THE PEOPLE BEHIND THE WALL

e Soviet Union has returned—not in structure, but in spirit. Russia has resumed its efforts to consume and control Europe and Asia. As we learn more information about the situation and events continue to unfold, it will be ever more important to look back at how Russia’s control has impacted nations in the past, and how those e ects altered the lives of the people within them. It’s easy to consider the big picture and politics, but the biggest and most lasting impacts were not those that involved territory maps, government leaders, or statistics too large to comprehend.

ey came from individuals. e unique stories and lives of the many millions who lived within and without the Soviet Union’s grasp are what need to be understood by those who wish to be cognizant of current events. Statistics and numbers convey very little information about the human experience compared to the memories of those who experienced the Cold War in Germany rsthand. By seeing through their eyes, we may gain insight into the consequences of Russia’s con ict with Ukraine today.

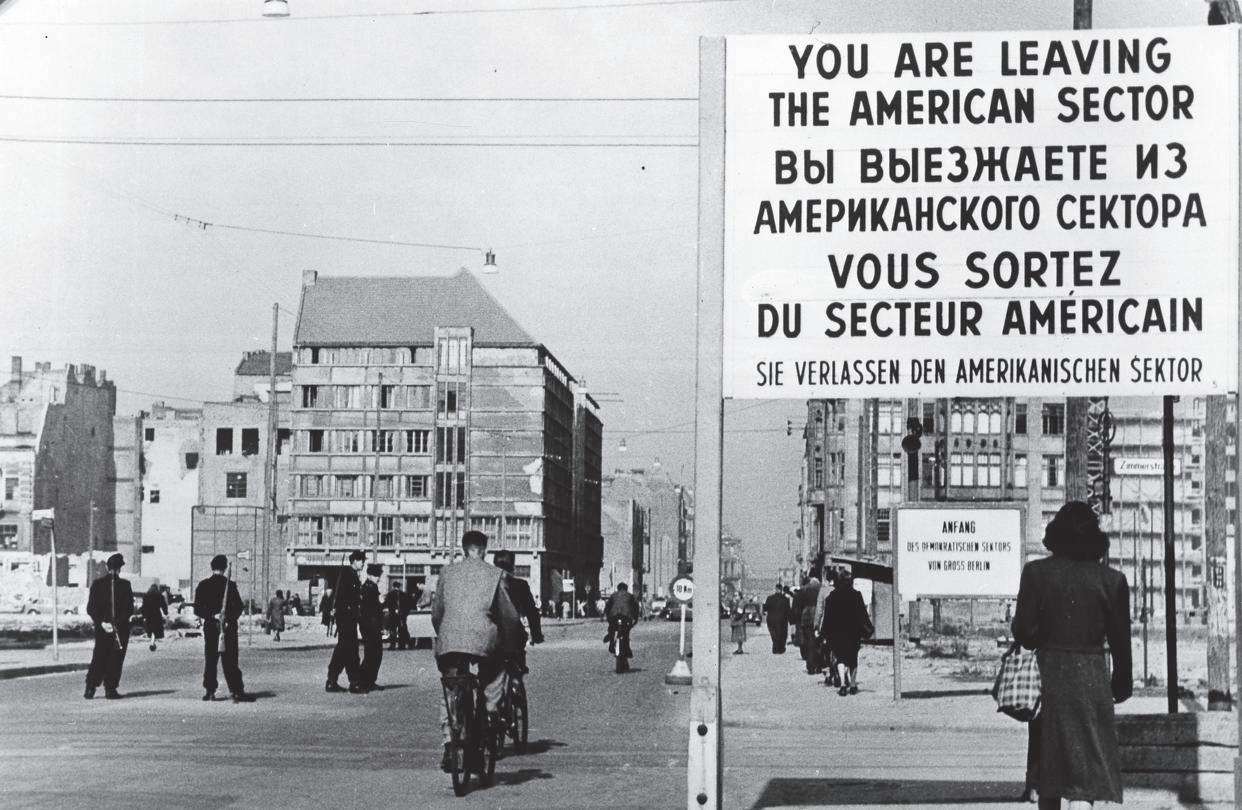

For context, a er World War II had ended, control over Germany was divided up between the main powers who won the war. e United States controlled the south of Germany, France took the south-west, Great Britain took the northwest, and the Soviet Union took a large portion of the east.

e three segments of West Germany remained united with control, laws, and management being shared between the powers. While the West German half more or less shared the values of western democratic society seen elsewhere in Europe then and in most of the world today, East Germany took on the communist ideals and systems of the Soviet Union.

