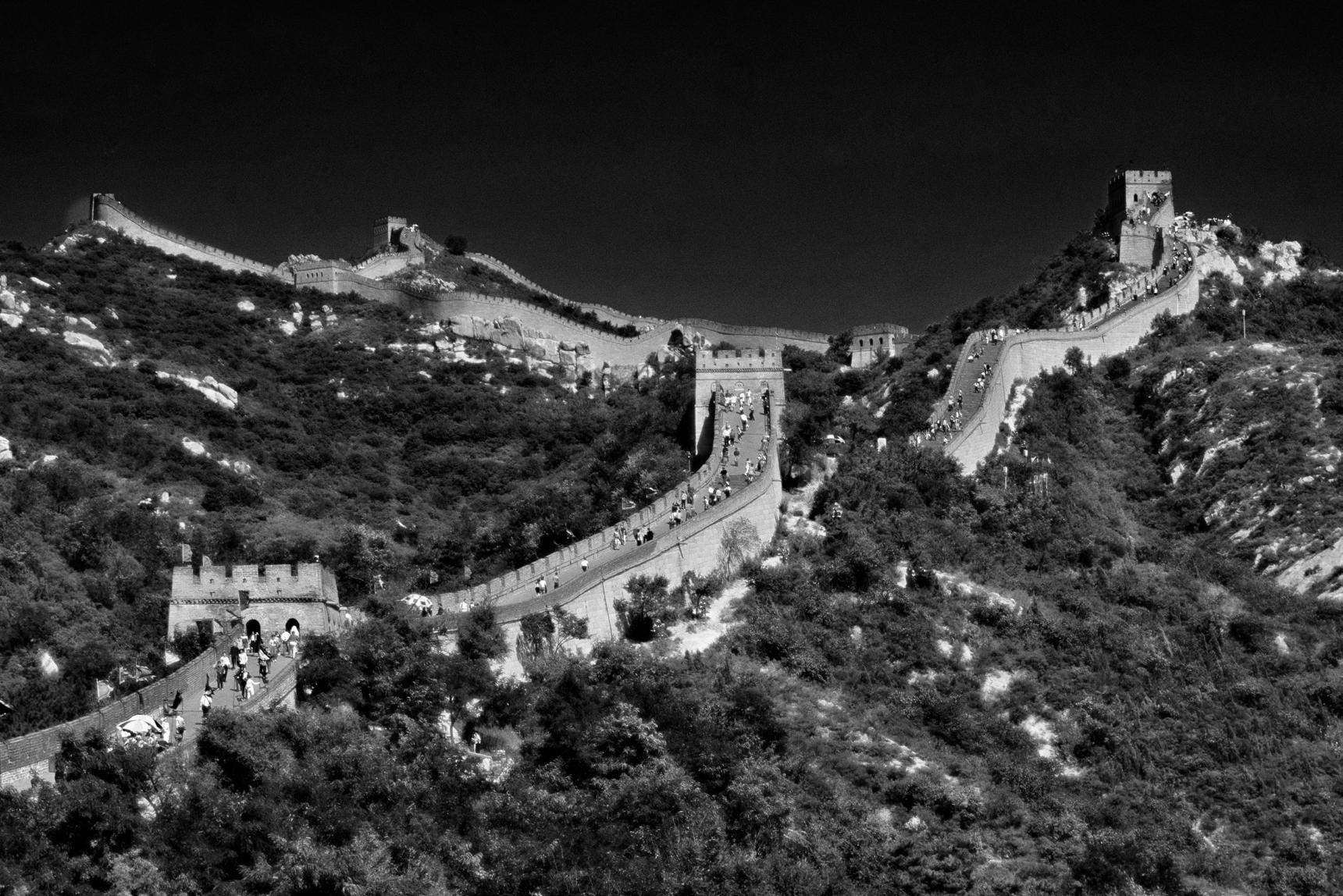

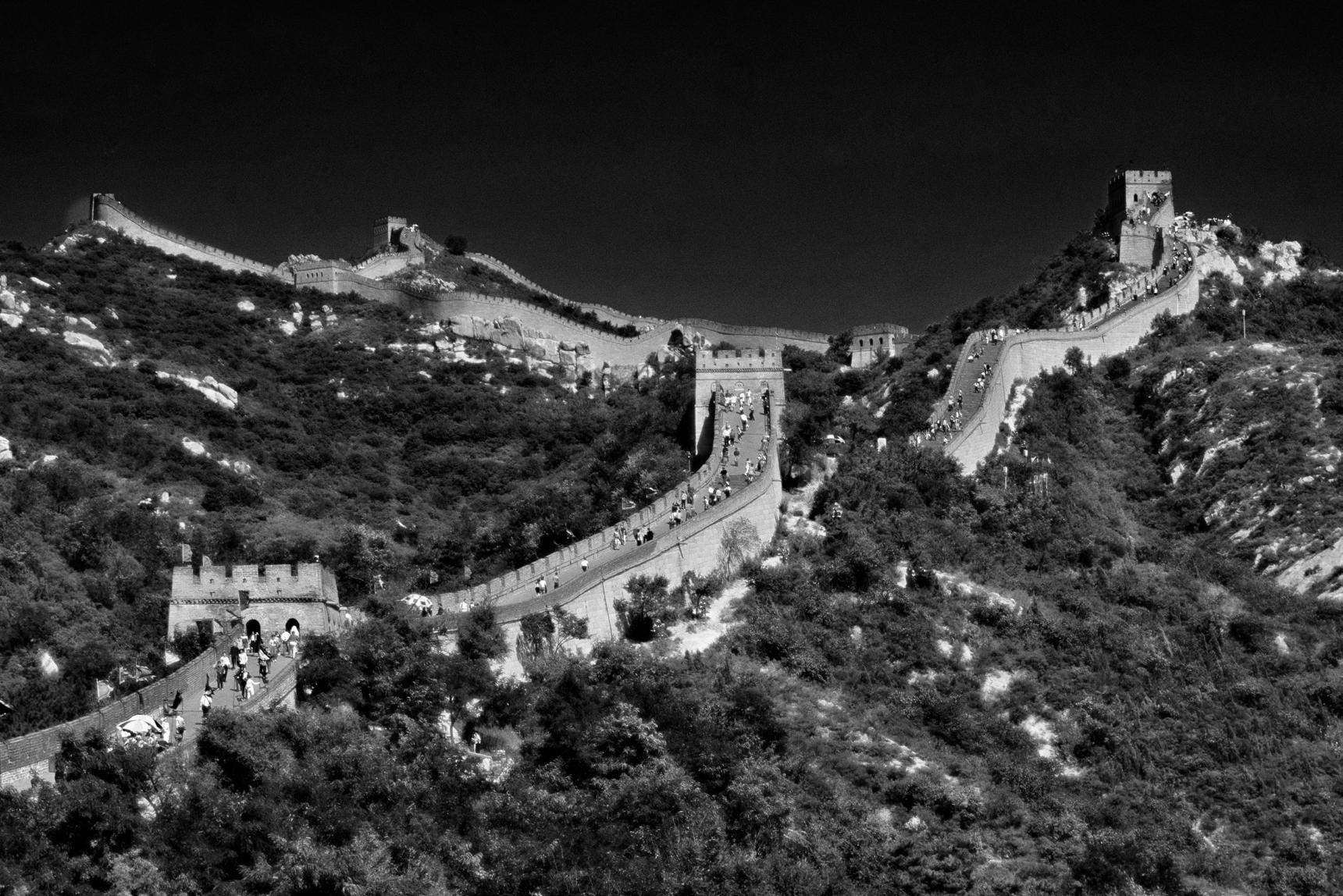

Significa non passare per la Grande Muraglia o nella Città proibita di Pechino, per le Piramidi di El Giza o per i templi dell’alto Egitto con indifferenza d’animo, ingurgitando lo stimolo visivo come un cibo preconfezionato; «l’identità stessa dei luoghi, infatti, si fonda in misura sempre crescente sugli “atlanti iconografici” che vengono attivati e messi in circolazione dai mass media»14, al punto che ancor prima di partire dobbiamo utilizzare i nostri strumenti culturali per svincolarci da possibili condizionamenti: perché «l’immagine turistica […] pre-esiste al viaggio» e «tutti noi, in quanto turisti, viviamo la nostra esperienza, fin dal momento in cui la ipotizziamo, all’interno di un immaginario globalizzato»15 .

