The Bridge

with FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

“From ‘What is Real’ to ‘What is Right’. Discover the world of ethics with Friedrich Nietzsche!”

Matthew Pye, Author of ‘No Common Sense’

“From ‘What is Real’ to ‘What is Right’. Discover the world of ethics with Friedrich Nietzsche!”

Matthew Pye, Author of ‘No Common Sense’

From ‘What is Real’ to ‘What is Right’.

00/ Introduction

• Climate Change is not just a problem of perception

10/ Cultural illusions

• Nietzsche the Pyschologist

• Looking through the Overton Window

• Watching the BBC

20/ Melting Points

• In Science - In Society

• A new Overton Window?

• Nietzsche the Prophet

30/ Choose your own Adventure

40/ Introduction

• Ecce Homo’ - The Man

• ‘God is dead’ - The Philosophy

50/ Nietzsche tackles Climate Change

• 1. The importance of Language

• 2. The importance of irony, metaphor and paradox

• 3. The importance of ‘Sublime Madness’

• 4. The importance of not retreating into a cave

• 5. The importance of thinking things through until the end.

60/ Conclusion

We have made long strides forward in climate science, especially in the last few decades. Although our models and projections require constant revision and improvement, the basic summary of where we are is unambiguous.

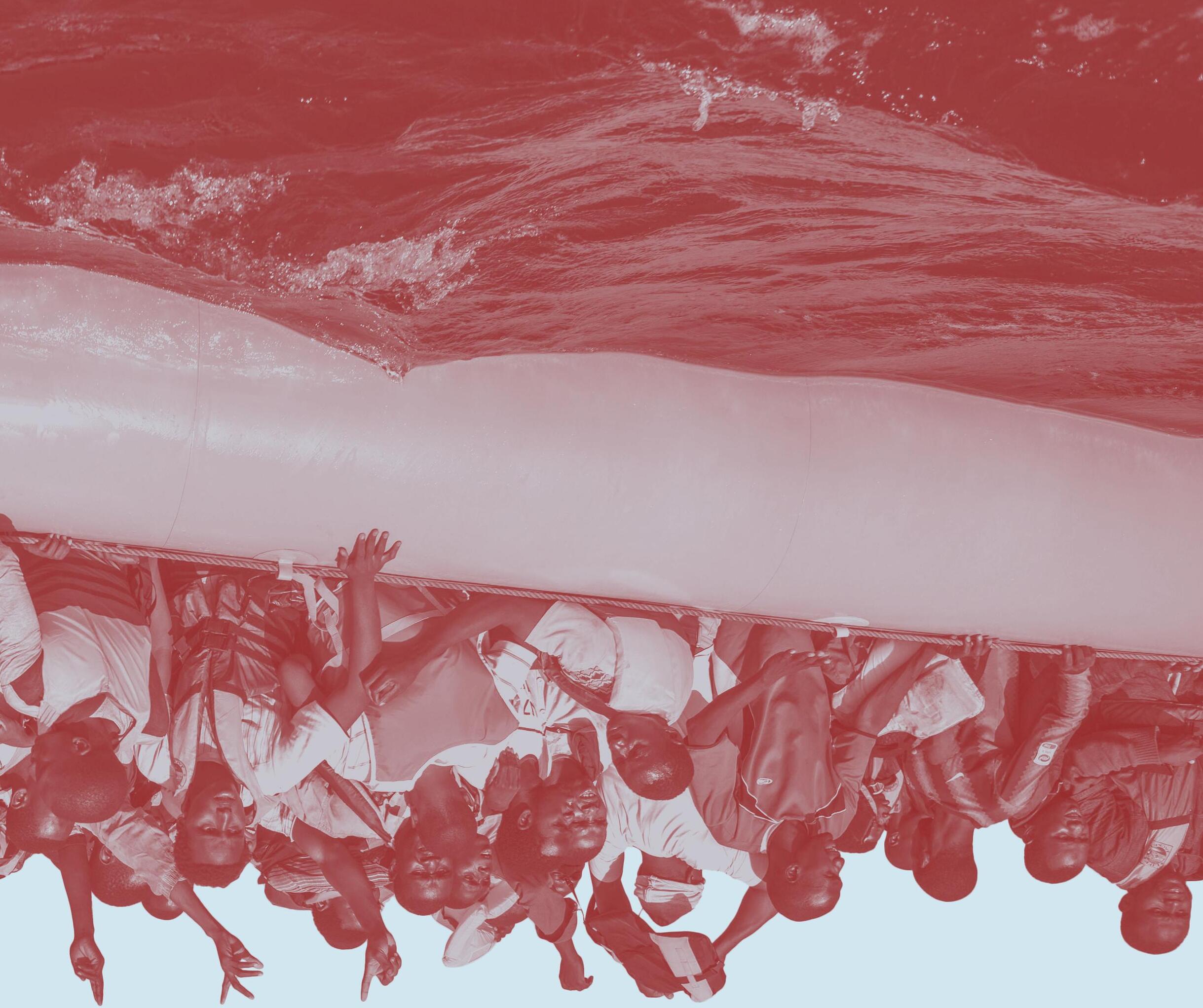

Itis true that many of the problems that we have with understanding climate change are simply problems of Epistemology – or more specifically, problems of perception. Our routine understanding of the world is sometimes just not good enough. However, it was also evident in Chapter 1 that some moral and political influences are at work in our lack of awareness. Some of the forces that prevent us from getting a clear picture of climate change are simply rooted in our natural human reactions to danger, suffering, or perhaps just plain inconvenience. We often recoil from difficulties and prefer to push problems away, in order to tend to the peace of our own lives. These individual instincts

become powerful political forces when they play out at a social level.

Gaining a more reliable understanding of what is real (more often than not) is connected to ethical issues about what is right. Epistemology and Ethics are tightly bound together. There are so many examples throughout the history of human culture where certain fields of knowledge were blockaded because of some very forceful ethical or political concerns.

In fact, there are often very interesting consequences when the truth pushes against power or desire, fears or anxieties, tradition or authority. These