East and West Germany were split up and cut o from each other by the Iron Curtain, and East Germans were forced to live under the laws and restrictions of the USSR, blocking travel or communication to or from the outside world. e capital city of Berlin was also divided, being famously split by the Berlin Wall. Berlin was completely surrounded by East Germany, so West Berliners were only allowed to enter or leave through three routes walled o from East Germany. e USSR ensured that no easterners could see what was happening in the West, and vice versa.

In East Germany, information was limited and highly controlled. Caroline Raynaud described how her parents, both teachers in East Berlin, expressed disdain over the material they had to teach. “ ey were just basically supposed to follow the rules of the regime and tell people that communism and socialism was the right way to go.” Lies were distributed as truth. Teachers had to tell about how “bad” it was in the West, and how everybody was well fed and lived in prosperity in the East, even if they did not believe it.

Even discussion amongst each other about what was going on was taboo. Raynaud continues, “People were really nervous about what they were allowed to say in school, even to their friends, because you never knew who else was listening.” East Berliners had to keep their thoughts to themselves, for they could not know who did or did not support the system. ey either had to believe it or feign belief. ere was constant fear of being monitored. Caroline recalls “hearing stories of the kids mentioning that their parents had complained about the system at home, and then the parents got arrested.” People had to be extremely careful with their words, for they never knew who would turn them in for criticizing the system, even their own children, almost as if straight out of Orwell’s .

While people had to keep their own opinions to themselves, constructed opinions were put into their heads through gaslighting and propaganda. Katharina Lehmann grew up in the town of Lisbon in what was then East Germany and was advertised with anti-west propaganda. “I would say it gave me the impression that West Germany is bad and America is even worse. I had a bad feeling about everything.”

East Berliners weren’t completely in the dark, though. Raynaud’s family was “not allowed to watch any TV from West Berlin, but for most of them it wasn’t actually too di cult to do because they could get it over the antenna. [Many] people would, but they made sure that the curtains are closed [and] the room is dark so that no one knows about it.” ey weren’t supposed to, but they watched western television in secret and learned the news and of what living in the West was like. is silent rebellion of knowledge was what prompted many an attempt to ee to the West.

“ ey planted this fear in my head as a rst grader.”

(Lehmann)

However, movement and travel in or around the East was also heavily restricted, and required complicated protocols even to get into East Germany or Berlin from the outside. In the many checkpoints between East and West Berlin, guards would force all passengers out of their vehicles and strip the cars down in search of stowaways or contraband. ey would pull out the seats, dismantle the trunk, and even crawl underneath to ensure nobody was clinging to the underside of the car. Any items with even a hint of suspicion around them was a danger to have and could lead to incarceration if found. A er moving to the West, Caroline’s mother frequently kept newspapers in her trunk to recycle, and they were discovered once by the inspectors during a visit to East Berlin. “One of the really strict rules was that you were not allowed to bring any ‘western propaganda’ to East Germany. As usual, we stopped at the checkpoint, we got searched as we always did. ey opened the trunk and found the newspapers, and we were immediately escorted into an interrogation room. I was super scared because they took my mom away. ey le me there for a moment. I [was afraid] she would go to jail and we would get arrested.”

Visiting East Berlin as an outsider was di cult, but leaving as a citizen was near impossible. Stephanie Bastian describes her view looking through a hole in the Berlin wall: “You can see through here and in the far, far distance, there’s [the other half of the wall,] and behind that there are buildings. [Between the walls,] there was an area where there was nothing but mines and explosives. [...] People here o en think ‘I mean, it’s a wall you can just climb, jump over and you’re done.’ It wasn’t just one wall. It was a whole Death Strip, as they called it, with two walls on either side and only from the one side, from the western side, was it spray painted like this.” e Berlin wall was far more than the single wall covered gra ti that many take it for. It was an entire eld of no man’s land lled with mines and with guard towers positioned to snipe anybody running across the wide open space below.

ese conditions extended all the way up until 1989, when the Berlin Wall border was reopened and travel between the sides resumed. Today, Germany remains whole, and is no longer under the control of the Soviet Union. However, Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine leaves us with the potential for history to repeat itself.

Matt Juliano is a Freestyle Academy Film I student with a strong passion for the subject. A great lover of making and watching movies, notably and , Matt also enjoys video games, LEGO modeling, and cuddling with Penny, Nickel, And Dime, the family cats!