BLACK & WHITE MASTER PHOTOGRAPHY

ESSENTIAL TIPS FOR IMPROVING YOUR MONOCHROME PHOTOGRAPHY

178 pagesexpertof advice

ESSENTIAL TIPS FOR IMPROVING YOUR MONOCHROME PHOTOGRAPHY

178 pagesexpertof advice

Black and white photography is having something of a renaissance in our bright and busy modern world – and it’s easy to see why. Stripping away the distraction of colour from a photograph allows you to focus on shapes, textures and patterns, and your subject, whether it’s a dramatic landscape or an intimate portrait. Black and white photography can be enhanced by great editing, but it starts when you’re shooting. For the best results possible, you need to see and feel in Black and white, and use the right gear. That’s where this book comes in! Over the next few hundred pages, we’ll equip you with the skills needed to capture, edit, and master monochrome photos – whether you’re into mindful photography, gritty street shots or fine art wildlife. We’ll cover essential kit, from cameras and lenses to filters and even printers. Then our in-depth technique guides will teach you how to set up your camera to extract every ounce of detail and atmosphere from a scene. We’ll also explore the essential elements you need to consider when composing an image; form, shape, contrast and tone. And let’s not forget some inspirational interviews and case studies from the experts. Welcome to the stunning world of black and white photography. Grab your camera, and get reading!

Future PLC, Quay House, The Ambury, Bath, BA1 1UA

Editorial Editor Lauren Scott

Senior Designer Neo Phoenix

Senior Art Editor Andy Downes

Head of Art & Design Greg Whitaker

Editorial Director Jon White

Contributors

Peter Fenech, Alistair Campbell, Tom Calton, Jeremy Walker, James Abbott, Jon Adams, Helen Trust, Tom Calton, Niall Hampton, Adrian Davies, Andrew James, Angela Nicholson, Lee Frost, Paul Sanders

Cover images Neil Burnell, Tom Calton, Jeremy Walker, Andrew James, Getty Images

All copyrights and trademarks are recognised and respected

Advertising

Media packs are available on request

Circulation Head of Newstrade Tim Mathers

Production Head of Production Mark Constance

Production Project Manager Matthew Eglinton

Advertising

The Black and White Photo Awards is a newlycreated international photography contest designed to recognise and reward talent in the field of black and white photography. The awards are split into five categories; architecture, street, portrait, flora and fauna and landscapes. For more, visit: www.bwphotoawards.com

Far left Cheetah with cubs

This overall winner was shot with a Canon EOS-1D X Mark II and EF500mm f/4L IS II USM lens

Left The artist and his fans

A clever composition shows an array of phones capturing a street artist

Above Great Ridge walkway

This landscape taken in the Peak District got a bronze mention in the competition

“The striking contrasts are what make B&W so dynamic”

Far left Waves

The striking contrasts are what black and white photography so dynamic, as shown in this architectural winner

Far left upper Patterns Of Eid

Repetitive subjects can work well in monochrome – in a way they don’t with the distraction of colour

Far left lower Fan Club

The photographer has focussed on the detailed patterns of the fan with their minimalist entry

Far left bottom La cúpula

The high key image is dominated by bright, white and pure tones to create an almost ethereal feeling

Top left Ramble and roam

Shooting through the arrow has proved to be a clever framing technique in this urban scene

Middle Sea of Sand

A wide panoramic crop and wide angle lens captures the expanse of this landscape effectively

Top right

Backlight horse

Photographing the subject in front of the sun can create a dramatic contrast – what a majestic creature

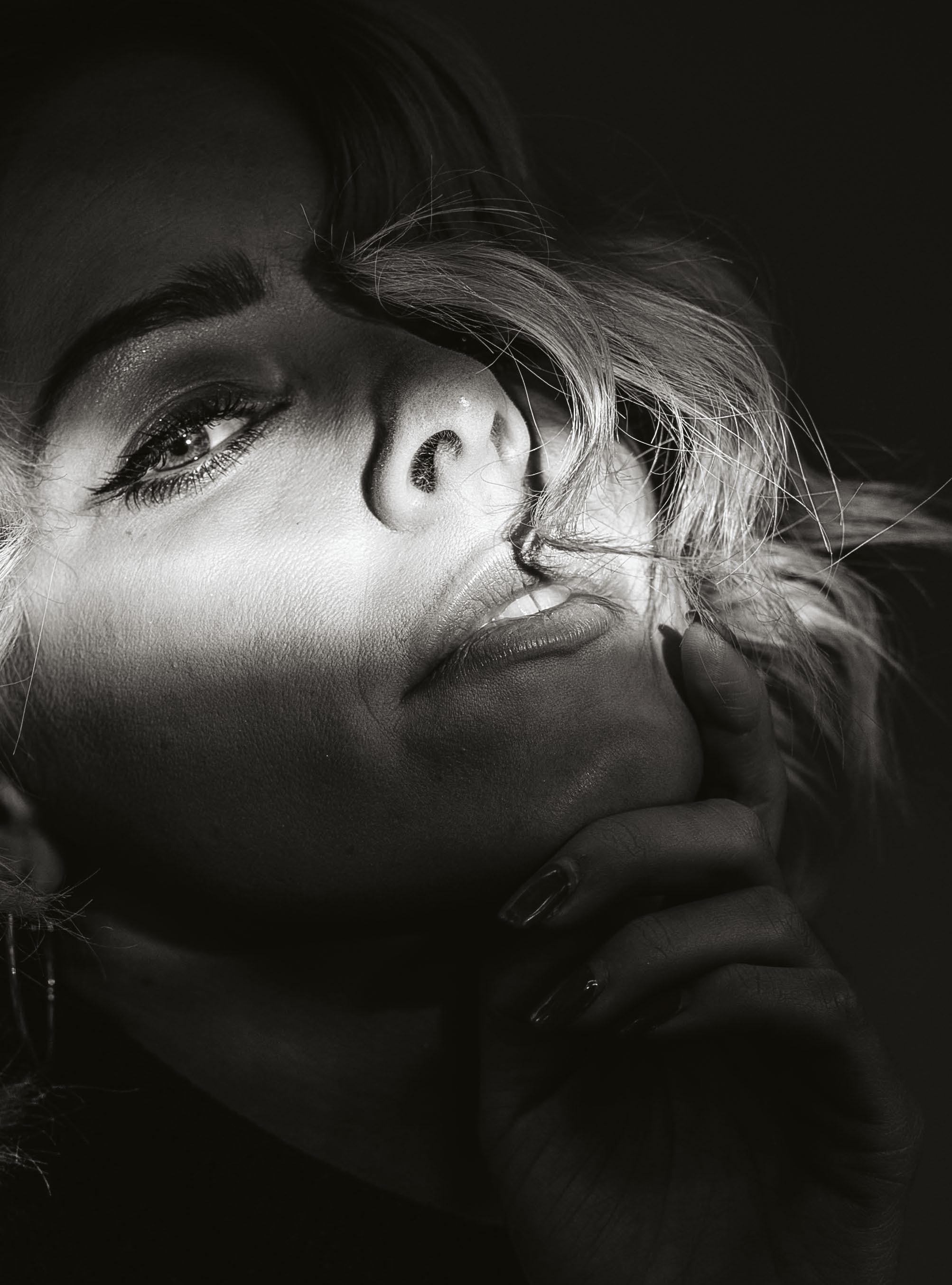

Left Entre luces y sombras retornan sus sueños

A black background can often be a good way of separating the subject in a monochrome portrait

Far left Pattern

Contrasting tones and textures make this body study work so well. The eyes are the most striking part of the image

Left Mobulas in the Mediterranean Sea Rays of light burst through the waters of this impressive atmospheric underwater shot

Left below Posado de girafas

A long 400mm telephoto lens allowed the photographer to get closer to these wild animals

Below The Dolomites Seiser Alm Capture on a Hasselblad L1D-20c, a state-of-the-art aerial camera, Ales was able to capture a unique perspective

Discover what cameras, lenses and accessories are best-suited to shooting black and white photographs, plus the best ways to edit and print your work

24

Is it worth getting a specialist black and white camera? We’ve put a popular monochrome-only Leica through its paces to find out what the images reveal

28

Our first introductory guide will explain how to set up your camera, see in black and white, consider tonal range, and edit like a pro in Photoshop and Lightroom.