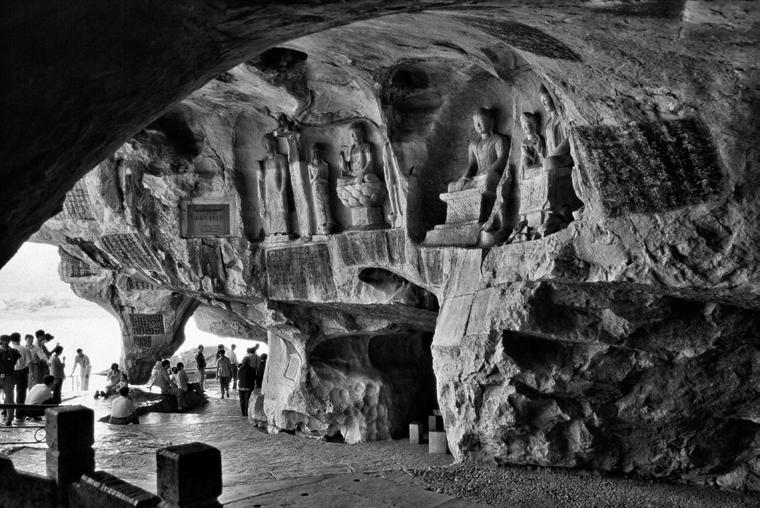

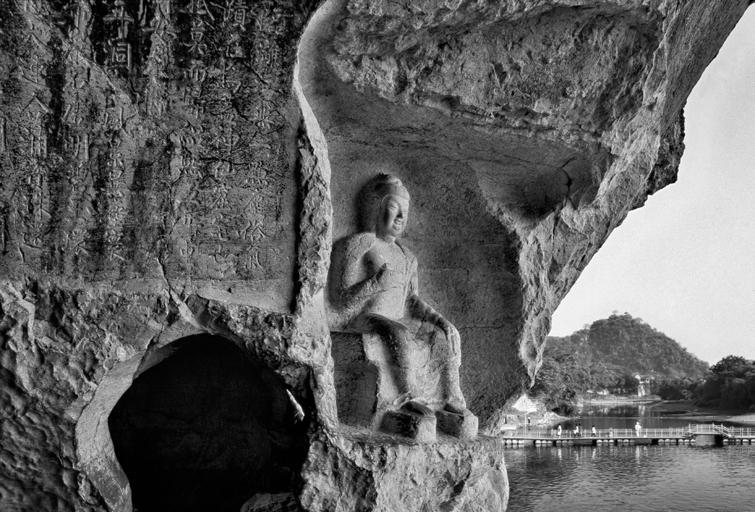

Al contrario, le foto di Elio Ciol testimoniano il senso concreto (e non la proiezione turistica) di un contesto, pur astraendo il più delle volte dalle presenze umane e distillando dagli spazi geometrie di volta in volta fluttuanti, ortogonali, caleidoscopiche.

Ciò significa indagare l’identità profonda del luogo, che a guardare in macchina sia una Gorgone di due millenni fa – e allora è come se ci si sentisse in dovere di incamerare un po’ di oscurità dalle lontananze del mito – o un bambino nepalese di pochi anni: di entrambi Elio registra la domanda muta e dà la chiara sensazione di far scattare l’otturatore non per archiviarla, nel comporsi dei moti del volto, ma per ragionare intorno al suo senso; indugiando per nostra fortuna – come avrebbe detto Kublai Kan a un viaggiatore quale Marco Polo – «in malinconie inessenziali»16

19

14 M. AIME, D. PAPOTTI, L’altro e l’altrove, cit., p. 26.

15 Ivi, pp. 6-7; «Le immagini, che sono state alla base del desiderio di partire, infatti, tendono anche a guidare, come criterio percettivo di giudizio, l’esperienza reale».

16 I. CALVINO, Le città invisibili, cit., p. 60.

20

THE SELECTIVE GAZE OF THE TRAVELLER

by Fulvio Dell’Agnese

There are different ways to travel the world with a camera in hand. Currently, the most popular way is to take selfies – anyone can do it, and practically everyone does. As long as you have a smartphone in your pocket, all you have to do is take it out, stretch out your arm (or buy an aluminium selfie stick anywhere from Amazon to the street sellers which populate every city on the tourist trail) and take a snap. The resultant photo will show your face – taking up about a third of the frame – with a scrap of tourist attraction in the background. Thanks to the presence of your face, this attraction will be woken from its slumber – which may have lasted for millennia – and lifted out of its grey existence as a building, work of art or landscape. Now it’s ready to be posted and shared with a world of social media users anxious to know exactly where you are and what you’re up to.

