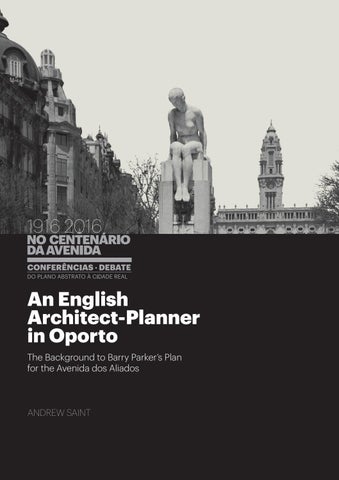

An English Architect-Planner in Oporto The Background to Barry Parker’s Plan for the Avenida dos Aliados

ANDREW SAINT

An English Architect-Planner in Oporto The Background to Barry Parker’s Plan for the Avenida dos Aliados

ANDREW SAINT

1 Barry Parker, Raymond Unwin and the Parker family, c.1898. Unwin and Parker stand respectively on the left and right at the back. [Garden City Collection, Letchworth]

Oporto is famous for its two unique architectural memorials of the

Intelligent and conscientious young men and women reacted to these

historic links between Britain and Portugal in the shape of the Feitoria

deeply problematic Victorian cities in a variety of ways, by working to

Inglesa and the Hospital Santo Antonio. The ultimate explanation for

reform them, dilute them or even escape them. This anti-urban re-

their existence is the strong trading links between Porto and Britain or,

form movement in Britain was not initiated by architects or the kinds

to put it in a harsher way, Britain’s economic dominance in the eight-

of people whom we now call city planners or urbanists. City planning

eenth century, and its control of the highly prized port wine trade.

in the way we understand it today didn’t yet exist. In all British cities,

The story I have to tell, of how the English architect Barry Parker came in 1915 to make the first concerted attempt to plan the great central axis in Oporto that became the Avenida dos Aliados is more curious and less logical, because there is no external link like the port wine trade to explain how or why it happened. Indeed on investigation there was a curious innocence about the venture both on the part of the local authorities who invited Parker over to advise on their city plans, and on the part

especially those that had grown fast in the nineteenth century, urban government was weak, and the control over development correspondingly weak. Before 1900, many European cities managed their growth by laying out an area beyond the existing city walls to the design of the city architect. But in Britain that was seldom the case, because the cities seldom had any walls and the land in question was not under public control. A place like Sheffield would not have had a city architect at all.

of Parker who had little experience of urban life in Britain, let alone Por-

The anti-urban movement in Britain grew strong and widespread in

tugal. In the end, not a great deal came out of the initiative. Even so it is

the second half of the nineteenth century. It became a tree with many

remarkable that things went as far as they did, accompanied through-

branches. It attracted both conservatives who believed that old rural

out by the amity that traditionally marks Anglo-Portuguese exchanges.

values and traditions had been eroded, and radicals who wanted to see

Who exactly was Barry Parker, where he came from, and how did he come to have the status which led to his invitation to Oporto? He was born in 1867 in Chesterfield, an English Midlands town with a population then of about 30,000, today about three times that size. Ches-

the lives of the rootless and restless urban working classes transformed. Engels famously wrote about the appalling conditions of Victorian Manchester; William Morris imagined a return to a society of small towns and villages in his utopian News from Nowhere.

terfield was then a mining district, and lay close to a bigger city, Shef-

Not long after News from Nowhere appeared, Ebenezer Howard, a jour-

field, greatest of the English iron and steel centres. Sheffield then had

nalist without high status but a devouring interest in cities, commu-

a population of about 280,000, rather larger than Oporto today. A city

nities and social welfare, wrote his famous Garden Cities of Tomorrow,

with a fine hillside site and wonderful countryside all around, it had all

which first appeared in 1898. The utopian proposals which Howard put

the problems of the great conurbations which had grown rapidly during

forward in that book, about dismantling the big cities and remaking

the Industrial Revolution, with bad slum housing sited next to factories,

society from smaller towns, balanced between town and countryside,

high rates of mortality, much poverty, appalling pollution and a large

were not completely new. The difference was that Howard did not just

immigrant population. It was then the sixth in size among English cit-

write a book, he actually went out and did something about his ideas.