If you’re looking for the best equipment for a monochrome workflow, then this is the guide for you

This whole bookazine is dedicated to the intricate art of black and white photography, and one area that really has to be considered to get the best results is the kit that you choose to use. Over these pages, we will explore all the top kit – from your cameras and lenses, to software and printing, to finally presenting your work. There are several genre-specific features that you need to look for, and we will break these

down as we move through this gear guide. One decision that you will need to make when it comes to monochrome photography is whether you are going to shoot in black and white, or convert it after in post-production. There are advantages to both. If you shoot in black and white, then you can see how the tones and contrast are applied in the image, which means that you can correct the shot to match your own artistic vision. We have included

cameras that have monochrome modes, as well as lenses and filters that will improve your blackand-white shots for a variety of subjects. However, we also take a look at the best software options to do the conversion for you, the advantage being that you can keep the colour version and work on the mono version separately. Think carefully about your requirements and then read on to find out what your kit bag is crying out for…

From DSLR to compact system cameras, here are some great camera options

HIGH-RESOLUTION DSLR

If having a compact-sized camera isn’t important to you, opt for a high-end DSLR like the Nikon D850. It remains one of the best DSLRs that you can buy today, equally capable of shooting portraits, landscapes or fine art black and white. Its 45.7MP fullframe sensor offers potential for large and detailed images, the solid build can withstand the elements and the 3.2-inch tilt-angle touchscreen makes composition a breeze. You’ll have access to a myriad of Nikon lenses, and for now, Nikon is still releasing new firmware to improve the camera and keep it up to date with the latest features.

Picking a camera for monochrome work isn’t so different from choosing a camera for colour work, as it’s unlikely that your only use for a camera will be black and white. Ensure that your chosen model has features that will help you to capture the subjects you want to portray in mono, including black and white shooting options in the menu. A high resolution sensor is ideal, as sharp images are especially suited to monochrome conversion. Noise will generally be enhanced in monochrome,

Enthusiast mirrorless cameras are ideal if you know you’re going to shoot a range of styles. That’s because they offer you a wide range of lens options and a weatherproofed build, but are more lightweight than a DSLR and cheaper than a specialist monochrome camera. The full-frame Panasonic Lumix S5 camera features an L.MONOCHROME mode designed specifically to optimise black and white shooting, and it offers impressive dynamic range too.

Mirrorless cameras are compatible with a range of manufacturer and third-party lenses, so there’s flexibility

but the latest cameras now handle ISO very well. We’ve mainly focussed on interchangeable lens cameras – like a DSLR or mirrorless camera – here, as these are the best option for covering all manner of subjects and projects with different focal lengths. If you’re really serious about black and white photography, specialist cameras like the Leica M10 and Q2 Monochrom (see a full review on p24) exist just for this. Without a color filter array, they’re hard to beat when it comes to detail and tone.

Most digital cameras offer black and white shooting modes or film simulations, which are perfect for capturing more atmospheric shots

Rather than being a buying a larger DSLR, you could try a compact-system camera with interchangeable lenses, which means that you have the benefit of flexibility and compactness. The Fujifilm X-T30 II is a brilliant value mirrorless camera with a 26.1MP X-Trans CMOS IV APS-C sensor. Fujifilm’s Film Simulations are interesting , too, as they allow you to emulate classic black and white film stocks. Several modes can be used with red, green or yellow filters for further experimentation and control over your images.

If you have a lot of money to spend, there are high-end camera that can capture images at greater quality purely in monochrome. The Leica M10 Monochrom is a pricey but beautifully engineered option. With its custom-made monochrome 40MP full frame sensor, each photosite captures only luminance (brightness) information – no colour. The rangefinder system offers accurate focusing, and the maximum ISO 100,000 is impressive.

Live View mode enables you to check that a shot works in mono before capturing

Picking a lens for your camera to use for black and white photography is dependent on the subject that you’re shooting. If landscape is preferable, then it is worth looking into an ultra-wide angle zoom lens, so that you can play with your composition to bring focus to the details and heighten the perspective, both traits that are essential to monochrome photos. We have picked a couple of our favourites here, new and old,

and these have built-in stabilisation features and large apertures to help get that perfect tonal range that is so necessary for working in black and white. If it’s portraits that you’re working with, then look for a wide aperture lens, so the maximum amount of light is taken in during low-light and indoor shots. These lenses are also good for working in conjunction with lighting setups to produce high and low-key effects.

This lens is designed in such a way that it minimises lens fall-off and increases peripheral brightness

See what optics you need for what you want to shoot

When you’re shooting street photos, you’ll need a lens that will let you get in close to your subject while you stay back, so this 18-135mm f3.5-5.6 zoom lens is perfect. The longer focal length will help you get great candids but the wide angle also means you can capture landscapes too while travelling. It also has quiet STM focusing and Dynamic Image Stabilizer to reduce camera shake.

When shooting certain monochrome shots like long exposure landscapes, it’s important to use a tripod to eliminate unwanted motion blur. There are hundreds of tripods out there; Manfrotto and Peak Design are two good brands with a variety of options depending on your budget and needs. Tailor your tripod to your camera and lens setup – you won’t need the sturdiest model for a compact camera, for example.

Landscapes are one of the most popular subjects for monochrome photography, and an ultra-wide-angle lens like the Sigma 12-24mm f4.5-5.6 DG HSM II (pictured) will do a great job of capturing them. Landscape lenses need to be lightweight and quiet, and the Sigma even has a full-frame view with Super Multi-Layer Coating to reduce flare and ghosting.

This compact lens weighs just 670g, making it good for taking out and about

If it is monochrome studio portraits that you’re interested in, then you should look for a fast maximum aperture and a rounded diaphragm to help produce softly blurred depth-of-field effects. The Nikon 85mm f1.4G AF NIKKOR (pictured) is a great lens that will help you to achieve people shots in the studio. It’s a medium telephoto lens with a fast maximum aperture of f1.4 and internal focusing. It’s lightweight too at 595g, which isn’t necessary for portraits, but it always helps!

The wide-angle view will exaggerate perspective, giving landscape photographers room for creative compositions

If it’s a multipurpose lens that you require, then you will need a good all-rounder. The Sigma 24-70mm f2.8 EX DG HSM (pictured) is a large aperture, standard zoom lens, meaning that it is as comfortable taking portrait shots as it is landscapes. The f2.8 aperture throughout the zoom range ensures quality when indoors or in low light, and the lens coatings help to remove aberrations and distortion. It has HSM for quiet yet fast focusing and it can focus down to a distance of 38cm.

Filters are essential in black and white photography if you want to produce the very best results. By using them, you can make a big difference to the tonal range of your photos. With good black and white photos the viewer can almost visualise the scene in colour without any colour information present, simply by the tones presented. When a filter is used, it enhances certain colour tones in the final image, and can make a monochrome image really pop. By using a filter of a set colour, you will

Hoya offers a wide range of coloured filters, which can be used to enhance the tones in your monochrome images. Prices vary depending on the size and the colour chosen, so visit the website to find out more. Use the Red filter to boost contrast in images with red, brown and orange – perfect for autumnal shots. There are also corrective filters, warm filters and portrait filters to choose from.

Compatibility

Hoya offers a massive range of different colours of filter to suit all lens types

Contrast boost

The K2 Yellow filter, which is a popular choice for portraits, can help to boost contrast between sky and foreground

The colour of filter that you choose will have a dramatic impact on your final photo. Here we show you what four popular colour filters do to the same monochrome image.

Some of the best filters and brands available right now

Cokin’s P series of filters are square filters designed to fit with a filter holder. You need to chose the holder to for your lens, but you can then use the filter on any lens size as long as you have the holder for it. Cokin’s colour filters are modestly priced and come in a range of colours, so you can experiment with tones at minimal cost. The H40003 P Series Filter

Kit pictured here is designed for enhancing contrast between colours in black and white photography, and includes four filters.

lighten that particular colour in tone, and you will pop the tones of the complementary colours. Yellow filters are particularly popular, as they are good for making subtle changes, especially to the blue sky in landscape shots. Red is best for creative effects with loads of contrast. Blue and green are also available.

The Tiffen Black & White Three Filter Kit combines the essential yellow #6, green #13, and red #25 contrast filters together, along with a four-pocket filter pouch, to provide a convenient solution for producing varying degrees of contrast when working with black and white film. Available in a wide range of sizes, Tiffen filters are known for being highquality but well-priced. The Black & White starts at around £40 ($40), depending on the filter size that you buy.

If you are interested in experimenting with infrared digital photography, an R72 filter is what you need. It permits only light above the 720nm wavelength to pass through, effectively filtering out all light bar infrared light, which can’t be seen by the naked eye. This option from Urth is backed by a lifetime warranty, and as an eco-conscious company – Urth says your purchase will fund local communities to plant five trees in areas affected by deforestation.

Infrared

The 25A Red filter is great for those with an interest in infrared photography

Post-production is one area of the photographer’s workflow that just can’t be ignored. While many cameras will come with their own software solutions, if you want dramatic and striking black and white images then you need access to a good image editor. We have listed the four best software packages, but there are others out there that are worth considering.

