Sephardim in the philately of the former Yugoslavia

By Yuri Vladimir Montes,

By Yuri Vladimir Montes,

By Yuri Vladimir Montes,

By Yuri Vladimir Montes,

In the late fifteenth century and midsixteenth century, most of the Sephardim settled in the Maghreb and in the nearby kingdoms of Portugal, Navarre and the Italian states.

The Jews who settled in the Ottoman Empire were well received by Bayezid II. The number of expelled Jews remains uncertain, the figures have ranged between 45,000-350,000 but in recent research they are between 70,000100,000, being between 50,000 and 80,000 from Castile.

The Jews of Bosnia and Herzegovina have a rich and varied history, surviving World War II and the Yugoslav wars, the Jewish community in Bosnia and Herzegovina has one of the oldest and most diverse histories in the former Yugoslav states , and is over 500 years old, in terms of permanent settlement.

Being an autonomous province of the Ottoman Empire, Bosnia was one of the few territories in Europe that welcomed Jews after their expulsion from Spain in 1492.

The first Jews arrived in Bosnia and Herzegovina from 1492 to 1497 from Spain and Portugal. World War I ,saw the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and after the war Bosnia and Herzegovina was incorporated into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In the 1921 census, Ladino was the mother tongue of 10,000 of Sarajevo's 70,000 inhabitants. By 1923 there were 13,000 Jews in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 1941, at its height, the Bosnian Jewish community numbered between 14,000 and 22,000 members of whom 12,000 to 14,000 lived in Sarajevo, comprising 20% of the city's population. Today, there are approximately 400 Jews living in Bosnia and Herzegovina..

Postcard sent from Sarajevo to Nancy, France in 1908

With the invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941 by the Nazis and their allies, Bosnia and Herzegovina came under the control of the independent state of Croatia, a Nazi puppet state. The Independent State of Croatia was headed by the notoriously anti-Semitic Ustaše movement, and they began to persecute Serbs, Jews, and Roma.

During the Second World War, 70,000 of the 80,000 Jews in Yugoslavia would die, many of them Sephardic, Sephardic life in Sarajevo suffered the ravages of Nazi persecution and its Croat allies, they would never recover, between 1945-1981 many emigrated to Israel and Western countries.

Then a new migratory wave in 1992 with the Balkan war would mean the final blow. Currently there are just under 400 Jews in Bosnia and Herzegovina, of which 85% are Sephardim and 70% are over 50 years old, given the low expectations in the country, it is to be assumed that in the coming years there will be a decrease in the population.

It is located on Mount Trebevic, in the Kovacici- Debelo Brdo area, in the southwestern part of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

It was in use from the beginning of the 16th century until 1966.

Settled by Sephardic Jews, it also became the burial place for Ashkenazi Jews after their arrival in Sarajevo with the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the 19th century.

It contains more than 3,850 tombs and covers an area of 31,160 square meters.

It has four monuments dedicated to the victims of fascism: one Sephardic designed by Jahiel Finci and erected in 1952, two Ashkenazi ones, and one dedicated to the victims of Ustasha militants.

Many notable people are buried in the cemetery, including Rabbi Samuel Baruh (first rabbi of Sarajevo from 1630 to 1650, his grave is believed to be the oldest in the cemetery), Rabbi Isak Pardo (rabbi from 1781 to 1810), Rabbi Avraham Abinun (Chief Rabbi from 1856 to 1858), Moshe ben Rafael Attias (1845 1916), Laura Levi Papo LaBohoreta (early 20th century writer), and Isak Samokovlija.