ies, upon which Britain’s economic dominance rested. At the top came

Had he not done so, we would probably never have heard about Barry

London, then the largest city in the world, with just under four million

Parker – and he certainly would never have come to Oporto. That is be-

people.

cause Parker became one of an army of Englishmen who enlisted them-

2 Sketch of an Arts and Crafts interior by Parker, c.1900. [Garden City Collection, Letchworth]

selves in the crusade of trying to make Howard’s seemingly impossible

pean architecture. Their first houses were comfortable small country

ideas work and actually building a so-called garden city.

or suburban homes for the local bourgeoisie. But Unwin from the start

Howard had economic and social theories about how his garden city might function, but did not much care what it looked like. Fortunately he was persistent, he was always open to advice, and he trusted his collaborators. Fortunately too, to design his new little city at Letchworth about 50km north of London, he in 1903 employed the best-equipped young architects he could have found, Barry Parker and Raymond Unwin. Parker and Unwin were brothers-in-law and partners who had then been working together for about ten years (ill. 1). As young architects often are, they were practical idealists. Raymond Unwin was the stronger character and the deeper thinker, and arguably the most influential figure in British architecture and planning during his lifetime, although

was interested in designing schemes of small houses for working people in the mining villages of the area. At that time there was much debate in Britain as to what kind of housing ought to be built. Some urban blocks of flats were being built in the big cities. Though ugly and bleak, they were usually quickly occupied because they were near places of employment, and working people could not afford to live far from their work. But many reformers thought it was preferable to provide people with their own suburban houses or cottages and gardens, and subsidise the costs of transport so that they could lead healthier home lives and commute to work. Parker and Unwin’s first housing schemes were not in the cities but in

he built no great and famous or monumental buildings. Interestingly

so-called factory villages, where employers were building low-rise cot-

he was less an architect by background than an engineer. Unwin want-

tage housing for their workforce in close proximity to the factory. Some

ed to make architecture socially effective and to spread its benefits,

mining villages had built interesting housing developments of this

and for that reason he concentrated on housing. As a very young man

kind, to regular but unsophisticated plans. But there were two more

back in the 1880s he had worked for William Morris’s Socialist League

famous schemes in England in course of development around 1900,

in Manchester when a socialist revolution seemed to be about to take

one at Bournville outside Birmingham for the Cadbury chocolate firm,

place. After some bitter disappointments he concluded that the right

and the other at Port Sunlight near Liverpool for W. H. Lever, the soap

course of life for an active socialist was not to agitate politically but to

magnate. These so-called factory villages came as near to a new kind

promote practical, technical reforms and so gradually improve the lot of

of urbanism as anything built in Britain in the nineteenth century. Too

the working classes. In the 1890s he teamed up with Parker, who came

small to be cities, they were fairly self-sufficient communities, though

from a large Quaker family with strong moral and aesthetic views, and

not balanced ones, as they depended on a single beneficent employer

married his sister. Together they began to design houses, with Parker

who owned the housing. Parker & Unwin added another such commu-

providing the elegant touches in the fashionable Arts and Crafts, an-

nity when they got their first important commission in 1902, to lay out

ti-urban idiom, reliant on features derived from traditional English

New Earswick for another employer of the same enlightened kind, the

farmhouses and cottages (ill. 2).

Rowntree confectionery firm just outside the city of York. From New

The two partners first lived and worked in Buxton, a small town in the hills between Manchester and Sheffield. The ethos and focus of their

Earswick they quickly moved on to designing the garden city of Letchworth, where their national and international reputation was made.

early work was as far from big cities as it is possible to imagine, and ut-

At Letchworth the first priority was housing, not civic authority or iden-

terly English. They were equally distant from the mainstream of Euro-

tity or expression, and Parker & Unwin made their plan on that basis.