confrontations are a pervasive problem in human affairs and, unsurprisingly, they will continually surface in a book about climate change. When confronted by an uncomfortable truth, we have a remarkable capacity for hiding reality with illusions. The human psyche is a fascinating and curious thing.

There is a rich tradition of thinkers who have explored how we can create fictions around reality because of a deep ethical impulse working at the base of our minds. Schopenhauer, Feuerbach and Freud (to name a few) all have quite brilliant insights in this field. However, it is Nietzsche who will help to build this bridge from Epistemology to Ethics.

Introduction – Cultural illusions – Melting Points – Choose your own Adventure

His teachers would have called him ‘knee-cha’ , and the UK has followed this pronunciation. In the USA it is ‘knee-chee’, or if you are debating the key influences on post-modern culture in a Parisian café on the left-bank, speaking in french, then it is simply, ‘kneech’ .

Why Nietzsche? The most basic answer is that Nietzsche was a philosopher who was concerned with social illusions.

In our current Western society, there is a serious mismatch between reality and people’s beliefs and lifestyle. As explained in the opening, we have already started walking into the minefield of climate change. The further we go into this minefield of a warmer planet, the more likely it will be that we will trigger major damage to our civilisation. Moreover, if we do not dramatically choke off our emissions, the overall level of disruption will become unmanageable – and once some major cogs of the climate system come loose, they could in turn trigger cascading feedback loops that would lead to a ‘Hothouse Earth’. Despite this existential threat, there is has been no meaningful impact on government policies. We are still striving for maximal economic growth without decoupling it from carbon emissions. Population growth is not considered to be a critically urgent debate. We still invest more in fossil fuels than in green technology. Citizens’ voting or habits of consumption have remained largely unruffled. Climate change is a seismic event and yet millions of people have not really understood it. Indeed, even if it was to be explained, there are hundreds of possible bypasses in the network of the human mind that can see the problem, so that we somehow do not react. Nietzsche faced a parallel problem at the end of the 19th century in Germany. He was an atheist, and he had observed that even though the idea of a Christian God had just been through some bruising cultural