Photoshop Elements, for example, has really upped its game over the last few versions, so if the full Photoshop package seems a little heavy

handed for the editing you require, then it’s a good option at a fraction of the cost. Photoshop, however, is now available in monthly payments through Creative Cloud, which helps to break the cost down. Lightroom is also a good alternative to Photoshop, as it’s tailored just to photographers, rather than digital artists, 3D artists, web designers and the many other creatives. And don’t forget that the majority of big-name packages will be extendable via plug-ins.

Catalog Lightroom’s easy-to-use interface makes it easy to find the image you want

Plug-ins Lightroom supports external plug-ins to extend its functionality even more

Silver Efex Pro is a powerful black and white converter in the Nik Collection.Silver Efex Pro remains the best digital black and white plug-in ever and is updated in the latest Nik Collection 4 version with a fresh, modern interface, a new ClearView option and more powerful selective control points. You can use the Nik Collection 4 plug-ins with Photoshop, Lightroom and from within DxO PhotoLab – or use them as external editors with other programs like Capture One.

Adobe’s subscription plans have made Photoshop more affordable. The Creative Cloud Photography Plan – which includes Lightroom, Lightroom Classic, Photoshop, and 20GB of cloud storage – starts at £9.99/$9.99 per month, giving you access to software updates and the latest features.

Photoshop is still the top image-editing software for a reason, but you may find it provides more than you need. If you’re working with colour images, the Black & White adjustment layer is a great way to tailor results without affecting the original permanently, and the many colour and tone tools mean that monochrome images can be made to pop.

With unique new features alongside an interface overhaul, Serif Affinity Photo 2 proves that budget software doesn’t have to mean compromise – or a monthly subscription. There are a range of tools for black and white image processing. Where things get really interesting is when you take advantage of the colour mix sliders, which you’ll find under Black and White in the Tones panel. The Black and White Adjustment is the best tool for mono conversions in the Photo Persona, while Nondestructive adjustments can be made with a Black and White Adjustment Layer – in much the same way as Adobe Photoshop CC (but for a one-off price).

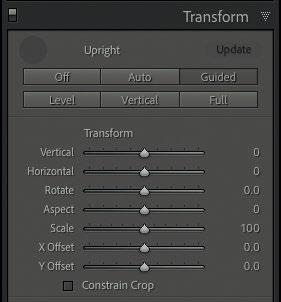

Lightroom has really worked hard to win popularity among professional photographers, offering more and more editing options in each version so that having Photoshop is less essential. Whether you use Lightroom Classic or the streamline CC version, its sophisticated colour and tone tools mean that when working with monochrome or colour images, it’s a relatively simple process to enhance contrast in a nondestructive manner.

The editing options are becoming more and more advanced while still retaining ease of use

Newest version

Lightroom Classic offers advanced black and white conversions, letting you adjust a mix of colour bands

DxO PhotoLab 6 is arguably the best photo editing software for RAW image processing. Its lab-developed lens corrections are excellent, correcting edge softness too, and its improved DeepPRIME XD processing gives spectacular results with high ISO images. Thanks to the ‘nested’ Projects feature, DxO Photo Lab is also now a much better photo organizer. All your adjustments can be changed, removed or added to in the future, and you can create ‘virtual copies’ to try out different adjustments.

Once you have a perfectly shot and edited black and white picture, it’s time to turn your attention to output options. A printer is the first vital step in the workflow chain, and there are two key types of printer that you are likely to come across. First, there are the consumer printers, which we will look at here, and then there are professional printers, if you want to get more serious. When looking at consumer printers, don’t just go straight

This A2 format photo printer brings pro-grade capabilities with a better price tag to appeal to enthusiasts. It’s big, and over £1,000, but a serious choice for home printing. With 11 colour pigmented inks overall, the grey and photo grey inks in combination with either the photo black or matte black ensure neutral prints with deep blacks and good tonal spread from highlight to shadow areas. The Grayscale print panel also allows adjustments to be made.

Home printing no longer has to mean low quality

For an affordable price, the Envy 6230 is a high-quality inkjet model that can also make photocopies and scans. The compact shape is designed to fit on your desk or on a shelf, so it won’t take up too much room. You can also print directly from your smartphone and tablet using an app and it will make speedy work of it, printing up to 13 pages per minute for black and white. You can print borderless photos and the built-in photo tray lets you print 4x6-inch photos without changing paper. It’s a great entry-level model for home printing.

If you are interested in scanning in old monochrome film photos, then it is worth investing in a dedicated scanner rather than using the all-in-one functions of many of these printers. Photo scanners come with a negative or slide tray, which holds the film in place while it’s scanning, ensuring the highest quality. All-inone printers with scanners are usually best for document scanning.

in for the most expensive you can afford, but don’t snap up super-low bargains either – both can be misleading. Think carefully about what you need from your printer. If you need innovation and quality, then buy the best that you can afford within your budget; however, if bells and whistles don’t tickle your fancy, you may be paying for things that you don’t really need. We present some great options for you here.

Easy transfers

Wi-Fi enabled cameras can share shots straight to it and the Canon Print app shares from phones

If you’re after a more compact printer, Canon’s Selphy series may be for you. The revamped CP1500 portable photo printer is sleek, fast and well connected, and a battery pack is available as an optional extra so you can use it outdoors too. The on-screen instructions make it easy to use, and it can produce standard 1015cm, square and credit card size prints. It runs on dye-sublimation technology, so there’s no ink to consider. Instead, each specialist sheet of paper is fed through the printer, followed by a final protective, smudge and fingerprintresistant coating to ensure longevity.

Print in common sizes

Print stunning quality photos in borderless sizes up to A2

Billed as a ‘small-in-one’ printer, the XP-970 aims to keep size and weight to a minimum. It still manages to pack in some useful extras like a high-res 4800dpi scanner, an SD/HC/XC card slot and a PictBridge port, all brought together by a 4.3-inch touchscreen with an intuitive interface. Although the maximum print size is A3, the scanner is limited to A4. Going large to A3 format printing makes your photos look much more imposing, and print quality itself is very good. It’s not a specialist black and white printer, but a versatile and well-priced model that will suit most of your general printing and office needs at the same time.

The LCD screen panel makes it easy to select and navigate through all of the available printing options

It’s all well and good producing amazing black and white images, but if you never display them, the prints will end up going dusty in an old shoebox. Make your photographs into the works of art that they are by investing in a decent frame. Custom frames give the best results as the size, finish and mounting method are all interchangeable so that you can get exactly what you want. This is

especially useful if you want to print at a nonstandard size to fit a particular wall or to show the work off to its best potential. Also, for holding personal exhibitions or selling work, then custom frames give that air of quality and uniqueness. Here we round up four popular online services that enable you to create the frame that you want with no restrictions.

EFRAME

eFrame is a great custom frame site as it’s really easy to navigate. It has loads of guides on how to measure a print properly, how to use the website and inspirational galleries to get an idea of how a frame will look. Everything is customisable with both wood and metal frames, standard and custom size options and an online preview. www.eframe.co.uk

This simple site stocks a range of made-tomeasure frames, mounts and multi-frame options. As well as offering a variety of colours and materials including wood and metal, there are also box frames and wooden frames too. The site is easy to navigate around, and you can generate a quick quote by entering the photo dimensions. There’s also a useful help section that talks you through measuring, deciding what mount you want and how to order.

www.pictureframesexpress.co.uk

There are also digital photo frames out there if your framing needs are limited to displaying your work around the home. Look for ones with good connection options, in particular Wi-Fi or card slots, so it’s easy to update your frame with your latest shots. Also make sure that the resolution is as high as possible to make the most of your mono shots. You can also display slideshows of your shots on a tablet.

Ready

There’s

EasyFrame offers both standard size and custom size frames, with the latter made simple thanks to a box on the home page into which you can enter your measurements and get straight into customising. The frames are handmade in the United Kingdom and are dispatched within 1-3 days. There are plenty of categories to choose from, including metal, wood, box frames and more, and just as many mounts. The Help and Advice section covers all you need to know. www.easyframe.co.uk Sample

WhiteWall is a premium service for both printing and framing your photographs. They offer a wide variety of framing options, alongside other products such as acrylic and canvas prints. You have a lot of options to chose from, including the type of glass used, paper type, sizing (you can create a custom size) and more. WhiteWall ship internationally and offer a five-year guarantee They’re not the cheapest or fastest out there but you pay for a product that’s very high quality. www.whitewall.com

Custom frames

You can create your own bespoke frame and mount using the Custom option

Price: £5000 / $5,995

The Leica Q2 Monochrom is a very unusual camera because it combines Leica’s Q2 full-frame compact camera with technology from its Monochrom series of black-and-white-only cameras. As a result, the Q2 Monochrom has a 47MP CMOS sensor with no colour filter array, so it is only capable of capturing black and white images.