3 Letchworth, aerial view of the centre of the first garden city, showing detached houses in gardens all around the civic centre at the bottom.

4 Letchworth town centre as proposed, 1912. This scheme was never executed. [Garden City Collection, Letchworth]

Indeed they spent most of their early career focussing on the technical

Around this time urbanism became an international topic, and all sorts of

aspects of small English houses: how they should be planned internally,

exchanges began to take place in Europe and beyond. Hitherto city plan-

what size their gardens should be and how they might be used, how they

ning had taken place in national compartments, with limited exchanges

were to relate to their neighbours, how they should get the most bene-

between countries. The main exception to that was the Franco-Italian

fit from daylight, what should be their boundaries etc. Unwin built up

model of axial urban planning, which had great influence everywhere in

an unrivalled repertoire of knowledge about such matters which can be

the nineteenth century, both in city extensions and city reconstructions.

found in his great textbook of 1909, Town Planning in Practice.

By 1900 the traditions of city development in Austria and Germany

At first Parker & Unwin gave little thought to the civic centre of Letch-

were beginning to diverge from the French boulevard system. German

worth (ills 3, 4). As architects have always found, it is one thing to come up

city-extension plans in particular started picking up the ideas of Camil-

with a grand and impressive geometrical plan for a new city, and a com-

lo Sitte about responding to the character of existing towns. In the

pletely different thing to see it through. People who go to Letchworth

Spanish-speaking world, there was a long tradition of grid planning ex-

today invariably find the centre disappointing, lacking in dignity and

emplified at its extreme by the famous plan for Barcelona by Cerda. The

monumentality, empty even. That is partly because it took so long to

Americans were starting to discuss how to make their young and raw

build, but also because it did not get that much attention. This attitude

cities more beautiful. There was also a lively debate about civic theory,

of getting the housing and the places of employment going and sorting

about the nature, growth and evolution of cities, initiated by the Scot-

out the centre later became standard when the British New Towns de-

tish biologist Patrick Geddes and a whole school of French geographers.

veloped in the post-war period, following Howard’s model.

Suddenly everyone became very interested in what everyone else was

Parker & Unwin soon found themselves engaged in further housing

doing. Barry Parker’s invitation to Oporto is in large part a symptom

schemes when they landed a second prestigious commission, that

of that. As regards Britain, the exchange was in the first instance more

of planning Hampstead Garden Suburb. If Letchworth was the first

one of giving than taking. Because Britain’s industrial economy had

garden city, Hampstead was the first garden suburb. It was an easier

developed earlier than most of its European rivals, its big cities had en-

project, because it was an extension of residential London and didn’t

countered the problems of health and pollution earlier and on a bigger

need all the facilities for employment which Howard had to attract to

scale than its continental equivalents, and solutions to them had been

Letchworth. It was essentially a model housing development with a lit-

debated more intensively too. The garden suburb in particular was of

tle centre of its own, not very ‘civic’, without shops or public buildings,

enormous interest. Experts flocked to London to see Hampstead Gar-

though it did have two churches and a school (ills 5, 6). But because it was

den Suburb and, to a lesser extent, Letchworth. On the whole the dif-

easier, it got off the ground faster. Unwin largely transferred his loyal-

ference between the garden city and the garden suburb got lost when it

ties to Hampstead, going to live there from 1906 while Parker carried on

transferred to Europe, so that the term cité jardin or Gartenstadt came

working from Letchworth. They gradually became more independent of

usually to mean just a particular style of housing scheme made up of

one another. That was important for Parker, who had been living in the

low-rise cottages in the manner of Parker & Unwin. But fairly soon

shadow of his partner, though he always contributed to their ideas and

the French and the Italians embarked on ‘garden suburbs’ made up of

probably dominated the design side.

blocks of flats instead.