battles, most people had not really shifted their lifestyle or their beliefs to fall in line with the reality of a godless world. The theological questions posed by Newtonian Physics, Darwinian Biology, Psychological Reductivism and Biblical Criticism (to name a few) had really shaken the viability of Christian belief. Yet even though many of these new scientific theories and critical methods of thinking about God had progressed from academia into popular culture, Nietzsche was frustrated to see that the implications of these ideas were having a small impact on the ground. He thought that important psychological and social forces were at work in this inertia. Indeed, there are two major reasons for picking out Nietzsche to make the bridge from Epistemology to Ethics for this book on climate change: Firstly, Nietzsche was intolerant of the comfortable social illusions that he saw around him. He understood that many of the ideas that governed people’s lives and behaviour were difficult to shake off because they were plugged into issues of power and control. Secondly, Nietzsche’s commitment to the truth is a valuable reminder of the role of the philosopher in a society. Nietzsche thought that he lived in a culture that had lamentable attitudes to the truth. He argued that they were sloppy at best, and manipulative at worst. Crucially, he was disturbed by this lack of respect for critical thinking because he thought that it was behind some very unhealthy social realities.

Introduction

Nietzsche was very perceptive in his examination of how our beliefs are affected by psychology. His work poses interesting questions about how the complex drives and desires of our subconscious are plugged into the mind. It now seems so normal to accept that we do not hold our beliefs simply because they are logical or coherent; we are very aware that there is a whole matrix of psychological forces at work under the surface.

It was Nietzsche who did so much to put the notion of psychological and social illusions forward as a mainstream idea. Indeed, it is probably wise to approach Nietzsche as a psychologist first, given that it provides an accessible entry point to his ideas before things get a bit heady later on.

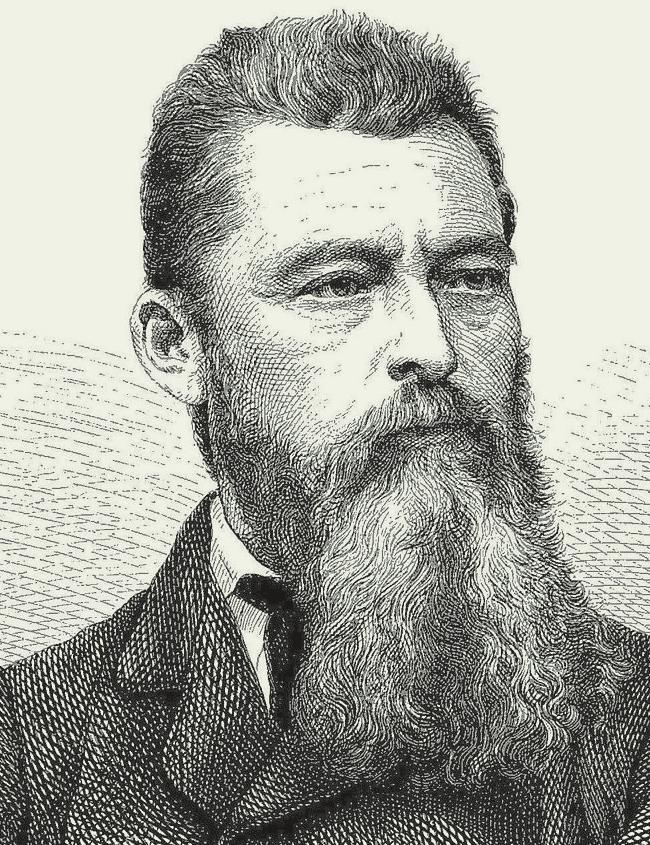

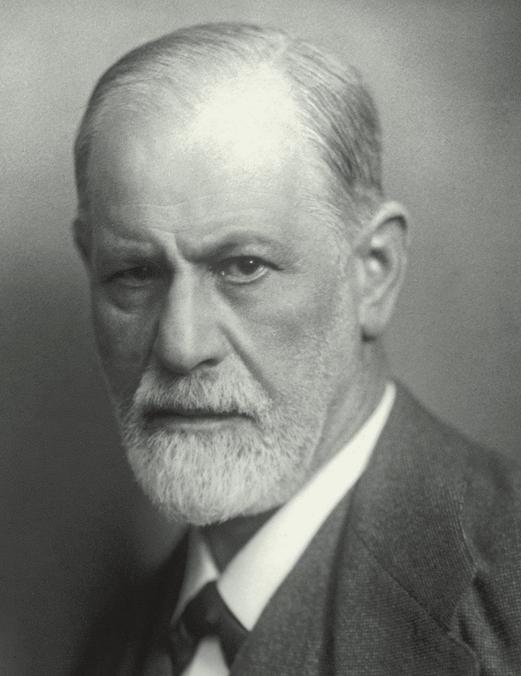

Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872) Karl Marx (1818-1883) Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) Sigmund Freud (1856-1939)

Looking at the major social thinkers that were roughly contemporary with Nietzsche, it seems like the extent of facial hair was somehow related to the depth of psychological insight.