Leica has paired the Q2 Monochrom’s sensor with its Maestro processing engine, enabling a sensitivity range of ISO 100100,000, as well as a maximum continuous shooting rate of 10fps. Although the Q2 Monochrom can only record black and white images, they can be recorded as JPEGs and/ or RAW files, and there are three colour tints (sepia, blue and selenium) that can be applied to JPEGs in two strengths. The strong setting is subtle, but we still favoured the low setting.

As it’s a compact camera, the Q2 Monochrom has a fixed lens – the same Leica Summilux 28mm f/1.7 ASPH as on the Q2. This is nicely balanced on the camera and has a good ‘walkabout’ focal length. However, the camera can crop in to a framing equivalent of 35mmm, 50mm or 75mm, reducing the image size to 30MP, 14.7MP and 6.6MP respectively. Helpfully, if you record RAW and JPEG images simultaneously, the JPEGs are permanently cropped but the RAW files retain the information from the whole sensor and can be ‘uncropped’ in RAW editing software. Although it doesn’t have the windows required by a rangefinder, the Q2 Monochrom could slip among Leica’s digital M-series cameras and not stand out. It echoes their rectangular shape, curved edges and highclass looks. And it’s not just looks – its

In addition to the manual focus and aperture rings, the Q2 Monochrom has a third ring that enables the closest focus to be reduced from 30cm to 17cm.

Exposure is set using the shutter speed dial and the aperture ring, so the camera can be used in Program, Aperture Priority, Shutter Priority or Manual mode.

The manual focus ring has to be unlocked by pressing a small adjacent button before it can be rotated. Distance and depth-of-field scales enable hyperfocal distance and zone focusing.

The contrast detection AF system has 225 AF points, which can be selected using the navigation pad or with a quick tap on the screen. Face detection is also available in the Q2 Monochrom.

The lens has a focal length of 28mm, but there are crop settings equivalent to 35mm, 50mm and 75mm, reducing image size to 30MP, 14.7MP and 6.6MP.

It can shoot C4K (4,096 x 2,160) video at 24fps or 4K (3,840 x 2,160) at 30fps, and Full HD video at up to 120fps, but there’s no external mic port.

build is very good too, made from metal with a delightful standard of finish. It’s also weatherproof to IP52.

Rather than an optical viewfinder, the Q2 Monochrom has a 3.68 million-pixel OLED electronic viewfinder – the same as the Q2. This gives a clear view with plenty of detail, which is handy when having to focus manually. The view can also magnify automatically when the manual focus ring is rotated, and focus peaking can be activated if you want it.

There’s also a three-inch, 1.04 million-dot touchscreen on the back of the camera. Like the viewfinder, this shows a good level of detail, but as it’s fixed on the back of the camera, it’s not as helpful for low or high-level compositions. Nevertheless, it’s responsive to touch, and it helps to make the Q2 Monochrom very intuitive to use. A press of the menu button, for example, brings up a status screen showing the focus, metering, drive, and self-timer modes, and any can be selected and adjusted via the screen. Pressing the menu button again brings up a

Right

Understated style Leica has kept the Q2 Monochrom clean and uncluttered – there’s not even a red badge

Left

Flat front

The flat front has a textured coating, but there are optional grips available to provide more purchase

Below

Solid build

The top plate is machined from aluminium, while the body is made of magnesium alloy

The enhanced resolution of the sensor ensures that images have plenty of detail across the frame, with RAW files in particular impressing

customisable list of ‘Favourite’ features, and further presses move through the main menu.

Like a Leica M-series camera, the Q2 Monochrom has traditional exposure controls, so the shutter speed is set via a dial on its top plate, and there’s an aperture ring on the lens. These have markings of ‘A’ for automatic, and when they are both set to ‘A’, the camera is in Program mode. Taking one off Auto puts the camera in Shutter Priority or Aperture Priority, while setting a specific aperture and shutter speed puts the camera in Manual mode.

Despite the M-like looks, the Q2 Monochrom can focus automatically. This focusing system uses contrast detection and has 225 points that can be selected automatically by the camera, or by the photographer with a tap on the screen or via the navigation controls. While phase detection is generally favoured, the Q2 Monochrom’s focusing is good. Also, helped by the lens’s maximum aperture of f/1.7, it copes well with low light. It also does a decent job of tracking a moving subject, and the face detection is effective, though the design of the camera and the lens’s focal length don’t make it a natural choice for action or wildlife shots. However, it’s well-suited to street photography.

Thanks to its 47MP sensor, with every pixel being used to gather data without interpolation, the Q2 Monochrom is able to produce images with lots of sharp detail. The micro contrast in JPEGs looks a bit high, so as usual it’s best to shoot RAW files.

The lack of colour means there’s no chroma noise, only luminance noise, which is controlled well up to around ISO 25,000

The Q2 Monochrom’s Summilux 28mm f/1.7 ASPH lens is an excellent performer, controlling distortion, vignetting and flare extremely well

Unlike most cameras, which have a colour filter array over the sensor to enable them to reproduce colour, the Q2 Monochrom has no coloured filters over its CMOS chip. This means that each pixel receives more light, which is good news for noise control. It also means that each photo site is used to gather brightness information, and unlike with a sensor that has an RGGB filter pattern, there’s no interpolation required. Consequently, a monochrome sensor can capture more detail.

The downside is that there’s no option to use the colour information for brightness and contrast adjustment, but the Q2 Monochrom’s sensor responds to coloured lens filters in the same way as black and white film, so they can be used at the shooting stage.

As the Q2 Monochrom doesn’t capture colour, there’s no colour noise, and the luminance noise is very well-controlled. Going higher than ISO 25,000, though, can result in finer details being lost and some muddy or slightly smudged shadows.

Working on a RAW file in Adobe Camera Raw reveals that the Q2 Monochrom captures a wide dynamic range, and it’s impressive how much detail can be pulled back from the highlights or revealed in the shadows.

As the Q2 Monochrom doesn’t capture colour, there’s no colour noise, and the luminance noise is very well-controlled

Timeless, gritty, truthful and classic are all common ways of describing black and white photography. Despite the advent of mass-produced colour film, which made everyone think black and white would fall out of fashion, even after nearly 200 years since Joseph Nicéphore Niépce made the first black and white photograph, mono remains as popular as ever. Perhaps even more so, given the resurgence of film photography in recent years.

Of course, one of the great advantages of digital photography is that you can capture colour and black and white images on a whim, switching between colour and black and white is as easy as diving into a menu. It’s definitely much easier than having to change a roll of film – although both mediums are rewarding.

Here, we’ll reveal some hints and tips for shooting better black and white shots, helping you to create majestic moments in monochrome.

You’ll be able to shoot better black and white images if you have an eye for what works best in the medium. Examine the portfolio of any renowned black and white photographer, past or present, and you’ll soon spot recurring elements in their photographic approach. With the distraction of colour removed, shape, form, pattern and texture take on added significance in black and white photography, and can all be used to add impact (we’ll look at the role played by tone on page 32.)

Shape describes the appearance of a subject in two dimensions. Identifying the shape of subjects, and knowing how best to arrange them in your images, will really help to improve your photography. Try arranging shapes to emphasise their most interesting aspects, or create an intriguing composition of different ones.

Things to look out for:

1 Leading edges

2 Contrasting tones

This describes the three-dimensional appearance of a subject, and how its various parts are arranged. How the subject is lit, and where light and shade intersect, provide depth cues. Here, the petals of the rose lead the eye into the centre of the image.

Things to look out for:

1 Sense of depth

2 Tonal variation

The distribution and repetition of shapes into patterns – whether in natural or built environments – help us make sense of everyday life. In this example of man-made patterns, taken in a Manchester street, two contrasting buildings butt up together in an interesting juxtaposition. It’s a striking enough image in colour, but strip away the red brick and the sand-coloured ornamentation around the windows of the Victorian building, to bring it tonally closer to the Brutalist 1960s office block, and the clash of architectural styles looks even more pronounced than it did in colour.

Things to look out for:

1 Uniformity of shapes

2 Sequencing of shapes

3 Different types of shape

Whether smooth or uneven, this quality describes the tactile sense of an object and invites us to reach out and touch it. In colour, this ancient Roman column features all the ageing and weathering one would expect to see, but the black and white version feels better suited to the subject.