5 Hampstead Garden Suburb, part of Parker and Unwin’s original informal layout plan, 1905. [Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust]

6 Hampstead Garden Suburb, perspective sketch of the centre, from Raymond Unwin, Town Planning in Practice, 1909.

The most important of these exchanges, so far as Parker and Unwin

win sets out his technical advice on how to plan housing estates derived

were concerned, was between Britain and Germany. British archi-

from personal experience, these early chapters depend upon his reading

tecture had never enjoyed much continental influence, which is why

and to some extent his travelling, since neither he nor Parker had much

Oporto’s two monuments to English Palladianism are so remarkable. In

experience in laying out town centres. As a result he is more cautious

the 1890s that changed, and British domestic architecture began to be

and tentative about planning cities than about planning housing. Fol-

noticed, particularly through the efforts of the German architect Her-

lowing Sitte, he is also more aesthetic. Like Sitte, Unwin loved best the

mann Muthesius, who spent several years in Britain and wrote three

beautiful small towns of Europe, with their irregular street patterns

books about it. Parker & Unwin came just too late for Muthesius, but

and subtle vistas, and he questions whether their character was due to

he does talk about Bournville and Port Sunlight and about Ebenezer

chance or design. In the end Unwin is reluctant to go along with the

Howard’s book, and mentions that Letchworth is about to be started. A little later a young German architect Ernst May, to become famous for his inter-war housing estates in Germany and Russia, spent time in the Parker & Unwin office studying Hampstead Garden Suburb, and the first of the German equivalents of the concept, Hellerau outside Dresden, was started. But this influence was not all in one direction. Up to about 1904, Parker and Unwin’s work had been entirely insular. After that Unwin began to look beyond England. The catalyst was a book by T. C. Horsfall called The Example of Germany, which analysed the planning laws that set the regulation and extension of the best German cities, and argued for a similar approach in Britain. Unwin went on to read Camillo Sitte, whose book on the aesthetics of towns had been translated into French, but not English. Thereafter he became greatly interested in continental

extreme neo-mediaevalism of some modern German town extension plans with their artificially winding streetscape. He represents himself as balancing between formal and informal beauty, between the axiality and symmetry of the Latin planning tradition and the picturesqueness of the northern tradition. If there is any aesthetic theory of city-centre planning here, it is at the level of generalities. There is also a major omission in Unwin’s discussion of city centres. While he talks about the nature of town centres and plans, he nowhere addresses the issues of replanning city centres. That is what so many nineteenth-century cities had been struggling with, and what Parker had to face in Oporto. All the examples he gives of axial and symmetrical avenues and how they connect with their surroundings relate to new developments like Washington and Philadelphia, not

planning methods. The results are manifest in Town Planning in Prac-

clearance schemes.

tice, which includes layout plans of many German towns, old and new.

In fact the British record in regard to such schemes was undistinguished.

German influences also begin to show in the second stage of Hampstead

The idea of driving a road through the slum area of a city was a very old

Garden Suburb, developed in the years just before the First World War.

one going back to the Rome of the Popes. It had reached its climax in

Sitte’s writings made Unwin think harder about the overall layout of

the nineteenth-century clearance schemes carried out in so many Eu-

towns and city centres. The first third of Town Planning in Practice

ropean cities, of which Haussmann’s Paris is the most famous because

comprises a wide-ranging discussion of the character of cities, going

most extensive example. These were, on the whole, engineers’ schemes

back to the Ancient World and up to the latest German city extension

made palatable by a certain architectural and landscaping finish. They

plans. Quite different from the second half of the book, in which Un-

were often impressive, but they were seldom subtle aesthetically.

7 Rosebery Avenue, London. Typical of the slum-clearance street designed under the Metropolitan Board of Works and London County Council in the 1880s and ’90s.