An alternative to the selfie culture – albeit rather out of fashion these days – is the ‘bulimic photography’ approach, which we now remember with a certain nostalgia. The second half of last century saw coachloads of Japanese tourists traversing the whole of cities like Florence and Rome, walking through the Uffizi Galleries or the Imperial Forum, with a camera constantly pressed to their face, seeing these wonders only through their SLR lenses. The childlike naivety of these tourists conveyed (or perhaps created) the notion that a place or a work of art had not been seen and appreciated unless it had been captured on camera (remember, this was before the days of Facebook and Instagram), generally with a satisfying clunk and whirr from the camera.

Of course, the advent of digital photography has meant we can binge even more on photographic images – the world around us can be captured and recorded without the photographer having to worry about carrying rolls of film around or paying for hundreds of prints. The main collateral damage of this free-forall is the heaps of visual garbage in jpeg format clogging up the memories of our computers. Whatever happened to those endless slide-projection sessions where the returning traveller shared their conquests with friends and family? Just to refresh our memories on this point – or to provide a sketch of this quaint former custom to our younger readers – let us think of the famous scene in the film Playtime (1967), where Jacques Tati, playing Monsieur Hulot, tries with all his might to get away politely from the ceremony of the projector and white screen a friend was trying to subject him to before the slide loader clicks into place and the first images of his summer holidays, separated by the click-clack of the loader moving on, are projected onto the screen. The photos, of no artistic value, are innocent scenes, as naïve as those taken in the same film by a young tourist who gets off a coach in Paris and tries to photograph a flower seller on the first street corner he comes to by putting her in the ‘right’ pose to fit his idea of how picturesque the scene should be.

21

However, there is a third way to heighten the experience of a journey through photography and it’s based on selectiveness.

It’s accessible to all travellers and encapsulates a dimension of exploration that is popular in its way, but requires a greater degree of attention, more ability to focus our perceptions. Everyone who visits Siena ends up in Piazza del Campo sooner or later, but maybe it’s only if we fully realize that we have found the “very core of the city”1 in that shell shape that (if we have a camera on us) we decide to look for an angle that conveys that kind of sensation. If we are brave enough and feel the need to attempt it, we look for an image that will recount our feeling of intimacy with that place in that moment in time, “as if we had entered a space we belong in, a space that was waiting for us.” 2

The travel photography option this exhibition revolves around is no different in substance, but quite distinct in most of its formal outcomes. A professional photographer travelling for fun, with no desire to produce reportage, over the years Elio Ciol has produced hundreds of images which have captured moments of private enchantment before a monumental building, an urban landscape, a cave drawing or a military parade with the technical and artistic mastery he has always been known for and even now continues to amaze us with. His images elude the hive of tourists which usually gets in the way of travel snaps, and are loaded with expression; they seem to be the fruit of a miraculous stopping of time, not just the ability to freeze a single instant which is inherent to photography – a tiny fragment of reality lifted up from the daily march of time by being etched on film – but also the equally decisive halt which seems to have allowed Ciol to operate in ungovernable contexts which are a far cry from posed actors against a preordained background.

How did he ever manage to find the time to sneak away from his travel companions and hold his breath for long enough to take such balanced shots that they look like the result of long-pondered exposure times and compositions … with the camera resting on a tripod?

The photos taken at Khiva and Santorini make perfect case studies. When viewed from above, the crenelated walls of Khiva make a kind of winding lace suggesting echoes of Gaudì’s Parco Güell, but more abstract: here, there are no colourful trencadis and no people. Atop those bastions – or at their feet – it seems there is room only for a kind of contemplative wonder at the almost surreally perfect interweaving of the architectural elements. At times, one almost expects to see a puff of smoke on the horizon, followed by a locomotive and a series of wagons behind it, like an early De Chirico painting.

“And yet Ciol’s images – again thanks to his perfectly rationalized use of the resources available to the photographer – also highlight the rough surface of the fortifications; their skin, if we like. Then, all their majesty, their strength and their apparent sturdiness, start to reveal an inner fragility through the cracks and fissures in the mud used to build the walls; they conceal weakness, an intrinsic inability to withstand the flow of history they were built to contain. The real enemy (even Giovanni Drogo, the young officer whose story

22

1 H. MATAR, Un punto di approdo, Torino, Einaudi, 2020 [2019], p. 12.

2 Ibidem

is told in Dino Buzzati’s ‘The Tartar Steppe’, realized this eventually) is no longer going to arrive from North or South, nor from East or West – he’s already inside the walls, just waiting for his moment. That’s why the fortifications built by men over the centuries, despite their appearance of utter solidity, still, with a kind of romantic irony, remind us of the fleeting nature of our existence” (A. Bertani).3

The purity of form in the Khiva walls can be likened to that of buildings of Santorini, although with their bicolour scheme of whitewashed walls and deep blues, the bright white against the blue of the sea and the sky, it is permeated by a different light. ‘The architecture of the sun’ is how Luciano Perissinotto has dubbed it.