Things to look out for:

1 Smoothness or roughness of the surface

2 Variation of texture

3 Tonal distribution

An average scene in average lighting conditions (above right) will contain a range of different tones, from shadows and midtones to bright highlights. A scene like this will have a brightness value of 18% grey – which is also the value that your camera’s light meter

is calibrated to, so that consistent exposures with balanced tones can be achieved. Due to lighting conditions, some scenes will feature different tonal variations, so tone becomes something that can be considered for creative effect in the final image.

Think about tonal value while considering shape, form, pattern and texture, and combine them all to determine your creative vision for a black and white image. Below we outline the common tonal variations found in black and white; use these looks for inspiration.

An image made up mainly of light bright tones and white is known as ‘high-key’. It’s a popular technique in studio photography.

With no midtones between the brightest highlight and the deepest shadow, this image has a look that’s ideal for presenting extremes.

Midtones dominate this misty landscape scene. The lack of contrast and extreme dark tones lends a sense of tranquillity.

Conversely, an image composed of predominantly heavy dark tones and black is known as ‘low-key’. In portraits, it creates a sense of mystery.

While it’s perfectly possible to shoot just in black and white on a digital camera, we recommend taking a different path: capture in colour and convert later. This will give you greater flexibility: if the final black and white image doesn’t work out quite how you saw it, you’ve still got a colour version. You can’t put the colour information back into a black and white image, but you’ll always get black and white from colour. Shoot in raw for maximum detail (below).

Shoot in raw and JPEG simultaneously to capture the maximum amount of image detail for post-processing. The formats below are all supported by Adobe in its editing applications:

.CR2 Canon .RAF Fujifilm .NEF Nikon .ORF Olympus .RW2 Panasonic .PEF Pentax (or .DNG) .ARW Sony

1 ISO Choose a value to give you as much image quality as possible; this will be handy during processing or conversion of images.

2 Exposure mode Choose according to the shooting situation – but if you’ve got time to think about what you’re doing, use Manual.

3 White Balance

For the widest range, select a WB preset rather than Auto WB. If one colour dominates the scene, try another preset.

4 Live View

Confirm that a scene will work in black and white by selecting the Mono Picture Style, then view the image on the rear screen.

Modify your images incamera by using filters you already own. The circular screw-in type is arguably the easiest to use, as it’s less of an encumbrance than a filter adapter, although the latter format makes changing individual filters on the fly a bit easier.

If you want to use the in-camera black and white mode (for a Live View preview, for example), head for your camera’s creative image modes. Select Monochrome and all images will be captured in black and white.

POLARISING FILTER

A polariser will make blue skies more vivid, and heighten the dramatic impact of many landscape shots.

RED FILTER

Attach one of these to make blue skies appear darker, and to make foliage look crisper and brighter.

GREEN FILTER

Grass, foliage and vegetation will be depicted more vividly than normal. Skin tones and lips will appear muted.

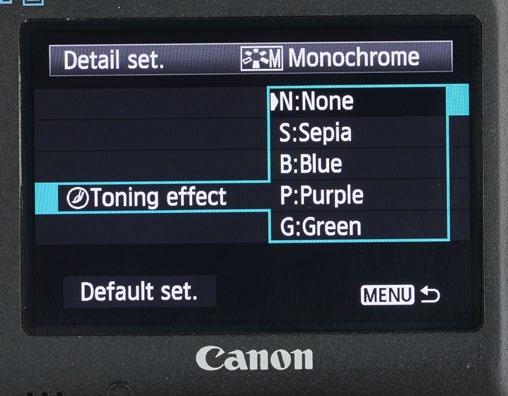

In addition to controls for sharpness and contrast, the Monochrome Picture Styles mode gives you the option of adding four filter effects in-camera (or later, in editing software). Many cameras also offer a toning effect.

1 Go to Picture Styles Access the Picture Styles menu, or use the Creative Mode button (if fitted to your camera) as a shortcut.

2 SELECT MONO Scroll through and select Monochrome. A warning in the viewfinder confirms you’re shooting in mono.

3 PREVIEW THE SHOT One boon of using this setting is that you can use Live View to see how your image will work in black and white.

1 FILTER SELECTION Call up the Monochrome Picture Styles menu and select Yellow, Orange, Red or Green in ‘Filter Effect’.

2 CHOOSE YOUR FILTER

You can also adjust the Sharpness and Contrast. To boost the filter’s effect, dial in some extra Contrast.

3 TRY THE TONING EFFECT Try creating a mono image in a particular tone. The Canon EOS 5D III has Sepia, Blue, Purple or Green.

As we’ve seen, shooting in colour and converting to black and white afterwards gives you more flexibility than working solely in mono. And you’ll come to appreciate the extra information in raw files during editing. We’ve put together two tutorials to cover the two most popular image-editing packages

– there’s more than one way to go about mono conversions, but these techniques are easy to learn and master.

If you want to take things further, then try Silver Efex Pro, part of DxO’s Nik Collection (which we mention on p21). This works as a plugin within Photoshop and Lightroom, and

recreates black and white film and darkroom effects. Nik Collection 5 is the latest release, and contains eight plug-ins that will unlock your full photographic potential when editing. Find out more at www.nikcollection.dxo. com and claim a free trial for 30 days – you don’t need to provide a payment method.

Great results in the quickest time

Achieve punchy black and white effects

There are several ways to convert colour images to black and white in Photoshop, but one that produces fantastic results in the quickest time is by using a Gradient Map Adjustment Layer. It may not offer the most control out of all the options, but you certainly won’t be disappointed.

1 Apply a Gradient Map Click on the Create New Fill Or Adjustment Layer icon, which is a half-black half-white circle at the bottom of the Layers panel, and select Gradient Map. Double-click the gradient when the dialog box opens. When the Gradient Editor opens, select ‘Black, White’ and click OK.

2 Use Levels to boost contrast If you’d like to increase the contrast of the image further, create a Levels Adjustment Layer; when the dialog box opens, set the white point to 10, the black point to 245 and the midtones/brightness to 1.15 to lighten the image after the contrast boost, then click OK.

3 Use Levels to reduce contrast The Gradient Map conversion technique naturally produces a high-contrast result; if you’d like to reduce it slightly, you can use Levels again. Reset all the changes you made in the Levels Adjustment Layer in the previous step. Now drag the black Output Level to 25 to lighten blacks.

Take full control of mono conversions

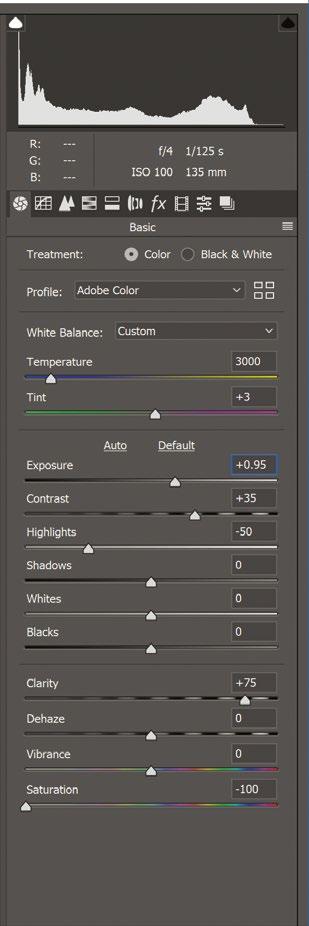

If you shoot in raw you can get the best results possible by converting to black and white in Lightroom or Adobe Camera Raw (which use essentially the same tools). Working on the raw image data provides more room for manoeuvre, and there are eight colour channels to control exactly how the colours will be converted to greyscale.

Lightroom offers a sophisticated way to adjust tones based their original hues

4

Make basic adjustments Before converting an image to black and white in Lightroom, it’s best to correct white balance and process the image so it looks how you’d like in colour. Doing this is important, because it gives you a better starting point to work from once you convert to mono...

5 Convert to mono At the top of the Basic panel on the right, click on Black & White to convert to mono, then scroll down to Black & White Mix. Dragging to the left darkens a channel, while to the right lightens. For this image, Yellow and Orange were set to +18 to lighten foliage, and Blue to -47 to darken the sky.

6

Increase contrast Monochrome images can handle much more contrast than their colour counterparts, so at this stage you can increase the contrast slightly to help make the textures and shapes in the image stand out. Simply set the Tone Curve preset to Strong Contrast.

Adding a split tone is a great way to add subtle colours to the shadow and highlight areas of black and white images. It’s a classic darkroom technique that can be applied using the Split Tone panel in Lightroom, or by using a Gradient Map Adjustment Layer in Photoshop with the desired colours set.