Just3 years before Nietzsche was born, a hugely influential book was published, “The Essence of Christianity” (1841). Its author, Ludwig Feuerbach was a thinker who had a massive and lasting impact on Philosophy. However, his own work tends to get overlooked because the thinkers he most markedly influenced went on to become the major constellations of 20th century culture. The three stellar thinkers of Marx, Nietzsche and Freud are all indebted to him for his pioneering contribution to psychology.

Feuerbach’s central thesis is fairly easy to summarise quickly: He argued that God was not real, it was merely an ideal projected out of human’s deepest hopes and fears. He is often classified as a ‘Psychological Reductivist’ because (with unusual frankness for the time) he reduced the notion of God down to simply a product of human psychology. If we fear death, we imagine an everlasting afterlife awaits. If we suffer from prejudice or poverty, we imagine a God that will act with justice. In Feuerbach’s own words, “Consciousness of God is self-consciousness, knowledge of God is self-knowledge. By his God you can know the man, and by the man, his God; the two are identical.”

it was time for mankind to step out of his long shadow. We could, and should, stand alone.

Feuerbach had planted Psychology into the middle of Philosophy and it took root quickly.

Reading Feuerbach provoked in Marx something akin to an inverted religious epiphany. He suddenly saw that the workers were being exploited by the owners of capital under the illusion of an afterlife (and various capitalist values). The promise of a utopian reward after death served as an ‘opiate’ to calm their nerves and soften the pain of their earthly poverty. The promises and hopes that were provided on Sunday enabled the workers to face work again on Monday.

“Consciousness of God is self-consciousness, knowledge of God is selfknowledge. By his God you can know the man, and by the man, his God; the two are identical.”

Furthermore, Feuerbach was a Humanist and he argued that this illusory projection of ‘God’ was not just false, but it was also diminishing of human life and values. God is always “Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger…” (rather like the Daft Punk track goes). Therefore, Feuerbach argued,

Freud read Feuerbach and he saw that men needed to create a huge range of illusions to cover up their dark drives and sexual impulses from themselves. His pornographic use of Feuerbach was centred on his famous ‘Oedipal Complex’ which stated that men’s sexual urges to be with their mothers [sic] was such a social taboo that it had to be repressed deep into the subconscious mind. Any male reader who is offended by such a suggestion is simply confirming the existence of the suppression in their mind. Freud would argue that a closer inspection of their dreams at night, some analysis of any compulsive behaviour, or deeper reflection on their genuflexions in church on Sunday morning, might prove to be more revealing.

Finally, (the moustachioed hero of this Chapter) we turn to Nietzsche. With typical boldness, a touch of irony, and lot of self-belief, Nietzsche wrote of himself, “That a psychologist without equal speaks from my writings – this is perhaps the first insight gained by a good reader.” (Ecce Homo) He was very attentive to the effects of psychology on ethics.