In this case, the pictorial references lead us towards Magritte and his paintings with deceptively flat colours – we cannot be sure that behind some of the doors framed by Ciol’s photographs there is actually an inhabitable space, that the stairs in the background really lead to an upper floor of the house or any kind of environment in the same dimension of space-time as the one inhabited by the person who, like us, looks from outside the threshold. Once it has been flung open, will the yellow-edged shutter hurl us from the shadow it creates directly into the blue light speckled with steamed-milk clouds? Even the terracotta plant pots in another picture – which the rational mechanics of vision tell us have been placed in perfect symmetry and perspective – are not simply what they appear to be. Made of a material used since ancient times, they seem to tell Ciol that they are sentinels watching over the deep blue sea, maintaining a timehonoured balance. “His photography philosophy identifies with the remote, ancestral meaning Cycladic men gave to their existence. Ciol manages to retrieve this meaning through the more recent architecture on Santorini, signifying a continuity of ideas which is not determined by blind loyalty to the island’s past, but by an environment which is basically the depositary of immemorial situations resting – outside of time but still alive – on the Cartesian axes of the clear-cut profiles of sacred and secular buildings. These layouts have been arranged to offer themselves up to the dazzling light, where the white of the walls alternates with the blue of the sea and sky, vegetation and sheer cliffs, giving concrete form to the optical law of complementary colours. […] Earth, sea and sun are the undisputed stars of a reality which astounds and uplifts, one in which architecture has been inserted without either overwhelming or being overwhelmed” (L. Perissinotto). Lastly, in these images we can perceive the modalities and rhythms of a relationship between man and nature, which has today been seriously prejudiced, if not completely destroyed.

Therefore, the places visited by Ciol could be said to be distilled through his photographs. We could almost imagine that the phase difference between the physically experienced reality and the printed image is produced a little at a time, in the darkness of his bag, while the film wends its way home to be bathed in developing fluid. I find the idea extremely poetic, in part because the smell of camera films and the miniature armour of their cases have always fascinated me; I have always had the feeling that they are somehow alive.

3 This passage was taken from Le mura di Khiva, written by Angelo Bertani for a proposed publication of Elio Ciol’s photographic work which was never published. A number of other writings which will appear later in this essay suffered the same fate: Tosh Hovli, la Via della Seta, again by Angelo Bertani; Alhambra. Il Tempo incarnato di Elio Ciol and La Cattedrale di Siviglia. Visioni circolari by Alessandra Santin; L’architettura del sole by Luciano Perissinotto.

23

However, with Elio Ciol, the same thing happens even with digital images. Therefore, the miracle is not strictly of an alchemical kind – it also happens where there is no hint of hermetic philosophy in the air. It is no great surprise that our photographer not only embraces new technologies without restraint, but also shows that he is ready and willing to interface with contemporary history.

Even though it’s now called Saint Petersburg again, the city photographed by Ciol in 1985 is very much Leningrad.

Flags move around the enormous chessboard of the square, dragging people behind them; the people are no more than coloured toy soldiers in the visual strategy of the Communist-regime parade the photograph testifies to. What is most disturbing is the lack of scale, the disproportion that sees passers-by in the foreground dwarfed by the gargantuan billboards extolling the virtues of the heroes of the Revolution. What have ordinary people got to do with those defiantly set jaws painted against a red background or with soldiers presenting arms? Or, in other words, is there a relationship between the individual and the political ideal – whatever it may be – when it manifests as ideology? A similar question snakes, as thin as a thread, along the lines of the ‘extras’ in the mass show, sewing together the city and the great square the official celebration is taking place in. The complex pattern is captured by Ciol with great awareness as he presents it in full colour; he keeps the black-and-white option for ‘observing’ different decorative motifs. Moving from Saint Petersburg to Spain, the contrast is clear. The Mozarabic luxuriance in the decorations in the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba runs parallel to the echo of Western stylistic elements, and the series of arches stretching into the depths of the cathedral with their identical bicolour tops transforms the jungle of naves (a kind of petrified palm grove) into an optical mechanism worthy of Escher. Ciol’s decision to frame them from below accentuates the rhythm of the architectural forms to the point of abstracting them. The development of the space merges into the decorative labyrinth of the surfaces, which Ciol explores in other photographs where polyfoil twin and triple lancet windows are absorbed into the complex weave of reliefs. In the Alhambra at Granada, photographed by Ciol in 1994, the rhythms of the wall surfaces are again a kind of lacework dematerializing the massive structure; our photographer chooses a number of angles that act as ‘dynamic fences’ within which the eye is invited to roam happily while the whirl of lines, protuberances and concavities absorbs the original geometry and almost conveys the sensation of a pulsing ardour, or fecundity unleashed by the light.