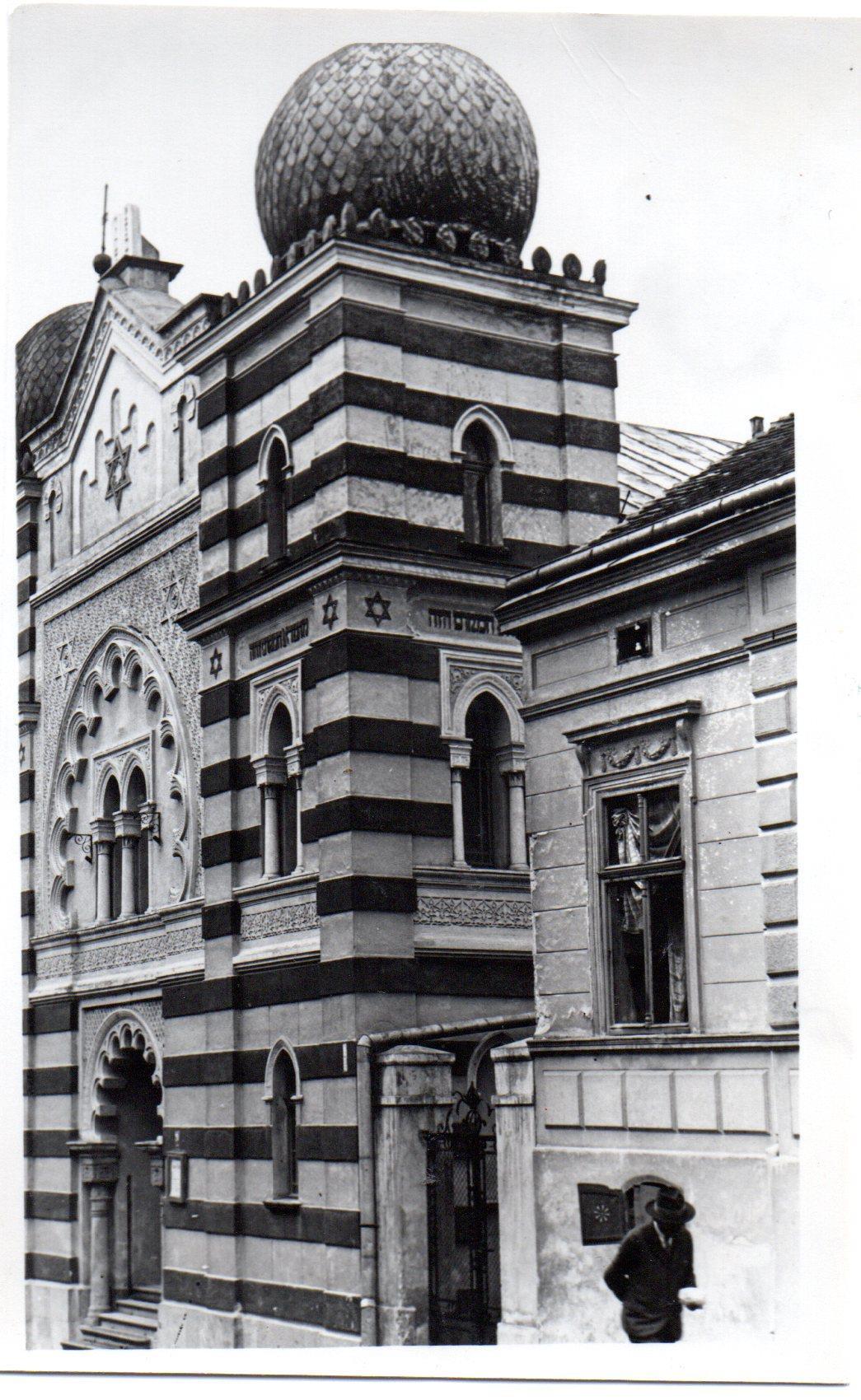

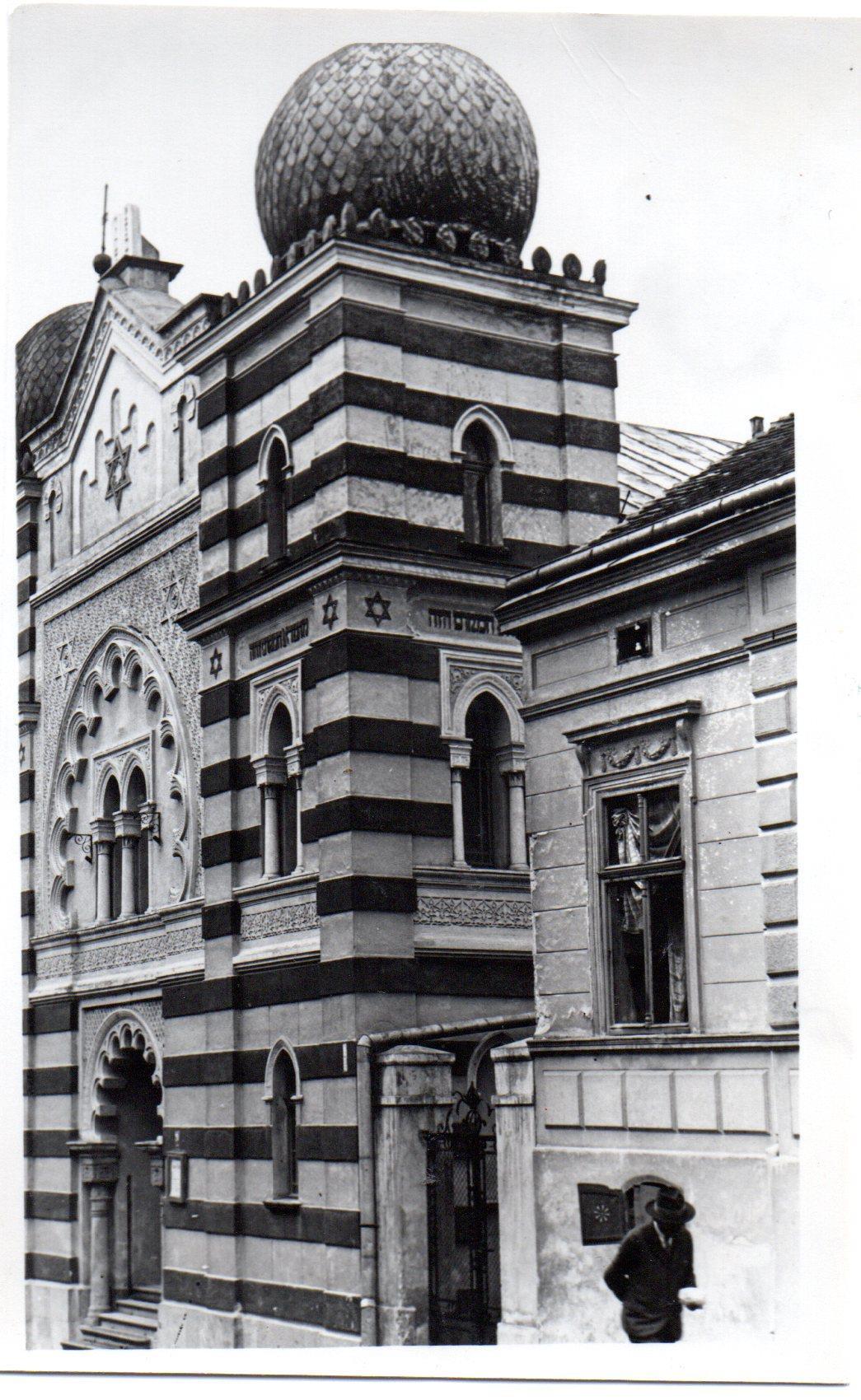

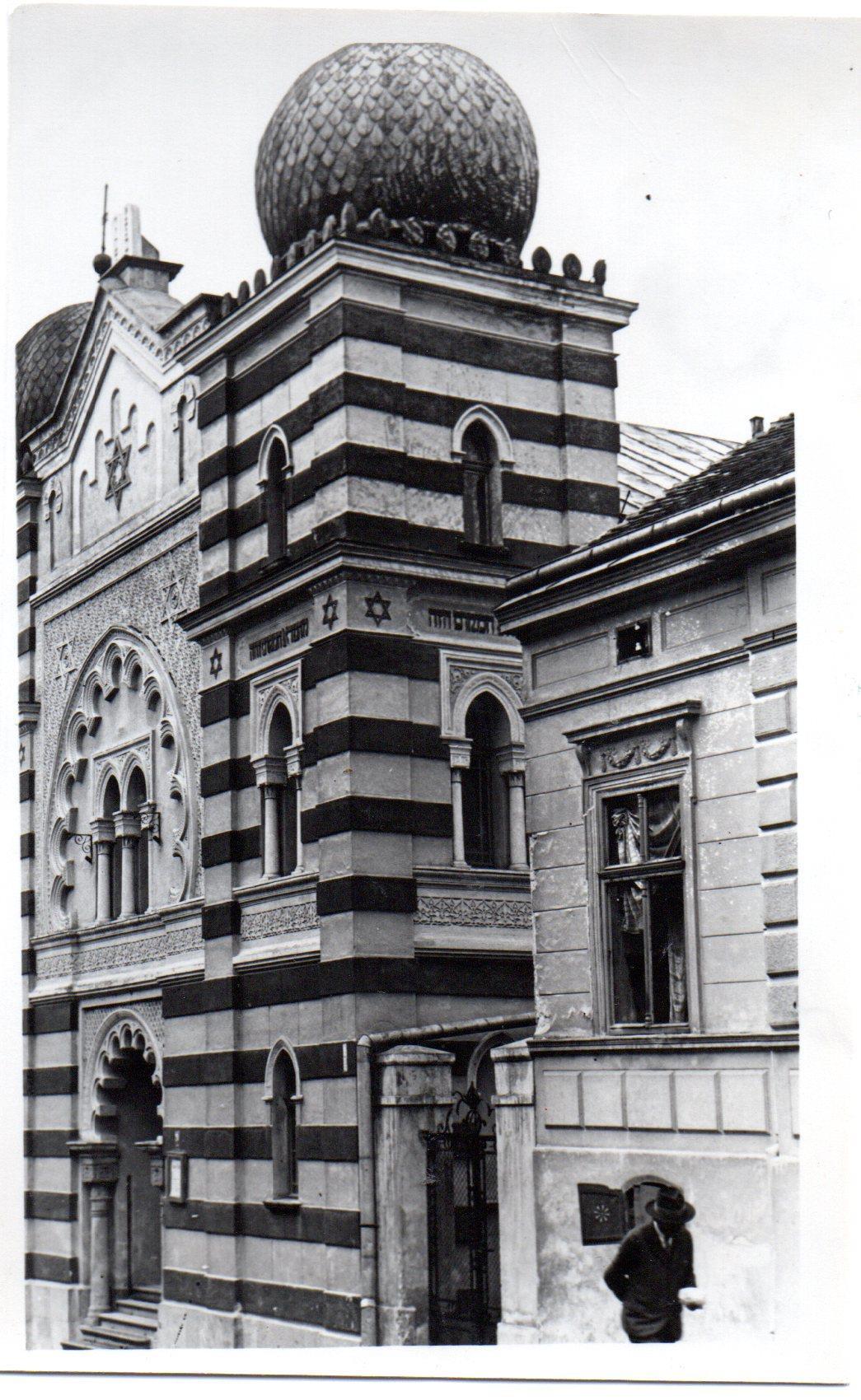

It was built between 1904 and 1905. It was built according to plans by the architect Kuning. With the construction of the Drina Bridge, Višegrad became an important bridgehead between Serbia and Bosnia, which favored the settlement of Jewish merchants and led to the development of a separate community.

For this reason, the city's Jewish population is repeatedly addressed in Ivo Andrić's historical novel The Bridge on the Drina (1945), which traces the history of the bridge and the city. It received its own synagogue, which was considered decrepit at the beginning of the 20th century, which is why the decision was made to build a new one.

Postcard issued around 1905, showing the Visegrad Synagogue on the far left.

Architecturally, the new place of worship closely resembled a church, with two towers flanking the main entrance, above which was a rosette window with a Star of David. Above it rose the pediment, which was connected to the towers by a cornice.

As in the Ashkenazi synagogue in Sarajevo, the towers were topped by small domes, so their tops were also designed in a polygonal shape.

After World War II, the synagogue building was converted into a fire station. Since 2013, a plaque on the building commemorates this former use..

Large windows characterized this upper polygonal area. The main hall had four axes of windows.