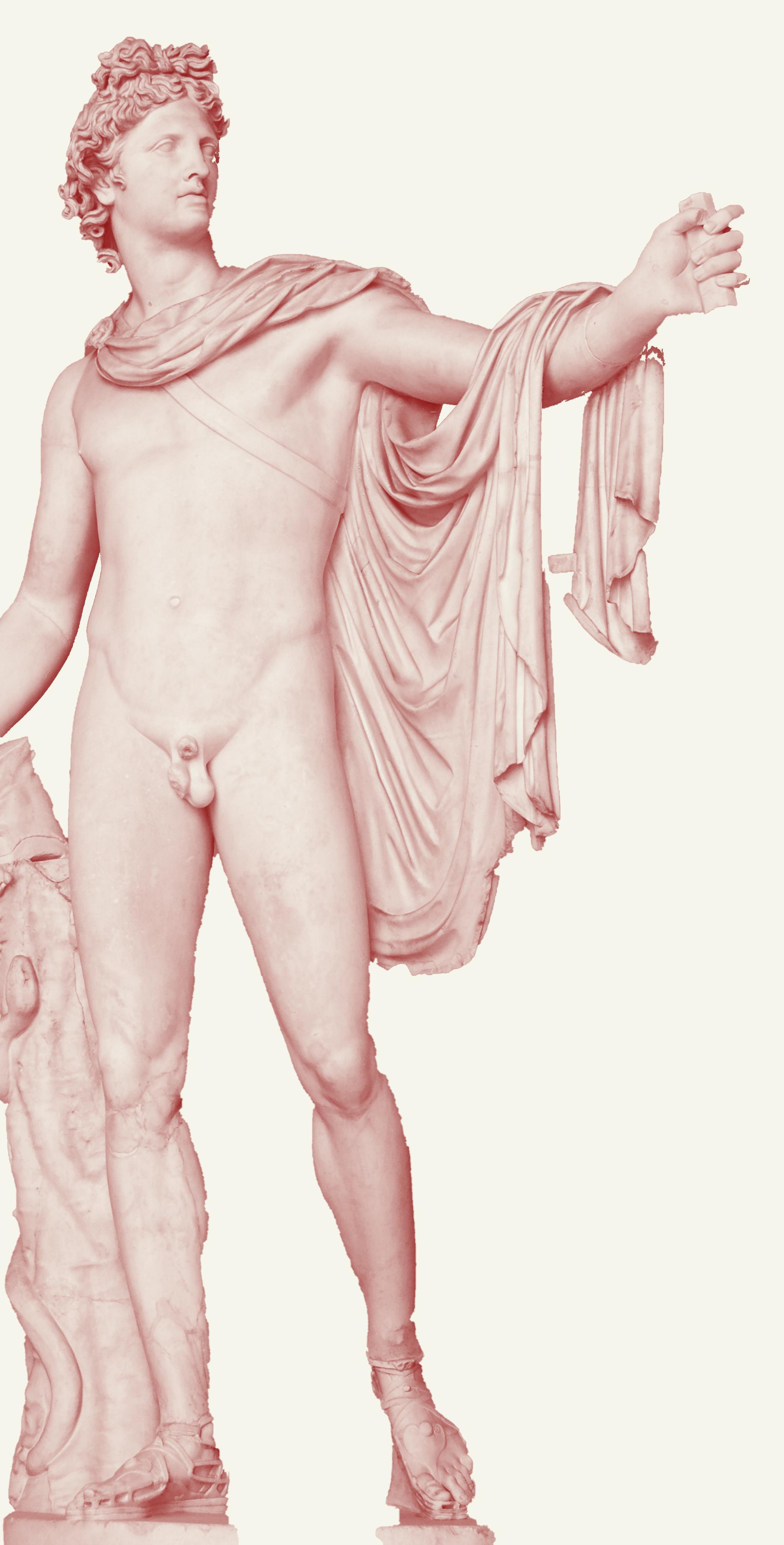

Nietzsche thought that the governing rule of most beliefs and behaviour was human being’s subterranean “will to power”. Sometimes this drive can be simple and explicit, as exemplified in the value that most Greek and Roman culture placed on strength and overcoming. Sometimes this will has to find subversive and more complex routes to power – something that he thought characterised the Christian revolution in the Roman world, or the French Revolution’s usurping of the ‘Ancien Régime’ in 1789. In both cases, those without power, realising that they could never beat their masters on their own terms, decided to reverse the value system in order to get it.

More specifically: Poverty, weakness, humility and suffering became values in the Christian revolution, because they had them in abundance. Conversely, wealth, strength, power and comfort were made evil because they were simply permanently out of reach - the powerless Jews, after centuries of frustration under the Babylonians, Persians, Greeks and Romans, could never conceivably take back their land and laws from the fist of the occupying Army. Likewise, the ‘sans-culottes’ of the French Revolution made democracy and brotherhood into the ultimate value, given the fact they could never legitimately put on a fancy wig. Nietzsche’s summarised this psychological insight into history as ‘The Slave Revolt’.

I am reminded of Nietzsche’s idea each time I punish my own children with some sort of confiscation or a prohibition, and they say, “well… you know, I didn’t want it anyway” with a grouchy face. History for Nietzsche is dominated by the story of a struggle between people who are trying to define good and evil on their own terms.

Indeed, Nietzsche thought that in order to understand our own ideals we have to look back through our “Genealogy of Morals” (1887). We have to examine the family tree of where current values came from. Or as Nietzsche put it in his work, “All too Human” (1878) “Direct self-observation is not nearly sufficient for us to know ourselves: we need history, for the past flows on within us in a hundred waves.”