The surfaces “play with the large pointed windows and the doorways, the sides of which are not anchored to the ground, but hover above it. Around and beyond them is a foretaste of the indescribable. […] The round and pointed arches speak of potential places where the dimension of time fully reacquires the dimension of ecstasy, […] delineate a horizon that may one day be reached. Forests of columns, maze-like spaces, foreign writings and clear skies allude to the question of travel and thematize vision as an opportunity for reflection and pleasure which invites us to shake off the separation between the realm of emotions and the realm of rational consciousness” (A. Santin).

4 “The detail, as a remnant of a glorious past, confronts the ephemeral present and leads History back to Man. He is invisible but present in the round window, in the light which bounces off the black circle of darkness; he lives in the technological additions, in the use of infra-red sensors, in the arrangement of bricks; he is there in the skilfully carved marbles which frame what is there: the black hole of a window, the invisible blackness of the interiors, the dull white of the horizons close to our gaze. The lack of depth makes the two-dimensionality of these works a question of method. The statue of Saint Peter – the only figural

24

The ‘homes of symmetry’ that are Ciol’s photographs of the Cathedral of Seville are set up in a very similar fashion: his “description is not interested in the totality of the architectural structure, but dwells on a fragment of it”; is “immersed in a containing silence and constructed in an almost graphic composition” (A. Santin)4 and even before the Giralda (built in the 12th century as a minaret and later converted into a bell tower), Elio chooses to ignore the grandeur of the building as a whole and focus on the symmetry of an idea translated into decoration.

However, it is not only places with such a high aesthetic and spiritual coefficient which enthral him. Even in less important buildings for the history of art, such as (seeing as we’re in Seville) Pilate’s House, Ciol traces the conditions under which ‘vision’ is rejected in favour of ‘seeing’.

The composition of shadows, forms and historical aftertastes in the photograph where a sculpture representing a female figure is lying under a panoply of shields and quivers is extraordinary. Who might this woman be? She looks like a sleeping Arianna, but the relief above her – which seems to give substance to her dream – has nothing of Dionysus in it. The weapons look much better fitted to the imaginary of the male figure immortalized in the form of an Imperial-era bust, who sits atop a pedestal to the left and observes her in a reverie. His shadow stretches tentatively towards her, like a lover unsure of how far he can exercise control over the thoughts and desires of his companion.

It is above all the balancing of light and shadow in the photograph which transforms the seemingly random arrangement of the collector (who filled the whole house with an eclectic mixture of Classical, Mudéjar and Renaissance art) into something metaphysical.

His travels around the Iberian peninsula then take him to the Basque Country, where he captures an unexpected beast, one born from a deliberate desire to create a contrast with its surroundings: the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao.5

Ciol photographs the museum following the same visual parameters on which he based his interpretation of the Cathedral of Seville or the dizzying Moorish architecture in Córdoba: his aim is not to display a work of architecture but to interpret a landscape. A strip of nature full of metamorphic rock, hollows and shimmering crags, which the gaze roves over alertly and restlessly, with the special ability of lateral vision to detect highlights and areas of roughness which would escape the front-focused gaze of a completely static form of observation.

Forms are captured from angles resulting from the kind of flow which constitutes the most authentic form of design, but at the same time launches them into a dimension of abstract, almost musical collisions. The titanium sheets used as the cladding of the building are nothing more than beats in a complex rhythm, a swathe of matter in the light. Its volume is increased by the temporal compression effected by the closing and re-opening of a camera shutter, expressed through the solid ambiguity of its status as dormant energy, although we imagine that it could twist into another shape at any time. Above the mobile heap the building seems to collapse into, at times the sky loses its purpose as an atmospheric agent – its natural dimension is

element portrayed – holds the key to the circularity of Nature and History, of thought and action, of space and time.”

5 In the following paragraph, several excerpts from Fluide architetture have been adapted; this essay was written by the present writer to accompany the Elio Ciol exhibition at the San Maurizio gallery in Venice, in 2008.