As with most Sephardic synagogues, a two-story solution was chosen in Višegrad, where women and men could pray separately. According to the 1903 plan, a wide staircase led to the main entrance. Today the building is only preserved in a very reduced form. The main front is presented without the towers, but you can still see the lower part of them protruding from the facade. The pediment with the cornice and the windows of the main façade are also missing. The height of the entrance door has also been reduced.

Postcard from the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes from 1920 sent from Tuzla to France.

Initially there was a Sephardic Synagogue dating from the Ottoman Empire called Havra, later a small Sephardic Synagogue was built in 1936 and confiscated by the state in 1950. Now it is a dry cleaner. The Ashkenazi Synagogue, demolished in 1955, was built in 1902.

Il Kal Grande, also spelled Il Kal Grandi (JudeoSpanish: The Great Synagogue) was the place of worship for the Sephardic community in Sarajevo, Bosnia.

The great synagogue was built in the Moorish style in 1930, by the Croatian architect Rudolf Lubinski.

On April 17, 1941, Sarajevo was occupied by the German Wehrmacht and that same year the synagogue was destroyed.

The synagogue was inaugurated in 1932 and was considered the "most ornate" synagogue in the Balkans, it was built by the Sephardic Jewish community of Sarajevo, who originally settled in Bosnia in 1565 after the expulsions from Spain.

The synagogue was immediately destroyed by German, Croat, and Bosnian Muslim forces after the occupation of the city, according to Leni Yahil in The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932-1945.

Bosnia and Herzegovina was annexed by the newly independent Croatia.

In Sarajevo in the former Sephardic Jewish center was captured by the Germans on April 17, 1941.

Postcard circulated in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in 1931 showing the city of Sarajevo and the Il Kal Grande Synagogue on the far right

But the disaster occurred from the first days of the German occupation, with the burning of the synagogue by German troops and local Muslims.

Postcard circulated by the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1932 showing the courtyard of the Il Kal Grande synagogue.

Postcard circulated in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1936 showing several panoramic views of Sarajevo, in the fourth box the Il Kal Grande Synagogue is observed

Postcard circulated in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1937 showing the interior of the IL Kal Grande Synagogue

Postcard circulated in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1938 showing the city of Sarajevo and the Il Kal Grande Synagogue on the far left

Circulated postcard of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1947 showing the city of Sarajevo and the IL Kal Grande Synagogue in the center

Circulated postcard of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1949 showing the city of Sarajevo and the IL Kal Grande Synagogue in the center.