8 Aldwych, London, c.1910. Improved street-planning of the Edwardian era, with monumental buildings flanking the roadway. [Historic England Archives] .

London’s various nineteenth-century examples of this genre were un-

London. From that moment urbanism, or town planning as the Brit-

impressive and disappointing (ill. 7). They were done on the cheap, and

ish called it, became accepted as a significant international discipline.

Parker and Unwin no doubt knew and despised them. But as interest in

The main organizer of the event was Raymond Unwin, who organized a

urban planning grew, things got better. The main centre-city schemes

memorable exhibition at the Royal Academy to accompany the confer-

in progress when they were practising were the Kingsway-Aldwych

ence, travelling specially to Germany to get material for it.

improvement, carried out on a generous scale and with a classical formality which would not have been to their taste but did at least include some fine buildings (ill. 8); and the reconstruction of Regent Street, where it was more a question of replacing old buildings with bigger, more uniform new ones. We know that Parker looked at Regent Street, because he refers to it in an article he wrote just after he came back from Oporto on the subject of horizontality or verticality in town planning. ‘A modern plan for laying out towns’, Parker wrote, ‘almost always does (and always should) presuppose that either a vertical or a horizontal feeling will predominate in the buildings, and the whole layout should be influenced by the type of building expected or wished for.’ He recognized that horizontal unity was hard to achieve when there was no overall architectural control of the streetscape, and for that reason many architects nowadays opted for verticality. That was not Parker’s way, as his remarkable Oporto plan with its regular insets shows.

There was an impressive turn-out of international delegates at the 1910 London conference – French, Dutch, Germans, Belgians, two Russians, two Spaniards, but no Portuguese. Presumably that was because Portugal was in the throes of its revolution. The final act of revolution and declaration of the republic took place on 5th October, five days before the London planning conference opened. But it is also possible that the conference simply wasn’t known about. Portuguese architectural and planning traditions were still then focussed on Paris, as the career and thinking of Marques da Silva makes clear. Four years later, the outbreak of the First World War caused a brutal rupture, breaking up all constructive discussions and friendships made over planinng questions during the previous decade. For Parker and Unwin life was particularly difficult. Their Quaker and socialist backgrounds meant that they were close to being pacifists. Unwin joined the British Government, first as chief town planning inspector, then as

Ultimately the Avenida dos Aliados is a late example of the nine-

the architect in charge of supplying urgent new housing for munitions

teenth-century genre of clearance schemes, and it has frankly to be said

workers. Parker meanwhile was rather stuck, as work in Letchworth

that neither Parker nor Unwin had practical experience in this special

and elsewhere tailed off. So when the invitation came to advise Porto

genre of work. Up to the First World War they were both so busy with

in 1915, he was probably at something of a loose end. We do know that

housing layouts that central-city planning took up little of their time.

he consulted people as to whether it was patriotic to leave England in

Nevertheless Town Planning in Practice shows that Unwin at least had

the midst of a war, but was told that it was all right because he would

widened his scope to think about cities as a whole, and we can assume

be earning foreign currency for Britain. Portugal had not yet joined the

he probably took Parker with him.

war on the allied side, though Britain was exerting strong pressure for

To revert to the exchanges of ideas about urban planning which took

you to do so. So Parker was actually coming to a neutral country.

place all over the western world in the years before the First World War,

Why Parker, it may well be asked? At a guess, the invitation probably

their climax came in 1910, when the first International Town Planning

went in the first place to the Raymond Unwin, internationally famous

Conference was hosted by the Royal Institute of British Architects in

by 1915, but Unwin was too busy with his wartime responsibilities in

10 Cover of Parker’s Report on Oporto as published in England, 1916.

Britain and passed it on to his old and trusted colleague (ill. 9). In the first instance the invitation must have been limited, as Parker’s wife Mabel wrote afterwards that they expected to be away only two weeks, but the stay lasted four months! That was partly because she fell badly ill from dysentery when they arrived in Porto. The Parkers had two young boys who were left behind with Mrs Parker’s mother in England because their time abroad was supposed to be short, just a holiday really from the grim conditions of wartime England. It turned into an extended stay, with the Parkers having the time of their lives, travelling up the Douro valley at weekends in a car which was lent to them, staying at W. & J. Graham’s port lodge, and behaving like ordinary tourists. A photo album survives showing pictures of life and buildings in Oporto and the region which the Parkers obviously bought there and brought back to England as a souve9 Barry Parker in Oporto. [Garden City Collection, Letchworth]