Improve your black and white shots with these treatments

1 CYANOTYPE Add a Gradient Map Adjustment Layer and choose a colour from the Photographic Toning options. Adjust Opacity as required; to add contrast, use an S-curve on a Curves Adjustment Layer.

An essential tool in darkroom printing, dodging and burning involves selectively brightening (dodging) and darkening (burning) different areas of the image, to draw the viewer’s eye to certain points. We’ve performed this process in colour, before conversion into black and white.

Open your image in Photoshop and select the Dodge tool (displayed as a racquet icon) from the Tools palette. Dodging works by painting a brush over desired areas, so first select the size of the brush you need. (It’s at the top left of the screen, just underneath the menu.) Next, select Shadows, Midtones or Highlights and the Exposure required, expressed as a

percentage. Then just paint the brush where the dodge effect is required on the image. To stop the image clipping, tick Protect Tones. In the image above, we’ve lifted the rocks in the foreground [1] out of shadow and have made the castle and mound [2] lighter.

Burning is the opposite effect to Dodging, and the parameters you can select are the same. (The icon mimics using a hand in a real darkroom.) As before, select the part of the image you need to modify and paint in the corrections required. We’ve burned in some contrast to the sky [3] and have made the clouds darker above the horizon to the right of the image [4].

2 LITHO printing Use layers and Adjustment Layers to get this effect. It’s all about the contrast between strong shadows and soft highlights. Add some noise to the shadows, and tone to the midtones and highlights.

3

High key Why not take a predominantly light-toned image even further and push it to extremes? Add a Curves Adjustment Layer and raise the curve to lighten all the tones, without losing the highlight detail.

The sensors in modern digital cameras and smartphones are sensitive not only to visible light, but also to invisible ultraviolet (UV) and infrared (IR). Allowing UV and IR to enter the camera for normal photography would lead to strange colours, so the manufacturers filter out the UV and IR at the time of manufacture by placing a UV- and IR-absorbing filter over the sensor, so that it is effectively only sensitive to visible light. It is possible to have this filter removed (or remove it yourself) and either replace it with an infrared transmitting filter inside the camera, or place an IR filter over the lens, giving a camera that will record IR images. This is expensive to carry out, however – and, in the case of an internal filter, renders the camera useless for normal photography.

You can also use a conventional unconverted camera for IR by placing an IR filter over the lens. This removes all the visible (and UV) light to only allow IR through. Because the camera still has the filter over the sensor to filter out the IR, exposure times will be long – in the region of 5-10 seconds or more at f/5.6. The results may not be as good as a converted IR camera, but certainly be strong enough to produce some interesting images!

You will need a 720nm IR filter (720 indicating that the filter is transmitting IR wavelengths of 720 nanometres). Various IR filters are available such as the Hoya R72, or Cokin Infrared 720 (89B) A007 Square Filter, and various other types can be found on eBay. IR filters screw in to the front of the lens and cost from roughly £35 for smaller filter sizes, increasing in cost for bigger diameters. You only need the 720nm version unless you get a camera converted. Beware of using a thick IR filter on a wide-angle lens – you may get vignetting. IR filters are virtually opaque, so when you put one on the lens you will not be able to use the viewfinder to frame up. The Live View facility on many cameras may work – albeit with a rather dim image – so it is best to compose and focus, then place the filter on the lens before shooting. Whether you’re using a filter or a converted camera, it’s best to shoot on a bright day. If you do, the blue skies will be captured as sumptuous dark tones, while the photosynthesizing foliage will be recorded in white, almost snow-like hues.

The scene was shot with a 720nm IR filter over the lens, and is shown here straight out of the camera. The exposure is 5 sec at f/5.6, ISO 400. Note the strong vignetting in the shot, created through the use of a thick IR filter on a wide-angle lens.

2Desaturate the image in Camera Raw Reducing the saturation of the colours in Camera Raw gives a pleasing result. One technique that IR landscape photographers often use is ‘channel swapping’, where the red and blue channels are swapped in Photoshop’s Channel Mixer facility, to retain a bluish sky, but with false colour vegetation.

Adrian Davies reveals the gear and techniques you need to achieve a more otherworldly kind of image

Edit in PhotoMatix Three images were shot at 2-stop intervals: one underexposed, one exposed normally and one overexposed. All three were then imported in the HDR program PhotoMatix, where a host of different options is available. This final shot was processed with the Creative option.

3

While all lenses transmit infrared light, some produce images with distinct ‘hot spots’ in the centre, as shown in the close-up inset above. There is no hard and fast rule that dictates which lens models do this, and you will need to test your lenses to see if any are affected. There are databases online showing how lenses perform: try www.lifepixel.com/lens-considerations/lens-hot-spottesting-database

42 SHOOT MONO WITH MAXIMUM IMPACT

Get bold with your black and white imagery: learn how to shoot and shape the medium like a pro

54 GET DRAMATIC BLACK AND WHITE

Seeing and visualising scenes without colour isn’t as easy as it seems – but we’re here to help

66 CAPTURE ARTISTIC BLACK AND WHITE

Discover some rather different approaches for composition, framing and exposure in B&W

78

TAKE BETER LANDSCAPES

We focus on the forms, shapes, textures and depth throughout a scene, plus top editing tips

90 GET MORE FROM LIGHT AND SHADE

Embrace shadows, use graphic power and push the tonal range to intrigue viewers of your shots

102 MINDFUL PHOTOGRAPHY

Learn to take a more calm and still approach to photography with expert guide Paul Saunders

Capturing the world in monochrome has been an obsession since photography was invented – and in the digital era we still love its powerful visual appeal. Find out how you can shoot and shape mono for maximum impact

By Jon Adams and Andrew JamesWe live in a colourful world but sometimes an explosion of hues within a photograph can be distracting. Strip it out and you’re left with a simpler, more direct visual narrative.

Shooting in black and white helps you harness light in a fresh, and frequently more appealing, way. You learn to see the shapes, patterns, textures and tones that make up your composition.

Any subject can work well in black and white, but over the next few pages we’ll look at how landscapes, portraits, wildlife, the urban environment, and still-life subjects, can all be transformed when you choose to embrace a bold approach for shooting in monochrome.

It’s also true that black and white photography owes a lot of its enduring

success to understanding how to bring out its beauty after the shot has been taken. In the past we’d hide in darkrooms, sloshing prints around in chemicals or dodging and burning by hand, but digital photography allows us to work openly and easily with raw files to really hone our craft.

There really has never been a better time to experiment with the timeless and artful power that lies behind creating brilliant black and white photos.

Great black and white shots are all about shapes and contrast: the right balance of both allows even simple scenes to become dramatic mono compositions.

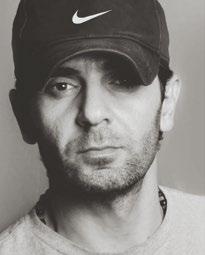

With portrait photography you are normally trying to flatter your subject with your images, but there are times when getting gritty is the way to go. It’s really easy to achieve with black and white and a willing ‘character’ as your subject.

As a rule, this style of shooting is best suited to a more mature, male face, so have a think about who among your friends and family might fit the bill. It’s best to be honest that you are going for a photo with edge, rather than one that makes them look 10 years younger!

A focal length around the 70 to 100mm mark is perfect for a headand-shoulders composition – and if your lens allows you to shoot at f/2.8, the limited depth of field will look amazing. Remember that the eyes must be sharp, so that’s always where you focus. Using natural light, a silver reflector and a dark background, you’ll get a result that looks great even before you start to boost its grittiness in editing.

To control the light in a portrait, you can move your subject into better lighting, add light with flash or LED lights, or bounce natural illumination back with a reflector. While a white reflector is OK to use, a silver one will be perfect for this style of black and white: it reflects more light and gives you the added bite you want. For this character shot, we positioned the model in a doorway with a dark wall behind, and asked him to hold the reflector so it bounced daylight up at, and across, the face. This simple approach provides bright catchlights in the eyes and strong, stylised lighting for a mean and moody look that suits the subject. Although the model is holding the reflector himself, it’s only his head and shoulders that are in the frame, courtesy of the narrow field of view provided by an 85mm lens. Shooting at f/2.8 gives us great clarity within the plane of focus, but pleasing diffusion back towards the model’s ears.

Use the Clarity and Texture sliders in Lightroom or Camera Raw to add impact to your mono images

While most of the work in your black and white character portrait is being done by the lighting style you’re using, you are still going to need a few image-editing techniques to add more impact.

Whether you use Lightroom or Camera Raw for your processing, you’ll find all the tools you need in the Basic Panel. The most important two sliders are found under the heading of Presence, and it’s the Texture and Clarity sliders that we’re going to concentrate on.