It is a Jewish humanitarian organization based in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. During the siege of Sarajevo in the 1990s, the organization provided medical assistance, food rations, and educational services for people trapped in the city. The history of La Benevolencija, however, begins in 1892, after the Austro-Hungarian Empire occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The original goal of La Benevolencija was to raise funds so that Bosnian Jewish students could attend better universities in other parts of the Empire.

Because the levels of antiSemitism were relatively lower in the Balkans than in other parts of the Empire, associations of this kind could be established.

The Zenica Synagogue was built in 1903 by the Sephardic community, when Bosnia belonged to the AustroHungarian Empire, it is located at 1 Jevrejska St., the style is Neo-Moorish.

It was transferred to the municipality in 1960 in exchange for two apartments and is used today as a city museum.

The transaction appears to have been a legally binding agreement initiated by the impoverished Jewish community, which currently has no right to the construction.

Although the history of the Jews in Bosnia and Herzegovina dates back to the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492. Jews did not settle in Zenica until 1750. Most of these early settlers were Sephardic Jews.

They were joined in 1878 by Ashkenazi Jews from Austria-Hungary.

By 1885, the community had built a synagogue next to the local bazaar and a Jewish cemetery on the outskirts of town.

The current synagogue building was built between 1904 and 1907.

In 1910, the Jewish community in Zenica numbered 297, with around 200 living in the city on the eve of Nazi Germany's invasion of Yugoslavia.

185 members of the Zenica Jewish community were killed in the Holocaust. Those who returned home after the war were unable to rebuild the synagogue building it had been demolished, so the building took on other functions.

Zenica Ironworks used the building to house its print shop, and in the 1960s the building housed a furniture store.

In 1968 the Jewish Community of Yugoslavia reached an agreement with the city to convert the building into a local museum. Postcard circulated in Zenica in 1982

He became chief rabbi of Sarajevo in the year 1815. His piety would have made him an outstanding rabbi, however his fame and significance derive from a series of events that began shortly thereafter and culminated in 1819.

Which can be summed up as the release of a group of Jews who were to be unjustly executed.

Many Jews attributed the liberation of the Jews by their Muslim neighbors to divine intervention thanks to the saintly rabbi.

In 1830, Rabbi Danon himself decided to show his gratitude to the Almighty by making a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. However, he did not go beyond Stolac, where he died and was buried in the current Jewish Cemetery.

Rabbi Danon's tomb consists of a monumental stone in the old Bosnian Jewish style known as "seated lions", the most famous examples of which are found in the Sephardic Cemetery in Sarajevo.

In Hebrew Haggadah is: ",הדגהnarration or speech" is a term that comes from the Hebrew root ,ד"גנclosely connected in turn with the verb (דיגהלlehagid), whose meaning is both 'say' and 'instruct’ .

The Haggadah is read during the celebration of Passover, this text refers fundamentally to the slavery of the Hebrews in Egypt and the epic that led to their liberation from such a condition, making them a free group with their own national identity and provided with law .

A Hagada may incorporate legendary stories or tales, including biblical characters and episodes.

In Hebrew the term Hagada usually means fable or legend, with its stories, parables and proverbs, natural science text and even metaphysical court, all Hagada pursues a didactic purpose.

The Sarajevo Haggadah (1350) belongs to the Sarajevo Museum in Bosnia Herzegovina.

It is an illuminated manuscript that contains the traditional Hebrew text typical of all haggadah and that is read during Pesach or Jewish Passover.

It is a Sephardic haggadah that was carried out in Barcelona in 1350.

The Sarajevo Haggadah is a masterpiece of Sephardic art. It is a manuscript on parchment bleached and illuminated with copper and gold.

First Day cover issued by Yugoslavia in 1986 showing the Sarajevo Haggadah

Contains 34 pages of illustrations of key scenes from the Bible, from the Creation to the death of Moses. Some pages are stained with wine, evidence that it was used in many Passover celebrations.

The Sarajevo Haggadah has often been close to destruction.

Historians believe that it was removed from Barcelona by Spanish Jews when they were expelled by the Edict of Granada in 1492.

Marginal notes in the Haggadah indicate that he was in Italy in the 16th century.

It was sold to the National Museum in Sarajevo in 1894 by Joseph Kohen.

Stamp issued in 1986 by Yugoslavia

During World War II, the manuscript was hidden from the Nazis and the Ustaše by the museum's chief librarian, Derviš Korkut, who risked his own life, illegally taking the Haggadah out of Sarajevo. Korkut gave it to a Muslim cleric in a village near the Bjelasnica mountain, where it was hidden under the wooden floorboards of a mosque or a Muslim's house.

In 1992, during the Bosnian War, the manuscript survived a robbery at the museum and was discovered on the ground during a police investigation by local inspector Fahrudin Čebo, along with many other items the thieves believed to be worthless.