More details will follow later, because Nietzsche’s life and times need to be understood for the fuller picture to become clear. For the moment, it is simply important to note that Nietzsche’s philosophy, in both its understanding of ethics and epistemology, is powered by psychology. Nietzsche teaches us to examine our culture with a sceptical distance. This is especially true for the values we prize the most, and which direct the subplot to the story lines that we are born into.

Nietzsche’s work on morality argues that the values that we consider to be the most basic, the most deeply wired, are in fact not in any way transcendent or divine. They are only merely fashions that switch. Moreover, these fashions are an expression of a human drive for power in all its diverse appearances. Nietzsche is, therefore, a thinker who can help us lift the rug of our beliefs to see what might be hiding underneath them. This is a skill that will be particularly useful if we are trying to get underneath the psychological blocks to our civilisation’s failure to act on the clear dangers of climate change.

Colophon

Author: Matthew Pye

Guest Authors: Vappu Väänänen, Ginny Tyson, Jules Pye (‘3 Essays for Childpress’)

ISBN/EAN: 978-90-74730-40-2

First run: January 2019

Published by Fysio Educatief in cooperation with ChildPress.org

Copyright ©2019 Fysio Educatief

Proofreading: Sean O’Dubhghaill & Generation Z

Cover Illustration: Stijn van der Pol Cartoons: Carl Jonsson Design: www.thisissaf.com

Graphs and Photography: All sources listed with image, unless the original source could not be tracked. In case you find a copyrighted image, please let us know.

Fysio Educatief • Groenburgwal 59 • 1011 HT Amsterdam www.fysioeducatief.nl • office@fysioeducatief.nl

Climate Change is not just a problem of perception.

We have made long strides forward in climate science, especially in the last few decades. Although our models and projections require constant revision and improvement, the basic summary of where we are is unambiguous.

It is true that many of the problems that we have with understanding climate change are simply problems of Epistemology – or more specifically, problems of perception. Our routine understanding of the world is sometimes just not good enough. However, it was also evident in Chapter 1 that some moral and political influences are at work in our lack of awareness. Some of the forces that prevent us from getting a clear picture of climate change are simply rooted in our natural human reactions to danger, suffering, or perhaps just plain inconvenience. We often recoil from difficulties and prefer to push problems away, in order to tend to the peace of our own lives. These individual instincts become powerful political forces when they play out at a social level.

Gaining a more reliable understanding of what is real (more often than not) is connected to ethical issues about what is right. Epistemology and Ethics are tightly bound together. There are so many examples throughout the history of human culture where certain fields of knowledge were blockaded because of some very forceful ethical or political concerns.

In fact, there are often very interesting consequences when the truth pushes against power or desire, fears or anxieties, tradition or authority. These confrontations are a pervasive problem in human affairs and, unsurprisingly, they will continually surface in a book about climate change. When confronted by an uncomfortable truth, we have a remarkable capacity for hiding reality with illusions. The human psyche is a fascinating and curious thing.

There is a rich tradition of thinkers who have explored how we can create fictions around reality because of a deep ethical impulse working at the base of our minds. Schopenhauer, Feuerbach and Freud (to name a few) all have quite brilliant insights in this field. However, it is Nietzsche who will help to build this bridge from Epistemology to Ethics.

From ‘What is Real’ to ‘What is Right’.

00 /Introduction

Climate Change is not just a problem of perception

10 /Cultural illusions

Nietzsche the Pyschologist

Looking through the Overton Window

Watching the BBC

20 /Melting Points

In Science

In Society

A new Overton Window?

Nietzsche the Prophet

30 /Choose your own Adventure

40 /Introduction

Ecce Homo’ - Nietzsche - The Man ‘God is dead’ - Nietzsche - The Philosophy

50 /Nietzsche tackles Climate Change

1. The importance of Language

2. The importance of irony, metaphor and paradox

3. The importance of ‘Sublime Madness’

4. The importance of not retreating into a cave

a. The cave of denial

b. The Christian cave

c. The Climate Change cave

5. The importance of thinking things through until the end.

a. God’s Shadow

b. Christian Shadows

c. Climate Change Shadows

60 /Conclusions