25

cancelled out by a metaphysical light or it sinks into a dark silence, paving the way for the arrival of gigantic, long-legged arachnids, conceivable only when faced with an alteration of the visible world of this kind. Here, architecture appropriates the taste for the spectacular which guides the contemporary art scene, but the shell of this museum-cenotaph – of what is ‘no longer the home of the gaze’, of contemplation focused on the sacred ostension of a painting or sculpture, but has become “the place where the gaze is inverted”6 , where the exhibition space and its internal dynamics are refracted and overturned – is presented quietly, without any particular fuss, by Elio Ciol.

The eye of the photographer, which in other cases is so respectful of the context and its general use, here perceives that form has been given precedence over function. The building, which only incidentally houses works of art – a kind of elastic container which, by giving the impression that it is ready to expand its size in an anarchical fashion, tends to eclipse what is found deep within its bowels, i.e. the artworks –, presents itself as an independent geological phenomenon. Monstruous and impossible to view from a single perspective, this cyclopic and protean creature could be either a dam and a mountain.

Then there are the clouds.

Let’s take the Mongolian clouds at Karakorum as our first example. In Ciol’s photographs from 1987, they loom over temples, the mouths of water-spouts and perimeter walls marked by four-cornered towers that seem to sew the earth and sky together with long stitches. Even an unexpected tortoise pokes up its head from among the brushwood; this gentle stone creature is a monument to the patient observation of all things being created and then destroyed. Yet those flocks of water vapour always hang in the sky, giving every landscape the suspended feeling of a vision. Even if a forlorn soul passes underneath them riding a mule, those clouds refuse to go back to being a simple atmospheric condition recorded at a fleeting moment of existence. They hang there, like hierophants creating a bridge to that which is holy, carrying all the mysticism and ritual which stick to the insides of a cracked bronze cauldron; they dialogue with the symbolic tenants of a temple – the grinning protomes on the cornices – finding balance in their horizontal sharing of transcendence.7 The monastery at Ulan Bator also pitches under a choppy sky; its pagoda rooves look like a fleet of curvy boats waiting expectantly for the crossing lying before them among the wave-clouds, with their crew of idols on top watching hopefully for signs on the horizon that the storm is abating. In some cases, his journey under a sky streaked with white leads our photographer even further from urban civilization. In Armenia, for example, he follows the lines of Zorats Karer, where the clouds broaden the perspective of the lines of standing stones. These gigantic prehistoric flints have been marking out the plateau they stand on for millennia, and now they unprotestingly allow Ciol to ratify the visual control they exercise over the landscape in his shots.

His journey also takes him to the remote Wadi Matendush, in Lybia, where the prehistoric graffiti show the forebears of rhinoceroses, elephants and crocodiles, the great beasts who were the masters of that land

6 J. CLAIR La crisi dei musei. La globalizzazione della cultura, Milan, Skira, 2008 [2007], p. 102.

7 See H. DAMISCH, Teoria della nuvola, Genoa, Costa & Nolan, 1984 [1972], pp. 67-68: “[…] the signs of the sacred are no different from any other signs: they belong to sets, to historically constructed systems in which the lateral relationship of sign to sign prevails over the direct, vertical relationship between signifier and meaning which should define the symbol. […] The cloud

26

before it became a desert and which the human populations of those times portrayed with the utmost respect in images at the same time both simple and vividly realistic. Bovine creatures and giraffes were also depicted on the walls of the fossilized river – etched into the rock with the spiky immediacy of an Expressionist xylograph – for the purpose of bringing luck to the men hunting them.

At Petra, on the other hand, carved stone becomes a painting. The eye perceives the geological ruffles as a living fabric whose fibres paint a surreally elastic web of reds and oranges; vegetation nestles into it as if into a siliceous, speckled, pulsing flesh.

And yet the rose-tinted rocks of Petra also become architecture, in net contrast to their surrounding landscape. The temples, with their careful compositions of columns, tympanums and lintels, look like the vestiges of a city reclaimed by nature and pulled into the very hills; one gets the feeling that a stone curtain is ready to fall definitively on the monumental facades, although the reality is the opposite: they were carved out of and emerge from those hills, as a kind of colossal relief sculpture emulating architecture. There are photographs where the process of transformation is unmasked: kneaded into geological doughs we imagine smelling sweetly of pastry, the creamier the rocks look, the more clear it is they are the firm substance of the building. The shafts of the columns confess that they belong to the mountain and hold up nothing more than the ghost of an architrave. However, on the visual level, we wonder whether this metamorphosis could take place in the opposite direction – could it be that the row of columns is losing its original function and being swallowed up before our eyes by the power of nature, which by now has halfdigested the capitals and the door frame?