Normally you need to be careful with both these controls, as pushing them too far can make an image look over-processed – but as we are creating a hyper-real mono portrait, you can be quite gung-ho. As you increase both sliders, you’ll immediately see the effect, with a strong contrast and detail boost adding bite.

With a gritty mono portrait, there are times when including some surroundings will give the shot context. For these images of a Cuban tobacco farmer, a wide-angle lens was used. A wide-angle isn’t traditionally a good lens for portraits because it distorts features, but it can work well for an environmental shot of a gritty subject. Get close to your subject, remembering to focus on the closer eye, and watch how the background elements add to the composition. Don’t be afraid to shoot in both horizontal and vertical formats.

1

The basics In Lightroom’s Develop Module, click on Black & White or press V to go mono. Take the Whites slider right and Blacks left, just to make sure you are using all the tonal range. Pulling Highlights back helps keep all the detail you need.

2 Add definition It’s time to really make the shot gritty with the sliders under the Presence heading. Push both Texture and Clarity as far as you want, and the Dehaze slider can be pushed to the right for extra contrast, too.

If the idea of a landscape shot is to show the world just as we see it, then black and white may seem an odd choice! Of course, the monochrome roots of photography denied us colour as a choice for a long time, but it’s more than technical limitations that makes the black and white landscape fit into a category of its own. Many of the most famous landscape shots ever captured are in black and white, and pioneers like Ansel Adams are fondly remembered for their contribution to the genre – even though he actually shot nearly as much in colour as he did in mono!

When you break down a photograph into what it actually consists of, it’s an arrangement of shapes in a frame. These shapes are formed by nothing more than light and dark areas in different places, so everything you see is a pattern made up of different levels of contrast. Add colour to the mix, and the interplay between light and dark gets a little lost and confused. But the purity of black and white cuts through to reveal lines and forms, with none of the distractions that colour might bring.

When you line up a potential black and white landscape, you’re looking to arrange the shapes that form your scene in a balanced way, and need to concentrate on the contrast that’s present, rather than any balance offered by colour differences. A simple but effective way to assess the contrast is to close one eye and squint your viewing eye so the scene is simplified into what’s light and what’s dark.

Layers of depth are also important for mono scenics, so bring foreground detail close to the lens to draw in the eye, and make sure it leads through to a good backdrop. If the foreground and background share similar mono tones, you’ll need to separate them, with some midground, otherwise they will blend into each other.

The process of making a mono conversion in Camera Raw or Lightroom is straightforward. The aim is to get detail from foreground to background. This example is tricky, as the dynamic range in the scene is huge, but in black and white we can pull back the detail in both the shadows and highlights from a single exposure.

1 Go mono and balance up Under Profile, choose Adobe Monochrome. In the Basic Panel, push the Shadows slider right and pull the Highlights slider left to start balancing the contrast and revealing more detail. If you find you have to push Shadows to +100, then move the Blacks slider to the left to avoid washing out the contrast. This process will start to even up the darker and brighter tones.

With the overall range of the shot more balanced, now select the Graduated Filter Tool and drag a grad over the sky to cover the brighter areas of the image. Reduce Exposure, boost Shadows and pull Highlights within the grad to further adjust the effect. Now add another grad to the dark foreground, increasing Exposure and tweaking the other sliders to reveal detail.

Jon Adams takes you through the mono process step-by-step www.digitalcamera world.com/dc248

If you have difficulty visualising how the scene in front of you will look in black and white, you can set up your camera to deliver monochrome results. This can be really helpful, as you can still capture all the data in a full-colour raw file, ready for editing, but see the shot in mono on your camera’s screen. Just make sure you shoot in raw format rather than JPEG, so you can still access all the colour channel data to make a precise mono conversion in your raw conversion software.

On a Nikon model, in the Photo Shooting menu, select Set Picture Control and choose Monochrome from the list. On a Canon camera, select the Picture Styles menu, and choose Monochrome (M) from the options. Other makes have similar options.

Combine interesting details with bold contrasts to create dramatic and inspiring images from the natural world

Wildlife photography is highly effective when it appears in black and white and with a careful combination of shooting and editing, you can create beautiful wildlife images with a fine-art feel. The natural textures and tonal variety within the fur, feathers and scales of the animal kingdom lend themselves well to monochrome. Take away the distraction of colour and the patterns of an animal and its environment become more obvious. Black and white gives a fresh and artful twist to your wildlife. It adds an emotional directness that isn’t always as apparent in colour. While you can take any wildlife shot and convert it to monochrome, it really pays to think about which of your subjects, and the environments they are found in, will work well with colour stripped out. While shooting, look for tonal separation between the subject and its surroundings, and make sure that you capture as much of that interesting textural detail as possible. Be careful not to overexpose your image, especially in light areas of fur or feather. If necessary, use negative exposure compensation to retain that important textural detail.

You need a backdrop that looks natural and creates a tonal contrast or complement with your subject. That’s not always easy to achieve in the natural world – and if you are shooting at a zoo or wildlife park, it’s even harder! Avoid anything that looks man-made; if you can’t, look for a background that’s tonally even, so it’s much less distracting.

Both images below were taken at a zoo. On the left the man-made wall gives the game away, but the right image looks natural enough to have been shot in the wild.

Paint your contrast where you want it with non-destructive layering techniques in Photoshop

1

Edit your raw file Choose a wildlife image you think is going to work well: something with excellent texture and good tonal contrast throughout. In your raw conversion software, turn the image black and white and do your basic editing. The most important thing at this stage is to ensure that no highlight details are overexposed, so if there is a gap on the far right of your histogram, that’s OK.

2 Darken the image Take your image into Photoshop. Open Photoshop’s Layers Panel via Window > Layers, then click Create New Fill Or Adjustment Layer at the bottom and pick Curves from the list. Pull the curve down from the middle so that the whole image darkens. At this stage, we’re interested in creating the darkest point of the image, which is the area above the hare.

3 Paint with contrast Select the Brush Tool and choose a very soft-edge brush. Start with Opacity set to 100% and paint over the area you want to be the brightest part of the image – in our case this is the hare’s face. Now work around the rest of the image, changing the opacity of the brush to suit and paint back in the Background layer to create the overall balance of tonal contrast that you like.

The strong contrast between this mountain hare in its winter coat and the darker heather makes a great black and white image that we’ve been able to perfect in Photoshop.

Architectural photography

is often seen as a highly specialised discipline, but it’s one of the most accessible forms of photography, and is readily available – indoors and out, day and night.

Lens choices tend to involve shorter, wide-angle focal lengths because of restricted space and large subjects, but architectural details can be just as satisfying, so a medium-to-long telephoto zoom is a good choice, too.

For mono architectural shots, the high contrast of direct sunlight can be your friend or your foe, depending on which way the building is facing, and what else is around to cast shadows across it.

Picking the right time of day will help (morning for east-facing and afternoon for west-facing buildings), but don’t ignore flat, overcast days, as the soft light from cloud cover will reduce overall contrast and even up the lighting.

Ask any interior photographer, and they’ll tell you that one of the chief problems of shooting interiors is balancing contrast. The reason for this is that daylight streaming through the windows is much brighter than the indoor illumination, and you can’t expose for one without under- (or over-) exposing the other.

The best solution to this perennial challenge is to bracket your shot using the Auto Exposure Bracketing feature (AEB) on your camera. This will let you take several frames at different exposures, which you can then blend into a high-dynamic-range (HDR) image, bringing out the detail from both extremes. See Photo Answers on page 98 for help with HDR images.

This skyscraper shot uses the distortion present in an ultrawide-angle lens to exaggerate the convergence of the lines towards the centre of the frame.

After shooting three exposures (two stops under, metered value, two stops over), the three frames of this highcontrast interior were blended together to give an HDR image that balances the under- and overexposed areas to give smooth, even tones.

With building shots, the parts can carry just as much impact as the whole, so after finding the ‘big’ shot of an imposing structure, switch to a much longer lens to pick out scenes within the scene. From stonework on cathedrals to the intricate lattice of glass and steel on skyscrapers, every element serves up a mix of details with the same character as the whole.

1 Interior details To prevent the external daylight from burning out on this interior shot of a mill’s window, a three-shot HDR was processed to retain all the texture in the frame, glass panes and brickwork.

2Exterior studies The subtle, mottled tones of stonework and the symmetrical lines of architectural details are great subjects for black and white. Every town or city will have an abundance of opportunities.

A medium-to-long telephoto zoom such as a 70300mm is a perfect partner to an ultra-wide lens for picking out details in buildings.

A medium-to-long telephoto zoom such as a 70300mm is a perfect partner to an ultra-wide lens for picking out details in buildings.