nir, and it conveys well the tranquillity which they found. But Parker was also working. He and his hosts got on so well that he was quickly drawn deeper into questions of city planning, and instead of just advising, presumably with a view to a competition, he was invited or offered to make a plan for the great avenue to be planned leading up from the station to the projected Camara Municipal (ills. 10, 11). This work became the great preoccupation of his four months’ stay, tackled with great dedication and admiration for Oporto, which Barry Parker came to love. But it was also undertaken with a kind of innocence, as regards not only the local political background which naturally played an important part in this prestigious commission, but also the whole topic of urban renewal, in which Parker had no previous practical expertise. To ask an English architect of Arts and Crafts houses and suburban housing layouts to become the Baron Haussmann of Oporto was a big step. It is almost more surprising that any of his plan was adopted and that the current Avenida dos Aliados bears some traces of his mark than that the project was not rejected in toto.It may be suggested that the Parker plan for Oporto combines loyalty to Unwin’s ideas – or those Parker and Unwin had worked out together – with a certain Italian influence. Parker

11 Plan showing all Parkers’s suggestions for replanning the centre of Oporto, as published in his Report on Oporto, 1916.

12 Detail of the buildings suggested by Parker for the frontages of the future Avenida dos Aliados. [Garden City Collection, Letchworth]

had been to Italy, and like all architects of his time would have loved the planning and early Renaissance architecture of the small towns there, a language which has much in common with Oporto’s vernacular architecture. They seem to coalesce in the sketches of low-key architecture with loggias and exposed roofs which feature in Parker’s plan (ill. 12). Unexecuted planning schemes are always faintly disappointing. No doubt Parker too was disappointed by the outcome of his months of intelligent effort, not just because he wasn’t paid properly – we know

No Centenário da avenida da cidade [On the Centenary of the City´s Avenue] was a joint initiative of the Marques da Silva Foundation and Porto City Council, designed to mark the start of the construction process of Porto´s civic centre, symbolically dated 1 February 1916 Do plano abstrato à cidade real [From the abstract plan to the real city] was the second module of the program, Discussion-Conferences which sought to highlight the importance of the original design for the avenue and its evolution in the specific context of Porto´s culture. Addressing the idea of the Civic Centre in Raymond Unwin´s theoretical concept and the proposal of his colleague, Barry Parker, for the implementation of the city of Porto´s new civic centre.

that because there is a letter of 1918 in the Letchworth archives from the Oporto authorities addressed to Barry Parker ‘engineer’, declining to pay his fees – but also because the Marques da Silva-type architecture which eventually filled the frontages of the Avenida dos Aliados was not of the kind he liked or respected. This was not a case of Britain versus Portugal; Parker would have hated equally most of the urban architecture going up in Britain at the time. At heart he was a smallscale man, more at home when he got a second set of commissions in the Portuguese-speaking world in 1917, and went out to Sao Paulo to plan a series of suburbs for an Anglo-Portuguese company. Some of these did get successfully built, so Parker did leave a minor legacy in the Portuguese-speaking world. If that didn’t happen in Oporto, at least he proved his worth with his fine and elegant report, and he and his wife had a long and happy holiday into the bargain.

Andrew Saint

Andrew Saint’s seminar was given on the 19th September 2016 at Rivoli Theatre (Porto).

ORGANIZAÇÃO

APOIOS

PARCEIRO