At the end of the day, this fate is not so different from the one endured by cities which have fallen into decay at some time in the past and which archaeologists have brought back to life, balancing them on the fence separating places of natural beauty from cultural attractions. These cities, evocative in their decay, go back to being part of the land they arose from.

To stay in Jordan for the moment, in Jerash, the line of columns marking out the forum, with their unusual oval formation, still has the ability to connect these Roman-era ruins with their erstwhile urban identity. But the Corinthian capitals from the Temple of Artemis can be seen on the horizon, sticking up among rocks and bushes, against a deep-blue sky, like actual acanthus plants rooted to the ground.

Then we have Leptis Magna: the city in Tripolitania built by Septimius Severius, the subject of one of Elio Ciol’s most memorable series of photographs. His lens pauses on the corner of a street bathed in a blinding light and gently caresses the form of a lintel traversed by a flowered scroll decoration, which still curls in the forum of the most beautiful Roman colony in Africa, between cracked rails made of ovoli and beads, almost as if it was one of the slithering locks of the terrible Medusa lying beside it. By doing this, Ciol’s photograph once again contradicts the initial immediacy of its existence, just like in certain places where earthly time stops and dilates; the gaze is then forced to stop to contemplate a Leptis Magna in black and white, as if its Gorgons had captured the aesthetic dimension of their past life and frozen it indefinitely.

has no meaning it can be given in itself; the only worth it has comes from the consecutive, oppositional and substitutional relationships it entertains with other elements in the system.”.

27

“When shadows imprint, and start their gradual exhalation of the past”8 we see the geometries that pulse under the skin of the image, tying the ruin to what it used to be and to the further step of abstraction the artist’s gaze leads it towards.

We see clumps of brushwood which replicate and envelop coils of stone, or which – marginally more realistic than those colonizing Mantegna’s fractured rocks – mark out the lines of nature’s resistance to the polished seal of history. We see columns lying in the deserted belly of a market – cylinders brushing the corners of octagons and circular convexities in unbroken equilibriums which seem to have lasted forever, like the bottles in a Still Life by Morandi.

“I’m talking about paint, about shape, about the void

These objects sentry for, and rise from”9 .

Forms, masses, vacuums …

The marks made by man on the landscape are made of these: the primitive dwellings of Cappadocia (the ‘fairy chimneys’ are human dens that exist as the antithesis of the idea of a ravine, balancing on crumbling peaks. They’re like the reversal of the funnels of Calvino’s Laudomia, on the slopes of which “in every pore of the stone there are invisible hordes”10 or the terraces Ciol photographs in Nepal. Here, the hand of man has managed over the centuries to gently mould the high-altitude slopes by carving out a series of winding, sinuous stairways which make one think of a green shore where each stage of the rise and fall of the tide leaves its mark. Yet in that same high-altitude corner of the globe, our photographer – the same one who has just taken landscape shots with a composure and rarefied abstraction worthy of a Zen garden, images whose forms could be compared to Tony Cragg’s sculpted surfaces – also knows how to savour the smell of lands where people go about their daily business and the inelegance of living on these lands; all he needs is the intense stare of a child to capture the dignified fragility of her fellows. The girl sits upon a rock, like a nymph in a Poussin painting, but the pool of water in the background, around which the humble, circular life of the village goes on, presents to us the murky texture of a daily fight for survival, which no aesthetic consideration can persuade the artist to ignore. He starts off a different process of sounding the visible world, one which accompanies the emergence of some kind of light in the darker realms of humanity. There is no time to share a part of his existence with the subject of his composition, but his respect for her shines through. Not many people feature in these photographs – Ciol takes their portrait only when he is sure he will not slide down the slippery slope into anecdote or watered-down exoticism – because, all too often, “back there, behind the figure in the centre, the individual photographed becomes the mere image of that individual. They lose their own personality, which is replaced by what the photographer wants them to convey – whether the mystic, exotic, picturesque or wild – and rendered

8 C. WRIGHT, Noon [from China Trace, 1977].

9 C. WRIGHT, Morandi [from China Trace, 1977]. The section of this essay dedicated to the ancient Roman city in Africa is in large part derived from F. DELL’AGNESE, Leptis Magna, in E. CIOL, Leptis Magna, Venice, Edizioni del Cavallino, 2007.

10 I. CALVINO, Le città invisibili, Milan, Mondadori, 2002 [1972], p. 143.