During the siege of Sarajevo by Bosnian Serb forces (the longest siege in modern history), the Haggadh survived in an underground bank vault.

There were rumors that the government had sold it to buy weapons; the president of Bosnia showed the manuscript to the community in 1995 to disprove it

by

was

was

in

through

in

with

an

The story of Derviš Korkut, who saved the book from the Nazis, was told in an article by Geraldine Brooks in The New Yorker magazine.

The article also tells the story of the young Jewish woman, Mira Papo, whom Korkut and his wife hid from the Nazis while guarding the Haggadah.

In a twist of fate, the elderly Mira Papo, living in Israel, sheltered Korkut's daughter who was expelled from Pristina during the Bosnian war in 1999 by fostering her in Israel.

Postcard circulated in 1997 from Sarajevo, Bosnia Herzegovina to Zagreb, Croatia

A copy of this Haggadah was given to Tony Blair, when he was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, by the Grand Mufti of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Mustafa Ceric, during a Tony Blair Faith Foundation ceremony in December 2011.

The Mufti presented it as an interreligious symbol of cooperation and respect, highlighting the two occasions in which the Jewish book was protected by Muslims.

Another copy was given to a representative of the Chief Rabbinate of Israel during the interreligious meeting "Living together is the future" organized in Sarajevo by the Community of Sant'Egidio.

Every year on Passover, Jewish families from around the world gather to celebrate and commemorate the exodus from Egypt.

that

It was the largest extermination camp in the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) during World War II.

The camp was established by the Ustachá (ustaša) regime in August 1941, and was dismantled in April 1945.

In Jasenovac, the largest number of victims were Serbs, whom Ante Pavelić considered the main opponents of the NDH.

Jews, Slovenes, Gypsies, Bosnian Muslims, Communists, and a large number of Tito's partisans also perished in the camp.

Stamps issued by the Serbian Republic of Krajina in 1995

Cover circulated in Beli Manastir in the Serbian Republic of Krajina to Bern, Switzerland in 1996

Map of the Serbian Republic of Krajina that existed from 1991-1995, the area of Eastern Slavonia was incorporated into Croatia in 1998

Map of Eastern SlavoniaCover circulated in Beli Manastir in the Serbian Republic of Krajina to Bern, Switzerland in 1996

From its creation in 1941 until the evacuation in April 1945, the Croatian authorities murdered thousands of people in Jasenovac. Among the victims were: between 45,000 and 52,000 Serb residents of the so-called Independent State of Croatia; between 8,000 and 20,000 Jews; between 8,000 and 15,000 Roma (Gypsies); and between 5,000 and 12,000 Croats and Muslims, who were political and religious opponents of the regime.

Croatian authorities murdered between 330,000 and 390,000 Serb residents of Croatia and Bosnia during the period of Ustaša rule; more than 30,000 Croatian Jews were murdered in Croatia or at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Between 1941 and 1943, the Croatian authorities deported Jews from all over the so-called Independent State to Jasenovac and shot many of them at the nearby killing sites of Granik and Gradina.

The estimates given above are based on the work of various historians who have used censuses and any other documentation available in the German, Croatian, and other archives of the former Yugoslavia.

During the Croatian War of Independence (1991-1995) Croatian forces systematically bombed Camp Jasenovac, destroying the museum and archives concerning the camp.

Jewish survivors and war veterans denounced to the international community what they considered "the devastation of all documentation relating to the genocide."

The Yugoslav government denounced these events to the United Nations, considering that its objective was "to erase the scene of the worst crime of genocide that occurred in the Balkans from historical memory."

Interesting production of postcards about the Jasenovac concentration camp published between 1969-1986 by the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia that existed between 1945-1992

Postcard circulated in 1977 by the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia which existed between 1945-1992 showing the Krapje mass grave

The first Jews established in Macedonia were the Romaniotes in the 4th and 5th centuries.

From 1492 the Sephardim were the dominant group, especially in Monastir, today called Bitola.

During the 1903 revolts against the Ottoman Empire seeking independence, he led political violence between Serbs, Greeks, and Bulgarians for seizing Macedonia.

The Monastirlis in the first decade of the 20th century began to emigrate to America, Israel and Thessaloniki.

Macedonia was annexed to Bulgaria in April 1941. Immediately the Jews of the region were subjected to discriminatory laws.

Already at the end of 1941, negotiations had begun between the Germans and the Bulgarians regarding the deportation of Jews to the extermination camps.

In September 1942 they were forced to mark their houses and businesses and those over 10 years of age were forced to wear a Star of David on the left side of their chest.

In 1943, the 3,276 Jews of Monastir were deported to Treblinka and none survived..

At the beginning of the 20th century, around 11,000 Jews lived in Monastir (Bitola).