When you convert your shots to mono, you turn anything that’s coloured into grey – but how bright or dark that grey tone is in the black and white mix can be controlled. A blue sky, for example, can be processed to appear as a near-white, very light grey through to a very dark grey that’s close to black, or any

tone in-between. This is all achieved using the colour sliders in a raw converter like Camera Raw or Lightroom; or you can do it in Photoshop by creating an Adjustment Layer and selecting Black & White. Just move the sliders for each colour to set the tone as you see fit. Practice makes perfect, so try some options.

It sounds like a contradiction in terms to add colour to a black-and-white picture, but toning treatments are as old as photography itself and work to subtly change the mood and character of an image.

In the traditional darkroom, some toning effects were created by using a paper with a hint of amber warmth or blue coolness, but others involved mixing chemicals into the developing tray to colourise the entire print. The digital toning process is much simpler and easier, but in all instances, you need to shoot and post-process your image as a regular black and white shot first, to get the lighting and contrast captured the way you want it.

The simplest form of lighting for taking indoor still-life shots is window light, and this needs to be soft, so either use a north-facing window or pick a cloudy day, when the light is diffused. Recreating soft window light with a desk lamp or LED light is easy, too – and is often preferable, as you can do it at any time and angle the light to come from any direction. Just place a sheet of tracing paper (or white baking paper) over the light. This ‘trace frame’ softens the shadows cast by the light, emulating diffused daylight. Moving the trace frame further from the light increases the diffusion. Experiment with this, and with the position of the light, to get your shot.

Window light

LED lamp

Paint on your contrast exactly where you want it using two digital emulations of classic wet darkroom tools

1

Dodge the highlights Once you’ve made your mono conversion, copy the image with Ctrl/Cmd+J, then select the Dodge Tool. In the Options bar, set Range to Highlights and Exposure to 5%. Use a soft brush and play the tool over the brighter tones.

Burn the shadows Copy the image again (Ctrl/Cmd+J) and select the Burn Tool. Set Range to Shadows and Exposure to 5%. Play the brush over the darker tones. Vary the brush size with the square bracket keys [ and ] to suit the area you’re working on.

2

Assess the results If you go too far with either tool and lose detail, press Ctrl/ Cmd+Z and try again. To check your progress, switch the eye icons off and on in the Layers Panel to see how dodging and burning has affaected the base layers.

3

The original raw is always in colour, so convert it in Camera Raw by selecting Adobe Monochrome from the Profile box and adjusting the sliders to suit. Then click Open.

The classic neutral mono tone with no colour cast is always the starting point, but the Dodge and Burn tools can be used to pep up contrast in specific areas.

In the regular Photoshop interface, create a Hue/Saturation

Adjustment Layer. In the panel that

Sepia

opens, tick the Colorize box, then set Hue to around 220 and Saturation to around 35.

In the Layers Panel, create a Hue/ Saturation Adjustment Layer. Tick Colorize then set Hue to around 30 and Saturation to around 25.

With your mono shot on-screen in Photoshop, go to Filter > Camera Raw Filter. In the Color Grading panel, set Shadows to one colour and Highlights to another. Use complementary colours such as blue and yellow for the best effect.

Split-tone

There is a tendency these days for photographers to ignore the noble and often subtle art of black and white photography and instead go for the super-saturated colours so liked by the social media and Instagram generation.

Black and white images are photography in its purest form. Colour can be a big distraction, your attention drawn by the vibrancy of an image, not the subject matter and its composition, tone, texture and details, but a large in-your-face splash of bright primary colour.

There is nothing wrong with colour, but black and white photography has an honesty to it that colour images just don’t. After all, you aren’t just reaching for the saturation slider to make the image pop.

Of course, there will be post-production trickery with black and white photography as there is with colour but you have to work that little bit harder in the first instance to actually ‘see’ the image.

You have to respond to shape, tone, texture and shadows, not colour. Seeing and visualising a black and white image is sometimes not a simple straightforward process. Knowing how to use your software

and how it – and you – will interpret your file is just as important as shooting the original scene. And besides, shooting the original scene can be tricky enough.

All location shoots have to be planned but there is far more to shooting a black and white landscape than just getting up for a sunrise or hanging around at the end of the day for a pretty sunset and a few pink clouds. Research into your subject and its location and how it will interact with the light and prevailing weather conditions become critical. Black and white location photography is not a walk in the park – but here’s how to get the most from it...

Jeremy is one of the UK’s most respected landscape photographers, known for his eyecatching panoramas, moody black and white landscapes and dark, dramatic images of castles and ruins. He originally started his career as a studio photographer, and has been specialising in location imagery for over 25 years. He is the author of Landscape, his highly acclaimed first book and is in demand as a speaker, writer and workshop leader.

To see more of Jeremy’s work: www.jeremywalker.co.uk @jeremywalkerphotography

Peak drama Research your subject, its location and how it will interact with the light and prevailing weather conditions

images © Jeremy Walker

Pictured AllThere are many parallels between shooting black and white images and colour: the basic kit remains the same – camera, lenses and filters. Sunrise and sunset are both excellent times to shoot, although with black and white, the time frame for shooting is larger as you are less dependent on warm, golden light. Shooting in mono also means you will shoot less into a sunrise or sunset but more at 90° degrees to the sun, using cross-lighting, texture, shape and shadow to help tell the story of the scene you are shooting.

As for subject matter, you should be searching for images with simple lines and shapes. Abstracts work well in mono as does

losing detail in the shadows. After all, who says you can’t have pure blacks in an image? Look for subject matter that in itself is already dramatic, such as ruined churches or castles, and time your shoot to have menacing, brooding storm clouds threatening the buildings or landscape below.

Post-production will play an important role in how your final image will appear and knowing your software and how it will handle your file is just as important as the shooting process. Photoshop and Lightroom are most people’s defaults, but you should also check out DXO’s Silver Efex Pro, which is a superb tool for the black and white enthusiast.

Images with simple lines work well in black and white. Don’t worry about losing detail in the shadows – after all, who says you can’t have pure blacks in an image?

Below

Catching rays

Look for subject matter that is already dramatic, such as this lighthouse. Time your shoot to have menacing storm clouds threatening the landscape below

Whatever brand and model of camera you have, keeping kit simple is often the best approach to capture unfussy images

1

LEICA M10-R

A 40MP, full-frame rangefinder camera. This is pure simplicity, with just an on/ off button, shutter speed dial and ISO dial on the top plate and a viewing screen and three buttons on the back. It’s also lovely and small.

2

LEICA 50MM F2

This small and compact ‘standard’ lens has just a 39mm screw thread on the front. It’s a stunningly sharp lens – ideal for many landscape situations and especially good for stitched panoramas.

3

ZEISS 28MM F2.8

It’s my alternative to the 35mm lens. I like the look and feel of a landscape shot with a 28mm lens. If weight is at a premium, I will sometimes replace the 35mm with the 28mm.

4

SCREW-IN CABLE RELEASE

Old-fashioned by today’s standards, this cable works perfectly and is not affected by battery power, or the lack of. The shutter on the M10-R is super-soft, but the cable reduces clumsy fingers from wobbling the camera.

5

LEICA 21MM F3.4

This isn’t the fastest 21mm lens on the planet, but the optical quality is stunning. It is surprisingly small, making it ideal for long walks and when camera bag space is at a premium. It also takes the same size graduated filters as the rest of the system.

6

LEICA 35MM F2

Small and stunning and, again, great for stitched panoramas. It’s also perfect for that ‘not too wide’ look when shooting single frame landscapes and is regarded by many as the perfect lens for ‘street’ shooting.

7

ZEISS 85MM F4

An awesome portrait lens, but equally as good shooting landscapes when you need to slightly crop in to a scene. It’s ideal for stitched panoramas and its size lends itself to being a permanent feature in the camera bag.

8

SPARE SD CARDS

It is rare to fill a 64GB memory card on a landscape shoot or even after a few days of location work, but it is always reassuring to carry around a spare, just in case.

9

SPARE BATTERIES

Electronic cameras can be power hungry and, let’s face it, we all review our images far too much. Two spare batteries and one in the camera will last for a long day’s shooting, even in the cold weather.

10

LEE FILTERS SEVEN5 FILTER HOLDER AND .6 AND .9 MEDIUM GRADUATED FILTERS

This small and compact filter system is ideal for a lightweight landscape set up. Sometimes a LEE polariser or Big Stopper may be carried as well, depending on what I’m shooting.

How many times have you heard the oftrepeated mantra ‘expose to the right’? Get the histogram to the right-hand side of its box without causing any clipping or overexposure and make sure you don’t ‘underexpose’ or lose detail in the shadows.