With the immigration before the First World War (1914-1918) around 5,000 Jews lived. At the end of the war in 1918 there were around 3,000 Jews.

Between 1920-1930 about 500 Jews emigrated to Israel.

In April 1941 Germany invades Yugoslavia and Bulgaria occupied Macedonia, they took the Jews to the Skopje concentration camp and from there between March 22-29, 1943 they were transferred to Treblinka, none of the 3,276 deportees survived.

First day cover issued in 2018 commemorating the 75th anniversary of the deportation of the Jews from Macedonia

Stamp issued in 2018 commemorating the 75th anniversary of the deportation of the Jews from Macedonia

Postcard showing old jews in Macedonia around 1919

The first written records of the presence of Jews in Belgrade date back to the 16th century, when the city was under Ottoman rule.

At the time, Belgrade had a strong Ladino speaking Sephardic Jewish community, mostly settled in the central Belgrade neighborhood called Dorćol. The Jewish community in Belgrade especially flourished in the 17th century when Belgrade had a yeshiva (a Jewish religious school).

A beautiful Sephardic synagogue from the early 20th century, then one of the most prominent buildings in the city, stood on today's Cara Uroša street complete with ritual baths. Before World War II, some 12,000 Jews lived in Belgrade, 80% of whom were Spanish or Ladino speaking Sephardim, and 20% were Yiddish speaking Ashkenazim.

Most of the Jewish population of Serbia was exterminated during the German occupation, and only 1,115 of Belgrade's twelve thousand Jews survived. There were three concentration camps for Jews, Serbs and Gypsies in the city at the time. The Belgrade Sephardic Synagogue built between 1905 1908 in Moorish style was destroyed in 1941 by the Nazi occupation forces.

Postage stamp issued by Yugoslavia in 1968

Nicknamed Čiča Janko (Чича Јанко or Uncle Janko) was a prominent Yugoslav communist politician and intellectual of Sephardic Jewish origin.

He was a close associate of Josip Broz Tito, former president of socialist Yugoslavia, and belonged to the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts.

He was born on January 4, 1890 in Belgrade (Kingdom of Serbia). After finishing primary and secondary school in 1905, he attended the Belgrade art school until 1910, and continued his art studies in Munich and Paris, after which he returned to Belgrade as an art teacher.

In his youth, Pijade was a painter, art critic and publicist. He was also known for translating Karl Marx's Das Kapital into Serbo-Croatian. He is credited with great influence on Marxist ideology during the old regime in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

In 1925, he was sentenced to fourteen years in prison for his "revolutionary activities" after the First World War.

During his stay in Lepoglava prison he met Josip Broz Tito, whose assistant he became.

University in Zagreb on postcard circulated in

He also served time in Sremska Mitrovica, where he met and befriended Samuel Polak, another prominent Yugoslav Jew. Released after fourteen years in 1939, he was imprisoned again in 1941.

In World War II and after the Invasion of Yugoslavia by the Axis Powers, he was known as the creator of the so-called "Foča regulations" (1942), which described the foundation and activity of the liberation committees in the liberated territories during the war against the Nazis.

In November 1943, before the second congress of the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia in Jajce, he initiated the founding of Tanjug, which would become the state news agency of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and later of Serbia.

Sheet of stamps issued by Yugoslavia in 1982

50 years of the FOCA regulations

Pijade held high political positions during and after World War II, and was a member of the Central Committee and the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. He was one of the leaders of Tito's partisans and was later proclaimed the People's Hero of Yugoslavia.

He was one of the six vice presidents of the Presidency of the Yugoslav Parliament (deputy head of state) between 1945 and 1953.

During the sixth congress of the PCY, held in Zagreb in November 1952, he was in favor of a decentralization of control of the industry by the Yugoslav government, within the socio-economic transformation of the country.

After having chaired the legislative commission of Parliament, he was Vice President (1953-1954) and President of the Yugoslav Parliament or Skupstina (1954-1955), as well as political adviser to Tito.

He died in Paris in 1957, while returning from a visit to London, where he had traveled as the leader of a Yugoslav parliamentary delegation.

After his death, numerous streets and institutes in the former

Yugoslavia bore his name. He is buried in the "Tomb of National Heroes" in the Kalemegdan, alongside Ivo Lola Ribar, Đuro Đaković and Ivan Milutinović.

First

Pijade

stamp

Pijade is considered one of the most important theorists of Marxism in the former Yugoslavia.

In the last years of his life, some articles were added to his decentralizing proposals in economics in which he questioned the importance of Soviet aid to the partisans in their uprising against the Axis occupation in Yugoslavia.

He studied music in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and in Prague, where he obtained his Ph.D. in musicology, he worked as a conductor in Sarajevo.

After World War II he became director and conductor of the Belgrade Opera (1944–1965) and principal conductor of the Slovenian Philharmonic Orchestra (1970–1974).

He comes from a bourgeois Jewish family. His father, who graduated from the Vienna business academy, owned manufacturing workshops in Sarajevo, which were taken from him in 1941 when the NDH government was established. Oscar Danon's mother, Hani Danon, played the piano so he grew up surrounded by music at home He attended the First Men's Gymnasium, where he met left-wing professors very early, and participated in the activities of the socialist youth and in the work of the "Youth" literary circle. In 1928 he founded the first jazz orchestra, "Bobby jazz", in which he played the piano.

In the seventh grade of high school, Anka Ivačić, a teacher who later married the writer Hamza Huma, taught him music. In the choir conducted by Anka Ivačić, Oskar Danon played the piano, until Professor Ivačić asked him to replace her as director. Those were his beginnings as a director. Subsequently, a mixed choir was formed with the female students of the Girls' Secondary School, to tour the former Yugoslavia during the summer.

First day cover

They performed works by Mokranjec, Slavenski, Gotovac, recited Kranjčević, Zmaj, Šantić... In Makarska, Croatia, the professor and composer of the Prague Conservatory, František Picha heard him and became very interested in him. When she had to decide where to study, she came to Sarajevo with Oskar's father and insisted that he go to Prague to study music.

There were a significant number of Yugoslav students in Prague at the time, who soon took part in social and political life. At that time, the students of Yugoslavia were divided into two groups: one was socialist, while the other was pro-regime and nationalist in orientation.

in 2013

The former grouped around the association of Matija Gubec, to which Danon also belonged, and the Association of Technical Students, while the others, with a right-wing tendency, joined the Serbian cooperative or the Croatian cooperative.

In 1938, in Prague, after the graduation concert with the Conservatory orchestra, he defended his doctoral thesis on the subject of Claude Debussy and musical impressionism, the beginning of the decadence in music, with which he obtained his PHD.

After April 6 and the collapse of Yugoslavia, all the leftists gathered around the Collegium had to go underground due to secret police lists containing their names.

As soon as the government of the Independent State of Croatia was established, trustees were introduced to all shops in Sarajevo that were in Jewish and Orthodox hands. One of the largest stores of Oskar's father was assigned to the Mešinović family.

After the war, the store next to the Hotel Centrali was taken from the parents and handed over to the director of the Napredak Croatian singing company, Ivan Demeter, who, according to Oskar's brother, participated in the expulsion of his parents from your apartment in the center of Sarajevo. The parents lived as tenants with a Muslim family who kindly took them in and allowed them, disguised in Muslim costumes, with the help of their father's nephew, to escape the Ustasha pogrom and move to Italy via Split and Mostar..

In 1955, as part of a full Russian opera recording project with Decca and the Belgrade National Opera, he directed Prince Igor, Eugene Onegin and A Life for the Tsar at the Dome of Culture. With the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in London he recorded works by Smetana, Enescu, Dvořák, Rimsky-Korsakov, Prokofiev, Stravinsky and Saint-Saëns for Reader's Digest in 1962-63.

He participated in anti-war protests in Sarajevo in the 1990s when sniper fire was opened on assembled protesters. He was in Sarajevo at the time. Managed to leave Sarajevo on the last flight from Sarajevo to Belgrade..

Since 1992 he lived in Baška on the island of Krk in Croatia. He remained a staunch opponent of the Nationalists and, by his own admission, was a ” YUGONOSTALGIC”.

According to his recollections, recorded by Svjetlana Hribar, the biographical book "Rhythms of Riots" was published in 2005. In September 2008, he was elected to the Bosnia and Herzegovina Academy of Sciences and Arts. He died in Belgrade in December 2009

Law graduate, painter, academic and participant in the national liberation struggle.

He is one of the important representatives of social realism in Yugoslav art between the two world wars. His entire family (five of Baruch's brothers) were killed in World War II and the Holocaust. In Paris, he joined a group of communist students and in 1935 he was accepted as a member of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia.

During the Spanish Civil War, he participated in the admission of Yugoslav volunteers into the Spanish republican army and organized their transfer to Spain.

In August 1941 he joined the National Liberation Army (NOV) as commissar of the Kosmaj partisan detachment and later of the Valjevo partisan detachment.

In Serbia he joined the partisan detachment of Suvobor but at the end of February 1942 he was captured by the Chetniks, who handed him over to the Germans, and they shot him on July 4, 1942 in Jajinci.

A street in Belgrade since 1946 is called Baruh Street.

In this way, tribute was paid to the suffering of a revolutionary family from Belgrade. A primary school was opened in Dorcol called the Baruch Brothers, there are many commemorative plaques in the capital that include the names of members of the Baruch family.